Abstract

Sugar intake in the United States has increased by >40 fold since the American Revolution. The health concerns that have been raised about the amounts of sugar that are in the current diet, primarily as beverages, are the subject of this review. Just less than 50% of the added sugars (sugar and high-fructose corn syrup) are found in soft drinks and fruit drinks. The intake of soft drinks has increased 5-fold between 1950 and 2000. Most meta-analyses have shown that the risk of obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and metabolic syndrome are related to consumption of beverages sweetened with sugar or high-fructose corn syrup. Calorically sweetened beverage intake has also been related to the risk of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, and, in men, gout. Calorically sweetened beverages contribute to obesity through their caloric load, and the intake of beverages does not produce a corresponding reduction in the intake of other food, suggesting that beverage calories are “add-on” calories. The increase in plasma triglyceride concentrations by sugar-sweetened beverages can be attributed to fructose rather than glucose in sugar. Several randomized trials of sugar-containing soft drinks versus low-calorie or calorie-free beverages show that either sugar, 50% of which is fructose, or fructose alone increases triglycerides, body weight, visceral adipose tissue, muscle fat, and liver fat. Fructose is metabolized primarily in the liver. When it is taken up by the liver, ATP decreases rapidly as the phosphate is transferred to fructose in a form that makes it easy to convert to lipid precursors. Fructose intake enhances lipogenesis and the production of uric acid. By worsening blood lipids, contributing to obesity, diabetes, fatty liver, and gout, fructose in the amounts currently consumed is hazardous to the health of some people.

Introduction

The prevalence of obesity began to increase in the 1980s (1). Currently, nearly 35% of Americans are classified as obese and 65% as overweight (2). This contrasts with a prevalence of 14% in 1972 (1). The increase in obesity reflects a long-term but small excess intake of energy over energy expenditure (3, 4). Data from the USDA show that total calories consumed have increased by ∼425 kcal (1776 kJ) per day above what they were 50 y ago (5). This increase reflects an increase in the intake of most food items, but some have increased more than others. Thus, increased food intake appears to be a key factor in the current epidemic of obesity.

Beverages containing sugars are 1 category of food that has increased significantly in the recent past (6). This review will summarize data on the relationship of beverages sweetened with sugar or high-fructose corn syrup (HFCS) to the risk of the development of obesity, diabetes, heart disease, metabolic syndrome, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and gout. This review also explores the question of whether these effects are the result of the calories provided from sugar (sucrose) or HFCS in these beverages or by the fructose or glucose components that make them up. Finally, several clinical studies of beverage intake are reviewed for the insights that they provide into the biological consequences of excess energy from fructose.

Change in beverage intake

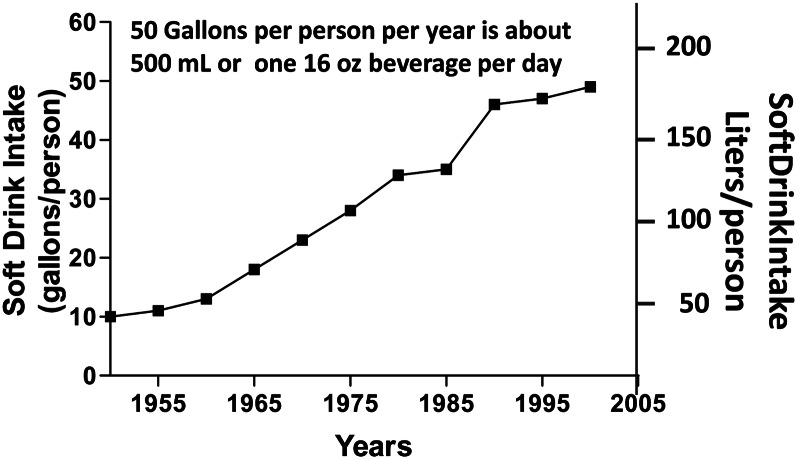

Sugar intake has increased considerably in the past 40 y (6). The soft drinks that were developed more than a century ago now provide a significant source of energy and added sugars. Sugar intake has shown a remarkable increase since the time of the American Revolution, and sugar-sweetened beverages have been an outlet for this sugar in the 20th century. In 1750, the average American consumed 4 pounds (1.81 kg) of sugar per year. This increased to 20 pounds (9.1 kg) per capita by 1850 and showed a further increase to 120 pounds (54.4 kg) per capita by 1994. By the early 21st century, it exceeded 160 pounds (72.6 kg) per capita. The NHANES found that soft drinks and fruit drinks provided >40% of the “sugars” that are added to the diet (7). Between 1950 and 2000, the consumption of soft drinks had increased from 10 gallons (37.9 L) per person per year to just more than 50 gallons (189.3 L) per person per year (8) (Fig. 1). This is equivalent to approximately one 16-oz soft drink per person per day.

Figure 1.

Soft drink intake from 1950 to 2000. Data are expressed in gallons per capita and liters per capita.

Soft drinks increase a number of health risks

Obesity

Interest in the relationship between soft-drink consumption and obesity in children was stimulated by Ludwig et al. (9) who showed that baseline soft-drink consumption predicted future weight gain. In addition, they showed that changes in soft drink intake predicted future weight gain. This early study has been buttressed by many other studies and meta-analyses that were subsequently completed.

Most cross-sectional and longitudinal epidemiological studies in adults have also shown either a positive relationship or no relationship between soft-drink consumption and the risk of obesity; essentially none have found that increased intake of soft drinks were protective against obesity as might be expected if there was a random distribution of body weight in response to drinking sugar-containing beverages. In the meta-analysis of Vartanian et al. (10), the 5 longitudinal studies all reported a positive relationship (10) of beverage intake and obesity with moderate effect size of 0.24. In 4 long-term experimental studies, the effect size was even larger (0.30) and even in 10 of 12 cross-sectional studies, there was a positive relationship with an average modest effect size of 0.13 (10).

In another meta-analysis, Olsen and Heitman (11) found that the majority of 14 prospective and 5 experimental studies found a positive association between the intake of calorically sweetened beverages and obesity. Three experimental studies also found positive effects of calorically sweetened beverages and changes in body fat, but 2 did not find these effects; none showed soft drinks to be protective. In their meta-analysis, 8 prospective studies adjusted for energy intake, and 7 of these found essentially the same associations. On the basis of their meta-analysis, Olsen and Heitman concluded that a high intake of calorically sweetened beverages can be regarded as a determinant for obesity.

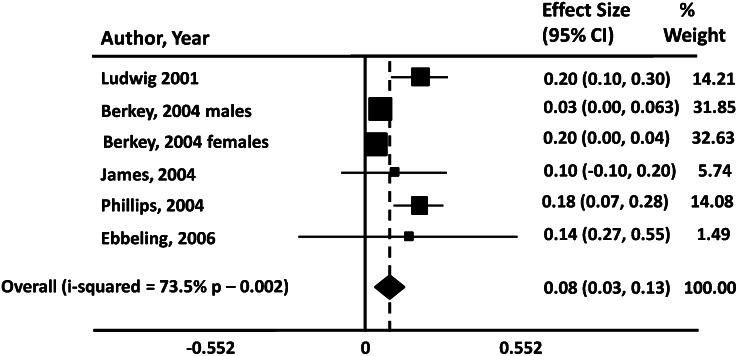

Consuming ≥2 servings per day of beverages sweetened with sugar or HFCS at 5 y of age, but not the consumption of either milk or fruit juice, was positively associated with adiposity from ages 5 to 15 y in 170 non-Hispanic white girls (12). A meta-analysis by Malik et al. (13) re-analyzed previously published data that claimed there was no significant effect of beverages. Malik et al. found instead that there was a significant positive relationship between the intake of soft drinks and obesity in children (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Meta-analysis of studies relating soft drink consumption to the weighted risk of becoming obese in childhood or adolescence. Data not adjusted for energy intake. Reproduced with permission from (13).

Two meta-analyses (14,15) using different inclusion criteria or analytical methods reached different conclusions. One of them examined the effect of replacing carbohydrate in the diet with either isocaloric (n = 13 studies) or hypercaloric (n = 2 studies) amounts of fructose. Sievenpiper et al. (15) found that isocaloric substitution of fructose for carbohydrate had no effect on body weight, as one would expect. They also showed that hypercaloric diets, whether with added fructose or carbohydrate, increased body weight gain, confirming results of other studies (16). This meta-analysis excluded fructose in sucrose and the fructose in HFCS and thus excluded the major sources of fructose in “added sugars.” Fructose added alone to the food supply represents only a few percent of total dietary fructose.

The other meta-analysis by Sun and Empie (14) did not find any relationship between BMI [BMI = body weight (kg)/height (m2)] and consumption of sugar-containing soft drinks. It is not immediately clear why this meta-analysis disagrees with the others. However, there was no evidence that consumption of sugar-containing soft drinks reduced BMI as one might have expected if the relationship of BMI to sugar-containing soft-drink intake was purely random.

Diabetes and cardiometabolic disease

A meta-analysis of 10 prospective cohort studies (6 for type 2 diabetes mellitus, 3 for metabolic syndrome, and 1 for coronary heart disease) evaluating the risk of cardiometabolic disease risk showed a clear and consistent positive association between sugar-sweetened soft-drink intake and weight gain, as well as the risk of diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and metabolic syndrome (17, 18). Among the 294,617 participants in this meta-analysis, the highest level of intake had a 24% greater risk of cardiometabolic disease than those in the lowest group (RR =1.24; 95% CI: 1.12–1.34)).

Other metabolic diseases

The risk of gout is also increased in men by the consumption of fructose from many sources (19). Men who consumed ≥2 sugar-sweetened beverages per day had an 85% greater risk of the development of gout compared with infrequent consumers (RR = 1.85; 95% CI: 1.08–3.16; P < 0.001 for trend). No association was shown with diet soda (19). Dhingra et al. (20) reported a relationship of metabolic syndrome and consumption of both beverages sweetened with sugar or HFCS and beverages sweetened with artificial sweeteners. NAFLD may also be related to metabolic syndrome and consuming sugar-sweetened beverages. In a case-control study of individuals with NAFLD, 31 with metabolic syndrome, 29 without it, and 30 controls, those with the NAFLD and metabolic syndrome consumed just more than 4 soft drinks per day, those with NAFLD and no metabolic syndrome consumed just fewer than 6 soft drinks per day, both of which were significantly higher than in the controls without NAFLD (21).

Beverage consumption and the intake of other foods

Energy obtained from beverages appears to be sensed differently from similar quantities of energy ingested as solid food; that is, the energy in beverages does not produce a corresponding decrease in the intake of energy from solid food, whereas consumption of solid food does produce an off-setting reduction in the intake of other foods. Using a premeal load followed by measurement of food intake at lunch, Rolls et al. (22) reported that the intake of solid food at lunch did not change significantly when there was no preload and, when the preload was water or a cola beverage; that is, the energy in the cola beverage was “add-on” energy without any off-setting reduction in other foods.

To expand on the relationship of beverage intake and compensatory or off-setting reduction in the intake of solid food, Mattes et al. (23) compared 3 different preparations of the same foods in 1 experiment and the comparison of a liquid versus a solid form of food that are predominantly rich in fat, protein, or carbohydrate in another experiment. In each case, the intake of a beverage did not suppress the intake of the other components of a lunch meal or the 24-h food intake by the amount of energy ingested in the beverage. In contrast, the intake of a solid preload of comparable energy value was associated with an appropriate off-setting reduction in the caloric intake of other foods. Thus, the process by which energy ingestion is registered at the pyloric valve or in the intestine to provide information about energy content appears to be suboptimal for suppressing food intake if the energy is in liquid form, but not when it is in solid form (23,24).

Clinical studies evaluating the effects of sucrose, glucose, and fructose on metabolic responses in humans

Several studies have examined the effect of sugar, glucose, or fructose on the metabolic responses of humans. In 1 study using a Latin-Square design, 20 healthy men and women ate a standard meal at 0730 and triglycerides were measured over the next 7 h. Each test meal was separated from the next by at least 72 h. The effect of sucrose, glucose, or fructose on the 7-h increase in triglycerides was measured along with the effects of water and other appropriate controls. Sucrose in a dose of 100 g was compared with 50 g of fructose or 50 g of glucose, which provided the same amount of glucose or fructose that would be provided by the 100 g of sucrose. Triglycerides were increased similarly after sucrose or fructose, and both were significantly higher than glucose, leading the authors to conclude that it was the fructose in sucrose that was responsible for the increase in triglycerides after sucrose (25).

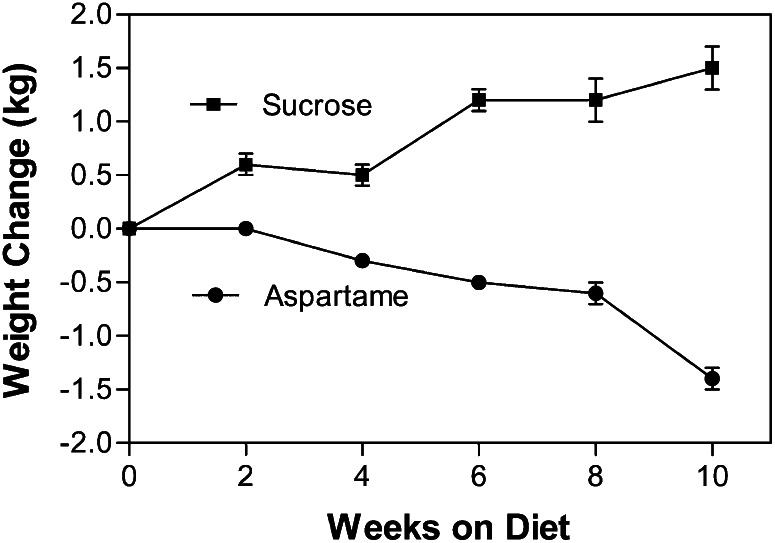

Three randomized clinical trials examined the longer term effect of beverage intake on selected metabolic outcomes. The first trial lasted10 wk and compared 2 groups of young individuals drinking a fixed amount of sugar-sweetened cola versus aspartame-sweetened cola. A total of 41 overweight men and women were entered in this 10-wk parallel-arm study. One group of 21 participants received 3.4 MJ (812.1 kcal) of sugar-containing beverages, and the other 20 received artificially sweetened beverages containing ∼1 MJ (238.8 kcal) and no sugar. Body weight (Fig. 3) and fat mass increased by 1.6 kg and 1.3 kg, respectively, in the group drinking sugar-sweetened beverages and decreased by 1.0 kg and 0.3 kg. Blood pressure increased by 3.8 and 4.1 mm Hg in the sugar-consuming group (26). In addition, concentrations of several inflammatory markers were increased in the group consuming sucrose-containing beverages (haptoglobin by 13%, transferrin by 5%, and C-reactive protein by 6%) compared with a decrease for these same indices in the group consuming aspartame-sweetened beverages (16% decrease for haptoglobin, 2% decrease for transferrin, and 26% for C-reactive protein) (27).

Figure 3.

Body weight during the 10 wk of consuming stable amounts of sugar-sweetened soft drinks or aspartame-sweetened soft drinks. SSB, sugar-sweetened beverages. Reproduced with permission from (26).

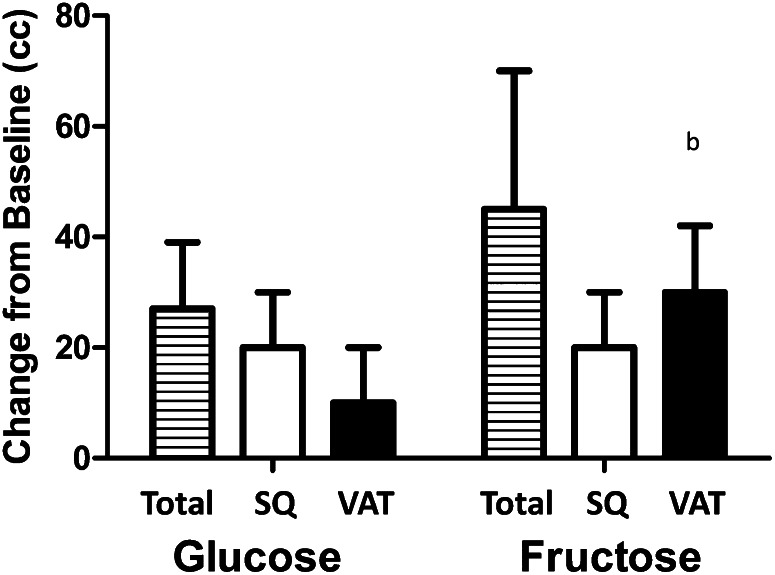

The second study lasted 12 wk with a 2-wk baseline period followed by a 10-wk intervention. A total of 32 overweight men and women (BMI = 29) were randomly assigned to drink 25% of their energy as fructose (n = 15) or glucose (n = 17) for 12 wk (28). The first 2 and last 2 wk were spent in the metabolic ward. The basal diet was 55% carbohydrate, 30% fat, and 15% protein. At 2, 10, and 12 wk, 24-h triglyceride levels rose much more during the nighttime in the individuals drinking the fructose-sweetened beverages than in those given glucose-containing beverages. De novo lipogenesis, measured with stable isotopes, increased significantly during the study in the fructose-sweetened beverage group, but not in the glucose-sweetened beverage group. More ominously, visceral fat, but not subcutaneous fat, in men, increased significantly as measured by computed tomography (Fig. 4) (28).

Figure 4.

Change in total, subcutaneous, and visceral fat during 10 wk of ingesting 25% of calories in beverages composed of either fructose or glucose. SQ, subcutaneous; VAT, visceral fat. Reproduced with permission from (28).

The third study lasted 6 mo. Participants received 1 of 4 treatments: 1 L per day of sugar-sweetened cola (approximately two 16-oz beverages), 1 L per d of milk, 1L per d of aspartame-sweetened cola, or 1 L per day of water. The carbohydrate was 100 g/d from cola (50% fructose) and 47 g/d from milk (no fructose). The results are summarized in Table 1. Body weight and total body fat did not change, but visceral, liver, muscle fat; triglycerides; total cholesterol; and systolic blood pressured showed significant differences with the group drinking the cola beverage being higher than the others. Thus, the consumption of approximately two 16-oz cola beverages per day for 6 mo was sufficient to produce detrimental changes similar to those seen in the metabolic syndrome (29).

Table 1.

Some metabolic responses after 6 months of drinking 1 L of 1 of 4 beverages each day1

| Variable | Cola | Milk | Diet cola | Water | P (overall) |

| % | |||||

| Body weight | 1.3 ± 1.1 | 1.4 ± 1.1 | 0.1 ± 1.1 | 0.6 ± 1.0 | 0.8 |

| Body fat | 3.14 ± 2.7 | 1.42 ± 2.5 | −0.52 ± 2.5 | 0.49 ± 2.6 | 0.8 |

| Subcutaneous fat | 5.0 ± 2.8 | 3.10 ± 2.9 | −2.8 ± 2.7 | −4.3 ± 2.7 | 0.07 |

| Visceral fat | 23.0 ± 90 | −8.0 ± 8.02 | 1.0 ± 8.0 | −0.5 ± 8.0 | 0.03 |

| Liver fat | 130.0 ± 40.0 | −13.0 ± 40.02 | 9.0 ± 35.02 | 2.0 ± 40.02 | 0.01 |

| Muscle fat | 200.0 ± 70.0 | −21.0 ± 60.0 | −27.0 ± 60.0 | 80.0 ± 60.0 | <0.05 |

| Triglycerides | 32.7 ± 8.6 | −0.30 ± 8.12 | −14.1 ± 8.12 | −14.2 ± 7.72 | 0.001 |

| Total cholesterol | 11.4 ± 3.2 | 0.63 ± 3.0 | −5.9 ± 3.02 | −0.16 ± 2.82 | 0.004 |

| Systolic blood pressure | 3.0 ± 3.0 | −7.0 ± 3.02 | −7.0 ± 3.02 | 0 ± 3.0 | 0.01 |

Adapted with permission from (29).

P < 0.05 compared with cola.

Discussion

This review examined some of the relationships between the intake of sugar-sweetened soft drinks and the risk of disease and some of the potential mechanisms for these effects. Many of the epidemiological studies show a positive relationship between the intake of sugar-sweetened beverages and obesity (9–13, 17, 18), and one was neutral (15), but, interestingly, none of them show a protective effect; however, if there were no relationship between intake of sugar-sweetened soft drinks and obesity, one would expect to find an occasional study showing benefit. To the author’s knowledge, none exists. The risk of diabetes, cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, and gout is also increased with the consumption of sugar-sweetened soft drinks (17, 18).

Soft drinks have also been implicated in the risk of the development NAFLD (21). Alcohol and a number of toxins are well-known risk factors for fatty liver and subsequent fibrosis and cirrhosis, but over the past 40 y, a new entity, NAFLD, has come to the fore as a major cause of liver failure and need for liver transplantation (30). NAFLD is the hepatic manifestation of metabolic syndrome, with insulin resistance as the main pathogenic mechanism (31). The increase in intake of sugar-sweetened soft drinks has paralleled this increasing incidence of NAFLD. Although association does not prove causation, dietary fructose has been implicated in the development of NAFLD (32).

Several mechanisms may account for the relationship between the intake of sugar-sweetened soft drinks and the diseases discussed here. First, the sugar in sugar-sweetened beverages provides energy to the body. It is the excess of energy or calorie intake over expenditure that continues over months to years that produces obesity (3, 4, 16). Certainly, the energy content of soft drinks can contribute to this cumulative load of energy.

Second, beverages do not elicit an off-setting degree of energy compensation as do solid foods (22–24). Many kinds of beverages have this effect, and in some studies, beverages may actually stimulate additional intake of energy in solid foods rather than decrease their intake to account for the calories in the beverage (24). In addition, when a single food is prepared in solid, semisolid, and liquid forms, the reduction in intake of solid food is appropriate for the amount of energy ingested with the solid and semisolid forms, but not when the same number of calories from the same fruit are provide as a liquid (23).

Fructose produced when sucrose in the beverages is digested may also provide an important component of the response to sugar-sweetened beverages. When the increase in triglycerides after ingesting 100 g of sucrose was compared with 50 g of either glucose or fructose, the amount of these monosaccharides that are contained in 100 g of sucrose, the increase in triglycerides was similar with sucrose and fructose, and both were higher than with glucose, suggesting that the fructose was responsible for stimulating triglycerides (25), which is entirely consistent with the findings of Stanhope et al. (28) and Teff et al. (33).

Fructose is predominantly metabolized in the liver, which contains abundant glut-5, the transporter protein that facilitates its entry (34, 35). The first step in the metabolism of fructose is its phosphorylation by the transfer of 1 phosphate from ATP to fructose and producing, as a byproduct, ADP, which can be further metabolized to uric acid (35). The phosphorylated fructose is a ready substrate for aldolase, which produces trioses that serve as the backbone of triglycerides. This probably accounts for the increase in de novo lipogenesis seen when fructose-containing beverages are fed acutely (33) or long term (28).

The increase in visceral fat and liver fat in studies in which fructose- or cola-containing beverages are provided for periods of 10 wk (28) to 6 mo (29) shows that the currently formulated sugar-containing soft drinks can mimic many of the features of the metabolic syndrome. In the 6-mo study with two 16-oz cans of cola beverage each day, there was an increase in visceral and muscle fat and systolic blood pressure without a significant change in body weight. This indicates that a dose of 1 L per day of cola beverage for 6 mo, equivalent to two 16-oz cola beverages per day is sufficient to produce the features of metabolic syndrome in some people.

Summary and conclusion

Sugar consumption in the United States has increased >40-fold since 1750. More than 40% of the added sugars are found in soft drinks and fruit drinks. Beverage consumption continues to increase and is now, on average, 500 mL/d or approximately one 16-oz beverage per day; many people consume more than two 500-mL beverages per day. Soft drink intake increases the risk of obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Soft drinks and fructose intake are also related to the risk of the development of gout, metabolic syndrome, and the risk of NAFLD. Beverages sweetened with sugar or HFCS provide energy that is added on. Beverages produce incomplete caloric compensation in contrast to solid foods of the same type. Three randomized studies reached similar conclusions about the metabolic effects of sugar and fructose. Study 1 showed weight gain and increased blood pressure and inflammatory markers after 10 wk of consuming sugar-sweetened beverages. Study 2 showed increased triglycerides, de novo lipogenesis, and visceral fat (in males) with fructose in beverages, but not beverages with the same amount of glucose. Study 3 showed increased triglycerides, total cholesterol, blood pressure, and visceral, liver, and muscle fat after 6 mo of consuming 1 L per day of cola beverage. These may not be messages that the sugar industry or beverage makers want to hear. As John Yudkin (36) expressed it:

I suppose it is natural for the vast and powerful sugar interests to seek to protect themselves, since in the wealthier countries sugar makes a greater contribution to our diets, measured in calories, than does meat or bread or any other single commodity.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Robin Post for her important assistance in preparing this manuscript. The sole author had responsibility for all parts of the manuscript.

Literature Cited

- 1.Ogden CL, Yanovski SZ, Carroll MD, Flegal KM. The epidemiology of obesity. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2087–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Curtin LR. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2008. JAMA. 2010;303:235–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Swinburn B, Sacks G, Ravussin E. Increased food energy supply is more than sufficient to explain the US epidemic of obesity. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90:1453–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bray GA. A guide to obesity and the metabolic syndrome: origins and treatment. New York: CRC Press: Taylor and Francis Group. 2011.

- 5.Putnam J, Allshouse J, Kantor LS. . U.S. per capita food supply trends: more calories, refined carbohydrates and fats. Food Rev. 2002;25:2–15 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duffey KJ, Popkin BM. Shifts in patterns and consumption of beverages between 1965 and 2002. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2007;15:2739–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marriott BP, Olsho L, Hadden L, Connor P. Intake of added sugars and selected nutrients in the United States, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2003–2006. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2010;50:228–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Putnam JJ, Allshouse JE. Food Consumption, Prices, and Expenditures, 1970–1997. USDA Food amp Rural Economic Division, Economic Research Service Bulletin No 965, p. 34.

- 9.Ludwig DS, Peterson KE, Gortmaker SL. Relation between consumption of sugar-sweetened drinks and childhood obesity: a prospective, observational analysis. Lancet. 2001;357:505–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vartanian LR, Schwartz MB, Brownell KD. Effects of soft drink consumption on nutrition and health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:667–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olsen NJ, Heitmann BL. Intake of calorically sweetened beverages and obesity. Obes Rev. 2009;10:68–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCaffery JM, Haley AP, Sweet LH, Phelan S, Raynor HA, Del Parigi A, Cohen R, Wing RR. Differential functional magnetic resonance imaging response to food pictures in successful weight-loss maintainers relative to normal-weight and obese controls. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90:928–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malik VS, Willett WC, Hu FB. Sugar-sweetened beverages and BMI in children and adolescents: reanalyses of a meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89:438–9, author reply 439–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sun SZ, Empie MW. Lack of findings for the association between obesity risk and usual sugar-sweetened beverage consumption in adults–a primary analysis of databases of CSFII-1989–1991, CSFII-1994–1998, NHANES III, and combined NHANES 1999–2002. Food Chem Toxicol. 2007;45:1523–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sievenpiper JL, de Souza RJ, Mirrahimi A, Yu ME, Carleton AJ, Beyene J, Chiavaroli L, Di Buono M, Jenkins AL, Leiter LA, et al. Effect of fructose on body weight in controlled feeding trials: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:291–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bray GA, Smith SR, de Jonge L, Xie H, Rood J, Martin CK, Most M, Brock C, Mancuso S, Redman LM. Effect of dietary protein content on weight gain, energy expenditure, and body composition during overeating: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2012;307:47–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malik VS, Popkin BM, Bray GA, Després J-P, Hu FB. Sugar sweetened beverages, obesity, type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease risk. Circulation. 2010;121:1356–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Malik VS, Bray GA, Popkin BM, Despres JP, Willett FB, Hu WC. Sugar sweetened beverages and risk of metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:2477–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Choi HK, Curhan G. Soft drinks, fructose consumption, and the risk of gout in men: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2008;336:309–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dhingra R, Sullivan L, Jacques PF, Wang TJ, Fox CS, Meigs JB, D'Agostino RB, Gaziano JM, Vasan RS. Soft drink consumption and risk of developing cardiometabolic risk factors and the metabolic syndrome in middle-aged adults in the community. Circulation. 2007;116:480–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nseir W, Nassar F, Assy N. Soft drinks consumption and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:2579–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rolls BJ, Kim S, Fedoroff IC. Effects of drinks sweetened with sucrose or aspartame on hunger, thirst and food intake in men. Physiol Behav. 1990;48:19–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mattes RD, Campbell WW. Effects of food form and timing of ingestion on appetite and energy intake in lean young adults and in young adults with obesity. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109:430–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mourao DM, Bressan J, Campbell WW, Mattes RD. Effects of food form on appetite and energy intake in lean and obese young adults. Int J Obes (Lond). 2007;31:1688–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cohen JC, Schall R. Reassessing the effects of simple carbohydrates on the serum triglyceride responses to fat meals. Am J Clin Nutr. 1988;48:1031–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raben A, Vasilaras TH, Møller AC, Astrup AA. Sucrose compared with artificial sweeteners: different effects on ad libitum food intake and body weight after 10 wk of supplementation in overweight subjects. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;76:721–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sørensen LB, Raben A, Stender S, Astrup A. Effect of sucrose on inflammatory markers in overweight humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82:421–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stanhope KL, Schwarz JM, Keim NL, Griffen SC, Bremer AA, Graham JL, Hatcher B, Cox CL, Dyachenko A, Zhang W, et al. Consuming fructose-sweetened, not glucose-sweetened, beverages increases visceral adiposity and lipids and decreases insulin sensitivity in overweight/obese humans. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1322–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maersk M, Belza A, Stødkilde-Jørgensen H, Ringgaard S, Chabanova E, Thomsen H, Pedersen SB, Astrup A, Richelsen B. Sucrose-sweetened beverages increase fat storage in the liver, muscle, and visceral fat depot: a 6-mo randomized intervention study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;95:283–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clark JM. The epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in adults. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40(Suppl 1):S5–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vanni E, Bugianesi E, Kotronen A, De Minicis S, Yki-Järvinen H, Svegliati-Baroni G. From the metabolic syndrome to NAFLD or vice versa? Dig Liver Dis. 2010;42:320–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lim JS, Mietus-Snyder M, Valente A, Schwarz JM, Lustig RH. The role of fructose in the pathogenesis of NAFLD and the metabolic syndrome. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;7:251–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Teff KL, Grudziak J, Townsend RR, Dunn TN, Grant RW, Adams SH, Keim NL, Cummings BP, Stanhope KL, Havel PJ. Endocrine and metabolic effects of consuming fructose- and glucose-sweetened beverages with meals in obese men and women: influence of insulin resistance on plasma triglyceride responses. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:1562–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Havel PJ. Dietary fructose: implications for dysregulation of energy homeostasis and lipid/carbohydrate metabolism. Nutr Rev. 2005;63:133–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johnson RJ, Perez-Pozo SE, Sautin YY, Manitius J, Sanchez-Lozada LG, Feig DI, Shafiu M, Segal M, Glassock RJ, Shimada M, et al. Hypothesis: could excessive fructose intake and uric acid cause type 2 diabetes? Endocr Rev. 2009;30:96–116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yudkin J. Pure, white and deadly: the problem of sugar. London: Viking; 1986.