Abstract

Background

One method for the delivery of therapeutic proteins to the spinal cord is to inject nonviral gene vectors including plasmid DNA into the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) that surrounds the spinal cord (intrathecal space). This approach has produced therapeutic benefits in animal models of disease and several months of protein expression; however, there is little information available on the immune response to these treatments in the intrathecal space, the relevance of plasmid CpG sequences to any plasmid-induced immune response, or the effect of this immune response on transgene expression.

Methods

In the present study, coding or noncoding plasmids were delivered to the intrathecal space of the lumbar spinal region in rats. Lumbosacral CSF was then collected at various time points afterwards for monitoring of cytokines and transgene expression.

Results

This work demonstrates, for the first time, increased tumor necrosis factor-α and interleukin-1 in response to intrathecal plasmid vector injection and provides evidence indicating that this response is largely absent in a CpG-depleted vector. Transgene expression in the CSF is not significantly affected by this immune response. Expression after intrathecal plasmid injection is variable across rats but correlates with the amount of tissue associated plasmid and is increased by disrupting normal CSF flow.

Conclusions

The data obtained in the present study indicate that plasmid immunogenicity may affect intrathecal plasmid gene therapy safety but not transgene expression in the CSF. Furthermore, the development of methods to prevent loss of plasmid via CSF flow out of the central nervous system through the injection hole and/or natural outflow routes may increase intrathecal plasmid gene delivery efficacy.

Keywords: Plasmid, Intrathecal, Inflammatory, CpG, lipopolysaccharide, gene therapy

Introduction

Injection of plasmid DNA encoding potential therapeutic proteins into the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) that surrounds the spinal cord (intrathecal space), alone or in combination with electroporation or ultrasound, has been used to regenerate peripheral nerves after transection [1] and to treat neuropathic pain [2–7]. In addition, several studies have demonstrated significant transgene expression in cells [8,9] and CSF [4,6,10] after intrathecal plasmid injection. A potentially important side-effect of intrathecal gene therapy is an immune response to the plasmid DNA. Unmethylated CpG sequences in plasmid DNA are immunogenic [11–14]. The immune response to CpG DNA is mediated by toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9) [15], which binds to single-stranded CpG DNA [16] in the lysosome [17]. Therefore, double-stranded CpG DNA (plasmids or genomic bacterial DNA) is considered to first denature to a single-stranded form in the lysosome before interacting with TLR9 [16]. Plasmid DNA is known to cause immune stimulation when injected intramuscularly [18] or intravenously [19]. Intracisternal (cisterna magna) injection of bacterial DNA or short single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (ODN), but not vertebrate DNA, induced meningitis in lipopolysaccharide (LPS) nonresponder C3H/HeJ mice [20]. However, it is not known whether intrathecal injection of conventional CpG-replete plasmid vectors in amounts required for gene therapy applications produces a significant immune response and whether utilization of plasmids lacking CpGs significantly reduces this response. Plasmid DNA stays largely intact after intrathecal injection as a result of low CSF DNAse activity [10]. This makes the molar amount of plasmid DNA (and therefore the concentration of potential TLR9 activating ligand in the intrathecal space) low compared to the much shorter ODNs or sonicated genomic bacterial DNA. Characterization of any CpG-dependent intrathecal plasmid immune response would be useful for the rational design of nonviral gene delivery vectors with improved tolerability and safety in the intrathecal space.

In addition to safety issues, plasmid CpG sequences could potentially affect transgene expression via two possible mechanisms: (i) induction of an immune response to unmethylated CpG sequences (which is explored here) or (ii) formation of heterochromatin structures, which can induce a transcriptionally silent DNA state, on plasmid DNA via in vivo CpG methylation after delivery [21,22]. A plasmid-induced immune response may limit transgene expression via transgene product targeting (i.e. cytotoxic T cell response and/or antibody formation) or via a temporary reduction of the ability of cells to take up or express transgenes. For example, intrathecal delivery of the cationic polymer polyethylenimine (PEI) complexed with plasmid, but not plasmid or PEI alone, caused cell death and inhibited expression from a subsequent PEI/DNA complex injection given 2 weeks later but not 4 weeks later [9]. However, whether a plasmid-induced immune response limits expression from subsequently injected plasmid in the intrathecal space is not known and is of interest for plasmid intrathecal gene therapy. In the present study, we provide evidence that intrathecal plasmid injection induces an immune response that is largely absent in a CpG-depleted plasmid and that this plasmid-dependent immune response does not affect subsequent CSF transgene expression. We also present data suggesting that altering CSF flow increases intrathecal transgene delivery.

Materials and methods

Plasmids

Plasmid pCpG+ [SEAP] (7246 bp, 1072 CpG) contains two adeno-associated virus serotype 2 inverted terminal repeats (ITRs) flanking the gene expression cassette which consists of a cytomegalovirus enhancer, chicken β-actin promoter, an intron, human placental alkaline phosphatase (modified to be secreted [23]; SEAP) cDNA including an approximately 400 nucleotide portion of the natural 3′ untranslated region and an SV40 polyadenylation signal. Plasmid pCpG+ (5340 bp, 834 CG) is the same as pCpG+ [SEAP], but with the SEAP cDNA completely deleted and both plasmids were grown in SURE-2 cells (Stratagene). The pCpG+ used in all of the experiments except those measuring SEAP expression also lacked ITRs (5007 bp, 770 CG) and were grown in DH5-α cells. Plasmid pCpG− (4078 bp, 0 CG) was grown in GT-115 cells (Invivogen, San Diego, CA, USA) and was made by deleting the DNA between BsrGI and BsaBI in pCpG+vitro-neo-LacZ (Invivogen),which completely deletes the eukaryotic expression cassette. All CpG represent the counting of both strands. Plasmids were purified using the EndoFree Plasmid Giga kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). After purification, plasmid preps contained between undetectable and 1 ng of LPS (<0.012 EU–2.9 EU) per 100 µg of DNA. In several cases, these plasmid preparations were further cleaned by applying a second purification step to the plasmid solution using a scaled up version of the ‘Removal of endotoxins from purified plasmid DNA using the EndoFree Plasmid Maxi Kit’ method as outlined on the Qiagen website (http://www1.qiagen.com/literature/protocols/pdf/QP12.pdf). This procedure usually reduced LPS contamination to undetectable levels (<0.012 EU/100 µg plasmid).

Testing of plasmid TLR-9 interaction using HEK293 cells

HEK 293 cells were transfected with pNiFty-Luc and a mouse TLR9 expression plasmid (pUNO-mTLR9) or just pNiFty-Luc (Invivogen) using Lipofectamine (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), washed 2 h later, trypsinized and plated in 90 µl of growth media [Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) + 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) + pen/strep; Invitrogen) onto a 96-well plate. Six hours later, 10 µl of sample was added (100 µl of DNAse treated DNA was added to wells after removing the 90 µl of media already present). Twenty-four hours later, 100 µl of Steady-Glo luciferase assay reagent (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) was added. The chemiluminescence of 150 µl of this lysate was anaylized using a Dynex luminometer (Chantilly, VA, USA). DNAse treatment was performed by adding 5 µl of DNAse I (512 units/µl; Invitrogen) to 100 µl of either pCpG+ or pCpG− (300 µg/ml in growth media) and incubating for 2 h at 37 °C.

LPS contaminant quantification

LPS contamination of plasmid preparationswas quantified using HEK-blue-4 cells (Invivogen). These cells were grown and utilized in growth media consisting of DMEM (Invitrogen), 10% FBS, a mixture of four selection antibiotics to maintain the transgenes (HEK-blue-4 selection), Normocin (Invivogen) and pen-strep (Invitrogen). Cells were split into a 96-well tissue culture plate and left until they were approximately 90% confluent. The plate was then decanted and 90 µl of media was gently added to each well. Ten microliters of standard or sample in serum free media was then added. Ultrapure K-12 Escherichia coli LPS (Invivogen) was used to make a standard curve (8 pg/ml to 5 ng/ml). Plasmids or ODNs were added at a final concentration of 100 or 200 µg/ml. Twenty-four hours later, media was analysed using a chemiluminescent SEAP detection kit (catalog no. 11 779 842 001; Roche, Mannheim, Germany).We used an endpoint chromogenic LAL assay (Cambrex, Walkersville, MD, USA) to determine the amount of endotoxin units (EU) per ng of K-12 LPS. Four concentrations of K-12 LPS in triplicate were plotted (EU/ml versus ng/ml) and a line fitted to the data (R2 = 0.97, slope = 2.9 EU/ng). Thus, the K-12 LPS contains 2.9 EU/ng and the method described above has a detection limit of between 0.012 and 0.024 EU or 4–8 pg of LPS/100 µg of DNA.

Animals

Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan Labs, Madison, WI, USA), weighing 325–350 g on arrival, were maintained under a 12 : 12 h light/dark cycle with food and water provided ad libitum. All rat experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Colorado at Boulder.

Intrathecal injection, CSF collection and chronic constriction injury (CCI)

Intrathecal injection was performed as described previously [10]. Briefly, a PE-10 catheter connected to a 25-µl Hamilton syringe was loaded with 4 µl of 0.9% saline and then with up to 20 µl of DNA, LPS, etc. An 18-gauge needle was inserted between vertebra L5 and L6 and the catheter was inserted through the needle and 3.5 cm up to approximately vertebra T13 where the injectant was delivered. Lumbosacral CSF was collected by pulling (with minimal pressure) CSF into the catheter at the site of injection or by collecting the natural outflow of CSF from the inserted 18-gauge needle. At times, this CSF was split into two or three aliquots for analysis. All samples were put on dry ice and then stored at −80 °C. CCIs were performed as described previously [24].

SEAP, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-1 quantification

SEAP was quantified using a chemiluminescent assay (catalog no. 11 779 842 001; Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN, USA) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions, with a few modifications as noted [10]. Molarity of SEAP was calculated assuming a 53-kDa SEAP protein standard. TNF-α (catalog no. SRTA00), IL-6 (catalog no. SR6000B) and IL-1β (catalog no. SRLB00) were quantified using Quantikine colorimetric sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analysis was performed using SPSS, version 16, for windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). SEAP expression and cytokine expression after intrathecal injection does not appear to be normally distributed [10]. The gamma distribution also does not allow for less than zero values of expression, which makes biological sense for transgene expression. Accordingly, comparisons between groups at a single time point were made using a generalized linear model (GLZ) [25], assuming a gamma distribution with a log link unless indicated otherwise. For comparisons between groups that were sampled at more than one time point, a generalized estimating equation (GEE) [25] was used to account for the dependency between data from the same rat taken at different time points. This dependency was modelled as first-order autoregressive. The cytokine and luciferase expression also appeared to have variance that depended on the mean; therefore, these were also analysed using the same methods. Post-hoc comparisons were performed via estimated marginal means using sequential Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. p < 0.05 (two-tailed) was considered statistically significant.

Results

Intrathecal injection of CpG containing plasmid induces increased cytokine production

Transgene expression after intrathecal plasmid delivery appears to be maximal at plasmid doses of at least tens of micrograms per injection in rats. A 25-µg plasmid injection produced higher expression in tissue [7] and CSF [6] than a 10-µg injection in rats. A 100-µg intrathecal plasmid injection is capable of producing significant expression for at least 4 months [10]. We hypothesized that intrathecal injection of a plasmid completely lacking CpGs in amounts conducive to high-level, long-term expression in rats (i.e. 100 µg) would elicit a reduced inflammatory response as compared to a conventional CpG replete plasmid. To test this hypothesis, we used two noncoding plasmids: pCpG+, which contains 770 CpGs and pCpG−, which contains 0 CpG. Plasmid-induced activation of TLR9 has been reported previously [11]; however, given the lack of a clear CpG motif for phosphodiester DNA [26], we first wanted to confirm the ability of these two plasmids to differentially activate TLR9 before injecting in rats. To this end, HEK293 cells, which do not express any known TLRs [27], were transfected with a TLR9 expression construct and a nuclear factor (NF)-κB-responsive luciferase plasmid. Signaling through TLR9 activates NF-κB, which binds to DNA binding sites upstream of the luciferase transgene, increasing luciferase expression. Addition of pCpG+ significantly increased luciferase production in a dose-dependent manner compared to pCpG− (Figure 1a, p < 0.01, GLZ assuming normal distribution and identity link). These results were replicated in a similar, independent experiment. We also found that the increased response to pCpG+ compared to pCpG− was DNA-dependent because pre-incubation of pCpG+ with DNAse abrogated its effects (Figure 1a), and was also TLR9-dependent because this differential response was not observed in cells transfected with only the NF-κB reporter plasmid (Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

pCpG+ activates TLR9, whereas pCpG− does not. HEK 293 cells were transfected with (a) a TLR9 expression plasmid and an NF-κB responsive SEAP reporter plasmid (pNIFTY) or (b) a noncoding plasmid (pCpG+) and pNIFTY. Up to 300 µg/ml pCpG+ (92 nM plasmid, 71 µM CpG) and pCpG− (112 nM plasmid, 0 CpG), DNAse digested plasmid, or media were added in triplicate 8 h after transfection. Twenty-four post-transfection cell lysate luciferase was assayed. The difference between background activities (compare media lane between panels) is attributed to transfection variability. Data are the mean ± SEM

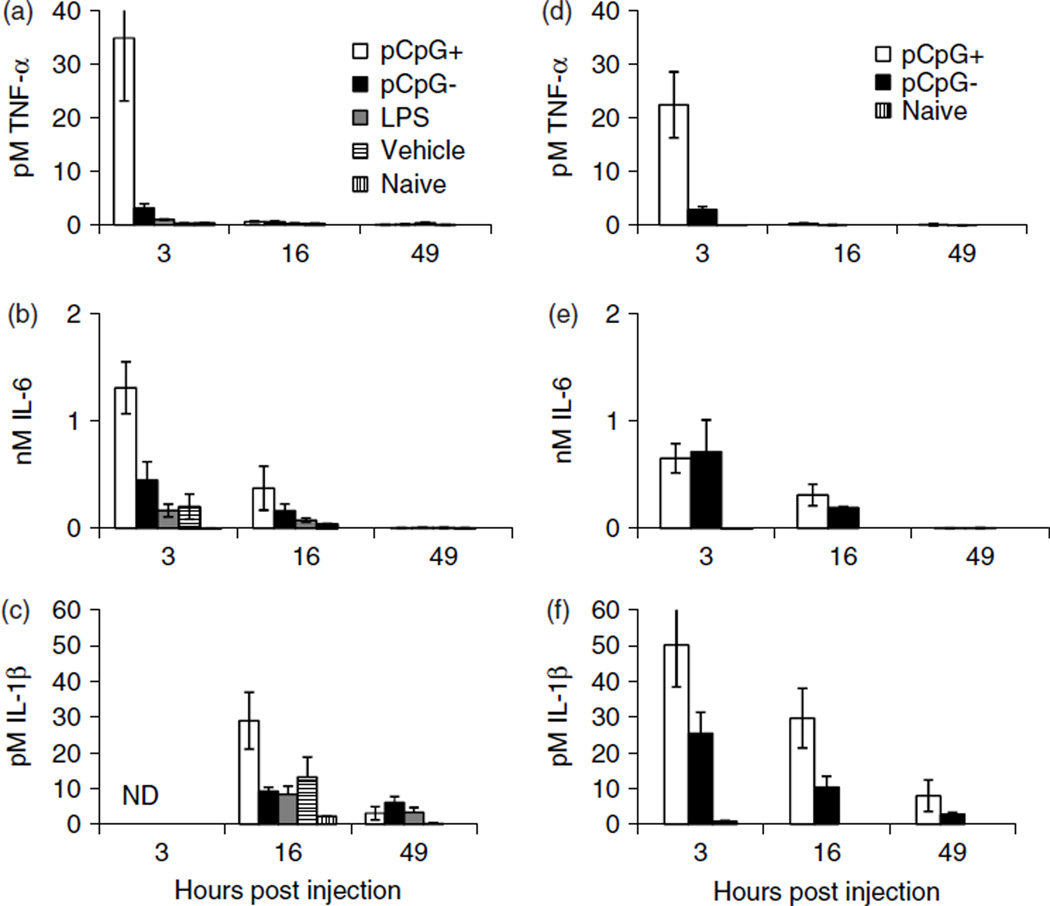

To determine whether plasmid CpGs induce an inflammatory response after injection into the intrathecal space, equimolar amounts of pCpG+ (120 µg) and pCpG− (100 µg) plasmid preparations (both 7.5 mg/ml) with undetectable LPS [<4 pg of LPS (0.012 EU; see Material and methods)/100 µg DNA] were injected intrathecally. Controls included naïve animals, animals injected with 20 µl of vehicle or with 15 pg of LPS. Lumbosacral CSF, defined here as CSF collected with the catheter placed between vertebra T13 and L5 or spontaneous CSF flow from a needle placed between L4 and L5 or L5 and L6, was collected 3, 16 and 49 h later. The CSF was assayed for mediators of the acute inflammatory response: TNF-α, IL-6 and, in some cases, IL-1. Injection of pCpG+ produced significantly higher amounts of TNF-α and IL-6 in lumbosacral CSF at 3, 16 and 49 h post-injection compared to all other treatments (p < 0.01, GEE; Figures 2a and 2b). The 15-pg LPS injection caused a small (approximately two-fold) but significant increase in TNF-α levels compared to vehicle (Figure 2a). IL-1 lumbosacral CSF concentrations were not significantly different between injection groups at 16 and 49 h post-injection (Figure 2c), most likely as a result of reduced sample size. Nevertheless, IL-1 was greatest in the pCpG+ injected group, following the same trend as TNF-α and IL-6.

Figure 2.

Intrathecal injection of pCpG+, pCpG−, LPS or vehicle. (a–c) Rats were injected intrathecal with equimolar amounts of pCpG+ (120 µg, 7.5 µg/µl, 770 CpG) or pCpG− (100 µg, 7.6 µg/µl, 0 CpG) containing undetectable (<4 pg of LPS/100 µg DNA) amounts of LPS, 15 pg of LPS (10 pg/µl) or vehicle. Lumbosacral CSF was collected (spontaneous needle outflow) just prior to injection (naive group) and at 3, 16 and 49 h post-injection [n = 4–5 per group except IL-6 at 16 and 49 h (n = 2–4), IL-1 (n = 2–4) and naive (n = 7–8)] and assayed for TNF-α, IL-6 or IL-1 via ELISA. (a) At the 3-h time point 15 pg of LPS (n = 5) elicited 1 ± 0.1 pM TNF-α, whereas vehicle (n = 4) elicited 0.4 ± 0.05 pM TNF-α. (d–f) Rats were injected with 100 µg of the additionally purified pCpG+ preparation used in (a–c) (n = 5, again undetectable LPS) or pCpG− (n = 4)with added LPS (measured at 13 pg of LPS/100 µg plasmid). Lumbosacral CSF was collected and assayed as above (naive n = 4). Molar values were calculated assuming 51-kDa TNF-α, 22-kDa IL-6 and 18-kDa IL-1β standards. Data are the mean ± SEM

LPS and DNA stimulation of TNF-α production have been shown to be additive [28]. To exclude the possibility that a small amount of contaminating LPS in the plasmid preparations was responsible for the observed difference between pCpG+ and pCpG− injections, another experiment, similar to that just described, was performed. The pCpG+ plasmid preparation used in the previous experiment was repurified to further reduce contaminants and conversely LPS was added to the pCpG− plasmid preparation. Each plasmid was again tested for LPS contamination, and once more the pCpG+ plasmid had an undetectable level of LPS (<4 pg of LPS/100 µg plasmid), whereas the pCpG− plasmid with added LPS measured 13 ± 1 pg of LPS/100 µg plasmid. One hundred micrograms of these two plasmid preparations were then injected intrathecally and CSF was collected at 3, 16 and 49 h post-injection. TNF-α and IL-1 levels for the pCpG− and pCpG+ injected animals mirrored those observed in the first experiment; however, there was an apparent (but not statistically significant, p = 0.13, GEE) decrease in IL-6 cytokine level for the pCpG+ group between the first and second experiments. Again, pCpG+-injected animals had significantly higher TNF-α and IL-1 levels across time compared to the pCpG− group (p < 0.05, GEE; Figures 2d and 2f) and IL-6 was no longer different between the two groups (Figure 2e). These data again suggest that the CpG sequences contained in pCpG+, rather than contaminating LPS, are responsible for the increased TNF-α and IL-1 after intrathecal plasmid delivery.

Prior injection of immunogens does not affect transgene expression from a subsequent injection

The inflammatory response to plasmid DNA after intrathecal delivery could not only limit plasmid tolerability, but also affect subsequent transgene expression. Several studies have identified a temporary refractory period after an initial injection of nonviral vector during which a second injection is less effective. This may be a result of the inflammatory response to the vector or to saturation of plasmid uptake cell machinery. This refractory period has been observed in studies involving cationic lipid–protamine–DNA complex delivery to the lung [29] and in intrathecal delivery of PEI/DNA complexes [9]. In addition, a robust vector induced inflammatory response could increase the chances of the development of an acquired immune response to the transgene product and thereby decrease the duration of expression. To determine whether an inflammatory response affects transgene expression from intrathecally delivered plasmid, either noncoding plasmid (100 µg pCpG+) containing various levels of LPS commonly found in our plasmid preparations after one round of purification (0.2, 2 or 20 ng of LPS/100 µg plasmid), LPS alone (100 pg, 10 ng or 10 µg) or vehicle was injected and, 2 days later, 25 µg of pCpG+ [SEAP] was injected in all rats. pCpG+ [SEAP] consists of the SEAP open reading frame inserted into the pCpG+ expression cassette. These rats also received unilateral CCI of the sciatic nerve at mid thigh level [24], which was not found to affect SEAP expression (for rationale for the use of this CCI model, see below). Surprisingly, all pre-injections had no significant effect (compared to vehicle pre-injection) on expression from a subsequent injection of pCpG+ [SEAP] (Figure 3a and Table 1), despite the inflammatory response associated with intrathecal injection of pCpG+ (Figure 2) and LPS (Figure 4) and the lack of such a response associated with vehicle injection (Figures 2 and 4).

Figure 3.

No significant effect of prior immune stimulation or CCI on transgene expression in CSF. (a) Rats were injected intrathecal with either vehicle (n = 12) or 100 µg of pCpG+ containing 0.2 ng of LPS (n = 18), 2 ng of LPS (n = 8) or 20 ng of LPS (n = 8) and, 2 days later, 25 µg of pCpG+ [SEAP] was injected. Fourteen days after pCpG+ [SEAP] injection, lumbosacral CSF was collected. SEAP was also measured in lumbosacral CSF 92 days post-injection in some of the rats (Vehicle, 1.8 ± 0.5 pM SEAP, n = 4 and pCpG+, 6 ± 2 pMSEAP, n = 6). All of these experiments used rats with CCI surgery. (b) Rats with (n = 16) or without (n = 14) CCI surgery were injected with 25 µg of pCpG+ [SEAP] 10 days after surgery. Fourteen days after pCpG+ [SEAP] injection, lumbosacral CSF was collected and assayed for SEAP activity. These rats also received a first injection of vehicle or pCpG+, which did not significantly affect transgene expression. The data presented in both panels originate from three independent experiments for each panel, using pCpG+ [SEAP] containing either 0.004 or 0.34 ng of LPS per injection; these varying LPS levels in the second injection did not significantly affect transgene expression so that the data were combined for analysis. Data are the mean ± SEM

Table 1.

SEAP concentration (pM) in lumbosacral CSF

| Vehicle (n = 4) |

First injectiona 100 pg of LPS (n = 4) |

10 ng of LPS |

10 µg of LPS (n = 4) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Day 7 | Day 7 | Day 7 | Day 7 |

| 20 ± 5 | 13 ± 6 | 34 ± 13 (n = 4) | 32 ± 16 |

| Day 14 | Day 14 | Day 14 | Day 14 |

| 14 ± 6 | 12 ± 4 | 17 ± 6 (n = 7) | 25 ± 16 |

| Day 92 | Day 92 | Day 92 | Day 92 |

| 1.8 ± 0.5 | 2.7 ± 1.4 | 2.8 ± 0.7 (n = 7) | 1.7 ± 0.6 |

Values in these columns are concentrations of SEAP (pM, mean ± SEM) in lumbosacral CSF at the number of indicated days post-injection of 25 µg of pCpG+[SEAP], which was given 2 days after the first injection. There was no significant difference (p = 0.59, GEE) in expression between the groups. All animals had CCI surgery.

Figure 4.

Intrathecal injection of LPS. Rats were injected intrathecally with either vehicle (n = 6), 100 pg of LPS (n = 5), 10 ng of LPS (n = 5) or 10 µg of LPS (n = 5) and, 3 h later, lumbosacral CSF was collected and stored at −80 °C. An ELISA was then used to quantify TNF-α in the CSF. Mean ± SEM TNF-α concentration is shown. CSF from all LPS groups including 100 pg of LPS (3 ± 1 pM) contained significantly more TNF-α than the vehicle-injected (0.2 ± 0.02 pM) group (GLZ, p < 0.05)

A common pathological pain model does not affect expression in the CSF

Intrathecal gene therapy would be applied clinically in a disease background, and yet the effect of disease on intrathecal gene transfer efficacy has not been explored. In the central nervous system (CNS) nonviral gene therapy has often been used to treat animal models of neuropathic pain. CCI of the sciatic nerve is a common animal model of neuropathic pain. CCI causes multiple changes in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord, including increased glial activation [30], and therefore changes the environment into which the DNA is delivered, possibly changing plasmid uptake and expression. To test the effect of CCI on naked DNA gene therapy, rats with or without CCI were injected with 25 µg of pCpG+ [SEAP]. In three separate trials, no significant effect of CCI on lumbosacral CSF SEAP levels was detected (Figure 3b).

Altered CSF flow may increase transgene delivery efficacy

Transgene expression in the CSF after intrathecal delivery of plasmid is highly variable (Figure 3 and Table 1) [10]. Injection differences could result in variable plasmid delivery to tissues surrounding the intrathecal space. To determine whether the amount of plasmid in meningeal and spinal tissue is also variable and correlates with expression, rats (n = 7) were injected with pCpG− [SEAP] (plasmid pCpG− with the SEAP open reading frame inserted). One day later, lumbosacral CSF and a 5 mm length of spinal cord surrounding the site of DNA delivery were collected. CSF SEAP activity was significantly correlated with plasmid abundance (See supporting information, Doc S1) in this tissue at 1 day post-injection (p < 0.01, r2 = 0.848; Figure 5). Variation in injection most likely leads to variable plasmid amounts in the tissue.

Figure 5.

Plasmid abundance in spinal cord correlates with expression. Samples were obtained one day after intrathecal injection of 100 µg of pCpG− [SEAP] (n = 7; ○) or from a naive animal (n = 1; x). The samples consisted of lumbosacral CSF and a 5-mm length of spinal cord (including meninges and attached dorsal root ganglia) surrounding the site where DNA is delivered. CSF was assayed for SEAP concentration and the spinal cord tissue was assayed for the presence of pCpG− [SEAP] via quantitative PCR. CSF SEAP concentration versus plasmid abundance is shown

One variable involved in the injection is the guide needle placement (through which the catheter is threaded). CSF in rats is at higher than ambient pressure [31], which causes a large amount of CSF to be rapidly lost during and/or after injection. Rats that lose large amounts of CSF during catheter placement, prior to actual plasmid injection, would be expected to lose less CSF and, consequently, less plasmid out through the dura puncture site and or natural CSF outflow routes after plasmid delivery. These rats would be expected to retain more plasmid and hence express the transgene at higher levels. In support of this hypothesis, three out of three low expressing/low plasmid abundance rats (Figure 5) had little or no CSF outflow during catheter placement, whereas three out of four of the high expressing/high DNA abundance rats had high CSF outflow during catheter placement. To test whether CSF outflow affects expression, we performed a further experiment. Lumbar CSF was depleted in a group of rats via catheter insertion and, 2 days later, pCpG+ [SEAP] was injected. This procedure eliminated spontaneous CSF outflow during the injection of pCpG+ [SEAP]. This group had significantly increased SEAP expression at 7 and 14 days post-injection of pCpG+ [SEAP] compared to a group of rats that were simply injected with pCpG+ [SEAP] (p < 0.05, GEE; Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Prior injection of vehicle or insertion of catheter increases transgene expression from subsequently injected pCpG+ [SEAP]. Rats were injected with vehicle (n = 6), inserted with the catheter (n = 8) or received no treatment (n = 6) 2 days prior to injection of 25 µg pCpG+ [SEAP]; during the first injection, any spontaneous CSF outflow was collected (day 0, n = 15). Lumbosacral CSF was also collected 7 and 14 days after the pCpG+ [SEAP] injection and assayed for SEAP. Molar values were calculated assuming a 53-kDa SEAP standard. Data are the mean ± SEM

Discussion

These data provide evidence that the cytokine response to nonviral intrathecal gene delivery could be reduced or eliminated via reduction of plasmid CpGs. We found that a noncoding plasmid with CpG dinucleotides (pCpG+) caused increased TNF-α and IL-1 production after intrathecal injection compared to a noncoding plasmid completely lacking CpGs (pCpG−). This cyotokine release induced by pCpG+ also induces immune cell infiltration into the CSF, peaking at 24 h after plasmid injection, and consists mainly of macrophage (E. Sloane and L. Watkins, personal communication). The plasmid preparations used have <4 pg (0.012 EU) of LPS contamination per 100-µg plasmid injection, but pCpG+ still elicited a robust inflammatory response (Figure 2) comparable to that induced by injection of 10 ng (29 EU) of LPS (Figure 4). This amount of LPS is approximately 400-fold greater than the Food and Drug Administration limit for LPS contamination in intrathecal injections in humans of 0.2 EU/kg [32], suggesting that the inflammatory response to plasmid CpGs is practically significant and that reduction or elimination of CpGs may improve the safety and tolerability of plasmid DNA as a gene delivery vector in the intrathecal space. Other studies have provided evidence indicating that a reduction of plasmid CpGs enhances safety and tolerability of gene therapy in the periphery. Inactivation of plasmid CpG (via methylation) dramatically reduced inflammation after intramuscular injection in mice [18]. Intravenous injection of a CpG reduced plasmid reduced serum TNF-α concentration after injection [19]. Furthermore, mice injected (intravenous) or instilled (lungs) with CpG methylated [19,33] or CpG reduced [34,35] plasmid–lipid complexes showed reduced serum cytokine levels. Utilization of CpG depleted plasmids would likely enhance safety and tolerability of plasmid and lipid/polymer complexed plasmid gene delivery to the intrathecal space.

Transgene expression is not significantly affected by prior plasmid or LPS injection

Intrathecal delivery of noncoding CpG containing plasmid DNA or up to 10 µg of LPS, both of which induced a robust inflammatory response (Figures 2 and 4), does not decrease expression from transgenes delivered 2 days later (Figure 3a and Table 1). This suggests that plasmid DNA can be administered repeatedly at short intervals to the intrathecal space without loss of effectiveness. This is in contrast to intrathecal delivery of PEI/DNA complexes, which produced a refractory period, but is similar to PEI-PEG/DNA and naked DNA followed by PEI/DNA complexes, which did not [9]. These different outcomes suggest that the refractory period observed after PEI/DNA complex intrathecal injection may be induced by mechanisms besides or in addition to cytokine release initiated by toll-like receptor-4 (activated by LPS) and TLR9 (activated by CpG DNA). Injection of a SEAP encoding plasmid 2 days after immune stimulation would increase the possibility of immune cell transfection as a result of increased immune cell numbers in the intrathecal space [20]. Transfection of immune cells has been implicated previously in the development of anti-transgene antibodies and expression loss [36]. Transfection of immune cells leading to subsequent development of anti-SEAP antibodies and transfected cell clearance does not appear to be a major cause of expression decay in the present study because pre-injection of up to 10 µg of LPS did not decrease expression over the long term from a subsequently injected plasmid (Table 1). This is in agreement with our previous findings demonstrating that intrathecal injection of pCpG− [SEAP] does not induce anti-SEAP antibodies in the CSF or serum [10].

We have previously reported that an expression plasmid completely lacking CpGs outside of the transgene provided high-level long-term CSF SEAP expression after intrathecal injection [10]. However, whether reduced inflammatory response to this CpG-depleted vector or lack of post-delivery CpG methylation contributed to this high-level expression was not determined. These data suggest that the lack of a plasmid induced inflammatory response may not have been the cause of this increase.

Disrupted CSF flow may increase intrathecal plasmid delivery

Although it is not surprising that plasmid abundance correlates with SEAP concentration 1 day after injection, thewide range of SEAP concentration/plasmid abundance soon after injection (Figure 5) does suggest that variance in the injection procedure may be responsible for the high variance observed at this early time point. The amount of CSF outflow just prior to plasmid delivery positively correlated with expression and plasmid abundance 1 day after injection. This suggests that the release of CSF pressure leads to less CSF and plasmid flow out of the CNS immediately after injection. This hypothesis was supported by the improved expression observed from an injection of pCpG+ [SEAP] given 2 days after a lumbar puncture when CSF outflow is reduced (Figure 6).

These data suggest that plasmid loss via CSF flow significantly affects transgene expression. Alternatively, the biggest source of plasmid loss could be degradation of plasmids by DNAse in the CSF. However, DNAse plasmid degradation is not likely to comprise a major source of plasmid loss given that CSF contains little DNAse activity [10] and that linearization and electrophoresis of plasmid from CSF 3 h post-injection revealed that most of the 40 µg/ml DNA detected was still intact (DNA concentration measured via absorbance at 260 nm, after clean up of CSF using a Qiagen PCR purification kit). Therefore, the normally rapid flow of CSF out of the CNS (3 h half-life in humans) [37] or leakage of CSF from the lumbar puncture site is likely responsible for the majority of plasmid loss after intrathecal injection. Therefore, a reduction of CSF volume before injection or utilization of other methods to prevent plasmid outflow along natural and/or unnatural (needle puncture) sites after injection may improve the efficacy of intrathecal gene delivery.

In summary, the present study indicates that neither previous intrathecal injection of a CpG containing noncoding plasmid nor a CNS disease model (CCI) affect expression in the CSF after intrathecal plasmid injection. However, plasmid CpG sequences are an important immune activator in the intrathecal space and reduction of CpG motifs in plasmid DNA may improve tolerability of nonviral gene intrathecal delivery. In addition, outflow of CSF from the CNS via the injection puncture hole or natural outflow routes along the spine [38] after injection may significantly affect intrathecal plasmid gene delivery.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by NIH grants GM29090, DA024044, DA015642 and NIDA 018156 and Avigen Inc.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Supporting information may be found in the online version of this article.

References

- 1.Wang X, Wang C, Zeng J, et al. Gene transfer to dorsal root ganglia by intrathecal injection: effects on regeneration of peripheral nerves. Mol Ther. 2005;12:314–320. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen KH, Wu CH, Tseng CC, et al. Intrathecal coelectrotransfer of a tetracycline-inducible, three-plasmid-based system to achieve tightly regulated antinociceptive gene therapy for mononeuropathic rats. J Gene Med. 2008;10:208–216. doi: 10.1002/jgm.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee TH, Yang LC, Chou AK, et al. In vivo electroporation of proopiomelanocortin induces analgesia in a formalin-injection pain model in rats. Pain. 2003;104:159–167. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00496-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Milligan ED, Sloane EM, Langer SJ, et al. Repeated intrathecal injections of plasmid DNA encoding interleukin-10 produce prolonged reversal of neuropathic pain. Pain. 2006;126:294–308. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu CM, Lin MW, Cheng JT, et al. Regulated, electroporation-mediated delivery of pro-opiomelanocortin gene suppresses chronic constriction injury-induced neuropathic pain in rats. Gene Ther. 2004;11:933–940. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yao MZ, Gu JF, Wang JH, et al. Interleukin-2 gene therapy of chronic neuropathic pain. Neuroscience. 2002;112:409–416. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yao MZ, Wang JH, Gu JF, et al. Interleukin-2 gene has superior antinociceptive effects when delivered intrathecally. Neuroreport. 2002;13:791–794. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200205070-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meuli-Simmen C, Liu Y, Yeo TT, et al. Gene expression along the cerebral-spinal axis after regional gene delivery. Hum Gene Ther. 1999;10:2689–2700. doi: 10.1089/10430349950016735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shi L, Tang GP, Gao SJ, et al. Repeated intrathecal administration of plasmid DNA complexed with polyethylene glycol-grafted polyethylenimine led to prolonged transgene expression in the spinal cord. Gene Ther. 2003;10:1179–1188. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hughes TS, Langer SJ, Johnson KW, et al. Intrathecal injection of naked plasmid DNA provides long-term expression of secreted proteins. Mol Ther. 2009;17:88–94. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cornelie S, Hoebeke J, Schacht AM, et al. Direct evidence that toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9) functionally binds plasmid DNA by specific cytosine-phosphate-guanine motif recognition. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:15124–15129. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313406200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klinman DM, Yamshchikov G, Ishigatsubo Y. Contribution of CpG motifs to the immunogenicity of DNA vaccines. J Immunol. 1997;158:3635–3639. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stacey KJ, Sweet MJ, Hume DA. Macrophages ingest and are activated by bacterial DNA. J Immunol. 1996;157:2116–2122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yasuda K, Yu P, Kirschning CJ, et al. Endosomal translocation of vertebrate DNA activates dendritic cells via TLR9-dependent and -independent pathways. J Immunol. 2005;174:6129–6136. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.10.6129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rachmilewitz D, Katakura K, Karmeli F, et al. Toll-like receptor 9 signaling mediates the anti-inflammatory effects of probiotics in murine experimental colitis. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:520–528. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rutz M, Metzger J, Gellert T, et al. Toll-like receptor 9 binds single-stranded CpG-DNA in a sequence- and pH-dependent manner. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:2541–2550. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Latz E, Schoenemeyer A, Visintin A, et al. TLR9 signals after translocating from the ER to CpG DNA in the lysosome. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:190–198. doi: 10.1038/ni1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McMahon JM, Wells KE, Bamfo JE, et al. Inflammatory responses following direct injection of plasmid DNA into skeletal muscle. Gene Ther. 1998;5:1283–1290. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kako K, Nishikawa M, Yoshida H, et al. Effects of inflammatory response on in vivo transgene expression by plasmid DNA in mice. J Pharm Sci. 2008;97:3074–3083. doi: 10.1002/jps.21254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deng GM, Liu ZQ, Tarkowski A. Intracisternally localized bacterial DNA containing CpG motifs induces meningitis. J Immunol. 2001;167:4616–4626. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.8.4616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Riu E, Chen ZY, Xu H, et al. Histone modifications are associated with the persistence or silencing of vector-mediated transgene expression in vivo. Mol Ther. 2007;15:1348–1355. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hong K, Sherley J, Lauffenburger DA. Methylation of episomal plasmids as a barrier to transient gene expression via a synthetic delivery vector. Biomol Eng. 2001;18:185–192. doi: 10.1016/s1389-0344(01)00100-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berger J, Hauber J, Hauber R, et al. Secreted placental alkaline phosphatase: a powerful new quantitative indicator of gene expression in eukaryotic cells. Gene. 1988;66:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90219-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bennett GJ, Xie YK. A peripheral mononeuropathy in rat that produces disorders of pain sensation like those seen in man. Pain. 1988;33:87–107. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90209-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davis CS. Statistical Methods for the Analysis of Repeated Measurements. New York, NY: Springer; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roberts TL, Sweet MJ, Hume DA, et al. Cutting edge: species-specific TLR9-mediated recognition of CpG and non-CpG phosphorothioate-modified oligonucleotides. J Immunol. 2005;174:605–608. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.2.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hornung V, Rothenfusser S, Britsch S, et al. Quantitative expression of toll-like receptor 1–10 mRNA in cellular subsets of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells and sensitivity to CpG oligodeoxynucleotides. J Immunol. 2002;168:4531–4537. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.9.4531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gao JJ, Xue Q, Papasian CJ, et al. Bacterial DNA and lipopolysaccharide induce synergistic production of TNF-alpha through a post-transcriptional mechanism. J Immunol. 2001;166:6855–6860. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.11.6855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li S, Wu SP, Whitmore M, et al. Effect of immune response on gene transfer to the lung via systemic administration of cationic lipidic vectors. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:L796–L804. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1999.276.5.L796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hu P, Bembrick AL, Keay KA, et al. Immune cell involvement in dorsal root ganglia and spinal cord after chronic constriction or transection of the rat sciatic nerve. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21:599–616. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2006.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mandell EC, Zimmermann E. Continuous measurement of cerebrospinal fluid pressure in unrestrained rats. Physiol Behav. 1980;24:399–402. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(80)90105-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Munson TE. Guideline for validation of the LAL test as an end-product endotoxin test for human and biological drug products. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1985;189:211–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yew NS, Wang KX, Przybylska M, et al. Contribution of plasmid DNA to inflammation in the lung after administration of cationic lipid: pDNA complexes. Hum Gene Ther. 1999;10:223–234. doi: 10.1089/10430349950019011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yew NS, Zhao H, Przybylska M, et al. CpG-depleted plasmid DNA vectors with enhanced safety and long-term gene expression in vivo. Mol Ther. 2002;5:731–738. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2002.0598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yew NS, Zhao H, Wu IH, et al. Reduced inflammatory response to plasmid DNA vectors by elimination and inhibition of immunostimulatory CpG motifs. Mol Ther. 2000;1:255–262. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2000.0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pastore L, Morral N, Zhou H, et al. Use of a liver-specific promoter reduces immune response to the transgene in adenoviral vectors. Hum Gene Ther. 1999;10:1773–1781. doi: 10.1089/10430349950017455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Davson H, Segal MB. Physiology of the CSF and Blood–Brain Barriers. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koh L, Zakharov A, Johnston M. Integration of the subarachnoid space and lymphatics: is it time to embrace a new concept of cerebrospinal fluid absorption? Cerebrospinal Fluid Res. 2005;2:6. doi: 10.1186/1743-8454-2-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.