Abstract

Background

Bacillus subtilis glucokinase (GlcK) (GenBank NP_390365) is an ATP-dependent kinase that phosphorylates glucose to glucose 6-phosphate. The GlcK protein has very low sequence identity (13.7%) to the Escherichia coli glucokinase (Glk) (GenBank P46880) and some other glucokinases (EC 2.7.1.2), yet glucose is merely its substrate. Our lab has previously isolated and characterized the glcK gene.

Results

Microbial glucokinases can be grouped into two different lineages. One of the lineages contains three conserved cysteine (C) residues in a CXCGX(2)GCXE motif. This motif is also present in the B. subtilis GlcK. The GlcK protein occurs in both monomer and homodimer. Each GlcK monomer has six cysteines. All cysteine residues have been mutated, one-by-one, into alanine (A). The in vivo GlcK enzymatic activity was assayed by functional complementation in E. coli UE26 (ptsG ptsM glk). Mutation of the three motif-specific residues led to an inactive enzyme. The other mutated forms retained, or in one case (GlcKC321A) even gained, activity. The fluorescence spectra of the GlcKC321A showed a red shift and enhanced fluorescence intensity compare to the wild type's.

Conclusions

Our results emphasize the necessity of cysteines within the CXCGX(2)GCXE motif for GlcK activity. On the other hand, the C321A mutation led to higher GlcKC321A enzymatic activity with respect to the wild type's, suggesting more adequate glucose phosphorylation.

Background

Glucose kinase/glucokinase (GlcK/Glk) (EC 2.7.1.2) is one of the first enzymes encountered along the glycolytic pathway. This enzyme is responsible for catalyzing the ATP/ADP-dependent phosphorylation of the sixth carbon position of glucose to glucose 6-phosphate. Unlike the bacterial and archaeal glucokinases, the closest eukaryotic glucokinase counterpart such as yeast hexokinase B and human hexokinase IV (HK4 or GCK) (EC 2.7.1.1) are well characterized. In fact, the protein structure of yeast hexokinase B (31% identical amino acid residues to human HK4) was deciphered more than two decades ago [1]. Sites for the glucose formed hydrogen bond in human HK4: T168, K169, N204, D205, N231, and E290 are conserved among eukaryotes [2-4]. However, these sites are not found in microbial glucokinases. HK4 is able to phosphorylate not only glucose, but also mannose, fructose, sorbitol, and glucosamine (for review, see reference [5]). Microbial glucokinase has its own unique glucose-binding domain, which maybe conserved among glucokinases. The domain seems highly specific for glucose.

We have previously cloned and characterized the glcK gene of Bacillus subtilis [6]. Replacement of ATP by ADP revealed no detectable glucokinase activity, neither did replacement of glucose by fructose, galactose, or mannose [6]. The GlcK protein was characterized by Km values for ATP and glucose of 0.77 mM and 0.24 mM, respectively [6]. The ATP binding-motif D [ILV]G [GA] [T] conserved for both GlcK and HK4 are located at the N-terminal [3]. The mechanism of Mg2+-ATP binding to GlcK has never been directly observed but rather proposed by their homology to the ATP-binding sites of HK4 [6]. Two recent 3-D protein structures of ADP-dependent glucokinases, belonging to hyperthermophilic archaeon, Thermococcus litoralis and Pyrococcus horikoshii, showed the Mg2+ motif (NEXE) and the ADP/ATP-dependent kinases motif ([SD]TXG XGDX [IF]) [7,8]. Interestingly, the T. litoralis and P. horikoshii glucokinases are similar to ATP-dependent kinases: E. coli ribokinase and human adenosine kinase [7]. As a consequence, those archaeal glucose-binding sites are similar to the ribokinase, while the specific glucose-binding sites for many bacterial glucokinases remain elusive. It turns out that the archaeal glucokinases, including the Aeropyrum pernix ATP dependent Glk, showed broad specificity for hexoses, such as fructose, mannose, glucosamine, N-acetylglucosamine, and N-mannosamine [9].

Glucokinases, which participate in carbon catabolite repression [10-13], contain the so-called ROK (repressor, ORF, kinase) [14,15]. Two alternative ROK motifs have been suggested: [LIVM]X(2)G [LIVMFCT]GX [GA] [LIVMFA]X(8)GX(3–5) [GATP]X(2)G [R KH] [14,15] and CXCGX(2)GX [WILV]EX [YFVIN]X [STAG] [9,16]. Concha and Leon [16] further proposed cysteine (C) residues, especially those within the ROK motif, to be essential for the catalytic activity of glucokinase. These may also be required for glucose binding.

Here we describe the unexpected finding that the phylogenetic analysis provided two clusters of microbial glucokinases sequences, which are also distinguished by the presence or absence of the CXCGX(2)GCXE motif. Since B. subtilis GlcK contains this motif, the role of C residues within the motif as well as the remaining C residues was examined.

Results

Glucose kinases/glucokinases (EC 2.7.1.2) comprise two lineages with or without a conserved CXCGX(2)GCXE motif

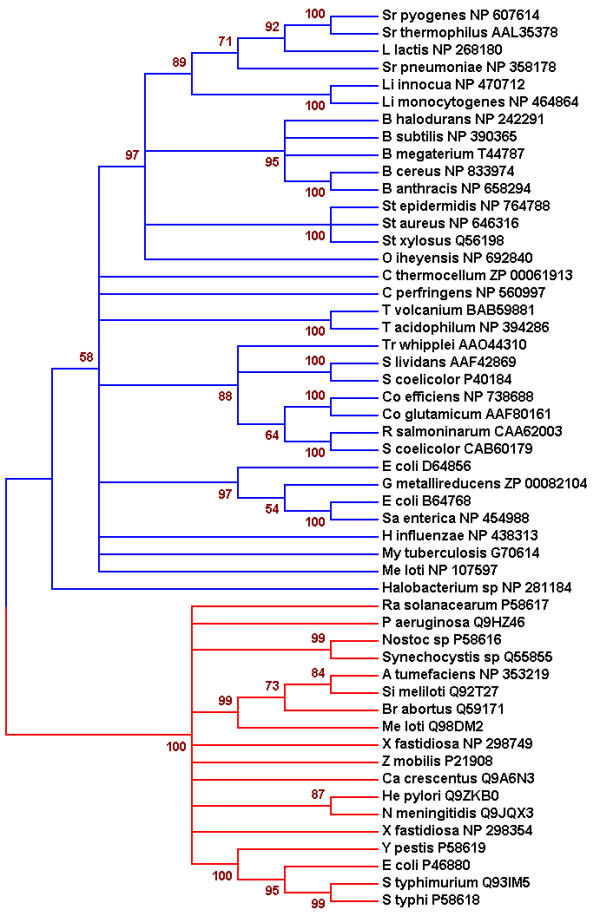

The 52 amino acid sequences that have been analyzed in this study were used to understand the relationship and the distinction between B. subtilis GlcK and other glucokinases. Multiple alignments of glucokinases showed a typical ATP binding site and ROK motif. However, phylogenetic analysis demonstrated two lineages of glucokinases (Fig. 1). The first lineage includes B. subtlis GlcK, which clustered with the 33 other glucokinases belonging primarily to Gram-positive bacteria and archaea. The lineage is indicated by three conserved C residues in the motif: CXCGX(2)GCXE (Fig. 2). In contrast, the second lineage does not contain this motif. All the glucokinases retain the conserved ATP binding motif. The well-characterized E. coli Glk (P46880) belongs to the second lineage and it has very low sequence identity (13.7%) to B. subtilis GlcK. Glucokinases in the second lineage generally have a sequence identity lower than 15.9% to the B. subtilis GlcK. Biochemical properties of glucokinases from both lineages are very similar but surprisingly the sequence identities among them are quite diverse. Therefore, it was intriguing to identify the role of the amino acid sequences that are uniquely conserved. Conserved C residues within the CXCGX(2)GCXE motif were of particular interest and maybe important for GlcK's enzymatic activity.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree of 52 microbial glucokinases. The phylogenetic tree shows two lineages of glucokinases, depicted as blue and red branches. Each of these lineages received high bootstrap support. Bootstrap values (500 sample runs) are expressed in percentage. GenBank accession number for each glucokinase is provided.

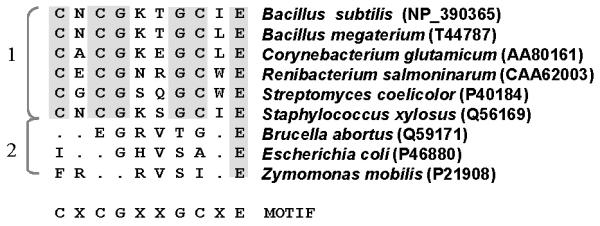

Figure 2.

A representative of microbial glucokinases from two lineages shows the presence or absence of the CXCGX(2)GCXE motif. B. subtilis [6], B. megaterium [11], C. glutamicum [20], R. salmoninarum [16], S. coelicolor [34], B. abortus [35], E. coli [36], and Z. mobilis [37] glucokinases are followed by their GenBank accession numbers.

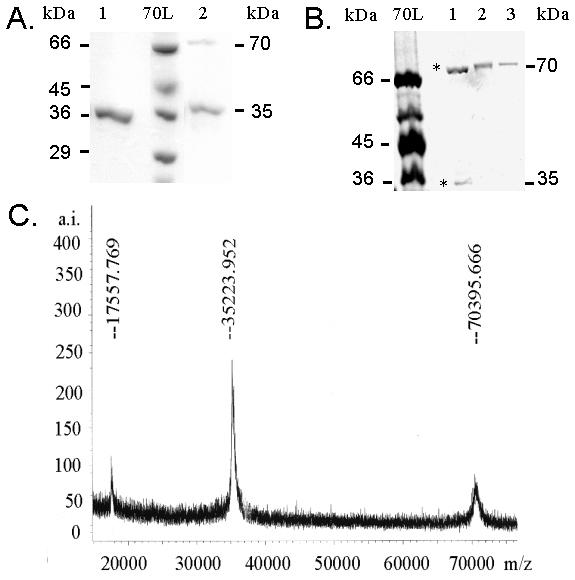

B. subtilis GlcK occurs in both monomeric and dimeric forms

Purified B. subtilis GlcK enzyme in soluble fractions was obtained after over-expression in E. coli RB791. The B. subtilis GlcK produced in E. coli was active as indicated by the ability to phosphorylate glucose. Under the reducing condition, GlcK showed a monomeric band of 35-kDa (Fig. 3A no. 1), while a homodimeric band of 70-kDa appeared under oxidative condition (Fig. 3B). Both forms were also observed under denaturating (SDS-PAGE) electrophoresis in the absence of reducing agent (Fig. 3A no. 2). This finding was supported by MALDI-TOF MS analysis of the GlcK, which also demonstrated two peaks of 35.2 kDa and 70.4 kDa, except for the protonated form (17.6 kDa) (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

B. subtilis GlcK can form a homodimer molecule. (A) GlcK dimerization is shown on 12% SDS-PAGE under reducing condition (1) and non-reducing condition (2). Molecular mass standard 70L (Sigma, Deisenhofen, Germany) with indicated size was used. (B) Cross-link experiment of GlcK was separated on an 8% polyacrylamide gel under non-reducing condition. Non-cross linked GlcK (1) demonstrates both monomeric and homodimeric form of GlcK (*), oxidized GlcK with 1% H2O2 (2), and 10 mM CuSO4.2H2O and 30 mM 1,10-phenantroline (3) shows only the homodimer. A MALDI-TOF mass spectrum shows the homodimer (70.4 kDa) and monomer (35.2 kDa) of GlcK. The 17.6 kDa peak is the protonated form of the sample.

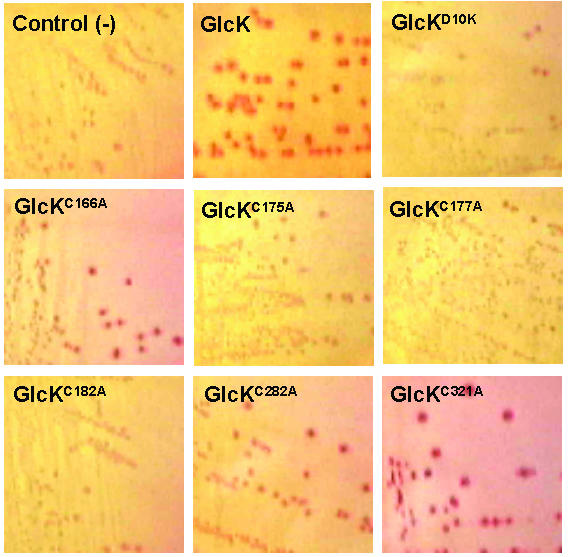

The C175, C177, and C182 are essential for B. subtilis GlcK enzymatic activity

Exploring the roles of specific amino acid residues is essential to understanding the structure and function of a protein. The B. subtilis GlcK consists of six C residues at positions 166, 175, 177, 182, 282, and 321. Three-conserved C residues at positions 175, 177, and 182 were detected as part of a distinctive amino acid sequence motif in the first lineage but not the second one. In order to understand the correlation of C residues with the protein's structure–function relationship, we replaced C with an A residue using site-directed mutagenesis. We then analyzed their enzymatic activity in vivo by functional complementation in E. coli glk mutant UE26. E. coli UE26 (ptsG ptsM glk) is unable to utilize glucose as carbon source and, therefore, forms colourless colonies on glucose-containing MacConkey plates, while the wild type forms red colonies. Since E. coli UE26 cannot transport glucose via phosphotransferase system, we supplemented the plates with 50 mM glucose and 100 mM fucose. Fucose leads to the induction of galactose permease, which can also transport glucose. This unphosphorylated glucose can then be metabolized only if it is converted to glucose 6-phosphate by glucokinase. Plasmids carrying the mutated B. subtilis glcK genes were transformed into E. coli UE26 and cultivated on MacConkey agar plates supplemented with glucose and fucose. As a positive control, plasmid carrying the wild type glcK was also transformed into E. coli UE26. Negative controls were E. coli UE26 alone and E. coli UE26 carrying the plasmid expressing GlcKD10K, in which D was replaced by K at the ATP binding motif. Wild type B. subtilis glcK in E. coli UE26 showed red colonies (Fig. 4). GlcKC166A, GlcKC282A, and GlcKC321A also produced red colonies similar to the wild type GlcK. These mutants showed various degrees of red colour, suggestive of differential enzymatic activity (Fig. 4). However, mutants GlcKC175A, GlcKC177A, and GlcKC182A showed colourless phenotypes, similar to the negative controls. This phenotype indicates a complete loss of glucokinase activity caused by the mutation (Fig. 4). This data suggests that C at position 175, 177, and 182 is essential for enzymatic activity of B. subtilis GlcK.

Figure 4.

Morphology of E. coli UE26 (ptsG ptsM glk) colonies expressing B. subtilis GlcK and its mutants on 50 mM glucose MacConkey agar supplemented with 100 mM fucose.

C321A mutation increases B. subtilis GlcK enzymatic activity, which maybe independent of the dimerization status

In order to confirm the enzymatic activity of GlcK mutants, we overproduced and purified the wild type GlcK, GlcKC166A, GlcKC282A, and GlcKC321A from soluble protein fractions of E. coli RB791. Induction of mutant GlcK was done with 1 mM IPTG at OD0.7. Three hours after induction, proteins were harvested and subjected to AKTA Purifier using Ni2+-NTA column. A 1000 ml culture yielded about 1 mg of pure GlcKC166A and about 10–15 mg of pure wild type GlcK, GlcKC282A, or GlcKC321A. The purified proteins were then tested for glucokinase activity in vitro, by coupling the phosphorylation of glucose to the formation of NADPH by glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenese. The GlcKC166A activity was 12.3 ± 6.2 μmol min-1 (mg protein)-1, which was comparable to the wild type GlcK activity. The GlcKC282A activity, 26.0 ± 7.4 μmol min-1 (mg protein)-1, was slightly higher than GlcKC166A and the wild type GlcK. However, GlcKC321A's activity was 5-fold higher than GlcKC166A's and the wild type's. This result was in agreement with the in vivo functional complementation assay. Mutants GlcKC166A and GlcKC282A displayed red phenotype of E. coli UE26 colonies similar to the wild type GlcK (Fig. 4). As the enzymatic activity was much higher than that of the wild type, the C321A mutation caused much darker red colonies (Fig. 4). Similar to the wild type GlcK, SDS-PAGE analysis showed that GlcKC166A, GlcKC282A, and GlcKC321A appeared both as monomers and as homodimers under the non-reducing condition. The data suggests that the enzymatic activity of GlcK was independent of the dimerization status. Therefore, the increasing enzymatic activity of the GlcKC321A may not correlate well with the dimerization status. Nevertheless, whether the GlcK activity is affected by different ratios of monomer to homodimer warrants further study.

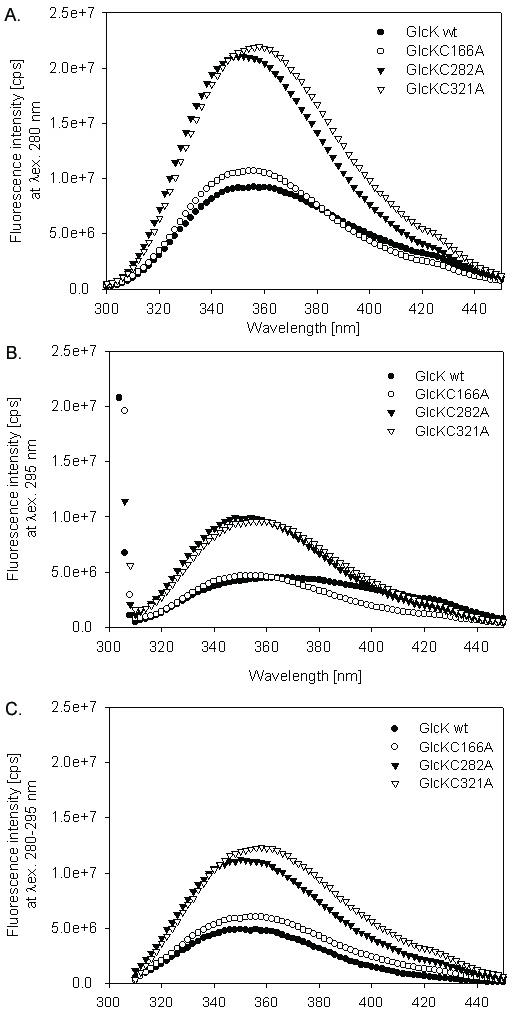

To prove that there were conformational changes of GlcKC282A and GlcKC321A, which had higher enzymatic activity, we analysed the GlcK mutants with fluorescence spectroscopy. Since the GlcK contains six tryptophan (W) and five tyrosine (Y) residues, excitation wavelengths of 280 and 295 nm were used to obtain emission spectra of the protein. Subtraction of W spectrum at λex.295 from the W-Y spectrum at λex.280 was done in order to obtain the separated spectrum of Y according to Isaev-Ivanov et al. [17]. GlcKC282A as well as GlcKC321A showed significant increased fluorescence intensity compared to the GlcKC166A, which has similar spectra to the wild type GlcK. This observation is indicative of changes in their structure due to the C mutation at 282 or 321. Increasing fluorescence intensities, as shown by GlcKC282A and GlcKC321A (Fig. 5), were due to conformational changes by these mutants leading to the re-positioning of tryptophan (λex.295) and tyrosine (λex.280–295) residues. Conformational changes by GlcKC321A were more pronounced as shown, not just by higher fluorescence intensity, but also a shift towards higher wavelengths (red shift) of the emission peak with respect to the wild type GlcK, GlcKC166A, and GlcKC282A (Fig. 5A, 5C). The red shift indicates a phenomenon similar to the effect of solvent reorganization. The enhanced fluorescence suggests a quenching mechanism that involves the thiol of C residue. Both red shift and enhanced fluorescence imply a loosening of packing interactions in the core of the protein and co-localization of C residues as well as W/Y residues that contribute to fluorescence [18,19]. In our case, these implications may cause an increased ability of glucokinase to phosphorylate glucose as shown by the increasing glucokinase activity of GlcKC321A (Fig. 4, 5).

Figure 5.

Fluorescence emission spectra of B. subtilis GlcK, GlcKC166A, GlcKC282A, and GlcKC321A, which were measured at excitation wavelength 280 nm (A), 295 nm (B), and subtraction of 280–295 nm. Samples (2.0 μM) were measured at 22°C in 50 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.5. The spectra have been corrected by the buffer values. Experiments had been repeated three times.

Discussion

We have shown that two lineages of glucokinases has evolved with the presence or absence of the CXCGX(2)GCXE motif. Glucokinase belongs to the ROK family with the hallmark [LIVM]X(2)G [LIVMFCT]GX [GA] [LIVMFA]X(8)GX(3–5) [GATP]X(2) G [RKH] motif [14,15]. Park et al., 2000 [20] reported that some glucokinases do not contain the ROK motif. In fact, most glucokinase sequences, retrieved by us, preserved the ROK motif. However, some of the ROK motifs belonging to the second lineage have one to four amino acid mutations. Within the ROK family, the B. subtilis GlcK was grouped together with B. subtilis Xyl repressor protein (XylR), putative B. subtilis fructokinase (YdhR), Streptococcus mutans fructokinase (ScrK) encoded within a sucrose regulon, and Zymomonas mobilis fructokinase (FruK) [14,15]. Dahl et al., 1995 [21] analyzed the interaction of fructose, fructose 6-phosphate, glucose, and glucose 6-phosphate on the binding of XylR into xylO. Interestingly, only glucose stimulated the XylR binding [21]. The XylR has a ROK motif and a CXCGX(2)GCXE motif. In contrast, Z. mobilis FruK, B. subtilis YdhR, and S. mutans ScrK contain ROK motifs but not the CXCGX(2)GCXE motif. Hence, the CXCGX(2)GCXE motif may correlate with glucose binding. This is a reasonable possibility considering that the GlcK mutants with cysteine substitution exhibited a loss of enzymatic activity (Fig. 4).

B. subtilis GlcK was present in both monomeric and dimeric forms (Fig. 3). Mutants GlcKC166A, GlcKC282A, and GlcKC321A were still able to form a homodimer as shown by SDS-PAGE, under non-reducing conditions. However, oxidation of GlcK led to the homodimer formation (Fig. 3B). The dimerization of GlcK is possibly due to the overall role of the ATPase domain. Proteins with the ATPase domain acquired the capacity to dimerize and bind to ATP in an active site between the two subunits [22-24]. The evidence for this comes from the overall structural symmetry between two domains of the ATPase as well as from the symmetric arrangement of the two phosphate binding loops [22]. The ATPase domain of GlcK is located between amino acid residues 6 – 27: FAGIDLGGTTIKLAFINQYGEI (phosphate 1), 109 – 126: IENDANIAALGEMWKGAGDG (connect 1), 135 – 149: VTLGTGVGGGIIANG (phosphate 2), 255 – 282: PSKIVLGGGVSRAGELLRSKVEKTFRKC (adenosine), and 295 – 308: IAALGNDAGVIGGA (connect 2).

Conclusions

Multiple alignments and phylogenetic analysis had led directly to valuable insights into the possible molecular function and the evolution of glucokinase. This study enabled us to classify microbial glucokinases into two distinct lineages, with or without the CXCGX(2)GCXE motif. The experimental study also identified the role of C residues in B. subtilis GlcK. The three-conserved C residues in that motif are clearly essential for GlcK activity. However, the C321A mutation led to higher GlcKC321A enzymatic activity with respect to the wild type's, suggesting more adequate glucose phosphorylation.

Methods

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this work are shown in Table 1. Both B. subtilis and E. coli were grown at 37°C in LB medium supplemented with the appropriate antibiotics.

Table 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study.

| Strains and plasmids | Relevant genotype or phenotype | Reference or source |

| Strains | ||

| B. subtilis 168 | wild type | BGSCa, 1A1 |

| E. coli | ||

| RB791 | F' [lacIq L8] hsdR+ hsdM | [32] |

| UE26 | F- ptsG2 ptsM1 glk7 rpsL150 | [33] |

| Plasmids | ||

| pMD496 | pQE9 derivative carrying glcK fused in frame to the His tag-coding region | [6] |

| pLM-GlcK [D22K] | pMD496 derivative carrying glcKD10K | This study |

| pLM-GlcK [C178A] | pMD496 derivative carrying glcKC166A | This study |

| pLM-GlcK [C187A] | pMD496 derivative carrying glcKC175A | This study |

| pLM-GlcK [C189A] | pMD496 derivative carrying glcKC177A | This study |

| pLM-GlcK [C194A] | pMD496 derivative carrying glcKC182A | This study |

| pLM-GlcK [C294A] | pMD496 derivative carrying glcKC282A | This study |

| pLM-GlcK [C333A] | pMD496 derivative carrying glcKC321A | This study |

a BGSC, Bacillus Genetic Stock Center, Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio

Multiple sequence alignments and phylogenetic analysis

Sequences for eukaryotic, bacterial and archaeal glucokinases and putative glucokinases were retrieved from the GenBank database. Those sequences were aligned using the Clustal method [25] with the MegAlign 4.0 program (DNAStar Co., Madison, WI). To confirm the conservative domain, the obtained CXCGX(2)GCXE motif was used as template for BLAST searching [26]. Neighbor joining distance trees of microbial glucokinases were produced using the phylogenetic package MEGA2 [27]. Amino acid differences between sequences were corrected for multiple substitutions using a gamma correction. In this correction, α, the shape parameter of the gamma distribution, was set to 2. Therefore, the distance between any two amino sequences is approximately equal to Dayhoff's PAM distance per site [27]. Support for the nodes within phylogenetic tree were evaluated by the bootstrap [28], which was done in 500 replicates of the whole data set.

Site-directed mutagenesis

D10K, C166A, C175A, C177A, C182A, C282A, or C321A was introduced in the glcK gene of B. subtilis using the Excite™ PCR-based site directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, LA Jolla, CA). The constructed plasmids were pLM-GlcK [D22K], pLM-GlcK [C178A], pLM-GlcK [C187A], pLM-GlcK [C189A], pLM-GlcK [C194A], pLM-GlcK [C294A], and pLM-GlcK [C333A] (Table 1). The coding sequences of the mutated glcKs were verified by DNA sequencing. Sequences of primers used to introduce the desired amino acid exchange are shown in Table 2. In brief, the amplified DNA fragment was subjected to DpnI digestion, which removed the pMD496 template DNA. Mutant plasmids were transformed into Epicurian Coli®XL1-Blue super-competent cells (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) and plated on LB medium supplemented with ampicillin (100 μg ml-1).

Table 2.

Sets of primers used for site-directed mutagenesis in this study

| Mutation | Primer setsa |

| D10K | 5' tgcgggcattaagctgggaggaacgacgat 3' |

| 5' aaccatatctcgtccatggatccgtgatgg 3' | |

| C166A | 5' ggccatattgccagcatccctgaaggcgga 3' |

| 5' gatttctccgccggcgccatttataccatg 3' | |

| C175A | 5' gcgcccgccaactgcggcaaaacgggctgt 3' |

| 5' tccgccttcagggatgctgcaaatatggcc 3' | |

| C177A | 5' tgcaacgccggcaaaacgggctgtatcgaa 3' |

| 5' gggcgctccgccttcagggatgctgcaaat 3' | |

| C182A | 5' ggcaaaacgggcgctatcgaaacaattgcg 3' |

| 5' gcagttgcagggcgctccgccttcagggat 3' | |

| C282A | 5' cgcaaagccgcgtttccgcgggcagcccaa 3' |

| 5' gaatgttttctcgacttttgatctcagcag 3' | |

| C321A | 5' catcaaaatgcttaaaattgtgtaaatgaa 3' |

| 5' tttcagccattcatttttagcgatccaagc 3' |

a Underlined is mutated nucleotide.

DNA sequencing

Pure plasmids, carrying either glcK or one of its mutants (Table 1), were prepared with the Nucleobond Midiprep kit according to the manufacturers suggestions (Macherey-Nagel, Dueren, Germany). Nucleotide sequences were determined by the cycle sequencing technique using the automated capillary sequencer, ABI PRISM 310/377 (Perkin Elmer Co., Foster City, CA). Sequencing primers used were: 5'CGGATAA CAATTTCACACAG3', 5'CTTCT GAGGTCATTACTGG3', 5'GCTGCGCTCGGGG AAATGTG3', and 5'GATACGCCGCCGCCAAGAAC3'. DNA analysis was carried out by DNAStar software (DNAStar Co., Madison, WI).

Protein overproduction and purification

Overexpression of [His]6-tagged-GlcK [6] and its mutated GlcKs was accomplished in E. coli RB791 harbouring the corresponding plasmids (Table 1). Cells were harvested three hours after induction with 0.1 mM IPTG at an OD600 of ~0.7. The pellet was then resuspended and sonicated in lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl and 20 mM Tris-Cl pH 7.5). Over-produced soluble proteins were purified from the supernatant as previously described [6]. The crude extract of cells was quickly passed over a Ni2+-loaded HiTrap chelating column (Pharmacia, Freiburg, Germany), which had been equilibrated with 40 column volumes of washing buffer (200 mM NaCl, 20 mM Imidazole and 5 mM Tris-Cl pH 7.5). Pure protein was eluted by a linear gradient using elution buffer (200 mM NaCl, 500 mM Imidazole and 5 mM Tris-Cl pH 7.5) at a flow rate of 0.5 ml min-1. Eluted protein aliquots of 0.5 ml were analysed on 12% SDS-PAGE. The GlcK concentration was determined by absorption measurement at 280 nm in 50 mM Tris-Cl pH 7.

In vivo functional complementation of B. subtilis GlcK mutants in E. coli UE26

E. coli strain UE26 (ptsG ptsM glk) was transformed with plasmids carrying wild type glcK or glcK mutants. In vivo glucokinase activities were observed by monitoring colonies' colour shift from white to red on MacConkey agar. The agar was supplemented with 50 mM glucose and 100 mM fucose [6].

In vitro assay of glucokinase activity

Enzymatic activity of wild type or mutated GlcK was quantified in vitro by a method described previously [6]. Specific glucokinase activity was determined in a coupled enzyme assay by the method of Seno and Charter [29] in a solution consisting of 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 20 mM glucose, 25 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM NADP, 1 mM ATP, and 1 U of glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PDH). The G6PDH activity was assayed by monitoring the change in the optical density at 340 nm at 32°C with NADP as a cofactor.

Analysis of protein multimerization with SDS PAGE, oxidative cross-linking, and MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry

GlcK was subjected to reducing or non-reducing conditions by using loading buffer (0.1% Bromphenolblue, 16% Glycerol, 4% SDS, and 55 mM Tris-Cl pH 6.8) with or without 10% β-mercaptoethanol. The samples were analysed on 12% SDS-PAGE. Oxidative cross-linking was carried out either with H2O2 or with a complex of Cu(II) and 1,10-phenantroline. The procedure for the oxidative cross-linking of glucokinase was carried out as previously described [30] using 10 μg of glucokinase and analysing using an 8% SDS-PAGE. In order to remove the reductant, samples were dialyzed for several hours at 4°C in buffer (5 mM Tris-Cl pH 8.4, 1 mM EDTA and 1 mM DTT) containing 8 M, 5 M, or without urea [31]. Multimerization and molecular mass determination of B. subtilis GlcK was performed on a Biflex™ III Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) (Bruker Daltonik GmbH, Bremen, Germany) equipped with a nitrogen laser at λ = 337 nm at the Institute for Biochemistry, University of Erlangen-Nuremberg.

Fluorescence measurement

Fluorescence studies, carried out on a Spex Fluorolog spectrometer (Edison, NJ, USA), were used to determine spectral changes of GlcK and its mutants. The excitation wavelength was set to 280 nm or 295 nm and the emission was recorded in the range of 300 nm to 450 nm. For these measurements, the slit widths were set to 2.2 mm. Fluorescence measurements were carried out at 22°C.

Authors' contributions

LRM carried out all aspects of the work including drafted the manuscript. FMM involved in the in silico study and supervised the writing of the manuscript. MKD was supported by DFG and Fonds der Chemischen Industrie and supervised the experimental studies.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

This paper is dedicated to Dr. Michael K. Dahl, who passed away on May 4, 2003. We are grateful to U. Ehmann, S. Schoenert, P. Schubert, and T. Buder for their interest and help. We would like to thank T. Bonk at the Institute for Biochemistry, University of Erlangen-Nuremberg for assistance with the MALDI-TOF MS and B. Scott of the Faculty of Medicine, University of Ottawa, for critical reading of the manuscript. The experimental work was carried out in the laboratories of W. Hillen (University of Erlangen-Nuremberg) and W. Boos (University of Konstanz).

Contributor Information

Lili R Mesak, Email: lrmesak@yahoo.com.

Felix M Mesak, Email: Felix.Mesak@orcc.on.ca.

Michael K Dahl, Email: lrmesak@yahoo.com.

References

- Anderson CM, McDonald RC, Steitz TA. Sequencing a protein by x-ray crystallography. I. Interpretation of yeast hexokinase B at 2.5 A resolution by model building. J Mol Biol. 1978;123:1–13. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(78)90373-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu LZ, Zhang W, Weber IT, Harrison RW, Pilkis SJ. Site-directed mutagenesis studies on the determinants of sugar specificity and cooperative behavior of human beta-cell glucokinase. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:27458–27465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veiga-da-Cunha M, Courtois S, Michel A, Gosselain E, Van Schaftingen E. Amino acid conservation in animal glucokinases. Identification of residues implicated in the interaction with the regulatory protein. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:6292–6297. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.11.6292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahalingam B, Cuesta-Munoz A, Davis EA, Matschinsky FM, Harrison RW, Weber IT. Structural model of human glucokinase in complex with glucose and ATP: implications for the mutants that cause hypo- and hyperglycemia. Diabetes. 1999;48:1698–1705. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.9.1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson JE. Isozymes of mammalian hexokinase: structure, subcellular localization and metabolic function. J Exp Biol. 2003;206:2049–2057. doi: 10.1242/jeb.00241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skarlatos P, Dahl MK. The glucose kinase of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:3222–3226. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.12.3222-3226.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito S, Fushinobu S, Yoshioka I, Koga S, Matsuzawa H, Wakagi T. Structural basis for the ADP-specificity of a novel glucokinase from a hyperthermophilic archaeon. Structure (Camb) 2001;9:205–214. doi: 10.1016/S0969-2126(01)00577-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuge H, Sakuraba H, Kobe T, Kujime A, Katunuma N, Ohshima T. Crystal structure of the ADP-dependent glucokinase from Pyrococcus horikoshii at 2.0-A resolution: a large conformational change in ADP-dependent glucokinase. Protein Sci. 2002;11:2456–2463. doi: 10.1110/ps.0215602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen T, Reichstein B, Schmid R, Schonheit P. The first archaeal ATP-dependent glucokinase, from the hyperthermophilic crenarchaeon Aeropyrum pernix, represents a monomeric, extremely thermophilic ROK glucokinase with broad hexose specificity. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:5955–5965. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.21.5955-5965.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner E, Marcandier S, Egeter O, Deutscher J, Götz F, Brückner R. Glucose kinase-dependent catabolite repression in Staphylococcus xylosus. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:6144–6152. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.21.6144-6152.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Späth C, Kraus A, Hillen W. Contribution of glucose kinase to glucose repression of xylose utilization in Bacillus megaterium. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:7603–7605. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.23.7603-7605.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosana-Ani L, Skarlatos P, Dahl MK. Putative contribution of glucose kinase from Bacillus subtilis to carbon catabolite repression (CCR): a link between enzymatic regulation and CCR ? FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;171:89–96. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(98)00585-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jankovic I, Bruckner R. Carbon catabolite repression by the catabolite control protein CcpA in Staphylococcus xylosus. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol. 2002;4:309–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titgemeyer F, Reizer J, Reizer A, Saier MH., Jr Evolutionary relationships between sugar kinases and transcriptional repressors in bacteria. Microbiology. 1994;140:2349–2354. doi: 10.1099/13500872-140-9-2349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falquet L, Pagni M, Bucher P, Hulo N, Sigrist CJ, Hofmann K, Bairoch A. The PROSITE database, its status in 2002. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:235–238. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Concha MI, Leon G. Cloning, functional expression and partial characterization of the glucose kinase from Renibacterium salmoninarum. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2000;186:97–101. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(00)00124-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaev-Ivanov VV, Kozlov MG, Baitin DM, Masui R, Kuramitsu S, Lanzov VA. Fluorescence and excitation Escherichia coli RecA protein spectra analyzed separately for tyrosine and tryptophan residues. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2000;376:124–140. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2000.1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beechem JM, Brand L. Time-resolved fluorescence of proteins. Annu Rev Biochem. 1985;54:43–71. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.54.070185.000355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos P, Coste T, Piemont E, Lessinger JM, Bousquet JA, Chapus C, Kerfelec B, Ferard G, Mely Y. Time-resolved fluorescence allows selective monitoring of Trp30 environmental changes in the seven-Trp-containing human pancreatic lipase. Biochemistry. 2003;42:12488–12496. doi: 10.1021/bi034900e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SY, Kim HK, Yoo SK, Oh TK, Lee JK. Characterization of glk, a gene coding for glucose kinase of Corynebacterium glutamicum. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2000;188:209–215. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(00)00238-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl MK, Schmiedel D, Hillen W. Glucose and glucose-6-phosphate interaction with Xyl repressor proteins from Bacillus spp. may contribute to regulation of xylose utilization. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:5467–5472. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.19.5467-5472.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bork P, Sander C, Valencia A. An ATPase domain common to prokaryotic cell cycle proteins, sugar kinases, actin, and hsp70 heat shock proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:7290–7294. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.16.7290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuser PR, Krauchenco S, Antunes OA, Polikarpov I. The high resolution crystal structure of yeast hexokinase PII with the correct primary sequence provides new insights into its mechanism of action. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:20814–20821. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M910412199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou CC, Forouhar F, Yeh YH, Shr HL, Wang C, Hsiao CD. Crystal structure of the C-terminal 10-kDa subdomain of Hsc70. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:30311–30316. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304563200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Tamura K, Nei M. MEGA: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis software for microcomputers. Comput Appl Biosci. 1994;10:189–191. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/10.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution. 1985;39:783–791. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1985.tb00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seno ET, Chater KF. Glycerol catabolic enzymes and their regulation in wild type and mutant strains of Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) J Gen Microbiol. 1983;129:1403–1413. doi: 10.1099/00221287-129-5-1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traut RR, Casiano C, Zecherle N. Cross-linking of protein subunits and ligands by the introduction of disulphine bonds. In: Creighton TE, editor. Protein function, a practical approach. NY: IRL Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers RK, Herrmann H, Franke MM. Characterization of disulfide crosslink formation of human vimentin at the dimer, tetramer, and intermediate filament levels. Journal of Structural Biology. 1996;117:55–69. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1996.0069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brent R, Ptashne M. Mechanism of action of the lexA gene product. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:4202–4208. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.7.4204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boos W, Ehmann U, Forkl H, Klein W, Rimmele M, Postma P. Trehalose transport and metabolism in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:3450–3461. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.6.3450-3461.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahr K, van Wezel GP, Svensson C, Krengel U, Bibb MJ, Titgemeyer F. Glucose kinase of Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2): large-scale purification and biochemical analysis. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2000;78:253–261. doi: 10.1023/A:1010234916745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essenberg RC. Cloning and characterization of the glucokinase gene of Brucella abortus 19 and identification of three other genes. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:6297–6300. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.21.6297-6300.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer D, Schneider-Fresenius C, Horlacher R, Peist R, Boos W. Molecular characterization of glucokinase from Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:1298–1306. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.4.1298-1306.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnell WO, Kyung CY, Conway T. Sequence and genetic organisation of a Zymomonas mobilis gene cluster that encodes several enzymes of glucose metabolism. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:7227–7240. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.12.7227-7240.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]