Abstract

Measures of cognitive dysfunction in Bipolar Disorder (BD) have identified state and trait dependent metrics. An influence of substance abuse (SUD) on BD has been suggested. This study investigates potential differential, additive, or interactive cognitive dysfunction in bipolar patients with or without a history of SUD. Two hundred fifty-six individuals with BD, 98 without SUD and 158 with SUD, and 97 Healthy Controls (HC) completed diagnostic interviews, neuropsychological testing, and symptom severity scales. The BD groups exhibited poorer performance than the HC group on most cognitive factors. The BD with SUD exhibited significantly poorer performance than BD without SUD in visual memory and conceptual reasoning/set-shifting. In addition, a significant interaction effect between substance use and depressive symptoms was found for auditory memory and emotion processing. BD patients with a history of SUD demonstrated worse visual memory and conceptual reasoning skills above and beyond the dysfunction observed in these domains among individuals with BD without SUD, suggesting greater impact on integrative, gestalt-driven processing domains. Future research might address longitudinal outcome as a function of BD, SUD, and combined BD/SUD to evaluate neural systems involved in risk for, and effects of, these illnesses.

Keywords: Mood disorders, Alcohol, Dual diagnosis, Cognition, Neuropsychology

1. Introduction

Bipolar Disorder (BD) is a severe psychiatric disorder characterized by recurrent episodes of mania and/or hypomania, as well as depressive episodes. Lifetime prevalence estimates of BD range from 1% when including only BD I to approximately 3.9% of the population in the United States when BD II and BD NOS are included (Kessler et al., 2005; Merikangas et al., 2007). Bipolar disorders are chronic and associated with increased morbidity and mortality (Angst et al., 2002), including significant cognitive difficulties with associated impact upon everyday functioning. Specifically, difficulties in processing speed, attention, executive functioning, memory, and fine motor skills have been well-documented (van Gorp et al., 1998; Robinson et al., 2006), even among individuals in the euthymic state (Zubieta et al., 2001; Thompson et al., 2005). Our group’s previous work demonstrated that individuals in the euthymic state of BD had significantly poorer performance compared to healthy individuals in processing speed with interference resolution, visual memory, and fine motor dexterity (Langenecker et al., 2010); comorbidities with other diagnoses, such as history of SUD, were not considered in that investigation.

There is an increased prevalence of substance use disorders (SUD) among individuals with bipolar illness (Kessler et al., 1994; Regier et al., 1990), with a reported lifetime occurrence as high as 60% (Cassidy et al., 2001). Specifically, patients with BD and excessive substance use have poorer educational attainments, reduced occupational standing, lower Global Assessment of Functioning-scores and degraded medication compliance, in addition to more suicide attempts compared to those with BD without SUD (Lagerberg et al., 2010). Additionally, impulsivity has been shown to be a prominent feature of both BD and SUD and those with BD who are more impulsive may be more susceptible to SUD (Martin et al., 1994). Likewise, those with comorbid BD and SUD tend to show greater risk-taking behaviors compared to those with BD without SUD, a potential interpretation of which is that individuals with BD and SUD may have an inaccurate perception of risk (Holmes et al., 2009).

While cognitive functioning has been extensively studied in BD and SUD, most studies have been underpowered to detect differences and results have been inconsistent. Specifically, BD patients with and without alcohol dependence have been shown to demonstrate impairment in verbal memory compared to healthy controls, but only those with BD and alcohol dependence show significantly worse executive functioning compared to controls (van Gorp et al., 1998); however, the BD groups were too small (n=12 and 13) to detect significant differences between them. Another comparison of BD groups with and without co-occurring alcohol dependence has shown that individuals with alcohol dependence exhibit worse performance on tasks of executive functioning, verbal and visual memory, and fluid intelligence (Levy et al., 2008), suggesting that co-occurring alcohol dependence adds a degree of severity to a pattern of cognitive impairment already found in BD. In contrast, other studies found that BD patients have poorer performance in verbal memory and executive functioning regardless of being euthymic and independent of alcohol history (Sanchez-Moreno et al., 2009) and that lifetime alcohol use disorder added no further explanation to performance on tests of other cognitive domains (van der Werf Eldering et al., 2010). While these reported findings provide inconsistent results, interpretations are limited by small sample sizes, effects of residual mood symptoms, and medication effects, all of which are factors specifically addressed in the current study.

The present study aimed to investigate the cognitive performance of BD (i.e., Bipolar I, II, and NOS) patients with or without a lifetime history of SUD, in addition to a healthy control group for comparison, while addressing previous limitations such as small sample size, phase of illness, and medication effects. While cognitive impairment has been extensively documented in BD and SUD, few studies have examined potential differential, additive, or interactive cognitive dysfunction in these often comorbid conditions. We hypothesized that individuals with BD with a lifetime history of SUD would perform more poorly on cognitive tasks compared to those BD without a lifetime history of SUD and healthy controls.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

Study participants were recruited for the Prechter Bipolar Repository between October 2005 and December 2011 at the University of Michigan for a study of phenotypic and biological outcomes of bipolar disorder (for description, see Langenecker et al., 2010). Of the 586 participants recruited for the longitudinal cohort, 256 individuals with confirmed Bipolar Disorder (201 Bipolar I Disorder, 36 Bipolar II Disorder, 19 Bipolar Disorder NOS) and 97 healthy controls were included in the present study. We chose to group all three BD diagnoses together in order to increase sample size; the results remained unchanged after running the same analyses with only the BD I group. The BD and HC samples were matched on age and verbal intelligence using the Wechsler Vocabulary score (Wechsler, 1997). Of those with confirmed BD, 158 had a lifetime history of SUD, while 98 did not. Furthermore, of those individuals meeting DMS-IV diagnostic criteria for SUD, there were 130 with Alcohol, 84 with Cannabis, 32 with Cocaine, 20 with Stimulant, 16 with Sedative, and 21 with Opiate Abuse and/or Dependence. Overall, 52.5% (n=83) of those in the SUD group met diagnostic criteria for only one substance, while 47.5% (n=75) met for multiple substances.

Recruitment of psychiatric participants occurred through an outpatient specialty psychiatry clinic, an inpatient psychiatric unit, and advertisements on the web and in the newspaper. Individuals were initially screened via telephone and those who qualified were offered an in-person baseline evaluation. All participants gave informed consent prior to participation. Participants were evaluated with Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies (DIGS; Nurnberger et al., 1994), neuropsychological testing, life event and symptom questionnaires, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS), and Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS). Final diagnoses were determined through a best estimate process and confirmed by at least three of the authors. Participants with BD were excluded from the study if they had a history of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder depressive type, active or current substance dependence (within six months of baseline evaluation), or a medical illness specifically associated with depressive symptoms (including but not limited to: terminal cancers, Cushing’s disease, or stroke). Those with active manic symptoms were also excluded by using a YMRS cut-off of 7 or less for inclusion (n=8 (without SUD) and n=21 (with SUD)); there were too few of these individuals to do meaningful comparisons. HC participants were recruited from on-line and print advertisements. HC participants were not eligible to participate if they had a history of any DSM-IV axis I disorder, active and current substance use disorder diagnosis, any medical illness specifically associated with depressive symptoms, or any first-degree family member who had been diagnosed or hospitalized for mental illness. This study was approved by the University of Michigan Institution Review Board (IRBMED: HUM00000606).

Table 1 contains demographic characteristics of the HC and BD (with and without SUD) groups. There were no significant differences between BD and HC groups for age, F (2) = 0.76, p = 0.47. There was also no significant difference for Wechsler Vocabulary, F (2) = 1.7, p = 0.18, a traditionally defined “hold” test that would not be expected to change based upon scar or burden effects of illness (Torres et al., 2007). This task was conceptualized as an index of the examinee’s general mental ability as word knowledge is shown to be correlated with learning, stable over time, and relatively resistant to psychological disturbance and to neurological deficit (Sattler, 2001). Education attainment was likely to be adversely affected by illness course, as typical onset of BD and SUD occurs during completion of high school and college. As such, there was a significant effect for education, F (2) = 7.48, p = 0.001; individuals with BD with SUD had fewer years of education relative to BD without SUD and HC. There was also a significant effect for gender, χ2(2, N=353)=11.85, p = 0.003, with both BD groups having more females than males relative to the HC group. This was addressed specifically in each subsequent analysis in order to eliminate these potential confounds. Note that results are similar when groups are matched on these demographics, and results are therefore reported for the entire sample.

Table 1.

Clinical and demographic characteristics in bipolar patients with and without a history of substance use disorder and in healthy controls.

| Variable | BD With SUD (n=158) M(S.D.) | BD Without SUD (n=98) M(S.D.) | Controls (n=97) M(S.D.) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 38.47 (12.02) | 39.92 (11.92) | 37.74 (14.23) | 0.47 |

| Education | 14.97 (2.18) | 15.90 (1.97) | 15.79 (2.17) | 0.001 BD, HC>BD+ |

| WASI vocabulary | 12.29 (2.25) | 12.78 (1.98) | 12.30 (2.45) | 0.18 |

| Gendera | ||||

| % females | 60.1 | 73.5 | 49.5 | 0.003 |

| HDRS-17 | 9.04 (6.16) | 7.91 (5.86) | 1.52 (0.15) | <0.001 BD+ >BD |

| YMRS | 3.54 (4.35) | 2.50 (3.04) | 0.59 (0.06) | <0.001 BD+ >BD |

| Years ill | 20.98 (12.45) | 19.89 (12.45) | – | 0.50 |

| First age at onset | 17.37 (6.79) | 20.22 (8.69) | – | 0.004 |

| Depression age at onset | 16.97 (7.85) | 20.52 (10.21) | – | 0.002 |

| Depression episodes | 26.61 (52.38) | 17.91 (38.63) | – | 0.16 |

| Mania age at onset | 18.83 (11.57) | 20.89 (14.00) | – | 0.21 |

| Mania episodes | 9.40 (18.25) | 5.34 (11.87) | – | 0.05 |

| Number of hospitalizations | 3.25 (3.74) | 2.69 (4.38) | – | 0.39 |

| Medication load | 2.68 (2.02) | 3.15 (2.22) | – | 0.08 |

| Total episodes | 65.91 (111.85) | 50.56 (89.04) | – | 0.25 |

| SUD age at onset | 19.97 (5.16) | |||

| Length of SUD (years) | 9.58 (8.22) |

Chi-Square.

WASI=Weschler Adult Scale of Intelligence; HDRS-17=Hamilton Depression Rating Scale 17-item; YMRS=Young Mania Rating Scale; BD=Bipolar Disorder without Substance Use Disorder; BD+=Bipolar Disorder with Substance Use Disorder; HC=Healthy Control

2.2. Assessments and measures

Clinical variables were collected during the baseline DIGS interview. Clinical variables of interest include years of illness, medication loading (Hassel et al., 2008), cumulative number of total mood episodes (including hypomania), cumulative number of episodes of mania and depression, number of hospitalizations, age of illness onset, age of first manic episode, and age of first depressive episode. Of those with SUD, 71.3% (n=111) had SUD following their first mood episode, while 29.7% (n=47) had SUD prior to their first mood episode. As shown in Table 1, there was a significant difference between the groups on the HDRS and YMRS, ps <0.001, with both BD groups having higher scores than the HC group. There was a significant difference for age at onset of first mood episode, t (251)=2.90, p = 0.004, as those BD with SUD had a younger age at onset. A significant difference was also found for depression age of onset, t (253)=3.12, p = 0.002, as those with BD and SUD had an earlier age of onset. A trend towards significance was found for self-reported manic episodes, t (246)=1.93, p = 0.055, as those individuals with BD and SUD had more self-reported manic episodes compared to those without SUD. No other differences were found between the BD groups and clinical variables.

All participants received a research-defined neuropsychological evaluation that focused on areas known to be adversely impacted in BD, including memory, attention and executive functioning, psychomotor speed, and emotion processing (Langenecker et al., 2010). The neuropsychological battery consisted of Rey–Osterrieth Complex Figure Test (Meyers and Meyers, 1995), California Verbal Learning Test-II (Delis et al., 2000), Purdue Pegboard test (Lezak, 1995), Emotion Perception test (Green and Allen, 1997), Facial Emotion Perception test (Rapport et al., 2002), Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (Grant and Berg, 1948), Stroop Color and Word Test (Golden, 1978), FAS verbal fluency task of the Controlled Oral Word Association Test and Animal Fluency (Benton and Hamsher, 1976), Digit Symbol-Coding from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Third Edition (Wechsler, 1997), Trail Making Test-Parts A and B (Armitage, 1946), and Parametric Go/No-Go task (Langenecker et al., 2005). Given the large number of dependent variables, standard data reduction techniques were utilized using conceptually, statistically, and theoretically derived variables (see Langenecker et al., 2010 for a full description). All test scores with negative scale properties (lower numbers reflect better performance) were inverted. Eight factor scores are used, including auditory memory, visual memory, fine motor dexterity, verbal fluency and processing speed, conceptual reasoning and set-shifting, processing speed with interference resolution, inhibitory control, and emotion processing.

2.3. Statistical analyses

The alpha level was set at p<0.05 and all analyses were conducted using SPSS 18.0. Analysis of variance (ANOVAs) and/or independent samples t-tests were used to test between-group differences in demographic variables. Multivariate analyses of covariance (MANCOVAs) were used to compare the factor scores of the three groups (healthy control, bipolar disorder without substance use disorder, and bipolar disorder with substance use disorder), with subsequent planned pairwise comparisons. Given that the groups differed significantly on gender and education, these variables were included as covariates in each analysis. Cognitive factors were then subjected to a two-way analysis of variance with two levels of substance use (with, without) and two levels of depression (with, without). The HDRS score of 8 was utilized to categorize individuals with and without significant depressive symptoms.

Participants in the BD group were taking a number of medications that varied in class and dose, which could impact cognitive functioning. Therefore, we examined the influence of medications by using criteria based on prior literature in order to determine medication load (Sackheim, 2001; Hassel et al., 2008; Almeida et al., 2009). Medications (antidepressant, anxiolytic, mood stabilizer, and antipsychotic) were coded as absent=0, low=1, or high=2 in order to convert each medication to a standard dose (Sackheim, 2001; Hassel et al., 2008; Almeida et al., 2009). Antipsychotic medication was converted into chlorpromazine dose equivalents (Davis and Chen, 2004). A composite measure consisting of total medication load was then generated by summing all medication codes for each individual medication within categories for each BD participant based on Hassel’s et al. (2008) methodology.

3. Results

3.1. Relationship between groups and cognitive factor scores

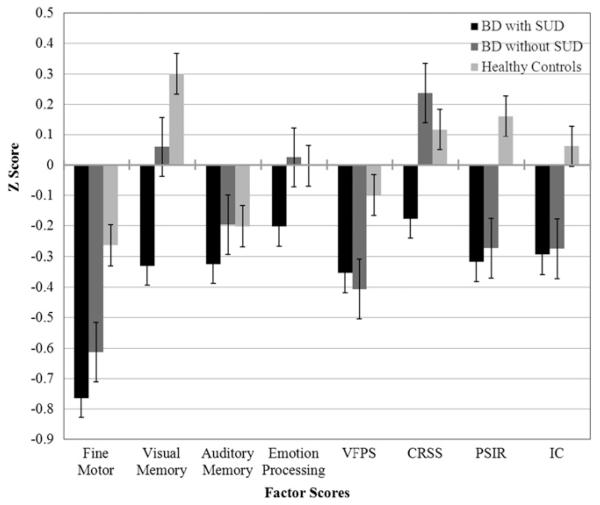

MANCOVA was computed with the eight factor scores as dependent variables (DV) and the three groups as independent variables (IV). Table 2 includes the means/standard deviations between the three groups for each of the eight factor scores and this is also illustrated in Fig. 1. The BD groups taken together exhibited poorer performance than the HC group on most cognitive factors, including fine motor dexterity, F (2, 278) = 10.32, p<.001, visual memory, F (2, 278)=8.84, p = 0.001, verbal fluency and processing speed, F (2, 278)=4.69, p = 0.01, conceptual reasoning and set-shifting, F (2, 278) = 9.68, p = 0.001, processing speed with interference resolution, F (2, 278)=15.88, p<001, and inhibitory control, F (2, 278)=5.50, p = 0.007. comparisons showed that the BD with Pairwise SUD exhibited significantly poorer performance than BD without SUD in visual memory and conceptual reasoning/set-shifting (ps<0.01).

Table 2.

Means of factor scores in bipolar patients with and without a history of substance use disorder and in healthy controls.

| Variable | BD with SUD M(S.D.) |

BD without SUD M(S.D.) |

Controls M(S.D.) |

p Post hoc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fine motor | −0.8 (0.9) | −0.6 (0.9) | −0.3 (0.9) | <0.001 HC>BD, BD+SUD |

| Visual memory | −0.3 (1.1) | 0.1 (1.0) | 0.3 (1.0) | 0.001 HC, BD>BD+SUD |

| Auditory memory | −0.3 (0.8) | −0.2 (0.6) | −0.2 (0.6) | 0.36 n.s. |

| Emotion processing | −0.2 (0.9) | 0.03 (0.7) | −0.003 (0.7) | 0.18 n.s. |

| VFPS | −0.4 (0.7) | −0.4 (0.8) | −0.1 (0.7) | 0.01 HC>BD |

| CRSS | −0.2 (0.9) | 0.2 (0.3) | 0.1 (0.6) | 0.001 HC, BD>BD+SUD |

| PSIR | −0.3 (0.7) | −0.3 (0.6) | 0.2 (0.5) | <0.001 HC>BD, BD+SUD |

| Inhibitory control | −0.3 (0.8) | −0.3 (0.8) | 0.1 (0.7) | 0.007 HC>BD, BD+SUD |

VFPS=Verbal Fluency and Processing Speed; CRSS=Conceptual Reasoning and Set-Shifting; PSIR=Processing Speed and Interference Resolution.

Fig. 1.

Factor scores in bipolar patients with and without a history of Substance Use Disorder and in healthy controls.

3.2. Relationship between substance use and depression on cognitive factor scores among just the bipolar participants

We tested whether differences between individuals with BD with and without SUD were accounted for by current depression (i.e., with, without significant depressive symptoms). There was a significant main effect of SUD on visual memory, F (1, 220) = 5.70, p =.02. Specifically, those with SUD had poorer performance (M=−0.47, S.D.=1.08) than those without SUD (M =−0.10, S.D.=1.1). There was also a significant main effect of SUD on conceptual reasoning/set-shifting F (1, 198)=13.81, p<0.001. Those with SUD demonstrated poorer performance (M =−0.19, S.D. = 0.88) compared to those without SUD (M = 0.21, S.D. = 0.39). There were no significant main effects of depression for any of the eight cognitive factor scores (ps>0.05).

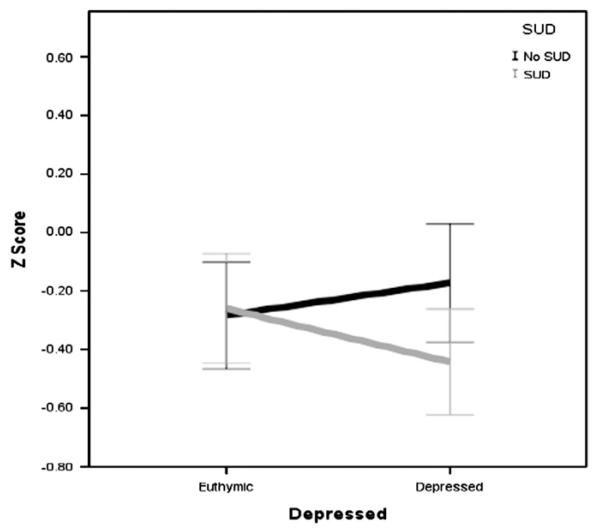

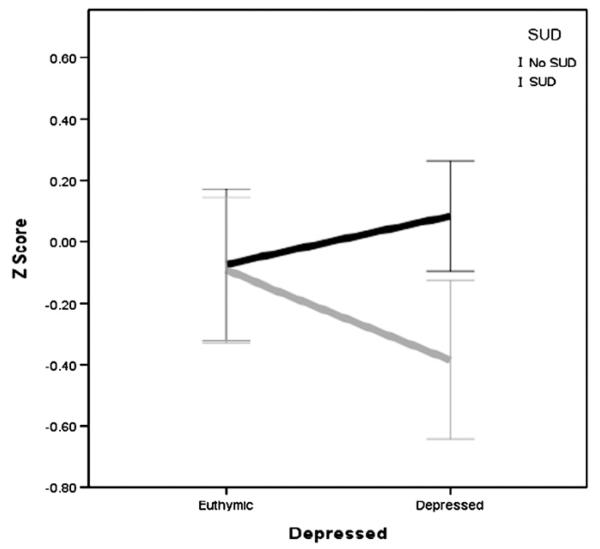

There was a significant interaction effect between SUD and depression on auditory memory F (1, 220) = 4.40, p = .04, which is illustrated in Fig. 2. Those with and without SUD were affected differently by mood state. Specifically, those with SUD and with depression (M =−0.44, S.D. = 0.75) had poorer performance compared to those with SUD and without depression (M=−0.26, S.D.=0.75), without SUD and without depression (M=−0.28, S.D.=0.62), and with depression and without SUD (M =−0.17, S.D.=0.64). There was also a significant interaction between SUD and depression on emotion processing F (1, 204) = 3.91, p=.05, which is illustrated in Fig. 3. Specifically, those with SUD and with depression (M =−0.38, S.D.=1.01) had poorer performance compared to those without SUD and without depression (M =−0.08, S.D.=0.83), SUD and without depression (M =−0.09, S.D. = 0.91), and with depression and without SUD (M = 0.08, S.D. = 0.55).

Fig. 2.

Interaction effect of SUD and depression on auditory memory in BD subjects only.

Fig. 3.

Interaction effect of SUD and depression on emotion processing in BD subjects only.

4. Discussion

Our results confirm that significant impairment in cognitive functioning exists in Bipolar Disorder, as both BD groups demonstrated poorer performance than the HC group on most cognitive factors, including psychomotor speed and dexterity, visual memory, verbal fluency and processing speed, conceptual reasoning and set-shifting, processing speed with interference resolution, and inhibitory control. These results extend our previous work with the initial sample of individuals recruited by capturing the poorer performance in the domain of inhibitory control (Langenecker et al., 2010).

In support of our hypothesis, BD patients with a lifetime history of comorbid SUD showed significantly worse visual memory and conceptual reasoning above and beyond the dysfunction observed in these factors in BD without SUD. This finding suggests that SUD has diffuse impact on integrated gestalt oriented functions more so then specific cognitive domains. Our results remained as stated even after evaluating the additional influence of current depressive symptoms, suggesting that it may be a more stable feature of comorbidity. Our results suggest that such deficits cannot be entirely explained by state factors such as depression, which is consistent with previous research showing that SUD is associated with significant neuropsychological deficits even after prolonged abstinence (Adams et al., 1980; Grant et al., 1984; Parsons, 1998), including impaired function of cerebral tissue in the medial frontal region (Adams et al., 1993). Similarly, Robinson and Kolb (2004) reported that exposure to amphetamine, cocaine, nicotine, or morphine produces perpetual changes in the structure of dendrites and dendritic spines on cells in brain regions involved in incentive motivation and reward, as well as judgment and inhibitory control even after discontinued use of the drug; thus, suggesting that drugs of abuse create a persistent reorganization of patterns of synaptic connectivity in these brain regions.

There was also an interaction between a history of substance use and current significant depressive symptoms on auditory memory and emotion processing. Individuals with current significant depressive symptoms in the context of lifetime history of SUD had poorer auditory memory and emotion processing than did individuals with either depression or SUD alone. This finding suggests that SUD may potentiate the impact of depression during the active phase of illness in BD while weakening cognitive reserve in the key areas responsible for auditory memory and emotion processing. These state effects are consistent with prior research by our group and others and help to further disambiguate the impact of state and trait features of mood disorders (Langenecker et al., 2005, Langenecker et al., 2007, Considine et al., 2011).

There were also clinical and demographic features of the comorbid BD and SUD group that are noteworthy. Individuals with BD and SUD had an earlier age of onset of illness, earlier age at first depressive episode, and also had more self-reported manic episodes. These findings suggest that individuals with BD with a history of comorbid SUD have a more chronic and severe course of illness, which is consistent with previous research showing that a history of SUD is predictive of a poorer future course of Bipolar Disorder (Gaudiano et al., 2008; Jaworski et al., 2011). Moreover, it was found that nearly half of our BD with SUD sample (47.5%) had a history of abusing multiple substances, which is consistent with previous studies (Goldberg et al., 1999), while also lending support to the notion that those BD with SUD exhibit greater risk-taking behaviors (e.g., abusing multiple substances). In addition, these findings raise some degree of doubt as to the genesis of comorbidity-related, and greater, difficulties in visual memory and conceptual reasoning/set-shifting. Without a longitudinal study, we cannot comment on the relative influence of genetic factors, illness severity, substance abuse, and/or manic episodes in relation to greater memory and executive dysfunction. Earlier treatments directed towards those with recent onset of illness, in a longitudinal design could help clarify the origin, either unique or combined, of these specific areas of cognitive weaknesses.

The current study has several strengths and limitations. A major strength is the large, well-powered sample size of the carefully characterized patient group. Our sample is considerably larger than any that has previously been examined in related investigations and lends support to the generalizability of our findings. Although we observed demographic differences (e.g., education and gender) between the BD groups in the course of this naturalistic, observational study, when we statistically examined the impact of each of these potential confounds, their impact on results were not significant. Moreover, the groups did not differ in a crystalized, “hold” measure of cognitive ability (i.e., Wechsler Vocabulary score). As such, the educational attainment differences may have been influenced by the early course of illness, as opposed to innate cognitive abilities at the time of schooling. However, demographic differences cannot be definitively excluded from explanatory consideration via the methods we have employed (Adams et al., 1985; Lord, 1967, 1969). An additional limitation of the current study is our inability to fully rule-out the impact of medication on cognitive functioning within our sample. However, no differences were detected between the two BD groups in medication load, suggesting that any differences in cognitive functioning are not likely attributable to medication side-effects. Another important limitation of the study is the cross-sectional design, which prevents examination of intra-individual differences in cognitive functioning over time. To address limitations of the current study, future research might address longitudinal outcome as a function of BD, SUD, and combined BD/SUD to evaluate neural systems involved in risk for and effects of these illnesses. Such methodology would also allow for more thorough examination of the risks and effects comprised by both cognitive and affective factors. We were unable to investigate the effects of specific substances within our current sample, given that nearly half were abusing multiple substances. However, from the foundation of this well-powered study of bipolar disorder and SUD, in general, future research might address the impact of specific substances. Legality, class of drugs (e.g., stimulant, depressant), length of abuse/dependence, and duration of recovery from SUD are all clinical factors that may impact cognitive and affective sequelae and therefore warrant further investigation.

Overall, our findings support the presence of persistent cognitive dysfunction, especially within integrated brain networks, as well as a more chronic course in euthymic BD with a history of SUD. With regard to clinical practice, our results highlight the need of additional screening and monitoring of individuals who are at risk of abusing substances, as early identification could provide additional interventions and resources which might mitigate the long term cognitive effects of these conditions.

Acknowledgments

Support provided by Heinz C. Prechter Bipolar Research Fund- University of Michigan and K23 Award (MH074459, SAL).

References

- Adams KM, Grant I, Reed R. Neuropsychology in alcoholic men in their late thirties: One year follow-up. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1980;137:928–931. doi: 10.1176/ajp.137.8.928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams KM, Brown GG, Grant I. Analysis of covariance as a remedy for demographic mismatch of research subject groups: Some sobering simulations. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 1985;7:445–462. doi: 10.1080/01688638508401276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams KM, Gilman S, Koeppe RA, Kluin KJ, Brunberg JA, Dede D, Berent S, Kroll PD. Neuropsychological deficits are correlated with frontal hypometabolism in positron emission tomography studies of older alcoholic patients. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1993;17:205–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1993.tb00750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida JRC, Akkal D, Hassel S, Travis MJ, Banihashemi L, Kerr N, Kupfer DJ, Phillips ML. Reduced gray matter volume in ventral prefrontal cortex but not amygdala in bipolar disorder: Significant effects of gender and trait anxiety. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging. 2009;171:54–68. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angst F, Stassen HH, Clayton PJ, Angst J. Mortality of patients with mood disorders: follow-up over 34-38 years. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2002;68:167–181. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(01)00377-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armitage SG. An analysis of certain psychological tests used in the evaluation of brain injury. Psych Mono. 1946;60:1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Benton A, Hamsher K. Multilingual Aphasia Examination. The University of Iowa; Iowa City, IA: 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy F, Ahearn EP, Carroll BJ. Substance abuse in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disorders. 2001;3:181–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Considine CM, Weisenbach SL, Walker SJ, McFadden EM, Franti LM, Bieliauskas LA, Maixner DF, Giordani B, Berent S, Langenecker SA. Auditory memory decrements, without dissimulation, among patients with major depressive disorder. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 2011;26:445–453. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acr041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis JM, Chen N. Dose response and dose equivalence of antipsychotics. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2004;24:192–208. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000117422.05703.ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delis D, Kaplan E, Kramer J, Ober B. California verbal learning test-II. 2000. The Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Gaudiano BA, Uebelacker LA, Miller IW. Impact of remitted substance use disorders on the future course of bipolar I disorder: Findings from a clinical trial. Psychiatry Research. 2008;160:63–71. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2007.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg JF, Garno JL, Leon AC, Kocsis JH, Portera L. A history of substance abuse complicates remission from acute mania in bipolar disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1999;60:733–740. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v60n1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden C. Stroop Color and Word Test. Stoelting; Chicago, IL: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Grant DA, Berg EA. A behavioral analysis of degree of reinforcement and ease of shifting to new responses in a Weigl-type card sorting paradigm. Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1948;38:404–411. doi: 10.1037/h0059831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant I, Adams KM, Reed R. Aging, abstinence and medical risk factors in the prediction of neuropsychological deficit amongst chronic alcoholics. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1984;41:710–718. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1984.01790180080010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green PW, Allen LM. The Emotional Perception Test. CogniSyst Inc.; Durham, NC: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Hassel S, Almeida JRC, Kerr N, Nau S, Ladouceur CD, Fissell K, Kupfer DJ, Phillips ML. Elevated striatal and decreased dorsolateral prefrontal cortical activity in response to emotional stimuli in euthymic bipolar disorder: no associations with psychotropic medication load. Bipolar Disorders. 2008;10:916–927. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2008.00641.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes KM, Bearden CE, Barguil M, Fonseca M, Monkul E, Nery FG, Soares JC, Mintz J, Glahn DC. Conceptualizing impulsivity and risk taking in bipolar disorder: importance of history of alcohol abuse. Bipolar Disorders. 2009;11:33–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2008.00657.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaworski F, Dubertret C, Ades J, Gorwood P. Presence of co-morbid substance use disorder in bipolar patients worsens their social functioning to the level observed in patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Research. 2011;185:129–134. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime Prevalence and Age-of-Onset Distributions of DSM-IV Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Kendler KS. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1994;51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagerberg T, Andreassen O, Ringen P, Berg A, Larsson S, Agartz I, Sundet K, Melle I. Excessive substance use in bipolar disorder is associated with impaired functioning rather than clinical characteristics, a descriptive study. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10:9. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-10-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langenecker SA, Bieliauskas LA, Rapport LJ, Zubieta J-K, Wilde EA, Berent S. Face Emotion Perception and Executive Functioning Deficits in Depression. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2005;27:320–333. doi: 10.1080/13803390490490515720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langenecker SA, Zubieta JK, Young EA, Akil H, Nielson KA. A task to manipulate attentional load, set-shifting, and inhibitory control: Convergent validity and test-retest reliability of the Parametric Go/No-Go Test. J Clin Experimental Neuropsychology. 2007;29(8):842–853. doi: 10.1080/13803390601147611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langenecker SA, Saunders EFH, Kade AM, Ransom MT, McInnis M. Intermediate cognitive phenotypes in bipolar disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2010;122:285–293. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy B, Monzani BA, Stephansky MR, Weiss RD. Neurocognitive impairment in patients with co-occurring bipolar disorder and alcoholdependence upon discharge from inpatient care. Psychiatry Research. 2008;161:28–35. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lezak M. Neuropsychological Assessment-Third Edition. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Lord FM. A paradox in the interpretation of group comparisons. Psychological Bulletin. 1967;68:304–305. doi: 10.1037/h0025105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord FM. Statistical adjustments when comparing preexisting groups. Psychological Bulletin. 1969;72:337–338. [Google Scholar]

- Martin C, Earleywine M, Blackson T, Vanyukov M, Moss H, Tarter R. Aggressivity, inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity in boys at high and low risk for substance abuse. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1994;22:177–203. doi: 10.1007/BF02167899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, Akiskal HS, Angst J, Greenberg PE, Hirschfeld RMA, Petukhova M, Kessler RC. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorder in the national comorbidity survey replication. Archives of general psychiatry. 2007;64:543–552. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers J, Meyers K. Rey complex figure and recognition trial: professional manual. Psychological Assessment Resources; Odessa, FL: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Nurnberger JI, Jr., Blehar MC, Kaufmann CA, York-Cooler C, Simpson SG, Harkavy-Friedman J, Severe JB, Malaspina D, Reich T. Diagnostic interview for genetic studies. Rationale, unique features, and training. NIMH Genetics Initiative. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1994;51:849–859. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950110009002. discussion 863-844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons OA. Neurocognitive deficits in alcoholics and social drinkers: a continuum? Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1998;22:954–961. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapport LJ, Friedman S, Tzelepis A, Van Voorhis A. Experienced emotion and effect recognition in adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Neuropsychology. 2002;16:102–110. doi: 10.1037//0894-4105.16.1.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS. Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse: results from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) study. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1990;264:2511–2518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TE, Kolb B. Structural plasticity associated with exposure to drugs of abuse. Neuropharmacology. 2004;47(Supplement 1):33–46. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson LJ, Thompson JM, Gallagher P, Goswami U, Young AH, Ferrier IN, Moore PB. A meta-analysis of cognitive deficits in euthymic patients with bipolar disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2006;93:105–115. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sackheim H. The definition and meaning of treatment resistant depression. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2001;62(Suppl 16):10–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Moreno J, Martinez-Aran A, Colom F, Scott J, Tabares-Seisdedos R, Sugranyes G, Torrent C, Daban C, Benabarre A, Goikolea JM, Franco C, Gonzalez-Pinto A, Ayuso-Mateos JL, Vieta E. Neurocognitive Dysfunctions in Euthymic Bipolar Patients With and Without Prior History of Alcohol Use. Physicians Postgraduate Press; Memphis, TN, ETATS-UNIS: 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sattler JM. In: Assessment of Children: Cognitive Applications. Fourth ed. Sattler Jerome M., editor. Publisher, Inc; La Mesa: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JM, Gallagher P, Hughes JH, Watson S, Gray JM, Ferrier IN, Young AH. Neurocognitive impairment in euthymic patients with bipolar affective disorder. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;186:32–40. doi: 10.1192/bjp.186.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres IJ, Boudreau VG, Yatham LN. Neuropsychological functioning in euthymic bipolar disorder: a meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2007;116:17–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.01055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Werf-Eldering MJ, Burger H, Holthausen EAE, Aleman A, Nolen WA. Cognitive functioning in patients with bipolar disorder: association with depressive symptoms and alcohol use. PLoS One. 2010:5. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Gorp W, Altshuler L, Theberge DC, Wilkins J, Dixon W. Cognitive impairment in euthymic bipolar patients with and without prior alcohol dependence. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55:41–46. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-III. Psychological Corp.; Cleveland, OH: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Zubieta J-K, Huguelet P, O’Neil RL, Giordani BJ. Cognitive function in euthymic bipolar I disorder. Psychiatry Research. 2001;102:9–20. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(01)00242-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]