Abstract

Biomaterials designed to mimic the intricate native extracellular matrix (ECM) can use a variety of techniques to control the behavior of encapsulated cells. Common methods include controlling the mechanical properties of the material, incorporating bioactive signals, spatially patterning bioactive signals, and controlling the time-release of bioactive signals. Further design parameters like bioactive signal distribution can be used to manipulate cell behavior. Efforts on clustering adhesion peptides have focused on seeding cells on top of a biomaterial. Here we report the effect of clustering the adhesion peptide RGD on mouse mesenchymal stem cells encapsulated inside three-dimensional hyaluronic acid hydrogels. The clustered bioactive signals resulted in significant differences in both cell spreading and integrin expression. These results indicate that signal RGD peptide clustering is an additional hydrogel design parameter can be used to influence and guide the behavior of encapsulated cells.

Keywords: Hydrogel, Hyaluronic acid, RGD clustering, Mesenchymal stem cells

1. Introduction

The microenvironment plays a crucial role in normal development by guiding stem-cell fate and tissue organization [1–9], but also contributes to pathological processes such as tumor progression and metastasis [1,3,4,10–19]. To be able to design materials that can be used to study stem cell fate decisions or as scaffolds for regenerative medicine, there needs to be a better understanding of how bioactive signal incorporation affects the embedded cells. For example, although vascular endothelial growth factor-165 (VEGF) has been routinely covalently immobilized to hydrogel scaffolds to enhance angiogenesis [20–23], the molecular consequences of this immobilization are not completely understood. We recently found that covalently bound VEGF is able to phosphorylate VEGFR-2 to the same extent as soluble VEGF in endothelial cells (EC), but that the mode of VEGF presentation alters the tyrosine residues that are phosphorylated, the time course of phosphorylation, and the resulting downstream signaling [24]. In this report, we studied how the presentation (clustered or homogenous) of the fibronectin derived peptide sequence, RGD, affected mesenchymal stem cell proliferation, spreading and integrin expression.

Hydrogels are a class of biomaterial scaffolds that exist as highly hydrated, cross-linked networks [25–27]. Their chemical and physical properties can be adjusted to create microenvironments suitable for cell proliferation and differentiation. Hydrogels can be constructed from natural materials like hyaluronic acid [28], collagen [29], fibrin [30], chitosan [31], and alginate [32]. Researchers have also used synthetic materials like poly(ethylene glycol) [33], and poly(vinyl alcohol) [34] to construct tissue engineering scaffolds. With a number of advantages and disadvantages to each type of material, the application can help choose the hydrogel system used by the researcher. Regardless of the system chosen, bioactive molecules must be incorporated into the hydrogel matrix to help direct cell behavior [35,36]. These molecules can consist of full-length extracellular matrix proteins like fibronectin, and laminin or small peptide sequences derived from these proteins like RGD, IKVAV and YIGSR [37–41].

Integrin binding connects the extracellular matrix to the cells and initiates signaling events that control cell behavior [42–45] and remodel the matrix [46,47]. Two-dimensional studies in hydrogel scaffolds have shown that RGD presentation at the nanoscale level influences cell spreading and motility [48–51], stem cell differentiation [52] and nanoparticle internalization [53], however, for cells seeded within the hydrogel scaffolds, only RGD total content has been shown to modulate cell motility, spreading and proliferation [28,54,55].

Herein we report on the effect of varying RGD presentation on mouse mesenchymal stem cell spreading, proliferation, and integrin expression for cells cultured inside matrix metalloproteinase degradable hyaluronic acid hydrogels. Hyaluronic acid is a nonsulfated glycosaminoglycan that exists in connective, epithelial, and neural tissue [56,57]. Its high biocompatibility and low immunogenicity highlight its potential as a biomaterial. We have previously shown that altering hyaluronic acid (HA) hydrogel parameters (HA weight%, crosslinker type, crosslinking ratio, RGD concentration) greatly affects encapsulated cell behavior [28]. The same hyaluronic acid hydrogel system was used, with the RGD clustering controlled by pre-reacting specific portions of the HA with the bioactive signal (Fig. 1). Mouse mesenchymal stem cells were encapsulated inside these hydrogels. These cells are multipotent and have shown the ability to differentiate into adipocytes, chondrocytes, and osteoblasts [58–61].

Fig. 1.

The hydrogel is composed of acrylated hyaluronic acid, MMP-degradable peptide crosslinker, and an RGD-motif containing peptide. RGD clustering is controlled by the amount of HA-AC pre-reacted with RGD. In the homogenous, or least clustered condition, the RGD is mixed with all of the HA-AC. The RGD is pre-reacted with specific percentages of the total HA-AC to create different degrees of clustering. This RGD functionalized HA-AC is mixed with un-functionalized HA-AC, if needed, peptide crosslinker and mouse mesenchymal stem cells to create the three-dimensional hydrogel.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cells

Mouse mesenchymal stem cells (D1, CRL12424) were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA) and cultured in Dulbecco’s modified eagle’s medium (DMEM, Sigma–Aldrich) with 10% bovine growth serum (BGS, Hyclone, Logan, UT) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY). They were cultured at 37 °C with 5% CO2 using standard protocols.

2.2. Hyaluronic acid modification

Hyaluronic acid was functionalized with an acrylate group using a two-step synthesis as previously described [28]. HA (60,000 Da, Genzyme Corporation, Cambridge, MA) (2.0 g, 5.28 mmol) was dissolved in water and reacted with adipic dihydrazide (ADH, 18.0 g, 105.5 mmol) with 1-ethyl-3-(dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC, 4.0 g, 20 mmol) at a pH of 4.75 overnight. The solution was purified via dialysis (8000 MWCO) in deionized water for 2 days. The hydrazide-modified hyaluronic acid (HA-ADH) was lyophilized and stored at −20 °C. HA-ADH (1.9 g) was re-suspended in 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazine ethanesulfonic acid (HEPES) buffer (10 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM EDTA, pH 7.4) and reacted with N-acryloxysuccinimide (NHS-AC, 1.33 g, 4.4 mmol) overnight. After dialysis purification against deionized water for 2 days, the acrylated hyaluronic acid (HA-AC) was lyophilized. The product was analyzed with 1H NMR (D20) and the degree of acrylation (16%) determined by dividing the multiplet peak at δ = 6.2 (cis and trans acrylate hydrogens) by the singlet peak at δ = 1.6 (singlet peak of acetyl methyl protons in HA).

2.3. Gelation

Lyophilized acrylated hyaluronic acid was dissolved in 0.3 M triethanolamine (TEOA) for 20 min at 37 °C. Ac-GCGYGRGDSPG-NH2 adhesion peptide (RGD, Genscript, Piscataway, NJ) dissolved in 0.3 M TEOA was added to the appropriate amount of HA-AC and allowed to react for 20 min at 37 °C (Table 1). For example, in condition A3, 10 μm of RGD was added to 21% of the total HA-AC required whereas condition A5 required the RGD to be reacted to only 1.4% of the total HA-AC. Full culture DMEM, mMSC’s (5000 cells/μL final concentration), and the required amount of non-RGD functionalized HA-AC were then added. An aliquot of an MMP-degradable peptide crosslinker (Ac-GCRDGPQGIWGQDRCG-NH2, Genscript, Piscataway, NJ) was dissolved in 0.3 m TEOA and added to the gel precursor solution. 10 μL s of this solution was pipetted onto, and sandwiched between two Sigmacote (Sigma–Aldrich) functionalized glass coverslips and placed in an incubator for 30 min at 37 °C to gel. The degree of RGD clustering seen in Table 1 was calculated by dividing the moles of RGD used by the moles of HA that were reacted with the adhesion peptide.

Table 1.

Hydrogel formulations tested contain 10, 100, or 1000 μm of RGD. Five different RGD distributions, from homogenous to increasing levels of clustering, were tested for each concentration. This distribution was controlled by functionalizing specific percentages of HA with the RGD peptide.

| Hydrogel ID | A1 | A2 | A3 | A4 | A5 | B1 | B2 | B3 | B4 | B5 | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total RGD (μm) | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 |

| % HA reacted w/RGD | 100 | 42 | 21 | 4.2 | 1.4 | 100 | 42 | 21 | 4.2 | 1.4 | 100 | 42 | 21 | 4.2 | 1.4 |

| RGD clustering (mmol RGD/mmol HA-RGD) |

0.025 | 0.058 | 0.12 | 0.59 | 1.8 | 0.25 | 0.58 | 1.2 | 5.9 | 18 | 2.5 | 5.8 | 12 | 59 | 180 |

2.4. Rheology

Gels without cells were made as described above and cut to size using an 8.0 mm biopsy punch. The modulus was measured with a plate-to-plate rheometer (Physica MCR 301, Anton Paar, Ashland, VA) using an 8 mm plate with a frequency range of 0.1–10 rad/s under a constant strain of 1% at 37 °C. An evaporation blocker system was used to keep the hydrogel from dehydrating during the test. For hydrogel degradation time course studies, gel A5 was made with cells and the modulus was measured at days 1, 4, and 7 after gelation.

2.5. Fixing/imaging

Gels were rinsed in 1× PBS and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature. Following a rinse in 1× PBS, the gels were incubated in 0.1% Triton X-100 to permeate the cell membranes. Another 1× PBS rinse was followed by a 90 min incubation in rhodamine phalloidin (Invitrogen) diluted 1:40 in a 1% BSA solution at room temperature in the dark. The gels were washed 3 times with 0.05% Tween-20 for 5 min prior to imaging with an inverted fluorescence microscope (Zeiss Axio Observer). 40 Z-stack slices were taken of each gel and the maximum intensity projection was taken following deconvolution image processing. Cell spreading was quantified by measuring the length of the longest cell dimension using the Axiovision software.

2.6. Cell proliferation

Cell proliferation was measured using the CyQUANT cell proliferation assay kit (Invitrogen). Gels were washed twice in 1× PBS and frozen in a −80 freezer at days 1, 4, 7, and 10 after hydrogel gelation. After thawing the gels at room temperature, they were degraded by incubation in 1000 U/mL of collagenase I (Worthington, Lakewood, NJ) at 37 °C for 15 min. The cells were isolated by centrifuging the solution at 500 rcf × 5 min and re-suspended in 200 μL of the CyQUANT GR dye/cell-lysis buffer. After 5 min incubation, the fluorescence was read using a plate reader at 480 nm.

2.7. Flow cytometry

Gels at day 4 after gelation were rinsed in 1 × PBS and degraded by incubation in 1000 U/mL of collagenase I at 37 °C for 15 min. The solution was spun at 500 rcf for 10 min and re-suspended in 1% BSA for 15 min to block nonspecific binding of antibodies. Each sample was incubated with one PE and one FITC-conjugated antibody for 30 min at a 1:40 dilution in 1% BSA on ice. The solution was centrifuged at 500 rcf for 10 min and re-suspended in 1% paraformaldehye for FACS. Analysis was performed using a FACScan X and the data was analyzed using FLOWJO. Triplicates were done for each condition with 3000 events/sample. The data was gated such that the negative control had 5% positive events.

2.8. Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using InStat (GraphPad, San Diego, CA). Data was analyzed using one way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test with a TukeyeKramer post-test and a 95% confidence interval.

3. Results

3.1. Hydrogel synthesis and characterization

Hydrogel scaffolds were synthesized to contain different amounts of RGD (A = 10 μm, B = 100 μm and C = 1000 μm) and different distributions from homogenous (1) to increasing degrees of clustering (2–5). Thus, gel A5 contains RGD that is more clustered than A3 and C3 has more RGD total content than A3 or B3. Table 1 details the hydrogel synthesis conditions and RGD content. Because the amount and distribution of RGD is changing within each hydrogel condition, we wanted to ensure that the mechanical properties of the gels were the same between conditions. Similar mechanical properties would ensure that any differences observed between gels A1–5, B1–B5, or C1–C5 were due to RGD presentation and not mechanical differences. Gels 1, 3, and 5 for each RGD concentration were made and the storage modulus measured using a plate-to-plate rheometer (Fig. 2A–B) with a constant strain of 1% between frequencies 0.1 and 10 Hz. Storage moduli between each concentration were not found to be statistically different (p > 0.05, Fig. 2B). However, increasing the amounts of RGD from 10 to 100 and 1000 μM did reduce the average storage modulus for those gels. Therefore, comparisons are not made between different RGD concentrations and only between different RGD presentations.

Fig. 2.

Mechanical characterization of hydrogel conditions. (A) Storage modulus of hydrogels was measured from 0.1 to 10 Hz. Three conditions from each RGD concentration were tested. (B) Mechanical properties within each RGD concentration were consistent, but increasing amounts of RGD lowered the storage modulus.

3.2. Cell spreading

The effect of RGD clustering on mMSC spreading was studied at three concentrations and five different presentations as described in Table 1. At days 1, 4, and 7 the cells were fixed and filamentous actin was stained with phalloidin. For gels containing 10 μm of RGD, increasing signal clustering resulted in a higher degree of cell spreading. The homogenous condition, A1, had an average cell length of 15.16 ± 1.75 μm and was found to be statistically lower than the other 10 μm RGD conditions (p < 0.001). Gels A2-A4 had average cell lengths of 31.49 ± 8.66, 27.33 ± 5.44, and 36.50 ± 5.74 μm, respectively. Gel A3 was found to be statistically lower than A4 (p < 0.001). Gel A5 had the most spreading with cells averaging a length of 70.19 ± 14.49 μm. This condition was found to be statistically greater than gels A1–A4 (p < 0.001).

For gels with an RGD concentration of 100 μm, the measured cell lengths of B1-5 were 42.69 ± 10.22, 48.55 ± 10.02, 64.27 ± 13.23, 37.69 ± 9.52, and 32.18 ± 9.14, respectively. B3 was found to be statistically greater than the other 4 conditions (p < 0.001). In addition, condition B2 was statistically different from B4 (p < 0.05) and B5 (p < 0.001).

Gels C1-5 containing 1000 μm of RGD had cell lengths of 31.98 ± 9.74, 41.21 ± 12.61, 73.66 ± 11.28, 38.45 ± 12.27, and 41.92 ± 17.47, respectively. Gel C3 was found to be statistically higher than the other 4 conditions (p < 0.001) within this RGD concentration.

Cell spreading between A1–5, B1–5, and C1–5 can be compared through their degree of RGD clustering (RGD/HA molecule, Table 1). Gels A5, B3, and C3 had the highest degree of spreading for each RGD concentration, which corresponded to 1.8, 1.2 and 12 RGDs/HA molecule.

3.3. Proliferation

Proliferation within gels was measured by quantifying DNA content with a CyQUANT proliferation kit. Gels from each condition were washed twice with PBS and frozen at −80 °C at days 1, 4, and 7. After thawing the gels, collagenase I was used to degrade the MMP-sensitive peptide used to crosslink the gels. Cells were isolated from the solution via centrifugation and lysed. For gels A1–A5 (RGD 10 μm, Fig. 3C) the DNA content rose each day except for day 10. No statistical difference between the conditions was found at each time point. DNA content rose in gels B1-B5 (RGD 100 μm, Fig. 4C) at each time point and there was no statistical difference between the conditions. Gels C1–C5 (RGD 1000 μm, Fig. 5C) had DNA content rise between each time point until day 10. No statistical difference between each condition was found at each time point.

Fig. 3.

Cell spreading and proliferation for 10 μm hydrogels. (A) mMSC’s within hydrogels containing 10 μm of RGD were stained with phalloidin at different time points. The most pronounced differences in spreading were observed at day 4. (B) The average cell length was quantified with the greatest spreading seen in the most clustered condition. (C) DNA quantification shows no significant difference between conditions at each time point.

Fig. 4.

Cell spreading and proliferation for 100 μm hydrogels. (A) mMSC’s cells within hydrogels containing 10 μm of RGD were stained with phalloidin at different time points. The most pronounced differences in spreading were observed at day 4. (B) The average cell length was quantified with the greatest spreading seen in the middle, B3, condition. (C) DNA quantification shows no significant difference between conditions at each time point.

Fig. 5.

Cell spreading and proliferation for 1000 μm hydrogels. (A) mMSC’s cells within hydrogels containing 1000 μm of RGD were stained with phalloidin at different time points. The most pronounced differences in spreading were observed at day 4. (B) The average cell length was quantified with the greatest spreading seen in the middle, C3, condition. (C) DNA quantification shows no significant difference between conditions at each time point.

3.4. Integrin expression

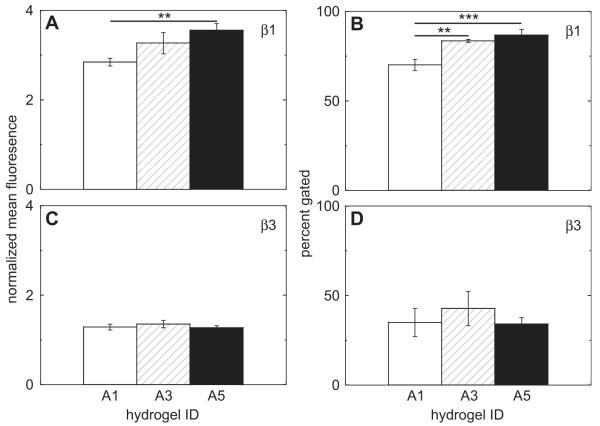

To see if changes in spreading due to RGD presentation altered integrin expression, cells were collected from gels A1, A3, and A5 at day 4. These conditions were shown to have significantly different amounts of cell spreading at this time point (Fig. 3B). We found that the RGD presentation did affect the expression of cell integrins (Fig. 6 and Fig. 7). Specifically, the hydrogel properties induced different expression levels in α2, α3, and β1. The amount of cells that positively expressed α2 was significantly higher in A1 when compared to A3 (p < 0.001) and A5 (p < 0.001, Fig. 6B). Differences in α3 normalized mean fluorescence values were observed between A1–A3 (p < 0.001) and A1–A5 (p < 0.001, Fig. 6C). In addition, the percentage of α3 positively expressing cells was significantly lower in A1, when compared to A3 (p < 0.001) and A5 (p < 0.001, Fig. 6D). RGD presentation also stimulated differences in β1 mean fluorescence levels between condition A1 and A5 (p < 0.01, Fig. 7A). The number of β1 expressing cells also increased from gel A1 to A3 (p < 0.01) and A5 (p < 0.001, Fig. 7B). RGD presentation did not significantly affect the integrin expression levels of α5 (Fig. 6E, F), αV (Fig. 6G, H), and β3 (Fig. 7C, D).

Fig. 6.

Integrin expression for subunits (A–B) α2, (C–D) α3, (E–F) α5, (G–H) αV was quantified for mouse mesenchymal stem cells cultured in gel conditions A1, A3, and A5 via FACS. Differences were found in the normalized mean expression for α3. Gel conditions also affected the number of cells positively expressing integrins α2 and α3.

Fig. 7.

Integrin expression for subunits (A–B) β1 and (C–D) β3 for mouse mesenchymal stem cells cultured in gel conditions A1, A3, and A5 via FACS. Differences were observed in both the normalized mean fluorescence and percent of positively expressing cells for subunit β1.

3.5. Time course of MSC marker

The MSC marker CD105 was used to determine whether the RGD clustering played a role in differentiating the mMSC’s encapsulated in the gels. Cells from a flask were used as a “day 0” time point. Gels from A1, A3, and A5 were degraded at days 1, 4, and 7 and cells collected. The CD105 expression decreased with time with 87% of the cells expressing the marker at day 0 and only 17.3,17.2 or 7.6 expressing the marker for A1, A3 and A5 conditions respectively. There were no statistical significant differences between conditions (p > 0.05).

3.6. Time course of gel degradation

The time course of gel degradation was investigated by encapsulating cells in A5 and measuring the storage modulus at days 1, 4, and 7 after gelation (Fig. 8C–D). The modulus decreased at each time point as the protease’s released by the cells broke down the structure of the hydrogel.

Fig. 8.

Time course of CD105 expression for mouse mesenchymal stem cells cultured inside hydrogels A1, A3, and A5 shows decreases across all three conditions for both the (A) normalized mean fluorescence and (B) the percent gated. (C–D) mechanical properties of hydrogel A5 was measured at days 1, 4, and 7. The storage modulus decreases over time as the cells release MMP’s which breakdown the hydrogel structure.

4. Discussion

Stem cells hold great promise due to their pluripotency [62–64]. Their fate is influenced by interactions with soluble factors, physical signals, other cells, and extracellular matrix mechanics. The effect of these factors on stem cell behavior must be studied and understood to unlock these cell’s full potential. While there have been studies on the effect of mechanical properties on cell behavior, there has been less emphasis on the effect of bioactive signal presentation. Studies in 2-dimensional environments have shown the importance of signal clustering on cell behavior [50,51]. Here we study the effect of RGD peptide distribution on mouse mesenchymal stem cell behavior in a three-dimensional hyaluronic acid hydrogel.

RGD is a well-characterized peptide adhesion fragment derived from fibronectin that facilitates binding through the α5β1 integrin complex [38]. RGD peptide distribution in the hydrogel was controlled by pre-reacting it with specific percentages of the total acrylate modified hyaluronic acid (HA-AC, Table 1). To characterize the differences between each condition, the degree of RGD clustering was calculated. This is defined by the moles of RGD per mole of HA reacted with RGD or number of RGD per HA molecule (Table 1).

Before studying the effect of clustering on cell behavior, rheology was performed on all gel conditions. The storage modulus was found to be constant among each given RGD concentration (Fig. 2A–B). However, there were statistical differences when comparing gels with different amounts of RGD. This data allows us to directly compare gels with the same RGD concentration but not between different concentrations. Differences observed can be attributed to RGD presentation and not bulk mechanics of the hydrogel.

To investigate the time course of cell spreading, samples were fixed at days 1, 4, 7, and 10 after gelation and filamentous actin stained (Figs. 3A, 4A and 5A). The largest difference in cell spreading was observed at day 4 and was quantified for further analysis. For gels with 10 μm of RGD, the most spreading was observed in the most clustered sample (A5), which had 1.8 mmol of RGD/mmol HA-RGD (Fig. 3B). However, the most cell spreading in gels with 100 μm RGD occurred in the middle condition (B3, Fig. 4B). This condition had 1.2 mmol of RGD/mmol HA-RGD, which may indicate an optimal “degree of RGD clustering” for cell spreading in our hyaluronic acid hydrogels. The final RGD concentration tested, 1000 μm, had the highest degree of cell spreading in the middle condition (C3, Fig. 5B), which had 12 mmol of RGD/mmol HA-RGD. If the optimal “degree of RGD clustering” is near the clustering seen in gel conditions A5 and B3, gel condition C1 would be expected to produce more spreading than C3. A possible explanation for this discrepancy is that the sheer amount of RGD encountered by cells in conditions C1–C5 outweighs the effects of RGD clustering. Studies of cells seeded on top of patterned materials have also shown that bioactive signal distribution affects behavior [48–51]. After day 4, differences in cell spreading became less pronounced.

Cell spreading observations prompted us to investigate integrin expression to see if the clustering was affecting the cell surface receptors. We chose to look at gels A1, A3, and A5 at day 4 since these conditions had the biggest difference in cell spreading. We analyzed integrins that are known to be expressed in MSCs: α2, α3, α5, αV, β1, and β3 [45,65]. Differences in expression were found in multiple integrins. The percentage of cells positively expressing the α2 integrin was significantly higher in condition A1 than A3 and A5 (Fig. 6B). Both the percentage of cells expressing α3 and the degree of expression were significantly lower in A1 than A3 and A5 (Fig. 6C–D). One of the beta subunits, β1, also had different expression levels between conditions. There was a difference between the mean fluorescence levels in sample A1 vs. A5. The percentage of positively expressing cells was also lower in A1 when compared to A3 and A5 (Fig. 7A–B). Since integrin expression affects the signaling pathways that influence cell behavior and differentiation, we also tracked the expression time course of the mesenchymal stem cell marker, CD105, in gels A1, A3, and A5 (Fig. 8A–B). mMSC’s taken from a tissue culture flask were used as a day 0 time point. Over the course of 7 days, CD105 dropped dramatically between all conditions. It was interesting to see that even though we had differences in spreading and integrin expression at day 4, there were not any differences in CD105 expression between conditions throughout the 7 day experiment.

Matrix mechanical properties have been shown to play a key role in determing cell fate [35,66]. Because of this, the time course of gel degradation was studied. Since our hydrogel is cross-linked with an MMP-degradable peptide sequence and the backbone is degradable by secreted hyaluronidases, the storage modulus decreases over time as the encapsulated mesenchymal stem cells release MMPs or hyaluronidases (Fig. 8C–D). This decrease in matrix stiffness could help explain why the RGD clustering is not able to control cell differentiation in our system. Because the hydrogel degrades, the differences due to bioactive signal clustering we observed in cell spreading and integrin expression at day 4 were not enough to influence changes in CD105 expression between conditions. The expression change seen is due to a combination of RGD clustering and mechanical changes, with mechanical signals weighing in more than bioactive signals [67]. To tease out the isolated role of bioactive signal clustering, we would need a system that keeps mechanical properties constant.

5. Conclusion

In this study, we investigated the effect of RGD bioactive signal clustering on the behavior of MSCs cultured in a three-dimensional hyaluronic acid hydrogel. Cell spreading and integrin expression were found to be affected by RGD clustering. The highest degree of spreading was found in the most clustered condition for the 10 μm RGD hydrogels (A5) but in the middle clustered condition for the 100 μm RGD hydrogels (B3). These results comparing different RGD concentrations with similar degrees of clustering may indicate a concentration independent “optimal clustering” parameter for cell spreading. Furthermore, expression of integrins α2, α3, and β1 were affected by signal clustering. While our system was able to reduce the level of an MSC marker in the cells studied, it was not able to isolate the effect of the signal clustering from mechanical properties over the course of 7 days. Our results show that bioactive signal clustering has an effect on cells in three-dimension and is a biomaterial design parameter that can be manipulated to help control cell behavior.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine (CIRM RT2-01881) for funding. J.L. would also like to thank the NIH Funded Biotechnology Training Grant (T32 GM067555) for a predoctoral fellowship. Anandika Dhaliwal is thanked for help with the FACS experiments.

References

- [1].Weigelt B, Bissell MJ. Unraveling the microenvironmental influences on the normal mammary gland and breast cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2008;18:311–21. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2008.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].LaBarge MA, Petersen OW, Bissell MJ. Of microenvironments and mammary stem cells. Stem Cell Rev. 2007;3:137–46. doi: 10.1007/s12015-007-0024-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Nelson CM, Bissell MJ. Of extracellular matrix, scaffolds, and signaling: tissue architecture regulates development, homeostasis, and cancer. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2006;22:287–309. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.22.010305.104315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Hagios C, Lochter A, Bissell MJ. Tissue architecture: the ultimate regulator of epithelial function? Philos Trans R Soc Lond Ser B-Biol Sci. 1998;353:857–70. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1998.0250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Boudreau N, Bissell MJ. Extracellular matrix signaling: integration of form and function in normal and malignant cells. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1998;10:640–6. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(98)80040-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Bissell MJ, Hall HG, Parry G. How does the extracellular-matrix direct gene-expression. J Theor Biol. 1982;99:31–68. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(82)90388-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Cosgrove BD, Sacco A, Gilbert PM, Blau HM. A home away from home: challenges and opportunities in engineering in vitro muscle satellite cell niches. Differentiation. 2009;78:185–94. doi: 10.1016/j.diff.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Lutolf MP, Blau HM. Artificial stem cell niches. Adv Mater. 2009;21:3255–68. doi: 10.1002/adma.200802582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Lutolf MP, Doyonnas R, Havenstrite K, Koleckar K, Blau HM. Perturbation of single hematopoietic stem cell fates in artificial niches. Integr Biol. 2009;1:59–69. doi: 10.1039/b815718a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Bissell MJ, Hines WC. Why don’t we get more cancer? A proposed role of the microenvironment in restraining cancer progression. Nat Med. 2011;17:320–9. doi: 10.1038/nm.2328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Bissell MJ, LaBarge MA. Context, tissue plasticity, and cancer: are tumor stem cells also regulated by the microenvironment? Cancer Cell. 2005;7:17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ghajar CM, Bissell MJ. Tumor engineering: the other face of tissue engineering. Tissue Eng Part A. 2010;16:2153–6. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2010.0135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Nelson CM, Bissell MJ. Modeling dynamic reciprocity: engineering three-dimensional culture models of breast architecture, function, and neoplastic transformation. Semin Cancer Biol. 2005;15:342–52. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Park CC, Bissell MJ, Barcellos-Hoff MH. The influence of the microenvironment on the malignant phenotype. Mol Med Today. 2000;6:324–9. doi: 10.1016/s1357-4310(00)01756-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Petersen OW, Nielsen HL, Gudjonsson T, Villadsen R, Ronnov-Jessen L, Bissell MJ. The plasticity of human breast carcinoma cells is more than epithelial to mesenchymal conversion. Breast Cancer Res. 2001;3:213–7. doi: 10.1186/bcr298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Radisky D, Hagios C, Bissell MJ. Tumors are unique organs defined by abnormal signaling and context. Semin Cancer Biol. 2001;11:87–95. doi: 10.1006/scbi.2000.0360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Ronnov-Jessen L, Bissell MJ. Breast cancer by proxy: can the microenvironment be both the cause and consequence? Trends Mol Med. 2009;15:5–13. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Turley EA, Veiseh M, Radisky DC, Bissell MJ. Mechanisms of disease: epithelial-mesenchymal transition - does cellular plasticity fuel neoplastic progression? Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2008;5:280–90. doi: 10.1038/ncponc1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Xu R, Boudreau A, Bissell M. Tissue architecture and function: dynamic reciprocity via extra- and intra-cellular matrices. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2009;28:167–76. doi: 10.1007/s10555-008-9178-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Moon JJ, Saik JE, Poche RA, Leslie-Barbick JE, Lee SH, Smith AA, et al. Biomimetic hydrogels with pro-angiogenic properties. Biomaterials. 2010;31:3840–7. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.01.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Phelps EA, Landazuri N, Thule PM, Taylor WR, Garcia AJ. Bioartificial matrices for therapeutic vascularization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 107:3323–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905447107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Zisch AH, Lutolf MP, Ehrbar M, Raeber GP, Rizzi SC, Davies N, et al. Cell-demanded release of VEGF from synthetic, biointeractive cell ingrowth matrices for vascularized tissue growth. Faseb J. 2003;17:2260–2. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-1041fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Zisch AH, Schenk U, Schense JC, Sakiyama-Elbert SE, Hubbell JA. Covalently conjugated VEGFefibrin matrices for endothelialization. J Control Release. 2001;72:101–13. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(01)00266-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Anderson SM, Shergill B, Barry ZT, Manousiouthakis E, Chen TT, Botvinick E, et al. VEGF internalization is not required for VEGFR-2 phosphorylation in bioengineered surfaces with covalently linked VEGF. Integr Biol (Camb) 2011;3:887–96. doi: 10.1039/c1ib00037c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Peppas NA, Hilt JZ, Khademhosseini A, Langer R. Hydrogels in biology and medicine: from molecular principles to bionanotechnology. Adv Mater. 2006;18:1345–60. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Kopecek J, Yang JY. Review – hydrogels as smart biomaterials. Polym Int. 2007;56:1078–98. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Tibbitt MW, Anseth KS. Hydrogels as extracellular matrix mimics for 3D cell culture. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2009;103:655–63. doi: 10.1002/bit.22361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Lei YG, Gojgini S, Lam J, Segura T. The spreading, migration and proliferation of mouse mesenchymal stem cells cultured inside hyaluronic acid hydrogels. Biomaterials. 2011;32:39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.08.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Butcher JT, Nerem RM. Porcine aortic valve interstitial cells in three-dimensional culture: comparison of phenotype with aortic smooth muscle cells. J Heart Valve Dis. 2004;13:478–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Eyrich D, Brandl F, Appel B, Wiese H, Maier G, Wenzel M, et al. Long-term stable fibrin gels for cartilage engineering. Biomaterials. 2007;28:55–65. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Azab AK, Orkin B, Doviner V, Nissan A, Klein M, Srebnik M, et al. Crosslinked chitosan implants as potential degradable devices for brachytherapy: in vitro and in vivo analysis. J Control Release. 2006;111:281–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Barralet JE, Wang L, Lawson M, Triffitt JT, Cooper PR, Shelton RM. Comparison of bone marrow cell growth on 2D and 3D alginate hydrogels. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2005;16:515–9. doi: 10.1007/s10856-005-0526-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Adeloew C, Segura T, Hubbell JA, Frey P. The effect of enzymatically degradable poly(ethylene glycol) hydrogels on smooth muscle cell phenotype. Biomaterials. 2008;29:314–26. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Nuttelman CR, Henry SM, Anseth KS. Synthesis and characterization of photocrosslinkable, degradable poly(vinyl alcohol)-based tissue engineering scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2002;23:3617–26. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(02)00093-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Discher DE, Mooney DJ, Zandstra PW. Growth factors, matrices, and forces combine and control stem cells. Science. 2009;324:1673–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1171643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Lutolf MP, Gilbert PM, Blau HM. Designing materials to direct stem-cell fate. Nature. 2009;462:433–41. doi: 10.1038/nature08602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Hersel U, Dahmen C, Kessler H. RGD modified polymers: biomaterials for stimulated cell adhesion and beyond. Biomaterials. 2003;24:4385–415. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00343-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Ruoslahti E. RGD and other recognition sequences for integrins. Annu Rev Cell Dev Bi. 1996;12:697–715. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.12.1.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Kibbey MC, Jucker M, Weeks BS, Neve RL, Vannostrand WE, Kleinman HK. Beta-amyloid precursor protein binds to the neurite-promoting Ikvav site of laminin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:10150–3. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.21.10150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Nomizu M, Weeks BS, Weston CA, Kim WH, Kleinman HK, Yamada Y. Structure-activity study of a laminin alpha-1 chain active peptide segment Ile-Lys-Val-Ala-Val (Ikvav) Febs Lett. 1995;365:227–31. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00475-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Maeda T, Titani K, Sekiguchi K. Cell-adhesive activity and receptor-binding specificity of the laminin-derived Yigsr sequence grafted onto staphylococcal protein-A. J Biochem-Tokyo. 1994;115:182–9. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a124315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Giancotti FG, Ruoslahti E. Science. Vol. 285. New York, NY: 1999. Integrin signaling; pp. 1028–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Cukierman E, Pankov R, Stevens DR, Yamada KM. Science. Vol. 294. New York, NY: 2001. Taking cell-matrix adhesions to the third dimension; pp. 1708–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Jones JL, Walker RA. Integrins: a role as cell signalling molecules. J Clin Pathol Mol Pa. 1999;52:208–13. doi: 10.1136/mp.52.4.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Prowse ABJ, Chong F, Gray PP, Munro TP. Stem cell integrins: Implications for ex-vivo culture and cellular therapies. Stem Cell Res. 2011;6:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2010.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Davis GE, Senger DR. Endothelial extracellular matrix – biosynthesis, remodeling, and functions during vascular morphogenesis and neovessel stabilization. Circ Res. 2005;97:1093–107. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000191547.64391.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Hood JD, Cheresh DA. Role of integrins in cell invasion and migration. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:91. doi: 10.1038/nrc727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Comisar WA, Kazmers NH, Mooney DJ, Linderman JJ. Engineering RGD nanopatterned hydrogels to control preosteoblast behavior: a combined computational and experimental approach. Biomaterials. 2007;28:4409–17. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Comisar WA, Mooney DJ, Linderman JJ. Integrin organization: linking adhesion ligand nanopatterns with altered cell responses. J Theor Biol. 2011;274:120–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2011.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Maheshwari G, Brown G, Lauffenburger DA, Wells A, Griffith LG. Cell adhesion and motility depend on nanoscale RGD clustering. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:1677–86. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.10.1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Koo LY, Irvine DJ, Mayes AM, Lauffenburger DA, Griffith LG. Co-regulation of cell adhesion by nanoscale RGD organization and mechanical stimulus. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:1423–33. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.7.1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Lee KY, Alsberg E, Hsiong S, Comisar W, Linderman J, Ziff R, et al. Nanoscale adhesion ligand organization regulates osteoblast proliferation and differentiation. Nano Lett. 2004;4:1501–6. doi: 10.1021/nl0493592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Kong HJ, Hsiong S, Mooney DJ. Nanoscale cell adhesion ligand presentation regulates nonviral gene delivery and expression. Nano Lett. 2007;7:161–6. doi: 10.1021/nl062485g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Alsberg E, Anderson KW, Albeiruti A, Franceschi RT, Mooney DJ. Cell-interactive alginate hydrogels for bone tissue engineering. J Dental Res. 2001;80:2025–9. doi: 10.1177/00220345010800111501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Lutolf MP, Lauer-Fields JL, Schmoekel HG, Metters AT, Weber FE, Fields GB, et al. Synthetic matrix metalloproteinase-sensitive hydrogels for the conduction of tissue regeneration: engineering cell-invasion characteristics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:5413–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0737381100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Allison DD, Grande-Allen KJ. Review. Hyaluronan: a powerful tissue engineering tool. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:2131–40. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.2131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Fraser JRE, Laurent TC, Laurent UBG. Hyaluronan: its nature, distribution, functions and turnover. J Intern Med. 1997;242:27–33. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.1997.00170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Diduch DR, Coe MR, Joyner C, Owen ME, Balian G. 2 cell-lines from bone-marrow that differ in terms of collagen-synthesis, osteogenic characteristics, and matrix mineralization. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 1993;75A:92–105. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199301000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Li XD, Cui QJ, Kao CH, Wang GJ, Balian G. Lovastatin inhibits adipogenic and stimulates osteogenic differentiation by suppressing PPAR gamma 2 and increasing Cbfa1/Runx2 expression in bone marrow mesenchymal cell cultures. Bone. 2003;33:652–9. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(03)00239-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Li XD, Jin L, Cui QJ, Wang GJ, Balian G. Steroid effects on osteogenesis through mesenchymal cell gene expression. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16:101–8. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1649-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Devine MJ, Mierisch CM, Jang E, Anderson PC, Balian G. Transplanted bone marrow cells localize to fracture callus in a mouse model. J Orthop Res. 2002;20:1232–9. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(02)00051-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Weissman IL. Stem cells: units of development, units of regeneration, and units in evolution. Cell. 2000;100:157–68. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81692-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Donovan PJ, Gearhart J. The end of the beginning for pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2001;414:92–7. doi: 10.1038/35102154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Fuchs E, Segre JA. Stem cells: a new lease on life. Cell. 2000;100:143–55. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81691-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Minguell JJ, Erices A, Conget P. Mesenchymal stem cells. Exp Biol Med. 2001;226:507–20. doi: 10.1177/153537020122600603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Discher DE, Sweeney L, Sen S, Engler A. Matrix elasticity directs stem cell lineage specification. Biophysical J. 2007:32a–a. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Huebsch N, Arany PR, Mao AS, Shvartsman D, Ali OA, Bencherif SA, et al. Harnessing traction-mediated manipulation of the cell/matrix interface to control stem-cell fate. Nat Mater. 2010;9:518–26. doi: 10.1038/nmat2732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]