Background: MATII biosynthesizes AdoMet, which supplies methyl group for methylation of molecules, including histone.

Results: MATII interacts with histone methyltransferase SETDB1 and inhibits COX-2 gene expression.

Conclusion: AdoMet synthesis and histone methylation are coupled on chromatin by a physical interaction of MATII and SETDB1 at the MafK target genes.

Significance: MATII may be important for both gene-specific and epigenome-wide regulation of histone methylation.

Keywords: Chromatin Regulation, Cyclooxygenase (COX) Pathway, Heme Oxygenase, Histone Methylation, S-adenosylmethionine (AdoMet)

Abstract

Methionine adenosyltransferase (MAT) synthesizes S-adenosylmethionine (AdoMet), which is utilized as a methyl donor in transmethylation reactions involving histones. MATIIα, a MAT isozyme, serves as a transcriptional corepressor in the oxidative stress response and forms the AdoMet-integrating transcription regulation module, affecting histone methyltransferase activities. However, the identities of genes regulated by MATIIα or its associated methyltransferases are unclear. We show that MATIIα represses the expression of cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2), encoded by Ptgs2, by specifically interacting with histone H3K9 methyltransferase SETDB1, thereby promoting the trimethylation of H3K9 at the COX-2 locus. We discuss both gene-specific and epigenome-wide functions of MATIIα.

Introduction

Methionine adenosyltransferase (MAT)2 catalyzes the synthesis of S-adenosylmethionine (AdoMet) (1). AdoMet is an intermediate product in the methionine cycle (2) and is utilized as a methyl donor in the transmethylation of diverse substrates, including histones, by specific methyltransferases (3). MAT is present in all living organisms, and three isozymes of MAT are known in mammals (1, 4). MATII is composed of α and β subunits and is widely expressed (1). The catalytic subunit MATIIα is encoded by the MAT2A gene, and its catalytic activity is enhanced or inhibited by the regulatory subunit MATIIβ, which is encoded by the MAT2B gene (5, 6).

The transcription factor Bach1 represses genes related to heme function and metabolism such as globin and heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) by forming heterodimers with the small Maf oncoproteins (7, 8) MATIIα serves as a transcriptional corepressor of MafK-Bach1 (9). Together, these proteins repress the expression of HO-1 gene (10), an enzyme implicated in iron reutilization, anti-inflammation, and cytoprotection. MATIIα and -β form a nuclear AdoMet-integrating transcription regulation module that further interacts with histone methyltransferase activities and other chromatin regulators (9). However, the identities of the histone methyltransferase(s) associated with MATIIα are unclear. In addition, little is known about the downstream target genes of MATIIα other than HO-1.

The gene expression tends to be silenced in heterochromatin and to be activated or poised for expression in euchromatin (11). These distinct chromatin structures are generated depending, in part, on histone modifications, including methylation. For example, methylation of lysine 4 of histone H3 (H3K4) is related to transcriptional activation (12), whereas methylation of histone H3K9 is related to transcriptional repression (13). Each methylation reaction is catalyzed by a specific methyltransferase. For example, SETDB1 and Suv39h1 catalyze the trimethylation of histone H3K9 for transcriptional repression (11).

In this report, we demonstrate that the Ptgs2 gene encoding cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2/prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2) is a direct target of MATIIα. COX-2 is an inducible enzyme required for the biosynthesis of prostanoids and contributes to inflammation, angiogenesis, and tumorigenesis (14, 15). The COX-2 gene locus is epigenetically regulated, and its chromatin structure changes to activate the transcription of the gene (16). We found that MATIIα, MATIIβ, MafK, and SETDB1 were recruited to the enhancer and promoter of the COX-2 gene to repress its expression in part by promoting H3K9 methylation.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture

MEFs were isolated and immortalized as described previously (17). Immortalized MEFs (iMEFs) were maintained in DMEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum FBS (Invitrogen), penicillin (100 units/ml), streptomycin (0.1 mg/ml), and 4500 mg/liter glutamine. THP-1 cells were maintained as described previously (18, 19). Mouse hepatoma cells (Hepa-1 cells) and murine erythroleukemia cells were maintained as described previously (9).

Plasmids

The pEF1α/BirA and pEF1α/FLBio-MATIIα were utilized as described previously (9, 20)

Construction of Stable Cell Lines

The iMEFs were plated at a density of 1 × 106 per 10-cm diameter dish. The cells were cultured for 2 days and transfected with 3 μg of pEF1α/FLBio-MATIIα, together with pEF1α/BirA, using an electroporation kit (Nucleofector for MEFs, Lonza). The transfected cells were subsequently cultured in DMEM containing 1.5 mg/ml G418 and 10 μg/ml puromycin for 2 weeks.

Purification of MATIIα-associated Proteins

The purification of MATIIα-associated proteins was carried out as described previously (9). The nuclear fraction from iMEFs was extracted as described previously (21).

Immunoblot Analysis

For histone modification analysis, histones corresponding to 1 × 106 cells were purified by acid extraction (22). Whole cell extracts and SDS-PAGE were performed using the cells as described previously (23).

Antibodies

The antibodies used in this study were anti-Ash1 (ab4477, Abcam), anti-COX-2 (ab52237, Abcam), anti-H3K9 acetylation (07-352, Millipore), anti-H3K27 acetylation (07-360, Millipore), anti-RIZ1 (ab9710, Abcam), anti-SETDB1 (11231-1-AP, Protein Group, Inc.), and anti-Suv39h1 (ab12405, ChIP Grade, Abcam). Other antibodies were utilized as described previously (9). Anti-MATIIα or -β antibodies were raised by immunizing rabbits with purified recombinant MATIIα or -β (His6-tagged mouse MATIIα or -β) expressed in Escherichia coli.

RNA Interference

Stealth RNAi duplexes were designed to target mouse Mat2a, Setdb1, and human MAT2A using the BLOCK-iT RNAi Designer (Invitrogen). For knockdown of mouse Mat2a and Setdb1, iMEFs (2 × 106 cells) were electroporated with 6 μl of 20 μm stock Stealth RNAi duplexes (siMATIIα) using the Nucleofector and MEF1 Nucleofector kit (VPD-1004, Lonza). The cells were cultured in a 10-cm diameter culture dish for 56 h. For knockdown of human MAT2A, THP-1 cells (5 × 106 cells) were electroporated with 6 μl of 20 μm stock Stealth RNAi duplexes (siMATIIα) using the Nucleofector and Nucleofector solution kit V (VCA-1003, Lonza). The cells were cultured in a 10-cm diameter culture dish for 24 h. Total RNA was harvested from the cells after electroporation to perform gene expression profiling. Sequences of the human Stealth RNAi used in this study were as follows: MAT2A RNAi, 5′-AUCAAGGACAGCAUCACUGAUUUGG-3′; control RNAi, 5′-AGGAGGAUAUUACCAUGGACAAGAC-3′. Sequences of the mouse Stealth RNAi used in this study were as follows: Setdb1 RNAi, 5′-UCAAGUUUGGCAUCAAUGAUGUAGC-3′; control RNAi, 5′-AGGAGGAUAUUACCAUGAAGAAGAC-3′. Mat2a RNAi sequences were described previously (9).

RNA Isolation and Quantitative RT-PCR

RNA isolation and purification from iMEFs, THP-1, and Hepa-1 cells were performed using a total RNA isolation mini kit according to the protocol provided by the manufacturer (Agilent Technologies). The quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed with a LightCycler (Roche Applied Science). The primers for mouse Mat2a, HO-1, and β-actin were described previously (9). The other primers used for mouse mRNA expression are as follows: Cox-2, 5′-CAATGAGTACCGCAAACGCT-3′ and 5′-TCATGGAACTGTACCCTGCC-3′; Ptges, 5′-TTACAGGAGTGACCCAGATGTG-3′ and 5′-GTGAGGACAACGAGGAAATG-3′; Fas, 5′-TATCAAGGAGGCCCATTTTGC-3′ and 5′-TGTTTCCACCTCTAAACCATGCT-3′; Noxa, 5′-GTGCACCGGACATAACTG-3′ and 5′-AGCACACTCGTCCTTCAAG-3′; Igfbp3, 5′-TCTAAGCGGGAGACAGAATACG-3′ and 5′-CTCTGGGACTCAGCACATTGA-3′; Gadd45b, 5′-CATTGGGCACAACCGAAGC-3′ and 5′-CCATTGGTTATTGCCTCTGCT-3′. The other primers used for human mRNA expression are as follows: MAT2A, 5′-ATGAACGGACAGCTCAACGG-3′ and 5′-CCAGCAAGAAGGATCATTCCAG-3′; GAPDH, 5′-GCAAAAGGGTCATCATCTC-3′ and 5′-TGTGGTCATGAGTCCTTCCA-3′; HO-1, 5′-CTTTCAGAAGGGCCAGGTGA-3′ and 5′-GTAGACAGGGGCGAAGACTG-3′; COX-2, 5′-TTTGCATTCTTTGCCCAGCA-3′ and 5′-CGCAGTTTACGCTGTCTAGC-3′.

Microarray Expression Profiling

Preparation of total RNAs from iMEFs was carried out using a total RNA isolation mini kit (Agilent Technologies). Agilent whole mouse genome (4 × 44K, G4122F) arrays were used for this study, as described previously (23). The analysis and clustering of genes were performed using the GeneSpring software package (Agilent Technologies).

ChIP Analysis

Chromatin fixation and purification were performed as described previously (7) with a modification. Ethylene glycolbis was utilized as a cross-linking agent for chromatin fixation (24). The enrichment of the DNA template was analyzed by quantitative PCR (qPCR). The primers for mouse HO-1 (E1, E2, and promoter) were described previously (9). Other primers used in this study are as follows: COX-2 (up 3 kb), 5′-GTAGAGACAGGAGGATGCAAGAA-3′ and 5′-TAAGTATGTAGATTCCTCCCGCA-3′; COX-2 (MARE), 5′-GTTTGACACCATGCACTTCC-3′ and 5′-CTGACTCTGCGGAAGTCTCC-3′; COX-2 promoter, 5′-CCTTCGTCTCTCATTTGCGT-3′ and 5′-CAGTGCTGAGTTCCTTCGTG-3′; Col11a2 exon, 5′-GAAACATGTGTTCCTCTTTCCAG-3′ and 5′-CTCATTCGTCTTCTGTGTCAAGA-3′. The relative enrichment was calculated as the difference between the specific antibody and normal IgG signals.

RESULTS

Identification of MATIIα-regulated Genes

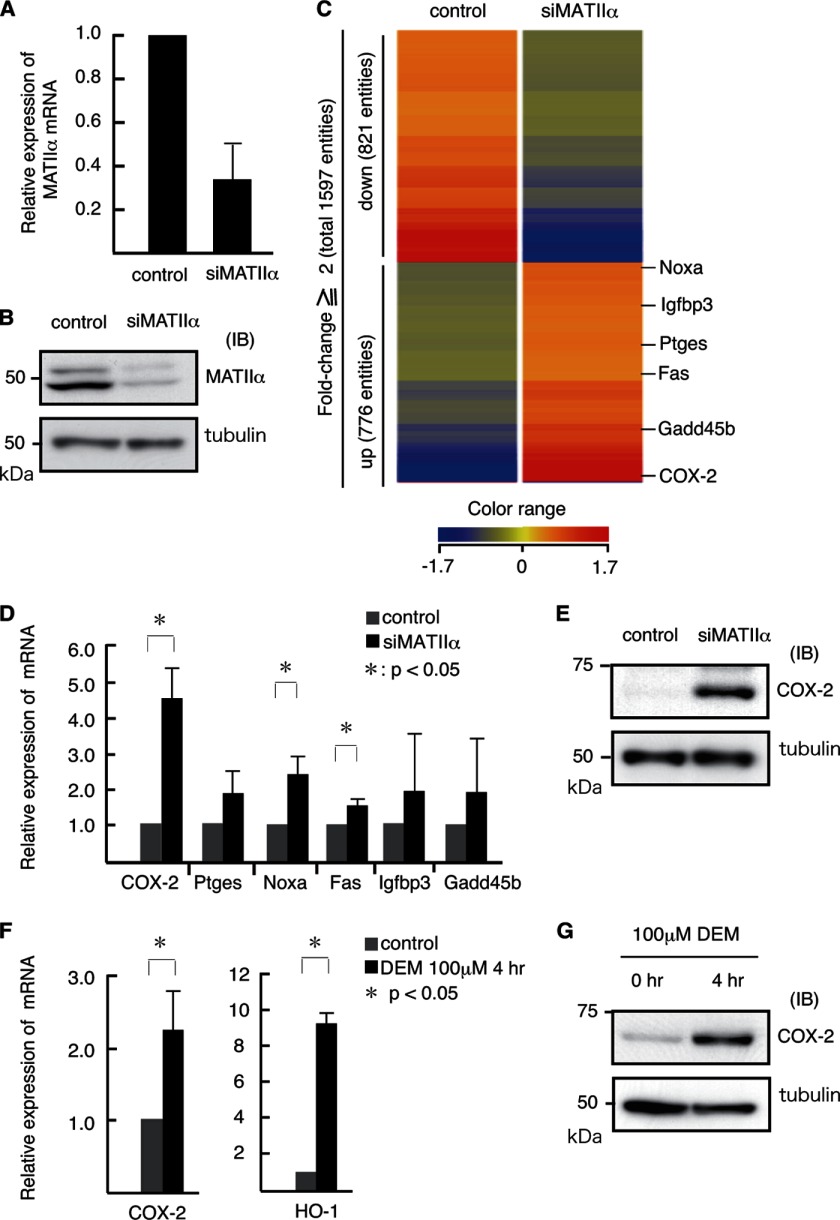

We performed a transient knockdown (KD) of Mat2a using iMEFs to identify MATIIα-regulated genes (Figs. 1, A and B). Using a previously reported RNAi sequence (9), we could achieve roughly 70% reduction of the Mat2a mRNA expression. We compared the gene expression profiles between the control and MATIIα KD cells using a DNA microarray analysis (Fig. 1C). Of the 41,252 gene probes included on the arrays, the expression levels of 1,597 gene probes were altered by >2-fold in the MATIIα KD cells compared with control cells. Among the 1,597 gene probes affected, 776 and 821 probes showed up- and down-regulation, respectively. These affected genes were not enriched for specific gene ontology terms, thus suggesting that MATIIα is involved in diverse cellular processes. We noticed that enzymes in the arachidonic acid cascade, namely COX-2 (Ptgs2) and prostaglandin E synthase (Ptges), were up-regulated in MATIIα KD cells. We also found that p53 target genes such as Noxa, Fas, Igfbp3, and Gadd45b were up-regulated (Table 1). Using a qRT-PCR, we found that MATIIα KD resulted in significant elevation of the mRNAs of Noxa, Fas, and COX-2, whereas Igfbp3, Gadd45b, and Ptges were only modestly affected (Fig. 1D). We also confirmed by an immunoblot analysis that MATIIα repressed COX-2 expression (Fig. 1E). We therefore focused on the COX-2 gene for further analysis because the effect of MATIIα depletion was most remarkable, and its expression was induced in response to oxidative stress or diethylmaleate, similar to HO-1 (Fig. 1, F and G) (7).

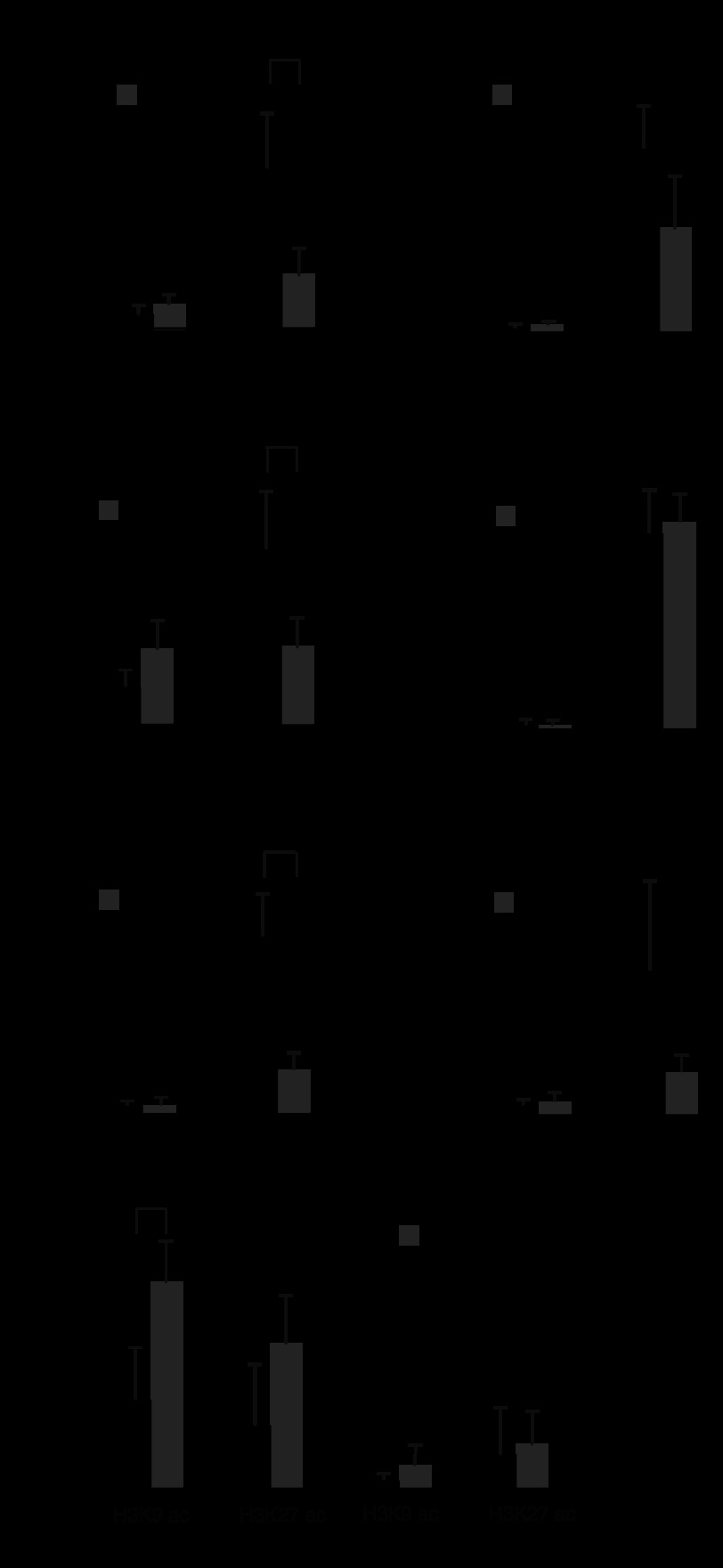

FIGURE 1.

Derepression of COX-2 in MATIIα KD iMEFs. A and B, effects of siRNA on the Mat2a expression in iMEFs. The levels of mRNA (A) and protein (B) were compared. C, DNA microarray analysis of the gene expression in control and MATIIα KD iMEFs. The heat map shows genes with >2-fold changes. D, qPCR analyses of putative MATIIα target genes (derived from C) in control (gray) and MATIIα KD (black) iMEFs. The expression levels of the genes in the control were arbitrarily set at 1. The β-actin mRNA expression level was used to normalize the results. The averages of three independent experiments with S.D. are shown. p values (Student's t test) for differences between the control and MATIIα KD are indicated. E, immunoblot (IB) analysis of COX-2 in control and MATIIα KD iMEFs. F, qPCR analyses of the expression of COX-2 and HO-1 in control (gray) and diethylmaleate (DEM) stimulated (black) iMEFs. The results are as shown in D. G, the results of the immunoblot analysis of COX-2 expression in control and iMEFs treated with diethylmaleate.

TABLE 1.

Candidates for MATIIα target genes

Shown is a list of MATIIα target genes that were up-regulated in MATIIα knockdown iMEFs in comparison with control iMEFs. The same GenBankTM accession no. genes are not shown.

| GenBankTM accession no. | Common name | Product |

|---|---|---|

| NM_011198 | Ptgs2 (COX-2) | Prostaglandin synthase-2 (cyclooxygenase-2) |

| NM_133783 | Ptges | Prostaglandin E synthase |

| NM_021451 | Noxa | Phorbol-12 myristate-13 acetate-induced protein 1 |

| NM_008343 | Igfbp3 | Insulin-like growth factor binding protein 3 |

| NM_007988 | Fas | TNF receptor superfamily member 6 |

| NM_008655 | Gadd45b | Growth arrest and DNA-damage-inducible 45 β |

Repression of COX-2 Expression by MATII

To investigate whether the MATII regulates the COX-2 gene in the context of inflammation, we carried out MAT2A knockdown using THP-1 cells, which are derived from human acute monocytic leukemia (Fig. 2, A and B) (18, 19). Using qRT-PCR, we confirmed MATIIα KD (Fig. 2A). The mRNA levels of COX-2 modestly but reproducibly increased upon MATIIα KD (Fig. 2B). These results suggest that MATII may regulate the COX-2 expression in the monomacrophage system. To further elucidate the regulation of COX-2 by MATII in different cells, we carried out MAT2A knockdown using Hepa-1 cells (Fig. 2C). The mRNA levels of COX-2 also increased upon MATIIα KD (Fig. 2D).

FIGURE 2.

Derepression of COX-2 in MATIIα KD THP-1 and Hepa-1 cells. A and C, effects of siRNA on the MATIIα expression in THP-1 (A) and Hepa-1 (C) cells. The levels of mRNA were compared. B, qPCR analyses of COX-2 and HO-1 mRNA in control (gray) and MATIIα KD (black) THP-1 cells. The results are shown as in Fig. 1D. D, qPCR analyses of COX-2 in control (gray) and MATIIα KD (black) Hepa-1 cells. The results are shown as above.

MATII Recruitment to the HO-1 Locus

We determined whether MATII was recruited to the COX-2 gene locus. We generated new anti-MATIIα and anti-MATIIβ antibodies and performed immunoprecipitation and immunoblot analyses, confirming their reactivity with the respective endogenous proteins in murine erythroleukemia cells (Fig. 3A). Using these antibodies in ChIP assays, we found that endogenous MATIIα and -β were specifically recruited to the E1 enhancer and promoter of HO-1 in iMEFs (Fig. 3, B and C). They tended to bind to the E2 enhancer, but the results were not statistically significant. MafK was specifically recruited to both of the two enhancers of HO-1 (Fig. 3C). These observations were consistent with our previous findings using epitope-tagged MATIIα in Hepa1 cells (9).

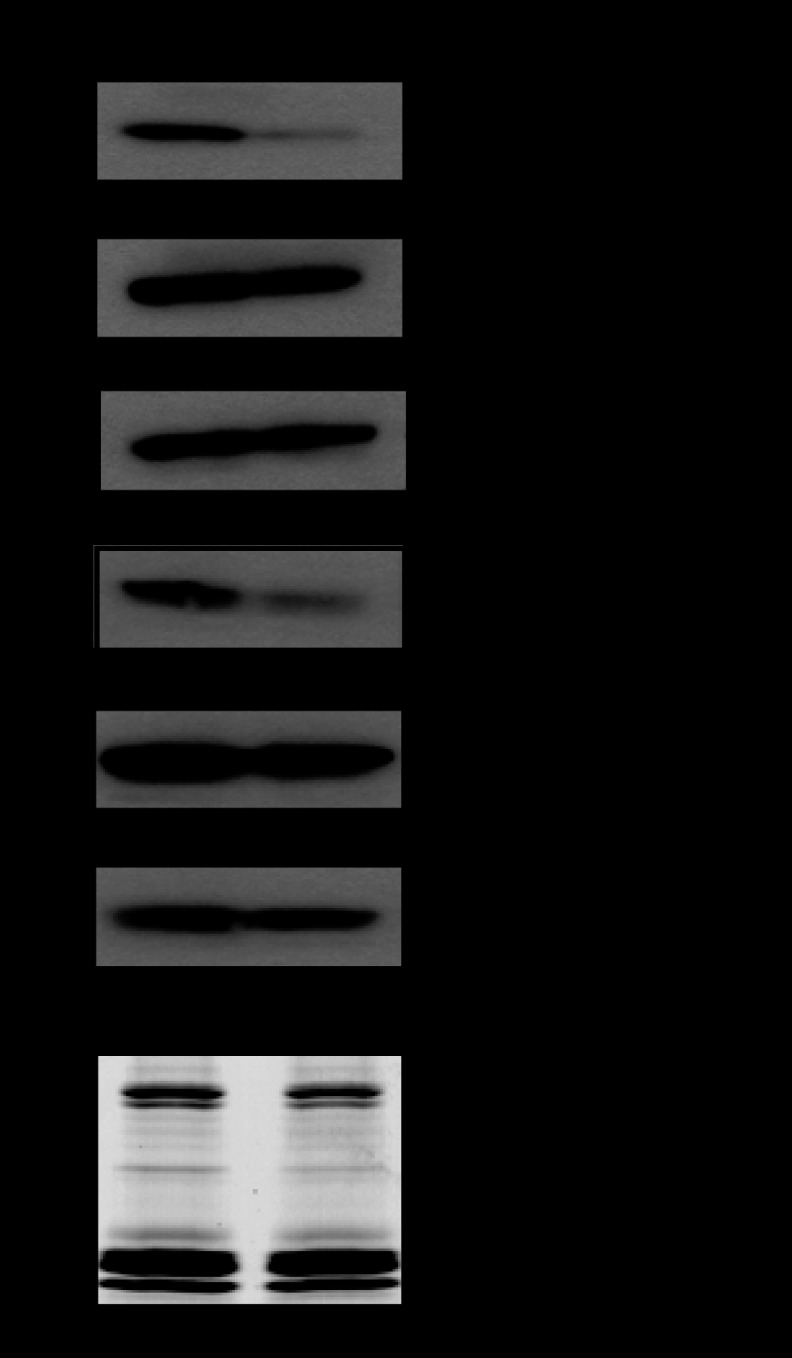

FIGURE 3.

MATII recruitment to the HO-1 locus. A, following the immunoprecipitation of whole extracts from murine erythroleukemia cells with anti-MATIIα, -β, or IgG antibodies, the samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and detected with the indicated antibodies. B, a schematic representation of the mouse HO-1 locus. The lines below indicate the PCR primer pairs used for the ChIP analysis. C, ChIP assays were performed using indicated antibodies with extracts from iMEFs. The relative levels of enrichment of the indicated genomic DNA regions are shown with the S.D. p values (Student's t test) for differences between each antibody and control rabbit IgG are indicated. IB, immunoblot.

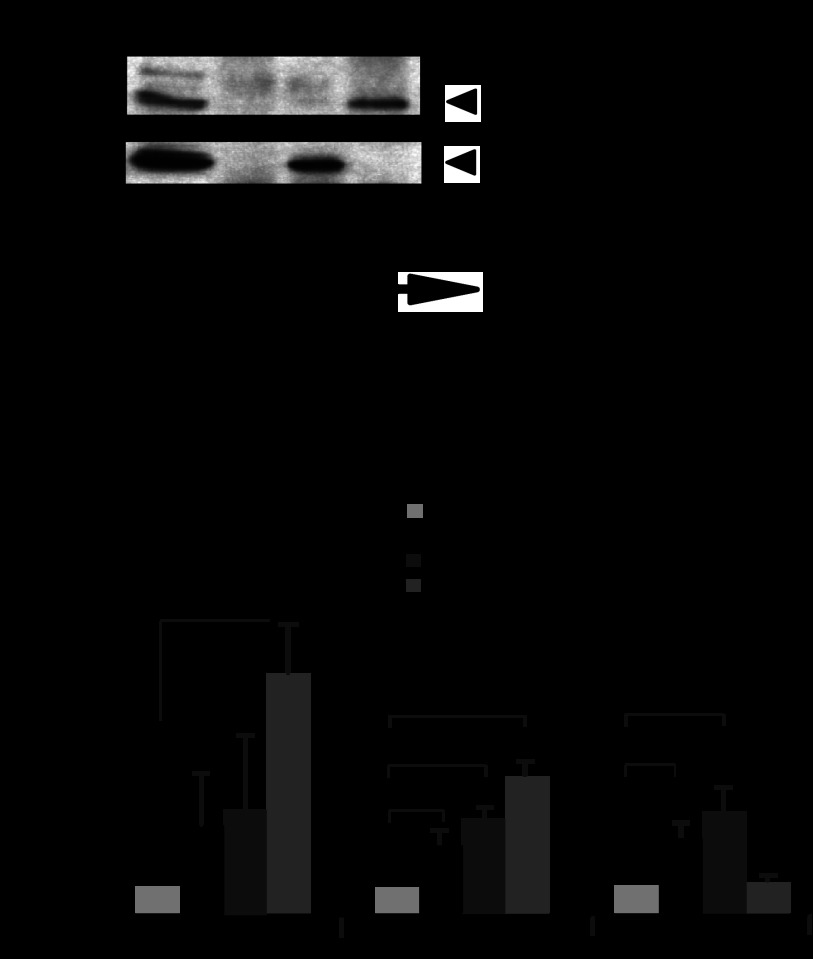

MATII Recruitment to the COX-2 Locus

Having established the ChIP conditions using the new antibodies, we next examined the recruitment of MATIIα, MATIIβ, and MafK at the COX-2 gene locus in iMEFs (Fig. 4). We identified one putative MARE sequence at 1.6 kbp upstream of the COX-2 gene promoter (Fig. 4A). MATIIα and -β were both recruited to the putative MARE and promoter regions of the COX-2 gene (Fig. 4, B and C). In contrast, their binding to the further upstream region (i.e. up 3 kb) was less apparent. MafK was specifically recruited to the putative MARE (Fig. 4D). These data indicated that both MATIIα and -β were recruited to the putative COX-2 gene MARE, together with MafK. The binding of MATIIα and MATIIβ to the promoter region suggests that they might also interact with the basal transcription machinery. This possibility was supported by the finding that the purified MATIIα complex interacted with the basal transcriptional machinery (9).

FIGURE 4.

MATII recruitment to the COX-2 locus. A, a schematic representation of mouse COX-2 locus. Lines below indicate PCR primer pairs for ChIP analysis. B–D, ChIP assays were performed using anti-MATIIα (B), MATIIβ (C), and MafK (D) antibodies for extracts from iMEFs. The relative levels of enrichment of the indicated genomic DNA regions are shown as in Fig. 3C.

Modification of H3K9 and H3K4 at the COX-2 Locus

The recruitment of MATIIα to the COX-2 gene locus suggested that MATIIα might affect the methylation of histones around the locus. To investigate this possibility, we examined the levels of trimethylation at the COX-2 locus in iMEFs treated with control or MATIIα siRNA (Fig. 5). Trimethylation of histone H3K9 was clearly observed at the COX-2 locus in control cells (Fig. 5, A–C). This modification was higher in the 3 kb upstream region than in the other two regions. This finding is in accord with observations made by Zhu et al. (13) showing that H3K9 trimethylation-rich regions flank enhancers of inactive genes. Upon MATIIα KD, the trimethylation of histone H3K9 was decreased in these regions (Fig. 5, D–F). These observations suggest that MATIIα is required for the maintenance of H3K9 trimethylation around not only the MARE and promoter regions where it was recruited but also the upstream region of the COX-2 locus where its recruitment was not apparent.

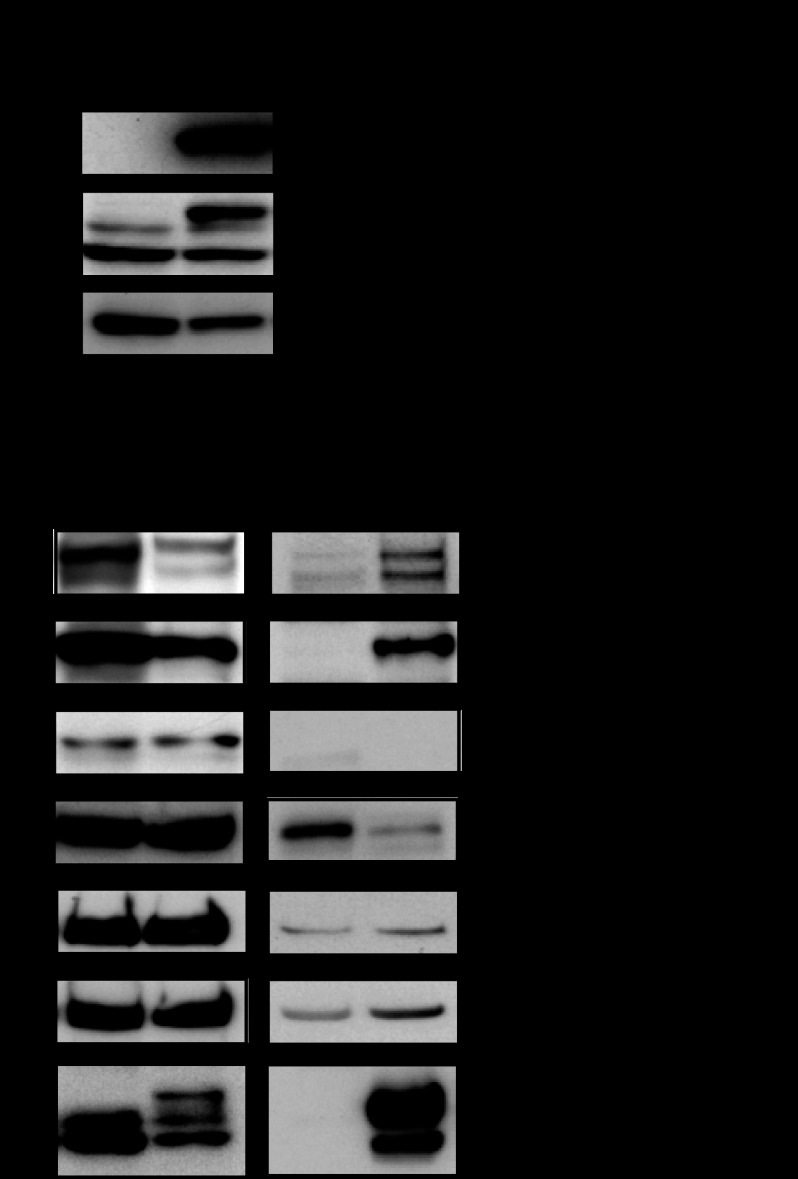

FIGURE 5.

Histone modification at the COX-2 locus in MATIIα KD iMEFs. A–C, the relative levels of histone H3K9 trimethylation (me3) at the MARE (A), promoter (B), and 3 kbp upstream of the MARE (C) regions of the COX-2 locus in iMEFs treated with control (black) or MATIIα siRNA (gray). These results represent the means of three independent experiments with S.D. p values (Student's t test) for differences between cells treated with control and MATIIα siRNA are indicated. D–F, the relative levels of histone H3K4me3 at the indicated regions were compared as in A–C. G, histone H3K9 and K27 acetylation at the indicated regions of the COX-2 locus were compared in iMEFs treated with control (black) or MATIIα siRNA (gray). The relative levels of enrichment of the indicated genomic DNA regions are shown as in Fig. 2C. p values (Student's t test) for differences between cells treated with control and MATIIα siRNA are indicated.

We observed higher levels of trimethylation of H3K4 at the MARE and promoter regions than in the upstream region (Fig. 5, D–F). The depletion of MATIIα tended to affect the levels of this modification in the MARE and upstream regions, but the effects were not statistically significant (Fig. 5, D–F). It is worth noting that the trimethylation of H3K4 at the promoter remained high upon MATIIα KD. Taken together, these results suggest that MATIIα is required for H3K9 trimethylation but is dispensable for H3K4 trimethylation for the regulation of the COX-2 locus.

To investigate whether the histone acetylation, which is known to correlate with gene activation (11), was affected, we examined H3K9 and K27 acetylation levels at the COX-2 locus in iMEFs treated with control or MATIIα siRNA (Fig. 5G). Upon MATIIα KD, the levels of the H3K9 acetylation were increased at the promoter region but not at the upstream region (Fig. 5G). K27 acetylation also tended to be increased at the promoter region but it did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 5G). These observations suggest that MATIIα is involved in deacetylation of histone H3K9 at the COX-2 promoter.

Impact on Modification of H3K9 and H3K4 of MATIIα

The region- and modification-specific effects of MATIIα KD suggest that histone methylation might not necessarily be dependent on MATIIα. An immunoblotting analysis of the chromatin isolated from the control and MATIIα KD iMEF cells revealed that the trimethylation of histones H3K9 and H3K4 was both decreased, whereas the mono- and dimethylation of these residues were not affected by MATIIα KD (Fig. 6). The incorporation of histones into the nucleosome was not grossly affected by MATIIα KD (Fig. 6). These results suggest that, in contrast to the COX-2 locus, the trimethylation of H3K9 and K4 at the epigenome-wide level was dependent on MATIIα. These results suggest that MATII may contribute to histone methylation in at least two distinct mechanisms. MATII is locally and globally required for trimethylation of H3K9. In contrast, it is required for trimethylation of H3K4 in general but is dispensable for this modification at specific epigenome regions.

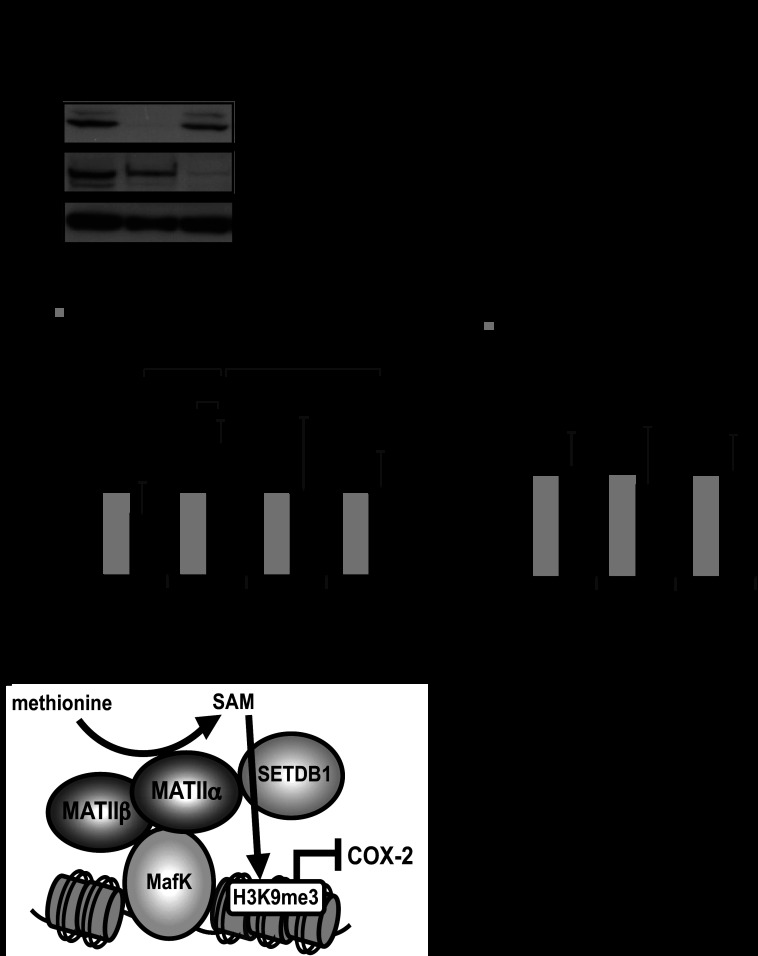

FIGURE 6.

The levels of methylation of histones H3K9 and H3K4 in iMEFs treated with control or MATIIα siRNA (upper panels). Gels were stained by Coomassie Brilliant Blue (CBB) staining (bottom).

Association of H3K9 Methyltransferases with MATIIα

One model of these pathways, based on the above observations, would be that among the many histone methyltransferases, some of the H3K9 methyltransferases might be highly dependent upon MATIIα. Considering that such histone methylatransferases may interact with MATIIα, we tried to identify the putative specific histone H3K9 trimethyltransferases associated with MATIIα. We first generated iMEFs stably co-expressing FLBio-MATIIα (tagged with FLAG and biotinylation sequences) and biotin ligase BirA (Fig. 7A). Biotinylated MATIIα was purified from the nuclear extracts by avidin affinity chromatography. As a control, we performed a mock purification from cells expressing only BirA (Fig. 7A, left lane). Using the immunoblotting analyses, we found that MATIIα associated with SETDB1 and Suv39h1, both of which are able to catalyze histone H3K9 trimethylation. These interactions appeared to be specific because MATIIα did not interact with RIZ1, another enzyme involved in H3K9 trimethylation, or Ash1 H3K4 methyltransferase in iMEFs (Fig. 7B).

FIGURE 7.

SETDB1 interacts with MATIIα. A, immunoblot (IB) analysis of whole extract samples from iMEFs stably expressing FLBio-MATIIα and BirA. FLBio-MATIIα was also detected with the biotin-avidin complex (ABC) assay. Cells expressing only BirA were used as a control. B, immunoblot (IB) analysis of the affinity-purified samples using the indicated antibodies.

Regulation of the COX-2 Locus by SETDB1 and MATIIα

We next examined the involvement of SETDB1 and Suv39h1 in the regulation of COX-2. SETDB1 was efficiently reduced in iMEFs; however, the Suv39h1 silencing was not successful (Fig. 8A, data not shown). The levels of COX-2 mRNA were elevated by the SETDB1 KD in comparison with the control cells (Fig. 8B). In ChIP assays, SETDB1 was recruited to the MARE region but not to the 3 kb upstream or promoter regions (Fig. 8C). As a negative control for SETDB1 binding, we examined the 34th exon at the collagen type XI α2 (Col11a2) gene, which was used as a negative control for SETDB1 binding in a previous report (25) and confirmed that SETDB1 was not recruited to this region. In contrast to SETDB1, we could not detect binding of Suv39h1 to the COX-2 locus (Fig. 8D). Based on these results, we concluded that the expression of COX-2 was repressed by MATIIα and SETDB1 in iMEFs (Fig. 8E). These results do not exclude the possible involvement of histone methyltransferases other than SETDB1.

FIGURE 8.

MATIIα and SETDB1 regulate COX-2 gene expression. A, effects of siRNA on the expression levels of SETDB1 and MATIIα in iMEFs. B, qPCR analysis of COX-2 gene expression. The averages of three independent experiments with standard deviations are shown. p values (Student's t test) for differences between the control and SETDB1 KD are indicated. C and D, ChIP assays were performed using an anti-SETDB1 and Suv39h1 antibody with chromatin from iMEFs. The relative levels of enrichment of the indicated genomic DNA regions are shown with S.D. p values (Student's t test) for differences between the pairs of antibodies are indicated. E, a model for the function of MATII-SETDB1 in the regulation of COX-2 gene expression. IB, immunoblot.

DISCUSSION

The AdoMet-integrating transcription regulation module, which is constituted by MATIIα and -β in the nucleus, has been proposed to couple histone methylation and transcriptional regulation by forming a complex that contain DNA binding transcription factors Bach1 and MafK, and histone methyltransferase(s) (9). However, other target genes for this system other than HO-1 are not known. Although the catalytic activity for the AdoMet synthesis of MATIIα is required for the repression of HO-1 gene (9), the identity of methyltransferase(s) interacting with MATIIα has been unknown. We have attempted to address these issues in this study, identifying COX-2 and SETDB1 as new components of this system, leading us to suggest a model depicted in Fig. 8E. In this model, AdoMet synthesis and histone methylation are coupled on chromatin by a physical (direct or indirect) interaction with MATIIα and SETDB1 on the subset of MafK target genes.

However, there are several issues that still need to be resolved in further studies. First, while this model explains the gene-specific role of MATIIα, our results also indicated that MATIIα was involved in the trimethylation of both H3K9 and K4 when viewed on a larger, epigenome-wide scale (Fig. 6). Such an epigenome-wide function of MATIIα may not be dependent on the local recruitment of this enzyme. In this mode of action, MATIIα may simply supply nuclear AdoMet without interacting with the chromatin and/or methyltransferases. For example, MATII may be involved in the methylation of newly biosynthesized, non-chromosomal histones. This is suggested by the finding that SETDB1 catalyzes the methylation of non-chromosomal histone H3K9 prior to its incorporation into chromatin in the S phase (26). It will be important to examine whether the nuclear localization of MATIIα (9) is required for this epigenome-wide function. Second, the physical interaction of MATIIα with transcription factors and methyltransferases may not be restricted to transcriptional repression. The expression of a substantial number of genes was reduced upon MATIIα KD (Fig. 1C). Consistent with this idea, we recently found that MATIIα interacted with transcription activators (9). Recently, it has been reported that the chromatin regulators partition into six modules correlated with binding patterns. One of the six modules, which include SETDB1, co-localizes with not only repressed genes but also active and competent promoters (27). MATIIα may be involved in this regulation. Third, it may be surprising that a limited knockdown of only ∼70% of Mat2a mRNA was sufficient to cause the dramatic increase in COX-2 expression in iMEFs. This observation suggests that MATIIα is rate-limiting in cells and is consistent with previous reports showing signal-responsive induction of MATIIα expression (28–30). Mutation of MATIIα may show haploinsufficiency. Knockdown of Mat2a (MAT2A) mRNA in several cell lines resulted in up-regulation of COX-2 (Figs. 1 and 2). Therefore, the involvement of MATIIα in the repression of COX-2 is not restricted to particular types of cells. Furthermore, although SETDB1 was recruited to the COX-2 locus (Fig. 8C), the enrichment was only 1.5-fold. It remains unclear whether this level of differential binding would account for the H3K9 methylation at the COX-2 locus. One possibility is that, if there is any cooperative function between SETDB1 and other methylation-related factors, a small increase in SETDB1 binding would result in higher levels of methylation than expected. Indeed, a cooperative function of SETDB1, Suv39h1, G9a, and G9a related protein has been reported (31). Of course, cooperativity between SETDB1 and MATIIα may explain the differential H3 methylation. Alternatively, SETDB1 may be redundant with other methyltransferases. Suv39h1 was apparently not recruited to this locus (Fig. 8D). However, epitope availability on this locus may be the cause of this observation. It still remains possible that methyltransferase(s) other than SETDB1, including Suv39h1, is involved in the MATIIα-dependent COX-2 repression.

Upon MATIIα knockdown, we found that H3K9 acetylation was increased at the COX-2 promoter region. There are several possibilities to explain these observations. First, the reduction in the H3K9 trimethylation would allow acetylation at the same residue by histone acetyltransferases. Second, because MATIIα complex includes histone deacetylase-1 (9), its recruitment to the locus would be decreased by MATIIα knockdown, leading to an increase in the acetylation level. histone acetyltransferases contain a large number of members such as p300/CBP and GCN5/PCAF (32, 33). GCN5/PCAF may be involved in the expression of the COX-2 gene because it has been reported that they catalyze H3K9 acetylation in MEFs (33).

Our present and previous observations suggest that there is a coupling of AdoMet synthesis and histone methylation within nuclei, which may confer several advantages. First, the local synthesis for local consumption of AdoMet may ensure effective utilization of limited resources, because it would be possible to lower the overall AdoMet levels and to maintain locally sufficient levels of the substrate for methylation reactions. In addition, this could help avoid the putative genotoxic effect of AdoMet (34). H3K4 trimethylation was less dependent on MATIIα compared with H3K9 trimethylation at the COX-2 locus (Fig. 5), raising the possibility that there may be a subset of histone methyltransferases, which are less dependent on MATIIα. Such enzymes may possess higher affinity for AdoMet. Second, the association and dissociation of MATIIα with histone methyltransferases may provide a mechanism for dynamic regulation of histone methylation. To further explore these interesting possibilities, it will be important to understand how the nuclear accumulation of MATIIα and its interaction with other nuclear/chromatin proteins are regulated.

COX-2 catalyzes biosynthesis of prostaglandin G2 and prostaglandin H2 in the arachidonic acid cascade (14). COX-2 also contributes to tumorigenesis (15, 35). Taking together these previous and current observations, MATII may play an important regulatory role in inflammation and tumorigenesis. Indeed, its connections with diseases have been reported in several model systems (36–38).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. H. Motohashi (Tohoku University) for critical reading of the manuscript and comments and Drs. A. Muto, M. Morita, and K. Ota (Tohoku University) for discussion and help with the study.

This work was supported by grants-in-aid from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, and Culture of Japan, and the global COE (Center of Excellence) program for Network Medicine, Tohoku University. This work was also supported in part by the Biomedical Research Core of Tohoku University School of Medicine.

- MAT

- methionine adenosyltransferase

- MATII

- methionine adenosyltransferase II

- AdoMet

- S-adenosylmethionine

- COX-2

- cyclooxygenase-2

- iMEF

- immortalized mouse embryonic fibroblast

- qPCR

- quantitative PCR

- KD

- knockdown

- MARE

- Maf recognition element.

REFERENCES

- 1. Kotb M., Mudd S. H., Mato J. M., Geller A. M., Kredich N. M., Chou J. Y., Cantoni G. L. (1997) Consensus nomenclature for the mammalian methionine adenosyltransferase genes and gene products. Trends. Genet. 13, 51–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fowler B. (2005) Homocystein: overview of biochemistry, molecular biology, and role in disease process. Semin. Vasc. Med. 5, 77–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cantoni G. L. (1975) Biological methylation: selected aspects. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 44, 435–451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Markham G. D., Pajares M. A. (2009) Structure-function relationships in methionine adenosyltransferases. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 66, 636–648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Halim A. B., LeGros L., Geller A., Kotb M. (1999) Expression and functional interaction of the catalytic and regulatory subunits of human methionine adenosyltransferase in mammal cells. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 29720–29725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. LeGros H. L., Jr., Halim A. B., Geller A. M., Kotb M. (2000) Cloning, expression, and functional characterization of the β regulatory subunit of human methionine adenosyltransferase (MAT II). J. Biol. Chem. 275, 2359–2366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Oyake T., Itoh K., Motohashi H., Hayashi N., Hoshino H., Nishizawa M., Yamamoto M., Igarashi K. (1996) Bach proteins belong to a novel family of BTB-basic leucine zipper transcription factors that interact with MafK and regulate transcription through the NF-E2 site. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16, 6083–6095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sun J., Hoshino H., Takaku K., Nakajima O., Muto A., Suzuki H., Tashiro S., Takahashi S., Shibahara S., Alam J., Taketo M. M., Yamamoto M., Igarashi K. (2002) Hemoprotein Bach1 regulates enhancer availability of heme oxygenase-1 gene. EMBO J. 21, 5216–5224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Katoh Y., Ikura T., Hoshikawa Y., Tashiro S., Ito T., Ohta M., Kera Y., Noda T., Igarashi K. (2011) Methionine adenosyltransferase II serves as a transcriptional corepressor of Maf oncoprotein. Mol. Cell 41, 554–566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Igarashi K., Sun J. (2006) The heme-Bach1 pathway in the regulation of oxidative stress response and erythroid differentiation. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 8, 107–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Li B., Carey M., Workman J. L. (2007) The role of chromatin during transcription. Cell 4, 653–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Martin C., Zhang Y. (2005) The diverse functions of histone lysine methylation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 838–849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhu Y., van Essen D., Saccani S. (2012) Cell-type-specific control of enhancer activity by H3K9 trimethylation. Mol. Cell 46, 408–423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Smith W. L., Garavito R. M., DeWitt D. L. (1996) Prostaglandin endoperoxide H synthases (cyclooxigenases)-1 and 2. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 33157–33160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tsujii M., Kawano S., Tsuji S., Sawaoka H., Hori M., DuBois R.N. (1998) Cyclooxygenase regulates angiogenesis induced by colon cancer cells. Cell 93, 705–716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Harper K. A., Tyson-Capper A. J. (2008) Complexity of COX-2 gene regulation. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 36, 543–545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Todaro G. J., Green H. (1963) Quantitative studies of the growth of mouse embryo cells in culture and their development into established lines. J. Cell Biol. 17, 299–313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tsuchiya S., Yamabe M., Yamaguchi Y., Kobayashi Y., Konno T., Tada K. (1980) Establishment and characterization of a human acute monocytic leukemia cell line (THP-1). Int. J. Cancer 26, 171–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Popovich D. G., Kitts D. D. (2002) Structure-function relationship exists for ginsenosides in reducing cell proliferation and inducing apoptosis in the human leukemia (THP-1) cell line. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 406, 1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kim J., Cantor A. B., Orkin S. H., Wang J. (2009) Use of in vivo biotinylation to study protein- protein and protein-DNA interactions in mouse embryonic stem cells. Nat. Protoc. 4, 506–517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Andrews N. C., Faller D.V. (1991) A rapid micro preparation technique for extraction of DNA-binding proteins from limiting numbers of mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 19, 2499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tachibana M., Matsumura Y., Fukuda M., Kimura H., Shinkai Y. (2008) G9a/GLP complexes independently mediate H3K9 and DNA methylation to silence transcription. EMBO J. 27, 2681–2690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dohi Y., Ikura T., Hoshikawa Y., Katoh Y., Ota K., Nakanome A., Muto A., Omura S., Ohta T., Ito A., Yoshida M., Noda T., Igarashi K. (2008) Bach1 inhibits oxidative stress-induced cellular senescence by impeding p53 function on chromatin. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 15, 1246–1254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zeng P. Y., Vakoc C. R., Chen Z. C., Blobel G. A., Berger S. L. (2006) In vivo dual cross-linking for identification of indirect DNA-associated proteins by chromatin immunoprecipitation. BioTechniques 41, 694 696 698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ayyanathan K., Lechner M. S., Bell P., Maul G. G., Schultz D. C., Yamada Y., Tanaka K., Torigoe K., Rauscher F. J., 3rd (2003) Regulated recruitment of HP1 to a euchromatic gene induces mitotically heritable, epigenetic gene silencing: a mammalian cell culture model of gene variegation. Genes Dev. 17, 1855–1869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Loyola A., Tagami H., Bonaldi T., Roche D., Quivy J. P., Imhof A., Nakatani Y., Dent S. Y., Almouzni G. (2009) The HP1α-CAF1-SetDB1-containing complex provides H3K9me1 for Suv39-mediated K9me3 in pericentric heterochromatin. EMBO Rep. 10, 769–775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ram O., Goren A., Amit I., Shoresh N., Yosef N., Ernst J., Kellis M., Gymrek M., Issner R., Coyne M., Durham T., Zhang X., Donaghey J., Epstein C. B., Regev A., Bernstein B. E. (2011) Combinatorial patterning of chromatin regulators uncovered by genome-wide location analysis in human cells. Cell 147, 1628–1639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Halim A. B., LeGros L., Chamberlin M. E., Geller A., Kotb M. (2001) Regulation of the human MAT2A gene encoding the catalytic α 2 subunit of methionine adenosyltransferase, MAT II: gene organization, promoter characterization, and identification of a site in the proximal promoter that is essential for its activity. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 9784–9791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yang H., Li T. W., Peng J., Mato J. M., Lu S. C. (2011) Insulin-like growth factor 1 activates methionine adenosyltransferase 2A transcription by multiple pathways in human colon cancer cells. Biochem. J. 436, 507–516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rodríguez J. L., Boukaba A., Sandoval J., Georgieva E. I., Latasa M. U., García-Trevijano E. R., Serviddio G., Nakamura T., Avila M. A., Sastre J., Torres L., Mato J. M., López-Rodas G. (2007) Transcription of the MAT2A gene, coding for methionine adenosyltransferase, is up-regulated by E2F and Sp1 at a chromatin level during proliferation of liver cells. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 39, 842–850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fritsch L., Robin P., Mathieu J. R., Souidi M., Hinaux H., Rougeulle C., Harel-Bellan A., Ameyar-Zazoua M., Ait-Si-Ali S. (2010) A subset of the histone H3 lysine 9 methyltransferases Suv39h1, G9a, GLP, and SETDB1 participate in a multimeric complex. Mol. Cell 37, 46–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Verdone L., Agricola E., Caserta M., Di Mauro E. (2006) Histone acetylation in gene regulation. Brief. Funct. Genomic, Proteomic. 5, 209–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jin Q., Yu L. R., Wang L., Zhang Z., Kasper L. H., Lee J. E., Wang C., Brindle P. K., Dent S. Y., Ge K. (2011) Distinct roles of GCN5/PCAF-mediated H3K9ac and CBP/p300-mediated H3K18/27ac in nuclear receptor transactivation. EMBO J. 30, 249–262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sedgwick B., Bates P. A., Paik J., Jacobs S. C., Lindahl T. (2007) Repair of alkylated DNA: recent advances. DNA Repair 6, 429–442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sherratt P. J., McLellan L. I., Hayes J. D. (2003) Positive and negative regulation of prostaglandin E2 biosynthesis in human colorectal carcinoma cells by cancer chemopreventive agents. Biochem. Pharmacol., 66, 51–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cai J., Mao Z., Hwang J. J., Lu S. C. (1998) Differential expression of methionine adenosyltransferase genes influences the rate of growth of human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 58, 1444–1450 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jani T. S., Gobejishvili L., Hote P. T., Barve A. S., Joshi-Barve S., Kharebava G., Suttles J., Chen T., McClain C. J., Barve S. (2009) Inhibition of methionine adenosyltransferase II induces FasL expression, Fas-DISC formation and caspase-8-dependent apoptotic death in T leukemic cells. Cell Res. 19, 358–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zhang T., Zheng Z., Liu Y., Zhang J., Zhao Y., Liu Y., Zhu H., Zhao G., Liang J., Li Q., Xu H. (2013) Overexpression of methionine adenosyltransferase II α (MAT2A) in gastric cancer and induction of cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in SGC-7901 cells by shRNA-mediated silencing of MAT2A gene. Acta Histochem. 115, 48–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]