Abstract

Background

Hepatitis B-linked liver cancer disproportionately affects Hmong Americans. With an incidence rate of 18.9/100,000, Hmong Americans experience liver cancer at a rate that is 6–7 times greater than that of non-Hispanic Whites. Serological testing for the hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a principal means to prevent liver cancer deaths through earlier identification of those at risk.

Methods

Academic researchers and Hmong leaders collaborated in the design, conduct, and evaluation of a 5-year randomized controlled trial testing a lay health worker (LHW) intervention to promote HBV testing among 260 Hmong adults through in-home education and patient navigation.

Results

Intervention group participants were more likely to report receiving serological testing for HBV (24% vs. 10%, p=0.0056) and showed a greater mean increase in knowledge score (1.3 vs. 0.3 points, p=0.0003) than control group participants. Multivariable modeling indicated that self-reported test receipt was associated with intervention group assignment (odds ratio [OR] 3.5, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.3–9.2), improvement in knowledge score (OR 1.3 per point, 95% CI 1.02–1.7), female gender (OR 5.3, 95% CI 1.7–16.6), and having seen a doctor in the past year at baseline (OR 4.8, 95% CI 1.3–17.6). The most often cited reason for testing was a doctor’s recommendation.

Conclusions

LHWs were effective in bringing about HBV screening. Doctor visits and adherence to doctors’ recommendations were pivotal. Participation of health care providers is essential to increase HBV testing.

Impact

LHWs can significantly increase HBV screening rates for Hmong, but their doctors’ recommendation is highly influential and should be pursued.

Keywords: Hepatitis B, Hmong, Randomized controlled trial, community-based, liver cancer

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is responsible for about two-thirds of all primary liver cancers and is the cancer type most clearly associated with hepatitis B (HBV) and hepatitis C (HCV) viral infections and cirrhosis (1). The risk of liver cancer is 12–300 times greater in individuals chronically infected with HBV than in those who are infection-free. Asian Americans experience not only the highest incidence but also the highest mortality rates for liver cancer (2). Chronic HBV infection is endemic among Asian Americans (3) and is the principal risk factor for liver cancer among this population, responsible for 80–85% of cases (4). Of all Asian American groups, the Hmong experience the lowest survival rates due to HCC (5) and are the subject of this paper on a community-based randomized controlled trial to increase their HBV screening rates.

According to the 2010 Census, there are 260,076 Hmong living in the United States, a 40% increase since 2000 compared to a 9.7% increase for the overall U.S. population (6). California is home to 91,224 Hmong, the largest of any state (7). These dramatic population increases, the high incidence rates of HBV infection [25.7 per 100,000 for males and 8.8 per 100,000 for females] (8), and the sociocultural health concerns they reflect constitute a context for this community-based intervention study to address the HBV-induced liver cancer burden affecting Hmong Americans.

Data and studies on the cancer burden affecting Hmong Americans in California and elsewhere in the United States are limited. The first known published data specifically on the overall Hmong cancer burden in California were reported by Mills and Yang. (9–12) Based on their data from the California Cancer Registry, using names and other personal identifiers to identify those of Hmong ancestry, they concluded that Hmong disproportionately experience cancers of infectious origin such as cervical, gastric, nasopharyngeal, and liver, rather than the more common cancers, of chronic origin such as lung, breast, and colorectal experienced by the general U.S. population. They emphasized the importance of factoring in Hmong-specific socio-cultural influences to reduce the burden of cancers of infectious origin and the emerging burden of more chronic forms of cancer due to more westernized lifestyles (9–12). Ross et al. (13) using surnames from the Minnesota Cancer Registry data came to similar conclusions about the preponderance of cancers of infectious origin affecting Minnesota Hmong compared to Minnesota residents at large (14).

In California’s Central Valley, a prevalence of HBV infection of 16.7% was assessed with a convenience sample of 534 Hmong adults (15) and a 3.41% prevalence among Hmong blood donors compared to 0.06% from donors of all ethnicities (16). Overall, California Hmong are especially affected by liver cancer, with an average annual incidence rate of liver cancer at 18.9/105 compared to 3.4/105 for non-Hispanic Whites (17). The median survival time for Laotian/Hmong HCC cases is only one month, the lowest of all Californian Asians (5).

Thus, for Hmong adults, serological testing for hepatitis B to determine whether they are chronically infected is the first step towards controlling HBV-induced liver cancer. Serological testing resulting in detection of chronic HBV infection can also increase the chances of receiving effective treatment with medications such as interferon alpha, entecavir or tenofovir (18). Findings from a randomized controlled study of HBV-infected individuals in China suggest that surveillance for HCC with ultrasound imaging and serum alpha fetoprotein can lead to early detection and improved survival (19).

The overall purpose of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of a lay health worker (LHW) intervention in a community-based randomized trial to promote serological testing for HBV and increase knowledge of HBV among Hmong adults. We hypothesized that a significantly greater proportion of Hmong adults, ages 18–64, enrolled in the intervention arm of this LHW study would report serological testing at post-test than in the control arm, and that the knowledge gain in HBV would likewise be greater for Hmong enrolled in the intervention arm than for those in the control arm. Entitled “Community-Based Hepatitis B Interventions for Hmong Adults”, this study was registered on ClinicalTrials.gov as NCT00888407.

Materials and Methods

Research participant consents

The University of California, Davis Institutional Review Board approved the protocol for participation. Verbal consent for telephone screening was obtained by bilingual interviewers. Bilingual LHWs who made home visits obtained consent from participants in person prior to enrollment in the control or intervention arms of the study.

Theoretical basis of intervention

The LHW strategy for intervention delivery (described in the next section) and the selection of intervention content and elements were informed by the Health Behavior Framework (HBF) which is a comprehensive conceptual framework that posits that individual health action is influenced by a multiplicity of factors at the individual, health system, and societal levels (20–21). The model also provides guidance on selecting an intervention strategy that is appropriate for the target audience in question. Thus we selected a LHW strategy focused primarily on modifying individual HBF factors such as HBV knowledge, perceived susceptibility to HBV infection, perceived severity of liver cancer and on reducing barriers and supporting facilitators to action.

LHW intervention strategy

The LHW intervention strategy is an example of the indigenous model (22) which acknowledges the advantages of having individuals who are mature, bilingual, and bicultural from the targeted population as intervention agents. The LHW model recognizes the value of indigenous workers in reaching out and communicating health content and behavioral change to the targeted population. The effectiveness of such a LHW model for Cambodians, Laotians, and Vietnamese in heart health education (23) and in lay-led smoking cessation among Cambodian, Laotian, and Vietnamese men have been documented (24); In our study, Hmong LHWs were experienced case management staff, fluent in Hmong and English, at least age 21, with a driver’s license and car, were able to work flexible hours and were trained by research staff. To reduce potential contamination, LHWs for the intervention arm were only trained on HBV content and lay health workers for the control arm were only trained on nutrition and physical activity content. All of the teams who administered the baseline and post-test interviews and conducted educational sessions were comprised of a male and a female LHW, respecting the cultural tradition of men working with male participants and women working with female participants. The teams, who were from two different Hmong community-based organizations in different counties, each conducted the baseline interviews in their respective county areas before randomization. Then teams from one organization conducted the intervention (HBV screening) educational sessions, and teams from the other organization conducted the control (nutrition and physical activity) educational sessions. After completion of the intervention and control activities, the intervention teams conducted post-test interviews with the control group participants, and the control teams conducted post-test interviews with the intervention group participants. The Project Manager, a bilingual/bicultural Hmong health professional, maintained fidelity of execution of their respective protocols by accompanying LHWs on 19 percent of their visits.

Study sites

Our study was conducted in the Greater Sacramento, CA area (Sacramento County and its four contiguous counties). Our community collaborators gathered the names, addresses, and telephone numbers of Hmong residents using the 18 distinctive Hmong surnames (10) to identify Hmong from local telephone directories in addition to their lists of clients and attendees at outreach activities. Over 3,408 Hmong households constituted our database, which was greater than any extant listing. To minimize contamination, since many Hmong live in the same apartment complex, we only selected households that were separated by at least half a mile from currently participating households.

Study design

Our study design was jointly discussed and developed in concert with our Hmong community collaborators and consisted of: (1) Telephoning Hmong households and randomly selecting one respondent aged 18–64 to estimate the prevalence of serological testing for HBV; (2) Screening age eligible members until an individual not previously tested for HBV was identified and invited to participate in the study; (3) Collecting baseline data from each consenting participant; (4) Randomly assigning participants to either the intervention or control arm; (5) Implementing intervention and control activities; and (6) Administering post-intervention assessments.

Research questions

Our research questions were as follows: (A.) How common is serological testing for HBV among Hmong adults (ages 18–64)? (B.) How effective is a lay health worker intervention in promoting serological testing for HBV among Hmong adults? (C.) How effective is a LHW intervention in increasing knowledge of HBV among Hmong adults not previously tested for HBV? (D.) What factors facilitate or impede serological testing for HBV among Hmong adults?

Sample Selection

To enroll new participants, we randomly selected a batch of households from our database, examined the address of each household in the order selected, and rejected any whose address was within half a mile of a current participant or another household in the same batch. We then attempted to contact and screen each household by telephone. If we reached an adult Hmong individual, we conducted a screening interview with each consenting household member aged 18–64, selected in random order, until we identified a person who had not been tested for hepatitis B; we then invited that individual to participate in the intervention trial. Although all household members were welcome to attend the educational sessions, only one individual per household was enrolled in the study.

Home visits by LHWs

LHWs visited homes three times. The first visit was to administer the baseline instrument before the participant was assigned to the intervention or control condition. A maximum of 2 weeks elapsed between the first visit and the second visit for an educational session approximately 45 minutes long. LHWs used a colored flip chart on HBV (intervention) or nutrition (control) where the key points were presented in a standardized manner in Hmong or in English. The third visit was to administer post-tests, which were conducted approximately six months after the first visit.

The intervention LHWs provided information in Hmong or English (respondent’s preference) in a culturally appropriate and comprehensible way on the value of serological testing for HBV to the eligible respondent. LHWs made phone calls one week after the education session to offer navigation to a serological testing site. The LHWs provided additional case management to individuals who tested positive, including scheduling follow-up care appointments, transportation and interpretation, applying for health insurance, and emotional support. The control condition LHWs also communicated in Hmong or English (respondent’s preference) in a culturally appropriate and comprehensible way but instead provided education about healthy nutrition and physical activity. At the end of the educational session the LHWs offered navigation services, including linking participants to nutrition programs such as Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) and local food banks, and taking them to grocery stores.

During the third session, intervention and control group LHWs administered the post-tests to the control and intervention group participants respectively. To assess the dependent variable, self-reported serological testing for HBV during the study period, respondents were asked, “Have you ever had a blood test to check for hepatitis B?” Those answering “yes” who reported being tested at a time between the screening interview and the post-test were considered “self-reported tested”, and all others were considered “self-reported not tested.” Participants received a 25-lb. bag of rice for doing each survey (pre- and post-test).

Sample size and power

Our study had 80% power to detect a difference of 20 percentage points between the study arms at the 0.05 level, (2-sided) based on an assumption that 5–20% of the control group participants would report being serologically tested, with a sample size of 100 per arm at post-test. In the study, we enrolled 260 participants who had never been tested for HBV, with equal numbers randomized to the intervention group (n=130) and to the control group (n=130). Two hundred seventeen participants completed the post-test: 105 in the intervention group and 112 in the control group.

Questionnaire

The baseline and follow-up questionnaires were based on the Health Behavior Framework (20–21). The baseline questionnaire assessed demographic information, access to care, HBV knowledge (11 items), screening history, HBV-related attitudes and beliefs, nutrition, physical activity, acculturation, and other measures relating to the HBF (20–21). The post-intervention questionnaire also included items on whether, when, where, and why the participant received serological testing, as well as questions about the education and kind of services received from the LHW. See Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of Hmong American participants, Greater Sacramento, CA Region. 2007–2011: Comparisons between Control and Intervention group

| Total % n = 260 |

Control % n = 130 |

Intervention % n= 130 |

p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age Group (years) | |||||

| 18–29 | 28.1 | 26.2 | 30.0 | 0.7164 | |

| 30–49 | 44.6 | 46.9 | 42.3 | ||

| 50–64 | 27.3 | 26.9 | 27.7 | ||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 40.4 | 39.2 | 41.5 | 0.7046 | |

| Female | 59.6 | 60.8 | 58.5 | ||

| Marital Status | |||||

| Married or has Partner | 71.9 | 75.4 | 68.5 | 0.4409 | |

| Widowed or Divorced | 13.5 | 12.3 | 14.6 | ||

| Single | 14.6 | 12.3 | 16.9 | ||

| Education | |||||

| No Formal Education/DK | 63.9 | 65.4 | 62.3 | 0.6056 | |

| Some Formal Education | 36.2 | 34.6 | 37.7 | ||

| Years in U.S. | |||||

| ≤ 10 | 37.9 | 35.7 | 40.2 | 0.4665 | |

| > 10 | 62.1 | 64.3 | 59.8 | ||

| Country of Birth | |||||

| Laos | 73.1 | 74.6 | 71.5 | 0.8311 | |

| Thailand | 21.5 | 20.0 | 23.1 | ||

| USA | 5.4 | 5.4 | 5.4 | ||

| Employment | |||||

| Employed | 31.9 | 35.4 | 28.5 | 0.3104 | |

| Not employed | 68.1 | 64.6 | 71.7 | ||

| Annual household income | |||||

| <$20,000/DK | 63.5 | 66.9 | 60.0 | 0.2464 | |

| >$20,000 | 36.5 | 33.1 | 40.0 | ||

| Health insurance status | |||||

| Yes | 90.8 | 92.3 | 89.2 | 0.3914 | |

| No/DK | 9.2 | 7.7 | 10.8 | ||

| Seen a Traditional Healer in past 12 months | |||||

| Yes | 34.2 | 35.4 | 33.1 | 0.6950 | |

| No/DK | 65.8 | 64.6 | 66.9 | ||

| Regular place of healthcare | |||||

| Yes | 78.0 | 76.9 | 79.1 | 0.6767 | |

| No/DK | 22.0 | 23.1 | 20.9 | ||

| Seen a Doctor in past 12 months | |||||

| Yes | 62.3 | 59.2 | 65.4 | 0.3059 | |

| No/DK | 37.7 | 40.8 | 34.6 | ||

| Language of Survey | |||||

| Hmong | 91.0 | 93.0 | 89.1 | 0.2745 | |

| English/Both | 9.0 | 7.0 | 10.9 | ||

| English Fluency | |||||

| Fluently/Well | 15.8 | 15.4 | 16.2 | 0.8649 | |

| So-So/Poorly/Not at all/DK | 84.2 | 84.6 | 83.9 | ||

| General Health | |||||

| Good | 65.8 | 64.6 | 66.9 | 0.6950 | |

| Fair/Poor/DK | 34.2 | 35.4 | 33.1 | ||

Abbreviation: DK=Don’t Know

Statistical methods

We assessed the history of HBV testing for a randomly selected 18–64 year-old member of households screened for eligibility to participate in the randomized trial, and computed the proportion reporting being tested, along with its 95% confidence interval. We compared participants in the two study arms with respect to baseline demographic characteristics, access to care, and HBV knowledge in order to assess balance between the study arms. Chi-square tests were used for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables.

Evaluation

In order to evaluate the intervention, we used a chi-square test to assess the difference between the intervention and control arms with respect to the post-intervention proportion reporting serological testing during the study period. We also performed an analogous intent-to-treat analysis in which study dropouts were considered not serologically tested.

We used a chi-square test to compare the intervention and control arms with respect to the post-intervention proportion answering each knowledge item correctly. Within each study arm, the change from pre- to post-test in the proportion answering each item correctly was assessed using McNemar’s test, and the difference between the study arms (difference-in-difference score) was assessed using a z-test that accounted for correlation between an individual’s responses over time. The knowledge score was defined as the number of knowledge items answered correctly, and the differences between pre- and post-test knowledge scores were computed for each participant. We used a t-test to assess the difference between the intervention and control arms with respect to the change between baseline and post-intervention in mean knowledge score.

Regression analyses

We developed a logistic regression model for the self-reported receipt of serological testing during the study period (yes or no) as a function of factors potentially associated with testing according to the HBF. The model included a term for study arm (intervention vs. control) representing the intervention effect. Independent variables included demographic and health-related variables (age, gender, educational level, marital status, length of U.S. residency, English language fluency, household income, employment status, regular place of medical care, had seen a doctor in the past twelve months at baseline, had seen a traditional healer in the past 12 months at baseline, self-perception of health). Baseline HBV knowledge scores and change in knowledge scores from pre-test to post-test (i.e., post-test score minus baseline score) were also included in the model in order to assess the association of test receipt with increased knowledge controlling for baseline knowledge level. Statistical significance was assessed at the 0.05 level (2-sided) for all analyses.

Results

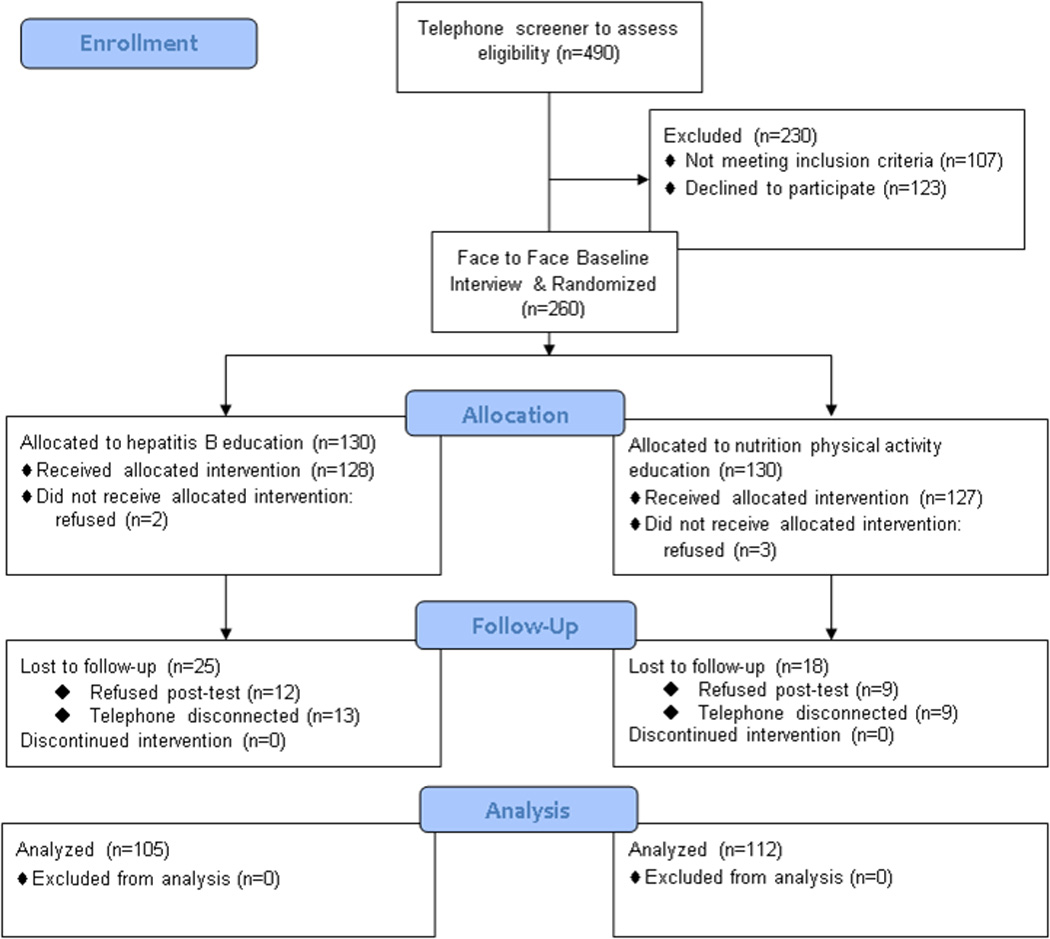

Of the 1860 households selected, we were able to contact 869; the remainder had no phone (n=48), a disconnected phone number (n=551), or did not answer (n=392). Within those contacted households, we identified 552 potential respondents. Of these, 490 were screened for eligibility, 59 refused the screener, and 3 could not be contacted. Of those screened, 260 consented and were randomized equally to intervention and control conditions. The remaining individuals were ineligible (n=107) or refused to participate in the trial (n=123) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

CONSORT Flow Diagram, HBV Screening Intervention

Socio-demographic characteristics of the 260 Hmong randomized trial participants with comparisons between control and intervention groups at baseline are presented in Table 1. Noteworthy is the overall high proportion of female respondents, those with no formal education, foreign nativity (Laos and Thailand), unemployment, low annual household income, but high proportion with health insurance, and overwhelming use of the Hmong language to answer the survey. These characteristics affirm that our study engaged among the most under-served Hmong and hence our findings should be framed within that context. No statistically significant differences in socio-demographic characteristics were detected between control and intervention participants. At baseline, no differences in HBV-related knowledge were detected for 8 of 11 items. Control participants were more likely to answer correctly: “can get HBV by sharing needles” (86% vs. 72%, p=0.0039); “can get HBV at childbirth” (74% vs. 59%, p=0.013); and “HBV causes liver cancer” (66% vs. 52%, p=0.017); control group participants also had higher mean knowledge scores at baseline (5.1 vs. 4.2, p=0.042).

Answers to research questions

(A) Baseline prevalence of HBV test receipt

Altogether 18% of Hmong individuals age 18–64 (78/433) who were initially selected from each household reported having been serologically tested for hepatitis B (95% CI 14–22%).

(B) Effect of intervention on test receipt

In the intention to treat analysis in which study dropouts were classified as not screened, statistically significant results were achieved (19% versus 8%, p=0.0119). The proportion of Hmong adults, ages 18–64, reporting serological testing for HBV during the study period at post-test was also significantly greater in the intervention group than the control group (24% vs. 10%, p=0.0056). The absolute numbers of individuals being serologically tested were n=25 in the intervention group and n=11 in the control group. Adhering to a doctor’s recommendation for testing was given as a reason for being tested by 13 of the 25 tested in the intervention group and 9 of the 11 tested in the control group. Thus, as with Cambodians (25), Chinese (26), Koreans (27), and Vietnamese (28), the pivotal influence of a doctor’s recommendation in being tested for HBV was affirmed in Hmong as well. It should be noted that participants gave multiple reasons for being tested; in fact, 15/25 (60%) of intervention group participants and 2/11 (18%) of control group participants cited Kashia Health (the name of the project) as a reason for being tested, indicating that participants viewed the lay health worker intervention as an important motivator and facilitator.

(C) Effect of intervention on knowledge

The mean knowledge score gain between pre- and post-tests was significantly higher in the intervention compared with the control group (1.3 versus 0.3 correct items, p=0.0003). Statistically significant differences were detected in 6 out of 11 HBV-related knowledge items for the intervention group compared to only one for the control group. At post-test, intervention group participants were more likely than control participants to know that one cannot get hepatitis B by sharing food or eating utensils (42% vs. 27%, p=0.0163) and that Hmong are more likely than white Americans to be infected with HBV (22% vs. 8%, p=0.0040), as well as showing greater increases in the proportion correct for both items, but remained less likely to know that HBV causes liver cancer (56% vs. 71%, p=0.0282).

(D) Factors affecting serological testing

Multivariable modeling indicated that self-reported test receipt was associated with intervention group assignment (OR=3.5, 95% CI 1.3–9.2), pre-test to post-test change in knowledge score (OR=1.3 per point, 95% CI 1.02–1.7), female gender (OR=5.3, 95% CI 1.7–16.6), and having seen a doctor in the past year at baseline (OR=4.8, 95% CI 1.3–17.6).

Participants’ Impressions

When asked what they learned from the LHWs, HBV education was cited by 63% of intervention group members and 35% of control group members, whereas healthy eating was cited by 76% of the control group and 39% of the intervention group (multiple responses were given). Thus, despite our attempts to eliminate any contamination, some spill-over of content between the two groups occurred but the spill-over occurred more or less equally to both groups. We surmise that the content of our questionnaires focusing on HBV, nutrition, and physical activity, may explain the inclusion of topics considered by Hmong participants and subsequently discussed with LHWs. The quality of the education was rated as “good” or “excellent” by 90% of intervention and 91% of control group participants. The LHW services most often mentioned by intervention group members were case management (49%), interpretation (46%), health access (36%), education (21%), and transportation (19%); those most often mentioned by control group members were education (34%), interpretation (26%), case management (21%) and health access (21%). The quality of the services provided by lay health workers was rated as “good” or “excellent” by 96% of intervention and 95% of control group participants.

Discussion

This study is the first randomized, controlled, longitudinal study of a theoretically-informed, nationally peer-reviewed intervention to promote serological testing for HBV among Hmong Americans. To conduct this study, we assembled a team of research and community collaborators including bilingual/bicultural Hmong scientists and community leaders as well as academic experts in biostatistics, cancer control, epidemiology, methodology, theory, and medicine. Academic research rigor, community expertise, and cultural competency perspectives were blended together resulting in innovative methodologies. For instance to create a sampling frame for this randomized, controlled study, our Hmong collaborators compiled the names and addresses of more than 3400 households in our catchment area. No such listing of Hmong residents existed prior to this “census” and an enduring legacy of this study is the continued updating of this database for use by Hmong community leaders.

From this study, we determined that only 18% of the Hmong adults had reported being serologically tested for HBV. Pre-intervention testing rates were greater for Cambodians [45%, male; 54%, female] (25); Chinese [48%] (26); Koreans [56%] (27); and Vietnamese [62%] (28). In comparison to these other Asian American groups, the Hmong had the lowest baseline prevalence rate of HBV test receipt and, on average, the lowest baseline knowledge of HBV transmission, formal education, annual household incomes, English fluency, and awareness of HBV (29).

As a result of our randomized, controlled, LHW intervention the proportion who reported getting a HBV test during the study period was significantly greater in the intervention group than in the control group. However, the actual number of intervention participants who reported being tested (n=25) versus control participants (n=11) was low relative to the effort expended, and fell far short of the CDC recommendations that those who originate from defined endemic regions should be tested for HBV (30). While the knowledge gains for the intervention group significantly exceeded the control group, intervention group members on average had significantly lower knowledge levels than controls at baseline. Regression results indicated that increased knowledge was associated with being tested, controlling for baseline knowledge; however, the intervention effect remained substantial indicating that testing was mainly due to other aspects of the intervention, e.g., navigation.

In our multivariable model, having visited a doctor within the past twelve months was a strong independent predictor of being tested [OR=4.8], and a doctor’s recommendation was also one of the most common reasons for getting tested, regardless of group assignment. Results from the study therefore support the importance of interaction with health care providers as a determinant of being tested. Future interventions that are health care system-based and directly influence health care provider behaviors such as through electronic messaging would appear to be more effective (31), and greater emphasis on influencing provider behavior in community clinic settings is warranted. Our incremental progress in increasing screening was achieved with considerable capacity-building (i.e., training bilingual/bicultural lay health educators, development of educational materials, translation, home visits, etc.). This capacity-building represents an investment in the infrastructure of the two Hmong community-based organizations with whom we worked, and the skills and products that were developed are part of the legacy of this study, enabling the potential of future community-centered participatory efforts.

Limitations

A major limitation of these findings is the reliance on self-reported serological testing rates by Hmong participants. Our rationale for powering our study based on self-reported screening receipt was that in community trials like this one in which participants are not all recruited from the same health system, it can be impractical and cost-prohibitive to collect medical record information from the numerous separate providers. In addition, in community trials focusing on low resource populations, many participants do not have a usual source of care so it is difficult to determine where to obtain validation data for participants who do not report receipt of screening. Based on the results of other intervention studies that verified self-reported tests in provider records (32–34), it is likely that the actual proportion tested in each study arm was lower than indicated by self-report.

We acknowledge that we had to select a large number of households in order to reach our planned sample size. In particular, we do not know how many unreachable households contained individuals in our target population (Hmong age 18–64 not tested for hepatitis B), and whether such individuals differed systematically from the study participants. Nevertheless, 490 of 552 individuals in contacted households (89%) agreed to be screened for eligibility, and 260 of 383 eligible persons (68%) agreed to participate in the randomized trial, indicating that contacted households were well represented.

This study also has considerable strengths. We partnered with two Hmong community-based organizations, the Hmong Women’s Heritage Association for the intervention group and the Hmong Cultural Council of Butte County. These community-based organizations have a history of service and had already earned the community’s trust. We could not have conducted this study without the full support of the Hmong community and its leaders. Our ideas (research design, instrument, conduct of the study, etc.) were thoroughly vetted with Hmong community leaders prior to implementation. The Hmong Project Manager supervised the lay health workers and the data collection, assured the fidelity of the study with respect to research rigor, and contributed extensively to the interpretation of the data. The value of already having earned community trust was immeasurable to the success of this study as it facilitated immediate access to the Hmong community throughout the Greater Sacramento region. Our study embodied many of the characteristics that Lee et al. (35) recommended to reduce barriers to cancer screening in Hmong Americans. All of our LHWs were bilingual, bicultural professionals who were well-trained and well-supervised to assure fidelity to protocols. Regular meetings and extensive documentation allowed us to assure adherence to research rigor. If unanticipated situations arose, the Project Manager conscientiously brought them to the attention of other members of the research team for joint resolution, data analyses, and interpretation of the data. Furthermore, we benefited from our colleagues who were conducting parallel studies among Korean Americans and Vietnamese Americans.

Conclusions

A LHW intervention focused on Hmong adults achieved a statistically significant effect on self-reported serological testing for HBV, the principal risk factor for HCC, and perhaps the most important cancer health disparity affecting Asian Americans (36). This LHW intervention also resulted in significantly greater increases in knowledge about HBV compared with the control condition. Nevertheless, it appeared that even greater effectiveness would be achieved by having more physicians recommend HBV testing.

Table 2.

Baseline and Post-test Hepatitis B-Related Knowledge among Hmong American respondents in Greater Sacramento Region, 2007–2011

| Control (n=112) | Intervention (n=105) | I-C | I-C | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | pre | post | diff | p | pre | post | diff | p | diff | diff p |

| Cannot get Hep B by Smoking | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.00 | 1.000 | 0.08 | 0.18 | 0.10 | 0.016 | 0.10 | 0.079 |

| Can get Hep B by sharing a toothbrush | 0.63 | 0.77 | 0.13 | 0.014 | 0.54 | 0.68 | 0.13 | 0.035 | 0.00 | 0.994 |

| Cannot get Hep B by sharing food/eating utensils | 0.22 | 0.27 | 0.04 | 0.317 | 0.21 | 0.42 | 0.21 | 0.001 | 0.16 | 0.027 |

| Can't get Hep B by being near a person who sneezes | 0.14 | 0.13 | −0.02 | 0.655 | 0.13 | 0.22 | 0.09 | 0.061 | 0.10 | 0.085 |

| Can get Hep B by sharing needles | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.00 | 1.000 | 0.69 | 0.83 | 0.14 | 0.003 | 0.14 | 0.018 |

| Cannot get Hep B by shaking hands with a person | 0.63 | 0.65 | 0.03 | 0.532 | 0.55 | 0.70 | 0.14 | 0.007 | 0.12 | 0.082 |

| Can get Hep B by sexual intercourse | 0.58 | 0.63 | 0.04 | 0.398 | 0.50 | 0.60 | 0.10 | 0.105 | 0.05 | 0.518 |

| Can get Hep B at childbirth | 0.74 | 0.72 | −0.02 | 0.705 | 0.59 | 0.68 | 0.09 | 0.095 | 0.10 | 0.135 |

| Can get Hep B from people who look and feel healthy | 0.38 | 0.37 | −0.02 | 0.724 | 0.30 | 0.37 | 0.08 | 0.194 | 0.09 | 0.222 |

| Hep B causes liver cancer | 0.64 | 0.71 | 0.06 | 0.274 | 0.48 | 0.56 | 0.09 | 0.106 | 0.02 | 0.764 |

| Hmong more likely than white Americans to be infected with Hep B | 0.09 | 0.08 | −0.01 | 0.763 | 0.11 | 0.22 | 0.10 | 0.012 | 0.11 | 0.023 |

Abbreviation: C=Control, I=Intervention, pre=assessed at baseline, post=assessed at post-test, diff=difference, p=p-value

Table 3.

Factors Associated with Self-Reported Serological Testing for Hepatitis B in the Study Period – Hmong Adults, Ages 18–64, Greater Sacramento Region, 2007–2011 (n=210)

| Effect | Odds Ratioa | 95% Confidence Intervala | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study Arm | |||

| Intervention | 3.51 | 1.33 – 9.24 | |

| Control | 1.00 | ||

| Age | |||

| 18–29 | 0.47 | 0.09 – 2.30 | |

| 30–49 | 0.39 | 0.14 – 1.11 | |

| 50–64 | 1.00 | ||

| Gender | |||

| Female | 5.27 | 1.68 – 16.6 | |

| Male | 1.00 | ||

| Marital Status | |||

| Married/living together | 3.02 | 0.92 – 9.93 | |

| Widowed/divorced/single | 1.00 | ||

| Years of U.S. Residence | |||

| More than 10 | 1.48 | 0.57 – 3.85 | |

| 10 or fewer | 1.00 | ||

| Employment Status | |||

| Employed | 0.80 | 0.24 – 2.69 | |

| Not employed | 1.00 | ||

| Educational Level | |||

| Some formal education | 0.69 | 0.20 – 2.33 | |

| No formal education | 1.00 | ||

| Speaks English | |||

| Fluently/well | 0.36 | 0.03 – 4.61 | |

| So-so/poorly/not at all/don’t know | 1.00 | ||

| Annual Household Income | |||

| $20,000 or more | 0.48 | 0.18 – 1.32 | |

| Less than $20,000/don’t know | 1.00 | ||

| Regular place of health careb | 0.43 | 0.11 – 1.74 | |

| Seen doctor in past 12 monthsb | 4.83 | 1.32 – 17.6 | |

| Seen traditional healer in past 12 monthsb | 2.10 | 0.86 – 5.08 | |

| Self-perceived health status | |||

| Good | 1.78 | 0.69 – 4.61 | |

| Fair/poor/don’t know | 1.00 | ||

| Baseline knowledge (per unit) | 1.26 | 0.98 – 1.62 | |

| Change in knowledge (per unit) | 1.32 | 1.02 – 1.71 | |

Adjusted for all variables tabulated

Yes vs. No/don’t know

Note: All independent variables assessed at baseline except change in knowledge.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the extensive manuscript preparation provided by Ms. Tina Fung, MPH, Program Coordinator for the Asian American Network for Cancer Awareness, Research, and Training.

Financial support: All of the authors were either supported in part through P01 CA109091-01A1 funded jointly by the National Cancer Institute/Center to Reduce Cancer Health Disparities and the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities and U54CA153499 or from additional support from the Office of the Dean, School of Medicine, University of California, Davis. However the views in this paper are those of the authors.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: Dr. Christopher L. Bowlus receives research support and consulting fees from Bristol Myers Squibb and Gilead.

Authors’ Contributions

Conception and design: M. Chen, S. Stewart, A. Maxwell, R. Bastani, T. Nguyen

Development of methodology: M. Chen, D. Fang, S. Stewart,

Analysis and interpretation of data (e.g., statistical analysis, biostatistics, computational analysis): S. Stewart, D. Fang, M. Ly, S. Lee

Administrative, technical, or material support (e.g., reporting or organizing data, constructing databases): M. Chen, D. Fang, S. Stewart, J. Dang, Tram Nguyen, C. Bowlus

Study supervision: M. Chen, S. Stewart

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine. Hepatitis and Liver Cancer: A national strategy for prevention and control of Hepatitis B and C. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller BA, Chu KC, Hankey BF, Ries LA. Cancer incidence and mortality patterns among specific Asian and Pacific Islander populations in the United States. Cancer Causes Control. 2008;19:227–256. doi: 10.1007/s10552-007-9088-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin SY, Chang ET, So SK. Why we should routinely screen Asian American adults for hepatitis B: a cross-sectional study of Asians in California. Hepatology. 2007;46(4):1034–1040. doi: 10.1002/hep.21784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.El-Serag HB, Rudolph KL. Hepatocellular carcinoma: Epidemiology and molecular carcinogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2557–2576. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.04.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kwong SL, Stewart SL, Aoki CA, Chen MS., Jr Disparities in hepatocellular carcinoma survival among Californians of Asian ancestry, 1988–2007. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19(11):2747–2757. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoeffel EM, Rastogi S, Kim MO, Shahid H. 2010 Census Briefs. Washington DC: U.S. Bureau of the Census; 2012. The Asian population. [Google Scholar]

- 7.U.S. Census Bureau. 2010 Census Summary File 1, Tables PCT5, PCT6, and PCT7. Washington DC: U.S. Bureau of the Census; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mills P, Yang RC, Riordan D. Cancer incidence in the Hmong in California, 1988–2000. J Cancer. 2005;104(12):2969–2974. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mills PK, Yang RC. Cancer incidence in the Hmong of Central California, USA, 1987–1994. Cancer Causes Control. 1997;8:705–712. doi: 10.1023/a:1018423219749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang RC, Mills P, Riordan DG. Cervical cancer among Hmong women in California, 1988–2000. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27:132–138. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang RC, Mills P, Riordan DG. Gastric adenocarcinoma among Hmong in California, USA, 1988–2000. Gastric Cancer. 2005;8:117–123. doi: 10.1007/s10120-005-0314-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dodge JL, Mills PK, Yang RC. Nasopharyngeal cancer in the California Hmong, 1988–2000. Oral Oncology. 2005;41:596–601. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2005.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ross JA, Xie Y, Kiffmeyer WR, Bushhouse S, Robison LL. Cancer in the Minnesota Hmong population. J Cancer. 2003;97:3076–3079. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gjerdingen DK, Lor V. HBV status of Hmong patients. J Am Bd Fam Pract. 1997;10(5):322–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sheikh M, Mouanoutoua M, Walvick MD. Prevalence of Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection among Hmong immigrants in the San Joaquin Valley. J Comm Health. 2011;36(1):42–61. doi: 10.1007/s10900-010-9283-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sheikh M, Atla PR, Raoufi R, Sadiq H, Sadler PC. Prevalence of Hepatitis B infection among young and unsuspecting Hmong blood donors in the Central California Valley. J Community Health. 2012;37(1):181–185. doi: 10.1007/s10900-011-9434-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cancer Registry of Central California [CRCC] Sacramento, CA: Cancer Registry of Central California [CRCC]; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B: update 2009. Hepatology. 2009;50(3):661–662. doi: 10.1002/hep.23190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang BH, Yang BH, Tang ZY. Randomized controlled trial of screening for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2004;130:417–422. doi: 10.1007/s00432-004-0552-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bastani R, Glenn BA, Taylor VM, Chen MS, Jr, Nguyen TT, Stewart SL. Integrating theory into community interventions to reduce liver cancer disparities: The Health Behavior Framework. Prev Med. 2010;50:63–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maxwell AE, Bastani R, Chen MS, Jr, Nguyen TT, Stewart SL, Taylor VM. Constructing a theoretically-based set of measures for liver cancer control research studies. Prev Med. 2010;50:68–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen MS., Jr The indigenous model for heart health. Health Education. 1989:48–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen MS, Jr, Anderson J, Moeschberger M, Guthrie R, Kuun P, Zaharlick A. An evaluation of heart health. Am J Prev Med. 1994;10(4):205–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen MS., Jr The status of tobacco cessation research for Asian Americans. Asian Am Pacific Isl J Health. 2001;9:66–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taylor VM, Bastani R, Burke N, Talbot J, Sos C, Liu Q, et al. Factors associated with Hepatitis B testing among Cambodian American men and women. J Immigrant Minority Health. 2012;14:30–39. doi: 10.1007/s10903-011-9536-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coronado GD, Taylor VM, Tu S-P, Yasui Y, Acorda E, Woodall E, et al. Correlates of Hepatitis B testing among Chinese Americans. J Community Health. 2007;32:379–390. doi: 10.1007/s10900-007-9060-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bastani R, Glenn BA, Maxwell AE, Jo AM. Hepatitis B testing for liver cancer control among Korean Americans. Ethn Dis. 2007;17(2):365–373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nguyen TT, McPhee SJ, Stewart S, Gildengorin G, Zhang L, Wong C, et al. Factors associated with hepatitis B testing among Vietnamese Americans. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(7):694–700. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1285-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maxwell AM, Stewart SL, Glenn BA, Wong WK, Yasui Y, Chang LC, et al. Theoretically informed correlates of Hepatitis B knowledge among four Asian groups: The Health Behavior Framework. Asian Pacific J Cancer Prev. 2012;13:1687–1692. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2012.13.4.1687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations for identification and public health management of persons with chronic Hepatitis B virus infection. Morb Mort Weekly Rept. 2008;57(No. RR08) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hsu L, Bowlus CL, Stewart S, Nguyen TT, Dang J, Chan B, et al. Electronic messages increase Hepatitis B screening in Asian American patients: A randomized, controlled trial. Dig Dis Sci. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s10620-012-2396-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taylor VM, Hislop TG, Tu SP, Teh C, Accorda E, Yip MP, et al. Evaluation of a hepatitis B lay health worker intervention for Chinese Americans and Canadians. J Community Health. 2009;34(3):165–172. doi: 10.1007/s10900-008-9138-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taylor VM, Hislop TG, Bajdik C, Teh C, Lam W, Accorda E, et al. Hepatitis B ESL education for Asian immigrants. J Community Health. 2011;36(1):35–41. doi: 10.1007/s10900-010-9279-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taylor VM, Bastani R, Burke N, Talbot J, Sos C, Liu Q, et al. Evaluation of a hepatitis B lay health worker intervention for Cambodian Americans. J Community Health. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s10900-012-9649-6. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee HY, Vang S. Barriers to cancer screening in Hmong Americans: the influence of health care accessibility, culture, and cancer literacy. J Community Health. 2010;35(3):302–314. doi: 10.1007/s10900-010-9228-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen MS., Jr Cancer health disparities among Asian Americans: what we know and what we need to do. Cancer. 2005;104(12):2895–2902. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]