Abstract

Bacillus subtilis transports β-glucosides such as salicin by a dedicated phosphotransferase system (PTS). The expression of the β-glucoside permease BglP is induced in the presence of the substrate salicin, and this induction requires the binding of the antiterminator protein LicT to a specific RNA target in the 5′ region of the bglP mRNA to prevent the formation of a transcription terminator. LicT is composed of an N-terminal RNA-binding domain and two consecutive PTS regulation domains, PRD1 and PRD2. In the absence of salicin, LicT is phosphorylated on PRD1 by BglP and thereby inactivated. In the presence of the inducer, the phosphate group from PRD1 is transferred back to BglP and consequently to the incoming substrate, resulting in the activation of LicT. In this study, we have investigated the intracellular localization of LicT. While the protein was evenly distributed in the cell in the absence of the inducer, we observed a subpolar localization of LicT if salicin was present in the medium. Upon addition or removal of the inducer, LicT rapidly relocalized in the cells. This dynamic relocalization did not depend on the binding of LicT to its RNA target sites, since the localization pattern was not affected by deletion of all LicT binding sites. In contrast, experiments with mutants affected in the PTS components as well as mutations of the LicT phosphorylation sites revealed that phosphorylation of LicT by the PTS components plays a major role in the control of the subcellular localization of this RNA-binding transcription factor.

INTRODUCTION

The heterotrophic soil bacterium Bacillus subtilis lives in an environment that strongly fluctuates with respect to nutrient availability. To cope with this challenge, B. subtilis is able to select from a large variety of potential substrates the carbon source that is most advantageous for growth and propagation. In B. subtilis and many other bacteria, the phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP)-dependent sugar phosphotransferase system (PTS) is the key player in the regulated transport and catabolism of carbohydrates (1, 2). The PTS comprises a family of carbohydrate-specific transport proteins collectively called enzymes II (EIIs). The driving force for transport is provided by phosphorylation of the substrate during its uptake. The phosphoryl groups are derived from PEP and are delivered to the EIIs via the sequential (de)phosphorylation of the two general PTS proteins enzyme I (EI) and histidine protein (HPr) at histidine residues. The EIIs are composed of the two cytoplasmic EIIA and EIIB domains and of the EIIC domain, which forms the membrane channel. HPr donates the phosphoryl groups to a histidine residue in the IIA domain, from which it is transferred to a cysteine or histidine residue in the EIIB domain and subsequently to the translocated sugar.

The expression of the functions required for transport and utilization of a particular PTS sugar is usually strictly controlled by dedicated regulatory proteins. The regulation of PTS operons may take place at the level of transcription initiation by repressors or activators or by controlling transcript elongation by RNA-binding antitermination proteins that modulate RNA structures (1, 3). BglG-type transcriptional antitermination proteins represent a widespread family of regulators that control and are controlled by PTS proteins (1, 4, 5). The antitermination proteins bind a conserved RNA antiterminator sequence (RAT) in their target RNAs and thereby prevent the formation of a transcriptional terminator leading to expression of the target genes (6, 7). The antiterminator proteins are composed of an N-terminal RNA-binding domain followed by two iterative PTS regulatory domains (PRDs), which receive information about carbohydrate availability from the PTS proteins (4, 8). B. subtilis contains four antiterminator proteins of the BglG family, including the well-characterized LicT protein. LicT regulates expression of the bglPH operon, encoding the β-glucoside-specific EII transporter BglP and the phospho-β-glucosidase BglH, and of the bglS gene, which codes for a β-d-glucanase (9, 10, 11). In the absence of β-glucosides such as salicin, BglP inactivates LicT by its phosphorylation on histidine residues 100 and 159, located in the first PRD (PRD1). The phosphoryl groups are transferred back to BglP, if a substrate becomes available. However, to gain antitermination activity, LicT additionally requires phosphorylation by HPr, which takes place at histidine residues 207 and 269, located in the second PRD (PRD2) (12, 13). The latter phosphorylation/dephosphorylation is involved in carbon catabolite regulation downregulating LicT when preferred PTS sugars become available. Structural analysis suggests that phosphorylation of PRD2 stabilizes the active LicT dimer through contacts at the PRD interfaces (14, 15). In contrast, phosphorylation of PRD1 leads to inactivation of LicT, presumably due to its monomerization (1, 8). Comparable regulatory mechanisms, involving antagonistically acting phosphorylations catalyzed by a cognate EII and HPr, were also proposed for the homologous proteins SacT and GlcT from B. subtilis and BglG from Escherichia coli (16, 17, 18).

In recent years it has been learned that bacterial cells exhibit a highly complex spatial organization which is often dynamic (19). For instance, a rapidly growing number of bacterial proteins are reported to localize in rings, foci, helices, or clusters at specific intracellular sites. These architectures, which often undergo a spatiotemporal dynamics, underlie various cellular activities, including protein complex formation and cross talk between cellular machineries. Recently, it has been suggested that the PTS is also spatially organized. Depending on the experimental setup and the growth conditions, the general PTS enzymes, EI and HPr, were found to localize to the cell poles, clustered in the cytoplasm or dispersed throughout the cell in E. coli (20, 21, 22). An even more complex spatiotemporal localization pattern was reported for the E. coli BglG protein, which controls the β-glucoside utilization genes in E. coli and is the functional counterpart of LicT. When not occupied with transport, the cognate PTS transporter BglF phosphorylates and concomitantly sequesters BglG at the inner face of the cytoplasmic membrane (23). Following the addition of a substrate for BglF, the BglG protein is released and migrates to the cell poles, where it undergoes HPr-dependent activation (20, 24), which involves its phosphorylation (18). Subsequently, BglG migrates to the cytoplasm, where it catalyzes antitermination at the bgl operon. Sequestration by the cognate transport protein at the membrane has also been observed for a few other transcriptional regulators controlling carbohydrate utilization genes. Similar to BglG, the transcriptional activator protein MalT, controlling maltose utilization in E. coli, is inactivated through sequestration by the resting maltose transporter (25). In contrast, the Mlc repressor protein, which controls multiple PTS functions in E. coli, is recruited to the membrane through interaction with the translocating glucose transporter (26). An unusual mode of membrane sequestration has recently been revealed for the transcriptional activator protein MtlR in B. subtilis (27). MtlR, which controls the mannitol utilization genes, contains two PRDs followed by EIIB- and EIIA-like domains. On the one hand, the activity of MtlR is controlled by multiple PTS-catalyzed phosphorylations at its PRD2 and the EIIB-like domain. However, to gain activity, MtlR must also interact via its C-terminal EIIA-like domain with the translocating mannitol-specific EII.

In this study, we investigated the localization of the antiterminator protein LicT in B. subtilis. We observed that inactive LicT is not sequestered at the membrane by its cognate transporter BglP but is evenly distributed in the cytoplasm. Upon activation, LicT rapidly relocalizes to subpolar regions independent of the presence of its RNA targets. In conclusion, LicT undergoes a dynamic relocalization in the cell that correlates with its activity and depends on its phosphorylation status. The localization of LicT drastically differs from that reported for its homolog BglG in E. coli, suggesting species-specific localization traits. This conclusion is supported by our observation that EI of the PTS is evenly distributed in the B. subtilis cell independent of PTS transport activity, while it was reported to localize to the cell poles in E. coli.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

The B. subtilis strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. E. coli DH5α (28) was used for plasmid constructions and transformation using standard techniques (28).

Table 1.

B. subtilis strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Source or referencea |

|---|---|---|

| 168 | trpC2 | Laboratory collection |

| GM1112 | sacXYΔ3 sacBΔ23 sacTΔ4 bglP::Tn10 (cat::ery) amyE(sacB::lacZ Phlr) | 9 |

| GP427 | trpC2 ΔlicTS::ermC | 7 |

| GP475 | trpC2 ΔbglP::ermC | GM1112 → 168 |

| GP1225 | trpC2 licT-gfp spc | pGP1292 → 168 |

| GP1229 | trpC2 licT-yfp spc | pGP1296 → 168 |

| GP1236 | trpC2 ΔbglP::erm licT-gfp spc | GP475 → GP1225 |

| GP1242 | trpC2 amyE::(bglP-lacZ phl) licT-gfp spc | GP1225 → QB5335 |

| GP1243 | trpC2 amyE::(bglP-lacZ phl) licT-yfp spc | GP1229 → QB5335 |

| GP1245 | trpC2 amyE::(bglP-lacZ phl) ΔlicTS::ermC | GP427 → QB5335 |

| GP1257 | ΔptsH::cat licT-gfp spc | pGP1292 → MZ303 |

| GP1258 | trpC2 licT (H100A)-gfp spc | pGP1306 → 168 |

| GP1259 | trpC2 licT (H207A)-gfp spc | pGP1307 → 168 |

| GP1260 | trpC2 licT (H100A/H207A)-gfp spc | pGP1308 → 168 |

| GP1261 | trpC2 ΔRATbglS::cat | This work |

| GP1262 | trpC2 ΔRATbglP::kan | This work |

| GP1263 | trpC2 ΔRATbglS::cat ΔRATbglP::kan | GP1262 → GP1261 |

| GP1264 | trpC2 ΔRATbglS::cat ΔRATbglP::kan licT-gfp spc | pGP1292 → GP1263 |

| GP1266 | trpC2 bglP-cfp ermC | This work |

| GP1267 | trpC2 ptsH-cfp ermC | This work |

| GP1268 | trpC2 ptsI-cfp ermC | This work |

| MZ303 | ΔptsH::cat | 16 |

| QB5335 | trpC2 amyE::(bglP-lacZ phl) | 36 |

Arrows indicate construction by transformation.

Luria-Bertani (LB) broth was used to grow E. coli and B. subtilis. When required, media were supplemented with antibiotics at the following concentrations: ampicillin, 100 μg ml−1 (for E. coli); spectinomycin, 150 μg ml−1; kanamycin, 7.5 μg ml−1; phleomycin, 6 μg ml−1; chloramphenicol, 5 μg ml−1; and erythromycin plus lincomycin, 2 and 25 μg ml−1, respectively (for B. subtilis).

B. subtilis was grown in C minimal medium supplemented with auxotrophic requirements (at 50 mg l−1) as indicated below (29), and carbon sources were used at a concentration of 0.5% (wt/vol) unless stated otherwise. The basal medium used in this study, CSE, is C minimal medium supplemented with succinate and glutamate (29). Sporulation (SP) plates were prepared by the addition of 15 g l−1 Bacto agar (Difco) to sporulation medium (8 g of nutrient broth per liter, 1 mM MgSO4, and 13 mM KCl, supplemented after sterilization with 2.5 μM FeSO4, 500 μM CaCl2, and 10 μM MnCl2).

Transformation and enzyme assays.

Chromosomal DNA of B. subtilis was isolated using the DNeasy tissue kit (Qiagen) according to the supplier's protocol. B. subtilis was transformed with plasmids and chromosomal DNA according to the two-step protocol (30). Transformants were selected on SP plates containing antibiotics as described above. For enzyme assays, cells were harvested in the exponential growth phase at an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.6 to 0.8.

Quantitative studies of lacZ expression in B. subtilis were performed as follows. Cells were grown in LB medium and harvested at an OD600 of 0.6 to 0.8. β-Galactosidase specific activities were determined with cell extracts obtained by lysozyme treatment as described previously (30). One unit of β-galactosidase is defined as the amount of enzyme which produces 1 nmol of o-nitrophenol per min at 28°C.

Plasmid constructions.

To facilitate the fusion of B. subtilis proteins to the green and yellow fluorescent proteins (GFP and YFP, respectively), we constructed the plasmids pGP1870 and pGP1871, respectively. For this purpose, we amplified the gfp and yfp gene fragments using the primer pairs ML220/ML221 and ML222/ML223 and plasmids pSG1151 (31) and pIYFP (32) as the templates, respectively. The amplicons were digested with HindIII and cloned into the vector pUS19 (33). The vectors pGP1870 and pGP1871 allow the construction of GFP/YFP fusions and integration of the plasmid into the chromosome via Campbell-type recombination between the cloned gene fragment and the chromosomal copy of the gene (see http://www.subtiwiki.uni-goettingen.de/wiki/index.php/PGP1870 and http://www.subtiwiki.uni-goettingen.de/wiki/index.php/PGP1871).

To fuse the LicT protein to the green and yellow fluorescent proteins, we amplified the 3′ 600 bp of the licT gene lacking a stop codon using the primer pair FR114/FR115 and chromosomal DNA of B. subtilis 168 as the template and cloned the amplicon between the BamHI and SalI sites of pGP1870 and pGP1871, respectively. The resulting plasmids were pGP1292 (licT-gfp) and pGP1296 (licT-yfp). Integration of these plasmids into the chromosome of B. subtilis leads to the in-frame fusion of the gfp or yfp alleles to the entire licT gene lacking its stop codon. To fuse mutant variants of LicT to GFP, PCR-based mutagenesis (34) was performed to obtain the alleles coding for LicT(H100A), LicT(H207A), and LicT(100A 207A). For this purpose, the licT gene was amplified using the outer primer pair FR162/FR115 and the mutagenesis primers FR164 ([for LicT(H100A)] and FR163 [for LicT(H207A)]. The mutated alleles were cloned between the BamHI and SalI sites of pGP1870, giving pGP1306 and pGP1307. To obtain the double mutant allele, pGP1306 was used as the template in the mutagenesis PCR and FR163 as the mutagenesis primer. After cloning of the fragment into pGP1870, the resulting plasmid was pGP1308.

Strain construction by long flanking homology PCR mutagenesis.

To replace the RNA antiterminator (RAT) sequences of the bglP and licS genes with terminatorless kanamycin and chloramphenicol resistance cassettes, we generated PCR products using oligonucleotides (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) to amplify DNA fragments flanking the RAT sequences and intervening antibiotic resistance cassettes as described previously (35). These PCR products were directly used to transform B. subtilis strains.

To fuse the PTS components to the cyan fluorescent protein (CFP), we performed a fusion PCR with amplicons of the B. subtilis chromosomal bglP gene, of the cfp ermC cassette amplified from plasmid pBP20 (K. Gunka and F. M. Commichau, unpublished data), and of the downstream bglH gene. In a similar way, we obtained a fusion PCR product that allowed the construction of a ptsH-cfp strain. To avoid interference with the expression of the downstream bglH and ptsI genes, respectively, the terminator downstream of the ermC gene was omitted in the PCR. For the generation of a ptsI-cfp strain, we used the same procedure, but in this case the ermC terminator was included.

Western blotting.

For Western blot analysis, proteins were separated by 12% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Bio-Rad) by electroblotting. Rabbit anti-GFP polyclonal antibodies (Biozol, Eching, Germany; 1:10,000) served as primary antibodies. The antibodies were visualized by using anti-rabbit immunoglobulin alkaline phosphatase secondary antibodies (Promega) and the CDP-Star detection system (Roche Diagnostics), as described previously (29).

Microscopy.

For fluorescence microscopy, cells were grown in CSE, CSE-salicin (0.1% [wt/vol]), or CSE-sorbitol (0.5% [wt/vol]) medium to an OD600 of 0.3 to 0.4, harvested, and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.5; 50 mM). Fluorescence images were obtained with an Axioskop 40 FL fluorescence microscope, equipped with digital camera AxioCam MRm and AxioVision Rel 4.8 software for image processing (Carl Zeiss, Göttingen, Germany) and Neofluar series objective at a primary magnification of ×100. The applied filter sets were the YFP HC-Filterset (BP, 500/24; FT, 520; LP, 542/27; AHF Analysentechnik, Tübingen, Germany) for YFP detection, the eGFP HC-Filterset (BP, 472/30; FT, 495; LP, 520/35; AHF Analysentechnik) for eGFP detection, filter set 47 (BP, 436/20; FT, 455; LP, 480/40; Carl Zeiss) for CFP visualization, and filter set 49 (G, 365; FT, 395; LP, 445/50; Carl Zeiss) for 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) visualization. The overlays of fluorescent and phase-contrast images were prepared for presentation with Adobe Photoshop Elements 8.0 (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA).

RESULTS

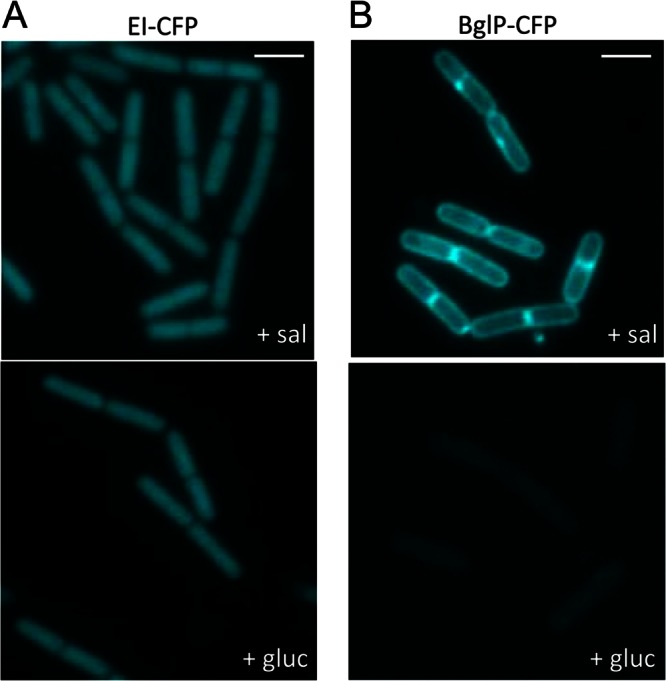

Localization of PTS proteins involved in salicin uptake.

Salicin is taken up by a phosphotransferase system composed of the general components enzyme I and HPr and the β-glucoside-specific permease BglP. To investigate the localization of these proteins, we constructed a set of strains expressing these PTS components fused to the cyan fluorescent protein at their C termini (Table 1). These fusion proteins were encoded at the authentic loci of the PTS components. Prior to the investigation of protein localization, we tested whether the fusion proteins were biologically active. For this purpose, we compared the growth of these strains on minimal medium containing glucitol, glucose, or salicin to that of wild-type B. subtilis 168. All strains grew well with the non-PTS carbon source glucitol. In contrast, the strain expressing the HPr-CFP protein (GP1267) did not grow on glucose and salicin, whereas the bacteria with enzyme I-CFP (GP1268) or BglP-CFP (GP1266) grew well in the presence of these carbon sources (data not shown). These results indicate that the tagged enzyme I and BglP proteins were active in the transport of glucose (enzyme I) and salicin (enzyme I and BglP), whereas the tagged HPr protein was unable to participate in PTS-dependent sugar uptake. This suggests that the HPr-CFP protein was inactive, and therefore, the following experiments were performed only with the strains expressing active fusion proteins.

To localize enzyme I and BglP, the strains GP1268 and GP1266 were grown in CSE minimal medium with salicin or glucitol as the carbon source. For enzyme I-CFP, a bright fluorescence that was evenly distributed in the cell was observed under both conditions (Fig. 1A). This result is in good agreement with the established constitutive expression of the ptsHI operon (36) and with the absence of a membrane anchor in enzyme I. For BglP, the result was different. This protein gave bright signals in the membrane region of the cell when the bacteria were grown in the presence of the BglP substrate, salicin. In contrast, only background signals were detected during growth with glucitol (Fig. 1B). These observations precisely matched our expectations since BglP is known to be the membrane-bound permease for salicin uptake, and its expression is strongly dependent on presence of the inducer salicin (9).

Fig 1.

Localization patterns of the PTS proteins involved in salicin uptake. Shown are fluorescence microscopy images of cells harboring a ptsI-cfp (GP1268) (A) or a bglP-cfp fusion (GP1266) (B) in the chromosome. Cells of GP1268 (EI-CFP) (A) and GP1266 (BglP-CFP) (B) were grown in CSE minimal medium with salicin (sal) or glucitol (gluc) and prepared for microscopy in the logarithmic phase of growth. Scale bars, 2 μm.

Localization of the antitermination protein LicT.

As stated above, the detection of BglP depended on the presence of salicin in the medium. This induction is controlled by the transcriptional antiterminator LicT, which in the presence of salicin binds the RAT sequence in the bglP leader mRNA in order to allow transcript elongation beyond the intrinsic terminator located in the leader region (9, 11). This prompted us to test the localization of the antiterminator protein LicT as well. For this purpose, we constructed strains with LicT fused to either the green or the yellow fluorescent protein (GP1225 and GP1229, respectively). To assess the activity of the LicT fusion proteins, we constructed a set of strains carrying a fusion of the LicT-regulated bglP promoter to a promoterless lacZ gene encoding β-galactosidase. The resulting strains were cultivated in minimal medium without an added sugar or in the presence of salicin or salicin and glucose. As shown in Table 2, no β-galactosidase activity was detectable with the wild-type strain in minimal medium without salicin. In the presence of salicin, the expression was induced to about 1,840 U per mg of protein. If both glucose and salicin were available, only 113 U of activity was detected. In the absence of a functional licT gene (GP1245), no bglP expression was observed under all conditions tested. These results are in excellent agreement with previous observations (37). They show the salicin-dependent induction as well as glucose-mediated carbon catabolite repression of LicT activity. Moreover, it is obvious that a functional licT gene is essential for the expression of bglP. The strains expressing the LicT fusion proteins exhibited an expression pattern of bglP that was very similar to that of the strain carrying the nontagged wild-type LicT protein (Table 2). Therefore, the fluorescently labeled LicT proteins have retained full activity in antitermination as well as the physiological control of their activity by PTS components.

Table 2.

Activities of LicT fusion proteins

| Strain | Relevant genotype | β-Galactosidase activity (U/mg of protein)a |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSE | CSE-Sal | CSE-Sal/Glc | ||

| QB5335 | Wild type | 0.5 ± 0.5 | 1,840 ± 61 | 113 ± 10 |

| GP1245 | ΔlicT | 2 ± 1 | 2 ± 0 | 1.5 ± 0.5 |

| GP1242 | licT-gfp | 3 ± 1 | 1,620 ± 100 | 75 ± 14 |

| GP1243 | licT-yfp | 2.5 ± 0.5 | 1,490 ± 85 | 90 ± 13 |

All measurements were performed at least in triplicate. Values are means ± standard deviations. Sal, salicin; Glc, glucose.

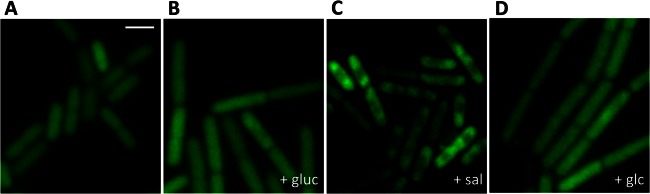

To study the localization of LicT, we grew strain GP1225 expressing LicT-GFP in CSE minimal medium without an added sugar or in the presence of glucitol, salicin, or glucose. The results are shown in Fig. 2. Generally, the fluorescence was much weaker than observed for the other fusions used in this study. This is in good agreement with the rather weak level of licT transcription (38). In the absence of any sugar as well as in the presence of the noninducing carbon sources glucitol and glucose, LicT was evenly distributed throughout the cell. In contrast, we observed an accumulation of the protein in the subpolar regions when the bacteria were grown in the presence of the inducer salicin, i.e., when LicT was active (Fig. 2C). Similar results were obtained with LicT fused to YFP (data not shown). These results suggest a correlation between LicT activity and its intracellular localization.

Fig 2.

The cellular localization of LicT correlates with its activity. Shown are fluorescence micrographs of GP1225 cells expressing a LicT-GFP fusion in the mid-logarithmic phase grown in CSE minimal medium without carbon sources (A) or with glucitol (gluc) (B), salicin (sal) (C), or glucose (glc) (D). Scale bar, 2 μm.

Dynamic relocalization of LicT upon a nutrient shift.

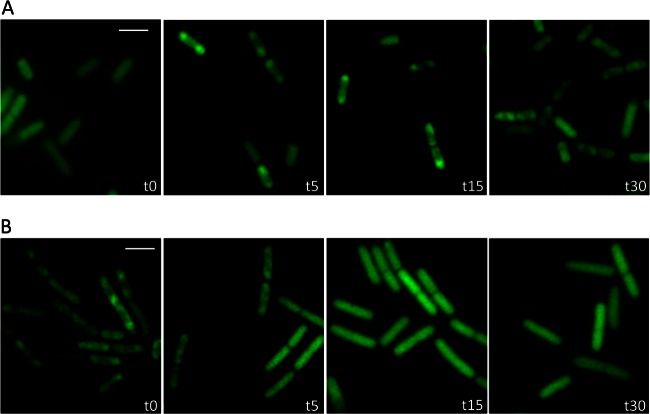

As shown above, the localization of LicT is controlled by the availability of the inducer salicin and is thus correlated to its activity in antitermination. If, in turn, the localization would reflect the activity of the protein, one would expect a rapid relocalization when the nutrient supply changes. To address this issue, we cultivated B. subtilis GP1225 expressing LicT-GFP in CSE minimal medium to the mid-logarithmic phase and transferred the bacteria to fresh medium containing the inducer salicin. The localization of LicT-GFP was analyzed prior to the shift and 5, 15, and 30 min after the addition of salicin. As shown in Fig. 3A, LicT was evenly distributed throughout the cell in the CSE medium. This result is in good agreement with the results described above (Fig. 2A). Five minutes after the nutrient shift, LicT started to concentrate in the subpolar regions of the cells. This process continued, and after 15 min the great majority of cells had LicT in the subpolar regions. The same localization was also observed 30 min after the nutrient shift.

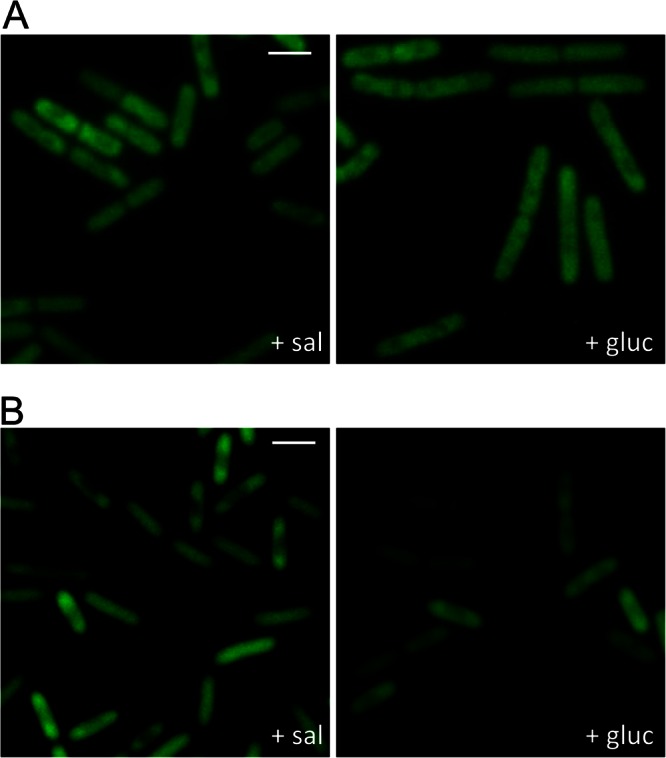

Fig 3.

Dynamic relocalization of LicT after a nutrient shift. (A) Cells of GP1225 (licT-gfp) were grown in CSE minimal medium without any carbohydrate, washed at time zero, and resuspended in CSE medium containing salicin. (B) GP1225 was grown in CSE minimal medium with salicin. At time zero, the cells were washed and resuspended in CSE with glucitol. Fluorescence microscopy images were taken at time zero and at 5, 15, and 30 min after the addition of the new medium. The scale bars correspond to 2 μm.

Next, we tested whether the LicT localization would also alter when cells are shifted from a medium with the inducer salicin to a medium without salicin. For this purpose, GP1225 was grown to the mid-logarithmic phase in CSE medium containing salicin. Then, the cells were washed and resuspended in fresh CSE medium containing glucitol. Again, the LicT localization was observed before and after the shift. As shown in Fig. 3B, LicT exhibited the subpolar localization typical for the active protein during growth with salicin. After the shift to glucitol-containing medium, the localization changed and eventually the protein was again homogeneously distributed in the cells as observed before for inactive LicT irrespective of the noninducing carbon source available. However, this delocalization of LicT was slower; only after 15 min did most cells exhibit the homogeneous distribution of LicT. The process was finished in the last sample analyzed 30 min after the medium shift.

Taken together, our results demonstrate that LicT changes its intracellular localization in response to the presence of the inducer salicin and the accompanying change in LicT activity.

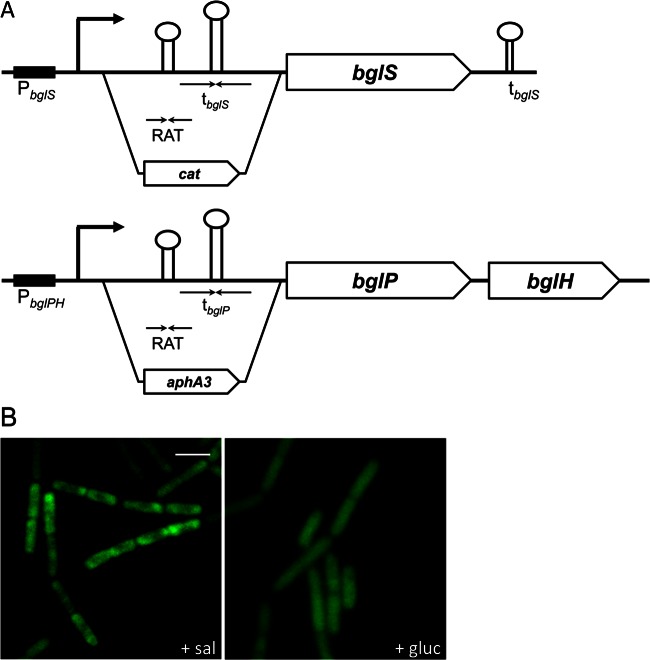

Role of the LicT RNA targets for the localization of LicT.

As reported above, active LicT concentrates in the subpolar regions of the cells, whereas inactive protein is homogeneously distributed. The active protein binds its RNA targets to prevent transcription termination of the controlled bglS and bglPH mRNAs (11). It is therefore conceivable that the active protein follows the localization of its target molecules. If this were the case, one would expect loss of inducer-dependent intracellular distribution of LicT in a strain that is devoid of LicT's target sites. To test this hypothesis, we deleted the regions corresponding to the RAT/terminator control regions of bglS and the bglPH operon in a way that did still allow expression of these genes (Fig. 4A). The resulting strain, GP1264, was grown in CSE medium with salicin or glucitol, and the localization of LicT-GFP was investigated. As shown in Fig. 4B, the intracellular distribution of LicT in this strain was indistinguishable from that in the wild type; i.e., the protein was concentrated in the subpolar regions during growth with salicin, whereas it was evenly distributed throughout the cell during growth with glucitol. This observation excludes the possibility that binding of LicT to its target RAT sequences modulates the localization of the protein.

Fig 4.

Effect of the LicT RNA targets on the subcellular localization of LicT. (A) Construction of strain GP1264 lacking the RNA binding sites of LicT. The RNA targets of LicT (RAT) and the overlapping terminator strucures (t) present in the leader regions of the bglS gene or the bglPH operon were replaced with a chloramphenicol (cat) or a kanamycin resistance (aphA3) gene, respectively. (B) Fluorescence microscopy images of GP1264 (licT-gfp ΔRAT). The cells were grown in CSE minimal medium with salicin or glucitol and prepared for microscopy in the logarithmic phase of growth. Scale bar, 2 μm.

Role of the PTS components in inducer-dependent LicT localization.

As demonstrated above, the localization of LicT correlates perfectly with its activity in antitermination. However, the localization of LicT does not follow its target RNA molecules and must therefore depend on other factors. It is well established that the activity of LicT is controlled by multiple PTS-dependent phosphorylation events. In the absence of the inducer, BglP phosphorylates LicT to inhibit its activity, whereas HPr can phosphorylate LicT in the absence of preferred carbon sources to stimulate the activity (12, 13). To analyze the implication of the PTS components in LicT localization, we constructed strains with deletions of either the bglP or the ptsH gene.

The mutant strains were grown in CSE minimal medium in the presence of salicin or glucitol. For the bglP mutant GP1236, we observed a subpolar localization of LicT in both media (Fig. 5A). Thus, the bglP mutant does not seem to be able to sense the presence or absence of the inducer salicin; indeed, the transduction of this information to LicT is the task of BglP. Thus, in the bglP mutant, the LicT protein is constitutively active (10), and it is always localized as the active protein. In the ptsH mutant lacking the general PTS protein HPr, no phosphorylation of LicT is possible since HPr can directly phosphorylate LicT, but it serves also as a phosphoryl group donor in the phosphorylation chain from BglP to LicT (9). In this mutant, the intracellular distribution of LicT was similar to that observed in the bglP mutant; i.e., LicT accumulated in the subpolar regions of the cells (Fig. 5B).

Fig 5.

Effects of PTS components on the LicT localization pattern. The B. subtilis ΔbglP mutant strain expressing a LicT-GFP fusion (GP1236) (A) and the ΔptsH mutant with a LicT-GFP fusion (GP1257) (B) were grown in CSE minimal medium containing 0.1% salicin or 0.5% glucitol. The fluorescence pictures were taken in the mid-logarithmic phase of growth. The scale bars correspond to 2 μm.

The results obtained with the PTS mutants suggest that it is not the activity of LicT that is important for the intracellular localization, since LicT is constitutively active in bglP mutants but completely inactive in ptsH mutants. Thus, specific phosphorylation events seem to control the localization of LicT.

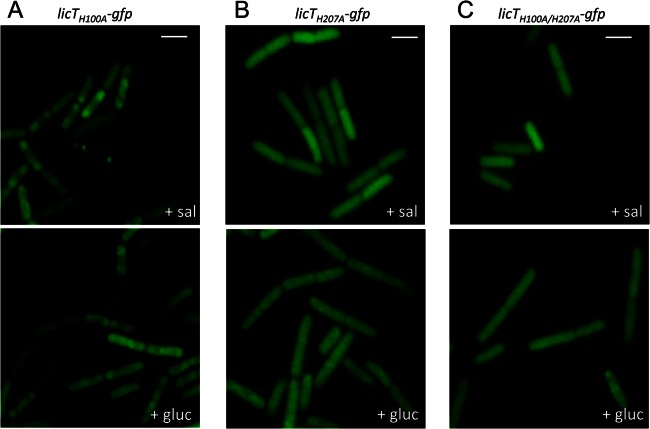

Impact of the different phosphorylation sites on LicT localization.

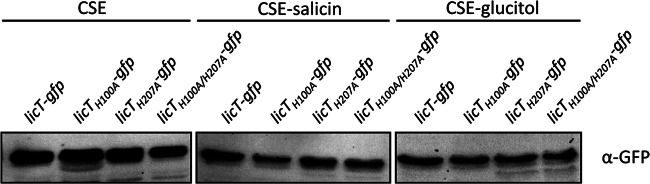

The conserved histidine residues in PRD1 and PRD2 are phosphorylated by BglP and HPr, respectively. To study the impact of these phosphorylation events in more detail, we constructed a set of strains that express LicT variants with mutations in His-100 (PRD1, H100A), His-207 (PRD2, H207A), or both residues. To exclude the possibility that the mutations affected the stability and thus the intracellular accumulation of the LicT-GFP fusion proteins, we cultivated the different strains in CSE minimal medium without an added carbohydrate or with salicin or glucitol. The amounts of LicT-GFP were analyzed by a Western blot using antibodies that recognize GFP. As shown in Fig. 6, the different LicT variants were expressed in each medium. Therefore, the mutations did not affect the stability of the mutant LicT-GFP fusion proteins.

Fig 6.

Accumulation of LicT mutant proteins. The B. subtilis strains GP1225 (licT-gfp; wild type), GP1258 (licT-H100A-gfp), GP1259 (licT-H207A-gfp), and GP1258 (licT-H100A/H2007A-gfp) were grown in CSE minimal medium, in CSE with salicin, or in CSE with glucitol at 37°C to the mid-log phase. The crude extract obtained from 0.1 OD unit at 600 nm of each culture was separated on a 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel. After electrophoresis and blotting onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, the GFP tag was detected using rabbit polyclonal antibodies.

For the determination of LicT localization, the bacteria were grown in CSE minimal medium supplemented with salicin or glucitol. For the constitutively active LicT-H100A protein (GP1258), we observed a subpolar localization pattern of LicT under both conditions (Fig. 7A). This result is in excellent agreement with the LicT localization in the bglP mutant, in which H-100 cannot be phosphorylated. The inactive Lic-H207A protein was found to be evenly distributed under both conditions (Fig. 7B). Similarly, the inactive LicT-H100A/H207A double mutant protein was evenly distributed both in the presence and absence of salicin (Fig. 7C).

Fig 7.

Effect of mutations in the phosphorylation sites on LicT localization. Shown are fluorescence microscopy images of B. subtilis expressing LicT-H100A-GFP (GP1258) (A), LicT-H207A-GFP (GP1259) (B), and LicT-H100A/H207A-GFP (GP1260) (C). The bacteria were grown in CSE minimal medium with salicin or glucitol and prepared for microscopy in the logarithmic phase of growth. Scale bars, 2 μm.

Taken together, our data support the idea that the phosphorylation of LicT is crucial for its localization: all mutant proteins that are no longer responsive to the presence of salicin in their activity do also exhibit an unregulated localization. Similarly, in the PTS mutants that result either in constitutive LicT activity or in its complete inactivity, no response of LicT localization to the nutrient supply was observed. However, while the inactive LicT mutant proteins were always found throughout the cytoplasm, a subpolar localization was observed for the LicT protein that was inactive due to the absence of HPr. This difference suggests not only that the phosphorylation events are required for the correct intracellular recruitment of LicT but also that the integrity of the protein is important (see Discussion).

DISCUSSION

In this work, we provide the first analysis of the intracellular localization of PTS components and of a PTS-controlled transcription factor in B. subtilis.

Our results demonstrate that the general PTS protein enzyme I is evenly distributed in the cytoplasm. This is in good agreement with the annotation of this protein as a soluble PTS protein. However, contradictory results have been reported for the localization of enzyme I in E. coli. Similar to our results, E. coli enzyme I was found to be distributed in the cytoplasm by Neumann et al. (22), whereas a spotty distribution was reported by Patel et al. (21). Finally, polar localization of enzyme I was observed by Lopian et al. (20). It is difficult to judge the reason for these obvious differences. One factor may be the overexpression of enzyme I and the use of different fluorescence tags. In this work, we expressed the fluorescence-tagged PTS proteins from their own promoter, thus avoiding any effect of artificial expression.

A study on the subcellular localization of the β-glucoside-specific antitermination protein BglG indicated that this protein is recruited to the membrane by its cognate permease and sensor, BglF, and that BglG is released into the cytoplasm if the inducer and substrate salicin becomes available (23). Our results suggest that the localization of LicT in B. subtilis does also depend on the functional β-glucoside permease BglP: when no substrate is available, and BglP phosphorylates LicT on the PRD1 and thereby inactivates the protein, LicT is homogeneously distributed throughout the cytoplasm. In contrast, lack of phosphorylation of PRD1 when salicin is available (phosphate flux from BglP to the substrate) or the bglP gene is deleted results in subpolar localization of LicT. It should be noted that no membrane association of LicT was detected under all conditions tested in this work. Thus, the localization pattern of LicT differs from that of its E. coli homolog BglG. However, both proteins relocalize upon addition of the inducer, and in both cases this relocalization is achieved after about 15 min (Fig. 3) (20). It is interesting that a very recent study on the B. subtilis PRD-type transcription factor MtlR revealed that this protein is recruited to the membrane by its cognate mannitol-specific EIIB domain of the mannitol permease MtlA. Moreover, this membrane association was found to be important for the activity of MtlR (27). Thus, PRD-type transcription factors seem generally to require specific localization patterns for their activity; however, the precise localization differs from one protein to the other.

The determinants of intracellular protein localization are only poorly understood. While transmembrane domains can easily be identified in a protein, it is not known which factors drive the differential localization of LicT in the presence or absence of the inducer salicin. For example, the peripheral membrane protein DivIVA binds primarily to sites that exhibit a negative membrane curvature (39, 40). In this case, it was suggested that DivIVA multimers bridge the curvature (40). Another factor that often determines the localization of proteins is recruitment by other proteins or macromolecules. In B. subtilis, this is best studied for the assembly of the spore coat, which depends on the initial ATP-driven polymerization of SpoIVA on the spore surface (41, 42). Similarly, protein-dependent recruitment was proposed for the inactive BglG and the active MtlR transcription factors. In the case of LicT, the localization determinants are unknown. Interestingly, LicT active in transcriptional antitermination localizes to the same regions of the cell as the ribosomes (43, 44). Given the coupling between transcription and translation in bacteria, it is tempting to speculate that the RNA molecules to which LicT binds recruit the protein to the subpolar regions of the cell. Surprisingly, our results indicate that differential LicT localization is observed even in a strain devoid of the bglPH and bglS RAT RNA regions (Fig. 4B). One might argue that LicT may bind other RAT sequences in the absence of its cognate targets. However, as shown previously, LicT is unable to bind any of the other RAT sequences present in B. subtilis (45). Thus, phosphorylation is likely to be the driving force for LicT (re)localization.

Our analyses with PTS mutants and LicT phosphorylation site mutants support the idea that the PTS-dependent phosphorylation of LicT controls its subcellular localization. Indeed, mutations affecting enzyme I or HPr resulted in the absence of phosphorylation of the PRD1 of LicT, and both mutations did also result in the prevention of the homogeneous distribution of LicT that is normally observed when LicT is phosphorylated on PRD1 in the absence of the inducer salicin. The loss of phosphorylation of both PRD1 and PRD2 gave contradicting results: while subpolar LicT localization was observed in the ptsH mutant lacking HPr, the nonphosphorylatable LicT-H100A/H207A protein was homogeneously distributed in the cytoplasm. Though counterintuitive, these observations are not unprecedented: phosphorylation-dependent protein localization or protein-protein interactions sometimes require not only the presence or absence of the phosphoryl group; the requirements for correct localization/interaction may extend to the correct amino acid sequence of the proteins. This was reported for the localization of E. coli HPr, which depends on the presence of the phosphorylation site (His-15) for proper polar localization (20). Similarly, the interaction between the B. subtilis HPr protein and the CcpA transcription factor depends on the integrity of the His-15 phosphorylation site (46, 47). Finally, the presence or absence of the phosphorylation site His-15 in HPr and its regulatory paralog Crh is a major determinant for the specificity of the regulatory interaction between Crh and the methylglyoxal synthase MgsA (48).

While the field of intracellular protein localization in bacteria is still in its infancy, it is becoming more and more obvious that proteins are very dynamic and that they relocalize depending on the growth conditions. The analysis of the driving forces and the molecular mechanisms behind this movement of proteins will be a major challenge for future research.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Vanessa Otten, Oliver Schilling, and Dominik Tödter for their help with some experiments and Sabine Lentes for technical assistance.

This work was supported by grants from the Federal Ministry of Education and Research SYSMO network (PtJ-BIO/0313978D) and the DFG (SFB860) to J.S. F.M.R. was supported by a fellowship from the German National Academic Foundation.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 8 March 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JB.00117-13.

REFERENCES

- 1. Deutscher J, Francke C, Postma PW. 2006. How phosphotransferase system-related protein phosphorylation regulates carbohydrate metabolism in bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 70:939–1031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Postma PW, Lengeler JW, Jacobson GR. 1993. Phosphoenol-pyruvate:carbohydrate phosphotransferase systems of bacteria. Microbiol. Rev. 57:543–594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Stülke J. 2002. Control of transcription termination in bacteria by RNA-binding proteins that modulate RNA structures. Arch. Microbiol. 177:433–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Stülke J, Arnaud M, Rapoport G, Martin-Verstraete I. 1998. PRD—a protein domain involved in PTS-dependent induction and carbon catabolite repression of catabolic operons in bacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 28:865–874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Joyet P, Bouraoui H, Aké FM, Derkaoui M, Zébré AC, Cao MT, Ventroux M, Nessler S, Noirot-Gros MF, Deutscher J, Milohanic E. Transcription regulators controlled by interaction with enzyme IIB components of the phosphoenolpyruvate:sugar phosphotransferase system. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, in press [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Aymerich S, Steinmetz M. 1992. Specificity determinants and structural features in the RNA target of the bacterial antiterminator proteins of the BglG/SacY family. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 89:10410–10414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schilling O, Herzberg C, Hertrich T, Vörsmann H, Jessen D, Hübner S, Titgemeyer F, Stülke J. 2006. Keeping signals straight in transcription regulation: specificity determinants for the interaction of a family of conserved bacterial RNA-protein couples. Nucleic Acids Res. 34:6102–6115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. van Tilbeurgh H, Declerck N. 2001. Structural insights into the regulation of bacterial signalling proteins containing PRDs. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 11:685–693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Le Coq D, Lindner C, Krüger S, Steinmetz M, Stülke J. 1995. New β-glucoside (bgl) genes in Bacillus subtilis: the bglP gene product has both transport and regulatory functions similar to those of BglF, its Escherichia coli homolog. J. Bacteriol. 177:1527–1535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Krüger S, Hecker H. 1995. Regulation of the putative bglPH operon for aryl-β-glucoside utilization in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 177:5590–5597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schnetz K, Stülke J, Gertz S, Krüger S, Krieg M, Hecker M, Rak B. 1996. LicT, a Bacillus subtilis transcriptional antiterminator protein of the BglG family. J. Bacteriol. 178:1971–1979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lindner C, Galinier A, Hecker M, Deutscher J. 1999. Regulation of the activity of the Bacillus subtilis antiterminator LicT by multiple PEP-dependent, enzyme I- and HPr-catalysed phosphorylation. Mol. Microbiol. 31:995–1006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tortosa P, Declerck N, Dutartre H, Lindner C, Deutscher J, Le Coq D. 2001. Sites of positive and negative regulation in the Bacillus subtilis antiterminators LicT and SacY. Mol. Microbiol. 41:1381–1393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Graille M, Zhou CZ, Receveur-Brechot V, Collinet B, Declerck N, van Tilbeurgh H. 2005. Activation of the LicT transcriptional antiterminator involves a domain swing/lock mechanism provoking massive structural changes. J. Biol. Chem. 280:14780–14789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. van Tilbeurgh H, Le Coq D, Declerck N. 2001. Crystal structure of an activated form of the PTS regulation domain from the LicT transcriptional antiterminator. EMBO J. 20:3789–3799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Arnaud M, Vary P, Zagorec M, Klier A, Débarbouillé M, Postma P, Rapoport G. 1992. Regulation of the sacPA operon of Bacillus subtilis: identification of phosphotransferase system components involved in SacT activity. J. Bacteriol. 174:3161–3170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schmalisch M, Bachem S, Stülke J. 2003. Control of the Bacillus subtilis antiterminator protein GlcT by phosphorylation: elucidation of the phosphorylation chain leading to inactivation of GlcT. J. Biol. Chem. 278:51108–51115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rothe FM, Bahr T, Stülke J, Rak B, Görke B. 2012. Activation of Escherichia coli antiterminator BglG requires its phosphorylation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109:15906–15911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nevo-Dinur K, Govindarajan S, Amster-Choder O. 2012. Subcellular localization of RNA and proteins in prokaryotes. Trends Genet. 28:314–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lopian L, Elisha Y, Nussbaum-Schochat A, Amster-Choder O. 2010. Spatial and temporal organization of the E. coli PTS components. EMBO J. 29:3630–3645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Patel HV, Vyas KA, Li X, Savtchenko R, Roseman S. 2004. Subcellular distribution of enzyme I of the Escherichia coli phosphoenolpyruvate:glycose phosphotransferase system depends on growth conditions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:17486–17491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Neumann S, Grosse K, Sourjik V. 2012. Chemotactic signaling via carbohydrate phsohotransferase systems in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109:12159–12164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lopian L, Nussbaum-Schochat A, O'Day-Kerstein K, Wright A, Amster-Choder O. 2003. The BglF sensor recruits the BglG transcription regulator to the membrane and releases it on stimulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:7099–7104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Raveh H, Lopian L, Nussbaum-Shochat A, Wright A, Amster-Choder O. 2009. Modulation of transcription antitermination in the bgl operon of Escherichia coli by the PTS. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:13523–13528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Richet E, Davidson AL, Joly N. 2012. The ABC transporter MalFGK(2) sequesters the MalT transcription factor at the membrane in the absence of cognate substrate. Mol. Microbiol. 85:632–647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nam TW, Jung HI, An YI, Park YH, Lee SH, Seok YJ, Cha SS. 2008. Analyses of Mlc-IIBGlc interaction and a plausible molecular mechanism of Mlc inactivation by membrane sequestration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:3751–3756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bouraoui H, Ventroux M, Noirot-Gros MF, Deutscher J, Joyet P. 2013. Membrane sequestration by the EIIB domain of the mannitol permease MtlA activates the Bacillus subtilis mtl operon regulator MtlR. Mol. Microbiol. 87:789–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 29. Commichau FM, Herzberg C, Tripal P, Valerius O, Stülke J. 2007. A regulatory protein-protein interaction governs glutamate biosynthesis in Bacillus subtilis: the glutamate dehydrogenase RocG moonlights in controlling the transcription factor GltC. Mol. Microbiol. 65:642–654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kunst F, Rapoport G. 1995. Salt stress is an environmental signal affecting degradative enzyme synthesis in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 177:2403–2407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lewis PJ, Marston AL. 1999. GFP vectors for controlled expression and dual labeling of protein fusions in Bacillus subtilis. Gene 227:101–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Veening JW, Smits WK, Hamoen LW, Jongbloed JD, Kuipers OP. 2004. Visualization of differential gene expression by improved cyan fluorescent protein and yellow fluorescent protein production in Bacillus subtilis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:6809–6815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Benson AK, Haldenwang WG. 1993. Regulation of sigma B levels and activity in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 175:2347–2356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bi W, Stambrook PJ. 1998. Site-directed mutagenesis by combined chain reaction. Anal. Biochem. 256:137–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wach A. 1996. PCR-synthesis of marker cassettes with long flanking homology regions for gene disruptions in S. cerevisiae. Yeast 12:259–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Stülke J, Martin-Verstraete I, Zagorec M, Rose M, Klier A, Rapoport G. 1997. Induction of the Bacillus subtilis ptsGHI operon by glucose is controlled by a novel antiterminator, GlcT. Mol. Microbiol. 25:65–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Krüger S, Gertz S, Hecker M. 1996. Transcriptional analysis of bglPH expression in Bacillus subtilis: evidence for two distinct pathways mediating carbon catabolite repression. J. Bacteriol. 178:2637–2644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Nicolas P, Mäder U, Dervyn E, Rochat T, Leduc A, Pigeonneau N, Bidnenko E, Marchadier E, Hoebeke M, Aymerich S, Becher D, Bisicchia P, Botella E, Delumeau O, Doherty G, Denham EL, Devine KM, Fogg M, Fromion V, Goelzer A, Hansen A, Härtig E, Harwood CR, Homuth G, Jarmer H, Jules M, Klipp E, Le Chat L, Lecointe F, Lewis P, Liebermeister W, March A, Mars RAT, Nannapaneni P, Noone D, Pohl S, Rinn B, Rügheimer F, Sappa PK, Samson F, Schaffer M, Schwikowski B, Steil L, Stülke J, Wiegert T, Wilkinson AJ, van Dijl JM, Hecker M, Völker U, Bessières P, Noirot P. 2012. The condition-dependent whole-transcriptome reveals high-level regulatory architecture in bacteria. Science 335:1103–1106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ramamurthi KS, Losick R. 2009. Negative membrane curvature as a cue for subcellular localization of a bacterial protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:13541–13545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lenarcic R, Halbedel S, Visser L, Shaw M, Wu LJ, Errington J, Marenduzzo D, Hamoen LW. 2009. Localisation of DivIVA by targeting to negatively curved membranes. EMBO J. 28:2272–2282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. McKenney PT, Eichenberger P. 2012. Dynamics of spore coat morphogenesis in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 83:245–260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Castaing JP, Nagy A, Anantharaman V, Aravind L, Ramamurthi KS. 2013. ATP hydrolysis by a domain related to translation factor GTPases drives polymerization of a static bacterial morphogenetic protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 110:E151–E160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lewis P, Thaker SD, Errington J. 2000. Compartmentalization of transcription and translation in Bacillus subtilis. EMBO J. 19:710–718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lehnik-Habrink M, Rempeters L, Kovács AT, Wrede C, Baierlein C, Krebber H, Kuipers OP, Stülke J. 2013. DEAD-box RNA helicases in Bacillus subtilis have multiple functions and act independently from each other. J. Bacteriol. 195:534–544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hübner S, Declerck N, Diethmaier C, Le Coq D, Aymerich S, Stülke J. 2011. Prevention of cross-talk in conserved regulatory systems: identification of specificity determinants in RNA-binding anti-termination proteins of the BglG family. Nucleic Acids Res. 39:4360–4372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Reizer J, Bergstedt U, Galinier A, Küster E, Saier MH, Hillen W, Steinmetz M, Deutscher J. 1996. Catabolite repression resistance of gnt operon expression in Bacillus subtilis conferred by mutation of His-15, the site of phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent phosphorylation of the phosphocarrier protein HPr. J. Bacteriol. 178:5480–5486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Schumacher MA, Allen GS, Diel M, Seidel G, Hillen W, Brennan RG. 2004. Structural basis for allosteric control of the transcription regulator CcpA by the phosphoproteins HPr-Ser46-P. Cell 118:731–741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Landmann JJ, Busse RA, Latz JH, Singh KD, Stülke J, Görke B. 2011. Crh, the paralogue of the phosphocarrier protein HPr, controls the methylglyoxal bypass of glycolysis in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 82:770–787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.