Abstract

Appendicectomy is one of the commonest emergency operations performed worldwide. In cases of perforated appendicitis, the prevalence of post-operative abscess formation is up to 20 per cent (1). Most cases can be managed with drainage and antibiotics. However, a minority of these will leave a retained appendicolith.

We present a case of a 17 year old female patient who presented 1 year after laparoscopic appendicectomy for perforated appendicitis, with right upper quadrant pain and sepsis.

Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen was performed and revealed a retained appendicolith with perihepatic abscess formation in the right upper quadrant. She underwent laparoscopic drainage of this perihepatic abscess and removal of the faecolith. She was discharged home the following day and remains well.

INTRODUCTION

Appendicoliths are the proposed aetiology of acute appendicitis in the majority of cases. It is postulated that these cause luminal obstruction resulting in subsequent acute inflammation of the mucosa. Appendicoliths are composed of inspissated faecal material, mucus with trapped calcium phosphate and inorganic salts.

Dropped appendicoliths from appendicectomy are rare, but the surgeon and radiologist ought to consider them as a potential source of intra-abdominal complications.

Until recently, the presence of an appendicolith was considered 100% specific for the diagnosis of acute appendicitis. However, 13% of patients without acute appendicitis showed an appendicolith on CT (2). Approximately 60% of resected appendices contain appendicoliths (1). Presence of an appendicolith is also associated with a high incidence of perforation, particularly in children.

Appendicoliths can be detected by plain abdominal radiographs in 10 to 15% of patients with acute appendicitis. With the recent popularity of ultrasound and computed tomography, the rate of detection has increased (3).

The appendicoliths can drop at the time of resection of the appendix, during forceful extraction through the umbilical port or if the appendix perforates. Complications associated with retained faecoliths following appendicectomy are becoming more prevalent with the increased use of the laparoscopic technique, similar to the increase in dropped gallstones following the introduction of laparoscopic cholecystectomy (2). The time between laparoscopic appendicectomy and representation with abscess ranged from 2 months to 4 years (2).

The natural history of dropped appendicoliths is not yet known but there is some early evidence that they have a significant association with abscess formation, with the appendicolith acting as a nidus for infection. CT-guided percutaneous drainage of intra-abdominal abscess secondary to retained appendicoliths is only successful in the short term. Formal surgical drainage and removal of the appendicolith is required for long-term success (2). Ultrasound has been described as a useful adjunct for intra-operative localisation of the appendicolith (4).

CASE REPORT

A 17-year-old female presented to the emergency department, with intermittent right upper quadrant pain, nausea and vomiting. She had been feeling unwell over the preceding 2 weeks. She was previously fit and well, with her only background history being a laparoscopic appendicectomy for perforated appendicitis the previous year, aged 16.

On examination she was obviously uncomfortable, but haemodynamically stable. She had a mild pyrexia of 37.5°C. Abdominal examination revealed tenderness to palpation in the right upper quadrant and no palpable masses. Bloods tests revealed raised inflammatory markers.

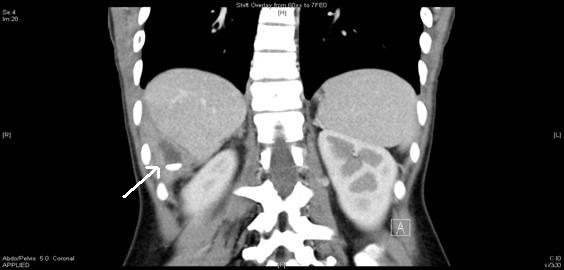

Computed tomography of the abdomen was performed and revealed a 4×3cm structure of low attenuation posterolateral to segment 6 of the liver with surrounding irregular wall and a central 15 mm high density lesion, suggestive of a peritoneal foreign body, possibly a retained appendicolith from previous surgery (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Abdominal CT scan showing a radio-opaque faecolith in the right upper quadrant (arrowed)

It was felt that this could be removed via ultrasound guidance through a small intercostal incision under local anaesthetic. This was attempted but failed secondary to an iatrogenic pneumothorax and failure to localise the lesion. She was referred to the authors for consideration of laparoscopic management.

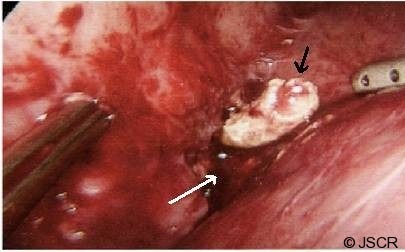

She underwent diagnostic laparoscopy which revealed an abscess cavity in the image identified location. Once the peritoneum was opened purulent fluid discharged and on exploration of the cavity the faecolith was found (Figure 2). The faecolith was removed and abscess drained. A 20 Robinson drain was placed in the cavity until the following morning. The patient’s post-operative course was uneventful and she was discharged home the following day in a stable condition, afebrile and with normal serum inflammatory markers.

Figure 2.

Appendicolith (black arrow) in the perihepatic abscess cavity (white arrow).

DISCUSSION

Appendicectomy, especially in cases of perforated appendicitis, is associated with postoperative abscess formation in up to 20 per cent of cases (1). Most can be treated with percutaneous drainage and antibiotics. Though this treats the abscess, it does not necessarily treat the root cause and nidus of infection – the appendicolith. In cases of retained appendicolith, clearly the definitive management is removal of the appendicolith. Failure to do so may result in recurrent intra-abdominal abscesses, wound infection and occasionally fistula formation (5).

Retained appendicolith has been reported in different sites including the pelvis, gluteal region, hepatorenal pouch (of Morrison) and subhepatic region. It can be detected by ultrasound or computed tomography scan as fluid collection containing a focus of high attenuation which may be single or multiple. Occasionally, plain radiograph film may show these retained appendicolith, though the sensitivity is only 10% (1).

The literature reveals few cases of subhepatic abscesses due to retained appendicolith and most of them required operative intervention, whether laparoscopic or via the open approach. One case of percutaneous appendicolith removal through an existing fistulous tract has been reported.

Appendicectomy is associated with a risk of retained appendicolith. A high index of suspicion ought to be maintained in patients presenting with recurrent intra-abdominal sepsis and a history of appendicectomy. The risk of retained appendicolith may be reduced by ensuring that the distal end is intact after division of the appendix. The authors advise gentle manipulation when handling an acutely inflamed appendix to avoid appendicolith spillage. In the event of spillage, the appendicolith ought to be retrieved, as failure to do so may lead to subsequent complications.

Definitive treatment depends on removal of appendicolith, and the authors advocate that this can be safely accomplished via the laparoscopic method.

REFERENCES

- 1.Buckley O, Geoghegan T, Ridgeway P, et al. The usefulness of CT guided drainage of abscesses caused by retained appendicoliths. Eur J Radiol 2006; 60:80–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Newrhee K, William PR, Maher A, Douglas SK. CT identification of abscesses after dropped appendicoliths during laparoscopic appendectomy. AJR 2004; 182:1203–1205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strathern DW, Jones BT. Retained fecalith after laparoscopic appendectomy. Surg Endosc 1999; 12:287–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee SW, Lim JS, Hyung WJ, et al. Laparoscopic ultrasonography for localization of a retained appendicolith after appendectomy. J Ultrasound Med 2006; 25:1361–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rasuli P, Friedlich MS, Mahoney JE. Percutaneous retrieval of a retained appendicolith. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2007; 30:342–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]