Background: Small ubiquitin-like modifiers (SUMO) are covalently conjugated to other proteins including nuclear receptors leading to modification of various cellular processes.

Results: Ligand-dependent SUMOylation of farnesoid X receptor (FXR) negatively regulates the expression of its target genes.

Conclusion: SUMO modification attenuates the capacity of FXR to function as a transcriptional activator.

Significance: Defining post-translation modification of FXR by SUMO is important to understanding how this nuclear receptor functions in health and disease.

Keywords: ABC Transporter, Chromatin Histone Modification, Gene Regulation, Gene Transcription, Nuclear Receptors, Cholestasis, Histone Modifications, Bile Acid Transporters

Abstract

The farnesoid X receptor (FXR) belongs to a family of ligand-activated transcription factors that regulate many aspects of metabolism including bile acid homeostasis. Here we show that FXR is covalently modified by the small ubiquitin-like modifier (Sumo1), an important regulator of cell signaling and transcription. Well conserved consensus sites at lysine 122 and 275 in the AF-1 and ligand binding domains, respectively, of FXR were subject to SUMOylation in vitro and in vivo. Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis showed that Sumo1 was recruited to the bile salt export pump (BSEP), the small heterodimer partner (SHP), and the OSTα-OSTβ organic solute transporter loci in a ligand-dependent fashion. Sequential chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP-ReChIP) verified the concurrent binding of FXR and Sumo1 to the BSEP and SHP promoters. Overexpression of Sumo1 markedly decreased binding and/or recruitment of FXR to the BSEP and SHP promoters on ChIP-ReChIP. SUMOylation did not have an apparent effect on nuclear localization of FXR. Expression of Sumo1 markedly inhibited the ligand-dependent, transactivation of BSEP and SHP promoters by FXR/retinoid X receptor α (RXRα) in HepG2 cells. In contrast, mutations that abolished SUMOylation of FXR or siRNA knockdown of Sumo1 expression augmented the transactivation of BSEP and SHP promoters by FXR. Pathways for SUMOylation were significantly altered during obstructive cholestasis with differential Sumo1 recruitment to the promoters of FXR target genes. In conclusion, FXR is subject to SUMOylation that regulates its capacity to transactivate its target genes in normal liver and during obstructive cholestasis.

Introduction

Small ubiquitin-like modifiers (or SUMO)2 are a family of small proteins, ∼100 amino acids in length and 11–15 kDa in mass, that are covalently, but reversibly attached to other proteins in cells similar to ubiquitin, leading to modification of various cellular processes such as transcription, nuclear-cytosolic localization, mitochondrial activity, DNA repair, and the stress response (1–4). In contrast to ubiquitin, SUMO proteins are generally not used to mark their substrates for degradation. SUMOylation of transcriptional coactivators (e.g. SRC-2, p300), corepressors (NCoR, RIP140), and even nuclear receptors themselves has usually been correlated with impaired transcriptional activation and/or transcriptional repression (5, 6).

The Sumo family consists of four members in vertebrates, Sumo1, the closely related Sumo2/Sumo3, and Sumo4. Sumo2/3 but not Sumo1 can form polymeric chains, thus suggesting distinct regulatory roles for these modifications (7). It is unclear whether Sumo4 is conjugated to other proteins. Sumoylation leads to the formation of an isopeptide bond between the C-terminal glycine residue of the modifier protein and the ϵ-amino group of a lysine residue in the acceptor protein (3). The SUMO acceptor lysine residues in substrates often fall within a recognizable consensus motif that is most commonly ψKXE (where ψ is a large hydrophobic amino acid residue, K is an acceptor lysine, X is any amino acid, and E is an acidic residue)(8). SUMO conjugation can sometimes occur at acceptor lysines that are not within a recognizable consensus sequence, and may preferentially involve modification by Sumo2/3 through poorly defined mechanisms (3).

SUMOylation occurs by a three-step enzymatic cascade of activating, conjugating, and ligating enzymes (3, 6). SUMO proteins are transcribed as immature precursors, which needs to be cleaved by a SENP (sentrin/SUMO-specfic protease) protease to expose a C-terminal diglycine motif. The SUMO-specific E1 activating enzyme heterodimer Sae1/2 activates SUMO at its C terminus through an ATP-dependent process. The resulting SUMO-adenylate conjugate is an intermediate in the formation of a thioester bond between the C-terminal carboxyl group of SUMO and the catalytic Cys residue of Sae2. Next, SUMO is transferred to the catalytic Cys residue of the E2 enzyme Ubc9, forming a thioester linkage between the catalytic Cys residue of Ubc9 and the C-terminal carboxyl group of SUMO. In the final step, activated SUMO is conjugated to a specific lysine residue in the substrate by a single E2-conjugating enzyme, Ubc9. In this process an isopeptide bond is formed between the C-terminal Gly residue of SUMO and a Lys side chain of the target protein. SUMO E3 ligases catalyze the specific transfer of SUMO from UBC9 to its substrate. There are a number of different SUMO ligases (E3s) such as the protein inhibitors of activated STAT1 (PIAS) family (6). SUMOylation is a reversible and dynamic process through the action of SUMO proteases that function as isopeptidases to deconjugate SUMO from substrates (7).

There is increasing evidence that transcriptional activities of many nuclear receptors such as the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ-coactivator-1 (PGC-1α), the estrogen receptor α, the androgen receptor, retinoid X receptor α (RXRα) and retinoid-related orphan receptor α, can be regulated by their direct SUMOylation (9–12). Because several classic SUMO consensus sites were identified in the AF-1 and ligand binding domains of the bile acid receptor FXR, we determined whether ligand-induced SUMOylation is important for regulation of this nuclear receptor in a liver cell line, in normal mouse liver, and during cholestasis after bile duct ligation.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cells and Cell Culture

The liver cell line HepG2 and the monkey kidney cell line CV-1 were used. HepG2 cells were cultured in minimum essential media (MEM) with fetal bovine serum (FBS) and antibiotics. CV1 cells were cultured in DMEM with 10% FBS and antibiotics. All cells were grown in 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator maintained at 37 °C. All cell lines were obtained from American Tissue Culture Collection.

Chemicals

All chemicals were obtained from Sigma, unless stated otherwise. siRNAs for Sumo1 was obtained from Dharmacon (siRNA1) and Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (siRNA2). Antibodies to Sumo1 (ab32058), Sumo2 (ab81371), Pias1 (ab32219), and Ubc9 (ab75854) were from Abcam. FXR (sc-25309) and GFP (sc-8334) antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA.

Plasmid Constructs

The human bile salt export pump (BSEP) promoter sequence was generated by PCR and subcloned into the luciferase expression vector pSV0ALΔ5′(p-1445/Luc), as described by us previously (13, 14). Plasmids encoding FXR and RXRα were generously supplied by Dr. David Mangelsdorf, Dallas, TX. 3XFXRE-TK-Luc (FXRE sequence from the rat Bsep promoter) was constructed by cloning three copies of the FXRE upstream of the minimal thymidine kinase (TK) promoter and the luciferase opening reading frame. SHP promoter plasmid generated from genomic DNA by PCR was further subcloned into the PGL3 and PXP2 vectors (KpnI-XhoI). Expression plasmids for pcDNA3-HA-Sumo1, pSG5-His-Sumo1, pEYFP Sumo1, and SRa-HA-Sumo2 were obtained from Addgene, Cambridge, MA.

The bacterial expression vectors pGEX-6P-1 and pET-28a(+) were used to produce glutathione S-transferase (GST) and histidine-fused recombinant proteins in Escherichia coli, as previously described (15). The different mutants of FXR or the full coding sequence of human FXR were amplified by PCR and cloned in-frame into the BamHI/XhoI sites of the pGEX-6P-1 fusion vector to produce the plasmid pGEX-6P-1-FXR. FXR full-length and mutant forms of FXR were also cloned in-frame into the BamHI/NotI sites of the pET-28a(+) histidine fusion vector. All of the positive clones containing cDNA inserts were identified by restriction enzyme mapping and sequenced using the ABI automated DNA sequencer model 377. Recombinant proteins were expressed in E. coli BL21RP under isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside induction and affinity purified on glutathione S-Sepharose columns. Nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid beads were used for the histidine-tagged protein.

Point mutations were introduced into FXR cDNAs using a QuikChange Site-directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) and appropriate mutant oligos (Table 1). Mutants were confirmed by nucleic acid sequencing. Upon transfection into mammalian cells, the mutagenized cDNAs produced FXR variants with the desired AA substitutions.

TABLE 1.

Primers used for mutation analysis

| Primer name | Direction | Sequence 5′–3′ |

|---|---|---|

| hFXR-K122RM | Forward | agc agg gag gat ccg agg gga tga gct gtg tgt tg |

| Reverse | caa cac aca gct cat ccc ctc gga tcc tcc ctg ct | |

| hFXR-K213RM | Forward | tga gaa aaa atg tgc ggc agc atg cag atc ag |

| Reverse | ctg atc tgc atg ctg ccg cac att ttt tct ca | |

| hFXR-K275RM | Forward | caa ata aaa ttt tac gag aag aat tca gtg cag a |

| Reverse | tct gca ctg aat tct tct cgt aaa att tta ttt g | |

| hFXR-E277AM | Forward | caa ata aaa ttt taa aag aag cat tca gtg cag a |

| Reverse | tct gca ctg aat gct tct ttt aaa att tta ttt g | |

| hFXR-K376RM | Forward | agt att ggg gaa ctg cga atg act caa gag gag tat g |

| Reverse | cat act cct ctt gag tca ttc gca gtt ccc caa tac t | |

| hFXR-I388A/L391AM | Forward | ctg ctt aca gca gct gtt atc gcg tct cca gat aga ca |

| Reverse | tgt cta tct gga gac gcg ata aca gct gct gta agc ag |

Common Bile Duct Ligation

Common bile duct ligation in C57Bl/6 mice was performed as described previously using a protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of University of Colorado, Denver, CO. Briefly, laparatomy was performed on the mice following which bile duct was ligated proximally and distally and severed in the middle (16). Serum bile acids were estimated by a kit from Trinity Biotech to ensure that successful cholestasis was achieved (data not shown). Sham surgery was performed on control mice in which laparatomy and manipulation of the liver was performed, but the bile duct was not ligated. Livers from sham-operated and bile duct-ligated mice were collected at 3 days post-ligation. All animals received humane care according to the criteria outlined in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals prepared by the National Academy of Sciences and published by the National Institutes of Health.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Analysis of Cultured Cell Lines and Mouse Liver

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays were done by a combination of previously described protocols and manufacturer's instructions using the EZ ChIP/MagnaChIP G kit from Upstate Biotechnology/Millipore (Millipore, MA) (15, 17). Briefly, cells from 4 × 100-mm culture dishes were harvested after fixation with 1% formaldehyde. Following lysis, genomic DNA were sonicated in Diagenode Bioruptor Sonicator for 8 × 30 s (twice, with 30 s on/30 s off cycles) resulting in DNA fragments of 200–1,000 bp. The fragmented DNA was diluted in ChIP dilution buffer and preabsorbed with Protein G-Sepharose/salmon sperm DNA (Millipore, MA) for 1 h at 4 °C. Then 5% of the chromatin was removed and saved as input. It was then incubated overnight at 4 °C with 3–5 μg of the appropriate antibodies or normal mouse IgG (control). Antibody-chromatin complexes were captured by incubation with Protein G-Sepharose and centrifuged. Protein G-Sepharose beads were washed with low salt, high salt, lithium chloride, and finally with Tris-EDTA buffer. DNA from the beads was then eluted. Reversal of protein cross-linking and proteinase K digestion, followed by purification of the DNA, was then achieved. An aliquot of the DNA (2 μl) was used in a PCR (standard and quantitative) using specific primers flanking the FXRE site of human BSEP, human SHP, and human OSTα and OSTβ promoters. Primers flanking a site distant from the FXRE site were used as negative controls. PCR products were run in a 2% agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide to confirm the amplicon size. ChIP primers and negative binding site control primers used in the studies are provided in Tables 2 and 3, respectively.

TABLE 2.

Primers used in ChIP analysis

Primers used in ChIP analysis for BSEP/Bsep, SHP/Shp, OSTα/Ostα, and OSTβ/Ostβ are listed in this table.

| Gene name | Direction | Sequence 5′–3′ |

|---|---|---|

| hBSEP | Forward | ggg ttt ccc aag cac act ctg tgt tt |

| Reverse | gag gaa gcc aga gga aat ggt gg | |

| hSHP | Forward | atg ggg aca cct gct gat tgt g |

| Reverse | gcc acc tgc cgc tca ctc agc t | |

| hOSTα | Forward | agt tca ggg ctt tgg gta att aaa c |

| Reverse | ggt gga ggt cag gga agg aag a | |

| hOSTβ | Forward | gaa agt cag gtg gag cct gtt tgc act |

| Reverse | acc cat ctg gta gct ctg gcc tta gca c | |

| mBsep | Forward | ggt ccc cac gca ctc tgg gtt |

| Reverse | gtc ctc ttc cgc tca gac gcc act g | |

| mShp | Forward | gca tca ata gaa aca gca gtc cca agg ca |

| Reverse | cac agg gcc acc tgc cca ctg cct | |

| mOstα | Forward | agt cta aag tcc agg gct gtg ag |

| Reverse | agc tac ctc att cct gag gtg | |

| mOstβ | Forward | gtg agt caa gtg gag tca gtt tgt cac t |

| Reverse | gcc cat ttg gta act ctg ccc tta gca |

TABLE 3.

Primers used in control ChIP analysis

Primers used in contol ChIP analysis for BSEP/Bsep, SHP/Shp, OSTα/Ostα, and OSTβ/Ostβ are listed.

| Gene name | Direction | Sequence 5′–3′ |

|---|---|---|

| hBSEP | Forward | aag cac tgg ccc atc aat tg |

| Reverse | ctc cta agg tgt aac aac t | |

| hSHP | Forward | act gga atc aga gga gga ggc |

| Reverse | acc ttg ggg ccc tgc ttc tgt tgt c | |

| hOSTα | Forward | atg ggc cgg cct cca ggc ag |

| Reverse | tgg gag acc cca gga gag acc ggc a | |

| hOSTβ | Forward | gtc ata ttt tac agc tcc ttg tga |

| Reverse | gtg ccc act cca ggt ctc tat | |

| mBsep | Forward | ctc gag att tca cac aag tct aac aac t |

| Reverse | gtt cct gaa atg agg tta gtt | |

| mShp | Forward | agg gac ctg gct ccc ttc cct g |

| Reverse | agg agc cag cca gga agc tgg c | |

| mOstα | Forward | tag atg tgg agc ctt gat gag c |

| Reverse | atg gta cag atg gat gga g | |

| mOstβ | Forward | tgg gcc tgc ttc ctc ctc |

| Reverse | cag gaa gga gtc aag gct ct |

The method for in vivo ChIP analysis of liver has been modified from protocols for cells (16, 18). In brief, mouse livers were sliced to small pieces and then incubated with 1% formaldehyde to cross-link proteins to DNA in cells. Following this incubation, excess formaldehyde was quenched by incubation with glycine. Nuclear extracts were prepared from cross-linked livers after isolation of nuclei. Extracts were sonicated with the appropriate power setting to shear DNA to ∼500 bp fragments for use in ChIP.

Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using the QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR Kit (Qiagen) in combination with primers for Bsep, Shp, or Sumo1 (primer information in Table 4) in a Step One Plus Real-time PCR system (ABI, CA), as previously described (16). Primers were designed using Primer Express analysis software (ABI) and dissociation curves after each set of primer use were checked to verify that a single PCR amplicon was obtained and no primer dimers were formed. PCR products were also run on agarose gels to further check the amplicon size. PCR were monitored in real-time using SYBR Green dye detection. ChIP DNAs were quantified by real-time PCR and normalized to input DNA (5% input before ChIP). Differential Ct values from experimental and input DNAs (ΔCt) were used to calculate the amplified DNA yield for each experiment. ChIP with IgG (negative control) did not show a PCR signal within 40 amplification cycles. For each ChIP, the fold-change was calculated relative to the value for dimethyl sulfoxide-treated cells, which was set as 1. Each independent ChIP data point is the average of normalized values from PCR runs in duplicate wells. Each histogram is the average mean ± S.E. from independent ChIP experiments of n = 3. RT-PCR was performed at the University or Colorado Denver Endocrinology-PCR core facility. Chromatin Re-ChIP was performed according to the Active Motif Re-ChIP-IT method.

TABLE 4.

Primers used for quantitative PCR analysis

List of primers used in real-time PCR are provided.

| Gene name | Direction | Sequence 5′–3′ | Accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|

| hBSEP | Forward | aca tgc ttg cga gga cct tta | NM003472 |

| Reverse | gga ggt tcg tgc acc agg ta | ||

| hSHP | Forward | agg cct cca agc cgc ctc cca cat tgg gc | NM021969 |

| Reverse | gca ggc tgg tcg gaa act tga ggg t | ||

| hSUMO1 | Forward | aga tca gat tca ggt tcg acg | U67122 |

| Reverse | act gtg ccc tgc cag gct gct ctc |

SUMOylation of FXR in Vitro and in Vivo

In vitro SUMO modification was carried out with purified recombinant products provided by SUMOlink kit (Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA) and FXR purified proteins generated by either GST- or His-tagged proteins from E. coli (19, 20). Reaction products were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and used with the appropriate antibody to detect the SUMOylated protein.

In vivo SUMOylation was carried out using lysate from HepG2-transfected cells. HepG2 cells were transfected with GfpN2/Fxrwt, GfpN2/Fxr K122R/L275R/E277A mutant expression vectors, and/or pSG5-His-Sumo1 expression vectors (20). After 24 h, cells were treated with the FXR ligand GW4064. After 48 h, cells were lysed in denaturating conditions with guanidinium HCl. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and subsequently analyzed by Western blotting using anti-GFP and anti-Sumo1 antibodies. β-Actin antibody was used as a control. A in vivo SUMOylation experiment was also done using the GfpN2/Fxr I388A/L391A mutation that abolishes the potential sites form SIMs (SUMO interaction motifs) in the FXR gene.

Coimmunoprecipitation

Coimmunoprecipitations from GFP/FXR and Sumo1-transfected HepG2 cells were performed with total cell lysates. Cell lysates prepared in IP buffer (50 mm Tris, pH 8, 150 mm NaCl, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 5 mm EDTA plus protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Applied Biosciences)) were precleared with protein A-agarose beads for 30 min and incubated overnight with anti-FXR antibody (D-3; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-Sumo1 antibody (Abcam), or mouse IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at 4 °C. The bead-bound immunoprecipitates were captured by centrifugation at 2,500 × g, washed twice with IP buffer, and then dissociated from the beads, after which the recovered supernatant (using 2× Laemmli's sample buffer at 98 °C) was used for Western blot analysis after fractionation on 10% SDS-PAGE. For the immunoblot, GFP (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and Sumo1 antibodies were used to detect the protein.

Fluorescence Microscopy

Indirect immunofluorescence microscopy was carried out as previously described (21). Briefly, indirect immunofluorescence microscopy was performed on a confluent monolayer of transfected cells cultured on glass coverslips. The GFP-fused hFXR plasmid (hFXR-GFP) and GFP/FXR K122R/K275R/E277A mutants were transiently transfected into HepG2 cells. The cells were fixed and permeabilized for 7 min in methanol at −20 °C, followed by rehydration in PBS. After being washed with PBS, the cells on coverslips were inverted onto a drop of VectaShield mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA). Fluorescence was examined with an Olympus IX71 Fluorescence microscope in the Imaging Core Facility Microscopy Center at the University of Colorado Denver, Anschutz Medical Campus.

Transient Transfections and Luciferase Assays

HepG2 and CV1 cells were plated at a concentration of 1 × 105 cells/well in 24-well plates 2 days earlier. They were transfected at day 0 with the human BSEP or SHP promoter at 0.5 μg/well (in triplicate/per group) and also cotransfected with 50 ng of FXR/RXRα and various amounts of SUMO1 expression plasmids in OPTI-MEM (Invitrogen) were indicated. Transfections were carried out using TransIT-LT (Mirus Bio, WI) at a DNA:TransIT ratio of 1:3. On day 1, medium was changed to DMEM without phenol red and with charcoal-adsorbed FBS. FXR ligand GW4064 (1 μm) was added at this time and luciferase activities were measured 24 h later using the Promega kit (Promega, WI). Normalization of transfection efficiencies in the different wells was achieved by cotransfection with pCMV-β galactosidase and assay of galactosidase activity.

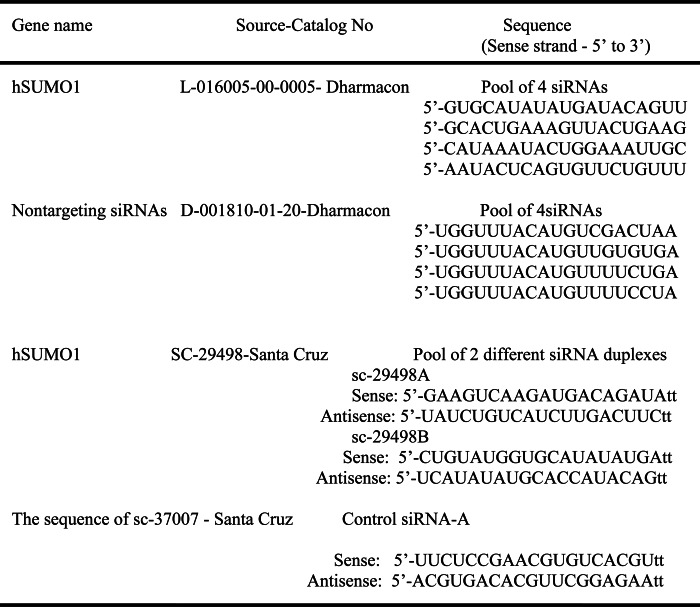

siRNA-mediated Knockdown of Sumo1

siRNAs against Sumo1 obtained from Dharmacon of the siGenome pool and Santa Cruz Biotechnology are listed in Table 5. For knockdown experiments, HepG2 cells were plated in six-well plates (1 × 106 cells/well) and incubated 2 days later with 50 nm siRNA using TransIT-TKO (MirusBio) at a ratio of 1:1 (μl/μl) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Six hours later, medium was added to the wells, and 24 h later, spent medium was replaced with fresh MEM. One day after transfection cells were treated for 24 h with GW4064 (1 μm) or vehicle (0.01% dimethyl sulfoxide). Forty-eight hours later, total RNA was prepared using the TRIzol kit (Invitrogen), and real-time PCR analysis was conducted following conversion of mRNA into cDNA (15).

TABLE 5.

Sequences of RNAs used in this study

Immunoblot Analysis

HepG2 cells were resuspended in gel loading buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 2% SDS, 10% glycerol, 10% β-mercaptoethanol, and 0.1% bromphenol blue). Samples (20 μg, without boiling) were separated by 4–20% gradient SDS-PAGE and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Membranes were blocked with Tris-buffered 5% nonfat milk overnight at 4 °C and then incubated with the relevant antibody (1:2,000 dilutions) overnight at room temperature. The blots were washed three times (5 min each) in Tris-buffered saline/Tween 20 solution (25 mm Tris, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, and 0.1% Tween 20) and incubated with a peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:5,000 dilution) for 1 h at room temperature. The blots were further washed three times (5 min each) in Tris-buffered saline/Tween 20 solution and visualized using the enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (ECL+ Plus; Amersham Biosciences).

Statistics

Calculation of mean ± S.E. and Student's t test was done using Prism software. p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All experiments were repeated at least three times with similar results.

RESULTS

FXR Is Subject to SUMOylation in Vitro and in Vivo

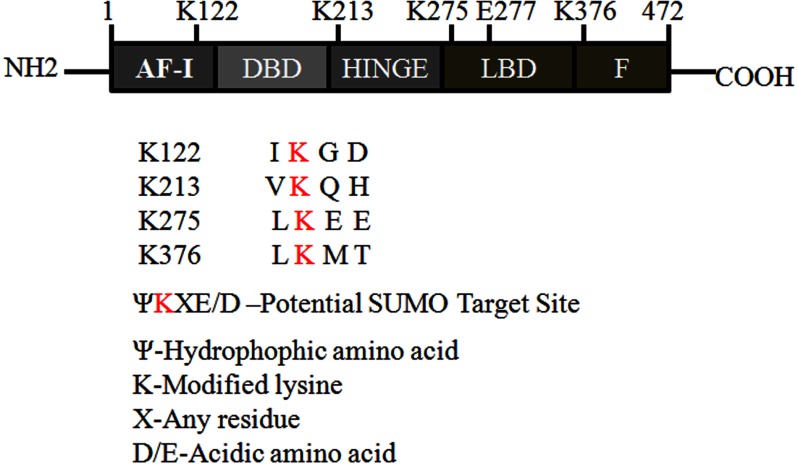

To test whether FXR is targeted for SUMOylation, the SUMOplot algorithm, a web-based tool for prediction of SUMOylation consensus sites was used. The in silico analysis revealed that four lysine residues, Lys122, Lys213, Lys275, and Lys376 fulfilled the minimum criteria for SUMOylation (Fig. 1) (22, 23). In vitro and in vivo methods were then used to determine the extent to which FXR serves as a substrate in the Sumo-conjugation pathway (19).

FIGURE 1.

Potential FXR SUMOylation sites. The protein sequence of hFXR (NM 001206979) was analyzed with the SUMOylation prediction site algorithm, SUMOplotTM prediction. A schematic presentation of the full-length FXR shows potential SUMO target sites (K122, K213, K275, and K376). Numbers correspond to amino acid positions: activation function-1 (AF-1), DNA binding domain (DBD), hinge region (HINGE), and ligand binding domain (LBD) containing AF-2 ligand-dependent transcriptional activity.

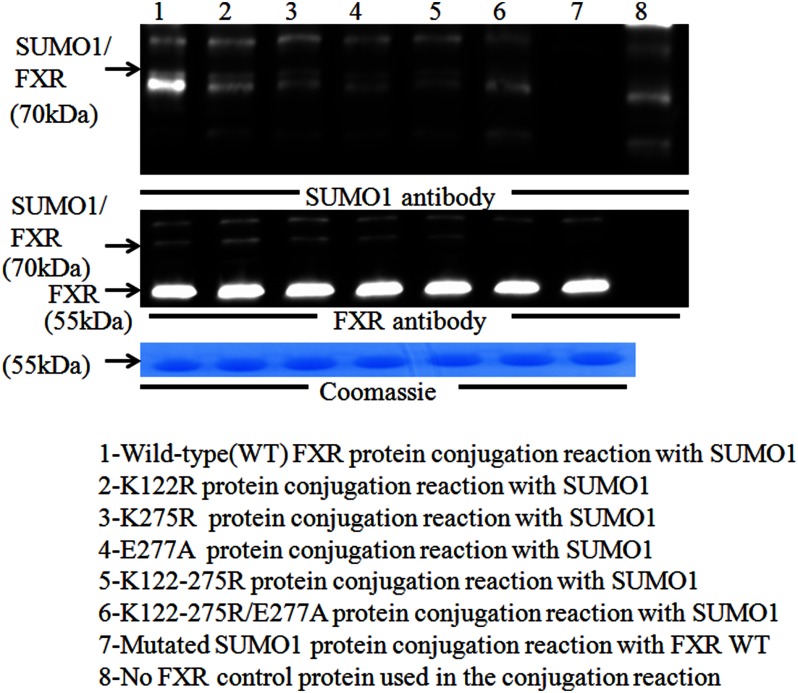

In an in vitro SUMOylation reaction recombinant FXR was shown to be SUMOylated compared with a reaction in which a mutated SUMO protein was used (Fig. 2, lanes 1 and 7). The SUMOylated FXR could be demonstrated with either an FXR or Sumo1 antibody. Because the molecular mass of Sumo1 is ∼15 kDa, the covalent linkage to FXR of ∼55 kDa resulted in the identification of an expected Sumo1-FXR complex of ∼70 kDa. Single point mutations in Lys213 and Lys376 (replaced with arginine using site-directed mutagenesis) did not affect SUMOylation of FXR (not shown). Point mutations were also made in Lys122 and Lys275 (replaced with arginine) with or without mutation of an adjacent Glu277 (replaced with alanine) or all three amino acid residues were mutated together, and then the recombinant FXRs subjected to in vitro SUMOylation. The K112R, K275R, and E277A FXR single mutants were also SUMOylated by Sumo1. However, SUMOylation of FXR was not detected when these three amino acid residues were mutated together or when a mutant Sumo1 protein was used in the reaction (Fig. 2, lanes 6 and 7). The requirement to mutate both the lysine and an adjacent acidic amino acid to inactivate some SUMO consensus sites has been reported previously (11, 24). Thus, Lys122 and Lys275 of FXR serve as the principal attachment sites for Sumo1.

FIGURE 2.

In vitro SUMOylation of FXR. Recombinant wild-type FXR and the various FXR mutant proteins were generated to identify FXR sites subject to SUMOylation. The in vitro SUMO assay contains the specified form of FXR along with the SUMO conjugation machinery (using the Active Motif Kit). Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and the conjugated protein detected by both the anti-Sumo1 and anti-FXR antibodies. Point mutations were made in Lys122 and Lys275 (replaced with arginine) with or without mutation of an adjacent Glu277 (replaced with alanine) or all three amino acid residues were mutated together, and then the recombinant FXRs subjected to in vitro SUMOylation. The K122R, K275R, and E277A single mutants were also SUMOylated by Sumo1. Mutation of two SUMO consensus sites (K122R, K275R, and E277A together) completely abrogated the in vitro SUMOylation of FXR. (lane 6). A control reaction contained the unconjugatable Sumo1 mutant protein provided by the SUMOlink kit or no FXR protein (lanes 7 and 8).

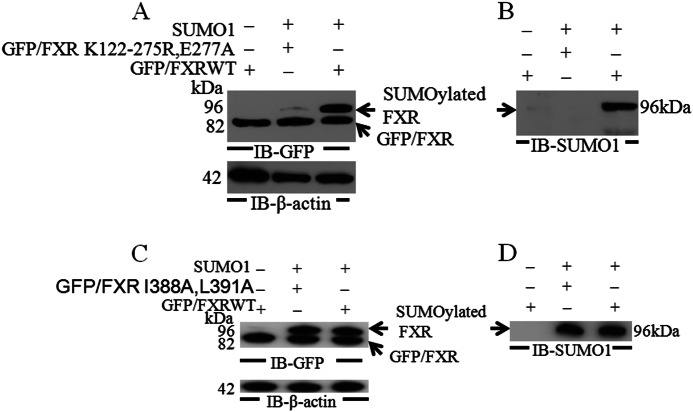

We next determined whether FXR could be SUMOylated in vivo. HepG2 cells were transfected with GFP-FXR or the GFP-FXR triple mutant (K122R/K275R/E277A) with or without overexpression of Sumo1. Western blotting of the cell lysates using an anti-GFP antibody detected a higher molecular weight form representing SUMOylated GFP-FXR (Fig. 3A). In contrast, no SUMOylated form was detected with expression of the GFP-FXR K122R/K275R/E277A mutant (Fig. 3B). Similarly, the SUMOylated GFP-FXR but not the mutant form could be detected with an anti-Sumo1 antibody.

FIGURE 3.

In vivo SUMOylation of FXR. HepG2 cells were transfected with GFPN2/FXRWT, the mutant GFPN2/FXR (K122R, K275R, and E277A), or the GFPN2/FXR I388A,L391A (SIM mutant) and pSG5-His-Sumo1 expression vectors. After 48 h, cells were lysed in denaturating conditions with guanidinium HCl. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and SUMOylated proteins were analyzed by Western blotting using anti-GFP and anti-Sumo1 antibodies. β-Actin antibody was used as a loading control. In A and C a higher molecular mass form was detected with anti-GFP antibody. In B and D the SUMOylated FXR was recognized by an anti-SUMO antibody. The wild-type, but not the triple FXR mutant, was SUMOylated (A and B). Mutagenesis of a consensus SUMO-interacting motif (SIM of amino acids Ile388 and Leu391 to alanine (I388A and L391A)) in FXR had no effect on in vivo SUMOylation of the mutant FXR (C and D). Both wild-type and SIM mutant were SUMOylated (C and D). IB, immunoblot.

We also identified a consensus SIMs in FXR-(388–391) (Ile388, Val389, Ile390, and Leu391 where positions two and three can be any amino acid). In some cases noncovalent binding of SUMO to a SIM precedes and may be required for SUMO conjugation to a SUMO conjugation site (25, 26). In this case mutagenesis of amino acids Ile388 and Leu391 in FXR to alanine (I388A and L391A), which in other studies was sufficient to disrupt the SIM, had no effect on in vivo SUMOylation of the mutant FXR (Fig. 3, C and D).

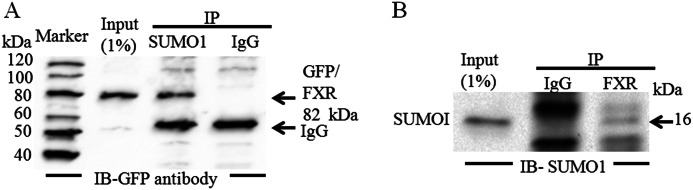

Interaction of FXR and Sumo1

We next determined whether FXR and Sumo1 directly interact with each other by co-immunoprecipitation. Sumo1 and FXR-GFP expression constructs were transfected into HepG2 cells 1 day before collecting the cells. When Sumo1 was immunoprecipitated from a whole cell lysate of HepG2 cells, FXR association with Sumo1 was demonstrated on Western blot analysis with a GFP/FXR antibody (Fig. 4A). FXR also coimmunoprecipitated with Sumo1 from a HepG2 cell lysate when FXR was first immunoprecipitated, run on a Western blot, and probed with a Sumo1 antibody (Fig. 4B). These data further support the association between Sumo1 and FXR. However, as we show in Fig. 3, C and D, this noncovalent association though a SUMO-interacting motif was not required for SUMOylation of FXR.

FIGURE 4.

Sumo1 associates with FXR in vivo. HepG2 cells were transiently co-transfected with the FXR-GFP and Sumo1 constructs 1 day before collecting the cells. A, when SUMO1 was immunoprecipitated from a whole cell lysate of HepG2 cells, association was demonstrated with FXR on Western blotting with a anti-GFP antibody. B, FXR-GFP was also coimmunoprecipitated with Sumo1 from a HepG2 cell lysate when FXR was first immunoprecipitated, run on a Western blot, and probed with a Sumo1 antibody. The input lysate was at 1% of the lysate used for immunoprecipitation (IP). IB, immunoblot.

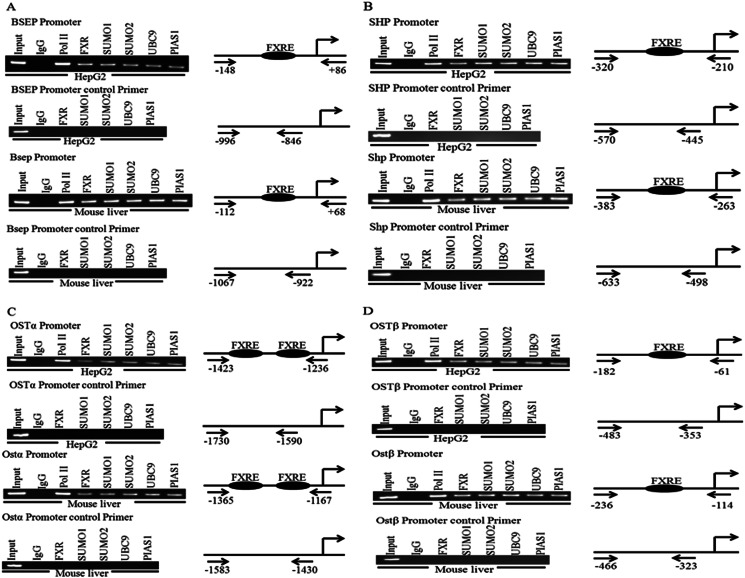

Expression of Sumo1 and Sumo2 in HepG2 Cells and in Mouse Liver

Although FXR can be SUMOylated in vitro and in vivo, these experiments did not determine whether the SUMO proteins are localized to promoters of FXR target genes. ChIP analysis showed the presence of Sumo1 and Sumo2 at the promoters of FXR target genes BSEP/Bsep, SHP/Shp, OSTα/Ostα, and OSTβ/Ostβ, in both the HepG2 liver cell line and mouse liver (Fig. 5). Moreover, the SUMO E2-conjugating enzyme Ubc9 and Pias1 ligase could also be detected.

FIGURE 5.

Chromatin recruitment of Sumo1 and Sumo2 to the promoters of FXR target genes. ChIP analysis of hepatoma cells (HepG2) and mouse liver showed recruitment of endogenous FXR, Sumo1, Sumo2, Ubc9, and the Pias1 to the BSEP/Bsep (A), SHP/Shp (B), OSTα/Ostα (C), and OSTβ/Ostβ (D) promoters. Schematic representation of the primers used for ChIP and the location of the sites on the BSEP/Bsep, SHP/Shp, OSTα/Ostα, and OSTβ/Ostβ promoters are shown in the right panel of the representative gels. A ChIP with a negative binding site control is shown for each FXR target gene promoter.

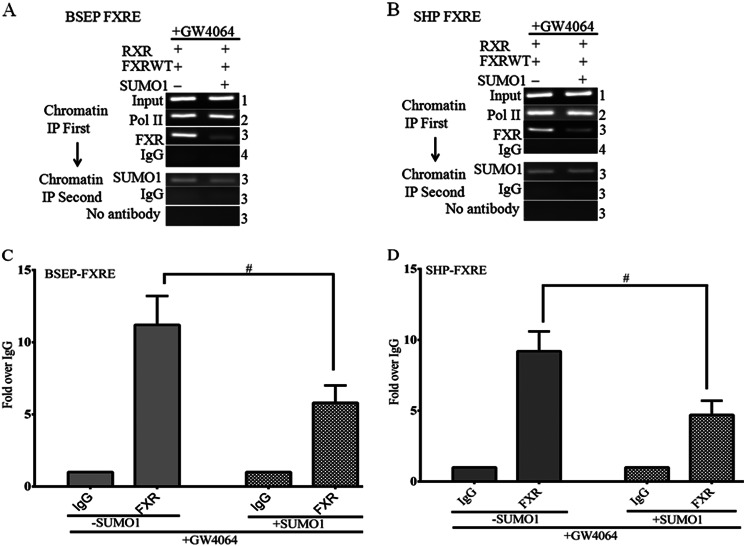

Next, we performed a ChIP Re-ChIP assay that is a direct strategy to determine the in vivo colocalization of proteins interacting or in close proximity on the basis of double and independent rounds of immunoprecipitations using antibodies against FXR and Sumo1 (Fig. 6). The ChIP Re-ChIP assay was done using chromatin prepared from HepG2 cells transfected with FXR and RXRα with and without overexpression of Sumo1 in the presence of the FXR ligand GW4064. Fig. 6, A and B, confirm that FXR and Sumo1 occupy the same genomic site (FXRE) in vivo at both the BSEP and SHP loci. Quantitative RT-PCR demonstrates that significantly less FXR is recruited to the BSEP and SHP FXREs with overexpression of Sumo1 (Fig. 6, C and D).

FIGURE 6.

FXR and Sumo1 occupy the same genomic locus at the SHP and BSEP promoters. Sequential chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP Re-ChIP) confirms that FXR and Sumo1 occupy the same genomic site (FXRE) in vivo at both BSEP and SHP loci (A and B). ChIP-reChIP was done using chromatin prepared from HepG2 cells transfected with FXR, RXRα, and Sumo1. A shows PCR results using the BSEP primer that includes the FXR binding site. Fig. 5B shows PCR results using the SHP primer that includes the FXR binding site. The lane numbers are the same in each panel to indicate that the DNA is from the same chromatin sample. The upper panel shows the PCR results performed on an aliquot of DNA removed from the experiment after the first ChIP assay. The bottom panel represents PCR results using DNA from chromatin samples after both ChIP steps. Chromatin samples subjected to the first ChIP using FXR antibody (upper panel, lane 3) were then subjected to a second ChIP with a Sumo1 antibody (bottom panel, lane 3). In the bottom panel mouse IgG and no antibody controls were also performed from the first ChIP using FXR antibody (lane 3). C and D, quantitative RT-PCR shows reduced ligand-induced chromatin recruitment of FXR to the promoters of BSEP, and SHP with expression of Sumo1. #, p < 0.001, +Sumo1 compared with −Sumo1.

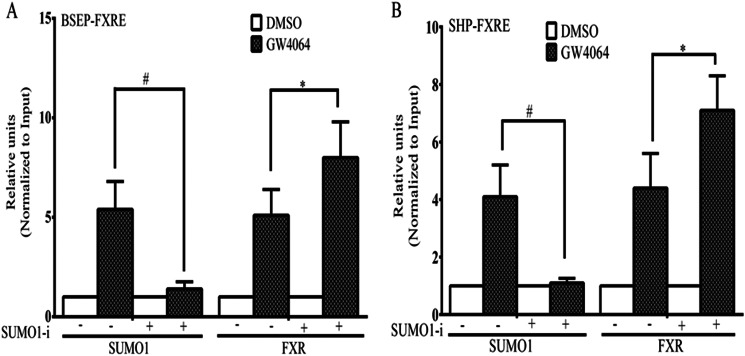

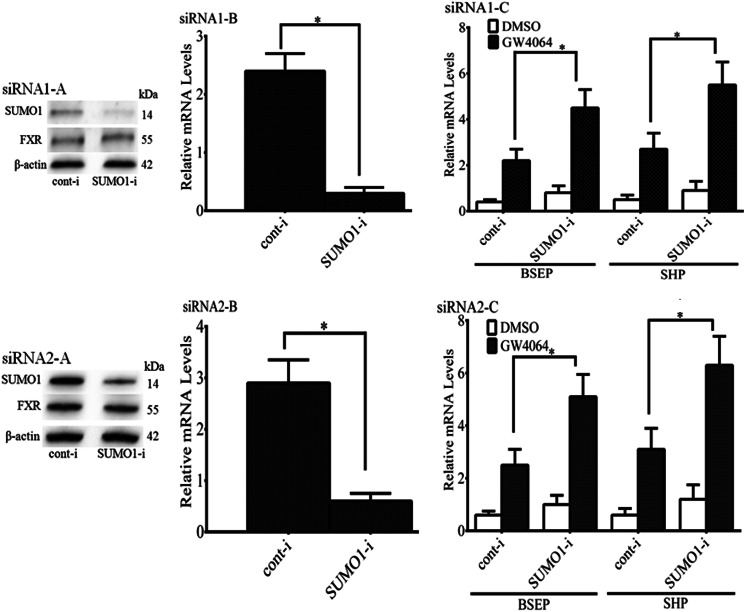

In additional ChIP experiments, siRNA depletion of Sumo1 in HepG2 cells led to a significantly increased occupancy of FXR at the SHP and BSEP promoters, as assessed by quantitative RT-PCR (Fig. 7, A and B). Moreover, with depletion of Sumo1 using 2 distinct siRNA pools, there was a significant increase in Bsep and Shp mRNA levels in HepG2 cells (Fig. 8, A–C).

FIGURE 7.

The effect of siRNA knockdown of Sumo1 expression on ligand-induced occupancy of Sumo1 and FXR at the endogenous BSEP and SHP promoters. siRNA were used to reduce cellular Sumo1 levels with a non-silencing siRNA used as control. Treatment of HepG2 cells with siRNA against Sumo1 markedly increased the ligand-induced occupancy of FXR at the BSEP (A) and SHP (B) promoters and decreased Sumo1 recruitment to these promoters, as assessed by real-time quantitative PCR. Each independent ChIP data point is the average of normalized values from PCR runs in duplicate wells. Each histogram is the average ± S.E. from independent ChIP experiments of n = 3. *, p < 0.05; #, p < 0.001. DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide.

FIGURE 8.

Up-regulation of ligand-induced FXR target gene expression in Sumo1-silenced HepG2 cells. Sumo1 expression was markedly and specifically reduced compared with control in RNAi-transfected cells using two different siRNA pools at both the protein (siRNA1-A or siRNA2-A) and mRNA levels (siRNA1-B or siRNA2-B). Panel C (siRNA1-C or siRNA2-C) shows that Shp and Bsep mRNAs increased significantly, as assessed by real-time quantitative PCR. *, p < 0.05.

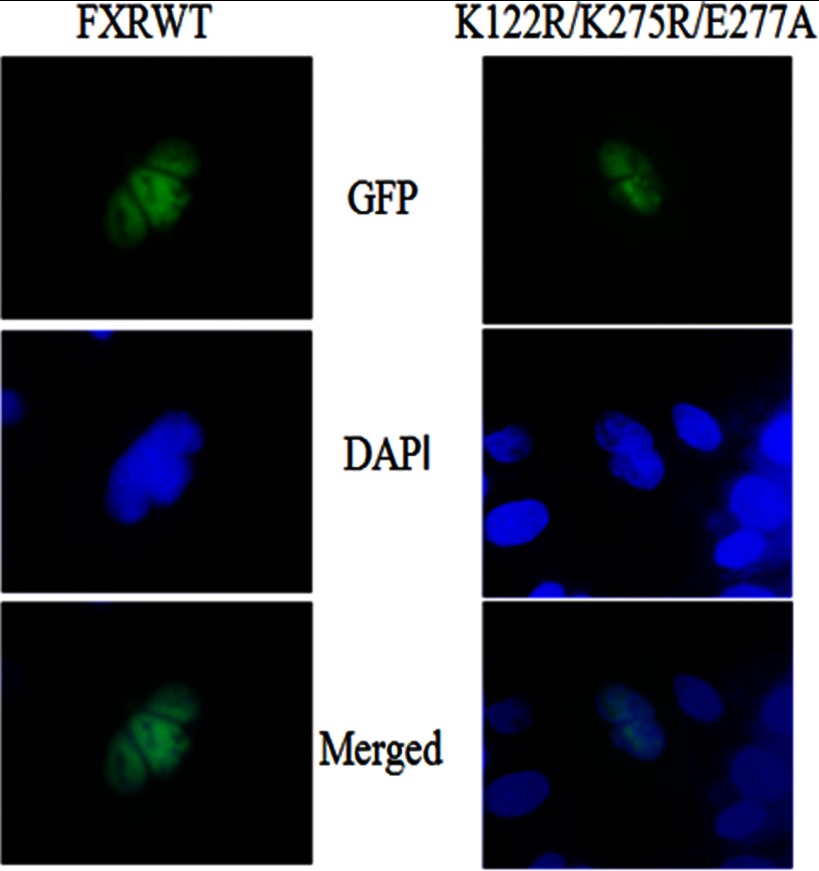

The Effect of SUMOylation on Subcellular Localization of FXR

Because SUMOylation can influence protein targeting and intranuclear localization of nuclear receptors, we compared the subcellular localization of wild-type FXR-GFP to the K122R/K275R/E277A triple FXR-GFP mutant, which cannot be SUMOylated (Fig. 9). Indirect immunofluorescence microscopy of HepG2 cells transfected with wild-type FXR-GFP showed that the protein was predominantly localized throughout the nucleoplasm. The nuclear distribution of the mutant form of FXR-GFP did not differ from the wild-type protein. We conclude the SUMOylation of FXR does not significantly influence its nuclear localization.

FIGURE 9.

Localization of FXR and its mutants by immunocytochemistry and immunofluorescence microscopy. The HepG2 cells, grown on coverslips on 12-well plates, were transfected with GFP/FXR or the mutant FXR. After 24 h of transfection, cells were fixed with 100% methanol at −20 °C for 7 min. Selected images were analyzed for fluorescence subnuclear distribution of HepG2-transfected cells. There was no difference in nuclear localization of the wild-type or mutant form of FXR.

Sumo-1 Expression Represses FXR-mediated Transcriptional Activity

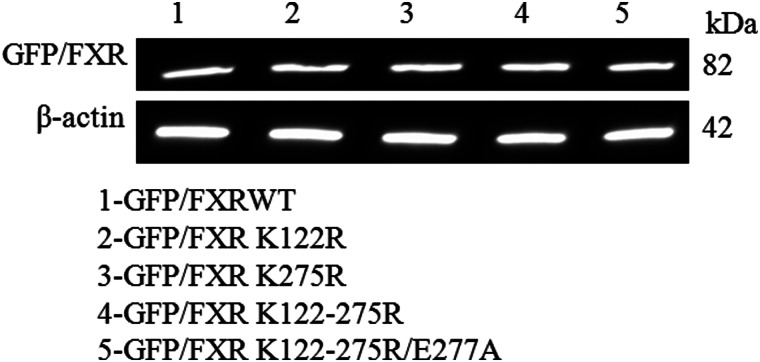

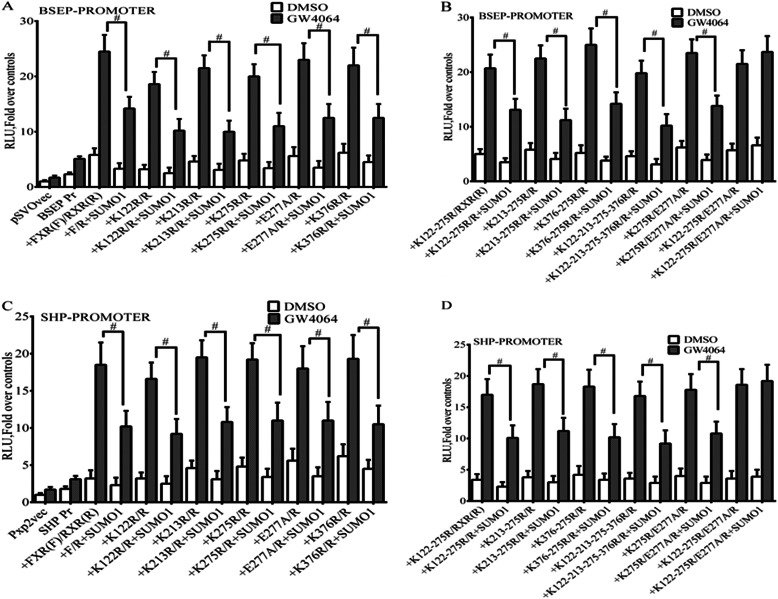

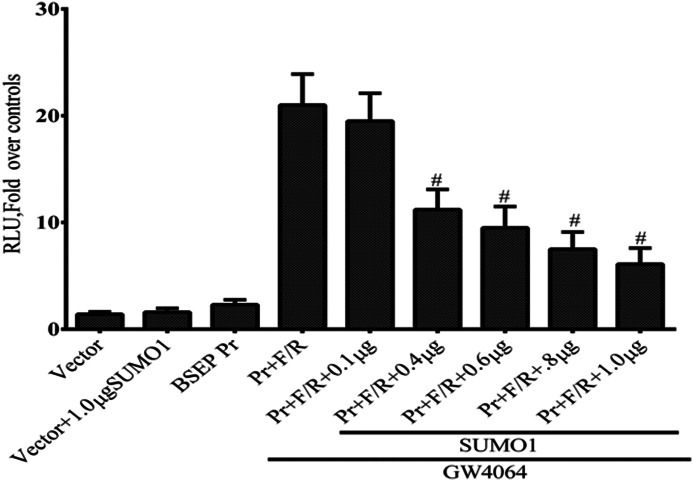

To define the functional and biological relevance of FXR SUMOylation, we next tested how wild-type FXR and various FXR SUMO consensus site mutants effected ligand-induced transactivation of FXR target genes. There was equal expression of wild-type and mutant FXR proteins in Western blots of transfected HepG2 cells (Fig. 10). HepG2 or CV-1 cells were transiently transfected with plasmid vectors containing the BSEP promoter-luciferase DNA or SHP promoter luciferase DNA. As expected, transfection with wild-type FXR/RXRα with the addition of the GW4064 ligand led to a significant increase in BSEP and SHP promoter-luciferase activity in HepG2 cells (Fig. 11, A and C). SUMO1 expression in HepG2 cells significantly repressed luciferase activity associated with the BSEP and SHP promoter-luciferase DNA constructs. Moreover, Fig. 12 shows that when CV-1 cells were transfected with FXR, RXRα, and increasing amounts of full-length SUMO1 cDNA plasmid, suppression of the BSEP promoter-luciferase activity was dose-dependent. Mutation of Lys122, Lys213, Lys275, and Lys376 individually to arginine and Glu277 to alanine or mutation of 2 residues in combination had no effect on the inhibitory activity of Sumo1 (Fig. 11, A and C). In contrast, mutations of Lys123, Lys275, and Glu277 of FXR together completely abrogated the inhibition by Sumo1 of the ligand-induced transactivation of the BSEP promoter-luciferase and SHP promoter (Fig. 11, B and D) constructs. These results and the in vitro and in vivo SUMOylation experiments indicate that the lysine residues, Lys122 and Lys275, within two SUMO consensus sites are involved in regulating FXR target genes.

FIGURE 10.

Protein expression analysis of different FXR point mutations. FXR point mutation constructs are transfected in HepG2 cells to examine the protein expression levels of different FXR mutations. After 24 h transfection cells were lysed with CelLyticTM M mammalian cell lysis/extraction reagent followed by Western blot. β-Actin used as a control. There was no difference in protein expression between wild-type FXR and the various FXR mutants.

FIGURE 11.

The effect of SUMO consensus site mutations on expression of FXR-mediated transcriptional activity. HepG2 cells transfected with the indicated plasmids were treated with FXR ligand GW4064. Reporter assays were performed 48 h after transfection. The mean ± S.E. are shown, n = 3. A–D, Sumo1 expression significantly decreased BSEP and SHP reporter gene activities when co-transfected with FXRWT. Sumo1 expression significantly decreased BSEP and SHP reporter gene activities in all combinations of single or double lysine mutations, which was not observed with expression of the K122R/K275R/E277A FXR triple mutant. #, p < 0.001.

FIGURE 12.

Dose-dependent expression of FXR-mediated transcriptional activity by Sumo1 expression. CV-1 cells were transfected with FXR, RXRα, and increasing amounts of full-length Sumo1 cDNA plasmid. FXR transactivation of the BSEP promoter was monitored by luciferase activity. Significant (p < 0.001 compared with activity in cells without Sumo1 plasmid cotransfection) dose-dependent down-regulation of promoter activity was seen with 0.1 to 1.0 μg of Sumo1 cDNA. *, p < 0.001 compared with transfection in the absence FXR/RXRα. Pr, BSEP promoter; F/r, FXR/RXRα.

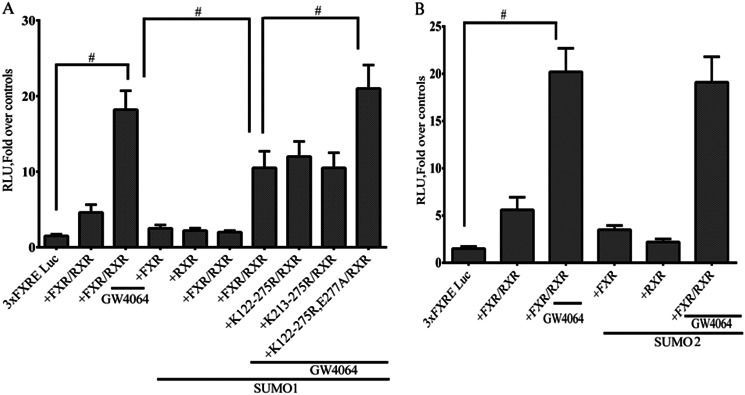

Because HepG2 cells synthesize bile acids and may possibly express low levels of FXR and RXRα, co-transfection assays were also done in CV-1 cells, derived from monkey kidney fibroblasts. Three copies of a consensus FXRE were cloned upstream of the thymidine kinase promoter linked to a luciferase reporter. The chimeric constructs were then transfected into CV-1 cells along with wild-type FXR or the FXR triple mutants with or without overexpression of Sumo1 or Sumo2 (Fig. 13, A and B). As expected, expression of the FXR/RXRα heterodimer in CV-1 cells led to a marked increase in expression of the 3XFXRE-TK-LUC promoter in the presence of GW4064 (Fig. 13A). Overexpression of Sumo1 significantly inhibited ligand-induced transactivation by the wild-type FXR or by FXRs in which pairs of potential SUMOylated lysines were mutated without mutation of Glu277. In contrast, mutation of the two FXR SUMO consensus sites together including the E277A residue (K122R/K275R/E277A) completely abrogated the inhibition by Sumo1 of transactivation of the 3XFXRE-TK-LUC promoter by FXR. In addition overexpression of Sumo2 had no effect on transactivation of the chimeric promoter construct by wild-type FXR (Fig. 13B).

FIGURE 13.

The effect of FXR SUMOylation on expression of a 3XFXRE-TK-luciferase construct. 3XFXRE-TK-Luc was constructed by cloning three copies of the Bsep FXRE upstream of the minimal thymidine kinase (TK) promoter and the luciferase opening reading frame. CV-1 cells in 12-well plates were transfected with 3XFXRE-TK-Luc along with wild-type FXR, RXRα, and Sumo1 or the FXR mutants. A, expression of the FXR-RXRα heterodimer along with Sumo1 in CV-1 cells led to a marked decrease in expression of the 3XFXRE-TK-LUC activity in the presence of GW4064. There was no activity of the promoter observed in the absence of FXR/RXRα. Sumo1 failed to decrease 3XFXRE-TK-LUC activity with expression of K122R/K275R/E277A mutant FXR and RXRα in the presence of ligand. *, p < 0.001 compared with transfection in the absence of FXR/RXRα or with mutant FXR. B, expression of the FXR-RXRα heterodimer along with SUMO2 in CV-1 cells had no effect on expression of 3XFXRE-TK-LUC activity in the presence of GW4064.

The Effect of Common Bile Ligation on Recruitment of SUMO Proteins to the Promoters of FXR Target Genes

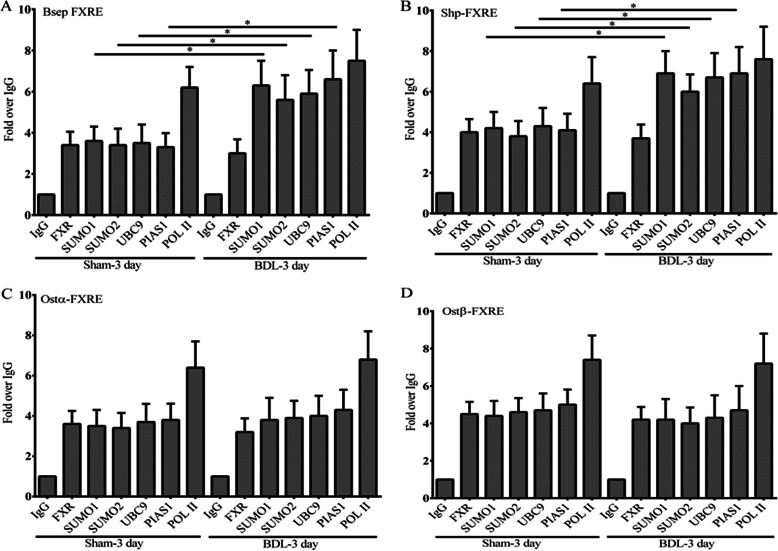

It is well known that many dynamic changes occur in the liver during various forms of experimental and human cholestasis (27, 28). Pathways for biotransfomation and transport involving FXR target genes are often disrupted or undergo adoptive change including down-regulation of the canalicular and basolateral transporters Bsep, Mrp2, and Ntcp, and up-regulation of compensatory transporters such as Ostα-Ostβ. Because ligation of the common bile duct (BDL) in rodents is a well established cholestatic model, we sought to define how pathways for SUMOylation would be altered in this model. ChIP analysis of mouse liver after 3 days of BDL showed a marked increase in recruitment Sumo1, Sumo2, Ubc9, and Pias1 to the promoters of Bsep and Shp compared with sham-operated mice (Fig. 14, A and B). In contrast, there was no change in recruitment of these mediators to the Ostα and Ostβ promoters compared with sham operated mice (Fig. 14, C and D). Because SUMOylation usually inhibits transcriptional activity, this differential recruitment to the promoters of FXR target genes may be important for maintaining the activity of genes required for an adoptive response during cholestasis.

FIGURE 14.

The effect of common bile ligation on recruitment of SUMO proteins to the promoters of FXR target genes. ChIP analysis of the FXRE locus in sham-operated mouse liver and mouse liver after 3 days of CBDL using antibodies to FXR, Sumo1, Sumo2, Ubc9, Pias1, and RNA polymerase II. A and B, there was a marked increase in recruitment of Sumo1, Sumo2, Ubc9, and Pias1 proteins to the promoters of Bsep and Shp, which were plotted as fold-relative to IgG as assessed by quantitative PCR analysis. C and D, there was no change in recruitment of these mediators to the Ostα and Ostβ promoters compared with sham operated mice. *, p < 0.05, common bile duct ligation compared with sham operated mice.

DISCUSSION

In this study we identified a new post-translational modification of FXR via SUMOylation in the liver that may play a crucial role in the regulation of hepatic function. FXR could be SUMOylated by Sumo1 in vitro and in vivo and coimmunoprecipitated with Sumo1. We found Sumo1 and Sumo2 to be highly expressed in mouse liver and a liver cell line. ChIP analysis showed that Sumo1 was recruited to the BSEP, SHP, and the OSTα-OSTβ promoters in a ligand-dependent fashion. Sequential chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP-ReChIP) verified the concurrent binding of FXR and Sumo1 to the BSEP and SHP promoters. Overexpression of Sumo1 markedly decreased binding and/or recruitment of FXR to the BSEP and SHP promoters on sequential ChIP assays. Mutation of the well conserved SUMOylation consensus sites at lysines 122 and 275 (along with glutamic acid 277) completely abrogated SUMOylation of FXR. SUMOylation did not have an apparent effect on nuclear localization of FXR. Expression of Sumo1 markedly inhibited the ligand-dependent, transactivation of BSEP and SHP promoters by FXR/RXRα in HepG2 cells. In contrast, Sumo1 expression did not suppress the transactivation of BSEP and SHP promoters by an FXR construct with combined Lys122, Lys275, and Glu277 mutations. Similarly, siRNA knockdown of SUMO1 increased transactivation of the BSEP and SHP promoters in HepG2 cells. Although siRNA knockdown of Sumo1 has a similar effect to mutation of the FXR SUMO consensus sites, depletion of Sumo1 is likely to be less specific, as there are other known SUMOylation targets such as RXRα, p300, and SRC2 whose activity could also be altered. Taken together, these results indicate that lysines 122 and 275 of FXR serve as the principal attachment sites for Sumo1.

We also found that SUMO1 noncovalently binds to FXR. There are several possible explanations for this observation (29). An increasing number of proteins have been shown to bind SUMO or SUMOylated proteins noncovalently through SUMO-interacting motifs. FXR in fact has a SIM consensus site. There are now multiple proteins for which SUMOylation is dependent on the presence of a SIM in the substrate (25, 26). In this scenario SUMO binding to the SIM domain would be the initial association with its target protein and would precede SUMO conjugation to the SUMO consensus motif. However, this possibility was excluded by mutagenesis of the FXR SIM site, which has no effect on in vivo SUMOylation of FXR. Alternatively, there are many transcription factors and coactivators such p300 and steroid receptor coactivators involved with FXR transactivation that are also subject to SUMOylation and likely interact with FXR in both SUMOylated and un-SUMOylated states. The functional significance of this complex regulatory network will require additional studies.

Vavassori and associates (30) recently reported that SUMOylation of FXR only at Lys277 in HEK293 cells was required for FXR-mediated trans-repression of cytokine expression induced by the FXR ligand INT-747. This suggests that there may be tissue-specific differences in the numbers of SUMOylation sites important for regulating expression of FXR target genes.

Our results and previous work indicates the SUMO marks transcriptionally active constitutive and inducible genes. A model for the role of SUMO in active transcription has been developed by Rosonina et al. (31) in yeast and is relevant in interrupting our results. At constitutive gene promoters, SUMOylation of transcription-related factors occurs prior to recruitment to the promoter and facilitates promoter complex assembly and recruitment of polymerase II to the promoter. In this case components of the SUMO machinery would not be found on ChIP analysis at the promoter. In contrast at inducible genes such as those regulated by FXR, SUMOylation likely occurs after ligand binding with recruitment of the SUMO-conjugating enzyme Ubc9 and ligating enzyme PIAS to the promoter of FXR target genes. In this setting SUMOylation has a yet to be defined role in gene activation, but certainly contributes to cessation of transcription and facilitation of another round of transcription. Under conditions of inflammation and injury associated with bile duct ligation the well known role of SUMOylation as a transcriptional repressor may predominate in an adoptive response to cell stress.

In limited studies we did not find a specific role for Sumo2 in regulating FXR target genes involved in hepatobiliary transport. Although Sumo2 could be detected at the loci of BSEP and SHP on ChIP analysis and SUMOylated FXR in vitro (data not shown), its overexpression did not suppress the activity of a FXRE reporter construct. Sumo2 could be involved in modifying co-regulatory proteins and histones such as histone H4, and could be acting in combination with another post-translational modification.

As documented with other NRs, SUMOylation triggers many molecular events that can influence the fate and function of modified NRs at the nongenomic, genomic, and epigenomic levels (3, 5, 6). The demonstration of this post-translational modification of FXR is but a first step in defining its probably complicated physiological role in the hepatocyte. An intriguing and unexplained aspect of the role of SUMOylation in suppressing transcription is that only a minor fraction of a target protein, ∼5%, is subject to SUMOylation under steady state conditions, yet transcription can be dramatically activated if SUMO is depleted by siRNA or SUMO acceptor sites are mutated, as shown by our results (3). The small proportion of SUMOylated substrate detected at any one time may reflect the rapid cycling between states of SUMOylation and deSUMOylation (1). The specific, reversible, and highly dynamic process of SUMOylation may provide an important mechanism contributing to the assembly and disassembly of transcriptional complexes in the liver (2).

In vivo, SUMOylation can influence single or multiple properties of a target protein including its stability, localization, or activity (2). In most cases SUMO modification inhibits transcriptional activity of a NR, as we have now shown with FXR. One mechanism may be through a conformation change in the modified FXR that interferes with its ability to recruit and/or interact with critical coactivators and histone modifying enyzmes on ligand binding. Alternative modifications such as acetylation, methylation, and ubiquitylation may compete for the same site on one or more of the consensus lysine residues (29). Synergistic or antagonistic cross-talk among different types of post-translational modifications can occur and adds to the level of regulatory complexity (32). An important coactivator, SRC2, has been shown to interact with FXR and other NRs in a ligand-dependent manner and enhances transcriptional activity of the receptors via recruitment of additional cofactors such as CBP/p300 and enzymes with acetyltransferase or methyltransferase activity (33). SRC2 is subject to SUMOylation by Sumo1, but at least in the case of its interaction with the androgen receptor, it enhances AR-dependent transcription rather than the more common scenario of transcriptional repression (34). SRC2 is an important coactivator of FXR, but it is unknown how SUMOylation of SRC2 effects the activity of FXR-dependent transcription. However, when Sumo1 is knocked down with siRNA the net effect is to increase transactivation of FXR target genes.

Our results clearly demonstrate that SUMOylation of FXR deceases its presence at the promoters of FXR target genes, possibly by impaired binding to the FXRE and/or by interfering with the ability of FXR to dimerize with its partner, the RXRα. This process is a prerequisite for direct DNA binding and transcriptional activation. RXRα as the obligate heterodimeric partner for FXR is also negatively regulated by SUMOylation (10). For example, there is recent evidence that SUMOylation of LXRα blocks the recruitment of RXRα to loci of LXR target genes (35–37). In addition to interference with interactions with coactivators, SUMOylation of NRs can also recruit corepressors such as RIP40 and the nuclear receptor corepressor-histone deacetylase (HDAC3) complex. Inhibition of corepressor release may also occur in a process called transrepression (4, 36). Further studies will be required to define which of these or other mechanisms are operative in regulating the transcriptional activity of FXR.

Our studies of SUMOylation after common bile duct ligation in the mouse provides some novel insight into the importance of this pathway in a cholestatic disease model. Major changes in SUMOylation of NRs have been well described during cell stress including heat shock and inflammation (37). For example, ligand-induced SUMOylation of LXRα plays an important role in transrepression of the NF-κB-mediated inflammatory response in the liver through blocking of corepressor clearance on gene promoters (4). It is important to recognize that specific targets may be differentially modified by SUMOylation in response to cell injury so that for some substrates the level of SUMOylation may be increased, decreased, or unchanged. It seems likely that enhanced recruitment of SUMO proteins to the Bsep and Shp promoters may attenuate expression of these genes in cholestasis, whereas maintaining the basal amount of SUMO proteins at the Ostα-Ostβ promoters may contribute to the adoptive response well described for these transporters in cholestasis (35, 38).

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the assistance of Ramkumar Balasubramaniyan, a sophomore in Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, for mutations in the FXR gene (2012 summer Pediatric Student Research Program). We also thank Mosaab Esseid, M.D, International Medical Graduate, and Michael Holter, junior in Carleton College, Northfield, MN, volunteers in our lab, for their valuable help in this project.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant DK-084434 from the NIDDK (to F. J. S.).

- SUMO

- small ubiquitin-like modifiers

- PIAS

- protein inhibitors of activated STAT1

- SHP

- small heterodimer partner

- BSEP

- bile salt export pump

- SIM

- SUMO interaction motif

- RXRα

- retinoid X receptor α

- FXR

- farnesoid X receptor

- OST

- organic solute transporter

- NR

- nuclear receptor.

REFERENCES

- 1. Wang Y., Dasso M. (2009) SUMOylation and deSUMOylation at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 122, 4249–4252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Andreou A. M., Tavernarakis N. (2009) SUMOylation and cell signalling. Biotechnol. J. 4, 1740–1752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wilkinson K. A., Henley J. M. (2010) Mechanisms, regulation and consequences of protein SUMOylation. Biochem. J. 428, 133–145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Treuter E., Venteclef N. (2011) Transcriptional control of metabolic and inflammatory pathways by nuclear receptor SUMOylation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1812, 909–918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Geiss-Friedlander R., Melchior F. (2007) Concepts in sumoylation. A decade on. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 947–956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gareau J. R., Lima C. D. (2010) The SUMO pathway. Emerging mechanisms that shape specificity, conjugation and recognition. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11, 861–871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yeh E. T. (2009) SUMOylation and De-SUMOylation. Wrestling with life's processes. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 8223–8227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rodriguez M. S., Dargemont C., Hay R. T. (2001) SUMO-1 conjugation in vivo requires both a consensus modification motif and nuclear targeting. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 12654–12659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yang Y., Tse A. K., Li P., Ma Q., Xiang S., Nicosia S. V., Seto E., Zhang X., Bai W. (2011) Inhibition of androgen receptor activity by histone deacetylase 4 through receptor SUMOylation. Oncogene 30, 2207–2218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Choi S. J., Chung S. S., Rho E. J., Lee H. W., Lee M. H., Choi H. S., Seol J. H., Baek S. H., Bang O. S., Chung C. H. (2006) Negative modulation of RXRalpha transcriptional activity by small ubiquitin-related modifier (SUMO) modification and its reversal by SUMO-specific protease SUSP1. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 30669–30677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rytinki M. M., Palvimo J. J. (2009) SUMOylation attenuates the function of PGC-1α. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 26184–26193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Picard N., Caron V., Bilodeau S., Sanchez M., Mascle X., Aubry M., Tremblay A. (2012) Identification of estrogen receptor beta as a SUMO-1 target reveals a novel phosphorylated sumoylation motif and regulation by glycogen synthase kinase 3β. Mol. Cell. Biol. 32, 2709–2721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ananthanarayanan M., Balasubramanian N., Makishima M., Mangelsdorf D. J., Suchy F. J. (2001) Human bile salt export pump promoter is transactivated by the farnesoid X receptor/bile acid receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 28857–28865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ananthanarayanan M., Li S., Balasubramaniyan N., Suchy F. J., Walsh M. J. (2004) Ligand-dependent activation of the farnesoid X-receptor directs arginine methylation of histone H3 by CARM1. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 54348–54357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Balasubramaniyan N., Ananthanarayanan M., Suchy F. J. (2012) Direct methylation of FXR by Set7/9, a lysine methyltransferase, regulates the expression of FXR target genes. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 302, G937–947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ananthanarayanan M., Li Y., Surapureddi S., Balasubramaniyan N., Ahn J., Goldstein J. A., Suchy F. J. (2011) Histone H3K4 trimethylation by MLL3 as part of ASCOM complex is critical for NR activation of bile acid transporter genes and is down-regulated in cholestasis. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 300, G771–781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Das P. M., Ramachandran K., vanWert J., Singal R. (2004) Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay. BioTechniques 37, 961–969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chaya D., Zaret K. S. (2004) Sequential chromatin immunoprecipitation from animal tissues. Methods Enzymol. 376, 361–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tatham M. H., Rodriguez M. S., Xirodimas D. P., Hay R. T. (2009) Detection of protein SUMOylation in vivo. Nat. Protoc. 4, 1363–1371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pichler A. (2008) Analysis of sumoylation. Methods Mol. Biol. 446, 131–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sun A. Q., Balasubramaniyan N., Liu C. J., Shahid M., Suchy F. J. (2004) Association of the 16-kDa subunit c of vacuolar proton pump with the ileal Na+-dependent bile acid transporter. Protein-protein interaction and intracellular trafficking. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 16295–16300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Teng S., Luo H., Wang L. (2012) Predicting protein sumoylation sites from sequence features. Amino Acids 43, 447–455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schwartz D. (2012) Prediction of lysine post-translational modifications using bioinformatic tools. Essays Biochem. 52, 165–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zhou W., Hannoun Z., Jaffray E., Medine C. N., Black J. R., Greenhough S., Zhu L., Ross J. A., Forbes S., Wilmut I., Iredale J. P., Hay R. T., Hay D. C. (2012) SUMOylation of HNF4α regulates protein stability and hepatocyte function. J. Cell Sci. 125, 3630–3635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lin D. Y., Huang Y. S., Jeng J. C., Kuo H. Y., Chang C. C., Chao T. T., Ho C. C., Chen Y. C., Lin T. P., Fang H. I., Hung C. C., Suen C. S., Hwang M. J., Chang K. S., Maul G. G., Shih H. M. (2006) Role of SUMO-interacting motif in Daxx SUMO modification, subnuclear localization, and repression of sumoylated transcription factors. Mol. Cell 24, 341–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kolesar P., Sarangi P., Altmannova V., Zhao X., Krejci L. (2012) Dual roles of the SUMO-interacting motif in the regulation of Srs2 sumoylation. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, 7831–7843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Geier A., Fickert P., Trauner M. (2006) Mechanisms of disease. Mechanisms and clinical implications of cholestasis in sepsis. Nat. Clin. Pract. Gastroenterol. Hepatology 3, 574–585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zollner G., Trauner M. (2008) Mechanisms of cholestasis. Clin. Liver Dis. 1, 1–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kerscher O. (2007) SUMO junction-what's your function? New insights through SUMO-interacting motifs. EMBO Rep. 8, 550–555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Vavassori P., Mencarelli A., Renga B., Distrutti E., Fiorucci S. (2009) The bile acid receptor FXR is a modulator of intestinal innate immunity. J. Immunol. 183, 6251–6261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rosonina E., Duncan S. M., Manley J. L. (2010) SUMO functions in constitutive transcription and during activation of inducible genes in yeast. Genes Dev. 24, 1242–1252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Winter S., Fischle W. (2010) Epigenetic markers and their cross-talk. Essays Biochem. 48, 45–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Xu J., Wu R. C., O'Malley B. W. (2009) Normal and cancer-related functions of the p160 steroid receptor co-activator (SRC) family. Nat. Rev. Cancer 9, 615–630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kotaja N., Karvonen U., Jänne O. A., Palvimo J. J. (2002) The nuclear receptor interaction domain of GRIP1 is modulated by covalent attachment of SUMO-1. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 30283–30288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zollner G., Marschall H. U., Wagner M., Trauner M. (2006) Role of nuclear receptors in the adaptive response to bile acids and cholestasis. Pathogenetic and therapeutic considerations. Mol. Pharm. 3, 231–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lee J. H., Park S. M., Kim O. S., Lee C. S., Woo J. H., Park S. J., Joe E. H., Jou I. (2009) Differential SUMOylation of LXRα and LXRβ mediates transrepression of STAT1 inflammatory signaling in IFN-γ-stimulated brain astrocytes. Mol. Cell 35, 806–817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Paddibhatla I., Lee M. J., Kalamarz M. E., Ferrarese R., Govind S. (2010) Role for sumoylation in systemic inflammation and immune homeostasis in Drosophila larvae. PLoS Pathog. 6, e1001234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Soroka C. J., Ballatori N., Boyer J. L. (2010) Organic solute transporter, OSTα-OSTβ. Its role in bile acid transport and cholestasis. Semin. Liver Dis. 30, 178–185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]