Abstract

Glu-167 of triosephosphate isomerase from Trypanosoma brucei brucei (TbbTIM) acts as the base to deprotonate substrate to form an enediolate phosphate trianion intermediate. We report that there is a large ~6 pK unit increase in the basicity of the carboxylate side chain of Glu-167 upon binding of the inhibitor phosphoglycolate trianion (I3−), an analog of the enediolate phosphate intermediate, from pKEH ≈ 4 for the protonated free enzyme EH to pKEHI ≈ 10 for the protonated enzyme-inhibitor complex EH•I3−. We propose that there is a similar increase in the basicity of this side chain when the physiological substrates are deprotonated by TbbTIM to form an enediolate phosphate trianion intermediate and that it makes an important contribution to the enzymatic rate acceleration. The affinity of wildtype TbbTIM for I3− increases 20,000-fold upon decreasing the pH from 9.3 to 4.9, because TbbTIM exists mainly in the basic form E over this pH range, while the inhibitor binds specifically to the rare protonated enzyme EH. This reflects the large increase in the basicity of the carboxylate side chain of Glu-167 upon binding of I3− to EH to give EH•I3−. The I172A mutation at TbbTIM results in an ~100-fold decrease in the affinity of TbbTIM for I3− at pH < 6, and an ~2 pK unit decrease in the basicity of the carboxylate side chain of Glu-167 at the EH•I3− complex, to pKEHI = 7.7. Therefore the hydrophobic side chain of Ile-172 plays a critical role in effecting the large increase in the basicity of the catalytic base upon the binding of substrate and/or inhibitors.

We report that the binding of phosphoglycolate trianion to triosephosphate isomerase from Trypanosoma brucei brucei (TbbTIM) results in a large > 6 unit increase in the pKa of the carboxylic acid side chain of the catalytic base Glu-167 and that the hydrophobic side chain of Ile-172 plays a critical role in effecting this increase in basicity. Brønsted acid-base catalysis by amino acid side chains makes an important contribution to enzymatic rate accelerations. This contribution will be enhanced by interactions between the catalytic side chain and bound substrate, or the interactions of catalytic side chains with one another, that lead to an increase in the thermodynamic driving force for the proton transfer, compared to proton transfer at the free side chain in water.1–3 However, it is exceedingly difficult to design experiments that provide comparisons between the pKa of an amino side chain during turnover and the corresponding pKa in water.

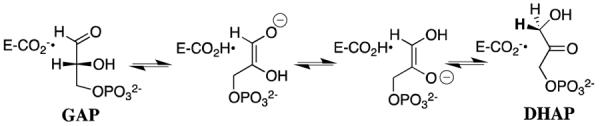

Triosephosphate isomerase (TIM) catalyzes the reversible stereospecific 1,2-hydrogen shift at dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP) to give (R)-glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate (GAP) by a single base (Glu-165 or Glu-167) proton transfer mechanism through enzyme-bound cis-enediolate reaction intermediates (Scheme 1).4–8 X-ray crystal structures of unliganded TbbTIM reveal the presence of 6 water molecules within 5 Å of the side chain of the catalytic base Glu-167.9 Closure of the flexible loop 6 of TIM over the bound substrate DHAP10,11 and transition state/intermediate analogs12–15 sequesters these ligands from interaction with bulk solvent and results in the displacement of several water molecules from the active site. For example, only two water molecules lie within 5 Å of the side chain of Glu-167 at the complex between TIM from Leishmania mexicana and phosphoglycolohydroxamate.15 An unperturbed pKa of 3.9 has been determined for the corresponding well-solvated carboxylate side chain of the catalytic base Glu-165 at yeast TIM,16 and there is a modest 1 – 2 unit increase in the pKa of this carboxylate group at the Michaelis complex with substrate.17–19 We have proposed that ligand-driven desolvation of the active site of TIM results in a large increase in the basicity of the catalytic base.5,20 We present here the results of studies that provide support for this proposal.

Scheme 1.

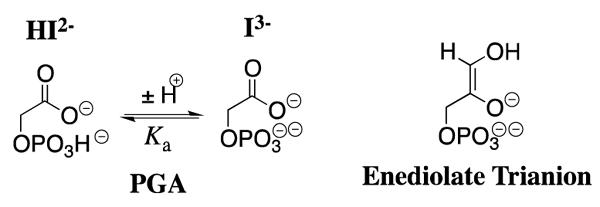

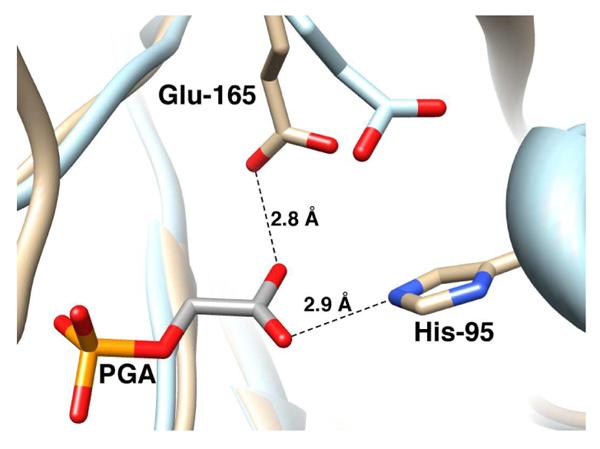

Phosphoglycolate (PGA, Chart 1) is a high-affinity competitive inhibitor of TIM and its specificity in binding to TIM is proposed to be similar to that of the enzymatic transition state.21,22 The pH profiles for competitive inhibition of yeast TIM by PGA,16 along with the results of NMR studies of the protonation state of the TIM•PGA complex,23,24 show the following: (1) PGA binds to TIM (E) as its trianion (I3−), and (2) that the binding of I3− is accompanied by the uptake of a proton by TIM to give the EH•I3− complex. X-ray crystal structures of TIM complexed with PGA (Figure 1) are consistent with the presence of a hydrogen bond between the anionic carboxylate group of PGA and the protonated side chain of Glu-165 at yeast TIM,14 or of Glu-167 at TbbTIM,12 providing strong evidence that the binding of I3− to E is accompanied by protonation of the side chain of the catalytic base. Presumably the combination of the relief of destabilizing electrostatic interactions between the neighboring carboxylate anions of TIM B and I3−, and the formation of an enzyme-inhibitor hydrogen bond, are responsible for the large driving force for protonation of the side chain of the catalytic glutamate at the E•I3− complex to give EH•I3−.25

Chart 1.

Figure 1.

Models, from X ray crystal structures, of the active site of unliganded yeast TIM (light blue, PDB entry 1YPI) and yeast TIM complexed with PGA (tan, PDB entry 2YPI). Ligand binding is accompanied by a 2 Å shift in the position of the carboxylate side chain of Glu-165 towards the bound ligand. The active sites of TIM from yeast and Trypanosoma brucei brucei are virtually superimposable, except that the catalytic base at TbbTIM is at position 167 in the protein sequence.

Wildtype TbbTIM and the I172A and L232A mutants were prepared as described in our earlier work.26–28 Initial velocities, vi (M s−1), for the enzyme-catalyzed isomerization of GAP in the absence and presence of various concentrations of PGA at pH 4.9 – 9.3, 25 °C and I = 0.1 (NaCl) were determined as described in the Supporting Information. The data obtained at each pH were globally fit to eq 1 to give the values of kcat, Km and (Ki)obs that are reported in Tables S1 and S2 of the Supporting Information, where (Ki)obs is the observed inhibition constant determined for total PGA (I3− + HI2−) at the pH of interest. The values of kcat for both wildtype and I172A mutant TbbTIM are pH-independent between pH 5.7 and 9.3 (Table S1). The pH-rate profiles for kcat/Km for both wildtype and I172A mutant TbbTIM (not shown) exhibit a downward break at pH 6.1, corresponding to the second ionization of the phosphoryl group of the substrate.17–19 It has been shown that TIM binds and turns over the phosphoryl dianion form of the substrate.19

| (1) |

The values of (Ki)obs determined here for competitive inhibition of wildtype TbbTIM by total PGA at I = 0.1 (NaCl) are similar to those reported previously for yeast TIM over a more narrow range of pH at I = 0.05 (KCl), when the difference in the ionic strength is taken into account.16 The values of (Ki)obs for inhibition of both wildtype and I172A mutant TbbTIM approach a constant value at low pH, where the inhibitor exists mainly as its dianion HI2− (Table S2). The downward break in the plots of p(Ki)obs against pH (Figure S1 of the Supporting Information) corresponds to pKa = 6.3 for ionization of HI2− to form I3− at I = 0.1 (Chart 1), which is similar to the pKa of 6.5 at I = 0.05 reported previously.16 As discussed above, PGA binds as the trianion I3− to the protonated enzyme EH resulting in formation of the EH•I3− complex (Scheme 2).23,24 Therefore, true values of Ki for inhibition of the wildtype and mutant TbbTIMs by the PGA trianion I3− at each pH (Table S2) were calculated from the observed values using eq 2, with pKa = 6.3 for ionization of HI2− to give I3-−.

Scheme 2.

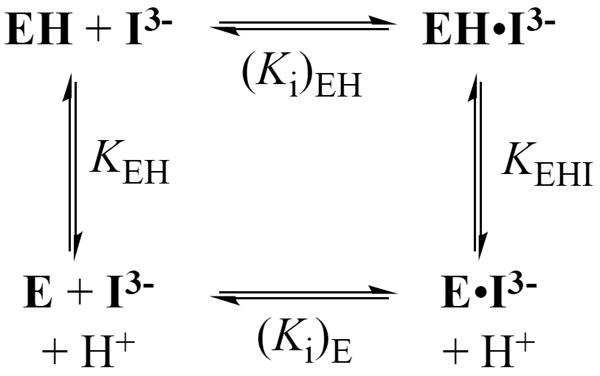

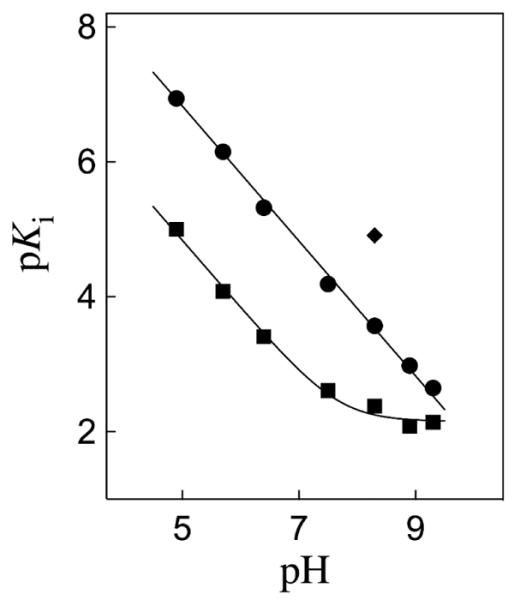

Figure 2 shows the pH profiles for competitive inhibition of wildtype and I172A mutant TbbTIM by I3−, along with the value of Ki = 1.2 × 10−5 M determined for inhibition of the L232A mutant at pH 8.3. The solid line through the data for the wildtype enzyme, which has a slope of −1.0, was obtained from the fit of the data to eq 3, derived for Scheme 2, with KEH >> [H+] and KEHI << [H+]. There is a 20,000 fold decrease in Ki on decreasing the pH from 9.3 to 4.9 and the absence of breaks in the pH profile shows that unliganded wildtype TbbTIM exists mainly as E at pH 4.9 (pKEH < 4.9), while the E•PGA complex exists mainly as EH•I3− at pH 9.3 (pKEHI > 9.3). The data for the I172A mutant were fit to eq 3, with KEH >> [H+], to give pKEHI = 7.7 for ionization of the EH•I3− complex. Therefore, the I172A mutation results in a substantial decrease in pKEHI compared to that for wildtype TbbTIM.

| (2) |

| (3) |

Figure 2.

Dependence on pH of the dissociation constant Ki (M) for breakdown of the complex between I3− and wildtype TbbTIM (●), I172A mutant TbbTIM (■), and L232A mutant TbbTIM (◆) at 25 °C and I = 0.1 (NaCl).

The I172A mutation at TbbTIM results in a 100-fold decrease in kcat/Km for substrate isomerization (Table S1),28 which is similar to the 100-fold lower affinity of the mutant compared with the wildtype enzyme for I3− observed at pH < 6 (Figure 2). Now, if the effect of the I172A mutation on the binding of PGA results from a perturbation of the basicity of Glu-167 at the EH•I3− complex, so that there is a larger thermodynamic driving force for protonation of the E•I3− complex to give EH•I3− for the wildtype enzyme, then the 100-fold higher affinity of the wildtype enzyme for I3− is consistent with pKEHI ≈ 10 for ionization of Glu-167 at the wildtype EH•I3− complex. The catalytic properties of TbbTIM are similar to those of TIMs from other organisms,18,26 so that the value of pKEH = 3.9 determined for the side chain of Glu-165 at unliganded wildtype yeast TIM16 is expected to be similar to that of Glu-167 at unliganded wildtype TbbTIM. Therefore, we conclude that the binding of I3− to wildtype TbbTIM results in an ~6 pK unit increase in the basicity of the carboxylate side chain of the catalytic base Glu-167, from pKEH ≈ 4 for the free enzyme,16 to pKEHI ≈ 10 for the EH•I3− complex. We attribute the large increase in the thermodynamic driving force for protonation of the side chain of the catalytic glutamate at the E•I3− complex to give EH•I3− to the combined effects of the relief of destabilizing electrostatic interactions between the neighboring carboxylate anions of TIM and I3− and the formation of a stabilizing enzyme-inhibitor hydrogen bond.25

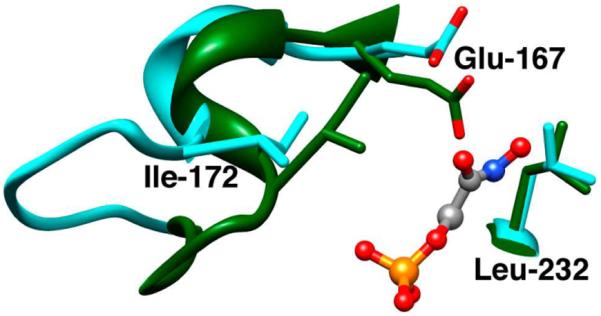

The closure of loop 6 of TIM over bound ligands is accompanied by movement of the hydrophobic side chain of Ile-172 towards the carboxylate side chain of Glu-167, as the latter side chain swings towards the ligand and the hydrophobic side chain of Leu-232 (Figure 3).12 This large conformational change converts the inactive open enzyme EO to the active closed enzyme EC and serves to sequester the catalytic base from interaction with bulk solvent. It results in “clamping” of the carboxylate anion of Glu-167 between the bulky hydrophobic side chains of Ile-172 and Leu-232. The L232A mutation at TbbTIM results in a surprising 20-fold increase in the second-order rate constant for enzyme-catalyzed deprotonation of the truncated substrate glycolaldedyde.27,28 The observation here that the L232A mutation also results in a 20-fold increase in the affinity of the enzyme for I3− at pH 8.3 (Figure 2) is consistent with the proposal that this mutation results in an ~20-fold increase in the concentration of the closed enzyme EC relative to the open enzyme EO, and that the intermediate analog I3− has a high affinity for the closed enzyme EC, but a much lower affinity for the open enzyme EO.27,28

Figure 3.

Models, from X-ray crystal structures, of the active sites of unliganded TbbTIM in the open form (cyan, PDB entry 5TIM) and the closed enzyme liganded by phosphoglycolohydroxamate (green, PDB entry 1TRD). Closure of loop 6 (residues 168 – 178) over bound ligand results in movement of the side chain of Ile-172 towards the side chain of Glu-167 and of this carboxylate side chain towards the side chain of Leu-232.

We propose that the ~2 pK unit higher pKa of the carboxylate group of Glu-167 at the EH•I3− complex for wildtype compared with I172A mutant TbbTIM results from the “clamping” action of the side chain of Ile-172 that leads to destabilization of E•I3− by unfavorable electrostatic interactions between the neighboring carboxylate anions of Glu-167 and bound I3−, and stabilization of EH•I3− by the formation of a hydrogen bond between the carboxylate group of I3− and the protonated side chain of Glu-165/167 (Figure 1). Thus the bulky hydrophobic side chain of Ile-172 restricts the movement of the basic carboxylate side chain of Glu-167 relative to I3− at E•I3−, resulting in an increase in the driving force for protonation to give EH•I3−. The I172A mutation then lifts this restriction, allowing separation of the carboxylate anions of the enzyme and bound I3− and relief of the destabilizing electrostatic interactions (Figures 1 and 3).

The binding to TIM of the enediolate phosphate trianion intermediate of the isomerization reaction (Scheme 1) should result in an increase in the basicity of the carboxylate side chain of Glu-165/167 that is similar to that observed upon the binding of the intermediate analog I3−, because each complex is destabilized by electrostatic interactions between a ligand trianion and an enzyme carboxylate oxyanion that are relieved by protonation of the enzyme. The increase in the pKa of Glu-165/167 will occur as the α-carbonyl proton is transferred from substrate to Glu-165/167, so that the maximal change in the basicity of this residue will occur upon full proton transfer to form the TIM•enediolate complex.2 This enhancement of the basicity of the catalytic base at TIM results in an increase in the thermodynamic driving force for deprotonation of enzyme bound substrate compared to the driving force in water, and will make a significant contribution to the enzymatic rate acceleration.

PGA trianion is a less than perfect transition state/intermediate analog. For example, the EH•I3− complex is stabilized by a hydrogen bond between the protonated side chain of Glu-165/167 and I3− (Figure 1), but this hydrogen bond cannot be present in the transition state for deprotonation of TIM-bound substrate, where the carboxylate anion is in the process of abstracting a substrate proton. Also, the transition state is strongly stabilized by the presence of a hydrogen bond between the imidazole side chain of His-95 and the developing C-1 or C-2 oxyanion (Figure 1).29,30 If the strength of the hydrogen bond between His-95 and the carboxylate of I3− at the EH•I3− complex is attenuated by the presence of the additional hydrogen bond between I3− and the carboxylic acid side chain of Glu-165/167 (Figure 1), then the interaction with His-95 may be less significant for stabilization of the EH•I3− complex than for transition state stabilization.

At pH 4.9, where Ki = 1.2 × 10−7 M for wildtype TbbTIM (Table S2), only ~10% of the enzyme is expected to be present in the protonated EH form (pKEH ≈ 4, Scheme 2). This is consistent with (Ki)EH ≈ 1.2 × 10−8 M for breakdown of the EH•I3− complex at pH << 4, where the side chain of Glu-167 at the free enzyme is fully protonated, which corresponds to a binding energy of 11 kcal/mol for formation of EH•I3− from EH + I3− (Scheme 2). This binding energy is only ~3 kcal/mol smaller than the total intrinsic transition state binding energy of 14 kcal/mol estimated for the natural substrate GAP.31,32 We conclude that the stabilizing electrostatic interactions between TIM and the small two-carbon transition state/intermediate analog I3− account for a very large fraction of the total transition state stabilization for the TIM-catalyzed reaction.

In conclusion, PGA trianion is a good transition state analog that expresses ~80% of the total intrinsic transition state binding energy for TIM. The binding of PGA trianion at the desolvated enzyme active site results in destabilizing electrostatic interactions of its carboxylate group with the carboxylate side chain of Glu-165/167 and results in a substantial enhancement of the basicity of this catalytic base, which functions to deprotonate enzyme bound substrate.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by Grant GM39754 from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Supporting Information. Experimental procedures for determination of the kinetic parameters for isomerization of GAP and for competitive inhibition by phosphoglycolate. Values of kcat and kcat/Km for isomerization of GAP, and (Ki)obs for inhibition by phosphoglycolate, for wildtype and I172A mutant TbbTIM (Tables S1 and S2). Dependence on pH of (Ki)obs for wildtype and I172A mutant TbbTIM (Figure S1). Michaelis-Menten plots of initial velocities for isomerization of GAP by wildtype and I172A mutant TbbTIM in the absence and presence of phosphoglycolate (Figures S2 and S3). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- (1).Richard JP, Huber RE, Heo C, Amyes TL, Lin S. Biochemistry. 1996;35:12387–12401. doi: 10.1021/bi961029b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Richard JP. Biochemistry. 1998;37:4305–4309. doi: 10.1021/bi972655r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).McIntosh LP, Hand G, Johnson PE, Joshi MD, Korner M, Plesniak LA, Ziser L, Wakarchuk WW, Withers SG. Biochemistry. 1996;35:9958–9966. doi: 10.1021/bi9613234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Rieder SV, Rose IA. J. Biol. Chem. 1959;234:1007–1010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Richard JP. Biochemistry. 2012;51:2652–2661. doi: 10.1021/bi300195b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Knowles JR, Albery WJ. Acc. Chem. Res. 1977;10:105–111. [Google Scholar]

- (7).O'Donoghue AC, Amyes TL, Richard JP. Biochemistry. 2005;44:2610–2621. doi: 10.1021/bi047954c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).O'Donoghue AC, Amyes TL, Richard JP. Biochemistry. 2005;44:2622–2631. doi: 10.1021/bi047953k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Wierenga RK, Noble MEM, Vriend G, Nauche S, Hol WGJ. J. Mol. Biol. 1991;220:995–1015. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90368-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Petsko GA, Davenport RC, Jr., Frankel D, RaiBhandary UL. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 1984;12:229–232. doi: 10.1042/bst0120229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Jogl G, Rozovsky S, McDermott AE, Tong L. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100:50–55. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0233793100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Kursula I, Wierenga RK. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:9544–9551. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211389200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Davenport RC, Bash PA, Seaton BA, Karplus M, Petsko GA, Ringe D. Biochemistry. 1991;30:5821–5826. doi: 10.1021/bi00238a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Lolis E, Petsko GA. Biochemistry. 1990;29:6619–6625. doi: 10.1021/bi00480a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Alahuhta M, Wierenga RK. Proteins: Struct., Funct., Bioinf. 2010;78:1878–1888. doi: 10.1002/prot.22701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Hartman FC, LaMuraglia GM, Tomozawa Y, Wolfenden R. Biochemistry. 1975;14:5274–5279. doi: 10.1021/bi00695a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Plaut B, Knowles JR. Biochem. J. 1972;129:311–320. doi: 10.1042/bj1290311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Lambeir AM, Opperdoes FR, Wierenga RK. Eur. J. Biochem. 1987;168:69–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1987.tb13388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Belasco JG, Herlihy JM, Knowles JR. Biochemistry. 1978;17:2971–2978. doi: 10.1021/bi00608a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Malabanan MM, Amyes TL, Richard JP. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2010;20:702–710. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2010.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Wolfenden R. Acc. Chem. Res. 1972;5:10–18. [Google Scholar]

- (22).Wolfenden R. Nature. 1969;223:704–705. doi: 10.1038/223704a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Campbell ID, Jones RB, Kiener PA, Richards E, Waley SC, Wolfenden R. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1978;83:347–352. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(78)90438-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Campbell ID, Jones RB, Kiener P, Waley SG. Biochem. J. 1979;179:607–621. doi: 10.1042/bj1790607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Hine J. Structural Effects on Equilibria in Organic Chemistry. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- (26).Malabanan MM, Go M, Amyes TL, Richard JP. Biochemistry. 2011;50:5767–5679. doi: 10.1021/bi2005416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Malabanan MM, Amyes TL, Richard JP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:16428–16431. doi: 10.1021/ja208019p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Malabanan MM, Koudelka AP, Amyes TL, Richard JP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:10286–10298. doi: 10.1021/ja303695u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Komives EA, Chang LC, Lolis E, Tilton RF, Petsko GA, Knowles JR. Biochemistry. 1991;30:3011–3019. doi: 10.1021/bi00226a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Nickbarg EB, Davenport RC, Petsko GA, Knowles JR. Biochemistry. 1988;27:5948–5960. doi: 10.1021/bi00416a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Amyes TL, O'Donoghue AC, Richard JP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:11325–11326. doi: 10.1021/ja016754a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Richard JP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984;106:4926–4936. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.