Abstract

Perforations of nasal septum are fairly frequent with an incidence of about 0.9 % and may lead to morbidity than mortality. Common causes are trauma (iatrogenic occasionally nose picking), malignancy, inflammations and infections such as tuberculosis, syphilis, Wegener’s granulomatosis, sarcoidosis and fungal infections. Paranasal fungal sinusitis is frequently encountered in clinical practice in both immunocompromised and immunocompetent individuals. Nasal septal perforations caused by species of Aspergillus and Fusarium have been documented. We report a case of nasal septal perforation in a 35-years-old immunocompetent male patient due to Purpureocillium lilacinum, a soil and environmental fungus and an emerging pathogen, which is known to cause various infections in humans with normal and deficient immune system. Fungal aetiology was diagnosed by histopathology and direct smear examination and confirmed by culture. Patient was treated with voriconozole, following Antifungal susceptibility testing (AFST), to which the patient is responding.

Keywords: Purpureocillium lilacinum, Nasal septal perforation, Immunocompetent

Introduction

Nasal septal perforations are a challenge to Otorhinolaryngologists. They may be asymptomatic or cause various symptoms, which may be of aesthetic and functional problem. Fungal infections in the sino-nasal cavities may be caused by opportunistic and emerging fungi, both in immunocompromised and immunocompetent individuals [1, 16]. Invasive fungal sinusitis due to Aspergillus spp and Fusarium solani leading to nasal septal perforation in immunocompromised person has been reported [2, 3].

Purpureocillium lilacinum is an emerging, opportunistic fungal pathogen known to cause various infections in both immunocompromised and immunocompetent humans [1, 6, 9]. Rarely, it can cause infection of sino-nasal cavity. Here, we report a case of nasal septal perforation secondary to P. lilacimun infection in a 35-years-old, immunocompetent male patient who responded well to voriconazole treatment.

Case Report

A 35-years-old male was presented to the department of ENT with a history of

Swelling and excruciating pain over the tip of the nose, of one month duration.

Mild nasal obstruction of two weeks duration.

Past History

Patient gave history of swelling in the medial canthus of the right eye two months before, which was treated by an Ophthalmologist and the excised mass was reported as candidal dacryocystitis on histopathological examination. Culture was not done and patient did not receive any antifungal drugs.

On ENT Examination

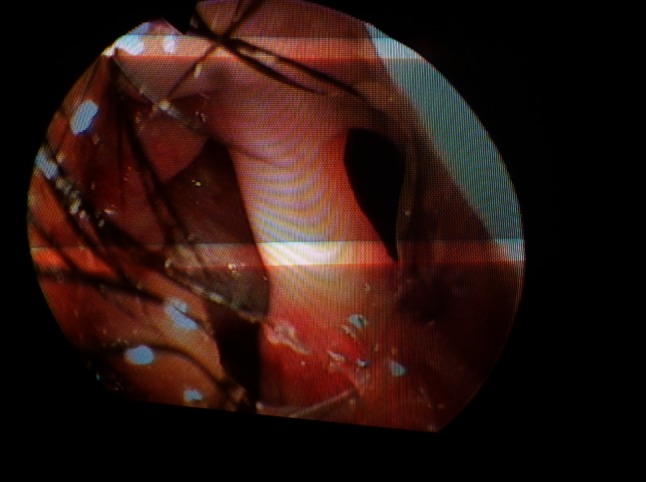

Tip of the nose showed diffused swelling of 2 cm diameter and was red in colour (Fig. 1). Nasal examination revealed foul smelling scanty discharge was along with crusts. Since the swelling was tender, endoscopy could not be done. Preliminary diagnosis of Nasal Vestibulitis with secondary infection was made and Nasal swab was sent for microbiological examination. Other routine investigations were done. Hb %, TC, DC, ESR and Platelet count were under normal limits; FBS and PPBS were under normal range; LFT, RFT were normal; HIV and HBsAg were negative and VDRL and TPHA were non-reactive; X-ray of Paranasal sinus (PNS) and CT PNS were normal. Patient was started on Cefixime and Metronidazole.

Fig. 1.

Showing diffuse swelling over the nasal tip

After 3 days, pain had reduced and nasal endoscopy was attempted. Endoscope could be passed only up to the vestibule and revealed crusting in both the nasal cavities and two perforations, one measuring about 2 × 4 mm and the other, about 6 × 8 mm in the cartilaginous part of the nasal septum (Fig. 2). Edges of the perforation were granular in appearance and from this site; a bit of tissue biopsy was taken and sent for histopathological examination and also for culture and sensitivity.

Fig. 2.

Showing nasal septal perforations

Report

Histopathological Examination

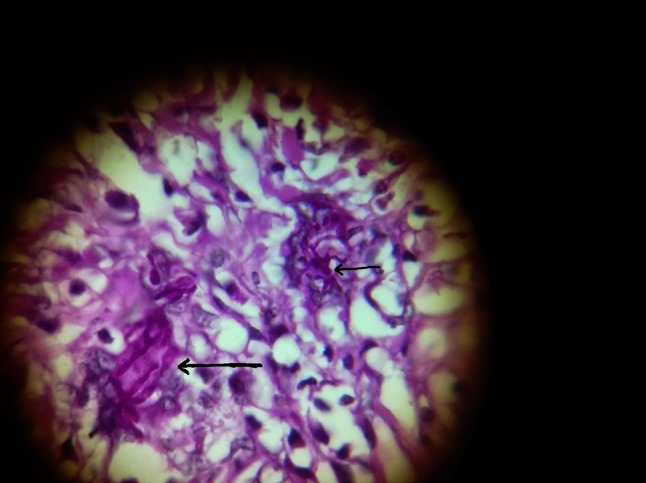

Haematoxylin and Eosin stain showed cartilage with granulation tissue consisting of blood vessels with chronic inflammatory cells comprising of lymphocytes, macrophages and few foreign body type giant cells. Periodic Acid Schiff stain showed filamentous fungal hyphae within the giant cells and also extracellularly (Fig. 3). The impression was chronic infection of fungal aetiology.

Fig. 3.

PAS stained tissue section showing fungal elements

Microbiological Examination

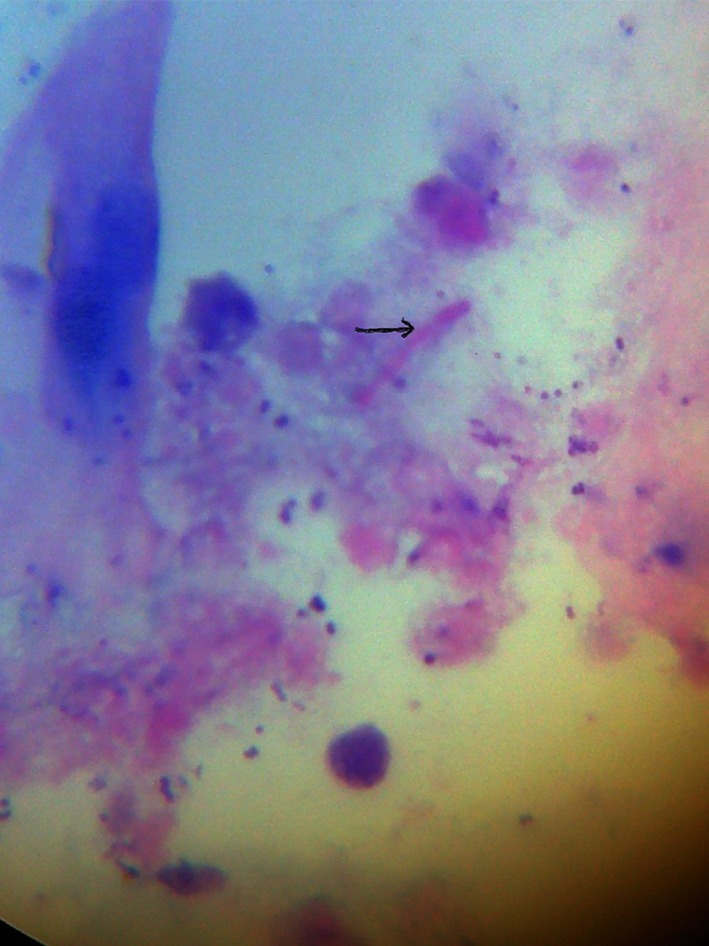

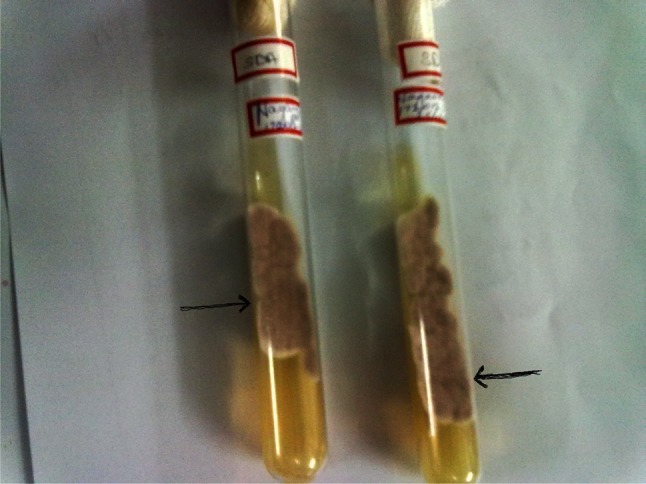

Direct Grams smear of nasal secretion showed plenty of pus cells with gram positive cocci in cluster and gram negative bacilli along with septate fragmented fungal hyphae (Fig. 4). 10 % KOH mount showed short segments of septate hyphae with occasional branching. Bacterial culture yielded Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Fungal culture on Sabouraud’s Dextrose Agar yielded P. lilacinum with in 3–4 days. Nasal septal biopsy specimen also yielded P.lilacinum. Growth was typical showing powdery, floccose, lilac coloured colony (Fig. 5). Lactophenol cotton blue mount showed septate hyaline hyphae of moderate thickness and infrequent branching with conidiophores swollen at their bases. Phialides arose from these conidiophores and had long chains of purple coloured conidia (Fig. 6). Antifungal susceptibility testing (AFST) was performed and the MIC result was as follows:

Amphotericin B (10.8 lg/ml).

Fluconazole (160 lg/ml).

Itraconazole (7.2 lg/ml).

Voriconazole (0.04 lg/ml).

Fig. 4.

Gram’s stained smear showing hyphal elements

Fig. 5.

Growth of P. lilacinum on SDA

Fig. 6.

Microscopic appearance of P. lilacinum in LCB mount

Patient was started on Ketoconazole 400 mg/day following direct smear report and Voriconazole was replaced for Ketoconazole following culture and AFST report. Patient was reviewed after 2 and 4 weeks of treatment. Swelling and pain had decreased and patient was asked to continue with Voriconazole and asked to come for regular follow up.

Discussion

Nasal septum perforation is not infrequent and occurs in around 34 % of cases in cartilaginous part. Trauma such as self induced external nose picking or facial accidents may result in lacerations of the mucosa. Interference of blood supply or ischemia of the mucoperichondrium may also result in perforation. Nasal surgeries, nasal intubation, placement of nasogastric tubes etc., sometimes result in injury leading to perforation. Septal haematoma, if not attended, may get infected and lead to perforation. Rarely tuberculosis, syphilis, Wegener granuloma and sarcoidosis are implicated as a cause perforation. Inhalation of irritants such as chromic or sulphuric acid fumes, glass dust, mercurials, phosphorous may sometime cause perforation. Cocaine and vaso-constrictive nasal spray often cause large perforations. Nasal septum perforation may also be a presenting symptom of AIDS [4].

Once perforation occurs due to various causes, mucosal edges epithelialize preventing closure of the defect. Altered nasal airflow results in symptoms. Posterior perforations are less symptomatic than anterior ones because of humidification from the nasal mucosa and turbinates. Nasal obstruction, crusting, epistaxis, foul smelling nasal discharge, parosmia and neuralgia are the common symptoms. Small perforations can cause whistling sound with inspiration. Long standing perforation may result in saddle-nose deformity which is an aesthetic and functional problem.

Opportunistic fungi of low virulence, distributed widely in soil and environment, do cause infection in immunocompromised persons including AIDS patients. They are also becoming emerging pathogens, causing infection in humans with normal immune system. Fungal infections of sino-nasal cavities, both in immunocompromised and immunocompetent, are not rare. Nasal septal perforations in very few cases have been caused by fungus like Aspergillus spp and F. solani [2, 3].

The genus Purpureocillium [5], earlier known as Paecilomyces, was first described by Bainer in 1907 [6]. They are saprophytic fungi found worldwide in soil and decomposing vegetation. They belong to Hyphomycetes. They usually occur as laboratory contaminants, in sterile solutions and clinical specimens. Recently Purpureocilliumspp have been reported to cause infections in immunocompromised and immunocompetent individuals, virtually in all the body sites [7]. Five species of this genus have been identified which can cause infection in humans [8]. Among these, P. variotii and P. lilacinum are more common.

P. lilacinum, an opportunistic and emerging pathogen, has been known to cause infections in persons with both normal and deficient immune system, particularly in patients with indwelling foreign devices or following intraocular lens implants. [9–11] Paecilotoxin is the mycotoxin produced from this fungus, but its significance in causing human infection is not known [12]. Some of the infections caused in humans are cutaneous and subcutaneous lesions, vaginitis, endophthalmitis, fungemia, onychomycosis, keratitis, bursitis and sinusitis, etc. [13–15].

Fungal infections of the sino-nasal cavity are frequently encountered in ENT department. Over the past 30 years only six cases of Purpureocillium spp infection in sino-nasal tract have been reported-four cases of P. lilacinum and two cases of P. variotii. [16–19] Nayak, et al. in 2000, has described a case of unilateral sinusitis and proptosis in an immunocompetent child. Fungal maxillary sinusitis due to P. lilacinum in an immunocompetent host presented as subcutaneous swelling has been reported by Permi HS, et al.

Here is a case of nasal septal perforation proposed due to P. lilacinum in a 35-years-old immunocompetent male. Identification of hyphae in direct smear is always challenging as it is very difficult to differentiate Purpureocilliumspp from Aspergillus, Zygomycetes and Pseudohyphae of Candida. Culture is confirmative [20]. In our case, direct smear identification was confirmed by typical colony morphology and microscopic features in lactophenol cotton blue mount. P. lilacinum is known for its drug resistance. It is resistant to conventional antifungal drugs and also to sterilization methods [21]. AFST by MIC method was done and it was sensitive to itraconozole and voriconazole.

Conclusion

We would like to conclude that P.lilacinum, an emerging fungal pathogen, can cause infection in nasal sinuses and nasal cavity probably resulting in nasal septal perforation in immunocompetent individuals. High degree of suspicion is needed to identify the fungus by histopathological examination. Culture is confirmatory. Treatment with traditional antifungal drugs often fails but voriconazole and itraconazole are effective.

Contributor Information

Aparna Shivaprasad, Email: aparna.prasad4@gmail.com.

G. C. Ravi, Email: drgcravi@gmail.com

Shivapriya, Email: shivapriya69@rediffmail.com.

Rama, Email: drnk.rama@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Permi HS, Sunil KY, Karnakar VK, Kishan PHL, Teerthanath S, Bandary SK. A rare case of fungal maxillary sinusitis due to Paecilomyces lilacinus in an immunocompetent host, presenting as a sub-cutaneous swelling. J Lab Physicians. 2011;3(1):46–48. doi: 10.4103/0974-2727.78566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuo WT, Lee TJ, Chen YL, Huang CC. Nasal septal perforation caused by invasive fungal sinusitis. Chang Gung Med J. 2002;25(11):769–773. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ruiz N, Martos CF, Romero I, Pla A, Maiqez J, Calatrava A, Guillem V. Invasive fungal infection and nasal septal perforation with Bevacizumab-based therapy in advanced colon cancer. J Clin Onco. 2007;25(22):3376–3377. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rejali SD, Simo R, Saeed AM, de Carpentire J. Acquired immuno deficiency syndrome (AIDS) presenting as a nasal septal perforation. Rhinology. 1999;37:93–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luangsa-Ard J, Houbraken J, van Doorn T, Hong SB, Borman AM, Hywel-Jones NL, Samson RA. Purpureocilliun, a new genus for the medically important Paecilomyces lilacinus. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2011;321:141–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2011.02322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Varkey JB, Perfect JR. Rare and emerging fungal pulmonary infections. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;29:121–131. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1063851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carey J, D’Amico R, Sutton D, Rinaldi MG. Paecilomyces lilacinus vaginitis in an immunocompetent patient. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:1155–1158. doi: 10.3201/eid0909.020654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu K, Howell DN, Perfect JR, Schell WA. Morphologic criteria for the preliminary indetification of Fusarium, Paecilomyces and Acremonium species by histopathology. Am J Clin Pathol. 1998;109:45–54. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/109.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Day DM. Fungal endophthalmitis caused by Paecilomyces lilacinus after intraocular lens implantation. Am J Ophthalmol. 1977;83(1):130–131. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(77)90206-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pettit TH, Olson RJ, Foos RY, Martin WJ. Fungal endophthalmitis following intraocular lens implantation. A surgical epidemic. Arch ophthalmol. 1980;98(6):1025–1039. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1980.01020031015002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fleming RV, Walsh TJ, Anaissie EJ (2002) Emerging and less common fungal pathogens. Infect Dis Clin North Am 16(4):915–933 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Mikami Y, Yazawa K, Fukushima K, Ari T, Udagawa S, Samson RA. Paecilotoxin production in clinical or terrestrial isolates of Paecilomyces lilacinus strains. Mycopathologia. 1989;108(3):195–199. doi: 10.1007/BF00436225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ciecko SC, Scher R (2010) Invasive fungal rhinitis caused by Paecilomyces lilacinus infection: Report of a case and a novel treatment. Ear Nose Throat J 89(12):594–595 [PubMed]

- 14.Orth B, Frei R, Itin PH, Rinaldi MG, Speck B, Gratwohl A, Widmer AF. Outbreak of invasive mycoses caused by Paecilomyces lilacinus from a contaminated skin lotion. Ann Inter Med. 1996;125(10):799–806. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-125-10-199611150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roque J, Navarro M, Toro G, Gonzalez I, Pimstein M, Venegas E. Paecilomyceslilacinus systemic infection in a Immunocompromised child. Rev Med Chil. 2003;131(1):77–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gucalp R, Carlisle P, Gialanella P, Mitsudo S, Mckitrick J, Dutcher J. Paecilomyces sinusitis in an immunocompromised adult patient: Case report and Review. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;23(2):391–393. doi: 10.1093/clinids/23.2.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rockhill RC, Klein MD. Paecilomyces lilacinus as the cause of chronic maxillary sinusitis. J Clin Microbiol. 1980;11:737–739. doi: 10.1128/jcm.11.6.737-739.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rowley SD, Strom CG. Paecilomyces fungus infection of the maxillary sinus. Laryngoscope. 1982;92:332–334. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198203000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pastor FJ, Guarro J. Clinical manifestations, treatment and outcome of Paecilomyces lilacinus infections. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2006;12(10):948–960. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2006.01481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saberhagen C, Klotz SA, Bartholomew W, Drews D, Dixon A. Infection due to Paecilomyces lilacinus: a challenging clinical identification. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:1411–1413. doi: 10.1086/516136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ezzedine K, Belin E, Guillet S, D’Almeida M, Droitcourt C, Accocebery I, Milpied B, Jouary T, Malvy D, Taieb A. Cutaneous hyphomycosis due to Paecilomyces lilacinus. Acta Derm Venereol. 2012;92:156–157. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]