Abstract

Background

Parent alcoholism is a well-established risk factor for the development of pathological alcohol involvement in youth, and life stress is considered to be one of the central mechanisms of the parent alcoholism effect; however, little is known about the moderators of the life stress pathway. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) has also been shown to predict pathological alcohol involvement, however, little is known about whether or not ADHD interacts with parent alcoholism to increase offspring risk. The goals of this study were to examine stressful life events as mediators of the relationship between parent alcoholism and adolescent pathological alcohol involvement, and to examine whether or not this mediated pathway was stronger for adolescents with ADHD than for adolescents without ADHD.

Method

Participants were 142 adolescents with a childhood ADHD diagnosis (probands) and 100 demographically matched control adolescents without childhood ADHD. Probands, controls, and at least 1 parent were interviewed about drinking behavior; probands and controls were interviewed about negative life events.

Results

A moderated mediation paradigm was used to test the hypotheses using ordinary least squares regression. Results showed that the relationships between parent alcoholism and 2 of the stress variables (“family” stress and “peer” stress) were significant for probands only, and that stress in the probands mediated the parent alcoholism effect on offspring alcohol involvement.

Conclusions

These results provide preliminary support for the hypothesis that offspring characteristics might moderate the life stress pathway to alcoholism, and indicate that ADHD may serve to facilitate the transmission of pathological alcohol use from parent to child.

Keywords: Parent Alcoholism, ADHD, Stress, Adolescence, Mediation

Parent alcoholism is a well-established risk factor for the development of substance use and substance use problems in youth (Sher, 1991). Developmental models of risk for adolescent substance use have identified multiple mediators and moderators of the parent alcoholism effect that include genetic, biological, and psychosocial influences (Windle and Davies, 1999). Life stress is considered to be one of the central mechanisms by which parent alcoholism exerts its effects (Sher, 1991). Research and theory suggest that parent alcoholism serves as a stressor via short-term and long-term problems that cause instability and unpredictability in the family environment including the disruption of family routines, parenting roles, parent social support, marital functioning, and more (Chassin et al., 1997). Convincing evidence for this putative “ life stress” pathway in children of alcoholics has been offered by landmark studies that explain the intergenerational transmission of pathological alcohol and drug use (e.g., Chassin et al., 1993, 1996). Although these and other studies (Sher et al., 1997) have laid the foundation for a systematic investigation of the life stress pathway, much more research is needed to identify its mediators and moderators.

Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) has also been shown to predict the development of substance use and substance use problems in youth (see Molina and Pelham, 2003). Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder is a persistent and pervasive childhood psychiatric disorder that is comprised of 2 symptom domains, inattention and hyperactivity-impulsivity (see Barkley, 2005). These ADHD symptoms serve as cognitive and behavioral risk factors for a host of long-term deleterious outcomes including social, academic, and interpersonal problems (e.g., Mannuzza et al., 1993). Despite the fact that parent alcoholism and offspring ADHD are well-known risk factors for offspring substance use, very few studies have systematically examined their combined effects. Research on the characteristics of children of alcoholics, and research on the families of children with ADHD suggest that joint study of parent alcoholism and childhood ADHD, in the context of mediated pathways of alcohol transmission might be productive. There is a long history of research showing that parent alcoholism is associated with externalizing symptoms and temperament characteristics not unlike those that characterize children with ADHD (e.g., Cloninger, 1987; Pihl et al., 1990; Windle and Searles, 1990). Moreover, many other studies suggest that ADHD families are often characterized by many of the same risk factors often found among alcoholic families, including poor family functioning, parent–child relationship problems, disrupted family routines, increased family stress, and more (see Johnston and Mash, 2001). The results of these studies inspired the primary goal of this paper, which was to examine the role of off-spring ADHD in the transmission of alcohol problems via the life stress pathway.

In his seminal book on children of alcoholics, Sher (1991) proposed that the pathway to problem drinking that includes negative life events is moderated by offspring characteristics such as temperament and coping skills. For example, Sher proposes that coping skills might buffer the mediating effects of stress on emotional distress and subsequent pathological alcohol involvement. Moreover, children with high-risk temperament characteristics (e.g., significant deviations from the mean on common temperament traits such as activity level and emotionality) might be more vulnerable to the effects of stress or experience exacerbating effects of stress on health outcomes. We propose that childhood ADHD is an ideal variable to test as a moderator in Sher’s paradigm for 2 reasons. First, children with ADHD are by definition characterized by temperament traits (i.e., executive functioning deficits) that impair coping capacity. For example, children with ADHD have significantly less effective coping skills than their non-ADHD peers, and evidence suggests that as a result they use tobacco in adolescence at a higher rate (see Molina et al., 2005). Thus, one hypothesis that follows from Sher’s proposal is that children with ADHD are more vulnerable to stressors that result from parent alcoholism due to poorer coping skills, and as a result, are more likely to drink alcohol in response to these stressors. This hypothesis follows from the classic stress-coping model, such that for youth with adaptive coping skills, the deleterious effects of stress and other substance use risk factors are mitigated, but for children without these skills there is a significant negative impact on health-risk behaviors such as substance use and abuse (see Wills and Filer, 1996).

Second, by definition most children with ADHD have symptoms of hyperactivity and impulsivity, and they are often characterized by poor emotion regulation and higher levels of anger and frustration than are children without ADHD (APA, 1994). A history of research on temperament and psychopathology shows that these symptoms and characteristics are difficult to distinguish from high risk temperament characteristics such as overactivity and emotionality, and some researchers have suggested that psychopathology is an extreme expression of such temperament characteristics (see Frick, 2004). Using a sample of children with ADHD therefore may be an ideal strategy for determining whether or not such traits and symptoms play a role in the transmission of alcohol problems. Although no studies have tested temperament as a moderator of the life stress pathway in children of alcoholics, some evidence suggests that it may moderate the parent alcoholism effect. For example, Wills et al. (2001) found that high risk temperament characteristics exacerbate the relationship between parent substance use and offspring substance use.

The second goal of this paper is to examine the differential associations of specific domains of stressful life events (e.g., family vs academic stress events) with alcohol use. Over the years life events researchers have employed numerous classification methods to describe and organize the many life stress events that cut across life domains such as family, friends, school, work, love, finances, crime, and more (see Sandler and Guenther, 1985); however, with a few exceptions (Grant and Compas, 1995; Wagner and Compas, 1990), researchers have not systematically investigated the role of specific domain effects in adolescence. As a result, very little is known about how parent alcoholism might have a differential impact on, for example, family versus academic stress in offspring. Some researchers suggest that the stressful effects of parent alcoholism are a result of both acute and chronic parent alcohol problems (Chassin et al., 1997; Sher, 1991) and as a result are broad reaching. If so, parent alcoholism might increase stressful life events that may be directly related to parents (i.e., family stress events) and those that are only indirectly related to parents (e.g., academic stress events), yet this remains to be tested. Doing so is important because evidence for specific life stress effects would help researchers and clinicians identify more appropriate targets for prevention and intervention efforts aimed at children who are at risk. In addition, life stressors might have differential effects on adolescent substance use depending on the stress domain and the characteristics of the adolescent. For example, poor academic performance associated with academic stress might be mediated by deviant peer affiliation, such that children with high academic stress are more likely to gravitate toward peer groups where school failure and other deviant behaviors are normative (i.e., substance using peers). This process may be exacerbated by characteristics such as ADHD. For example, some evidence suggests that children with ADHD are more likely than their nondiagnosed peers to affiliate with deviant peer groups, and in turn, use substances at a higher rate (Marshal et al., 2003).

On the other hand, family stress as a result of parent alcoholism might result in poor family functioning. Thus, the relationship between family stress and adolescent substance use might be mediated by different processes, such as parenting problems or deficient parent–child relationships. This mediated effect could also be exacerbated in children with ADHD, due to the higher levels of family stress and conflict in families with children with ADHD (see Johnston and Mash, 2001). Thus children with ADHD might be propelled toward substance use more than children without ADHD because of these family functioning vulnerabilities. For these reasons we believe that ADHD might moderate the relationship between different stress domains and substance use outcomes, but whether the moderation is specific to certain types of events is unclear.

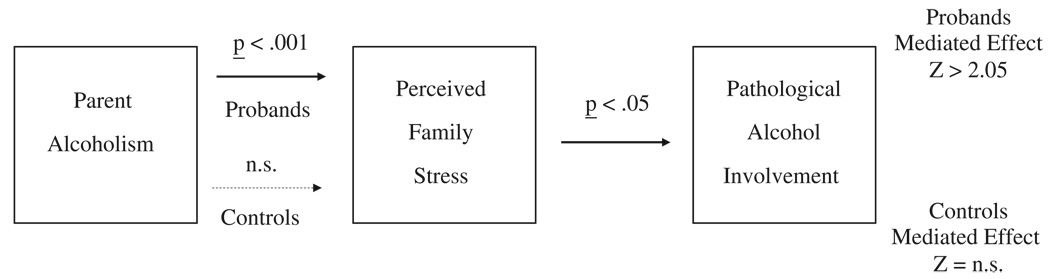

In sum, the goals of this study are to examine stressful life events (family, peer, and academic) as mediators of the relationship between parent alcoholism and adolescent alcohol use and alcohol problems, and to test whether or not ADHD moderates this mediational pathway. To accomplish this goal we will test a moderated-mediation model (see Fig. 1), which will make several contributions to the literature. First, it will attempt to replicate, in part, the findings of Chassin et al. (1993, 1996) and others who have tested a life stress pathway in children of alcoholics originally proposed by Sher (1991). Second, it will expand on these previous papers by examining the mediating role of specific domains of perceived adolescent stressful life events. Third, this study will examine the role of ADHD in the intergenerational transmission of alcohol problems by testing whether or not the stress pathway is stronger for children with ADHD than it is for children without ADHD. By doing so, this study will test the combined role of parent alcoholism and childhood ADHD, 2 central risk factors for the development of offspring alcohol use and alcohol problems. To date, no studies have attempted to examine risk for adolescent alcohol use and alcohol problems using this modeling paradigm. Our hypotheses are that each of the adolescent stressful life event domains will mediate the parent alcoholism effect (paths a and b in Fig. 1), and that ADHD will moderate the effects of parent alcoholism on adolescent stress (interaction d) and the effects of stress on adolescent alcohol use outcomes (interaction e).

Fig. 1.

An illustration of the moderated mediation model predicting adolescent pathological alcohol involvement from parent alcoholism and stressful life events in adolescence.

METHOD

Participants

Participants were 142 adolescents with childhood ADHD (probands) and 100 demographically similar adolescents without childhood ADHD (controls). The mean age for the total sample was 15.2 years (SD = 1.4) and ages ranged from 13 to 18 years old. Eighty-seven percent of the adolescents were Caucasian, 10% were African American, and 3% had other ethnic backgrounds. Ninety-four percent were male. Ninety percent were attending a regular public or private school at the time of the follow-up interview; however, 9% were in alternative school settings (e.g., vocational school) and 2 adolescents were interviewed 6 months after graduating high school. On average, adolescents had completed 9.5 (SD=1.5) years of school. The majority of adolescents lived in 2 parent households (71%). All of the mothers and 96% of the fathers graduated from High School or received their HS equivalency degree. Forty-three percent of the mothers and 46% of the fathers graduated from college. The median family income was $48,000.

Procedure

Childhood

Probands were recruited from those families who applied for services (either the summer program or the outpatient clinic) for their children at the Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic ADD Program (University of Pittsburgh Medical Center) between the years of 1987 and 1995. All probands received a DSM-III-R or DSM-IV diagnosis of ADHD in childhood. At referral, parents and teachers completed a packet of intake measures that included the Disruptive Behavior Disorders Scale (DBD; Pelham et al., 1992), the IOWA/Abbreviated Conners (Goyette et al., 1978; Loney and Milich, 1982), and Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham Scale (SNAP; Atkins et al., 1985), which are norm-referenced, standardized paper and pencil measures of DSM-III-R and DSM-IV ADHD symptom criteria and additional externalizing and social behaviors. These teacher and parent ratings of behavior were used to assess the presence or absence of ADHD symptomatology. In addition, a semistructured diagnostic interview (see Pelham et al., 2002) was conducted with parents by PhD clinicians to confirm presence of DSM-III-R or DSM-IV ADHD symptoms, assess comorbid disorders, and rule out alternative diagnoses. Children were excluded from this follow-up study if their IQ was <80, or if they had a seizure disorder, other neurological problems, or a history of pervasive developmental, psychotic, sexual, or organic mental disorders.

Adolescence

Participants and their parents completed a one-time office-based interview for the follow-up study. Confidentiality of information was supported with a Certificate of Confidentiality from the DHHS with certain exceptions (e.g., suicidality, child abuse), and the study protocol was approved by the University of Pittsburgh IRB. Following collection of written informed consent from the participants and their parents separately, adolescents, mothers, and fathers were interviewed separately. Paper-and-pencil and interview questions were read aloud to adolescents who followed along on their own copy of the measures. Interviewers recorded the answers (substance use was an exception; see details below). At least 3 teachers of primary academic subjects were also asked to complete standardized rating scales for behavior (including ADHD symptomatology) and academic performance.

One hundred demographically similar adolescents without childhood ADHD (controls) were recruited during adolescence from the greater Pittsburgh area using newspaper advertisements (54%), flyers in schools attended by the probands (9%), advertisements in the university hospital voicemail system or newsletter that reaches a large network of hospital staff (26%), or other (e.g., word of mouth, 11%). The control participants were not interviewed in childhood; rather, they were recruited in adolescence using phone screening procedures with the parents and subsequently interviewed in the ADHD program offices. The screening questionnaire was used over the phone with interested parents to ascertain demographic characteristics, history of diagnosis or treatment for ADHD, presence of exclusionary criteria listed above (e.g., low IQ), and to administer a checklist of ADHD symptoms from the DBD (Pelham et al., 1992). Participants were eligible for inclusion in the comparison sample if they did not have a history or current diagnosis of ADHD based on parent and teacher reports on the DBD and by the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC) version 2.3 (Shaffer et al., 1996) completed by their mothers. Control participants were selected to ensure similarity between the proband and non-ADHD groups on age, gender, race, parental education, and single versus 2 parent households. Further details regarding recruitment of the follow-up participants in adolescence may be found elsewhere (Molina and Pelham, 2003).

Adolescent Measures

Pathological Alcohol Involvement

The outcome measure used in this study was offspring pathological alcohol involvement, described by Sher and Gotham (1999) as a “ developmental disorder” in adolescence and young adulthood characterized by “ frequent heavy drinking and alcohol use disorders” (p. 933). As such, our construct was a mean composite of 2 alcohol variables: heavy alcohol use and alcohol use disorder symptoms. Heavy alcohol use was the mean of 2 questions: (1) “ In the past 6 months how many times did you get drunk or ‘very, very high’ on alcohol?” and (2) “ In the past 6 months how many times did you drink 5 or more drinks when you were drinking?” These 2 items were highly correlated (r=0.85, p<0.0001). Adolescent report of alcohol use disorder symptoms (abuse and dependence) were assessed using a highly structured interview version of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID; Spitzer et al., 1987) that we modeled after Martin et al. (1995, 2000) to include DSM-IV substance use disorder criteria and symptoms appropriate for adolescents. Structured Clinical Interviews for DSM-III-R were administered by trained bachelor’s level staff in face-to-face interviews and later scored by senior project staff. Each symptom score ranged from 0 (never experienced the problem) to 2 (experienced the problem to a clinically significant degree). For this study, summed symptom (problem) scores were used as developmentally sensitive indices of emerging alcohol problems in adolescence. The heavy alcohol use and alcohol use disorder symptom variables were correlated at r=0.75 (p<0.0001). To compute the index of pathological alcohol involvement, each variable was standardized and a mean composite was computed of the standardized scores.

Stressful Life Events

Adolescents completed the short form (100 items) of the Adolescent Perceived Events Scale (APES; Compas et al., 1987) and an additional 20 items from the Children of Alcoholics Life Events Schedule (Roosa et al., 1988). Adolescents indicated whether or not they experienced each of the 120 life events in the previous 6 months, and if so, how good or bad the experience was on a 9-point Likert scale ranging from “extremely bad” to “extremely good.” Consistent with the history and standards of research on stressful life events, these ratings were used as proxy indicators of stress experienced by the adolescent (Sandler and Guenther, 1985). For the present study, 3 subscale composites were formed to reflect events in family (40 items), peer (18 items), and academic (15 items) domains. Each composite was formed by summing the total number of events endorsed in each domain that were rated as negative (i.e., “somewhat bad,” “very bad,” or “extremely bad”). Research suggests that this unweighted sum of negative events offers the best prediction of psychopathology and general distress (Sandler and Guenther, 1985) and has been used with adolescent populations (e.g., Compas et al., 1989). Items that asked specifically about life events due to parent alcohol consumption or problems were omitted to reduce contamination between the parent alcoholism predictor and the stress variables. Sample stressful family events include “Arguments or fights between parents,” “Problems or arguments with parents, siblings, or family members,” and “Getting punished by parents.” Sample stressful peer events include “Feeling pressured by friends,” Fight with or problems with a friend,” and “Having few or no friends.” Sample stressful academic events include “Doing poorly on an exam,” “Getting in trouble or being suspended from school,” and “Having bad classes or teachers.”

Parent Measures

Demographics

Parent’s education level and family structure were included as covariates. Parent education was a mean composite of mother’s and father’s continuous education variables coded as: 1 (Less than seventh grade), 2 (Junior high school), 3 (Partial high school), 4 (High school graduate or GED equivalent), 5 (Partial college), 6 (Standard college or university graduation), and 7 [Graduate professional training (graduate degree)]. Family structure was a dichotomous variable indicating whether the child resided with one or both parents.

Alcoholism and Associated Psychopathology

A lifetime history of alcohol problems, as well as depression or dysthymia, in the parents was principally assessed using the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-III-R, Nonpatient Edition (SCID-NP; Spitzer et al., 1990) or DSM-IV (SCID-IV; First et al., 1996). This interview, which has excellent reliability and validity (e.g., see Williams et al., 1992), yielded lifetime diagnoses of alcohol abuse or dependence for mothers and fathers. In the absence of direct interview (49% of fathers and 4% of mothers), alcohol problems were measured with spousal report on the Short Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (SMAST; Selzer et al., 1975). Alcoholism was considered present using the SMAST upon endorsement of 3 or more alcohol-related problems or 1 of 3 diagnostic items indicating receipt of treatment for drinking. This is a widely used measure and set of alcoholism criteria that has been found to be reliable and valid (see Crews and Sher, 1992). Parent’s Antisocial Personality Disorder (ASP) was assessed using the SCID-II ASP Module (SCID-II; Spitzer et al., 1987) administered to parents about themselves and about the other parent. Because only 3 mothers met criteria for ASP, only father’s ASP diagnoses were used in the analyses. Father’s ASP diagnoses were assigned if mother’s report or father’s report of father’s ASP symptoms met criteria.

RESULTS

Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Correlations Among Study Variables

Descriptive statistics for the families of alcoholic and nonalcoholic groups are presented in Table 1, where it can be seen that 32/24 (13%) of mothers and 89/242 (37%) of fathers met criteria for alcoholism in the lifetime. Parent alcoholism was present to a similar degree in the ADHD and non-ADHD families. Among fathers who met diagnostic criteria for an alcohol use disorder (based on the SCID), 49% (n=21/43) met alcohol abuse criteria and 51% (n=23/43) met alcohol dependence criteria. Among these fathers 61% (n=26/43) reported at least weekly drinking, 21% (n=9/43) reported drinking nearly every day, and 51% (n=22/43) reported drinking enough to feel “high or tight” within the past 6 months. Among mothers who met diagnostic criteria for an alcohol use disorder (based on the SCID), 61% (n=19/31) met alcohol abuse criteria and 39% (n=12/31) met alcohol dependence criteria. Among these mothers, 27% (n=8/31) reported at least weekly drinking and 33% of the mothers (n=10/31) reported drinking enough to feel “high or tight” within the past 6 months. These findings suggest that the sample was comprised of a mixture of parents with former and current alcohol problems.

Table 1.

Descriptive Characteristics of Alcoholic and Nonalcoholic Subsamples

| Alcoholic families (n = 104) |

Nonalcoholic families (n = 138) |

Total (n = 242) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Parent characteristics | |||

| Mother’s with 4-y college degree (%) | 32.6 | 50.4 | 42.8 |

| Father’s with 4-y college degree (%) | 36.7 | 52.2 | 46.0 |

| Maternal alcoholism | 30.8% | n/a | 13.2% |

| Paternal alcoholism | 85.6% | n/a | 37.7% |

| Mother’s MDD/DD lifetime diagnosis (%) | 26.0 | 16.7 | 20.7 |

| Father’s antisocial personality diagnosis (%) | 29.8 | 11.6 | 19.4 |

| Mother’s lifetime drug use disordera (%) | 18.3 | 2.2 | 9.1 |

| Father’s lifetime drug use disordera (%) | 14.4 | 3.6 | 8.3 |

| Offspring characteristics | |||

| ADHD diagnosis (%) | 60.6 | 57.2 | 58.7 |

| Mean age at follow-up | 15.2 (1.3) | 15.2 (1.5) | 15.2 (1.4) |

| Mean # of family stress events (SD) | 8.6 (5.7) | 6.8 (5.5) | 7.6 (5.7) |

| Mean # of peer stress events (SD) | 4.5 (3.3) | 3.6 (2.8) | 4.0 (3.0) |

| Mean # of academic stress events (SD) | 3.5 (2.0) | 3.2 (2.2) | 3.3 (2.1) |

| 5+drinks in one sitting past 6 months (%) | 25 | 20 | 22 |

| Drunk at least once in the past 6 months (%) | 33 | 24 | 38 |

| Average number of alcohol disorder symptoms | 2.23 (3.9) | 1.32 (3.3) | 1.71 (3.6) |

One or more of the following drugs assessed by the SCID interview: sedatives, cannabis, stimulants, cocaine, opiates, and hallucinogens.

MDD/DD, Major Depressive Disorder and/or Dysthymia Disorder. ADHD, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder; SCID, Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R.

Correlations among the study variables are presented in Table 2. Note that parent alcoholism was significantly correlated with adolescent pathological alcohol involvement. Correlations among stressful life event composites ranged from 0.35 (between peer and academic stress events) to 0.69 (between peer and family stress events). The putative moderator, ADHD status, was not significantly correlated with parent alcoholism or any of the life stress event measures. Adolescents with childhood ADHD reported slightly fewer negative peer stress events than did controls; however, this association was marginally significant (p<0.10).

Table 2.

Bivariate Correlations Among Study Variables

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Offspring age | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.17** | 0.21** | 0.14* | 0.34*** |

| 2. ADHD status | 1.00 | 0.03 | −0.07 | −0.12 | 0.00 | 0.16* | |

| 3. Parent alcoholism | 1.00 | 0.16* | 0.14* | 0.08 | 0.13* | ||

| 4. Family stress events | 1.00 | 0.69*** | 0.51*** | 0.20** | |||

| 5. Peer stress events | 1.00 | 0.48*** | 0.25*** | ||||

| 6. Academic stress events | 1.00 | 0.26*** | |||||

| 7. Pathological alcohol involvement | 1.00 |

ADHD status and parent alcoholism was coded such that 0=no and 1=yes.

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001.

ADHD, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder.

Mediation Analyses

Three conditions are required for testing mediation. First, there should be a relationship between the independent variable and the dependent variable (path c in Fig. 1) before controlling for the effect of the mediator on the outcome (note that c′—“c-prime”—is conventional notation for this path after controlling for the mediator). Second, there should be a relationship between the independent variable and mediator (path a), and third, there should be a relationship between the mediator and the dependent variable (path b) (Baron and Kenny, 1986; MacKinnon and Dwyer, 1993). These paths are depicted in Fig. 1. Moderated mediation was tested in 2 steps. First, we tested the hypotheses that childhood ADHD moderated paths a and b of the mediator model (see interaction paths d and e in Fig. 1). Second, if these interactions were significant, we tested the significance of the mediated effects for probands and controls separately by estimating the simple slopes of the corresponding paths as suggested by Aiken and West (1991) (for other examples and conceptual discussion of the moderated-mediation paradigm see Baron and Kenny, 1986; Marshal and Molina, 2006; Morgan-Lopez et al., 2003; Tein et al., 2004).

We tested these models using ordinary least squares regression analyses. In all models adolescent age and several parent demographic and psychological variables were included as covariates. Parent covariates that did not affect the results were trimmed from the final models.1 Predictors were centered to facilitate interpretation of the regression coefficients and to reduce nonessential multicollinearity as described by Aiken and West (1991). Diagnostics included examining multicollinearity, nonadditivity (interactions between parent alcoholism and the covariates), and outliers using measures of influence (see Cohen et al., 2004). To test path a and interaction d, 3 models were estimated such that each of the life event composites was regressed on adolescent age, childhood ADHD, parent alcoholism, and the interaction between ADHD and parent alcoholism (see Table 3). Each of the 3 stress domains was tested as a mediator in separate models to reduce problems introduced by multicollinearity.

Table 3.

Regression of Adolescent Life Event Subscales on Adolescent Age, Childhood ADHD, Parent Alcoholism (Path a), and the Interaction Between ADHD and Parent Alcoholism (Interaction d)

| Family stress events |

Peer stress events |

Academic stress events |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | |||

| Adolescent age | 0.17** | 0.21** | 0.16* |

| Childhood ADHD | −0.08 | −0.12* | −0.01 |

| Parent alcoholism (path a) | 0.16** | 0.14* | 0.08 |

| Step 2 | |||

| ADHD×parent alcoholism (interaction d) | 0.22* | 0.16† | 0.12 |

| Effects of parent alcoholism for: | |||

| Probands: | 0.26** | 0.21** | — |

| Controls: | 0.01 | 0.03 | — |

| Total R2 |

Values in the table are standardized regression coefficients. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and parent alcoholism was coded such that 0=no and 1=yes.

p<0.15

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001.

For path a, parent alcoholism was significantly associated with family stress events and peer stress events. Moreover, there was a significant interaction between parent alcoholism and childhood ADHD predicting family stress events (interaction d) and the interaction predicting peer stress events approached significance (p<0.15). Simple slope analysis of these interactions indicated that the relationships between parent alcoholism and family stress events and between parent alcoholism and peer stress events (path a) were strong and significant for probands but not for controls. The relationship between parent alcoholism and academic stress events was not significant, nor was the interaction between parent alcoholism and childhood ADHD predicting academic stress events. As a result academic stress was not tested as a mediator.

Path b and interaction e were estimated by regressing pathological alcohol involvement on all of the predictors that were included in the path a models, and each of the stress domains (in separate models). As shown in Table 4, family and peer stress events were both significantly related to pathological alcohol involvement above and beyond adolescent age, childhood ADHD diagnosis, and parent alcoholism. 2 Childhood ADHD did not moderate path b in the family stress events model or in the peer stress events model, therefore we omitted those interaction terms from Table 4.

Table 4.

Regression of Pathological Alcohol Involvement on Adolescent Age, Childhood ADHD, Parent Alcoholism (Path c), Negative Life Events (Path b), and the Interaction Between ADHD and Each Stress Domain (Interaction e)

| Family stress event model |

Peer stress event model |

Academic stress event model |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Adolescent age | 0.31*** | 0.30*** | 0.30*** |

| Offspring ADHD | 0.17** | 0.18** | 0.15* |

| Parent alcoholism (path c′) | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.09 |

| Stress subscale (path b) | 0.15* | 0.20** | 0.22*** |

| ADHD×stress (interaction e) | — | — | 0.13* |

| Total R2 |

Values in the table are standardized regression coefficients from the final step of the model. Nonsignificant interaction terms were trimmed from the final models. (ADHD) and parent alcoholism was coded such that 0=no and 1=yes.

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001.

Moderated mediation was estimated by calculating the product of the unstandardized regression coefficients for paths a and b (a×b) for each of the stress variables separately for probands and for controls. Approximate Z-scores for each mediated effect were estimated by dividing the product by its standard error [SE(ab)], where SE(ab)2 = SE(a)2 × (b)2 + SE(b)2 × (a)2 (Bollen, 1989; MacKinnon and Dwyer, 1993; Sobel, 1982). These results are presented in Table 5, and support the hypothesis that the mediated pathways through family and peer stress events were relatively strong and significant for probands and weaker and nonsignificant for controls (see example in Fig. 2).

Table 5.

Unstandardized Regression Coefficients Used to Estimate Mediated Effects of Family and Peer Stress Events on Pathological Alcohol Involvement in Probands and Controls

| Path a (SE) | Path b (SE) | Mediated Effect (a×b) |

a×b (SE) |

Z-score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family stress mediator | |||||

| Probands | 2.97 (0.93) | 0.03 (0.01) | 0.07 | 0.04 | 1.97* |

| Controls | 0.13 (1.11) | 0.03 (0.01) | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.12 |

| Peer stress mediator | |||||

| Probands | 1.28 (0.49) | .06 (0.02) | 0.08 | 0.04 | 2.05* |

| Controls | 0.18 (0.59) | .06 (0.02) | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.31 |

p<0.05.

Fig. 2.

Childhood attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder as a moderator of the mediated pathway from parent alcoholism to adolescent pathological alcohol involvement through family stress events.

Moderation of Academic Stress

Although parent alcoholism was not significantly associated with academic stress (precluding tests of mediation for this variable), academic stress was significantly associated with pathological alcohol involvement (Table 4). In addition, childhood ADHD moderated this pathway such that the effects of academic stress were strong and significant for probands (standardized β =0.14, t(241)=4.33, p<0.0001), but not for controls (standardized β=0.02, t(241)=0.39, NS).

DISCUSSION

The results from this study showed that parent alcoholism was associated with adolescent reports of family and peer stress events, and that the mediated pathways from parent alcoholism to offspring pathological alcohol involvement through family and peer stress events were stronger for children with ADHD than for controls. These results contribute to the extant literature in several important ways. First, they replicate earlier findings that life stress mediates the parent alcoholism effect. These studies employed high-risk samples of children of alcoholics (Chassin et al., 1993, 1996) or convenience samples of school children (Roosa et al., 1988, 1990). The current study showed that the role of life stress as a mediator of parent alcoholism also applies to other high-risk groups such as children with ADHD and may be particularly applicable for such vulnerable populations. Replicating this life stress pathway in a sample of children with ADHD is important because it provided an opportunity to test the impact of child psychopathology on this commonly accepted pathway to alcohol use. Our findings suggest that the life stress pathway is particularly salient for children with ADHD suggesting that offspring ADHD may serve as a risk factor by acting as a catalyst for the negative effects of other family stressors such as parent alcoholism. A growing literature suggests that ADHD is a significant risk factor for adolescent substance use in its own right (Claude and Firestone, 1995; Mannuzza et al., 1993), and that it operates through proximal risk factors such as deviant peer affiliation (Marshal and Molina, 2006; Marshal et al., 2003), conduct problems (Claude and Firestone, 1995; Gittelman et al., 1985), and coping skills (Molina et al., 2005). The results from this current study show that ADHD also serves to increase risk indirectly by exacerbating the effects of other familial risk factors such as parent alcoholism. In this way, these results suggest that ADHD may serve to facilitate the transmission of pathological alcohol use from parent to child.

There are several possible explanations for the stronger effects of parent alcoholism on family stress in probands relative to controls. First, a diagnosis of ADHD may capture a subset of children with deficiencies in individual characteristics (e.g., temperament) and skills (e.g., coping ability). These characteristics and skills typically mitigate the negative impact of stressful environmental events such as the negative consequences of parent alcoholism (e.g., family conflict, violence, financial problems). For example, our previous research using this sample shows that controls are more likely to use adaptive coping strategies than are children with ADHD, such as cognitive reframing in stressful situations, and that these coping strategies were associated with less cigarette use in adolescence (Molina et al., 2005). These deficient coping skills might result in higher levels of perceived stress, because offspring may not be readily able to adjust their cognitions about stress events, for example, by recasting negative events related to parent drinking as temporary. Moreover, children with ADHD may be less able to shift their attention to other positive attributes of their parents or positive aspects of the situation when confronted by stressful or negative interactions with their parents.

Second, the relationship between parent drinking and adolescent reports of family stress might be stronger for probands because parent drinking and the problems associated with it might be more salient to offspring with ADHD. For example, 2 laboratory studies showed that confederates who behaved as ADHD children caused much greater levels of distressed affect amongst the adults who interacted with the children compared with those who interacted with the “normal” confederates. Moreover, the adults exposed to the misbehaving confederate children were more likely to drink alcohol (see Pelham and Lang, 1993, 1999), presumably in an attempt to cope with the stress induced by misbehaving children. As a result, parents of children with ADHD may be more likely to drink alcohol to cope with the stresses of raising temperamentally difficult children, which may lead to more alcohol-related consequences for the family. We did not find an association between ADHD and parental alcoholism in the current study, but this may be due to our reliance on lifetime, as opposed to current use of alcohol, and our focus on ADHD children as a group rather than the subgroup of children with ongoing difficulties with externalizing behaviors (unfortunately in the current study we did not have data on the current drinking behaviors for all parents). These more fine-grained analyses will be the subject of future papers in our larger sample of children with childhood ADHD being followed longitudinally (Pittsburgh ADHD Longitudinal Study). However, several prominent studies suggest that there are small and relatively insignificant differences between offspring with parents who are current alcoholics versus offspring of parents whose alcoholism has remitted (Chassin et al., 1991, 1996). This may explain our mediational findings despite the apparent absence of current heavy drinking among some of the problem drinking parents.

Third, several studies have also shown that childhood ADHD is associated with higher levels of parent–child, interparental, and sibling conflict, as well as higher levels of parent-level stress (see Johnston and Mash, 2001; Pelham and Lang, 1993, 1999). Therefore children with ADHD may also be more likely than children without ADHD to experience family conflict, especially when exacerbated by parent alcoholism or the difficulties that accompany it. Finally, alcohol use and alcoholism are associated with high levels of marital and family conflict (e.g., see Marshal, 2003), which might interact with, or exacerbate the already high levels of tension due to disruptive behaviors in the offspring.

There are several possible explanations for why parent alcoholism was associated with peer stress, and why this association is particularly strong and significant for adolescents with childhood ADHD relative to controls. First, experimental (Senchak et al., 1996) and quasi-experimental (Hussong et al., 2005) studies provide some preliminary evidence to suggest that parent alcoholism is associated with deficits in social and interpersonal impairment in children of alcoholics (although there is an overall dearth of strong empirical findings on this topic). It is presumed that social deficits in children of alcoholics are due to exposure to poor family communication and family conflict. In addition, alcoholic parents may be less capable of facilitating their children’s friendships, and less able to help offspring problem-solve and navigate difficult interpersonal situations such as arguments or fights with peers. This problem may be exacerbated in children with ADHD, who are more likely than their peers to experience such strain, making parenting tasks even more challenging. For example, they have been described as “negative social catalysts” in the social arena (Whalen and Henker, 1985), and evidence suggests that children with ADHD have inherent social skill deficits and have difficulty navigating social interactions due to ADHD symptomatology (Hinshaw and Melnick, 1995; Pelham and Bender, 1982). Second, research shows that parent alcoholism (Chassin et al., 1993, 1996) and childhood ADHD (Marshal and Molina, 2006; Marshal et al., 2003) are associated with deviant peer group affiliation which could put them at higher risk for negative interactions and negative experiences with peers, manifesting as peer stress. For example, one of the peer stress items in the measure used in this study asked whether or not respondents felt “pressured” by friends and another asked whether or not friends got drunk or used drugs. Therefore, increased substance use in adolescents who associate with deviant peer groups might be due to multiple factors, and one of the strongest is peer pressure to use drugs and alcohol (Hawkins, Catalano, and Miller, 1992). Moreover, substance using friends are also more likely to engage in other high-risk behaviors and exhibit conduct and oppositional/defiant characteristics, which could incite higher levels of conflict and negative interactions, increasing reported levels of peer-related stress. Finally, some interesting research has shown that children of alcoholics are more likely to report being embarrassed by their parents than children of nonalcoholics (Sher et al., 1997), which may cause strain or awkwardness in peer relationships that may be reflected in peer stress measures.

It is interesting that ADHD status was not significantly correlated with the total number of family, peer, and academic negative stress events, and somewhat paradoxical that adolescents with childhood ADHD reported slightly fewer peer stress events than their nondiagnosed peers. Although there is a dearth of research on the relationship between child psychopathology and stress, a recent review of the literature suggests that the relationship is reciprocal in nature and that they exacerbate each other over time (Grant et al., 2004). For example, Sandler et al. (1994) found support for a “symptom driven hypothesis” such that depression, anxiety, and conduct problems in children of divorce predicted negative life events 6 months later. No studies to date, however, have examined the relationship between ADHD diagnosis and stress events, and there is reason to believe that self-reported stress in children or adolescents with ADHD might be deceptive.

A growing body of research shows that children with ADHD tend to inflate evaluations of their performance, abilities, and likeability, compared with children without ADHD. Hoza et al. (2002) found that ADHD boys overestimated their competence in multiple domains (scholastic, social, and behavioral) compared with teacher ratings of the boys in these same domains. Similar findings have been demonstrated in laboratory tasks with ADHD boys. For example, even though ADHD boys’ objective performance on an academic (“find-a-word”) task was worse than controls, their self-evaluations of their performance were not (Hoza et al., 2001). These studies suggest that a “positive illusory bias” might be operating in children with ADHD, such that they might report fewer stressful life events and that they would be perceived as less negative than would children without ADHD. This potential reporting bias is a measurement challenge across a number of domains of functioning and probably applies not only to children with identified ADHD but to a large number of children with similar or overlapping temperament characteristics. An extension of this bias to the alcohol domain suggests that the ADHD–control group difference in alcohol-related problems of offspring might even be underestimated in this study. Regarding life events, despite the lack of ADHD–control group differences in the number of negative stress events reported, all 3 stress event variables were associated with pathological alcohol involvement. Moreover, in post hoc analyses we found that all 3 stressors were related to heavy alcohol consumption independent of alcoholism symptoms, suggesting that the association was not artificially inflated by the potential overlap between stress items (e.g., peer drinking, fights with parents) and negative alcoholism consequences (e.g., fights with parents over drinking).

It is noteworthy that the relationship between academic stress and pathological alcohol involvement was particularly strong and significant for the probands and not significant for controls. Although this result is a byproduct of the main goals of this study and does not have implications for the intergenerational transmission of alcohol use disorders, per se, it is important because it highlights another means by which ADHD can have a deleterious effect on long-term substance use outcomes, and lends some partial support for the “positive illusory bias” hypothesis. That is, children with ADHD do not perform as well as their nondiagnosed peers on standard achievement tests or on overall measures of academic functioning such as GPA (e.g., Molina, Smith, & Pelham, 2001) and as a result, by definition, they experience more negative academic events (e.g., not doing well on exams, not turning in homework consistently, getting negative feedback from teachers, etc.). However, data in this study show that they have a positive illusory bias or perception that they do not experience more negative academic events, while at the same time reporting a stronger relationship than control participants between negative academic events and pathological alcohol involvement. These variables were measured at the same time point making it impossible to determine the direction of the effect, however this relationship suggests that academic stress and/or failure may be more maladaptive in children with ADHD than controls. Future research that conducts a thorough examination of how children with ADHD perceive and report stressful events, and compares the perception of events with actual events, might lend insight into the study of stress in children with ADHD and to the positive illusory bias.

There are some limitations in the current study. First, caution is warranted when interpreting the mediation effects due to the lack of prospective relationship between measures of stress and pathological alcohol involvement in the adolescents. As a result, we cannot rule out bidirectional effects such that pathological alcohol involvement causes family, peer, and academic stress, nor can we control for potential-biased estimates of the strength of this relationship as a result of possible bidirectional effects. Second, incorporating other putative mediators and moderators of the life stress pathway in children of alcoholics was beyond the scope of this study. For example, according to Sher (1991) a critical component of this pathway is negative affect, which mediates the relationship between perceived stress and alcohol use (e.g., Hussong and Chassin, 1994). Third, a thorough examination of the differential role of recovered versus recent parent alcoholism was beyond the scope of this paper. Previous research has not found that differential effects on offspring alcohol use from recovered versus recent parent alcoholism (e.g., Chassin et al., 1991), but this question should be the focus of future studies that can conduct a thorough examination of these effects in families with child psychopathology and at different stages of development in the child’s life. Finally, there is a small possibility that the higher rates of pathological alcohol involvement in children with ADHD are due to a reporting bias; however most research suggests that children with ADHD are more likely than their non-ADHD peers to underreport behavioral problems and academic problems (see Barkley, 2006) suggesting that the results in this study are most likely conservative. Despite these limitations we believe that these results are a promising first step in identifying pathways of risk for substance use in children with multiple liabilities such as parent alcoholism and childhood ADHD, and suggest that the interaction between parent psychopathology and child psychopathology should not be ignored when estimating risk for adolescent alcohol use and abuse.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant AA015100 from the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Research was also supported in part by AA11873, AA00202, AA08746, AA12342, AA0626, and grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA12414, DA05605, F31DA017546), the National Institute on Mental Health (MH12010, MH4815, MH47390, MH45576, MH50467, MH53554), and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (ES0515-08).

Footnotes

In all regression models parent education, family structure, fathers’ anti-social personality disorder, mothers’ major depressive disorder, and parents’ drug use disorder variables were entered into the equations as covariates in separate models due to their known associations with parent alcoholism and offspring substance use. Because they were not significantly associated with the mediators or the outcomes, and because they did not affect the interpretation of the moderated mediation results, they were trimmed from the final models. Adolescent substance use variables were not normally distributed therefore we also examined the regression models in Mplus (see Muthen and Muthen, 2002) using robust estimators, and in SPSS using square root transformations on the outcome variables. The pattern of effects was not substantially changed using either of these methods. We therefore retained and presented the original (ordinary least squares regression) models.

Post hoc analyses estimating the moderated mediation models using the heavy drinking and alcohol disorder symptoms as separate outcome variables showed that the pattern of effects was not substantially changed, therefore we chose to retain the original model using pathological alcohol involvement as the outcome variable.

REFERENCES

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. Newbury Park: Sage Publications; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Atkins MS, Pelham WE, Licht M. A comparison of objective classroom measures and teacher ratings of attention deficit disorder. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1985;13:155–167. doi: 10.1007/BF00918379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley R. Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A Handbook for Diagnosis and Treatment. 3rd ed. New York: Guilford; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA. Structural Equations with Latent Variables. New York: Wiley; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Barrera M, Jr, Montgomery H. In: Parental alcoholism as a risk factor, in Handbook of Children’s Coping: Linking Theory and Intervention. Wolchik SA, Sandler IN, editors. New York: Plenum Press; 1997. pp. 101–129. [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Curran PJ, Hussong AM, Colder CR. The relation of parental alcoholism to adolescent substance use: an longitudinal follow-up study. J Abnorm Psychol. 1996;105:70–80. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.105.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Pillow DR, Curran PJ, Molina BSG, Barrera M., Jr Relation of parental alcoholism to early adolescent substance use: a test of three mediating mechanisms. J Abnorm Psychol. 1993;102:3–19. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.102.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Rogosch F, Barrera M. Substance use and symptomatology among adolescent children of alcoholics. J Abnorm Psychol. 1991;100:449–463. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.4.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claude D, Firestone P. The development of ADHD boys: a 12-year follow-up. Can J Behav Sci. 1995;27:226–249. [Google Scholar]

- Cloninger RC. Neurogenetic adaptive mechanisms in alcoholism. Science. 1987;236:410–416. doi: 10.1126/science.2882604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West S, Aiken L. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 3rd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Davis GE, Forsythe CJ, Wagner BM. Assessment of major and daily stressful events during adolescence: the adolescent perceived events scale. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1987;55:534–541. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.55.4.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Howell DC, Phares V, Williams RA, Giunta CT. Risk factors for emotional/behavioral problems in young adolescents: a prospective analysis of adolescent and parental stress and symptoms. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1989;57:732–740. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.57.6.732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crews TM, Sher KJ. Using adapted short MASTs for assessing parental alcoholism: reliability and validity. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1992;16:576–584. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1992.tb01420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders—Non-patient Edition (SCID-I/NP, Version 2.0) New York: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ. Integrating research on temperament and childhood psychopathology: its pitfalls and promises. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2004;33:2–7. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3301_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gittelman R, Mannuzza S, Shenker R, Bonagura N. Hyperactive boys almost grown up. I. Psychiatric status. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1985;42:937–947. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1985.01790330017002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyette CH, Conners CK, Ulrich RF. Normative data on revised Conner’s parent and teacher rating scales. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1978;6:221–236. doi: 10.1007/BF00919127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant KE, Compas BE. Stress and anxious-depressed symptoms among adolescents: searching for mechanisms of risk. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1995;63:1015–1021. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.6.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant KE, Compas BE, Thurm AE, McMahon SD, Gipson PY. Stressors and child and adolescent psychopathology: measurement issues and prospective effects. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2004;33:412–425. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3302_23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Miller JY. Risk and protective factors for alcohol and other drug problems in adolescence and early adulthood: Implications for substance abuse prevention. Psychol Bull. 1992;112:64–105. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinshaw SP, Melnick SM. Peer relationships in boys with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder with and without comorbid aggression. Dev Psychopathol. 1995;7:627–647. [Google Scholar]

- Hoza B, Pelham WE, Jr, Dobbs J, Owens JS, Pillow DR. Do boys with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder have positive illusory self-concepts? J Abnorm Psychol. 2002;111:268–278. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.111.2.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoza B, Pelham WE, Waschbusch DA, Kipp H, Owens JS. Academic task persistence of normally achieving ADHD and control boys: performance, self-evaluations, and attributions. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69:271–283. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.2.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussong AM, Chassin L. The stress-negative affect model of adolescent alcohol use: disaggregating negative affect. J Stud Alcohol. 1994;55:707–718. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1994.55.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussong AM, Zucker RA, Wong MM, Fitzgerald HE, Puttler LI. Social competence in children of alcoholic parents over time. Dev Psychol. 2005;41:747–759. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.41.5.747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston C, Mash EJ. Families of children with attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder: review and recommendations for future research. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2001;4:183–207. doi: 10.1023/a:1017592030434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loney J, Milich R. Hyperactivity, inattention, and aggression in clinical practice. In: Wolraich M, Routh DK, editors. Advances in Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. vol. 3. Greenwich, CT: JAI; 1982. pp. 113–147. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Dwyer JH. Estimating mediated effects in prevention studies. Eval Rev. 1993;17:144–158. [Google Scholar]

- Mannuzza S, Klein RG, Bessier A, Malloy P, LaPadula M. Adult outcome of hyperactive boys. Educational achievement, occupational rank, and psychiatric status. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50:565–576. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820190067007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshal MP. For better or for worse? The effects of alcohol use on marital functioning. Clin Psychol Rev. 2003;23:959–997. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshal MP, Molina B, Pelham WE. Deviant peer affiliation as a risk factor for substance use in adolescents with childhood ADHD. Psychol Addictive Behav. 2003;17:293–302. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.17.4.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshal MP, Molina BSG. Antisocial behaviors moderate thedeviant peer pathway to substance use in children with ADHD. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2006;35:216–226. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3502_5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin CS, Kaczynski NA, Maisto SA, Bukstein OG, Moss HB. Patterns of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence symptoms in adolescent drinkers. J Stud Alcohol. 1995;56:672–680. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1995.56.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin CS, Pollock NK, Lynch KG, Bukstein OG. Inter-rater reliability of the SCID substance use disorder section in adolescents. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2000;59:173–176. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00119-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina BSG, Marshal MP, Pelham WE, Wirth RJ. Deficient coping skills and daily smoking among adolescents with and without childhood ADHD. J Pediatr Psychol. 2005;30:345–357. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsi029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina BSG, Pelham WE. Childhood predictors of adolescent substance use in a longitudinal study of children with ADHD. J Abnorm Psychol. 2003;112:497–507. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.112.3.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina B, Smith B, Pelham WE. Factor structure and criterion validity of secondary school teacher ratings of ADHD and ODD. J Abnormal Child Psychol. 2001;29:71–82. doi: 10.1023/a:1005203629968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan-Lopez AA, Castro FG, Chassin L, MacKinnon DP. A mediated moderation model of cigarette use among Mexican American youth. Addictive Behav. 2003;28:583–589. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00262-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen LK, Muthen BO. Mplus User’s Guide. Los Angeles: Authors; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Pelham WE, Bender ME. Peer relationships in hyperactive children: description and treatment. In: Gadow KD, Bialer I, editors. Advances in Learning and Behavioral Disabilities. vol. I. Grenwich, CT: JAI Press; 1982. pp. 365–436. [Google Scholar]

- Pelham WE, Gnagy E, Greenslade KE, Milich R. Teacher ratings of DSM-III-R symptoms for the disruptive behavior disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1992;31:210–218. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199203000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham WE, Hoza B, Pillow DR, Gnagy EM, Kipp HL, Greiner AR, Waschbusch DA, Trane ST, Greenhouse J, Wolfson L, Fitzpatrick E. Effects of methylphenidate and expectancy on children with ADHD: behavior, academic performance, and attributions in a summer treatment program and regular classroom settings. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;70:320–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham WE, Lang AR. Parental alcohol consumption and deviant child behavior: laboratory studies of reciprocal effects. Clin Psychol Rev. 1993;13:763–784. [Google Scholar]

- Pelham WE, Lang AR. Can your children drive you to drink? Stress and parenting in adults interacting with children with ADHD. Alcohol Health Res World. 1999;23:292–298. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pihl RO, Peterson J, Finn P. Inherited predisposition to alcoholism: characteristics of sons of male alcoholics. J Abnorm Psychol. 1990;99:291–301. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.99.3.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roosa MW, Sandler IN, Gehring M, Beals J, Cappo L. Development of a preventive intervention for children in alcoholic families. J Primary Prev. 1988;11:119–141. [Google Scholar]

- Roosa M, Beals J, Sandler IN, Pillow DP. The role of risk and protective factors in predicting symptomatology in adolescent self-identified children of alcoholic parents. Am J Community Psychol. 1990;18:725–741. doi: 10.1007/BF00931239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandler IN, Guenther RT. Assessment of life stress events. In: Karoly P, editor. Measurement Strategies in Health Psychology. New York: Wiley; 1985. pp. 555–600. [Google Scholar]

- Sandler IN, Tien J, West SG. Coping, stress, and the psychological symptoms of children of divorce: A cross-sectional and longitudinal study. Child Dev. 1994;65:1744–1763. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00846.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selzer ML, Vinokur A, van Rooijen L. A self-administered Short Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (SMAST) J Stud Alcohol. 1975;36:117–126. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1975.36.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senchak M, Greene BW, Carroll A, Leonard KE. Global, behavioral and self ratings of interpersonal skills among adult children of alcoholic, divorced and control parents. J Stud Alcohol. 1996;57:638–645. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1996.57.638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Fisher P, Dulcan MK, Davies M, Piacentini J, Schwab-Stone ME, Lahey BB, Bourdon K, Jensen PS, Bird HR, Canino G, Regier DA. The NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version 2.3 (DISC-2.3): description, acceptability, prevalence rates,and performance in the MECA study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;5:865–877. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199607000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ. Children of Alcoholics: A Critical Appraisal of Theory and Research. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Gershuny BS, Peterson L, Raskin G. The role of childhood stressors in the intergenerational transmission of alcohol use disorders. J Stud Alcohol. 1997;58:414–427. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Gotham HJ. Pathological alcohol involvement: a developmental disorder of young adulthood. Dev Psychopathol. 1999;11:933–956. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499002394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel ME. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation. Social Methodol. 1982;13:290–312. [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer R, Williams J, Gibbon B. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Personality Disorders (SCID-II) New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer R, Williams J, Gibbon B, First MB. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R-Non-Patient Edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Tein JY, Sandler IN, MacKinnon DP, Wolchik SA. How did it work? Who did it work for? Mediation in the context of a moderated prevention effect for children of divorce. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72:617–624. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.4.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner BM, Compas BE. Gender, instrumentality, and expressivity: moderators of the relation between stress and psychological symptoms during adolescence. Am J Community Psychol. 1990;18:383–406. doi: 10.1007/BF00938114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whalen CK, Henker B. The social worlds of hyperactive (ADDH) children. Clin Psychol Rev. 1985;5:447–478. [Google Scholar]

- Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB, Spitzer RL, Davies M, Borus J, Jowes MJ, Kane J, Pope HG, Jr, Rounsaville BJ, Wittchen HU. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID) II: multi-site test-retest reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:630–636. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820080038006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Filer M. Stress-coping model of adolescent substance use. In: Ollendick TH, Prinz RJ, editors. Advances in Clinical Child Psychology. vol. 18. New York: Plenum Press; 1996. pp. 91–132. [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Sandy JM, Yaeger A, Shinar O. Family risk factors and adolescent substance use: moderation effects for temperament dimensions. Dev Psychol. 2001;37:283–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windle M, Davies PT. Developmental theory and research. In: Leonard KE, Blane HT, editors. Psychological Theories of Drinking and Alcoholism. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford; 1999. pp. 164–202. [Google Scholar]

- Windle M, Searles JS. Children of Alcoholics: Critical Perspectives. New York: Guilford; 1990. [Google Scholar]