Abstract

Background

An association between multiple sclerosis (MS) prevalence as well as MS mortality and vitamin D nutrition has led to the hypothesis that high levels of vitamin D could be beneficial for MS. The purpose of this systematic review is to establish whether there is evidence for or against vitamin D in the treatment of MS.

Methods

Systematic literature searches were performed to locate randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trials measuring the clinical effect of vitamin D on MS in human participants. Data were extracted in a standardized manner and methodological quality was assessed by the Jadad score.

Results

Five trials were located meeting the selection criteria. Of the five trials, four showed no effect of vitamin D on any outcome, and one showed a significant effect, namely upon reduction in the number of T1 enhancing lesions on brain magnetic resonance imaging. Three studies commented on adverse effects of vitamin D, with gastrointestinal adverse effects being the most frequently reported. The literature is limited by small study sizes (studies size ranged from 23 to 68 patients) and heterogeneity of dosing, form of vitamin D tested (vitamin D3 in four trials, and vitamin D2 in one), and outcome clinical measures. Therefore, a meta-analysis was not performed.

Conclusions

The evidence for vitamin D as a treatment for MS is inconclusive. Larger studies are warranted to assess the effect of vitamin D on clinical outcomes in patients with MS. We further encourage researchers to also test the effect of vitamin D on the health-related quality of life experienced by patients and their families.

Keywords: Multiple sclerosis, treatment, systematic review, vitamin D

INTRODUCTION

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is one of the most common chronic neurological disorders among young adults, especially in high latitude regions, and the most common cause of non-trauma related disability in this group of age.[1–4] The broad spectrum of symptoms of MS considerably impact upon the health-related quality of life (HRQoL) experienced by patients and their families to a greater extent than several other chronic diseases.[5–14] It is therefore imperative to focus research efforts on the search for the pathogenesis of this disease. The pathogenesis of MS is complex and likely involves multiple genes and their interactions with environmental factors. Although an increasing body of evidence suggests that this disease may be mediated by an autoimmune reaction among susceptible people to a widespread pathogen,[15,16] that is ubiquitous in the developed world, there are data which suggest that other non-genetic (environmental) factors, especially vitamin D deficiency, may play a role in MS.[17]

Vitamin D is a steroid hormone with pleiotropic effects including calcium homeostasis, immune system modulation, and lung tissue remodelling.[18,19] Humans get vitamin D from exposure from sunlight, from their diet, and from diet supplements.[18,19] Vitamin D is found in two forms: vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) and vitamin D2 (ergocalciferol).[18,19] Vitamin D2 is manufactured through the ultraviolet irradiation of ergosterol from yeast, meanwhile vitamin D3 through the ultraviolet irradiation of 7-dehydrocholesterol from lanolin.[18,19] Vitamin D from the skin and diet is metabolized in the liver to 25-hydroxyvitamin D, which is used to determine a patient’s vitamin status.[18–20]

Epidemiologic evidence supports an association between vitamin D and autoimmune disorders susceptibility and severity.[18] In the specific case of MS, correlations of lower MS prevalence, activity, and mortality with high levels of vitamin D nutrition have led to the hypothesis that high levels of vitamin D could be beneficial for MS.[21,22] Most convincingly, risk of relapse decreased by up to 12% for every 10 nmol/L increase in serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D in a prospective population-based cohort study.[23] However, there are unresolved clinical questions related to vitamin D and MS. Does aggressive vitamin D supplementation in patients with MS change the disease outcome? If so, what would be the optimal dose?

In a 2010 Cochrane review, Jagannath et al.[24] found that the efficacy of vitamin D supplementation in the management of MS was doubtful. Specifically, the evidence for the effectiveness of vitamin D supplementation in MS was only based on an open-label, randomized, prospective, controlled trial with potential high risk of bias.[25] The trial was not powered or blinded to properly address clinical outcomes.[25] Since that time, a number of double-blind, placebo-controlled trials have been conducted. In view of the importance of the subject matter and the absence of a recent comprehensive review of the role of vitamin D in the treatment of MS, we undertook a systematic review with the aim of summarizing the existing evidence for or against the hypothesis that vitamin D may be an efficacious therapy for MS. In this systematic review, we focused on randomized, controlled, double-blinded trials, since this design is the best choice to assess therapeutic efficacy while reducing the risks of study bias and confounding factors that influence interpretation of results.[26]

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Search strategy and information sources

Searches were performed in August 2012 for randomized, controlled, double-blinded trials of vitamin D supplementation in the management of MS, using PubMed/Medline, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials. The keywords were different combinations of “vitamin D treatment” or “vitamin D therapy or “treatment with vitamin D” or “vitamin D supplementation” with “multiple sclerosis” or “MS”. In addition, our own extensive files were searched, including all reviews of vitamin D supplementation in the management of MS. Original articles were obtained, and all reference lists were scanned for further relevant articles. No time limit was applied in our search strategy.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All articles were included which reported a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials in which subjects with MS were allocated at random to receive either vitamin D or placebo. We only included articles, which focused on treatment effect on clinical (disease progression as determined by Expanded Disability Status Scale [EDSS] or Multiple Sclerosis Functional Composite [MSFC], relapse rate, proportion of relapse-free patients, and cognitive functioning), health-related quality of life, or neuroimaging parameters.

The search was limited to human clinical trials. We also excluded open-label studies and those ones, which were based on self-reported dietary vitamin D intake or whose endpoints were exclusively percentage change in bone mineral density or laboratory parameters, such as cytokine profile or peripheral blood mononuclear cell proliferative responses, among others. No language restrictions were applied.

Data extraction

Two investigators (B.P.-M., J.B.-L.) independently reviewed the title and abstract of all citations identified by the initial search strategy and excluded citations that clearly did not meet the inclusion criteria. We retrieved the full text of the remaining studies and both investigators reviewed each study to assess whether it met the inclusion criteria. All differences were settled by discussion. For each study, trial design, randomization, blinding and handling of drop-outs were recorded, in addition to inclusion and exclusion criteria, details of treatment and control procedures, main outcome measure and study result. Outcomes included in the systematic review were limited to the clinical efficacy or toxicity of vitamin D in patients with MS. We defined efficacy as the therapeutic effect of vitamin D and toxicity as any unintended adverse consequence of the drug’s use. The initial protocol for this review anticipated that results from several studies could be combined in a meta-analysis, but this was precluded by the heterogeneity of the studies.

Quality assessment

The quality of studies was assessed by the system of Jadad et al.,[27] Points were awarded as follows: study described as randomized, 1 point; additional point for appropriate method, 1 point; inappropriate randomization method, deduct 1 point; subject blinded to intervention, 1 point; evaluator blinded to therapy, 1 point; inappropriate method of blinding, deduct 1 point; description of withdrawals and dropouts, 1 point. The maximum points available were 5. Observer blinding was only scored if specified in the text.

RESULTS

Description of studies

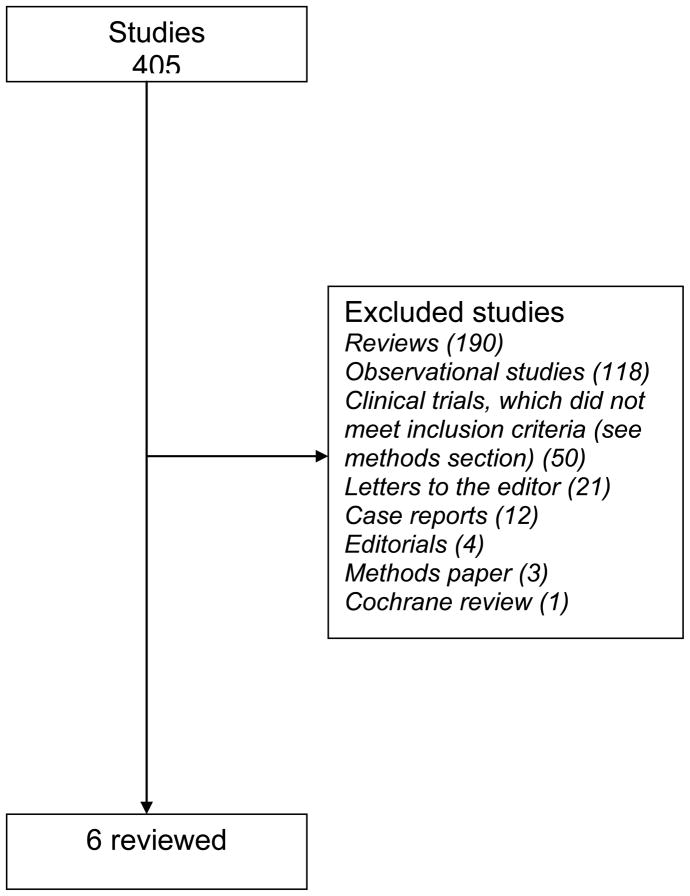

The electronic search identified a total of 405 publications of which six articles met our inclusion criteria.[28–33] (Figure 1) However, the study by Aivo et al.[33] was a sub-study of another main trial.[31] Of the five trials included, four gained the maximum score;[29–32] one study scored two points (the authors did not mentioned randomization and blinding procedures, as well as the reasons for patient withdrawals and dropouts for each treatment group).[28] The randomization procedure was reported in sufficient detail to be sure that it was appropriate in four studies.[29–32] In one study, the randomization procedure was not reported.[28] Likewise, double blinding method was appropriately explained in four studies;[29–32] in one study was nor reported.[28]. In all the studies,[29–32] except one,[28] the reasons for patients’ withdrawals and dropouts were not described.

Figure 1.

Identification of studies in the systematic review.

The study size ranged from 23 to 68 patients. All the randomized controlled trials had parallel designs. Only two studies reported a power calculation.[31,32] Two studies did not report a funding source,[28,32] one received an unrestricted grant from a manufacturer of vitamin D,[31] and the remaining trials received only the drug and placebo from a manufacturer.[29,30]

The studies were marked by heterogeneity of vitamin D dosing, vitamin D supplementation forms (vitamin D2 or vitamin D3), and outcomes measured (see Table 1 for details).

TABLE 1.

Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trials of Vitamin D for Treatment of Multiple Sclerosis: Study Characteristics and Results

| Author (date) | Jadad et al [27] score | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | Treatment group/controls (n =) | Intervention | Clinical and/or neuroimaging outcome measures | Clinical and/or neuroimaging results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mosayebi et al. (2011) [28] | 2 | Patients with MS and: at least one relapse in the previous 12 months; more than three lesions on spinal or brain-MRI or both; baseline EDSS from 0 to 3.5; and age from 18–60 yrs | Clinically isolated syndrome, progressive MS; MS patients with clinical relapses occurring during the study, drug abuse, use of digitalis or vitamin D supplementation; any condition predisposing to hypercalcemia; nephrolithiasis or renal insufficiency; pregnancy or unwillingness to use contraception; and unwillingness to restrict dietary calcium | 28/34 | 300,000 IU vitamin D3 every month for 6 months | EDSS and brain MRI | No significant difference between the treatment and the control groups in the EDSS scores and number of gadolinium-enhancing lesions during the 6-month treatment period |

| Stein et al. (2011) [29] | 5 | Patients with relapsing-remitting MS; aged >18 years; relapse within the preceding 24 months despite immunomodulatory therapy; or declined or could not tolerate such therapy | Progressive MS, pregnancy; clinical relapse or systemic glucocorticoid therapy within the prior 30 days; EDSS score >5; current MS treatment other than glatiramer acetate or interferon; hypercalcemia; creatinine >0.2 mM; estimated glomerular filtration rate <60 mL/min, and uric acid >sex-matched laboratory reference range | 11/12 | During 6 months, one group (high-dose D2) received 1,000 IU vitamin D2 daily plus a high-dose vitamin D2 supplement. The other group (low-dose D2) received 1,000 IU vitamin D2 daily plus a placebo supplement | EDSS, number of clinical relapses and MRI | No significant treatment differences were detected in the primary MRI endpoints. Follow-up EDSS after adjustment for baseline EDSS was higher following high-dose D2 than following low-dose D2 (p<0.05). There were 4 relapses with high-dose D2 vs. none with low-dose D2 (p<0.04) |

| Kampman et al. (2012) [30] | 5 | Patients with MS with clinically definite MS, according to the McDonald criteria, aged 18–50 years and with an EDSS score ≤4.5 | Inability to walk ≥500 m; history of conditions or diseases affecting bone; pregnancy or lactating during the past 6 months; use of bone-active medications other than intravenous methylprednisolone for treatment of relapses; a history of nephrolithiasis during the previous 5 years; menopause; unwillingness to use appropriate contraception | 35/33 | 20,000 IU vitamin D3 once a week, for two years | Annualised relapse rate, EDSS, MSFC components, grip strength, and fatigue | There was no significant difference between groups in annualised relapse rate, EDSS, MSFC components, grip strength or fatigue |

| Soilu-Hanninen et al. (2012) [31] | 5 | Patients with relapsing- remitting MS (McDonald criteria); aged 18–55 years; with interferon β-1b use for at least 1 month; no neutralising antibodies to interferon β; EDSS score ≤5.0; using appropriate contraceptive methods (women of childbearing potential) | Serum calcium >2.6 mmol/l; serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D >85 nmol/l; primary hyperparathyroidism; pregnancy or unwillingness to use contraception; alcohol or drug abuse; use of immunomodulatory therapy other than interferon β-1b; known allergy to cholecalciferol or peanuts; therapy with digitalis, calcitonin, vitamin D3 analogues or vitamin D; any condition predisposing to hypercalcemia; sarcoidosis; nephrolithiasis or renal insufficiency; significant hypertension; dysthyroidism in the year before the study began; a history of kidney stones in the previous 5 years; cardiac insufficiency or significant cardiac dysrhythmia; unstable ischaemic heart disease; depression; and inability to perform serial MRI scans | 32/30 | 20,000 IU vitamin D3 once a week, for one year | Annual relapse rate, EDSS score, timed 25 foot walk test and timed 10 foot tandem walk tests, brain MRI, and adverse effects | There was a statistically significant reduction in the number of T1 enhancing lesions and trends in MRI burden of disease and EDSS. There were no significant differences in adverse events or in the annual relapse rate. |

| Shaygannejad et al. (2012) [32] | 5 | Patients with relapsing-remitting MS (McDonald criteria); aged 15–60 years, stable neurological functioning for at least one month prior to study entry; EDSS score ≤6; serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D level >40 ng/mL; and a willingness to continue current medications for the duration of the study. | Progressive MS, evidence of substantial abnormalities in neurological, psychiatric, cardiac, endocrinological, hematologic, hepatic, renal, or metabolic functions; use of digitalis, vitamin D supplement, any condition predisposing to hypercalcemia, nephrolithiasis, renal insufficiency, and pregnancy | 25/25 | 0.25 μg calcitriol per day and increased to 0.5 μg/day after 2 weeks and continued for one year | EDSS and relapse rate | Average EDSS and relapse rate at the end of trial did not differ between groups. |

Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS); Multiple sclerosis functional composite (MSFC); Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI); Multiple sclerosis (MS)

Outcomes

Overall, the results of the four studies,[28–30,32] showed no effect ((i.e., supplementation with vitamin D did not result in beneficial effects on the measured MS-related outcomes). One showed a positive association,[31,33]

In Moyasebi et al’s study,[28] 62 patients were randomised to once monthly intramuscular 300,000 IU vitamin D3 injections or placebo intramuscular injections, and EDSS, mean number of brain gadolinium enhancing lesions, relapses and T cell function were studied at baseline and at 6 months. No significant differences were found in clinical or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) parameters in this trial but lymphocyte proliferation was decreased in the treated patients.[28]

Stein et al.[29] tested for a benefit of high-dose (6000 IU/day) vitamin D2 over low-dose (1000 IU/day) in patients with clinically active relapsing-remitting MS. There was no between-group difference in the primary MRI-based outcome measures (cumulative number of new gadolinium-enhancing lesions and change in the total volume of T2 lesions). However, there was a higher exit EDSS (p=0.05) and a higher proportion exhibiting relapse with high-dose vitamin D2 (p=0.04). However, the trial was limited by a small and selected patient sample (23 MS patients).[29] Nineteen of the patients were either receiving glatiramer acetate or interferon therapy and three patients withdrew, making the ultimate number of comparable patients in each treatment arm very small.[29]

Kampman et al.[30] reported outcomes from 62 MS patients in a 96-week trial, which was originally designed to assess the effect of high-dose vitamin D3 supplementation on bone mineral density in persons with multiple sclerosis.[34] A weekly dose of 20,000 IU vitamin D3 did not affected the course of the disease as assessed by measures of disease activity, functional tests, and the fatigue severity score.[30] The study was not powered to properly address clinical outcomes.[30]

Soilu-Hänninent et al.[31] showed a statistically significant reduction in the number of T1 enhancing lesions and trends in T2 burden of disease on MRI and EDSS in a controlled trial with 20,000 IU/week of vitamin D3 for one year in relapsing-remitting patients under interferon b-1b. However, due to the small sample size (62 MSs patients), the trial was not powered to address clinical outcomes.[31] The same researchers have recently published a subgroup analysis of this trial with 15 patients in the vitamin D arm and 15 patients in the placebo arm, who had either at least one relapse during the year preceding the study or enhancing T1 lesions at the baseline MRI scan.[33] They found a statistically significant reduction in the number of T1 enhancing lesions, a smaller T2 lesion volume growth and less new/enlarging T2 brain MRI lesions in the vitamin D3-treated than in the placebo-treated subgroup patients.[33] The MRI results were therefore slightly more pronounced in this subgroup than in the overall study population.[33]

Finally, Shaygannejad et al.[32] found no significant difference in relapse rate or change in EDSS between 25 MS patients who took the placebo versus 25 who received adjunct low-dose (escalating calcitriol - 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 - doses up to 0.5 μg/day) oral vitamin D during 12 months.

Adverse Effects/Toxicity

Only one of the studies that met our inclusion criteria used toxicity (adverse effects) as a primary end point.[31] Furthermore, the methods for surveillance of unintended effects of treatment were not described in any of the studies, but the Norwegian trial.[31] Adverse effects were reported in three of the five studies.[30–32] These were relatively mild with gastrointestinal adverse effects being the most frequently reported and included diarrhoea, constipation, dyspepsia, fever, fatigue, and headache.

Summary Statistics

Because of the heterogeneity of the variable dosing, and the different outcome measures used in the five studies, we deemed a meta-analysis inappropriate. Thus, no pooled estimates of effect or risk of therapy are reported. Similarly, combined estimates of dose response were not considered appropriate in light of the wide variability in outcome measures. This heterogeneity and the nature of the outcomes made a funnel plot to assess for publication bias infeasible. Again, due to the small number of patients included, it seems unlikely that small effect can be ruled out.

DISCUSSION

In this review, we tried to elucidate whether there is evidence for or against the clinical efficacy of vitamin D in the treatment of MS following a systematic approach to the randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trials published up to August 2012 in PubMed/Medline and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials databases. Our conclusions are as follows. Firstly, there are only very few studies (five in total) on the effect of vitamin on clinical outcomes in MS. Secondly, the literature is marked by small study sizes and heterogeneity of dosing, form of vitamin D tested (vitamin D3 in four trials, and vitamin D2 in one), and outcome clinical measures. Issues related to treatment duration were not emphasized in this review because there are no current standards for optimal recommended treatment duration. Given the relative lack of dose-response studies, it is unclear whether any of the studies used an optimal dose, although most were consistent with expert recommendations.[17] However, these studies highlight both the clinical questions and the potential methodologic issues that remain to be addressed by future studies. Thirdly, four studies showed no effect of vitamin D on any outcome although one,[31,33] showed significant improvement on brain MRI parameters. The reported adverse effects were otherwise relatively mild with gastrointestinal adverse effects being the most frequently reported. Therefore, the available evidence substantiates neither clinically significant benefit nor harm from vitamin D in the treatment of patients with MS.

Furthermore, because all the studies published were relatively small, it is possible that the negative studies in the literature were underpowered to detect an effect. The studies had sample sizes between 23 to 68 participants. Perhaps more problematic was the failure to calculate sample size in three of the studies, and thus, these studies were likely underpowered to detect group differences. An alternative explanation for the negative results in these trials, in addition to the small sample sizes, is that the possible protective effect of vitamin D may be attenuated or not present at all in individuals carrying the HLA-DR15 MS risk allele.[35] In other words, there is the possibility that the putative beneficial effect of vitamin D on MS could be masked by subgroups of non-responders. Furthermore, none of the trials included patients with progressive MS. It is possible that vitamin D may have differential efficacy according to the different subgroups of MS. We recommend researchers to further stratify by HLA-DR15 status in future clinical trials and include patients with progressive forms of MS.

The results of our systematic review are limited by the availability of studies in the public domain and, specifically, on PubMed. Because of the heterogeneity of studies and the types of outcomes reported, we were unable to formally assess for publication bias, although it does seem likely that many small negative studies remain unpublished.

We felt that quality and heterogeneity of the studies made combining studies in a meta-analysis for an overall estimate of effect inappropriate. Therefore, to fully evaluate the current state of the evidence of vitamin D on MS outcomes, we decided that a descriptive synthesis of the literature was most appropriate.

The quality of the studies reviewed was rated using the Jadad scoring criteria for potential sources of bias (higher scores indicates higher quality) (see Table 1). Four studies had Jadad scores of 5. The studies of highest quality, but one,[31,33] did not find vitamin D to be significantly superior to placebo

Two on-going high-quality randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trials are currently being conducted.[36,37] The first one, the SOLAR study, is a 96-week three-arm, multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, phase II trial designed to evaluate the efficacy of vitamin D3 (14,000 IU/daily) as add-on therapy to subcutaneous interferon beta-1a in relapsing–remitting MS (n = 174 in both treatment arms).[36] The second one, the EVIDIMS study, is a German multi-center, stratified, randomized, controlled and double-blind clinical phase II pilot trial. Eighty patients with the diagnosis of definite MS or clinically isolated syndrome who are on a stable immunomodulatory treatment with interferon-β1b will be randomized to additionally receive either high-dose (average daily dose 10.200 IU) or low-dose (average daily dose 200 IU) vitamin D3 for a total period of 18 months.[37] It is very probable that both trials will substantially contribute to the evaluation of the efficacy of high-dose vitamin D supplementation in MS patients.

In closing, there remains a lack of definitive evidence regarding the clinical efficacy of vitamin D for the treatment of patients with MS. Additional work is needed to clarify the subpopulations most likely to be benefited by vitamin D therapy, the optimal dosing for these subgroups, and the most valid and clinically significant outcome measures in these populations. Specifically, we further encourage researchers to test the effect of vitamin D on the HRQoL experienced by patients and their families.[5–14] In the last few years, clinical trials of new pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments for MS have begun to incorporate HRQoL measures as primary or secondary outcome points. [5–14]

Ultimately, larger randomized placebo-controlled clinical trials with longer follow-up than one year of vitamin D in MS will be necessary. Until such studies are completed, clinicians can only continue to judiciously treat and monitor the patients with vitamin D under their care.

Acknowledgments

Funding

Dr. Benito-León is supported by NIH R01 NS039422 from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Beatriz Pozuelo-Moyano: Research project conception, organization and execution; manuscript writing (writing the first draft and making subsequent revisions).

Julián Benito-León: Research project conception, organization and execution; manuscript writing (writing the first draft and making subsequent revisions).

Alex J. Mitchell: Research project conception and organization; manuscript writing (making subsequent revisions).

Jesús Hernández-Gallego: Manuscript writing (making subsequent revisions).

References

- 1.Pugliatti M, Sotgiu S, Rosati G. The worldwide prevalence of multiple sclerosis. Clinical neurology and neurosurgery. 2002;104:182–191. doi: 10.1016/s0303-8467(02)00036-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benito-Leon J, Martin E, Vela L, Villar ME, Felgueroso B, Marrero C, Guerrero A, Ruiz-Galiana J. Multiple sclerosis in mostoles, central spain. Acta neurologica Scandinavica. 1998;98:238–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1998.tb07302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benito-Leon J. Multiple sclerosis: Is prevalence rising and if so why? Neuroepidemiology. 2011;37:236–237. doi: 10.1159/000334606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poser CM, Brinar VV. The accuracy of prevalence rates of multiple sclerosis: A critical review. Neuroepidemiology. 2007;29:150–155. doi: 10.1159/000111576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benito-Leon J, Morales JM, Rivera-Navarro J, Mitchell A. A review about the impact of multiple sclerosis on health-related quality of life. Disability and rehabilitation. 2003;25:1291–1303. doi: 10.1080/09638280310001608591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mitchell AJ, Benito-Leon J, Gonzalez JM, Rivera-Navarro J. Quality of life and its assessment in multiple sclerosis: Integrating physical and psychological components of wellbeing. Lancet neurology. 2005;4:556–566. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(05)70166-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rivera-Navarro J, Benito-Leon J, Oreja-Guevara C, Pardo J, Dib WB, Orts E, Bello M Caregiver Quality of Life in Multiple Sclerosis Study G. Burden and health-related quality of life of spanish caregivers of persons with multiple sclerosis. Multiple sclerosis. 2009;15:1347–1355. doi: 10.1177/1352458509345917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benito-Leon J, Rivera-Navarro J, Guerrero AL, de Las Heras V, Balseiro J, Rodriguez E, Bello M, Martinez-Martin P caregiver quality of life in multiple sclerosis Study G. The careqol-ms was a useful instrument to measure caregiver quality of life in multiple sclerosis. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2011;64:675–686. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benito-Leon J, Mitchell AJ, Rivera-Navarro J, Morales-Gonzalez JM. Impaired health-related quality of life predicts progression of disability in multiple sclerosis. European journal of neurology: the official journal of the European Federation of Neurological Societies. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2012.03792.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benito-Leon J, Martinez-Martin P. health-related quality of life in multiple sclerosis. Neurologia. 2003;18:210–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rivera-Navarro J, Benito-Leon J. the social dimension of the quality of life in multiple sclerosis. Revista de neurologia. 2011;52:127. author reply 127–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rivera-Navarro J, Benito-Leon J, Morales-Gonzalez JM. searching for more specific dimensions for the measurement of quality of life in multiple sclerosis. Revista de neurologia. 2001;32:705–713. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rivera-Navarro J, Morales-Gonzalez JM, Benito-Leon J Madrid Demyelinating Diseases G. Informal caregiving in multiple sclerosis patients: Data from the madrid demyelinating disease group study. Disability and rehabilitation. 2003;25:1057–1064. doi: 10.1080/0963828031000137766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benito-Leon J, Morales JM, Rivera-Navarro J. Health-related quality of life and its relationship to cognitive and emotional functioning in multiple sclerosis patients. European journal of neurology: the official journal of the European Federation of Neurological Societies. 2002;9:497–502. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-1331.2002.00450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ascherio A, Munger KL. Epstein-barr virus infection and multiple sclerosis: A review. Journal of neuroimmune pharmacology: the official journal of the Society on Neuro Immune Pharmacology. 2010;5:271–277. doi: 10.1007/s11481-010-9201-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benito-Leon J, Pisa D, Alonso R, Calleja P, Diaz-Sanchez M, Carrasco L. Association between multiple sclerosis and candida species: Evidence from a case-control study. European journal of clinical microbiology & infectious diseases: official publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology. 2010;29:1139–1145. doi: 10.1007/s10096-010-0979-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ho SL, Alappat L, Awad AB. Vitamin d and multiple sclerosis. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition. 2012;52:980–987. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2010.516034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holick MF. Vitamin d deficiency. The New England journal of medicine. 2007;357:266–281. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra070553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stroud ML, Stilgoe S, Stott VE, Alhabian O, Salman K. Vitamin d - a review. Australian family physician. 2008;37:1002–1005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saltyte Benth J, Myhr KM, Loken-Amsrud KI, Beiske AG, Bjerve KS, Hovdal H, Midgard R, Holmoy T. Modelling and prediction of 25-hydroxyvitamin d levels in norwegian relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis patients. Neuroepidemiology. 2012;39:84–93. doi: 10.1159/000339360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ascherio A, Munger KL, Simon KC. Vitamin d and multiple sclerosis. Lancet neurology. 2010;9:599–612. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70086-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McDowell TY, Amr S, Culpepper WJ, Langenberg P, Royal W, Bever C, Bradham DD. Sun exposure, vitamin d and age at disease onset in relapsing multiple sclerosis. Neuroepidemiology. 2011;36:39–45. doi: 10.1159/000322512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simpson S, Jr, Taylor B, Blizzard L, Ponsonby AL, Pittas F, Tremlett H, Dwyer T, Gies P, van der Mei I. Higher 25-hydroxyvitamin d is associated with lower relapse risk in multiple sclerosis. Annals of neurology. 2010;68:193–203. doi: 10.1002/ana.22043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jagannath VA, Fedorowicz Z, Asokan GV, Robak EW, Whamond L. Vitamin d for the management of multiple sclerosis. Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2010:CD008422. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008422.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burton JM, Kimball S, Vieth R, Bar-Or A, Dosch HM, Cheung R, Gagne D, D’Souza C, Ursell M, O’Connor P. A phase i/ii dose-escalation trial of vitamin d3 and calcium in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2010;74:1852–1859. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181e1cec2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wingerchuk DM, Noseworthy JH. Randomized controlled trials to assess therapies for multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2002;58:S40–48. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.8_suppl_4.s40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, McQuay HJ. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: Is blinding necessary? Controlled clinical trials. 1996;17:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mosayebi G, Ghazavi A, Ghasami K, Jand Y, Kokhaei P. Therapeutic effect of vitamin d3 in multiple sclerosis patients. Immunological investigations. 2011;40:627–639. doi: 10.3109/08820139.2011.573041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stein MS, Liu Y, Gray OM, Baker JE, Kolbe SC, Ditchfield MR, Egan GF, Mitchell PJ, Harrison LC, Butzkueven H, Kilpatrick TJ. A randomized trial of high-dose vitamin d2 in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2011;77:1611–1618. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182343274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kampman MT, Steffensen LH, Mellgren SI, Jorgensen L. Effect of vitamin d3 supplementation on relapses, disease progression, and measures of function in persons with multiple sclerosis: Exploratory outcomes from a double-blind randomised controlled trial. Multiple sclerosis. 2012;18:1144–1151. doi: 10.1177/1352458511434607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Soilu-Hanninen M, Aivo J, Lindstrom BM, Elovaara I, Sumelahti ML, Farkkila M, Tienari P, Atula S, Sarasoja T, Herrala L, Keskinarkaus I, Kruger J, Kallio T, Rocca MA, Filippi M. A randomised, double blind, placebo controlled trial with vitamin d3 as an add on treatment to interferon beta-1b in patients with multiple sclerosis. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 2012;83:565–571. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2011-301876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shaygannejad V, Janghorbani M, Ashtari F, Dehghan H. Effects of adjunct low-dose vitamin d on relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis progression: Preliminary findings of a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Multiple sclerosis international. 2012;2012:452541. doi: 10.1155/2012/452541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aivo J, Lindsrom BM, Soilu-Hanninen M. A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial with vitamin d3 in ms: Subgroup analysis of patients with baseline disease activity despite interferon treatment. Multiple sclerosis international. 2012;2012:802796. doi: 10.1155/2012/802796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steffensen LH, Jorgensen L, Straume B, Mellgren SI, Kampman MT. Can vitamin d supplementation prevent bone loss in persons with ms? A placebo-controlled trial. Journal of neurology. 2011;258:1624–1631. doi: 10.1007/s00415-011-5980-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Simon KC, Munger KL, Kraft P, Hunter DJ, De Jager PL, Ascherio A. Genetic predictors of 25-hydroxyvitamin d levels and risk of multiple sclerosis. Journal of neurology. 2011;258:1676–1682. doi: 10.1007/s00415-011-6001-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smolders J, Hupperts R, Barkhof F, Grimaldi LM, Holmoy T, Killestein J, Rieckmann P, Schluep M, Vieth R, Hostalek U, Ghazi-Visser L, Beelke M group Ss. Efficacy of vitamin d(3) as add-on therapy in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis receiving subcutaneous interferon beta-1a: A phase ii, multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Journal of the neurological sciences. 2011;311:44–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2011.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dorr J, Ohlraun S, Skarabis H, Paul F. Efficacy of vitamin d supplementation in multiple sclerosis (evidims trial): Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2012;13:15. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-13-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]