Abstract

The term ‘regional interdependence’ or RI has recently been introduced into the vernacular of physical therapy and rehabilitation literature as a clinical model of musculoskeletal assessment and intervention. The underlying premise of this model is that seemingly unrelated impairments in remote anatomical regions of the body may contribute to and be associated with a patient’s primary report of symptoms. The clinical implication of this premise is that interventions directed at one region of the body will often have effects at remote and seeming unrelated areas. The formalized concept of RI is relatively new and was originally derived in an inductive manner from a variety of earlier publications and clinical observations. However, recent literature has provided additional support to the concept. The primary purpose of this article will be to further refine the operational definition for the concept of RI, examine supporting literature, discuss possible clinically relevant mechanisms, and conclude with a discussion of the implications of these findings on clinical practice and research.

Keywords: Physical therapy, Regional interdependence, Rehabilitation

Introduction

‘Regional interdependence’ or ‘RI’ is the term that has been utilized to describe the clinical observations related to the relationship purported to exist between regions of the body, specifically with respect to the management of musculoskeletal disorders.1 There is a growing body of literature demonstrating that interventions applied to one anatomical region can influence the outcome and function of other regions of the body that may be seemingly unrelated.2–7 Despite the growing interest, controversy exists regarding the relevance of the RI model in physical therapy research and practice.8 Therefore, RI warrants further examination and scientific scrutiny.

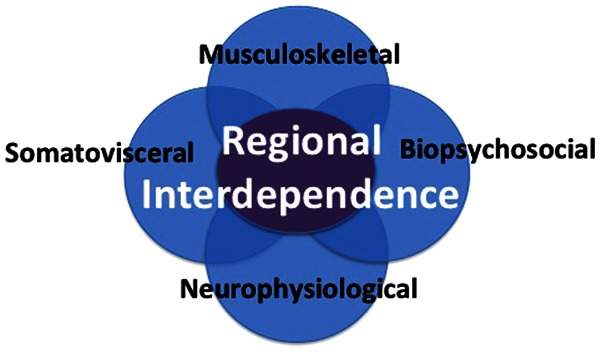

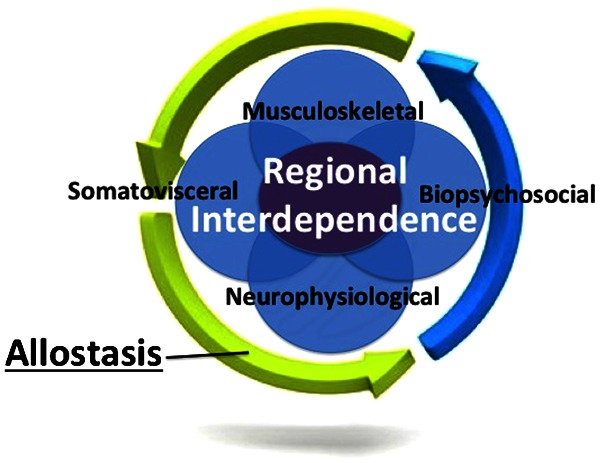

RI was initially defined and proposed as a part of a basic manipulation skills educational CD-ROM developed by Wainner et al. in 2001.9 The concept of RI stemmed from the review of literature during which they observed that regions of the body appeared to be musculoskeletally linked.10–12 Erhard and Bowling alluded to this concept in 1977 when they stated: ‘Dysfunction in any unit of the system will cause delivery of abnormal stresses to other segments of the system with the development of a subsequent dysfunction here as well’.13 Although Erhard’s observation preceded Wainner’s, RI was not proposed as a formal concept and did not gain wider recognition as a model of assessment and treatment in the peer-reviewed literature until Wainner et al. described it in an editorial in 2007.1 At that time, it was proposed primarily as a clinical model to be considered and incorporated in the context of a ‘test-treat-retest’ approach14 to treating patients with musculoskeletal disorders. Commentary in response to the original RI editorial countered the suggestion that RI was the result of musculoskeletal factors and suggested that RI may also involve a neurophysiological response.8 The points made by Bialosky et al. in the response brought to light the fact that while the primary interest of RI has been physical manifestations (typically pain and range-of-motion) involving the musculoskeletal system, the mechanisms underlying these primary manifestations can be much more complex involving other physiological systems.15 Any condition or disorder initiates a series of responses that involves multiple systems of the body. Not only musculoskeletal but also neurophysiological, somatovisceral, and biopsychosocial responses occur when a disorder or condition disrupts homeostasis16,17 (Fig. 1). These allostatic responses are all pieces of an integrated physiological process that functions to restore equilibrium and promote recovery18,19 (Fig. 2). The RI model as defined represents the musculoskeletal manifestation of a larger interdependent process by which other systems may be involved in eliciting these musculoskeletal changes.

Figure 1.

Regional interdependence involves the coordinated and integrated action of multiple systems including musculoskeletal, biopsychosocial, neurophysiological, and somatovisceral.

Figure 2.

The allostatic process is responsible for the regulation and integration of biopsychosocial, neurophysiological, somatovisceral, and musculoskeletal responses.

The biomedical model of disease has served as the foundation for assessment and treatment in the clinical management of patients and it is taught in first-professional physical therapists programs as a primary model for managing patients with musculoskeletal disorders. In this model, clinical management decisions are predicated on the identification of a pathoanatomical source tissue. However, interventions and treatment plans focused upon a single pathological structure can often result in poor outcomes, in particular with spinal disorders for which a pathoanatomic source tissue cannot be identified in the majority of cases.20,21 In addition, clinical decision making based on a single pathological finding has been credited as contributing to these poor results.22 Therefore, in orthopedic clinical settings, the biomedical model should be expanded to include identification of other factors or regions that may contribute to the patient’s complaints. The RI model of assessment and treatment provides a framework to incorporate this expanded focus.

The purpose of this article is to propose a revised operational definition for the concept of Regional Interdependence based on current best evidence and supporting literature. In addition, this article will explore the literature underlying the concept of RI, as well as the implications of the RI model for clinical practice and research.

RI Defined and Redefined

RI was originally defined as a concept that seemingly unrelated impairments in remote anatomical regions could contribute to and be associated with a patient’s primary complaint.1 The definition was limited in that it considered the musculoskeletal system as the primary source as well as manifestation of impairments and did not consider other systems as sources or factors that could contribute to the impairments. Therefore, the current definition may be incomplete or misleading and requires further refinement. A more comprehensive definition of RI would be ‘the concept that a patient’s primary musculoskeletal symptom(s) may be directly or indirectly related or influenced by impairments from various body regions and systems regardless of proximity to the primary symptom(s)’. In this definition, impairments are not limited to the musculoskeletal system and include those that may originate from other systems, which may contribute to or influence the patient’s primary musculoskeletal complaint(s). Validating this definition, therefore, requires researchers to demonstrate that impairments in one region of the body or one system of the body can have a direct or indirect influence upon the musculoskeletal symptoms and function of another region of the body.7,8,23–29

Origins of RI

RI is a musculoskeletal model born out of earlier clinical reports and clinical observation. In other words, clinicians treating one region of the body, such as the hip, noticed that signs and symptoms in areas remote to the area of treatment, such as the knee, were altered. From this insight followed the observation that impairments located in one region of the body could also be affected or were associated with the musculoskeletal function and symptoms of a completely separate region.

The concept that the function and health of one region of the body could potentially affect the function of another region is not novel. In 1944, Inman and Saunders30 stated that both clinical and experimental evidence indicated that pain could be experienced over a considerable distance from the site of the local lesion and in 1959, Slocum31 stated that it was not uncommon for a baseball pitcher with an injured toe or foot to lose the effectiveness of the shoulder joint.

From these published beginnings, backed by clinical observation and established clinical practice patterns, additional works under experimental conditions began to appear that supported the clinical interdependent relationship between regions of the body. Cleland et al.,3 Fernandez-de-las-Penas et al.,32 and Gonzalez-Iglesias et al.33 have all demonstrated that interventions focused on the thoracic spine could affect impairments in the cervical region. Similarly, Currier et al.4 and Souza and Powers6 have both provided evidence that treatment of the hip could alleviate impairments located at the knee. Since it was editorialized in 2007, multiple studies have been published that directly reference the concept of RI (Table 1).

Table 1. Studies with direct mention of regional interdependence.

| Authors | Title and journal | Regions | Design | Number of subjects | Level of evidence* |

| Systematic reviews and meta analyses | |||||

| Walser RF, Meserve BB, Boucher TR51 | The effectiveness of thoracic spine manipulation for the management of musculoskeletal conditions: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J Man Manip Ther 2009 | Thoracic spine and various musculoskeletal conditions | Systematic review of cohort RCTs | N/A | Level 2a |

| Randomized control trials and experimental studies | |||||

| Bunn EA, Grindstaff TL, Hart JM, Hertel J, Ingersoll CD103 | Effects of paraspinal fatigue on lower extremity motoneuron excitability in individuals with a history of low back pain. J Electrophysiol Kinesiol 2011 | Lumbar spine and lower extremity | Cohort | 20 | Level 2b |

| de Oliveira Grassi D, Zanelli de Souza M, Belissa Ferrareto S, Imaculada de Lima Montebelo M, Caldeira de Oliveira Guirro E104 | Immediate and lasting improvements in weight distribution seen in baropodometry following a high-velocity, low-amplitude thrust manipulation of the sacroiliac joint. Man Ther 2011 | Sacroiliac joint and lower extremity | Prospective cohort | 20 | Level 2b |

| Iverson CA, Sutlive TG, Crowell MS, Morrell RL, Perkins MW, Garber MB, Moore JH, Wainner RS105 | Lumbopelvic manipulation for the treatment of patients with patellofemoral pain syndrome: development of a clinical prediction rule. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2008 | Lumbar spine and knee | Cohort CPR | 50 | Level 2b |

| Mintken PE, Cleland JA, Carpenter KJ, Bieniek ML, Keirns M, Whitman JM5 | Some factors predict successful short-term outcomes in individuals with shoulder pain receiving cervicothoracic manipulation: a single-arm trial. Phys Ther 2010 | Cervicothoracic spine and shoulder | Cohort CPR | 80 | Level 2b |

| Strunce JB, Walker MJ, Boyles RE, Young BA7 | The immediate effects of thoracic spine and rib manipulation on subjects with primary complaints of shoulder pain. J Man Manip Ther 2009 | Thoracic spine and shoulder | Cohort | 21 | Level 2b |

| Case studies | |||||

| Burns SA, Mintken PE, Austin GP106 | Clinical decision making in a patient with secondary hip-spine syndrome. Physiother Theory Pract 2011 | Hip and lumbar spine | Case study | 1 | Level 4 |

| Lowry CD, Cleland JA, Dyke K107 | Management of patients with patellofemoral pain syndrome using a multimodal approach: A case series. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2008 | Knee and multiple regions | Case series | 5 | Level 4 |

| Vaughn DW108 | Isolated knee pain: a case report highlighting regional interdependence. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2008 | Knee and pelvis | Case study | 1 | Level 4 |

| Welsh C, Hanney WJ, Podschun L, Kolber MJ109 | Rehabilitation of a female dancer with patellofemoral pain syndrome: applying concepts of regional interdependence in practice. N Am J Sports Phys Ther 2010 | Knee and multiple regions | Case study | 1 | Level 4 |

| Clinical commentaries | |||||

| Lucado A, Kolber M, Echternach J, Cheng MS53 | Subacromial impingement syndrome and lateral epicondylalgia in tennis players. Phys Ther Rev 2010 | Shoulder and elbow | |||

| Isabel de-la-Llave-Rincon, A., Puentedura EJ., Fernandez-de-las-Penas C110 | Clinical presentation and manual therapy for upper quadrant musculoskeletal conditions. J Man Manip Ther 2011 | Upper quadrant | |||

| Reiman MP, Weisbach PC, Glynn PE111 | The hips influence on low back pain: a distal link to a proximal problem. J Sport Rehabil 2009 | Hip and lumbar spine | |||

| Sueki DG, Chaconas EJ26 | The effects of thoracic manipulation of shoulder function: a regional interdependence model. Phys Ther Rev 2011 | Thoracic spine and shoulder | |||

| Editorials | |||||

| Wainner RS, Whitman JM, Cleland JA, Flynn TW1 | Regional interdependence: a musculoskeletal examination model whose time has come. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2007 | Not applicable | |||

| Bialosky JE, Bishop MD, George SZ8 | Regional interdependence: a musculoskeletal examination model whose time has come. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2008 | Not applicable | |||

Note: RCT: randomized control trial; CPR: clinical prediction rule.

*Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine Levels of Evidence Criteria: 2a, systematic review of cohort studies; 2b, individual cohort study; 3a, systematic review of case control studies; 3b, individual case control study; 4, case series.

Evidence for RI

An electronic search was conducted using PubMed, Medline, Google Scholar, and the Cochrane Library. The pool of articles was initially screened for studies that included the words ‘regional interdependence’ and were also relevant to musculoskeletal and orthopedic physical therapy. Because the term ‘regional interdependence’ is relatively new, the literature with direct reference to its usage is somewhat limited. Using the described search method, 16 articles were found that specifically utilize or describe the term ‘regional interdependence’ and are listed in Table 1. An even larger number of studies exist in the literature that supports the concept of RI but do not directly reference the model (Table 2). A similar search method was utilized to identify these articles. Keywords utilized for the search consisted of the regions of interest (i.e. lumbar spine and knee). The results were then screened for articles relevant to the topic. The reference list of the relevant articles was then examined to determine whether additional articles existed that were not identified in the previous search. The most relevant publications from the search will be described in the following sections.

Table 2. Evidence of regional interdependence.

| Quarter | Regions | Study | Type of study | Number of subjects | Level of evidence* |

| Lower quarter | Hip and lumbar | Arab AM, Nourbakhsh MR (2010)37 | Cross-sectional cohort | 300 | Level 2b |

| Arab AM, Nourbakhsh MR (2010);37 Arab et al. (2011)40 | Cohort | 20 | Level 2b | ||

| Ben-Galim P et al. (2007)35 | Prospective cohort | 25 | Level 2b | ||

| Di Lorenzo L et al. (2007)36 | Prospective cohort | 37 | Level 2b | ||

| Ellison JB et al. (1990)112 | Case–control | 150 | Level 3b | ||

| Kendall KD et al. (2010)113 | Quasi-experiment cohort | 20 | Level 2b | ||

| Mellin G (1988)39 | Case–control | 476 | Level 3b | ||

| Nadler SF et al. (2000)114 | Cohort | 210 | Level 2b | ||

| Nelson-Wong et al. (2009)115 | Prospective cohort | 43 | Level 2b | ||

| Paquet N et al. (1994)116 | Case–control | 20 | Level 3b | ||

| Stupar M et al. (2010)34 | Population-based cohort | 983 | Level 2b | ||

| van Dillen LR et al. (2008)117 | Case–control | 48 | Level 3b | ||

| Yoshimoto H et al. (2005)118 | Retrospective case–control | 150 | Level 3b | ||

| Deyle GD et al. (2005)119 | Prospecitve cohort | 134 | Level 2b | ||

| Knee and lumbar | Deyle GD et al. (2000)120 | RCT of cohort | 83 | Level 2b | |

| Stupar M et al. (2010)34 | Population-based cohort | 983 | Level 2b | ||

| Suri P et al. (2010)121 | Case–ontrol | 1389 | Level 3b | ||

| Foot/ankle and lumbar | Bjonness T (1975)122 | Case–control | 93 | Level 3b | |

| Brantingham JW et al. (2006)43 | Case–control | 100 | Level 3b | ||

| Kosashvili Y et al. (2008)42 | Retrospective case–control | 97 279 | Level 3b | ||

| Hip and knee | Astephen JL et al. (2008)90 | Cross-sectional case–control | 181 | Level 3b | |

| Bennell KL et al. (2007)123 | RCT of cohort | 88 | Level 2b | ||

| Bolgla LA et al. (2011);45 Bolgla LA et al. (2008)124 | Cross-sectional case–control | 18 | Level 3b | ||

| Currier LL et al. (2007)4 | Cohort CPR | 60 | Level 2b | ||

| Finnoff JY et al. (2011)46 | Prospective cohort | 98 | Level 2b | ||

| Rowe J et al. (2007)47 | Case–control | 19 | Level 3b | ||

| Souza RB et al. (2009)6 | Cross-sectional case–control | 41 | Level 3b | ||

| Ankle and knee | Astephen JL et al. (2008)90 | Cross-sectional case–control | 181 | Level 3b | |

| Molgaard C et al. (2011)48 | Case–control | 299 | Level 3b | ||

| Upper quarter | Thoracic and cervical spine | Cleland JA et al. (2005)3 | Cohort RCT | 36 | Level 2b |

| Cleland JA et al. (2010)102 | Cohort CPR | 140 | |||

| Fernandez-de-las-Penas C et al. (2009)32 | Cohort | 45 | Level 2b | ||

| Gonzalez-Iglesias J et al. (2009)33 | Cohort RCT | 45 | Level 2b | ||

| Thoracic spine and shoulder | Boyles RE et al. (2010)2 | Cohort | 56 | Level 2b | |

| Mintkin PE et al. (2010)5 | Cohort CPR | 80 | Level 2b | ||

| Thoracic spine and upper extremity | Strunce JB et al. (2009)7 | Cohort | 21 | Level 2b | |

| Berglund et al. (2008)50 | Cohort | 62 | Level 2b | ||

| Cervical spine and upper extremity | Berglund et al. (2008)50 | Cohort | 62 | Level 2b | |

| Suter E et al. (2002)52 | Cohort | 16 | Level 2b | ||

| Vicenzino B et al. (1996)125 | Cohort RCT | 15 | Level 2b | ||

| Shoulder and elbow | No known experimental studies | ||||

| Elbow and hand | No known experimental studies | ||||

| Upper and lower quarter | Lower extremity and shoulder | Klein MG et al. (2000)55 | Cohort | 194 | Level 2b |

Note: RCT: randomized control trial; CPR: clinical prediction rule.

*Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine Levels of Evidence Criteria: 2a, systematic review of cohort studies; 2b, individual cohort study; 3a, systematic review of case control studies; 3b, individual case control study; 4, case series.

Clinical Studies

Lower quarter

The majority of lower extremity literature supporting the concept and model of RI is related to the lumbopelvic region (Tables 1 and 2). Low back pain has been positively associated with hip osteoarthritis, fractures, and following total hip replacement surgery.34–36 Stupar et al. has also demonstrated a positive relationship between low back pain and the presence of knee osteoarthritis.34 Additionally, decreased strength, neuromuscular control, range of motion, and mobility of the lower quarter have all demonstrated a positive association with the presence of low back pain and impairments.37–40 A relationship between the foot and ankle and the lumbosacral region has been proposed in publications by Cibulka11 and Rothbart and Estabrook.41 Kosashvili et al.42 demonstrated that a positive correlation exists between a pes planus position in the foot and low back pain. Similarly, Brantingham et al.43 established a potential positive relationship between ankle impairment and lumbar pain.

While the preponderance of literature has focused on the lumbopelvic region, there have also been a recent number of publications related to the knee. Powers44 has suggested that proximal factors such as hip impairment may play a contributory role in knee injuries. Bogla et al.,45 Finnoff et al.,46 Souza et al.,6 and Rowe et al.47 have all demonstrated that deficits in hip strength and abnormal hip mechanics are positively correlated with knee pain (Table 2). Although it is common clinical practice to assess and treat the foot and ankle in patients with other lower quarter impairments, very few studies aside from those mentioned previously have looked specifically at the influence that the ankle or foot can have on outcomes related to the hip, pelvis, or lumbar spine. Molgaard et al.48 studied high school students with patellofemoral pain (PFPS) found greater navicular drop, navicular drift, and dorsiflexion in the subjects with PFPS compared with healthy students (Table 2).

Upper quarter

Like the lower quarter, there is also evidence of RI relationships in the upper quarter. (Table 2). Studies by Cleland et al.3 and Gonzales-Iglesias et al.33 linking cervical pain to thoracic interventions have been mentioned previously. Additionally, Strunce et al.,7 Boyles et al.,2 and Mintken5 have demonstrated that interventions focused on the thoracic spine have the potential to alter shoulder symptoms. Yoo et al.49 demonstrated that sympathetic blocks at the thoracic spine could improve upper extremity neuropathic pain and Berglund et al.50 showed that pain and dysfunction of the thoracic spine is positively correlated with the presence of lateral elbow pain. For a more in depth discussion, the reader is directed to a systematic review by Walser et al.51 that discusses the effect of thoracic manipulation on various musculoskeletal conditions.

While not as prevalent, numerous studies have also linked impairments in the cervical spine and upper quarter. Berglund et al.50 surveyed subjects with lateral elbow pain and found 70% of subjects also reported pain in the cervical and thoracic regions compared to 16% in the asymptomatic control group. Vicenzino et al.25 has linked cervical manipulation with decreases in pressure pain threshold and increases in grip strength in subjects with lateral elbow pain. Suter et al.52 demonstrated an increase in bicep muscle strength and a decrease in muscle inhibition following cervical manipulation. Clinically, and in published reviews,53,54 it has been hypothesized that the function of the shoulder can directly influence impairments at the elbow and hand, but to date, no studies have validated this hypothesis. Like the lower quarter studies, much of the research was not designed specifically to study the RI model, yet the results of the studies suggest that RI may be a viable concept and model.

Upper and lower quarter

While the vast majority of available research has focused on establishing a relationship between adjacent regions of the upper or lower quarter, the RI model suggests that a patient’s primary musculoskeletal symptoms may be influenced by impairments regardless of proximity to the patient’s primary symptoms. There is a small amount of evidence that is beginning to suggest that these relationships extend beyond adjacent regions of the body to more remote sites (Table 2). As mentioned previously, Kosashvili et al.42 and Brantingham et al.43 both established a potential positive relationship between ankle and foot impairment and lumbar pain. In the upper quarter, Berglund et al.50 established a potential relationship between the thoracic spine and elbow impairments.

These studies emphasize relationships between upper or lower quarter regions. However, theoretically impairments in the the lower quarter could influence the function of the upper quarter and similarly, dysfunction in the upper quarter could have an impact upon the function of the lower quarter. Klein et al.55 screened polio survivors and the results of the study suggest that lower extremity weakness may predisposed subjects to shoulder overuse symptoms and has the potential to negatively influence the function of the shoulder. While it is only one study in a specific sample pool and does not establish a direct linkage between the upper and lower quarter, the results do seem to support the concept that regions of the body are interrelated and may influence symptoms irrespective of their proximity. Considerably, more research is needed in order to determine if clinically meaningful relationships exist beyond adjacent regions and extend to the upper and lower quarters.

Proposed Mechanisms

The RI model has its roots in clinical practice and has been utilized primarily to support clinical decision-making. Even before recent clinical research appearing to support the model, clinicians and researchers have speculated about physiological and biomechanical mechanisms underlying these long-standing clinical observations. In 1955, Steindler56 proposed a model based on a kinetic mechanical engineering model. He termed this relationship the ‘Kinetic Chain’ and in his model, he described the body as a series of interconnected joints where the movement of one joint directly effects the movement of other joints above and below. His model is based primarily upon the biomechanical relationship between regions of the body. For example, decreased dorsiflexion in the talocrural joint can produce biomechanical compensatory changes in knee, hip, and lumbar spine. The recent literature demonstrating interdependent relationships between the thoracic spine/cervical spine and the hip/knee are examples of this potential biomechanical link or kinetic chain.3,4,44

Bialosky et al. have suggested that RI may be the result of neurophysiological mechanisms or the combined interaction between biomechanical and neurophysiological mechanisms.15 This observation has its basis in recent work related to temporal summation and pain perception related to manual therapy interventions.24,57,58 The result of this work combined with prior research has led to the suggestion that neurophysiological mechanisms play a major role in the physiological effects experienced by patients.58 Like the biomechanical proposition mentioned previously, more research is needed before any definitive conclusions or statements can be made.

While the mechanisms previously discussed provide feasible explanations for the RI model, neither have been definitively established or well investigated. It is unlikely that a single mechanism or body system explanation is sufficient, thus a more comprehensive model is needed. The revised definition of RI acknowledges that biomechanical and neurophysiological factors may account for musculoskeletal responses seen in conjunction with treating impairments, but it expands upon the previous definition and includes the provision that various body regions and systems may contribute to these observed musculoskeletal responses and their associated clinical outcomes and likely also include other factors (Fig. 1). From a clinical management perspective, the redefined RI model is more comprehensive then the original definition and allows for the consideration and subsequent management of numerous factors including other body regions and systems that may be contributing to a patient’s musculoskeletal symptoms.

The redefined concept of RI proposes that:

Response(s) to a disorder or condition and the associated clinical outcome(s) are not limited to local and adjacent regions of the body but can involve a neuromusculoskeletal response that may be more widespread.

Multiple systems respond to impairment and may influence the function of the neuromusculoskeletal system and associated symptoms.

Response to any disorder or condition is not limited to local and adjacent regions of the body but can involve a neuromusculoskeletal response that may be more widespread

The musculoskeletal interdependence between regions of the body does not exist in isolation. Changes in the musculoskeletal system must also be accompanied by changes in neurophysiology because these and other systems work in concert to perform tasks. Interventional-based studies have demonstrated that treatments targeting one area of the body can affect neuromuscular performance in remote regions of the body. It has been demonstrated that manual therapy and spinal manipulation can alter local and distal motoneuron excitability. Of particular interest to the RI model are the effects of spinal manipulation on distal neuromuscular function. Suter et al.59,60 has demonstrated that thrust manipulation of the sacroiliac joint decreased motor inhibition of the knee extensor muscles, while Dishman et al.61 showed that lumbar spinal manipulation increased electromyographic (EMG) activity remotely in the gastrocnemius muscle. Additionally, Murphy et al.62 and Dishman et al.61,63 showed that manipulation of the lumbosacral region has the potential to produce a decrease in distal neuromuscular function as measure by the magnitude of the tibial nerve H-reflex. These studies may be reflective of an interventional effect on nerve and muscular function beyond the immediate and adjacent regions of the body. While the evidence supporting a neurophysiological relationship between lumbosacral manipulation and remote lower extremity neurophysiological responses exists, a recent follow-up study by Suter et al.59 has suggested that manipulation may not have a significant effect on distal motoneuron excitability (H-reflex testing). It is unclear whether these studies refute the previous studies, are indicative of the variability normally seen when utilizing H-reflex as an outcome measure, or whether magnitude and direction of response are preferentially influenced. In either case, a potential relationship exists between interventions targeting one region of the body and the neuromuscular performance in regions remote to the area of intervention that warrants further exploration.

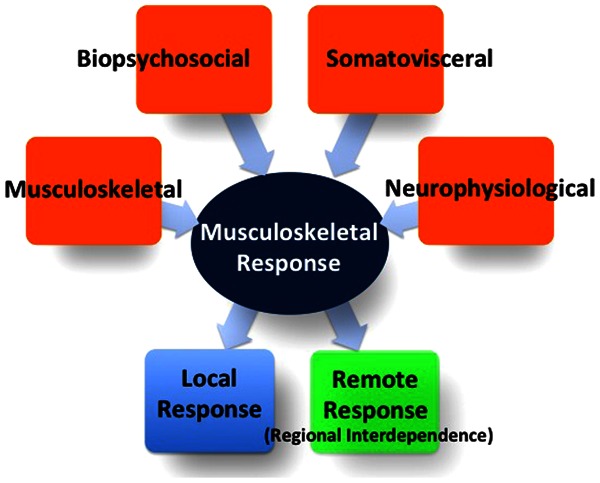

Multiple systems respond to impairment and may influence the function of the musculoskeletal system

A previously noted, the body appears to utilize physiological mechanisms in an integrated fashion in order to adapt or reduce the loads or stress placed upon involved structures. There is an interdependence that exists between regions of the body, as well as, other systems. In the initial model of RI, it was inferred that the adapting structures were musculoskeletal in nature. In the revised model of RI, it is proposed that not only neurophysiological8 and musculoskeletal1 structures but biopsychosocial64 and somatovisceral65 systems can all potentially affect the function of the musculoskeletal system (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Multiple systems can contribute to a musculoskeletal response by the body. Both local and remote responses occur, but the Regional Interdependence Model represents remote responses by the body.

Biopsychosocial Considerations

The biopsychosocial model proposes that the experience of pain and resultant responses stem from the interaction of biological, psychological, and social factors.66,67 The recognition of an association between physiology and psychology is not new and dates as far back as 350 BC. Both Aristotle19 and Abu Zayd Al-Balkhi68 suggested that health was tied to the interweaving of the psyche and its biological manifestations and a large body of current literature supports such a relationship.27,67,69–73

Bialosky et al.,74 George et al.,27,75 and Fritz et al.76 have all demonstrated that factors such as fear avoidance, pain catastrophizing, and anticipation can impact musculoskeletal function and pain. Moseley77,78 and Butler and Page79 have demonstrated that altering a patient’s perception of pain allows for improved neuromuscular function. Similarly, Moseley28 and van Oosterwijck et al.80 have demonstrated that educating patients about pain mechanisms may subsequently alter neuromuscular function and pain. Bialosky et al.57 has demonstrated that a subject’s expectations can affect the pain perceptions following an intervention. In addition, a clinician’s attitude towards a patient’s treatment and recovery has the potential to impact the prognosis of a patient both negatively and positively.74,81

Depression,82 post-traumatic stress,83,84 fear avoidance,75,76,85 anxiety,86 pain catastrophizing,87 and negative emotions88 have all been demonstrated to exert influence upon musculoskeletal pain. An in-depth discussion regarding specific psychological impairments observed in patients with musculoskeletal disorders and their underlying physiological mechanisms are beyond the scope of this paper. However, given the strong influence of biopsychosocial factors and potential to be positively influenced, it is important for clinicians to understand and consider the interdependent relationship between biopsychosocial, neurophysiological, and musculoskeletal factors when assessing and treating patients.

Referred, Somatovisceral, and Radicular Pain: Special Considerations

Referred and radicular pain and their relationship with RI have some unique considerations. By definition, referred pain is pain that is perceived in a location other than the actual site of painful stimulus or source of symptoms (tissue symptom generator).89 For example, primary hip disorders can refer pain into the lower extremity,4,44 but it can also exhibit impairments that affect symptoms and musculoskeletal responses without the referral of pain, as in the case with patients with knee osteoarthritis.90 Both of these examples would fall within the definition of RI. In this instance, referred pain is a special case with the hip disorder being the source of symptoms. However, hip impairments may not necessarily refer pain, but may be associated and influence remote symptoms in other regions of the body.

It is well supported in literature that somatovisceral tissue can be a source of referred pain as well as mimic musculoskeletal pain.65,91 For example, left shoulder pain can be due to heart disorders, right shoulder pain can be the result of liver disorders, and low back pain can be the product of urogenital disorders.92 It is not known whether somatovisceral structures may be a source of disability and limitations in musculoskeletal function, but literature suggests that such a relationship may exist.93 In a longitudinal study of women’s health, Smith et al.29,94 found that in women, menstrual cramping, incontinence, gastrointestinal symptoms, and respiratory problems were all associated with the development of low back pain. This is not to suggest a causal relationship, but simply that somatovisceral structures have the potential to contribute to musculoskeletal symptoms and should be screened as potential contributors to these symptoms. Clinically, the consideration of somatovisceral structures as a source of symptoms, in particular with regard to Red Flag findings, is a routine and recommended component of a physical therapist’s practice95 and if suspected, referral to appropriate health care practitioner is warranted.

Acute radicular pain can be defined as pain that originates from the spinal nerve roots and is experienced remotely from the site of the nerve root lesion.96 As was the case with referred pain, radicular pain also represents a special case of RI (musculoskeletal symptoms experienced remotely to the affected region), which is a modification of the original description by Wainner et al.1 With radicular pain, the nerve root is the source of symptoms, but it may also result in other local and remote impairments that contribute to the source of symptoms. These related impairments may contribute to that patient’s source of symptoms within the RI model, but would be distinct from true acute nerve root pain. Examples of such impairments would be abnormal motor responses97 and limited nerve root mobility.97,98

Clinical Implications

The RI model does not suggest that the biomedical model should be abandoned, but instead modified to include additional considerations and concepts. Assessment and management strategies should seek to identify pathoanatomical tissues that may be the source of the patient’s symptoms. Unfortunately, a single underlying pathoanatomical cause that is responsible for a patient’s primary and secondary complaints often cannot be identified in patients with musculoskeletal disorders, particularly those with spine problems.99 Therefore, while clinicians should initially seek to identify a specific pathoanatomic source of the patient’s symptoms, in particular red-flag conditions, they should also consider impairments of other systems or regions that may be directly or indirectly associated with the patient’s complaints. There is some research to suggest that such an expanded approach can produce positive results. Trials utilizing a multi-modal treatment approach supported by RI concepts have demonstrated efficacy.3,100–102 The RI model should be viewed as an integrative model that eliminates the dichotomy of having to choose between a biomedical, neurophysiological, or biopsychosocial model. It uses pathoanatomy as a starting point and expands the search to look for the other factors that may contribute to the patient’s symptoms.

Future Research

The concept of RI is still preliminary and speculative. Therefore, basic science as well as clinical research is required to more fully develop the model described in this paper. Specifically, evidence derived from prospective studies with the specific purpose of testing hypotheses related to RI concepts is required to establish a viable theory and validate a working model of RI.

The majority of supporting evidence that does exist has been taken from various musculoskeletal-related studies with other purposes and used inductively to construct the concept of RI. The revised RI model proposes that impairments in one region of the body can influence the musculoskeletal and neuromuscular function and symptoms in other remote regions of the body. Researchers should continue to focus on exploratory studies to establish potential new relationships, but should also focus on validating the studies that already exist with specific RI hypotheses in mind. Researchers have begun to validate the relationship between the thoracic spine and cervical impairments and also the hip and knee, but further validation is required. In addition, the revised RI model states that the interdependence between regions of the body may involve the musculoskeletal system, but that neurophysiological, biopsychosocial, and somatovisceral systems can also influence musculoskeletal function both locally and at remote sites. Research is needed to further establish whether and how such relationships exist and how they may influence clinical practice.

Conclusions

The revised definition of RI refers to the concept and clinical model that a patient’s primary musculoskeletal symptom(s) may be directly or indirectly related to or influenced by impairments from various body systems regardless of proximity to the primary symptom(s). Although initial local treatment of a patient’s primary complaint is typically a first step in clinical management, RI is a model that may be helpful in identifying treatment strategies for recalcitrant and persistent symptoms that may be due to associated functional limitations and impairments in more distant body regions as well as other body systems. The model of RI is in its infancy and will no doubt change and evolve as our understanding is informed from the results of future, formal investigations. The model presented in this paper is meant to serve as a framework for clinicians and researchers alike as they seek to identify the factors that may contribute to a patient’s impairments as well as for stimulating future research.

References

- 1.Wainner RS, Whitman JM, Cleland JA, Flynn TW. Regional interdependence: a musculoskeletal examination model whose time has come. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2007;37(11):658–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boyles RE, Ritland BM, Miracle BM, Barclay DM, Faul MS, Moore JH, et al. The short-term effects of thoracic spine thrust manipulation on patients with shoulder impingement syndrome. Man Ther. 2009;14(4):375–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cleland JA, Childs JD, McRae M, Palmer JA, Stowell T. Immediate effects of thoracic manipulation in patients with neck pain: a randomized clinical trial. Man Ther. 2005;10(2):127–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Currier LL, Froehlich PJ, Carow SD, McAndrew RK, Cliborne AV, Boyles RE, et al. Development of a clinical prediction rule to identify patients with knee pain and clinical evidence of knee osteoarthritis who demonstrate a favorable short-term response to hip mobilization. Phys Ther. 2007;87(9):1106–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mintken PE, Cleland JA, Carpenter KJ, Bieniek ML, Keirns M, Whitman JM. Some factors predict successful short-term outcomes in individuals with shoulder pain receiving cervicothoracic manipulation: a single-arm trial. Phys Ther. 2010;90(1):26–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Souza RB, Powers CM. Differences in hip kinematics, muscle strength, and muscle activation between subjects with and without patellofemoral pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2009;39(1):12–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strunce JB, Walker MJ, Boyles RE, Young BA. The immediate effects of thoracic spine and rib manipulation on subjects with primary complaints of shoulder pain. J Man Manip Ther. 2009;17(4):230–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bialosky JE, Bishop MD, George SZ. Regional interdependence: a musculoskeletal examination model whose time has come. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2008;38(3):159–60; author reply 160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wainner RS, Flynn TW, Whitman JM. Spinal and extremity manipulation: the basic skill set for physical therapists. San Antonio (TX): Manipulations, Inc; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bang MD, Deyle GD. Comparison of supervised exercise with and without manual physical therapy for patients with shoulder impingement syndrome. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2000;30(3):126–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cibulka MT. Low back pain and its relation to the hip and foot. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1999;29(10):595–601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Porter JL, Wilkinson A. Lumbar-hip flexion motion. A comparative study between asymptomatic and chronic low back pain in 18- to 36-year-old men. Spine. 1997;22(13):1508–13; discussion 1513–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Erhard R, Bowling R. The recognition and management of the pelvic component of low back and sciatic pain. Bull Orthop Sect Am Phys Ther Assoc. 1977;2(3):4–15 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maitland GD, Banks K, English K, Hengeveld E, editors. Maitland’s vertebral manipulation. 6th ed. Boston, MA: Butterworth-Heinemann; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bialosky JE, Bishop MD, Price DD, Robinson ME, George SZ. The mechanisms of manual therapy in the treatment of musculoskeletal pain: a comprehensive model. Man Ther. 2009;14(5):531–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chapman CR, Tuckett RP, Song CW. Pain and stress in a systems perspective: reciprocal neural, endocrine, and immune interactions. J Pain. 2008 Feb;9(2):122–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McEwen BS, Wingfield JC. What is in a name? Integrating homeostasis, allostasis and stress. Horm Behav. 2010;57(2):105–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McEwen BS. Stress, adaptation, and disease. Allostasis and allostatic load. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1998;840:33–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Craig AD. A new view of pain as a homeostatic emotion. Trends Neurosci. 2003;26(6):303–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Tulder MW, Koes BW, Bouter LM. Conservative treatment of acute and chronic nonspecific low back pain. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials of the most common interventions. Spine. 1997;22(18):2128–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bogduk N. What’s in a name? The labelling of back pain. Med J Aust. 2000;173(8):400–1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Waddell G. 1987 Volvo award in clinical sciences. A new clinical model for the treatment of low-back pain. Spine. 1987;12(7):632–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dishman JD, Cunningham BM, Burke J. Comparison of tibial nerve H-reflex excitability after cervical and lumbar spine manipulation. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2002;25(5):318–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.George SZ, Bishop MD, Bialosky JE, Zeppieri G, Jr, Robinson ME. Immediate effects of spinal manipulation on thermal pain sensitivity: an experimental study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2006;7:68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vicenzino B, Cleland JA, Bisset L. Joint manipulation in the management of lateral epicondylalgia: a clinical commentary. J Man Manip Ther. 2007;15(1):50–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sueki DG, Chaconcas EJ. The effect of thoracic manipulation on shoulder pain: a regional interdependence model. Phys Ther Rev. 2011;16(5):399–408 [Google Scholar]

- 27.George SZ, Wallace MR, Wright TW, Moser MW, Greenfield WH, 3rd, Sack BK, et al. Evidence for a biopsychosocial influence on shoulder pain: pain catastrophizing and catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) diplotype predict clinical pain ratings. Pain. 2008;136(1–2):53–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moseley GL. Evidence for a direct relationship between cognitive and physical change during an education intervention in people with chronic low back pain. Eur J Pain. 2004;8(1):39–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith MD, Russell A, Hodges PW. Do incontinence, breathing difficulties, and gastrointestinal symptoms increase the risk of future back pain? J Pain. 2009;10(8):876–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Inman VT, Saunders JB. Referred pain from skeletal structures. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1944;99:660–7 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Slocum DB. The mechanics of some common injuries to the shoulder in sports. Am J Surg. 1959;98:394–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fernandez-de-las-Penas C, Cleland JA, Huijbregts P, Palomeque-del-Cerro L, Gonzalez-Iglesias J. Repeated applications of thoracic spine thrust manipulation do not lead to tolerance in patients presenting with acute mechanical neck pain: a secondary analysis. J Man Manip Ther. 2009;17(3):154–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gonzalez-Iglesias J, Fernandez-de-las-Penas C, Cleland JA, Gutierrez-Vega Mdel R. Thoracic spine manipulation for the management of patients with neck pain: a randomized clinical trial. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2009;39(1):20–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stupar M, Cote P, French MR, Hawker GA. The association between low back pain and osteoarthritis of the hip and knee: a population-based cohort study. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2010;33(5):349–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ben-Galim P, Ben-Galim T, Rand N, Haim A, Hipp J, Dekel S, et al. Hip-spine syndrome: the effect of total hip replacement surgery on low back pain in severe osteoarthritis of the hip. Spine. 2007;32(19):2099–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Di Lorenzo L, Forte A, Formisano R, Gimigliano R, Gatto S. Low back pain after unstable extracapsular hip fractures: randomized control trial on a specific training. Eur Medicophys. 2007;43(3):349–57 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arab AM, Nourbakhsh MR. The relationship between hip abductor muscle strength and iliotibial band tightness in individuals with low back pain. Chiropr Osteopat. 2010;18:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Johnson EN, Thomas JS. Effect of hamstring flexibility on hip and lumbar spine joint excursions during forward-reaching tasks in participants with and without low back pain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;91(7):1140–2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mellin G. Correlations of hip mobility with degree of back pain and lumbar spinal mobility in chronic low-back pain patients. Spine. 1988;13(6):668–70 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arab AM, Ghamkhar L, Emami M, Nourbakhsh MR. Altered muscular activation during prone hip extension in women with and without low back pain. Chiropr Man Ther. 2011;19:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rothbart BA, Estabrook L. Excessive pronation: a major biomechanical determinant in the development of chondromalacia and pelvic lists. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1988;11(5):373–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kosashvili Y, Fridman T, Backstein D, Safir O, Bar Ziv Y. The correlation between pes planus and anterior knee or intermittent low back pain. Foot Ankle Int. 2008;29(9):910–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brantingham JW, Lee Gilbert J, Shaik J, Globe G. Sagittal plane blockage of the foot, ankle and hallux and foot alignment-prevalence and association with low back pain. J Chiropr Med. 2006;5(4):123–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Powers CM. The influence of abnormal hip mechanics on knee injury: a biomechanical perspective. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2010;40(2):42–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bolgla LA, Malone TR, Umberger BR, Uhl TL. Comparison of hip and knee strength and neuromuscular activity in subjects with and without patellofemoral pain syndrome. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2011;6(4):285–96 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Finnoff JT, Hall MM, Kyle K, Krause DA, Lai J, Smith J. Hip strength and knee pain in high school runners: a prospective study. J Inj Funct Rehabil. 2011;3(9):792–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rowe J, Shafer L, Kelley K, West N, Dunning T, Smith R, et al. Hip strength and knee pain in females. N Am J Sports Phys Ther. 2007;2(3):164–9 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Molgaard C, Rathleff MS, Simonsen O. Patellofemoral pain syndrome and its association with hip, ankle, and foot function in 16- to 18-year-old high school students: a single-blind case–control study. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2011;101(3):215–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yoo HS, Nahm FS, Lee PB, Lee CJ. Early thoracic sympathetic block improves the treatment effect for upper extremity neuropathic pain. Anesth Analg. 2011;113(3):605–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Berglund KM, Persson BH, Denison E. Prevalence of pain and dysfunction in the cervical and thoracic spine in persons with and without lateral elbow pain. Man Ther. 2008;13(4):295–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Walser RF, Meserve BB, Boucher TR. The effectiveness of thoracic spine manipulation for the management of musculoskeletal conditions: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J Man Manip Ther. 2009;17(4):237–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Suter E, McMorland G. Decrease in elbow flexor inhibition after cervical spine manipulation in patients with chronic neck pain. Clin Biomech. 2002;17(7):541–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lucado AM, Kolber MJ, Cheng MS, Ecternach JL. Subacromial impingement syndrome and lateral epicondylalgia in tennis players. Phys Ther Rev. 2010;15(2):55–61 [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ben Kibler W, Sciascia A. Kinetic chain contributions to elbow function and dysfunction in sports. Clin Sports Med. 2004;23(4):545–52, viii [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Klein MG, Whyte J, Keenan MA, Esquenazi A, Polansky M. The relation between lower extremity strength and shoulder overuse symptoms: a model based on polio survivors. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;81(6):789–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Steindler A. Kinesiology of the human body: under normal and pathological conditions. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas; 1955 [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bialosky JE, Bishop MD, Robinson ME, Barabas JA, George SZ. The influence of expectation on spinal manipulation induced hypoalgesia: an experimental study in normal subjects. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008;9:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bialosky JE, Bishop MD, Robinson ME, Zeppieri G, Jr, George SZ. Spinal manipulative therapy has an immediate effect on thermal pain sensitivity in people with low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Phys Ther. 2009;89(12):1292–303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Suter E, McMorland G, Herzog W. Short-term effects of spinal manipulation on H-reflex amplitude in healthy and symptomatic subjects. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2005;28(9):667–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Suter E, McMorland G, Herzog W, Bray R. Decrease in quadriceps inhibition after sacroiliac joint manipulation in patients with anterior knee pain. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1999;22(3):149–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dishman JD, Bulbulian R. Spinal reflex attenuation associated with spinal manipulation. Spine. 2000;25(19):2519–24; discussion 2525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Murphy BA, Dawson NJ, Slack JR. Sacroiliac joint manipulation decreases the H-reflex. Electromyogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1995;35(2):87–94 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dishman JD, Burke J. Spinal reflex excitability changes after cervical and lumbar spinal manipulation: a comparative study. Spine J. 2003;3(3):204–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hill JC, Fritz JM. Psychosocial influences on low back pain, disability, and response to treatment. Phys Ther. 2011;91(5):712–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cervero F, Laird JM. Visceral pain. Lancet. 1999;353(9170):2145–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Engel GL. The biopsychosocial model and the education of health professionals. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1978;310:169–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Main CJ, Richards HL, Fortune DG. Why put new wine in old bottles: the need for a biopsychosocial approach to the assessment, treatment, and understanding of unexplained and explained symptoms in medicine. J Psychosom Res. 2000;48(6):511–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Deuraseh N, Abu Talib M. Mental health in islamic medical tradition. Int Med J. 2005;4(2):76–9 [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sterling M, Jull G, Vicenzino B, Kenardy J, Darnell R. Physical and psychological factors predict outcome following whiplash injury. Pain. 2005;114(1–2):141–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.McFarlane AC. Stress-related musculoskeletal pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2007;21(3):549–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Engel GL. The clinical application of the biopsychosocial model. Am J Psychiatry. 1980;137(5):535–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.McCarthy C. The biopsychosocial classification of non specific low back pain: a systematic review. Phyis Ther Rev. 2004;9(1):17–30 [Google Scholar]

- 73.Overmeer T, Boersma K, Denison E, Linton SJ. Does teaching physical therapists to deliver a biopsychosocial treatment program result in better patient outcomes? A randomized controlled trial. Phys Ther. 2011;91(5):804–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bialosky JE, Bishop MD, Cleland JA. Individual expectation: an overlooked, but pertinent, factor in the treatment of individuals experiencing musculoskeletal pain. Phys Ther. 2010;90(9):1345–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.George SZ, Fritz JM, Bialosky JE, Donald DA. The effect of a fear-avoidance-based physical therapy intervention for patients with acute low back pain: results of a randomized clinical trial. Spine. 2003;28(23):2551–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fritz JM, George SZ, Delitto A. The role of fear-avoidance beliefs in acute low back pain: relationships with current and future disability and work status. Pain. 2001;94(1):7–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Moseley GL. Graded motor imagery is effective for long-standing complex regional pain syndrome: a randomised controlled trial. Pain. 2004;108(1–2):192–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Moseley GL. Graded motor imagery for pathologic pain: a randomized controlled trial. Neurology. 2006;67(12):2129–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Butler AJ, Page SJ. Mental practice with motor imagery: evidence for motor recovery and cortical reorganization after stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;87(12 Suppl 2):S2–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.van Oosterwijck J, Nijs J, Meeus M, Truijen S, Craps J, van den Keybus N, et al. Pain neurophysiology education improves cognitions, pain thresholds, and movement performance in people with chronic whiplash: a pilot study. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2011;48(1):43–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Pollo A, Amanzio M, Arslanian A, Casadio C, Maggi G, Benedetti F. Response expectancies in placebo analgesia and their clinical relevance. Pain. 2001;93(1):77–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Carroll LJ, Cassidy JD, Cote P. Depression as a risk factor for onset of an episode of troublesome neck and low back pain. Pain. 2004;107(1–2):134–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Otis JD, Keane TM, Kerns RD. An examination of the relationship between chronic pain and post-traumatic stress disorder. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2003;40(5):397–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Arguelles LM, Afari N, Buchwald DS, Clauw DJ, Furner S, Goldberg J. A twin study of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and chronic widespread pain. Pain. 2006;124(1–2):150–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Linton SJ, Buer N, Vlaeyen J, Hellsing AL. Are fear-avoidance beliefs related to the inception of an episode of back pain? A prospective study. Psychol Health. 2000;14(6):1051–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Al-Obaidi SM, Nelson RM, Al-Awadhi S, Al-Shuwaie N. The role of anticipation and fear of pain in the persistence of avoidance behavior in patients with chronic low back pain. Spine. 2000;25(9):1126–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Carty J, O’Donnell M, Evans L, Kazantzis N, Creamer M. Predicting posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and pain intensity following severe injury: the role of catastrophizing. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2011;2:10.3402/ejpt.v2i0.5652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tan G, Jensen M, Thornby J, Sloan P. Negative emotions, pain, and functioning. Psychol Serv. 2008;5(1):26–35 [Google Scholar]

- 89.Arendt-Nielsen L, Svensson P. Referred muscle pain: basic and clinical findings. Clin J Pain. 2001;17(1):11–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Astephen JL, Deluzio KJ, Caldwell GE, Dunbar MJ. Biomechanical changes at the hip, knee, and ankle joints during gait are associated with knee osteoarthritis severity. J Orthop Res. 2008;26(3):332–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sengupta JN. Visceral pain: the neurophysiological mechanism. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2009(194):31–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Gerwin R. Myofascial and visceral pain syndromes: visceral-somatic pain representations. J Musculoskelet Pain. 2002;10(2):165–75 [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hyman PE, Bursch B, Sood M, Schwankovsky L, Cocjin J, Zeltzer LK. Visceral pain-associated disability syndrome: a descriptive analysis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2002;35(5):663–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Smith MD, Russell A, Hodges PW. How common is back pain in women with gastrointestinal problems? Clin J Pain. 2008;24(3):199–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Guide to Physical Therapist Practice Second Edition. American Physical Therapy Association. Phys Ther. 2001;81(1):9–746 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wainner RS, Gill H. Diagnosis and nonoperative management of cervical radiculopathy. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2000;30(12):728–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Boyd BS, Wanek L, Gray AT, Topp KS. Mechanosensitivity of the lower extremity nervous system during straight-leg raise neurodynamic testing in healthy individuals. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2009;39(11):780–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Coppieters MW, Alshami AM. Longitudinal excursion and strain in the median nerve during novel nerve gliding exercises for carpal tunnel syndrome. J Orthop Res. 2007;25(7):972–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Abenhaim L, Rossignol M, Gobeille D, Bonvalot Y, Fines P, Scott S. The prognostic consequences in the making of the initial medical diagnosis of work-related back injuries. Spine. 1995;20(7):791–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Fritz JM, Brennan GP. Preliminary examination of a proposed treatment-based classification system for patients receiving physical therapy interventions for neck pain. Phys Ther. 2007;87(5):513–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Walker MJ, Boyles RE, Young BA, Strunce JB, Garber MB, Whitman JM, et al. The effectiveness of manual physical therapy and exercise for mechanical neck pain: a randomized clinical trial. Spine. 2008;33(22):2371–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Cleland JA, Mintken PE, Carpenter K, Fritz JM, Glynn P, Whitman J, et al. Examination of a clinical prediction rule to identify patients with neck pain likely to benefit from thoracic spine thrust manipulation and a general cervical range of motion exercise: multi-center randomized clinical trial. Phys Ther. 2010;90(9):1239–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Bunn EA, Grindstaff TL, Hart JM, Hertel J, Ingersoll CD. Effects of paraspinal fatigue on lower extremity motoneuron excitability in individuals with a history of low back pain. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2011;21(3):466–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.de Oliveira Grassi D, de Souza MZ, Ferrareto SB, de Lima Montebelo MI, de Oliveira Guirro EC. Immediate and lasting improvements in weight distribution seen in baropodometry following a high-velocity, low-amplitude thrust manipulation of the sacroiliac joint. Man Ther. 2011;16(5):495–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Iverson CA, Sutlive TG, Crowell MS, Morrell RL, Perkins MW, Garber MB, et al. Lumbopelvic manipulation for the treatment of patients with patellofemoral pain syndrome: development of a clinical prediction rule. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2008;38(6):297–309; discussion 312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Burns SA, Mintken PE, Austin GP. Clinical decision making in a patient with secondary hip-spine syndrome. Physiother Theory Pract. 2011;27(5):384–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Lowry CD, Cleland JA, Dyke K. Management of patients with patellofemoral pain syndrome using a multimodal approach: a case series. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2008;38(11):691–702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Vaughn DW. Isolated knee pain: a case report highlighting regional interdependence. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2008;38(10):616–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Welsh C, Hanney WJ, Podschun L, Kolber MJ. Rehabilitation of a female dancer with patellofemoral pain syndrome: applying concepts of regional interdependence in practice. N Am J Sports Phys Ther. 2010;5(2):85–97 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Isabel de-la-Llave-Rincon A, Puentedura E, Fernandez-de-las-Penas C. Clinical presentation and manual therapy for upper quadrant musculoskeletal conditions. J Man Manip Ther. 2011;19(4):201–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Reiman MP, Weisbach PC, Glynn PE. The hips influence on low back pain: a disal link to a proximal problem. J Sports Rehabil. 2009;18(1):24–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Ellison JB, Rose SJ, Sahrmann SA. Patterns of hip rotation range of motion: a comparison between healthy subjects and patients with low back pain. Phys Ther. 1990;70(9):537–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Kendall KD, Schmidt C, Ferber R. The relationship between hip-abductor strength and the magnitude of pelvic drop in patients with low back pain. J Sport Rehabil. 2010;19(4):422–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Nadler SF, Malanga GA, Feinberg JH, Prybicien M, Stitik TP, DePrince M. Relationship between hip muscle imbalance and occurrence of low back pain in collegiate athletes: a prospective study. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;80(8):572–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Nelson-Wong E, Flynn T, Callaghan JP. Development of active hip abduction as a screening test for identifying occupational low back pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2009;39(9):649–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Paquet N, Malouin F, Richards CL. Hip-spine movement interaction and muscle activation patterns during sagittal trunk movements in low back pain patients. Spine. 1994;19(5):596–603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.van Dillen LR, Bloom NJ, Gombatto SP, Susco TM. Hip rotation range of motion in people with and without low back pain who participate in rotation-related sports. Phys Ther Sport. 2008;9(2):72–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Yoshimoto H, Sato S, Masuda T, Kanno T, Shundo M, Hyakumachi T, et al. Spinopelvic alignment in patients with osteoarthrosis of the hip: a radiographic comparison to patients with low back pain. Spine. 2005;30(14):1650–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Deyle GD, Allison SC, Matekel RL, Ryder MG, Stang JM, Gohdes DD, et al. Physical therapy treatment effectiveness for osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized comparison of supervised clinical exercise and manual therapy procedures versus a home exercise program. Phys Ther. 2005;85(12):1301–17 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Deyle GD, Henderson NE, Matekel RL, Ryder MG, Garber MB, Allison SC. Effectiveness of manual physical therapy and exercise in osteoarthritis of the knee. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132(3):173–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Suri P, Morgenroth DC, Kwoh CK, Bean JF, Kalichman L, Hunter DJ. Low back pain and other musculoskeletal pain comorbidities in individuals with symptomatic osteoarthritis of the knee: data from the osteoarthritis initiative. Arthritis Care Res. 2010;62(12):1715–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Bjonness T. Low back pain in persons with congenital club foot. Scand J Rehabil Med. 1975;7(4):163–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Bennell KL, Hunt MA, Wrigley TV, Hunter DJ, Hinman RS. The effects of hip muscle strengthening on knee load, pain, and function in people with knee osteoarthritis: a protocol for a randomised, single-blind controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2007;8:121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Bolgla LA, Malone TR, Umberger BR, Uhl TL. Hip strength and hip and knee kinematics during stair descent in females with and without patellofemoral pain syndrome. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2008;38(1):12–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Vicenzino B, Collins D, Wright A. The initial effects of a cervical spine manipulative physiotherapy treatment on the pain and dysfunction of lateral epicondylalgia. Pain. 1996;68(1):69–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]