Abstract

Mitogen- and stress-activated kinase 2 (MSK2) is an inhibitor of the transcription factor p53; here, we investigate the mechanisms underlying this inhibition. In the absence of stress stimuli, MSK2 selectively suppressed the expression of a subset of p53 target genes. This basal inhibition of p53 by MSK2 occurred independently of its catalytic kinase activity and of upstream mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling to MSK2. Furthermore, MSK2 interacted with and inhibited the p53 coactivator p300, and associated with the Noxa promoter. Apoptotic stimuli promoted the degradation of MSK2, thus relieving its inhibitory activity towards p53 and allowing efficient p53-dependent transactivation of Noxa, which contributed to apoptosis. Together, these findings constitute a new mechanism of p53 activation in response to stress.

INTRODUCTION

The p53 transcription factor is a key tumor suppressor that mediates the cellular response to genotoxic stresses and oncogene activation. The activation of p53 by cellular stress has two major outcomes: cell cycle arrest or apoptosis, both of which prevent the proliferation of damaged cells (1, 2). The final biological response to p53 activation depends not only on the cell type but also on the nature of the stimulus, ultimately reflecting the complexity of p53-triggered transcriptional programs. The mechanisms proposed to explain the selective activation of p53 target genes in response to different stresses include the regulation of p53 affinity for its target promoters and its association with different transcriptional coregulators (3, 4). Both mechanisms may be affected by p53 posttranslational modifications, such as phosphorylation, acetylation, methylation, and ubiquitination, that may alter sequence-specific DNA binding and may additionally affect the interaction of p53 with transcriptional cofactors (3-5).

MSK2 and its homolog MSK1, are nuclear serine-threonine kinases that belong to the 90 kD ribosomal protein S6 kinase family formed by six kinases, namely, RSK1-4 and MSK1-2 (6, 7). These protein kinases contain two different protein kinase (PK) domains: PK1, which is similar to those found in AGC family kinases, and PK2, which is similar to those found in CaMK (calmodulin kinase) family kinases. Activation of the kinase function of MSKs occurs in two steps: first, activation of PK2 by phosphorylation mediated by the upstream MAPKs extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) or p38; and second, activation of PK1 by intramolecular phosphorylation mediated by PK2. In turn, PK1 is responsible for the phosphorylation of downstream substrates (8, 9). A distinguishing feature of MSKs is their activation by ERK in response to mitogenic signals and by p38 in response to stress, whereas other RSKs are activated only by mitogenic signals (10). A key role of MSKs appears to be the regulation of so-called immediate early (IE) genes, such as c-Fos and JunB, in response to mitogenic or stress stimuli (6, 7). Hence, cells from knockout mice lacking Msk1 and Msk2 show reduced transcription of specific IE genes (11-13). The transcriptional effects of MSK2 are mediated by its phosphorylation of transcription factors, such as CREB (cAMP response element binding), ATF1 (activating transcription factor 1), and NF-κB (nuclear factor κB) (11, 12, 14). In addition, through their association with transcription factors, MSKs can be recruited to specific promoters, where they contribute to chromatin remodeling by phosphorylation of histone H3 and HMG-14 (high mobility group chromosomal protein 14) (12, 15, 16). Transgenic mice lacking both Msk1 and Msk2 are viable and show specific phenotypes in neural function and immune response. In particular, mice lacking Msk1 and Msk2 have defective responses to dopamine and glutamate, as well as impaired memory (17)(18), and are hypersensitive to inflammatory stimuli (19).

We have previously identified MSK2 in an unbiased large-scale screen as a negative regulator of p53 (20). Here, we investigate the molecular mechanisms underlying the inhibition of p53 by MSK2.

RESULTS

MSK2 inhibits p53 in a kinase-independent manner

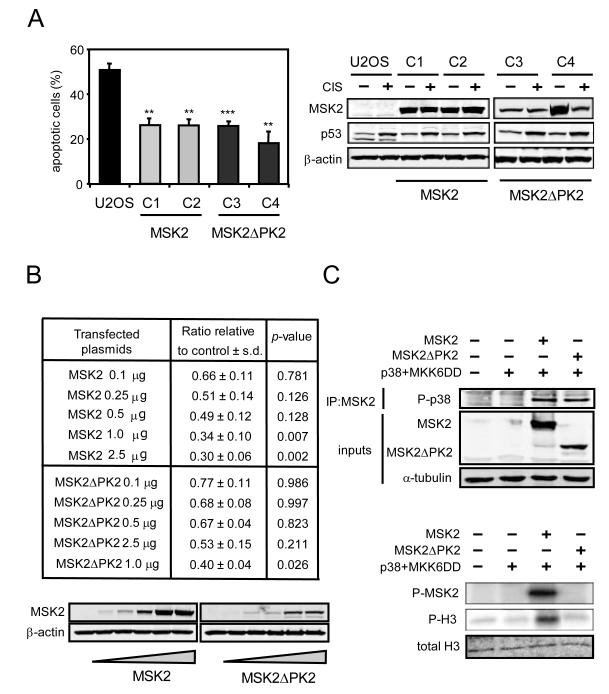

Transcription of the Msk2 gene generates two splicing variants encoding different protein isoforms: the full-length MSK2 protein containing kinase domains PK1 and PK2, and a smaller protein lacking PK2 referred to here as MSK2ΔPK2 (fig. S1, A and B). To understand the mechanism of inhibition of p53 by MSK2, we began by comparing the effect of MSK2 and MSK2ΔPK2 on p53 activity. Cisplatin-induced apoptosis in U2OS cells is dependent on p53 activity (21) (fig. S3A) and stable overexpression of either MSK2 or MSK2ΔPK2 protected against apoptosis (Fig. 1A). To further substantiate this finding, we performed p53 transactivation assays using a reporter based on the promoter of the p53-responsive gene Pig3, which is sensitive to p53 activity (22). Both MSK2 and MSK2ΔPK2 showed a similar inhibitory effect on the transcriptional activity of the Pig3 promoter (Fig. 1B). Moreover, suppression of p53 transcriptional activity by MSK2 was insensitive to the status of upstream MSK2-activating pathways. In particular, the inhibitory action of MSK2 on p53 was not affected by activation of the ERK pathway by transfection of constitutively active Ras (RasV12) or activation of the p38 pathway by transfection of constitutively active MKK6 (MKK6DD) (fig. S1C). In contrast to this, but in agreement with the canonical function of MSK2, activation of the MSK2 downstream phosphorylation target CREB was induced by MKK6DD and it was strictly dependent on the presence of the PK2 domain of MSK2 (fig. S1D). Similar results were observed using a reporter for the transcriptional activity of activator protein 1 (AP1), which is activated by phosphorylated CREB (7, 23) (fig. S1D). We confirmed that MSK2ΔPK2 cannot be phosphorylated by p38 and that it lacks kinase activity in an in vitro kinase assay using histone H3 as substrate (Fig. 1C). Additionally, a full-length MSK2 variant containing a kinase-dead PK1 domain (MSK2K65R), which was generated by mutating the conserved critical lysine residue at the ATP-binding site of the PK1 domain, did not activate an AP1-dependent promoter in response to MKK6 activation (fig. S1E) but decreased the transcriptional activity of p53 as efficiently as wild-type MSK2 (fig. S1F). To rule out the presence of residual kinase activity in MSK2ΔPK2 and MSK2K65R, we generated a double mutant carrying the K65R mutation at PK1 and deleted for PK2. The resulting MSK2 variant (MSK2ΔPK2K65R), which lacks functional PK domains, inhibited p53 transcriptional function to the same extent as the other MSK2 forms (fig. S1G). Finally, the C-terminal domain (CT) (fig. S1A), which binds the upstream kinases p38 and ERK (24), was deleted from MSK2 and MSK2ΔPK2 (MSK2ΔCT and MSK2ΔPK2ΔCT, respectively) (fig. S1H). These mutants did not affect MKK6- and p38-mediated activation of an AP1-responsive promoter, but retained their full inhibitory effect towards p53 (fig. S1H). Taken together, these observations indicate that MSK2 inhibits p53 through a kinase-independent mechanism.

Fig. 1.

MSK2 kinase activity is not required for p53 inhibition. (A) U2OS cell clones stably expressing transfected MSK2-V5 (C1 and C2) or MSK2ΔPK2-V5 (C3 and C4) were treated with cisplatin (CIS) for 48 hours, and apoptosis was quantified by flow cytometry. Error bars represent standard deviation of the mean (SDM) from three samples (left). Protein abundance of MSK2-V5, MSK2ΔPK2-V5, p53, and β-actin was determined by Western blotting (right). (B) A Pig3 luciferase reporter plasmid (Pig3-luc) was cotransfected in U2OS cells with increasing amounts of MSK2-V5 or MSK2ΔPK2-V5 expression plasmids. Error bars represent SDM from three samples (top). A representative immunoblot is shown (bottom). (C) U2OS cells were cotransfected with MKK6DD and p38α together with empty plasmid, MSK2-V5, or MSK2ΔPK2-V5 plasmids. The exogenously expressed proteins were immunoprecipitated with V5 antibody and subjected to in vitro kinase assay using histone H3 (H3) as substrate (right). Phosphorylated MSK2 (P-MSK2) and H3 (P-H3) were detected by autoradiography, and total H3 was detected by Western blotting. Immunoprecipitated p38αand total MSK2, MSK2ΔPK2, and α-tubulin in the inputs were detected by Western blotting (left). Statistical significance was determined by ANOVA. * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001.

MSK2 selectively inhibits the transcription of a subset of p53 targets

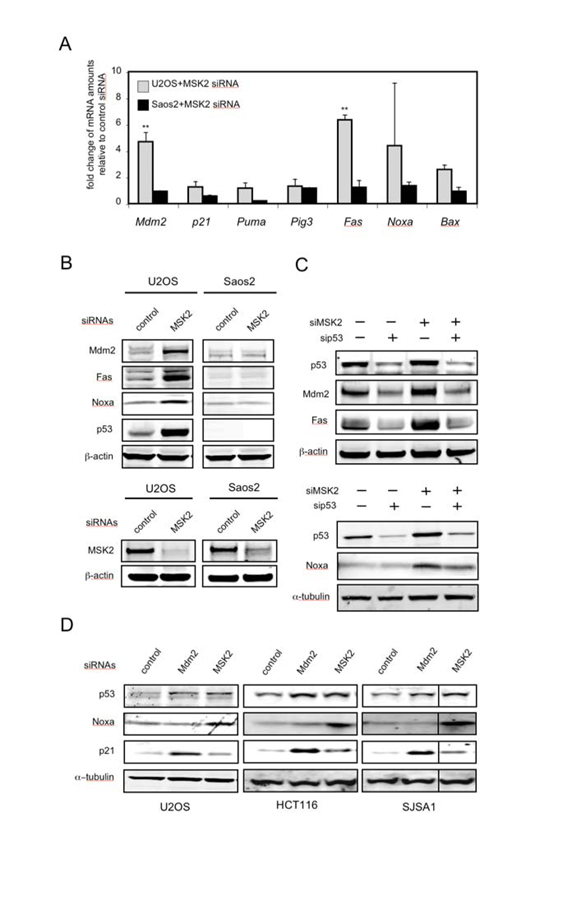

To gain further insight and to avoid the use of ectopic reporter plasmids or overexpressed proteins, we knocked down endogenous MSK2 with a small interfering RNA (siRNA) that targeted both MSK2- and MSK2ΔPK2-encoding mRNAs (fig. S2A). Knock-down of endogenous MSK2 in U2OS cells resulted in increased mRNA abundance of the p53 target genes Mdm2, Fas and Noxa, but did not affect the transcript levels of other p53 target genes, such as p21, Puma, Pig3, or Bax (Fig. 2A). In contrast, knock-down of MSK2 in p53-deficient Saos2 cells did not alter the mRNA abundance of p53 target genes (Fig. 2A). The analysis of protein abundance confirmed that, following MSK2 silencing, Mdm2, Fas and Noxa were induced in U2OS cells, but not in Saos2 cells (Fig. 2B). To confirm that MSK2 regulation of Mdm2, Fas and Noxa is mediated by p53, endogenous p53 was knocked down in U2OS cells prior to transfection of MSK2 siRNA. As anticipated, p53 knock-down reduced the induction of these genes by MSK2 siRNA (Fig. 2C). Knock-down of MSK2 resulted in increased p53 protein abundance (Fig. 2, B to D), which could be due to stabilization of the protein, as inferred by the kinetics of p53 degradation when protein synthesis was inhibited by cycloheximide (fig. S2B). Because this is reminiscent of the effect of Mdm2 inhibition on p53 abundance (25), we compared the consequences of suppressing MSK2 or Mdm2 on p53 transcriptional targets (fig.S2A). We observed that in various p53-positive cell lines, MSK2 knock-down increased Noxa, but not p21; while, in contrast, Mdm2 knock-down induced p21, but not Noxa (Fig. 2D). Thus, in the absence of p53-activating stimuli, endogenous MSK2 inhibits basal transcription of a subset of p53 targets, such as Noxa, through a mechanism fundamentally different from that of Mdm2.

Fig. 2.

Knock-down of MSK2 results in selective activation of p53 target genes. (A) Induction of endogenous p53 targets by transfection of the indicated cells with MSK2 siRNA. The mRNA abundance of the indicated genes was analyzed 72 hours after transfection by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR). Error bars represent SDM from at least three samples assayed in duplicate. The Ct values were corrected by β-actin and fold expression values are relative to control siRNA. Statistical significance was determined by ANOVA and calculating the p values for the comparisons between cell lines. * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01. (B) p53-containing U2OS cells and p53-deficient Saos2 cells were transfected with the indicated siRNAs. Protein abundance was determined 72 hours later by Western blotting (top). Detection of endogenous MSK2 was possible only after immunoprecipitation. Identical amounts of total protein were immunoprecipitated with an MSK2 antibody and then analyzed by Western blot using a different MSK2 antibody. β-actin amounts in the inputs are shown (bottom). (C) U2OS cells were transfected first with control or p53 siRNAs and were transfected 24 hours later with control, Mdm2, or MSK2 siRNAs. Protein abundance was analyzed 48 hours after the second transfection. (D) p53-positive U2OS, HCT116, and SJSA1 cells were transfected with the indicated siRNAs. Protein abundance was analyzed 72 hours later by Western blotting.

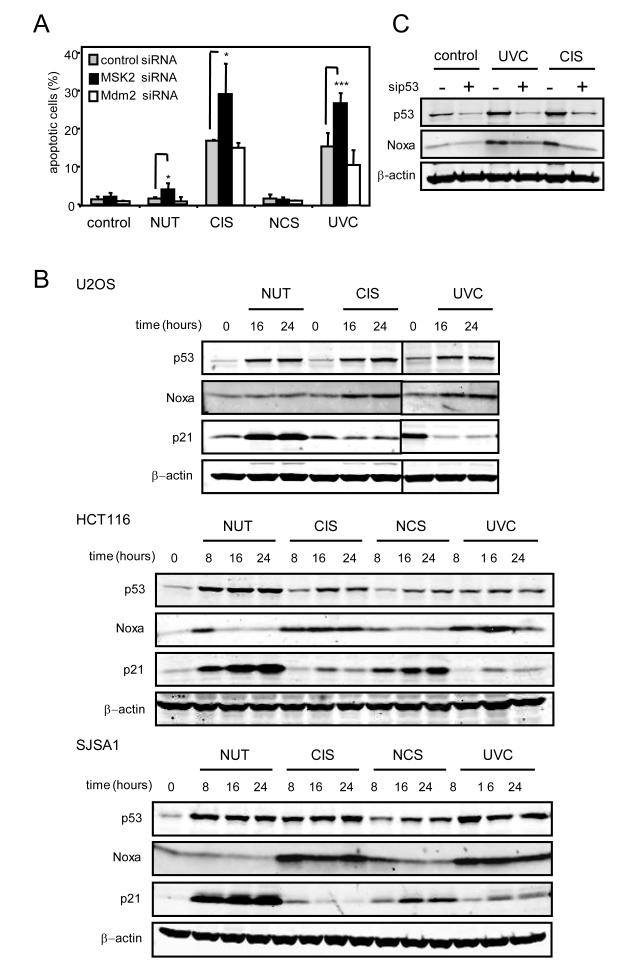

MSK2 inhibits apoptotic responses

Next, we analyzed the effect of MSK2 silencing on p53-dependent cellular responses to stress. U2OS cells were transfected with MSK2 and Mdm2 siRNAs prior to treatment with the DNA-damaging agents cisplatin (CIS), neocarzinostatin (NCS), and ultraviolet radiation (UVC), or with the Mdm2-specific inhibitor nutlin (NUT) (26). CIS and UVC induced p53-dependent apoptosis in U2OS and HCT116 cells (Fig. 3A and fig. S3A), whereas NCS and NUT elicited cell cycle arrest (Fig. 3A and fig. S3B). MSK2 knock-down enhanced the apoptotic response, whereas Mdm2 knock-down had little effect (Fig. 3A). In several p53-containing cell lines, the apoptotic responses elicited by CIS and UVC were accompanied by induction of Noxa, but not of p21, whereas NUT and NCS induced p21, but not Noxa (Fig. 3B). The increase in Noxa protein in response to CIS and UVC was abrogated by the transfection of a siRNA directed against p53, thus confirming that Noxa induction is dependent on p53 (Fig. 3C). The lack of effect of NUT on Noxa, both at the protein and mRNA levels (Fig. 3B and fig. S3C), was consistent with the lack of effect of Mdm2 silencing on Noxa (Fig. 2D). Thus, p53-dependent Noxa induction and apoptosis are negatively modulated by MSK2, implying that efficient apoptotic stimuli must cancel or surpass the inhibitory effect of MSK2.

Fig. 3.

Knock-down of MSK2 results in increased apoptosis and Noxa induction. (A) U2OS cells were transfected with control, Mdm2, or MSK2 siRNAs for 48 hours and treated with the indicated p53-inducing agents for an additional period of 24 hours. Apoptosis was analyzed by flow cytometry. Error bars represent SDM from at least three samples. Statistical analysis was determined by t-test. * P < 0.05; *** P < 0.001. (B) U2OS, HCT116 and SJSA1 cells were either irradiated (UVC) or treated with cisplatin (CIS) or neocarzinostatin (NCS) for the indicated times. Protein abundance was analyzed by Western blotting. (C) U2OS cells were transfected with control or p53 siRNAs and 48 hours later, were treated with UVC or CIS for 24 additional hours. Protein abundance was analyzed by Western blotting.

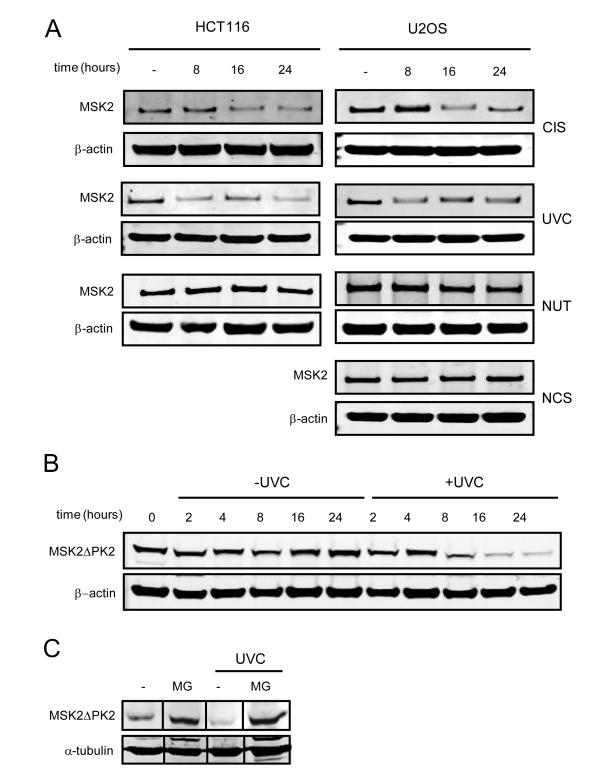

MSK2 is degraded in response to apoptotic stimuli

We investigated whether the apoptotic stimuli that induce Noxa affected MSK2 abundance. Noxa-inducing agents CIS and UVC triggered a decrease in endogenous MSK2, whereas stimuli unable to induce Noxa, such as NUT, NCS, or ionizing radiation (γIR), had no effect on MSK2 abundance (Fig. 4A and fig. S4A). This suggests an association between degradation of MSK2, increases in Noxa, and induction of apoptosis. The degradation of MSK2 is first detectable eight hours after treatment and therefore is unlikely to interfere with the canonical role of MSK2 in the immediate early response. Reduction of MSK2 abundance was not due to transcriptional regulation because its mRNA abundance remained unchanged upon apoptotic stimuli (fig. S4B). In contrast, analysis of protein degradation in the presence of cycloheximide revealed that the half-life of MSK2 is decreased following UVC (Fig. 4B). Moreover, the proteasome inhibitor MG132 increased the amount of ectopically expressed MSK2ΔPK2 and abolished MSK2ΔPK2 degradation by UVC treatment (Fig. 4C). Degradation of MSK2 after UVC treatment was observed in cell lines lacking p53, and MSK2 abundance was not altered in U2OS cells overexpressing Mdm2, suggesting that MSK2 stability was independent of p53 and Mdm2 (fig. S4, C and D). We also tested whether MKK6 and p38 were involved in MSK2 degradation, but MSK2 abundance was unaffected upon transient expression of MKK6 and p38 (fig. S4E). Moreover, the p38 inhibitor SB203580, which prevented phosphorylation of the p38 substrate HSP27 (heat shock protein 27), did not rescue UVC-induced MSK2 degradation (fig. S4E). These observations indicate that the MSK2 upstream activating kinases MKK6 and p38 do not participate in the degradation of MSK2 upon cellular stress. Collectively, our data suggests that apoptotic stimuli trigger MSK2 degradation, relieving basal inhibition of p53 by MSK2 and allowing efficient induction of Noxa and apoptosis.

Fig. 4.

Degradation of MSK2 by apoptotic stimuli. (A) U2OS and HCT116 were UVC irradiated (UVC) or treated with cisplatin (CIS), nutlin (NUT), or neocarzinostatin (NCS) for the indicated periods of time. Detection of endogenous MSK2 required immunoprecipitation: Identical amounts of total protein were immunoprecipitated with an MSK2 antibody and then analyzed by Western blot using a different MSK2 antibody. Protein abundance was analyzed by Western blotting. β-actin amounts in the inputs are shown. (B) U2OS cells were transfected with empty vector or MSK2ΔPK2-V5 plasmid. Twenty-four hours later the cells were irradiated and simultaneously treated with cycloheximide for the indicated times. (C) U2OS cells stably expressing MSK2ΔPK2-V5 were UVC irradiated and treated with the proteosome inhibitor MG132 (MG) for 24 hours.

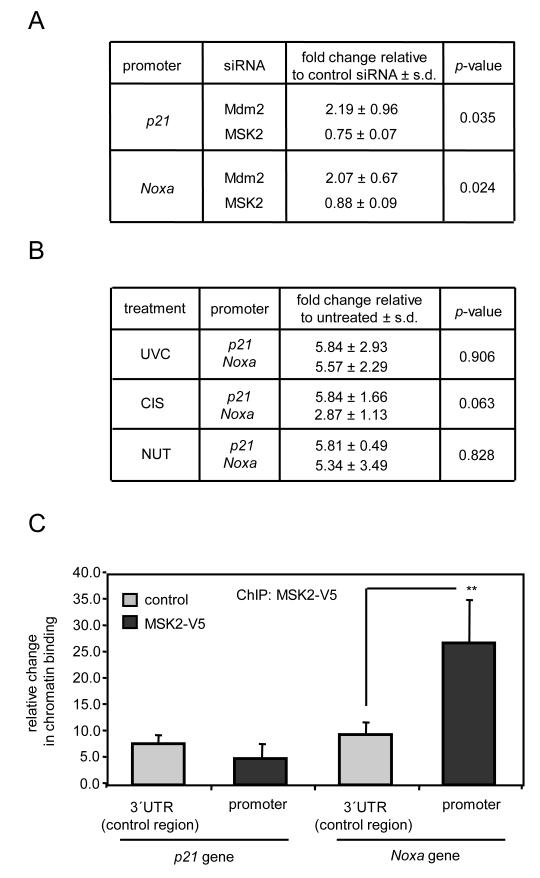

MSK2 associates with the Noxa promoter

To further investigate the mechanisms involved in Noxa suppression by MSK2, we tested whether MSK2 knock-down impacted p53 occupancy of the Noxa promoter. For this, p53-associated chromatin was immunoprecipitated from U2OS cells in which Mdm2 or MSK2 had been knocked-down by siRNA transfection. Knock-down of Mdm2 increased p53 recruitment to the p21 and Noxa promoters; however, MSK2 silencing did not affect p53 binding to the these promoters (Fig. 5A). This implies that the derepression of Noxa seen after MSK2 silencing does not involve increased association of p53 with the Noxa promoter. On the other hand, NUT increased p53 recruitment to Noxa promoter (Fig. 5B), but did not activate transcripton of Noxa (fig. S3D). Together, these data indicate that transcriptional activation of Noxa by p53 requires post-binding regulatory mechanisms at the promoter.

Fig. 5.

MSK2 binds to the Noxa promoter. (A) U2OS cells were transfected with control, Mdm2, or MSK2 siRNAs; 72 hours later, crosslinked DNA-protein complexes were subjected to chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) with p53 antibodies. Statistical analysis and SDM correspond to three samples assayed in duplicate. (B) U2OS cells were UVC irradiated or treated with cisplatin (CIS) or nutlin (NUT) for 8 hours and subjected to ChIP analysis for p53. Statistical analysis and SDM correspond to three independent experiments. (C) U2OS cells were transfected with empty vector or MSK2-V5, and 48 hours later, cell lysates were subjected to ChIP analysis with V5 antibody. Non-specific binding was assessed by amplifying a 3′ UTR region several Kb downstream of the indicated promoter region containing known p53-binding sites. Data corresponds to three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined by ANOVA. ** P < 0.01.

The MSK2 homolog MSK1 is recruited to specific promoters in association with certain transcription factors, such as the progesterone receptor or NF-κB (15, 27), leading us to investigate whether MSK2 could associate with the Noxa promoter. MSK2-associated chromatin was immunoprecipitated from U2OS cells transiently expressing this protein. Remarkably, specific binding of MSK2 to the Noxa promoter, but not to the p21 promoter (Fig. 5C) or the Fas promoter (fig. S5A), was detected. Similar analyses amplifying a DNA region 7 to 8 kb downstream of the p53 binding sites of p21 and Noxa promoters did not reveal enrichment of p53 upon MSK2 over-expression (Fig. 5C and fig. S5A). We have been unable to detect an association between MSK2 and p53 by coimmunoprecipitation under conditions in which endogenous p53-Mdm2 complexes were readily detected (fig. S5B), suggesting that MSK2 is recruited to the DNA through binding partners other than p53.

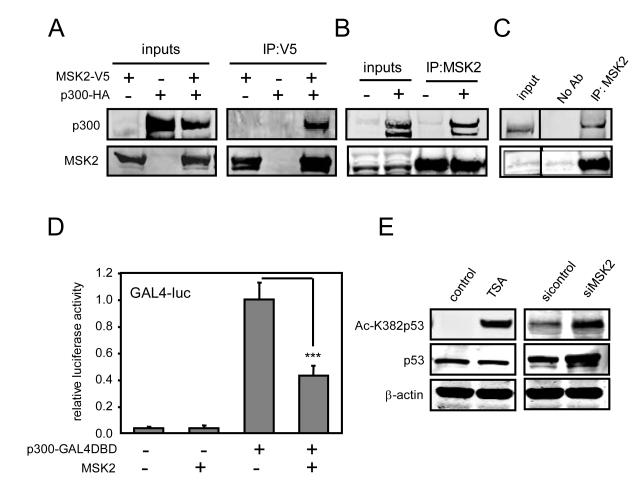

MSK2 binds and inhibits the p53 coactivator p300

To gain further insight into MSK2-mediated p53 repression, we performed a yeast two-hybrid screen using MSK2 as bait. Among the putative MSK2-interacting proteins, the histone acetyltransferase (HAT) p300, a p53 coactivator (28) which interacts with MSK1 in transfected cells (29), was identified. The p300 fragments that interacted with MSK2 overlap with its HAT domain (fig. S6A). Incidentally, despite the large number of proteins interacting with p300, few are known to interact with the HAT domain (fig. S6A). Transfected and endogenous MSK2 coimmunoprecipitated with transfected p300 (Fig. 6, A and B) and, moreover, the endogenous proteins also associate since they can be coimmunoprecipitated (Fig. 6C). To analyze whether MSK2 could modulate p300 transcriptional activity, p300-GAL4DBD was cotransfected with a GAL4-luciferase reporter in the presence or absence of MSK2. MSK2 significantly reduced p300 transcriptional activity (Fig. 6D). Because p300 coactivates a number of transcription factors in addition to p53, such as NF-κB and nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT), we tested whether MSK2 overexpression had an effect on their activity. MSK2 had a weaker inhibitory effect on NF-κB and NFAT (fig. S6B), than on p53 (Fig. 1B and fig. S1, C, F and G). p300 acetylates various proteins, including p53 (28, 30). Thus, we tested whether MSK2 inhibits p300-mediated acetylation of p53. Knock-down of MSK2 increased p53 acetylation at Lys382, a residue acetylated by p300 (Fig. 6E and fig. S6C). Together, these results suggest that MSK2 inhibits p53 transactivation by inhibiting p300 coactivating function.

Fig. 6.

MSK2 binds to p300 and antagonizes its activity. (A) Human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293T cells were cotransfected with p300-HA and MSK2-V5 expression plasmids. After 48 hours, equal amounts of total protein were immunoprecipitated with V5 antibody. (B) Cells as in panel (A) were transfected with control or p300-HA plasmids. Endogenous MSK2 was immunoprecipitated with MSK2 antibody, and precipitates were immunoblotted with p300 antibody. (C) Endogenous MSK2-p300 complexes were detected in HEK 293T cells by immunoprecipitation with MSK2 antibody and Western blot analysis. (D) U2OS cells were cotransfected with GAL4-luc and p300-GAL4DBD plasmids in the presence of empty vector or MSK2, and luciferase activity was analyzed 48 hours later. Error bars represent SDM of four samples. The luciferase values are relative to the activity of GAL4-luc promoter in the presence of p300-GAL4DBD. Statistical analysis was performed by ANOVA and p value was calculated for the indicated comparison: *** P < 0.001. (E) U2OS cells were transfected with control or MSK2 siRNAs for 72 hours. Control cells were treated with the histone deacetylase inhibitor trichostatin A (TSA) for 16 hours. Amounts of p53 acetylated at Lys382 (Ac-K382p53) and total p53 were analyzed by Western blot.

DISCUSSION

MSK2 was identified as a p53-inhibitor in a loss-of-function large-scale screen for transcriptional regulators of p53 (20). Here, we have characterized the molecular mechanisms involved in the inhibition of p53 by MSK2.

MSK2 belongs to the 90 Kd ribosomal protein S6 kinase family. Other members of this family have been previously implicated in the regulation of p53, both as positive (RSK2) (31) and negative (RSK4) (32) modulators, although the underlying mechanisms remain uncharacterized. More generally, MSK1 and MSK2 impact transcription through direct phosphorylation of transcription factors, as well as through chromatin modifications associated with phosphorylation of histone H3 at Ser10 (6). A common theme in the previously known transcriptional effects of MSK2 is their reliance on the kinase activity of MSK2 (6, 7, 13). In contrast, we found that the regulation of p53 transcriptional activity by MSK2 did not depend on its kinase activity. Various MSK2 mutants lacking kinase activity retained their full capacity to inhibit p53 transactivation, whereas they were deficient in the activation of MSK2 direct or indirect downstream targets, such as CREB1 or AP1, respectively. Moreover, MSK2 inhibitory activity towards p53 was independent of the canonical MAPK upstream kinases, which are normally necessary to activate MSKs through phosphorylation and ensuing conformational changes (7, 33). For example, elimination of the docking site for p38 and ERK (CT) in MSK2 abrogated its activation by p38, but did not affect its inhibitory activity towards p53. Therefore, the inhibition of p53 by MSK2 is independent of its kinase activity and of upstream MAPK kinases.

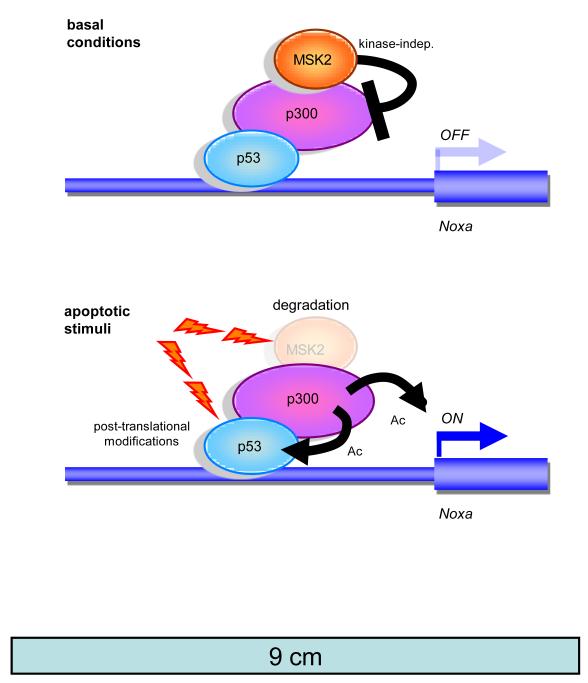

We observed that MSK2 inhibition impacted basal transcription of the apoptotic p53 targets Fas and Noxa, which occurred in a p53-dependent manner and in the absence of p53-activating stimuli. These observations imply that p53 is constitutively bound to the Noxa promoter, but kept inactive through MSK2, which is also bound to the Noxa promoter (Fig. 7). This model is not unprecedented and, in fact, it is well established that, in the absence of activating stimuli, p53 is bound to the promoters of several targets in a silent state, poised to activate transcription upon stress (34). Various apoptotic stimuli, in particular cisplatin and UVC radiation, triggered MSK2 degradation, thus relieving p53 inhibition and allowing efficient activation of Noxa and apoptosis. In contrast, other p53 activating stimuli that did not induce apoptosis, but induce p53-dependent cell cycle arrest, did not promote MSK2 degradation or increase Noxa protein.

Fig. 7.

Model for MSK2 regulation of p53 activity at the Noxa promoter. In the absence of stimuli, MSK2 suppresses Noxa transcription by interfering with p300 cotranscriptional activity and p300-mediated p53 acetylation. Apoptotic stimuli, such as UVC and cisplatin, trigger MSK2 degradation alleviating the repression of p300 and allowing p53-mediated transcriptional activation of the Noxa promoter.

The above data prompted us to investigate whether MSK2 could associate with the Noxa promoter. Indeed, MSK2 was selectively recruited to the Noxa promoter, but not to the p21 promoter, the latter of which was not affected by MSK2 inhibition. This suggests that MSK2 may act as a modulator of p53 in the context of specific promoters. Previously identified p53 regulators that operate in the context of a subset of p53 target genes include apoptosis stimulating protein of p53 (ASPP) and chromosome segregation 1-like (CSE1L), which favor the transcription of pro-apoptotic genes (35, 36); hematopoietic zinc finger (Hzf), which activates p53 target genes involved in cell cycle arrest (37); and Slug, which represses p53 pro-apoptotic genes (38). We identified p300 as an MSK2-binding protein in a yeast two-hybrid assay, thus providing a putative intermediate for the effects of MSK2 on p53. Strikingly, the results of the two-hybrid assay indicated that MSK2 binds to the acetyltransferase domain of p300. The MSK2 homolog MSK1 has been previously shown to interact with p300 in the context of transcriptional activation by the transcription factor ER81 (29). p300 coactivates p53 through multiple mechanisms, including chromatin remodeling by histone deacetylation, as well as by direct p53 acetylation (30). We found that MSK2 diminished p300 transactivating activity and reduced with p300-mediated acetylation of p53. Similar to our findings, it has been reported that the ubiquitin ligase component Skp2 also inhibits p53 apoptotic targets by interacting with p300 (39).

Taken together, our results strongly suggest a model according to which MSK2 binds and represses the Noxa promoter under basal conditions. This could be in part through inhibition of p300 activity (Fig. 7, top). After specific cellular insults, MSK2 is degraded, allowing p53-mediated transcriptional activation of Noxa (Fig. 7, bottom). In a broader context, our data help to unravel the complexity of p53 transcriptional activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids

MSK2 isoforms and mutants were cloned by PCR into pcDNA3.1/V5-His plasmid (Invitrogen). The reporter −73Col-luc and the expression plasmids MKK6DD-myc and p38-myc have been previously described (40, 41). The Gal4-luc reporter plasmid, p300-HA, p53-GAL4DBD, p300-GAL4DBD, and control GAL4DBD plasmids were provided by Dr. Revilla. Mdm2-luc and Pig3-luc plasmids have been previously described (20). The AP1-luc and CRE-luc Pathdetect Cis-reporter plasmids were purchased from Stratagene.

Reporter assays

Cells were seeded in 12-well plates (85,000 cells per well) and 24 hours later, were transfected with Lipofectamine LTX (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The transfection mixtures contained 100 ng of the reporter plasmid, 2.5 ng of the E1α-Renilla plasmid, and 2 μg of the corresponding cDNA plasmid. The preparation of the cellular extracts and the quantification of the luciferase and Renilla activities were carried out 48 hours post-transfection using the commercially available kit Dual-Luciferase Assay System (Promega). In all cases, transfections were performed in duplicate and the luciferase values were normalized by Renilla luciferase.

RNA interference

The siRNA duplexes were synthesized by Dharmacon and transfected with Dharmafect (Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO) following the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA or protein extraction was carried out 72 hours after siRNA transfections. For flow cytometry analysis, p53-activating drugs were added to the culture plates 48 hours after siRNA transfection and cell cycle profiles were analyzed 24 hours later. The following siRNA sequences were used to knock-down endogenous genes: MSK2, GAGCGGACCUUCUCCUUCUUU; p53, GACUCCAGUGGUAAUCUACUU; Mdm2, CCACCUCACAGAUUCCAGCUU. Cyclophilin and non-targeting siRNAs (both from Dharmacon) were use as negative controls.

Apoptosis and cell cycle analysis

Cells were seeded at subconfluency in 60 mm plates and 24 hours later, were UVC irradiated (10 J/m2) or treated with 40 μM cisplatin, 10 μM nutlin, or 200 ng/ml neocarzinostatin. After 24 or 48 hours treatment, floating and attached cells were collected and fixed in 70% ethanol. Fixed cells were treated with 100 μg/ml RNAse (Qiagen) and stained with propidium iodide (Sigma). Subsequently, the cell cycle distribution was analyzed by flow cytometry in FACSscalibur (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ) and quantified with the program MoFit.

Immunoblotting

72 hours after transfection with siRNAs for 72 hours, or treatment with p53-inducing agents (UVC 10 J/m2, 40 μM cisplatin, 10 μM nutlin, 200 μg/ml neocarzinostatin, 0.9 μM doxorubicin or 5 μM trichostatin A) for the indicated times, cells were harvested in lysis buffer containing 1% SDS and 1% Triton X-100. Identical amounts of protein were resolved by SDS/PAGE and electrotransferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Blots were incubated with the following antibodies: anti-p53 (DO-1, Santa Cruz), anti-acetyl-p53 Lys382, (2570, Cell Signaling), anti-phospho p53 Ser15 (16G8, Santa Cruz), anti-β-actin (AC-15, Sigma), α-tubulin (T9028, Sigma), anti-V5 (Invitrogen), anti-p21 (C-19, Santa Cruz), anti-Mdm2 (2A10, Abcam), anti Fas (C-20, Santa Cruz), anti-Noxa (114C307, Calbiochem), anti-MSK2 (clone 261034, R&D Systems), anti phospho-p38 (9211, Cell Signaling), or anti phospho-Hsp27 (523, Stressgen SPA), and subsequently incubated with the corresponding Alexa Fluor 680 secondary antibody (Invitrogen). Proteins were detected with a Li-Cor Odyssey Infrared imager.

Immunoprecipitation

Cells were lysed in NET buffer: 50 mM Tris pH 8, 120 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 1% NP40. To immunoprecipitate endogenous MSK2, 2 mg of total protein extracts were incubated with 6 μg of anti-MSK2 (Zymed laboratories) and protein A agarose beads (sc-2001, Santa Cruz), and the immunoprecipitated protein was detected with anti-MSK2 (clone 261034, R&D systems). For p300-MSK2 coimmunoprecipitations, endogenous or transfected proteins were immunoprecipitated with 2 μg of anti-p300 (N-15, Santa Cruz) or 6 μg of anti-MSK2 (Zymed Laboratories) and protein A agarose beads (sc-2001, Santa Cruz). The immunoprecipitated proteins were detected with anti-p300 (N-15, Santa Cruz), anti-HA (Y-11, Santa Cruz), or anti-MSK2 (clone 261034, R&D systems).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

Cells were fixed for 15 min in medium containing 1% formaldehyde, and the cross-linking reaction was stopped by addition of glycine to a final concentration of 125 mM. Cell dishes were washed twice with ice-cold PBS containing protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche), scraped on ice, and harvested by centrifugation at 2,000 rpm at 4°C. The resulting pellet was then lysed in an appropriate volume (106 cells per 100 ml) of lysis buffer (1% SDS, 10 mM EDTA, 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.1 plus protease inhibitor cocktail) and chromatin was sheared in a bath sonicator (Diagenode Bioruptor), to an average length of 0.2-0.8 kb. Samples were then centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 10 min at 13°C, and supernatants containing the fragmented chromatin were collected. 200 μg of fragmented DNA per antibody and condition (including a no antibody control sample) were diluted in 10X Dilution Buffer (1% Triton X-100, 2 mM EDTA pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.1), pre-cleared for 1 hour at 4°C with 60 μl 50% slurry salmon sperm DNA with protein A or protein G agarose (Upstate), and incubated overnight at 4°C with 2-5 μg of anti-p53 (DO1, Santa Cruz) or anti-V5 (Invitrogen). 30 μg of each sample (INPUT) were frozen and kept at −80°C until the reverse-crosslink step. After 14 hours at 4°C in a rotating platform, samples were incubated for one additional hour in presence of 60 μl of salmon sperm DNA/50% slurry protein A/G Agarose. Immune complexes were then washed once in each the following buffers: low salt wash buffer (0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM EDTA pH 8.0, 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.1, 150 mM NaCl), high salt wash buffer (0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM EDTA pH 8.0, 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.1, 500 mM NaCl), LiCl wash buffer (0.25 M LiCl, 1% NP-40, 1% deoxycholate, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.1), and twice in TE. Immune complexes were eluted after two rounds of incubation with 250 μl of freshly prepared elution buffer (1% SDS, 0.1 M NaHCO3), and cross-linking was reverted by addition of 20 μl of 5 M NaCl and incubation at 65°C for 4 hours. After 1 hour of proteinase K digestion, the DNA was recovered by phenol/chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. The primers used are provided in the Supplementary Materials.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was isolated with Trizol reagent (Invitrogen). cDNA synthesis was performed using 5 μg total RNA, Superscript II Reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen), and random primers (Invitrogen). For mRNA and ChIP experiments, qRT-PCR was performed using SybrGreenER Master Mix in a 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). Reactions were performed in triplicate and normalized by β-actin expression in the case of mRNA detection, or by the inputs in the case of the ChIPs. Primer sequences are provided in the Supplementary Materials.

Yeast two-hybrid screen

The yeast two-hybrid screen using MSK2ΔPK2 ORF (BC047896) as bait was performed by Hybrigenics Y2H Screen Service (http://www.hybrigenics.com).

In vitro kinase assay

U2OS cells were transfected with p38α and MKK6DD (1 μg each) expression plasmids with control, MSK2, or MSK2ΔPK2 expression plasmids (6 μg). Forty-eight hours after transfection, the cells were lysed in IP buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% (v/v) NP-40, 5 mM EDTA pH 8.0, 5 mM EGTA pH 8.0, 20 mM NaF, 0.1 μM PMSF, 0.5 μM benzamidine, 1 μg/μl leupeptin, 1 μg/μl aprotinin, 2 μM microcystin, 0.1 μM NaVO3) and MSK2 proteins were immunoprecipitated with anti-V5 antibody (Invitrogen). For the in vitro kinase assay, the immunoprecipitated proteins were incubated with 2 μCi of [γ-32P] ATP (3000 Ci/mmol, Amersham) and 1 μg of recombinant purified histone H3 (New England Biolabs) for 60 min at 37°C in kinase assay buffer (50 mM Tris HCl pH 7.4, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 5 mM NaF, 1 mM DTT, 5 mM β-glycerophosphate, 0.05 mM NaVO3). The reactions were stopped by addition of 10 ml of 4× sample buffer and boiling for 5 min at 95°C. The samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE electrophoresis, and the gels were stained with Coomassie Blue and subjected to autoradiography for 4 to 24 hours at room temperature.

Statistical analysis

When multiple variables were tested, the statistical analysis was performed by two-way ANOVA to test for the existence of significant variations followed by the Dunn-Sidak post-test for the indicated comparisons. Otherwise, as indicated, Student’s t-test was used.

Supplementary Material

Editor’s Summary.

Kinase Activity Not Required The tumor suppressor p53, which mediates transcriptional responses to DNA damage, is encoded by one of the most frequently mutated genes in cancer cells. Its activity can be increased or decreased by various binding partners, such as the mitogen- and stress-activated kinase 2 (MSK2). Although MSK2 regulates other transcription factors by phosphorylating them, Llanos et al. show that inhibition of p53 by MSK2 does not require its kinase function. p53 transcriptional activity was inhibited by an MSK2 mutant lacking both kinase domains, (the sentence could end there or continue as here ->) and, conversely, induction of MSK2 kinase activity by its upstream regulators left unaltered p53 transcriptional activity. MSK2 basally inhibited p53 activity at a subset of promoters by reducing the activity of the histone deacetylase p300, which coactivates p53. In response to specific apoptotic stimuli, such as cisplatin and ultraviolet C radiation, MSK2 was degraded, lifting its inhibitory effect on p53 and allowing p53-mediated induction of the pro-apoptotic protein Noxa. Thus, these results delineate a kinase-independent function for MSK2 and a new pathway by which p53 activity can be regulated.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ramon Diaz-Uriarte for his help on statistical analysis. We are indebted to Simon Arthur, Angel Nebreda, Ana Rojas, Yolanda Revilla, and Pan Yao for help and for generously providing us with critical reagents. S.L. is a “Ramon y Cajal” scientist from the Spanish Ministry of Science (MICINN) and is recipient of a grant from the MICINN (SAF2006-07785). Work at the laboratory of M.S. is funded by the CNIO and by grants from the MICINN (SAF2005-03018 and OncoBIO-CONSOLIDER), the Regional Government of Madrid (GsSTEM), the European Union (PROTEOMAGE), the European Research Council (ERC) and the “Marcelino Botin” Foundation.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Vogelstein B, Lane D, Levine AJ. Surfing the p53 network. Nature. 2000;408:307–310. doi: 10.1038/35042675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vousden KH, Lu X. Live or let die: the cell’s response to p53. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:594–604. doi: 10.1038/nrc864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Toledo F, Wahl GM. Regulating the p53 pathway: in vitro hypotheses, in vivo veritas. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:909–923. doi: 10.1038/nrc2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Espinosa JM. Mechanisms of regulatory diversity within the p53 transcriptional network. Oncogene. 2008;27:4013–4023. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Riley T, Sontag E, Chen P, Levine A. Transcriptional control of human p53-regulated genes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:402–412. doi: 10.1038/nrm2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dunn KL, Espino PS, Drobic B, He S, Davie JR. The Ras-MAPK signal transduction pathway, cancer and chromatin remodeling. Biochem Cell Biol. 2005;83:1–14. doi: 10.1139/o04-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arthur JS. MSK activation and physiological roles. Front Biosci. 2008;13:5866–5879. doi: 10.2741/3122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCoy CE, Campbell DG, Deak M, Bloomberg GB, Arthur JS. MSK1 activity is controlled by multiple phosphorylation sites. Biochem J. 2005;387:507–517. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCoy CE, et al. Identification of novel phosphorylation sites in MSK1 by precursor ion scanning MS. Biochem J. 2007;402:491–501. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deak M, Clifton AD, Lucocq LM, Alessi DR. Mitogen- and stress-activated protein kinase-1 (MSK1) is directly activated by MAPK and SAPK2/p38, and may mediate activation of CREB. Embo J. 1998;17:4426–4441. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.15.4426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wiggin GR, et al. MSK1 and MSK2 are required for the mitogen- and stress-induced phosphorylation of CREB and ATF1 in fibroblasts. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:2871–2881. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.8.2871-2881.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Soloaga A, et al. MSK2 and MSK1 mediate the mitogen- and stress-induced phosphorylation of histone H3 and HMG-14. Embo J. 2003;22:2788–2797. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arthur JS, et al. Mitogen- and stress-activated protein kinase 1 mediates cAMP response element-binding protein phosphorylation and activation by neurotrophins. J Neurosci. 2004;24:4324–4332. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5227-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vermeulen L, De Wilde G, Van Damme P, Vanden Berghe W, Haegeman G. Transcriptional activation of the NF-kappaB p65 subunit by mitogen- and stress-activated protein kinase-1 (MSK1) Embo J. 2003;22:1313–1324. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vicent GP, et al. Induction of progesterone target genes requires activation of Erk and Msk kinases and phosphorylation of histone H3. Mol Cell. 2006;24:367–381. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang HM, et al. Mitogen-induced recruitment of ERK and MSK to SRE promoter complexes by ternary complex factor Elk-1. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:2594–2607. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brami-Cherrier K, et al. Parsing molecular and behavioral effects of cocaine in mitogen- and stress-activated protein kinase-1-deficient mice. J Neurosci. 2005;25:11444–11454. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1711-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chwang WB, Arthur JS, Schumacher A, Sweatt JD. The nuclear kinase mitogen- and stress-activated protein kinase 1 regulates hippocampal chromatin remodeling in memory formation. J Neurosci. 2007;27:12732–12742. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2522-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ananieva O, et al. The kinases MSK1 and MSK2 act as negative regulators of Toll-like receptor signaling. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:1028–1036. doi: 10.1038/ni.1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Llanos S, Efeyan A, Monsech J, Dominguez O, Serrano M. A high-throughput loss-of-function screening identifies novel p53 regulators. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:1880–1885. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.16.3140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Siddik ZH. Cisplatin: mode of cytotoxic action and molecular basis of resistance. Oncogene. 2003;22:7265–7279. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Contente A, Zischler H, Einspanier A, Dobbelstein M. A promoter that acquired p53 responsiveness during primate evolution. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1756–1758. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pierrat B, Correia JS, Mary JL, Tomas-Zuber M, Lesslauer W. RSK-B, a novel ribosomal S6 kinase family member, is a CREB kinase under dominant control of p38alpha mitogen-activated protein kinase (p38alphaMAPK) J Biol Chem. 1998;273:29661–29671. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.45.29661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tomas-Zuber M, Mary JL, Lamour F, Bur D, Lesslauer W. C-terminal elements control location, activation threshold, and p38 docking of ribosomal S6 kinase B (RSKB) J Biol Chem. 2001;276:5892–5899. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005822200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brooks CL, Gu W. p53 ubiquitination: Mdm2 and beyond. Mol Cell. 2006;21:307–315. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vassilev LT. MDM2 inhibitors for cancer therapy. Trends Mol Med. 2007;13:23–31. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beck IM, et al. Altered subcellular distribution of MSK1 induced by glucocorticoids contributes to NF-kappaB inhibition. Embo J. 2008;27:1682–1693. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coutts AS, La Thangue NB. The p53 response: emerging levels of co-factor complexity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;331:778–785. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.03.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Janknecht R. Regulation of the ER81 transcription factor and its coactivators by mitogen- and stress-activated protein kinase 1 (MSK1) Oncogene. 2003;22:746–755. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kalkhoven E. CBP and p300: HATs for different occasions. Biochem Pharmacol. 2004;68:1145–1155. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berns K, et al. A large-scale RNAi screen in human cells identifies new components of the p53 pathway. Nature. 2004;428:431–437. doi: 10.1038/nature02371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cho YY, et al. The p53 protein is a novel substrate of ribosomal S6 kinase 2 and a critical intermediary for ribosomal S6 kinase 2 and histone H3 interaction. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3596–3603. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith KJ, et al. The structure of MSK1 reveals a novel autoinhibitory conformation for a dual kinase protein. Structure. 2004;12:1067–1077. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shaked H, et al. Chromatin Immunoprecipitation-on-Chip Reveals Stress-Dependent p53 Occupancy in Primary Normal Cells but Not in Established Cell Lines. Cancer Res. 2008;68:9671–9677. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu ZJ, Lu X, Zhong S. ASPP--Apoptotic specific regulator of p53. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1756:77–80. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tanaka T, Ohkubo S, Tatsuno I, Prives C. hCAS/CSE1L associates with chromatin and regulates expression of select p53 target genes. Cell. 2007;130:638–650. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Das S, et al. Hzf Determines cell survival upon genotoxic stress by modulating p53 transactivation. Cell. 2007;130:624–637. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu WS, et al. Slug antagonizes p53-mediated apoptosis of hematopoietic progenitors by repressing puma. Cell. 2005;123:641–653. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kitagawa M, Lee SH, McCormick F. Skp2 suppresses p53-dependent apoptosis by inhibiting p300. Mol Cell. 2008;29:217–231. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Angel P, Hattori K, Smeal T, Karin M. The jun proto-oncogene is positively autoregulated by its product, Jun/AP-1. Cell. 1988;55:875–885. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90143-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ambrosino C, et al. Negative feedback regulation of MKK6 mRNA stability by p38alpha mitogen-activated protein kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:370–381. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.1.370-381.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.