Background: MicroRNA (miR) dysregulation is found in Alzheimer disease (AD). A disintegrin and metalloprotease 10 (ADAM10) prevents generation of amyloid β (Aβ) and decrease AD pathology.

Results: miR-144 suppresses ADAM10 expression and is up-regulated by activator protein-1.

Conclusion: miR-144 is a negative regulator of ADAM10 and may be involved in AD pathogenesis.

Significance: The first work to demonstrate the function of miRNA-144 and its regulation in the pathogenesis of AD.

Keywords: ADAM ADAMTS, Alzheimers Disease, Amyloid, Gene Regulation, MicroRNA, ADAM10, miR-144

Abstract

Amyloid β-peptide (Aβ) accumulating in the brain of Alzheimer disease (AD) patients is believed to be the main pathophysiologcal cause of the disease. Proteolytic processing of the amyloid precursor protein by α-secretase ADAM10 (a disintegrin and metalloprotease 10) protects the brain from the production of the Aβ. Meanwhile, dysregulation or aberrant expression of microRNAs (miRNAs) has been widely documented in AD patients. In this study, we demonstrated that overexpression of miR-144, which was previously reported to be increased in elderly primate brains and AD patients, significantly decreased activity of the luciferase reporter containing the ADAM10 3′-untranslated region (3′-UTR) and suppressed the ADAM10 protein level, whereas the miR-144 inhibitor led to an increase of the luciferase activity. The negative regulation caused by miR-144 was strictly dependent on the binding of the miRNA to its recognition element in the ADAM10 3′-UTR. Moreover, we also showed that activator protein-1 regulates the transcription of miR-144 and the up-regulation of miR-144 at least partially induces the suppression of the ADAM10 protein in the presence of Aβ. In addition, we found that miR-451, a miRNA processed from a single gene locus with miR-144, is also involved in the regulation of ADAM10 expression. Taken together, our data therefore demonstrate miR-144/451 is a negative regulator of the ADAM10 protein and suggest a mechanistic role for miR-144/451 in AD pathogenesis.

Introduction

Alzheimer disease (AD)2 is a neurodegenerative disease that accounts for 50 to 60% of dementia cases in the elderly (1). The amyloid β-peptide (Aβ) is believed to be the essential cause of AD pathology and is produced by sequential proteolytic cleavages of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) by β- and γ-secretases (2). APP is also processed in a non-amyloidogenic pathway by α-secretase, thereby repressing Aβ formation (3). This alternative processing of APP by α-secretase generates the neuroprotective and neurotrophic soluble APPsα ectodomain (4). ADAM10, whose level is decreased in the platelets and neurons of AD patients (5, 6), is the most recognized candidate for α-secretase in cell culture and mouse models (7–9). Additionally, APPsα is also decreased in the cerebrospinal fluid of AD patients (10, 11), indicating a reduced amount and/or activity of ADAM10. A previous study demonstrates that neuronal overexpression of ADAM10 in APP transgenic mice significantly decreases Aβ generation, amyloid plaque load, and AD pathology, whereas overexpression of a dominant-negative ADAM10 variant enhances Aβ formation (3). These reports shed light on the important role of ADAM10 in Aβ production and the pathogenesis of AD. Thus, studying the regulation of ADAM10 expression may help to delineate the underlying pathophysiology of AD and offer new therapeutic targets for the disease.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs or miRs) are small (∼22 nucleotides) non-coding RNAs (12). In animals, miRNAs regulate gene expression at the post-transcriptional level by leading to target mRNA degradation or repressing protein translation (12, 13). miRNAs play very important roles in many aspects of neuronal function and in a variety of physiological processes in the central nervous system (CNS) (14). For instance, miRNAs are implicated in neurite outgrowth (15, 16), regulate dendritic spine development (17), promote neurogenesis in the midbrain-hindbrain domain (18), and control human neuronal differentiation (19). Overexpression of a single miRNA can even shift the overall gene expression profile of a cell from non-neuronal to neuronal (20). Similarly, alterations of miRNA networks cause neurodegenerative disorders, including AD, Parkinson disease (21), and Huntington disease (22). Indeed, recent studies demonstrate that dysregulation of specific miRNAs contributes to amyloidogenesis in the pathogenesis of AD, but all such research has focused on the regulation of APP (23–27) or BACE1 (i.e. β-secretase and β-site APP cleaving enzyme 1) (28–30).

In this study, we used a combination of bioinformatics and experimental techniques to demonstrate that miR-144 is a negative regulator of ADAM10, and activator protein-1 (AP-1), which can be activated by Aβ and is implicated in AD pathogenesis, is involved in the regulation of miR-144 expression. In the presence of Aβ, miR-144 is up-regulated and contributes to ADAM10 down-regulation caused by Aβ. Thus, this study presents a mechanism for the ADAM10 protein repression observed in AD patients and provides potential therapeutic targets for the prevention and/or treatment of the disease.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Bioinformatics

Prediction of miRNA targets was conducted using miRanda. Prediction of the transcriptional start sites (TSSs) of primary microRNAs was performed using miRStart. The putative promoter sequences of primary microRNAs and the 3′-UTR of ADAM10 were retrieved from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). Prediction of transcription factors for primary microRNAs was conducted using the Transcription Element Search System. Sequence conservation was analyzed with the Evolutionary Conserved Region Browser.

Cell Culture and Reagents

HeLa and human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells were cultured in DMEM (Hyclone) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone), 100 units/ml of penicillin, and 100 μg/ml of streptomycin at 37 °C and 5% CO2. 12-O-Tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA) was obtained from Sigma. Human Aβ42 peptide was obtained from AnaSpec and Sigma. miRNA mimics, inhibitors, and the corresponding negative controls were obtained from RiboBio.

Luciferase Reporter Gene Constructs

To construct the reporter plasmid pmirGLO-ADAM10 3′-UTR, the 3′-UTR region of ADAM10 was amplified from human cDNA. The PCR product was digested with SacI and XhoI. Then the fragment, which spans 1267 bp starting from the 35th bp upstream of the stop codon, was cloned into the pmirGLO Dual Luciferase miRNA Target Expression Vector (Promega). To construct the luciferase reporter plasmids pGL3-promoter-2808, promoter-2554, promoter-1895, promoter-1019, promoter-453, and promoter-307, each promoter region of miR-144 was amplified from human genomic DNA and subsequently cloned into the KpnI and XhoI sites of the pGL3-basic plasmid (Promega). The transcription factor overexpression constructs were amplified from human cDNA and then cloned into pcDNA3.1/myc-His A at the KpnI and XhoI or BamHI and XbaI sites. The ADAM10 3′-UTR luciferase mutant construct that lacks the putative miR-144 MRE, the ADAM10 3′-UTR luciferase mutant construct that lacks the putative miR-451 MRE, and the miR-144 promoter reporter plasmids containing single or double site-specific deletion for each transcription factor AP-1 binding site were generated by using a PCR-mediated deletion mutagenesis protocol (31). The sequences of primers used in the aforementioned construction or mutation are listed in Table 1. All constructs and mutants were verified by sequencing at Invitrogen.

TABLE 1.

Sequences of primers used in plasmids construction or mutantion (F, forward; R, reverse; Mut, mutant)

| Primer | Sequence 5′ → 3′ |

|---|---|

| ADAM10 3′-UTR F | ATAGAGCTCCCCGAGAGAGTTATCAAATGGG |

| ADAM10 3′-UTR R | CGCCTCGAGAAATGCCAATTATTTACATCTG |

| pGL3-promoter-2808 F | GCGGTACCACCATGCCTGGGCTCTCACTCA |

| pGL3-promoter-2554 F | GCGGTACCTGAGGAAACTGTGAGTGGGAACA |

| pGL3-promoter-1895 F | GCGGTACCGAGGCAGGAGAATCGCTTGAA |

| pGL3-promoter-1019 F | GCGGTACCCAGAGGCAAAGAACCAAAC |

| pGL3-promoter-453 F | GCGGTACCGCAGGGCAAGGGTTAAGAGGC |

| pGL3-promoter-307 F | ATAGGTACCGCACCTTCTCTGGGTCTGTCTGCC |

| pGL3-promoter R | GCGCTCGAGACAGGACAGGTCAGGGCTGGA |

| ADAM10 3′-UTR 144Mut F | CCTGAGTATGTCAATTATTTTAATTAAGAGCGGAAAAATTTTATAATACAAAGAAAC |

| ADAM10 3′-UTR 144Mut R | TTTTTCCGCTCTTAATTAAAATAATTGACATACTCAGGATAACAGAGAATGG |

| ADAM10 3′-UTR 451Mut F | AGTGATGATATGCTGAAAAGACACAGCTTTTCTTTTCCATATCAGACAGAAAAC |

| ADAM10 3′-UTR 451Mut R | GGAAAAGAAAAGCTGTGTCTTTTCAGCATATCATCACTGATCATTGGTAACC |

| AP-1 F | ATAGGTACCGGGGGGCGCGGGTGTCC |

| AP-1 R | ATACTCGAGTTGCAACTGCTGCGTTAGCATGAGTTGGC |

| CREB F | ATTGGATCCACATGACCATGGAATCTGG |

| CREB R | GCCTCTAGAATCTGATTTGTGGCAGTAAAG |

| SP-1 F | TAAGGTACCGAATGGATGAAATGACAGCTGTGG |

| SP-1 R | ATTCTCGAGGAAGCCATTGCCAC |

| TCF-4 F | ATGGTACCGAATGCATCACCAACAGC |

| TCF-4 R | ACACTCGAGCATCTGTCCCATGTG |

| CP2 F | ATTGGTACCGAATGGCCTGGGC |

| CP2 R | TAACTCGAGCTTCAGTATGATATGATAGCTATCATTG |

| AP-1 Mut-1 F | AATAGAAATTTAGGCGGTAGGGTGAGCTCGGCTGCCAGACAG |

| AP-1 Mut-1 R | AGCCGAGCTCACCCTACCGCCTAAATTTCTATTCCCAGCCCCTGCCCC |

| AP-1 Mut-2 F | AAACCTTCCACTAGGGATCCAGCAATTAAATGCTGGTGGATGGG |

| AP-1 Mut-2 R | ATCCACCAGCATTTAATTGCTGGATCCCTAGTGGAAGGTTTCTCGTTTTTGC |

| AP-1 Mut-3 F | TTCTAGGGAAAGGGGCCAGTGGACTCTAGCAGGGCAAGGGTTAAGAGGCAGGGCCAGG |

| AP-1 Mut-3 R | TTGCCCTGCTAGAGTCCACTGGCCCCTTTCCCTAGAAGGCCTTTTCTCACATACTCTCTCATGGACC |

| AP-1 Mut-4 F | TGCCTGTCTGCTTGTTAGTGACCTTCTGCATCATTACGCCATCTCTGGCTTGTTTAACACTGGCCC |

| AP-1 Mut-4 R | ATGGCGTAATGATGCAGAAGGTCACTAACAAGCAGACAGGCAGACAGACCCAGAGAAGGTGC |

| AP-1 Mut-5 F | ATAACCCACCTGGGCTGTGCCCACAGAATCAAGGAGACGCTGGCCTGCGAGGG |

| AP-1 Mut-5 R | AGCGTCTCCTTGATTCTGTGGGCACAGCCCAGGTGGGTTATGGGAAGGGG |

| AP-1 Mut-6 F | TGTGTGTGTCCAGCCCCTGTCCTGTTCTGCCCCCAGCCCCTCACAGATGC |

| AP-1 Mut-6 R | TGGGGGCAGAACAGGACAGGGGCTGGACACACACAGCTTCCTGCTCCCTGCTCTACAGC |

Reporter Plasmid Transfection and Luciferase Assay

Transient transfections of HeLa cells were performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. For the luciferase assay, cells were plated at a density of 2 × 105 cells/well in 24-well plates and co-transfected after 24 h with 0.2 μg of pGL3 reporter plasmid and 0.002 μg of Renilla plasmid (Promega) or 0.1 μg of pmirGLO reporter plasmid (Promega), as well as 50 nm miRNA mimics or 100 nm inhibitors per well. Luciferase activities were measured 48 h after transfection using the Dual Luciferase reporter assay system (Promega) and a GloMaxTM 96 Microplate Luminometer (Promega). Transient transfections of SH-SY5Y cells were performed using an Amaxa Cell Line Nucleofector Kit V (Lonza) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

RNA Extraction and Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNAs were extracted with TRIzol (Invitrogen), and the first-strand cDNAs were synthesized using the GoScriptTM Reverse Transcription System (Promega) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The quantitative RT-PCR analysis was performed with SYBR® Green Real-time PCR Master Mix (TOYOBO) using the CFX96 Real-time System (Bio-Rad). The primers used for quantitative RT-PCR are as follows: ADAM10 forward, 5′-TCGAACCATCACCCTGCAACCT-3′ and reverse, 5′-GCCCACCAATGAGCCACAATCC-3′; and β-actin forward, 5′-GTCACCAACTGGGACGACATG-3′ and reverse, 5′-GATAGCACAGCCTGGATAGCAAC-3′. β-Actin served as an internal control. miRNAs were extracted using an miRcute miRNA isolation kit (TIANGEN). Extracted miRNAs were polyadenylated by poly(A) polymerase and reverse transcribed into cDNA using oligo(dT) primers with an miRcute miRNA first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (TIANGEN) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis for mature miR-144 was performed with an miRcute miRNA quantitative PCR detection kit (TIANGEN) using the primers miR-144 forward, 5′-GGGGGGGGGGGGGTACAGTATAGATGATGTACTAA-3′; miR-451 forward, 5′-GGGGGGGGCCAAACCGTTACCATTACTGAGTTAAAA-3′; and U6 forward, 5′-GCAAGGATGACACGCAAATTCGT-3′. The reverse primer for the quantitative RT-PCR was provided in the miRcute miRNA quantitative PCR detection kit. U6 served as an internal control.

Protein Extraction and Western Blot Analysis

Cells were lysed in RIPA buffer (Biosure) supplemented with a protease inhibitor mixture and 1 mm PMSF (Biosure). The protein concentration was measured using a BCA protein assay kit (Pierce). Protein samples were separated by 10–15% SDS-PAGE (Bio-Rad) and electroblotted onto nitrocellulose membranes (Hybond-ECL, GE Healthcare). The membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk in PBST for 2 h at room temperature and incubated overnight at 4 °C with anti-ADAM10 (1:200, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-APP C-terminal (1:4000, Sigma), or anti-GAPDH (1:2000, CWBIO). Then, they were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies: goat anti-mouse IgG (1:10,000, ZSGB-BIO) or goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:10,000, ZSGB-BIO). Western blot immunoreactivity was detected using a Super Signal West Pico Kit (Pierce).

Small RNA Interference (siRNA)

siRNA duplexes consisting of 21 bp of oligonucleotides were purchased from GenePharma. The sequences of siRNA duplexes for c-Jun and negative control (scrambled) were as follows: c-Jun siRNA-1 targeting 5′-GAUGGAAACGACCUUCUAUTT-3′, c-Jun siRNA-2 targeting 5′-CCUCAGCAACUUCAACCCATT-3′, and scrambled siRNA targeting 5′-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT-3′. Transfection of siRNA duplexes at a concentration of 75 pmol/well for 6-well plates was performed using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX Reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instruction.

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA)

Nuclear proteins from SH-SY5Y cells were extracted by NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagents (Pierce). The following biotin-labeled probes and unlabeled competitor probes with the same sequences as well as their antisense oligos were synthesized at Invitrogen and annealed: 5′-CTTCTAGGGAAAGGGGCCAGTGACCCTTGTCATGGACTCTAGCAGGGC-3′, corresponding to AP-1 binding site 3 of the miR-144 promoter; 5′-CCATAACCCACCTGGGCTGTGCCTGACCACAGAATCAAGGAGACGCTG-3′, corresponding to AP-1 binding site 5 of the miR-144 promoter. EMSA reactions (20 μl) were assembled using the LightShift Chemiluminescent EMSA Kit (Pierce), and the reaction contained 50 fmol of biotin-labeled probe, 2 μl of 10× binding buffer, 1 μl of 1 μg/μl of poly(dI·dC), 0.5 μl of 50% glycerol, and/or 2 μl of NE-PER nuclear extracts, 10 pmol of unlabeled probe. Mixtures of protein and DNA were incubated for 20 min at room temperature. Following addition of 5 μl of loading buffer, bound and free DNA were resolved by fractionation on a 6% native polyacrylamide TBE gel (Bio-Rad) in 0.5× TBE. Gels were pre-run for 40 min at 100 V, and run with samples under the same conditions for 40 min. The DNA-protein complex was transferred onto Biodyne B Nylon Membrane (PALL) at 380 mA for 1 h. The transferred DNA was cross-linked to the membrane at 120 mJ/cm2 for 60 s using a UV-light cross-linking instrument (DETIANYOU Technology). The biotin-labeled DNA was detected using the Chemiluminescent Nucleic Acid Detection Module (Pierce).

Statistical Analysis

Results are presented as the mean of three independent experiments ± S.E. An independent two-tailed Student's t test was performed. Differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

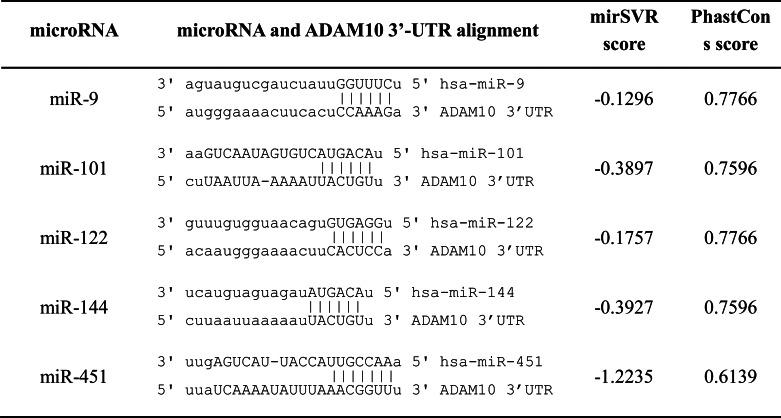

miR-144 Regulates ADAM10 Negatively

The computational program Miranda was used to detect potential miRNAs that could bind to the 3′-UTR of human ADAM10 mRNA (NM_001110). Combined with previous reports, we picked up three miRNAs as potential candidates: miR-9, miR-101, and miR-144, which are implicated in amyloidogenic gene and/or aberrantly express in AD patients (25, 29, 32). The sequences of the candidate miRNAs and their predicted MREs in the ADAM10 3′-UTR are listed in Table 2. To further investigate the potential function of the candidate miRNAs on ADAM10 expression, luciferase assays were performed in human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells. The result demonstrated that, except for the positive control miR-122 (33, 34), only transfection with the miR-144 mimics resulted in a significant luciferase activity down-regulation of the ADAM10 3′-UTR reporter (Fig. 1A). A down-regulation in the luciferase activity after miR-144 transfection was also observed in HeLa cells (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Candidate miRNAs sequences with their potential MRE in ADAM10 3′-UTR

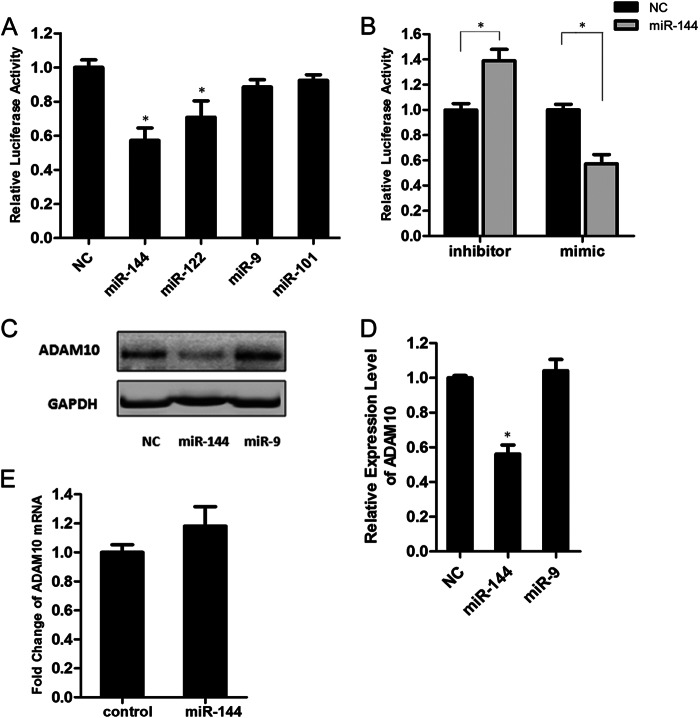

FIGURE 1.

Identification of miR-144 as a negative regulator of ADAM10. A, SH-SY5Y cells were transfected with the pmirGLO-ADAM10 3′-UTR reporter plasmid (0.05 μg) and miRNA mimics (50 nm) or cel-mir-67 mimics (negative control mimics, NC), which have no sequence identity with any human miRNAs. Luciferase activity was measured 48 h after transfection, and the values are shown as fold-change of the luciferase activity with respect to the negative control. B, SH-SY5Y cells were transfected with the pmirGLO-ADAM10 3′-UTR reporter plasmid and miR-144 inhibitor (100 nm) or miRNA inhibitor negative control (inhibitor NC). The dual luciferase assay was performed 48 h after transfection, and the luciferase activity of the miRNA inhibitor negative control was regarded as 1. C, Western blot analysis of endogenous ADAM10 protein levels in SH-SY5Y cells transfected with the miRNA negative control and miR-144 or miR-9 mimics. GAPDH served as an internal control. D, intensities of the ADAM10 bands from three independent experiments were quantified and normalized to that of the corresponding GAPDH bands. The values were plotted as fold-change with respect to the negative control. E, quantitative RT-PCR analysis of the ADAM10 mRNA levels in SH-SY5Y cells transfected with the miRNA negative control or miR-144 mimics. Values in A, B, D, and E are mean ± S.E. from experiments performed in triplicate. Asterisks indicate significant differences (*, p < 0.05).

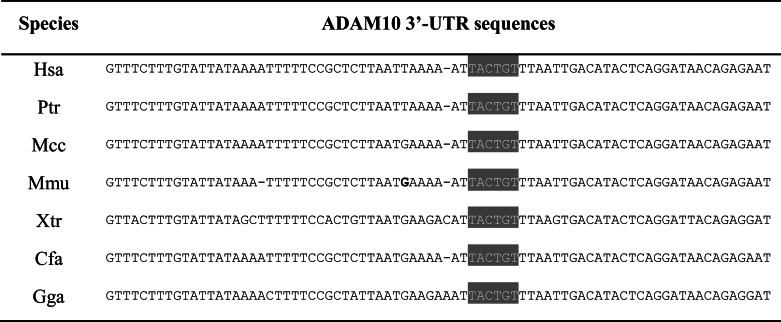

Previous genome-wide analysis of miRNA expression demonstrated that compared with global miRNA down-regulation, miR-144 is significantly increased both in elderly primate brains and in AD patients (32). Moreover, bioinformatics analysis revealed that the putative MRE for miR-144 in the ADAM10 3′-UTR is strictly conserved in vertebrates (Table 3). These observations further prompted us to analyze the function of miR-144 on ADAM10 expression. In miR-144 loss-of-function experiments, we found that the miR-144 inhibitor up-regulated the luciferase activity of the ADAM10 3′-UTR reporter (Fig. 1B). Moreover, ADAM10 protein levels are remarkably decreased upon transient overexpression of miR-144 in SH-SY5Y cells (Fig. 1, C and D). However, ADAM10 protein levels were not altered after overexpression of miR-9, which also possesses a putative MRE in the ADAM10 3′-UTR, indicating the specificity of miR-144 in the regulation of ADAM10 levels. Identical data were obtained in HeLa cells (data not shown). In addition, a decrease in the mRNA level of ADAM10 upon miR-144 overexpression was not observed (Fig. 1E). These results thus identify miR-144 as a negative regulator of ADAM10 and suggest that repression of the ADAM10 protein induced by miR-144 does not occur via ADAM10 mRNA degradation but may be achieved at the translational level.

TABLE 3.

Alignment of the ADAM10 3′-UTR displaying that potential MRE for miR-144 is conserved across species

Hsa, Homo sapiens; Ptr, Pan troglodytes; Mcc, Macaca mulatta; Mmu, Mus musculus; Gga, Gallus gallus; Cfa, Canis familiaris; Xtr, Xenopus tropicalis.

Analysis of miR-144 MRE within ADAM10 3′-UTR

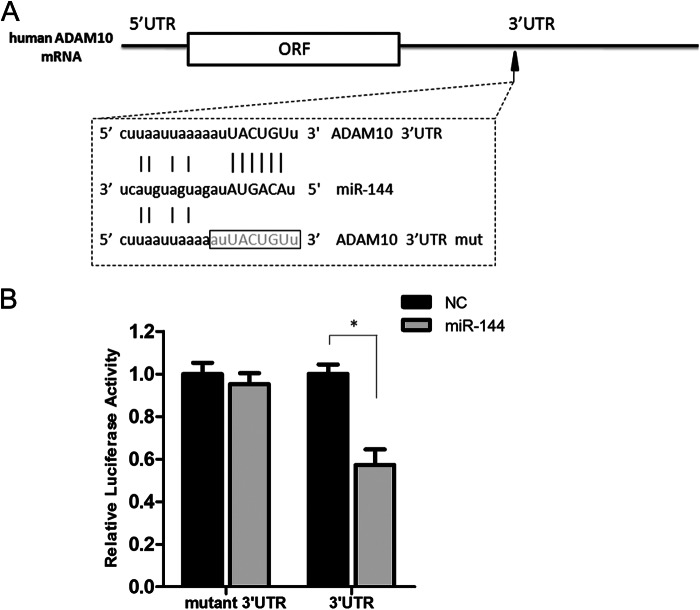

Regulation of target genes by miRNAs is dependent on imperfect base pairing of the miRNAs to the 3′-UTR of their target mRNAs through a 2–8-nucleotide seed region located near the 5′-end of the miRNA (35). As shown in Fig. 2A, miR-144 was predicted to possess a putative MRE within the ADAM10 3′-UTR. To investigate whether miR-144-induced ADAM10 repression occurred via specific binding to the MRE in the ADAM10 mRNA 3′-UTR, a mutant luciferase reporter construct that lacks the potential MRE of miR-144 was generated. The luciferase assay analysis demonstrated that the mutant reporter construct was insensitive to miR-144-mediated inhibition compared with the wild type (Fig. 2B). This result indicates that miR-144-induced ADAM10 repression depends on the direct binding of miR-144 to its MRE within the ADAM10 mRNA 3′-UTR.

FIGURE 2.

Analysis of the miR-144 MRE within the ADAM10 3′-UTR. A, schematic representation of the human ADAM10 3′-UTR indicating the putative MRE for miR-144 and the sequences of the mutant reporter constructs created by PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis. B, the ADAM10 3′-UTR luciferase reporter (3′UTR) or mutant construct without the predicted miR-144 MRE (mutant 3′UTR) was transfected with either miR-144 mimics or control mimics (NC) into SH-SY5Y cells. The dual luciferase assays were performed 48 h after transfection. The fold-change in relative luciferase activity was plotted; dark and gray bars indicate luciferase activity of the negative control and miR-144, respectively. Results are presented as mean ± S.E. from experiments performed in triplicate. Asterisks indicate significant differences (*, p < 0.05).

Identification of miR-144 Promoter

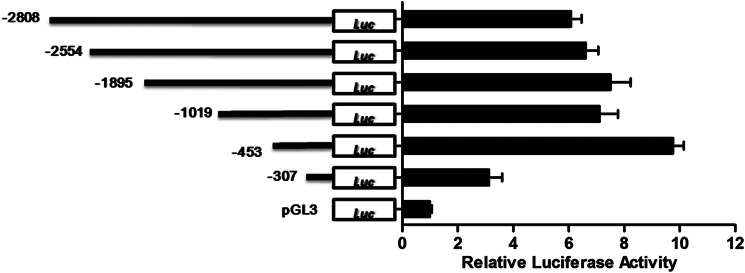

The demonstration that miR-144 is a negative regulator of ADAM10 expression prompted us to examine the transcriptional regulation of miR-144 and its implication(s) in AD. Using the publicly accessible algorithm MiRStart (36), which integrates three datasets including cap analysis of gene expression (CAGE) Tags (37, 38), TSS Seq libraries, and H3K4me3 chromatin signatures, the site at −371 bp upstream of the miR-144 precursor was predicted as the TSS of the primary miR-144. To experimentally verify this putative TSS, we generated a luciferase reporter construct containing the 2.8-kb region upstream of the precursor miR-144, named pGL3-promoter-2808. According to sequence conservation data, five additional luciferase reporter constructs containing decreasing lengths of the upstream sequence (−2554, −1895, −1019, −453, and −307) were derived. The six luciferase reporter constructs and the pGL3-basic plasmid were then each transfected into SH-SY5Y cells to determine the basal promoter activity. As shown in Fig. 3, the pGL3-promoter-453 construct (i.e. the 453-bp putative promoter region) displayed the highest luciferase activity, which was ∼10-fold greater than pGL3-basic. The fact that the other four reporter constructs with longer upstream sequences exhibited luciferase activities at comparable levels to that of pGL3-promoter-453 and that pGL3-promoter-307 displayed a dramatic decrease in luciferase activity further support that the TSS is located in the −307 to −453-bp region. The similar result was also observed in HeLa cells (data not shown). These results match our bioinformatics prediction and indicate that the 453-bp region upstream of the precursor miR-144 possesses intact promoter activity triggering miR-144 transcription.

FIGURE 3.

Identification of the miR-144 promoter by luciferase assays. Identification of miR-144 promoter activity by luciferase assays in SH-SY5Y cells. The luciferase reporter construct (−2080), containing the ∼2-kb region upstream of the precursor miR-144 and its deletion derivate (−2554, −1895, −1019, −453, and −307) were each transfected into SH-SY5Y cells, and dual luciferase assays were performed 48 h after transfection. For each reporter construct, the histogram shows the relative luciferase activity levels, evaluated as the ratio between each value versus the pGL3 basic vector; the schematic is on the right. Values are mean ± S.E. from experiments performed in triplicate.

Transcriptional Regulation of miR-144

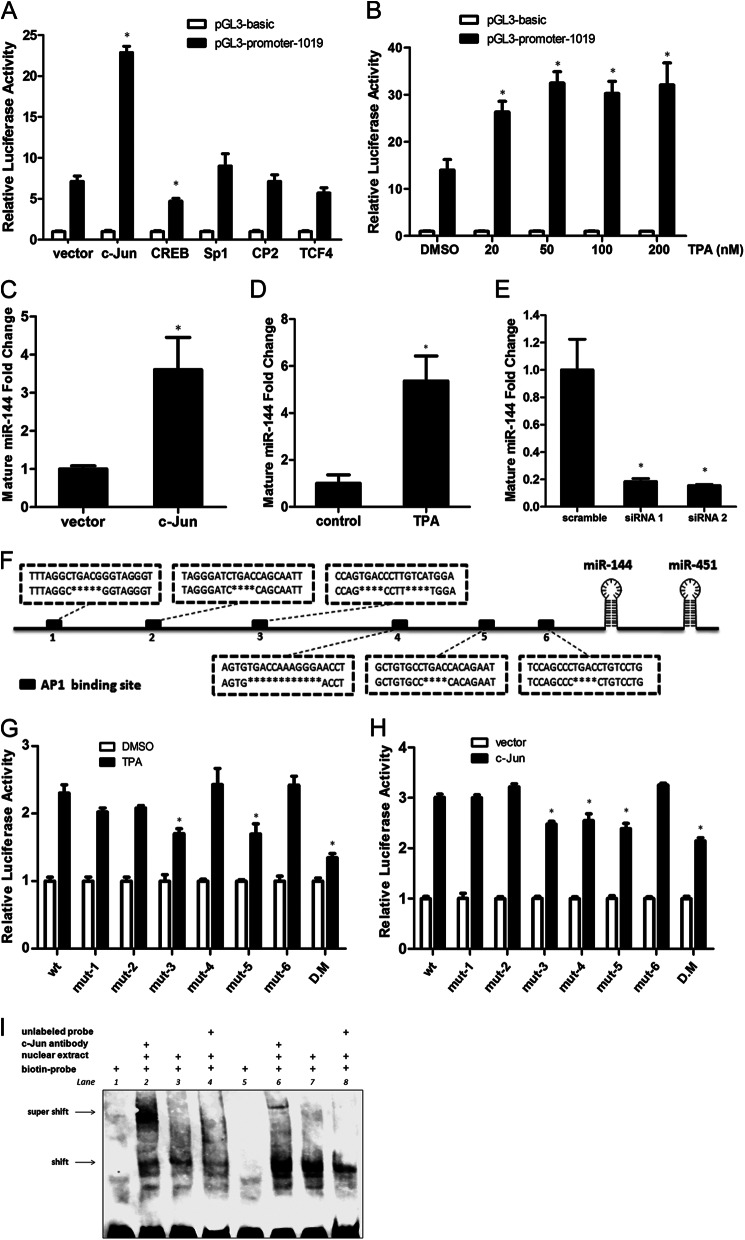

To investigate the key transcription factors involved in miR-144 transcription, the ∼1-kb region upstream of the miR-144 TSS was analyzed by transcription factor binding prediction software. SP1, AP-1, CREB, CP2, and TCF4 were predicted to possess putative binding sites in this region. Thus, these five transcription factor were cloned into expression vectors and each co-transfected with the pGL3-promoter-1019 reporter into SH-SY5Y cells. As shown in Fig. 4A, relative to the other four transcription factors, overexpression of c-Jun, a common component of the AP-1 protein complex that can bind to AP-1 recognition sites (39–41), resulted in a strong increase in the luciferase activity. Moreover, the luciferase activity was also increased in a dose-dependent manner after treatment of TPA, which can induce transcription from the AP-1-driven promoter (42, 43) (Fig. 4B). Meanwhile, the endogenous expression of miR-144 was also significantly increased by c-Jun overexpression (Fig. 4C) and TPA treatment (Fig. 4D), but decreased after endogenous c-Jun was knocked down (Fig. 4E).

FIGURE 4.

Transcriptional regulation of miR-144. A, luciferase activity of the pGL3-promoter-1019 reporter after co-transfection into SH-SY5Y cells with an expression plasmid encoding the SP1, c-Jun, CREB, CP2, or TCF4 transcription factor, respectively. Values were calculated as the ratio of the luciferase activities in cells co-transfected with pGL3-promoter-1019 and a transcription factor expression plasmid versus in cells that were co-transfected with pGL3 basic vector and the same expression plasmid. B, dual luciferase activity assay after treatment with the indicated concentration of TPA in SH-SY5Y cells that were transfected with the pGL3-promoter-1019 reporter plasmid. Values were calculated as the ratio of luciferase activities in cells transfected with pGL3-promoter-1019 versus in cells transfected with pGL3 basic vector treated with TPA of same concentration. C, quantitative RT-PCR analysis of the level of endogenous mature miR-144 in SH-SY5Y cells after 24 h transfection of c-Jun expression plasmid. D, quantitative RT-PCR analysis of the level of endogenous mature miR-144 in SH-SY5Y cells after a 12-h TPA (50 nm) treatment. E, the levels of miR-144 were analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR 48 h after transfection of c-Jun siRNA-1 or siRNA-2 in SH-SY5Y cells. F, schematic representation of the gene encoding miR-144 and miR-451, as well as the promoter region with six potential AP-1 binding sites with the sequences deleted by PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis in each mutant reporter. G, each single mutant (mut-1 to mut-6) or double mutant (D.M.) reporter plasmid, or the wild type (wt) plasmid was transfected into SH-SY5Y cells, 24 h after the transfection the cells were treated with or without TPA (20 nm), and the dual luciferase activity assay was performed after another 12 h. Values were calculated as the ratio of luciferase activities in cells transfected with wild type or mutant reporter plasmids and treated with TPA versus cells transfected with the same reporter plasmid and treated with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). H, each mutant reporter plasmid or the wild type plasmid was co-transfected with c-Jun expression vector into SH-SY5Y cells, the dual luciferase activity assay was performed 48 h after the transfection. I, 2 μl of SH-SY5Y cells nuclear extracts were incubated with 50 fmol of biotin-labeled DNA probe corresponding to putative AP-1 binding site 3 in miR-144 promoter (lanes 2–4) or with the biotin-labeled DNA probe corresponding to binding site 5 (lanes 6–8). For binding competition, 200-fold excess of unlabeled DNA probe was included in the reaction (lanes 4 and 8). For the supershift assay, c-Jun antibody was included (lanes 2 and 6). Results in A–E, G, and H are presented as mean ± S.E. from experiments performed in triplicate. Asterisks indicate significant differences (*, p < 0.05).

As shown in Fig. 4F, six potential AP-1 binding sites are predicted to locate in the ∼1-kb region upstream of the miR-144 precursor. We used deletion mutagenesis to abolish each site and then performed luciferase assays. The results showed that, compared with the wild type, mut-3, mut-5, and the double mutation (mutation of binding sites 3 and 5) constructs inhibited the TPA-induced transcriptional activity by 26.1, 26.4, and 41.6%, respectively (Fig. 4G). However, mutation of any other AP-1 binding site did not remarkably affect the transcriptional activity upon TPA treatment. The similar result was observed when c-Jun was overexpressed (Fig. 4H). In addition, the binding properties of AP-1 at sites 3 and 5 were further validated by performing EMSA and supershift assay. DNA probes corresponding to AP-1 binding sites 3 and 5, which contained the putative AP-1 binding sequences and their flanking region at both sides in the human miR-144 promoter, were tested. Incubation of either biotin-labeled probe with the SH-SY5Y cell nuclear extracts caused a major retarded band (Fig. 4I, lanes 3 and 7). Excessive amounts of unlabeled probes prevented each labeled probe from binding with AP-1, as indicated by the dim retarded band (Fig. 4I, lanes 4 and 8). Additionally, incubation of c-Jun antibody caused supershift bands (Fig. 4I, lanes 2 and 6), indicating the presence of c-Jun in the binding complex. These results fully demonstrate that AP-1 can regulate the transcription of miR-144 by binding the potential sites in its promoter.

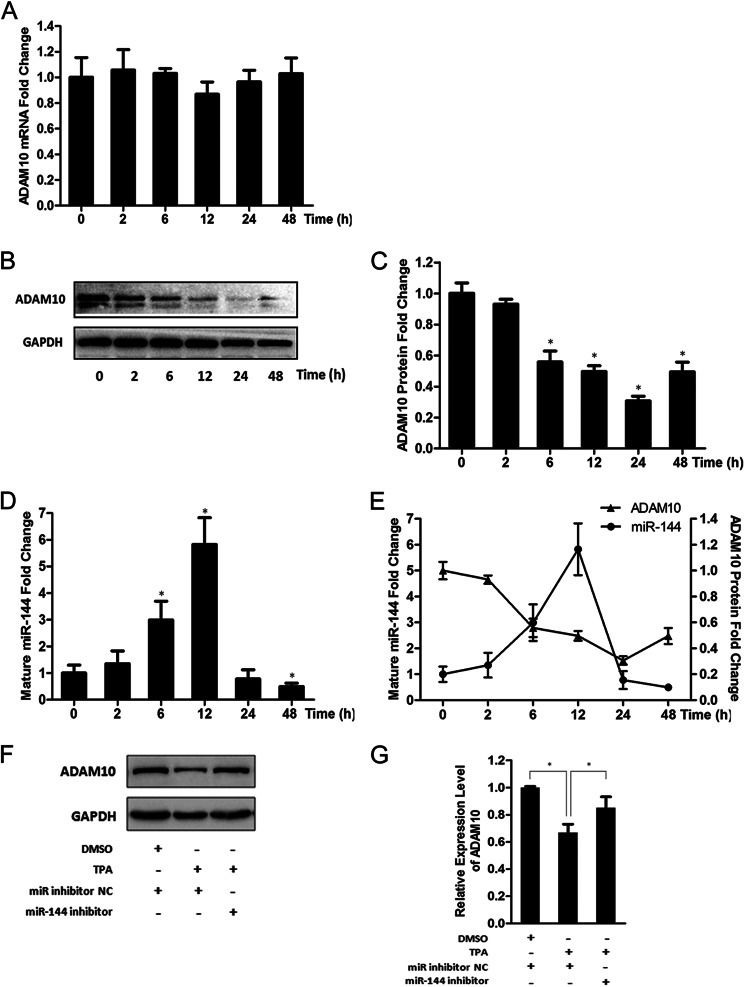

miR-144 Contributes to the Down-regulation in ADAM10 Protein in the Presence of TPA

In vivo evidence demonstrates that the protein levels of ADAM10 and/or APPsα are decreased in AD patients (5, 10, 11), whereas expression or activity of AP-1/c-Jun is increased (44–46). Additionally, we have demonstrated that miR-144 acts as a negative regulator of ADAM10 and is regulated by AP-1/c-Jun. Prompted by these observation, we next investigated whether ADAM10 changes in the presence of TPA, and whether miR-144 might be causally involved in regulating such changes. To test this, we initially determined both ADAM10 mRNA and protein levels in SH-SY5Y cells after TPA treatment. We found that, although the level of ADAM10 mRNA was unchanged in the presence of TPA (Fig. 5A), the level of ADAM10 protein was down-regulated sustained in the first 24 h and then started to increase (Fig. 5, B and C). The inconsistent changes between the mRNA and protein strongly imply that down-regulation of the ADAM10 protein in the presence of TPA is primarily exerted at the translational level. Meanwhile, using quantitative RT-PCR analysis, we found that the endogenous mature miR-144 was induced after TPA treatment, peaked at 12 h, and then started to decrease (Fig. 5D). Notably, the increase in the level of miR-144 exhibited an evident inverse correlation with the change of the ADAM10 protein in at least the first 12 h after the initiation of TPA treatment (Fig. 5E). The incomplete inverse correlation displayed after the 12-h point may be due to involvement of other signal pathways activated by TPA. Furthermore, miR-144 loss-of-function experiments revealed that repression of the ADAM10 protein induced by TPA was restored by miR-144 inhibition (Fig. 5, F and G). These data thus further supports the notion that miR-144 is a negative regulator of ADAM10 protein and strongly imply that the AD-associated increase in expression or activity of AP-1/c-Jun as well as elevated expression in miR-144 may contribute to the reduction of the ADAM10 protein in AD pathogenesis.

FIGURE 5.

miR-144 contributes to the down-regulation of ADAM10 protein in response to TPA treatment. A, the mRNA levels of ADAM10 after treatment of TPA (50 nm) for the indicated time intervals were analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR and plotted as fold-change with respect to untreated control. B, representative results from three independent Western blot analyses of ADAM10 protein in SH-SY5Y cells treated with TPA (50 nm) after the indicated time intervals. GAPDH served as an internal control. C, intensities of the ADAM10 bands for each time interval from three independent experiments were quantified by densitometry. The values were normalized to that of corresponding GAPDH bands and plotted as fold-change with respect to the dimethyl sulfoxide-treated control. D, quantitative RT-PCR analysis of the endogenous mature miR-144 after TPA (50 nm) treatment for the indicated time intervals. E, demonstration of the inverse correlation between the ADAM10 protein and mature miR-144 levels in SH-SY5Y cells after TPA treatment for the indicated times intervals. F, SH-SY5Y cells with or without miR-144 loss-of-function by transfection with the miR-144 inhibitor or mirRNAs inhibitor negative control (miR inhibitor NC) were treated with TPA (20 nm) for 24 h, then the ADAM10 protein levels in cells were analyzed by Western blot. G, intensities of ADAM10 bands from three independent experiments were quantified and normalized to that of the corresponding GAPDH bands. The values were plotted as the fold-change with respect to the negative control. Values in A, C–E, and G are mean ± S.E. from experiments performed in triplicate. Asterisks indicate significant differences (*, p < 0.05). DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide.

miR-144 Contributes to ADAM10 Down-regulation upon Aβ Treatment

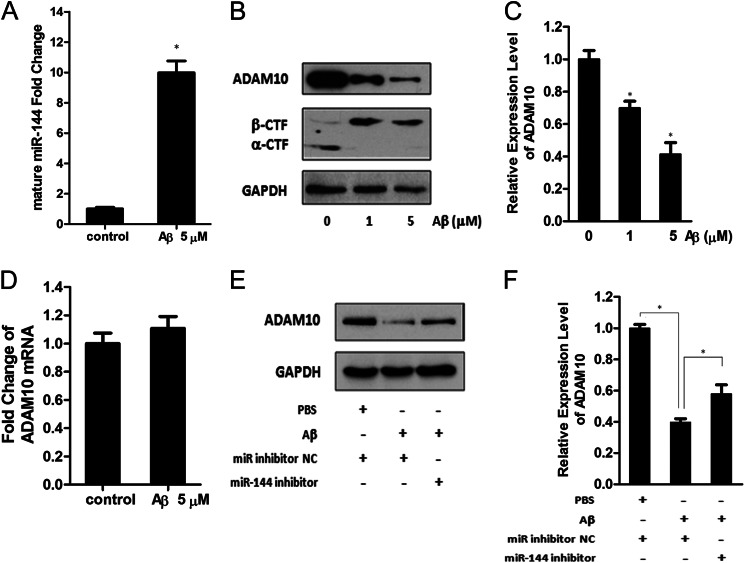

As one of the crucial pathological causes of AD, Aβ phosphorylates and activates c-Jun in vitro (47–49). Thus, we further investigated the levels of miR-144 in SH-SY5Y cells after incubation with Aβ42 peptide, which is amyloidogenic and is the major component of neuritic plaques (50, 51). Quantitative RT-PCR analysis demonstrated that mature miR-144 levels were strongly increased after incubation with Aβ42 peptide (Fig. 6A). Meanwhile, we analyzed ADAM10 protein and mRNA levels after Aβ42 treatment. As shown in Fig. 6, B and C, the ADAM10 protein level significantly decreased upon treatment with Aβ42. Additionally, the APP carboxyl-terminal fragment (α-CTF), a membrane-bound APP derivation truncated by ADAM10, was also suppressed, and APP β-CTF was correspondingly increased in the presence of Aβ42, further indicating a decrease in ADAM10 expression or activity. However, ADAM10 mRNA levels were not changed upon Aβ42 treatment (Fig. 6D), implying that the Aβ42-induced ADAM10 down-regulation is also mainly achieved at the translational level. To further investigate whether the increase of miR-144 is involved in the down-regulation of ADAM10 protein caused by Aβ42, we performed a miR-144 loss-of-function experiment. As shown in Fig. 6, E and F, repression of the ADAM10 protein caused by Aβ42 was partially restored after transfection of the miR-144 inhibitor. This result suggests that Aβ42-induced miR-144 overexpression contributes to the repression of ADAM10 protein levels. However, the fact that the miR-144 inhibitor did not completely abolish the decrease in ADAM10 induced by Aβ42 implies that regulation of ADAM10 expression cannot solely be explained by the action of miR-144 and that additional regulatory pathways must be involved.

FIGURE 6.

miR-144 is regulated by Aβ and contributes to the repression of ADAM10 induced by Aβ. A, the level of endogenous mature miR-144 24 h after treatment with the Aβ42 peptide (5 μm) was measured by quantitative RT-PCR and plotted as fold-change with respect to PBS-treated control. B, ADAM10 protein, α-CTF, and β-CTF in SH-SY5Y cells 24 h after treatment with the Aβ42 peptide at the indicated concentrations were analyzed by Western blot. C, intensities of the ADAM10 bands from three independent experiments were quantified and normalized to that of the corresponding GAPDH bands. The values were plotted as the fold-change with respect to the PBS-treated control. D, quantitative RT-PCR analysis of ADAM10 mRNA in SH-SY5Y cells 24 h after treatment with Aβ42 peptide (5 μm). E, SH-SY5Y cells with or without miR-144 loss-of-function by transfection with the miR-144 inhibitor or the negative control of the mirRNAs inhibitor (miR inhibitor NC) were treated with Aβ42 (5 μm) peptide for 24 h, then the levels of ADAM10 protein in the cells were analyzed by Western blot. F, intensities of the ADAM10 bands from three independent experiments were quantified and normalized to that of the corresponding GAPDH bands. The relative expression of ADAM10 was plotted as the fold-change with respect to the negative control. Results in A, C, D, and F are presented as mean ± S.E. from experiments performed in triplicate. Asterisks indicate significant differences (*, p < 0.05).

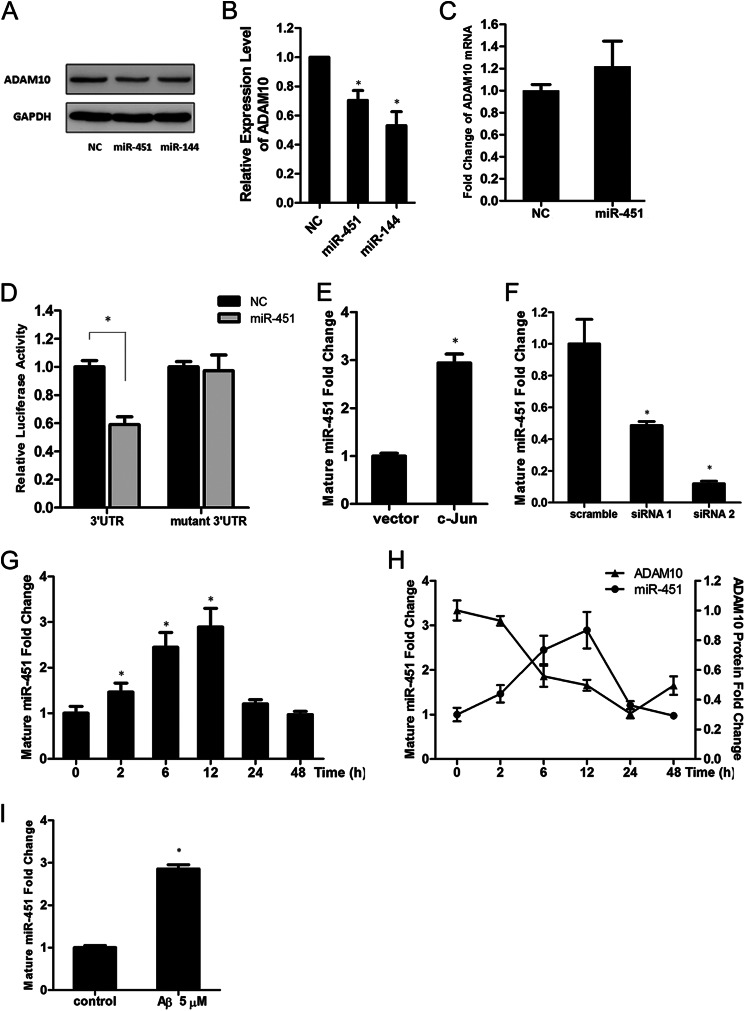

miR-451, a miRNA Processed from a Single Gene Locus with miR-144, Is also Involved in the Regulation of ADAM10 Expression

miR-451 is co-transcribed with miR-144 from a single locus (52) and is predicted to bind to the ADAM10 3′-UTR (Table 2). In some cases, miR-451 and miR-144 share the same mechanism of transcriptional regulation and display synergistic depressive effects on their target proteins (52, 53). Thus, we investigated whether miR-451 is involved in regulation of the ADAM10 protein and whether it is also controlled by c-Jun. We found that, although the putative MRE for miR-451 in the ADAM10 3′-UTR is not conserved in vertebrates (data not shown), overexpression of miR-451 in SH-SY5Y cells also attenuated the ADAM10 protein (Fig. 7, A and B), and did not change the ADAM10 mRNA level (Fig. 7C). Meanwhile, miR-451 overexpression significantly decreased the activity of the luciferase reporter containing the ADAM10 3′-UTR, but not that of a mutant luciferase reporter construct that lacks the potential miR-451 MRE (Fig. 7D), indicating that ADAM10 repression caused by miR-451 also depends on the binding of MRE in ADAM10 3′-UTR. Similar to miR-144, the level of endogenously mature miR-451 was increased by c-Jun overexpression (Fig. 7E) and decreased when c-Jun was knocked down (Fig. 7F). Moreover, in the presence of TPA, the level of miR-451 also changed in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 7G), displayed a nearly identical pattern of miR-144, and was also inversely correlated with ADAM10 protein levels in the first 12 h after initiation of the TPA treatment (Fig. 7H). In addition, the level of mature miR-451 was also significantly increased after incubation with the Aβ42 peptide (Fig. 7I). These results suggest that, as another negative regulator of the ADAM10 protein, miR-451 may share the same function and mechanism of transcriptional regulation with miR-144 in AD pathogenesis.

FIGURE 7.

miR-451 is also involved in the regulation of ADAM10 expression. A, Western blot analysis of the ADAM10 protein in SH-SY5Y cells after transfection with miR-451 or miR-144 mimics. The miR-144 mimics were used as a positive control. B, intensities of ADAM10 bands from three independent experiments were quantified and normalized to that of the corresponding GAPDH bands. The values were plotted as fold-change with respect to the negative control. C, quantitative RT-PCR analysis of ADAM10 mRNA in SH-SY5Y cells after transfection with miR-451. D, the ADAM10 3′-UTR luciferase reporter (3′UTR) or mutant construct without the predicted miR-451 MRE (mutant 3′UTR) was transfected with either miR-451 mimics or control mimics (NC) into SH-SY5Y cells. The dual luciferase assays were performed 48 h after transfection. The fold-change in relative luciferase activity was plotted; dark and gray bars indicate luciferase activity of the negative control and miR-451, respectively. E, quantitative RT-PCR analysis of the level of endogenous mature miR-451 in SH-SY5Y cells 24 h after transfection of c-Jun plasmid. F, 48 h after transfection of c-Jun siRNA-1 or siRNA-2 in SH-SY5Y cells, the levels of endogenous mature miR-451 were analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR. G, quantitative RT-PCR analysis of the endogenous mature miR-451 after TPA (50 nm) treatment for the indicated time intervals. H, demonstration of the inverse correlation between the levels of ADAM10 protein and endogenous mature miR-451 in SH-SY5Y cells after TPA (50 nm) treatment for the indicated time intervals. I, the level of endogenous mature miR-451 24 h after the treatment with Aβ42 peptide (5 μm) was measured by quantitative RT-PCR and plotted as the fold-change with respect to the PBS-treated control. Results in B–I are mean ± S.E. from experiments performed in triplicate. Asterisks indicate significant differences (*, p < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

Brain aging is a major risk factor for the development of AD and other prevalent neurodegenerative disorders (54). This implies that genetic changes occured in the process of brain aging play coordinating roles with environmental stress to lead to the onset of AD and other neurodegenerative pathologies. However, these genetic changes and their implications in such diseases remain largely unknown. Genome-wide analysis of miRNA expression has revealed that compared with global miRNA down-regulation, miR-144 is the sole miRNA that is consistently elevated in the brains of elderly humans, chimpanzees, and rhesus macaques, and it is also increased in AD patients (32). Because miR-144 could suppress the expression of ADAM10, the elevated miR-144 in aging brains at least partially induces the depletion of ADAM10 protein levels and increases the susceptibility to environmental stress, which may in turn determine the onset of AD. Moreover, growing evidence supports the concept that AD is fundamentally a metabolic disease with derangements in brain glucose utilization and responsiveness to insulin and insulin-like growth factor stimulation. The impaired insulin and insulin-like growth factor signaling contributes to AD-associated neuronal loss, synaptic disconnection, τ hyperphosphorylation, and Aβ accumulation (55). Similarly, miR-144 is also increased and impairs insulin signaling through down-regulation of insulin receptor substrate 1 (56) in impaired fasting glucose and Type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. This suggests the importance and multiple implications of miR-144 in the pathogenesis of sporadic AD.

Recent reports document that ADAM10 expression is regulated both transcriptionally and post-transcriptionally. Specifically, retinoic acid enhances ADAM10 transcription by promoting the binding of a non-permissive dimer of retinoic acid receptor-α and retinoid X receptor-β to retinoic acid-responsive elements in the promoter of the ADAM10 gene (57, 58). ADAM10 transcription is also regulated by PAX2 in renal cancer cells (59) and melanocytes (60). In addition, expression of ADAM10 is suppressed by its 5′-UTR (61), and ADAM10 activity can be blocked by its own predomain (62). Although many reports on ADAM10 regulation have been published in the past several years, none present a reasonable mechanism for ADAM10 down-regulation in AD patients. Here, we demonstrated that miR-144 suppresses ADAM10 expression via a classical interaction with the ADAM10 3′-UTR. Thus, the elevated levels of miR-144 in AD patients may be responsible for the down-regulation of ADAM10 protein levels. Additionally, it was observed that the level of ADAM10 mRNA is not affected by miR-144 or TPA (Figs. 1E and 5A), suggesting that the negative regulation of ADAM10 by miR-144 is mainly achieved at the translational level. Same as our basic research finding, the clinical reports showed that ADAM10 proteins levels are decreased in the neurons of AD patients (6), but ADAM10 mRNA levels are increased in hippocampal samples from severe AD cases (63). These two seemingly incompatible observations also imply that translational regulation of ADAM10 exists in the pathogenesis of AD.

The functions of miRNAs in gene regulation have been extensively studied in the last decade. At the same time, research interests have gradually focused on the mechanism(s) by which miRNAs are controlled. In our study, we both identified miR-144 as a negative regulator of ADAM10 and demonstrated that AP-1/c-Jun regulates miR-144 transcription. Consistent with our results, recent studies also demonstrate that c-Jun regulates expression of miRNAs at the transcriptional level (64–66). Moreover, there is evidence showing an increase in c-Jun expression in the neurons of AD patients (45, 47). In postmortem pathological brain samples, phosphorylated c-Jun staining is found only in the affected regions of the cerebral cortex and hippocampus (67). Furthermore, c-Jun influences the initiation and execution of Aβ-induced neuronal apoptosis (68–70). These findings suggest that the induction of c-Jun is crucial to the pathogenesis of AD. However, previous studies defining the implication of the AP-1/c-Jun pathway in AD mainly concentrate on its involvement in neuronal apoptosis. Here, we demonstrated that AP-1 may directly participate in amyloidogenesis by regulating miR-144.

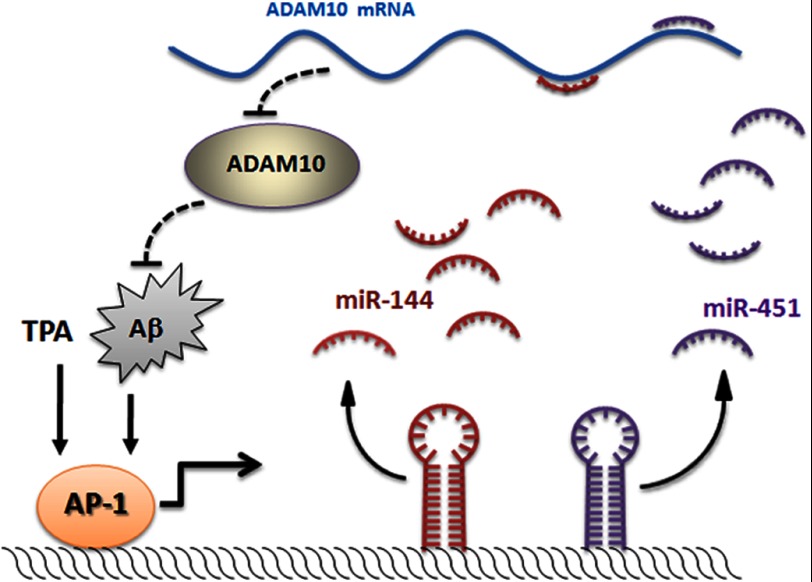

Notably, AP-1 is not the only transcription factor activated after Aβ treatment in vitro or Aβ deposition in vivo. For instance, there is evidence that Aβ treatment of human brain endothelial cells results in increases in the activities of the AP-1, CREB, GATA, NFATc, and GRE transcription factors (47). Among these, the GATA family was previously reported to regulate transcription of miR-144 and miR-451 (52, 53). Thus, a vicious circle in AD pathogenesis composed of Aβ, AP-1/c-Jun, miR-144, and ADAM10 is emerging. In detail, miR-144 elevates in ordinary aging population or in early stage AD patients, and decreases ADAM10 protein levels, which hampers the non-amyloidogenic pathway, and forces metabolism of Aβ to shift to favor Aβ production. When Aβ is overproduced, brain deterioration begins, then AP-1, GATA, and other transcription factors are recruited or activated, and in turn, further promotes miR-144/451 expression and consequently reinforces the process (Fig. 8), which could be to accelerate or interrupt by environmental factors. Although, until now, the first participant who starts the vicious circle is not known yet, we can see that miR-144/451 plays a crucial role in it. In conclusion, this study provides evidence that miR-144 decreases expression of the ADAM10 protein and demonstrates that miR-144 is transcriptionally regulated by AP-1/c-Jun, suggesting that miR-144 contributes to AD pathogenesis and pharmacological targeting miR-144 may represent a promising strategy in the management of AD.

FIGURE 8.

Regulatory feedback loop encompassing AP-1, miR-144, miR-451, and ADAM10. miR-144 and miR-451 bind to each MRE with the 3′-UTR of ADAM10 mRNA and decrease ADAM10 expression at the transcriptional level. The decrease in ADAM10 protein promotes amyloidogenesis. In turn, the increase in Aβ may activate AP-1 and other signaling pathways that may be involved in the regulation of miR-144 and miR-451.

This work was supported by a grant from the “J&J-Tsinghua Co-managed Fund” and the Chinese National Basic Research Program (973 Project, No. 2007CB507406).

- AD

- Alzheimer disease

- miR

- microRNA

- APP

- amyloid precursor protein

- AP-1

- activator protein-1

- TSS

- transcriptional start site

- TPA

- 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate

- CREB

- cAMP-response element-binding protein

- CTF

- carboxyl-terminal fragment

- MRE

- miRNA recognition element.

REFERENCES

- 1. Blennow K., de Leon M. J., Zetterberg H. (2006) Alzheimer's disease. Lancet 368, 387–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tanzi R. E., Bertram L. (2005) Twenty years of the Alzheimer's disease amyloid hypothesis. A genetic perspective. Cell 120, 545–555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Postina R., Schroeder A., Dewachter I., Bohl J., Schmitt U., Kojro E., Prinzen C., Endres K., Hiemke C., Blessing M., Flamez P., Dequenne A., Godaux E., van Leuven F., Fahrenholz F. (2004) A disintegrin-metalloproteinase prevents amyloid plaque formation and hippocampal defects in an Alzheimer disease mouse model. J. Clin. Invest. 113, 1456–1464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Postina R. (2008) A closer look at α-secretase. Curr. Alzheimer Res 5, 179–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Colciaghi F., Borroni B., Pastorino L., Marcello E., Zimmermann M., Cattabeni F., Padovani A., Di Luca M. (2002) α-Secretase ADAM10 as well as αAPPs is reduced in platelets and CSF of Alzheimer disease patients. Mol. Med. 8, 67–74 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bernstein H. G., Bukowska A., Krell D., Bogerts B., Ansorge S., Lendeckel U. (2003) Comparative localization of ADAMs 10 and 15 in human cerebral cortex normal aging, Alzheimer disease and Down syndrome. J. Neurocytol. 32, 153–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lammich S., Kojro E., Postina R., Gilbert S., Pfeiffer R., Jasionowski M., Haass C., Fahrenholz F. (1999) Constitutive and regulated α-secretase cleavage of Alzheimer's amyloid precursor protein by a disintegrin metalloprotease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 3922–3927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jorissen E., Prox J., Bernreuther C., Weber S., Schwanbeck R., Serneels L., Snellinx A., Craessaerts K., Thathiah A., Tesseur I., Bartsch U., Weskamp G., Blobel C. P., Glatzel M., De Strooper B., Saftig P. (2010) The disintegrin/metalloproteinase ADAM10 is essential for the establishment of the brain cortex. J. Neurosci. 30, 4833–4844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kuhn P. H., Wang H., Dislich B., Colombo A., Zeitschel U., Ellwart J. W., Kremmer E., Rossner S., Lichtenthaler S. F. (2010) ADAM10 is the physiologically relevant, constitutive α-secretase of the amyloid precursor protein in primary neurons. EMBO J. 29, 3020–3032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sennvik K., Fastbom J., Blomberg M., Wahlund L. O., Winblad B., Benedikz E. (2000) Levels of α- and β-secretase cleaved amyloid precursor protein in the cerebrospinal fluid of Alzheimer's disease patients. Neurosci. Lett. 278, 169–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fellgiebel A., Kojro E., Müller M. J., Scheurich A., Schmidt L. G., Fahrenholz F. (2009) CSF APPs α and phosphorylated tau protein levels in mild cognitive impairment and dementia of Alzheimer's type. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 22, 3–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bartel D. P. (2004) MicroRNAs. Genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 116, 281–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nilsen T. W. (2007) Mechanisms of microRNA-mediated gene regulation in animal cells. Trends Genet. 23, 243–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mehler M. F., Mattick J. S. (2006) Non-coding RNAs in the nervous system. J. Physiol. 575, 333–341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Vo N., Klein M. E., Varlamova O., Keller D. M., Yamamoto T., Goodman R. H., Impey S. (2005) A cAMP-response element binding protein-induced microRNA regulates neuronal morphogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 16426–16431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yu J. Y., Chung K. H., Deo M., Thompson R. C., Turner D. L. (2008) MicroRNA miR-124 regulates neurite outgrowth during neuronal differentiation. Exp. Cell Res. 314, 2618–2633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schratt G. M., Tuebing F., Nigh E. A., Kane C. G., Sabatini M. E., Kiebler M., Greenberg M. E. (2006) A brain-specific microRNA regulates dendritic spine development. Nature 439, 283–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Leucht C., Stigloher C., Wizenmann A., Klafke R., Folchert A., Bally-Cuif L. (2008) MicroRNA-9 directs late organizer activity of the midbrain-hindbrain boundary. Nat. Neurosci. 11, 641–648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Laneve P., Gioia U., Andriotto A., Moretti F., Bozzoni I., Caffarelli E. (2010) A minicircuitry involving REST and CREB controls miR-9–2 expression during human neuronal differentiation. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, 6895–6905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Conaco C., Otto S., Han J. J., Mandel G. (2006) Reciprocal actions of REST and a microRNA promote neuronal identity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 2422–2427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hébert S. S., De Strooper B. (2009) Alterations of the microRNA network cause neurodegenerative disease. Trends Neurosci. 32, 199–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Johnson R., Zuccato C., Belyaev N. D., Guest D. J., Cattaneo E., Buckley N. J. (2008) A microRNA-based gene dysregulation pathway in Huntington's disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 29, 438–445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hébert S. S., Horré K., Nicolaï L., Bergmans B., Papadopoulou A. S., Delacourte A., De Strooper B. (2009) MicroRNA regulation of Alzheimer's amyloid precursor protein expression. Neurobiol. Dis. 33, 422–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Patel N., Hoang D., Miller N., Ansaloni S., Huang Q., Rogers J. T., Lee J. C., Saunders A. J. (2008) MicroRNAs can regulate human APP levels. Mol. Neurodegeneration 3, 10–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Vilardo E., Barbato C., Ciotti M., Cogoni C., Ruberti F. (2010) MicroRNA-101 regulates amyloid precursor protein expression in hippocampal neurons. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 18344–18351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Long J. M., Lahiri D. K. (2011) MicroRNA-101 downregulates Alzheimer's amyloid-β precursor protein levels in human cell cultures and is differentially expressed. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 404, 889–895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Liu W., Liu C., Zhu J., Shu P., Yin B., Gong Y., Qiang B., Yuan J., Peng X. (2012) MicroRNA-16 targets amyloid precursor protein to potentially modulate Alzheimer's-associated pathogenesis in SAMP8 mice. Neurobiol. Aging 33, 522–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wang W. X., Rajeev B. W., Stromberg A. J., Ren N., Tang G., Huang Q., Rigoutsos I., Nelson P. T. (2008) The expression of microRNA miR-107 decreases early in Alzheimer's disease and may accelerate disease progression through regulation of β-site amyloid precursor protein-cleaving enzyme 1. J. Neurosci. 28, 1213–1223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hébert S. S., Horré K., Nicolaï L., Papadopoulou A. S., Mandemakers W., Silahtaroglu A. N., Kauppinen S., Delacourte A., De Strooper B. (2008) Loss of microRNA cluster miR-29a/b-1 in sporadic Alzheimer's disease correlates with increased BACE1/β-secretase expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 6415–6420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Boissonneault V., Plante I., Rivest S., Provost P. (2009) MicroRNA-298 and microRNA-328 regulate expression of mouse β-amyloid precursor protein-converting enzyme 1. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 1971–1981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hansson M. D., Rzeznicka K., Rosenbäck M., Hansson M., Sirijovski N. (2008) PCR-mediated deletion of plasmid DNA. Anal. Biochem. 375, 373–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Persengiev S., Kondova I., Otting N., Koeppen A. H., Bontrop R. E. (2011) Genome-wide analysis of miRNA expression reveals a potential role for miR-144 in brain aging and spinocerebellar ataxia pathogenesis. Neurobiol. Aging 32, 2316.e2317–2316.e2327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Augustin R., Endres K., Reinhardt S., Kuhn P. H., Lichtenthaler S. F., Hansen J., Wurst W., Trümbach D. (2012) Computational identification and experimental validation of microRNAs binding to the Alzheimer-related gene ADAM10. BMC Med. Genet. 13, 35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bai S., Nasser M. W., Wang B., Hsu S. H., Datta J., Kutay H., Yadav A., Nuovo G., Kumar P., Ghoshal K. (2009) MicroRNA-122 inhibits tumorigenic properties of hepatocellular carcinoma cells and sensitizes these cells to sorafenib. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 32015–32027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lewis B. P., Shih I. H., Jones-Rhoades M. W., Bartel D. P., Burge C. B. (2003) Prediction of mammalian microRNA targets. Cell 115, 787–798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chien C. H., Sun Y. M., Chang W. C., Chiang-Hsieh P. Y., Lee T. Y., Tsai W. C., Horng J. T., Tsou A. P., Huang H. D. (2011) Identifying transcriptional start sites of human microRNAs based on high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, 9345–9356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kawaji H., Severin J., Lizio M., Waterhouse A., Katayama S., Irvine K. M., Hume D. A., Forrest A. R., Suzuki H., Carninci P., Hayashizaki Y., Daub C. O. (2009) The FANTOM web resource. From mammalian transcriptional landscape to its dynamic regulation. Genome Biol. 10, R40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kawaji H., Severin J., Lizio M., Forrest A. R., van Nimwegen E., Rehli M., Schroder K., Irvine K., Suzuki H., Carninci P., Hayashizaki Y., Daub C. O. (2011) Update of the FANTOM web resource. From mammalian transcriptional landscape to its dynamic regulation. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, D856–860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Halazonetis T. D., Georgopoulos K., Greenberg M. E., Leder P. (1988) c-Jun dimerizes with itself and with c-Fos, forming complexes of different DNA binding affinities. Cell 55, 917–924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rauscher F. J., 3rd, Voulalas P. J., Franza B. R., Jr., Curran T. (1988) Fos and Jun bind cooperatively to the AP-1 site. Reconstitution in vitro. Genes Dev. 2, 1687–1699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Chiu R., Boyle W. J., Meek J., Smeal T., Hunter T., Karin M. (1988) The c-Fos protein interacts with c-Jun/AP-1 to stimulate transcription of AP-1 responsive genes. Cell 54, 541–552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Angel P., Imagawa M., Chiu R., Stein B., Imbra R. J., Rahmsdorf H. J., Jonat C., Herrlich P., Karin M. (1987) Phorbol ester-inducible genes contain a common cis element recognized by a TPA-modulated trans-acting factor. Cell 49, 729–739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lee W., Mitchell P., Tjian R. (1987) Purified transcription factor AP-1 interacts with TPA-inducible enhancer elements. Cell 49, 741–752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Anderson A. J., Pike C. J., Cotman C. W. (1995) Differential induction of immediate early gene proteins in cultured neurons by β-amyloid (Aβ). Association of c-Jun with A β-induced apoptosis. J. Neurochem. 65, 1487–1498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Marcus D. L., Strafaci J. A., Miller D. C., Masia S., Thomas C. G., Rosman J., Hussain S., Freedman M. L. (1998) Quantitative neuronal c-fos and c-jun expression in Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol. Aging 19, 393–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Thakur A., Wang X., Siedlak S. L., Perry G., Smith M. A., Zhu X. (2007) c-Jun phosphorylation in Alzheimer disease. J. Neurosci. Res. 85, 1668–1673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Vukic V., Callaghan D., Walker D., Lue L. F., Liu Q. Y., Couraud P. O., Romero I. A., Weksler B., Stanimirovic D. B., Zhang W. (2009) Expression of inflammatory genes induced by β-amyloid peptides in human brain endothelial cells and in Alzheimer's brain is mediated by the JNK-AP1 signaling pathway. Neurobiol. Dis. 34, 95–106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Xu J., Chen S., Ahmed S. H., Chen H., Ku G., Goldberg M. P., Hsu C. Y. (2001) Amyloid-β peptides are cytotoxic to oligodendrocytes. J. Neurosci. 21, RC118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Yin K. J., Lee J. M., Chen S. D., Xu J., Hsu C. Y. (2002) Amyloid-β induces Smac release via AP-1/Bim activation in cerebral endothelial cells. J. Neurosci. 22, 9764–9770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Roher A. E., Lowenson J. D., Clarke S., Woods A. S., Cotter R. J., Gowing E., Ball M. J. (1993) β-Amyloid-(1–42) is a major component of cerebrovascular amyloid deposits. Implications for the pathology of Alzheimer disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 10836–10840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Selkoe D. J. (2001) Alzheimer's disease. Genes, proteins, and therapy. Physiol. Rev. 81, 741–766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Dore L. C., Amigo J. D., Dos Santos C. O., Zhang Z., Gai X., Tobias J. W., Yu D., Klein A. M., Dorman C., Wu W., Hardison R. C., Paw B. H., Weiss M. J. (2008) A GATA-1-regulated microRNA locus essential for erythropoiesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 3333–3338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Zhang X., Wang X., Zhu H., Zhu C., Wang Y., Pu W. T., Jegga A. G., Fan G. C. (2010) Synergistic effects of the GATA-4-mediated miR-144/451 cluster in protection against simulated ischemia/reperfusion-induced cardiomyocyte death. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 49, 841–850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Yankner B. A. (2000) A century of cognitive decline. Nature 404, 125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. de la Monte S. M. (2012) Brain insulin resistance and deficiency as therapeutic targets in Alzheimer's disease. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 9, 35–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Karolina D. S., Armugam A., Tavintharan S., Wong M. T., Lim S. C., Sum C. F., Jeyaseelan K. (2011) MicroRNA 144 impairs insulin signaling by inhibiting the expression of insulin receptor substrate 1 in type 2 diabetes mellitus. PLoS One 6, e22839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Prinzen C., Müller U., Endres K., Fahrenholz F., Postina R. (2005) Genomic structure and functional characterization of the human ADAM10 promoter. FASEB J. 19, 1522–1524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Donmez G., Wang D., Cohen D. E., Guarente L. (2010) SIRT1 suppresses β-amyloid production by activating the α-secretase gene ADAM10. Cell 142, 320–332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 59. Doberstein K., Pfeilschifter J., Gutwein P. (2011) The transcription factor PAX2 regulates ADAM10 expression in renal cell carcinoma. Carcinogenesis 32, 1713–1723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Lee S. B., Doberstein K., Baumgarten P., Wieland A., Ungerer C., Bürger C., Hardt K., Boehncke W. H., Pfeilschifter J., Mihic-Probst D., Mittelbronn M., Gutwein P. (2011) PAX2 regulates ADAM10 expression and mediates anchorage-independent cell growth of melanoma cells. PLoS One 6, e22312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Lammich S., Buell D., Zilow S., Ludwig A. K., Nuscher B., Lichtenthaler S. F., Prinzen C., Fahrenholz F., Haass C. (2010) Expression of the anti-amyloidogenic secretase ADAM10 is suppressed by its 5′-untranslated region. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 15753–15760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Moss M. L., Bomar M., Liu Q., Sage H., Dempsey P., Lenhart P. M., Gillispie P. A., Stoeck A., Wildeboer D., Bartsch J. W., Palmisano R., Zhou P. (2007) The ADAM10 prodomain is a specific inhibitor of ADAM10 proteolytic activity and inhibits cellular shedding events. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 35712–35721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Gatta L. B., Albertini A., Ravid R., Finazzi D. (2002) Levels of β-secretase BACE and α-secretase ADAM10 mRNAs in Alzheimer hippocampus. Neuroreport 13, 2031–2033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Misawa A., Katayama R., Koike S., Tomida A., Watanabe T., Fujita N. (2010) AP-1-dependent miR-21 expression contributes to chemoresistance in cancer stem cell-like SP cells. Oncol. Res. 19, 23–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Zhu Q., Wang Z., Hu Y., Li J., Li X., Zhou L., Huang Y. (2012) miR-21 promotes migration and invasion by the miR-21-PDCD4-AP-1 feedback loop in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol. Rep. 27, 1660–1668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Galardi S., Mercatelli N., Farace M. G., Ciafrè S. A. (2011) NF-κB and c-Jun induce the expression of the oncogenic miR-221 and miR-222 in prostate carcinoma and glioblastoma cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, 3892–3902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Zhu X., Raina A. K., Rottkamp C. A., Aliev G., Perry G., Boux H., Smith M. A. (2001) Activation and redistribution of c-jun N-terminal kinase/stress activated protein kinase in degenerating neurons in Alzheimer's disease. J. Neurochem. 76, 435–441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Estus S., Zaks W. J., Freeman R. S., Gruda M., Bravo R., Johnson E. M., Jr. (1994) Altered gene expression in neurons during programmed cell death. Identification of c-jun as necessary for neuronal apoptosis. J. Cell Biol. 127, 1717–1727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Ham J., Babij C., Whitfield J., Pfarr C. M., Lallemand D., Yaniv M., Rubin L. L. (1995) A c-Jun dominant negative mutant protects sympathetic neurons against programmed cell death. Neuron 14, 927–939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Bozyczko-Coyne D., Saporito M. S., Hudkins R. L. (2002) Targeting the JNK pathway for therapeutic benefit in CNS disease. Curr. Drug Targets CNS Neurol. Disord. 1, 31–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]