Abstract

Despite repeated emphasis in the Dietary Guidelines for Americans on the importance of calcium in the adult American diet and the recommendation to consume 3 dairy servings a day, dairy intake remains well below recommendations. Insufficient health professional awareness of the benefits of calcium and concern for lactose intolerance are among several possible reasons, This mini-review highlights both the role of calcium (and of dairy, its principal source in modern diets) in health maintenance and reviews the means for overcoming lactose intolerance (real or perceived).

Introduction

The Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA) are published every 5 y with the intent both to inform the American public and to improve the adequacy of their food intakes (1, 2). The explicit presumption is that adequate nutrition is essential for extending life span, promoting health, and reducing the risk of many chronic diseases. It is disappointing to realize that the public seems to be unmoved by this message. Certain nutrients, labeled “nutrients of concern,” have consistently been identified, time after time, as being inadequately consumed across broad swaths of the population, despite the use of various visual devices (pyramids and plates) intended to make the recommendations concrete. These concerns date back to at least 1990 in the federal government’s 10-y plan “Healthy People 2000” (3).

One of those persisting shortfall nutrients is calcium, the importance of which was highlighted as far back as the 1984 Consensus Development Conference on Osteoporosis (4), reiterated in the 1994 Consensus Conference on Optimal Calcium Intake (5), and emphasized once again the 2004 Surgeon General’s Report on Bone Health and Osteoporosis (6), which notes explicitly: “Calcium has been singled out as a major public health concern today because it is critically important to bone health and the average American consumes levels of calcium that are far below the amount recommended for optimal bone health.”

Dairy foods, particularly fluid milk, yogurt, and cheese, are the principal sources of calcium in the diets of the industrialized nations, and without a high dairy diet, it is difficult to come close to recommended calcium intakes. In its 1995 edition, the DGA recommended 2 to 3 servings of dairy foods per day for every American older than 9 y of age (7), a figure that was increased to 3 full servings in the 2005 edition (and carried forward into the 2010 as well). The Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee stressed, in its emphasis on dairy intake, that it was not just calcium that was at issue, but a multitude of other nutrients as well (2). They noted, specifically, that it would be difficult to reach the recommended potassium intake without 3 servings of dairy in the diet.

This mini-review has as its purpose a reaffirmation of the importance of calcium (1, 2, 4–7), citing, in particular, several less well recognized benefits of an adequate calcium intake. Its goal is also to give health professionals a concise summary of the state of the science and some practical hints on how to help the public improve their calcium intakes.

Calcium intake and diet adequacy

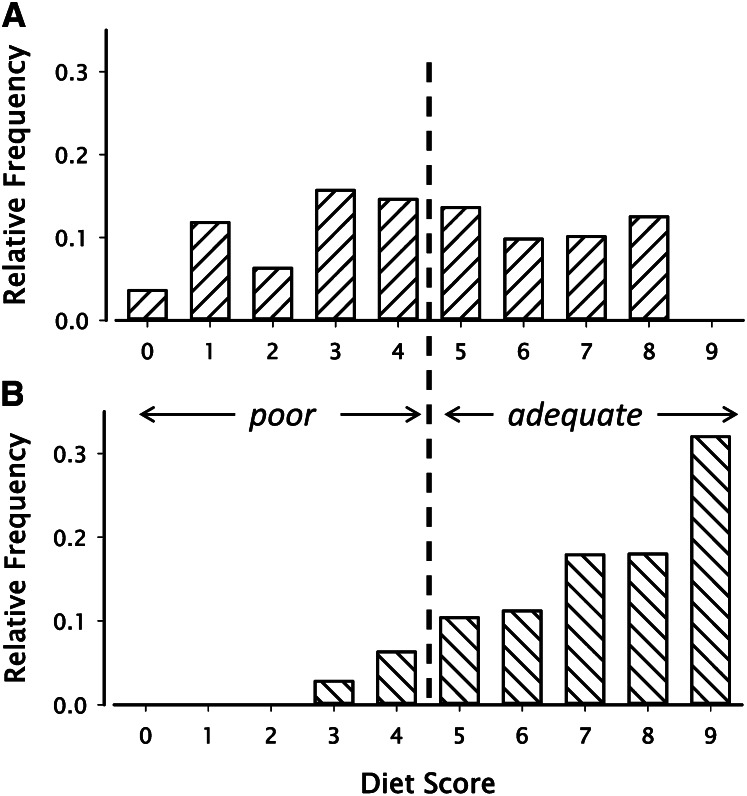

The importance of adequate calcium intake is demonstrated directly in studies of the total dietary adequacy of individuals who either do or do not come close to the recommended calcium intake (8, 9). Data from 1 of these studies (8), reproduced here as Figure 1, show clearly that calcium intake is actually a marker for dietary adequacy. Women failing to ingest at least two thirds of the recommended calcium intake each day (Fig. 1A) were ∼5 times more likely to have a poor diet, overall, than women ingesting at least two thirds of the recommended calcium intake (Fig. 1B). This linkage, as is generally recognized, is due to the fact that dairy foods are a rich source, not just of calcium, but of many nutrients, of which potassium, vitamin B-12, riboflavin, magnesium, phosphorus, and protein are the principal examples. (With the fortification of fluid milks with vitamin D for the past three quarters of a century and the recent trend to fortify yogurt and cheese as well, vitamin D must also be added to that list.) Table 1 lists the percentage of the current daily values for 9 key nutrients that would be provided by 3 servings of milk (or some yogurts) each day. If those dairy servings were of the low-fat variety, those impressively high fractions of total need would be met at an energy intake of <300 kcal. It is immediately apparent why a low-dairy diet runs a substantial risk of being a poor diet overall, as Figure 1 documents.

Figure 1.

Diet scores for 272 premenopausal women who either did (B) or did not (A) achieve a daily calcium intake of at least 67% of the daily value. Scores were computed by giving a value of 1 to each of 9 nutrients if intake was at least two thirds the recommended levels and a value of 0 if intake was less. Median quality score for those who had a calcium score of 1 was 8 (out of 9), whereas it was 4 (out of 9) for those who failed to average 67% of the daily value for calcium. Redrawn from the data of Barger-Lux et al. (8). Reproduced with permission.

Table 1.

Major dairy milk nutrients in 3 servings

| Nutrient | Percent DV |

| Calcium | 90 |

| Protein | 50 |

| Phosphorus | 75 |

| Potassium | 33 |

| Magnesium | 21 |

| Vitamin D | 87 |

| Vitamin A | 30 |

| Riboflavin | 78 |

| Vitamin B-12 | 60 |

It should be noted in passing that a single additional serving of dairy by these women would have salvaged most of the diets otherwise labeled “poor” (8, 9). By contrast, although there is clearly a role for calcium supplements in rounding out an otherwise adequate diet, the data of Table 1 make abundantly clear why calcium supplements alone are not a solution to the problem. Adding 300–500 mg calcium per day in the form of a supplement to the diets of those classified as poor in Figure 1 does very little to budge that poor status. In fact, as is discussed in the following, there is reason to question whether that extra calcium can produce its full benefits in the absence of some of the other nutrients that would automatically be ingested along with the calcium of dairy.

Despite the strength and clarity of this evidence and a huge body of similar studies, per capita dairy consumption has stubbornly resisted change. In NHANES 2005–2006, milk and yogurt consumption totaled 1.02 servings per day for all adults, with the value for women being a mere 0.93 servings per day (10). Dairy industry figures, which include more recent data (11), show that per capita consumption of milk (in pounds per person per year) was 605 in 2005 and just 604 six years later (2011). Perhaps the relative stability of dairy intake over the past 7 y could be considered evidence of some small success of the promotion of milk intake by advertising efforts such as the “Got Milk?” campaign, as long-range data show an otherwise steady reduction in U.S. dairy intake dating back to the late 1940s. Still, halting a decline is not the same thing as reversing it, and the DGA clearly call for the latter. Moreover, there is evidence that the downward trend in dairy intake is continuing in a particularly vulnerable sector of the population. Total school milk consumption has declined by nearly 4% from 2008–2009 to 2011–2012, despite a small increase in enrollment (12).

There are many factors that contribute to low dairy intake, including the extensive promotion of carbonated beverages (the per capita intake of which has increased >3-fold over the same 60-y period during which dairy intake has decreased), the decline in the practice of families having common meals, animal rights activism that has demonized use of animal products, the ignorance of health professionals as a group concerning the importance of dairy in ensuring dietary adequacy, and the perception of dairy intolerance by many members of the general public. Other reasons could be cited as well, but of them all, perhaps the 2 that are most readily susceptible to correction are the level of health professional knowledge and the issue of lactose intolerance. These 2 reasons are, in fact, closely linked, as improved awareness of the importance of adequate calcium intake would help inform the professional’s approach to the management of patients who complain of milk intolerance.

Health benefits of calcium and dairy

Although the importance of an adequate calcium intake has been summarized many times over the past 30 y (4–6, 13), there still seems to be less-than-adequate awareness in the professional community of both calcium’s benefits (which extend well beyond bone) and the food sources that might help an individual reach recommended intakes.

Bone health

The connection between calcium intake and bone health is intuitive (6). Calcium is the principal cation of bone, and without an adequate intake, it is not possible either to build or maintain a fully normal skeletal mass. But in addition to its importance for bone mass, there is a less well recognized, but actually probably more important, mechanism by which adequate calcium intake protects against osteoporotic fracture. Low calcium intake always induces an increase in parathyroid hormone secretion, and even when bone mass is nominally adequate, the effect of parathyroid hormone is to increase the rate of bone remodeling on trabecular surfaces (14). Resorption cavities into the sides of thin trabecular struts greatly weaken the entire strut, out of all proportion to the small reduction in bone mass. Reducing this remodeling activity directly lessens this particular source of fragility.

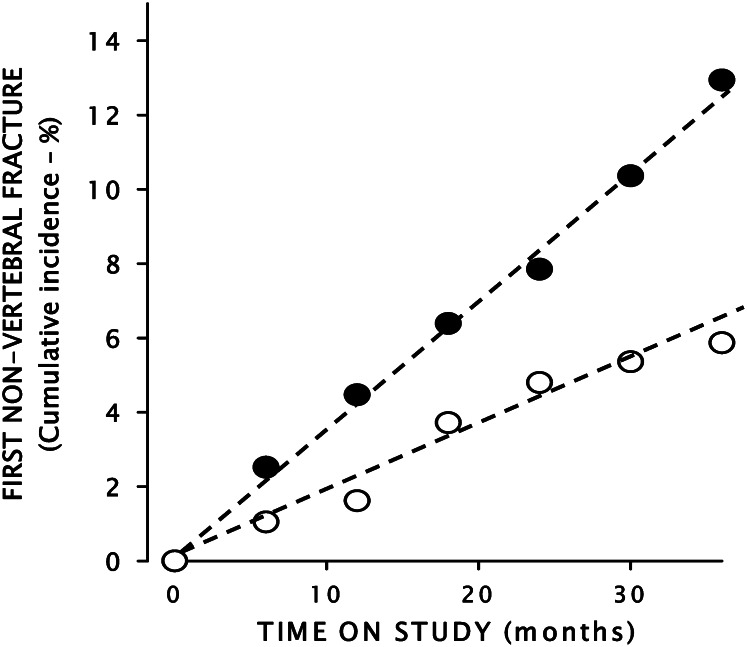

This reduction in remodeling is probably the reason fracture risk begins to decrease immediately after starting calcium supplementation in those trials that have demonstrated an antifracture benefit of calcium and vitamin D. Figure 2 illustrates this point. It shows the cumulative probability of nonvertebral fracture in a group of healthy older adults given both calcium and vitamin D supplementation (15). As can be seen, the regression lines through the points of the fracture incidence curves diverge from the very origin, well before there would have been time to increase bone mass sufficiently to reduce fracture risk.

Figure 2.

Time course of fracture events in the trial of Dawson-Hughes and Harris (16). The solid circles are for the placebo controls and the open circles for the calcium-treated group. The dashed lines represent the trend lines for the 2 contrast groups. Redrawn from the original data. Reproduced with permission.

This same study reveals a second important feature about the relationship of nutrition and bone health. In a secondary analysis of the original data, the investigators showed that bone loss in the placebo group was directly related to protein intake, that is, the greater the protein intake, the greater the bone loss (16). This may have been a reflection of the effect of protein on urine calcium excretion, occasionally reported (17). However, as protein intake increased, the calcium-treated arm of the study exhibited the opposite behavior. In the bottom 2 tertiles of protein intake [i.e., up to 1.16 μmol protein/(kg · d)], calcium essentially arrested bone loss. As repeatedly observed (6), it protected the skeleton. By contrast, the top tertile of protein intake in the calcium-supplemented group exhibited a substantial gain in bone mineral density.

It had long been a puzzle that, although calcium protected against bone loss, it did not seem able to restore lost bone (as iron supplements can restore lost hemoglobin). This positive interaction of calcium and protein, which has been confirmed in an independent data set (17), offers a possible explanation. Bone consists of protein as well as mineral; in fact, bone is ∼50% protein by volume. Bone proteins undergo extensive posttranslational modification as new matrix is synthesized and deposited. When that bone is later remodeled and its components are disassembled, the calcium and phosphorus can be recycled to provide mineral for other bone sites, currently in their forming phase. But many of the amino acids, having been modified, cannot. Thus, optimal new bone formation requires not only mineral, but a continuing supply of fresh dietary protein as well.

Dairy sources of calcium automatically provide both the needed mineral and the high-quality protein essential for maintenance of peak bone mass. Although it is yet to be shown prospectively that the combination of protein plus calcium can reverse the bone loss of osteoporosis, the data of Dawson-Hughes and Harris (16), described earlier, certainly raise that possibility.

Extraskeletal actions

Calcium, like most nutrients, is necessary for the optimal function of most body systems (18). Just a few instances need be cited here. The first relates to intraluminal functionality of unabsorbed calcium in the gut and the second to systemic effects of calcium (and particularly dairy intake) on blood pressure, insulin sensitivity, and the other components of the metabolic syndrome.

Intraluminal gut effects.

It is not commonly recognized that calcium absorption efficiency is actually quite poor, with net absorption averaging just 10%–11% of intake (19). This is partly a reflection of the fact that the ancestral calcium intake of the primates was high, and human physiology seems better adapted to prevent calcium intoxication than to deal with calcium deficiency. However, the unabsorbed calcium in the gut lumen is not simply wasted; specifically, it binds with potentially harmful products of digestion, such as unabsorbed fatty acids and bile acids, which when uncomplexed with calcium serve as cancer promoters in the colon. High calcium intakes, by binding those promoters, reduce the colon carcinogenic effect of known carcinogens in animal models (20). Presumably acting by a similar mechanism, calcium supplements have been shown to reduce the recurrence rate of colon polyps in humans (21).

Unabsorbed calcium forms complexes also with oxalic acid present in the digestate and renders it unabsorbable. Hence, not getting into the body, it does not have to be cleared through the kidneys. Urine oxalate is recognized as a potent stone-forming factor, and although the majority of urine oxalate is of endogenous origin, it nevertheless seems that the reduction in oxalate absorption from the gut is sufficient to reduce stone recurrence rates substantially (22).

Systemic effects.

Adequate calcium intakes also have been shown to exhibit systemic effects, such as lowering blood pressure (23, 24) and reducing the risk of preeclampsia (25). High calcium intakes, and specifically high dairy intakes, augment weight loss in calorie-reduced diets (26, 27), and high dairy intakes are associated with substantially reduced risk of all of the features of the metabolic syndrome (blood pressure, insulin resistance, and obesity) (28, 29). The literature on these topics is vast. My purpose here is simply to highlight the well-attested fact that low calcium intakes impair the functioning of many systems, not just bone.

Lactase nonpersistence, lactose malabsorption, and lactose intolerance

As noted at the outset, one of the reasons for failure to meet the recommendations of the DGA is milk intolerance. Is this a substantial problem, and, if so, what might be done about it?

Milk sugar, lactose, is a disaccharide that, to be absorbed across the intestinal mucosa, must be hydrolyzed into its component simple sugars (glucose and galactose). This split is accomplished by an enzyme, lactase, produced in the intestinal mucosa of essentially all young mammals (as lactose is the principal carbohydrate of mammalian milks). However, the production of lactase by mucosal cells decreases with age in most humans, and this decrease is particularly prominent in individuals of East Asian and African extraction. From 65% to 85% of adults of these races lack sufficient lactase to digest the lactose that would accompany the DGA’s recommended 3 servings.

The absence of adequate hydrolysis of lactose in the small intestine (where the enzyme is normally active) results in movement of undigested lactose into the distal bowel, where bacteria ferment the sugar, sometimes producing gas and symptoms such as cramps, bloating, flatulence, and diarrhea. The low level of lactase activity in the adults of much of the human race is termed lactase nonpersistence, and the fact that lactose is not hydrolyzed in the small bowel is termed lactose maldigestion. Lactose maldigestion is diagnosed medically by feeding a load of lactose by mouth and measuring breath hydrogen (one of the byproducts of bacterial fermentation of undigested lactose). If appreciable symptoms are produced in the process, the condition is termed lactose intolerance.

The lactose load used in tests to establish the fact of maldigestion has varied over the years, originally being close to the amount that would be delivered by ingesting a full quart of milk at a single sitting. Such large loads led to overdiagnosis of intolerance because actual intolerance is less likely to occur at lactose loads on the order of a single serving of milk (12 g lactose). This point highlights a key feature of lactose intolerance, namely, that it is a load phenomenon. Lactose loads <6 g (equivalent to one-half serving of milk) do not elicit symptoms, even in frankly intolerant individuals (30). Understanding this relationship to load is helpful in diagnosing patients who report abdominal distress. If that distress is produced by milk servings as small as a tablespoon or 2, then it is unlikely that lactose maldigestion is the cause of the patient’s symptoms. The term lactose intolerance, when applicable, is justified solely by the fact of maldigestion, which, in turn, is due to lactase nonpersistence. This understanding is of critical importance in any attempt to deal with the problem of lactose intolerance because the available regimens are all predicated on lactase nonpersistence.

Nicklas et al. (31), in an analysis of a nationally representative group of European American, African-American, and Hispanic adults reported that only 12%–13% had actual symptoms of lactose intolerance, despite the fact that the real prevalence of lactose maldigestion must have been several times higher. The symptomatic group could, presumably, be adequately handled by the measures that are described in the following, all of which are directed at the issue of lactase nonpersistence. The other 87%–88%, despite whatever degree of lactose maldigestion they may have, need no management at all, simply because they have no intolerance to be managed.

Unfortunately, the foregoing scheme is a less than fully adequate characterization of the situation, as many individuals who complain of what they consider to be lactose intolerance cannot be shown to have lactose maldigestion, and the basis of their complaints is thus uncertain. In a recent report from Italy (32), lactose maldigestion and lactose intolerance were found to be unrelated, with lactose maldigestion reported in 18% of 102 patients, and lactose intolerance in 29%. Many of the latter did not have lactose maldigestion. The principal distinguishing characteristic of the individuals with apparent intolerance, as reported by the investigators, was increased somatic awareness. Milk protein allergy, which could be a cause of symptoms that might be thought to be lactose intolerance, is another entity entirely and, so far as is known, is much less common than lactose intolerance. Hence it is unlikely to account for apparent intolerance without maldigestion. The allergy problem is not load dependent and, as with other food allergies, can result in severe symptoms on even very small exposures.

It is useful to understand that the principal health consequence of lactose intolerance is reduction of calcium intake brought about by milk avoidance. Unless adequacy of calcium intake is ensured by nondairy sources, the result is reduced bone density (33–35) and increased fracture risk (34). Calcium absorption itself is not affected by lactose intolerance or maldigestion (36, 37). Thus, the health professional’s goal is to find a way to increase dairy consumption in intolerant individuals.

The management of lactose intolerance due to lactose maldigestion has been described in detail elsewhere, perhaps most definitively in an NIH Consensus Development Conference on the topic (38). Individuals with symptoms of intolerance fall into 3 broad categories: 1) those who do not like milk and probably would not drink it even if they were not intolerant; 2) those who would like to drink milk occasionally, but probably would not meet the DGA’s 3-serving recommendation; and 3) those who like milk and would prefer to be able to drink it regularly. The first group requires no management, beyond finding alternative ways to meet their nutritional needs for calcium and the other nutrients that would otherwise be found in dairy. Hard cheeses (which are low in lactose) and active culture yogurts (which help with lactose digestion) are ways to do that within the dairy “franchise.” The second group also has the cheese and yogurt option, and, when they drink milk, can do so without symptoms if they choose lactose-free milk or take with their milk an over-the-counter tablet containing lactase (thereby supplying what their own intestine and its flora lack). Lactose-reduced and lactose-free milk, as well as lactase tablets, are readily available in grocery stores and/or pharmacies.

For the third group, the demonstrated best solution is to build up tolerance gradually over a period of as little as 2–3 wk. There are several factors in tolerance buildup, but probably the most important is the fact that lactose-containing meals favor the development of an intestinal flora that contains its own lactase, doing for its host on a regular basis what the lactase tablets do for the sporadic milk drinker (and at no out-of-pocket cost). Because of the short generation time of the intestinal bacteria, when lactose is present in the intestinal lumen, a small population of lactase-containing bacteria can out-compete the lactase-free forms within a period of just a few days, leading to the presence of an intestinal biome with sufficient lactase potential to handle its host’s dairy consumption. One proven way to accomplish this buildup is to add a half-glass of milk to 1 meal on the first day, a half-glass to each of 2 meals on the second day, etc., gradually increasing intake day by day. This strategy has been shown to reduce or stop entirely hydrogen gas production, thus abolishing the basis for intolerance (39, 40). Consuming milk with a meal slows release of lactose into the small intestine, and hence reduces the load to be digested at any given time, thereby decreasing the potential for intolerance. Some investigators report that chocolate milk is better tolerated than white, although the reason is unclear. Those with extensive experience managing patients with intolerance report that virtually every patient can be drinking 3 full servings a day within 2–3 wk of starting this regimen (41).

Additional measures that may be helpful include the use of probiotics that favor colonization with lactase-containing organisms and reliance on live-culture yogurts and hard cheeses (which are essentially lactose free) for 1 or more of the DGA’s recommended 3 servings.

A subset of individuals who once drank milk regularly and find now that they are intolerant consists mainly of adults who have recovered from a major illness or injury, often involving use of potent antibiotics. Probably most of these individuals had lost their own intestinal lactase years earlier, but because they continued to drink milk, they maintained a lactose-producing intestinal flora and did not realize that they were intrinsically lactase nonpersistent. However, it is likely that their lactase-producing organisms had been eliminated in the treatment of their recent illness. Re-establishing a normal flora after extensive antibiotic therapy can sometimes be more challenging than the simple changing of form of bacteria for another, as in the favoring of lactase-containing bacteria. Nevertheless, the same regimen will generally work reasonably well, although some additional measures such as fecal transplantation may sometimes be required. For these individuals, as well as anyone wishing to improve tolerance, probiotics may be helpful in addition to the gradual buildup of milk intake.

Conclusions

Inadequate dietary intakes, and particularly diets low in dairy foods, are implicated in and undoubtedly contribute to the burden of chronic disease in the industrialized nations. Although dairy is not the only way to achieve nutrient adequacy, still, given available foods and eating patterns, low dairy diets are almost always inadequate not only in calcium, but in multiple other nutrients as well. The most straightforward and most economical way to correct these inadequacies is, thus, be increased dairy intake.

Lactose intolerance is a perceived barrier, or is at least an excuse, for low dairy intake. Lactose intolerance, when it is due to lactose maldigestion, is generally managed relatively easily and hence eliminates one of the barriers impeding the achievement of dietary adequacy. Eloquent testimony to this conclusion is provided by the 2 consensus statements produced by the National Medical Association (42, 43), urging its members to adopt, for themselves, as well as for their patients, the DGA’s 3 servings recommendation.

Action Outcomes

Health professionals, particularly primary care practitioners and physician assistants, need to be educated to recognize the importance of adequate nutrition, not so much as a specific guarantee of better health, but as an activity akin to preventive maintenance of a complex machine, with its benefits most often realized not in dramatically better performance today but in fewer breakdowns later on and in extended healthy life.

Health professionals need, also, to understand that calcium is a crucial part of dietary adequacy and that it is difficult to achieve that adequacy for most of their patients if dairy foods are not consumed in adequate quantity.

Finally, health professionals need to recognize that lactose intolerance, whether real or perceived, should not be a significant barrier to improving dietary adequacy. They should understand also that lactose intolerance becomes irrelevant if their patients are unlikely to drink milk, despite the relative ease with which symptoms can often be abated when they do so. Such individuals require special attention from nutrition professionals, as it is not a simple task to achieve dietary adequacy without dairy, given contemporary foods and eating patterns.

Acknowledgments

The sole author had responsibility for all parts of the manuscript.

Literature Cited

- 1. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2005. 6th Edition, Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, January 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010. 7th Edition, Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, May 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and Public Health Service. Healthy People 2000. U.S. Government Printing Office, September 1990.

- 4.NIH Consensus Development Conference on Osteoporosis. JAMA. 1984;252:799–802 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.NIH Consensus Conference on Optimal Calcium Intake. JAMA. 1994;272:1942–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.U.S. Department of Health and Human ServicesBone Health and Osteoporosis: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 7.http://www.cnpp.usda.gov/DGAs1995Guidelines.htm (accessed 11/27/12)

- 8.Barger-Lux MJ, Heaney RP, Packard PT, Lappe JM, Recker RR. Nutritional correlates of low calcium intake. Clin Appl Nutr. 1992;2:39–44 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rafferty KA, Heaney JB, Lappe JM. Dietary calcium intake is a marker for total diet quality in adolescent girls and women across the life cycle. Nutr Today. 2011;46:244–51 [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dairy Research Institute (NHANES 2005–2008). Data Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Data. Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, [2005–2006, 2007–2008]. [ http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes.htm]

- 11. USDA Economic Research Service. Dairy Data. [cited 2012 Nov 27]. Available from: http://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/dairy-data.aspx.

- 12. 2011–2012 School Milk Product Profile, MilkPEP School Channel Survey. [cited 2013 22 Jan]. Available from: http://www.milkdelivers.org/schools/resources–links/

- 13. Weaver CM, Heaney RP, editors. Calcium in human health. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heaney RP. Is the paradigm shifting? Bone. 2003;33:457–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dawson-Hughes B, Harris SS, Krall EA, Dallal GE. Effect of calcium and vitamin D supplementation on bone density in men and women 65 years of age or older. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:670–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dawson-Hughes B, Harris SS. Calcium intake influences the association of protein intake with rates of bone loss in elderly men and women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;75:773–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heaney RP. Effects of protein on the calcium economy. In: Burckhardt P, Heaney RP, Dawson-Hughes B, editors. Nutritional aspects of osteoporosis 2006. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier Inc., 2007. p. 191–197.

- 18.Weaver CM, Heaney RP. Food sources, supplements, and bioavailability. In: Weaver CM, Heaney RP, editors. Calcium in human health. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press, 2006. p. 129–142.

- 19.Heaney RP, Nordin BEC. Calcium effects on phosphorus absorption: implications for the prevention and co-therapy of osteoporosis. J Am Coll Nutr. 2002;21:239–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lipkin M, Newmark H. Calcium and the prevention of colon cancer. J Cell Biochem Suppl. 1995;22:65–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baron JA, Beach M, Mandel JS, van Stolk RU, Haile RW, Sandler RS, Rothstein R, Summers RW, Snover DC, Beck GJ, et al. Calcium supplements for the prevention of colorectal adenomas. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:101–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Borghi L, Schianchi T, Meschi T, Guerra A, Allegri F, Maggiore U, Novarini A. Comparison of two diets for the prevention of recurrent stones in idiopathic hypercalciuria. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:77–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pfeifer M, Begerow B, Minne HW, Nachtigall D, Hansen C. Effects of a short-term vitamin D3 and calcium supplementation on blood pressure and parathyroid hormone levels in elderly women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:1633–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Appel LJ, Moore TJ, Obarzanek E, Vollmer WM, Svetkey LP, Sacks FM, Bray GA, Vogt TM, Cutler JA. A clinical trial of the effects of dietary patterns on blood pressure. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1117–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bucher HC, Guyatt GH, Cook RJ, Hatala R, Cook DJ, Lang JD, Hunt D. Effect of calcium supplementation on pregnancy-induced hypertension and preeclampsia. JAMA. 1996;275:1113–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen M, Pan A, Malik VS, Hu FB. Effects of dairy intake on body weight and fat: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;96:735–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Josse AR, Atkinson SA, Tarnopolsky MA, Phillips SM. Increased consumption of dairy foods and protein during diet- and exercise-induced weight loss promotes fat mass loss and lean mass gain in overweight and obese premenopausal women. J Nutr. 2011;141:1626–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Pereira MA, Jacobs DR, Van Horn L, Slattery ML, Kartashov AI, Ludwig DS. Dairy consumption, obesity, and the insulin resistance syndrome in young adults. The CARDIA Study. JAMA. 2002;287:2081–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Malik VS, Sun Q, van Dam RM, Rimm EB, Willett WC, Rosner B, Hu FB. Adolescent dairy product consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes in middle-aged women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94:854–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hertzler SR, Huynh BC, Savaiano DA. How much lactose is low lactose? J Am Diet Assoc. 1996;96:243–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nicklas TA, Qu H, Hughes SO, Wagner SE, Foushee HR, Shewchuk RM. Prevalence of self-reported lactose intolerance in a multiethnic sample of adults. Nutr Today. 2009;44:222–7 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tomba C, Baldassarri A, Coletta M, Cesana BM, Basilisco G. Is the subjective perception of lactose intolerance influenced by the psychological profile? Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36:660–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Honkanen R, Pulkkinen P, Järvinen R, Kröger H, Lindstedt K, Tuppurainen M, Uusitupa M. Does lactose intolerance predispose to low bone density? A population-based study of perimenopausal Finnish women. Bone. 1996;19:23–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Honkanen R, Kröger H, Alhava E, Turpeinen P, Tuppurainen M, Saarikoski S. Lactose intolerance associated with fractures of weight-bearing bones in Finnish women aged 38–57 years. Bone. 1997;21:473–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Enattah N, Pekkarinen T, Välilmäki MJ, Löyttyniemi E, Järvelä I. Genetically defined adult-type hypolactasia and self-reported lactose intolerance as risk factors of osteoporosis in Finnish postmenopausal women. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2005;59:1105–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Griessen M, Cochet B, Infante F, Jung A, Bartholdi P, Donath A, Loizeau E, Courvoisier B. Calcium absorption from milk in lactase-deficient subjects. Am J Clin Nutr. 1989;49:377–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tremaine WJ, Newcomer AD, Riggs BL, McGill DB. Calcium absorption from milk in lactase-deficient and lactase-sufficient adults. Dig Dis Sci. 1986;31:376–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Suchy FJ, Brannon PM, Carpenter TO, Fernandez JR, Gilsanz V, Gould JB, Hall K, Hui SL, Lupton J, Mennella J, et al. National Institutes of Health Consensus Conference: Lactose Intolerance and Health. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:792–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hertzler SR, Savaiano DR. Colonic adaptation to daily lactose feeding in lactose maldigesters reduces lactose intolerance. Am J Clin Nutr. 1996;64:232–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hertzler SR, Savaiano DA, Levitt MD. Fecal hydrogen production and consumption measurements. Response to daily lactose ingestion by lactose maldigesters. Dig Dis Sci. 1997;42:348–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pribila BA, Hertzler SR, Martin BR, Weaver CM, Savaiano DA. Improved lactose digestion and intolerance among African-American adolescent girls fed a dairy-rich diet. J Am Diet Assoc. 2000;100:524–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lactose intolerance and African Americans: implications for the consumption of appropriate intake levels of key nutrients. J Natl Med Assoc. 2009;101:5S–23S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wooten WJ, Price W. The role of dairy and dairy nutrients in the diet of African Americans. J Natl Med Assoc. 2004;96:5S–31S [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]