Abstract

Cardiac amyloidosis results in severely symptomatic heart failure that has a poor prognosis because of the development of a restrictive cardiomyopathy. The diagnosis of cardiac amyloidosis is often delayed because of nonspecific signs and symptoms. We report the case of a 66-year-old woman who had been diagnosed with sick sinus syndrome and presented 5 months later with a long QT interval and recurrent polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. The diagnosis of cardiac amyloidosis was confirmed upon analysis of endomyocardial biopsy results. The patient was subsequently diagnosed with and treated for underlying plasma cell myeloma and later died of cardiac arrest. This atypical presentation of cardiac amyloidosis underscores the need to consider it in the differential diagnosis of patients who have ventricular arrhythmias. To our knowledge, the combination of long QT interval and polymorphic ventricular tachycardia has not been previously reported in association with amyloid heart disease.

Key words: Amyloidosis/complications/diagnosis/etiology; cardiomyopathies/diagnosis/therapy; diagnosis, differential; tachycardia, ventricular/etiology/therapy

Cardiac amyloidosis is an infiltrative disease that usually presents with symptoms of congestive heart failure and echocardiographic evidence of restrictive cardiomyopathy. We describe the unusual case of a woman who presented with a long QT interval (QTc), polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (VT), and implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) firings. She was ultimately diagnosed with cardiac amyloidosis.

Case Report

In May 2011, a 66-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital's coronary care unit because of recurrent shocks from her ICD. She had been in apparently excellent health until 5 months before admission, but a pacemaker had been placed in February 2011 for sick sinus syndrome. This was followed by an upgrade to a dual-chamber ICD in April 2011 after she presented at another hospital with syncope and self-limited polymorphic VT. At the time of ICD implantation, an electrocardiogram (ECG) had shown a normal QTc (437 ms) (Fig. 1A); an echocardiogram had revealed mild left ventricular hypertrophy, normal systolic function, and moderate left atrial enlargement; and angiograms had revealed no significant coronary disease.

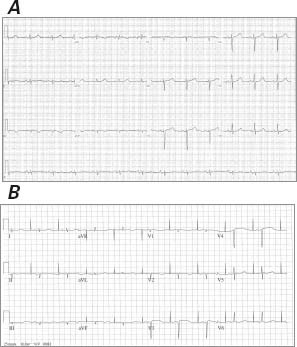

Fig. 1 A) Electrocardiogram from another hospital before cardioverter-defibrillator implantation shows sinus rhythm with a normal QT interval. B) Electrocardiogram upon the patient's admission to our hospital shows low voltage in the limb leads, a prolonged QT interval of 550 ms, and a pseudo-infarct pattern with QS waves in the anteroseptal leads.

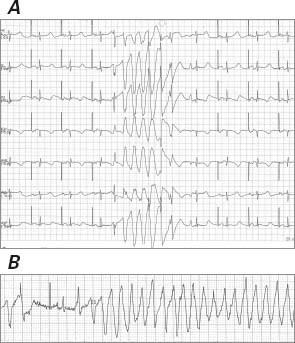

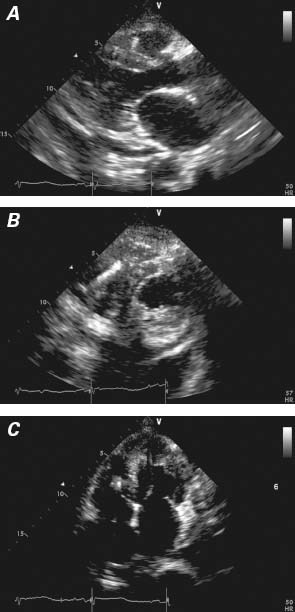

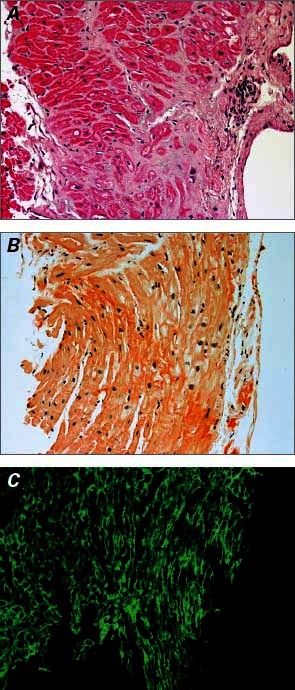

Upon arrival at our hospital, the patient was 100% paced at a base rate of 50 beats/min. Her ECG was significant for low voltages, a pseudo-infarct pattern with QS waves in the anteroseptal leads, and a markedly prolonged QTc of 550 ms (Fig. 1B), longer than on the ECG 5 months earlier at the other hospital. Device examination indicated an underlying rhythm of sinus bradycardia with high-grade atrioventricular block and junctional escape. The patient had received 8 appropriate shocks for polymorphic VT. In an effort to reduce QTc length, transient pacing at 85 beats/min was attempted; however, this was associated with frequent ectopy and paradoxically increased QTc length to over 600 ms, and it incited further polymorphic VT (Fig. 2). An echocardiogram showed a small posterior pericardial effusion, mild concentric left ventricular hypertrophy, a borderline-hyperdynamic ejection fraction, a restrictive filling pattern (E/A ratio, 3.3), and marked biatrial enlargement—findings that suggested infiltrative cardiomyopathy (Fig. 3). Urine and serum studies revealed an isolated band of electrophoretic mobility in the κ lane (serum κ immunoglobulin level, 409 mg/L; normal range, 3.3–19.4 mg/L). Fat-pad biopsy results were equivocal for amyloidosis; however, endomyocardial biopsy analysis confirmed amyloidosis infiltration on hematoxylin and eosin (Fig. 4A) and diffuse uptake of Congo red stain (Fig. 4B). Results of immunofluorescence analysis were strongly positive for κ and negative for λ protein, indicative of κ (AL) amyloidosis (Fig. 4C). A bone marrow biopsy yielded 40% to 50% plasma cells, and flow cytometry yielded 12% κ-restricted, CD38+, CD19− cells, consistent with a diagnosis of plasma cell myeloma.

Fig. 2 Electrocardiogram shows A) a QT interval of 540 ms with atrial pacing at 60 beats/min, paradoxically increasing to over 600 ms with transient pacing at 85 beats/min, associated with B) frequent ectopy and the induction of polymorphic ventricular tachycardia.

Fig. 3 Echocardiograms from the A) parasternal long-axis, B) parasternal short-axis, and C) apical 4-chamber views show a small posterior pericardial effusion, mild concentric left ventricular hypertrophy, and marked biatrial enlargement. Real-time motion image is available at www.texasheart.org/journal.

Fig. 4 Endomyocardial biopsy results. A) H & E (orig. ×20) shows extracellular deposits of pale, eosinophilic, homogeneous material consistent with amyloidosis. B) Uptake on Congo red stain (orig. ×20). C) Strongly positive light chains on immunofluorescence (orig. ×20).

Given the patient's persistent fatigue, her initial therapy with propranolol was replaced with mexilitine and was up-titrated, enabling an increase in the base pacing rate to 60 beats/min. Upon the patient's discharge from the hospital, she had no recurrent polymorphic VT, and the QTc was persistent at 504 ms. Despite oncologic treatment of AL amyloidosis and plasma cell myeloma with bortezomib and dexamethasone, progressive symptoms of heart failure developed, and she died of cardiac arrest in March 2012.

Discussion

Amyloidosis involves infiltration of the heart or other organ systems by anti-parallel β-pleated sheets of amyloid fibrils. One form of cardiac amyloidosis, the most common in developed countries, is AL (or immunoglobulin light-chain deposition) amyloidosis in patients with plasma cell myeloma, as in our patient.1 Cardiac amyloidosis should be suspected in any patient who presents with heart-failure symptoms, low ECG voltage, biatrial enlargement, and a restrictive filling pattern or ventricular hypertrophy on echocardiography. The condition is rapidly progressive and has a poor prognosis, because patients often present with nonspecific signs and symptoms that prolong the time to diagnosis. Infiltration of the conduction system increases the risk of cardiac arrhythmias—usually atrial fibrillation or heart block—and up to 30% of patients die suddenly because of pulseless electrical activity or electromechanical dissociation.2,3 Ventricular arrhythmias are an uncommon presenting feature of cardiac amyloidosis.3 Of note, our patient presented with a prolonged QTc and polymorphic VT, which raised the suspicion of an acquired or congenital long QT syndrome as a cause of her polymorphic VT and presentation. However, when it was discovered that an ECG from 5 months earlier had shown a normal QTc of 437 ms (Fig. 1B), it became evident that her syndrome was acquired. Although her prior ECGs had revealed low voltage, no clear cause had been identified, because echocardiograms had apparently shown no initial signs of restrictive or infiltrative cardiomyopathy. Therefore, her symptoms were attributed to sick sinus syndrome. The progression in QTc length with subsequent arrhythmia could have correlated with the disease's progression.

The atypical presentation of our patient, characterized by a syndrome of syncope, long QTc, and recurrent polymorphic VT, underscores the need to consider cardiac amyloidosis in patients who present with ventricular arrhythmias, especially when low voltages are seen on ECG. To our knowledge, the combination of long QT interval and polymorphic VT has not been previously reported in association with amyloid heart disease.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Address for reprints: Nisha A. Gilotra, MD, The Johns Hopkins Hospital, Carnegie 568, 600 N. Wolfe St., Baltimore, MD 21287

E-mail: naggarw2@jhmi.edu

References

- 1.Dubrey SW, Hawkins PN, Falk RH. Amyloid diseases of the heart: assessment, diagnosis, and referral. Heart 2011;97(1): 75–84. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Seethala S, Jain S, Ohori NP, Monaco S, Lacomis J, Crock F, Nemec J. Focal monomorphic ventricular tachycardia as the first manifestation of amyloid cardiomyopathy. Indian Pacing Electrophysiol J 2010;10(3):143–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Dhoble A, Khasnis A, Olomu A, Thakur R. Cardiac amyloidosis treated with an implantable cardioverter defibrillator and subcutaneous array lead system: report of a case and literature review. Clin Cardiol 2009;32(8):E63–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.