Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study is to report the short-term efficacy of aflibercept in the treatment of neovascular age-related macular degeneration (AMD) with associated retinal pigment epithelial detachment (PED) which is refractory or develops tachyphylaxis to bevacizumab and ranibizumab.

Methods

The method comprised a retrospective review of the medical records of patients with neovascular AMD and associated PEDs recently treated with aflibercept and previously treated with bevacizumab and ranibizumab.

Results

Three eyes of three female patients of ages 49, 55, and 65 years old with large serous PEDs and subretinal fluid (SRF) associated with occult choroidal neovascularization and neovascular AMD were treated with aflibercept after intravitreal bevacizumab and/or ranibizumab failed to resolve the lesions. All had complete resolution of SRF and complete or near-complete resolution of the PEDs after aflibercept injections over a 3-month period. Visual acuity improved in all three eyes.

Conclusion

Intravitreal aflibercept may be an effective treatment option for serous PED in neovascular AMD patients after bevacizumab and ranibizumab have previously failed. Larger studies with longer follow-up are required to determine the role of aflibercept in treatment of PED in neovascular AMD.

Keywords: aflibercept, retinal pigment epithelial detachment, age-related macular degeneration

Introduction

Retinal pigment epithelial detachments (PEDs) occur in up to 62% of eyes with advanced age-related macular degeneration (AMD).1 Numerous treatment options have been employed for PEDs in AMD, including laser therapies and intravitreal injections of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) antibodies.2 However, eyes with PEDs were excluded from the larger clinical trials that used macular laser,3 photodynamic therapy,4 or ranibizumab5, 6 to treat neovascular AMD; therefore, the efficacy of such options is still unclear for eyes with choroidal neovascularization (CNV) and PEDs.

Aflibercept is a recombinant fusion protein, which binds all isomers of the VEGF-A family and placental growth factor. It has higher binding affinity for VEGF and was shown to be clinically equivalent to ranibizumab, in two large studies, in treating neovascular AMD.7

We report three cases with large PEDs associated with neovascular AMD successfully treated with aflibercept after failed treatment with bevacizumab and ranibizumab.

Case reports

Case 1

A 49-year-old Caucasian female with a history of bilateral neovascular AMD treated with bevacizumab × 1 OD and × 2 OS, elsewhere presented with a large serous PED OD and multiple small PEDs OS. Best-corrected visual acuities (BCVAs) were 20/60 OD and 20/25 OS. The PED OD resolved after three ranibizumab injections. However, the left eye developed a single, large PED with subretinal fluid (SRF). Fluorescein angiogram (FA) and indocyanine green confirmed neovascular AMD with occult CNV and multiple macular and peripheral drusen. The PED OS worsened with increased SRF despite eight ranibizumab injections over 9 months, including a trial of two increased doses (1.0 mg) of ranibizumab. BCVA OS dropped to 20/70. After one intravitreal injection of aflibercept, the SRF resolved with nearly complete resolution of the PED. Two additional injections of aflibercept were given and the foveal contour normalized. BCVA OS 3 months after the initial aflibercept injection was 20/25 (Figure 1).

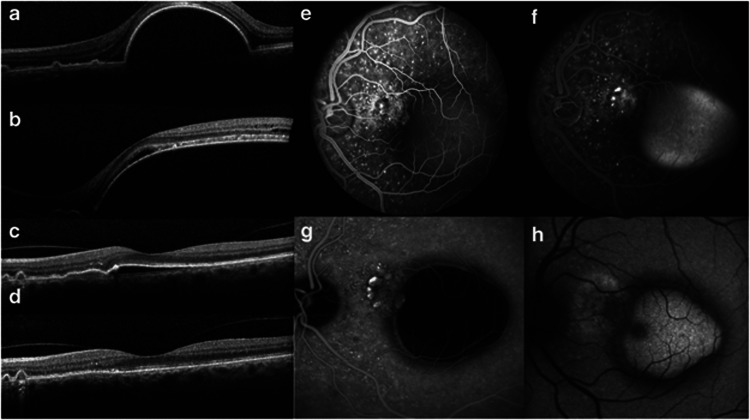

Figure 1.

Images from Case 1: a 49-year-old Caucasian female with a history of bilateral neovascular age-related macular degeneration. (a–d). Heidelberg SPECTRALIS spectral domain optical coherence tomography of the left eye. (a) Large retinal pigment epithelial detachment (PED) with subretinal fluid (SRF) on presentation. Patient previously received two bevacizumab and one ranibizumab injections. Best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was 20/50. (b) Enlarging PED with SRF despite seven monthly ranibizumab injections. Dosage was doubled to 1 mg in the most recent two injections. BCVA dropped to 20/70. (c) Near resolution of PED with complete resolution of SRF 1 month after a single aflibercept injection. BCVA improved to 20/20. (d) Continuing improvement of PED with normalization of foveal contour after two additional aflibercept injections given over 2 months. BCVA was 20/25. (e) Early and (f) late fluorescein angiography images of the left eye showing multiple macular drusen, late leakage at the base of the PED suggestive of choroidal neovascularization (CNV), and pooling of dye within the PED. (g) Indocyanine green image of the left eye revealing several hyperfluorescent spots from the choroidal circulation, but no late leakage indicative of polyps. In later frames, there is diffuse leakage of dye into the PED space, suggesting the presence of CNV. (h) Autofluorescence image of the left eye showing hyperautofluorescence near the CNV.

Case 2

A 55-year-old Caucasian female with neovascular AMD OD status post five monthly ranibizumab intravitreal injections presented with a large PED associated with CNV. FA confirmed occult CNV OD. Initial BCVAs were 20/25 OD and 20/20 OS. The PED OD initially improved with two bevacizumab and one ranibizumab intravitreal injections over a 7-month period, but the PED later worsened despite three increased doses of ranibizumab injections (1.5 mg) over a 2-month period. BCVA decreased to 20/30 OD. One aflibercept injection was then given, resulting in a near-complete resolution of the PED. This was followed by two monthly aflibercept injections and BCVA returned to 20/20 OD with complete resolution of SRF and the PED (Figure 2).

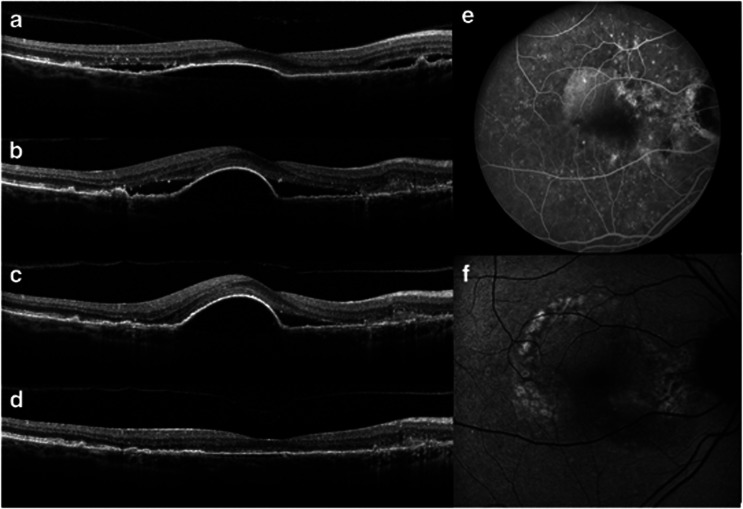

Figure 2.

Images from Case 2: a 55-year-old Caucasian female with neovascular age-related macular degeneration in her right eye. (a–d) Images from Heidelberg SPECTRALIS spectral domain optical coherence tomography of the right eye. (a) Moderate retinal pigment epithelial detachment (PED) with adjacent subretinal fluid (SRF). Patient received six ranibizumab and one bevacizumab injections before this visit. Best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was 20/20 and the patient was observed. (b) Enlarging PED with increasing SRF. BCVA was 20/25. Ranibizumab treatment resumed. (c) Persistent PED with SRF nasally, despite three additional monthly ranibizumab injections. BCVA dropped to 20/30. (d) Nearly complete resolution of PED with complete resolution of SRF 1 month after a single aflibercept injection. BCVA was 20/30. BCVA returned to 20/20 after one more aflibercept injection. (e) Fluorescein angiography image of right eye showing staining from multiple macular drusen, pooling of dye within the serous PED, and area of possible occult choroidal neovascularization nasal to PED. (f) Autofluorescence image of the right eye showing areas of hypo- and hyperautofluorescence consistent with drusenoid changes.

Case 3

A 65-year-old East Indian female with neovascular AMD OS status post three bevacizumab injections presented with a large subfoveal PED without SRF OS. BCVAs were 20/20 OD and 20/40 OS. FA confirmed the presence of an occult CNV OS. This PED enlarged with persistent SRF, despite switching to four monthly injections of ranibizumab. BCVA OS remained at 20/40. One injection of aflibercept resulted in significant improvement of the PED and resolution of SRF. A second injection of aflibercept was given two months later, and BCVA OS improved to 20/25.

Discussion

PEDs have a significant impact on vision with no proven treatment options. An average vision loss of more than three lines over 1 year was seen in about 50% of patients with a newly diagnosed PED.8 Polypoidal vascular choroidopathy (PCV) is also known to cause large PEDs and are less responsive to ranibizumab and bevacizumab monotherapy.9 Although PCV is possible, the demographics of cases 1 and 2 and the presence of multiple drusen in all three cases make AMD a more likely diagnosis.

Cases 1 and 2 possibly represent tachyphylaxis, whereas case 3 more likely represents failure to bevacizumab and/or ranibizumab. Tachyphylaxis is the reduced efficacy of a drug when used repeatedly over a short period of time, with no response occurring when the dosage is increased.10 The incidence of tachyphylaxis to anti-VEGF in AMD ranged from 2% in ranibizumab11 to 8.5% in bevacizumab.12 It has been shown that in AMD patients who developed tachyphylaxis to ranibizumab or bevacizumab, 81% demonstrated some response after switching therapies.13

Although aflibercept may be effective, the dramatic response was not universal in all patients. Six other patients with large PEDs secondary to neovascular AMD, who failed other treatment, were treated with aflibercept at our institution. Six of these patients had unchanged PED size after switching to aflibercept—three had complete resolution of SRF associated with their PED, two had fluctuation of SRF, and one never developed SRF at 3-month follow-up. Visual acuity improved in one patient, remained stable in four patients, and worsened in one patient. Although response varies, the dramatic, short-term resolution of the PEDs in the three recalcitrant cases suggests that aflibercept may be useful in the treatment of large PEDs associated with occult CNV. However, larger randomized controlled studies are necessary to determine its role in the treatment of PED in neovascular AMD.

Dr Mieler receives compensation as a consultant for Alcon, Allergan, Genentech, Alimera Sciences, and QLT/Novartis. Dr Lim receives compensation as a consultant for Genentech, Regeneron, Allergan, QLT, Quark, and Santen. She has also received royalties from Informa and compensation for developing the Johns Hopkins CME programs, and she has an RPB grant. Dr Leiderman receives compensation as a consultant for Alcon. The remaining authors declare no potential conflict of interest.

References

- Coscas F, Coscas G, Souied E, Tick S, Soubrane G. Optical coherence tomography identification of occult choroidal neovascularization in age-related macular degeneration. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;144 (4:592–599. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepple K, Mruthyunjaya P. Retinal pigment epithelial detachments in age-related macular degeneration: classification and therapeutic options. Semin Ophthalmol. 2011;26 (3:198–208. doi: 10.3109/08820538.2011.570850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macular Photocoagulation Study Group. Laser photocoagulation of subfoveal neovascular lesions in age-related macular degeneration. Results of a randomized clinical trial. Arch Ophthalmol. 1991;109 (9:1220–1231. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1991.01080090044025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias L. Treatment of retinal pigment epithelial detachment with antiangiogenic therapy. Clin Ophthalmol. 2010;4:369–374. doi: 10.2147/opth.s9307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld PJ, Brown DM, Heier JS, Boyer DS, Kaiser PK, Chung CY, MARINA Study Group et al. Ranibizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2006;355 (14:1419–1431. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DM, Kaiser PK, Michels M, Soubrane G, Heier JS, Kim RY, ANCHOR Study Group et al. Ranibizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2006;355 (14:1432–1444. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohr M, Kaiser PK. Intravitreal aflibercept injection for neovascular (wet) age-related macular degeneration. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2012;13 (4:585–591. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2012.658368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauleikhoff D, Loffert D, Spital G, Radermacher M, Dohrmann J, Lommatzsch A, et al. Pigment epithelial detachment in the elderly. Clinical differentiation, natural course and pathogenetic implications. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2002;240 (7:533–538. doi: 10.1007/s00417-002-0505-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho M, Barbazetto IA, Freund KB. Refractory neovascular age-related macular degeneration secondary to polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;148 (1:70–78. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2009.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder S. Loss of reactivity in intravitreal anti-VEGF therapy: tachyphylaxis or tolerance. Br J Ophthalmol. 2012;96 (1:1–2. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2011-301236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eghoj MS, Sorensen TL. Tachyphylaxis during treatment of exudative age-related macular degeneration with ranibizumab. Br J Ophthalmol. 2012;96 (1:21–23. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2011.203893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forooghian F, Cukras C, Meyerle CB, Chew EY, Wong WT. Tachyphylaxis after intravitreal bevacizumab for exudative age-related macular degeneration. Retina. 2009;29 (6:723–731. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3181a2c1c3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasperini JL, Fawzi AA, Khondkaryan A, Lam L, Chong LP, Eliott D, et al. Bevacizumab and ranibizumab tachyphylaxis in the treatment of choroidal neovascularisation. Br J Ophthalmol. 2012;96 (1:14–20. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2011.204685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]