Abstract

Hospital readmissions are common and costly; this has resulted in their emergence as a key target and quality indicator in the current era of renewed focus on cost containment. However, many concerns remain about the use of readmissions as a hospital quality indicator and about how to reduce hospital readmissions. These concerns stem in part from deficiencies in the state of the science of transitional care. A conceptualization of the “ideal” discharge process could help address these deficiencies and move the state of the science forward. We describe an ideal transition in care, explicate the key components, discuss its implications in the context of recent efforts to reduce readmissions, and suggest next steps for policymakers, researchers, health care administrators, practitioners, and educators.

Introduction

Containing the rise of health care costs has taken on a new sense of urgency in the wake of the recent economic recession and continued growth in the cost of healthcare. Accordingly, many stakeholders seek solutions to improve value (reducing costs while improving care),1 and hospital readmissions, which are common and costly,2 have emerged as a key target. Indeed, the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has instituted several programs intended to reduce readmissions, including funding for community-based care-transition programs, penalties for hospitals with elevated risk-adjusted readmission rates for selected diagnoses, Pioneer Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) with incentives to reduce global costs of care, and Hospital Engagement Networks (HENs) through the Partnership for Patients.3 A primary aim of these initiatives is to enhance the quality of care transitions as patients are discharged from the hospital.

Though the recent focus on hospital readmissions has appropriately drawn attention to transitions in care, some have expressed concerns. Among these are questions about 1) the extent to which readmissions truly reflect the quality of hospital care,4 2) the preventability of readmissions,5 3) limitations in risk-adjustment techniques,6 and 4) best practices for preventing readmissions.7 We believe these concerns stem in part from deficiencies in the state of the science of transitional care, and that future efforts in this area will be hindered without a clear vision of an ideal transition in care. We propose the key components of an ideal transition in care and discuss the implications of this concept as it pertains to hospital readmissions.

The Ideal Transition in Care

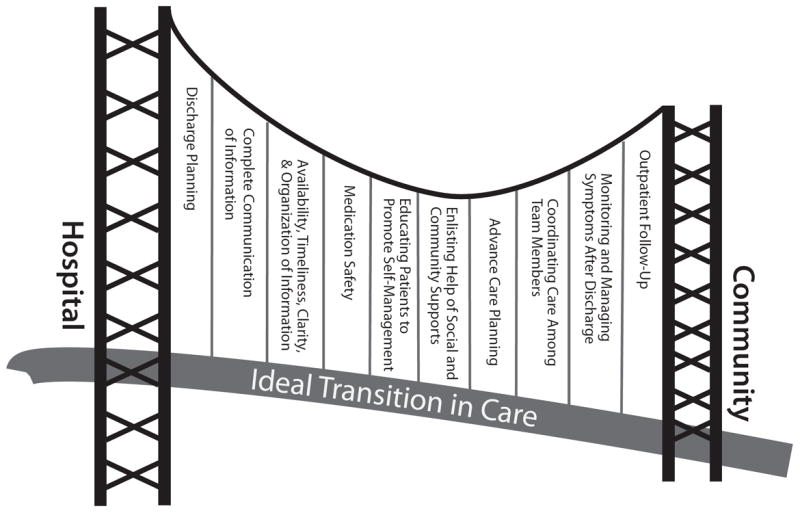

We propose the key components of an ideal transition in care in Figure 1 and Table 1. The Figure represents ten domains described more fully below as structural supports of the “bridge” patients must cross from one care environment to another during a care transition. This Figure highlights key domains and suggests that lack of a domain makes the bridge weaker and prone to gaps in care and poor outcomes. It also implies that the more components are missing, the less safe the “bridge” or transition is. Those domains that mainly take place prior to discharge are placed closer to the “hospital side” of the bridge, those that mainly take place after discharge are placed closer to the “community side” of the bridge, while those that take place both prior to and after discharge are in the middle. The Table provides descriptions of the key content for each of these domains, as well as guidance about which personnel might be involved and where in the transition process that domain should be implemented. We support these domains with supporting evidence where available.

FIG. 1.

Key components of an ideal transition in care; when rotated ninety degrees to the right the bridge patients must cross during a care transition is demonstrated.

Table 1.

Domains of an ideal transition in care

| Domain | Who | When | References |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Discharge Planning

| |||

|

Discharging clinician* | Pre-discharge | 9-11 |

| Care managers/discharge planners | |||

| Nurses | |||

|

| |||

|

Complete Communication of Information

| |||

Includes:

|

Discharging clinician | Time of discharge | 12-14 |

|

| |||

|

Availability, Timeliness, Clarity, and Organization of Information

| |||

|

Discharging clinician | Time of Discharge | 12-14 |

|

| |||

|

Medication Safety

| |||

|

Clinicians | Admission Throughout Hospitalization | 15-21 |

| Pharmacists | Time of Discharge | ||

| Nurses | |||

|

| |||

|

Educating Patients, Promoting Self-Management

| |||

|

Clinicians | Daily | 9-11,22-28, 30 |

| Nurses | Time of discharge | ||

| Care managers/discharge planners | Post-discharge | ||

| Transition Coaches | |||

|

| |||

|

Enlisting Help of Social and Community Supports

| |||

|

Clinicians | Pre-and Post-discharge | 29,30 |

| Nurses | |||

| Care managers | |||

| Home health staff | |||

|

| |||

|

Advance Care Planning

| |||

|

Clinicians | Pre-and post-discharge | 31, 32 |

| Palliative care staff | |||

| Social workers | |||

| Nurses | |||

| Hospice workers | |||

|

| |||

|

Coordinating Care Among Team Members

| |||

|

Clinicians | Pre-and post-discharge | 33 |

| Nurses | |||

| Office personnel | |||

| IT staff | |||

|

| |||

|

Monitoring and Managing Symptoms After Discharge

| |||

Monitor for:

|

Clinicians | Post-discharge | 11-13,28, 34-36 |

Via:

|

Nurses | ||

| Pharmacists | |||

| Care Managers | |||

| Visiting nurses and other home health staff | |||

|

| |||

|

Follow-up with Outpatient Providers

| |||

|

Clinicians | Post-discharge | 37-40 |

| Nurses | |||

| Pharmacists | |||

| Care Managers | |||

| Office personnel | |||

| Other clinical staff as appropriate | |||

”Clinician” refers to ordering providers including physicians, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners

Our concept of an ideal transition in care began with work by Naylor et al., who described several important components of a safe transition in care, including complete communication of information, patient education, enlisting the help of social and community supports, ensuring continuity of care, and coordinating care among team members.8 It is supplemented by the Transitions of Care Consensus Policy Statement proposed by representatives from hospital medicine, primary care, and emergency medicine, which emphasized aspects of timeliness and content of communication between providers.9 Our present articulation of these key components includes 10 organizing domains.

The Discharge Planning domain involves the important principle of planning ahead for hospital discharge while the patient is still being treated in the hospital, a paradigm espoused by Project RED10 and other successful care transitions interventions.11,12 Collaborating with the outpatient provider and taking the patient and caregiver’s preferences for appointment scheduling into account can help ensure optimal outpatient follow-up.

Complete Communication of Information refers to the content that should be included in discharge summaries and other means of information transfer from hospital to post-discharge care. The specific content areas are based on the Society of Hospital Medicine and Society of General Internal Medicine Continuity of Care Task Force systematic review and recommendations,13 which takes into account information requested by primary care physicians after discharge.

Availability, Timeliness, Clarity, and Organization of that information is as important as the content because post-discharge providers must be able to access and quickly understand the information they have been provided before assuming care of the patient.14,15

The Medication Safety domain is of central importance because medications are responsible for most post-discharge adverse events.16 Taking an accurate medication history,17 reconciling changes throughout the hospitalization,18 and communicating the reconciled medication regimen to patients and providers across transitions of care can reduce medication errors and improve patient safety.19-22

The Patient Education and Promotion of Self-Management domain involves teaching patients and their caregivers about the main hospital diagnoses and instructions for self-care, including medication changes, appointments, and whom to contact if issues arise. Confirming comprehension of instructions through assessments of acute (delirium) and chronic (dementia) cognitive impairments23-26 and teach-back from the patient (or caregiver) is an important aspect of such counseling, as is providing patients and caregivers with educational materials that are appropriate for their level of health literacy and preferred language.14 High-risk patients may benefit from “patient coaching” to improve their self-management skills.12 These recommendations are based on years of health literacy research,27-29 and such elements are generally included in effective interventions (including Project RED, 10 Naylor’s Transitional Care Model,11 and Coleman’s Care Transitions Intervention).12

Enlisting the help of Social and Community Supports is an important adjunct to medical care and is the rationale for the recent increase in CMS funding for community-based care-transition programs. These programs are crucial for assisting patients with household activities, meals, and other necessities during the period of recovery, though they should be distinguished from “care management” or “care coordination” interventions, which have not been found to be helpful in preventing readmissions unless “high touch” in nature.30,31

The Advance Care Planning domain may begin in the hospital or outpatient setting, and involves establishing goals of care and health care proxies, as well as engaging with palliative care or hospice services if appropriate. Emerging evidence supports the intuitive conclusion that this approach prevents readmissions, particularly in patients who do not benefit from hospital readmission.32,33

Attention to the Coordinating Care Among Team Members domain is needed to synchronize efforts across settings and providers. Clearly, many healthcare professionals as well as other involved parties can be involved in helping a single patient during transitions in care. It is vital that they coordinate information, assessments, and plans as a team.34

We recognize the domain of Monitoring and Managing Symptoms after Discharge as increasingly crucial as reflected in our growing understanding of the reasons for readmission, especially among patients with fragile conditions such as heart failure, chronic lung disease, gastrointestinal disorders, dementia,23-26 and vascular disease.35 Monitoring for new or worsening symptoms; medication side effects, discrepancies, or nonadherence; and other self-management challenges will allow problems to be detected and addressed early, before they result in unplanned healthcare utilization. It is noteworthy that successful interventions in this regard rely on in-home evaluation13,14,29 by nurses rather than telemonitoring, which in isolation has not been effective to date.36,37

Finally, optimal Outpatient Follow-Up with appropriate post-discharge providers is crucial for providing ideal transitions. These appointments need to be prompt38,39 (e.g. within 7 days if not sooner for high-risk patients) and with providers who have a longitudinal relationship to the patient, as prior work has shown increased readmissions when the provider is unfamiliar with the patient.40 The advantages and disadvantages of hospitalist-run post-discharge clinics as one way to increase access and expedite follow-up are currently being explored. Although the optimal content of a post-discharge visit has not been defined, logical tasks to be completed are myriad and imply the need for checklists, adequate time, and a multidisciplinary team of providers.41

Implications of the Ideal Transition in Care

Our conceptualization of an ideal transition in care provides insight for hospital and health-care system leadership, policymakers, researchers, clinicians, and educators seeking to improve transitions of care and reduce hospital readmissions. In the sections below, we briefly review commonly cited concerns about the recent focus on readmissions as a quality measure and illustrate how the Ideal Transition in Care addresses these concerns and propose fruitful areas for future work.

How does the framework address the extent to which readmissions reflect hospital quality?

One of the chief problems with readmission as a hospital quality measure is that many of the factors that influence readmission may not currently be under the hospital’s control. The healthcare environment to which a patient is being discharged (and was admitted from in the first place) is an important determinant of readmission.42 In this context, it is noteworthy that successful interventions to reduce readmission are generally those that focus on outpatient follow-up, while inpatient-only interventions have had less success.7 This is reflected in our framework above, informed by the literature, highlighting the importance of coordination between inpatient and outpatient providers and the importance of post-discharge care, including monitoring and managing symptoms after discharge, prompt follow-up appointments, the continuation of patient self-management activities, monitoring for drug-related problems after discharge, and the effective utilization of community supports. Accountable care organizations, once established, would be responsible for several components of this environment, including the provision of prompt and effective follow-up care.

The implication of the framework is that if a hospital does not have control over most of the factors that influence its readmission rate, it should see financial incentives to reduce readmission rates as an opportunity to invest in relationships with the outpatient environment from which their patients are admitted and to which they are discharged. One can envision hospitals growing ever-closer relationships with their network of primary care physician groups, community agencies and home health services, rehabilitation facilities and nursing homes through coordinated discharge planning, medication management, patient education, shared electronic medical records, structured handoffs in care, and systems of intensive outpatient monitoring. Our proposed framework, in other words, emphasizes that hospitals cannot reduce their readmission rates by focusing on aspects of care within their walls. They must forge new and stronger relationships with their communities if they are to be successful.

How does the framework help us understand which readmissions are preventable?

Public reporting and financial penalties are currently tied to all-cause readmission, but preventable readmissions are a more appealing outcome to target. In one study, the ranking of hospitals by all-cause readmission rate had very little correlation with the ranking by preventable readmission rate.5 However, researchers have struggled to establish standardized, valid, and reliable measures for determining what proportion of readmissions are in fact preventable, with estimates ranging from 5 to 79% in the published literature.43

The difficulty of accurately determining preventability stems from an inadequate understanding of the roles that patient comorbidities, transitional processes of care, individual patient behaviors, and social and environmental determinants of health play in the complex process of hospital recidivism. Our proposed elements of an ideal transition in care provide a structure to frame this discussion and suggest future research opportunities to allow a more accurate and reliable understanding of the spectrum of preventability. Care system leadership can use the framework to rigorously evaluate their readmissions and determine the extent to which the transitions process approached the ideal. For example, if a readmission occurs despite care processes that addressed most of the domains with high fidelity, it becomes much less likely that the readmission was preventable. It should be noted that the converse is not always true: when a transition falls well short of the ideal, it does not always imply that provision of a more ideal transition would necessarily have prevented the readmission, but it does make it more likely.

For educators, the framework may provide insights for trainees into the complexity of the transitions process and vulnerability of patients during this time, highlighting preventable aspects of readmissions that are within the grasp of the discharging clinician or team. It highlights the importance of medication reconciliation, synchronous communication, and pre-discharge teaching, which are measurable and teachable skills for non-physician providers, housestaff and medical students. It also may allow for more structured feedback, for example, on the quality of discharge summaries produced by trainees.

How could the framework improve risk adjustment for between-hospital comparisons?

Under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA), hospitals will be compared to one another using risk-standardized readmission rates as a way to penalize poorly-performing hospitals. However, risk-adjustment models have only modest ability to predict hospital readmission.6 Moreover, current approaches predominantly adjust for patients’ medical comorbidities (which are easily measurable), but they do not adequately take into account the growing literature on other factors that influence readmission rates, including a patient’s health literacy, visual or cognitive impairment, functional status, language barriers, and community-level factors such as social supports.44,45

The Ideal Transition of Care provides a comprehensive framework of hospital discharge quality that provides additional process measures on which hospitals could be compared rather than focusing solely on (inadequately) risk-adjusted readmission rates. Indeed, most other quality and safety measures (such as the National Quality Forum’s Safe Practices46 and The Joint Commission’s National Patient Safety Goals),47 emphasize process over outcome, in part because of issues of fairness. Process measures are less subject to differences in patient populations and also change the focus from simply reducing readmissions to improving transitional care more broadly. These process measures should be based on our framework and should attempt to capture as many dimensions of an optimal care transition as possible.

Possible examples of process measures include: the accuracy of medication reconciliation at admission and discharge;provision of prompt outpatient follow-up; provision of adequate systems to monitor and manage symptoms after discharge; advanced care planning in appropriate patients; and the quality of discharge education, incorporating measurements of the patient’s understanding and ability to self-manage their illness. At least some of these could be used now as part of a performance measurement set that highlights opportunities for immediate system change and can serve as performance milestones.

The framework could also be used to validate risk-adjustment techniques. After accounting for patient factors, the remaining variability in outcomes should be accounted for by processes of care that are in the transitions framework. Once these processes are accurately measured, one can determine if indeed the remaining variability is due to transitions processes, or rather unaccounted factors that are not being measured and that hospitals may have little control over. Such work can lead to iterative refinement of patient risk-adjustment models.

What does the framework imply about best practices for reducing readmission rates?

Despite the limitations of readmission rates as a quality measure noted above, hospitals presently face potentially large financial penalties for readmissions and are allocating resources to readmission reduction efforts. However, hospitals currently may not have enough guidance to know what actions to take to reduce readmissions, and thus could be spending money inefficiently and reducing the value proposition of focusing on readmissions.

A recent systematic review of interventions hospitals could employ to reduce readmissions identified several positive studies, but also many negative studies, and there were significant barriers to understanding what works to reduce readmissions.7 For example, most of the interventions described in both positive and negative studies were multifaceted, and the authors were unable to identify which components of the intervention were most effective. Also, while several studies have identified risk factors for readmission,6,48,49 very few studies have identified which subgroups of patients benefit most from specific interventions. Few of the studies described key contextual factors that may have led to successful or failed implementation, or the fidelity with which the intervention was implemented.50-52

Few if any of the studies were guided by a concept of the ideal transition in care.10 Such a framework will better guide development of multifaceted interventions and provide an improved means for interpreting the results. Clearly, rigorously-conducted, multi-center studies of readmission prevention interventions are needed to move the field forward. These studies should: 1) correlate implementation of specific intervention components with reductions in readmission rates to better understand the most effective components; 2) be adequately powered to show effect modification, i.e., which patients benefit most from these interventions; and 3) rigorously measure environmental context and intervention fidelity, and employ mixed methods to better understand predictors of implementation success and failure.

Our framework can be used in the design and evaluation of such interventions. For example, interventions could be designed that incorporate as many of the domains of an ideal transition as possible, in particular those that span the inpatient and outpatient settings. Processes of care metrics can be developed that measure the extent to which each domain is delivered, analogous to the way the Joint Commission might aggregate individual scores on the ten items in Acute Myocardial Infarction Core Measure Set53 to provide a composite of the quality of care provided to patients with this diagnosis. These can be used to correlate certain intervention components with success in reducing readmissions and also in measuring intervention fidelity.

Next Steps

For hospital and health care system leadership, who need to take action now to avoid financial penalties, we recommend starting with proven, “high-touch” interventions such as Project RED and the Care Transitions Intervention, which are durable, cost-effective, robustly address multiple domains of the Ideal Transition in Care, and have been implemented at numerous sites.54,55 Each hospital or group will need to decide on a bundle of interventions and customize them based on local workflow, resources, and culture.

Risk-stratification, to match the intensity of the intervention to the risk of readmission of the patient, will undoubtedly be a key component for the efficient use of resources. We anticipate future research will allow risk stratification to be a robust part of any implementation plan. However, as noted above, current risk prediction models are imperfect,6 and more work is needed to determine which patients benefit most from which interventions. Few if any studies have described interventions tailored to risk for this reason.

Based on our ideal transition in care, our collective experience, and published evidence,7,10-12 potential elements to start with include: early discharge planning; medication reconciliation;56 patient/caregiver education using health literacy principles, cognitive assessments, and teach-back to confirm understanding; synchronous communication (e.g., by phone) between inpatient and post-discharge providers; follow-up phone calls to patients within 72 hours of discharge; 24/7 availability of a responsible inpatient provider to address questions and problems (both from the patient/caregiver and from post-discharge providers); and prompt appointments for patients discharged home. High-risk patients will likely require additional interventions, including in-home assessments, disease-monitoring programs and/or patient coaching. Lastly, patients with certain conditions prone to readmission (such as heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) may benefit from disease-specific programs, including patient education, outpatient disease management, and monitoring protocols.

It is likely that the most effective interventions are those that come from combined, coordinated interventions shared between inpatient and outpatient settings and are intensive in nature. We expect that the more domains in the framework that are addressed, the safer and more seamless transitions in care will be, with improvement in patient outcomes. To the extent that fragmentation of care has been a barrier to the implementation of these types of interventions in the past, ACOs, perhaps with imbedded Patient-Centered Medical Homes, may be in the best position to take advantage of newly-aligned financial incentives to design comprehensive transitional care. Indeed, we anticipate the Figure may provide substrate for a discussion of post-discharge care and division of responsibilities between inpatient and outpatient care teams at the time of transition, so effort is not duplicated and multiple domains are addressed.

Other barriers to implementation of ideal transitions in care will continue to be an issue for most health care systems. Financial constraints that have been a barrier up until now will be partially overcome by penalties for high readmission rates and by ACOs, bundled payments, and alternative care contracts (i.e., global payments), but the extent to which each institution feels rewarded for investing in transitional interventions will vary greatly. Health care leadership that sees the value of improving transitions in care will be critical to overcoming this barrier. Competing demands (such as lowering hospital length of stay and carrying out other patient care responsibilities),57 lack of coordination and diffusion of responsibility among various clinical personnel, and lack of standards are other barriers58 that will require clear prioritization from leadership, policy changes, team-based care, provider education and feedback, and adequate allocation of personnel resources. In short, process redesign using continuous quality improvement efforts and effective tools will be required to maximize the possibility of success.

Conclusions

Readmissions are costly and undesirable. Intuition suggests they are a marker of poor care and that hospitals should be capable of reducing them, thereby improving care and decreasing costs. In a potential future world of ACOs based on global payments, financial incentives would be aligned for each system to reduce readmissions below their current baseline, therefore obviating the need for external financial rewards and penalties. In the meantime, financial penalties do exist, and controversy exists over their fairness and likelihood of driving appropriate behavior. To address these controversies and promote better transitional care, we call for the development and use of multi-faceted, collaborative transitions interventions that span settings, risk-adjustment models that allow for fairer comparisons among hospitals, better and more widespread measurement of processes of transitional care, a better understanding of what interventions are most effective and in whom, and better guidance in how to implement these interventions. Our conceptualization of an ideal transition of care serves as a guide and provides a common vocabulary for these efforts. Such research is likely to produce the knowledge needed for health care systems to improve transitions in care, reduce readmissions, and reduce costs.

Acknowledgments

Funding for Dr. Vasilevskis has been provided by the National Institutes of Health (K23AG040157) and the VA Tennessee Valley Geriatric Research, Education and Clinical Center (GRECC). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Aging, the National Institutes of Health, or the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

References

- 1.Porter ME, Teisberg EO. Redefining health care: creating value-based competition on results. Boston: Harvard Business School Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009 Apr 2;360(14):1418–1428. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0803563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) Public Law. 2010:111–148. http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-111publ148/pdf/PLAW-111publ148.pdf.

- 4.Axon RN, Williams MV. Hospital readmission as an accountability measure. JAMA. 2011 Feb 2;305(5):504–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Walraven C, Jennings A, Taljaard M, et al. Incidence of potentially avoidable urgent readmissions and their relation to all-cause urgent readmissions. CMAJ. 2011 Oct 4;183(14):E1067–1072. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.110400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kansagara D, Englander H, Salanitro A, et al. Risk prediction models for hospital readmission: a systematic review. JAMA. 2011 Oct 19;306(15):1688–1698. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hansen LO, Young RS, Hinami K, Leung A, Williams MV. Interventions to reduce 30-day rehospitalization: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011 Oct 18;155(8):520–528. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naylor MD. A decade of transitional care research with vulnerable elders. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2000 Apr;14(3):1–14. doi: 10.1097/00005082-200004000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Snow V, Beck D, Budnitz T, Miller DC, Potter J, Wears RL, Weiss KB, Williams MV American College of Physicians; Society of General Internal Medicine; Society of Hospital Medicine; American Geriatrics Society; American College of Emergency Physicians; Society of Academic Emergency Medicine. Transitions of Care Consensus Policy Statement American College of Physicians-Society of General Internal Medicine-Society of Hospital Medicine-American Geriatrics Society-American College of Emergency Physicians-Society of Academic Emergency Medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2009 Aug;24(8):971–6. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0969-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jack BW, Chetty VK, Anthony D, et al. A reengineered hospital discharge program to decrease rehospitalization: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009 Feb 3;150(3):178–187. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-3-200902030-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Naylor MD, Brooten D, Campbell R, et al. Comprehensive discharge planning and home follow-up of hospitalized elders: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 1999;281(7):613–620. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.7.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, Min SJ. The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006 Sep 25;166(17):1822–1828. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.17.1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, Williams MV, Basaviah P, Baker DW. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA. 2007 Feb 28;297(8):831–841. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.8.831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kripalani S, Jackson AT, Schnipper JL, Coleman EA. Promoting effective transitions of care at hospital discharge: a review of key issues for hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2007 Sep;2(5):314–23. doi: 10.1002/jhm.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gandara E, Ungar J, Lee J, Chan-Macrae M, O’Malley T, Schnipper JL. Discharge documentation of patients discharged to subacute facilities: a three-year quality improvement process across an integrated health care system. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2010 Jun;36(6):243–251. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(10)36039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(3):161–167. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-3-200302040-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tam VC, Knowles SR, Cornish PL, Fine N, Marchesano R, Etchells EE. Frequency, type and clinical importance of medication history errors at admission to hospital: a systematic review. CMAJ. 2005 Aug 30;173(5):510–515. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.045311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pippins JR, Gandhi TK, Hamann C, et al. Classifying and predicting errors of inpatient medication reconciliation. J Gen Intern Med. 2008 Sep;23(9):1414–1422. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0687-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kripalani S, Roumie CL, Schnipper JL, et al. for the PILL-CVD (Pharmacist Intervention for Low Literacy in Cardiovascular Disease) Study Group. Effect of a Pharmacist Intervention on Clinically Important Medication Errors After Hospital Discharge: A Randomized Trial. Ann Intern Med. 2012 Jul 3;157(1):1–10. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-1-201207030-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mueller SK, Sponsler KC, Kripalani S, Schnipper JL. Hospital-based medication reconciliation practices: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2012 Jul 23;172(14):1057–69. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.2246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schnipper JL, Hamann C, Ndumele CD, et al. Effect of an electronic medication reconciliation application and process redesign on potential adverse drug events: a cluster-randomized trial. Arch Intern Med. 2009 Apr 27;169(8):771–780. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schnipper JL, Kirwin JL, Cotugno MC, et al. Role of pharmacist counseling in preventing adverse drug events after hospitalization. Arch Intern Med. 2006 Mar 13;166(5):565–571. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.5.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu H, Covinsky KE, Stallard E, Thomas J, Sands LP. Insufficient Help for Activity of Daily Living Disabilities and Risk of All-Cause Hospitalization. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2012;60(5):927–933. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03926.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Callahan CM, Arling G, Tu W, et al. Transitions in Care for Older Adults with and without Dementia. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2012;60(5):813–820. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03905.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Phelan EA, Borson S, Grothaus L, Balch S, Larson EB. Association of Incident Dementia With Hospitalizations. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2012;307(2):165–172. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walsh EG, Wiener JM, Haber S, et al. Potentially Avoidable Hospitalizations of Dually Eligible Medicare and Medicaid Beneficiaries from Nursing Facility and Home- and Community-Based Services Waiver Programs. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2012;60(5):821–829. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kripalani S, Weiss BD. Teaching about health literacy and clear communication. J Gen Intern Med. 2006 Aug;21(8):888–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00543.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peterson PN, Shetterly SM, Clarke CL, Bekelman DB, Chan PS, Allen LA, Matlock DD, Magid DJ, Masoudi FA. Health literacy and outcomes among patients with heart failure. JAMA. 2011 Apr 27;305(16):1695–701. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cain CH, Neuwirth E, Bellows J, Zuber C, Green J. Patient experiences of transitioning from hospital to home: an ethnographic quality improvement project. J Hosp Med. 2012 May-Jun;7(5):382–7. doi: 10.1002/jhm.1918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peikes D, Chen A, Schore J, Brown R. Effects of care coordination on hospitalization, quality of care, and health care expenditures among Medicare beneficiaries: 15 randomized trials. JAMA. 2009 Feb 11;301(6):603–18. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peikes D, Peterson G, Brown RS, Graff S, Lynch JP. How changes in Washington University’s Medicare coordinated care demonstration pilot ultimately achieved savings. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012 Jun;31(6):1216–26. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pace A, Di Lorenzo C, Capon A, Villani V, Benincasa D, Guariglia L, Salvati M, Brogna C, Mantini V, Mastromattei A, Pompili A. Quality of care and rehospitalization rate in the last stage of disease in brain tumor patients assisted at home: a cost effectiveness study. J Palliat Med. 2012 Feb;15(2):225–7. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2011.0306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nelson C, Chand P, Sortais J, Oloimooja J, Rembert G. Inpatient palliative care consults and the probability of hospital readmission. Perm J. 2011 Spring;15(2):48–51. doi: 10.7812/tpp/10-142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.King HB, Battles J, Baker DP, Alonso A, Salas E, Webster J, Toomey L, Salisbury M. TeamSTEPPS™: Team Strategies and Tools to Enhance Performance and Patient Safety. In: Henriksen K, Battles JB, Keyes MA, Grady ML, editors. Advances in Patient Safety: New Directions and Alternative Approaches (Performance and Tools) Vol. 3. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2008. Aug, [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Feigenbaum P, Neuwirth E, Trowbridge L, et al. Factors contributing to all-cause 30-day readmissions: a structured case series across 18 hospitals. Med Care. 2012 Jul;50(7):599–605. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318249ce72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chaudhry SI, Mattera JA, Curtis JP, Spertus JA, Herrin J, Lin Z, Phillips CO, Hodshon BV, Cooper LS, Krumholz HM. Telemonitoring in patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2010 Dec 9;363(24):2301–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1010029. Epub 2010 Nov 16. Erratum in: N Engl J Med. 2011 Feb 3;364(5):490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takahashi PY, Pecina JL, Upatising B, Chaudhry R, Shah ND, Van Houten H, Cha S, Croghan I, Naessens JM, Hanson GJ. A Randomized Controlled Trial of Telemonitoring in Older Adults With Multiple Health Issues to Prevent Hospitalizations and Emergency Department Visits. Arch Intern Med. 2012 Apr 16; doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hernandez AF, Greiner MA, Fonarow GC, et al. Relationship between early physician follow-up and 30-day readmission among Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized for heart failure. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2010 May 5;303(17):1716–1722. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Misky GJ, Wald HL, Coleman EA. Post-hospitalization transitions: Examining the effects of timing of primary care provider follow-up. J Hosp Med. 2010 Sep;5(7):392–7. doi: 10.1002/jhm.666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weinberger M, Oddone EZ, Henderson WG. Does increased access to primary care reduce hospital readmissions? Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group on Primary Care and Hospital Readmission. N Engl J Med. 1996 May 30;334(22):1441–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199605303342206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Coleman EA. California Healthcare Foundation; Oct, 2010. The Post-Hospital Follow-Up Visit: A Physician Checklist to Reduce Readmissions. Accessed at: http://www.chcf.org/publications/2010/10/the-post-hospital-follow-up-visit-a-physician-checklist. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Joynt KE, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Thirty-day readmission rates for Medicare beneficiaries by race and site of care. JAMA. 2011 Feb 16;305(7):675–81. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van Walraven C, Bennett C, Jennings A, Austin PC, Forster AJ. Proportion of hospital readmissions deemed avoidable: a systematic review. CMAJ. 2011 Apr 19;183(7):E391–402. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.101860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arbaje AI, Wolff JL, Yu Q, et al. Postdischarge environmental and socioeconomic factors and the likelihood of early hospital readmission among community-dwelling Medicare beneficiaries. Gerontologist. 2008 Aug;48(4):495–504. doi: 10.1093/geront/48.4.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, Halpern DJ, Crotty K. Low health literacy and health outcomes: an updated systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011 Jul 19;155(2):97–107. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-2-201107190-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.National Quality Forum. Safe Practices for Better Healthcare–2010 Update: A Consensus Report. Washington, D.C.: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. Accreditation Program: Hospital 2010 National Patient Safety Goals. 2010 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hasan O, Meltzer DO, Shaykevich SA, Bell CM, Kaboli PJ, Auerbach AD, Wetterneck TB, Arora VM, Zhang J, Schnipper JL. Hospital readmission in general medicine patients: a prediction model. J Gen Intern Med. 2010 Mar;25(3):211–9. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1196-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.van Walraven C, Dhalla IA, Bell C, et al. Derivation and validation of an index to predict early death or unplanned readmission after discharge from hospital to the community. CMAJ. 2010 Apr 6;182(6):551–7. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.091117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brown C, Lilford R. Evaluating service delivery interventions to enhance patient safety. BMJ. 2008;337:a2764. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a2764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shekelle PG, Pronovost PJ, Wachter RM. Assessing the Evidence for Context-Sensitive Effectiveness and Safety of Patient Safety Practices: Developing Criteria. Rockville MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Dec, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shekelle PG, Pronovost PJ, Wachter RM, et al. Advancing the science of patient safety. Ann Intern Med. 2011 May 17;154(10):693–696. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-10-201105170-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Acute Myocardial Infarction Core Measure Set. Oakbrook Terrace IL: Aug 20, 2012. The Joint Commission. Accessed at: http://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/6/Acute%20Myocardial%20Infarction.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Voss R, Gardner R, Baier R, Butterfield K, Lehrman S, Gravenstein S. The care transitions intervention: translating from efficacy to effectiveness. Arch Intern Med. 2011 Jul 25;171(14):1232–7. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Project RED toolkit AHRQ Innovations Exchange. accessed at: http://www.innovations.ahrq.gov/content.aspx?id=2180.

- 56.Gillespie U, Alassaad A, Henrohn D, Garmo H, Hammarlund-Udenaes M, Toss H, Kettis-Lindblad A, Melhus H, Mörlin C. A comprehensive pharmacist intervention to reduce morbidity in patients 80 years or older: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2009 May 11;169(9):894–900. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Joynt KE, Jha AK. Thirty-day readmissions--truth and consequences. N Engl J Med. 2012 Apr 12;366(15):1366–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1201598. Epub 2012 Mar 28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Greysen SR, Schiliro D, Horwitz LI, Curry L, Bradley EH. “Out of sight, out of mind”: housestaff perceptions of quality-limiting factors in discharge care at teaching hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2012 May-Jun;7(5):376–81. doi: 10.1002/jhm.1928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]