Background: The role of cannabinoid receptor type 2 (Cnr2) in regulating immune function had been widely investigated, but the mechanism is not fully understood.

Results: Cnr2 activation down-regulates 5-lipoxygenase (Alox5) expression by suppressing the JNK/c-Jun activation.

Conclusion: The Cnr2-JNK-Alox5 axis modulates leukocyte inflammatory migration.

Significance: Linking two important regulators in leukocyte inflammatory migration and providing a potential therapeutic strategy for treating human inflammation-associated diseases.

Keywords: Cell Migration, Chemical Biology, Immunology, Signal Transduction, Zebra Fish, CB2, Chemical Genetic Screen, Leukocyte Migration, Alox5

Abstract

Inflammatory migration of immune cells is involved in many human diseases. Identification of molecular pathways and modulators controlling inflammatory migration could lead to therapeutic strategies for treating human inflammation-associated diseases. The role of cannabinoid receptor type 2 (Cnr2) in regulating immune function had been widely investigated, but the mechanism is not fully understood. Through a chemical genetic screen using a zebrafish model for leukocyte migration, we found that both an agonist of the Cnr2 and inhibitor of the 5-lipoxygenase (Alox5, encoded by alox5) inhibit leukocyte migration in response to acute injury. These agents have a similar effect on migration of human myeloid cells. Consistent with these results, we found that inactivation of Cnr2 by zinc finger nuclease-mediated mutagenesis enhances leukocyte migration, while inactivation of Alox5 blocks leukocyte migration. Further investigation indicates that there is a signaling link between Cnr2 and Alox5 and that alox5 is a target of c-Jun. Cnr2 activation down-regulates alox5 expression by suppressing the JNK/c-Jun activation. These studies demonstrate that Cnr2, JNK, and Alox5 constitute a pathway regulating leukocyte migration. The cooperative effect between the Cnr2 agonist and Alox5 inhibitor also provides a potential therapeutic strategy for treating human inflammation-associated diseases.

Introduction

The activation and directional migration of innate immune cells in response to infection, trauma, toxin, lesion, or autoimmune injury is a classic process associated with inflammation. However, because it is a stressor of the tissue, inflammation must be tightly controlled. Abnormal migration and activation of innate immune cells can also be harmful and has been implicated widely in the progression of many human diseases, such as multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, atherosclerosis, and cancer (1–5). Therefore, systematic identification of molecular pathways that control innate immune cell migration and activation may provide new therapeutic strategies for treating human diseases associated with disordered inflammation.

Chemical genetics is a powerful technology for understanding genetic and biological functions. This approach uncovers unknown molecular pathways and gene functions involving certain biological process through a phenotype-based screen. Compared to forward genetics, chemical genetics is more conditional because of the flexible approach of chemical treatment. In addition this approach identifies lead compounds that serve as a foundation for drug discovery (6–8).

Zebrafish is a powerful vertebrate model for genetic study of development and diseases. Their small size, optical clarity, and substantial fecundity make zebrafish larva an ideal tool for an in vivo chemical genetic screen. Several chemical genetic screens have already been performed in zebrafish (9–16). These screens successfully identified new pathways involving in development or disease processes, as well as novel small molecules regulating biological processes.

We have previously established a transgenic zebrafish line, TG(zlyz:EGFP), for tracking the migration of zebrafish leukocytes in response to acute injury (17). In the early stage of TG(zlyz:EGFP) embryos before 36 h-post-fertilization (hpf),5 the EGFP-positive cells are primitive macrophages, while in the later stage after 48 hpf of embryos, the EGFP-positive cells include both monocytes/macrophages and neutrophils (17). Here we refer these EGFP-positive cells in the TG(zlyz:EGFP) embryos as leukocytes. Leukocyte, including neutrophil and monocyte/macrophage, is the most important part of the innate immune system (18). In tail-transected TG(zlyz:EGFP) zebrafish embryos at 72 hpf, the EGFP-positive leukocytes migrate to the wound. Within 6 h-post-tail-transection (hptt), the number of EGFP-positive leukocytes that aggregate in the wound reaches a maximum, about 45. Thus, the tail-transected TG(zlyz:EGFP) zebrafish provides us not only a visual and quantitative model of immune cell migration and inflammation, but also a useful tool for screening therapeutic compounds to treat human disorders associated with abnormal inflammation.

To identify chemical inhibitors of leukocyte migration, an in vivo chemical genetic screen was performed with tail-transected TG(zlyz:EGFP) zebrafish embryos. Seven out of 1,262 bioactive compounds with known targets from the GlaxoSmithKline LOPAC molecular library were identified to suppress the migration of zebrafish leukocytes to the wound after tail transection. Two of these, (R)-(+)-WIN55,212,–2 mesylate (WIN) and AA-861, are a cannabinoid receptor agonist and an Alox5 inhibitor, respectively.

WIN is a non-selective agonist for cannabinoid receptor type 1 (Cnr1) and cannabinoid receptor type 2(Cnr2). Cnr1 and Cnr2 are both G protein-coupled receptors with seven transmembrane α-helices. Cnr1 is highly expressed in the central nervous system and less in peripheral tissues (19), while Cnr2 is predominantly expressed in cells of hematopoietic origin in both mice and humans (20, 21). Previous studies of the human and mouse cannabinoid system have shown that Cnr2 modulates the inflammatory migration of immune cells through many pathways and participates in the progression of many important autoimmune diseases (22–31). To confirm our chemical genetic screening, we generated mutant alleles of zebrafish cnr2 (gene encoding Cnr2) and found that leukocyte migration is enhanced by the inactivation of Cnr2, further confirming that Cnr2 acts as a conserved negative inflammatory regulator in the vertebrate.

Alox5 also named 5-lipoxygenase, mainly expressed in leukocytes, is a key enzyme involved in the biosynthesis of leukotrienes, including LTB4. Accumulation of leukotrienes aggravates inflammation in many diseases, like atherosclerosis and asthma. LTB4, which is known as a potent chemoattractant, has been shown to induce activation and migration of leukocytes (32, 33). It has been shown that both alox5 knock-out and Alox5 inhibitor treatment lead to a decrease of in vivo leukocyte inflammatory migration of mice (34).

Recent studies showed that cannabidiol, a non-psychotropic cannabinoid, which has been reported to exert its effect through direct or indirect activation of Cnr2 (35–37), inhibits tumor cell growth by down-regulating Alox5 (38). Though the studies indicate a possible interaction between Cnr2 and Alox5, the mechanism is unknown. In studying the mechanism by which both WIN and AA-861 suppress zebrafish leukocyte migration, we found that there is a signaling link between Cnr2 and Alox5 and that alox5 is transcriptionally inhibited by Cnr2 activation through JNK/c-Jun inactivation. In addition, our in vivo screen results provide important information about the efficacy as well as the toxicity of the compounds identified, accelerating the development of new therapies for human disorders associated with deregulated leukocyte migration.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fish Care

Zebrafish maintenance, breeding, and staging were performed as standard methods. All studies were conducted after review by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Shanghai Institute of Hematology and in accordance with the GlaxoSmithKline Policy on the Care, Welfare, and Treatment of Laboratory Animals.

Tail Transection

Embryos were subject to tail transection with a sterile scalpel at the same anatomic site posterior to the end of tail circulation, resulting in consistent leukocyte recruitment with the number between 45 ± 5. The dynamic behavior and quantification of chemotactic migration were assessed by fluorescent steromicroscope (Zeiss Lumar V12 steromicroscope equipped with an AxioCam MRC5 digital camera and AxioVision Rel.4.5 software). All experiments were repeated three times with separate batches of embryos.

Chemicals

The LOPAC library from GSK (GlaxoSmithKline) containing 1,262 known bioactive compounds was used for the screen. The compounds for the follow-up experiments, JWH-015, were purchased from Tocris. SP600125 was purchased from Calbiochem. Dexamethasone (DEX) was purchased from Sigma.

Zinc Finger Nuclease (ZFN) Construction

The functional ZFNs for cnr2 were designed with ZiFiT software (zifit.partners.org/ZiFiT/) by the context-dependent assembly (CoDA) approach. And the zinc finger units were synthesized in Shanghai Biosune Biotechnology Co. Ltd.

Plasmid Construction

A MKK7-pcDNA plasmid and a JNK1-pcDNA plasmid were used as templates to amplify human MKK7 and JNK1 fragments by PCR with the following primers: (forward: 5′-GATATCGATATGGCGGCGTCCTC-3′), (reverse: 5′-GATCTAGAGCCTGAAGAAGGGC-3′), (forward: 5′-GCTCTAGAGAGCAGAAGCGTG-3′), (reverse: 5′-GATGCTGGCGGCCGCTGATCACTG-3′). The PCR product was cloned into a I-SceI-containing PBSK plasmid vector downstream of the zebrafish lyz promoter (zlyz). The plasmid lyz-MKK7-JNK1 was injected into TG(zlyz:GFP)+/+ embryos to express constitutively activate JNK phosphorylation in leukocytes.

Generation and Screening of Zebrafish cnr2 Mutant Lines

Capped ZFN-encoding RNAs specific for cnr2 were synthesized (mMESSAGE mMACHINE T7 Ultra kit, Ambion) and added a poly(A) tail (Poly(A) Tailing Kit, Ambion) as described previously (39). One-cell stage zebrafish embryos were injected with 50–100 pg of paired ZFN mRNAs. We grew adults from injected embryos and screened F1 fish by sequencing. Then the cnr2+/− embryos grew to adulthood and crossed with each other to identify cnr2−/− embryos from F2 progeny. Cnr2−/− embryos raised to adulthood and crossed to TG(zlyz:GFP)+/+ zebrafish to generate F3 cnr2+/− TG(zlyz:GFP)+/− zebrafish. Then cnr2+/− TG(zlyz:GFP)+/− raised to adulthood and crossed with each other. We screened cnr2 by sequencing and GFP expression in F4 embryos to identify cnr2−/− TG(zlyz:GFP)+/+ zebrafish. We used cnr2−/− TG(zlyz:GFP)+/+ zebrafish to produce enough cnr2−/− TG(zlyz:GFP)+/+ embryos for further experiments.

Morpholino Knockdown and Microinjection

Morpholino antisense oligonucleotides were purchased from Gene Tools. The sequences were as follows: alox5 morpholino: 5′-AACAGACACTGTGTACGTGAACATC-3′; alox5 5-mismatch control morpholino: 5′-AAgAcACACTcTGTACcTcAACATC-3′. Morpholinos were diluted to different concentrations with nuclease-free water, and 2 nl were microinjected into one-cell stage embryos. The concentrations of injected morpholino against alox5 were 1 mmol.

Flow Cytometry Analysis (FACS)

Embryos (72 hpf) were dissected in PBS with 10% FBS, and digested with 1× trypsin/EDTA for 30 min at 37 °C. Single cell suspension was obtained by centrifugation at 800 × g for 5 min. Cells were then washed twice with PBS/FBS, and passed through a 40-μm nylon mesh filter. Fluorescence-activated cell sorting was performed with MoFlo FACS (Dako Cytomation) to obtain a homogenous sample of EGFP-positive cells.

RNA Expression Measured by Real-time PCR

Real-time PCR was performed using SYBR Green (TOYOBO Engineering). The zebrafish housekeeping gene gapdh was used as an internal control. Primer sequences were: cnr1 (forward: 5′-CATGCAGTGAGGATGCTGAG-3′; reverse: 5′-CTTGGCCAGACGGATGTC-3′), cnr2 (forward: 5′-CACAGAACATTTCAACCACAGAT-3′; reverse: 5′-GGTCAGCAGGACCAAAATGT-3′), alox5 (forward: 5′-GAAGCATATTCAGAGGCAGCA-3′; reverse: 5′-AGTCCCAGCAAACACCTGAT-3′), gapdh (forward: 5′-CACCATCTTCCAGGAGCGAG-3′; reverse: 5′-TCACGCCACAGTTTCCCGGA-3′).

Western Blot

Embryos were deyolked as described previously (40). Embryos were homogenized in lysis buffer (20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 5 mm EDTA, 10% glycerol, and 0.1% Triton X-100) containing a protease inhibitor mixture. THP-1 cells were collected by centrifugation and lysed with lysis buffer (100 mm Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 4% SDS, 4% 2-mercaptoethanol, 2% glycerin, and 16% bromphenol blue). Protein lysates were separated via SDS-PAGE and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. The membranes were blocked in 5% w/v nonfat dry milk in TBST. Signals were detected by probing overnight at 4 °C with rabbit anti-GAPDH Ab (1/2000, Cell Signaling Technology), rabbit anti-phospho-JNK kinase Ab (1/500, Cell Signaling Technology), and rabbit anti-Alox5 Ab (1/750, Bioworld), followed by incubation with secondary HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit Abs (1/10,000) and ECL kit (Cell Signaling Technology).

Embryo-Chromatin Immunoprecipitation

Embryo-Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (E-ChIP) was performed as previously described with modifications (41). For each immunoprecipitation, about 50 tail-transected embryos were enzymatically dechorionated and then fixed in 1% formaldehyde in PBS for 10 min at 4 °C then 30 min at room temperature. 0.125 m of glycine was added to quench the formaldehyde, and the embryos were homogenized in swelling buffer (25 mm HEPES (pH 7.8), 1.5 mm MgCl2, 10 mm, KCl, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 1.0 mm DTT, and protease inhibitors), and incubated on ice for 30 min. After a light centrifugation, supernatant was discarded, and 100 μl of SDS lysis buffer (20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mm EDTA, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate, 150 mm NaCl, and protease inhibitor) was added. Sonication conditions were optimized to yield fragments of about 500 bp. Lysate was incubated with Protein A-Sepharose 4B with 50 μl per ml lysate (Amersham Biosciences) for 2 h at 4 °C, and then centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 2 min. The supernatant was incubated with 5 μg of the rabbit anti-phospho-c-Jun Ab with agitation at 4 °C overnight. 50 μl of protein A-Sepharose 4B per IP was added and incubated for 2 h with agitation at 4 °C. The beads were centrifuged and washed with wash buffer. Bound complexes were eluted from the beads at room temperature with vortexing for 10 min in 250 μl of elution buffer per IP. Crosslinks were reversed in 65 °C for 5 h and then digested by protease K at 50 °C for 2 h. DNA was purified by phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol. CR products were separated with a 1.2% agarose gel. Primer sequences were: alox5 AP-1 site I (forward: 5′-CTAGCAGCAAGTGTACGTGTC-3′; reverse: 5′-ACCGACTGAAAGGGAACTCCAG-3′); AP-1 site II (forward: 5′-CCACTGGTTTTGAAGTTGATACG-3′; reverse: 5′-GGCACAATTCATTGCATTCTAGG-3′); AP-1 site III (forward: 5′-GATCAGCAACCCTGCAACTC-3′; reverse: 5′-GCATTCATTTTGCATGCTTGG-3′).

Data Analysis and Statistics

Data are expressed as means ± S.E. When differences between two groups were compared, the Student's t-test was used.

RESULTS

Identification of Chemical Inhibitors of Leukocyte Migration in Response to Acute Injury

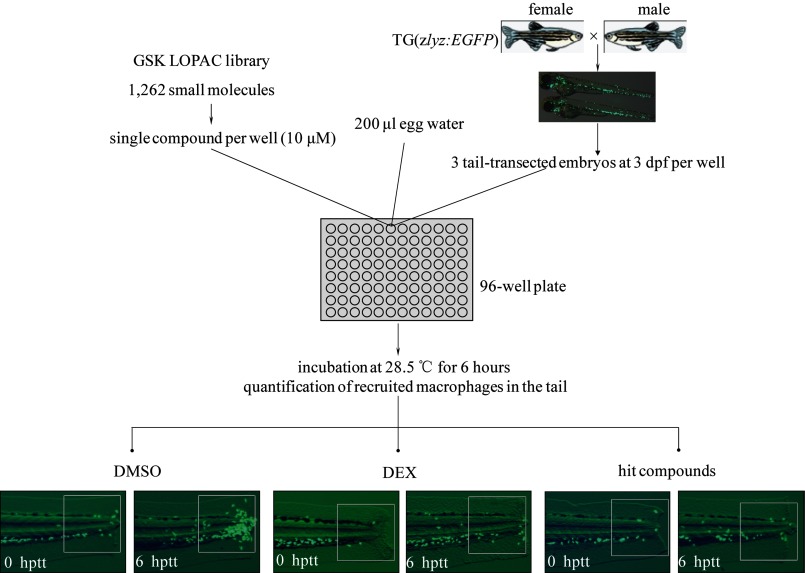

An in vivo chemical screen was performed to identify small molecules that inhibit the migration of leukocytes (Fig. 1). A total of 1,262 bioactive compounds were screened with tail-transected TG(zlyz:EGFP) zebrafish embryos. TG(zlyz:EGFP) zebrafish embryos were produced by breeding ten pairs of homozygous TG(zlyz:EGFP) zebrafish, which were enough for two 96-well plates each week. To induce an acute injury, the tails of zebrafish embryos were transected at the anatomic site posterior to the end of tail circulation. Immediately after the transection, three transgenic zebrafish embryos at 72 hpf were placed into each well and incubated with one of the library compounds at a concentration of 10 μm. Dexamethasone (DEX, 500 μm), which has been proven to inhibit leukocyte migration, was included as a positive control in each of the 96-well plates. Six hours after treatment, the EGFP-positive leukocytes congregated in the tail were quantified in each well, and then compared with those found in DMSO control and DEX control to assess the effect of the compounds in modulating leukocyte migration in response to acute injury.

FIGURE 1.

Screening for chemical suppressors of leukocyte inflammatory migration in zebrafish. Homozygous TG(zlyz:EGFP) fish were crossed twice a week to generate enough embryos for the screen. 3 tail-transected homozygous TG(zlyz:EGFP) embryos at 72 hpf were arrayed into each well of the 96-well plate. In each well, 200 μl of egg water was added containing one compound from the library at the concentration of 10 μm. A negative control of DMSO (2 μl per well)-treated embryos and a positive control of dexamethasone (DEX) (500 μm per well)-treated embryos were included in each plate. At 6 hptt at 28.5 °C, we observed EGFP-positive cells congregate in the tail and tried to identify suppressors that could inhibit leukocyte migration. The fluorescence photographs in embryo tails treated with hit compounds were taken to quantify the number of recruited leukocytes in the tail.

We initially identified fifteen compounds that inhibit the migration of leukocytes during the original screen and later confirmed seven of them in the following concentration gradient re-testing (supplemental Fig. S1, A and B). The seven compounds were further tested using an in vitro cell migration assay and each of them could efficiently block the chemotactic migration of THP-1, a human acute monocytic leukemia (AML) cell line, in a concentration-dependent manner (supplemental Fig. S2). The known targets of these compounds are shown in supplemental Table S1. Three of the seven hit compounds, forskolin, thapsigargin, and calcimycin, showed general toxicity in zebrafish embryos. Treatment with 3 μm calcimycin killed embryos in the dose-response re-tests, while the lethal concentrations of forskolin and thapsigargin were 10 μm (supplemental Fig. S1A). These results show the advantage of performing a chemical screen in a zebrafish model, which provides more information about the toxicity of these molecules and helps identify compounds with more drug development potential than a cell-based chemical screen (supplemental Fig. S1A).

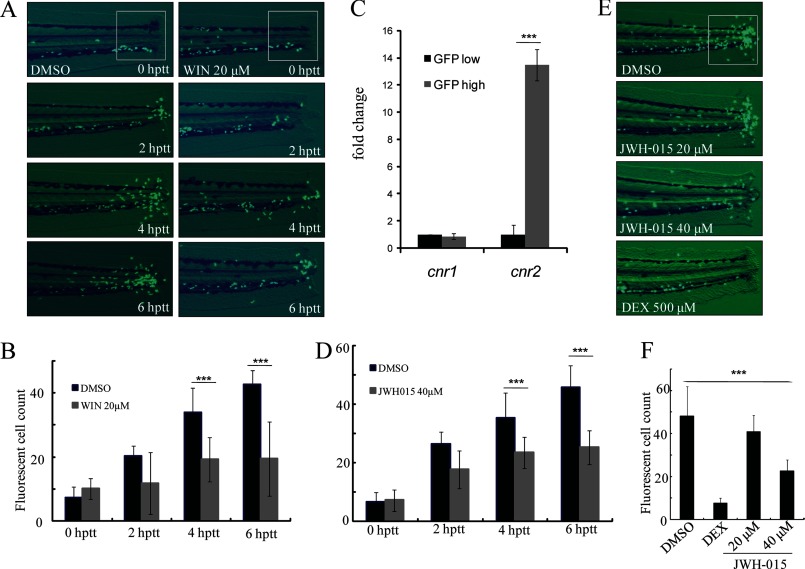

Cnr2 Signaling Negatively Regulates Leukocyte Migration

The treatment of WIN, the Cnr1 and Cnr2 agonist identified in our screen, could block zebrafish leukocyte migration in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 2, A and B). Cnr1 has been shown to be widely expressed in the zebrafish nervous system (19). Consistent with findings in mammals (20), we found that cnr2 is highly expressed in EGFP-positive zebrafish leukocytes whereas there was no difference in cnr1 expression between EGFP-negative and EGFP-positive cells (Fig. 2C). We reasoned that the inhibition of leukocyte inflammatory migration to the wound in tail-transected TG(zlyz:EGFP) zebrafish embryos by WIN was mediated by Cnr2, but not Cnr1. We went on to test whether the specific Cnr2 agonist JWH-015 was able to suppress the migration of zebrafish leukocytes (42). We found that, similar to WIN, JWH-015 could also efficiently block the migration of zebrafish leukocytes (Fig. 2, D--F). The activation of Cnr2 signaling by JWH-015 was also shown to effectively block the chemotactic migration of THP-1 cells induced by MCP-1 in vitro (supplemental Fig. S3C). In addition, compared with WIN, JWH-015 showed less toxicity on embryos.

FIGURE 2.

Modulating zebrafish leukocyte migration by Cnr2 agonists. A and B, congregated leukocytes in the tail of embryos treated with WIN were compared with those treated with the DMSO control at time-lapse of 0 hptt, 2 hptt, 4 hptt, and 6 hptt. ***, p < 0.005. n = 15. C, real-time-PCR of cnr1 and cnr2. The mRNA expression level of zebrafish cnr1 and cnr2 in purified EGFP-positive cell fold change to EGFP-negative cells of TG(zlyz:EGFP) embryos. ***, p < 0.005, n = 6. D, congregated EGFP-positive leukocytes in the tail of JWH-015-treated embryos were compared with those treated with the DMSO control in time-lapse (0 hptt, 2 hptt, 4 hptt, 6 hptt) and quantified. ***, p < 0.005. n = 15. E and F, leukocyte migration inhibitory effect of JWH-015 with concentration-lapse (20 μm, 40 μm) was compared with those of DMSO- or DEX-treated controls at 6 hptt, and the congregated EGFP-positive cells in the tail were quantified. ***, p < 0.005. n = 15.

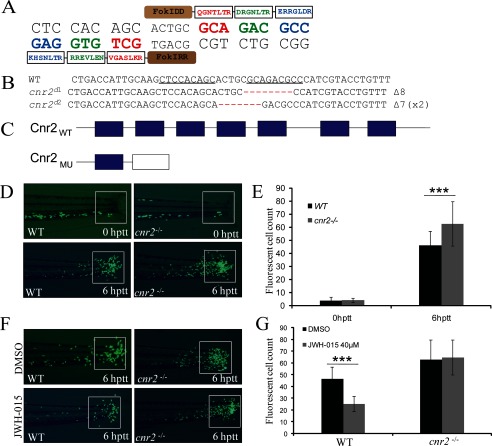

To further confirm the negative role of Cnr2 in regulating zebrafish leukocyte migration, we sought to generate heritable mutation of cnr2 in zebrafish using zinc finger nucleases engineered by the CoDA approach (39). Two potential CoDA ZFN target sites were identified in the exon 2 of cnr2 with the online ZiFiT program (supplemental Fig. S3A). CoDA ZFNs targeting one of the two CoDA sites (gCTCCACAGCactgcGCAGACGCCc) could efficiently induce a variety of deletions or insertions at the target site (Fig. 3A, supplemental Table S2 and data not shown). Embryos injected with mRNA encoding this pair of ZFNs were raised and screened for founders with the cnr2 mutation. Two different kinds of heritable deletion mutations in cnr2 were identified (Fig. 3B). The mutations caused frameshifts and premature termination codons, generating N-terminal-truncated Cnr2 with only one of the seven transmembrane-spanning domains (Fig. 3C).

FIGURE 3.

Generation of cnr2−/− mutant zebrafish line by the CoDA ZFN technique and the abnormal leukocyte inflammatory migration of cnr2−/− embryos. A, nucleotide sequence of the zebrafish cnr2 gene chosen for targeting and amino acid sequences of the zinc finger proteins selected to recognize this sequence. B, nucleotide sequence of zebrafish cnr2 mutants generated by CoDA-ZFN technique. The superscript d means deletion. C, schematic representation of WT Cnr2 and mutated Cnr2 protein. The frameshift of cnr2d1 leads to a truncation of the Cnr2 protein left with only one transmembrane-spanning domain. D and E, congregated GFP-positive leukocytes of cnr2−/− embryos compared with WT control at 0 hptt and 6 hptt and quantified. ***, p < 0.005. n = 40. F and G, leukocyte migration inhibitory effect of JWH-015 at 40 μm WT and cnr2−/− embryos at 6 hptt, and the congregated leukocytes in the tail were quantified. ***, p < 0.005. n = 20.

Inflammatory migration of leukocytes was observed within 6 hptt in cnr2−/− zebrafish embryos at 72 hpf. As expected when a negative regulator was inactivated, more leukocytes were recruited to the wound in cnr2−/− embryos, in contrast to embryos treated with JWH-015 (Fig. 2, E and F; Fig. 3, D and E). To identify whether the inhibitory effect of JWH-015 is through the activation of Cnr2, we went on to activate Cnr2 in WT and cnr2−/− embryos and found that the treatment of JWH-015 could not reverse the congregation of GFP-positive cells of cnr2−/− embryos (Fig. 3, F and G), which indicated that the increase of inflammatory migration is caused by the inactivation of Cnr2 in cnr2−/− embryos. Consistent with the effect of Cnr2 inactivation in zebrafish embryos, siRNA-mediated knockdown of Cnr2 in the THP-1 cell line also led to a significant increase of chemotactic migration in vitro (supplemental Fig. S3, B and C). Our results demonstrated that activation of Cnr2 signaling inhibits leukocyte migration while inhibition of Cnr2 signaling enhances recruitment of leukocytes in response to acute inflammation, implicating that Cnr2 serves as an important negative regulator in the leukocyte inflammatory migration response.

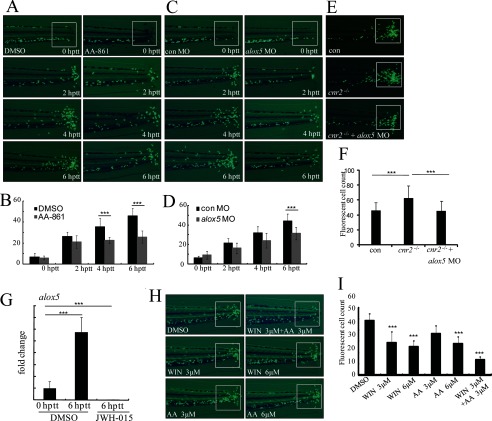

Regulation of Leukocyte Inflammatory Migration by Alox5

AA-861 (AA), a competitive inhibitor of Alox5 (43), was identified in our screen to efficiently inhibit leukocyte migration in zebrafish in a dose-dependent manner (supplemental Fig. S1A). Time-lapse fluorescence photographs taken within 6 hptt show a severe impairment of the recruitment of leukocytes to the wound in TG(zlyz:EGFP) zebrafish embryos treated with 20 μm AA-861 (Fig. 4, A and B). To confirm the effect of AA-861 in inhibiting leukocyte migration through Alox5 specifically, we used morpholino technology to knockdown alox5 in vivo and found that knocking down alox5 blocks migration of zebrafish leukocytes to the wound within 6 hptt (Fig. 4, C and D). To confirm the specificity of alox5 morpholino, we co-injected alox5 mRNA and alox5 morpholino and found that alox5 mRNA could revise the phenotype of alox5 morphants by a dose-dependent manner (supplemental Fig. S4). In addition, we found that alox5 mRNA is markedly up-regulated in EGFP-positive leukocytes from tail-transected TG(zlyz:EGFP) zebrafish embryos at 6 hptt (Fig. 4G). These data indicate that Alox5 is a responder to acute wound and that it positively regulates leukocyte migration.

FIGURE 4.

Regulation of zebrafish leukocyte migration by Alox5 and the interaction between Cnr2 and Alox5 pathways in regulation of leukocyte inflammatory migration. A and B, fluorescence images of AA-861-treated embryo tails in time course (0 hptt, 2 hptt, 4 hptt, and 6 hptt) treatment were compared with those with DMSO-treated controls and the congregated leukocytes were quantified. ***, p < 0.005. n = 15. C and D, congregated EGFP-positive cells in the tail of alox5 morphants at time lapse (0 hptt, 2 hptt, 4 hptt, and 6 hptt) were compared with those of 5-mismatch morphants and were quantified. ***, p < 0.005. n = 15. E and F, alox5 knockdown reduces the increase of congregated leukocytes in cnr2−/− embryos. Compared with control MO (5-mismatch morpholino)-injected embryos, more EGFP-positive leukocytes were recruited to the tail in cnr2−/− embryos, while the injection of alox5 morpholino significantly reduced the amount of leukocytes at the sites of injury of cnr2−/− embryos. The congregated GFP-positive leukocytes in the tail were quantified. ***, p < 0.005. n = 15. G, real-time-PCR indicated alox5 mRNA level fold change in EGFP-positive cells of transgenic embryos at 0 hptt and 6 hptt and JWH-015 treatment at 6 hptt. ***, p < 0.005. n = 6. H and I, WIN and AA-861(AA) showed a cooperative effect on the inhibition of leukocyte migration. When embryos were treated with WIN and AA combined at concentrations of 3 μm and 3 μm, there were fewer congregated EGFP-positive leukocytes than in embryos treated with either WIN or AA alone at the concentrations of 3 μm and 6 μm. The congregated leukocytes were quantified. ***, p < 0.005. n = 15.

Interaction between Cnr2 and Alox5 Pathways in Regulation of Leukocyte Inflammatory Migration

Because both Cnr2 agonist and Alox5 inhibitor can modulate leukocyte migration, we analyzed the potential interaction between the two pathways in our in vivo model of leukocyte inflammatory migration. We found that the increased recruitment of leukocytes to the tail wound of cnr2−/− embryos were almost completely rescued by blocking of the Alox5 pathway mediated with alox5 morpholino (Fig. 4, E and F). These data indicate that the Cnr2 signaling and the Alox5 pathway are connected and that Alox5 functions downstream of Cnr2. We also found that mRNA levels of alox5 were decreased in EGFP-positive leukocytes of TG(zlyz:EGFP) zebrafish at 6 hptt after Cnr2 signaling was activated by JWH-015 (Fig. 4G). Similarly, the Alox5 protein level was also down-regulated in THP-1 cells by JWH-015 induced activation of Cnr2 (Fig. 5A). These results indicate that the Alox5 pathway is a downstream target of the Cnr2 signaling in regulating the migration of leukocytes.

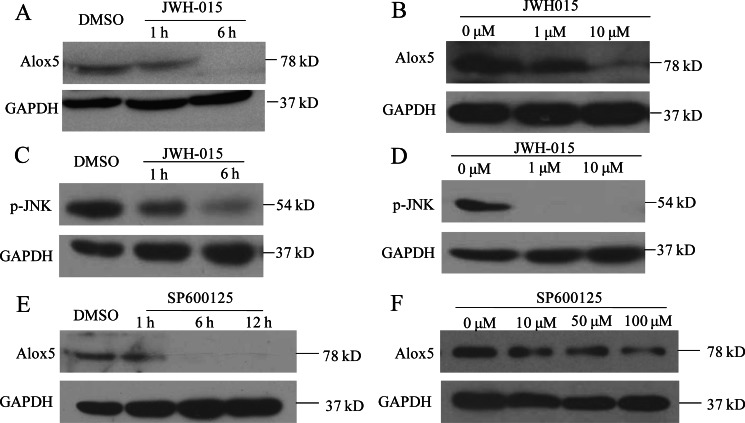

FIGURE 5.

Cnr2 activation down-regulates the expression of Alox5 through the JNK pathway in THP-1 cell line. A, Western blot detected Alox5 protein expression in the THP-1 cell line. JWH-015 treatment inhibited Alox5 protein expression in a time-dependent manner (1 h, 6 h) at the concentration of 20 μm and B, concentration-dependent (1 μm, 10 μm) manner for 6 h. C, Western blot of p-JNK in the THP-1 cell line with JWH-015 treatment in time-lapse (1 h, 6 h) and (D) concentration-lapse (1 μm, 10 μm) incubations. E, Western blot measuring Alox5 protein level in the THP-1 cell line with treatment of JNK-specific inhibitor SP600125 in time-lapse (1, 6, 12 h) at the concentration of 50 μm and (F) concentration-lapse (10, 50, 100 μm) incubations for 6 h.

We also found that combined treatment with WIN and AA-861 elicited significantly more inhibition of the recruitment of leukocytes to the wound in tail-transected zebrafish embryos than either of the two compounds alone (Fig. 4, H and I), indicating targeting both parts of the pathway is a more effective anti-inflammatory therapy. Similar cooperative effect was observed between the selective Cnr2 agonist, JWH-015, and AA-861 (supplemental Fig. S3, D and E).

Inhibition of Leukocyte Migration by Cnr2 Activation via JNK

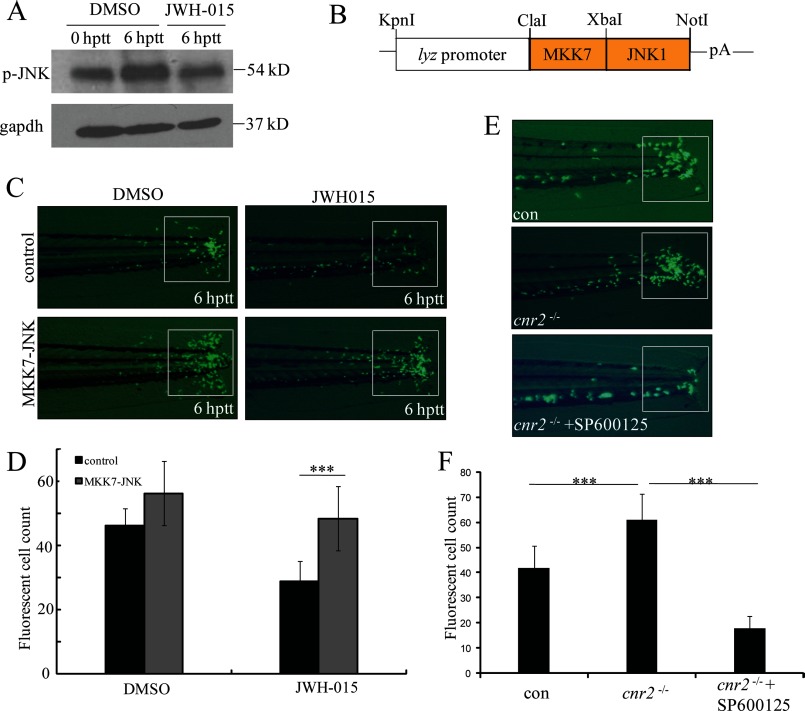

MAPK signaling cascades play a critical role in both immune cell development and the immune response to pathogens. Cnr2 signaling has been shown to regulate three major MAPKs, including extracellular signal-regulated protein kinases (ERK), p38 MAPK, and c-Jun NH2-terminal kinases (JNK) (29, 44–48). Our previous studies have shown that JNK is involved in leukocyte migration induced by acute injury (17). We went on to investigate whether Cnr2 inhibits leukocyte migration by regulating JNK activity. We found that JNK phosphorylation of whole embryo is increased in response to acute injury, whereas such increase is abolished by the activation of Cnr2 signaling by JWH-015 in tail-transected zebrafish at 6 hptt (Fig. 6A). Similarly, the phosphorylation of JNK is inhibited by JWH-015 in THP-1 cells in vitro (Fig. 5, C and D). These data suggest that inhibition of the inflammatory migration of leukocytes by Cnr2 activation acts, at least in part, by preventing JNK activation. To further test this idea, we checked the effect of a constitutively active JNK on regulating leukocyte migration. Previous studies have shown that fusion of MKK7 to JNK1 causes a constitutive activation of JNK (49). Based on the high conservation of the JNK pathway between zebrafish and mammals (50, 51), we generated a human MKK7-JNK1 fusion gene (Fig. 6B). We injected the zlyz-MKK7-JNK1 plasmid into TG(zlyz:EGFP) zebrafish embryos to induce constitutive JNK phosphorylation in EGFP-positive cells. Strikingly, constitutively activated JNK efficiently rescued the block of leukocyte migration in tail-transected zebrafish embryos by JWH-015 (Fig. 6, C and D). In addition, the JNK specific inhibitor SP600125 reversed the increased congregation of GFP-positive leukocytes at the wound in cnr2−/− embryos (Fig. 6, E and F). These results demonstrate that Cnr2 activation inhibits JNK activation, which underlies the inhibitory effect on leukocyte inflammatory migration by the Cnr2 agonist.

FIGURE 6.

Cnr2 inhibits leukocyte inflammatory migration by modulating the JNK pathway. A, Western blots were performed using a phospho-JNK antibody in zebrafish embryos at 0 hptt and 6 hptt, and JWH-015 treatment at 6 hptt. B, restriction map of the pIsceI-zlyc-MKK7-JNK1 construct expressing the fusion protein MKK7-JNK1 in zebrafish leukocytes. pA, SV40 polyadenylation site. C and D, inflammatory migration of EGFP-positive leukocytes in MKK7-JNK embryos was resistant to JWH-015 treatment. MKK7-JNK embryos were injected with the pIsceI-zlyc-MKK7-JNK1 plasmid. The in vivo leukocyte inflammatory migration was compared with controls and quantified. ***, p < 0.005. n = 15. E, JNK-specific inhibitor SP600125 treatment reduced the increased congregation of EGFP-positive cells in the tail of cnr2−/− embryos at a concentration of 50 μm and the congregated GFP-positive leukocytes in the tail were quantified. ***, p < 0.005. n = 15.

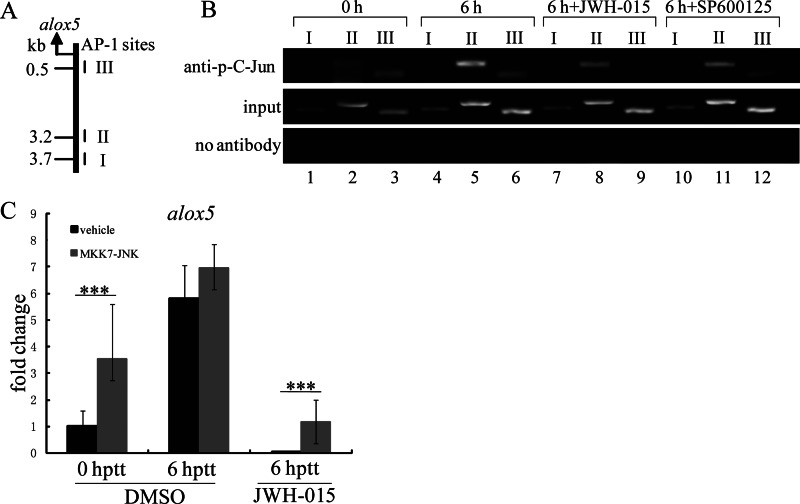

Transcriptional Suppression of alox5 via c-Jun Inactivation by Cnr2 Signaling

Because both JNK and Alox5 function downstream of Cnr2, it is possible that Alox5 expression is regulated by JNK activation. We tested this possibility and found that the JNK-specific inhibitor SP600125 down-regulated the expression of Alox5 in THP-1 cells (Fig. 5, E and F). c-Jun regulates the transcription of genes widely involved in cell migration, wound healing, and inflammation, and its activity is regulated by JNK (52–54). Decreased c-Jun-targeted gene transcription might be responsible for blocking leukocyte migration by Cnr2 activation. We tested whether alox5 is transcriptionally regulated by c-Jun, which in turn is activated by JNK in zebrafish. We first analyzed the promoter 4.0 kb upstream of the coding sequence region of alox5 with the online transcription factor predict software Alibaba 2.1 (www.gene-regulation.com/pub/programs.html#alibaba2) to look for potential transcription factor binding sites. We identified 3 putative AP-1 binding sites (Fig. 7A). E-ChIP was performed to test whether phosphorylated c-Jun (p-c-Jun) could bind directly to these sites in response to acute wound in vivo (Fig. 7B). As expected, there was little or no level of p-c-Jun binding to the AP-1 site I, II, and III at 0 hptt. In contrast, the binding activity of p-c-Jun to AP-1 site II and III, but not I, was markedly increased at 6 hptt. Interestingly, the increased binding activity of p-c-Jun to AP-1 site II or III could be completely abolished by either JWH-015-induced Cnr2 activation or SP600125-mediated inhibition of JNK. In addition, constitutive JNK activity up-regulated the mRNA level of alox5 in zebrafish EGFP-positive leukocytes at 6 hptt and could efficiently rescue the transcriptional inhibition by JWH-015-induced Cnr2 activation (Fig. 7C). These results demonstrate that alox5 is transcriptionally regulated by p-JNK activated c-Jun, and that Cnr2 signaling acts as an important negative regulator in leukocyte inflammatory migration by inhibiting the JNK-c-Jun-Alox5 axis.

FIGURE 7.

Transcriptional regulation of alox5 by phosphor-c-Jun dephosphorylation. A and B, measuring in vivo binding of phosphorylated c-Jun to the proximal AP-1 sites in the region of alox5 promoter by E-ChIP assay. Three putative AP-1 binding sites at the positions of 3.7, 3.2, and 0.5 kb upstream of the alox5 transcription start site are indicated by I, II, and III. E-ChIP results indicate the binding activity change of phosphorylated c-Jun in 0 hptt, 6 hptt, JWH-015 (50 μm), and SP600125 (100 μm)-treated embryos at 6 hptt. C, real-time PCR indicates the mRNA fold change of alox5 in EGFP-positive cells of TG(zlyz:EGFP) embryos at 0 hptt, 6 hptt, and JWH-015 treatment (40 μm) at 6 hptt. Compared with leukocytes of uninjected embryos, MKK7-JNK leukocytes expressed higher mRNA levels of alox5. ***, p < 0.05. n = 6.

DISCUSSION

In this report, we conducted the first large scale chemical screen on tail-transected TG(zlyz:EGFP) zebrafish embryos. We identified seven chemical compounds with immunomodulatory activity and elucidated the importance of the Cnr2-JNK-Alox5 pathway in regulating leukocyte inflammatory migration.

The block of Cnr2 signaling by cnr2 mutation induced an abnormal increase in leukocyte inflammatory migration, suggesting that Cnr2 signaling is activated by endocannabinoid in the normal inflammation process and acts as an important modulator of inflammation. The increased number of congregated leukocytes in the wound of cnr2−/− embryos phenocopies the increased congregation of Cnr2-deficient T cells in the CNS of the autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) mouse model (55), suggesting that our in vivo inflammation model is highly conserved with mammalian inflammation-associated disease processes. The zebrafish inflammation model would be useful to dissect the exact phenotype of the Cnr2-deficient immune cell.

It has been shown that Cnr2 signaling and the Alox5 pathway are both involved in the regulation of leukocyte migration (22–24). Previous studies showed that cannabidiol inhibits tumor cell growth by down-regulating the activity and expression of Alox5 (38), and it was also shown that there is a cooperative antineurotoxic effect between a selective Cnr2 agonist (JWH-015) and a specific Alox5 inhibitor (REV 5901) in THP-1 cells in vitro (56). Though these studies indicate a possible interaction between Cnr2 and Alox5, our findings demonstrate that Cnr2 signaling directly regulates Alox5 expression during the process of leukocyte inflammatory migration.

As the most highly activated target of JNK, activated c-Jun has been reported to directly trans-activate many key genes involved in the inflammation process (17, 52, 53). Here we demonstrate that alox5 is a direct target of c-Jun and that it could be transcriptionally up-regulated by phosphorylated c-Jun. As described in supplemental Fig. S5, in the process of acute inflammation in response to tail-transection, JNK is activated by phosphorylation, which in turn activates the transcription factor c-Jun. P-c-Jun subsequently binds to the AP-1 binding site in the promoter region upstream of the transcription start site of alox5 and trans-activates alox5 expression. Considering the modulation of Alox5 in immune cell migration, the JNK-c-Jun-Alox5 axis, at least in part, contributes to the in vivo leukocyte inflammatory migration response. It had been demonstrated that another Cnr2-specific agonist GP1a could decrease the level of intracellular cAMP (30), and other studies also indicated that cAMP leads to phosphorylation of JNK (57). So it is possible that Cnr2 activation inhibits the phosphorylation of JNK and subsequently inhibits the transcription of alox5 through reducing the level of cAMP. Our finding that the JNK-c-Jun-Alox5 axis could be efficiently blocked by Cnr2 signaling activation is consistent with the previous observation that Cnr2 activation inhibits human tumor cell proliferation by down-regulating the phosphorylation of JNK (58).

The cooperative effect between the Cnr2 agonist and the Alox5 inhibitor of leukocyte inflammatory migration implicates a new strategy for developing anti-inflammation therapies. The Cnr2 agonist WIN has shown great potential in delaying the progress of multiple sclerosis (59). Suppression of Alox5 pathway is also efficient in therapy of asthma (32, 33). Investigating the effect of a combined therapy with Cnr2 agonist and Alox5 inhibitor would be valuable in treating human diseases such as multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, atherosclerosis, asthma, or even cancer.

Several successful chemical genetic screens have been performed in zebrafish to identify suppressors and pathways of oncogene function, angiogenesis, or lipid metabolism (14, 60, 61). Combined with the fact that many well-established anti-inflammatory drugs work well in zebrafish (17, 62, 63), our screen results provide evidence for highly conserved signaling pathways involved in immune cell migration and inflammation. The targets of the seven hit compounds in our screen fall into different cell signaling pathways, some of which have been implicated in inflammation regulation in mouse or human, including Ca2+ signaling, the PI3K-AKT pathway, cannabinoid signaling, and the Alox5 pathway.

Considering the obvious toxic effects of the three compounds, forskolin, thapsigargin, and calcimycin on zebrafish embryos, these compounds may not be suitable for further anti-inflammatory drug development or may at least need to be modified for further investigation. Together, results of our in vivo chemical genetic screen with tail-transected TG(zlyz:EGFP) embryos show an efficient way to dissect cell migration pathways and to identify lead compounds with immunomodulatory activity.

Acknowledgments

We thank GlaxoSmithKline for providing us funding and the LOPAC chemical library, Dr. Sai-Juan Chen at Ruijin Hospital in Shanghai, and Dr. Yi Zhou at Children's Hospital in Boston for providing important suggestions on the project and revising the manuscript, as well as all the members of the laboratory for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by the National Basic Research Program of China (2007CB947003 and 2011CB964803), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (30830047, 31000636), and the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Science (XDA 01010106).

This article contains supplemental Tables S1 and S2 and Figs. S1—S5.

- hpf

- h-post-fertilization

- hptt

- h-post-tail-transection

- WIN

- (R)-(+)-WIN55,212,–2 mesylate

- Cnr

- cannabinoid receptor

- ZFN

- zinc finger nuclease

- DEX

- dexamethasone

- E-ChIP

- embryo-chromatin immunoprecipitation

- CoDA

- context-dependent assembly.

REFERENCES

- 1. Trapp B. D., Peterson J., Ransohoff R. M., Rudick R., Mörk S., Bö L. (1998) Axonal transection in the lesions of multiple sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 338, 278–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kucharova K., Chang Y., Boor A., Yong V. W., Stallcup W. B. (2011) Reduced inflammation accompanies diminished myelin damage and repair in the NG2 null mouse spinal cord. J. Neuroinflammation 8, 158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tak P. P., Bresnihan B. (2000) The pathogenesis and prevention of joint damage in rheumatoid arthritis: advances from synovial biopsy and tissue analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 43, 2619–2633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Combadière C., Potteaux S., Gao J. L., Esposito B., Casanova S., Lee E. J., Debré P., Tedgui A., Murphy P. M., Mallat Z. (2003) Decreased atherosclerotic lesion formation in CX3CR1/apolipoprotein E double knockout mice. Circulation 107, 1009–1016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Szekanecz Z., Szücs G., Szántó S., Koch A. E. (2006) Chemokines in rheumatic diseases. Curr. Drug Targets 7, 91–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Stockwell B. R. (2000) Chemical genetics: ligand-based discovery of gene function. Nat. Rev. Genet. 1, 116–125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gao M., Nettles R. E., Belema M., Snyder L. B., Nguyen V. N., Fridell R. A., Serrano-Wu M. H., Langley D. R., Sun J. H., O'Boyle D. R., 2nd, Lemm J. A., Wang C., Knipe J. O., Chien C., Colonno R. J., Grasela D. M., Meanwell N. A., Hamann L. G. (2010) Chemical genetics strategy identifies an HCV NS5A inhibitor with a potent clinical effect. Nature 465, 96–100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Venkatesh N., Feng Y., DeDecker B., Yacono P., Golan D., Mitchison T., McKeon F. (2004) Chemical genetics to identify NFAT inhibitors: potential of targeting calcium mobilization in immunosuppression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 8969–8974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. North T. E., Goessling W., Walkley C. R., Lengerke C., Kopani K. R., Lord A. M., Weber G. J., Bowman T. V., Jang I. H., Grosser T., Fitzgerald G. A., Daley G. Q., Orkin S. H., Zon L. I. (2007) Prostaglandin E2 regulates vertebrate haematopoietic stem cell homeostasis. Nature 447, 1007–1011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ridges S., Heaton W. L., Joshi D., Choi H., Eiring A., Batchelor L., Choudhry P., Manos E. J., Sofla H., Sanati A., Welborn S., Agarwal A., Spangrude G. J., Miles R. R., Cox J. E., Frazer J. K., Deininger M., Balan K., Sigman M., Muschen M., Perova T., Johnson R., Montpellier B., Guidos C. J., Jones D. A., Trede N. S. (2012) Zebrafish screen identifies novel compound with selective toxicity against leukemia. Blood 119, 5621–5631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kokel D., Bryan J., Laggner C., White R., Cheung C. Y., Mateus R., Healey D., Kim S., Werdich A. A., Haggarty S. J., Macrae C. A., Shoichet B., Peterson R. T. (2010) Rapid behavior-based identification of neuroactive small molecules in the zebrafish. Nat. Chem. Biol. 6, 231–237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Molina G., Vogt A., Bakan A., Dai W., Queiroz de Oliveira P., Znosko W., Smithgall T. E., Bahar I., Lazo J. S., Day B. W., Tsang M. (2009) Zebrafish chemical screening reveals an inhibitor of Dusp6 that expands cardiac cell lineages. Nat. Chem. Biol. 5, 680–687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Stern H. M., Murphey R. D., Shepard J. L., Amatruda J. F., Straub C. T., Pfaff K. L., Weber G., Tallarico J. A., King R. W., Zon L. I. (2005) Small molecules that delay S phase suppress a zebrafish bmyb mutant. Nat. Chem. Biol. 1, 366–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yeh J. R., Munson K. M., Elagib K. E., Goldfarb A. N., Sweetser D. A., Peterson R. T. (2009) Discovering chemical modifiers of oncogene-regulated hematopoietic differentiation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 5, 236–243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yu P. B., Hong C. C., Sachidanandan C., Babitt J. L., Deng D. Y., Hoyng S. A., Lin H. Y., Bloch K. D., Peterson R. T. (2008) Dorsomorphin inhibits BMP signals required for embryogenesis and iron metabolism. Nat. Chem. Biol. 4, 33–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Peterson R. T., Link B. A., Dowling J. E., Schreiber S. L. (2000) Small molecule developmental screens reveal the logic and timing of vertebrate development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 12965–12969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhang Y., Bai X. T., Zhu K. Y., Jin Y., Deng M., Le H. Y., Fu Y. F., Chen Y., Zhu J., Look A. T., Kanki J., Chen Z., Chen S. J., Liu T. X. (2008) In vivo interstitial migration of primitive macrophages mediated by JNK-matrix metalloproteinase 13 signaling in response to acute injury. J. Immunol. 181, 2155–2164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Soehnlein O., Lindbom L. (2010) Phagocyte partnership during the onset and resolution of inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 10, 427–439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lam C. S., Rastegar S., Strähle U. (2006) Distribution of cannabinoid receptor 1 in the CNS of zebrafish. Neuroscience 138, 83–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Matsuda L. A., Lolait S. J., Brownstein M. J., Young A. C., Bonner T. I. (1990) Structure of a cannabinoid receptor and functional expression of the cloned cDNA. Nature 346, 561–564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Galiègue S., Mary S., Marchand J., Dussossoy D., Carrière D., Carayon P., Bouaboula M., Shire D., Le Fur G., Casellas P. (1995) Expression of central and peripheral cannabinoid receptors in human immune tissues and leukocyte subpopulations. Eur. J. Biochem. 232, 54–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Newton C. A., Klein T. W., Friedman H. (1994) Secondary immunity to Legionella pneumophila and Th1 activity are suppressed by Δ-9-tetrahydrocannabinol injection. Infect Immun. 62, 4015–4020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Csóka B., Németh Z. H., Mukhopadhyay P., Spolarics Z., Rajesh M., Federici S., Deitch E. A., Bátkai S., Pacher P., Haskó G. (2009) CB2 cannabinoid receptors contribute to bacterial invasion and mortality in polymicrobial sepsis. PLoS One 4, e6409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tschöp J., Kasten K. R., Nogueiras R., Goetzman H. S., Cave C. M., England L. G., Dattilo J., Lentsch A. B., Tschöp M. H., Caldwell C. C. (2009) The cannabinoid receptor 2 is critical for the host response to sepsis. J. Immunol. 183, 499–505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mukhopadhyay P., Rajesh M., Pan H., Patel V., Mukhopadhyay B., Bátkai S., Gao B., Haskó G., Pacher P. (2010) Cannabinoid-2 receptor limits inflammation, oxidative/nitrosative stress, and cell death in nephropathy. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 48, 457–467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhang M., Martin B. R., Adler M. W., Razdan R. K., Jallo J. I., Tuma R. F. (2007) Cannabinoid CB(2) receptor activation decreases cerebral infarction in a mouse focal ischemia/reperfusion model. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 27, 1387–1396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ghosh S., Preet A., Groopman J. E., Ganju R. K. (2006) Cannabinoid receptor CB2 modulates the CXCL12/CXCR4-mediated chemotaxis of T lymphocytes. Mol. Immunol. 43, 2169–2179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Raborn E. S., Marciano-Cabral F., Buckley N. E., Martin B. R., Cabral G. A. (2008) The cannabinoid Δ-9-tetrahydrocannabinol mediates inhibition of macrophage chemotaxis to RANTES/CCL5: linkage to the CB2 receptor. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 3, 117–129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Romero-Sandoval E. A., Horvath R., Landry R. P., DeLeo J. A. (2009) Cannabinoid receptor type 2 activation induces a microglial anti-inflammatory phenotype and reduces migration via MKP induction and ERK dephosphorylation. Mol. Pain 5, 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Adhikary S., Kocieda V. P., Yen J. H., Tuma R. F., Ganea D. (2012) Signaling through cannabinoid receptor 2 suppresses murine dendritic cell migration by inhibiting matrix metalloproteinase 9 expression. Blood 120, 3741–3749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Basu S., Dittel B. N. (2011) Unraveling the complexities of cannabinoid receptor 2 (CB2) immune regulation in health and disease. Immunol. Res. 51, 26–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tager A. M., Dufour J. H., Goodarzi K., Bercury S. D., von Andrian U. H., Luster A. D. (2000) BLTR mediates leukotriene B(4)-induced chemotaxis and adhesion and plays a dominant role in eosinophil accumulation in a murine model of peritonitis. J. Exp. Med. 192, 439–446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Klegeris A., McGeer P. L. (2003) Toxicity of human monocytic THP-1 cells and microglia toward SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells is reduced by inhibitors of 5-lipoxygenase and its activating protein FLAP. J. Leukoc. Biol. 73, 369–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Monteiro A. P., Pinheiro C. S., Luna-Gomes T., Alves L. R., Maya-Monteiro C. M., Porto B. N., Barja-Fidalgo C., Benjamim C. F., Peters-Golden M., Bandeira-Melo C., Bozza M. T., Canetti C. (2011) Leukotriene B4 mediates neutrophil migration induced by heme. J. Immunol. 186, 6562–6567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ligresti A., Moriello A. S., Starowicz K., Matias I., Pisanti S., De Petrocellis L., Laezza C., Portella G., Bifulco M., Di Marzo V. (2006) Antitumor activity of plant cannabinoids with emphasis on the effect of cannabidiol on human breast carcinoma. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 318, 1375–1387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Castillo A., Tolón M. R., Fernández-Ruiz J., Romero J., Martinez-Orgado J. (2010) The neuroprotective effect of cannabidiol in an in vitro model of newborn hypoxic-ischemic brain damage in mice is mediated by CB(2) and adenosine receptors. Neurobiol. Dis. 37, 434–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sacerdote P., Martucci C., Vaccani A., Bariselli F., Panerai A. E., Colombo A., Parolaro D., Massi P. (2005) The nonpsychoactive component of marijuana cannabidiol modulates chemotaxis and IL-10 and IL-12 production of murine macrophages both in vivo and in vitro. J. Neuroimmunol. 159, 97–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Massi P., Valenti M., Vaccani A., Gasperi V., Perletti G., Marras E., Fezza F., Maccarrone M., Parolaro D. (2008) 5-Lipoxygenase and anandamide hydrolase (FAAH) mediate the antitumor activity of cannabidiol, a non-psychoactive cannabinoid. J. Neurochem. 104, 1091–1100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sander J. D., Dahlborg E. J., Goodwin M. J., Cade L., Zhang F., Cifuentes D., Curtin S. J., Blackburn J. S., Thibodeau-Beganny S., Qi Y., Pierick C. J., Hoffman E., Maeder M. L., Khayter C., Reyon D., Dobbs D., Langenau D. M., Stupar R. M., Giraldez A. J., Voytas D. F., Peterson R. T., Yeh J. R., Joung J. K. (2011) Selection-free zinc-finger-nuclease engineering by context-dependent assembly (CoDA). Nat. Methods 8, 67–69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Link V., Shevchenko A., Heisenberg C. P. (2006) Proteomics of early zebrafish embryos. BMC Dev. Biol. 6, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wardle F. C., Odom D. T., Bell G. W., Yuan B., Danford T. W., Wiellette E. L., Herbolsheimer E., Sive H. L., Young R. A., Smith J. C. (2006) Zebrafish promoter microarrays identify actively transcribed embryonic genes. Genome Biol. 7, R71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Griffin G., Fernando S. R., Ross R. A., McKay N. G., Ashford M. L., Shire D., Huffman J. W., Yu S., Lainton J. A., Pertwee R. G. (1997) Evidence for the presence of CB2-like cannabinoid receptors on peripheral nerve terminals. Eur J Pharmacol 339, 53–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Yoshimoto T., Yokoyama C., Ochi K., Yamamoto S., Maki Y., Ashida Y., Terao S., Shiraishi M. (1982) 2,3,5-Trimethyl-6-(12-hydroxy-5,10-dodecadiynyl)-1,4-benzoquinone (AA861), a selective inhibitor of the 5-lipoxygenase reaction and the biosynthesis of slow-reacting substance of anaphylaxis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 713, 470–473 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Correa F., Docagne F., Mestre L., Clemente D., Hernangómez M., Loría F., Guaza C. (2009) A role for CB2 receptors in anandamide signalling pathways involved in the regulation of IL-12 and IL-23 in microglial cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 77, 86–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Correa F., Hernangomez M., Mestre L., Loria F., Spagnolo A., Docagne F., Di Marzo V., Guaza C. (2010) Anandamide enhances IL-10 production in activated microglia by targeting CB(2) receptors: roles of ERK1/2, JNK, and NF-κB. Glia 58, 135–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Börner C., Smida M., Höllt V., Schraven B., Kraus J. (2009) Cannabinoid receptor type 1- and 2-mediated increase in cyclic AMP inhibits T cell receptor-triggered signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 35450–35460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gustafsson K., Christensson B., Sander B., Flygare J. (2006) Cannabinoid receptor-mediated apoptosis induced by R(+)-methanandamide and Win55,212–2 is associated with ceramide accumulation and p38 activation in mantle cell lymphoma. Mol. Pharmacol. 70, 1612–1620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Adhikary S., Kocieda V. P., Yen J. H., Tuma R. F., Ganea D. (2012) Signaling through cannabinoid receptor 2 suppresses murine dendritic cell migration by inhibiting matrix metalloproteinase 9 expression. Blood 120, 3741–3749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lei K., Nimnual A., Zong W. X., Kennedy N. J., Flavell R. A., Thompson C. B., Bar-Sagi D., Davis R. J. (2002) The Bax subfamily of Bcl2-related proteins is essential for apoptotic signal transduction by c-Jun NH(2)-terminal kinase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 4929–4942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Krens S. F., He S., Spaink H. P., Snaar-Jagalska B. E. (2006) Characterization and expression patterns of the MAPK family in zebrafish. Gene Expr. Patterns 6, 1019–1026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Seo J., Asaoka Y., Nagai Y., Hirayama J., Yamasaki T., Namae M., Ohata S., Shimizu N., Negishi T., Kitagawa D., Kondoh H., Furutani-Seiki M., Penninger J. M., Katada T., Nishina H. (2010) Negative regulation of wnt11 expression by Jnk signaling during zebrafish gastrulation. J. Cell. Biochem. 110, 1022–1037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Fraczek L. A., Martin C. B., Martin B. K. (2011) c-Jun and c-Fos regulate the complement factor H promoter in murine astrocytes. Mol. Immunol. 49, 201–210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hosoda H., Tamura H., Kida S., Nagaoka I. (2011) Transcriptional regulation of mouse TREM-1 gene in RAW264.7 macrophage-like cells. Life Sci. 89, 115–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Grose R. (2003) Epithelial migration: open your eyes to c-Jun. Curr. Biol. 13, R678–680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Maresz K., Pryce G., Ponomarev E. D., Marsicano G., Croxford J. L., Shriver L. P., Ledent C., Cheng X., Carrier E. J., Mann M. K., Giovannoni G., Pertwee R. G., Yamamura T., Buckley N. E., Hillard C. J., Lutz B., Baker D., Dittel B. N. (2007) Direct suppression of CNS autoimmune inflammation via the cannabinoid receptor CB1 on neurons and CB2 on autoreactive T cells. Nat. Med. 13, 492–497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Klegeris A., Bissonnette C. J., McGeer P. L. (2003) Reduction of human monocytic cell neurotoxicity and cytokine secretion by ligands of the cannabinoid-type CB2 receptor. Br. J. Pharmacol. 139, 775–786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Gerits N., Kostenko S., Shiryaev A., Johannessen M., Moens U. (2008) Relations between the mitogen-activated protein kinase and the cAMP-dependent protein kinase pathways: comradeship and hostility. Cell Signal. 20, 1592–1607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Olea-Herrero N., Vara D., Malagarie-Cazenave S., Díaz-Laviada I. (2009) Inhibition of human tumour prostate PC-3 cell growth by cannabinoids R(+)-Methanandamide and JWH-015: involvement of CB2. Br. J. Cancer 101, 940–950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Ni X., Geller E. B., Eppihimer M. J., Eisenstein T. K., Adler M. W., Tuma R. F. (2004) Win 55212–2, a cannabinoid receptor agonist, attenuates leukocyte/endothelial interactions in an experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis model. Mult Scler. 10, 158–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Wu X., Zhong H., Song J., Damoiseaux R., Yang Z., Lin S. (2006) Mycophenolic acid is a potent inhibitor of angiogenesis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 26, 2414–2416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Clifton J. D., Lucumi E., Myers M. C., Napper A., Hama K., Farber S. A., Smith A. B., 3rd, Huryn D. M., Diamond S. L., Pack M. (2010) Identification of novel inhibitors of dietary lipid absorption using zebrafish. PLoS One 5, e12386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Loynes C. A., Martin J. S., Robertson A., Trushell D. M., Ingham P. W., Whyte M. K., Renshaw S. A. (2010) Pivotal Advance: Pharmacological manipulation of inflammation resolution during spontaneously resolving tissue neutrophilia in the zebrafish. J. Leukoc. Biol. 87, 203–212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Renshaw S. A., Loynes C. A., Trushell D. M., Elworthy S., Ingham P. W., Whyte M. K. (2006) A transgenic zebrafish model of neutrophilic inflammation. Blood 108, 3976–3978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]