Abstract

The current study compares the effects of traditional and modern anti-homosexual prejudice on evaluations of parenting practices of same-sex and opposite-sex couples. Undergraduate university student participants (N = 436) completed measures of traditional and modern anti-homosexual prejudice and responded to a vignette describing a restaurant scene in which parents react to their child’s undesirable behavior. The parents’ sexual orientation and the quality of their parenting (positive or negative quality) were varied randomly. It was predicted that participants who score higher in modern prejudice would rate the negative parenting behaviors of same-sex parents more negatively than similar behaviors in opposite-sex parents. It was also predicted that this modern prejudice effect would be most pronounced for male participants. Both hypotheses were supported.

Keywords: Attitudes, heterosexism, modern prejudice, same-sex parenting, vignettes

Introduction

“My partner and I [two women] were attending a parent teacher conference, and my son (he’s 6), his home room teacher kept suggesting that strong male role models in his life might help with his recent behavioral problems.” – a lesbian mom

“When my boys run wild in the grocery store, I keep wondering if people notice that we’re a gay couple.” – a gay dad

At the 2011 LGBTQ Families Conference in Rochester, New York, a group of lesbian, gay, and bisexual parents came together to discuss the challenges their families confront when they are interacting as same-sex parents in a public setting. This “public parenting” discussion led to a number of examples on the part of the participants (two examples are provided above). Many participants felt there were few differences between their family and the heterosexual families they knew, and that the interactions they had with their children’s teachers, pediatricians, and other parents, were often without incident. If something did go wrong during any of these interactions, it was understood as something that could have happened to any family, regardless of the parents’ sexual orientation. In some cases, however, these parents encountered situations in which a question was asked or a decision was made that suggested others’ attitudes toward them as gay-, lesbian-, or bisexual-headed families were less favorable, and potentially due to anti-gay anti-lesbian bias.

This process of sorting through ambiguous attributions (Crocker & Major, 1989) and deciding what is and is not prejudice has been described as a kind of microaggression (Massey, 2007; Sue et al., 2007). Such microaggressions have been found to take a psychological toll on their victims, including increased self-doubt, frustration, isolation, and emotional turmoil (Chakraborty & McKenzie, 2002; Clark, Anderson, Clark, & Williams, 1999; Solo’rzano et al., 2000; Steele, Spencer, & Aronson, 2002). The aggressed are often left to sort out whether an aggression has actually occurred, what an appropriate response might be, and while weighing up the consequences of taking action or suppressing their frustration.

One aspect of these stories that we wish to further explore is the relationship between overt and subtle manifestations of anti-gay anti-lesbian prejudice. Specifically, the current study examines how anti-homosexual prejudice affects the evaluations of the parenting practices of gay and lesbian parents as compared to heterosexual parents.

Same-Sex Headed Households

The number of same-sex headed households in the United States has grown steadily over the past 20 years. The 2010 U.S. Census puts the number of same-sex couples who are living together at 646,464 (131,729 same-sex married couple households and 514,735 same-sex unmarried couple households). According to the 2000 U.S. Census approximately 163,879 households with children were headed by same-sex couples (Paige, 2005). Lesbian and bisexual women were more likely to be parents than gay or bisexual men, with 33% of female same-sex couple households and 22% of male same-sex couple households reported having a child under the age of 18 living with them (Gates, 2011; Paige, 2005). According to results from the 2008 general social survey, 19% of gay and bisexual men and 49% of lesbians and bisexual women are parents to children (Gates, 2011).

As the number of same-sex couples and, as a result, same-sex parenting overall has increased, attitudes toward same-sex parenting have improved. From 2007 to 2011, public condemnation of same-sex parenting in the U.S. dropped from 50% to 35%, while acceptance has remained relatively stable (Pew Research Center, 2011). Attitudes, however, reflect a strong partisan bias, with 53% of Republicans still saying same-sex parenting is bad for society while only 28% of Democrats expressed these same negative attitudes. To complicate matters more, Gates (2011) found that the percentage of same-sex couples raising children was higher in more conservative parts of the country. This complex array of factors impacting attitudes toward same-sex parents have resulted in a confusing landscape of limitations and prohibitions, as well as protections and anti-discrimination laws related to same-sex parenting.

Attitudes toward Same-Sex Parenting

A large body of psychometric research on anti-homosexual prejudice has developed over the past 50+ years (see Massey, 2009). Since the 1970s, questions about same-sex parenting have been included in many of the measures of anti-homosexual prejudice (e.g., Herek, 1984; MacDonald, Huggins, Young, & Swanson, 1973). These scales have included items such as “homosexuals should not be allowed to raise children” and “male homosexual couples should be allowed to adopt children the same as heterosexual couples”. However, these measures primarily have assessed approval or disapproval, and have not included evaluations of actual parenting behaviors or skills (c.f., Massey, 2007).

Only recently have researchers begun focusing on how anti-homosexual attitudes might affect evaluations of the quality of same-sex parenting. Meanwhile, another body of literature has focused on dispelling the myths about the negative effects of same-sex parenting on children (Patterson, 2009).

In a special issue of Journal of GLBT Family Studies focusing on the future directions of same-sex parenting research, Morse, McLaren, and McLachlan (2007) used vignettes to explore attitudes toward same-sex parenting among Australian heterosexuals. The vignettes used described a family situation in which the sexual orientation of the parents varied. The researchers found that overall participants believed that, compared to heterosexual parents, gay and lesbian parents were less emotionally stable, responsible, competent, sensitive, and nurturing parents. In addition, participants’ levels of anti-homosexual prejudice were a strong predictor of believing that same-sex parenting was tied to more negative outcomes (Morse, McLaren, & McLachlan, 2007).

In the same volume, Massey (2007) reported similar results among U.S. participants. In this study participants responded to a vignette describing a scene at a restaurant in which a 4-year-old boy misbehaved and one of his two parents intervenes. The sexual orientation of the parents and the gender of the intervening parent were randomly assigned and participants were asked to evaluate the parenting skills of the intervening parent. Higher levels of traditional heterosexism predicted more negative evaluations of gay and lesbian parents. In addition, modern anti-homosexual prejudice (Massey, 2009), measured as the denial of the existence of anti-gay anti-lesbian discrimination, predicted more negative evaluations. It was suggested that future research should explore the effect of modern anti-homosexual prejudice in parenting situations in which the appropriateness of the parenting behaviors was more ambiguous (Massey, 2007)

Modern Prejudice and Anti-Gay Anti-Lesbian Attitudes

The modern prejudice framework, introduced in late 1980s and originally applied to race (McConahay, 1986; Sears, 1988), has suggested that as people become less willing to overtly display racial prejudice, this prejudice goes “underground” and to be expressed in more subtle, indirect, ways. Pearson, Dovidio, and Gaertner (2009) have explained that these new forms of racism can be seen in white people who express egalitarian views and who actually regard themselves as not being prejudiced. However, in ambiguous situations, where negative attitudes can be attributed to a non-prejudiced cause, these same people were more likely to discriminate. These subtle forms of prejudice have been found to influence hiring decisions, college admissions decisions, helping behavior, and legal decisions (see Pearson, Dovidio, & Gaertner, 2009). Recent research has extended the idea of modern prejudice beyond race, to include gender and sexual minorities (Anderson & Kanner, 2011; LaMar & Kite, 1998; Massey, 2009; Raja & Stokes, 1998).

Massey (2009) introduced a multidimensional measure that included a modern anti-homosexual prejudice scale. This measure has included subscales for both traditional “old fashioned” heterosexism and modern anti-homosexual prejudice. Modern anti-homosexual prejudice was assessed using items that revealed participants’ likelihood to deny that anti-homosexual discrimination was still a problem in society. This Denial of Discrimination measure was found to correlate modestly (r=.45) with Traditional Heterosexism, with men reporting higher levels of both traditional and modern prejudice than women. In addition, modern anti-gay anti-lesbian prejudice was found to be a stronger predictor of negative evaluations of same-sex parenting than was traditional heterosexism (Massey, 2007).

Current Study

The current study aimed to explore the impact of modern prejudice on evaluations of same-sex parents. Results from the modern racism literature suggest that although overt prejudice may have diminished or become more subtle, it has not disappeared altogether (Gaertner & Dovidio,1986; Katz & Hass, 1988; McConahay, 1986; Sears, 1988). In ambiguous situations, or situations in which an alternative explanation for negative judgment can be found, people will express their prejudice. The current study has built upon the same-sex parenting vignettes of previous research (Massey, 2007; Morse, McLaren, & McLachlan, 2007), but has provided both positive and negative parenting scenarios. By varying the sexual orientation and gender of parents, as well as the relative positive/negative parenting scenario, the effects of persistent but subtle modern prejudice can be assessed. Although traditional anti-gay anti-lesbian attitudes were not expected to have vanished altogether, it was believed that modern prejudice would also have an impact on heterosexual participants’ responses to scenarios involving same-sex couples.

Hypothesis 1

Past research on anti-homosexual prejudice has suggested that gay and lesbian parents will be evaluated more negatively than heterosexual parents (Massey, 2007). Consistent with these findings, participants with higher levels of traditional (“old-fashioned”) anti-homosexual prejudice are expected to evaluate same-sex parents more negatively than opposite sex parents. This difference was not expected for those with lower levels of traditional anti-homosexual prejudice.

Hypothesis 2

Although overt, traditional, anti-homosexual prejudice may be declining, it has been demonstrated that it is not disappearing altogether, and is instead becoming more subtle, manifesting in situations where it can be attributed to a non-prejudiced cause. The second hypothesis, therefore, was that modern anti-homosexual prejudice will moderate the evaluation of the parenting practices of same-sex parents relative to opposite sex parents, but only in negative parenting situations, where doing so would not suggest overtly anti-gay anti-lesbian attitudes. When evaluating identical negative parenting behaviors, the behaviors of same-sex parents will be viewed as more negative than those of opposite-sex parents. Modern anti-homosexual prejudice will not be expected to have an impact on participants’ evaluations of positive parenting behaviors.

Hypothesis 3

A robust literature has demonstrated that men have consistently more negative attitudes toward homosexuality than do women (Herek, 2000; Kite & Whitley, 1996; Ratcliff, Lassiter, Markman, & Snyder, 2006). This gender difference also has been found in modern forms of anti-homosexual prejudice (Massey, 2009). Our third hypothesis, therefore, was that participant gender will interact with modern anti-homosexual prejudice and its effect on evaluations of negative parenting behaviors. Male participants who are high in modern anti-homosexual prejudice are expected to evaluate the negative parenting behaviors of same-sex couples more negatively than similar behaviors in opposite-sex couples. Modern anti-homosexual prejudice will not be expected to have an effect on female participants’ evaluations of negative parenting behaviors, and participant gender is not expected to interact with modern anti-homosexual prejudice in evaluations of positive parenting behaviors.

Methods

Participants

Participants were undergraduate students attending a mid-sized state university in northeastern United States. Participants were recruited through the Department of Psychology human subject pool, as well as other introductory survey courses. Participants received course credit for their participation. Because this study explored heterosexuals’ attitudes toward same-sex parents, only participants who identified as heterosexual were included in the analyses. Cases with incomplete or missing data were removed from the current sample.

Four hundred thirty-six (436) participants completed the online survey (36.7% male and 63.0% female). Ninety-three percent (94.7%) of participants were between 18-21 years old, 4.8% between 22-25, and only .2% between 31-40. Participants identified as White (71.4%), Asian/Pacific Islander (19.2%), African American (4.6%), Caribbean American (4.8%). Fourteen percent (13.8%) identified as Latino.

Questionnaire

The questionnaire was administered electronically via Qualtrics (www.qualtrics.com), a web-based survey provider. The questionnaire consisted of sociodemographic questions, several attitude measures, and participants’ evaluations of parenting practices after reading a parenting vignette. Potential participants were notified that the study was completely anonymous and that they could skip any question(s) they did not wish to answer. To protect potential participants and maintain complete anonymity, no identifying information was collected. All aspects of the current study were approved by a university institutional review board.

Attitudes toward gay men and lesbian women

Two subscales were taken from Massey’s (2009) multidimensional measure of heterosexuals’ attitudes toward lesbian women and gay men. The first, traditional heterosexism was adapted from Herek (1984). This scale assesses overt, traditional (or “old-fashioned”) anti-gay anti-lesbian attitudes that claim that homosexuality is immoral, unnatural, and perverted and that, therefore, certain rights and privileges can and should be denied to homosexuals. This measure includes items such as: “female homosexuality is a sin”, “homosexuality is just as moral a way of life as heterosexuality”, and “it is important for gay and lesbian people to be true to their feelings and desires.” The second measure, denial of discrimination was modeled after McConahay’s (1986) measure of modern or subtle racism. This scale assesses a more subtle and modern form of anti-homosexual prejudice that is demonstrated through the denial of ongoing discrimination, the belief that gay people and straight people have equal opportunities for advancement and that gay people’s complaints about discrimination are unwarranted. This measure includes items such as: “on average people in our society treat gay people and straight people equally”, “most lesbians and gay men are no longer discriminated against”, and “discrimination against gay men and lesbians is no longer a problem in the United States”.

Responses on both subscales were measured on a 5-point Likert scale, from 1=strongly disagree to 5=strongly agree. Both scales were found to be both reliable (Traditional Heterosexism, alpha=.93; Denial of Discrimination, alpha=.87) and valid.

Parenting vignettes

Each participant was presented with a vignette (see Appendix A). Participants were asked to read the vignette, and then evaluate the quality of parenting. The presentation of vignettes was randomized to prevent any survey ordering effects.

Of the 4 vignettes in each category, the sex of the adult parents in the vignette was randomized. Vignettes either had two men (Steve and Mark), two women (Beth and Mary), or a man and a woman (Steve and Beth). In the case of opposite-sex parents (Steve and Beth), the role of active parent was varied. This results in a total of 8 vignettes created, with 4 vignette types for each of the 2 thematic story lines (positive context or negative context): same-sex male parents, where one male responds to the child; same-sex female parents, where one female responds to the child; opposite-sex parents, where the male responds to the child; opposite-sex parents, where the female responds to the child.

Two vignettes were created, one illustrating a positive parenting situation and the other a negative parenting situation (see Appendix A). The positive parenting vignette was adapted from an earlier study by Massey (2007). In the positive vignette, a family of two adults and a child are eating at a restaurant. During the meal the child gets upset and one of the parents responds by calmly engaging with the child. The child eventually calms down and continues eating. An additional, negative, parenting vignette was created for this study. In the negative vignette, a similar situation is described - two parents and a child are eating at a restaurant. The child gets upset and one of the parents responds. In this negative scenario, however, the parent who engages with the child gets frustrated and eventually angrily strikes the child on the hand. The scene resolves similarly to the positive vignette with the child eventually calming down and eating.

In both the positive and negative scenarios, the gender of the (active) parent who interacts with the child and the sexual orientation of the couple are varied while the rest of the story remains constant. Three variables - parenting behavior (positive/negative), gender of active parent (male/female), and sexual orientation of parents (heterosexual/homosexual) result in a total of 8 possible vignettes.

Parenting evaluation questions

Participants completed a panel of questions (adapted from Massey, 2007) evaluating the quality of parenting demonstrated in the vignettes: “How would you rate [Mark]’s parenting skills?”, “How well did [Mark] handle the situation?”, and “How appropriate is [Mark]’s response to the child’s behavior?”. The name of the actor in the question matched the name used in the randomized vignette. Responses were measured on a 7-point Likert scale (alpha=.80), and ranged from 1=very unskilled/inappropriate/badly to 7=very skilled/appropriate/well.

Results

Participants were randomly assigned to one of eight possible vignettes (positive/negative parenting, same-sex/opposite-sex couple, and male/female active parent. As shown in Table 1, random assignment and missing data correction resulted in between 50 (11.5%) and 59 (13.5%) cases for each vignette condition.

TABLE 1.

Frequencies for Vignette Conditions

| Vignette Condition | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| NEGATIVE - GAY - MAN | 58 | 13.3 |

| NEGATIVE - LESBIAN - WOMAN | 50 | 11.5 |

| NEGATIVE - STRAIGHT - WOMAN | 58 | 13.3 |

| NEGATIVE - STRAIGHT - MAN | 59 | 13.5 |

| POSITIVE - GAY - MAN | 50 | 11.5 |

| POSITIVE - LESBIAN - WOMAN | 58 | 13.3 |

| POSITIVE - STRAIGHT - WOMAN | 50 | 11.5 |

| POSITIVE - STRAIGHT - MAN | 53 | 12.2 |

| Total | 436 | 100 |

Traditional heterosexism, denial of discrimination, and overall parenting evaluation measures were calculated by averaging the corresponding items after adjusting for those that required reverse coding. As shown in Table 2, all measures were found to be internally consistent.

TABLE 2.

Descriptives for Independent and Dependent Variables

| N | M | SD | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parenting Evaluation | 434 | 3.84 | 1.59 | .932 |

| Traditional Heterosexism | 414 | 1.89 | 0.90 | .960 |

| Denial of Discrimination | 423 | 2.12 | 0.66 | .833 |

Note: Parenting Evaluation ranges from 1=bad to 7=good; Traditional Heterosexism and Denial of Discrimination both range from 1=low to 5=high.

As shown in Table 3, higher levels of traditional heterosexism were moderately correlated with higher levels of denial of discrimination. In addition, a small and negative correlation was found between traditional heterosexism and overall parenting evaluation of same-sex couples across parenting condition. As traditional heterosexism increased, evaluations of the parenting of same-sex couples decreased. No correlation was found between denial of discrimination and overall parenting evaluation of same-sex couples.

TABLE 3.

Correlations Among Measures for Same-Sex Parents Condition

| Measure | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Parenting Evaluation | -- | −.157* | −0.111 | |

| 2. Traditional Heterosexism | -- | .530** | ||

| 3. Denial of Discrimination | -- |

Note:

p < .05;

p < .01.

Traditional Heterosexism (Old-Fashioned Prejudice)

Hypothesis 1 predicted that higher levels of traditional heterosexism would result in more negative evaluations of same-sex couples in both positive and negative parenting conditions. In order to compare those higher and lower in traditional heterosexism, a variable was created using a mean split of traditional heterosexism (M = 1.89, SD = 0.90). A three-way univariate ANOVA was conducted to investigate differences in overall parenting evaluation for parenting condition, sexual orientation of couple, and levels of traditional heterosexsim.

In order to test hypothesis 1, it was necessary to first determine whether the experimental manipulation of positive and negative parenting condition had an effect on the parenting evaluation. As shown in Table 4, the ANOVA revealed a main effect for parenting condition F(1, 404) = 174.85, p < .001, indicating the manipulation was indeed successful. In addition, the main effect for traditional heterosexism was also significant F(1, 404) = 5.87, p < .016, supporting hypothesis 1. No main effect was found for sexual orientation of the couple.

TABLE 4.

Three-Way Univariate ANOVA for Overall Parenting Evaluation by Parenting Condition, Traditional Heterosexism and Sexual Orientation of Parents.

| Source | Df | F | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| (A) Parenting Condition | 1 | 174.85 | .001 |

| (B) Traditional Heterosexism | 1 | 5.87 | .016 |

| (C) Sexual Orientation of Parents | 1 | 0.79 | .376 |

| A × B × C (interaction) | 1 | 1.39 | .239 |

| Error (within group) | 404 |

Denial of Discrimination (Modern Anti-Homosexual Prejudice)

Hypothesis 2 predicted that modern anti-homosexual prejudice – assessed using the denial of discrimination scale – would moderate the relationship between the sexual orientation of the couple, parenting condition, and evaluation of parenting. Although higher levels of denial of discrimination were not expected to negatively affect the evaluation of same-sex parents in the positive parenting condition, they were expected to do so in the negative parenting condition. Similar to the analysis for Traditional Heterosexism, a variable was created using a mean split of denial discrimination (M = 2.12, SD = .658). Three-way univariate ANOVA was conducted to investigate differences in overall parenting evaluation for parenting condition, sexual orientation of couple, and levels of modern anti-homosexual prejudice (see Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Three-way Univariate ANOVA for Overall Parenting Evaluation by Parenting Condition, Denial of Discrimination and Sexual Orientation of Parents.

| Source | Df | F | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| (A) Parenting Condition | 1 | 195.05 | .001 |

| (B) Denial of Discrimination | 1 | 1.49 | .223 |

| (C) Sexual Orientation of Parents | 1 | 1.35 | .246 |

| A × B × C (interaction) | 1 | 4.22 | .040 |

| Error (within group) | 414 |

As shown in Table 5, the ANOVA assessing denial of discrimination revealed a main effect for parenting conditions F(1, 414) = 195.05, p < .001, but not for denial of discrimination F(1, 414) = 1.49, p < .223 or the sexual orientation of the couple F(1, 414) = 1.35, p < .246. As predicted, however, a significant three-way interaction was found among denial of discrimination, the sexual orientation of the couple, and the parenting condition F(1, 414) = 4.22, p < .040.

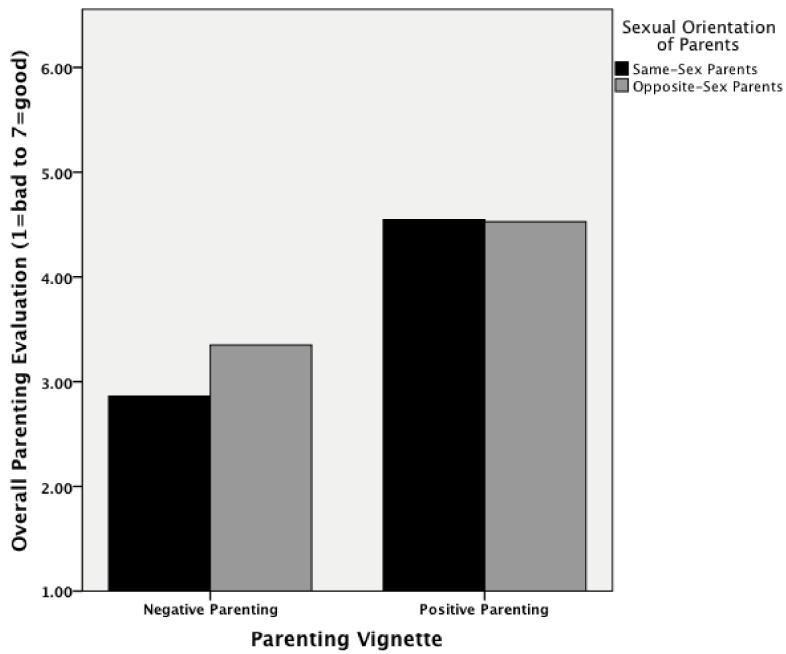

As shown in Figure 1, when evaluating a negative parenting situation, participants scoring above the mean on denial of discrimination rated same-sex parents more negatively (M = 2.86, SD = 1.27) than opposite-sex parents (M = 3.35, SD = 1.38). However, when evaluating a positive parenting situation, participants scoring above the mean on denial of discrimination evaluated same-sex and opposite-sex parents similarly (M = 4.55, SD = 1.35 and M = 4.53, SD = 1.17 respectively).

FIGURE 1.

Overall Evaluation of Parenting by Sexual Orientation of Parents and Parenting Condition for Participants Scoring Above Average in Denial of Discrimination

Separate Tukey-Kramer post hoc analyses were conducted for the positive and negative conditions to explore the three-way interaction and verify which conditions resulted in significant differences in parenting evaluations. Although the omnibus ANOVA revealed a significant three-way interaction, and the graphed mean differences appear in the predicted direction, the post-hoc tests failed to reveal significant differences in the evaluation of the parenting of same- and opposite-sex couples in the negative parenting conditions.

Interaction between Denial of Discrimination, Parenting Condition, Sexual Orientation, and Participant Gender

Hypothesis 3 predicted that participants’ gender would moderate the relationship between parenting condition, denial of discrimination, sexual orientation of the couple, and evaluation of parenting. Male participants with higher levels of denial of discrimination were expected to be more negative when evaluating same-sex parents in negative parenting condition than female participants. A four-way univariate ANOVA was conducted to investigate differences in overall parenting evaluation for participant gender, parenting condition, sexual orientation of couple, and levels of denial of discrimination. As shown in Table 6, the four-way interaction was significant F(11, 403) = 1.98, p = .029.

TABLE 6.

Four-way Univariate ANOVA for Overall Parenting Evaluation by Parenting Condition, Denial of Discrimination, Sexual Orientation of Parents, and Participant Gender.

| Source | Df | F | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| (A) Parenting Condition | 1 | 167.53 | .001 |

| (B) Denial of Discrimination | 1 | 2.92 | .088 |

| (C) Sexual Orientaton of Parents | 1 | 1.38 | .242 |

| (D) Participant Gender | 2 | 1.41 | .245 |

| A × B × C × D (interaction) | 11 | 1.98 | .029 |

| Error (within group) | 403 |

In order to investigate the differences that contributed to this interaction, the split file option in SPSS was used to conduct separate 2-way univariate ANOVAS holding parenting condition and participant gender constant. As shown in Table 7, a significant interaction was found between sexual orientation of parents and denial of discrimination for male participants in negative parenting conditions F(1, 75) = 6.19, p = .015. No other significant interactions were found for any other conditions.

TABLE 7.

Two-way Univariate ANOVA for Overall Parenting Evaluation by Denial of Discrimination and Sexual Orientation of Parents (for Male Participants in Negative Parenting Condition Only).

| Source | Df | F | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| (A) Denial of Discrimination | 1 | 1.62 | .207 |

| (B) Sexual Orientation of Parents | 1 | 0.83 | .365 |

| A × B (interaction) | 1 | 6.19 | .015 |

| Error (between group) | 75 |

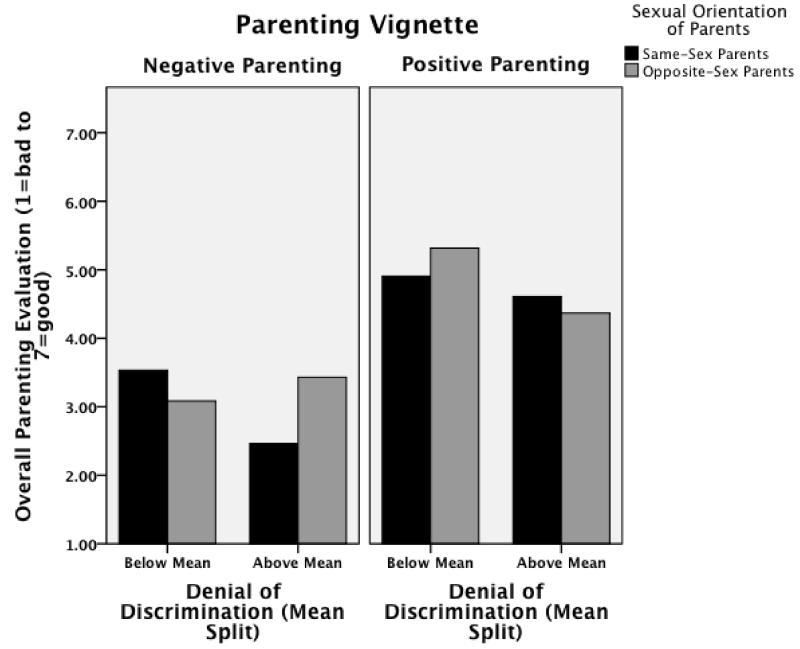

Tukey-Kramer post-hoc tests were then conducted to explore the significant interaction between sexual orientation of the parents and denial of discrimination for male participants in the negative parenting condition and determine which mean differences in parenting evaluation were significant. In negative parenting situations, male participants scoring above the mean on denial of discrimination were significantly more negative (p < .05) in their evaluation of same-sex parents (M = 2.47, SD = 1.11) than were those scoring below the mean (M = 3.53, SD = 1.08). In addition, as shown in Figure 2, male participants scoring above the mean on denial of discrimination, were significantly (p < .01) more negative in their evaluation of same-sex parents in negative parenting situations (M = 2.47, SD = 1.11) than in their evaluation of opposite-sex parents (M = 3.43, SD = 1.41). None of the other post hoc tests were significant.

FIGURE 2.

Male Participants Overall Parenting Evaluation by Denial of Discrimination, Parenting Condition and Sexual Orientation.

Discussion

The current study has explored how heterosexual participants’ attitudes toward gay men and lesbians affect their relative evaluation of the parenting practices and skill of same-sex versus opposite-sex couples. Overall, participants’ evaluation of parenting was not directly affected by the sexual orientation of the parents being evaluated. This finding was consistent with public opinion data, which has suggested that, in general, attitudes toward gay men and lesbians have been improving, and that attitudes toward same-sex parenting are also improving (Gates, 2011; Massey, 2010; Pew Research Center, 2011).

However, as predicted, traditional (or “old-fashioned”) heterosexism continues to negatively influence heterosexuals’ judgments of same-sex parents. Participants with higher levels of traditional heterosexism were found to evaluate the parenting behaviors of same-sex parents more negatively than the very same parenting behaviors of opposite-sex parents.

It was also predicted that as anti-homosexual prejudice has become less socially acceptable, instead of disappearing altogether, it would become more subtle and manifest in situations in which it could be attributed to a non-prejudiced cause. Consequently, modern anti-homosexual prejudice (measured as denial of discrimination) would interact significantly with the sexual orientation of the couple and the parenting condition, affecting participants’ evaluations of the parenting behavior. This prediction was also supported. Participants who scored higher in modern anti-homosexual prejudice were more critical of the negative parenting behaviors of same-sex parents than the very same behaviors among opposite-sex parents. However, this difference was not found in positive parenting situations.

Finally, because past research has demonstrated that males have tended to express more anti-homosexual prejudice than females, it was predicted that the modern prejudice effect, described above, would be more robust for male participants that for females. This prediction was also supported. When participant gender was added to the model, a significant four-way interaction was revealed. Post hoc tests showed that when evaluating a negative parenting situation, male participants with higher levels of denial of discrimination will evaluate same-sex parents significantly lower than opposite-sex parents. These differences were not found among female participants or in positive parenting situations.

One explanation for these findings is that the persistence of anti-homosexual prejudice may be at odds with more widespread positive shifts in attitudes toward gay men and lesbians and same-sex parenting. Consequently, the expression of these attitudes is becoming more subtle. When called on to evaluate the positive parenting of same-sex parents, the pressures to conform to increasingly gay- and lesbian-affirmative societal expectations will lead those higher in modern anti-homosexual prejudice to express more favorable judgments. However, when evaluating less than desirable parenting behaviors among same-sex parents, when a negative judgment is likely to be attributed to negative parenting behaviors, those higher in modern prejudice will make more negative judgments, and these judgments will be more negative than the judgments made for heterosexual parents engaging in similar negative parenting behaviors.

In addition, the relationship between anti-homosexual prejudice and the male gender role has been well established (Kimmel, 2004; Herek, 1986). Because anti-homosexual prejudice is particularly persistent among males, the need to channel this prejudice into a more subtle and relatively socially acceptable outlet is likely to be more pronounced for males.

Implications for Same-Sex Parenting

The last decade has seen some dramatic improvements in the rights of gay men, lesbians, and bisexuals in the United States: the dismantling of Don’t Ask Don’t Tell which prohibited gay men and lesbians from serving openly in the military; the U.S. Supreme Court’s Lawrence v Texas decision which overturned sodomy laws across the country; and the successes of the marriage equality movement (although this progress has been met by resistance - e.g., the recent passage of an amendment by voters in North Carolina that alters their state constitution to outlaw same-sex marriage, stating “marriage between one man and one woman is the only domestic legal union that shall be valid or recognized [in the state]”), to name only a few. These changes echo the continuing improvements demonstrated in public opinion research related to gay and lesbian rights.

Gay men and lesbians represent a ready and willing pool of prospective parents, and research has demonstrated them to be as capable and as beneficial as opposite-sex parents (Patterson, 2009). This may be particularly promising, given the great deal of progress still needed within the child welfare system. Reports from child welfare agencies across the United States reveal large numbers of children in need of permanent families. In 2010, over 400,000 children were in foster care and 115,000 children were waiting to be adopted (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2012). However, the number of families who have actually taken steps to adopt has been decreasing since 1995 (Jones, 2008). One particularly relevant application of this research, therefore, is in considering the impact modern anti-homosexual prejudice may have in the evaluation of same-sex couples as potential foster and adoptive parents.

Subjective evaluations are a core part of foster and adoption processes and take place during initial orientations, foster/adoption trainings, home studies, and staffing team meetings, among other encounters. However, these evaluations also provide opportunities for the displacement of anti-homosexual prejudice onto other decisions not directly related to the sexual orientation of the parents. Same-sex couples that are considering becoming parents, and who are scrutinized by adoption case-workers, court appointed special advocates, and family court judges among others, could become victims of modern anti-homosexual prejudice. Studying the relationship between modern anti-homosexual prejudice and evaluations of same-sex parenting is important, therefore, because it can reveal attitudes and subsequent behavioral patterns that individuals are not aware they possess. Raising awareness of these attitudes is vital to improving the lives of gay and lesbian people, but it is also a critical step in being able to utilize a potentially valuable pool of prospective adoptive and foster parents.

As stated earlier, trends in old-fashioned or traditional heterosexism are moving in a favorable direction. This study, however, suggests that overt old-fashioned prejudice is not the only type of prejudice affecting the lives of gay-, lesbian-, and bisexual-headed families. Although researchers have developed tools to measure modern anti-homosexual prejudice, similar public opinion data assessing modern prejudice has not yet become available. These data will need to be collected in order to properly assess the prevalence of this more subtle, but insidious, form of prejudice. As this literature grows, so will the practical information available to gay, lesbian, and bisexual parents and prospective parents, as well as practitioners in child welfare.

Finally, it is also important to remember that the values and ideological assumptions that are influencing prejudice, as well as the functions it serves, may be multiple (Herek, 2000b; Biernat, Vescio, & Theno, 1996). Modern racism, for example, has been found to be related to beliefs about affirmative action, economic competition, or reverse discrimination in employment (McConahay, 1986; Sears, 1988). Modern anti-gay anti-lesbian prejudice may also be associated with numerous values, beliefs, and concerns, including changing representations of the family and changing gender role expectations, shifting social values (i.e., marriage equality and attitudes about sex), and the increasing openness and influence of gay people worldwide. Although the current study explored the influence of a particular set of value and beliefs in a particular context, future research should explore other ways that modern prejudice is influencing heterosexuals’ attitudes toward gay, lesbian, and bisexual parents and their families.

Limitations

One challenge of using factorial ANOVA to explore these questions was that post-hoc interpretations of 3-way and 4-way interactions are challenging. Even when significant interactions have been found in the omnibus ANOVA, finding significant differences among particular interactions is frequently limited by increasingly small cell sizes and extremely conservative critical tests of significance. Although Rosenthal and Rosnow (1985) have suggest that the situation can be improved by focusing post-hoc tests on theory driven comparisons only, this greater complexity would necessitate more variables, and more variables are still best met with larger samples.

While larger sample sizes would be informative, so too would participant pools with wider sociodemographic variation. Participants in the current study were all university students. While this is consistent with much of the existing literature, the current sample did not allow for analyses across age groups, educational attainment, and many other sociodemographic characteristics.

Another possible limitation of the current study may have been the vignettes used. Teasing apart positive and negative condition can be difficult, given all the factors that go into one’s assessment of expected and acceptable parenting behavior. More subtle variation in the positive and negative conditions would help inform the consistency of these patterns; although, this would require substantial samples sizes. Moreover, extending these vignettes beyond readable text, to include audiovisual stimuli of scenarios would be interesting and informative. Future research should continue to extend the parenting scenarios for testing heteronormative prejudice.

Future Research

This study represents only a small part of a program of research that attempts to address and expand what is known about how same-sex parents navigate a world in which modern prejudice operates. A wide range of questions still remain regarding the influence of modern anti-homosexual prejudice.

Gender of active parent

Previous studies of anti-homosexual prejudice have suggested that gay men are evaluated more negatively than lesbians and that this difference is due primarily to the attitudes of heterosexual males toward gay men (Herek, 2002). In addition, many believe that women make better parents than men (Deutsch & Saxon, 1998). Although this study explored the influence of gender of participant, the sample size did not allow an investigation of the influence of the gender of the target (parent). It is likely that the gender of the evaluator and gender of the target will interact to influence evaluations of same-sex parenting practices.

Gender of child

Future research should continue to explore the various ways that gender interacts with anti-gay anti-lesbian prejudice. The current study examined at the interaction of gender of evaluator, gender of target, and modern prejudice in terms of their impact on the evaluation of parenting a male child. It is likely that the gender of the child will also affect both traditional and modern anti-gay anti-lesbian prejudice. In addition, the gender role of the evaluator is also an important factor. In what ways might gender role traditionalism influence participants’ judgments of same-sex and opposite-sex parenting?

Interpersonal contact

The significant influence of interpersonal contact on attitudes toward gay men and lesbians has been well documented (Herek & Capitanio, 1996). Massey (2010) reported a relationship between amount of contact and both old-fashioned and modern anti-homosexual prejudice. However, these findings were preliminary and did not explore the type and context of the contact and how it may interact with gender of evaluator and gender of target. Contact has been shown to have a greater effect on attitudes when the contact is in the context of equal status interactions (Allport, 1954; Herek, 1997). Public parenting may provide such a context; being a parent often creates opportunities for interaction with other parents. Future research should explore the effect of interpersonal contact, in the context of public parenting, on attitudes toward same-sex parenting. However, given the complex relationship between aversion and contact (Gaertner & Dovidio, 1986), it is also important to be aware of the influence modern anti-homosexual prejudice may have on the frequency of interaction between heterosexuals and homosexuals and their families.

Public parenting

This study has only explored the attitudes and judgments of heterosexuals toward gay men and lesbians. It is also necessary to explore how aware same-sex parents and their families are of these judgments, how important the attitudes of others are in their lives, and how (if at all) these families react to these potential judgments. What are the consequences of the possible microagressions on the physical and mental health of same-sex parents and their families? In what ways, if at all, do same-sex parents change their parenting practices to accommodate the judgments of a condemning public?

Modern anti-homosexual prejudice in other contexts

As Sears (1988) has pointed out, modern forms of prejudice are made manifest in symbolic ways. Just as modern racism was found to influence positions taken on government policies such as busing and affirmative action, modern anti-homosexual prejudice may influence how people understand the “definition” of marriage, what is in the “best interest of the child”, and threats to “unit cohesiveness”.

The values that collude with modern prejudice may extend beyond same-sex parenting and influence evaluations and decision-making in domains such as teaching, counseling, and law enforcement, among others. In these situations, the salience of anti-gay anti-lesbian stereotypes (i.e., sexually predatory, overly sensitive, not masculine/feminine “enough”, etc.) may be of particular concern. For instance, in two polls by the Gallup News Service (Newport, 2001), respondents’ views on employment protections for homosexuals varied considerably for different occupations. In a 2002 poll only 11% supported anti-gay discrimination in employment (Newport, 2003). When asked about particular occupations, however, the responses varied. Whereas only 6% were opposed to the occupations of salesman, the percent was significantly higher for high school teacher (33%), clergy (39%), or elementary school teacher (40%). Better tools are needed to explore how and when subtle prejudice continues to influence inter-group relations in a variety of socially and politically important situations. Future research should explore how modern prejudice has influenced these judgments and the experiences of gay men, lesbians, and bisexuals who occupy these roles.

Conclusion

The parents who shared their experiences during the 2011 LGBTQ Families Conference in Rochester, New York, described at the start of this paper, reported public parenting experiences that were both positive and negative. The current study has echoed the ambivalence of these experiences, demonstrating (albeit among undergraduate college students) tentative progress that may also guide the evaluations of practitioners, service providers and the general public in terms of improving attitudes toward same-sex parenting. Although overt and hostile prejudice may indeed be diminishing, modern, subtle, prejudice continues to affect the lives of lesbians, gay men, and their families. Prejudicial judgments, however subtle, that serve to limit access of these families to potential support and resources, ultimately harm today’s youth. Scholars must continue to explore the impact this subtle but pernicious prejudice has on the well-being of same-sex families, and how best to reduce its presence.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Interdisciplinary Research Group for the Study of Sexuality at Binghamton University, State University of New York. Justin R. Garcia is supported in part by National Institutes of Health NICHD grant T32HD049336.

Appendix A

Vignettes

Positive Parenting

You are sitting in a restaurant eating dinner. Across the room are [two women] sitting together with what looks to be a four-year-old boy. You notice that the two are holding hands. [One woman, Mary], places [her] arm around [the other, Beth], and leans over and kisses [her] on the cheek. Then they both take turns talking to the child.

When their dinner arrives [Beth] puts some food in a small colorful bowl and places it in front of the child. The child looks at it and frowns. All of a sudden he picks up his bowl of food, throws it on the floor and starts screaming. Other people in the restaurant turn to look at them. [Beth] picks the child up and tries to get him to calm down. The child pushes away yelling, “no! no! no!” It takes [Beth] several minutes to calm the child down and get him to sit back down in his highchair. [Mary] places a new bowl of food in front of the child. Eventually the child begins eating on his own.

Negative Parenting

You are sitting in a restaurant eating dinner. Across the room are [a man and a woman] sitting together with what looks to be a four-year-old boy. You notice that the two are holding hands. [The man, Steve], places his arm around [the woman, Beth], and leans over and kisses [her] on the cheek. Then they both take turns talking to the child. When their dinner arrives [Steve] puts some food in a small colorful bowl and places it in front of the child. The child looks at it and frowns. All of a sudden he picks up his bowl of food, throws it on the floor and starts screaming. Other people in the restaurant turn to look at them. [Steve] grabs the bowl off the floor and in an angry raised voice tells the child to be quiet and eat his dinner. The child picks up the bowl and starts to throw it. [Steve] smacks the child’s hand and yells at him to “put that down!”. The child starts to cry. It takes [Steve] several minutes to calm the child down. It is clear [Steve] is getting more and more frustrated by the child’s behavior. But eventually [he] gets him to sit back down at the table. [Beth] places a new bowl of food in front of the child. Eventually the child begins eating on his own.

Footnotes

Note: Bracketed text varies by sexual orientation of the couple and the gender of active parent. Brackets did not appear in versions provided to participants.

Contributor Information

SEAN G. MASSEY, Binghamton University, Binghamton, NY.

ANN M. MERRIWETHER, Binghamton University, Binghamton, NY

JUSTIN R. GARCIA, The Kinsey Institute and Indiana University, Bloomington, IN

References

- Allport G. The Nature of Prejudice. Addison Wesley; New York, NY: 1954. [Google Scholar]

- American Civil Liberties Union LGBTQ Relationships. 2011 Retrieved from https://www.aclu.org/lgbt-rights/lgbt-relationships.

- Anderson KJ, Kanner M. Inventing a gay agenda: Students’ perceptions of lesbian and gay professors. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2011;41:1538–1564. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes M, Massey S. Austin American-Statesman. Jun 3, 2001. Voices of gay Austin; pp. A1pp. A18–A19.pp. K1pp. K10–K11. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes M, Massey S. Austin American-Statesman. Gay and Straight in Austin. unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Bem SL. The measurement of psychological androgyny. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1974;42(2):155–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bem SL. Gender schema theory: A cognitive account of sex typing. Psychological Review. 1981;88:354–364. [Google Scholar]

- Calzo JP, Ward LM. Media exposure and viewers’ attitudes toward homosexuality: Evidence for mainstreaming or resonance? Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media. 2009;53(2):280–299. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty A, McKenzie K. Does racial discrimination cause mental illness? British Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;180:475–477. doi: 10.1192/bjp.180.6.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark R, Anderson NB, Clark VR, Williams DR. Racism as a stressor for African Americans. American Psychologist. 1999;54:805–816. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.10.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J, Major B. Social stigma and self-esteem: The self-protective properties of stigma. Psychological Review. 1989;96:608–630. [Google Scholar]

- Fouts G, Inch R. Homosexuality in TV situation comedies. Journal of Homosexuality. 2005;49(1):35–45. doi: 10.1300/J082v49n01_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaertner SL, Dovidio JF. The aversive form of racism. In: Dovidio JF, Gaertner SL, editors. Prejudice, Discrimination, and Racism. Academic Press; Orlando, FL: 1986. pp. 61–89. [Google Scholar]

- Gates GJ. Family formation and raising children among same-sex couples. National Council on Family Relations, FF51. 2011 winter. Retrieved from http://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/Gates-Badgett-NCFR-LGBT-Families-December-2011.pdf.

- Gerbner G, Gross L, Morgan M, Singnorielli N. The “mainstreaming” of America: Violence profile no. 11. Journal of Communication. 1980;30(3):10–29. [Google Scholar]

- Gerbner G, Gross L, Morgan M, Singnorielli N, Shanahan J. Growing up with television: Cultivation processes. In: Bryant J, Zillmann D, editors. Media Effects: Advances in Theory and Research. 2nd ed. Lawrence J. Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 2002. pp. 43–67. [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM. Attitudes toward lesbians and gay men: A factor analytic study. Journal of Homosexuality. 1984;10(1-2):39–51. doi: 10.1300/J082v10n01_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM. On heterosexual masculinity: Some psychical consequences of the social construction of gender and sexuality. American Behavioral Scientist. 1986;29(5):563–577. [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM. Heterosexuals’ attitudes toward lesbians and gay men: Correlates and gender differences. Journal of Sex Research. 1988;25(4):451–477. [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM. Sexual prejudice and gender: Do heterosexuals’ attitudes toward lesbians and hay men differ? Journal of Social Issues. 2000a;56(2):251–266. [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM. The social construction of attitudes: Functional consensus and divergence in the US public’s reactions to AIDS. In: Maio G, Olson J, editors. Why we evaluate: Functions of Attitudes. Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2000b. pp. 325–364. [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM. Gender gaps in public opinion about lesbians and gay men. Public Opinion Quarterly. 2002;66(1):40–66. [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM, Capitanio JP. “Some of my best friends”: Intergroup contact, concealable stigma, and heterosexuals’ attitudes toward gay men and lesbians. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1996;22(4):412–424. [Google Scholar]

- Jones J. Vital and Health Statistics. 27. Vol. 23. National Center for Health Statistics, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Hyattsville, MD: 2008. Adoption experiences of women and men and demand for children to adopt by women 18-44 years of age in the United States, 2002. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_23/sr23_027.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz I, Hass RG. Racial ambivalence and American value conflict: Correlational and priming studies of dual cognitive structures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;55:893–905. [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel MS. Masculinity as homophobia: Fear, shame, and silence in the construction of gender identity. In: Murphy PF, editor. Feminism and Masculinities. Oxford University Press; 2004. pp. 182–199. [Google Scholar]

- Kite ME, Deaux K. Gender belief systems: Homosexuality and the implicit inversion theory. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1987;11:83–96. [Google Scholar]

- Kite ME, Whitley BE. Sex differences in attitudes toward homosexual persons, behaviors, and civil rights: A meta-analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1996;22(4):336–353. [Google Scholar]

- LaMar L, Kite M. Sex differences in attitudes toward gay men and lesbians: A multidimensional perspective. Journal of Sex Research. 1998;35(2):189–196. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald AP, Huggins J, Young S, Swanson RA. Attitudes toward homosexuality: Preservation of sex morality or the double standard? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1973;40(1):161. doi: 10.1037/h0033943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macomber JE, Gates GJ, Badgett MVL, Chambers K. Adoption and Foster Care by Gay and Lesbian Parents in the United States. The Williams Institute, UCLA School of Law; Los Angeles, CA: 2007. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Massey SG. Sexism, heterosexism, and attributions about undesirable behavior in children of gay, lesbian, and heterosexual parents. Journal of GLBT Family Studies. 2007;3(4):457–483. [Google Scholar]

- Massey SG. Polymorphous prejudice: Liberating the measurement of heterosexuals’ attitudes toward lesbians and gay men. Journal of Homosexuality. 2009;56(2):147–172. doi: 10.1080/00918360802623131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey SG. Valued differences or benevolent stereotypes? Exploring the influence of positive beliefs on anti-gay and anti-lesbian attitudes. Psychology & Sexuality. 2010;1(2):115–130. [Google Scholar]

- McAdam T, Schneider D. Coming out in the Tier: Narrow attitudes limit acceptance. Press & Sun-Bulletin. 2005 Jun 12;:A.1. [Google Scholar]

- McConahay JB. Modern racism and modern discrimination: The effects of race, racial attitudes, and context on simulated hiring decisions. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1983;9(4):551–558. [Google Scholar]

- McConahay JB. Modern racism, ambivalence, and the modern racism scale. In: Dovidio JF, Gaertner SL, editors. Prejudice, Discrimination, and Racism. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 1986. pp. 91–125. [Google Scholar]

- Milkman KL, Akinola M, Chugh D. Temporal distance and discrimination: An audit study in academia. Psychological Science. 2012 doi: 10.1177/0956797611434539. doi: 10.1177/0956797611434539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse CN, McLaren S, McLachlan AJ. The attitudes of Australian heterosexuals toward same-sex parenting. Journal of GLBT Family Studies. 2007;3:425–455. [Google Scholar]

- Netzley SB. Visibility that demystifies: Gays, gender, and sex on television. Journal of Homosexuality. 2010;57(8):968–986. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2010.503505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newport F. American attitudes toward homosexuality continue to become more tolerant. Gallup News Service; Princeton, NJ: 2001. Retrieved from http://www.gallup.com/poll/4432/american-attitudes-toward-homosexuality-continue-to-become-more-tolerant.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- Newport F. Public shifts to more conservative stance on gay rights. Gallup News Service; Princeton, NJ: 2003. Retrieved from http://www.gallup.com/poll/8956/public-shifts-more-conservative-stance-gay-rights.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- Paige RU. Proceedings of the American Psychological Association, Incorporated, for the legislative year 2004; Minutes of the meeting of the Council of Representatives July 28 & 30, 2004; Honolulu, HI. 2005; Retrieved November 18, 2004, from the World Wide Web http://www.apa.org/governance/. (To be published in Volume 60, Issue Number 5 of the American Psychologist. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson CJ. Children of lesbian and gay parents: Psychology, law, and policy. American Psychologist. 2009;64:727–736. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.64.8.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson AR, Dovidio JF, Gaertner SL. The nature of contemporary prejudice: Insights from aversive racism. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2009;3(3):314–338. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center Most Say Homosexuality Should Be Accepted By Society. 2011 Retrieved from http://pewresearch.org/pubs/1994/poll-support-for-acceptance-of-homosexuality-gay-parenting-marriage.

- Raja S, Stokes JP. Assessing attitudes toward lesbians and gay men: The modern homophobia scale. Journal of Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Identity. 1998;3(2):113–134. [Google Scholar]

- Raley AB, Lucas JL. Stereotype or success? Prime-time television’s portrayals of gay male, lesbian, and bisexual characters. Journal of Homosexuality. 2006;51(2):19–38. doi: 10.1300/J082v51n02_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliff JJ, Lassiter GD, Markman KD, Snyder CJ. Gender differences in attitudes toward gay men and lesbians: The role of motivations to respond without prejudice. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2006;32(10):1325–1338. doi: 10.1177/0146167206290213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal R, Rosnow RL. Contrast analysis: Focused comparisons in the analysis of variance. Cambridge University Press; New York, NY: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Sauer R. Palm Beach Post. Apr 29, 2005. Out in South Florida; pp. 1E–5E. [Google Scholar]

- Sears DO. Symbolic racism. In: Katz I, Taylor S, editors. Eliminating Racism: Profiles in Controversy. Plenum Press; New York, NY: 1988. pp. 53–84. [Google Scholar]

- Sears DO, Henry PJ, Kosterman R. Egalitarian values and contemporary racial politics. In: Sears DO, Sidanius J, Bobo L, editors. Racialized Politics: The Debate about Racism in America. University of Chicago Press; Chicago, IL: 2000. pp. 75–117. [Google Scholar]

- Smith DM, Gates G. A Human Rights Campaign Report. 2001. Gay and Lesbian Families in the United States: Same-Sex Unmarried Partner Households: A Preliminary Analysis of 2000 United States Census Data. Retrieved from http://www.urban.org/url.cfm?ID=1000491. [Google Scholar]

- Solo’rzano D, Ceja M, Yosso T. Critical race theory, racial microaggressions, and campus racial climate: The experiences of African American college students. Journal of Negro Education. 2000;69:60–73. [Google Scholar]

- Spence JT, Helmreich RL. Comparison of Masculine and Feminine Personality Attributes and Sex-Role Attitudes Across Age Groups. Developmental Psychology. 1979;(15):5, 583–584. [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM, Spencer SJ, Aronson J. Contending with group image: The psychology of stereotype and social identity threat. In: Zanna M, editor. Advances in experimental social psychology. Vol. 23. Academic Press; New York: 2002. pp. 379–440. [Google Scholar]

- Sue DW, Capodilupo CM, Torino GC, Bucceri JM, Holder AMB, Nadal KL, Esquilin M. Racial Microaggressions in Everyday Life: Implications for Clinical Practice. American Psychologist. 2007;62(4):271–286. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.4.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services The AFCARS Report: Preliminary FY 2010 Estimates as of June 2011. 2012 Retrieved from http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/cb/stats_research/afcars/tar/report18.pdf.

- Whitley BE. Right-wing authoritarianism, social dominance orientation, and prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;77(1):126–134. [Google Scholar]