Abstract

Adolescent cannabis use is associated with greater relative risk, increased symptom severity, and earlier age of onset of schizophrenia. We investigated whether this interaction may be partly attributable to disease-related disturbances in metabolism of the major cortical endocannabinoid 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG). Transcript levels for the recently discovered 2-AG metabolizing enzyme, α-β-hydrolase domain 6 (ABHD6), were assessed using quantitative PCR in the prefrontal cortex of schizophrenia and healthy subjects (n = 84) and antipsychotic- or tetrahydrocannabinol-exposed monkeys. ABHD6 mRNA levels were elevated in schizophrenia subjects who were younger and had a shorter illness duration but not in antipsychotic- or tetrahydrocannabinol-exposed monkeys. Higher ABHD6 mRNA levels may increase 2-AG metabolism which may influence susceptibility to cannabis in the earlier stages of schizophrenia.

Keywords: α-β-Hydrolase domain 6, ABHD6, Cannabis, 2-Arachidonylglycerol, Cannabinoid receptor

1. Introduction

Cannabis use, particularly during adolescence, has been associated with increased symptom severity in schizophrenia, a higher risk of developing the disorder, and an earlier age of illness onset (D’Souza et al., 2005; Compton et al., 2009; Foti et al., 2010; Casadio et al., 2011; Galvez-Buccollini et al., 2012). These associations may be partly attributable to preexisting disturbances in endogenous cannabinoid signaling in the prefrontal cortex (PFC) (Eggan et al., 2008). Unfortunately, the major endocannabinoid in the PFC, 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG), cannot be measured in postmortem human brain (Palkovits et al., 2008). We previously reported that mRNA levels for synthesizing (diacylglycerol lipase α and β) and metabolizing (monoglyceride lipase) enzymes for 2-AG were not altered in the PFC in schizophrenia (Volk et al., 2010). However, the serine hydrolase α-β-hydrolase domain 6 (ABHD6) was recently discovered to metabolize 2-AG and to tightly regulate 2-AG signaling in the PFC (Marrs et al., 2010). Furthermore, in vitro studies have demonstrated that overexpression of ABHD6 leads to higher levels of 2-AG metabolism, while RNA silencing of ABHD6 mRNA and selective inhibitors of ABHD6 lower 2-AG metabolism (Marrs et al., 2010, 2011; Navia-Paldanius et al., 2012). Given the ability of ABHD6 to regulate 2-AG levels, we sought to further investigate the status of 2-AG metabolism in schizophrenia by quantifying ABHD6 mRNA levels in the PFC.

2. Methods

2.1. Human subjects

Brain specimens were obtained during autopsies conducted at the Allegheny County Medical Examiner’s Office after consent was obtained from next-of-kin. Independent, experienced research clinicians made consensus DSMIV diagnoses for each subject using structured interviews with family members and review of medical records (Volk et al., 2010). To control for experimental variance, 42 subjects with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder were matched individually to one healthy comparison subject for sex and as closely as possible for age (Supplemental Table S1) as previously described (Volk et al., 2011), and samples from subjects in a pair were processed together throughout all stages of the study. The mean age, postmortem interval, freezer storage time, brain pH, and RNA integrity number (RIN; Agilent Bioanalyzer) did not differ between subject groups (Table 1), and each subject had a RIN ≥7.0. All procedures were approved by the University of Pittsburgh’s Committee for the Oversight of Research Involving the Dead and Institutional Review Board.

Table 1.

Summary of demographic and postmortem characteristics of human subjects.

| Parameter | Healthy comparison | Schizophrenia |

|---|---|---|

| N | 42 | 42 |

| Sex | 31M/11F | 31M/11F |

| Race | 34W/8B | 29W/13B |

| Age (years) | 48 ± 13 | 47 ± 13 |

| Postmortem interval (hours) | 17.8 ± 5.9 | 18.1 ± 8.7 |

| Freezer storage time (months) | 128 ± 44 | 129 ± 46 |

| Brain pH | 6.8 ± 0.2 | 6.6 ± 0.4 |

| RNA integrity number | 8.3 ± 0.6 | 8.2 ± 0.7 |

| Medications at time of death | ||

| Antipsychotic | – | 36/42 |

| Antidepressant | – | 17/42 |

| Benzodiazepine/valproic acid | – | 15/42 |

| Cause of Death | ||

| Cardiopulmonary-related | 35/42 | 17/42 |

| Suicide | – | 11/42 |

| Other | 7/42 | 14/42 |

For age, postmortem interval, freezer storage time, brain pH, and RNA integrity number, values are group means ± standard deviation (t(82) < 2.0, p > 0.05). For medications at time of death and cause of death, the number of subjects in each applicable category is provided.

2.2. Quantitative PCR

Frozen tissue blocks containing the middle portion of the right superior frontal sulcus were confirmed to contain PFC area 9 using Nissl-stained, cryostat tissue sections for each subject (Volk et al., 2000). Standardized amounts of cortical gray matter from tissue blocks were collected in TRIzol in a manner that ensured minimal white matter contamination and excellent RNA preservation (Volk et al., 2012). cDNA was synthesized from standardized dilutions of total RNA for each subject. All primer pairs (Supplemental Table S2) demonstrated high amplification efficiency (>96%) across a wide range of cDNA dilutions and specific single products in dissociation curve analysis. Quantitative PCR was performed using the comparative cycle threshold (CT) method with Power SYBR Green dye and the StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). Based on their stable relative expression levels between schizophrenia and comparison subjects (Hashimoto et al., 2008), three reference genes (beta actin, cyclophilin A, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) were used to normalize ABHD6 mRNA levels. The difference in CT (dCT) was calculated by subtracting the geometric mean CT for the three reference genes from the CT for ABHD6 (mean of four replicates). Because dCT represents the log2-transformed expression ratio of ABHD6 to the reference genes, the relative ABHD6 mRNA level is reported as 2−dCT (Vandesompele et al., 2002; Hashimoto et al., 2008).

2.3. Antipsychotic-exposed monkeys

Young adult, male monkeys (Macaca fascicularis) received oral doses of haloperidol, olanzapine or placebo (n = 6 monkeys per group) twice daily for 17–27 months (Dorph-Petersen et al., 2005). RNA was isolated from PFC area 9, and qPCR was conducted for the same three reference genes and ABHD6 (Supplemental Table S2). All animal studies were approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

2.4. Tetrahydrocannabinol-exposed monkeys

As described previously (Verrico et al., 2012), tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) or vehicle was administered intravenously via vascular access port to adolescent male monkeys (Macaca mulatta; n = 7 monkeys per group) once daily for 5 days per week at doses gradually titrated up to 180–240 μg/kg which induced signs of acute intoxication and impairments in spatial working memory. After 12 months of THC administration followed by one month of withdrawal (Verrico and Lewis, 2011), monkeys were euthanized. qPCR for ABHD6 mRNA in PFC area 9 was conducted as described earlier.

2.5. Statistical analysis

An analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was employed with ABHD6 mRNA level as the dependent variable; diagnostic group as the main effect; postmortem interval, brain pH, RIN, and storage time as covariates, and subject pair as a blocking factor to account for the matching of subjects in a pair for sex and age and for the parallel processing of tissue samples from a pair. Analyses of differences in mRNA levels between schizophrenia subjects grouped by indicators of disease severity, substance abuse and psychotropic medications were conducted using the same ANCOVA model (substituting age for subject pair) with α = .05. For the monkey studies, an ANOVA model was employed with mRNA level as the dependent variable and treatment as the main effect.

3. Results

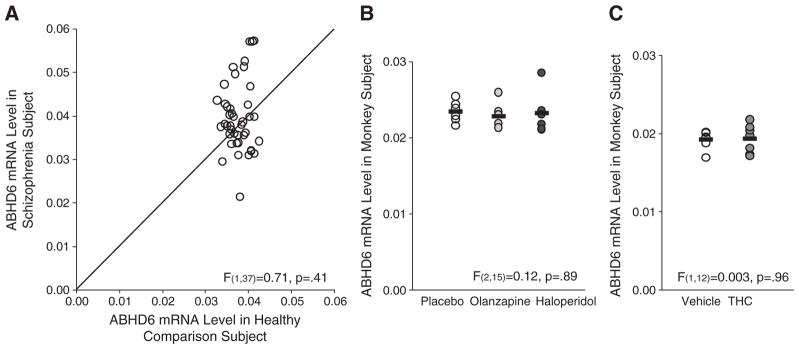

Mean ABHD6 mRNA levels did not differ (F(1,37) = 0.71, p = .41) between schizophrenia and healthy comparison subjects (Fig. 1A). A second primer set designed against a different ABHD6 mRNA region (Supplemental Table 2) confirmed the absence of a between-group difference in ABHD6 mRNA levels (F(1,37) = 0.13, p = .72). ABHD6 mRNA levels from the two primer sets were highly correlated across all subjects (r = .92, p < 0.0001), demonstrating the specificity and reproducibility of the quantification technique.

Fig. 1.

qPCR determination of ABHD6 mRNA levels in the PFC of schizophrenia subjects and antipsychotic- or tetrahydrocannabinol-exposed monkeys. A. mRNA levels for schizophrenia subjects relative to matched healthy comparison subjects in a pair are indicated by open circles. Data points to the right of the unity line indicate lower mRNA levels in the schizophrenia subject relative to the healthy comparison subject and vice versa. Mean ABHD6 mRNA levels (±standard deviation) in schizophrenia subjects (0.040 ± 0.008) did not differ from comparison subjects (0.038 ± 0.003). B. qPCR analysis revealed no statistically significant differences in ABHD6 mRNA expression in monkeys chronically exposed to either olanzapine (0.023 ± 0.002; light gray circles) or haloperidol (0.023 ± 0.003; dark gray circles) compared to placebo (0.023 ± 0.001; open circles). Mean values are shown as horizontal black bars. C. qPCR analysis also revealed no statistically significant differences in ABHD6 mRNA expression in monkeys chronically exposed to tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) (0.019 ± 0.002; dark gray circles) compared to vehicle (0.019 ± 0.001; open circles).

The coefficient of variation in ABHD6 mRNA levels was strikingly higher in schizophrenia subjects (20.1%; Fig. 1A) than in comparison subjects (6.7%), and we examined several factors that might contribute to this variability. Among schizophrenia subjects, ABHD6 mRNA levels did not differ as a function of factors that predict a more severe course of illness (male sex, a diagnosis of schizophrenia rather than schizoaffective disorder, first-degree relative with schizophrenia, early age at illness onset [≤18 years of age]) or measures of illness severity (suicide, no history of marriage, low socioeconomic status as measured by the Hollingshead Index of Social Position, living dependently at the time of death) (all F(1,35) < 2.7, p > .11). We also found no relationship between history of cannabis use, comorbid diagnosis of substance abuse or dependence, use of antipsychotic, antidepressant, or benzodiazepine medications at time of death, or cause of death (categorized as cardiopulmonary-related, suicide, or other; Table 1; Supplemental Table 1) and ABHD6 mRNA levels in schizophrenia subjects (all F ≤ 1.6, p ≥ 0.23). ABHD6 mRNA levels also did not differ in the PFC of monkeys chronically exposed to haloperidol, olanzapine, or placebo (Fig. 1B; F(2,15) = 0.12, p = .89) or to THC (Fig. 1C; F(1,12) = 0.003, p = .96).

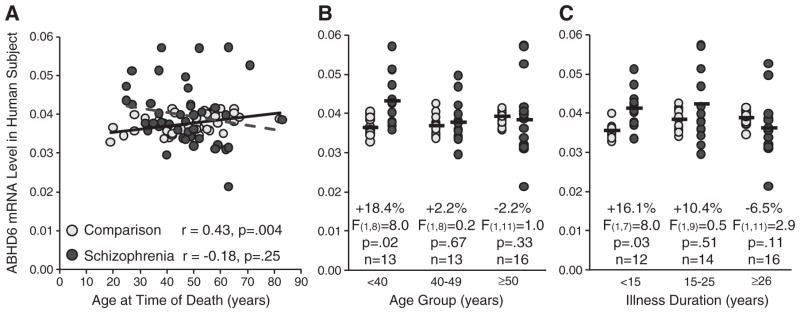

Interestingly, ABHD6 mRNA levels were positively correlated with age in healthy subjects (r = 0.43, p = .004) but not in schizophrenia subjects (r = −0.18, p = .25; Fig. 2A). Consequently, we subdivided the schizophrenia subjects into three similarly-sized age groups using natural break points (<40 years n = 13, 40–49 years n = 13, ≥50 years n = 16; Fig. 2B) and found that schizophrenia subjects under 40 years of age had higher ABHD6 mRNA levels (+18.4%; F(1,8) = 8.0, p = .02) relative to age-matched comparison subjects (all other age groups: F ≤ 1.0, p ≥ 0.33). To assess whether higher ABHD6 mRNA levels in younger individuals with schizophrenia might also reflect a shorter duration of illness, we subdivided the schizophrenia subjects into three similarly-sized groups based on illness duration (<15 years n = 12, 15–25 years n = 14, ≥26 years n = 16; Fig. 2C) and found that subjects with illness duration of less than 15 years had higher ABHD6 mRNA levels (+16.1%; F(1,7) = 8.0, p = .03) relative to age-matched comparison subjects (all other groups: F ≤ 2.9, p ≥ 0.11). Furthermore, age and illness duration were strongly correlated in schizophrenia subjects (r = .79, p < .0001) which made it difficult to differentiate between their effects on ABHD6 mRNA levels.

Fig. 2.

Relationship between ABHD6 mRNA levels and age and illness duration in schizophrenia and healthy comparison subjects. A. ABHD6 mRNA levels are plotted against age in schizophrenia subjects (dark gray circles and dashed gray linear regression line; n = 42) and healthy comparison subjects (light gray circles and black linear regression line; n = 42). ABHD6 mRNA levels were positively correlated with age in healthy subjects (r = 0.43, p = .004) but not in schizophrenia subjects (r = −0.18, p = .25). B–C. Using natural break points, schizophrenia subjects were divided into three similarly-sized groups by age (B) [range (with mean ± standard deviation): 25–38 years (32.7 ± 5.0 years); 40–49 years (46.1 ± 2.9 years); and 50–83 years (59.3 ± 8.8 years)] and duration of illness (C) [range (with mean ± standard deviation): 3–14 years (8.4 ± 3.8 years); 15–25 years (19.0 ± 3.2 years); and 28–55 years (36.0 ± 8.1 years)] using natural break points. ABHD6 mRNA levels for schizophrenia subjects within each of these subgroups were then compared to their matched comparison subjects. Black bars note the average ABHD6 mRNA expression level in the schizophrenia and corresponding comparison subjects. ABHD6 mRNA levels were higher in schizophrenia subjects under 40 years of age (0.043 ± 0.001) and with illness duration of less than 15 years (0.041 ± 0.004) relative to age-matched comparison subjects (0.036 ± 0.002 and 0.036 ± 0.002, respectively) but did not differ in the other groups.

4. Discussion

ABHD6 mRNA levels did not differ overall in the PFC in schizophrenia. However, the markedly high variability in ABHD6 mRNA levels in schizophrenia relative to comparison subjects appeared to be attributable to elevated ABHD6 mRNA levels in schizophrenia subjects who were younger in age and had a shorter duration of illness at the time of death. We also found that the normal age-related increase in ABHD6 mRNA levels was not present in schizophrenia which may mask the disease effect on ABHD6 mRNA levels in older schizophrenia subjects. In addition, ABHD6 mRNA levels were not affected by chronic exposure to either antipsychotic medication or THC. Interestingly, ABHD6 is co-localized with the 2-AG synthesizing enzyme diacylglycerol lipase in the dendritic spines of pyramidal neurons in the PFC (Yoshida et al., 2006; Marrs et al., 2010; Ludanyi et al., 2011). In the same cohort of subjects, we previously reported that mRNA levels for diacylglycerol lipase are not altered in the PFC in schizophrenia (Volk et al., 2010). Importantly, higher ABHD6 mRNA levels without changes in diacylglycerol lipase lead to higher metabolism of 2-AG (Marrs et al., 2010, 2011; Navia-Paldanius et al., 2012). Thus, higher metabolism of 2-AG at the source of 2-AG production may lower 2-AG activity at the corresponding cannabinoid 1 receptor (CB1R). Higher 2-AG metabolism coupled with lower CB1R mRNA and protein levels, which have been reported in the PFC of the same cohort of schizophrenia subjects (Eggan et al., 2008), together suggest that 2-AG signaling is lower in the PFC in the earlier stages of the illness.

Deficits in 2-AG signaling may have several different deleterious effects on cortical circuitry function in schizophrenia. For example, disturbances in 2-AG signaling may interfere with neurite formation and dendritic maintenance in schizophrenia (Bellon, 2007; Keimpema et al., 2010; Zorina et al., 2010; Bellon et al., 2011). Furthermore, ABHD6 regulates 2-AG-mediated, CB1R-dependent long term depression of excitatory postsynaptic potentials in adult mouse prefrontal cortex (Marrs et al., 2010), suggesting that alterations in ABHD6 levels may impact glutamatergic signaling in the disorder. In addition, a major role of 2-AG involves suppressing GABA release from CB1R-containing inhibitory axon terminals (Eggan et al., 2010; Yoshino et al., 2011), and deficits in the GABA synthesizing enzyme GAD67 have been commonly reported in the PFC in schizophrenia (Akbarian et al., 1995; Guidotti et al., 2000; Volk et al., 2000; Straub et al., 2007; Fung et al., 2010), including the current cohort of subjects (Curley et al., 2011). Since CB1R is expressed at an early gestational stage in (future) cortical GABA neurons and regulates their development (Berghuis et al., 2005, 2007), lower 2-AG signaling (if present prenatally) may interfere with cortical GABA neuron development in schizophrenia. Alternatively, if alterations in 2-AG signaling emerge postnatally in the disorder, then lower 2-AG signaling in schizophrenia may enhance GABA release from CB1R-containing axon terminals which may have a compensatory effect for deficits in GABA synthesis in schizophrenia. If this latter hypothesis is true, then the negative effects of cannabis in schizophrenia may occur because exogenous activation of CB1R by cannabis counteracts the compensatory effect of lower 2-AG signaling accomplished by higher ABHD6 and lower CB1R levels, at least in the earlier stages of the illness. Consistent with this interpretation, the deleterious effects of cannabis use appear to be most prominent in younger individuals and include an earlier stage of onset of schizophrenia and a higher risk for developing the disorder (Compton et al., 2009; Casadio et al., 2011; Galvez-Buccollini et al., 2012) that may be greatest at ages with closest proximity to the onset of cannabis use (Manrique-Garcia et al., 2012). These data suggest the need for preventative strategies directed towards reducing cannabis use in adolescents at risk for schizophrenia.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Role of funding source

This study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (MH-084016 to Dr. Volk, and MH-043784 and MH-084053 to Dr. Lewis).

The authors gratefully acknowledge Elizabeth Sengupta, M.A., for her assistance in the preparation of the experiments.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2013.02.038.

Contributors

Dr. Volk oversaw all aspects of the design and implementation of the study and was the primary author of the manuscript. Mr. Siegel conducted the mRNA quantification studies and the data analysis. Dr. Verrico conducted the study exposing monkeys to tetrahydrocannabinol. Dr. Lewis contributed to the design of the study, interpretation of the data, and the creation and maintenance of the human and antipsychotic-exposed monkey brain tissue banks. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

David Lewis currently receives investigator-initiated research support from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Curridium Ltd. and Pfizer and in 2010–2012 served as a consultant in the areas of target identification and validation and new compound development to BioLine RX, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, and SK Life Science. All other authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- Akbarian S, Kim JJ, Potkin SG, Hagman JO, Tafazzoli A, Bunney WE, Jr, Jones EG. Gene expression for glutamic acid decarboxylase is reduced without loss of neurons in prefrontal cortex of schizophrenics. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52:258–266. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950160008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellon A. New genes associated with schizophrenia in neurite formation: a review of cell culture experiments. Mol Psychiatry. 2007;12:620–629. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellon A, Krebs MO, Jay TM. Factoring neurotrophins into a neurite-based pathophysiological model of schizophrenia. Prog Neurobiol. 2011;94:77–90. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berghuis P, Dobszay MB, Wang X, Spano S, Ledda F, Sousa KM, Schulte G, Ernfors P, Mackie K, Paratcha G, Hurd YL, Harkany T. Endocannabinoids regulate interneuron migration and morphogenesis by transactivating the TrkB receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:19115–19120. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509494102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berghuis P, Rajnicek AM, Morozov YM, Ross RA, Mulder J, Urban GM, Monory K, Marsicano G, Matteoli M, Canty A, Irving AJ, Katona I, Yanagawa Y, Rakic P, Lutz B, Mackie K, Harkany T. Hardwiring the brain: endocannabinoids shape neuronal connectivity. Science. 2007;316:1212–1216. doi: 10.1126/science.1137406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casadio P, Fernandes C, Murray RM, Di Forti M. Cannabis use in young people: the risk for schizophrenia. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2011;35:1779–1787. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton MT, Kelley ME, Ramsay CE, Pringle M, Goulding SM, Esterberg ML, Stewart T, Walker EF. Association of pre-onset cannabis, alcohol, and tobacco use with age at onset of prodrome and age at onset of psychosis in first-episode patients. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:1251–1257. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09030311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curley AA, Arion D, Volk DW, Asafu-Adjei JK, Sampson AR, Fish KN, Lewis DA. Cortical deficits of glutamic acid decarboxylase 67 expression in schizophrenia: clinical, protein, and cell type-specific features. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:921–929. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11010052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorph-Petersen KA, Pierri JN, Perel JM, Sun Z, Sampson AR, Lewis DA. The influence of chronic exposure to antipsychotic medications on brain size before and after tissue fixation: a comparison of haloperidol and olanzapine in macaque monkeys. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:1649–1661. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Souza DC, Abi-Saab WM, Madonick S, Forselius-Bielen K, Doersch A, Braley G, Gueorguieva R, Cooper TB, Krystal JH. Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol effects in schizophrenia: implications for cognition, psychosis, and addiction. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:594–608. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggan SM, Hashimoto T, Lewis DA. Reduced cortical cannabinoid 1 receptor messenger RNA and protein expression in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:772–784. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.7.772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggan SM, Melchitzky DS, Sesack SR, Fish KN, Lewis DA. Relationship of cannabinoid CB1 receptor and cholecystokinin immunoreactivity in monkey dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Neuroscience. 2010;169:1651–1661. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foti DJ, Kotov R, Guey LT, Bromet EJ. Cannabis use and the course of schizophrenia: 10-year follow-up after first hospitalization. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:987–993. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09020189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung SJ, Webster MJ, Sivagnanasundaram S, Duncan C, Elashoff M, Weickert CS. Expression of interneuron markers in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex of the developing human and in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:1479–1488. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09060784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvez-Buccollini JA, Proal AC, Tomaselli V, Trachtenberg M, Coconcea C, Chun J, Manschreck T, Fleming J, DeLisi LE. Association between age at onset of psychosis and age at onset of cannabis use in non-affective psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2012;139:157–160. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidotti A, Auta J, Davis JM, Gerevini VD, Dwivedi Y, Grayson DR, Impagnatiello F, Pandey G, Pesold C, Sharma R, Uzunov D, Costa E. Decrease in reelin and glutamic acid decarboxylase67 (GAD67) expression in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2000;57:1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.11.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto T, Bazmi HH, Mirnics K, Wu Q, Sampson AR, Lewis DA. Conserved regional patterns of GABA-related transcript expression in the neocortex of subjects with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:479–489. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07081223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keimpema E, Barabas K, Morozov YM, Tortoriello G, Torii M, Cameron G, Yanagawa Y, Watanabe M, Mackie K, Harkany T. Differential subcellular recruitment of monoacylglycerol lipase generates spatial specificity of 2-arachidonoyl glycerol signaling during axonal pathfinding. J Neurosci. 2010;30:13992–14007. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2126-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludanyi A, Hu SS, Yamazaki M, Tanimura A, Piomelli D, Watanabe M, Kano M, Sakimura K, Magloczky Z, Mackie K, Freund TF, Katona I. Complementary synaptic distribution of enzymes responsible for synthesis and inactivation of the endocannabinoid 2-arachidonoylglycerol in the human hippocampus. Neuroscience. 2011;174:50–63. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.10.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manrique-Garcia E, Zammit S, Dalman C, Hemmingsson T, Andreasson S, Allebeck P. Cannabis, schizophrenia and other non-affective psychoses: 35 years of follow-up of a population-based cohort. Psychol Med. 2012;42:1321–1328. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711002078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrs WR, Blankman JL, Horne EA, Thomazeau A, Lin YH, Coy J, Bodor AL, Muccioli GG, Hu SS, Woodruff G, Fung S, Lafourcade M, Alexander JP, Long JZ, Li W, Xu C, Moller T, Mackie K, Manzoni OJ, Cravatt BF, Stella N. The serine hydrolase ABHD6 controls the accumulation and efficacy of 2-AG at cannabinoid receptors. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:951–957. doi: 10.1038/nn.2601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrs WR, Horne EA, Ortega-Gutierrez S, Cisneros JA, Xu C, Lin YH, Muccioli GG, Lopez-Rodriguez ML, Stella N. Dual inhibition of alpha/beta-hydrolase domain 6 and fatty acid amide hydrolase increases endocannabinoid levels in neurons. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:28723–28728. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.202853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navia-Paldanius D, Savinainen JR, Laitinen JT. Biochemical and pharmacological characterization of human alpha/beta-hydrolase domain containing 6 (ABHD6) and 12 (ABHD12) J Lipid Res. 2012;53:2413–2424. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M030411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palkovits M, Harvey-White J, Liu J, Kovacs ZS, Bobest M, Lovas G, Bago AG, Kunos G. Regional distribution and effects of postmortal delay on endocannabinoid content of the human brain. Neuroscience. 2008;152:1032–1039. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.01.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straub RE, Lipska BK, Egan MF, Goldberg TE, Callicott JH, Mayhew MB, Vakkalanka RK, Kolachana BS, Kleinman JE, Weinberger DR. Allelic variation in GAD1 (GAD67) is associated with schizophrenia and influences cortical function and gene expression. Mol Psychiatry. 2007;12:854–869. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandesompele J, De Preter K, Pattyn F, Poppe B, Van Roy N, De Paepe A, Speleman F. Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol. 2002;3:34.1–34.11. doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-7-research0034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verrico CD, Lewis DA. Long-term exposure of adolescent monkeys to delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol selectively and persistently impairs spatial working memory. Soc Neurosci Abstr. 2011 Nov 16;:911.08. [Google Scholar]

- Verrico CD, Liu S, Bitler EJ, Gu H, Sampson AR, Bradberry CW, Lewis DA. Delay- and dose-dependent effects of delta(9)-tetrahydrocannabinol administration on spatial and object working memory tasks in adolescent rhesus monkeys. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37:1357–1366. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volk DW, Austin MC, Pierri JN, Sampson AR, Lewis DA. Decreased glutamic acid decarboxylase67 messenger RNA expression in a subset of prefrontal cortical gamma-aminobutyric acid neurons in subjects with schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:237–245. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.3.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volk DW, Eggan SM, Lewis DA. Alterations in metabotropic glutamate receptor 1alpha and regulator of G protein signaling 4 in the prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:1489–1498. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10030318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volk DW, Radchenkova PV, Walker EM, Sengupta EJ, Lewis DA. Cortical opioid markers in schizophrenia and across postnatal development. Cereb Cortex. 2011;22:1215–1223. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volk DW, Matsubara T, Li S, Sengupta EJ, Georgiev D, Minabe Y, Sampson A, Hashimoto T, Lewis DA. Deficits in transcriptional regulators of cortical parvalbumin neurons in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169:1082–1091. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12030305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida T, Fukaya M, Uchigashima M, Miura E, Kamiya H, Kano M, Watanabe M. Localization of diacylglycerol lipase-alpha around postsynaptic spine suggests close proximity between production site of an endocannabinoid, 2-arachidonoyl-glycerol, and presynaptic cannabinoid CB1 receptor. J Neurosci. 2006;26:4740–4751. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0054-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshino H, Miyamae T, Hansen G, Zambrowicz B, Flynn M, Pedicord D, Blat Y, Westphal RS, Zaczek R, Lewis DA, Gonzalez-Burgos G. Postsynaptic diacylglycerol lipase mediates retrograde endocannabinoid suppression of inhibition in mouse prefrontal cortex. J Physiol. 2011;589:4857–4884. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.212225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zorina Y, Iyengar R, Bromberg KD. Cannabinoid 1 receptor and interleukin-6 receptor together induce integration of protein kinase and transcription factor signaling to trigger neurite outgrowth. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:1358–1370. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.049841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.