Abstract

Cucumber mosaic virus (CMV) has a wide host range causing severe damage in many important agricultural and ornamental crops. Earlier reports showed the prevalence of CMV subgroup I isolates in India. However, some recent reports point towards increasing incidence of subgroup II isolates in the country. The complete genome of a CMV isolate causing severe mosaic in cucumber was characterized and its phylogenetic analysis with other 21 CMV isolates reported worldwide clustered it with subgroup II strains. The genome comprised of RNA 1 (3,379 nucleotides), RNA 2 (3,038 nucleotides) and RNA 3 (2,206 nucleotides). The isolate showed highest homology with subgroup II isolates: 95.1–98.7, 87.7–98.0, and 85.4–97.1 % within RNA1, RNA2, and RNA3, respectively. RNA1 and RNA2 were closely related to the Japanese isolate while RNA3 clustered with an American isolate. Host range studies revealed that isolate showed severe mosaic symptoms on Nicotiana spp. and Cucumis spp. The isolate induced leaf deformation and mild filiform type symptoms in tomato. To best of our knowledge this is the first report of complete genome of CMV subgroup II isolate from India.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s13337-012-0125-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Cucumber mosaic virus, Subgroup II, Host range

Introduction

Cucumber mosaic virus (CMV) is a devastating plant virus having worldwide distribution in temperate and tropical areas. The virus was first reported in 1916 [11, 22] and since then reported to cause disease in a variety of economically important agricultural and ornamental crops. The virus has widest host range infecting over 1,200 species from 100 plant families. CMV is an icosahedral virus approximately 28–30 nm in diameter and belongs to the genus Cucumovirus in the family Bromoviridae. The virus is rapidly transmitted by more than 80 aphid species in a non-persistent manner [31].

CMV is a tripartite virus having three plus sense, single stranded RNA molecules encased in separate particles. RNA1 and RNA2 encodes for the protein 1a and 2a, respectively which forms the replicase complex [31]. N-terminal region of 1a protein contains putative methyltransferase domain [39] and C-terminal region shows sequence similarity to viral helicases [16]. RNA 2 encodes for another protein 2b, which is expressed from the subgenomic RNA 4A and acts as suppressor of gene silencing [4, 5, 27]; plays a role in long distance movement of the virus [9, 23, 43, 54] and also behave as pathogenicity determinant [10, 41, 43]. A recent finding suggested that this suppressor protein is indirectly involved in aphid transmission [56]. A study on mechanism of 2b action showed that the suppressor specifically recruits AGO4 small RNAs and directly interacts with PIWI and PAZ domains of AGO4 affecting its slicer activity, causing hypomethylation of its loci [18]. RNA3 encodes for two proteins: movement protein (MP) located at 5′ end and coat protein which is expressed from another ORF through subgenomic RNA 4. MP plays an important role in cell to cell movement of the virus. While coat protein is required for encapsidation of the genomic RNAs into virus particles, important in aphid transmission [7, 30] and affecting symptom expression [42, 49]. CMV strains are divided into two subgroups I and II [3, 31, 33] and subgroup I is subdivided into IA and IB based on nucleotide sequence of the 3′ untranslated region of RNA3 [37]. Nucleotide sequence similarity among IA and IB subgroup strains is 92–94 %. Subgroup IA and II have worldwide distribution and IB is restricted to Asia only [38].

Broad host range of CMV from subgroup I and II have been identified in India, which includes: Chrysanthemum [45]; Ocimum sanctum and Zinnia elegans [34]; Amaranthus tricolor, Datura innoxia and Hyoscyamus muticus [44]; Gerbera [53]; Vanilla [28]; Pelargonium [52]; Piper longum and Piper betel [19]; Rouvolfia serpentine [35]; Jatrophacurcas [36]; Catharanthusroseus [40]; Daucascarrota [1]; Banana [24, 29]; Lycopersicum esculentum [15, 25, 47]; Gladiolus [13]. Although many CMV strains were isolated from India, but incomplete information is available at the genome level about these isolates. Till date only one complete genome from subgroup I have been reported [25] in India. Here we report molecular and biological characterization of the CMV subgroup II isolate, further information obtained can be utilised for the development of improved diagnostics and finding out symptom and virulence determinants.

Materials and Methods

Mechanical Transmission and Host Range Studies

Young infected leaves of Cucumber plants (Cucumis sativus) showing symptoms of chlorosis and mottling were crushed in chilled 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer, pH 8.0 in a sterile mortar. The crushed sap was filtered through muslin cloth and then filtrate was mechanically inoculated by making gentle abrasion on the leaves of Nicotiana glutinosa using carborundum powder. Then plants were maintained at 22–25 °C under glass house conditions and after 1 week young leaves were analysed for presence of virus. For further study, pure culture of the virus was also maintained on the N. glutinosa plants by single lesion transfer and aphid transmission.

Host range studies were carried out by mechanical inoculation of pure culture of the virus on N. glutinosa, N. clevelandii, N. benthamiana, N. rustica, Chenopodium amaranticolor, C. quinoa, L.esculentum cv. Pusa ruby, different varieties of C. sativus and Capsicum annum plants. The plants were observed for symptom development 3 weeks post inoculation.

Cloning and Sequencing of the Genome

Total RNA was extracted from infected leaf tissue (100 mg) of N. glutinosa by using TRIZOL reagent (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). The integrity and quality of the total RNA was checked on 1 % agarose gel and quantified by nanodrop2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA).

For the amplification of RNA1, 2 and 3 specific primers were designed by multiple alignments of sequences of different isolates of CMV (Supplementary Table 1) available in NCBI database. First strand cDNA synthesis was carried out with ~4 μg total RNA. Total RNA was denatured along with 1.0 μl reverse primer (10 pmol/μl) at 72 °C for 2 min, followed by addition of 5 μl 5× first strand buffer, 0.2 μl ribonuclease inhibitor (40 U/μl), 1.5 μl 40 mM dNTPs and 0.5 μl MMLV-RT (200 U/μl) in a total reaction of 25 μl. Reaction was performed at 42 °C for 60 min followed by incubation at 80 °C for 5 min.

Amplification was done using Taq DNA polymerase (Bangalore Genei, Bengaluru, India) in a thermocycler (G-storm, Somerton Biotechnology centre, Somerset, UK) with initial denaturation of 1 min at 95 °C followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 40 s, annealing and extension temperature being specific for particular amplicon and finally an extension time of 10 min was given at 68 °C (Supplementary Table 1). PCR reaction contained 5 μl of 10× Taq buffer A, 2 μl of forward primer and reverse primer each (10 pmol/μl), 2.5 μl of dNTPs, 1 μl cDNA and 3 U of Taq polymearse (3 U/μl) in total reaction of 50 μl. PCR products were ligated into pGEMT-easy vector (Promega, Madison, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and then transformed into E. coli DH5α. Recombinant colonies were screened by restriction digestion. Positive clones were sequenced in automated DNA sequencer (ABI PRISM 3130xl genetic analyzer) using ABI prism Big Dye Terminator v3.1 ready Reaction Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems, USA) by primer walking. For each amplicon, at least three clones were sequenced. Assembled sequences of RNA1, 2 and 3 were submitted to the GenBank database (HE650150, HE613667, and HE583224 respectively) and the isolate was named as CMV-SG.

Phylogenetic Analysis

Sequences of 32 isolates of CMV belonging to subgroup I and II were retrieved from the NCBI database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) and compared using MEGA 5.05 version (http://www.megasoftware.net). Phylogenetic relationships between these isolates were inferred from the nucleotide sequence alignment by maximum likelihood (Juke canter and 1,000 non-parametric bootstrap replicates). To check the possibility of recombination within CMV isolates we used RDP3 program with default settings. Sequence identity percentage was calculated using Bioedit sequence alignment editor version 7.1.3.0 [17].

Results

CMV-SG isolate developed mosaic symptoms on the inoculated cucumber (Summer Beauty, Summer Green and Veer varieties; Fig. 1b, d), N. glutinosa (Fig. 1m, n; mock inoculated and infected) and N. rustica plants 4–5 days post inoculation (dpi). Concentric chlorotic lesions were found in N. clevelandii (Fig. 1o). Plants showed severe stunting in all tested varieties of cucumber (Fig. 1a, c). In case of tomato, mosaic pattern appeared 5–6 days post inoculation which later became systemic and newly emerging leaves showed downward leaf curling and mild filiform like symptoms (Fig. 1e mock inoculated, f, g infected). In case of Chenopodium quinoa, chlorotic lesions were observed after 3 dpi which later became necrotic (Fig. 1k, l; mock inoculated and infected) whereas in chilli, mild mosaic symptoms appeared 7 dpi and plant showed stunting (Fig. 1h–j; mock inoculated and infected). Cryoelectron microscopy of the purified virus revealed the presence of ~28 nm isometric particles typical of CMV (Supplementary Fig. 1). SDS-PAGE and western blot analysis of purified viral particles showed the presence of dimeric ~52 kDa and monomeric ~26 kDa coat protein (CP) as major band (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Symptoms induced by the CMV on different host plants. Cucumis sativus (a, c) stunting shown by infected plants of C. sativus var. veer and var. summer green respectively in comparison to control. b, d chlorosis and mosaic on leaves after 2 weeks post inoculation; Lycopersicum esculentum (var. Pusa Ruby) e mock inoculated, infected f chlorotic patches on leaves, g leaf deformation and curling; Capsicum anummh stunted growth in infected plant, i mock inoculated leaf, j infected leaf showing chlorotic patches; Chenopodium quinoak mock inoculated plant, l chlorotic necrotic lesions on leaves; Nicotiana glutinosam mock inoculated leaf, n leaf showing mosaic pattern and lesions; Nicotiana clevelandiio infected leaf showing presence of concentric chlorotic lesions

The sequence analysis revealed that RNA1, 2 and 3 comprised of 3,379, 3,038, and 2,206 nucleotides, respectively. Location of various ORFs on various RNAs was established. It can be seen that the ORF 1a codes for 993 amino acids (aa) protein, known to be involved in replication. RNA2 consisted of two overlapping ORFs, 2a and 2b. 2a encodes for RNA dependent RNA polymerase whereas 2b protein functions as viral suppressor. RNA3 codes for 280 aa movement protein (3a) and 219 aa long 3b (CP).

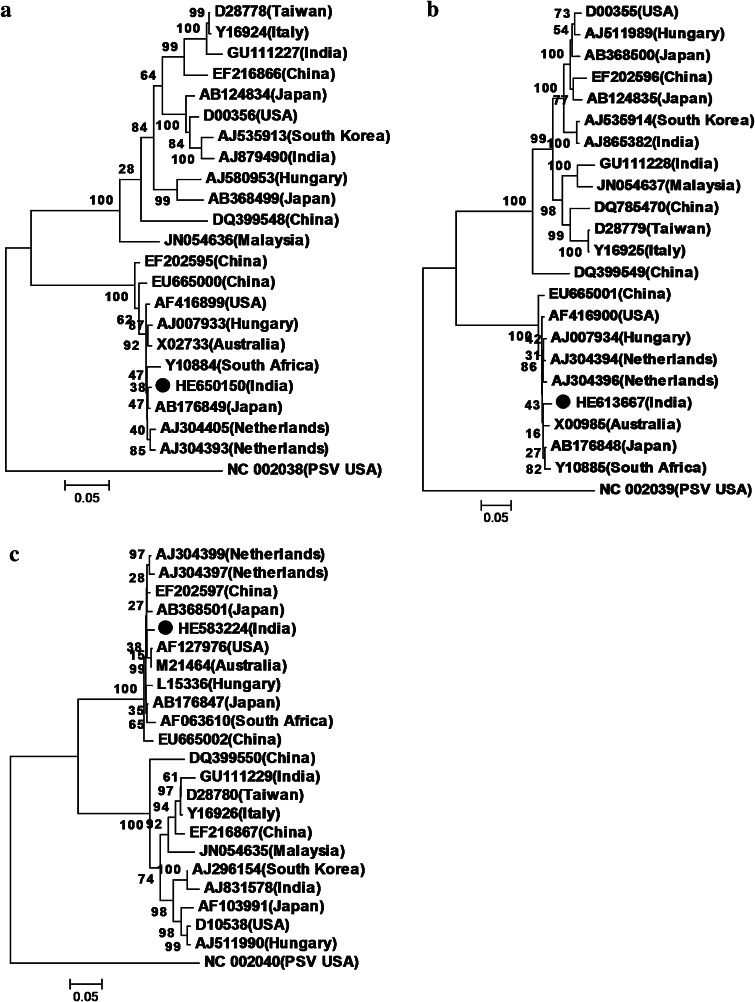

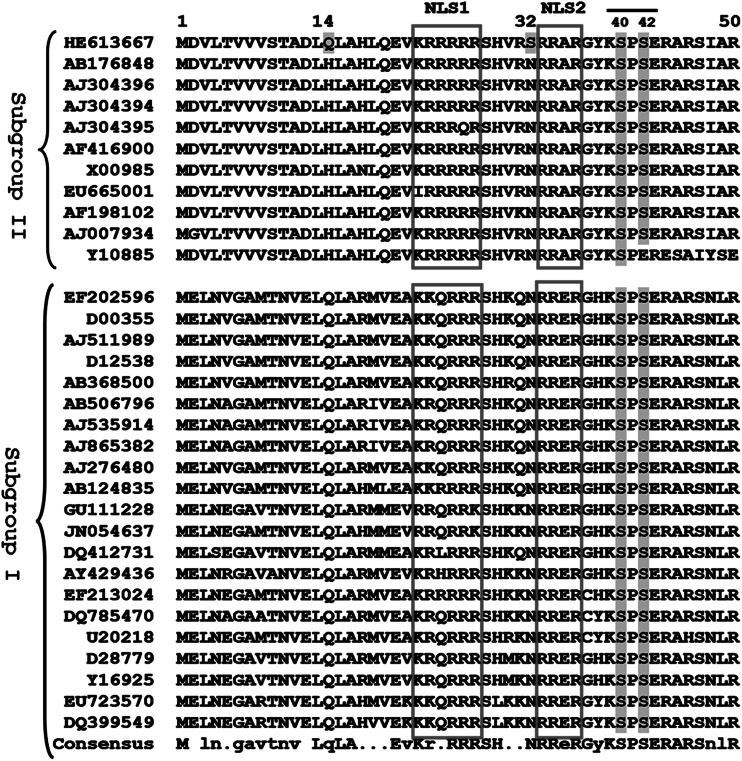

Complete genome sequences of 31 different isolates were selected worldwide and compared with CMV-SG isolate (Supplementary Table 2–4). It showed highest homology with subgroup II isolates viz. 95.1–98.7, 87.7–98.0, and 85.4–97.1 % with RNA1, RNA2, and RNA3, respectively whereas it showed 71.3–75.6, 67.5–69.6, and 65.0–72.0 % homology with subgroup I isolates for respective RNAs. RNA1 of CMV-SG (HE650150) showed maximum nucleotide identity 98.7 and 98.6 % with American (AF416899), Japanese (AB176849) and Australian isolates (AF198101) from subgroup II. RNA2 also shared maximum identity of 98 % with American (AF416900) and Japanese (AB176848) isolates. Similarly, RNA3 shared 97 % sequence similarity with Japanese (AB176847) and Chinese (EF202397) isolates. It was observed that the 3′ UTR of viral RNAs were conserved and showed 96 % identity in case of RNA1 and 2, 88 % in RNA1 and 3 and 87 % identity in RNA2 and 3. Comparison with complete RNA3 sequences of Indian isolates showed that CMV-SG isolate showed 95.8 and 94.3 % nucleotide identity with EU642567 (carrot) and JF279605 (Tss-In) isolates, respectively. Based on coat protein sequence analysis, CMV-SG isolate showed 99 and 96.9 % identity with isolates from geranium (AJ866272) and lily (AJ585086), respectively and 98.1 % identity with Aligarh isolate from Ocimum sanctum (EU600216). Phylogenetic analysis of 22 CMV isolates revealed that RNA1 (Fig. 2a) and RNA2 (Fig. 2b) clustered with Japanese isolate while RNA3 clustered with American and Australian isolates from subgroup II (Fig. 2c). RDP analysis didn’t show any recombination event among CMV isolates. Amino acid sequence comparison of 1a protein with other isolates showed some unique changes at following positions: serine at 223; tyrosine at 460; phenylalanine at 624 and glutamic acid at 904 when compared to members of subgroups I and II. In 2a protein: glycine at 53 position; arginine at 206; glycine at 451; cysteine at 594; asparagine at 600; proline at 657; cysteine at 688 and alanine at 788 positions. In 2b protein histidine is substituted with glutamine at aa 14 and asparagine at position 32 with serine (Fig. 3). There were two substitutions in case of coat protein at aa 10 serine with glycine and at aa 106 histidine with arginine. 3a protein also showed three substitutions at aa 42 (glycine with serine), at aa 158 (phenylalanine with tyrosine) and at aa 253 (asparagine with serine). The isolate showed maximum changes in RNA2 (8 substitutions in 2a protein and 2 substitutions in 2b protein). Nuclear localization signal motif (NLS1), KRRRRR; NLS2, RRAR and putative phosphortylation motif KSPSE were conserved in 2b. The substitution at aa 14 histidine with glutamine is unique among subgroup II isolates but represented by subgroup I isolate and other substitution at position 32 is present before NLS2 sequence. The 3′UTR were conserved among RNA1, 2 and 3.

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic relationships of complete RNA1 (a), RNA2 (b) and RNA3 (c) sequences of present CMV isolate with 21 different isolates of CMV, determined using the maximum-likelihood method based on the Jukes-Cantor model (implemented in MEGA5, with 1000 maximum-likelihood bootstrap replicates)

Fig. 3.

Alignment of 2b protein from subgroup I and II showing two arginine rich nuclear localization regions (NLS1 and NLS2), putative phosphorylation motif (indicated by bar and putative phosphorylated serine residues at position 40 and 42) and substitution site at position 14 and 32 in the CMV-SG isolate

Discussion

In India, CMV isolates have been reported from several regions. Mainly, subgroup I isolates has been reported and there are few reports of subgroup II isolates [1, 15, 47, 53]. The isolate under study showed up to 99 and 76 % similarity to the subgroup II and I isolates, respectively. Depending on the host and virus strain, CMV is known to cause variable symptoms, including necrotic or chlorotic lesions, mild to severe mosaic, stunting, leaf deformation and shoestring formation [14]. Subgroup I strains shows severity in terms of symptom and disease development on tobacco [55]. The present isolate (CMV-SG) induced chlorotic lesions becoming necrotic in local lesion assay host, Chenopodium quinoa 3 dpi. Mosaic symptoms and systemic infection was observed in all Nicotiana species (N.glutinosa, N.clevelandii, N.benthamiana and N.rustica). Lesions and concentric chlorotic rings were observed on N.glutinosa and N.clevelandii respectively. Severe chlorotic, mosaic and stunting symptoms developed on various cucumber varieties (Fig. 1b, d). In newly developing tomato leaves, viral isolate induced symptoms ranging from severe chlorotic patches, downward curling and reduced leaf lamina to mild filiformism. Previously, shoestring like leaves symptoms were reported only with some subgroup I strains [2, 20, 32, 46, 48]. From India also there was report of mosaic symptoms on tomato by subgroup II strain [47] and now in a recent observation it was found that shoestring symptoms were not restricted to subgroup I. A subgroup II isolate Tss-In developed shoestring symptoms on tomato [15]. Cryoelectron microscopy of purified virus showed the presence of ~28 nm isometric particle size, its SDS-PAGE and western blotting showed CP of ~26 kDa and its dimeric form at ~52 kDa. Similar kind of pattern was previously observed in case of CMV-amaranthus strain [34].

Phylogenetic analysis with 21 different isolates of CMV (selected worldwide) at the nucleotide level clustered RNA1 and 2 with Japanese isolate and RNA3 with American and Australian isolates. At the amino acid level 1a and MP protein showed close resemblance to Japanese isolate, 2a and 2b to USA isolate, and coat protein to Australian isolate. Changes in the replicase protein and suppressor protein can affect the infectivity of the virus [26, 50, 54]. Reassortment is a natural mechanism which leads to genetic variation and new strain emergence in multipartite RNA viruses [6]. New CMV strains emerged due to reassortment among subgroup I and II strains [8].

From India, 15 complete RNA3 sequences (including present isolate) and 70 complete coat protein and 27 movement protein sequences have been submitted. Based on the comparison of 15 RNA3 sequence and their phylogenetic analysis it was found to be closely related to an isolate infecting carrot (EU642567; Aligarh isolate) an isolate closely related to Australian isolate, AF198103 [1]. Also an isolate (IA) from India showing 99 % identity to CP gene of USA isolate has been reported [12]. A subgroup II isolate from Ocimum sanctum was found closely related to European isolate, EU191025 [24].

The adaptation of the virus to the new environment and the host plants leads to the emergence of new isolates. In CMV there was report of specific adaptation to the host plant in case of soybean isolate from Indonesia [21]. So far from India complete genome of CMV from subgroup II has not been reported and resemblance of all reported isolates with Asian and European isolates is based on only RNA3 and CP phylogenetic analysis. In our study CMV isolate showed resemblance to Japanese and American isolate and thus showing its mixed origin which might be making it more stable in this type of environment. The isolate is very competitive in its infection on different host plants taken during the study and thus affecting their growth. Previously from India reports of CMV subgroup-I incidence were prevalent, but now reports belonging to incidence of sub group-II are increasing. Similar results were also reported from China [51]. These results indicate that sub group-II strains were evolving in such a manner that increases their successful infection rate in field. Thus the present study reports the first complete genome of CMV subgroup II from India, information related to complete genome of an Indian isolate from subgroup II can be utilised for the better diagnostic development and understanding the host pathogen relationship.

Electronic supplementary material

Fig. 1: Cryoelectron micrograph of the purified virus preparation from C. sativus showing ~28 nm isometric particles typical of CMV. (TIFF 5429 kb)

Fig. 2: Western blot of purified CMV particles showing dimeric form ~52 kDa and monomeric form ~26 kDa coat protein (CP) as major band. (TIFF 1576 kb)

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to the Director, Council of Scientific & Industrial Research, Institute of Himalayan Bioresource Technology, Palampur, Himachal Pradesh India for providing the necessary facilities to carry out the work. We also thank Dr. Avnesh Kumari and Dr. Madhu Sharma for cryoelectron microscopy work. A fellowship to PB and RK, financial support from the Department of Biotechnology, Government of India and Council of Scientific & Industrial Research are duly acknowledged. This is IHBT publication number 3432.

Footnotes

A. A. Zaidi—deceased.

References

- 1.Afreen B, Khan AA, Naqvi QA, Kumar S, Pratap D, Snehi SK, Raj SK. Molecular identification of a Cucumber mosaic virus subgroup II isolate from carrot (Daucus carota) based on RNA3 genome sequence analyses. J Plant Dis Prot. 2009;116:193–199. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akhtar KP, Ryu KH, Saleem MY, Asghar M, Jamil FF, Haq MA, Khan IA. Occurrence of Cucumber mosaic virus Subgroup IA in tomato in Pakistan. J Plant Dis Prot. 2008;115:2–3. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson BJ, Boyce PM, Blanchard CL. RNA 4 sequences from cucumber mosaic virus subgroup I and II. Gene. 1995;161:193–194. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00276-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beclin C, Berthome R, Palauqui JC, Tepfer M, Vaucheret H. Infection of tobacco or Arabidopsis plants by CMV counteracts systemic post-transcriptional silencing of nonviral (trans) genes. Virology. 1998;252:313–317. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brigneti G, Voinnet O, Li WX, Ji LH, Ding SW, Baulcombe DC. Viral pathogenicity determinants are suppressors of transgene silencing in Nicotiana benthamiana. EMBO J. 1998;17:6739–6746. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.22.6739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 6.Chao L. Evolution of genetic exchange in RNA viruses. In: Morse SS, editor. The evolutionary biology of viruses. New york: Raven press; 1994. pp. 233–250. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen B, Francki RI. Cucumovirus transmission by the aphid Myzus persicae is determined solely by the viral coat protein. J Gen Virol. 1990;71:939–944. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-71-4-939. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen Y, Chen J, Zhang H, Tang X, Du Z. Molecular evidence and sequence analysis of a natural reassortant between Cucumber mosaic virus subgroup IA and II strains. Virus Genes. 2007;35:405–413. doi: 10.1007/s11262-007-0094-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ding SW, Li WX, Symons RH. A novel naturally occurring hybrid gene encoded by a plant RNA virus facilitates long distance virus movement. EMBO J. 1995;14:5762–5772. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00265.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ding SW, Shi BJ, Li WX, Symons RH. An interspecies hybrid RNA virus is significantly more virulent than either parental virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:7470–7474. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doolittle SP. A new infectious mosaic disease of cucumber. Phytopathology. 1916;6:145–147. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dubey VK, Aminuddin, Singh VP. First report of a subgroup IA Cucumber mosaic virus isolate from gladiolus in India. Australas Plant Dis Notes. 2008;3:35–37. doi: 10.1071/DN08014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dubey VK, Aminuddin, Singh VP. Molecular characterization of Cucumber mosaic virus infecting Gladiolus, revealing its phylogeny distinct from the Indian isolate and alike the Fny strain of CMV. Virus Genes. 2010;41:126–134. doi: 10.1007/s11262-010-0483-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Francki RIB, Mossop DW, Hatta T. Cucumber mosaic virus. In: Harrison BD, Mutant AF, editors. Descriptions of plant viruses. Kew: CMI/AAB; 1979. p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geetanjali A, Kumar R, Srivastava PS, Mandal B. Biological and molecular characterization of two distinct tomato strains of Cucumber mosaic virus based on complete RNA-3 genome and subgroup specific diagnosis. Indian J Virol. 2011;22:117–126. doi: 10.1007/s13337-011-0051-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gorbalenya AE, Koonin EV, Donchenko AP, Blinov VM. Two related superfamilies of putative helicases involved in replication, recombination, repair and expression of DNA and RNA genomes. Nucl Acids Res. 1989;17:4713–4730. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.12.4713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hall TA. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp Ser. 1999;41:95–98. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamera S, Song X, Su L, Chen X, Fang R. Cucumber mosaic virus suppressor 2b binds to AGO4-related small RNAs and impairs AGO4 activities. Plant J. 2012;69:104–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04774.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hareesh PS, Madhubala R, Bhat AI. Characterization of Cucumber mosaic virus infecting Indian long pepper (Peperlongum L.) and betel vine (Piper betle L.) in India. Indian J Biotechnol. 2006;5:89–93. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hellwald KH, Zimmermann C, Buchenauer H. RNA 2 of Cucumber mosaic virus subgroup I strain NT-CMV is involved in the induction of severe symptoms in tomato. Eur J Plant Pathol. 2000;106:95–99. doi: 10.1023/A:1008744114648. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hong JS, Masuta C, Nakano M, Abe J, Uyeda I. Adaptation of Cucumber mosaic virus soybean strains (SSVs) to cultivated and wild soybeans. Theor Appl Genet. 2003;107:49–53. doi: 10.1007/s00122-003-1222-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jagger IC. Experiments with the cucumber mosaic disease. Phytopathology. 1916;6:149–151. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ji LH, Ding SW. The suppressor of transgene RNA silencing encoded by Cucumber mosaic virus interferes with salicylic acid mediated virus resistance. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2001;14:715–724. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2001.14.6.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khan S, Jan AT, Aquil B, Haq QMR. Coat protein gene based characterization of Cucumber mosaic virus isolates infecting banana in India. J Phytol. 2011;3:94–101. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koundal V, Haq QMR, Praveen S. Characterization, genetic diversity, and evolutionary link of Cucumber mosaic virus strain New Delhi from India. Biochem Genet. 2011;49:25–38. doi: 10.1007/s10528-010-9382-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lewsey M, Surette M, Robertson FC, Ziebell H, Choi SH, Ryu KH, Canto T, Palukaitis P, Payne T, Walsh JA, Carr JP. The role of the Cucumber mosaic virus 2b protein in viral movement and symptom induction. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2009;22:642–654. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-22-6-0642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li HW, Lucy AP, Guo HS, Li WX, Ji LH, Wong SM, Ding SW. Strong host resistance targeted against a viral suppressor of the plant gene silencing defence mechanism. EMBO J. 1999;18:2683–2691. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.10.2683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Madhubala R, Bhadramurthy V, Bhat AI, Hareesh PS, Retheesh ST, Bhai RS. Occurrence of Cucumber mosaic virus on vanilla (Vanilla planifolia Andrews) in India. J Biosci. 2005;30:339–350. doi: 10.1007/BF02703671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mali VR, Rajegore SB. A Cucumber mosaic virus disease of banana in India. J Phytopathol. 1980;98:127–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0434.1980.tb03725.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ng JCK, Perry KL. Transmission of plant viruses by aphid vectors. Mol Plant Pathol. 2004;5:505–511. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2004.00240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Palukaitis P, Roossinck MJ, Dietzgen RG, Francki RIB. Cucumber mosaic virus. Adv Virus Res. 1992;41:281–348. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(08)60039-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pratap D, Kumar S, Raj SK. First molecular identification of a Cucumber mosaic virus isolate causing shoestring symptoms on tomato in India. Australas Plant Dis Notes. 2008;3:57. doi: 10.1071/DN08023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Quemada H, Kearney C, Gonsalves D, Slightom JL. Nucleotide sequences of the coat protein gene and flanking regions of Cucumber mosaic virus. J Gen Virol. 1989;70:1065–1073. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-70-5-1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raj SK, Chandra G, Singh BP. Some Indian strains of Cucumber mosaic virus (CMV) lacking satellite RNA. Indian J Exp Biol. 1997;35:1128–1131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raj SK, Kumar S, Pratap D, Vishnoi R, Snehi SK. Natural occurrence of Cucumber mosaic virus on Rauvolfia serpentina, a new record. Plant Dis. 2007;91:322. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-91-3-0322C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Raj SK, Kumar S, Snehi SK. First report of Cucumber mosaic virus on Jatropha curcas in India. Plant Dis. 2008;92:171. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-92-1-0171C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roossinck MJ, Zhang L, Hellwald KH. Rearrangements in the 5′ nontranslated region and phylogenetic analyzes of Cucumber mosaic virus RNA 3 indicate radial evolution of three subgroups. J Virol. 1999;73:6752–6758. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.8.6752-6758.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roossinck MJ. Cucumber mosaic virus, a model for RNA virus evolution. Mol Plant Pathol. 2001;2:59–63. doi: 10.1046/j.1364-3703.2001.00058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rozanov MN, Koonin EV, Gorbalenya AE. Conservation of the putative methyltransferase domain: a hallmark of the ‘Sindbis-like’ supergroup of positive-strand RNA viruses. J Gen Virol. 1992;73:2129–2134. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-73-8-2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Samad A, Ajayakumar PV, Gupta MK, Shukla AK, Darokar MP, Somkuwar B, Alam M. Natural infection of periwinkle (Catharanthus roseus) with Cucumber mosaic virus, subgroup IB. Australas Plant Dis Notes. 2008;3:30–34. doi: 10.1071/DN08013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shi BJ, Palukaitis P, Symons RH. Differential virulence by strains of Cucumber mosaic virus is mediated by the 2b gene. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2002;15:947–955. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2002.15.9.947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shintaku MH, Lee Z, Palukaitis P. A single amino-acid substitution in the coat protein of Cucumber mosaic virus induces chlorosis in tobacco. Plant Cell. 1992;4:751–757. doi: 10.1105/tpc.4.7.751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Soards AJ, Murphy AM, Palukaitis P, Carr JP. Virulence and differential local and systemic spread of Cucumber mosaic virus in tobacco are affected by the CMV 2b protein. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2002;15:647–653. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2002.15.7.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Srivastava A, Raj SK. High molecular similarity among Indian isolates of Cucumber mosaic virus suggests a common origin. Curr Sci. 2004;87:1126–1131. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Srivastava KM, Raj SK, Singh BP. Properties of a Cucumber mosaic virus strain naturally infecting Chrysanthemum in India. Plant Dis. 1992;76:474–476. doi: 10.1094/PD-76-0474. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stamova BS, Chetelat RT. Inheritance and genetic mapping of Cucumber mosaic virus resistance introgressed from Lycopersicon chilensec into tomato. Theor Appl Genet. 2000;101:527–537. doi: 10.1007/s001220051512. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sudhakar N, Nagendra-Prasad D, Mohan N, Murugesan K. First report of Cucumber mosaic virus subgroup II infecting Lycopersicon esculentum in India. Plant Dis. 2006;90:1457. doi: 10.1094/PD-90-1457B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sulistyowati E, Mitter N, Bastiaan-Net S, Rossinck MJ, Dietzgen RG. Host range, symptom expression, and RNA3 sequence analysis of six Australian strains of Cucumber mosaic virus. Australas Plant Pathol. 2004;33:505–512. doi: 10.1071/AP04054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Suzuki M, Kuwata S, Masuta C, Takanami Y. Point mutations in the coat protein of Cucumber mosaic virus affect symptom expression and virion accumulation. J Gen Virol. 1995;76:1791–1799. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-76-7-1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tao X, Zhou X, Li G, Yu J. Two amino acids on 2a polymerase of Cucumber mosaic virus co-determine hypersensitive response on legumes. Sci China Ser C Life Sci. 2003;46:40–48. doi: 10.1007/BF03182683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tian Z, Jiyan Q, Jialin Y, Chenggui H, Weicheng L. Competition between Cucumber mosaic virus subgroup I and II isolates in tobacco. J Phytopathol. 2009;157:457–464. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0434.2008.01531.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Verma N, Mahinghara BK, Ram R, Zaidi AA. Coat protein sequence shows that Cucumber mosaic virus isolate from geraniums (Pelargonium spp.) belongs to subgroup II. J Biosci. 2006;31:47–54. doi: 10.1007/BF02705234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Verma N, Singh AK, Singh L, Kulshrestha S, Raikhy G, Hallan V, Raja R, Zaidi AA. Occurrence of Cucumber mosaic virus in Gerbera jamesonii in India. Plant Dis. 2004;88:1161. doi: 10.1094/PDIS.2004.88.10.1161C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang Y, Tzfira T, Gaba V, Citovsky V, Palukaitis P, Gal-On A. Functional analysis of the Cucumber mosaic virus 2b protein: pathogenicity and nuclear localization. J Gen Virol. 2004;85:3135–3147. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.80250-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang L, Hanada K, Palukaitis P. Mapping local and systemic symptom determinants of cucumber mosaic cucumovirus in tobacco. J Gen Virol. 1994;75:3185–3191. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-11-3185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ziebell H, Murphy AM, Groen SC, Tungadi T, Westwood JH, Lewsey MG, Moulin M, Kleczkowski A, Smith AG, Stevens M, Powell G, Carr JP. Cucumber mosaic virus and its 2b RNA silencing suppressor modify plant-aphid interactions in tobacco. Sci Rep. 2011;1:187. doi: 10.1038/srep00187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. 1: Cryoelectron micrograph of the purified virus preparation from C. sativus showing ~28 nm isometric particles typical of CMV. (TIFF 5429 kb)

Fig. 2: Western blot of purified CMV particles showing dimeric form ~52 kDa and monomeric form ~26 kDa coat protein (CP) as major band. (TIFF 1576 kb)