Abstract

A series of square planar methylnickel(II) complexes, (dppe)Ni(Me)(SAr) (dppe = 1,2-bis(diphenylphosphino)ethane); 2. Ar = phenyl; 3. Ar = pentafluorophenyl; 4. Ar = o-pivaloylaminophenyl; 5. Ar = p-pivaloylaminophenyl; (depe)Ni(Me)(SAr), (depe = 1,2-bis(diethylphosphino)ethane); 7. Ar = phenyl; 8. Ar = pentafluorophenyl; 9. Ar = o-pivaloylaminophenyl; 10. Ar = p-pivaloylaminophenyl), were synthesized via the reaction of (dppe)NiMe2(1) and (depe)NiMe2(6) with either the corresponding thiol or disulfide. These complexes were characterized by various spectroscopic methods including 31P NMR, 1H NMR, 13C NMR and infrared spectroscopies and in most cases by X-ray diffraction analyses. Solid state and solution measurements establish that 5 and 9 contain intramolecular N-H---S bonds. Carbonylation of the complexes 2-4, 7-10 leads to (dRpe)Ni(CO)2 and MeC(O)SAr via the intermediacy of the acylnickel adducts, (dRpe)Ni(C(O)Me)(SAr), detected at low temperature by 31P NMR spectroscopy. Consistent with experimental observations, density functional theory results reveal that the intramolecular hydrogen bond in 9 stabilizes the acylnickel adduct compared with its non-hydrogen-bonded adduct, 10. Oxidative addition of MeC(O)SC6F5 to (dRpe)Ni(COD) followed by spontaneous decarbonylation proceeds in modest yields generating 3 and 8.

Introduction

Acetyl coenzyme A synthase (ACS), a Ni-Fe-S metalloenzyme found in methanogenic, acetogenic and sulfate-reducing organisms, is responsible for the assembly/disassembly of acetyl coenzyme A from CO, methylcob(III)alamin and the thiol, CoA.1,2 The assembly transformation allows acetogens to grow autotrophically on one-carbon substrates, whereas the disassembly into its constituent components permits methanogens to utilize acetate as an alternate substrate in methane production.3 Anaerobic methanogenesis accounts for the majority of methane production globally. Thus, a detailed understanding of biological methane production is requisite to understanding the global carbon cycle.1 Further motivation for detailed studies of the structure and function of ACS derive from a desire to understand the novel cofactors utilized by archaea and their ability to promote one-carbon transformations via the proposed intermediacy of unprecedented organometallic species in biology, including Ni-CO, Ni-CH3 and Ni-C(O)CH3 adducts.4

Recent protein crystal structure reports have revealed that the ACS active site is a Ni-Fe-S cluster of unprecedented composition and structure, Figure 1.5 The so-called A cluster consists of Ni2Fe4S4 organized into a cuboidal [Fe4S4] cluster linked via a bridging Cys to a dinickel subcluster. Their very different coordination environments distinguish the two Ni ions. The Ni proximal to the [Fe4S4], Nip, is ligated to three Cys residues, each bridging to other metal ions. The donor ligands for the square planar distal Ni, Nid, are two Cys side chain thiolates that bridge to Nip and two amide backbone donors derived from three successive amino acid residues, CysGlyCys. Despite the advances in the structural biology of ACS, there has been less progress in understanding how the protein structure encodes function, i.e. details regarding the mechanism of acetyl CoA synthesis. The common mechanistic scenarios6,7 invoke substrate binding and turnover at the dinickel subcluster with the role of the [Fe4S4] limited to either it serving as a conduit for electron transfer and/or to it regulating the electronic character at nickel.8 Indeed, the majority of synthetic modeling studies,9 including those from our laboratory,10-12 have targeted nickel complexes as appropriate platforms from which to derive chemical precedents and mechanistic understanding. Nonetheless, analogs that incorporate cuboid clusters have been prepared13 and remain attractive targets for synthetic and in particular, reactivity studies.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the A cluster. Non-protein ligand(s) of Nip not shown.

The elementary steps in the ACS catalytic cycle are summarized in Scheme 1. While the overall transformation is not strictly a redox reaction, the donation of the methyl group from the corrinoid protein likely requires a redox active metal site to accept a methyl cation equivalent, i.e. methyl transfer from cobalt to the A cluster is an oxidative addition process. Assignments of metal ion oxidation states during catalysis remain the subject of debate, with both Ni(I) and more recently, Ni(0),6 proposed as the fully reduced states competent in catalysis. Indeed, studies from these laboratories have established chemical precedents for methyl transfer from methylcobaloxime to nickel(I)14 or nickel(0)11 acceptors. The former occurs via a radical pathway, whereas the latter is suggested to proceed via a SN2 mechanism. The remaining steps in ACS catalysis leading to thioester formation are carbonylation to generate an acylnickel followed by CoA addition/reductive elimination yielding the thioester. There are a number of relevant precedents for these steps with monomeric nickel complexes with leading examples provided by Yamamoto,15 Holm,16,17 Hillhouse18 and Sellmann.19 Carbonylation of alkylnickel thiolates leads to CO insertion into the Ni-Me bond and acylnickel thiolate formation. Additional CO promotes reductive elimination of thioester with the Ni(0) fragment trapped by excess CO. Very recently we reported the initial example of thioester formation via carbonylation of a binuclear methylnickel,12 a model complex of higher structural fidelity.

Scheme 1.

General overview of ACS catalysis highlighting substrate binding only at Nip and invoking the ‘Ni(0)’ mechanism. The nickel redox states and the role of the [Fe4S4] cluster (not shown) remains issues of debate.

Despite the aforementioned advances in chemical precedents for ACS catalysis, several outstanding issues remain to be addressed. Principle to the present report is aspects of the final step in catalysis, i.e. the reductive C-S bond-forming step. In particular we are interested in understanding how acyl transfer to CoA occurs with high fidelity without acetylation of Cys residues in the A cluster. Three possibilities are considered- the first two highlight structural elements that serve to reduce the nucleophilicity of Cys residues so as to direct acetylation to CoA. First, bridging Cys thiolates as found in the A cluster are poorer nucleophiles than terminally ligated thiolates and therefore, less susceptible to acetylation. Thus, the positioning of the active site Cys residues in bridging positions likely serves to reduce the propensity of Cys acetylation during ACS catalysis. However, this hypothesis is complicated by experimental12 and computational20 evidence that suggest that these thiolate bridges are susceptible to facile and reversible rupture, a process that leads to a terminal Cys, a residue that would be accessible for acetylation. Second, the nucleophilicity of Cys residues can be modulated by hydrogen-bonding interactions. One such interaction involving a backbone amide N-H and a Ni-Cys is found at the A cluster, Figure 1. This structural element would render the hydrogen-bonded thiolate less nucleophilic. Indeed, hydrogen bonding to zinc-thiolates results in a measurable diminution of thiolate nucleophilicity as determined in protein and model studies.21,22 A third consideration is that acetylation of active site Cys residues does occur and the process is reversible such that Cys acetylation does not render the enzyme inactive. We consider this scenario plausible based on two lines of experimental evidence. First, ACS activation of acetyl CoA (and by extension acetyl-Cys) occurs in methanogens.23 Second, an in vitro assay of ACS activity involves CO incorporation into 14C-labeled acetyl CoA,24 a process that necessitates reversible C-S bond rupture. Herein, we present synthetic studies that address the role of hydrogen-bonding on C-S reductive elimination and that demonstrate thioester C-S oxidative addition to nickel(0) and place these results in the context of ACS catalysis.

Results and discussion

Synthesis of Complexes

The preparation of the (dRpe)Ni(Me)(SAr) complexes was achieved via one of two synthetic routes, each commencing with the corresponding (dRpe)NiMe2 complex, Scheme 2. Protonolysis with ArSH generated complexes 2, 3, 7 and 8 in good isolated yields. This procedure follows the route employed by Yamamoto15 in the synthesis of 2 and subsequently by Holm17 for the related (bpy)Ni(Me)(SAr) complexes. Complexes 4, 5,25 9 and 10 were synthesized by reaction of (dRpe)NiMe2 with the appropriate disulfide, Ar2S2, Scheme 2. The latter alkyl-for-thiolate exchange has been applied successfully to the preparation of zinc aryl thiolate complexes.22 At parity of dRpe chelating ligand, the ortho-substituted aryl disulfide reacted much more rapidly than the para isomer. We observed a similar trend for the reactions of these same disulfide substrates with methylzinc complexes. The basis for these relative rates is likely of electronic origin, because, in part, steric crowding at the transition state would seemingly disfavor, i.e. slow down, the reaction of the ortho isomer. If one considers the mechanism as involving Ni-Me attack on an electrophilic sulfur of the disulfide, Figure 2, then H-bonding within the ortho-substituted aryl disulfide is expected to enhance the electrophilicity of the disulfide and increase the reaction rate. Further, consistent with this analysis is the observation that the more electron-rich (depe)NiMe2 reacted faster than (dppe)NiMe2 at parity of the aryl disulfide substrate.

Scheme 2.

Figure 2.

Spectroscopic Properties

The 1H NMR spectra of complexes are highlighted by the Ni-methyl resonances which occur within the narrow range, δ = −0.25 to 0.50. The derivatives with the least donating thiolate ligands, C6F5 and ortho-pivaloylaminophenyl, contain the most highly shielded Ni-methyl resonances. The 31P NMR spectra are characterized by two doublets with 2JPP = ∼7-10 Hz for the dppe derivatives and 2JPP = ∼14-18 Hz for the depe derivatives. Complexes 4 and 9 contain intramolecular N–H---S bonds in solution as supported by the downfield chemical shifts of these protons in C6D6, δ = 9.88 for 4 and δ = 10.02 for 9. In complexes 5 and 10, the non-H-bonded amide protons of the para substituents are found at markedly higher field, δ = 6.68 for 5 and δ = 6.72 for 10. Solution (THF) and solid state FT-IR measurements also support H-bonding in 4 and 9 with νNH features broadened and shifted to lower energy, νNH = 3276 cm–1 for 4 and νNH = 3282 cm–1 for 9, Table 1.26 These modes are ca. 40-65 cm−1 lower in energy than those found for the non-H-bonded 5 and 10. The similarity between the solution and solid-state νNH energies supports the assertion that the intramolecular H-bonding in the solid state as determined by X-ray diffraction analyses, vide infra, is maintained in solution. Similar differences in νNH energies between ortho and para substituted arylthiolates were observed for monomeric zinc complexes.22

Table 1.

Solid state and solution IR data for complexes 4, 5, 9, and 10.

| 4 | 5 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| νN-H (cm−1)* | 3276 | 3342 | 3282 | 3324 |

| νC=O (cm−1)* | 1670 | 1662 | 1670 | 1661 |

| νN-H (cm−1)‡ | 3281 | 3374 | 3283 | 3360 |

| νC=O (cm−1)‡ | 1676 | 1675 | 1676 | 1679 |

Solid state, KBr;

Solution state, THF.

Molecular structures

The geometric structures of complexes 2-4, 7-10, Figures 3 and 4, have been determined by single crystal X-ray diffraction methods. Crystallographic data are collected in Table 2 with selected metric parameters contained in Table 3. Each complex shows the expected trans influence of the methyl donor as manifest in a statistically longer Ni–P bond distance for the phosphine trans to methyl. The Ni–S bond distances in 4, 2.144(1) Å, and 9, 2.184(2) Å are the shortest among the series. The decrease in bond lengths is attributed to the intramolecular N–H---S bonds which, by removing electron density from the thiolate sulfurs, serve to reduce the destabilizing Ni dπ–S pπ interactions. The amide substituents in 4 and 9 are positioned so as to ensure short N---S distances, 4, 2.973(4) Å and 9, 3.009(6) Å, consistent with solid state H-bonds. The amide hydrogens were not located in the Fourier difference maps.

Figure 3.

Thermal ellipsoid plots of 2, 3, 7 and 8 drawn at the 35% probability level. Hydrogen atoms and phenyl carbons of the dppe ligand (except for the ipso carbon) have been removed.

Figure 4.

Thermal ellipsoid plots of 4, 9 and 10 drawn at the 35% probability level. Hydrogen atoms and phenyl carbons of the dppe ligand (except for the ipso carbon) have been removed.

Table 2.

Crystallographic data for complexes 1-4, 7-10.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| formula | C28H30NiP2 | C33H32NiP2S | C33H27F5NiP2S | C38H41NNiOP2S | C17H32NiP2S | C17H27F5NiP2S | C22H41NNiOP2S | C22H41NNiOP2S |

| fw | 487.17 | 581.30 | 671.26 | 680.43 | 389.14 | 479.10 | 488.27 | 488.27 |

| cryst syst | monoclinic | monoclinic | monoclinic | monoclinic | orthorhombic | monoclinic | orthorhombic | monoclinic |

| space group | P21/c | P21/n | P21/n | P21/c | Fdd2 | P21/n | Pbca | P21/c |

| a, Å | 11.342(5) | 9.055(6) | 9.556(4) | 9.4485(11) | 33.934(3) | 9.378(3) | 17.408(3) | 12.256(2) |

| b, Å | 13.250(6) | 26.163(18) | 14.530(6) | 15.0012(18) | 68.417(9) | 19.435(6) | 17.549(3) | 11.7385(19) |

| c, Å | 16.491(7) | 12.560(9) | 21.763(8) | 24.172(3) | 6.7986(7) | 11.641(3) | 17.680(3) | 17.325(3) |

| α, deg | 90.00 | 90.00 | 90.00 | 90.00 | 90.00 | 90.00 | 90.00 | 90.00 |

| β, deg | 98.879(7) | 102.619(10) | 94.243(7) | 97.739(2) | 90.00 | 99.304(4) | 90.00 | 90.552(2) |

| γ, deg | 90.00 | 90.00 | 90.00 | 90.00 | 90.00 | 90.00 | 90.00 | 90.00 |

| V, Å3 | 2448.6(18) | 2904.0(3) | 3014.0(2) | 3394.9(7) | 15784(3) | 2095.9(10) | 5401.1(15) | 2492.4(7) |

| Z | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 32 | 4 | 8 | 4 |

| T | 120 | 170 | 170 | 120 | 120 | 120 | 290 | 120 |

| Dcalcd, g/cm | 1.322 | 1.330 | 1.480 | 1.331 | 1.518 | 1.201 | 1.301 | |

| 2θ range, deg | 2.38- 24.04 | 1.83 - 28.28 | 1.69-28.40 | 2.18 - 21.91 | 2.15-25.00 | 2.06-28.27 | 2.01-28.35 | 1.66-28.31 |

| μ(Mo, Kα) mm−1 | 0.936 | 0.871 | 0.873 | 0.758 | 1.244 | 1.220 | 0.926 | 1.003 |

| Reflections | 26720 | 39309 | 40744 | 38887 | 40255 | 28393 | 58983 | 29483 |

| Unique | 5686 | 7184 | 7521 | 8172 | 6932 | 5208 | 6733 | 6195 |

| R(int) | 0.0618 | 0.0384 | 0.0646 | 0.0707 | 0.0342 | 0.0233 | 0.1890 | 0.0340 |

| R1 | 0.0413 | 0.0367 | 0.0546 | 0.0511 | 0.0219 | 0.0245 | 0.0798 | 0.0356 |

| wR2 | 0.0972 | 0.0977 | 0.1290 | 0.1164 | 0.0525 | 0.0663 | 0.1627 | 0.0887 |

Table 3.

Selected bond distances (Å) and bond angles (°) of complexes 1-4, 7-10.

| Ni-Me | Ni-S | Ni-P1 | Ni-P2 | ∠P-Ni-P | N---S | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.975(3) 1.982(3) |

2.1536(9) | 2.1548(9) | 87.24(4) | ||

| 2 | 1.979(5) | 2.1858(12) | 2.2215(11) | 2.1366(11) | 87.41(4) | |

| 3 | 1.959(3) | 2.2082(5) | 2.1975(6) | 2.1251(11) | 87.28(4) | |

| 4 | 2.092(4) | 2.1443(11) | 2.2007(9) | 2.1442(9) | 87.34(3) | 2.973(4) |

| 7 | 1.965(2) | 2.2037(9) | 2.1967(9) | 2.1196(8) | 88.75(2) | |

| 8 | 1.980(4) | 2.2082(5) | 2.2177(11) | 2.1977(11) | 87.25(2) | |

| 9 | 1.966(6) | 2.1836(17) | 2.191(2) | 2.1198(17) | 87.90(8) | 3.009(6) |

| 10 | 1.9755(19) | 2.2200(6) | 2.1874(6) | 2.1146(6) | 88.32(2) |

Carbonylation Studies

A primary objective of this study was to examine the role of the thiolate substituents, in particular the intramolecular N–H---S bonds on the reductive elimination of thioester from the acylnickel thiolates. To achieve this objective we sought to intercept and isolate the acylnickel thiolates resulting from addition of one equiv. of CO to the methylnickel thiolates for subsequent kinetic studies of reductive elimination. Such species were inferred intermediates in the studies of Yamamoto15 on the carbonylation of alkylnickel aryl thiolates and aryloxides and one example was isolated by Holm.17 However, exposure of each of the complexes reported here, 2-4, 7-10, to one equiv. of CO at ambient temperature did not yield the desired acylnickel thiolates (except for in situ formation of a small amount 8, vide infra). Rather a mixture of starting material, (dR'pe)Ni(CO)2, and thioester was generated. The latter species resulted from CO-promoted reductive elimination. In all cases, exposure to 1 atm. of CO led to clean conversion to (dR'pe)Ni(CO)2 and the corresponding thioester in good to excellent yields. As these observations were consistent with instability of the targeted acylnickel thiolates relative to both reductive elimination and decarbonylation (i.e. reversible carbonylation), the stoichiometric addition of CO was conducted in situ at −78 °C. Indeed, these conditions afforded the acylnickel thiolate complexes, to varying degrees, as ascertained by 31P NMR spectral analyses (Figures S-6 to S-12). The extent of acylnickel thiolate formation was sensitive to the identity of the diphosphine and arylthiolate ligands. The derivatives containing the more electron rich depe chelating ligands yielded a greater extent of acylnickel thiolate at parity of thiolate donor, e.g. 4 yielded ∼25% acylnickel, whereas 9 yielded ∼55% acylnickel. Thus the more electron rich metal center stabilizes the acylnickel thiolate intermediate. In regard to the influence of the thiolate substituent, the complexes with the least electron-donating arylthiolates, namely those with C6F5 and the ortho-pivaloylaminophenyl substituents, formed the acylnickel thiolates to the greatest degree, e.g. 9 yielded ∼55% acylnickel, whereas 10 yielded ∼40% acylnickel. The derivatives containing the parent phenyl or electron rich para-pivaloylaminophenyl substituents yielded the small amounts of acylnickel intermediates, even at −78°C. In contrast, the room temperature spectra revealed that the combination of depe and C6F5 substituents led to formation of small amounts, ca. 15-20%, of (depe)Ni(C(O)Me)(SC6F5). This trend is in accord with the assertion that the least electron-rich (or least nucleophilic) thiolate is least prone to undergo spontaneous reductive elimination, a point supported by computational studies (vide infra).

Carbonylation of alkyl nickel complexes containing aryloxo and arylthiolato (including 2) has been extensively studied.15,27,28 In general, exposure of solutions of the nickel complexes to an atmosphere of CO resulted in conversion to the corresponding aryl ester or aryl thioester and nickel(0), e.g. L2Ni(CO)2, in good to excellent yields. In only one of these reports, a study of (bpy)Ni(Me)(SAr) complexes was an intermediate acyl species isolable.17

The Mechanism of Carbonylation

The migratory insertion of CO into a M–R bond is among the most thoroughly studied elementary steps in organotransition metal chemistry. At square planar platinum group metals associative and dissociative pathways often compete, with the former generally favored in nickel complexes.29 CO addition yielding a five-coordinate species poised for migratory insertion competes with a dissociative pathway in which CO adds to a three-coordinate T-shaped adduct formed via ligand loss. In the present context ligand dissociation would most probably entail thiolate loss as the chelating diphosphines are much less prone to dissociation. Thiolate exchange is facile in benzene solution as evidenced by formation of all four possible species upon mixing equilimolar concentrations of 2 and 8. The equilibrium constant, Keq = [2][8]/[3][7] = 1.2, indicating a slight preference for the formation of the complexes matching the more electron releasing diphosphine with the more electron-withdrawing arylthiolate.

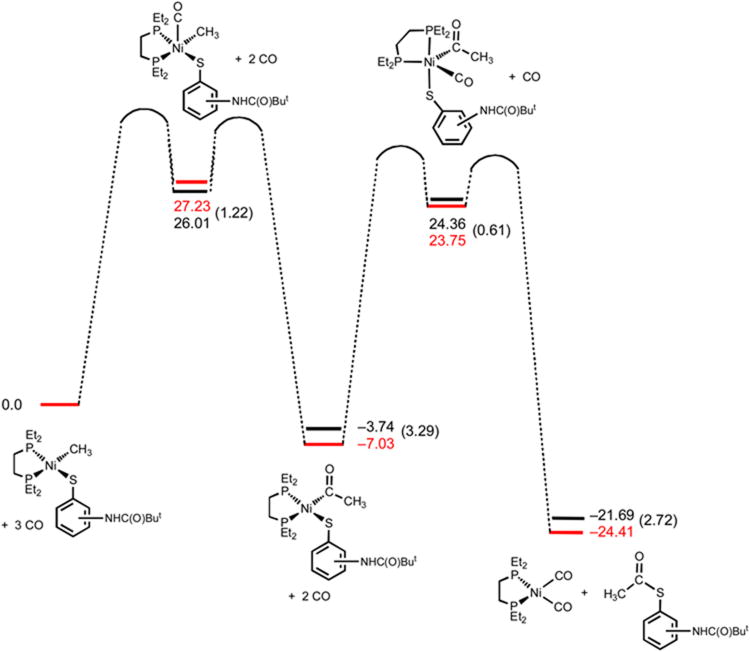

To further evaluate the factors that influence the relative stability of the acylnickel thiolates, the energies of the relevant species along a reaction sequence commencing with the methylnickel thiolates were examined by density functional theory (DFT) methods (B3LYP). Specifically, the relative energetics of stepwise carbonylation to the acylnickel thiolate, then to the products (dRpe)Ni(CO)2 and thioester, were determined for 9 and 10. In each case, the full molecule was calculated with results depicted in Figure 5. The overall reactions are exergonic by 24.4 kcal/mol for 9 and 21.68 kcal/mol for 10. The acylnickel thiolate resulting from carbonylation of 9 is 7.1 kcal/mol lower in energy than 9 + CO. In comparison, the carbonylation of 10 to the acylnickel thiolate is only favored by 3.7 kcal/mol (relative to 10 + CO). In other words, the acylnickel intermediate derived from 9 is 3.3 kcal/mol more stable than that derived from 10. These computational results are in accord with the experimental observations that the acylnickel complex derived from 9 is more stable than that derived from 10.

Figure 5.

The relative energies of DFT computed structures along the associative carbonylation reaction trajectory for complexes 9 (red) and 10 (black). Energies are in kcal/mol. Transition state energies were not calculated and are shown as arbitrary.

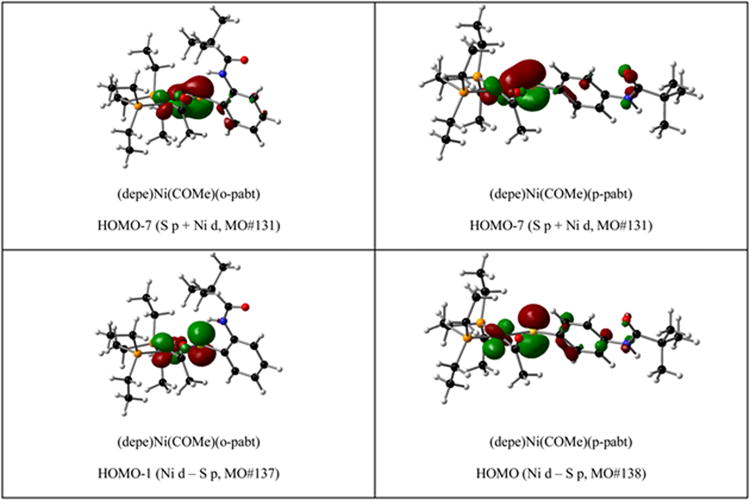

To quantitatively assess the impact of hydrogen bonding on the relevant frontier molecular orbitals, a Mulliken population analysis was performed on 9, 10, and the respective acylnickel counterparts formed upon addition of CO. The analysis agrees with the qualitative predictions noted previously. Specifically, the ortho substituent H-bonding proton is orientated towards the filled S p orbital, which is engaged in a Ni–S π anti-bonding interaction, Figure 6. The H-bonding interaction withdraws electron density from this orbital resulting in a more covalent Ni–S interaction, reflected in increased metal d character in the relevant orbitals as illustrated in Table 4, and shorter Ni–S distances reflected in the crystallographically derived structures. In the non-H-bonded case of 10, the S:Ni ratio for the bonding (S p + Ni d, HOMO-7) and anti-bonding (S p – Ni d, HOMO) are 23:63% and 64:23% respectively. In contrast, in the H-bonded case of molecule 9, the bonding (HOMO-6) and anti-bonding (HOMO) S:Ni ratios are 45:43% and 29:61% respectively. The drastically higher S character in the non H-bonded HOMO results in a significantly more nucleophilic S thiolate, and thus, a more favorable reductive elimination. The results for the acylnickel complexes follow the same trend.

Figure 6.

Isosurface plots (isodensity value 0.05) of Ni—S π and π* interactions from solvated single-point hybrid DFT calculations.

Table 4.

Mulliken population analysis from solvated single-point hybrid DFT calculations.

| molecule | MO | E (eV) | description | S (%) | Ni (%) | rest (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9 | 124 | −5.539 | S p + Ni d | 45.85 | 42.97 | 11.18 |

| 131 | −4.240 | Ni d − S p | 29.32 | 61.31 | 9.38 | |

|

| ||||||

| (depe)Ni(COMe)(o-pabt) | 131 | −5.579 | S p + Ni d | 30.79 | 50.85 | 18.36 |

| 137 | −4.388 | Ni d − S p | 31.85 | 55.39 | 12.76 | |

|

| ||||||

| 10 | 125 | −6.506 | S p + Ni d | 23.38 | 63.21 | 13.42 |

| 131 | −.936 | Ni d − S p | 64.43 | 22.83 | 12.74 | |

|

| ||||||

| (depe)Ni(COMe)(p-pabt) | 131 | −5.435 | S p + Ni d | 38.28 | 39.86 | 21.86 |

| 138 | −3.971 | Ni d − S p | 38.89 | 36.17 | 24.94 | |

We also computed the energies of species resulting from association of CO to 9 and 10 respectively, as plausible five-coordinate intermediates for the carbonylation reaction. In these structures CO occupies an apical position of the square pyramid. The CO adduct derived from 9 is destabilized by 1.2 kcal/mol relative to the corresponding adduct derived from 10. This trend is in agreement with the notion that the metal center in 9 is less electron rich because the intramolecular H-bonding more than compensates for the electron-releasing ability of the pivaloylamino substituent. Thus, in the associative carbonylation mechanism the slightly higher energy of the five-coordinate intermediate and more stabilized acylnickel intermediate both contribute to stabilize the acylnickel adduct derived from 9 relative to the acylnickel derived from 10.

Thioester Oxidative Addition to Ni(0)

Given the potential role of Ni(0) in ACS catalysis6 and its ubiquitous role in organometallic cross coupling reactions,30 we sought to establish oxidative addition of thioesters to Ni(0). In the latter setting, there is precedent for the use of thioesters as reagents in nickel cross-coupling reactions under Mukaiyama conditions with thioester oxidative addition to nickel(0) hypothesized as the first step in catalysis.31 Addition of MeC(O)SC6F5 or MeC(O)SPh to (dRpe)Ni(COD) generated in situ produced the corresponding alkylnickel thiolates in variable yields, 2 (7%), 3 (37%), 7 (50%), and 8 (62%). In the latter three reactions, the byproducts (dppe)2Ni and (dppe)Ni(CO)2 were also identified. Clearly, the more electron rich (depe)Ni fragment facilities the oxidative addition by stabilizing the Ni(II) state. The C6F5 substituent of the thioester renders the C–S bond more susceptible to cleavage. Reactions conducted at low temperature revealed initial formation of (variable amounts) the acylnickel thiolates consistent with sequential oxidative addition followed by decarbonylation to the more stable alkylnickel thiolates. In addition to providing insights into ACS catalysis, this decarbonylative C–S activation represents a transformation of some synthetic utility.32

One of the enzymatic assays for ACS activity entails CO exchange into 14C-labeled acetyl coenzyme A, eq. 1.24 The reversibility is not surprising given that the acetogens utilize ACS to

| (1) |

disassemble acetyl coenzyme A, i.e. the reaction is catalyzed in the reverse direction. The exchange reaction demands reversibility of each step in ACS synthesis. Significantly, reversible thioester formation affords a pathway for the enzyme to correct erroneous generation of acetyl-Cys at the A cluster active site. The affected Cys would be deacetylated with subsequent acetylation of CoA leading to product.

Summary and Conclusions Relevant to ACS Catalysis

The objectives of these studies were two-fold. First, we sought to quantitatively establish the effect of intramolecular N–H---S bonds on the reductive elimination of thioesters from acylnickel thiolates via kinetic studies. Thus, a series of (dRpe)Ni(Me)(SAr) were prepared including derivatives with pivaloylamino installed in ortho and para positions of the arylthiolate ring. The former isomers contain intramolecular H-bonds as deduced by solution and solid-state measurements. However, stoichiometric carbonylation did not lead to clean conversion to the desired acylnickel thiolates precluding detailed kinetic experiments. Rather, a mixture of species resulted indicating competitive formation of the ‘over-carbonylated’ reductive elimination products, (dRpe)Ni(CO)2 and thioester, eq. 2. This is somewhat surprising given the accessibility and stability of analogous complexes, (bpy)Ni(C(O)Me)(SAr). Low temperature 31P NMR studies revealed that the acylnickel thiolates are indeed intermediates on the path to thioester production. The generation of these intermediates was sensitive to the identity of the arylthiolate substituent, with the derivatives containing a H-bonded thiolate donor or electron-withdrawing C6F5 substituents more stable than the Ph or para-pivaloylaminophenyl derivatives. The relative stabilities of the ortho- and para-pivaloylaminophenyl acylnickel derivatives were supported by DFT analyses.

| (2) |

The reductive elimination of thioester is promoted by addition of an additional donor ligand, in this case CO. This has been most clearly established by addition of excess CO to the isolable acyl nickel complex (bpy)Ni(C(O)Me)(SAr) which leads to (bpy)Ni(CO)2 and thioester.17 This begs the question of what drives thioester C–S bond formation in ACS catalysis. As addition of CO appears to be tightly regulated by the enzyme,33 it is unlikely that addition of this ligand is employed to promote thioester formation. Two scenarios are considered. First, CoA may directly attack the acylnickel intermediate without prior formation of a Ni-thiolate bond. In this case a coordination site for CoA binding is not required. Alternatively, reductive elimination could be driven by (reversible) formation of a Ni-SCys bond. Recent experimental12 and computational20 studies have highlighted the possibility of bridging Cys hemi-lability in the mechanism of ACS synthesis. A clear synthetic precedent for the latter path remains to be established and would be of some interest.

The second objective of the present report was to demonstrate thioester oxidative addition to Ni(0) as this transformation (i) lends further support for the potential role of Ni(0) in ACS by highlighting the reversibility of C-S bond formation via the Ni(0)/Ni(II) redox couple and (ii) bears on the possibility of acetylated-Cys formation and repair at the ACS active site cluster. Addition of MeC(O)SC6F5 to (dRpe)Ni(COD) proceeded rapidly to the corresponding alkylnickel thiolate with concomitant formation of Ni(0) products, (dRpe)2Ni and (dRpe)Ni(CO)2.

Experimental Section

Synthesis

All manipulations were conducted in a nitrogen-filled glove box or on a Schlenk line under nitrogen. 215 was synthesized following literature procedures. Ortho- pivaloylaminobenzene disulfide and para-pivaloylaminobenzene disulfide were synthesized from the corresponding amino disulfides and pivaloyl chloride as described previously.34 (tmeda)NiMe235 and (dppe)NiMe236 were synthesized via a modification of the procedure reported28 for (dippe)NiMe2 in which dippe was replaced with tmeda and dppe, respectively. (Py)4NiCl228 was prepared via addition of pyridine to a suspension of anhydrous NiCl2 in ethyl ether. The resulting blue solid was isolated and washed with ethyl ether. The Pyridine, thiophenol, pentafluorobenzenethiol, and methyl lithium were purchased and used without further purification. Thiophenol was dried over 5 Å molecular sieves. Solvents were dried via passage through activated alumina columns and subsequently degassed by passing a stream of nitrogen. Deuterated solvents were purchased from Cambridge Isotopes and dried over 5 Å molecular sieves. Microanalyses were performed by Columbia Analytical Services, Tucson, AZ.

Physical Measurements

NMR spectra were recorded on a 400 MHz Bruker DRX spectrometer. Proton chemical shifts were referenced to the residual proton peak of NMR solvent. Phosphorous chemical shifts were referenced to the 85% H3PO4 in D2O external standards. Infrared spectra were measured using Mattson Genesis series FTIR spectrometer.

(dppe)Ni(Me)(SC6F5), 3

A solution of C6F5SH (95 μL, 0.7 mmol) in toluene (10 cm3) was added to a solution of 1 (0.487 g, 1.0 mmol) in toluene (50 cm3) at −78 °C. The mixture was stirred for 2 h while the temperature gradually increased to ambient temperature during which time a yellow solid precipitated. Pentane (50 cm3) was added to complete the precipitation. The supernatant was removed via cannula and the solid was washed with ethyl ether (3 × 30 cm3). The solid was dried under vacuum overnight to give 3 (0.30 g, 64%) as an orange-yellow powder. X-ray quality crystals were obtained from ethyl ether diffusion into a concentrated THF solution. mp 194 – 196 °C (THF/Ether). (Found: C, 59.4; H, 4.1. C33H27NiP2SF5 requires C, 59.05; H, 4.05%); δP (162 MHz; C6D6, H3PO4) 48.4, 61.5 (d, JPP 10.6, Ph2PCH2CH2PPh2), δC (100 MHz; C6D6, C6D6) 5.60 (dd, JPC 59.0 and JP′C 27.8, Ni-CH3), δH (400 MHz; C6D6, C6D6), 0.26 (3 H, dd, JPH 6.7 and JP′H 4.0, Ni-CH3), 1.53-1.72 (4 H, m, Ph 2PCH2CH2PPh2), 6.97 (7H, m), 7.06 (5H, m), 7.51(4H, m) and 7.84 (4 H, m) for (C6H5)2P-CH2CH2-P(C6H5)2).

(dppe)Ni(Me)(o-pabt), 4

A solution of o-pivaloylaminobenzenedisulfide (o-pabd) (0.250 g, 0.6 mmol) in toluene (20 cm3) was added dropwise to a solution of 1 (0.487g, 1.0 mmol) in toluene (50 cm3) at −78 °C. The mixture was stirred for 2 h while the temperature gradually increased to ambient temperature during which time a yellow solid precipitated. Ethyl ether (50 cm3) was added to complete the precipitation. The supernatant was removed via cannula and the solid was washed with ethyl ether (2 × 30 cm3). The solid was dried under vacuum overnight to give 4 (0.33 g, 80%) as an orange-yellow powder. Orange-yellow crystals were obtained from ethyl ether diffusion into a concentrated THF solution. (Found: C, 66.9; H, 5.8; N 1.7. C38H41NiP2NSO requires C, 67.1; H, 6.1; N 2.1%); νmax (KBr)/cm−1 3276 (m, NH) and 1660 (s, CO); νmax (THF)/cm−1 3281 (m, NH) and 1676 (s, CO); δP (162 MHz; C6D6, H3PO4) 47.3, 60.2 (d, JPP′ 7.5); δC (100 MHz; C6D6, C6D6) 6.70 (dd, JPC 57.6 and JP′C 26.6, Ni-CH3), 175.2 (s, SC6H4NHC(O)C(CH3)3); δH (400 MHz; C6D6, C6D6) 0.23 (3H, dd, JPH 7.3 and JP′H 4.1, Ni-CH3), 1.31 (9H, s, tBu), 1.59-1.84 (4H, m, (Ph)2P-CH2CH2-P(Ph)2), 6.79 (1 H, td, J1,2 7.2 and J1,3 4.2, p-(C6H4)S), 9.20 (1H, d, J1,2 7.2, o-(C6H4)N)) 7.00 (6 H, m), 7.10 (7 H, m), 7.48 (4 H, m), 7.8 (5 H, m((C6H5)2P-CH2CH2-P(C6H5)2) 9.88 (1H, s, NH).

(dppe)Ni(Me)(p-pabt), 5

A solution of p-pivaloylaminobenzenethiol (0.230 g, 1.04 mmol) in THF (10 cm3) was added dropwise to a solution of 1 (0.695, 1.42 mmol) in THF (50 cm3). The mixture was stirred overnight yielding a brown solution. The solution was taken into dryness, and washed with ethyl ether (3 × 20 cm3). The solid was dissolved in minimum volume of THF and precipitated with ethyl ether. Collected yellow solid was dried under vacuum giving crude 5 (0.216 g, 41%) contaminated with (dppe)2Ni. Repeated recrystallization from THF/ethyl ether yielded spectroscopically pure 5. (Found: C, 66.1; H, 6.0; N 1.9. C38H41NiP2NSO requires C, 67.1; H, 6.1; N 2.1%); νmax(KBr)/cm−1 3342 (m, NH) and 1662 (s, CO); νmax(THF)/cm−1 3374 (NH) and 1675 (CO); δP (162 MHz; C6D6, H3PO4) 60.2, 47.0 (d, JPP 7.8 (Ph)2P-CH2CH2-P(Ph)2), δC (100 MHz; C6D6, C6D6) 6.57 (dd, JPC 58.8 and JP′C 25.7, Ni-CH3), 174.4 (s, SC6H4NHC(O)C(CH3)3); δH (400 MHz; C6D6, C6D6) 0.49 (3 H, dd, JPH 7.8 and JP′H 4.2, Ni-CH3), 0.97 (9H, s, tBu) 1.64-1.89 (4 H, m, (Ph)2P-CH2CH2-P(Ph)2), 6.90-7.02 (16 H, m), 7.10 (4 H, m), for (C6H5)2PCH2CH2P(C6H5)2; 6.74 (s, NH).

(depe)NiMe2, 6

A solution of depe (470 μL, 2 mmol) in ethyl ether (5 cm3) was added to a suspension of (tmeda)NiMe2 (0.408 g, 2 mmol) in ethyl ether (40 cm3) at −78 °C. The mixture was stirred for an hour at −78 °C and an hour at ambient temperature during which the color of the suspension turned to from light green to yellow. The solution was taken to the dryness. The product was extracted with ethyl ether (4 × 25 cm3) and filtered through Celite. Partial evaporation of the volatiles produced a bright yellow microcrystalline solid, 6 (0.55 g, 93%). δP (162 MHz; C6D6, H3PO4) 62.1 (s, Et2PCH2CH2PEt2), δC (100 MHz; C6D6, C6D6) 2.81 (dd, JPC 76.3, JP′C 20.2, Ni-CH3), δH (400 MHz; C6D6, C6D6) 0.48 (3 H, dd, JPH 10.4, JP′H 4.4, Ni-CH3); d 0.91 (12 H, m (CH3CH2)2P), 1.00 (4 H, dd, JPH 8.0, JP′H 3.2, Et2PCH2-) d 1.26, 1.51 (4 H, m, (CH3CH2)2).

(depe)Ni(Me)(SPh), 7

A solution of thiophenol (70 μL, 0.68 mmol) in ethyl ether (5 cm3) was added dropwise to a solution of 6 (0.290 g, 1.0 mmol) in ethyl ether (20 cm3) at −78 °C. The mixture was stirred for two hours while the temperature gradually increased to ambient temperature. The mixture was taken into dryness and washed with cold pentane (50 cm3). The solid was dissolved in ethyl ether (20 cm3). Slow evaporation of the volatiles produced an orange crystalline solid, 7 (0.160 g, 60%). X-ray quality yellow crystals were obtained from slow evaporation of ethyl ether. Mp, 98 − 100 °C (ethyl ether) (decomposed) (Found: C, 53.3; H, 8.2. C17H32NiP2S requires C, 52.5; H, 8.3%), δP (162 MHz; C6D6, H3PO4) 66.6, 58.8 (d, JPP′ 15.3), δC (100 MHz; C6D6, C6D6) 0.70 (dd, JPC 65.0, JP′C 31.7, Ni-CH3), δH (400 MHz; C6D6, C6D6) 0.11 (3 H, dd, JPH 7.4 and JP′H 4.2, Ni-CH3), 0.82 (8 H, m), 1.04 (10 H, m), {(C2H5)2PCH2CH2P(C2H5)2}, 1.33, 1.68 (m), {(C2H5)2PCH2CH2P(C2H5)2}, 7.03 (1 H, t, 7.0, p-SC6H5), 7.17 (2 H, d, 7.6, m-SC6H5), 7.93 (2 H, d, 7.6, o-SC6H5).

(depe)Ni(Me)(SC6F5), 8

A solution of C6F5SH (200 μL, 1.5 mmol) in ethyl ether (10 cm3) was added dropwise to a solution of 6 (0.600 g, 2.03 mmol) in ethyl ether (20 cm3) at −78 °C. The mixture was stirred for two hours while the temperature gradually increased to ambient temperature. The resulting yellow solid was precipitated following the addition of pentane and subsequently washed with additional pentane (3 × 20 cm3). The solid was dried under vacuum overnight giving 8 (0.431 g, 60%) as a yellow solid. Yellow crystals were obtained from slow evaporation of ethyl ether. Mp, 120 – 122 °C (ethyl ether) (decomposed) (Found: C, 43.4; H, 5.5. C17H27NiP2SF5 requires C, 42.6; H, 5.7%). δP (162 MHz; C6D6, H3PO4) 59.4, 68.8 (d, JPP′ 17.7); δC (100 MHz; C6D6, C6D6) -0.73 (dd, JPC 65.1, JP′C 30.5, Ni-CH3), δH (400 MHz; C6D6, C6D6) - 0.26 (3 H, dd, JPH 6.6, JP′H 4.2, Ni-CH3), 1.62 (m), 1.30 (m) {(C2H5)2PCH2CH2P(C2H5)2}; 0.77 (m), 1.02 (m) {(C2H5)2PCH2CH2P(C2H5)2}.

(depe)Ni(Me)(o-pabt), 9

A solution of o-pabd (0.430 g, 1.03 mmol) in THF (10 cm3) was added dropwise to a solution of 6 (0.475 g, 1.6 mmol) in THF (20 cm3). The mixture was stirred for four hours. The volatiles were removed under vacuum and the solid was washed with ethyl ether (4 × 20 cm3). The product, 9 (0.400 g, 88%), was obtained as a yellow solid. Orange-yellow crystals were obtained from ethyl ether diffusion to a concentrated THF solution. Mp, 166 – 168 °C (THF/ethyl ether) (decomposed) (Found: C, 54.62, H, 8.27, N, 2.91; C22H41NiP2SNO: required C, 54.1, H, 8.5, N, 2.9%), νmax(KBr)/cm−1 3282 (NH) and 1670 (CO); νmax(THF)/cm−1 3283 (NH) and 1676 (CO); δP (162 MHz; C6D6, H3PO4) 57.4, 66.4 (d, JPP 13.7); δC (100 MHz; C6D6, C6D6) 1.08 (dd, JPC 61.0, JP′C 29.9, Ni-CH3), δH (400 MHz; C6D6, C6D6) -0.10 (3 H, dd, JPH 7.0, JP′H 3.9, Ni-CH3), 1.45 (s, tBu), 0.75 (m), 0.86 (m), 0.96 (m), 1.26 (m) {(C2H5)2P-CH2CH2-P(C2H5)2}; 0.77 (m), δ 1.02 (m) {(C2H5)2P-CH2CH2-P(C2H5)2}, 10.02(s, NH).

(depe)Ni(Me)(p-pabt), 10

A solution of p-pabd (0.280 g, 0.67 mmol) in THF (10 cm3) was added drop-wise to a solution of 6 (0.295 g, 1.0 mmol) in THF (20 cm3). The mixture was stirred for four hours. The volatiles were removed under vacuum and the solid was washed with ethyl ether (3 × 20 cm3). The product, 10 (0.312 g, 95%) was obtained as a yellow solid. Orange crystals were obtained from slow evaporation of a concentrated THF solution. Mp, 150 – 152 °C (THF/ethyl ether) (decomposed) (Found: C, 54.4, H, 8.5, N, 2.9; C22H41NiP2SNO: required C, 54.1, H, 8.5, N, 2.9%), νmax(KBr)/cm−1 3324 (m, NH) and 1661 (s, CO); νmax(THF)/cm−1 3360 (NH) and 1679 (CO); δP (162 MHz; C6D6, H3PO4) 59.0, 66.3 (d, JP-P 14.8), δC (100 MHz; C6D6, C6D6) 0.99 dd, JPC 62.2, JP′C 29.2, Ni-CH3), δH (400 MHz; C6D6, C6D6) 0.12 (3 H, dd, JPH 7.3, JP′H 4.2, Ni-CH3), 1.0 (s, tBu), 0.83 (m, 9H), 1.04 (m, 8H), 1.34 (m, 4H), 1.68 (m, 2H) {(C2H5)2PCH2CH2P(C2H5)2}, 6.76 (s, NH), 7.52 (2 H, d, JPH 8.30, o-(C6H4)S), 7.86 (2 H, d, JPH 8.30, m-(C6H4)S).

Thiolate Exchange

Complexes 2 and 7 (0.2 mmol each) were dissolved in equal volumes of C6D6 and mixed in an NMR tube. 31P NMR and 1H NMR spectra were recorded at ambient temperature against an external standard (H3PO4 in D2O), confirming the presence of the four different species, 2, 3, 7, and 8. Keq was determined via 31P NMR signal integration vs. the external standard. Equilibrium was also achieved by mixing 3 and 8 in an analogous fashion.

Sequential CO addition to 3, 4, 7-10

0.02 mmol of the methylnickel complex was dissolved in THF (1.0 mL) and transferred to a NMR tube. An external standard (H3PO4 in THF) in a sealed capillary tube was inserted into the NMR tube, which was then sealed with a rubber septum. The contents of the NMR tube were frozen in liquid nitrogen and the air in the headspace was evacuated under vacuum. After warming −78 °C, initial 31P NMR spectra were recorded at 202 K. Aliquots of dry CO (0.01 mmol, 220 μL) (passed through (i) a 0.1M solution of alkaline pyrogallol contained in a U-tube at −78 °C, and (ii) a tube of Drierite desiccant) were added to the NMR tube at −78 °C using a gas tight syringe. Signal integrations were normalized to the external standard.

Addition of MeC(O)SC6F5 to (dRpe)Ni(COD)

Preparative scale reaction: dppe (0.08 g, 0.2 mmol) in toluene (10 cm3) was added dropwise to a toluene solution of Ni(COD)2 (0.055 g, 0.2 mmol) at −78 °C. Then, a toluene solution of MeC(O)SC6F5 (0.048 g, 0.2 mmol) was added to the orange-yellow reaction mixture at −78 °C. The reaction mixture was stirred at −78 °C for two hours and subsequently at ambient temperature. The solvent was removed under vacuum, and the solid was dried under vacuum overnight. The product mixture was obtained as a yellow solid (0.094 g, 70 %). The 31P NMR spectra in C6D6 revealed that the product is a mixture of 46 % Ni(dppe)2 and 40% (dppe)Ni(Me)(SC6F5) and 14% (dppe)Ni(CO)2. Alternatively, reactions were performed under similar conditions in situ in an NMR tube as follows: A solution of dRpe (0.02 mmol) in THF (0.5 cm3) was added to a THF solution (0.5 cm3) of Ni(cod)2 (0.02 mmol) in a NMR tube containing an external standard (0.02M H3PO4 in D2O) in a sealed capillary at −78 °C. Then, a THF solution (0.5 cm3) of MeC(O)SAr (0.02 mmol) was added via syringe. The 31P NMR spectra recorded at room temperature revealed, in addition to the (dRpe)Ni(Me)(SAr), byproducts- (dRpe)2Ni, (dRpe)Ni(CO)2 with (dRpe)Ni(SAr)2.

Percent spectroscopic yields of (dRpe)Ni(Me)(SAr) in NMR scale reactions.

| dppe | depe | |

| CH3COSPh | 7 % | 50 % |

| CH3COSC6F5 | 37 % | 62 % |

Density Functional Theory Computations

Computational models of 9 and 10 were constructed based on crystallographic coordinates. The models were optimized in Gaussian0337 using the BP86 functional in the gas phase with Ahlrich's triple-ζ with polarization (TZVP) basis set on Ni, P, and S and split valence with polarization (SVP) on O, N, C, and H. The calculations were performed with a fine integration grid and tight SCF cutoffs to reduce numerical noise as restricted singlets, except in the cases of 5-coordinate species, which were calculated within the unrestricted formalism as triplets. To ensure stationary points on the models respective potential energy surfaces had been reached and to provide thermal corrections, analytical frequency calculations were performed yielding no imaginary frequencies. Single point calculations were then performed on the optimized coordinates using the hybrid functional B3LYP and TZVP basis set on all atoms to provide accurate energetics. An ultrafine integration grid and tight SCF cutoffs were employed. The single point calculations included CPCM to account for solvation effects. The solvent parameters chosen were those of THF. Final energies are the sum of the thermal parameters at 298.15K from the analytical frequency calculations and the solvation corrected SCF energy from the hybrid single point calculations (ETOTAL = EB3LYP + ESOLV + ETHERM − TS). Mulliken population analysis was performed using QMForge.38

X-ray Structural Solution and Refinement

Data were collected on a Bruker-AXS APEX diffractometer equipped with graphite monochromated Mo Kα radiation (λ = 0.7107 Å). The unit cell parameters and orientation matrices were determined by gathering reflections from three sets of 15-20 frames using 0.3° ω scans. The systematic absences, together with the unit cell parameters, in the diffraction data are uniquely consistent with the reported space groups. All structure factors, anomalous dispersion coefficients, and the applied SADABS absorption correction program are contained in various versions (5.1 - 6.12) of SHELXTL program library.39 Two symmetry unique but chemically identical molecules of 7 were located in the asymmetric unit. Compounds 2 and 4 display level B alerts in checkCIF (http://checkcif.iucr.org) for failing the Hirshfeld test for Ni–S and Ni–P, respectively, however there is no ambiguity as to atom identities based on synthesis. Compound 9 displays level A and B alerts which are attributable to the high thermal activity of the molecule. Attempts to collect diffraction data below 290 K for 9 failed because of an irreversible phase change. The structure of (dppe)Ni(CO)2, a known compound,40 is reported in the electronic supplementary information (ESI). The absolute structure parameter of (dppe)Ni(CO)2 refined to nil indicating the true hand of the data was established. The carbon atoms in the ethylene backbone of dppe are disordered and were not stable to anisotropic refinement. All other non-hydrogen atoms were anisotropically refined using the conventional full-matrix least-squares method. All hydrogen atoms were treated as idealized contributions. The CIFs are available from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre under the depositary numbers CCDC 716709 – 716717.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

These studies were supported by the NIH (GM59191). Computational resources used in these studies were provided in part by the Bioinformatics Center of the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (NIH Grant P20 RR-16460 from the IDeA Networks of Biomedical Research Excellence (INBRE) Program of the National Center for Research Resources) and the in part by the National Science Foundation through TeraGrid resources provided by the NCSA (TG-CHE080054N).

References

- 1.Ragsdale SW. J Inorg Biochem. 2007;101:1657–1666. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2007.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lindahl PA, Graham DE. Acetyl-Coenzyme A Synthases and Nickel-Containing Carbon Monoxide Dehydrogenases. In: Sigel HSA, Sigel RKO, editors. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 2. Wiley; Chichester, UK: 2007. pp. 357–416. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hugler M, Huber H, Stetter KO, Fuchs G. Arch Microbiol. 2003;179:160–173. doi: 10.1007/s00203-002-0512-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Juan B, Thauer RK. Methyl-Coenzyme M Reductase and Its Nickel Corphin Coenzyme F430 in Methanogenic Archaea. In: Sigel HSA, Sigel RKO, editors. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 2. Wiley; Chichester, UK: 2007. pp. 323–356. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doukov TI, Iverson TM, Seravalli J, Ragsdale SW, Drennan CL. Science. 2002;298:567–572. doi: 10.1126/science.1075843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Darnault C, Volbeda A, Kim EJ, Legrand P, Vernede X, Lindahl PA, Fontecilla-Camps JC. Nat Struct Biol. 2003;10:271–279. doi: 10.1038/nsb912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Svetlitchnyi V, Dobbek H, Meyer-Klaucke W, Meins T, Thiele B, Romer P, Huber R, Meyer O. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:446–451. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0304262101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lindahl PA. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2004;9:516–524. doi: 10.1007/s00775-004-0564-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ragsdale SW. Chem Rev. 2006;106:3317–3337. doi: 10.1021/cr0503153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tan X, Martinho M, Stubna A, Lindahl PA, Münck E. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:6712–6713. doi: 10.1021/ja801981h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Golden ML, Rampersad MV, Reibenspies JH, Darensbourg MY. Chem Commun. 2003:1824–1825. doi: 10.1039/b304884p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Rao PV, Bhaduri S, Jiang J, Holm RH. Inorg Chem. 2004;43:5833–5849. doi: 10.1021/ic040055s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Wang Q, Blake AJ, Davies ES, McInnes EJL, Wilson C, Schröder M. Chem Commun. 2003:3012–3013. doi: 10.1039/b310183e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Hatlevik Ø, Blanksma MC, Mathrubootham V, Arif AM, Hegg EL. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2004;9:238–246. doi: 10.1007/s00775-003-0518-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Duff SE, Barclay JE, Davies SC, Evans DJ. Inorg Chem Commun. 2005;8:170–173. [Google Scholar]; Harrop TC, Olmstead MM, Mascharak PK. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:14714–14715. doi: 10.1021/ja045284s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krishnan R, Voo JK, Riordan CG, Zakharov L, Rheingold AL. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:4422–4423. doi: 10.1021/ja0346577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Krishnan R, Riordan CG. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:4484–4485. doi: 10.1021/ja038086u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eckert NA, Dougherty WG, Yap GPA, Riordan CG. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:9286–9287. doi: 10.1021/ja072063o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dougherty WG, Rangan K, O'Hagan MJ, Yap GPA, Riordan CG. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:13510–13511. doi: 10.1021/ja803795k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Osterloh F, Saak W, Pohl S. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:5648–5656. [Google Scholar]; Laplaza CE, Holm RH. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:10255–10264. doi: 10.1021/ja010851m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Rao PV, Bhaduri S, Jiang J, Hong D, Holm RH. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:1933–1945. doi: 10.1021/ja040222n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ram MS, Riordan CG. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:2365–2366. [Google Scholar]; Ram MS, Riordan CG, Yap GPA, Liable-Sands L, Rheingold AL, Marchaj A, Norton JR. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:1648–1655. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim YJ, Osakada K, Sugita K, Yamamoto T, Yamamoto A. Organometallics. 1988;7:2182–2188. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stavropoulos P, Muetterties MC, Carrie M, Holm RH. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:8485–8492. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tucci GC, Holm RH. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:6489–6496. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matsunaga P, Hillhouse GL. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1994;33:1748–1749. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sellmann D, Häussinger D, Knoch F, Moll M. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:5368–5374. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Webster CE, Darensbourg MY, Lindahl PA, Hall MB. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:3410–3411. doi: 10.1021/ja038083h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith JN, Shirin Z, Carrano CJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:868–869. doi: 10.1021/ja029418i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Morlok MM, Janak KE, Zhu G, Quarless DA, Parkin G. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:14039–14050. doi: 10.1021/ja0536670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chiou S, Riordan CG, Rheingold AL. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:3695–3700. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0637221100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ragsdale SW. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;39:165–195. doi: 10.1080/10409230490496577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ragsdale SW, Wood HG. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:3970–3977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.5 was prepared via both routes; the material synthesized using ArSH was more readily purified.

- 26.Gallo EA, Gellman SH. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:9774–9788. [Google Scholar]; Nesloney CL, Kelly JW. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:5836–5845. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Komiya S, Yamamoto A, Yamamoto T. Chem Lett. 1981;193 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Campora J, Lopez JA, Maya C, Palma P, Carmona E, Valerga P. J Organomet Chem. 2002:643–644. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anderson GK, Cross RJ. Acc Chem Res. 1984;17:67–74. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hartwig JF. Acc Chem Res. 1998;31:852–860. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shimizu T, Seki M. Tet Lett. 2002;43:1039–1042. [Google Scholar]

- 32.O'Brien EM, Bercot EA, Rovis T. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:10498–10499. doi: 10.1021/ja036290b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lindahl PA. Biochemistry. 2002;41:2097–2105. doi: 10.1021/bi015932+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ueno T, Inohara M, Ueyama N, Nakamura A. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 1997;70:1077–1083. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaschube W, Pörschke KR, Wilke G. J Organomet Chem. 1988;355:525–532. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Green MLH, Smith MJ. J Chem Soc A. 1971:639–641. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gaussian 03 RC, Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Montgomery JA, Jr, Vreven T, Kudin KN, Burant JC, Millam JM, Iyengar SS, Tomasi J, Barone V, Mennucci B, Cossi M, Scalmani G, Rega N, Petersson GA, Nakatsuji H, Hada M, Ehara M, Toyota K, Fukuda R, Hasegawa J, Ishida M, Nakajima T, Honda Y, Kitao O, Nakai H, Klene M, Li X, Knox JE, Hratchian HP, Cross JB, Bakken V, Adamo C, Jaramillo J, Gomperts R, Stratmann RE, Yazyev O, Austin AJ, Cammi R, Pomelli C, Ochterski JW, Ayala PY, Morokuma K, Voth GA, Salvador P, Dannenberg JJ, Zakrzewski VG, Dapprich S, Daniels AD, Strain MC, Farkas O, Malick DK, Rabuck AD, Raghavachari K, Foresman JB, Ortiz JV, Cui Q, Baboul AG, Clifford S, Cioslowski J, Stefanov BB, Liu G, Liashenko A, Piskorz P, Komaromi I, Martin RL, Fox DJ, Keith T, Al-Laham MA, Peng CY, Nanayakkara A, Challacombe M, Gill PMW, Johnson B, Chen W, Wong MW, Gonzalez C, Pople JA. Gaussian Inc. Wallingford CT: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tenderholt, Adam L. QMForge: A Program to Analyze Quantum Chemistry Calculations. Version 2.1 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sheldrick GM. Acta Cryst A. 2008;64:112–122. doi: 10.1107/S0108767307043930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tanaka K, Kawata Y, Tanaka T. Chem Lett. 1974:831–832. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.