Abstract

E2F transcription factors control the expression of genes involved in a variety of essential cellular processes and consequently their activity needs to be tightly regulated. Protein-protein interactions are thought to be key modulators of E2F activity. To gain insight into the mechanisms that regulate the activity of E2F2, we searched for novel proteins that associate with this transcription factor. We show that the nuclear protein ALY (THO complex 4), originally described as a transcriptional co-activator, associates with DNA-bound E2F2 and represses its transcriptional activity. The capacity of ALY to modulate gene expression was analyzed with expression microarrays by characterizing the transcriptome of E2F2 expressing HEK293T cells in which ALY was either overexpressed or silenced. We show that ALY influences the expression of more than 400 genes, including 98 genes bearing consensus E2F motifs. Thus, ALY emerges as a novel E2F2-interacting protein and a relevant modulator of E2F-responsive gene expression.

The E2F family of transcription factors (E2F1–8) was originally discovered for its pivotal role in controlling cell cycle progression through the temporary modulation of genes involved in DNA replication and G1/S transition (1–2). Based on their capacity to promote cell cycle progression, E2F family members have been classically divided into two main subclasses: “activator E2Fs” (E2F1–3) and “repressor E2Fs” (E2F4–8). “Activator E2Fs” can induce the transcription of target genes and promote cell cycle progression. By contrast, “repressor E2Fs” inhibit gene expression and are believed to be required for cell cycle exit (3). Recently performed genome-wide studies have revealed that the spectrum of biological activities governed by E2Fs is broader than originally proposed. Thus, E2F family members have been shown to regulate a wide range of essential cellular processes including apoptosis, mitosis, chromosome organization, macromolecule metabolism, autophagy, or cell differentiation (4–5). Consequently, E2F activity needs to be tightly regulated to maintain cellular homeostasis. In fact, deregulated E2F activity is a common hallmark of human cancers (6).

Multiple mechanisms contribute to regulate the transcriptional activity of individual E2F family members. These mechanisms include tissue- and cell cycle-specific expression (7), differential subcellular localization (8–9), and post-translational modifications, such as phosphorylation (10), acetylation (11–12), and ubiquitination (13). Protein-protein interactions play a particularly relevant role in modulating the activity of E2Fs. In fact, the current model of cell cycle regulation is based on a series of temporary interactions between E2F and retinoblastoma (RB)1, modulated by cyclin/CDK-induced phosphorylation events, which determine the timely expression of genes necessary for cell cycle entry and progression (14). Although several E2F-interacting proteins have been already identified, the complex interaction networks required for the precise regulation of E2F activity suggest that the list of proteins that bind and modulate E2F activity is likely to be incomplete.

Yeast two-hybrid screenings have been frequently used to search for potential E2F-interacting partners (15). For instance, following this approach RYBP (Ring-1 and YY-1 binding protein) was found to associate with the marked box domain of E2F2 or E2F3, leading to the synergistic activation of the CDC6 promoter (16). In recent years, however, MS-based approaches have become increasingly adopted as the method of choice for protein-protein interaction studies. In this regard, affinity purification coupled to MS analysis has been particularly useful in the identification of native RB/E2F repressor complexes (15).

In the present work, we combined protein immunoprecipitation with MS analysis to search for novel proteins associating with E2F2, an E2F member that is critical for cell cycle regulation (17–19). Our analysis identified 94 candidates that may represent novel E2F2-binding proteins. Among those, we validated the nuclear protein ALY as a bona fide E2F2-interacting partner that binds the central region of E2F2, encompassing the dimerization domain and the marked box. Our data indicate that ALY is recruited to promoter-bound E2F2, thereby inhibiting E2F2 transcriptional activity. The ability of ALY to modulate gene transcription in E2F2-expressing cells was further corroborated using expression microarray analysis. Altogether, our data demonstrate that ALY associates with and modulates the transcriptional activity of E2F2.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plasmids and Cloning Procedures

Mammalian expression plasmids pRc-CMV-HA-E2F2 and pCMV-T7-ALY were kindly provided by Dr. Joseph R. Nevins (Duke University Medical Center, USA) and Dr. Rudolf Grosschedl (Max Planck Institute of Immunobiology and Epigenetics, Germany), respectively. DNA fragments encoding various E2F2 amino acid segments were amplified by PCR using pRc-CMV-HA-E2F2 as a template. These fragments were cloned into the HindIII/BamHI restriction sites of the pEYFP-C1 vector (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA) to generate a set of plasmids encoding E2F2 deletion mutants tagged with yellow fluorescence protein (YFP) and hemagglutinin (HA). The plasmid encoding the interstitial deletion mutant YFP-E2F2 (Δ197–358)-HA was generated by excising a DNA fragment encoding E2F2 (Δ197–358) from pUC57-HA-E2F2 (Δ197–358) (Genscript), and subcloning it into pEYFP-C1 using the HindIII/BamHI restriction sites.

ALY-directed shRNA plasmids were based on the pSUPER.retro.puro silencing vector (OligoEngine, Seattle, WA). ALY-specific complementary oligonucleotides were designed using the siRNA target designer tool (Promega, Madison, WI), annealed and cloned into the vector using the HindIII and BglI sites. The pSUPER-Scramble plasmid was used as negative control.

Luciferase assay reporter plasmids pGL2_3xE2F-wt-luc and pGL2_3xE2F-mut-luc were kindly provided by Dr. Stefan Gaubatz (University of Wurzburg, Germany). pGL2_CHK1-wt-luc and pGL2_CHK1-mut-luc reporter plasmids were constructed by subcloning the genomic region of CHK1 (+119/+248), containing either intact or mutated E2F sites (Genscript, Piscataway, NJ), into the pGL2-Basic vector (Promega). For the generation of pGL2_CDT1 and pGL2_XBP1 reporter vectors, the +316/+603 bp region of CDT1 gene and the +57/+137 bp region of XBP1 gene were first amplified by PCR using human genomic DNA as a template, and then cloned into the pGL2-Basic vector.

Newly generated plasmids were confirmed by DNA sequencing. The sequences of the PCR primers and oligonucleotides used for cloning are provided in supplemental Table S1.

Cell Culture, Transfections, and Gene Expression Assays

Human embryonic kidney 293T cells (HEK293T) were maintained in Dulbecco's modified medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Transfections were carried out using the calcium phosphate procedure.

Mouse T cell preparation, culture and stimulation were carried out as previously described (18).

For luciferase reporter assays, HEK293T cells were plated at a density of 2 × 105 cells/well on a six-well plate and 24 h later, cotransfected with 20 ng of the Renilla luciferase reporter plasmid (pRL-TK, Promega), 200 ng of the Firefly luciferase reporter plasmid, and varying amounts of E2F2 and ALY-expressing or ALY-silencing plasmids. The total amount of DNA in the reaction mixtures was brought to 2 μg using empty pRc-CMV vector and pSUPER-scramble plasmid. Using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega), Firefly luciferase activity was measured 48 h after transfection and, normalized to the transfection efficiency estimated through the Renilla luciferase activity in each sample. The luciferase activity measured in cells transfected only with the appropriate reporter vectors was used as a reference to calculate fold induction.

Quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) analyses were performed as described previously (20). PCR primers are shown in supplemental Table S1. Reactions were carried out in triplicate, and the results normalized using GTF3C5 as an internal control.

Co-immunoprecipitation and Oligoprecipitation

For protein immunoprecipitation, HEK293T cells were collected 48 h after transfection and lysed in buffer containing 10 mm trisHCl pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm EGTA pH 8.0, 0.2 mm Ortovanadate, 1 × protease inhibitor mixture (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) and 0.5% Nonidet P-40. Cell lysates were cleared of insoluble debris by centrifugation (15 min, 13,000 rpm, 4 °C), preincubated with uncoupled magnetic beads (Dynabeads, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) (3 h, 4 °C), and finally incubated with the specific antibody (HA probe sc7392, anti-ALY sc-32311 or anti-SV40Tag (anti-T) sc-147, SantaCruz Biotechnology. Inc, Santa Cruz, CA) coupled to magnetic beads (90 min, 4 °C). Following incubation, beads were washed several times with lysis buffer and finally, immunoprecipitated proteins were eluted by incubating the beads in 0.1 m glycine pH 2.5 overnight with continuous vortexing, and neutralized with 0.5 m TrisHCl pH 7.5. Co-immunoprecipitation assays to map E2F2 and ALY interaction domains were carried out with GFP-trap-M system (Chromotek, Martinsried, Germany) following manufacturer's instructions.

For oligoprecipitation assays, precleared cell lysates were incubated with biotin-labeled oligonucleotides bound to streptavidin magnetic beads (90 min, 4 °C) (Dynabeads, Invitrogen). Biotin-labeled Chk1 and β-actin promoter regions were obtained by amplifying genomic DNA using the primer pairs indicated in Supplemental Table S1. Following incubation, beads were washed repeatedly with lysis buffer and finally, oligoprecipitated proteins were eluted by boiling the beads in Laemmli buffer (50 mm TrisHCl pH 6.8, 5% glycerol, 1.67% β-mercaptoethanol, 1.67% SDS).

Protein Identification by Mass Spectrometry

Immunoprecipitated proteins were digested with trypsin following a standard in-solution digestion protocol (21). Liquid chromatography-tandem MS (LC-MS/MS) spectra were acquired using a Q-TOF micro mass spectrometer (Waters, Milford, MA) interfaced with a CapLC System (Waters) as previously described (20). Briefly, each sample was loaded onto a Symmetry 300 C18 NanoEase Trap precolumn (Waters) connected to a XBridge BEH130 C18, 75 μm × 150 mm, 3.5 μm (Waters). Peptides were eluted with a 30 min linear gradient of 5–60% acetonitrile directly onto a NanoEase Emitter (Waters). Data-dependent MS/MS acquisitions were performed on precursors with charge states of 2, 3, or 4 over a survey m/z range of 400–1500. Obtained spectra were processed using default processing parameters by VEMS (22) and searched using MASCOT version 2.4.0. (Matrixscience, London, UK) against SwissProt Human database (version 2012_07, 20232 sequences). For protein identification, the following parameters were adopted: carbamidomethylation of cysteines as fixed modification, oxidation of methionines as variable modification, 100 ppm of peptide mass tolerance, 0.2 Da fragment mass tolerance, and one missed cleavage was allowed. The cutoff score used to filter peptide identifications was the Mascot identity score. Automatically calculated FDR values by Mascot were below 4% in all the analysis.

The proteomics data have been deposited in the PRIDE partner repository Proteome Exchange (http://proteomecentral.proteomexchange.org) with the dataset identifier PXD000026.

Identified proteins were classified according to their peptide evidence by PAnalyzer software (23).

Immunoblotting and Immunofluorescence Analyses

For immunoblotting analysis, proteins were separated using SDS-PAGE and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The following antibodies were used: anti-E2F2 (sc-633), HA probe (sc-7392), and anti-ALY (sc-32311) from Santa Cruz and anti-GFP (3H9) from Chromotek. Immunocomplexes were visualized with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antimouse or antirabbit IgG antibodies (GE Healthcare), followed by chemiluminiscence detection (ECL, GE Healthcare) with a ChemiDoc camera (Bio-Rad).

Immunofluorescence analysis was carried out as previously described (24). Anti-E2F2 (Santa Cruz sc-633, diluted 1:500) and anti-ALY (Santa Cruz sc-32311, diluted 1:1000) were used as primary antibodies. Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated goat anti-rabbit or goat anti-mouse secondary antibodies (Invitrogen) were used. Slides were examined using a Zeiss Axioskop fluorescence microscope.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Assay

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay was performed as previously described (20). Briefly, mouse T cells stimulated with anti-CD3 were crosslinked using formaldehyde and lysed. Nuclei were collected and subjected to sonication to fragment the chromatin. Then, the chromatin was immunoprecipitated using anti-E2F2 (sc-633), anti-SV40T (sc-147), or anti-ALY (sc-32311) antibodies (SantaCruz Biotechnology Inc.). Finally, immunoprecipitated chromatin was analyzed by quantitative PCR using the primers detailed in supplemental Table S1.

Microarray Hybridization and Bioinformatic Analysis

Total RNA was extracted 48 h after transfection using TRIzol according to manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen). Cy3 and Cy5 labeled DNA pools were prepared and hybridized to the Human WHG 4 × 44K Agilent microarray containing 41,000 probes. Changes in gene expression were analyzed using one sample t test followed by Benjamini-Hochberg multiple testing correction, and were considered as significant when p < 0.02.

Ingenuity Pathways Analysis (IPA) software (Ingenuity Systems, www.ingenuity.com) was used to detect overrepresented “Molecular and Cellular Functions” within the set of deregulated genes.

Identification of overrepresented transcription factor binding sites (TFBS) was performed by analyzing proximal promoter regions and evolutionarily conserved distant regulatory elements using Pscan (25) and DiRE (26) software, respectively.

The localization of putative E2F motifs in gene promoters was carried out with MotifLocator in the TOUCAN program (27). The search was restricted to the proximal promoter region using “Human 1 Kb Proximal 1000 ENSMUSG (3)” as background, and considering a cutoff of 0.9.

RESULTS

Identification of potential E2F2-Interacting Proteins

To search for novel proteins that interact with the transcription factor E2F2, we followed the experimental approach shown in Fig. 1A. Whole protein extracts from HEK293T cells expressing HA-tagged E2F2 were subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) with an anti-HA antibody or, as a negative control (NegCt), with an anti-T antibody. Immunoprecipitated proteins were eluted, digested with trypsin, and the resulting peptides were analyzed by LC-MS/MS. The whole procedure was repeated several times in an attempt to gauge reproducibility (nine replicates of the anti-HA IP and six replicates of the control IP). Reassuringly, E2F2 was detected in all anti-HA immunoprecipitated samples, but it was not present in any of the control samples (data not shown).

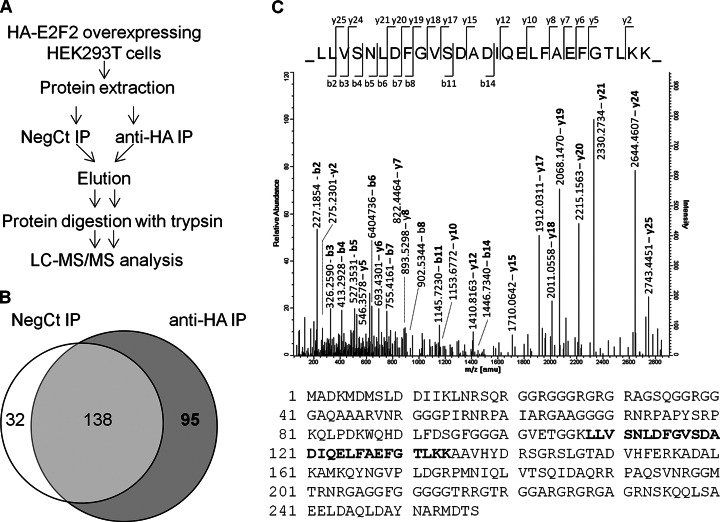

Fig. 1.

Identification of potential E2F2-interacting proteins. A, Experimental design followed to identify E2F2-binding partners. Proteins immunoprecipitated with anti-HA and the negative control anti-T antibody were eluted, digested with trypsin, and analyzed by LC-MS/MS. B, Venn diagram showing overlap in proteins identified in both immunoprecipitations. C, Annotated MS/MS spectra of the peptide LLVSNLDFGVSDADIQELFAEFGTLKK, which allowed the identification of ALY and peptide coverage of ALY; the peptide used for identification is highlighted in bold.

A total of 265 proteins were identified by LC-MS/MS analysis of the immunoprecipitated samples. All identifications are accessible in Proteome Exchange public repository (data set identifier PXD000026). Besides E2F2, 94 additional proteins were exclusively detected in the anti-HA immunoprecipitated samples (Fig. 1B), and may thus represent putative E2F2-interacting proteins (supplemental Table S2).

To narrow down our search for novel E2F2-binding partners, we only considered proteins that were identified in at least two independent replicates of the anti-HA IP. Our final list of E2F2-interacting protein candidates included 20 conclusive proteins (proteins identified by unique peptides) and six indistinguishable proteins (proteins that share all identified peptides), which were further classified into 2 groups by PAnalyzer software (Table I).

Table I. Putative E2F2-interacting proteins identified by LC-MS/MS. Uniprot Accession number, Entry name, a brief description, and the subcellular localization of each protein as well as if they are involved in gene expression regulation is indicated. Mascot score, number of identified peptides and sequence coverage shown correspond to the best identification.

| Accesion number | Entry name | Description | Subcellular localizationa | Gene expression regulationa | Mascot score | Peptides | Seq Cov % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conclusive proteins | P05141 | ADT2_HUMAN | ADP/ATP translocase 2 | Mitochondrion inner membrane | 51 | 1 | 9 | |

| P08758 | ANXA5_HUMAN | Annexin A5 | Cytoplasm | 108 | 2 | 9 | ||

| P25705 | ATPA_HUMAN | ATP synthase subunit alpha, mitochondrial | Cell membrane | 76 | 1 | 3 | ||

| Q00610 | CLH1_HUMAN | Clathrin heavy chain 1 | Cytoplasmic vesicle membrane | 137 | 3 | 2 | ||

| Q05639 | EIF3B_HUMAN | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 subunit B | Cytosol | 178 | 4 | 14 | ||

| Q96IT0 | FAS_HUMAN | Fatty acid synthase | Cytoplasm | 238 | 5 | 3 | ||

| P31943 | HNRH1_HUMAN | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein H | Nucleoplasm | 43 | 1 | 3 | ||

| Q14240 | IF4A2_HUMAN | Eukaryotic initiation factor 4A-II | Cytosol | 79 | 1 | 3 | ||

| Q14974 | IMB1_HUMAN | Importin subunit beta-1 | Cytosol; Nuclear membrane; Nucleoplasm | 56 | 2 | 6 | ||

| P12268 | IMDH2_HUMAN | Inosine-5′-monophosphate dehydrogenase 2 | Cytosol; Nucleus | 64 | 1 | 8 | ||

| Q15233 | NONO_HUMAN | Non-POU domain-containing octamer-binding protein | Nucleus | Yes | 88 | 2 | 7 | |

| Q9UNM6 | PSD13_HUMAN | 26S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit 13 | Cytosol; Nucleoplasm | 75 | 1 | 3 | ||

| P62906 | RL10A_HUMAN | 60S ribosomal protein L10a | Cytosol | 79 | 1 | 1 | ||

| P35268 | RL22_HUMAN | 60S ribosomal protein L22 | Cytosol | 47 | 1 | 10 | ||

| P47914 | RL29_HUMAN | 60S ribosomal protein L29 | Cytosol | 49 | 1 | 9 | ||

| Q99729 | ROAA_HUMAN | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A/B | Nucleus; Cytoplasm | Yes | 46 | 2 | 6 | |

| P09661 | RU2A_HUMAN | U2 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein A' | Nucleus | Yes | 77 | 1 | 13 | |

| Q01130 | SRSF2_HUMAN | Serine/arginine-rich splicing factor 2 | Nucleus; nucleoplasm; Nucleus speckle | Yes | 53 | 1 | 7 | |

| Q9H853 | TB4AB_HUMAN | Putative tubulin-like protein alpha-4B | Cytoplasm | 93 | 2 | 10 | ||

| Q86V81 | THOC4_HUMAN | THO complex subunit 4 | Nucleus; Nucleus speckle; Cytoplasm | Yes | 80 | 1 | 10 | |

| Indistinguishalbe proteins | P62736 | ACTA_HUMAN | Actin, aortic smooth muscle | Cytoplasm; cytoskeleton | 215 | 4 | 14 | |

| P68032 | ACTC_HUMAN | Actin, alpha cardiac muscle 1 | ||||||

| P63267 | ACTH_HUMAN | Actin, gamma-enteric smooth muscle | ||||||

| P68133 | ACTS_HUMAN | Actin, alpha skeletal muscle | ||||||

| Q8NHW5 | RLA0L_HUMAN | 60S acidic ribosomal protein P0-like | Cytosol | 52 | 1 | 7 | ||

| P05388 | RLA0_HUMAN | 60S acidic ribosomal protein P0 |

a Information on subcellular localization and involvement in gene expression regulation was obtained from Uniprot.

Because E2F2 is predominantly a nuclear protein, we reasoned that physiologically relevant interactions with other proteins are more likely to occur in the nucleus. Therefore, the subcellular localization of the putative E2F2-binding proteins listed in Table I was checked in the Uniprot database. Ten proteins have been previously reported to localize in the nucleus. Interestingly, four of them are known to play a role in the regulation of gene expression. These included THOC4, also termed ALY. ALY was automatically identified by the Mascot search engine in two out of the nine anti-HA immunoprecipitations. The MS/MS spectrum of the peptide used to identify ALY in one of the replicates is shown in Fig. 1C. Further manual examination of the MS spectra revealed the presence of an ALY precursor ion in three additional anti-HA replicates (supplemental Fig. S1), whereas it was absent from all control immunoprecipitations.

ALY was originally discovered for its role as a transcriptional co-activator (28). More recently, ALY and its yeast homolog Yra1 have been reported to be involved in cell cycle regulation (29–30). Taking into account its reproducible binding to HA-E2F2, its nuclear localization, and its known biological roles, we considered ALY an interesting candidate, and therefore its interaction with E2F2 was further analyzed.

Validation and Characterization of ALY/E2F2 Interaction

The interaction between ALY and E2F2 was validated by coimmunoprecipitation followed by immunoblot analysis. As shown in Fig. 2A, ALY was readily detected in anti-HA immunoprecipitated samples from HA-E2F2 expressing HEK293T cells. As a control, ALY was not detected in samples immunoprecipitated with an anti-T antibody or in immunoprecipitates from nontransfected HEK293T cells, which do not express endogenous E2F2.

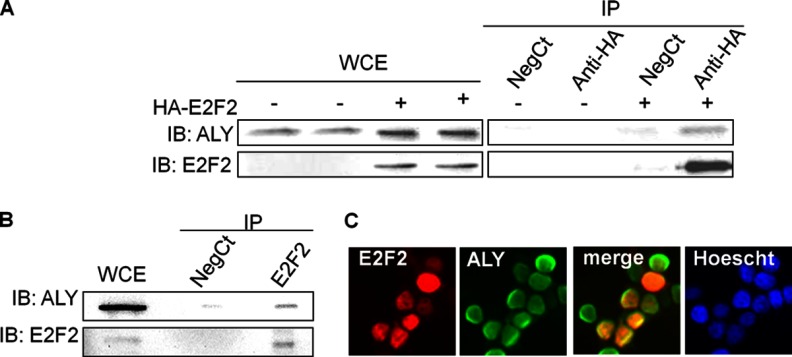

Fig. 2.

Validation of ALY/E2F2 interaction. A, HEK293T cells with and without HA-E2F2 transfection were immunoprecipitated using anti-HA and anti-T antibodies; the presence of E2F2 and ALY in the immunocomplexes was visualized by immunoblot. B, Endogenous E2F2 was immunoprecipitated from CD3-stimulated mouse T cells and coprecipitation of ALY was detected by immunoblot. C, E2F2 and ALY colocalize in the nucleus of HEK293T cells.

To test the interaction between ALY and E2F2 in a more physiological setting, co-immunoprecipitation assays were carried out in mouse lymph node-derived T-cells that were incubated for 36 h with anti-CD3 antibody to promote expression of endogenous E2F2 (18). Proteins were extracted and immunoprecipitated with either anti-E2F2 or anti-T antibodies, and precipitated protein complexes were analyzed by immunoblotting. As shown in Fig. 2B, ALY co-immunoprecipitated with endogenous E2F2 in these cells. Altogether, these data show that both ectopically expressed as well as endogenous E2F2 can interact with ALY, thus validating the results of the LC-MS/MS analysis. In line with these results, immunofluorescence analysis showed that HA-E2F2 and ALY colocalize in the nucleus of transfected HEK293T cells (Fig. 2C).

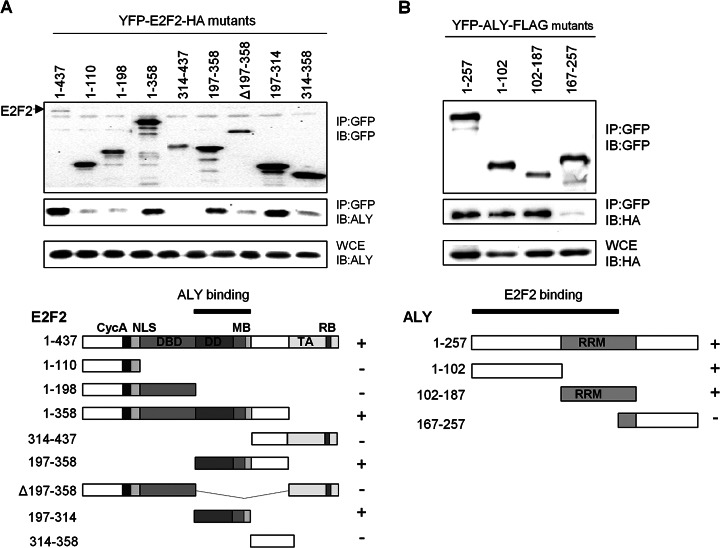

To further characterize ALY/E2F2 interaction, we aimed to map the regions on ALY and E2F2 involved in complex formation. To this end, we generated a panel of E2F2 and ALY deletion mutants tagged with YFP and lacking various functional domains (Figs. 3A, 3B). To determine the ALY binding site in E2F2, YFP-E2F2-HA deletion mutants were cotransfected with ALY into HEK293T cells. Cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with GFP-trap-M system, and the ability of ALY to co-immunoprecipitate with the different E2F2 deletion mutants was determined by immunoblot using an anti-ALY antibody. The results showed that the segment comprising residues 197–314, which includes the dimerization and marked box of E2F2, is responsible for associating with ALY (Fig. 3A). Similarly, to map the E2F2 binding domain in ALY, YFP-tagged ALY deletion mutants were cotransfected with E2F2 into HEK293T cells. ALY was immunoprecipitated and coprecipitation of E2F2 was detected by immunoblot. The results showed that the N-terminal region (amino acids 1–102) and the central region of ALY (amino acids 102–187), which includes its RNA recognition motif, are sufficient to interact with E2F2 (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Mapping ALY/E2F2 interaction domains. A, Mapping ALY-binding site in E2F2. HEK293T cells were cotransfected with plasmids expressing ALY and YFP-HA-tagged E2F2 deletion mutants, lysed and immunoprecipitated with GFP-trap-M system. Immunocomplexes were separated by SDS-PAGE, blotted and probed with the indicated antibodies. The arrowhead indicates full length E2F2. Below, a schematic representation of E2F2 deletion mutants and a summary of the results are shown. The following domains of E2F2 are indicated: CycA, cyclinA binding domain; NLS, nuclear localization signal; DBD, DNA binding domain; DD, Dimerization domain; MB, marked box; TA, transactivation domain; RB, RB-binding domain. B, Mapping E2F2 binding site in ALY. YFP-tagged ALY mutants were cotransfected with HA-E2F2. Coprecipitation of E2F2 with the ALY mutants was determined by ALY IP followed by anti-HA immunoblot. A schematic representation of ALY deletion mutants and a summary of the results are shown below. RRM indicates the RNA recognition motif.

Binding of the ALY/E2F2 Complex to E2F Target Genes

E2F2 carries out its transcriptional regulatory function by binding to specific gene promoter regions through its well-characterized DNA binding domain. Interestingly, our data indicate that the ALY-interacting motif of E2F2 does not overlap with its DNA binding domain, suggesting that E2F2 could simultaneously bind to DNA and ALY. Because no DNA binding domains have yet been identified in ALY, we hypothesized that E2F2 might mediate the binding of an ALY/E2F2 complex to the promoter regions of E2F target genes.

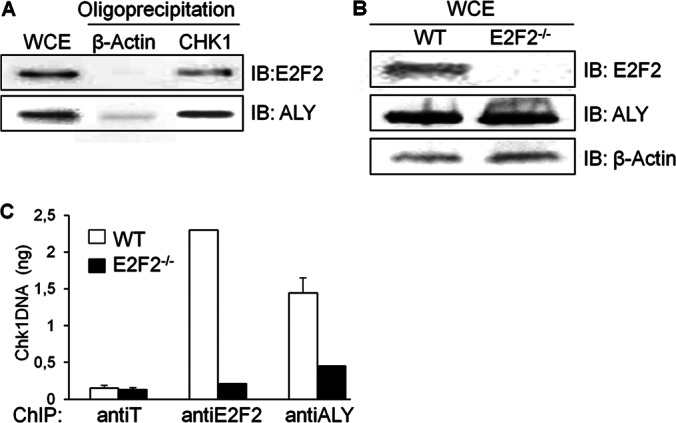

To test this hypothesis, we first carried out an oligoprecipitation assay using protein extracted from HEK293T cells expressing HA-E2F2. Double-stranded DNA sequences corresponding to the promoter regions of CHK1 or β-actin genes were used as bait. CHK1 is a well-known E2F target gene, and its promoter bears several E2F binding sites (31). On the contrary, the promoter region of β-actin gene lacks E2F consensus site and was therefore included in the assay as a negative control. Consistent with previously published data (18), E2F2 was found to bind to the CHK1 promoter, but not to the β-actin promoter (Fig. 4A). Similarly to E2F2, ALY was readily detected in the CHK1 promoter oligoprecipitated sample, although, in this case, a minor signal was also noted in the β-actin promoter oligoprecipitate. These results suggest that E2F2 might contribute to the efficient recruitment of ALY to the CHK1 promoter.

Fig. 4.

Binding of the ALY/E2F2 complex to E2F target genes. A, HEK293T cell lysates were oligoprecipitated using CHK1 or β-actin promoter regions; the presence of E2F2 and ALY in the oligoprecipitated complexes was visualized by immunoblot. B, Expression levels of E2F2 and ALY in CD3-stimulated WT and E2F2−/− mouse T cells were analyzed by immunoblot. Detection of β-actin was used as loading control. C, Cell lysates form WT or E2F2−/− T lymphocytes stimulated with anti-CD3 were subjected to ChIP using antibodies against E2F2 and ALY. Anti-T ChIPs served as negative control. Precipitated DNA was analyzed by quantitative PCR using primers located near the E2F sites in Chk1 promoter.

To further test this possibility, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) followed by quantitative PCR (ChIP-qPCR) analyses in lymph node-derived T cells obtained from wild type (WT) and E2F2-null (E2F2−/−) mice, which were confirmed by immunoblot to express similar levels of endogenous ALY (Fig. 4B). As expected, a negative control antibody (anti-T) was unable to immunoprecipitate Chk1 promoter DNA, whereas anti-E2F2 antibody was able to immunoprecipitate this promoter DNA in wild type but not in E2F2−/− T-cells. Remarkably, although the protein levels of ALY are similar in both cell types, the amount of Chk1 promoter immunoprecipitated with the anti-ALY antibody was significantly lower in E2F2−/− cells (Fig. 4C), suggesting that binding of ALY to the Chk1 promoter is considerably hampered in the absence of E2F2. Altogether, these data are consistent with a model in which E2F2 mediates the recruitment of an ALY/E2F2 complex to the promoter of E2F target genes.

Modulation of E2F2-dependent Transcriptional Activity by ALY

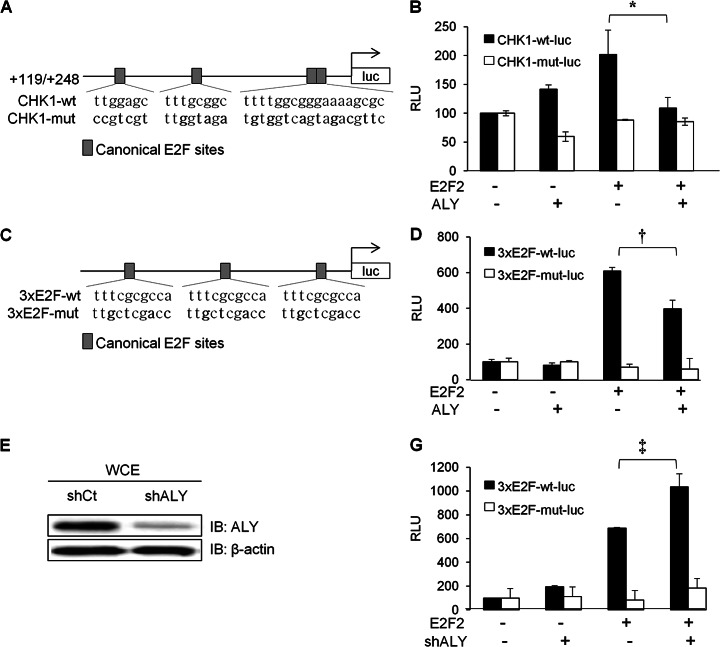

Our data suggesting that an ALY/E2F2 complex can bind to the promoter of Chk1 raised the possibility that ALY could modulate the capacity of E2F2 to regulate the transcription of its target genes. To test this hypothesis, we used luciferase assays in HEK293T cells to examine the effect of the ALY/E2F2 complex on the transcriptional regulation of human CHK1. The +119/+248 bp region of CHK1 promoter, harboring four E2F consensus sites (Fig. 5A), was cloned in a luciferase reporter vector to generate the CHK1-wt-luc plasmid. A CHK1-mut-luc plasmid, with mutated E2F sites, was also generated as a control. As shown in Fig. 5B, expression of E2F2 induced the luciferase activity of the CHK1-wt-luc reporter plasmid. Remarkably, this E2F2-mediated induction was significantly reduced by ALY co-expression. No significant change in luciferase expression was observed with the CHK1-mut-luc reporter control under any of the experimental conditions. These results suggest that ALY could negatively modulate the activity of E2F2.

Fig. 5.

Modulation of E2F2-dependent transcriptional activity by ALY. A, Schematic representation of the CHK1-wt-luc and CHK1-mut-luc vectors, which has four intact or mutated consensus E2F motifs, respectively. Mutated nucleotides are indicated in bold. B, Wild type and mutated version of CHK1-luc reporter vectors were cotransfected with the indicated expression vectors and transcription activation was determined by luciferase assay. C, 3xE2F-wt-luc and 3x-E2F-mut-luc vectors containing three intact or mutated consecutive canonical E2F sites are represented. Mutated nucleotides are indicated in bold. E, Immunoblot analysis shows that shALY efficiently silences endogenous ALY. shCt vector containing the scramble sequence of shALY served as negative control. D, G, E2F luciferase reporter plasmid (3xE2F-wt-luc) and its mutated version (3xE2F-mut-luc) were cotransfected with the indicated expression or silencing vectors. Transcriptional activation was determined by luciferase assay. RLU, relative luciferase activity. Two-tailed student t test analysis * p < 0.05; † p < 0.005; ‡ p < 0.001.

To further evaluate the functional interaction between E2F2 and ALY, we carried out luciferase reporter assays with a widely used synthetic promoter containing three consensus E2F motifs (3x-E2F-wt) and its mutant counterpart (3x-E2F-mut) (32) (Fig. 5C). As expected, the 3xE2F-wt was strongly induced by E2F2 overexpression (Fig. 5D) and, consistent with the results obtained with CHK1 promoter, E2F2-mediated induction was significantly attenuated by ALY co-expression. Conversely, when E2F2 was co-expressed with a shRNA plasmid that efficiently down-regulates endogenous ALY (Fig. 5E), E2F2-mediated activation of 3xE2F-wt promoter was significantly enhanced (Fig. 5G). No significant change was observed under any of the experimental conditions when using the 3x-E2F-mut control reporter. Altogether, these results strongly suggest that ALY can negatively modulate E2F2-mediated transcriptional activation, revealing a functional interaction between these proteins that requires intact canonical E2F sites.

Global Analysis of Gene Expression Regulation by ALY

We next aimed to identify the full range of E2F2-responsive genes whose expression can be modulated by ALY. To this end, we used microarray analysis to compare the transcriptome of HEK293T cells co-expressing E2F2 and ALY (“ALYup”) with the transcriptome of cells where E2F2 was overexpressed but ALY was silenced (“ALYdown”). A total of four hybridization experiments corresponding to four transfections per condition were performed. The mRNA levels of 412 genes (supplemental Table S3) were significantly altered (p < 0.02) on differential expression of ALY (ratio ALYup/ALYdown), suggesting that ALY may contribute to modulate their transcription.

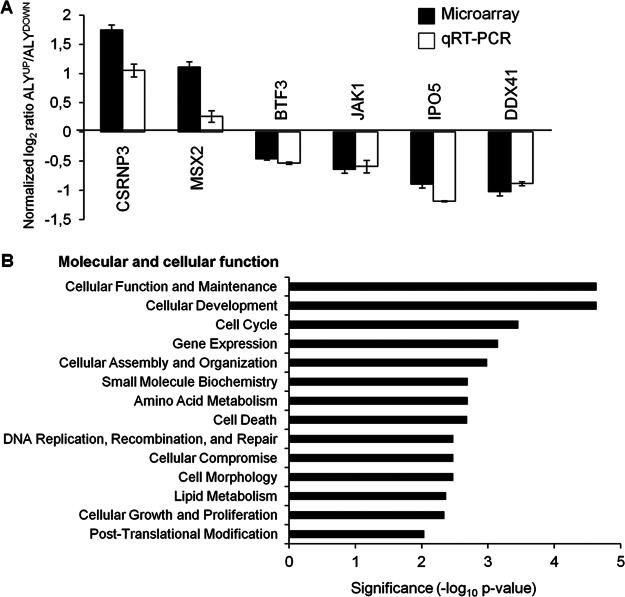

To validate the microarray results, we used qRT-PCR to quantify the mRNA levels of a set of six randomly selected genes that were found to be up- (CSRNP3, MSX2) or down-regulated (BTF3, DDX41, JAK1, and IPO5). As shown in Fig. 6A, a close correlation between the microarray and qRT-PCR data was observed for all the genes tested, thus validating the results obtained in the microarray.

Fig. 6.

Validation and classification of genes regulated by ALY. A, The altered expression of six genes detected in the microarray analysis was confirmed by qRT-PCR. Results were normalized against the expression level of CTF3C5. B, The set of genes significantly modulated by ALY (p < 0.02) was compared with all the genes present in the array to detect overrepresented biological categories related to the catalog Molecular and Cellular Function. The most significant (p < 0.01) terms including at least five genes are indicated.

According to IPA software analysis, the 412 genes putatively regulated by ALY are involved in a large variety of molecular and cellular functions (Fig. 6B). The most significantly enriched terms were “Cellular function and maintenance,” “Cellular development,” and “Cell cycle,” but overrepresented terms also included disparate functions related to cell death, cell organization and morphology, and biomolecule metabolism. These results reinforce the view that ALY plays a key role as a regulator of gene expression, and reveal the wide spectrum of biological processes that can be modulated by ALY.

Modulation of E2F Target Genes by ALY

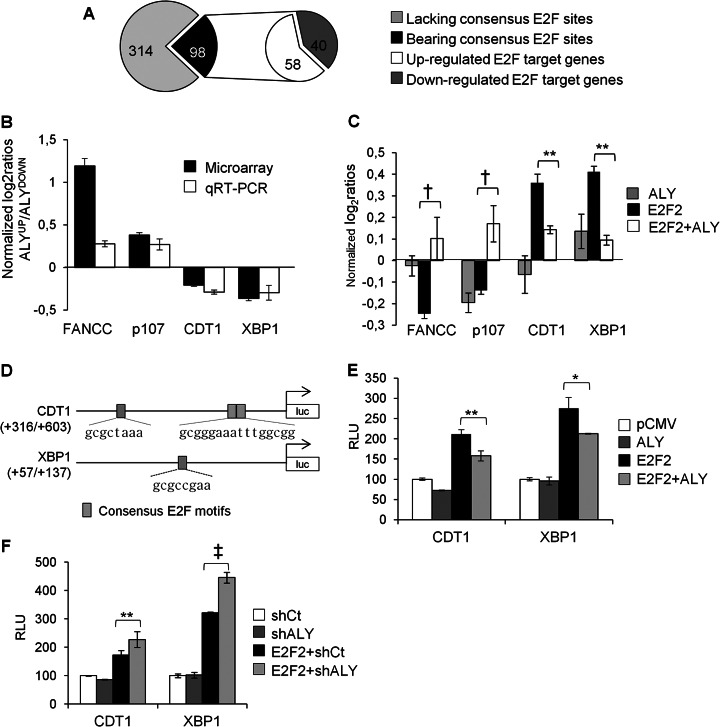

Proximal promoter regions (-450, +50 bp), and evolutionarily conserved distant regulatory elements of the 412 differentially expressed genes were analyzed using Pscan and DiRE software tools, to search for the enrichment of transcription factor binding sites (TFBS). These analyses revealed that E2F motifs were the most overrepresented TFBSs in the set of genes modulated by ALY (supplemental Tables S4A and S4B). Using the MotifLocator application of the program TOUCAN (27), we examined the proximal promoter region of each gene searching for consensus E2F motifs. This analysis identified 98 genes containing at least one canonical E2F motif in their proximal promoter region (Fig. 7A). 58 of these genes were up-regulated whereas 40 were down-regulated in the “ALYup” microarray setting. These included known E2F target genes, such as FANCC and p107 (up-regulated) or CDT1 (down-regulated), but also previously not reported E2F-responsive genes such as XBP1 (down-regulated), whose differential expression was confirmed by qRT-PCR analysis in an independent biological replicate (Fig. 7B).

Fig. 7.

Modulation of E2F target genes by ALY. A, The chart indicates the number of genes containing E2F motifs found in the microarray analysis to be either up-regulated or down-regulated in response to ALY. B, Deregulation of 4 E2F target genes (FANCC, p107, CDT1 and XBP1) was confirmed by qRT-PCR. Results were normalized against the expression levels of CTF3C5. C, The individual and combined effect of E2F2 and ALY in the regulation of four E2F target genes was analyzed by qRT-PCR. D, Schematic representation of the promoter regions of CDT1 and XBP1 cloned in the luciferase reporter vector. The relative position and the sequence of canonical E2F sites are indicated. E, F, Luciferase reporter vectors were cotransfected with the indicated expression or silencing vectors and transcriptional activity was determined by luciferase assay. RLU, relative luciferase activity. Two-tailed studet t test analysis * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, † p < 0.005, ‡ p < 0.001

Further qRT-PCR analysis (Fig. 7C) revealed that CDT1 and XBP1 were activated by E2F2 and negatively regulated by ALY, supporting our view that ALY is a negative modulator of E2F2-mediated transcriptional activation.

To assess the relevance of E2F consensus sites on ALY/E2F2-mediated regulation of CDT1 and XBP1, small promoter regions of these genes encompassing E2F motifs (Fig. 7D), were cloned into luciferase reporter vectors. In line with the qRT-PCR data shown above, overexpression of E2F2 strongly induced the luciferase activity driven by CDT1 and XBP1 promoters (Fig. 7E). Overexpression of ALY by itself had no effect, but significantly attenuated E2F2-mediated activation. Conversely, silencing of ALY resulted in a more pronounced activation of the luciferase activity driven by E2F2 (Fig. 7F). These results provide further evidence that the ALY/E2F2 complex modulates the expression of E2F target genes through canonical E2F sites.

DISCUSSION

E2F2 plays a key role in the regulation of essential cellular processes such as cell cycle and differentiation (33–34). The molecular mechanisms underlying E2F2 activity remain to be elucidated, and little is known, in particular, on E2F2-interacting proteins that might contribute to fine-tune the activity of this transcription factor. Here, following a nontargeted MS-based proteomic approach and using HA-tagged E2F2 as bait, we have identified the nuclear protein ALY as a novel E2F2-interacting partner. We show that ALY is recruited to E2F target genes in the presence of E2F2, and that it functions as a negative regulator of E2F2 activity.

A number of studies have reported on the ability of ALY to act as a transcriptional co-activator for several transcription factors. In fact, ALY was originally proposed to play an essential role in the activation of the T-cell receptor α (TCRα) gene enhancer by interacting with AML-1 and LEF-1 transcription factors (28). Subsequent work also demonstrated that ALY can associate with RUNX1 (AML-1) and c-Myb to trigger the activation of TBLV enhancer (35). Our results further consolidate the role of ALY as key transcriptional modulator. Importantly, our data demonstrate that, in addition to its co-activator role, ALY can also function as a negative regulator of gene expression.

Although the potential of ALY to modulate gene expression was first described in the 90s, few genes are still known to be regulated by ALY. Our expression microarray analysis identified hundreds of genes, several of them E2F-responsive genes, whose transcription can be modulated by ALY. These include genes involved in key biological processes, such as amino acid and lipid metabolism or cell assembly and organization. Thus, besides the known roles of ALY in mRNA biogenesis and cell cycle regulation (29, 36), the functional diversity of ALY-modulated genes suggests that the spectrum of biological activities in which ALY plays a role is much broader than previously described. We confirmed that five genes bearing canonical E2F sites in their proximal promoter region, CHK1, CDT1, XBP1, FANCC, and p107, showed significant ALY-dependent up- or down-regulation. The observation that E2F target genes can be either up- or down-regulated in response to ALY suggests that the promoter context of each gene may have an influence on the outcome of ALY/E2F2-dependent regulation.

We show that ALY interacts with the central region of E2F2 (amino acids 197–314), a region encompassing two pivotal E2F domains involved in protein-protein interaction: the dimerization domain and the marked box. DP family members heterodimerize with E2F transcription factors through the dimerization domain enhancing binding to E2F DNA-binding sites and promoting activation of E2F-responsive genes (37). Thus, we cannot discard that ALY and DP proteins compete for binding to E2Fs and the inhibition of E2F activity by ALY is caused by the disruption of the classical E2F/DP heterodimer. Additionally, the marked box of E2F factors is emerging as an important domain for protein-protein interactions. Several of these interactions may dictate E2F promoter specificity. For instance, marked box-interacting proteins TFE3 and RYBP facilitate E2F-mediated transcription of the DNA polymerase p68 subunit and the CDC6 genes, respectively (16, 38). However, our findings reveal that ALY, which associates with the region of E2F2 encompassing the marked box, negatively regulates E2F transcriptional activity.

Several mechanisms have been described by which E2F-interacting proteins can inhibit the activity of these transcription factors. The best studied mechanism involves the blockade of E2F transactivation domain by RB binding (39–40). Additionally, inhibition of E2F binding to DNA, as observed on interaction of E2F1 and Purα (41), is also known to negatively affect the activity of E2Fs. Our data suggests that the formation of a DNA-bound ALY/E2F2 complex, similar to the recently described p14ARF-E2F/partner-DNA super complex (42), is responsible for the inhibition of E2F2 activity. Binding of ALY/E2F2 complex to DNA is likely mediated by E2F2, because ALY lacks a DNA binding domain, and its recruitment to E2F target genes is severely impaired in the absence of E2F2.

Although our data demonstrate that the newly identified ALY/E2F2 complex is involved in the fine-tuned regulation of gene expression, it does not rule out additional roles for this complex. Apart from being a transcriptional coregulator, ALY is a ubiquitous protein that shuttles from the nucleus to the cytoplasm as part of the exon junction complex bound to mRNA (43). Together with the protein UAP56, which is also present in our set of E2F2-binding candidates (supplemental Table S2), and the heterotetrameric THO complex, ALY triggers the formation of a larger complex named TREX (transcription/export), a key regulator of mRNA processing and export in yeast and metazoans (44). Intriguingly, the THO complex subunit 1 (THOC1) is known to associate with RB, the best characterized E2F2-binding partner (45). THOC1 binds to the N-terminal region of RB, whereas E2F2 binds to its C-terminal end (46–47), suggesting that RB could simultaneously associate with both proteins. ALY could be recruited to this complex through its interaction with E2F2. Thus, TREX components could associate with the E2F/RB complex pointing to a novel potential role for the RB/E2F network in the regulation of RNA processing (48).

Summarizing, we have identified the nuclear protein ALY as a novel interacting partner that modulates the transcriptional activity of E2F2. We have shown that ALY associates with DNA-bound E2F2 inhibiting its transcriptional regulatory activity, and modulates the expression of a large number of E2F-responsive genes, underscoring the relevance of the ALY/E2F2 complex.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Zubiaga and Arizmendi laboratory members for helpful discussions and comments. We thank Jokin Mendiaraz for technical assistance and Jose L. Zugaza for providing critical comments.

Footnotes

* This work was supported by grants from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (SAF 2012–33551, SAF 2009–12037 and CSD 2007–00017 to AMZ), the Basque Government (E09–256, S-PE09UN56 and S-PE10UN82 to JMA), and the University of the Basque Country (UFI 11/20 to AMZ). DNA sequencing and microarray analysis were performed in the Sequencing and Genotyping Unit and the Gene Expression Unit of the Genomics Core Facility-SGIKER at the University of the Basque Country. MS analysis was performed in the Proteomics Core Facility-SGIKER (member of ProteoRed-ISCIII). SGIKER Core Facilities are supported by UPV/EHU, MCINN, GV/EJ, ERDF and ESF.NO is supported by a graduate fellowship from the UPV/EHU. MO and JM are recipients of the Spanish Ministry of Education, Culture and Sports fellowship and Basque Government fellowship for graduate studies, respectively.

This article contains supplemental Fig. S1 and Tables S1 to S4.

This article contains supplemental Fig. S1 and Tables S1 to S4.

1 The abbreviations used are:

- RB

- retinoblastoma

- ChIP

- Chromatin Immunoprecipitation

- IP

- Immunoprecipitation

- LC-MS/MS

- Liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry

- qRT-PCR

- quantitative reverse transcription PCR

- shRNA

- short hairpin RNA

- TFBS

- transcription factor binding site

- WCE

- whole cell extract

- YFP

- yellow fluorescence protein.

REFERENCES

- 1. DeGregori J., Johnson D. G. (2006) Distinct and overlapping roles for E2F family members in transcription, proliferation and apoptosis. Curr. Mol. Med. 6, 739–748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Trimarchi J. M., Lees J. A. (2002) Sibling rivalry in the E2F family. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3, 11–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dimova D. K., Dyson N. J. (2005) The E2F transcriptional network: old acquaintances with new faces. Oncogene 24, 2810–2826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chen H. Z., Tsai S. Y., Leone G. (2009) Emerging roles of E2Fs in cancer: an exit from cell cycle control. Nat. Rev. Cancer 9, 785–797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. van den Heuvel S., Dyson N. J. (2008) Conserved functions of the pRB and E2F families. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 713–724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nevins J. R. (2001) The Rb/E2F pathway and cancer. Hum. Mol. Genet. 10, 699–703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kusek J. C., Greene R. M., Nugent P., Pisano M. M. (2000) Expression of the E2F family of transcription factors during murine development. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 44, 267–277 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ivanova I. A., Vespa A., Dagnino L. (2007) A novel mechanism of E2F1 regulation via nucleocytoplasmic shuttling: determinants of nuclear import and export. Cell Cycle 6, 2186–2195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Verona R., Moberg K., Estes S., Starz M., Vernon J. P., Lees J. A. (1997) E2F activity is regulated by cell cycle-dependent changes in subcellular localization. Mol. Cell Biol. 17, 7268–7282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vandel L., Kouzarides T. (1999) Residues phosphorylated by TFIIH are required for E2F-1 degradation during S-phase. EMBO J. 18, 4280–4291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Martinez-Balbás M. A., Bauer U. M., Nielsen S. J., Brehm A., Kouzarides T. (2000) Regulation of E2F1 activity by acetylation. EMBO J. 19, 662–671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Marzio G., Wagener C., Gutierrez M. I., Cartwright P., Helin K., Giacca M. (2000) E2F family members are differentially regulated by reversible acetylation. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 10887–10892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hofmann F., Martelli F., Livingston D. M., Wang Z. (1996) The retinoblastoma gene product protects E2F-1 from degradation by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Genes Dev. 10, 2949–2959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Weinmann A. S., Yan P. S., Oberley M. J., Huang T. H., Farnham P. J. (2002) Isolating human transcription factor targets by coupling chromatin immunoprecipitation and CpG island microarray analysis. Genes Dev. 16, 235–244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mitxelena J., Osinalde N., Arizmendi J. M., Fullaondo A., Zubiaga A. M. (2012) Proteomic approaches to unraveling the RB/E2F Regulatory Pathway. Proteomics - Human Diseases and Protein Functions, Prof. Kwong Man Tsz. (Ed.), pp 135–160 [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schlisio S., Halperin T., Vidal M., Nevins J. R. (2002) Interaction of YY1 with E2Fs, mediated by RYBP, provides a mechanism for specificity of E2F function. EMBO J. 21, 5775–5786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Delgado I., Fresnedo O., Iglesias A., Rueda Y., Syn W. K., Zubiaga A. M., Ochoa B. (2011) A role for transcription factor E2F2 in hepatocyte proliferation and timely liver regeneration. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 301, G20–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Infante A., Laresgoiti U., Fernández-Rueda J., Fullaondo A., Galan J., Diaz-Uriarte R., Malumbres M., Field S. J., Zubiaga A. M. (2008) E2F2 represses cell cycle regulators to maintain quiescence. Cell Cycle 7, 3915–3927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Murga M., Fernández-Capetillo O., Field S. J., Moreno B., Borlado L. R., Fujiwara Y., Balomenos D., Vicario A., Carrera A. C., Orkin S. H., Greenberg M. E., Zubiaga A. M. (2001) Mutation of E2F2 in mice causes enhanced T lymphocyte proliferation, leading to the development of autoimmunity. Immunity 15, 959–970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Azkargorta M., Fullaondo A., Laresgoiti U., Aloria K., Infante A., Arizmendi J. M., Zubiaga A. M. (2010) Differential proteomics analysis reveals a role for E2F2 in the regulation of the Ahr pathway in T lymphocytes. Mol. Cell Proteomics 9, 2184–2194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Stone K., Williams K. (1996) Enzymatic digestion of proteins in solution and in SDS polyacrylamide gels in The Protein Protocols Handbook, Humana Press, Totowa, NJ [Google Scholar]

- 22. Matthiesen R., Trelle M. B., Højrup P., Bunkenborg J., Jensen O. N. (2005) VEMS 3.0: algorithms and computational tools for tandem mass spectrometry based identification of post-translational modifications in proteins. J. Proteome Res. 4, 2338–2347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Prieto G., Aloria K., Osinalde N., Fullaondo A., Arizmendi J. M., Matthiesen R. (2012) PAnalyzer: A software tool for protein inference in shotgun proteomics. BMC Bioinformatics 13, 288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rodríguez J. A., Henderson B. R. (2000) Identification of a functional nuclear export sequence in BRCA1. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 38589–38596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zambelli F., Pesole G., Pavesi G. (2009) Pscan: finding over-represented transcription factor binding site motifs in sequences from co-regulated or co-expressed genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, W247–252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gotea V., Ovcharenko I. (2008) DiRE: identifying distant regulatory elements of co-expressed genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, W133–139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Aerts S., Van Loo P., Thijs G., Mayer H., de Martin R., Moreau Y., De Moor B. (2005) TOUCAN 2: the all-inclusive open source workbench for regulatory sequence analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, W393–396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bruhn L., Munnerlyn A., Grosschedl R. (1997) ALY, a context-dependent coactivator of LEF-1 and AML-1, is required for TCRalpha enhancer function. Genes Dev. 11, 640–653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Okada M., Jang S. W., Ye K. (2008) Akt phosphorylation and nuclear phosphoinositide association mediate mRNA export and cell proliferation activities by ALY. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 8649–8654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Swaminathan S., Kile A. C., MacDonald E. M., Koepp D. M. (2007) Yra1 is required for S phase entry and affects Dia2 binding to replication origins. Mol. Cell Biol. 27, 4674–4684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Carrassa L., Broggini M., Vikhanskaya F., Damia G. (2003) Characterization of the 5′flanking region of the human Chk1 gene: identification of E2F1 functional sites. Cell Cycle 2, 604–609 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Krek W., Livingston D. M., Shirodkar S. (1993) Binding to DNA and the retinoblastoma gene product promoted by complex formation of different E2F family members. Science 262, 1557–1560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dirlam A., Spike B. T., Macleod K. F. (2007) Deregulated E2f-2 underlies cell cycle and maturation defects in retinoblastoma null erythroblasts. Mol. Cell Biol. 27, 8713–8728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Persengiev S. P., Li J., Poulin M. L., Kilpatrick D. L. (2001) E2F2 converts reversibly differentiated PC12 cells to an irreversible, neurotrophin-dependent state. Oncogene 20, 5124–5131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mertz J. A., Kobayashi R., Dudley J. P. (2007) ALY is a common coactivator of RUNX1 and c-Myb on the type B leukemogenic virus enhancer. J. Virol. 81, 3503–3513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhou Z., Luo M. J., Straesser K., Katahira J., Hurt E., Reed R. (2000) The protein Aly links pre-messenger-RNA splicing to nuclear export in metazoans. Nature 407, 401–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Helin K., Wu C. L., Fattaey A. R., Lees J. A., Dynlacht B. D., Ngwu C., Harlow E. (1993) Heterodimerization of the transcription factors E2F-1 and DP-1 leads to cooperative trans-activation. Genes Dev. 7, 1850–1861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Giangrande P. H., Hallstrom T. C., Tunyaplin C., Calame K., Nevins J. R. (2003) Identification of E-box factor TFE3 as a functional partner for the E2F3 transcription factor. Mol. Cell Biol. 23, 3707–3720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Flemington E. K., Speck S. H., Kaelin W. G., Jr. (1993) E2F-1-mediated transactivation is inhibited by complex formation with the retinoblastoma susceptibility gene product. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 6914–6918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hiebert S. W., Chellappan S. P., Horowitz J. M., Nevins J. R. (1992) The interaction of RB with E2F coincides with an inhibition of the transcriptional activity of E2F. Genes Dev. 6, 177–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Darbinian N., Gallia G. L., Kundu M., Shcherbik N., Tretiakova A., Giordano A., Khalili K. (1999) Association of Pur alpha and E2F-1 suppresses transcriptional activity of E2F-1. Oncogene 18, 6398–6402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zhang H. J., Li W. J., Gu Y. Y., Li S. Y., An G. S., Ni J. H., Jia H. T. (2010) p14ARF interacts with E2F factors to form p14ARF-E2F/partner-DNA complexes repressing E2F-dependent transcription. J. Cell Biochem. 109, 693–701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Schmidt U., Im K. B., Benzing C., Janjetovic S., Rippe K., Lichter P., Wachsmuth M. (2009) Assembly and mobility of exon-exon junction complexes in living cells. RNA 15, 862–876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Strässer K., Masuda S., Mason P., Pfannstiel J., Oppizzi M., Rodriguez-Navarro S., Rondon A. G., Aguilera A., Struhl K., Reed R., Hurt E. (2002) TREX is a conserved complex coupling transcription with messenger RNA export. Nature 417, 304–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Durfee T., Mancini M. A., Jones D., Elledge S. J., Lee W. H. (1994) The amino-terminal region of the retinoblastoma gene product binds a novel nuclear matrix protein that co-localizes to centers for RNA processing. J. Cell Biol. 127, 609–622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Chow K. N., Dean D. C. (1996) Domains A and B in the Rb pocket interact to form a transcriptional repressor motif. Mol. Cell Biol. 16, 4862–4868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Huang S., Shin E., Sheppard K. A., Chokroverty L., Shan B., Qian Y. W., Lee E. Y., Yee A. S. (1992) The retinoblastoma protein region required for interaction with the E2F transcription factor includes the T/E1A binding and carboxy-terminal sequences. DNA Cell Biol. 11, 539–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ahlander J., Bosco G. (2009) The RB/E2F pathway and regulation of RNA processing. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 384, 280–283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.