Abstract

The importance of ubiquitination in MHC class I-restricted Ag processing remains unclear. To address this issue, we overexpressed wild-type and dominant-negative lysineless forms of ubiquitin (Ub) in mammalian cells using an inducible vaccinia virus system. Overexpression of the lysineless Ub nearly abrogated polyubiquitination and potently inhibited epitope presentation from a cytosolic N-end rule substrate as well as endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-targeted model Ags. In contrast, there was little impact on Ag presentation from cytosolic proteins. These trends were location dependent; redirecting cytosolic Ag to the ER rendered presentation lysineless Ub-sensitive, whereas retargeting exocytic Ag to the cytosol had the inverse effect. This dichotomy was further underscored by small interfering RNA knockdown of the ER-associated Ub ligase Hrd1. Thus, Ub-dependent degradation appears to play a major role in the MHC class I-restricted processing of ER-targeted proteins and a more restricted role in the processing of cytosolic proteins.

The multicatalytic proteasome is involved in most cytosolic proteolysis, and increasing evidence indicates its indispensable role in production of most MHC class I-restricted antigenic peptides (1). The 26S proteasome is comprised of the 20S catalytic core capped at both ends with 19S regulator complexes that bind and unfold polyubiquitinated substrates (2). Although ubiquitin (Ub)-mediated degradation is critical for cellular viability and was originally considered to be the only means of proteasomal destruction, it is now generally accepted that a substantial portion of intracellular proteolysis is Ub independent (3). Other modifications have been shown to target substrates to the 26S proteasome (4, 5), and self-directed delivery to the 20S core has been described (6). In our own system, we observed that a large fragment of influenza nucleoprotein (NP) is efficiently presented even after every lysine, the target of conventional ubiquitnation, had been substituted (7).

Most insights into the ubiquitination pathway have been gained with yeast- and cell-free systems. It remains challenging to study protein ubiquitination in higher eukaryotes in part because selective inhibitors of the pathway are unavailable. Use of a temperature-sensitive ubiquitination mutant in class I-processing studies has led to conflicting results (8, 9), possibly because a fraction of the temperature-sensitive protein (the E1 activating enzyme) is functional at the restrictive temperature (10). This approach is further complicated by the existence of a second E1 enzyme that may have redundant activity (11).

Based upon the rapid kinetics with which MHC class I-restricted peptides can be generated (12) and the increasingly apparent diversity of proteasome-based degradation, we have proposed a model in which nascent cytosolic polypeptides that fail to be engaged by the intracellular folding machinery are delivered to the 20S proteasome for immediate destruction (13). We also speculated that this might not apply to endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-targeted Ags because they are subjected to ER-associated degradation (ERAD), which generally entails a quality control decision followed by retrotranslocation, polyubiquitination, and degradation by the 26S proteasome (14). To explore these issues, we generated a vaccinia virus (VV) recombinant that conditionally expresses high levels of a dominant-negative lysineless Ub (UbK0), thereby interfering with polyubiquitination.

Materials and Methods

VV recombinants

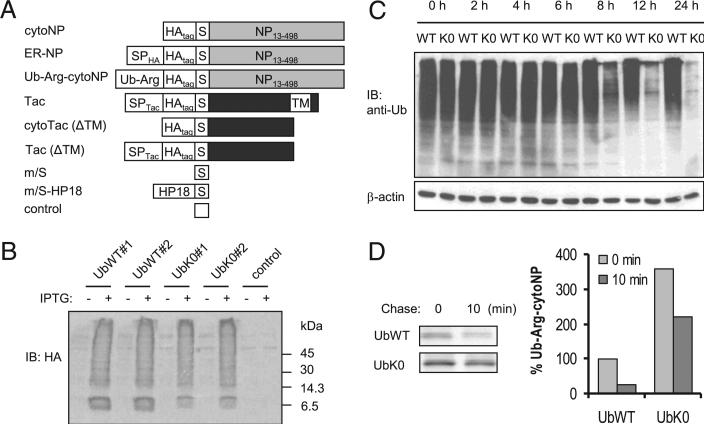

Wild-type Ub (UbWT) and UbK0 genes (a generous gift from Dr. Bruce E. Clurman, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center) with hemagglutinin (HA) epitope tags at the N terminus were constructed by standard PCR methods. Isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-inducible VV recombinants were generated as described (15). Other Ag-expressing VVs have been described (16–18) and are shown in Fig. 1A.

FIGURE 1.

UbK0 expression blocks protein polyubiquitination and degradation. A, SIINFEKL-expressing model Ags. Residues 1–12 of NP are essential for nuclear localization. This segment was removed from NP, creating cytoNP (17), to simplify interpretation of the results. B. L-Kb cells were infected with VV expressing UbWT, UbK0, or no insert (control) at 3 PFU/cell in the presence or absence of IPTG for 12 h. IB analyses with anti-HA Ab were performed to detect IPTG-induced expression of HA-tagged Ub. C, L-Kb cells were infected with UbWT or UbK0 virus at 3 PFU/cell in the presence of IPTG. At the indicated times postinfection, cell lysates were subjected to 8% SDS-PAGE and blotted with FK1 Ab to detect protein polyubiquitination. D, L-Kb cells were coinfected with UbWT or UbK0 virus and Ub-Arg-cytoNP virus, all at 3 PFU/cell for 7 h in the presence of IPTG. The infected cells were then metabolically labeled with [35S] Met/Cys. The degradation of Ub-Arg-cytoNP protein was determined by immunoprecipitation and autoradiography. S, OVA257–264, SP, signal peptide.

Viral infection

Cells were infected with inducible VV recombinants for 1 h and then incubated in complete medium throughout the remainder of the assay. IPTG (Calbiochem) was used at a final concentration of 2 mM during the entire period of virus infection. In coinfection assays, L-Kb (L929 transfected with H-2Kb) cells were infected with UbWT or UbK0 VV and a VV expressing one of the model Ags, each at 3 PFU/cell in the presence of IPTG. To assess impact on epitope generation, the infected cells were treated with citrate buffer (0.13 M citric acid, 0.061 M Na2HPO4, 0.15 M NaCl [pH 3]) at 5.5 h postinfection to remove surface MHC class I peptides and cultured for an additional 12 h before flow cytometry analysis.

Immunoblotting analysis

Laemmli SDS-PAGE and transfer to nitrocellulose membrane were performed as previously described (19). The protein bands were blotted with the primary Abs including anti-HA (Roche), anti-polyubiquitinated proteins (FK1; Biomol), anti–β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich), and anti-Hrd1 (Abgent). The secondary Abs were HRP-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (HA), anti-mouse IgM (FK1), and anti-rabbit IgG (β-actin, Hrd1), respectively.

Pulse-chase assay

Metabolic labeling and immunoprecipitation were performed as previously described (20). Gels were dried and exposed to a Storage Phosphor Screen (Molecular Dynamics). Signal intensities were visualized on the Storm 860 fluorescent scanner and quantified using ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics).

RNA interference

Knockdown of Hrd1 was carried out with a predesigned small interfering RNA (siRNA) targeting Hrd1 or a control siRNA (Ambion) using Lipofectamine RNAiMax (Invitrogen) at a final concentration of 10 nM.

Flow cytometry

OVA257–264 epitope presentation was assessed by surface staining with 25D1.16 Ab specific for the Kb/OVA257–264 complex as previously described (16). The mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) of OVA257–264 presentation was normalized by MFI from the control virus without Ag expression. The inhibitory effect of UbK0 on OVA257–264 presentation was determined by referencing to normalized MFI from UbWT infection. The inhibitory effect of Hrd1 siRNA on OVA257–264 presentation was determined by referencing to normalized MFI from control siRNA-treated samples.

Statistics

Statistical analysis and graphing was performed with GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad). Comparisons between groups were made using ANOVA with Tukey's posttest analysis.

Results

Generation of inducible VV recombinants expressing UbWT and mutant Ub

The design of the dominant interfering UbK0 construct is depicted in Supplemental Fig. 1A. The key feature is substitution of each Lys residue (seven in total) with Arg, thereby eliminating the possibility of Ub branching beyond the point of UbK0 addition. In addition, a triple HA-tag was added to the N terminus of both constructs for detection of free and conjugated forms. Given the naturally high levels of Ub, we anticipated the need for excessive UbK0 expression. Initially, we used the conventional (constitutive) VV expression system but repeatedly failed to recover virus. This was likely due to toxicity of constitutive UbK0 expression, leading to premature death of the cells used for propagation of the virus. We therefore shifted to a tightly controlled conditional lac operon-based VV system (15). Induction of UbWT and UbK0 with the anticipated expression kinetics was confirmed by immunoblotting (IB) using an anti-HA Ab (Fig. 1B, Supplemental Fig. 1B). Subsequently, L-Kb cells were infected with different doses of virus for 12 h, and general protein ubiquitination was examined by IB using the FK1 Ab specific to polyubiquitinated substrates. Lysates from uninfected cells exhibited high levels of polyubiquitinated conjugates. HA-tagged UbWT had limited impact even at a high dose, suggesting that endogenous Ub is at or near saturating levels. In contrast, polyubiquitination was potently abrogated by infection with UbK0 viruses ranging from 1–10 PFU/cell (Supplemental Fig. 1C). Reduction in polyubiquitination was easily detected at 8 h postinfection and appeared nearly complete by 12 h (Fig. 1C). Indeed, this approach may underestimate impact because the remaining bands could be residual species formed prior to the onset of effective UbK0 levels.

Proteins with large hydrophobic, basic, or acidic side chains at their N termini undergo rapid Ub-dependent degradation (the N-end rule) (21). We tested the impact of UbK0 expression on an N-end rule substrate, Ub-Arg-cytoNP (16), in which the Ub moiety is cotranslationally removed by Ub hydrolase and the resulting N-terminal Arg provides the degradation motif (22). Pulse-chase analyses demonstrated that Ub-Arg-cytoNP is very rapidly degraded in cells coex-pressing UbWT (Fig. 1D). In contrast, equivalent coinfection with UbK0 resulted in marked accumulation of Ub-ArgcytoNP at the zero time point due to turnover of substrate during the 10-min pulse (Supplemental Fig. 2) and a substantially slower degradation rate during the 10-min chase. Although we did not completely prevent degradation of this exceptionally unstable substrate, subsequent experiments demonstrated that this level of inhibition was more than sufficient for our purposes.

Impact of UbK0 expression on the presentation of the same epitope from two different protein contexts

Having validated the UbK0 system in biochemical assays, we assessed the impact of UbK0 expression on specific epitope presentation from defined Ags. All constructs tested were engineered to contain the H-2Kb–restricted OVA257–264 (SIINFEKL) epitope for which presentation can be quantified with the H2-Kb/OVA257–264-specific Ab 25.D1.16 (23). A cytosolically targeted version of influenza nucleoprotein, cytoNP, was used as a model cytosolic Ag, and human IL-2R α-chain (Tac) was used as a model exocytic Ag. The N-end rule substrate, Ub-Arg-cytoNP, served as a positive control, and a minigene construct, expressing the minimal SIINFEKL epitope (m/S), which does not require processing for presentation, was used as a negative control. Because cells cannot be sequentially infected with VV due to a potent interference effect (24), L-Kb cells were coinfected with Ag- and UbWT/UbK0-expressing viruses and then treated with citrate buffer 5.5 h postinfection to remove any peptides generated before effective concentrations of viral Ub had been reached. Following acid elution, the cells were incubated for an additional 12 h prior to assessment of surface Kb/OVA257–264 complexes. OVA257–264 presentation from Ub-Arg-cytoNP was markedly reduced by overexpression of UbK0 (Fig. 2A), indicating the ability of overexpressed UbK0 to block Ub-dependent Ag presentation. In contrast, UbK0 had limited impact on OVA257–264 presentation of the m/S construct. Interestingly, results with the two model Ags were similarly disparate. UbK0 had little impact on OVA257–264 presentation from the model cytosolic Ag cytoNP. This is consistent with a previous report that presentation of a stable cytosolic protein is not influenced by the temperature-sensitive E1 mutation (25). In contrast, UbK0 expression strongly inhibited presentation from the stable exocytic model Ag Tac.

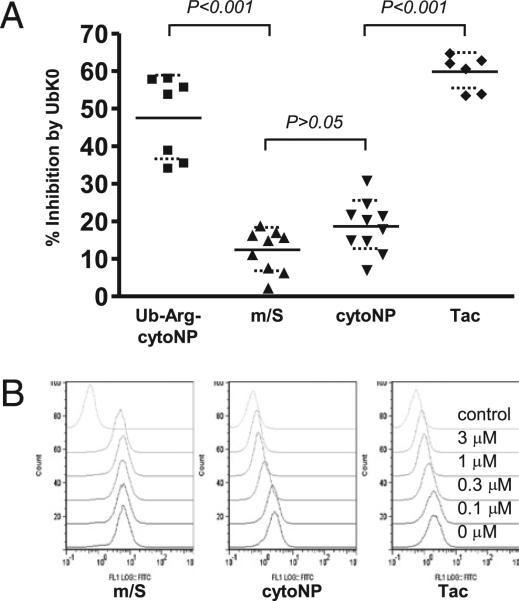

FIGURE 2.

UbK0 selectively inhibits presentation from the ER-targeted Tac Ag. A, Inhibitory effects of UbK0 on OVA257–264 presentation from different model Ags (see Supplemental Fig. 3 for representative primary data). Each symbol within a group represents an individual experiment, and the horizontal bars indicate the means and SD. Values of p were generated through the ANOVA test. B, L-Kb cells were treated with the indicated doses of epoxomicin for 15 min and then infected with virus expressing the model Ag at 3 PFU/cell for 5 h. OVA257–264 presentation was assessed by staining of surface OVA257–264/Kb complexes with 25.D1.16 Ab. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

A possible explanation for the results in Fig. 2A is that presentation of Tac is simply more proteasome-dependent than cytoNP. Tripeptidyl peptidase II, for example, has been reported to substitute for the proteasome in some cases, and its activity is not known to be regulated by Ub (26). To address this, aliquots of L-Kb cells were pretreated with various doses of the proteasome-specific inhibitor epoxomicin and then infected with the cytoNP-, Tac-, and m/S-expressing viruses. Whereas the minigene construct was only marginally inhibited, dose responses of cytoNP and Tac were very similar (Fig. 2B). This outcome was independent of UbK0 coexpression (Supplemental Fig. 4), indicating that loss of polyubiquitination does not retarget Ag to a proteasome-independent pathway. Thus, despite equal proteasome dependence, the ER-targeted and cytosolic Ags are highly disparate with respect to polyUb dependence.

Altered Ub-dependence following retargeting of the model Ags

To investigate whether subcellular location provides the basis for the disparity in dependence upon polyubiquitination, we used a construct (ER–NP) in which cytoNP was directed to the exocytic compartment by attachment of an influenza HA-derived signal peptide to its N terminus (17). Presentation of OVA257–264 from ER–NP was as sensitive to UbK0 as the Tac Ag (Fig. 3).

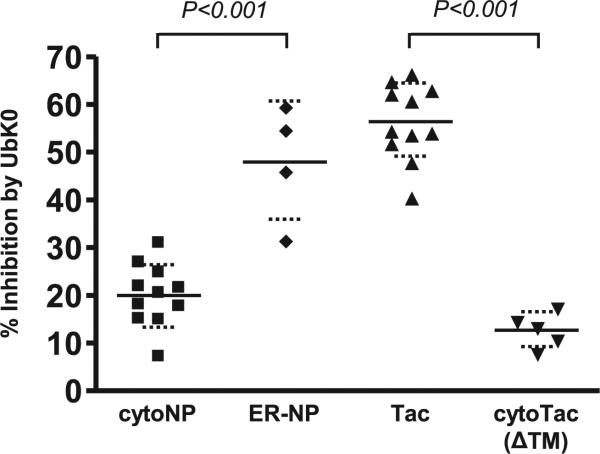

FIGURE 3.

The impact of UbK0 expression is determined by subcellular location, not identity of the Ag. Inhibitory effects of UbK0 on OVA257–264 presentation from NP retargeted to the ER and Tac retargeted to the cytosol. ER–NP was generated via addition of a signal peptide to the N terminus of cytoNP (17). cytoTac (ΔTM) was generated via deletion of the signal peptide and also deletion of the TM domain, which is a signal for rapid degradation (L. Huang, M.C. Kuhls, and L.C. Eisenlohr, submitted and revised for publication). Retargeting of cytoTac (ΔTM) was confirmed by imaging and biochemistry studies (Supplemental Fig. 5). Data were assessed as described for Fig. 2A.

Likewise, we removed the signal peptide from the Tac construct, which forced delivery to the cytosol, at the same time removing the transmembrane (TM) domain, which we have ascertained to constitute a degradation signal (Huang et al., submitted and revised for publication). In contrast to the parent protein, presentation of OVA257–264 from this cytosolic version, cytoTac (ΔTM), is essentially polyUb independent (Fig. 3). Thus, subcellular location appears to be a major determinant of polyUb-dependent Ag presentation.

Involvement of Ub ligase Hrd1 in presentation of ER-targeted proteins

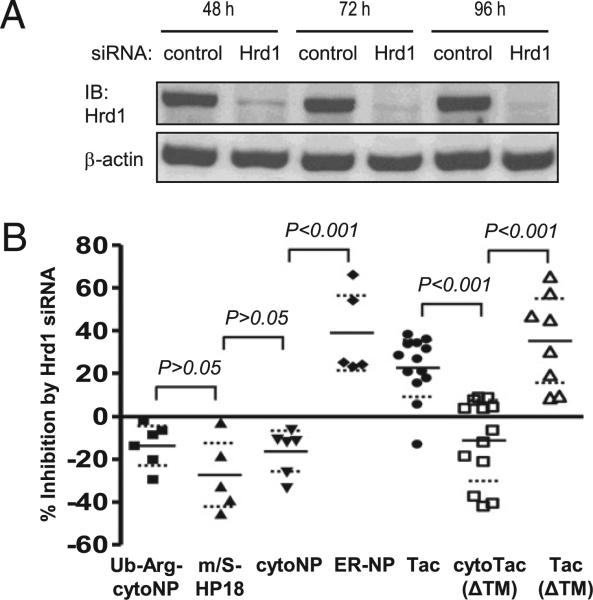

ER-targeted proteins that fail quality control are usually dislocated to the cytosol and degraded by the proteasome in a process known as ERAD (27). Covalent Ub conjugation via the ER-situated Hrd1 E3 Ub ligase appears to be required in many cases for the dislocation step (28). To explore further the distinction between cytosolic and ER-targeted Ags, we examined the role of Hrd1 in the processing of our model substrates. A Hrd1-specific siRNA knockdown strategy was validated by IB analysis (Fig. 4A). Consistent with the results shown in Figs. 2 and 3, suppression of Hrd1 by siRNA inhibited presentation of ER-targeted Ags, whereas presentation of cytosolic Ags was, if anything, slightly enhanced (Fig. 4B). Similar results were obtained with two additional Hrd1-specific siRNA sequences (Supplemental Fig. 7). This result provides further support for a selective role of polyubiquitination in the generation of MHC class I peptides.

FIGURE 4.

Selective involvement of Ub E3 ligase Hrd1 in MHC class I-restricted presentation of ER-targeted Ags. L-Kb cells were treated with Hrd1 siRNA. A, Total cell lysates were subjected to IB using anti-Hrd1 Ab. B, Inhibitory effects of 72 h Hrd1 siRNA treatment on OVA257–264 presentation from different model Ags (see Supplemental Fig. 6 for representative primary data). A proteasome-independent m/S under the control of an 18-bp hairpin structure to limit expression level (m/S-HP18) (18), was used as a negative control. Tac (ΔTM) is a secreted version of Tac generated by deletion of the TM domain. Data were assessed as described for Fig. 2A.

Discussion

The Ub-independent processing of the cytosolic proteins is consistent with the model we have proposed in which a fraction of the nascent cytosolic protein pool fails to be intercepted by the cellular folding machinery (the nonfolded cohort) and is immediately degraded by the 20S proteasome (13). This is distinct from misfolded and senescent cytosolic proteins that are subjected to more prolonged conventional quality control decisions and polyUb targeting to the 26S proteasome. In contrast, processing of ER-targeted substrates may generally involve polyubiquitination and delivery to the 26S protea-some, a consequence of the topology and the processes that are involved in ERAD (14). Further supporting this notion is our recent observation that processing of ER-targeted versus cytosolic substrates is markedly prolonged, resulting in much lower peak levels of epitope at the cell surface (Huang et al., submitted and revised for publication). The impact of Hrd1 knockdown argues that the effect of UbK0 on ER-targeted substrates is direct rather than through effects on other cellular components. It seems virtually certain that, as with cytosolic Ags, there will be exceptions to this generality because cases of Ub-independent ERAD have been described (29). Additionally, it is important to note that our experiments were performed in the context of VV infection, a potent inducer of the immunoproteasome (1), which degrades polyubiquitinated species more efficiently than the constitutive proteasome (30). Although such conditions are clearly relevant, it remains to be seen whether Ag processing in uninfected cells demonstrates a different dependence upon polyubiquitination.

Any cellular protein is heterogeneous in terms of folding state, location, and degree of modification. Thus, many proteins can be degraded via both Ub-dependent and -independent mechanisms (3). This will likely be the case for the processing of some Ags, but the decided partitioning of our model Ags with the positive and negative constructs suggests minimal heterogeneity in this respect.

The existence of such functionally distinct pathways may have important immunological consequences. In addition to the quantitative and temporal aspects in epitope production that have been eluded to, we have previously noted qualitative differences in processing when the same protein is targeted to the cytosol versus ER (17), perhaps a result of targeting to different proteasomal species. These differences could play a major role in determining those MHC class I-restricted epitopes within a complex Ag that are immunodominant and those that are most protective, both major considerations in rational vaccine design.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Tatiana N. Golovina for providing the model Ag constructs and Dr. Luis Sigal (Fox Chase Cancer Center) for critical reading of this manuscript.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant AI39501.

Abbreviations used in this article

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- ERAD

endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation

- HA

hemagglutinin

- IB

immunoblotting

- IPTG

isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside

- MFI

mean fluorescence intensity

- m/S

minigene construct, expressing the minimal SIINFEKL epitope

- NP

nucleoprotein

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- TM

transmembrane

- Ub

ubiquitin

- UbK0

lysineless ubiquitin

- UbWT

wild-type ubiquitin

- VV

vaccinia virus

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Kloetzel PM. The proteasome and MHC class I antigen processing. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2004;1695:225–233. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Orlowski M, Wilk S. Ubiquitin-independent proteolytic functions of the proteasome. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2003;415:1–5. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9861(03)00197-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jariel-Encontre I, Bossis G, Piechaczyk M. Ubiquitin-independent degradation of proteins by the proteasome. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2008;1786:153–177. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asher G, Bercovich Z, Tsvetkov P, Shaul Y, Kahana C. 20S proteasomal degradation of ornithine decarboxylase is regulated by NQO1. Mol. Cell. 2005;17:645–655. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Petropoulos L, Hiscott J. Association between HTLV-1 Tax and I kappa B alpha is dependent on the I kappa B alpha phosphorylation state. Virology. 1998;252:189–199. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Touitou R, Richardson J, Bose S, Nakanishi M, Rivett J, Allday MJ. A degradation signal located in the C-terminus of p21WAF1/CIP1 is a binding site for the C8 alpha-subunit of the 20S proteasome. EMBO J. 2001;20:2367–2375. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.10.2367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yellen-Shaw AJ, Eisenlohr LC. Regulation of class I-restricted epitope processing by local or distal flanking sequence. J. Immunol. 1997;158:1727–1733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Michalek MT, Grant EP, Gramm C, Goldberg AL, Rock KL. A role for the ubiquitin-dependent proteolytic pathway in MHC class I-restricted antigen presentation. Nature. 1993;363:552–554. doi: 10.1038/363552a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cox JH, Galardy P, Bennink JR, Yewdell JW. Presentation of endogenous and exogenous antigens is not affected by inactivation of E1 ubiquitin-activating enzyme in temperature-sensitive cell lines. J. Immunol. 1995;154:511–519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deveraux Q, Wells R, Rechsteiner M. Ubiquitin metabolism in ts85 cells, a mouse carcinoma line that contains a thermolabile ubiquitin activating enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:6323–6329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jin J, Li X, Gygi SP, Harper JW. Dual E1 activation systems for ubiquitin differentially regulate E2 enzyme charging. Nature. 2007;447:1135–1138. doi: 10.1038/nature05902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yewdell JW. Plumbing the sources of endogenous MHC class I peptide ligands. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2007;19:79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eisenlohr LC, Huang L, Golovina TN. Rethinking peptide supply to MHC class I molecules. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2007;7:403–410. doi: 10.1038/nri2077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vembar SS, Brodsky JL. One step at a time: endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;9:944–957. doi: 10.1038/nrm2546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ward GA, Stover CK, Moss B, Fuerst TR. Stringent chemical and thermal regulation of recombinant gene expression by vaccinia virus vectors in mammalian cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:6773–6777. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.15.6773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Golovina TN, Morrison SE, Eisenlohr LC. The impact of mis-folding versus targeted degradation on the efficiency of the MHC class I-restricted antigen processing. J. Immunol. 2005;174:2763–2769. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.5.2763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Golovina TN, Wherry EJ, Bullock TN, Eisenlohr LC. Efficient and qualitatively distinct MHC class I-restricted presentation of antigen targeted to the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Immunol. 2002;168:2667–2675. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.6.2667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wherry EJ, Puorro KA, Porgador A, Eisenlohr LC. The induction of virus-specific CTL as a function of increasing epitope expression: responses rise steadily until excessively high levels of epitope are attained. J. Immunol. 1999;163:3735–3745. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bullock TNJ, Eisenlohr LC. Ribosomal scanning past the primary initiation codon as a mechanism for expression of CTL epitopes encoded in alternative reading frames. J. Exp. Med. 1996;184:1319–1329. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.4.1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bachmair A, Varshavsky A. The degradation signal in a short-lived protein. Cell. 1989;56:1019–1032. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90635-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Turner GC, Varshavsky A. Detecting and measuring cotranslational protein degradation in vivo. Science. 2000;289:2117–2120. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5487.2117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Porgador A, Yewdell JW, Deng Y, Bennink JR, Germain RN. Localization, quantitation, and in situ detection of specific peptide-MHC class I complexes using a monoclonal antibody. Immunity. 1997;6:715–726. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80447-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Christen L, Seto J, Niles EG. Superinfection exclusion of vaccinia virus in virus-infected cell cultures. Virology. 1990;174:35–42. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90051-R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qian SB, Princiotta MF, Bennink JR, Yewdell JW. Characterization of rapidly degraded polypeptides in mammalian cells reveals a novel layer of nascent protein quality control. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:392–400. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509126200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kloetzel PM. Generation of major histocompatibility complex class I antigens: functional interplay between proteasomes and TPPII. Nat. Immunol. 2004;5:661–669. doi: 10.1038/ni1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carvalho P, Goder V, Rapoport TA. Distinct ubiquitin-ligase complexes define convergent pathways for the degradation of ER proteins. Cell. 2006;126:361–373. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jarosch E, Taxis C, Volkwein C, Bordallo J, Finley D, Wolf DH, Sommer T. Protein dislocation from the ER requires polyubiquitination and the AAA-ATPase Cdc48. Nat. Cell Biol. 2002;4:134–139. doi: 10.1038/ncb746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kothe M, Ye Y, Wagner JS, De Luca HE, Kern E, Rapoport TA, Lencer WI. Role of p97 AAA-ATPase in the retrotranslocation of the cholera toxin A1 chain, a non-ubiquitinated substrate. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:28127–28132. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503138200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seifert U, Bialy LP, Ebstein F, Bech-Otschir D, Voigt A, Schröter F, Prozorovski T, Lange N, Steffen J, Rieger M, et al. Immunoproteasomes preserve protein homeostasis upon interferon-induced oxidative stress. Cell. 2010;142:613–624. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.