Abstract

Background

Physical activity is associated with reductions in fatigue in breast cancer survivors. However, mechanisms underlying this relationship are not well understood. The purpose of this study was to longitudinally test a model examining the role of self-efficacy and depression as potential mediators of the relationship between physical activity and fatigue in a sample of breast cancer survivors using both self-report and objective measures of physical activity.

Methods

All participants (N= 1527) completed self-report measures of physical activity, self-efficacy, depression and fatigue at baseline and 6 months. A subsample was randomly selected to wear an accelerometer at both time points. It was hypothesized that physical activity indirectly influences fatigue via self-efficacy and depression. Relationships among model constructs were examined over the 6 month period using panel analysis within a covariance modeling framework.

Results

The hypothesized model provided a good model-data fit (X2 = 599.66, df = 105, p = < 0.001; CFI= 0.96; SRMR= 0.02) in the full sample when controlling for covariates. At baseline, physical activity indirectly influenced fatigue via self-efficacy and depression. These relationships were also supported across time. Additionally, the majority of the hypothesized relationships were supported in the subsample with accelerometer data months (χ2 = 387.48, df = 147, p = <0.001, CFI = 0.94, SRMR= 0.04).

Conclusions

This study provides evidence to suggest the relationship between physical activity and fatigue breast cancer survivors may be mediated by more proximal, modifiable outcomes of physical activity participation.

Impact

Recommendations are made relative to future applications and research concerning these relationships.

Keywords: physical activity, fatigue, self-efficacy, breast cancer survivors

Introduction

An estimated 70% to 99% of breast cancer patients experience cancer-related fatigue during treatment [1]. In addition, emerging evidence indicates that fatigue may not necessarily diminish post-treatment with15% to 50%, or more, of breast cancer survivors reporting fatigue post-treatment [2-4]. Bower and colleagues reported that 5-10 years post-diagnosis, 34% of women experienced fatigue, and 21% of women had fatigue that persisted 1-5 years post diagnosis and 5-10 years post-diagnosis [5]. In addition to persistent fatigue, some breast cancer survivors may experience a delayed onset of fatigue symptoms [2]. Fatigue has been associated with a host of negative outcomes including the inability to lead a ‘normal” life, inability to maintain pre-cancer daily routines, changes in employment status, reduced quality of life, impaired cognitive functioning and higher levels of bodily pain, menopausal symptoms (e.g. night sweats and hot flashes), comorbid conditions, depression, and fear of recurrence [5-7]. Women who are treated with a combination of chemotherapy and radiation appear to be at higher risk than women treated with radiation therapy or chemotherapy, alone [5]. As the breast cancer survivor population continues to grow, understanding the mechanisms underlying fatigue is important in order to identify areas for intervention in order to enhance quality of life and disease-free survivorship.

Fatigue is a multi-dimensional state with multiple causes making the underlying mechanisms challenging to identify [8]. Five categories of factors believed to contribute to cancer related fatigue have been identified: psychosocial mechanisms, exacerbating comorbid symptoms, comorbid medical conditions, treatment side effects and direct effects of tumor and cancer burden [8-10]. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommends a two stage approach to cancer related fatigue management [8]. The first is to identify and address any treatable factors that may contribute to fatigue while the second is to manage any residual fatigue. Physical activity has been identified as one potential nonpharmacological intervention which can help ameliorate fatigue in both stages [8], and an extensive body of literature exists which suggests that physical activity may be particularly effective for reducing fatigue in breast cancer survivors [11-13]. However, the mechanisms by which physical activity exerts its effect on fatigue are not well understood. Several factors have been proposed to influence this relationship including changes in biological and physiological parameters such as c-reactive protein [14], cortisol [15]and reductions in activated T-cells [16] as well as changes in psychosocial variables [17] resulting from physical activity participation.

In order to enhance the understanding of the mechanisms underlying the relationship between physical activity and fatigue, McAuley and colleagues tested a psychosocial model of physical activity and fatigue cross-sectionally in a small sample of rural breast cancer survivors within 5-years of diagnosis [17]. They hypothesized that physical activity influences fatigue in breast cancer patients via more proximal outcomes of physical activity participation: self-efficacy and depression. The rationale for this model was based on the following: 1) Increased self-efficacy is one of the most consistent outcomes of physical activity participation [18], has been shown to mediate the effects of behavior on depression levels [19, 20], and has been inversely associated with fatigue levels in breast cancer survivors [21] and other chronic disease populations [22]; 2) fatigue and depression frequently co-occur in breast cancer survivors[4, 23] and 3) fatigue is considered a clinical symptom of depression [24] and emerging longitudinal evidence in breast cancer survivors suggests that post-treatment depression is predictive of fatigue at later time points even when controlling for baseline post-treatment fatigue levels [5, 25].

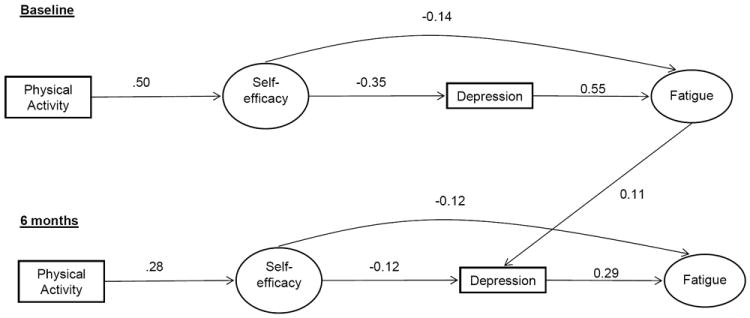

The purpose of the present study was to determine whether the relationships proposed in McAuley and colleagues’ cross-sectional psychosocial model of physical activity and fatigue could be confirmed longitudinally in a nationwide sample of breast cancer survivors that is more heterogeneous, in time since diagnosis, disease stage, age, and treatment status, as well as geographically. Specifically, we hypothesized that changes in physical activity participation over the 6-month period would be indirectly associated with changes in fatigue via changes in exercise self-efficacy which would, in turn both directly and indirectly, via changes in depression, influence changes in fatigue (See Figure 1). Replicating this model longitudinally provides a better understanding of the temporal nature of potential underlying psychosocial mechanisms of fatigue and informs the design of physical activity interventions for breast cancer survivors.

Figure 1.

Panel model depicting the psychosocial model of fatigue in the full sample at baseline and 6 months.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Women over the age of 18 yrs who had been diagnosed with breast cancer, were English-speaking and had access to a computer were eligible to participate in the present study.

Measures

Demographics

Self-reported marital status, age, race, ethnicity, occupation, income, and education were collected.

Health and cancer history

Participants were asked to indicate (yes or no) whether or not they have been diagnosed with a list of 18 different comorbidities (i.e. diabetes, obesity, hypertension) and summed to obtain a total number of comorbidities, and to self-report information regarding their breast cancer (i.e. stage of disease, time since diagnosis in months, treatment regime) and other cancer history. Current height and weight were also self-reported to estimate body mass index (BMI) using the standard kg/m2 equation [26].

Godin Leisure Time Exercise Questionnaire [27]

Participants were asked to self-report the frequency of their current participation in strenuous (e.g., jogging), moderate (e.g., fast walking), and mild (e.g., easy walking) exercise over the past seven days, and these frequencies were multiplied by 9, 5, and 3 metabolic equivalents, respectively, and summed to form a measure of total leisure time activity.

Actigraph accelerometer (model GT1M, Health One Technology, Fort Walton Beach, FL)

The Actigraph, a valid and reliable objective physical activity measure [28, 29], was used to measure physical activity in a random subsample of the study population. These women were instructed to wear the monitor for seven consecutive days on the non-dominant hip during all waking hours, except for when bathing or swimming. Activity data was collected in one-minute intervals (epochs). A valid day of accelerometer wear was defined as wearing the monitor for 10 hours with no more than 30 minutes of consecutive zero-values. The total number of counts for each valid day was summed and divided by the number of days of monitoring to arrive at an average number of activity counts. Only data for individuals with a minimum of 3 valid days of wear time at both time points were included in analyses [30].

Self-efficacy

The 6-item Exercise Self-Efficacy Scale [31] was used to assess participants’ beliefs in their ability to exercise five times per week, at a moderate intensity, for 30 or more minutes per session at two week increments over the next 12 weeks. The 15-item Barriers Self-Efficacy Scale [31] assessed participants’ perceived capabilities to exercise three times per week for 40 minutes over the next two months in the face of common barriers to participation. Items from each scale are scored on a 100-point percentage scale with 10-point increments, ranging from 0% (not at all confident) to 100% (highly confident). For each measure, total scores were calculated using the average confidence rating. The reliability was excellent at baseline (α= 0.99; α= 0.95) and follow-up (α= 0.95; α= 0.99) for exercise self-efficacy and barriers self-efficacy, respectively

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-Depression Subscale [32]

The 7-item depression subscale assessed the frequency of depressive states over the past week on a 4-point Likert scale from 0 (not at all) to 3 (most of the time). Positively worded items were reverse scored and then all individual item scores were summed to achieve a total depression score ranging from 0 to 21 with higher scores indicating greater levels of depression. This scale has well-established psychometric properties. The reliability was acceptable at baseline (α= 0.83) and follow-up (α= 0.84).

Fatigue Symptom Inventory [33]

This scale was used to assess the severity, frequency, and diurnal variation of fatigue, and its perceived interference with quality of life. The reliability was acceptable at baseline (α= 0.89; α= 0.94; α= 0.77) and 6 months (α= 0.91; α= 0.95; α= 0.81) for the severity, interference, and duration subscales, respectively.

Randomization

All study procedures and recruitment materials were approved by the university institutional review board. Participants were recruited via an Army of Women© “e-blast”, University e-mail, fliers, print media, and on-line community groups and postings. All women (N = 2546) expressing an initial interest in study participation were e-mailed a link to a full description of the study. All breast cancer survivors who met eligibility criteria were extended an offer to participate and sent an electronic version of the informed consent which participants completed for proceeding with randomization. Of those women who responded to the initial study description e-mail and qualified for participation (N = 1631), a sub-group of individuals (n=500) were completely randomly assigned to wear an accelerometer using a pre-populated computer algorithm for 7 days at baseline and 6 months. At 6-month follow-up, 1527 women completed all survey data and 370 had valid accelerometer data at both time points.

Data Collection

Women randomized to the survey only group were sent an individualized secure link to the study questionnaires. Women randomized to wear the accelerometer were sent a link to the study questionnaires on the day their study packet containing an accelerometer, related study materials and a self-addressed stamped envelope was mailed. All participants were instructed to return study materials within two weeks of receipt. Reminder e-mails for surveys were sent on a bi-weekly basis until questionnaires were complete or participants had been contacted three times, whichever came first. Women were reminded to return accelerometers until they were received by study investigators. Identical procedures were followed for both groups at 6 months.

Data Analysis

To examine the hypothesized relationships, panel analyses within a covariance framework were conducted in Mplus V6.0 [34]. Panel models are ideally suited to the analysis of hypothesized, theoretically-based relationships. This approach allowed for the examination of the hypothesized relationships at baseline and those same relationships among changes in the constructs at 6 months controlling for all other variables in the model. We conducted two separate panel analyses. The first tested the hypothesized model in all study participants whereas the second tested the hypothesized model in the accelerometer subgroup only. Age, education, income, body mass index, number of comorbidities, time since diagnosis and stage of disease were controlled for in each of the analyses.

The robust full-information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimator was used in the present study [35-37] as a result of preliminary analyses indicating missing data were missing at random (MAR). The extent of missing data ranged from 7.8% (barriers self-efficacy scale) to 14.1% (physical activity) at baseline. Missing data at 6-months ranged from 24.7% (exercise self-efficacy) to 27.3% (depression), and was largely the result of loss to follow-up.

The following hypothesized relationships were tested: (a) a direct path from physical activity to exercise self-efficacy; (b) a direct path from exercise self-efficacy to depression; (c) a direct path from exercise self-efficacy to fatigue and (d) a direct path from depression to fatigue. Exercise self-efficacy was measured as a latent construct using the total scores from the Barrier Self-efficacy Scale and the Exercise Self-Efficacy Scale as indicators. Fatigue was also modeled as a latent construct using the total scores from each of the subscales (interference, duration, and severity) as indicators. Physical activity was modeled as a latent construct with the GLTEQ total score and average accelerometer counts as indicators in the accelerometer subsample. Stability coefficients were calculated to reflect correlations between the same variables across time while controlling for the influence of all other variables in the model [38]. In addition, the modification indices were examined for other potential relationships among model constructs and potential reciprocal relationships.

The chi-square statistic assessed absolute fit of the model to the data [39]. The standardized root means residual (SRMR) and Comparative Fit Index46 (CFI) were also used to determine the fit of the model. SRMR values approximating 0.08 or less demonstrate close fit of the model [40, 41] while CFI values of .90 indicate a minimally acceptable fit value and values approximating 0.95 or greater are indicative of a good fit [40].

Results

Participant Characteristics

We recruited a nationwide sample of breast cancer survivors (M age= 56.2, SD = 9.4) as participants for this study. The majority of the women were white (97.0%) and non-Hispanic/Latino (98.5%). Two-thirds of the sample (67.0%) had at least a college degree, and 86.0% of the sample had an annual household income greater than or equal to $40,000. Data regarding self-reported comorbidities can be found in Table 1. Disease specific sample characteristics are presented in Table 2. Briefly, the average time since diagnosis was 86.48 (± 71.59) months and the majority of women were diagnosed with ductal carcinoma in situ (19.9%) or early stage disease (63.7% stage I or stage II). The majority of women were also no longer receiving active treatment (chemotherapy or radiation) for breast cancer (96.8%)

Table 1.

Sample Baseline Demographics

| Characteristic | Total Sample (N= 1527) M (SD) | Accel Group (n= 370) M (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Age | 56.18 (9.41) | 56.50 (9.33) |

| Body Mass Index | 26.57 (5.74) | 25.90 (5.14) |

| Race | ||

| White | 97.0% | 96.7% |

| Asian | 0.6% | 1.1% |

| African American | 1.6% | 0.8% |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 0.7% | 1.1% |

| Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander | 0.1% | 0.3% |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic/Latino | 1.5% | 1.9% |

| Not Hispanic/Latino | 98.5% | 98.1% |

| Education | ||

| < College Education | 33.0% | 33.9% |

| ≥ College Education | 67.0% | 66.1% |

| Marital Status | ||

| Married | 72.6% | 75.1% |

| Divorced/Separated | 10.5% | 10.4% |

| Partnered/Significant Other | 5.1% | 5.2% |

| Single | 6.7% | 5.2% |

| Widowed | 5.1% | 4.1% |

| Employment Status | ||

| Full-time | 37.5% | 36.7% |

| Retired, not working at all | 26.3% | 28.8% |

| Part-time | 14.6% | 14.9% |

| Retired, working part-time | 7.4% | 7.3% |

| Full-time homemaker | 6.4% | 4.6% |

| Laid off/unemployed | 4.0% | 3.8% |

| Disabled | 1.6% | 1.6% |

| Self-employed | 1.0% | 1.1% |

| Student | 0.7% | 0.8% |

| Other | 0.6% | 0.3% |

| Income | ||

| < $40,000 | 14.0% | 12.6% |

| ≥ $40,000 | 86.0% | 87.4% |

| Health Conditions | ||

| Arthritis | 33.4% | 33.5% |

| Osteoporosis | 18.9% | 16.6% |

| Asthma | 10.3% | 9.7% |

| COPD, ARDS or Emphysema | 2.3% | 2.5% |

| Angina | 0.6% | 0.8% |

| Congestive Heart Failure/Heart Disease | 1.9% | 3.0% |

| Heart Attack | 0.4% | 0.6% |

| Stroke/TIA | 1.7% | 1.4% |

| Neurological Disease | 1.0% | 0.0% |

| PVD | 1.2% | 1.4% |

| Diabetes | 6.3% | 5.2% |

| Depression | 20.7% | 22.8% |

| Anxiety or Panic Disorder | 14.4% | 14.4% |

| Degenerative Disc Disease | 13.4% | 13.9% |

| Obesity | 17.6% | 14.6% |

| Upper GI Disease | 17.7% | 13.8% |

Table 2.

Sample Breast Cancer Specific Health History/Characteristics

| Characteristic | Total Sample (n = 1527) M (SD) | Accel Group (n= 370) M (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis | 49.42 (8.99) | 49.74 (8.96) |

| Time Since Diagnosis (months) | 86.48 (71.59) | 85.82 (65.46) |

| Breast Cancer Stage | ||

| 0/DCIS | 19.9% | 17.9% |

| 1 | 31.1% | 30.4% |

| 2 | 32.6% | 33.6% |

| 3 | 10.0% | 11.1% |

| 4 | 2.1% | 2.2% |

| Don’t Know | 4.3% | 4.9% |

| Estrogen Receptor Positive | 70.3% | 70.8% |

| Current Treatment Status | ||

| Chemotherapy | 2.6% | 2.2% |

| Radiation | 0.6% | 0.0% |

| Breast Cancer-Related Drug Therapy | 43.0% | 43.2% |

| Post-menopausal at diagnosis | 49.2% | 44.3% |

| Post-menopausal | 83.6% | 86.8% |

| Treatment History | ||

| Surgery | 99.3% | 99.7% |

| Chemotherapy | 59.0% | 60.5% |

| Radiation Therapy | 67.7% | 68.8% |

| Breast Cancer Recurrence | 10.7% | 11.1% |

| Any Other Cancer Diagnosis | 15.2% | 14.9% |

| Family History of Breast Cancer | 51.0% | 53.7% |

Model Results

Table 3 contains the means, standard deviations, and t-values for each of the factors in the physical activity and fatigue model. Briefly, over the six month study period, women experienced a significant (p < 0.05) decline in exercise self-efficacy, fatigue severity, fatigue interference, and physical activity. Fatigue duration significantly increased while barriers self-efficacy and depression did not change over the 6-month study period.

Table 3.

Descriptives of Fatigue Model at Baseline and 6 months

| Baseline | 6 months | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Variable | M | SD | M | SD | t-value | |

| Barriers Self-efficacy | 46.39 | 24.73 | 46.08 | 24.82 | -1.64 | |

| Exercise Self-efficacy | 72.06 | 33.33 | 69.11 | 35.05 | -5.33* | |

| Fatigue Severity | 3.41 | 1.96 | 3.00 | 2.06 | -6.98* | |

| Fatigue Interference | 1.88 | 1.93 | 1.64 | 1.92 | -4.11* | |

| Fatigue Duration | 2.79 | 2.05 | 2.93 | 2.14 | 4.35* | |

| Depression | 4.13 | 3.66 | 4.15 | 3.83 | -0.27 | |

| Self-reported Physical Activity | 30.47 | 21.87 | 29.64 | 21.86 | -2.15* | |

| Accelerometer Physical Activity | 25,2219.97 | 16,9805.00 | 21,2765.22 | 9,7755.46 | -4.96* | |

Note. All values listed are for the full sample (N= 1,527) except for the accelerometer data which is only for the 370 individuals with valid data

significant at p=<.05

Full sample

The best fitting model included the hypothesized paths and a correlation between barriers self-efficacy scale at baseline and follow-up, (X2 = 667.22, df = 110, p = < 0.001; CFI= 0.96; SRMR= 0.02). The modification indices indicated that a cross-lagged path between baseline fatigue and depression at 6 months could significantly improve the fit of the model. This model also provided an excellent fit to the data (X2 = 599.66, df = 105, p = < 0.001; CFI= 0.96; SRMR= 0.02). This model is shown in Figure 1. Overall, the stability coefficients were acceptable and ranged from 0.56 (fatigue) to 0.69 (self-efficacy). Bi-directional correlations and stability coefficients are omitted from the figure for clarity.

At baseline, breast cancer survivors who participated in more physical activity had significantly (p ≤ 0.001) higher exercise self-efficacy (β = 0.50). In turn, more efficacious breast cancer survivors had significantly lower levels of fatigue (β = -0.14) and depression (β = -0.35), and women who reported higher levels of depression reported higher levels of fatigue (β = 0.55). Additionally, the indirect paths from physical activity to fatigue via exercise self-efficacy, alone, and via exercise self-efficacy and depression were significant. Finally, fatigue at baseline was also significantly (p < 0.01) related to depression at 6 months (β = 0.11).

At 6-month follow-up, breast cancer survivors whose physical activity increased also had significant increases in exercise self-efficacy (β = 0.28). In turn, women who reported increases in self-efficacy, reported decreased levels of depression (β = -0.12) and fatigue (β = -0.12). Increased levels of depression were associated with increased fatigue levels (β = 0.29). There were statistically significant indirect paths between residual changes in physical activity and residual changes in exercise self-efficacy, alone, and via residual changes in both exercise self-efficacy and depression. Overall, the model accounted for 52.2% and 69.4% of the variance in fatigue at baseline and follow-up, respectively.

There were a number of significant (p< 0.05 relationships among model constructs and covariates. At baseline, older women reported higher levels of exercise self-efficacy (β = 0.12) and lower levels of physical activity, (β = -0.08), fatigue (β = -0.08) and depression (β = -0.20). In addition, reporting more comorbidities was associated with lower physical activity (β = -0.09) self-efficacy (β = -0.15) and higher levels of fatigue (β = 0.16) and depression (β = 0.20). Longer time since diagnosis was negatively associated with fatigue (β = -0.08) and depression (β = -0.07), and women diagnosed with more advanced disease stage reported lower levels of physical activity (β = -0.06) and exercise self-efficacy (β = -0.06) and higher levels of depression (β = 0.05). Higher BMI was associated with lower exercise self-efficacy (β = -0.15) and physical activity (β = -0.19), while higher education was associated with more physical activity participation (β = 0.12) and higher income was associated with higher exercise self-efficacy (β = 0.08). At 6 month follow-up, women who reported more advanced disease state at diagnosis (β = -0.05) and higher BMI (β = -0.11) also reported lower physical activity participation.

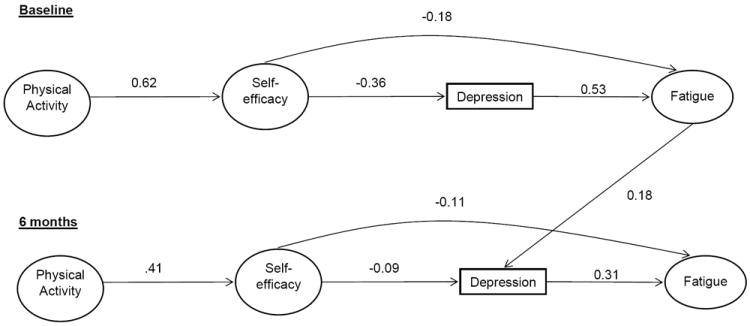

Accelerometer Subgroup

The best fitting model included the hypothesized paths and a correlation between the average accelerometer counts from baseline to 6 months (χ2 = 387.48, df = 147, p = <0.001, CFI = 0.94, SRMR= 0.04). Results from this model are shown in Figure 2 and are almost identical to those from the whole sample. Overall, this model accounted for 51.0% of the variance in fatigue at baseline and 71.1% of the variance for changes in fatigue across the 6-month period.

Figure 2.

Panel model depicting the psychosocial model of fatigue in the accelerometer subsample at baseline and 6 months.

Discussion

This study provides support in a national longitudinal sample for the psychosocial pathways underlying the relationship between physical activity and fatigue in breast cancer survivors proposed by McAuley and colleagues [17]. As hypothesized, the influence of physical activity on fatigue was indirect rather than direct, operating through the psychosocial factors of exercise self-efficacy and depression. The hypothesized relationships among changes in these constructs over a 6 month period were supported when controlling for baseline relationships and covariates. The findings from this study provide further support for the role of exercise self-efficacy, a proximal, modifiable outcome of physical activity participation as a potential mediator of the relationship between physical activity and fatigue.

Although physical activity has consistently been shown to be associated with a reduced risk of fatigue, very few studies have examined the mechanisms underlying this relationship. Self-efficacy may exert its influence on depression and fatigue via its impact on both psychological and biological processes. As a result of treatment-related side effects and cultural expectations of cancer survivors, women who are dealing with their identity as a cancer survivor may experience pain due to identifying with being “sick”, “sick behavior”, and physical and mental side effects of treatment [42]. This can set in motion a self-perpetuating process resulting in declines in cognitive and behavioral functioning [42]. Reductions or uncertainties about exercise self-efficacy may curtail physical activity participation and undermine any effort to maintain or increase physical activity levels which, may, in turn, result in a progressive loss of interest and skill leading to subsequent increases in depression and fatigue [42]. Experimental studies have shown that manipulating self-efficacy by providing false feedback based on physiological testing can influence affect in those individuals randomized into a high-efficacy condition reporting more positive well-being and reduced levels of psychological distress, fatigue and state anxiety during a single bout of activity than their low-efficacious counterparts [43-45]. Thus, prolonged physical activity participation may influence depression and fatigue through a sustained, additive effect. In addition, increased self-efficacy may impact depression and fatigue via its effect on breast cancer survivors’ feelings of controllability and the influence of controllability on stress and biomarkers associated with depression and fatigue [46-49].

While the findings from this study are promising, there are several limitations. First, the study population is relatively homogeneous. Most of the women are white, highly educated and high income. Thus, findings from this study may not be generalizable to all breast cancer survivors. Second, this study adopted a longitudinal observational design that spanned only a period of 6 months. While mean fatigue severity values exhibited statistically significant declines over the 6-month study period, on average, women still reported clinically significant fatigue severity values at follow-up (> 3) [50]. The change in average fatigue severity (-0.4) in the present study was similar to the difference exhibited between post-treatment breast cancer survivors and healthy controls (-0.6) in Donovan and colleagues study [50]. Furthermore, while participants in the present study exhibited similar average fatigue severity scores (M = 3.41) at baseline to those found in post-treatment breast cancer survivors (M=3.4) in Hann and colleagues study [32], the average fatigue severity value (M =3.0) at 6-month follow-up was closer in magnitude to that reported by healthy women (M= 2.8) in the Hann et al. study [33] indicating that these changes may be clinically meaningful. However, longitudinal studies with longer follow-up periods and randomized controlled exercise trials are necessary to determine whether model relationships hold across the survival spectrum, and change as a result of intervention as well to determine whether more definitive clinically significant changes in fatigue can be observed.

Because fatigue is a complex, multidimensional state that is influenced by numerous factors, future studies should examine the potential link between physical activity, self-efficacy, physiological and social parameters and fatigue. Furthermore, our findings suggest that the impact of self-efficacy on fatigue may change across time as the pathway coefficient decreased marginally from baseline to 6-months. However, this could be a result of the lack of an active intervention or a short study time period. Future studies should explore these relationships further to determine whether these relationships are invariant across time. In addition, our findings relative to the relationship between demographic factors and model constructs, suggest that some groups of breast cancer survivors may be particularly vulnerable including women diagnosed with more advanced disease, younger survivors, overweight or obese, and those with multiple comorbidities. Thus, this model and more comprehensive, complementary models should be tested in subgroups of breast cancer survivors and in other diseased populations to determine a) whether these relationships differ based on individual characteristics, b) whether these relationship vary across the cancer survival continuum and b) whether these relationships are reflective of pathways underlying fatigue in other cancer survivor and diseased populations. Furthermore, we chose to examine the effects of aggregate physical activity on fatigue in this study. Future studies should determine whether different doses (intensity and duration) as well as different modes of physical activity differentially influence these relationships in order to develop a better understanding of exactly what type of activities should be prescribed to maximize benefits.

In summary, this study remains one of the largest, nationally representative longitudinal studies of physical activity and fatigue in breast cancer survivors to date and is one of the few studies in this population which has incorporated an objective measure of physical activity participation. These data provide support for a psychosocial model of fatigue grounded in social-cognitive theory and provide evidence to support an important, modifiable pathway between physical activity and fatigue. Thus, it may be particularly important for physical activity interventions and programs targeted towards reducing fatigue in breast cancer survivors to be designed specifically to target sources of efficacy information. Future studies should seek to replicate, expand and refine this model to enhance the understanding of the relationship between physical activity and fatigue in order to not only help reduce the costs associated with treating fatigue and its negative side effects in breast cancer survivors and other cancer survivor populations, but potentially improve health outcomes and quality of life in this population.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support

This work was supported by award #F31AG034025 from the National Institute on Aging awarded to Siobhan M. (White) Phillips and a Shahid and Ann Carlson Khan endowed professorship awarded to Edward McAuley, who is also supported by grant #AG020118 from the National Institute on Aging. All work was conducted at the University of Illinois.

Footnotes

The authors have no financial disclosures or conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.de Jong N, Courtens AM, Abu-Saad HH, Schouten HC. Fatigue in patients with breast cancer receiving adjuvant chemotherapy: a review of the literature. Cancer Nurs. 2002;25:283–97. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200208000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andrykowski MA, Donovan KA, Laronga C, Jacobsen PB. Prevalence, predictors, and characteristics of off-treatment fatigue in breast cancer survivors. Cancer. 2011;116:5740–48. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim SH, Son BH, Hwang SY, Han W, Yang JH, Lee S, et al. Fatigue and depression in disease-free breast cancer survivors: prevalence, correlates, and association with quality of life. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35:644–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Okuyama T, Akechi T, Kugaya A, Okamura H, Imoto S, Nakano T, et al. Factors correlated with fatigue in disease-free breast cancer patients: application of the Cancer Fatigue Scale. Support Care Cancer. 2000;8:215–22. doi: 10.1007/s005200050288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bower JE, Ganz PA, Desmond KA, Bernaards C, Rowland JH, Meyerowitz BE, et al. Fatigue in long-term breast carcinoma survivors. Cancer. 2006;106:751–58. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Servaes P, Verhagen S, Bleijenberg G. Determinants of chronic fatigue in disease-free breast cancer patients: a cross-sectional study. Ann of Oncol. 2002;13:589–98. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdf082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Curt GA, Breitbart W, Cella D, Groopman JE, Horning SJ, Itri LM, et al. Impact of cancer-related fatigue on the lives of patients: new findings from the Fatigue Coalition. Oncologist. 2000;5:353–60. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.5-5-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wagner L, Cella D. Fatigue and cancer: causes, prevalence and treatment approaches. Br J Cancer. 2004;91:822–28. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Portenoy RK, Itri LM. Cancer-related fatigue: guidelines for evaluation and management. Oncologist. 1999;4:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cella D, Peterman A, Passik S, Jacobsen P, Breitbart W. Progress toward guidelines for the management of fatigue. Oncology. 1998;12:369–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cramp F, Daniel J. Exercise for the management of cancer-related fatigue in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(2) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006145.pub2. CD006145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McNeely ML, Campbell KL, Rowe BH, Klassen TP, Mackey JR, Courneya KS. Effects of exercise on breast cancer patients and survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2006;175:34–41. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.051073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Speck RM, Courneya KS, Masse LC, Duval S, Schmitz KH. An update of controlled physical activity trials in cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cancer Surviv. 2010;4:87–100. doi: 10.1007/s11764-009-0110-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scott H, McMillan D, Forrest L, Brown D, McArdle C, Milroy R. The systemic inflammatory response, weight loss, performance status and survival in patients with inoperable non-small cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2002;87:264–67. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lundstrom S, Furst CJ. Symptoms in advanced cancer: relationship to endogenous cortisol levels. Palliat Med. 2003;17:503–8. doi: 10.1191/0269216303pm780oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bower JE, Ganz PA, Aziz N, Fahey JL. Fatigue and proinflammatory cytokine activity in breast cancer survivors. Psychosom Med. 2002;64:604–11. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200207000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McAuley E, White SM, Rogers LQ, Motl RW, Courneya KS. Physical activity and fatigue in breast cancer and multiple sclerosis: psychosocial mechanisms. Psychosom Med. 2009;72:88–96. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181c68157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McAuley E, Blissmer B. Self-efficacy determinants and consequences of physical activity. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2000;28:85–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maciejewski PK, Prigerson HG, Mazure CM. Self-efficacy as a mediator between stressful life events and depressive symptoms: differences based on history of prior depression. Brit J Psychiatry. 2000;176:373–8. doi: 10.1192/bjp.176.4.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cutrona CE, Troutman BR. Social support, infant temperament, and parenting self-efficacy: a mediational model of postpartum depression. Child Dev. 1986:1507–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Servaes P, Verhagen C, Bleijenberg G. Fatigue in cancer patients during and after treatment prevalence, correlates and interventions. Eur J Cancer. 2002;38:27–43. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00332-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trojan DA, Arnold D, Collet JP, Shapiro S, Bar-Or A, Robinson A, Le Cruguel JP, Ducruet T, Narayanan S, Arcelin K. Fatigue in multiple sclerosis: association with disease-related, behavioural and psychosocial factors. Mult Scler. 2007;13:985–95. doi: 10.1177/1352458507077175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Humpel N, Iverson DC. Review and critique of the quality of exercise recommendations for cancer patients and survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2005;13:493–502. doi: 10.1007/s00520-005-0811-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.American Psychological Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV-TR. American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; Washington, D.C.: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Geinitz H, Zimmermann FB, Thamm R, Keller M, Busch R, Molls M. Fatigue in patients with adjuvant radiation therapy for breast cancer: Long-term follow-up. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2004;130:327–33. doi: 10.1007/s00432-003-0540-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keys A, Karvonen MJ, Kimura N, Fidanza F, Taylor HL. Indices of relative weight and obesity. J of Chronic Dis. 1972;25:329–343. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(72)90027-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Godin G, Shephard RJ. A simple method to assess exercise behavior in the community. Canadian Journal of Applied Sport Sciences. Can J Appl Sport Sci. 1985;10:141–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bassett DR, Ainsworth BE, Swartz AM, Strath SJ, O’Brien WL, King GA. Validity of four motion sensors in measuring moderate intensity physical activity. Med Sci Sport Exerc. 2000;32:S471–80. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200009001-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tudor-Locke C, Ainsworth B, Thompson R, Matthews C. Comparison of pedometer and accelerometer measures of free-living physical activity. Med Sci Sport Exerc. 2002;34:2045–51. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200212000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trost SG, McIver KL, Pate RR. Conducting accelerometer-based activity assessments in field-based research. Med Sci Sport Exerc. 2005;37:S531–43. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000185657.86065.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McAuley E. Self-efficacy and the maintenance of exercise participation in older adults. J Behav Med. 1993;16:103–13. doi: 10.1007/BF00844757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zigmond AS, Snaith R. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hann D, Jacobsen P, Azzarello L, Martin S, Curran S, Fields K, et al. Measurement of fatigue in cancer patients: development and validation of the Fatigue Symptom Inventory. Qual Life Res. 1998;7:301–10. doi: 10.1023/a:1024929829627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muthen L, Muthen B. Mplus 6.0. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén; 1998-2010. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arbukle J. Full information estimation in the presence of incomplete data. In: Marcoulide G, Schumacker R, editors. Advanced structural equation modeling: Issues and techniques. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1996. pp. 243–78. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Enders CK. The impact of nonnormality on full information maximum-likelihood estimation for structural equation models with missing data. Psychol Methods. 2001;6:352–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Enders CK, Bandalos DL. The relative performance of full information maximum likelihood estimation for missing data in structural equation models. Struct Equ Modeling. 2001;8(3):430–57. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kessler R, Greenberg D. Linear panel analysis: models of quantitative change. New York: Academic Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jöreskog K, Sörbom D. LISREL 8: User’s reference guide. Chicago: Scientific Software International; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structl Equ Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Browne M, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen K, Long J, editors. Testing Structural Equation Models. Newbury Park: Sage; 1993. pp. 136–62. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bandura A. Social cognitive theory. Annals of child development. 1989;6(1):1–60. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jerome GJ, Marquez DX, McAuley E, Canaklisova S, Snook E, Vickers M. Self-efficacy effects on feeling states in women. Int J Behav Med. 2002;9:139–54. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm0902_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marquez DX, Jerome GJ, McAuley E, Snook EM, Canaklisova S. Self-efficacy manipulation and state anxiety responses to exercise in low active women. Psychol Health. 2002;17:783–91. [Google Scholar]

- 44.McAuley E, Talbot HM, Martinez S. Manipulating self-efficacy in the exercise environment in women: Influences on affective responses. Health Psychol. 1999;18:288–94. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.18.3.288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bandura A, Taylor CB, Williams SL, Mefford IN, Barchas JD. Catecholamine secretion as a function of perceived coping self-efficacy. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1985;53:406–14. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.3.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bandura A. Self-efficacy conception of anxiety. Anxiety Research. 1988;1:77–98. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mausbach BT, von Kanel R, Roepke SK, Moore R, Patterson TL, Mills PJ, et al. Self-efficacy buffers the relationship between dementia caregiving stress and circulating concentrations of the pro-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-6. J Amer Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;19:64–71. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181df4498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.O’Leary A. Self-efficacy and health: Behavioral and stress-physiological mediation. Cognit Ther and Res. 1992;16:229–45. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wiedenfeld SA, O’Leary A, Bandura A, Brown S, Levine S, Raska K. Impact of perceived self-efficacy in coping with stressors on components of the immune system. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1990;59:1082–94. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.59.5.1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Donovan KA, Jacobsen PB, Small BJ, Munster PN, Andrykowski MA. Identifying Clinically Meaningful Fatigue with the Fatigue Symptom Inventory. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;36:480–487. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]