Abstract

Background:

The internet is a phenomena that changes human, specially the younger generation's, life in the 21st century. Online communication is a common way of interacting among adolescents who experience feelings of social anxiety. The aim of this study was to investigate the relationship between social anxiety and online communication in adolescents.

Methods:

Three hundred and thirty students aged 13-16 years were selected from eight middle and high schools in Isfahan by multistage cluster sampling. Each of them completed a survey on the amount of time they spent communicating online, the topics they discussed, the partners they engaged with and their purpose for communicating over the internet. They also completed the social anxiety scale of adolescents. Data were analyzed using Pearson correlation and multiple regression.

Results:

Results of the Pearson analysis showed that online communication has a significant positive relationship with apprehension and fear of negative evaluation (AFNE), and a significant negative relationship with tension and inhibition in social contact (TISC) (P < 0.01). The results of regression analysis showed that the best predictor of online communication is AFNE, TISC.

Conclusions:

It is suggested that students from middle school get assessed in terms of the level of social anxiety. Then, the quality and quantity of their online communication should be moderated through group training and consulting and referral to medical centers, if needed. The results of this study may lead to optimal use of online communications and reduce the personal, social and psychological problems of adolescents.

Keywords: Adolescents, internet, online communication, social anxiety

INTRODUCTION

The internet has developed a new way of interaction among individuals due to its inherent characteristics such as providing an easy and quick connection and accessibility from everywhere in the world. Social networks such as Facebook and Twitter have created modern methods of communication and social interaction for their users in terms of online communication. All of these social network users can easily share information with other users.

The internet has significantly changed the nature of communication in the 21st century. This is especially true for adolescents, members of the so-called “Net generation,” who have never known a world without the internet.[1] The advantages of internet communication are many, such as access to a wider network of people with similar interests or concerns and increased ability to stay in touch with geographically distant friends and family.[2]

Some individuals who have difficulty in formulating and maintaining friendships, such as individuals who report feelings of high social anxiety, may miss out peer interactions that are important for their positive adjustments. Individuals with social anxiety disorder describe their relationships with family, friends and romantic partners as “impaired.”[3–5] Social anxiety is characterized by a strong fear of humiliation and embarrassment during exposure to unfamiliar people or possible scrutiny by others. Socially anxious individuals often withdraw from either informal or formal situations because they are afraid of failing in socially evaluative tasks.[6] These adolescents also have to learn how to satisfy rising interpersonal needs for affection, belonging, approval and control through communication and interactions.

A motivation to form and/or maintain at least a minimum quantity of positive relationships is fundamental to the general development and health of adolescents.[7] Communicating online may be considered as such a safety behavior that allows those with social anxiety to communicate with others, while minimizing the potential threat and associated anxiety.[8] Online communication appears to reduce or regulate social anxiety in the short term,[9,10] but, in the long term, confidence to communicate with others beyond the online context may be undermined if successful online interactions are attributed to the unique aspects of the internet, such as anonymity, rather than personal attributes.[2,11,12] For socially anxious individuals, communicating with others on the internet in a text-based manner may allow them to avoid aspects of social situations they fear, while at the same time partially meet their needs for interpersonal contact and relationships.[2]

Researchers have speculated that the text-based nature of the internet and the lack of visual cues when communicating online allow those with social anxiety to conceal and, therefore, control aspects of their appearance that they perceive as leading to negative evaluation, such as sweating and stammering.[8] Prior research studies examined other factors that may make online relationship preferable for individuals with social anxiety, such as feelings of satisfaction and fulfillment, or achieving a sense of belonging.[13]

There are two main hypotheses about the relationship between social anxiety and online communication. The social compensation hypothesis suggests that adolescents with high levels of social anxiety may report more positive friendship quality if they use computers to interact with friends to a greater extent than their peers, who also have high social anxiety but do not use computers to have such interactions with friends.[14] Researchers have suggested that communicating with limited eye contact or audio visual cues may create a more comfortable social situation for socially anxious adolescents in comparison with traditional face-to-face interactions,[12] leading to the social compensation hypothesis. The anonymous nature of online interactions is thought to minimize the risks of social rejection and emotional vulnerability.[15–17]

In contrast, according to the rich-get-richer hypothesis, individuals who already are comfortable in social situations may use computers to seek out additional opportunities to socialize.[16]

Adolescents with high-quality friendships may also use online communication to expand their social network in a relatively easy way because they may have better social skills that can be used to connect to new friends online.[18]

METHODS

The statistical population of this study consisted of all male and female students aged 13-16 years in the year of 2012 in the city of Isfahan, Iran. Participants were 330 students: 166 girls (50.3%) and 164 boys (49.7%). They were recruited from eight middle and high schools by multistage cluster sampling. To be eligible to take part in this study, students had to have access to a computer and the internet at home, and use any application for online communication purposes. Completion of an anonymous questionnaire occurred at a convenient time during school hours. Surveys from students who indicated that they did not communicate online were not retained for analysis.

There were some limitations on conducting the research in state high schools related to the government regulations. Thus, the previously estimated size of the sample (384) was reduced to 330.

The following measures were used in this study: Online communication questionnaire (OCQ) Valkenburg and Peter[19] and social anxiety scale of adolescents (SASA) Puklek and Vidmar.[2]

The OCQ was translated to Persian and conducted in this study for the first time in Iran. It consists of the following parts:

Amount of online communication

Four items assessing the frequency (question 1) and duration (questions 2-4) of online communication were adapted from Valkenburg and Peter's[19] study. Question 1 asked the participants the number of days they had been online to chat in the past week; questions 2, 3, and 4 asked about the approximate total time spent chatting on the last day they were online, on an average weekday and on an average weekend, respectively. Response categories for question 1 ranged from 0, none, to 4, every day; response categories for questions 2, 3, and 4 ranged from 1, less than 15 min, to 5, more than 4 h.

Topics of online communication

A list of topics of online communication was constructed by combining 35 items that had been used in several studies.[21,22] Some additional items were added by Bonetti.[6] Participants were asked how often they chatted about each topic presented in Table 1; response categories ranged from 0, never, to 2, often.

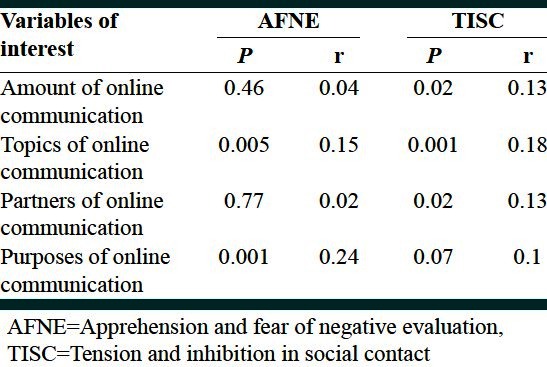

Table 1.

Correlation between online communication and social anxiety aspects

Partners of online communication

An eight-item list of partners of online communication was devised by Bonetti. Participants were asked how often they chatted with each partner presented in Table 2; response categories ranged from 0, never, to 2, often.

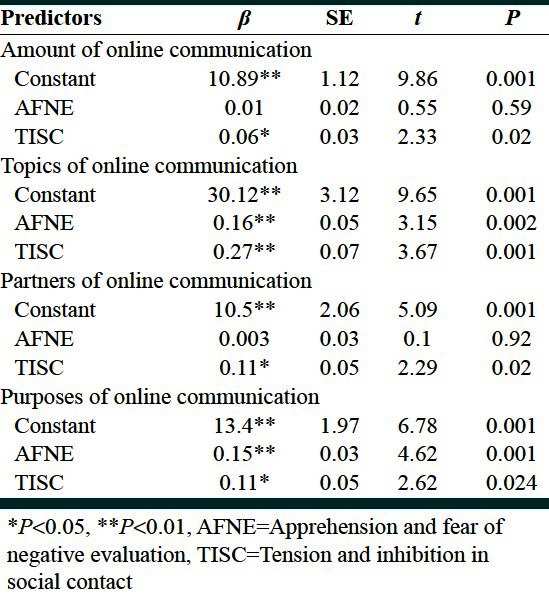

Table 2.

Multiple regression analysis for predicting online communication through social anxiety aspects

Purposes of online communication

The 18 purposes for communicating online developed by Peter et al.[23] were retained in a list. The authors included them in five motive scales that, in this study, yielded the following indices of internal consistency: Entertainment, maintaining relationships, social compensation, social inclusion and meeting people. Participants were asked how often they chatted for each purpose; response categories ranged from 0, never, to 2, often.

The second measure used in this study was the SASA, which was constructed by Puklek and Vidmar.[20] It consists of two subscales: Apprehension and fear of negative evaluation (AFNE), and tension and inhibition in social contact (TISC).

SASA measures adolescents’ anxious feelings, worries and behaviors in social evaluative situations. The majority of 28 test items were developed on the basis of answers in qualitative interviews that were carried out with 47 slovene adolescents of different ages in 1994. Adolescents were questioned about their real or imagined feelings and thoughts in various situations of possible social evaluation (e.g., meeting peers at parties, taking part in a classroom discussion, meeting lesser known peers, getting acquainted with the opposite sex and performing in front of an audience).

To measure the correlation in this study, 330 adolescents participated in this study and completed the questionnaire. The final results were analyzed with SPSS software 18 by using Pearson correlation and multiple regression.

RESULTS

There was a significant positive relationship between online communication and AFNE. Also, there was a significant negative relationship between online communication and TISC (P < 0.01). Amount of online communication has a significant negative relationship with TISC (P < 0.01). There was also a significant positive relationship between topics of online communication and AFNE and a negative significant relationship between topics of online communication and TISC. There was a significant negative relationship between partners of online communication and TISC. Finally, there was a positive significant relationship between purposes of online communication and AFNE [Table 1].

As shown in Table 2, apprehension and AFNE and TISC, with standard beta coefficients of –0.22 and 0.15, predict 6.9% of online communication variance. Also, TISC with standard beta coefficients of –0.13 predict 1.8% of amount of online communication variance. Apprehension and AFNE and TISC, with standard beta coefficients of 0.17 and –0.2, predict 6.2% of topics of online communication variance. TISC with standard beta coefficients of 0.13 predict 1.6% of partners of online communication variance. Finally, apprehension and AFNE and TISC, with standard beta coefficients of 0.25 and –0.12, predict 7.1% of purposes of online communication variance.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to investigate the relationship between social anxiety and online communication in adolescents. The results of the Pearson test about positive relationship of online communication and AFNE and negative relationship of online communication and TISC were consistent with study of Erwin et al.[2] indicating that internet users who have social anxiety in comparison with the clinical sample who do not use the internet have more AFNE, isolation and anxiety. It may be that a large number of adolescents tend to use online communication because of anxiety and fear of face to face social interaction. In fact, they are not able to establish a good relationship in the real world. In other words, adolescents who have a AFNE by others may tend to use internet relationships to overcome this fear. In fact, they find the virtual world a safe place to get rid of their concerns and fears of real interactions.

The next results of the Pearson test revealed a negative relationship between the amount of online communication and TISC. In fact, when adolescents have low TISC, they communicate more through the internet. In other words, if adolescents have high tension and problems in social contact, they will not have any interest in social interaction even through the internet.

Topics of online communication were found to have a significant positive relationship with AFNE and a significant negative relationship with TISC. These findings were consistent with the Bonetti et al.[6] study, which indicated that adolescents with high feelings of social anxiety and loneliness communicated online more frequently about personal things, people around them who have an influence on their everyday lives, intimate topics and about their present and past life, but not the future. The results revealed that when a person has high TISC, they tend to talk about different problems less through internet. They may not be well prepared for social interaction in different topics such as feelings and problems involving family.

The next finding showed that there is a significant negative relationship between partners of online communication and TISC. This result was consistent with the Bonetti et al. 2010[6] study, which indicated that boys who have social anxiety prefer to chat with adults they have met, but girls with social anxiety prefer to chat with girls or boys they have never met.

The last result of correlation showed a significant positive relationship between the purpose of online communication and AFNE. This converges with previous findings.[1,2,6,24] In fact, because of special anxiety due to changes of hormone levels in puberty, adolescents are not able to have their desired social interaction in the real world. Therefore, they fulfill their rational need to socially compensate in the safe environment of online communication.

The current study also found that the best predictor of online communication is high apprehension and low AFNE and TISCs. This is consistent with the Lee and Stapinski[8] study, which found social anxiety as a predicting factor in problematic internet use. The next predictor for amount of online communication is TISCs. Also, topics of online communication have two predictors: High apprehension and low AFNE and TISCs. Finally, the best predictor of online communication is high apprehension and low AFNE, and TISCs.

As mentioned above, the main result of this study is that the best predictor of online communication is positive apprehension and AFNE, negative TISCs. It means that when adolescents have high levels of AFNE and low levels of TISCs, they may tend to use online communication. In fact, due to the anxiety and AFNE by others, which is experienced by adolescents, they prefer such relationships that they are not worrying about being observed and assessed by others. Such peace of mind for adolescents is possible only through online communication. This is because they can hide their true identity and chat with unknown people without any anxiety for hours, and find ways to overcome their fears of social situations.

CONCLUSIONS

There was a major difference between the results of domestic and foreign research studies that may be due to cultural reasons. Most international studies suggest that online communication has a positive effect on mental health, such as reducing stress and negative feelings[24] and social anxiety,[25] but many domestic research studies have found negative relationships between mental health and the internet. It could be as a result of a different cultural context in Iran compared with other countries, especially western ones. Unlike many societies, our culture is not person oriented; therefore, social interaction is encouraged more than in western countries. Therefore, less people may isolate from the real life and tend to communicate through the internet. In fact, there are huge differences between Iranian virtual societies and their non-Iranian counterparts. The differences are related to culture, social and political situations. This lifestyle could have some serious impacts on people's relationships, such as weakening the social bonds, having written conversations rather than oral and face to face ones, inability to form emotional relationships in reality and, again, preference in establishing an emotional connection through writing, making subjective relations rather than real ones, easily ruins relationships made in this way and can result in extreme psychological damage.

Every study has some limitations and strengths, such that expression of these will be useful for future researches in the same field. The limitations of the current research are listed below:

This research was conducted on adolescents aged 13-16 years in middle and high school. Thus, the findings cannot be generalized to other age groups.

The measure tool of current research was self-report questionnaire that may cause participants not to answer honestly because of getting social approval.

Due to cultural and social limitations in educational environments, there was no possibility of a wider research.

Relationships reported in this study are correlation-based relationships. Therefore, they are not logical causality relations.

The most important strength of this research was preparation of an OCQ for the first time in Iran that could be used in future researches.

Because of the rapid growth of online communication, especially among adolescents, in Iran and lack of research in this area, results of this study may educate families and school staff and also could lead to optimal use from online communications and reduce the personal, social and psychological problems of adolescents.

Because of a high level of anxiety in adolescents, it is suggested that they learn proper and efficient use of the internet and online communication in schools. Also, parents should be aware of the benefits and problems of online communication. Because adolescents try to compensate the lack of having a good social relationship through online communication, it is also suggested that they should be taught communication skills by school psychologists from secondary school to reduce their levels of social anxiety.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jin-Liang W, Linda AJ, Da-Jun Z. The mediator role of self-disclosure and moderator roles of gender and social anxiety in the relationship between Chinese adolescents’ online communication. Comput Human Behav. 2011;27:2161–28. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Erwin BA, Turk CL, Heimberg RG, Fresco DM, Hantula DA. The Internet: Home to a severe population of individuals with social anxiety disorder? J Anxiety Disord. 2003;18:629–46. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2003.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schneier FR, Heckelman LR, Garfinkel R, Campeas R, Fallon BA, Gitow A, et al. MR. Functional impairment in social phobia. J Clin Psychiatry. 1994;55:322–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Turner SM, Beidel DC, Dancu CV, Keys DJ. Psychopathology of social phobia and comparison to avoidant personality disorder. J Abnorm Psychol. 1986;95:389–94. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.95.4.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whisman MA, Sheldon CT, Goering P. Psychiatric disorders and dissatisfaction with social relationships: Does type of relationship matter? J Abnorm Psychol. 2000;109:803–8. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.109.4.803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonetti L, Campbell MA, Gilmore L. The relationship of loneliness and social anxiety with children's and adolescents’ online communication. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2010;13:279–85. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2009.0215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baumeister RF, Leary MR. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol Bull. 1995;117:497–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee BW, Stapinski LA. Seeking safety on the internet: Relationship between social anxiety and problematic internet use. J Anxiety Disord. 2012;26:197–205. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campbell AJ, Cumming SR, Hughes I. Internet use by the socially fearful: Addiction or therapy? Cyberpsychol Behav. 2006;9:69–81. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2006.9.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shepherd RM, Edelmann RJ. Reasons for internet use and social anxiety. Pers Individ Dif. 2005;39:949–58. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clark DM, Wells A. A cognitive model of social phobia. In: Heimberg RG, Liebowitz MR, Hope DA, Schneier FR, editors. Social Phobia: Diagnosis, Assessment, and Treatment. New York, USA: Guilford Press; 1995. pp. 69–93. [Google Scholar]

- 12.McKenna KY, Green AS, Gleason ME. Relationship formation on the Internet: What's the big attraction? J Soc Issues. 2002;58:9–31. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sheeks MS, Birchmeier ZP. Shyness, sociability, and the use of computer-mediated communication in relationship development. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2007;10:64–70. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2006.9991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Desjarlais M, Willoughby T A. Longitudinal study of the relationship between adolescents boys’ and girls’ computer use with friends and friendship quality: Support for the social compensation or the rich-get-richer hypothesis. J Comput Human Behav. 2010;26:896–905. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amichai-Hamburger Y, Furnham A. The positive net. Comput Human Behav. 2007;23:1033–45. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gross EF, Juvonen J, Gable SL. Internet use and well-being in adolescence. J Soc Issues. 2002;58:75–90. [Google Scholar]

- 17.McKenna KY, Bargh JA. Plan 9 from Cyberspace: The implications of the internet for personality and social psychology. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2000;4:57–75. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anderson KJ. Internet use among college students: An exploratory study. J Am Coll Health. 2001;50:21–6. doi: 10.1080/07448480109595707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Valkenburg PM, Peter J. Preadolescents’ and adolescents’ online communication and their closeness to friends. Dev Psychol. 2007;43:267–77. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Puklek M, Vidmar G. Social anxiety in Slovene adolescence: Psychometric properties of a new measure, age differences and relations with self-consciousness and perceived incompetence. Eur Rev Appl Psychol. 2000;50:249–58. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lenhart A, Madden M, Hitlin P. Washington, DC: Pew Internet and American Life Project; 2005. [Last accessed on 2012 Aug 01]. Teens and technology: Youth are leading the transition to a fully wired and mobile nation; p. 44. Available from: http://www.pewinternet.org=*=media==Files=reports=2005=PIP_ Teens_Tech_July 2005 web.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lenhart A, Rainie L, Lewis O. Washington, DC: Pew Internet and American Life Project; 2001. [Last accessed 2012 Oct 10]. Teenage life online: The rise of the instant-message generation and the Internet's impact on friendships and family relationships; p. 45. Available from: http://www.pewinternet.org=*=media==Files=Reports=2001=PIP_Teens_Report.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peter J, Valkenburg PM, Schouten AP. Characteristics and motives of adolescents talking with strangers on the Inter-net. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2006;9:526–30. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2006.9.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morahan-Martin J, Schumacher P. Loneliness and social uses of the internet. Comput Human Behav. 2003;19:659–71. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ando R, Sakamoto A. The effect of cyber-friends on loneliness and social anxiety: Differences between high and low self-evaluated physical attractiveness groups. Comput Human Behav. 2008;24:993–1009. [Google Scholar]