Abstract

Diet-induced obesity (DIO) has been shown to alter the biophysical properties and pharmacological responsiveness of vagal afferent neurones and fibres, although the effects of DIO on central vagal neurones or vagal efferent functions have never been investigated. The aims of this study were to investigate whether high-fat diet-induced DIO also affects the properties of vagal efferent motoneurones, and to investigate whether these effects were reversed following weight loss induced by Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) surgery. Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were made from rat dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus (DMV) neurones in thin brainstem slices. The DMV neurones from rats exposed to high-fat diet for 12–14 weeks were less excitable, with a decreased membrane input resistance and decreased ability to fire action potentials in response to direct current pulse injection. The DMV neurones were also less responsive to superfusion with the satiety neuropeptides cholecystokinin and glucagon-like peptide 1. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass reversed all of these DIO-induced effects. Diet-induced obesity also affected the morphological properties of DMV neurones, increasing their size and dendritic arborization; RYGB did not reverse these morphological alterations. Remarkably, independent of diet, RYGB also reversed age-related changes of membrane properties and occurrence of charybdotoxin-sensitive (BK) calcium-dependent potassium current. These results demonstrate that DIO also affects the properties of central autonomic neurones by decreasing the membrane excitability and pharmacological responsiveness of central vagal motoneurones and that these changes were reversed following RYGB. In contrast, DIO-induced changes in morphological properties of DMV neurones were not reversed following gastric bypass surgery, suggesting that they may be due to diet, rather than obesity. These findings represent the first direct evidence for the plausible effect of RYGB to improve vagal neuronal health in the brain by reversing some effects of chronic high-fat diet as well as ageing. Vagovagal neurocircuits appear to remain open to modulation and adaptation throughout life, and understanding of these mechanisms may help in development of novel interventions to alleviate environmental (e.g. dietary) ailments and also alter neuronal ageing.

Key points

Diet-induced obesity (DIO) is known to alter the biophysical and pharmacological properties of gastrointestinal vagal afferent (sensory) neurones and fibres.

Little information is available, however, regarding the effects of DIO on the properties of central neurones involved in vagally mediated visceral reflexes.

The present study was designed to test the hypothesis that DIO alters the biophysical, pharmacological and morphological properties of vagal efferent motoneurones and that these alterations would be reversed following weight loss induced by Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.

Our data indicate that DIO decreases the excitability of vagal efferent neurones and attenuates their responses to the satiety neurohormones cholecystokinin and glucagon-like peptide 1. These DIO-induced changes were reversed following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, suggesting that the alterations were due to obesity, rather than diet. These findings represent the first direct evidence that Roux-en-Y gastric bypass improves the functioning and responsiveness of central vagal neurocircuits by reversing some of the effects induced by DIO.

Introduction

Gastric bypass surgery is the most effective treatment for morbid obesity and related conditions, with Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) being the most commonly performed procedure. Surgical stapling of the stomach creates a small gastric pouch, which is then joined to the mid-jejunum, bypassing the distal stomach and proximal small intestine. While mechanically restricting the size of the stomach certainly contributes to altered satiation and food intake, recent studies have also demonstrated that changes in the secretion and action of gastrointestinal (GI) neuroendocrine functions, including neurohormone secretion, may also play prominent roles in decreasing appetite and causing satiety (Ochner et al. 2010; Berthoud et al. 2011).

Vagally mediated reflexes are critical to the control, regulation and organization of appropriate GI functions, including satiety. Visceral sensory information from the GI tract is relayed to the CNS via the afferent vagus nerve, the central terminals of which enter the brainstem via the tractus solitarius and synapse on neurones of the nucleus of the tractus solitarius (NTS), using glutamate as a neurotransmitter (Andresen & Yang, 1990; Alywin et al. 1997; Travagli et al. 2006). The NTS neurones display heterogeneous biophysical, pharmacological and neurochemical properties and combine this vast volume of sensory information with hormonal and metabolic signals and neural inputs from other brainstem and higher CNS centres involved in autonomic homeostasis. The NTS relays these assimilated neural signals to other higher CNS centres involved in longer term homeostatic control of food intake, including the hypothalamus, the amygdala and the nucleus accumbens (Loewy, 1991; Schwartz et al. 2000; Rinaman, 2004; Berthoud & Morrison, 2008). The integrated output response from the NTS is also relayed to the adjacent dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus (DMV), which contains the preganglionic parasympathetic motoneurones that supply the vagal motor output to the GI tract via the efferent vagus nerve (Travagli et al. 2006).

Gastrointestinal inputs via the afferent vagus are thought to be involved principally in short-term satiation; GI neurohormones, such as cholecystokinin (CCK) and glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1), released from enteroendocrine cells within the intestine following ingestion of food, activate vagal afferent nerve endings in a predominantly paracrine fashion (Raybould & Tache, 1988; Holzer et al. 1994; Owyang, 1996; Raybould, 1998, 2007; Takahashi & Owyang, 1999; Li et al. 2001) to induce gastric relaxation, motility changes and pancreatic exocrine secretion, to name but a few of the visceral effects. Actions of GI neurohormones may not be restricted to vagal afferents, however; the dorsal vagal complex (i.e. NTS, DMV and area postrema) are essentially circumventricular organs, and circulating neurohormones such as CCK and GLP-1 may act directly at the level of the brainstem to modulate vagal afferent and efferent activity in addition to their potential actions as neurotransmitters within these neurocircuits (Branchereau et al. 1993; Blevins et al. 2000; Appleyard et al. 2005; van de Wall et al. 2005; Zheng et al. 2005; Baptista et al. 2007; Sullivan et al. 2007; Wan et al. 2007a; Holmes et al. 2009).

Several studies have demonstrated that the behaviour, activity and responsiveness of vagal afferents are altered by diet and obesity. The ability of CCK to activate vagal afferents is attenuated in rodents with diet-induced obesity (DIO; Covasa et al. 2000a,b; Donovan et al. 2007) and obese humans (Little et al. 2007), while a high-fat diet (HFD) alters receptor profiles on vagal afferent neurones (Paulino et al. 2009). Very little attention has been focused, however, on the effects of either diet or obesity on the membrane properties and responsiveness of central neurones, although electrophysiological studies have demonstrated that hypothalamic neurones in obese Zucker rats have a decreased responsiveness to neuropeptide Y (Pronchuk & Colmers, 2004) and leptin (Spanswick et al. 1997). Likewise, little consideration has been given to the effects that diet or obesity may exert upon the properties of brainstem neurones, and even less is known about the effects of metabolic/bariatric surgeries on these neurones. The aim of the present study, therefore, was to use electrophysiological techniques to determine the effects of HFD-induced obesity on the biophysical, morphological and pharmacological properties of vagal efferent neurones, and whether the effects of diet or obesity were reversed following RYGB-induced weight loss. Preliminary data were presented at the Experimental Biology meeting in 2012 (Browning & Hajnal, 2012a,b).

Methods

Animals

All experiments were carried out under protocols approved by the Penn State University College of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. A total of 84 male Sprague–Dawley rats were used in the present study. Eleven of these rats were used at 4–6 weeks of age and had unrestricted access to normal chow (control diet, CD; 13.5% kcal from fat; Purina Mills, Gray Summit, MO, USA and Research Diets, Inc., New Brunswick, NJ, USA) throughout (juvenile-CD rats). Of the remaining 73 rats, 19 had unrestricted access to control diet until use at 16–20 weeks of age (CD rats). The remaining 54 rats were placed on a high-fat diet (HFD; 60% kcal from fat; D12491; Research Diets, Inc., NJ, USA) for the remainder of the study. At 16 weeks of age, i.e. after 12 weeks on HFD, these 54 rats were divided into three groups, as follows: 17 rats underwent RYGB surgery (HFD-RYGB rats); seven rats underwent ‘sham’ surgery (HFD-sham rats); and 30 rats were maintained on HFD but did not undergo any surgical interventions (HFD rats). Thus, unless stated otherwise (i.e. juvenile-CD rats), all rats used in this study (CD, HFD and HFD-RYGB) were obtained from age-matched groups and used at 16–20 weeks of age.

In order to demonstrate the presence of obesity, 1H NMR body composition analysis was performed (Bruker LF90 proton-NMR Minispec; Brucker Optics, Woodlands, TX, USA) on five CD rats, eight HFD-RYGB rats and 23 HFD rats no more than 2 days before electrophysiological recording.

Surgical preparation

The RYGB (n= 17) and sham (n= 7) operations were carried out on rats at 16 weeks of age after 12 weeks exposure to HFD, as described previously (Thanos et al. 2012). Briefly, rats were fasted overnight but allowed water ad libitum prior to the surgery. Anaesthetised rats (isofluorane: 3% for induction and 1.5% for maintenance) were maintained in sterile conditions and were pretreated with a prophylactic antibiotic (ceftriaxone, 100 mg kg−1, i.m.; Roche, Nutley, NJ, USA). An abdominal incision was made in the mid-line and, in the RYGB procedures, the stomach was divided to create a smaller gastric pouch separated from the larger part of the stomach using a linear-cutting stapler (ETS-Flex Ethicon Endo surgery, 45mm; Ethicon Endo-Surgery Inc., Cincinnati, OH, USA). Measuring 15 cm from the ligament of Trietz, the small intestine was sharply divided. The distal segment was brought up and anastomosed in an end-to-size fashion to an opening in the small gastric pouch. The proximal bowel segment was anastomosed in an end-to-side fashion 15 cm along the distal limb. These connections were performed using interrupted 5–0 polypropylene sutures, and the abdominal wall and skin were closed using 3–0 silk and 5–0 nylon. The sham-operated control animals received manipulation of the stomach as if a stapler were to be inserted, and the stomach was then replaced into its normal anatomical location. Sham-operated control animals also received a transverse enterotomy 15 cm from the ligament of Treitz; this was simply reclosed with interrupted 5–0 polypropylene sutures. All surgical incisions were treated with local anaesthetic (0.5 ml of 0.25% bupivacaine s.c.), to minimize postoperative pain. Further postoperative care included treatment with normal saline (50 ml kg−1 s.c., immediately prior to surgery and after surgery, and on postoperative day 1) and buprenorphine (0.5 mg kg−1, i.m.) as needed for pain. Animals were given 24 h for the anastomoses to heal before being allowed to eat or drink, at which point animals were maintained on a liquid diet consisting of BOOST® (Nestle Nutrition, Minneapolis, MN, USA) and ad libitum water for 3 days. On postoperative day 3, the animals were returned to their high-fat diet.

Electrophysiological recordings

Between 13 and 19 days after surgery (mean 16.5 ± 0.6 days), brainstem slices were prepared for electrophysiological recordings as described previously (Browning et al. 1999). Briefly, rats were Anaesthetised with isoflurane before being killed by administration of a bilateral pneumothorax. The brainstem was removed and placed in ice-cold, oxygenated Krebs' solution before using a vibratome to cut four to six coronal slices (300 μm thick) spanning the entire rostrocaudal extent of the dorsal vagal complex. Slices were incubated in oxygenated Krebs' solution at 35 ± 1°C for at least 90 min prior to use. A single brainstem slice was then transferred to a custom-made perfusion chamber (volume 0.5 ml) on the stage of a Nikon E600FN microscope. The slice was held in place with a nylon mesh while being perfused continuously with warmed, oxygenated Krebs' solution, maintained at 32 ± 1°C. The DMV neurones were identified by their size and location, i.e. larger neurones ventral to the smaller neurones of the nucleus of the tractus solitarius but dorsal to the darker, heavily myelinated neurones of the hypoglossal nucleus. Electrophysiological recordings were made from neurones located in the medial DMV, which has been demonstrated previously to contain gastric-projecting neurones (Travagli et al. 2006), using difference interference contrast optics under brightfield illumination at a final magnification of ×400.

Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were made using micropipettes filled with potassium gluconate (resistance 2–4 MΩ; see ‘Drugs and solutions’ below for composition) and a single-electrode voltage-clamp amplifier (Axoclamp 1D; Molecular Devices, Union City, CA, USA). Data were filtered at 2 kHz, digitized via a Digidata 1320 interface, and analysed using pClamp9 software (Molecular Devices). Recordings were discarded if the series resistance was >20 MΩ.

Neuronal properties

Basic membrane properties

To calculate the membrane input resistance (Rin), the instantaneous current displacement was measured after the membrane was stepped from −50 to −60 mV.

Action potential characteristics

The DMV neurones were current clamped at approximately −60 mV before injection of depolarizing current pulses (15–30 ms duration) of intensity sufficient to evoke the firing of a single action potential at the current pulse offset. The action potential duration at threshold was measured, as was the amplitude of the after-hyperpolarization. The duration of the after-hyperpolarization (decay constant, τ) was measured after being fitted to a single-exponential equation.

To measure the frequency with which DMV neurones fire action potentials, depolarizing current pulses (400 ms duration) of increasing intensity (from 30 to 270 pA) were injected into neurones current clamped at approximately −60 mV. The number of action potentials fired during the depolarizing current pulses were counted and expressed as pulses per second.

Voltage-dependent potassium currents

Voltage-dependent potassium currents in DMV neurones were measured in the presence of TTX (1 μm) to eliminate voltage-dependent sodium currents. The inactivation curve of the fast transient outward potassium current, IA, was evoked in DMV neurones voltage clamped at −50 mV, by passing hyperpolarizing current steps (400 ms duration) in 10 mV increments to −120 mV before repolarization to −50 mV. The resultant current values were normalized (Imax= 100), averaged and plotted (see Fig. 2A).

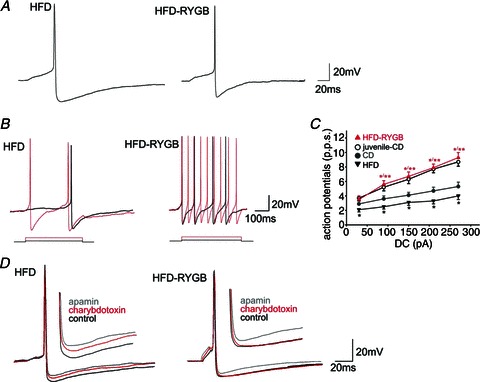

Figure 2. Gastic bypass surgery increases the action potential firing of neurones in the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus (DMV).

A, representative traces illustrating the effects of HFD and RYGB on action potential properties. The DMV neurones were current clamped at −60 mV prior to injection of a short (15 ms) depolarizing current pulse sufficient to evoke the firing of a single action potential at current pulse offset. Note that the amplitude and duration of the action potential after-hyperpolarization was decreased significantly following RYGB. B, HFD and HFD-RYGB neurones were current clamped at −60 mV prior to injection of long (400 ms) depolarizing current pulses of increasing magnitude (from 30 to 270 pA). Note that, following RYGB, DMV neurones fired a greater number of action potentials. C, graphical representation of the frequency of action potential firing (expressed as pulses per second, p.p.s.) in DMV neurones from juvenile-CD, CD, HFD and HFD-RYGB rats. Note that, at all frequencies of current injection, CD DMV neurones were less excitable and fired fewer action potentials than juvenile-CD DMV neurones. The HFD further decreased DMV neurone excitability at all frequencies of current injection. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass reversed the effects of ageing and diet-induced obesity on DMV neuronal excitability. *P < 0.05 vs. control; **P < 0.05 vs. HFD. D, representative traces illustrating the effects of apamin (100 nm) and charybdotoxin (40 nm) on the action potential after-hyperpolarization in HFD (left) and HFD-RYGB (right) DMV neurones. Note that, in HFD neurones, both apamin and charybdotoxin decreased the amplitude and duration of the after-hyperpolarization, suggesting the presence of both small conductance (SK) and large conductance (BK) calcium-dependent potassium currents. In contrast, following RYGB, only the apamin-sensitive small conductance (SK) calcium-dependent potassium current was observed, and charybdotoxin had no effect on after-hyperpolarization amplitude or duration.

The activation curve for IA was evoked by first hyperpolarizing the DMV membrane from a holding potential of −50 mV to −120 mV (400 ms duration) to remove the current inactivation, then step depolarizing the membrane from +20 to −70 mV in 10 mV increments (400 ms duration) before repolarizing back to −50 mV. As these depolarization steps may also result in activation of the delayed rectifier current, IKV, neurones were voltage clamped at −50 mV and then step depolarized from +20 to −70 mV in 10 mV increments without first hyperpolarizing the neurone to remove IA inactivation. This delayed rectifier outward current, IKV, was measured isochronically at the end of the depolarizing current step, averaged and plotted (Fig. 2D). The outward currents were also subtracted from the control IA activation currents, to allow measurement of the pure IA currents (see Fig. 3), which were normalized (Imax= 100), averaged and plotted (see Fig. 3).

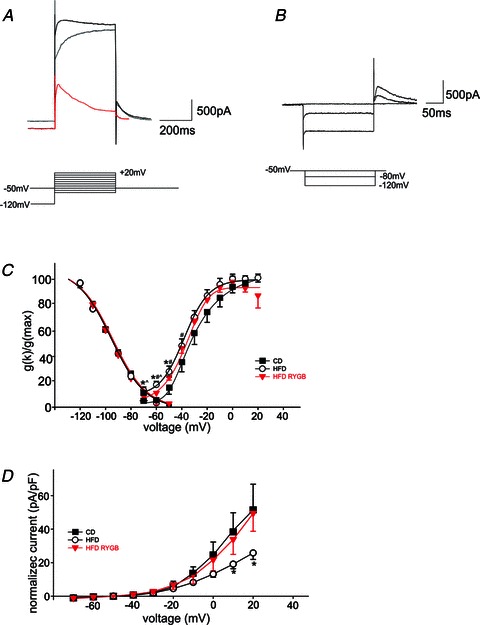

Figure 3. Gastric bypass surgery alters voltage-dependent potassium currents in DMV neurones.

A, representative traces illustrating the activation of the ensemble outward potassium currents (upper trace, black), or IKV (middle trace, grey) upon stepping the neuronal membrane from −120 mV (IA) or −50 mV (IKV) to +20 mV (IA). The lower (red) trace is the current obtained by subtraction of IKV from the ensemble current. The peak current obtained consists principally of IA. B, the voltage dependence of IA inactivation was measured in DMV neurones voltage clamped at −50 mV. Neurones were then step hyperpolarized (400 ms duration) in 10 mV increments, to −120 mV before being repolarized to −50 mV. The resultant current values were normalized (Imax= 100) and averaged. For the purposes of clarity, only traces from −50, −80 and −120 mV are shown. C, graphical representation of the voltage dependence of IA inactivation and activation. Note that while the voltage dependence of IA inactivation was unchanged between CD, HFD and HFD-RYGB neurones, in contrast there was a leftward shift in the voltage dependence of IA activation in HFD and HFD-RYGB neurones, with half-maximal activations of −30, −40 and −35 mV for CD, HFD and HFD-RYGB neurones, respectively. *P < 0.05 CD vs. HFD; #P < 0.05 CD vs. HFD-RYGB; ∧P < 0.05 HFD vs. HFD-RYGB. D, graphical representation of the normalized current–voltage relationship of the delayed rectifier, IKV. Note that, at potentials positive to +10 mV, the magnitude of IKV was reduced in DIO neurones, and this reduction was reversed following RYGB. *P < 0.05 HFD vs. CD and HFD-RYGB neurones. A) Representative traces showing the activation of the ensemble of potassium and calcium currents (upper trace) or IKV (middle trace, red) upon stepping to +20 mV from −120 mV (ensemble currents) or from −50 mV (IKV). The lower trace is the current obtained upon subtraction of the IKV from the ensemble current. The peak current obtained comprises IA mainly. For the purposes of clarity, only traces from –120 and −50 mV are shown. Similar results were obtained upon perfusion of the ensemble currents with 5 mm 4-AP (not shown). B) Activation curve of IKV in DMV neurones from untreated (control) and perivagal-CAP treated (capsaicin) rats. Note that at potentials positive to 0 mV, the peak IKV from capsaicin neurones is significantly reduced compared with control. C) Representative traces showing the inactivation of IA obtained upon hyperpolarization of the membrane from −50 to −120 mV and repolarization to −50 mV. For clarity purposes, only traces from −50, −80 and −120 mV are shown.

The delayed rectifier outward current, IKV, itself was measured isochronically at the end of the depolarizing current step, averaged and plotted (Fig. 3D).

Morphological properties

At the conclusion of the experiment, Neurobiotin® (2.5%; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA; included in the recording pipette) was injected into the neurone to allow subsequent assessment of neuronal morphology. Neurobiotin® was injected into the neurone by passing subthreshold depolarizing current pulses (400 ms; 0.8 Hz for 20 min) through the recording pipette. After removal of the pipette, the membrane was allowed to reseal for 10–20 min before the slice was fixed in Zamboni's fixative (see ‘Drugs and solutions’ below for composition) at 4°C for at least 24 h.

Brainstem slices were cleared of fixative by repeated washes in PBS containing Triton X-100 (see ‘Drugs and solutions’ below for composition). Slices were then incubated with avidin D–horseradish peroxidase solution (HRP; see ‘Drugs and solutions’ below for composition) for 2 h. After repeated washing in PBS containing Triton X-100, brainstem slices were incubated in a solution of PBS containing diaminobenzidine, cobalt chloride and nickel sulfate (30 min; see ‘Drugs and solutions’ below for composition). Slices were subsequently incubated in the presence of 3% H2O2 for a period of time sufficient for the adequate visualization of the neuronal morphological properties. Slices were mounted on gelatin-subbed slices, air dried, and dehydrated via a graded series of alcohols and xylene before being mounted in Permount (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA USA) Neurolucida (MBF Bioscience, Willison, VT, USA).

Neurolucida® software attached to a Nikon E400 microscope (final magnification ×400) was used to create three-dimensional reconstructions of individual Neurobiotin-filled neurones. The optical and physical compression of the slice that may have occurred during fixation and processing was corrected by a subroutine of the software that rescaled the section to 300 μm, the original thickness of the slices at the time of sectioning.

Morphological features assessed included soma area, form factor (a measure of soma circularity where 1 = perfect circle and 0 = straight line), dendritic branching (number of segments, branching order) and dendritic length (in both the X- and Y-axes). In order to be accepted, the neuronal reconstructions had to have a mediolateral and rostrocaudal branch extension of at least 200 μm, no major branches had to be severed during the initial sectioning of the brainstem slice, and the neuronal soma could not have been damaged during pipette retrieval.

Drug application and statistical analysis

Drugs were applied to DMV neurones via perfusion through a series of manually operated valves, at concentrations demonstrated previously to be effective (Baptista et al. 2005; Wan et al. 2007a,b; Browning et al. 2011). Given that DMV neurones are spontaneously active (Travagli & Gillis, 1994), sufficient current was injected into the neurone to set the action potential firing rate at approximately 1 Hz. Cholecystokinin-8s (CCK; 100 nm) and Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1; 100 nm) were applied for periods of time sufficient for the membrane response to reach a plateau, or a minimum of 3 min if the neurone was unresponsive. For a neurone to be considered responsive, drug perfusion had to induce an alteration in action potential firing frequency of >50%. Each neurone served as its own control, i.e. the response of any neurone was assessed before and after drug application using Students’ paired t test. Results are expressed as means ± SEM, with significance defined as P < 0.05.

Drugs and solutions

The composition of solutions was as follows.

Krebs' solution (mm): 126 NaCl, 25 NaHCO3, 2.5 KCl, 1.2 MgCl2, 2.4 CaCl2, 1.2 NaH2PO4 and 11 dextrose, maintained at pH 7.4 by bubbling with 95% O2–5% CO2.

Potassium gluconate intracellular solution (mm): 28 potassium gluconate, 10 KCl, 0.3 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 Hepes, 1 EGTA, 2 Na2ATP and 0.25 NaGTP, adjusted to pH 7.36 with KOH.

PBS containing Triton X-100 (mm): 115 NaCl, 75 Na2HPO4, 7.5 KH2PO4 and 0.15% Triton X-100.

Zamboni's fixative: 1.6% paraformaldehyde, 19 mm KH2PO4 and 100 mm Na2PO4 in 240 ml saturated picric acid and 1600 ml water, adjusted to pH 7.4 with NaOH.

Avidin-D–HRP solution: 0.002% avidin D–HRP in PBS containing 1% Triton X-100.

DAB solution: 0.05% DAB in PBS supplemented with 0.025% CoCl2 and 0.02% NiNH4SO4.

Tetrodotoxin (TTX) was purchased from Alomone Labs Ltd (Jerusalem, Israel). Neurobiotin and avidin D–HRP were purchased from Vector Laboratories (Burlingame, CA, USA). All other chemicals were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St Louis, MO, USA).

Results

A total of 84 male rats were used in the present study; 11 rats were used at 4–6 weeks of age after being maintained on control diet, i.e. juvenile-CD rats as used previously in our studies (Browning et al. 1999, 2005). Nineteen rats were fed a control diet for 12–16 weeks of age (CD; 556 ± 24 g) and thus were age matched to the HFD rats within the study. Thirty rats were fed HFD for 12–16 weeks but received no surgical interventions (HFD rats; 803 ± 58 g; P < 0.05 vs. CD rats). Seventeen rats were fed HFD for 12 weeks before undergoing gastric bypass surgery and lost significant weight as expected (HFD-RYGB rats; 485 ± 34 g; P < 0.05 vs. CD rats; P < 0.05 vs. HFD rats), while the remaining seven rats were fed a HFD for 12 weeks before undergoing sham surgery (sham-HFD rats; 740 ± 57 g; P < 0.05 vs. CD and HFD-RYGB rats; P > 0.05 vs. HFD rats).

Electrophysiological recordings were made from rats between 13 and 19 days after sham or gastric bypass surgery (mean 16.5 ± 0.6 days). By the time of experimentation, rats that had undergone gastric bypass surgery had lost an average of 19.5 ± 1.6% of their body weight, compared with sham-operated rats, which lost 0.5 ± 0.6% of their body weight (P < 0.05 vs. HFD-RYGB rats; P > 0.05 vs. weight prior to surgery; Fig. 1A).

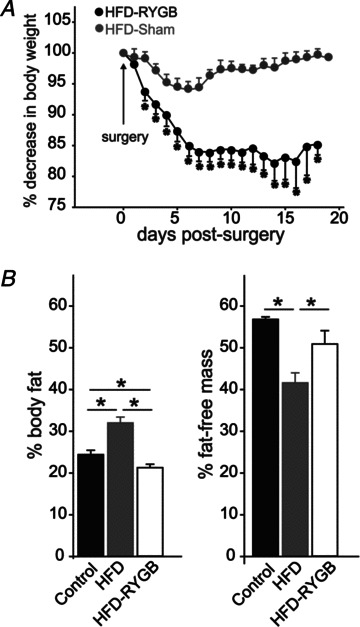

Figure 1. Graphical representation of the weight loss induced by gastric bypass surgery.

A, rats were fed a high-fat diet (HFD; 60% kcal from fat) for 12 weeks prior to gastric bypass surgery (RYGB) or sham surgery. Rat weights were monitored daily from the day of surgery until experimentation. Note that, despite being maintained on the same HFD postsurgery, RYGB rats lost an average of 19.5 ± 1.6% body weight, while the weight of sham-operated rats was unchanged (0.5 ± 0.6% starting body weight). B, graphical representation of the 1H NMR measurements of body composition in control diet-fed (CD) rats (n= 5), HFD rats (n= 23) and HFD-RYGB rats (n= 8). Note that HFD-induced obesity significantly increased fat mass and decreased fat free mass, relative to CD rats, and these changes were reversed following RYGB. *P < 0.05.

Body composition

As summarized in Fig. 1B, 1H NMR measurements demonstrated that HFD rats (n= 23) had increased fat mass (32.0 ± 1.4%, vs. 24.4 ± 1.0% for CD rats, n= 5; P < 0.05), decreased fat-free mass (41.6 ± 2.4%, vs. 56.8 ± 0.6% for CD rats, P < 0.05), indicating that the increased body weight was due to increased adiposity. Relative to HFD rats, however, gastric bypass (n= 8) decreased fat mass (21.3 ± 0.8%; P < 0.05 vs. HFD and CD rats) and increased fat-free mass (50.9 ± 3.2%, P < 0.05 vs. HFD rats), suggesting that the weight loss resulting from RYGB was due to loss of fat mass.

Electrophysiological results

Electrophysiological recordings were made from a total of 158 DMV neurones. Recordings were made from 30 neurones from 11 juvenile rats (juvenile-CD neurones), 30 neurones from 19 age-matched CD rats (CD neurones), 30 neurones from seven age-matched HFD-fed rats (HFD neurones), 45 neurones from nine HFD-fed rats that had undergone gastric bypass surgery (HFD-RYGB neurones) and 23 neurones from seven HFD-fed rats that underwent sham surgery (HFD-sham neurones). There were no significant differences in any electrophysiological, pharmacological or morphological properties in neurones from HFD rats compared with neurones from rats that had undergone sham surgery; these neurones were thus combined into one group (termed HFD neurones).

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass reverses DIO-induced effects upon basic membrane properties

The basic membrane properties of DMV neurones from juvenile-CD neurones, CD neurones, HFD neurones and HFD-RYGB neurones are summarized in Table 1. With age, the membrane input resistance of DMV neurones decreased (453 ± 36 MΩ for juvenile CD neurones vs. 314 ± 22 MΩ for CD neurones, P < 0.05). The input resistance of HFD neurones was further decreased to 269 ± 14 MΩ (P < 0.05 vs. CD neurones); following RYGB, however, the membrane input resistance of DMV neurones was restored to similar levels as neurones from CD rats (400 ± 37 MΩ; P > 0.05 vs. juvenile-CD or CD neurones; P < 0.05 vs. DIO neurones).

Table 1.

Basic membrane properties

| Property | Juvenile-CD (n= 30) | CD (n= 30) | HFD (n= 53) | HFD-RYGB (n= 45) | Statistics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANOVA: | |||||

| Input resistance (MΩ) | 453 ± 36CD | 314 ± 22 | 269 ± 15CD, HFD-RYGB | 400 ± 37 | F= 8.63, P= 2.47 × 10-5 |

| Action potential duration (ms) | 2.4 ± 0.2 | 2.5 ± 0.08 | 2.7 ± 0.11 | 2.7 ± 0.14 | — |

| After-hyperpolarization amplitude (mV) | 13.5 ± 0.8CD | 18.8 ± 1.0 | 17.4 ± 0.7RYGBS | 13.0 ± 0.7CD, HFD | F= 12.85, P= 1.56 × 10-7 |

| ANOVA: | |||||

| After-hyperpolarization duration (ms) | 179 ± 33 | 152 ± 36 | 156 ± 35 | 138 ± 20 | — |

| Action potential frequency response (pulses per second) | 3.7 ± 0.4 | 2.9 ± 0.4 | 2.2 ± 0.3 | 3.5 ± 0.5 | ANOVA: |

| 5.2 ± 0.5CTL | 3.6 ± 0.4 | 2.6 ± 0.3CD, HFD-RYGB | 5.5 ± 0.5CD HFD | F= 12.05, P= 1.82 × 10-5 | |

| 6.3 ± 0.6CTL | 4.1 ± 0.4 | 3.4 ± 0.3CD, HFD-RYGB | 6.7 ± 0.6CD, HFD | F= 14.77, P= 2.02 × 10-6 | |

| 7.7 ± 0.5CTL | 4.7 ± 0.5 | 3.9 ± 0.4CD, HFD-RYGB | 7.9 ± 0.4CD, HFD | F= 20.90, P= 1.98 × 10-8 | |

| 8.7 ± 0.6CTL | 5.3 ± 0.6 | 4.3 ± 0.4HFD-RYGB | 9.3 ± 0.7CD, HFD | F= 21.47, P= 1.31 × 10-8 |

CD = neurones from rats fed a control diet; HFD = neurones from rats fed a high fat diet: HFD-RYGB = neurones from rats fed a high fat diet that underwent RYGB surgery. Superscript CD, HFD, HFD-RYGB = P<0.05 vs CD, HFD, HFD-RYGB neurones.

These data suggest that both ageing and HFD-induced obesity decrease the membrane input resistance of DMV neurones, which was reversed following RYGB.

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass reverses DIO-induced effects upon action potential and after-hyperpolarization properties

The properties of single action potentials were assessed in DMV neurones current clamped at approximately −60 mV. As summarized in Table 1, there was no difference in action potential duration or after-hyperpolarization duration across all neuronal groups (P > 0.05). The amplitude of action potential after-hyperpolarization, however, was subject to alteration; with ageing, the after-hyperpolarization amplitude increased (from 13.0 ± 0.7 mV in juvenile-CD neurones to 18.8 ± 1.0 mV in CD neurones, P < 0.05), although HFD had no additional effect (17.4 ± 0.7 mV for HFD neurones, P > 0.05). Following RYGB, however, after-hyperpolarization amplitude was decreased significantly to levels observed in juvenile rats (13.0 ± 0.7 mV, P < 0.05 vs. CD neurones and HFD neurones, P > 0.05 vs. juvenile CD neurones; Fig. 2A).

In order to determine whether the smaller after-hyperpolarization in HFD-RYGB neurones alters the firing frequency of DMV neurones, the number of action potentials fired in response to injection of depolarizing current pulses (400 ms duration) of increasing current intensity was assessed. As summarized in Table 1, firing frequency decreased with ageing and decreased further in HFD neurones; RYGB reversed these actions such that firing frequency was similar to juvenile-CD neurones.

These results suggest that HFD-induced obesity renders DMV neurones even less excitable, hence neurones fire fewer action potentials in response to sustained membrane depolarization. Furthermore, this decrease in excitability is reversed following RYGB, despite rats being maintained on the same diet. These results suggest that ageing itself decreases action potential firing frequency, but that this age-induced decrease in excitability is also reversed completely following RYGB.

We, and others, have demonstrated previously that the after-hyperpolarization in DMV neurones is mediated, in large part, by apamin-sensitive (SK), but not charybdotoxin-sensitive (BK) calcium-dependent potassium currents (Sah, 1992, 1995; Browning et al. 1999). In order to investigate whether the contribution of calcium-dependent potassium currents to the action potential after-hyperpolarization is altered either following HFD-induced obesity or following RYGB, DMV neurones were current clamped at −60 mV prior to injection of depolarizing current pulses (15–20 ms) of intensity sufficient to evoke the firing of a single action potential at the current pulse offset. Neurones were then superfused with either apamin (100 nm) or charbydotoxin (40 nm) and the membrane was re-adjusted to −60 mV before re-evoking a single action potential.

Apamin decreased the after-hyperpolarization amplitude and duration in all neurones, with no significant differences being noted between CD (74 ± 5.6 and 52 ± 10% of amplitude and duration, respectively, P > 0.05), HFD (82 ± 3 and 67 ± 19% of amplitude and duration, respectively, P > 0.05) and HFD-RYGB neurones (67 ± 4 and 54 ± 9% of amplitude and duration, respectively, P > 0.05; Fig. 2D). In contrast to previously published reports (Sah, 1992, 1995; Browning et al. 1999), however, charybdotoxin decreased the amplitude and duration of the after-hyperpolarization in DMV neurones from CD (83 ± 3 and 75 ± 8% of amplitude and duration, respectively, P < 0.05) and HFD rats (85 ± 3 and 63 ± 9% of amplitude and duration, respectively, P < 0.05), but had no effect on HFD-RYGB neurones (104 ± 3 and 103 ± 14% of amplitude and duration, respectively, P > 0.05; Fig. 2D).

These results suggest that, unlike DMV neurones from juvenile CD rats (Sah, 1992, 1995; Browning et al. 1999), DMV neurones from CD rats as well as HFD rats displayed a charybdotoxin-sensitive (BK) calcium-dependent potassium current in addition to the ubiquitous apamin-sensitive (SK) calcium-dependent potassium current. Following RYGB, however, this charybdotoxin-sensitive (BK) current was absent, suggesting that the loss of this current may be responsible, at least in part, for the smaller after-hyperpolarization and increased action potential firing frequency observed in HFD-RYGB neurones.

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass reverses DIO-induced effects upon voltage-dependent potassium currents

The voltage dependence of inactivation as well as activation of the fast transient outward potassium current, IA, was calculated for CD, HFD and HFD-RYGB neurones (n= 4–12). As illustrated in Fig. 3, the voltage dependence of IA activation was calculated by subtracting the current evoked following depolarizing current steps with (A) and without removing IA inactivation (B). The resulting current trace (A, red trace), along with the voltage dependence of IA inactivation are plotted as percentages of the total evoked currrent (C).

The voltage dependence of IA inactivation was unchanged between CD, HFD and HFD-RYGB neurones. In contrast, there was a leftward shift in the voltage dependence of IA activation in HFD and HFD-RYGB neurones. The half-maximal activation for control DMV neurones was estimated to be −30 mV, whereas it was estimated to be −40 mV in HFD neurones. This leftward shift was partly reversed following RYGB (estimated half-maximal activation voltage =−35 mV).

These results suggest that, following HFD-induced obesity, an IA window current is opened, suggesting that a greater proportion of the fast transient IA current is active at resting potentials, which may, in part, be responsible for the slower frequency of action potential firing in these conditions. This shift in the voltage dependence of IA activation is partly reversed following RYGB, implying that less of the current is active at resting potentials, resulting in a faster frequency of action potential firing.

The delayed rectifier, IKV, was also assessed in CD, HFD and HFD-RYGB neurones (n= 4–12) and normalized relative to membrane capacitance (in picoamperes per picofarad; calculated by applying repetitive square-wave voltage-command pulses (10 mV) to the cell and fitting the resulting transient to Cm=Qt/ΔV, where Cm is membrane capacitance, Qt is the total charge under the transient response to the square-wave voltage command and ΔV is the change in voltage across the membrane). At membrane potentials positive to 10 mV, the evoked outward current was reduced following HFD (Fig. 3D), and this reduction was reversed following RYGB.

These results suggest that, following HFD-induced obesity, there is a reduced activation of the potassium delayed rectifier current, leading to a delay in action potential repolarization. In turn, this may increase calcium entry during the action potential, which may, in part, be responsible for the larger after-hyperpolarization observed in these neurones.

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass reverses the DIO-induced loss of responsiveness of DMV neurones to CCK and GLP-1

Previous studies from this and other laboratories have demonstrated that gastric-projecting DMV neurones respond to a variety of satiety-related neuropeptides and neurohormones with an alteration in membrane potential and/or alteration in spontaneous action potential firing rate. Studies investigating the effects of diet on the response of vagal neurocircuits to satiety-related neuropeptides and neurohormones have demonstrated that vagal afferent fibres and neurones become less sensitive to CCK and GLP-1 following induction of obesity. In order to investigate the effects of HFD-induced obesity and RYGB on the pharmacological responsiveness of brainstem neurones, DMV neurones were current clamped to a membrane potential sufficient to evoke a spontaneous firing frequency of ∼1 Hz. Neurones were then superfused with CCK and/or GLP-1 at concentrations demonstrated previously to induce a response (100 nm for both; Wan et al. 2007a,b). Six of nine CD neurones (67%) responded to superfusion of CCK with an increase in action potential firing frequency (234 ± 40% of control firing rate) that recovered following wash-out. In contrast, only five of 23 HFD neurones (22%; P < 0.05 vs. control neurones) responded to CCK with an increase in action potential firing frequency (249 ± 24%; Fig. 4). Following RYGB, however, nine of 17 HFD-RYGB neurones (53%) increased their firing frequency in response to superfusion with CCK (360 ± 109% of control firing rate), which was significantly different from the proportion of responding HFD neurones (P < 0.05; Fig. 4), but similar to the proportion of responding DMV neurones observed in CD rats (P > 0.05).

Figure 4. Gastric bypass surgery restores the responsiveness of DMV neurones to CCK.

A, representative traces from HFD (top trace) and HFD-RYGB DMV neurones (bottom trace) illustrating the response to superfusion with CCK (100 nm). Neurones were current clamped to allow a spontaneous action potential firing frequency of ∼1 Hz, before superfusion with 100 nm CCK for a period of time sufficient for the response to reach a plateau. The majority of HFD neurones were unresponsive to CCK, whereas, following RYGB, the majority of DMV neurones responded to CCK with a membrane depolarization and an increase in action potential firing. B, graphical representation of the proportion of CD, HFD and HFD-RYGB neurones that responded to CCK with an increase in action potential firing rate (left bars) and the magnitude of the increase in firing frequency (right bars). *P < 0.05 vs. control; **P < 0.05 vs. RYGB.

Likewise, while four of seven (57%) CD neurones responded to GLP-1 with an increase in firing frequency (263 ± 40% of control firing rate), only three of 21 HFD neurones (14%; P < 0.05 vs. control neurones) were responsive (334 ± 153% of control firing rate). Following RYGB, however, eight of 10 (80%) of neurones responded to GLP-1 with an increase in firing rate (220 ± 23% of control firing rate), which was significantly different from the proportion of responding HFD neurones (P < 0.05), but similar to the proportion of responding CD neurones (P > 0.05).

These results suggest that the responses of DMV neurones to the satiety-related neurohormones CCK and GLP-1 are blunted following HFD-induced obesity, and that the effects of HFD-induced obesity to attenuate the response of DMV neurones to satiety-related neurohormones is reversed following RYGB.

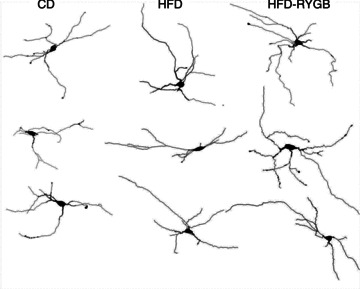

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass does not reverse the DIO-induced alterations in morphological properties of DMV neurones

Complete morphological reconstructions were obtained from 17 CD neurones, 23 HFD neurones and 26 HFD-RYGB neurones. As summarized in Table 2, the dendritic extent of CD DMV neurones was smaller than that of HFD neurones and HFD-RYGB neurones in X-axis and Y-axis length (P < 0.05 for each), although no differences were observed in soma area or diameter (P > 0.05 for both). Further differences between CD and HFD neurones or HFD-RYGB neurones were apparent in the number of segment ‘ends’ and branch order (P < 0.05 for both), suggesting that dendritic branching had increased (Fig. 5).

Table 2.

Morphological characteristics

| Characteristic | CD (n= 17) | HFD (n= 23) | HFD-RYGB (n= 26) | Statistics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soma area (micrometres squared) | 259 ± 27 | 264 ± 22 | 242 ± 38 | — |

| Soma diameter (micrometres) | 25.7 ± 1.6 | 25.2 ± 1.4 | 24.2 ± 1.4 | — |

| Form factor (NO UNITS) | 0.60 ± 0.05 | 0.54 ± 0.05 | 0.46 ± 0.05CD | — |

| Dendritic extent, X-axis (micrometres) | 198 ± 23 | 304 ± 27CD, HFD-RYGB | 392 ± 39CD, HFD | ANOVA: F= 5.444, P= 0.0022 |

| Dendritic extent, Y-axis (micrometres) | 89 ± 16 | 147 ± 16CD, HFD-RYGB | 207 ± 25CD, HFD | ANOVA: F= 4.96, P= 0.0038 |

| Segment ends (NO UNITS) | 5.20 ± 0.48 | 8.65 ± 0.61CD | 9.12 ± 0.52CD | ANOVA: F= 10.88, P= 1.03 × 10-5 |

| Segment length (micrometres) | 171 ± 23.0 | 199 ± 12.7 | 206 ± 11.9 | — |

| Branch order (NO UNITS) | 2.13 ± 0.19 | 3.35 ± 0.24CD | 3.71 ± 0.24CD | ANOVA: F= 8.40, P= 0.00011 |

Figure 5. Gastric bypass surgery does not alter the morphological properties of DMV neurones.

Computer-aided reconstructions of representative Neurobiotin-filled neurones from CD, HFD and HFD-RYGB rats. Note that, compared with neurones from control rats, diet-induced obesity increased the extent of dendritic arborization. These morphological changes were not reversed by RYGB, suggesting that they are due to the diet, rather than obesity.

These data suggest that HFD-induced obesity alters the morphological properties of DMV neurones. These morphological changes were not reversed following RYGB, suggesting that they may be more dependent upon diet, rather than obesity.

Discussion

The results from the present study demonstrate that HFD-induced obesity caused alterations in the biophysical and pharmacological properties of DMV neurones and that these alterations were reversed following RYGB. In particular, HFD-induced obesity decreased the membrane input resistance of DMV neurones and decreased neuronal excitability (increased action potential after-hyperpolarization, decreased action potential firing frequency, opening of an IA window current at resting membrane potential and decreased delayed rectifier current) as well as decreasing their responsiveness to the satiety neuropeptides CCK and GLP-1. While all of these biophysical and pharmacological effects of diet-induced obesity were reversed following RYGB, in contrast, the obesity-induced alterations in morphological properties were unaltered by RYGB.

Given that rats were maintained on the same HFD following RYGB, these data suggest that obesity, but not exposure to a HFD per se, altered the biophysical and pharmacological properties of central vagal motoneurones, because these changes were reversed following RYGB-induced weight loss, and that HFD, but not obesity, altered the morphological properties of DMV neurones, because these morphological differences were not reversed following RYGB-induced weight loss.

While RYGB is the most effective treatment for morbid obesity and its associated conditions, the exact mechanism by which it alters satiation and food intake remain to be elucidated fully, although several recent studies have highlighted alterations in GI neuroendocrine functions, including alterations in the secretion and actions of GI neurohormones, as playing important roles (Ochner et al. 2010; Berthoud et al. 2011). Several excellent reviews have highlighted the paracrine action of the GI neurohormones in normal conditions to activate vagal afferent signalling to the brainstem and regulate visceral and GI reflex homeostasis (Raybould & Tache, 1988; Holzer et al. 1994; Owyang, 1996; Raybould, 1998, 2007; Takahashi & Owyang, 1999; Li et al. 2001), although direct actions at the level of the brainstem neurocircuits should not be ignored or underplayed (Branchereau et al. 1993; Blevins et al. 2000; Appleyard et al. 2005; van de Wall et al. 2005; Zheng et al. 2005; Baptista et al. 2007; Sullivan et al. 2007; Wan et al. 2007a; Holmes et al. 2009). The actions of RYGB to alter vagally mediated visceral and GI reflexes have received scant attention.

While the important role that vagal sensory afferents play in the regulation of food intake is almost universally acknowledged, most overarching explanations of the neural regulation of energy balance relegate visceral afferent signalling as being important only in short-term satiety signalling (Abizaid & Horvath, 2008; Berthoud, 2008; Berthoud & Morrison, 2008). Relatively little consideration has been paid to the possibility that vagal neurocircuits, including vagal efferent motoneurones, may play more prominent and adaptable roles in longer term regulation of food intake and the development of obesity. In this regard, it has become apparent that vagally mediated reflexes are not static relay networks, where sensory inputs trigger stereotypical unmodulated output responses. Rather, vagal neurocircuits appear remarkably plastic and, in addition to modulating their responses following insult or injury (Moore et al. 2000; Bielefeldt et al. 2002a,b; Kollarik & Undem, 2002; Myers et al. 2002; Mei et al. 2003; Dang et al. 2004; Tolstykh et al. 2004; Kollarik et al. 2007; Hermes et al. 2008; Zhang et al. 2008), they appear capable of modulating their responses according to ongoing physiological demands (Burdyga et al. 2006; Dockray, 2009; Browning & Travagli, 2011), perhaps even on a minute-to-minute basis (Babic et al. 2012). It is well established that HFD, or HFD-induced obesity, alters the activity, sensitivity and responsiveness of vagal afferent nerves in rodents (Daly et al. 2011; de Lartigue et al. 2011; Kentish et al. 2012) and decreases the afferent-induced activation of NTS neurones within the brainstem (Covasa et al. 2000a,b; Donovan et al. 2007; Little et al. 2007; Nefti et al. 2009). Few studies have investigated the effects of diet or obesity on vagal afferent neurones themselves, although Daly et al. (2011) showed a decrease in the excitability of mouse vagal afferent neurones as a consequence of DIO.

The present study is the first to use electrophysiological techniques to investigate the effects of diet-induced obesity on the biophysical, morphological and pharmacological properties of central brainstem neurones involved in the homeostatic regulation of visceral functions. Although care was taken to try to avoid damage to the subdiaphragmatic vagus, the gastric bypass surgery itself almost certainly severs vagal afferent and efferent terminals at the level of the stomach, which could be responsible for some of the alterations in DMV neuronal properties observed in the present study. Indeed, we, and others, have demonstrated that vagotomy can induce vagal efferent neuronal damage, including degeneration and cell death (Lin et al. 1997; Ji et al. 2005; Saito et al. 2009; Browning et al. 2013). It is likely, therefore, that such damaged neurones would have degenerated before the electrophysiological recordings were made in the present study (13–19 days after surgery) or would have been excluded from recording based on their clearly degenerating somata. Likewise, it should also be considered that sectioning of peripheral vagal afferent terminals may reduce sensory inputs onto brainstem neurones, which may alter their properties. It should be noted, however, that the properties of DMV neurones were not altered following selective surgical deafferentation procedures (Browning et al. 2013), suggesting that the alterations in DMV neuronal properties observed in the present study are due to actions of diet and obesity, rather than surgical intervention.

Several studies from this and other laboratories have shown that DMV neurones are pacemakers, firing action potentials spontaneously at approximately 1Hz (Travagli et al. 2006; Browning & Travagli, 2011). Although DMV neuronal activity is modulated constantly by synaptic inputs from NTS as well as from other brainstem nuclei (Travagli et al. 1991; Babic et al. 2011), this spontaneous activity arises, in part, from intrinsic properties of DMV neuronal membranes (Travagli & Gillis, 1994). In comparison to age-matched rats fed a control diet, the present study demonstrated that DIO decreased the excitability of vagal efferent motoneurones via multiple actions on the neuronal membrane, including the following: (i) the activation of membrane conductance(s) at resting membrane potentials; (ii) delayed action potential repolarization due to a decrease in the delayed rectifier potassium conductance, IKV; (iii) increased activation of the transient outward potassium current, IA, at resting membrane potentials via the opening of a window current; and (iv) increased action potential after-hyperpolarization due to activation of a charybdotoxin-sensitive (BK) calcium-dependent potassium current. The cumulative effect of these alterations was to decrease the excitability of vagal efferent motoneurones and decrease their action potential firing frequency. The present study suggests, therefore, that vagal efferent (motor) output per se may be compromised by DIO, independently of the well-described decrease in visceral afferent (sensory) input (Covasa et al. 2000a,b; Covasa & Ritter, 2005; Daly et al. 2011).

All of these actions of HFD-induced obesity to decrease DMV neuronal excitability were reversed following RYGB. Importantly, these RYGB-induced effects were observed while rats were maintained on the same HFD, implying that obesity, rather than the diet itself, was responsible for the decreased neuronal excitability. Interestingly, the increased neuronal excitability observed in DMV neurones following RYGB-induced weight loss restored action potential firing frequency to that observed in juvenile rats (4–6 weeks old). This would suggest that DMV neuronal excitability is not only decreased in adult rats (or the obesity associated with adulthood and ageing in rats), but that these effects are also reversible following RYGB. Decreased neuronal excitability often accompanies ageing due, in part, to intracellular calcium dysregulation and increased action potential after-hyperpolarization (Landfield & Pitler, 1984; Foster & Kumar, 2002; Nikoletopoulou & Tavernarakis, 2012), similar to that observed in the present study. Clearly, it remains to be determined whether the observed RYGB-dependent restoration of DMV neuronal excitability is due to weight loss and decreased adiposity, or whether it is due to reversal of ageing-induced calcium dysregulation.

As has been reported peripherally for vagal afferent neurones (Daly et al. 2011), the present study demonstrated that HFD-induced obesity decreased the proportion of vagal efferent motoneurones that were excited by exogenous application of either CCK or GLP-1. Of the few neurones that did respond, however, the magnitude of the increase in action potential firing rate was similar to that of control neurones, suggesting that the lack of response was unlikely to be due to the generalized decrease in DMV neuronal excitability accompanying DIO. Rather, as has been proposed for vagal afferent neurones, the observed decrease in responsiveness may be due to changes in either receptor density or receptor–effector coupling (Nefti et al. 2009). Following RYGB, however, the responsiveness of DMV neurones to both CCK and GLP-1 was restored. Again, these effects were observed while rats were maintained on the same HFD, implying that obesity, more than the diet itself, was responsible for the decreased responsiveness to CCK and GLP-1. Previous studies have demonstrated that, following RYGB, postprandial levels of GLP-1 are increased (le Roux et al. 2006), while basal GLP-1 levels are also elevated in a genetically obese rat model (Meirelles et al. 2009). Enhanced release of GLP-1 from the ileum following RYGB may be, in part, responsible for the increase, although a plausible alternative source of GLP-1 from the colon has been discovered recently (Geraedts et al. 2012; Iakoubov & Lauffer, 2012). Together with the present study, these data suggest that RYGB not only increases circulating levels of GLP-1, but also restores the ability of central neurones to respond to this neurohormone.

Previous studies have demonstrated that obesity induces gliosis and decreases neurogenesis in hypothalamic neurones and decreases synaptic density on pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) neurones within the arcuate nucleus (Horvath et al. 2010). The present study demonstrated that DIO increased the size of DMV neurones as well as the apparent extent of dendritic arborization. The morphological properties of DMV neurones are known to be correlated with, although they do not dictate, their biophysical and electrophysiological properties (Browning et al. 1999; Valenzuela et al. 2004). Although RYGB reversed all the electrophysiological and pharmacological effects of DIO on DMV neurones, it was ineffective in restoring the alterations in neuronal morphology, suggesting that diet, rather than obesity, may be responsible for these morphological alterations, and that these morphological alterations are not responsible for the adaptations in electrophysiological or pharmacological properties.

Summary and conclusions

The results of the present study demonstrate that the effects of diet-induced obesity to compromise vagovagal reflex functions are not restricted to actions at peripheral vagal afferent neurones and nerves, but also alter the properties and responsiveness of central brainstem neurones. These effects appear largely reversible following RYGB-induced weight loss, implying that vago-vagal neurocircuits remain open to modulation and adaptation throughout life, and that the effects of long-term conditions such as obesity do not necessarily result in permanent and irrecoverable rewiring of brainstem neural circuitry. The ready reversibility of these diet-induced obesity-driven changes in neuronal properties suggests that vagal neurocircuits may present attractive, and more readily accessible, targets for obesity research.

Translational perspective

Diet-induced obesity (DIO) has been shown previously to alter the biophysical and pharmacological properties of gastrointestinal vagal afferent (sensory) neurones and fibres but, to our knowledge, there have been no studies investigating the effects of DIO on the biophysical or pharmacological properties of central vagal neurons. In this study, we used electrophysiological techniques to investigate the effects of DIO on the biophysical, pharmacological and morphological properties of brainstem vagal efferent motoneurones and whether the effects of DIO were reversed following weight loss induced by Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB). In this study, we demonstrate, for the first time, that DIO affects the properties of central autonomic neurones by decreasing neuronal excitability and attenuating the response of these neurones to the satiety neurohormones cholecystokinin and glucagon-like peptide 1. These DIO-induced changes were reversed following RYGB, suggesting that these alterations were due to obesity rather than diet. In contrast, the DIO-induced morphological alterations in neurones in the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus were not reversed following RYGB, suggesting that these effects may be to due diet, rather than obesity. The findings outlined in the present study represent the first direct evidence for the role of RYGB to improve the functioning and responsiveness of central vagal neurocircuits by reversing some of the effects of chronic high-fat diet.

Acknowledgments

Funds were provided by NIH DK078364 and NSF IOS1148978 to K.N.B. and NIH DK080899 to A.H. The authors would like to thank W. Nairn Browning for support and encouragement and R. Alberto Travagli for his helpful discussions and critical comments on earlier versions of this manuscript.

Glossary

- CCK

cholecystokinin

- CD

control diet

- DIO

diet-induced obesity

- DMV

dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus

- GI

gastrointestinal

- GLP-1

glucagon-like peptide 1

- HFD

high-fat diet

- IA

fast transient outward potassium current

- IKV

delayed rectifier current

- NTS

nucleus of the tractus solitarius

- POMC

pro-opiomelanocortin

- RYGB

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass

Author contributions

K.N.B. and A.H. designed the study. K.N.B. and S.R.F. performed the experiments. K.N.B. analysed the data. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript and approved the final version for publication.

References

- Abizaid A, Horvath TL. Brain circuits regulating energy homeostasis. Regul Pept. 2008;149:3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alywin ML, Horowitz JM, Bonham AC. NMDA receptors contribute to primary visceral afferent transmission in the nucleus of the solitary tract. J Neurophysiol. 1997;77:2539–2548. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.5.2539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andresen MC, Yang M. Non-NMDA receptors mediate sensory afferent synaptic transmission in medial nucleus tractus solitarius. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1990;259:H1307–H1311. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1990.259.4.H1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appleyard SM, Bailey TW, Doyle MW, Jin YH, Smart JL, Low MJ, Andresen MC. Proopiomelanocortin neurons in nucleus tractus solitarius are activated by visceral afferents: regulation by cholecystokinin and opioids. J Neurosci. 2005;25:3578–3585. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4177-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babic T, Browning KN, Travagli RA. Differential organization of excitatory and inhibitory synapses within the rat dorsal vagal complex. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2011;300:G21–G32. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00363.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babic T, Troy AE, Fortna SR, Browning KN. Glucose-dependent trafficking of 5-HT3 receptors in rat gastrointestinal vagal afferent neurons. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;24:e476–e488. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2012.01987.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baptista V, Browning KN, Travagli RA. Effects of cholecystokinin-8s in the nucleus tractus solitarius of vagally deafferented rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;292:R1092–R1100. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00517.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baptista V, Zheng ZL, Coleman FH, Rogers RC, Travagli RA. Cholecystokinin octapeptide increases spontaneous glutamatergic synaptic transmission to neurons of the nucleus tractus solitarius centralis. J Neurophysiol. 2005;94:2763–2771. doi: 10.1152/jn.00351.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthoud HR. The vagus nerve, food intake and obesity. Regul Pept. 2008;149:15–25. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2007.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthoud HR, Morrison C. The brain, appetite, and obesity. Annu Rev Psychol. 2008;59:55–92. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthoud HR, Shin AC, Zheng H. Obesity surgery and gut–brain communication. Physiol Behav. 2011;105:106–119. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielefeldt K, Ozaki N, Gebhart GF. Experimental ulcers alter voltage-sensitive sodium currents in rat gastric sensory neurons. Gastroenterology. 2002a;122:394–405. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.31026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielefeldt K, Ozaki N, Gebhart GF. Mild gastritis alters voltage-sensitive sodium currents in gastric sensory neurons in rats. Gastroenterology. 2002b;122:752–761. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.31901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blevins JE, Stanley BG, Reidelberger RD. Brain regions where cholecystokinin suppresses feeding in rats. Brain Res. 2000;860:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)02477-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branchereau P, Champagnat J, Denavit-Saubié M. Cholecystokinin-gated currents in neurons of the rat solitary complex in vitro. J Neurophysiol. 1993;70:2584–2595. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.70.6.2584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning KN, Babic T, Holmes GM, Swartz EM, Travagli RA. A critical re-evaluation of the specificity of action of perivagal capsaicin. J Physiol. 2013;591:1562–1580. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.246827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning KN, Coleman FH, Travagli RA. Characterization of pancreas-projecting rat dorsal motor nucleus of vagus neurons. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;288:G950–G955. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00549.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning KN, Hajnal A. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery alters the membrane properties of brainstem neurons. FASEB J. 2012a;26 889.6. [Google Scholar]

- Browning KN, Hajnal A. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery increases the response of central vagal neurons to satiety neuropeptides. FASEB J. 2012b;26 889.7. [Google Scholar]

- Browning KN, Renehan WE, Travagli RA. Electrophysiological and morphological heterogeneity of rat dorsal vagal neurones which project to specific areas of the gastrointestinal tract. J Physiol. 1999;517:521–532. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0521t.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning KN, Travagli RA. Plasticity of vagal brainstem circuits in the control of gastrointestinal function. Auton Neurosci. 2011;161:6–13. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2010.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning KN, Wan S, Baptista V, Travagli RA. Vanilloid, purinergic, and CCK receptors activate glutamate release on single neurons of the nucleus tractus solitarius centralis. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2011;301:R394–R401. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00054.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burdyga G, Varro A, Dimaline R, Thompson DG, Dockray GJ. Feeding-dependent depression of melanin-concentrating hormone and melanin-concentrating hormone receptor-1 expression in vagal afferent neurones. Neuroscience. 2006;137:1405–1415. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.10.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covasa M, Grahn J, Ritter RC. High fat maintenance diet attenuates hindbrain neuronal response to CCK. Regul Pept. 2000a;86:83–88. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(99)00084-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covasa M, Grahn J, Ritter RC. Reduced hindbrain and enteric neuronal response to intestinal oleate in rats maintained on high-fat diet. Auton Neurosci. 2000b;84:8–18. doi: 10.1016/S1566-0702(00)00176-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covasa M, Ritter RC. Reduced CCK-induced Fos expression in the hindbrain, nodose ganglia, and enteric neurons of rats lacking CCK-1 receptors. Brain Res. 2005;1051:155–163. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly DM, Park SJ, Valinsky WC, Beyak MJ. Impaired intestinal afferent nerve satiety signalling and vagal afferent excitability in diet induced obesity in the mouse. J Physiol. 2011;589:2857–2870. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.204594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang K, Bielefeldt K, Gebhart GF. Gastric ulcers reduce A-type potassium currents in rat gastric sensory ganglion neurons. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2004;286:G573–G579. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00258.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lartigue G, de La Serre CB, Raybould HE. Vagal afferent neurons in high fat diet-induced obesity; intestinal microflora, gut inflammation and cholecystokinin. Physiol Behav. 2011;105:100–105. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.02.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dockray GJ. The versatility of the vagus. Physiol Behav. 2009;97:531–536. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan MJ, Paulino G, Raybould HE. CCK1 receptor is essential for normal meal patterning in mice fed high fat diet. Physiol Behav. 2007;92:969–974. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster TC, Kumar A. Calcium dysregulation in the aging brain. Neuroscientist. 2002;8:297–301. doi: 10.1177/107385840200800404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geraedts MC, Takahashi T, Vigues S, Markwardt ML, Nkobena A, Cockerham RE, Hajnal A, Dotson CD, Rizzo MA, Munger SD. Transformation of postingestive glucose responses after deletion of sweet taste receptor subunits or gastric bypass surgery. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2012;303:E464–E474. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00163.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Hermes SM, Mitchell JL, Silverman MB, Lynch PJ, McKee BL, Bailey TW, Andresen MC, Aicher SA. Sustained hypertension increases the density of AMPA receptor subunit, GluR1, in baroreceptive regions of the nucleus tractus solitarii of the rat. Brain Res. 2008;1187:125–136. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.10.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes GM, Tong M, Travagli RA. Effects of brain stem cholecystokinin-8s on gastric tone and esophageal-gastric reflex. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2009;296:G621–G631. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90567.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzer HH, Turkelson CM, Solomon TE, Raybould HE. Intestinal lipid inhibits gastric emptying via CCK and a vagal capsaicin-sensitive afferent pathway in rats. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 1994;267:G625–G629. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1994.267.4.G625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath TL, Sarman B, García-Cáceres C, Enriori PJ, Sotonyi P, Shanabrough M, Borok E, Argente J, Chowen JA, Perez-Tilve D, Pfluger PT, Brönneke HS, Levin BE, Diano S, Cowley MA, Tschöp MH. Synaptic input organization of the melanocortin system predicts diet-induced hypothalamic reactive gliosis and obesity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:14875–14880. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004282107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iakoubov R, Lauffer LM. T1R3: how to indulge the gut's sweet tooth. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2012;303:E813–E814. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00418.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji JF, Dheen ST, Kumar SD, He BP, Tay SS. Expressions of cytokines and chemokines in the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus nerve after right vagotomy. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2005;142:47–57. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2005.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kentish S, Li H, Philp LK, O’Donnell TA, Isaacs NJ, Young RL, Wittert GA, Blackshaw LA, Page AJ. Diet-induced adaptation of vagal afferent function. J Physiol. 2012;590:209–221. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.222158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollarik M, Ru F, Undem BJ. Acid-sensitive vagal sensory pathways and cough. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2007;20:402–411. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollarik M, Undem BJ. Mechanisms of acid-induced activation of airway afferent nerve fibres in guinea-pig. J Physiol. 2002;543:591–600. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.022848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landfield PW, Pitler TA. Prolonged Ca2+-dependent afterhyperpolarizations in hippocampal neurons of aged rats. Science. 1984;226:1089–1092. doi: 10.1126/science.6494926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- le Roux CW, Aylwin SJ, Batterham RL, Borg CM, Coyle F, Prasad V, Shurey S, Ghatei MA, Patel AG, Bloom SR. Gut hormone profiles following bariatric surgery favor an anorectic state, facilitate weight loss, and improve metabolic parameters. Ann Surg. 2006;243:108–114. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000183349.16877.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Wu XY, Zhu JX, Owyang C. Intestinal serotonin acts as paracrine substance to mediate pancreatic secretion stimulated by luminal factors. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2001;281:G916–G923. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.281.4.G916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin LH, Sandra A, Boutelle S, Talman WT. Up-regulation of nitric oxide synthase and its mRNA in vagal motor nuclei following axotomy in rat. Neurosci Lett. 1997;221:97–100. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(96)13287-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little TJ, Horowitz M, Feinle-Bisset C. Modulation by high-fat diets of gastrointestinal function and hormones associated with the regulation of energy intake: implications for the pathophysiology of obesity. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86:531–541. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/86.3.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewy AD. Forebrain nuclei involved in autonomic control. Prog Brain Res. 1991;87:253–268. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)63055-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mei L, Zhang J, Mifflin S. Hypertension alters GABA receptor-mediated inhibition of neurons in the nucleus of the solitary tract. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2003;285:R1276–R1286. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00255.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meirelles K, Ahmed T, Culnan DM, Lynch CJ, Lang CH, Cooney RN. Mechanisms of glucose homeostasis after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery in the obese, insulin-resistant Zucker rat. Ann Surg. 2009;249:277–285. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181904af0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore KA, Undem BJ, Weinreich D. Antigen inhalation unmasks NK-2 tachykinin receptor-mediated responses in vagal afferents. Am J Resp Crit Care Med. 2000;161:232–236. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.1.9903091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers AC, Kajekar R, Undem BJ. Allergic inflammation-induced neuropeptide production in rapidly adapting afferent nerves in guinea pig airways. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2002;282:L775–L781. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00353.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nefti W, Chaumontet C, Fromentin G, Tome D, Darcel N. A high-fat diet attenuates the central response to within-meal satiation signals and modifies the receptor expression of vagal afferents in mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2009;296:R1681–R1686. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90733.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikoletopoulou V, Tavernarakis N. Calcium homeostasis in aging neurons. Front Genet. 2012;3:200. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2012.00200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochner CN, Gibson C, Carnell S, Dambkowski C, Geliebter A. The neurohormonal regulation of energy intake in relation to bariatric surgery for obesity. Physiol Behav. 2010;100:549–559. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2010.04.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owyang C. Physiological mechanisms of cholecystokinin action on pancreatic secretion. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 1996;271:G1–G7. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1996.271.1.G1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulino G, Barbier de la Serre C, Knotts TA, Oort PJ, Newman JW, Adams SH, Raybould HE. Increased expression of receptors for orexigenic factors in nodose ganglion of diet-induced obese rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;296:E898–E903. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90796.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pronchuk N, Colmers WF. NPY presynaptic actions are reduced in the hypothalamic mpPVN of obese (fafa), but not lean, Zucker rats in vitro. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;141:1032–1036. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raybould HE. Does your gut taste? Sensory transduction in the gastrointestinal tract. News Physiol Sci. 1998;13:275–280. doi: 10.1152/physiologyonline.1998.13.6.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raybould HE. Mechanisms of CCK signaling from gut to brain. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2007;7:570–574. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raybould HE, Tache Y. Cholecystokinin inhibits gastric motility and emptying via a capsaicin-sensitive vagal pathway in rats. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 1988;255:G242–G246. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1988.255.2.G242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinaman L. Postnatal development of central feeding circuits. In: Stricker E, Woods S, editors. Neurobiology of Food and Fluid Intake. New York: Plenum Publishers; 2004. pp. 159–194. [Google Scholar]

- Sah P. Role of calcium influx and buffering in the kinetics of a Ca2+-activated K+ current in rat vagal motoneurons. J Neurophysiol. 1992;65:2237–2247. doi: 10.1152/jn.1992.68.6.2237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sah P. Different calcium channels are coupled to potassium channels with distinct physiological roles in vagal neurons. Proc Biol Sci. 1995;260:105–111. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1995.0066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito A, Sato T, Okano H, Toyoda K, Bamba H, Kimura S, Bellier JP, Matsuo A, Kimura H, Hisa Y, Tooyama I. Axotomy alters alternative splicing of choline acetyltransferase in the rat dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus nerve. J Comp Neurol. 2009;513:237–248. doi: 10.1002/cne.21959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz MW, Woods SC, Porte D, Seeley RJ, Baskin DG. Central nervous system control of food intake. Nature. 2000;404:661–671. doi: 10.1038/35007534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanswick D, Smith MA, Groppi VE, Logan SD, Ashford MLJ. Leptin inhibits hypothalamic neurons by activation of ATP-sensitive potassium channels. Nature. 1997;390:521–525. doi: 10.1038/37379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan CN, Raboin SJ, Gulley S, Sinzobahamvya NT, Green GM, Reeve JR, Jr, Sayegh AI. Endogenous cholecystokinin reduces food intake and increases Fos-like immunoreactivity in the dorsal vagal complex but not in the myenteric plexus by CCK1 receptor in the adult rat. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;292:R1071–R1080. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00490.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T, Owyang C. Mechanism of cholecystokinin-induced relaxation of the rat stomach. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1999;75:123–130. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1838(98)00181-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thanos PK, Subrize M, Delis F, Cooney RN, Culnan D, Sun M, Wang GJ, Volkow ND, Hajnal A. Gastric bypass increases ethanol and water consumption in diet-induced obese rats. Obes Surg. 2012;22:1884–1892. doi: 10.1007/s11695-012-0749-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolstykh G, Belugin S, Mifflin S. Responses to GABAA receptor activation are altered in NTS neurons isolated from chronic hypoxic rats. Brain Res. 2004;1006:107–113. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.01.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travagli RA, Gillis RA. Hyperpolarization-activated currents Ih and IKIR in rat dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus neurons, in vitro. J Neurophysiol. 1994;71:1308–1317. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.71.4.1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travagli RA, Gillis RA, Rossiter CD, Vicini S. Glutamate and GABA-mediated synaptic currents in neurons of the rat dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 1991;260:G531–G536. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1991.260.3.G531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travagli RA, Hermann GE, Browning KN, Rogers RC. Brainstem circuits regulating gastric function. Annu Rev Physiol. 2006;68:279–305. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.68.040504.094635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valenzuela IM, Browning KN, Travagli RA. Morphological differences between planes of section do not influence the electrophysiological properties of identified rat dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus neurons. Brain Res. 2004;1003:54–60. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.10.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Wall EH, Duffy P, Ritter RC. CCK enhances response to gastric distension by acting on capsaicin-insensitive vagal afferents. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;289:R695–R703. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00809.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan S, Coleman FH, Travagli RA. Cholecystokinin-8s excites identified rat pancreatic-projecting vagal motoneurons. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007a;293:G484–G492. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00116.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan S, Coleman FH, Travagli RA. Glucagon-like peptide-1 excites pancreas-projecting preganglionic vagal motoneurons. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007b;292:G1474–G1482. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00562.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]