Abstract

National, state, and local institutions that procure, distribute, sell, and/or serve food to employees, students, and the public are increasingly capitalizing on existing operational infrastructures to create healthier food environments. Integration of healthy nutrition standards and other recommended practices [e.g., energy (kilocalories) postings at point-of-purchase, portion size restrictions, product placement guidelines, and signage] into new or renewing food service and vending contracts codifies an institution’s commitment to increasing the availability of healthful food options in their food service venues and vending machines. These procurement requirements, in turn, have the potential to positively influence consumers’ food-purchasing behaviors. Although these strategies are becoming increasingly popular, much remains unknown about their context, the processes required to implement them effectively, and the factors that facilitate their sustainability, especially in such broad and diverse settings as schools, county government facilities, and cities. To contribute to this gap in information, we reviewed and compared nutrition standards and other best practices implemented recently in a large school district, in a large county government, and across 10 municipalities in Los Angeles County. We report lessons learned from these efforts.

Introduction

Strategies comprising the implementation of standards and practices that are directed at improving the availability of healthful foods in institutions that procure, distribute, sell, and/or serve food to employees, students, and the public are increasingly becoming more popular and accepted approaches to creating healthier food environments (1–3). Collectively, they can be integrated as procurement requirements or best practices in an institution’s contractual and/or operational process. Emerging evidence suggests that these strategies may positively influence dietary choices among adults and children (4–16).

In this article, food procurement encompasses the process of procuring, distributing, selling, and/or serving food. It represents a synergistic nutrition strategy that capitalizes on existing operational infrastructures to make healthy eating the easy or “default” choice for individuals (17). Within this context, nutrition standards refer to codified limits for energy (kilocalories) and other nutrients such as sugar, sodium, and trans fat (1, 3). Food purchasing standards are requirements that adhere to these nutrient limits, but usually include other institutional considerations (e.g., costs, locally grown food, etc.). Other recommended practices in food procurement include broader environmental approaches that affect the distribution and selling of foods; they often include, but are not limited to energy (kilocalories) postings at point-of-purchase, portion size restrictions, guidelines for product placement, and signage to encourage selection of healthier items. These aspects of food procurement seek to encourage consumer (patron/customer/client) consumption of healthier foods (2, 16).

Although changing the food environment through these infrastructural mechanisms is not a new concept, the recent focus on health and sustainability is (3). Indeed, food procurement requirements or best practices have been examined in a number of studies, and used by federal and state administrative agencies to support food system changes (3, 8, 16, 18). The most recent example was the development and implementation of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and General Services Administration Health and Sustainability Guidelines for Federal Concessions and Vending Operations (3, 19). Some state legislatures and local jurisdictions have followed suit and taken similar actions, seeking to change the way in which food supply is procured, distributed, sold, and/or served by government entities such as jails, correctional facilities, distributive meal programs, concession services, and other food-related programs (16, 20).

Despite this growing attention to improving access to healthier foods through system-level changes, little is known about the actual process of adopting and implementing these healthier nutrition standards and recommended practices in the real world, especially across diverse settings (2, 3, 21). In this review article, we contribute to this gap in the evidence base by synthesizing what is currently known about an ongoing effort to advance healthy food procurement in Los Angeles County. Specifically, we examined and compared the differences, similarities, and lessons learned during the process of integrating nutrition standards and other practices in a large school district, in a county government, and across 10 municipalities in this local jurisdiction.

Current status of knowledge

Opportunity for change and to reach broadly

Los Angeles County is home to one of the most diverse populations in the nation, with ∼9.8 million residents and >100 different spoken languages (22, 23). Additionally, the region has 80 school districts, including the second largest in the nation, 88 incorporated cities, including the City of Los Angeles (∼3.8 million residents), and a large unincorporated area (22). Against this backdrop are transformative opportunities to create healthier food environments through system-level changes, many of which have the potential to broadly reach communities disproportionately affected by obesity and chronic disease (22, 24). Capitalizing on these opportunities, the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health (DPH)7 launched several healthy food procurement initiatives in the fall of 2010, leveraging key partnerships and resources to make strategic changes in the way the region’s 2 largest institutions, the County of Los Angeles government (22, 25) and the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD), and 10 municipalities procure, distribute, sell, and/or serve food. The intent and spirit of the DPH initiatives aligned closely with key national health objectives and were in part supported by ongoing efforts of several federal programs in obesity prevention and cardiovascular health promotion, specifically those by the CDC, which focused on sodium reduction and systems and environmental change strategies (18, 26, 27). In accordance with U.S. law, no federal funds provided by the CDC were used for lobbying or to influence, directly or indirectly, specific pieces of legislation at the federal, state, or local levels. Table 1 provides context to these initiatives and an overview of the 3 institutional settings selected for intervention.

Table 1.

Institutional structure, potential reach, and food environments across three institutional settings that implemented healthy nutrition standards and other food procurement practices in Los Angeles County, 2010–2012

| Institutional setting | Institutional structure | Potential reach | Food environment | |||

| Los Angeles Unified School District | Total no. of schools: ∼763 | Total no. of K–12 students: ∼644,233 | Approximate no. of meals served per day: ∼650,000 | |||

| Approximate no. of schools per grade level1: | Approximate no. of students targeted by grade level1: | Approximate no. of vending machines: ∼1000 | ||||

| • Elementary (grades K–5): ∼448 | • Elementary: ∼274,193 | |||||

| • Middle (grades 6–8): ∼85 | • Middle: ∼120,408 | |||||

| • High School (grades 9–12): ∼94 | • High school: ∼152,507 | |||||

| County of Los Angeles | Total no. of departments: 37 | Total no. of employees: 100,000 | Average no. of meals served per day in the selected settings/programs5: | |||

| Government | • Of total, approximate no. of departments that procure, distribute, sell, and/or serve food: 122 | Approximate no. of employees in departments that procure, distribute, sell, and/or serve food2: | • Worksite cafeterias: ∼1820 | |||

| Of departments that procure, distribute, sell, and/or serve food, approximate n that provide services to the following groups:23 | • Beaches and Harbors: ∼255 | • Mobile trucks: ∼2500 | ||||

| • Children: ∼3 | • Chief Executive Office: ∼501 | • Snack shops: ∼1000 | ||||

| • Seniors (age 65+): ∼1 | • Children and Family Services: ∼6,500 | • Jails: ∼80,000 | ||||

| • Institutionalized populations: ∼2 | • Community Development Commission: ∼480 | • Probation camps: ∼11,050 | ||||

| • Employees: ∼9 | • Community and Senior Services: ∼504 | • Hospitals: ∼35,089 | ||||

| • Community members/visitors: ∼4 | • Fire Department: ∼5000 | |||||

| • Health Services: ∼21,700 | ||||||

| • Parks and Recreation: ∼1461 | ||||||

| • Probation: ∼5800 | ||||||

| • Public Works: ∼5000 | ||||||

| • Sheriff’s Department: 18,000 | ||||||

| • Internal Services Department4: ∼2235 | ||||||

| Targeted/selected cities6 | Total no. of targeted/selected cities: 10 | Total no. of residents in targeted/selected cities7: 1,034,949 | Summary of nutrition standards established in targeted/selected cities | |||

| • Of total, no. of residents that are7: | Vending machines | |||||

| -Youths (<18 y): 270,282 | City | Entrées8 | Snacks | Beverages | ||

| -Adults (≥18 y): 764,667 | City 1910 | X1112 | X111213 | |||

| City 21014 | X1112 | X1112 | ||||

| City 3910 | X1112 | X1112 | X111213 | |||

| City 491014 | X1112 | X1112 | ||||

| City 591014 | X1112 | X1112 | ||||

| City 61415 | X1112 | X1112 | ||||

| City 71415 | X1112 | X111213 | ||||

| City 891014 | X1112 | X1112 | X111213 | |||

| City 91014 | X1112 | X1112 | X1112 | |||

| City 101014 | X1112 | X1112 | ||||

| Other concessions/food settings | ||||||

| City | Entrées8 | Snacks | Beverages | |||

| City 1910 | ||||||

| City 21014 | X1112 | X111216 | ||||

| City 3910 | X1112 | X1112 | X11121316 | |||

| City 491014 | X1112 | X111216 | ||||

| City 591014 | X111217 | X111217 | ||||

| City 61415 | ||||||

| City 71415 | X1117 | X111718 | ||||

| City 891014 | X1112 | X1112 | X11121316 | |||

| City 91014 | X1112 | X1112 | X111216 | |||

| City 101014 | X1112 | X1112 | ||||

Breakdown does not include all school types in Los Angeles Unified School District. For complete breakdown of schools, go to: http://notebook.lausd.net/pls/ptl/docs/page/ca_lausd/lausdnet/offices/communications/11–12fingertipfactsrevised.pdf.

Estimates based on an internal needs assessment of County of Los Angeles food service environments conducted in 2012.

Please note: overlap exists across groups served by departments; many departments provide services to multiple stakeholders and customers/clients.

Internal Services Department is the purchasing agent for multiple county departments that procure, distribute, sell, and/or serve food.

Estimates based on an internal needs assessment of County of Los Angeles food service environments conducted in 2009.

Cities include those that participate in the local obesity prevention and health promotion initiatives: Baldwin Park, Bell Gardens, El Monte, Huntington Park, La Puente, Long Beach, Pasadena, Pico Rivera, San Fernando, and South El Monte.

Calculated using U.S. Census data for each city.

Entrées include those served in all settings (e.g., city meetings, events, cafeterias, vending machines).

Mandates that all youth-oriented programs comply with nutrition standards.

Mandates that some or all city events/meetings/functions comply with nutrition standards.

Nutrition standards specific to youth-oriented city facilities.

Nutrition standards specific to city facilities that are not youth oriented.

Nutrition standards specify water (in any form) be available.

Mandates that all future food procurement or contractual negotiations meet nutrition standards.

Excludes nonpublic areas or those not under direct city control.

Nutrition standards specify tap water be provided as the preferred beverage whenever feasible.

Nutrition standards specific to youth-oriented meetings/classes/events.

Nutrition standards specify water to be available at all youth-oriented meetings/classes/events.

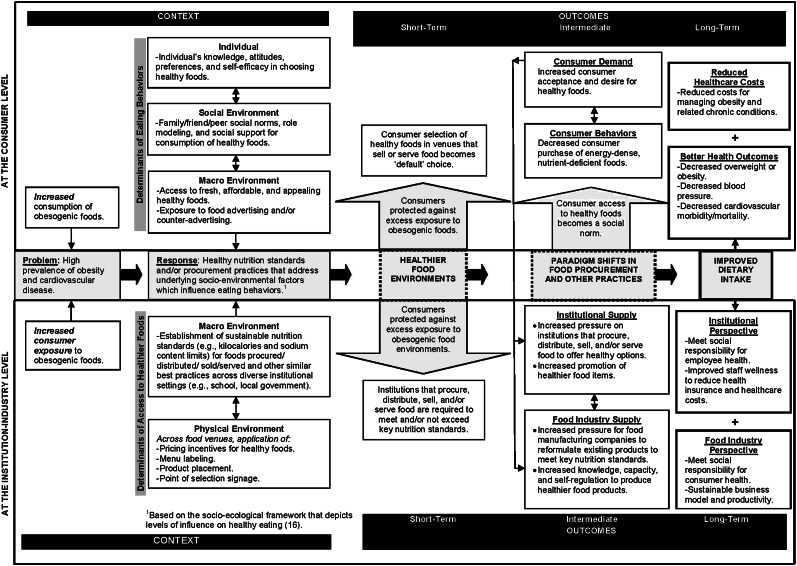

Framework for creating healthier food environments

Many of the obesity-related chronic conditions such as heart disease, stroke, and hypertension are associated with consumption of highly processed, energy-dense, and nutrient-deficient foods, which are often high in refined flours, caloric sweeteners, sodium, and trans fat (11, 28). Traditionally, obesity prevention efforts in public health have used health education and similar interventions to change individual knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about the harms and benefits of consuming these foods (17, 29). There is evidence, however, to suggest that these traditional approaches may not be sufficient to curb the weight gain that often leads to obesity (11, 17, 20, 29, 30). Rather, weight control among adults and children may require more comprehensive approaches at multiple levels that involve different sectors of society (e.g., government, health care, education) (11, 16, 20, 29, 30). This emerging viewpoint serves as a guide for the DPH’s food procurement initiatives. Figure 1 builds on this viewpoint and provides a logic framework that considers a range of complex pathways and interactions among individual behaviors, macro-level environments, and population health. An underlying premise for intervening at the level of the institution is the belief that increased demand for healthier food and beverage products can be promoted through organizational operation and contracting processes, making procuring, distributing, selling, and/or serving healthful foods an institutional priority and encouraging the food industry to reformulate, produce, and distribute more healthful food products (20, 21, 31, 32).

Figure 1.

Logic framework for the adoption and implementation of healthy nutrition standards and other recommended food procurement practices in institutional settings.

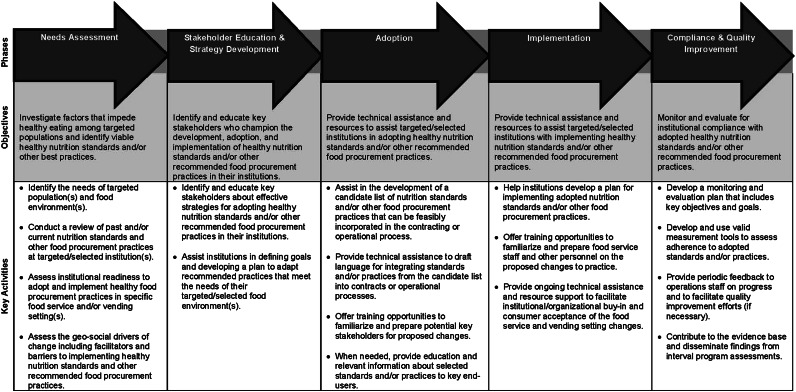

Steps to adopting and implementing nutrition standards and/or other food procurement practices

During 2010–2012, the DPH used a 5-phase process to assist targeted/selected institutions with the adoption and implementation of healthy nutrition standards and other best practices in food procurement (Fig. 2). These steps for making system-level changes in the way in which institutions procure, distribute, sell, and/or serve healthful foods were used in achieving the 2011–2012 menu changes at LAUSD, the Board motion that mandated public health reviews of new and renewing food service and vending contracts in the County of Los Angeles government (25), and the adopted/updated nutrition standards for vending and other concession food settings in 10 municipalities, albeit many of these latter standards were of variable intensity (Table 1). The 5-phase process was adapted from a framework used successfully by the DPH to help communities advance local tobacco control and chronic disease prevention efforts in Los Angeles County (33).

Figure 2.

A local health department’s approach to assisting institutions in adopting and implementing healthy nutrition standards and other recommended food procurement practices.

The 5-phase process.

In the first phase of the adoption and implementation process (needs assessment), the DPH investigated factors that contributed to unhealthy eating at the various targeted/selected institutions. Capitalizing on its health assessment capacity and access to real-time community health data, the Department identified the strategies, nutrition standards, and best practices recommended in the literature (11, 26, 27, 29) and vetted them with the leadership of each institution. Activities that were completed during this phase of the process included (but were not limited to): enumerating the magnitude of the obesity epidemic (the public health problem), presenting evidence in support of food procurement strategies and their health benefits, conducting a rigorous literature review of health and sustainability guidelines for use by institutional food services, and assessing the readiness of institutional leadership and staff to implement the proposed changes.

In the second phase of the process (stakeholder education and strategy development), the DPH leveraged its long-standing relationships with community partners to outreach and educate stakeholders in the targeted/selected institutions, specifically to help inform individuals who would champion the integration of healthier nutrition standards and/or other recommended practices in their institutions’ food and vending services. Activities that were completed during this phase included (but were not limited to): educating key stakeholders about effective strategies in food procurement, conducting educational presentations to institutional leadership to educate them about the proposed changes, and establishing a short-term as well as long-term social marketing plan to prepare end users and prospective consumers (e.g., cafeteria visitors, students and parents, other customers) for the proposed changes, when appropriate.

In the third phase of the process (adoption), the DPH provided technical assistance and resource support to targeted/selected institutions to help accelerate the adoption process. These supportive activities included (but were not limited to): helping to review the contract language (e.g., language to be included in the food service and vending contracts) and preparing key institutional champions for addressing staff and consumer concerns about the proposed changes. The DPH was fortunate to have among its staff members who have legal training in public policy and contract law.

During the fourth phase of the process (implementation), the DPH provided guidance on translating written standards and procedures into practice; one of its roles was to connect institutional personnel in charge of implementation with dieticians and experienced DPH or external staff that can provide ongoing technical advice.

The final phase of the process (compliance and quality improvement) is now under way. Periodic assessments of institutional adherence with the adopted standards and/or practices are planned. Through provision of feedback to targeted/selected institutions about their programs, this phase seeks to encourage quality improvement and programmatic refinements; the latter will be based on results from interval program assessments.

Review of nutrition standards and/or other recommended practices that were implemented in a school district, in the County government, and across 10 municipalities

During 2010–2012, each targeted/selected institution incorporated new or updated nutrition standards and recommended practices into their food service and vending processes, either through modifications of their administrative procedures or directly as part of the contracts with food vendors (Table 2). These changes in standards and practices, however, were not uniform across settings; they varied accordingly based on institutional priorities.

Table 2.

Comparison of healthy nutrition standards and other recommended practices in food procurement implemented across 3 institutional settings in Los Angeles County, 2010–2012

| Category | Public School District (Los Angeles Unified School District) | County Government (County of Los Angeles)1 | Municipalities (targeted/selected cities in Los Angeles County)2 |

| Nutrition standards for meals, entrées, and other food items | The following meals (by grade category) must meet recommended school nutrition standards3: | The following food categories must meet recommended nutrition standards6: | The following food categories must meet recommended nutrition standards: |

| • Elementary4 breakfast | • Main dish/entrées | • Entrées7 | |

| • Elementary4 lunch | • Side items | ||

| • Secondary5 breakfast | • Combination meals | ||

| • Secondary5 lunch | • Condiments | ||

| Snack and beverage nutrition standards | All snacks and beverages sold must follow nutrition standards that are aligned with district, state, and federal guidelines | All snacks and beverages sold must follow Los Angeles County DPH8 recommended nutrition standards and practices (including those for vending machines) | Select snacks and/or beverages sold must meet nutrition standards approved by each city council (standards vary by city) |

| Other recommended practices | The district adopted other recommended practices including, but limited to, the following: | Select departments with DPH reviewed food service and vending contracts were asked to integrate the following practices: | Cities were recommended to integrate healthy food procurement practices and other wellness activities, including9: |

| • Purchasing of locally grown foods. | • Menu labeling | • Dissemination of information on healthier foods and beverages to staff and facility participants | |

| • Increasing variety, visibility, and accessibility to fresh fruits and vegetables | • Purchasing of locally grown foods | • Training to ensure staff comprehension and compliance with adopted standards | |

| • Providing vegetarian options | • Signage and product placement that promotes healthy food and beverage options | • Promotion of citywide employee wellness programs | |

| • Eliminating added trans fat | • Price incentives to encourage consumption of healthier food items | ||

| • Broadening nutrition education and disseminating nutrition education materials | • Gradual sodium reduction plan | ||

| • Creation of stakeholder committee to coordinate efforts to increase participation in the school meal program | • Fountain drink size restrictions |

Standards specific to County of Los Angeles hospital and workplace cafeterias (i.e., does not include standards for distributive meal programs).

Cities include those that participate in the local obesity prevention and health promotion initiatives: Baldwin Park, Bell Gardens, El Monte, Huntington Park, La Puente, Long Beach, Pasadena, Pico Rivera, San Fernando, and South El Monte.

To meet or exceed nutrition standards from the October 2009 Institute Medicine (IOM) report, School Meals: Building Blocks for Healthy Children (34).

Grades K–5 (elementary school).

Grades 6–8 (middle school) and 9–12 (high school).

These standards are for food sold by cafeterias and concession services on government property.

Entrées include those sold in vending machines.

DPH, Los Angeles County Department of Public Health.

Standards vary; present only in some of the targeted/selected cities.

Meals and entrées.

LAUSD set out to meet or exceed school nutrition recommendations from the October 2009 Institute of Medicine (IOM) report, School Meals: Building Blocks for Healthy Children (34). This IOM report called for specific nutrient limits on energy (kilocalories, kcal), sodium, trans fat, percentage of kilocalories from fat, and percentage of kilocalories from saturated fat for meals served in the different grade categories (elementary = K–5, secondary = 6–12): elementary breakfast, elementary lunch, secondary breakfast, and secondary lunch. IOM energy (kilocalories) requirements varied by grade categories: for elementary breakfast, total kilocalories per meal were set at 300–500 kcal; for secondary breakfast, 400–550 kcal; for elementary lunch, 550–650 kcal; and for secondary lunch, 600–700 kcal. Similarly, sodium limits varied from 430 mg to 640 mg, depending on the grade category.

In the County of Los Angeles government, food procurement efforts focused on meeting or exceeding key nutrition and/or purchasing standards established by the DPH for entrées, side dishes, snacks, beverages, and other food products included in meals served at various venues such as workplace and hospital cafeterias, juvenile halls, and probation camps. Future efforts will focus on other institutional food settings such as distributive meal programs and other food-related programs. These efforts were made possible by a motion passed by the County of Los Angeles Board of Supervisors in March 2011, which granted the DPH the authority to review all new and renewing food service and vending contracts to ensure that they adhere to key nutrition standards and food procurement practices (25). Currently, DPH-recommended standards for selected workplace cafeterias include entrées ≤500 kcal, 0 g of trans fat, sodium ≤600 mg, and only 35% and 10% of total kilocalories, respectively, from fat and saturated fat. Limits for side dishes include each side ≤250 kcal, 0 g of trans fat, sodium ≤360 mg, and only 35% and 10% of total kilocalories, respectively, from fat and saturated fat.

In the 10 targeted/selected municipalities, nutrition standards for entrées in vending machines were defined or added through city council resolutions initiated by the municipalities themselves. DPH and other community organizations were asked to provide technical assistance to help develop several of the nutrition standards (when appropriate). Although they represent important progress in these settings, the adopted nutrition standards (in particular, for kilocalories and total fat) were generally less robust and not as broad as those implemented by LAUSD or by the County of Los Angeles.

Snacks in vending machines and concessions.

Nutrition standards for snacks sold or served in vending machines and concessions were also adopted or updated at 2 of the 3 institutional settings: the County of Los Angeles and the 10 municipalities. Nutrition standards for snacks and beverages in vending machines and concessions were already in place for LAUSD and followed local, state, and federal regulations. These LAUSD standards for vending machines and other foods sold outside of the school meals program required that snacks meet the following nutrient limits: 1) not more than 175 kcal per snack at elementary schools, 2) not more than 250 kcal per snack at secondary schools (i.e., middle and high schools), 3) not more than 35% of total kilocalories from fat (not including nuts and seeds); 4) no >10% of total kilocalories from saturated fat, 5) not more than 35% added sugar by weight (not including dried fruits or fruit containing sugar that is part of the dehydration process or added to prevent caking and to maintain flowability of food), 6) not more than 600 mg of sodium per serving, and 7) no trans fat added in the processing.

In the County of Los Angeles, recent updates to the vending policy (35) required that snacks in vending machines be limited to 250 kcal, 360 mg of sodium, 35% of total kilocalories from fat, 10% of total kilocalories from saturated fat, and 35% of total kilocalories from sugar. Similar limits for vending machines and concessions were adopted or updated by the 10 municipalities.

Beverages in vending machines and concessions.

Similar to requirements for meals, entrées, and snacks, nutrition standards for beverages varied across the 3 institutional settings. For example, LAUSD previously had beverage standards that did not specify kilocalorie limits. Beverages sold as à la carte or in District fundraising sales were limited to the following: 1) fruit-based drinks that are composed of not less than 50% fruit juices and have no added sweeteners; 2) drinking water; 3) milk, including but not limited to, chocolate, soy, rice, and other similar dairy or nondairy milk products; and 4) electrolyte replacement beverages and vitamin waters that do not contain >42 g of added sweetener per 20-oz (591-mL) serving. In comparison, recently updated County of Los Angeles vending machine standards outlined which beverages can and cannot be offered (35). The County standards included the following: 1) drinking water (including carbonated water products); 2) fruit-based drinks that are at least 50% fruit juice without added sweeteners; 3) vegetable-based drinks that are at least 50% vegetable juice without added sweeteners; 4) milk products, including 2%, 1%, nonfat, soy, rice, and other similar milk products without added sweeteners; and 5) sugar-sweetened or artifically sweetened beverages that do not exceed 25 kilocalories per 8 oz (237 mL). In the 10 municipalities, beverage standards varied by city and included a combination of adopted or updated requirements that were similar to those of LAUSD and the County of Los Angeles.

Additional requirements.

Aside from the aforementioned nutrition standards, each institutional setting integrated other approaches to healthy food procurement. In the County of Los Angeles, for example, several departments required changes to the cafeteria environment, including energy (kilocalories) postings at point-of-purchase, signage at point-of-selection, product placement guidelines, price incentives to encourage consumption of fruits and vegetables, and fountain drink size restrictions (Table 2).

Lessons learned in Los Angeles County: a local perspective

Although the institutions described in this article varied in their infrastructure, mission, and geo-social landscape (e.g., target populations, institutional structure, clientele, intervention reach; see Table 1), several lessons emerged during the food procurement efforts in Los Angeles County. These lessons included learning about key facilitators of healthy food procurement and troubleshooting key barriers encountered during each phase of the adoption and implementation process (Table 3). Facilitators that contributed to the success of institutional changes included, but were not limited to: understanding the past and/or current institutional food procurement practices and readiness to adopt new approaches; examining institutional authority to adopt nutrition standards and/or other food procurement practices; educating key partners/stakeholders to build support for proposed changes; working with institutional champions; capitalizing on external influences and/or institutional interest to change, building momentum for proposed modifications to the food environment; educating end users (e.g., front-line staff, consumers) through social marketing and other communication channels to help prepare them for forthcoming changes; providing ongoing, high-quality technical assistance to facilitate the adoption and implementation of recommended practices; and conducting ongoing monitoring and evaluation to support program improvement efforts. Barriers that delayed or impeded these processes ranged from complex and time-consuming administrative processes to variable levels of consumer acceptance of the healthier food offerings.

Table 3.

Lessons learned from the adoption and implementation of healthy nutrition standards and other recommended practices in food procurement across three institutional settings in Los Angeles County, 2010–2012

| At the institutional level |

||||

| Facilitators | Phase | Public school district (Los Angeles Unified School District) | County government (County of Los Angeles) | Municipalities (targeted/selected cities in Los Angeles County)1 |

| Understand past and/or current institutional food procurement practices and readiness to adopt new approaches | Needs assessment | Reviewed nutrition standards for school meal program and identified opportunities for improving school meal nutritional content | Conducted a needs assessment to explore the facilitators and barriers to proposed changes in County of Los Angeles food procurement practices | Reviewed existing food and beverage nutrition standards and other procurement practices in Los Angeles County cities Across targeted/selected cities, city staff conducted community needs assessments to inform planning |

| Institutional authority to adopt healthy nutrition standards and/or other recommended practices in food procurement | Needs assessment | The district has the authority to impose stricter nutrition standards while complying with state and federal requirements | County departments have the authority to impose food procurement requirements within food service and vending contracts | Targeted/selected cities have independently passed previous city-level nutrition standards for food services operated by the municipality. |

| Educate key partners and stakeholders to build support for healthy nutrition standards and/or other recommended practices in food procurement | Stakeholder education and strategy development | Worked with a committee comprising parents, community-based organizations (CBOs)2, and school administrators to guide development of menu planning and adoption of standards and other recommended practices in food procurement | Worked with an advisory committee of food service experts to guide development and implementation of healthy nutrition standards and other recommended practices in food procurement Worked with key county department staff who oversee food service contracts to provide context and rationale for changes in food procurement practices | Worked with a food policy task force comprising key stakeholders to guide development of healthy nutrition standards |

| CBOs and city staff held community meetings to seek community input and build support for proposed standards | ||||

| Capitalize on external influences and institutional interest to change | Adoption | Recent changes in the USDA school meal nutrition standards provided an opportunity to promote district-wide changes in menu planning and food procurement practices | Lessons learned from other local, state, federal, and private institutions that have successfully adopted healthy nutrition standards and other procurement practices (e.g., Kaiser Permanente and New York City) informed efforts in the County of Los Angeles | Targeted/selected cities built on the momentum of existing nutrition education campaigns such as “Rethink Your Drink” to establish support for proposed nutrition standards |

| Identify, educate, and provide technical assistance to champions | Adoption | The District’s Board of Education and District administration have led efforts to improve school menu changes CBOs also partnered with the District to build support for healthy menu changes and provided technical assistance to establish more rigorous school meal nutrition standards and other procurement practices | A County of Los Angeles supervisor championed efforts that contributed to the adoption of a Board motion that required inclusion of healthy nutrition standards and other recommended food procurement practices in new and renewing county food service and vending contracts | City officials (e.g., council member, city board) collaborated with various stakeholders (e.g., city management, city health departments) to draft resolutions in support of adopting and/or updating nutrition standards for vending and other concessions across public sites and city facilities |

| Use social marketing, media, and other educational efforts to prepare operational managers and the public for changes | Implementation | The District partnered with a public relations and communication firm to promote and launch the district’s new school menu promotional campaign (i.e., menu event launches, celebrity-sponsored events, press releases, and development and dissemination of promotional materials) | A public relations and communications firm was used to develop public education campaigns (e.g., videos and print materials) on topics such as the importance of reducing sodium consumption to prevent cardiovascular disease | The Los Angeles County DPH2 worked with the CBOs to develop promotional health education videos for educating various stakeholders in the cities/communities |

| Staff capacity and expertise to support the implementation of adopted standards and/or practices | Implementation | The District has a team of registered dietitians and other administrative staff who support efforts to comply with local, state, and federal requirements to receive funding reimbursements for the school meal program | Select county departments have dietitians on staff to assist with menu planning and compliance with nutrition standards | The DPH worked with staff in targeted/selected cities to develop staff training materials to help prepare them for the implementation of nutrition standards |

| The District has a food procurement division that assists with contract development, purchasing and monitoring, and compliance with food contract provisions | County departments have procurement staff to assist with contract development, monitoring, and compliance | |||

| Technical assistance to support ongoing implementation | Implementation | DPH supported CBOs to partner and provide direct technical assistance to the District on menu planning, implementation, and promotion of the new nutrition requirements to staff, students, parents, and the community | DPH staff provided technical assistance to County of Los Angeles departments, including site visits, menu reviews, and technical advice on programmatic monitoring, evaluation (internal), and vendor compliance with food service contracts | CBOs provided direct technical assistance to targeted/selected cities on drafting, adopting, and implementing city-level healthy nutrition standards |

| Monitoring and evaluation for quality improvement purposes | Compliance and quality Improvement | The District regularly conducts a nutritional analysis of school menus to comply with local, state, and federal nutrition requirements. Key indicators such as meal participation rates are regularly reported to the District’s Board of Education | The DPH established a compliance and evaluation plan to document the progress of expanding access to healthy food options for county staff, clients, and other members of the public who may visit county facilities or participate in county-sponsored programs | Targeted/selected cities had staff conduct site visits to all city-owned and -operated vending machines to assess compliance with nutrition standards |

| The DPH and the District partnered to evaluate the new 2011–2012 school menu changes through nutrient analyses, examination of food production records, and plate waste studies | ||||

| Understand past and/or current institutional food procurement practices and readiness to adopt new approaches | Needs Assessment | Awaiting the release of the new USDA school meal guidelines delayed aspects of District menu planning and finalizing of the new 2011–2012 menu. | Institutional nutrition standards and food procurement practices must align with other local, state, and federal guidelines | Information not available |

| Complex institutional administrative processes | Adoption | Changes in administrative leadership and competing institutional priorities affected the implementation of the new 2011–2012 menu | Each county department and food setting has its own internal administrative processes, contracts divisions, and unique needs and concerns | Each city has its own internal administrative processes, contracts divisions, and unique needs and concerns |

| Cost and budget constraints | Adoption and Implementation | District meal production costs and federal meal reimbursement presented challenges to purchasing healthier food items | County departments had concerns about costs, availability, and acceptability of healthier food options | City staff and council had concerns over revenue reduction and other “unintended” consequences of adopting healthy nutrition standards |

| Meal preparation and presentation | Implementation | Inconsistencies in meal preparation, esthetics, and food packaging affected student acceptance of the new school menu | Information not available | Information not available |

| Consumer acceptance of changes in food offerings | Implementation | Initial resistance to the new menu was due in part to student and parent unfamiliarity with the newly presented food products | Information not available | Information not available |

| Gaps in social marketing, media, and dissemination of education materials | Implementation | Although the social marketing campaign to prepare students and parents for the new menu changes was of high quality, competing coverage of higher profile news diluted some of the key messages from the campaign | Limited staff time and resources constrained and delayed the wide distribution of social marketing and education materials | Limited staffing and resources constrained the development and wide distribution of social marketing and education materials |

| Limited institutional and staff capacity | Implementation | Although training was provided to cafeteria managers and front-line staff to assist with the uniform implementation of the new menu, there were gaps in the topics covered | The DPH encountered select staff resistance to healthy nutrition standards and other recommended practices in food procurement due to misperceptions about how diet contributes to obesity | Cities encountered select staff resistance to healthy nutrition standards and other recommended practices in food procurement due to misperceptions about how diet contributes to obesity |

| Monitoring and evaluation for quality improvement purposes | Compliance and quality Improvement | Variable capacity to conduct rigorous evaluation | Variable capacity to conduct rigorous evaluation | Variable capacity to conduct rigorous evaluation |

Cities include those that participate in the local obesity prevention and health promotion initiatives: Baldwin Park, Bell Gardens, El Monte, Huntington Park, La Puente, Long Beach, Pasadena, Pico Rivera, San Fernando, and South El Monte.

CBOs, community-based organizations; DPH, Los Angeles County Department of Public Health.

Conclusions

Adoption and implementation of healthy nutrition standards and other recommended food procurement practices in various food venues that procure, distribute, sell, and/or serve food to employees, students, and the public have the potential to broadly reach diverse communities that are disproportionately affected by obesity and chronic disease risk. These strategies represent promising approaches for improving access to and selection of healthier food options in the community (29). For example, at the school district level, emerging data suggest that improving the quality of foods served in school cafeterias has the potential to increase and sustain healthy eating among a vast number of children because the majority of students eat daily meals prepared and served by schools (20, 36).

In concert with other public health interventions in the community, various sectors (e.g., government, health care, education) are beginning to embrace the use of multisectoral partnerships to address the obesity epidemic and to promote health in the community (16, 18, 20). Collective local efforts in healthy food procurement can cumulatively lead to a shift in the demand for healthier foods, thereby nudging the food supply toward a healthier norm. In addition to providing real world context, lessons learned in Los Angeles County and elsewhere represent important models for how nutrition standards, purchasing, and/or other best practices in food procurement can be effectively applied in diverse institutional settings to increase access to healthier foods.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Lindsey Burbage, Michael Leighs, and Lauren Neel for their technical support and contributions to this article. The authors also thank Alicea Lieberman and Jonathan Blitstein from RTI International for their careful reviews of the manuscript before submission. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used: DPH, Los Angeles County Department of Public Health; IOM, Institute of Medicine; LAUSD, Los Angeles Unified School District.

Literature Cited

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Improving the Food Environment Through Nutrition Standards: A Guide for Government Procurement. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Division for Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention; 2011.

- 2.Gase LN, Kuo T, Dunet DO, Simon PA. Facilitators and barriers to implementing a local policy to reduce sodium consumption in the County of Los Angeles government, California, 2009. Prev Chronic Dis. 2011;8:A33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kimmons J, Jones S, McPeak HH, Bowden B. Developing and Implementing Health and Sustainability Guidelines for Institutional Food Service. Adv Nutr. 2012;3:337–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kozup KC, Creyer EH, Burton S. Making healthful food choices: The influence of health claims and nutrition information on consumers’ evaluations of packaged food products and restaurant menu items. J Mark. 2003;67:19–34 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burton S, Creyer EH. What consumers don’t know can hurt them: Consumer evaluations and disease risk perceptions of restaurant menu items. J Consum Aff. 2004;38:121–45 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glanz K, Hoelscher D. Increasing fruit and vegetable intake by changing environments, policy and pricing: restaurant-based research, strategies, and recommendations. Prev Med. 2004;39:S88–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glanz K, Yaroch AL. Strategies for increasing fruit and vegetable intake in grocery stores and communities: policy, pricing, and environmental change. Prev Med. 2004;39:S75–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seymour JD, Yaroch AL, Serdula M, Blanck HM, Khan LK. Impact of nutrition environmental interventions on point-of-purchase behavior in adults: a review. Prev Med. 2004;39:S108–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bassett MT, Dumanovsky T, Huang C, Silver LD, Young C, Nonas C, Matte TD, Chideya S, Frieden TR. Purchasing behavior and calorie information at fast-food chains in New York City, 2007. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:1457–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joshi A, Azuma A. Do farm-to-school programs make a difference? Findings and future research needs. J Hunger Environ Nutr. 2008;3:2–3 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumanyika SK, Obarzanek E, Stettler N, Bell R, Field AE, Fortmann SP, Franklin BA, Gillman MW, Lewis CE, Poston WC, 2nd, et al. ; American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention, Interdisciplinary Committee for Prevention Population-based prevention of obesity: the need for comprehensive promotion of healthful eating, physical activity, and energy balance: a scientific statement from American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention, Interdisciplinary Committee for Prevention (formerly the expert panel on population and prevention science). Circulation. 2008;118:428–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuo T, Jarosz CJ, Simon P, Fielding JE. Menu labeling as a potential strategy for combating the obesity epidemic: A health impact assessment. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:1680–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Larson N, Story M, Nelson M. Neighborhood environments disparities in access to healthy foods in the U.S. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36:74–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nonas C. Health Bucks in New York City. The Public Health Effects of Food Deserts. Workshop Summary. Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, pp. 59–60, 2009. Available from: http://www.iom.edu/CMS/3788/59640/62040/62078.aspx.

- 15.Gase LN, Kuo T, Dunet D, Schmidt SM, Simon PA, Fielding JE. Estimating the potential health impact and costs of implementing a local policy for food procurement to reduce the consumption of sodium in the County of Los Angeles. Am J Public Health. 2011;101:1501–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Story M, Kaphingst KM, Robinson-O'Brien R, Glanz K. Creating healthy food and eating environments: policy and environmental approaches. Annu Rev Public Health. 2008;29:253–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Booth SL, Sallis JF, Ritenbaugh C, Hill JO, Birch LL, Frank LD, Glanz K, Himmelgreen DA, Mudd M, Popkin BM, Rickard KA, St Jeor S, Hays NP. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2001.tb06983.x. Environmental and societal factors affect food choice and physical activity: rationale, influences, and leverage points. Nutr Rev. 2001;59(3 Pt 2):S21–39; discussion S57–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bunnell R, O’Neil D, Soler R, Payne R, Giles WH, Collins J, Bauer U, Communities Putting Prevention to Work Program Group Fifty communities putting prevention to work: accelerating chronic disease prevention through policy, systems, and environmental change. J Community Health. 2012;37:1081–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.CDC[Internet] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and General Services Administration Health and Sustainability Guidelines for Federal Concessions and Vending Operations [cited 2012 Nov 13]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/pdf/Guidelines_for_Federal_Concessions_and_Vending_Operations.pdf.

- 20.Ashe M, Graff S, Spector C. Changing places: policies to make a healthy choice the easy choice. Public Health. 2011;125:889–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harvie J, Mikkelsen L, Shak L. A new health care prevention agenda: Sustainable food procurement and agricultural policy. J Hunger Environ Nutr. 2009;4:409–29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Los Angeles County Department of Public Health (DPH) [Internet] Strategic Plan 2008–2011. 2008 [cited 2012 Nov 13]. Available from: http://publichealth.lacounty.gov/PLAN/Highlights/Strategic_Plan/Strategic_Plan_2008–2011.htm.

- 23.LA county.gov [Internet] Los Angeles County (LAC) Residents [cited 2012 Nov 13]. Available from: http://www.lacounty.info/wps/portal/lac/residents/

- 24.Los Angeles County Department of Public Health (DPH) Office of Health Assessment and Epidemiology [Internet] Obesity and Related Mortality in Los Angeles County: A Cities and Community Health Report, 2011 [cited 2012 Nov 13]. Available from: http://publichealth.lacounty.gov/ha/reports/habriefs/2007/Obese_Cities/Obesity_2011Fs.pdf.

- 25.County of Los Angeles Board of Supervisors. Healthy Food Promotion in LA County Food Services Contracts. March 22, 2011.

- 26.National Prevention Council. National prevention Strategy. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General; 2011.

- 27.Community Preventive Services Taskforce [Internet] The Guide to Community Preventive Services (The Community Guide) [cited 2012 Nov 13]. Available from: http://www.thecommunityguide.org/index.html.

- 28.Rosenheck R. Fast food consumption and increased caloric intake: a systematic review of a trajectory toward weight gain and obesity risk. Obes Rev. 2008;9:535–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gidding SS, Lichtenstein AH, Faith MS, Karpyn A, Mennella JA, Popkin B, Rowe J, Van Horn L, Whitsel L. Implementing American Heart Association pediatric and adult nutrition guidelines: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Nutrition Committee of the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity and Metabolism, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, Council on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology, Council on Cardiovascular Nursing, Council on Epidemiology and Prevention, and Council for High Blood Pressure Research. Circulation. 2009;119:1161–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cornier MA, Marshall JA, Hill JO, Maahs DM, Eckel RH. Prevention of overweight/obesity as a strategy to optimize cardiovascular health. Circulation. 2011;124:840–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hawkes C. Identifying innovative interventions to promote healthy eating using consumption-oriented food supply chain analysis. J Hunger Environ Nutr. 2009;4:336–56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sharma LL, Teret SP, Brownell KD. The food industry and self-regulation: Standards to promote success and to avoid public health failures. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:240–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weber MD, Simon P, Messex M, Aragon L, Kuo T, Fielding JE. A framework for mobilizing communities to advance local tobacco control policy: the Los Angeles County experience. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:785–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Institute of Medicine of the National Academies [Internet] School Meals: Building Blocks for Healthy Children. 2009 [cited 2012 Nov 13]. Available from: http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2009/School-Meals-Building-Blocks-for-Healthy-Children.aspx. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.County of Los Angeles Board of Supervisors [Internet] Policy #3.155. County of Los Angeles Vending Machine Nutrition Policy. Los Angeles Board of Supervisors Policy Manual [cited 2012 Nov 13]. Available from: http://countypolicy.co.la.ca.us/BOSPolicyFrame.htm.

- 36.Johnston Y, Denniston R, Morgan M, Bordeau M. Rock on Cafe: achieving sustainable systems changes in school lunch programs. Health Promot Pract. 2009;10:100S–8S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]