Abstract

Purpose

Apoptosis in irradiated normal lung tissue has been observed several weeks post radiation. However, the signaling pathway propagating cell death post-radiation remains unknown.

Methods and Materials

C57BL/6J mice were irradiated with 15 Gy to the whole thorax. Pro-apoptotic signaling was evaluated 6 weeks after radiation with or without administration of AEOL10150, a potent catalytic scavenger of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species.

Results

Apoptosis was observed primarily in type I and type II pneumocytes and endothelium. Apoptosis correlated with increased PTEN expression, inhibition of downstream PI3K/AKT signaling, and increased p53 and Bax protein levels. TGF-β1, Nox4, and oxidative stress were also increased 6 weeks after radiation. Therapeutic administration of AEOL10150 suppressed pro-apoptotic signaling and dramatically reduced the number of apoptotic cells.

Conclusion

Increased PTEN signaling after radiation results in apoptosis of lung parenchymal cells. We hypothesize that upregulation of PTEN is influenced by Nox4-derived oxidative stress. To our knowledge, this is the first study to highlight the role of PTEN in radiation-induced pulmonary toxicities.

Keywords: radiation, apoptosis, ROS, PTEN, Nox4

Introduction

Radiation pneumonitis and fibrosis are major obstacles for escalating radiation doses and improving overall patient survival in the treatment of thoracic tumors. However, the underlying mechanisms which culminate in debilitating pulmonary toxicities following radiation are not fully understood. Previous studies have reported apoptosis in normal lung tissue immediately and up to several weeks after radiation1; however, the signaling pathway involved in cell death after radiation remains unknown.

Loss of function mutations of the tumor suppressor gene PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10) have been widely observed in a variety of malignancies leading to enhanced tumor cell survival and increased treatment resistance2. The protein product of PTEN is a phosphoinositide 3-phosphatase that antagonizes phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)-Akt signaling to mediate apoptosis2. Activation of wild-type PTEN regulates cell apoptosis through removal of a phosphate from PI3K-produced phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-triphosphate (PIP3) to generate phosphatidylinositol 4,5 bisphosphate (PIP2)2, thereby leading to reduced levels of PIP3. In tumors with PTEN mutations, elevated levels of PIP3 confer a survival advantage by circumventing pro-apoptotic signaling. Downstream activation of integrin linked kinase (ILK) by IP3 leads to phosphorylation of Akt at Ser473 and Thr308 residues, both of which are required for maximal Akt activity. Previously, radiation has been shown to significantly upregulate PTEN expression in kidney epithelial cells in vitro3. We therefore hypothesized that PTEN might be activated in normal lung tissue following radiation to mediate cell death.

We further hypothesized that PTEN-mediated apoptosis might be influenced by oxidative stress. Oxidative stress begins at the time of radiation exposure and is sustained throughout the time to disease progression, presumably through radiation-induced activation of oxidant generating enzymes, mitochondrial leakage, and activation of the respiratory burst in phagocytic cells infiltrating the damaged tissue.

The most notable family of oxidant generating ezymes are the NADPH oxidases. NADPH oxidases participate in redox-mediated signaling to regulate a number of pathways including those involved in vascular function, cell survival, and differentiation4. Studies have shown that Nox4, a member of the NADPH oxidase family, mediates TGF-β1-induced apoptosis of pulmonary epithelial cells during fibrosis5. Therefore, we hypothesized that radiation-induced activation of TGF-β1 might, in part, induce Nox4 expression and activity6, thereby contributing to propagation of oxidative stress and apoptosis in irradiated lung of fibrosis prone mice7.

In this study, we evaluated whether PTEN signaling contributes to pulmonary epithelial and endothelial cell apoptosis six-weeks following radiation. Next, we evaluated whether PTEN expression and downstream signaling is influenced by cellular redox status by treating irradiated mice with a potent catalytic scavenger of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS/RNS), AEOL101508 and observing the effects on TGF-β1 and Nox4 expression, oxidative stress, and PTEN signaling.

Materials and methods

Animal experiment

Female C57BL/6J mice (18–20 grams) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine). Mice were housed five per cage on a 12-hour light/dark cycle and provided water and food ad libitum. Mice were randomized to four groups to receive: sham irradiation, AEOL10150 alone, radiation (IR) alone, or IR + AEOL10150. Mice in the radiation group received a single fraction of 15 Gy to the whole thorax using 320 kV x-rays (Therapax 320, Pantak Inc., East Haven, CT). AEOL10150 [Mn(III) meso-tetrakis(N,N′-diethylimidazolium-2-yl)porphyrin] was supplied by Aeolus Pharmaceuticals (Laguna Niguel, CA). A loading dose (40 mg/kg/day dissolved in saline) was administered subcutaneously 2 hrs after thoracic irradiation and thereafter, a maintenance dose of 20 mg/kg/day was administered on alternate days for 4 weeks. Based on our unpublished data, this dosing regimen is able to suppress lung injury in irradiated mice (Rabbani et al. unpublished data). All animal experiments were conducted with prior approval from the Duke University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Animals were humanely euthanized according to Duke IACUC guidelines at a predetermined time of six weeks post-radiation. At the time of euthanasia, the lungs were harvested, weighed, and sectioned. Tissue from five animals per group was formalin fixed and paraffin embedded. For the remaining 7–14 mice per group, the lungs were sectioned and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until the time of analysis.

Histopathology and Immunohistochemistry

Five tissue sections from each group were stained with hematoxylin and easin (H&E) for histopathology. Immunohistochemistry was carried out on paraffin embedded tissues as previously described9, 10. Tissues were treated with primary antibodies to 8-hydroxydeoxyguanine for oxidative DNA damage (8-OHdG, 1:2000, JaICA, Shizuoka, Japan), PTEN (1:100, Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Beverly, MA), and Nox4 (1:400, Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA).

Image analysis was carried out as previously described9, 10. Slides were systematically scanned and 8–10 representative digital images were acquired from each slide using a 40x objective. Digital images were quantified by image analysis with Adobe Photoshop (Version 7.0; Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA) and scored by two independent observers blinded to the identity of the slides.

Terminal Deoxynucleotidyl Transferase-Mediated Nick End Labeling Assay for In Situ Cell Death Detection

The in situ cell death detection kit (Roche Molecular Biology, Mannheim, Germany) was used according to the user manual. Briefly, lung sections were rinsed with 3% H2O2 in methanol for 10 minutes to block endogenous peroxidase. After washing with PBS, the slides were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in 0.1% sodium citrate for 2 minutes on ice, then incubated with terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated nick end labeling reaction mixture for 60 minutes at 37°C. After washing, converter-PD was added to the slides and the slides were incubated for 30 minutes at 37°C in a humidified chamber. 3, 3′ diaminobenzidine-substrate solution was placed on the slides for ten minutes, after which the slides were analyzed under a light microscope.

Dual-immunofluorescence

To identify cell types undergoing apoptosis, double immunofluorescent staining was performed on frozen tissue sections (n = 5/treatment group) for co-localization analysis. The following primary antibodies were applied: rabbit polyclonal anti-aquaporin 5 for Type I pneumocytes (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), rabbit polyclonal anti-surfactant protein D for Type II pneumocytes (Abcam, Cambridge, MA), and rat monoclonal CD31, a pan-endothelial cell marker (BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA). Texas red labeled donkey anti-rabbit or anti-rat secondary antibodies (Jackson Immuno-research) were used where relevant. Double labeling for apoptosis was performed by utilizing fluorescein conjugated in situ cell death detection kit (Roche Molecular Biology, Mannheim, Germany) and performed according to the user manual as described above. Using a fluorescent microscope (Axioskop, Zeiss), two filters for FITC (green) and TRITC (red) were used to identify double staining. The respective stains were overlayed using Metamorph software (Universal Imaging Corporation). Analysis was carried out by two independent observers who were blinded to the identity of the slides.

Tissue homogenate and Western blot

The snap frozen right lung was homogenized in ice-cold homogenization buffer (1% sodium deoxycholate, 5 mM Tris-HCL (pH 7.4), 2 mM EDTA, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 μM pepstatin A, 0.1 mg/ml benzamidine with or without phosphatase inhibitors) and western blot performed as previously described11. Western blots were performed using lung tissue collected from fourteen mice per group (sham-irradiated and radiation alone) or six mice per group (sham irradiated + AEOL10150 or IR+ AEOL10150). Samples were not pooled. Antibodies for site-specific phosphorylation of PI3K p85/p55 subunit, phospho-Akt Ser473, phospho-Akt Thr308, total Akt, PTEN, p53, Bax, and the peroxidase-labeled secondary antibody were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverley, MA). Nox4 and TGF-β1 antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). To control for loading efficiency, the blots were stripped and reprobed with GAPDH (Sigma-Aldrich). Proteins were normalized to appropriate markers (Akt or GAPDH) and then expressed as % control.

Caspase-3 activity and ILK activity assay

Caspase-3 activity in 250 μg of left lung homogenates (n=6/treatment group) was measured using the Caspase-3 Colorimetric Activity Assay Kit (Millipore, Temecula, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. All samples were run in triplicate. Caspase-3 activity was determined by comparing the OD reading. ILK activity assay was conducted as previously described12.

RNA isolation and RT-PCR

The snap frozen left lung (n=6/treatment group) was homogenized in Trizol reagent (Invitrogen Inc., Carlsbad, CA) with the PowerGen 125 homogenizer (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). Total RNA isolation and reverse transcription were performed following the factory manual (Invitrogen Inc.). Two pairs of primers were used in one reaction: one amplifies the target gene fragment and another amplifies a 1 kb GAPDH fragment serving as an internal control using the forward primer: 5′-GGTGAAGGTCGGTGTGAACG-3′ and reverse primer: 5′-TGGAGGCCATGTAGGCCATG-3′. The PTEN gene was amplified by forward primer: 5′-GACTTGAAGGTGTATACAGGAAC-3′ and reverse primer: 5′-GCTGGCAGACCACAAACTGAG-3′, producing a 538bp fragment.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was done with two tailed student t-test. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean.

Results

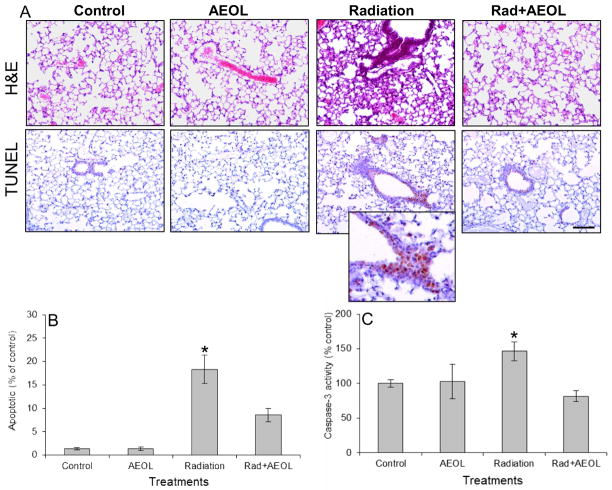

Scavenging ROS/RNS with AEOL10150 significantly reduced apoptosis and caspase 3-activity in irradiated lung

A significant increase in the number of TUNEL positive nuclei was observed in lung tissue six weeks following thoracic irradiation (Fig. 1A, B). This corresponded to an increase in caspase-3 activity in lung tissue homogenates. In contrast, mice treated with AEOL10150 for the first four weeks following radiation displayed a significant reduction in the number of TUNEL positive cells and diminished caspase-3 activity at 6 weeks post-radiation (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1. Apoptosis in lung tissue six weeks after thoracic irradiation.

(A) The increase in apoptotic nuclei (TUNEL assay) in irradiated lung tissue is reduced in AEOL10150 + IR treated mice. (B) Apoptotic index indicates the average number of apoptotic nuclei per 20x field normalized to sham-irradiated controls. An increase in positive staining for apoptotic nuclei was observed in irradiated lung tissue six weeks post-exposure which was not observed in mice treated with AEOL10150 for four weeks after exposure. Bar represents 100 μm. *p < 0.001 Rad vs. control; *p < 0.05 Rad vs. Rad+AEOL group. (C) Normalized caspase-3 activity confirms the presence of apoptosis in irradiated tissue. *p < 0.05 Radiation vs. each of the other groups.

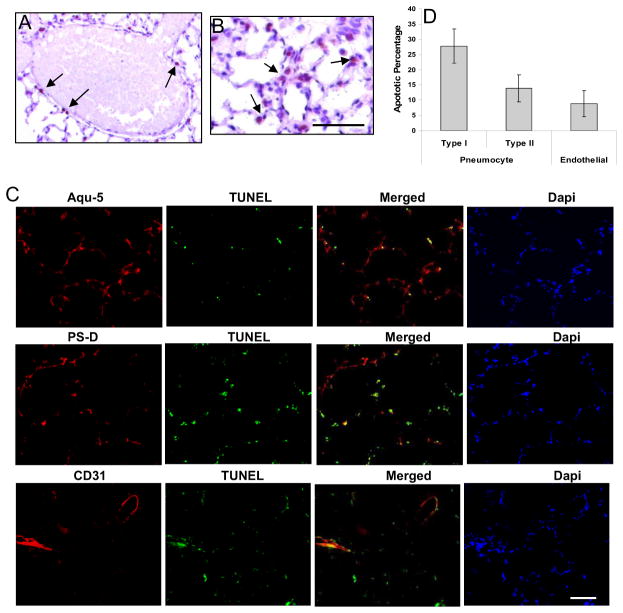

Apoptosis co-localized with endothelium and pneumocytes

Positive TUNEL staining was localized to endothelium (Fig. 2A) and to a greater extent, the epithelium (Fig. 2B) of lung tissue. The percentage of cells undergoing apoptosis were determined by taking the ratio of TUNEL positive cells over the total number of cells for each cell type. The data demonstrate Type I pneumocytes were the predominant cell type undergoing apoptosis (28%) with relatively less Type II pneumocytes (15%) and endothelial cells undergoing apoptosis (11%) (Fig. 2C,D).

Figure 2. Apoptosis is primarily localized to the lung parenchyma.

TUNEL staining for apoptotic nuclei shows apoptotic cells predominantly in (A) endothelium and (B) alveolar epithelium. (C) Co-localization of TUNEL stain with type I and type II pneumocytes and endothelial cells. Green fluorescence: TUNEL positive cells; Red fluorescence: type I pneumocytes (Aqu-5), type II pneumocytes (PS-D), and endothelium (CD31). Overlay of two images depicts co-localization of apoptotic cells with type I pneumocytes, type II pneumocytes, and endothelial cells (yellow fluorescence). Dapi shows the staining of cell nucleus. Aqu-5: aquaporin 5, a specific marker for type I pneumocytes; PS-D: surfactant protein D, a specific marker for type II pneumocytes. (D) Percentage of apoptotic pneumocyte and endothelial cells.

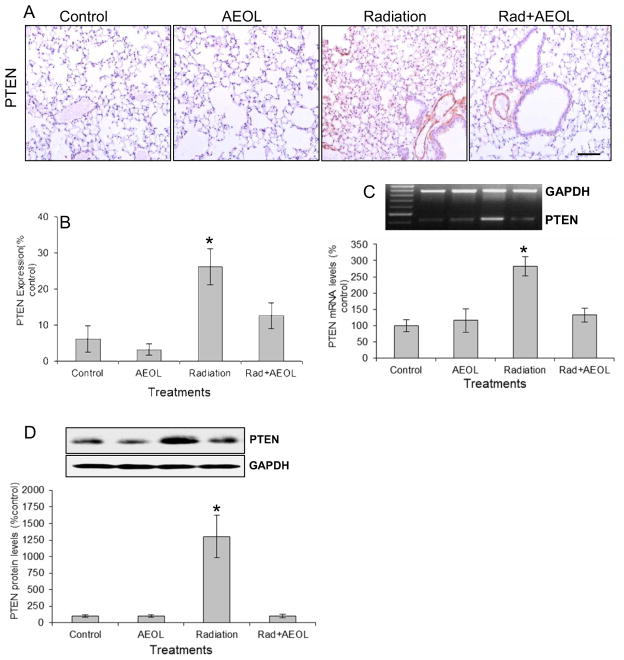

PTEN and its downstream signaling were normalized in irradiated mice given AEOL10150

A significant increase in PTEN expression at both the protein (Fig. 3A, B) and mRNA (Fig. 3B) levels was observed in irradiated tissues. Scavenging ROS/RNS with AEOL10150 significantly blocked radiation-induced PTEN expression (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. PTEN expression.

(A) Immunostaining for PTEN. (B) Semi-quantitative analysis of PTEN expression in (A). *p < 0.001 Rad vs. control and AEOL alone groups; *p < 0.05 Rad vs. Rad+AEOL group. (C) Western blot of PTEN expression (*p < 0.001). Top panel shows representative Western blots of PTEN and GAPDH. (D) RT-PCR assay of PTEN mRNA expression (*p < 0.001). Top panel shows representative RT-PCR products of PTEN and GAPDH mRNA.

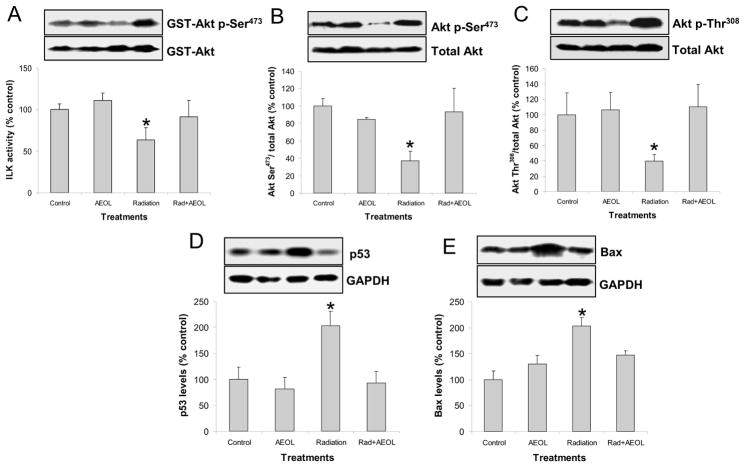

PI3K/Akt signaling is a key signaling pathway negatively regulated by PTEN. In this study, ILK activity (Fig. 4A) and phosphorylation of Akt at both the Ser473 (Fig. 4B) and Thr308 (Fig. 4C) residues were decreased in irradiated normal lung tissues. Conversely, PI3K activity, determined by phosphorylation at the p85/55 subunits, exhibited no changes (data not shown). Downregulation of PI3K/Akt signaling was associated with increased p53 (Fig. 4D) and Bax (Fig. 4E) protein levels in irradiated lung. In mice treated with AEOL10150 + IR, an increase in Akt signaling was observed which correlated to reduced expression of p53 and Bax.

Figure 4. Changes in PTEN signaling.

(A) ILK activity assay in lung tissue lysate (*p < 0.05 vs. each of other groups). Top panel shows representative Western blot of phosphorylated GST-Akt (activated by ILK) and unphosphorylated GST-Akt substrate. (B) Significant decrease in Akt phosphorylation at Ser473 (*p < 0.05) and (C) Thr308 residues were observed in irradiated lung. (D) p53 (*p < 0.05) and (E) Bax (*p < 0.01 vs. control group; *p < 0.05 vs. AEOL alone and RAD+AEOL groups) protein levels were significantly increased in irradiated lung tissue 6 weeks after radiation. The top panels in D and E show representative Western blots of p53 or Bax and GAPDH.

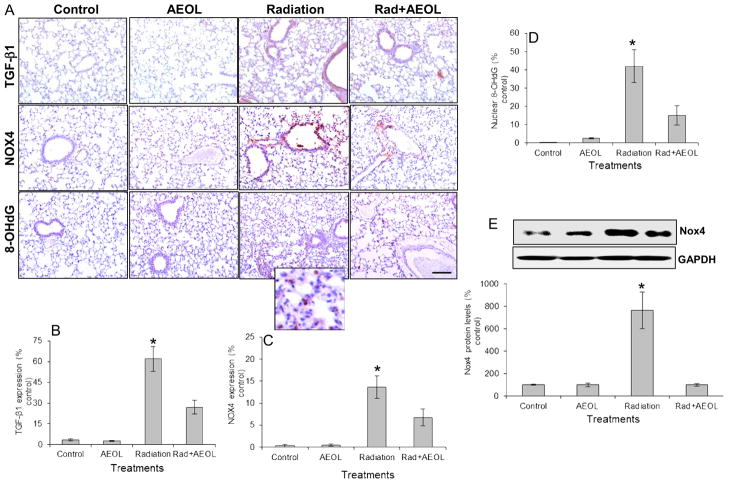

AEOL10150 reduced TGF-β1, Nox4, and oxidative stress in irradiated lung

As expected from previous studies13, elevated expression of TGF-β1 was observed in irradiated lung tissue, but not in tissue from irradiated mice treated with AEOL10150 (Fig. 5A, B). Nox4 mRNA and protein expression were evaluated by RT-PCR (mRNA, Fig. 5C), immunohistochemistry (Fig. 5A), and Western blot (Fig. 5E). Nox4 protein expression was significantly increased in the lungs of irradiated mice. This increase in Nox4 was not observed in mice treated with AEOL10150 + IR (Fig. 5). A reduction in 8-OHdG was observed in lungs from mice treated with AEOL10150 + IR (Fig. 5A, D). Furthermore, treatment with AEOL10150 led to a decrease in PTEN signaling and fewer apoptotic cells suggesting oxidative stress within the first four weeks post-radiation might play a unique role in propagating cell death several weeks after exposure.

Figure 5. Changes in TGF-β1, Nox4, and 8-OHdG levels.

(A) Immunostaining for TGF-β1, Nox4, and 8-OHdG levels. Bar represents 100 μm. (B) Semi-quantitative analysis of TGF-β1 (*p < 0.001 vs. control and AEOL alone groups; *p < 0.05 vs. Rad+AEOL group). (C) Nox4 (*p < 0.001 vs. control and AEOL alone groups; *p < 0.05 vs. Rad+AEOL group), and (D) 8-OHdG (*p < 0.001 vs. control and AEOL alone groups; *p < 0.05 vs. Rad+AEOL group) levels in (A). (E) Western blot of Nox4 expression (*p < 0.001). Top panel shows representative Western blots of Nox4 and GAPDH.

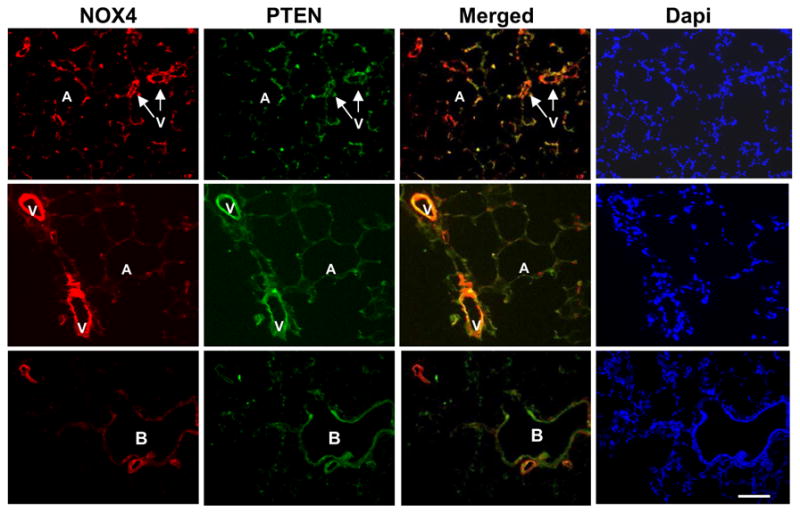

Nox4 co-localized with PTEN expression

Increased PTEN mRNA and protein expression paralleled the increase in Nox4 and oxidative DNA damage in irradiated lung tissue. Therefore, we sought to determine whether Nox4 and PTEN were co-localized within irradiated tissue. Dual staining of PTEN and Nox4 in tissue sections from irradiated lung showed co-expression of both proteins in pulmonary blood vessels and epithelial cells (Fig. 6).

Figure 6. Co-localization of NOX4 and PTEN.

Red fluorescence: Nox4; green fluorescence: PTEN. Yellow fluorescence: Overlay of the images Nox4 and PTEN. A, alveolus; B, bronchus; V, pulmonary vessel. Dapi shows the staining of nucleus.

Discussion

NADPH oxidases are important physiological producers of reactive oxygen species14. There are several members of the Nox family of NADPH oxidases including Nox1, Nox2/gp91phox, Nox3, Nox4, Nox5, and others. This study focused on Nox4, the NADPH oxidase isoform found primarily in vascular smooth muscle cells as well as myofibroblasts. Nox4 is a unique enzyme in that unlike other members of NADPH oxidases which produce superoxide anion, Nox4 produces hydrogen peroxide (H2O2)15. Nox4-derived H2O2 has been shown to play a key role in TGF-β1 mediated apoptosis and fibroproliferative disease5, 15. Over the past decade, we and others have conducted a number of studies showing that radiation-induced lung injury could be mitigated through inhibition of TGF-β116 or catalytic scavenging of free radical species17. TGF-β1 is activated within minutes following the transient ionizing event18 and its expression and activation is sustained throughout the course of disease progression9. Therefore, we hypothesized that scavenging free radicals with AEOL10150, a potent superoxide dismutase mimetic, might reduce Nox4 expression and cell death in lung tissue following thoracic radiation.

In the current study, Nox4 expression was observed in pulmonary blood vessels and epithelial cells of lung tissue six weeks after thoracic irradiation (Figs. 5, 6). In contrast, no significant difference was observed in Nox4 and TGF-β1 expression between sham-irradiated and irradiated lung tissue from mice treated with AEOL10150 (Fig. 5). Based on previous studies implicating ROS in TGF-β1 activation18, we hypothesize Nox4-produced ROS might contribute to the observed increase in TGF-β1 post-radiation.

It is well known that radiation induces cell apoptosis, however, the underlying mechanisms leading to cell death during are not well defined. In this study, we observed a significant number of apoptotic nuclei in lung tissue 6 weeks following radiation exposure (Fig. 1). The number of apoptotic cells observed at 6 weeks was significantly decreased when treatment with AEOL10150 was started 2 hours after radiation (Fig. 1). Apoptosis appeared to be predominantly localized to type I pneumocytes, and more moderately, to type II pneumocytes and endothelial cells (Fig. 2).

The most important finding in this study was the increase in PTEN expression in irradiated lung tissue (Fig. 3). This correlated with a decrease in ILK activity and reduced phosphorylation of Akt at Ser473 and Thr308 (Fig. 4) in irradiated lung tissue. In contrast, no changes were observed in PI3K activity as determined by phosphorylation of the p85/55 subunits (data not shown). This suggests that reduction in Akt activity occurred downstream of PI3K and was most likely mediated by PTEN –induced dephosphorylation of PIP3. In healthy tissue, Akt negatively regulates apoptosis and promotes survival by enhancing the degradation of p53 and negatively regulating Bax levels19. In this study, p53 and Bax protein were both increased in irradiated lung tissue (Fig. 4).

The reduction in PTEN expression and decrease in apoptotic cells when AEOL10150 was started 2 hours after radiation suggests oxidative stress may contribute to PTEN/PI3K/Akt signaling in irradiated lung. Furthermore, treatment with AEOL10150 significantly reduced TGF-β1 and Nox4 expression in irradiated tissue (Fig. 4, 5) further implicating oxidative stress in regulation of these proteins after radiation.

Apoptosis has been shown to be an important contributor to fibrotic lung disease5, 20; however, the role of cell death in the development of normal tissue injury after radiation remains unclear. Normal tissue homeostasis involves generation of growth factors in response to apoptotic cell recognition. For example, phosphatidylserine exposed on the surface of apoptotic cells can induce profibrogenic TGF-β1. This has been observed in a variety of lung diseases in which local or generalized fibrosis occurs21.Therefore, the precise signaling mechanisms which lead to radiation-induced cell death following thoracic irradiation need to be further investigated. Based on the literature, we hypothesize that activation of TGF-β1 and Nox4, and subsequent cell death might be a cyclical process that can be interrupted through ROS/RNS scavenging in the first few weeks post-radiation. Singularly disrupting each step of the proposed sequence of events is the subject of future studies with the aim of identifying the precise sequence of events which lead to radiation-induced cell death.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grant U19-AI067798 and by AEOLUS Pharmaceuticals.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

ILJ is a consultant for AEOLUS Pharmaceuticals, Inc. All other authors have declared no competing interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.O’Brien TJ, Letuve S, Haston CK. Radiation-induced strain differences in mouse alveolar inflammatory cell apoptosis. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2005;83(1):117–122. doi: 10.1139/y05-005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steelman LS, Bertrand FE, McCubrey JA. The complexity of PTEN: mutation, marker and potential target for therapeutic intervention. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2004;8(6):537–550. doi: 10.1517/14728222.8.6.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Escriva M, Peiro S, Herranz N, et al. Repression of PTEN phosphatase by Snail1 transcriptional factor during gamma radiation-induced apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28(5):1528–1540. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02061-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brandes RP, Takac I, Schroder K. No superoxide--no stress?: nox4, the good NADPH oxidase! Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31(6):1255–1257. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.226894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carnesecchi S, Deffert C, Donati Y, et al. A key role for NOX4 in epithelial cell death during development of lung fibrosis. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011 doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Serrander L, Cartier L, Bedard K, et al. NOX4 activity is determined by mRNA levels and reveals a unique pattern of ROS generation. Biochem J. 2007;406(1):105–114. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carmona-Cuenca I, Roncero C, Sancho P, et al. Upregulation of the NADPH oxidase NOX4 by TGF-beta in hepatocytes is required for its pro-apoptotic activity. Journal of Hepatology. 2008;49(6):965–976. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Batinic-Haberle I, Spasojevic I, Tse HM, et al. Design of Mn porphyrins for treating oxidative stress injuries and their redox-based regulation of cellular transcriptional activities. Amino Acids. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s00726-010-0603-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fleckenstein K, Zgonjanin L, Chen L, et al. Temporal onset of hypoxia and oxidative stress after pulmonary irradiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;68(1):196–204. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.12.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rabbani ZN, Batinic-Haberle I, Anscher MS, et al. Long-term administration of a small molecular weight catalytic metalloporphyrin antioxidant, AEOL 10150, protects lungs from radiation-induced injury. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;67(2):573–580. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.09.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang X, Mi J, Wetsel WC, et al. PI3 kinase is involved in cocaine behavioral sensitization and its reversal with brain area specificity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;340(4):1144–1150. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.12.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen Q, Xiong X, Lee TH, et al. Neural plasticity and addiction: integrin-linked kinase and cocaine behavioral sensitization. J Neurochem. 2008;107(3):679–689. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rabbani ZN, Salahuddin FK, Yarmolenko P, et al. Low molecular weight catalytic metalloporphyrin antioxidant AEOL 10150 protects lungs from fractionated radiation. Free Radic Res. 2007;41(11):1273–1282. doi: 10.1080/10715760701689550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manoury B, Nenan S, Leclerc O, et al. The absence of reactive oxygen species production protects mice against bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Respir Res. 2005;6:11. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-6-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thannickal VJ, Fanburg BL. Activation of an H2O2-generating NADH oxidase in human lung fibroblasts by transforming growth factor beta 1. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(51):30334–30338. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.51.30334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andarawewa KL, Paupert J, Pal A, et al. New rationales for using TGFbeta inhibitors in radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Biol. 2007;83(11–12):803–811. doi: 10.1080/09553000701711063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robbins ME, Zhao W. Chronic oxidative stress and radiation-induced late normal tissue injury: a review. Int J Radiat Biol. 2004;80(4):251–259. doi: 10.1080/09553000410001692726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barcellos-Hoff MH, Dix TA. Redox-mediated activation of latent transforming growth factor-beta 1. Mol Endocrinol. 1996;10(9):1077–1083. doi: 10.1210/mend.10.9.8885242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carnero A, Blanco-Aparicio C, Renner O, et al. The PTEN/PI3K/AKT signalling pathway in cancer, therapeutic implications. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2008;8(3):187–198. doi: 10.2174/156800908784293659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Griffith B, Pendyala S, Hecker L, et al. NOX enzymes and pulmonary disease. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11(10):2505–2516. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Freire-de-Lima CG, Xiao YQ, Gardai SJ, et al. Apoptotic cells, through transforming growth factor-beta, coordinately induce anti-inflammatory and suppress pro-inflammatory eicosanoid and NO synthesis in murine macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(50):38376–38384. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605146200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.