Introduction

Substance abuse and dependence persist as major health concerns in the United States. Alarmingly, 17% of Americans meet the diagnostic criteria for some form of substance dependence, excluding tobacco dependence (Anthony and Helzer, 1991), which is nearly twice the incidence of depression (9.5%; National Institute of Mental Health, 2000), and 17 times the incidence of schizophrenia (1%; National Institute of Mental Health, 2006). According to a recent report published by the Nation Institute on Drug Abuse, 36.8 million Americans have used cocaine at least once, 8.4 million have used crack cocaine, 3.8 million have used heroin, 555,000 have used ecstasy, 15.2 million have used marijuana and 70.9 million have smoked cigarettes (National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2008). In addition, substance abuse costs our nation an estimated $484 billion in annual expenses (diabetes and cancer impose costs of $132 billion and $172 billion, respectively) (National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2005). The severity of the problem is further compounded by the fact that addiction is a chronic, relapsing disease of the brain, instituting long-lasting changes in brain function that interact with numerous environmental factors (O'Brien, 1997). One such interaction involves the devaluation of natural rewards (e.g., food, sex, work, money, caring for one's offspring) by drugs of abuse (Goldstein et al., 2007; Jones et al., 1995; Nair et al., 1997; Santolaria-Fernandez et al., 1995; Wilson et al., 2008). Previously, we and others have shown that rats suppress intake of a palatable solution (e.g., saccharin) when that solution serves as a cue predicting access to a drug of abuse (Cappell and LeBlanc, 1971, 1977; Grigson and Twining, 2002; Grigson et al., 2000; Le Magnen, 1969). The data suggest that suppression of intake of the taste cue (referred to as the conditioned stimulus or CS) is due, in part, to comparison of the two disparate rewards and the resultant devaluation of the lesser valued saccharin reward cue (Grigson, 1997; Grigson, 2008).

While addiction is a devastating disease, there is reason for hope. Certain factors (e.g., exposure to sweets) have been shown to have protective influences on drug-taking and drug-seeking behaviors (Carroll and Lac, 1993; Higgins et al., 1993; Lenoir and Ahmed, 2007; Liu and Grigson, 2005) and much work has been done in the field of environmental enrichment. In fact, environmental enrichment has been shown to reduce the rewarding effects of cocaine, nicotine, and heroin (El Rawas et al., 2008; Green et al., 2003; Solinas et al., 2008a), reduce self-administration of amphetamine (Bardo et al., 2001; Green et al., 2002), enhance the extinction of amphetamine self-administration (Stairs et al., 2006), and attenuate reinstatement of drug seeking induced by drug, drug-associated cues, and stress (Chauvet et al., 2009; Stairs et al., 2006). In addition, environmental enrichment has been shown to cause several neuroanatomical and neurochemical changes in the reward circuitry of the brain (Bezard et al., 2003; Solinas et al., 2008b; Zhu et al., 2005), specifically in the mesocorticolimbic dopamine system, which responds to natural rewards, but may be subsequently hijacked by drugs of abuse (see Kelley and Berridge, 2002 for a review).

While extremely valuable, the aforementioned environmental enrichment studies did not lend themselves to the investigation of the impact of environmental enrichment on the acquisition of drug self-administration behavior or on the drug-induced devaluation of a natural reward. First, several of the studies described above began exposure to enrichment during adolescence, not during adulthood (Bardo et al., 2001; Bezard et al., 2003; El Rawas et al., 2008; Solinas et al., 2008a; Stairs et al., 2006). Second, many of the studies that were conducted in adult animals employed paradigms where drug was administered passively by the experimenter (e.g., conditioned place preference or sensitization), rather than self-administered (Bezard et al., 2003; El Rawas et al., 2008; Green et al., 2003; Solinas et al., 2008a). Third, when an active drug self-administration paradigm was used in adult rats, environmental enrichment did not begin until after the acquisition phase (Chauvet et al., 2009). Finally, no environmental enrichment studies have been conducted to determine whether environmental enrichment will reduce not only responding for drug, but avoidance (i.e., devaluation) of a drug-associated natural reward cue as well.

Thus, in the present study, we were interested in determining whether the protective effects of environmental enrichment discussed above could be extended to rats that were placed in enriched environments as adults and then trained in an active cocaine self-administration paradigm thereafter. In addition, in an effort to assess the effect of environmental enrichment on drug-induced devaluation of natural rewards, access to cocaine was signaled by the availability of an otherwise palatable saccharin cue (Grigson and Twining, 2002). We hypothesized that non-enriched rats in the saccharin-cocaine condition would readily self-administer cocaine and exhibit high levels of goal-directed behavior towards the cocaine-associated operandum. Housing in the enriched environment, on the other hand, was expected to prevent cocaine self-administration and to cause a reduction in goal-directed behavior. Finally, we hypothesized that non-enriched (singly housed) rats would avoid intake of the saccharin cue when it predicted imminent access to cocaine and that environmental enrichment would prevent that suppression (i.e., allow for normal intake of the natural reward cue).

Methods

Subjects

This study was conducted in three replications. The subjects were 116 (n=40 for Replication 1, n=40 for Replication 2, and n=36 for Replication 3) naïve, male Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River Laboratories, Raleigh, NC), approximately three months of age (300-400 g in weight) at the beginning of the experiment. Due to complications during surgery, 7 rats were eliminated from the study. An additional 16 rats were eliminated due to loss of catheter patency, leaving 93 rats for behavioral training and experimental testing (described below). The rats were maintained on a 12-h light-dark cycle, with lights on at 0700 h. They were allowed ad lib access to food (Harlan Teklad, Madison, WI) and water, except where otherwise noted.

Housing Conditions

All rats were received from the provider and immediately placed in quarantine, where they remained for a period of one week. After quarantine the rats were acclimated to the colony room for a period of one week. As is standard for our laboratory, during quarantine and acclimation, the rats were housed in groups of 5-6 in wire mesh cages (38.0 cm in length × 46.0 cm in width × 20.0 cm in height). Following the quarantine and acclimation periods, the rats were split into non-enriched environment (Non-EE; n=59) and enriched environment (EE; n=34) groups. Environmental enrichment consisted of two separate manipulations: group housing and introduction of novel objects. First, rats in the Non-EE group were housed individually in standard wire mesh cages (38.0 cm in length × 21.5 cm in width × 20.0 cm in height) throughout the study, while rats in the EE condition were housed in groups of four in large wire mesh cages (38.0 cm in length × 46.0 cm in width × 20.0 cm in height). Immediately following intrajugular catheter implantation surgery (i.e., nine days later), novel objects (e.g., balls, Polyethylene tubes, paper, etc.) were placed in the cages of the EE rats. These objects were changed daily for the duration of the experiment. Throughout all behavioral training and experimental testing, all rats (Non-EE and EE) were housed in the same colony room with temperature, humidity, and ventilation controlled automatically.

Catheter Construction and Implantation

Self-administration catheter

Intra-jugular catheters were custom-made in our laboratory as described by Twining et al. (2009).

Catheter implantation

Rats were anesthetized and catheters were implanted into the jugular vein, as described by Twining et al. (2009), nine days after being separated into Non-EE and EE groups (i.e., Non-EE rats were housed singly while EE rats were housed in groups of 4, and neither was exposed to novel objects). Following surgery, novel objects were placed in the cages of the EE rats and all rats were allowed at least two days to recover. General maintenance of catheter patency involved daily examination and flushing of catheters with heparinized saline (0.2 ml of 30 IU/ml heparin). Catheter patency was verified, as needed, using 0.2 ml of propofol (Diprivan 1%) administered intravenously.

Apparatus

Each rat was trained in one of twelve identical operant chambers (MED Associates, St. Albans, VT) described by Twining et al. (2009). Each chamber measures 30.5 cm in length × 24.0 cm in width × 29.0 cm in height, and is individually housed in a light- and sound-attenuated cubicle. The chambers consist of a clear Plexiglas top, front, and back wall. The side walls are made of aluminum. Grid floors consist of nineteen 4.8-mm stainless steel rods, spaced 1.6 cm apart (center to center). Each chamber is equipped with three retractable sipper spouts that enter through 1.3-cm diameter holes, spaced 16.4 cm apart (center to center). A stimulus light is located 6.0 cm above each tube. Each chamber also is equipped with a houselight (25 W), a tone generator (Sonalert Time Generator, 2900 Hz, Mallory, Indianapolis, IN), and a speaker for white noise (75 dB). Cocaine reinforcement is controlled by a lickometer circuit that monitors empty spout licking to operate a syringe pump (Model A, Razel Scientific Instruments, Stamford, CT). A coupling assembly attaches the syringe pump to the catheter assembly on the back of each rat and enters through a 5.0-cm diameter hole in the top of the chamber. This assembly consists of a metal spring attached to a metal spacer with Tygon tubing inserted down the center, protecting passage of the tubing from rat interference. The tubing is attached to a counterbalanced swivel assembly (Instech, Plymouth Meeting, PA) that, in turn, is attached to the syringe pump which operates at a rate of 3.33 rpm. Events in the chamber and collection of data are controlled on-line with a Pentium computer that uses programs written in the Medstate notation language (MED Associates).

Drug Preparation

Individual 20-ml syringes were prepared for each self-administration chamber prior to each daily session by diluting 2.0 ml of cocaine HCl stock solution (1.24 g cocaine HCl + 150 ml saline) with 18.0 ml of heparinized saline (0.1 ml 1000 IU heparin/60.0 ml saline) for a dose of 0.167 mg/infusion. This relatively low dose was chosen to allow for this initial assessment of the effects of environmental enrichment on the acquisition of cocaine self-administration over trials.

Data Collection

Habituation, self-administration training, and progressive ratio testing were conducted during the light phase of the light/dark cycle.

Habituation Procedure and Spout Training

After nine days of being housed in either the Non-EE condition or the EE condition with social partners only, followed by an additional three days with the addition of novel objects for the EE groups, rats were habituated to the operant chambers for 1 h/day for two days prior to the beginning of self-administration training. During this time, each rat was maintained on a water-deprivation regimen in which they received 1-h daily access to water in the operant chamber from the right spout during the habituation session and 25.0 ml of water in the home cage overnight. Thereafter, rats were returned to ad lib access to water for the duration of the study.

Self-Administration Training Procedure

Self-administration training began immediately following the 2-day habituation phase. See Figure 1 for a summary of behavioral training and experimental testing. Each rat was trained during daily 65-min sessions for 14 days. Specifically, rats were placed in the operant chambers in darkness. Immediately upon initiation of the 65-min session, the white noise was turned on, the left spout, containing 0.15% saccharin, advanced into the chamber, and the house light was illuminated. Rats were then given 5 minutes to freely consume the saccharin solution. Following the 5-minute saccharin access period, the left spout retracted and the empty center and empty right spouts advanced into the chamber. The cue light above the empty right spout was illuminated. Rats were then allowed to self-administer cocaine (Non-EE: n=46; EE: n=24) or saline (Non-EE: n=13; EE: n=10) for 60 minutes. The number of rats in the Non-EE cocaine condition was increased to better characterize the normal motivation to self-administer the 0.167 mg/infusion dose of cocaine. The right spout was termed the “active” spout, while the center spout was termed the “inactive” spout. A fixed ratio (FR) 10 schedule of reinforcement was implemented initially (Trials 1-10). During this time, completion of 10 licks on the “active” spout was followed by a single intravenous (i.v.) infusion of 0.167 mg cocaine or saline over six seconds. Drug or saline delivery was signaled by offset of the stimulus light, retraction of the “active” spout, and onset of the tone and houselight. The tone and houselight remained on for a 20-sec timeout period, during which time no drug was available. Responding on the “inactive” spout was without consequence throughout each session. During the final four days of training (Trials 11-14), the reinforcement schedule was increased to an FR20 to better dissociate active and inactive responding. Following each self-administration training session, the rats were returned to their home cages. Saccharin intake, infusion number (across trials and terminal), and the terminal latency to self-administer the first infusion were measured. Saccharin intake was analyzed across trials, as well as during terminal access (i.e., averaged from the final two days of FR training).

Figure 1.

Timeline of behavioral training and experimental testing. Days postnatal (PN) are indicated at the beginning of each manipulation.

Progressive Ratio Testing

In addition to fixed ratio training, a progressive ratio (PR) schedule of reinforcement was implemented to test the impact of environmental enrichment on the reinforcing efficacy of cocaine. Thus, following the final day of FR20 training, PR testing was conducted. During PR testing, rats were placed in the operant chambers with conditions identical to those of self-administration training (including the initial 5-minute saccharin access period), except the number of active responses required to receive each infusion progressively increased by a multiple of five for up to ten infusions (1, 1+5=6, 6+10=16, 16+15=31, 31+20=51, 51+25=76, 76+30=106, 106+35=141, 141+40=181, 181+45=226). Thereafter, the number of required responses increased by 50 for each successive infusion (226+50=276, 276+50=326, 326+50=376, etc.; Puhl et al., 2009). During this PR session, rats were allowed to self-administer cocaine (0.167 mg/infusion) until a period of 30 min elapsed without receipt of an infusion. Break point (the highest ratio completed) was measured.

Data Analysis

All data were analyzed with Statistica (StatSoft, Tulsa, OK) using mixed factorial and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests. Fisher LSD post hoc tests were conducted on significant ANOVAs, when appropriate, with α set at 0.05.

Results

Saline/Cocaine Self-Administration

Consistent with previous findings (Grigson and Twining, 2002; Puhl et al., 2009; Twining et al., 2009), two sub-populations of rats emerged during self-administration training: low drug-takers (Non-EE: n=34; EE: n=23) and high drug-takers (Non-EE: n=12; EE: n=1). Those groups were identified by calculating the mean number of cocaine infusions self-administered during the final two days of self-administration training (Trials 13-14 on the FR20 schedule of reinforcement) and then by determining the clearest group-division point among those means. In this case, all rats that had a mean greater than or equal to 9 infusions were defined as high drug-takers. Those that had a mean less than 9 infusions were defined as low drug-takers. The identification of such a small number of high drug-takers, relative to our previous findings in Non-EE rats, is likely due to the low dose of cocaine employed. Our previous studies used a 0.33 mg/infusion dose of cocaine which is twice that of the current study (Grigson and Twining, 2002; Puhl et al., 2009; Twining et al., 2009). Regardless, it is interesting to note that, compared to the Non-EE rats, of which 12 out of 46 were identified as high drug-takers (26%), only 1 out of 24 rats (4%) in the EE condition fell into the high drug-taking group. Given that there was only one high drug-taking rat in the EE condition, the data from that rat are displayed in the remainder of the figures, but were excluded from the statistical analyses.

Cocaine intake across trials

Given the individual differences in cocaine self-administration, and our experience with such individual differences (Grigson and Twining, 2002; Puhl et al., 2009; Twining et al., 2009), intake of cocaine was analyzed accordingly. Thus, the number of cocaine infusions self-administered across trials by Non-EE rats was analyzed using a 3 × 14 mixed factorial ANOVA varying group (saline, low drug-takers, or high drug-takers) and trials (1-14; see the left panel of Figure 2a). A significant main effect of group was found, F(2, 56)=15.06, p < 0.01. Post hoc tests indicated that, overall, Non-EE high drug-takers in the cocaine condition self-administered more than Non-EE low drug-takers and Non-EE saline rats, which did not differ from one another. In addition, there was a significant main effect of trials, F(13, 728)=2.28, p < 0.01. Finally, a significant group × trials interaction was found, F(26, 728)=1.79, p < 0.01. Post hoc tests of this two-way interaction indicated that Non-EE high drug-takers self-administered more cocaine than Non-EE low drug-takers and Non-EE saline rats during all self-administration training sessions (trials 1-14; ps < 0.01).

Figure 2.

Mean (+/- SEM) number of infusions self-administered/60 min. Left panel. Mean (+/- SEM) number of infusions self-administered across trials by rats housed in the non-enriched environment (Non-EE) in the saccharin-saline (white circles), saccharin-cocaine low (black circles), or saccharin-cocaine high (black triangles) condition. * denotes statistical significance (ps < 0.01) compared to Non-EE saccharin-cocaine low and # denotes statistical significance (p < 0.01) compared to Non-EE saccharin-saline. Right panel. Mean (+/- SEM) number of infusions self-administered across trials by rats housed in the enriched environment (EE) in the saccharin-saline (white circles), saccharin-cocaine low (black circles), or saccharin-cocaine high (black triangles) condition.

Similarly, the EE group was analyzed using a 2 × 14 mixed factorial ANOVA varying group (saline or low drug-takers) and trials (1-14; see right panel of Figure 2a). No significant differences in cocaine intake across trials were found between EE low drug-takers and EE saline rats. As stated, the single high drug-taker in the EE condition was excluded from the analysis.

Terminal number of infusions

A one-way ANOVA conducted on the terminal (averaged across trials 13-14) number of infusions for the Non-EE group revealed a similar pattern. Thus, post hoc tests of a significant main effect of group, F(2, 56)=47.53, p < 0.01, indicated that Non-EE high drug-takers self-administered many more infusions than Non-EE saline rats and Non-EE low drug-takers (p < 0.01; see Figure 3, left panel), while Non-EE saline rats and Non-EE low drug-takers did not differ from one another. Interestingly, a separate one-way ANOVA showed that the main effect of group was not significant in the EE condition (F < 1).

Figure 3.

Left panel. Mean (+/- SEM) terminal (trials 13-14) number of cocaine infusions self-administered by rats housed in the non-enriched environment (Non-EE) in the saccharin-saline (white bar), saccharin-cocaine low (light gray bar), or saccharin-cocaine high (dark gray bar) condition. * denotes statistical significance (p < 0.01) compared to Non-EE saccharin-cocaine low and Non-EE saccharin-saline. Right panel. Mean (+/- SEM) terminal (trials 13-14) number of infusions self-administered by rats housed in the enriched environment (EE) in the saccharin-saline (white bar), saccharin-cocaine low (light gray bar), or saccharin-cocaine high (dark gray bar) condition.

Terminal latency to first infusion

A similar pattern was obtained with the latency data. A one-way ANOVA conducted on the terminal (averaged across trials 13-14) latency to make the first infusion for the Non-EE group revealed a significant main effect of group, F(2, 56)=12.55, p < 0.01. Post hoc tests indicated that Non-EE low drug takers were significantly slower to self-administer their first cocaine infusion compared to Non-EE saline rats and Non-EE high drug-takers (p < 0.01; see Figure 4, left panel), while Non-EE saline rats and Non-EE high drug-takers did not differ from one another. Likewise, a one-way ANOVA conducted on the terminal latency to make the first infusion for the EE group revealed a significant main effect of group, F(1, 31)=5.67, p < 0.03, indicating that EE low drug-takers also were slower to self-administer their first cocaine infusion compared to EE saline rats (see Figure 4, right panel). Again, it was not possible to compare the performance of the low drug-takers in the EE condition with the high drug-taker as there was only one EE rat that fell into the high drug-taking group. This rat, of course, initiated the first drug infusion with a very short latency. Finally, one-way ANOVAs were used to compare latencies among the saline and low drug-taker groups in the Non-EE vs. EE conditions. While low drug-takers in the EE condition tended to exhibit longer latencies than their Non-EE counterparts, this difference did not attain statistical significance (F(1, 55)=2.91, p > 0.05). Also, there was no difference between the saline groups (F > 1). Low drug-takers, then, took a long time to initiate their first infusion, and this was true whether the rats were housed under non-enriched or enriched conditions. All high drug-takers, on the other hand, were quick to initiate self-administration.

Figure 4.

Left panel. Mean (+/- SEM) terminal (trials 13-14) latency (s) to self-administer the first infusion for rats housed in the non-enriched environment (Non-EE) in the saccharin-saline (white bar), saccharin-cocaine low (light gray bar), or saccharin-cocaine high (dark gray bar) condition. * denotes statistical significance (p < 0.01) compared to Non-EE saccharin-cocaine low and Non-EE saccharin-saline. Right panel. Mean (+/- SEM) terminal (trials 13-14) latency (s) to self-administer the first infusion for rats housed in the enriched environment (EE) in the saccharin-saline (white bar), saccharin-cocaine low (light gray bar), or saccharin-cocaine high (dark gray bar) condition. # denotes statistical significance (p < 0.03) compared to EE saccharin-cocaine-low and EE saccharin-saline.

Progressive Ratio Testing

Terminal break point

Performance during PR testing matched that obtained during FR training (see Figure 5). A one-way ANOVA conducted on the terminal PR infusions (i.e., infusions self-administered during the final PR test) for the Non-EE group revealed a significant main effect of group, F(2, 56)=15.24, p < 0.01. Post hoc tests indicated that Non-EE high drug-takers worked significantly harder to receive infusions (as indicated by significantly higher break points) compared to Non-EE saline rats and Non-EE low drug-takers, which did not differ from one another (ps < 0.01; see Figure 5, left panel). Once again, and in accordance with the FR data, there was no effect of group in the EE condition (F < 1; see Figure 5, right panel). Thus, in the EE condition, neither the saline rats nor the low drug-takers were willing to work for cocaine. Clearly, this was not the case for the one high drug-taking rat in the EE condition – who worked exceedingly hard.

Figure 5.

Left panel. Mean (+/- SEM) number of infusions self-administered during the final progressive ratio (PR) test by rats housed in the non-enriched environment (Non-EE) in the saccharin-saline (white bar), saccharin-cocaine low (light gray bar), or saccharin-cocaine high (dark gray bar) condition. * denotes statistical significance (p < 0.01) compared to Non-EE saccharin-cocaine low and Non-EE saccharin-saline. Right panel. Mean (+/- SEM) number of infusions self-administered during the final PR test by rats housed in the enriched environment (EE) in the saccharin-saline (white bar), saccharin-cocaine low (light gray bar), or saccharin-cocaine high (dark gray bar) condition.

Saccharin Intake

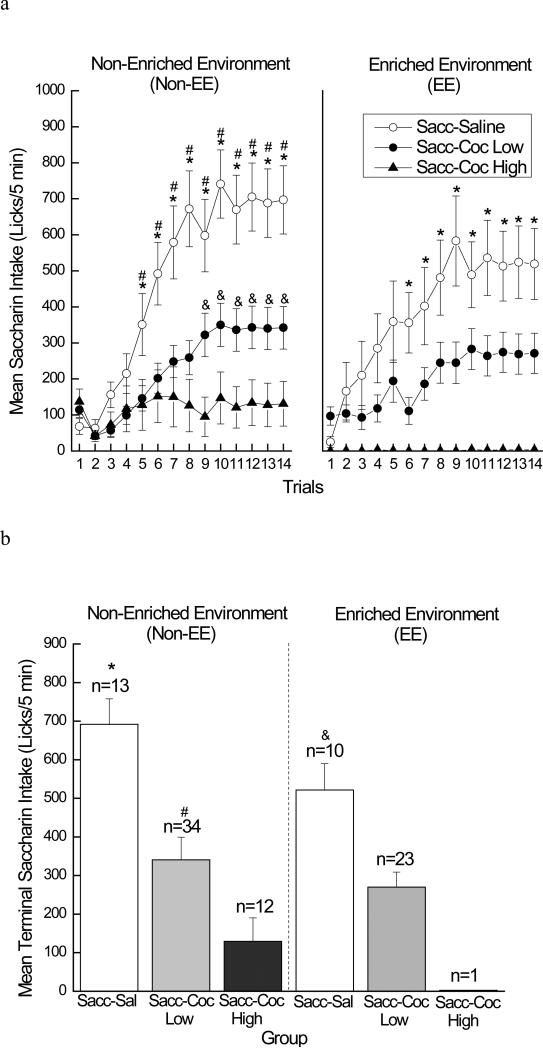

Saccharin intake across trials

Given the individual differences in cocaine self-administration, intake of the saccharin cue was analyzed accordingly. Thus, intake data for the Non-EE rats were analyzed using a 3 × 14 mixed factorial ANOVA varying group (saline, low drug-takers, or high drug-takers) and trials (1-14; see the left panel of Figure 6a). A significant main effect of group was found, F(2, 56)=10.04, p < 0.01. Post hoc tests indicated that Non-EE low and high drug-takers drank less saccharin than Non-EE saline rats, overall (ps < 0.01), while intake by Non-EE low and high drug-takers did not significantly differ from one another. In addition, there was a significant main effect of trials, F(13, 728)=27.34, p < 0.01, indicating that saccharin intake increased across trials, overall. Finally, a significant group × trials interaction was found, F(26, 728)=6.72, p < 0.01. Post hoc tests of this two-way interaction showed that Non-EE low drug-takers and Non-EE high drug-takers drank less saccharin than Non-EE saline rats on trials 5-14 (ps < 0.02 and ps < 0.04, respectively). In addition, Non-EE high drug-takers drank less saccharin than Non-EE low drug-takers on trials 9-14 (ps < 0.03).

Figure 6.

Mean (+/- SEM) saccharin intake (licks/5 min). a) Left panel. Mean (+/- SEM) saccharin intake (licks/5 min) across trials for rats housed in the non-enriched environment (Non-EE) in the saccharin-saline (white circles), saccharin-cocaine low (black circles), or saccharin-cocaine high (black triangles) condition. * denotes statistical significance (ps < 0.02) compared to Non-EE saccharin-cocaine low and # and & denote statistical significance (ps < 0.04 and ps < 0.03, respectively) compared to Non-EE saccharin-cocaine high. Right panel. Mean (+/- SEM) saccharin intake (licks/5 min) across trials for rats housed in the enriched environment (EE) in the saccharin-saline (white circles), saccharin-cocaine low (black circles), or saccharin-cocaine high (black circles) condition. * denotes statistical significance (ps < 0.03) compared to EE saccharin-cocaine low. b) Left panel. Mean (+/- SEM) terminal (trials 13-14) saccharin intake (licks/5 min) for rats housed in the non-enriched environment (Non-EE) in the saccharin-saline (white bar), saccharin-cocaine low (light gray bar), or saccharin-cocaine high (dark gray bar) condition. * denotes statistical significance (p < 0.01) compared to Non-EE saccharin-cocaine low and Non-EE saccharin-cocaine high and # denotes statistical significance (p = 0.05) compared to Non-EE saccharin-cocaine high. Right panel. Mean (+/- SEM) terminal (trials 13-14) saccharin intake (licks/5 min) for rats housed in the enriched environment (EE) in the saccharin-saline (white bar), saccharin-cocaine low (light gray bar), or saccharin-cocaine high (dark gray bar) condition. & denotes statistical significance (p < 0.03) compared to EE saccharin-cocaine low and EE saccharin-cocaine high.

Similarly, the EE group was analyzed using a 2 × 14 mixed factorial ANOVA varying group (saline or low drug-takers) and trials (1-14; see right panel of Figure 6a). A significant main effect of group was found, F(1, 31)=5.67, p < 0.03, indicating that EE low drug-takers drank less saccharin than EE saline rats, overall. In addition, there was a significant main effect of trials, F(13, 403)=18.27, p < 0.01, showing that saccharin intake increased across trials. Finally, a significant group × trials interaction was obtained, F(13, 403)=3.42, p < 0.01. Post hoc tests of this two-way interaction showed that EE low drug-takers drank less saccharin than EE saline rats on trials 6-14 (ps < 0.03).

In addition, separate 2 × 14 mixed factorial ANOVAs varying housing (Non-EE or EE) and trials (1-14) were used to directly compare saccharin intake among the saline and low drug-taker groups housed in the Non-EE versus EE conditions. Analysis of the saline group revealed that, while saline rats in the EE condition tended to consume less saccharin than their Non-EE counterparts, saccharin intake did not differ as a function of housing condition. Thus, the main effect of housing was not significant (F < 1). The main effect of trials was significant, F(13, 273)=29.22, p < 0.01, indicating that saccharin intake increased across trials for rats in both housing conditions, overall. Also, there was a significant housing × trials interaction, F(13, 273)=2.27, p < 0.01, but post hoc tests of that two-way interaction were not informative. Analysis of the low drug-taking group revealed similar results. The main effect of housing was not significant (F < 1). There was a significant main effect of trials, F(13, 715)=19.23, p < 0.01, indicating that, overall, saccharin intake increased across trials, regardless of housing condition. Finally, the housing × trials interaction also was not significant, F(13, 715)=1.50, p > 0.05.

Terminal saccharin intake

For the Non-EE group, a one-way ANOVA conducted on terminal saccharin intake (averaged across trials 13-14) also revealed a significant main effect of group, F(2, 56)=10.03, p < 0.01. Post hoc tests indicated that Non-EE low and high drug-takers exhibited lower terminal saccharin intake than saline rats (ps < 0.01) and that Non-EE high drug-takers exhibited lower terminal saccharin intake than Non-EE low drug-takers (p = 0.05; see left panel of Figure 6b). Likewise, a one-way ANOVA conducted on terminal saccharin intake for the EE group also revealed a significant main effect of group, F(1, 31)=5.55, p < 0.03, indicating that EE low drug-takers exhibited lower terminal saccharin intake than EE saline rats (see right panel of Figure 6b).

Similar to the group comparisons conducted on the saccharin intake data, one-way ANOVAs were used to directly compare terminal saccharin intake among the saline and low drug-taker groups housed in the Non-EE versus EE conditions. These analyses revealed no significant differences between the saline groups (F(1,21)=1.51, p > 0.05) or between the low drug-taking groups (F < 1). Together, the data indicate that environmental enrichment had no effect on intake of the drug-associated taste cue.

General Discussion

Consistent with previous findings with male Sprague-Dawley rats (Grigson and Twining, 2002; Piazza et al., 1989; Piazza et al., 2000; Puhl et al., 2009), individual differences in responding for cocaine were evident among our subjects. Specifically, we were able to identify two sub-populations of rats based on their terminal cocaine intake: low drug-takers (n=57) and high drug-takers (n=13). Surprisingly, while these differences were clearly evident among rats in the Non-EE condition (approximately 26% of the rats in the Non-EE condition proved to be high drug-takers), only one rat from the EE condition (approximately 4%) fell into the high drug-taking group. Thus, the majority of rats in the EE condition that had the opportunity to self-administer cocaine failed to acquire the behavior. Indeed, when examining their behavior, most rats housed in the enriched environment performed like low drug-takers housed in the non-enriched condition. They self-administered very few infusions on the FR schedule of reinforcement, they were slow to self-administer the drug, and, when tested on the PR schedule of reinforcement, they failed to work for cocaine (see Table 1). These PR data suggest that exposure to an enriched environment for a relatively short period of time in adulthood (and, in this case, during the same period of time as cocaine self-administration training) may decrease the perceived incentive reward value of cocaine as hypothesized, and, ultimately, prevent acquisition of drug-taking behavior. To the authors’ knowledge, these are the first data of their kind.

Table 1.

Behavioral Effects of Environmental Enrichment in Adult Male Rats

| Non-enriched Environment (Non-EE) | Enriched Environment (EE) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sacc-Sal | Sacc-Coc Low | Sacc-Coc High | Sacc-Sal | Sacc-Coc Low | |

| FR Saline/Cocaine Intake | ↓ | ↓ | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ |

| FR Latency to Initiate Self-Administration | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ |

| PR Break Point | ↓ | ↓ | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ |

| Saccharin Intake | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | ↑ | ↓ |

*** ↑ indicates an increase in magnitude of the behavioral parameter shown, while ↓ indicates a decrease in magnitude of the behavioral parameter shown.

In addition to hypothesizing that rats in the EE condition would exhibit reduced acquisition of drug intake compared to rats in the Non-EE condition, we also hypothesized that rats in the EE condition would not devalue the saccharin cue that had been paired with the opportunity to self-administer cocaine. Specifically, we hypothesized that housing in the EE condition would reduce cocaine-induced devaluation of the saccharin cue because, at the very least, cocaine itself would lose some of its incentive value. As summarized above, it certainly appears that cocaine lost some of its incentive value for rats housed in the EE condition. Even so, EE rats in the saccharin-cocaine condition significantly avoided intake of the drug-associated saccharin cue relative to intake by the saline treated EE controls. This pattern of data may suggest that housing in the EE condition may have blunted the perceived incentive value of both the drug and the sweet, with the perceived relative differences between the two rewards remaining intact. This general conclusion is consistent with the trend for reduced saccharin intake in the saline treated EE rats and with other studies showing that environmental enrichment can cause a decrease in sucrose consumption (Brenes and Fornaguera, 2008), attenuate cue-induced reinstatement of sucrose seeking (Grimm et al., 2008), and decrease responding for other non-drug rewards, such as novel environmental stimuli (Cain et al., 2006).

While it is possible that rats housed in the EE may continue to exhibit drug-induced devaluation of the taste cue, despite minimal responding for drug, an alternative explanation must be considered. Specifically, rats in the EE condition may continue to suppress intake of the taste cue because the drug-associated cue elicits potent drug cravings and withdrawal, despite a history of very low drug-taking behavior. This consideration is possible, but seems unlikely given previous data suggesting that cue-induced craving and withdrawal likely leads to short latencies to self-administer the drug when given the opportunity (Wheeler et al., 2008). Data from the current study show that all rats housed in the EE condition, save one, had very long latencies to self-administer cocaine. This is opposite to the rapid “correction” (i.e., rapid self-administration) that might be expected were the rats in the EE condition to be experiencing high levels of cue-induced craving and withdrawal. As such, we conclude that environmental enrichment can reduce responding to the absolute reinforcing properties of sweets and drugs, but that housing in an EE has little overall impact on responding to relative reward properties. Thus, unless some other mechanism is identified (i.e., something other than drug-induced devaluation and/or cue-induced craving/withdrawal), we must conclude that the drug is valued by the EE rat and that anticipation of drug availability devalues the taste cue. Such a conclusion is interesting as Puhl et al. (2009) showed that rats with a history of low drug-taking seek like high drug-takers when the expected drug is omitted during extinction testing. Low drug-takers, then, are not unmotivated. Instead, they are well motivated, but to take only a small amount of drug. It is possible, then, that the low drug-takers, even in the EE condition, have some level of motivation for the 0.167 mg/infusion dose of cocaine and that the low level of motivation is revealed by avoidance of the taste cue.

The composition of one's surrounding environment and the value (i.e., negative or positive) of the stimuli that make up that environment have very powerful effects on drug-seeking and drug-taking behaviors. In fact, stress and environmental enrichment have been shown to exert opposing effects on such behaviors. Generally, stress has been shown to increase responding for drugs of abuse, including cocaine, amphetamine, and heroin (see Goeders, 2002, Lu et al., 2003, and Marinelli and Piazza, 2002 for a review), while environmental enrichment during adolescence (Bardo et al., 2001; El Rawas et al., 2008; Green et al., 2002; Green et al., 2003) or exposure to sweets in adulthood (Carroll and Lac, 1993; Lenoir et al., 2007; Liu and Grigson, 2005) have been shown to decrease responding. In addition, exposure to stress is a potent inducer of reinstatement and relapse in animals and humans, respectively (see Shaham et al., 2000 and Stewart, 2000 for a review). In contrast, environmental enrichment has been shown to be protective against the development of drug-seeking and drug-taking behaviors (Bardo et al., 2001; El Rawas et al., 2008; Green et al., 2002; Green et al., 2003; Solinas et al., 2008a) and recent evidence shows that the availability of a novel object alternative decreases cocaine seeking in a conditioned place preference paradigm (Reichel and Bevins, 2010).

Insight into the differential effects of stress and environmental enrichment may be found in the underlying changes in neuroanatomy and neurochemistry instituted by each. Exposure to stressors (e.g., footshock, social isolation, food deprivation/restriction) results in the activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, stimulating the production of corticotrophin-releasing hormone (CRH) by the hypothalamus, which, in turn, stimulates the production of glucocorticoid hormones (cortisol in humans, corticosterone in rodents; see Papadimitriou and Priftis, 2009 for a review). Corticosterone has been shown to have site-specific actions modifying dopamine transmission in the nucleus accumbens (see Marinelli and Piazza, 2002 for a review), a prominent structure in the mesocorticolimbic dopamine system, which is heavily involved in the processing of rewards. In addition, corticosterone and CRH have been shown to be critical for the acquisition and maintenance of cocaine, amphetamine, and heroin self-administration (see Goeders, 2002, Lu et al., 2003, and Marinelli and Piazza, 2002 for a review) and corticosterone has been shown to play a permissive role in the food deprivation-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking (Shalev et al., 2003). Also, CRH and norepinephrine signaling in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis and central nucleus of the amygdala mediate stress-induced reinstatement of drug-seeking and drug-taking behaviors (Leri et al., 2002).

Environmental enrichment has been shown to have profoundly different effects on some of the same neural substrates. In rats, environmental enrichment causes a decrease in baseline levels of coricosterone (Belz et al., 2003; Welberg et al., 2006) and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH; Belz et al., 2003), a decrease in the expression of DAT proteins in the medial prefrontal cortex (Zhu et al., 2005), and an increase in the binding of serotonin in the forebrain (Hellemans et al., 2005). In mice, environmental enrichment has several effects on gene expression in the striatum. It causes a reduction in cocaine-induced expression of the immediate early gene zif-268 in the nucleus accumbens (Solinas et al., 2008b) and also affects levels of several genes involved in synaptic plasticity, such as protein kinase C λ (PKCλ) and mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 12 (MAP3K12; Thiriet et al., 2008). In addition, environmental enrichment results in higher baseline levels of ΔFos B in the striatum, but abolishes the increase in ΔFos B stimulated by repeated cocaine self-administration (Solinas et al., 2008b). Mice housed in an enriched environment are resistant to the locomotor effects of cocaine and express a lower number of DAT proteins in the striatum compared to mice housed in a standard environment (Bezard et al., 2003). Finally, in rats, environmental enrichment also causes an increase in cortical weight and thickness (Bennett et al., 1969; Diamond et al., 1972), an increase in neuronal densities (Turner and Greenough, 1985), stimulates dendritic growth and branching (Wallace et al., 1992; Volkmar and Greenough, 1972), and stimulates the maintenance of a greater number of synaptic connections in the visual cortex (Briones et al., 2004). Exposure to a sweet is, perhaps, a kind of enrichment. But little has been done to identify the underlying cellular and molecular mechanism by which it may be protective. We do know, however, that prior exposure to a sweet can fully prevent the dopamine peek in the accumbens that typically accompanies a systemic injection of morphine (Grigson & Hajnal, 2007). As such, the inclusion of the sweet cue in the present report may have contributed to reduced responding for the low dose of cocaine, but it would have done so for both the EE and the non-EE subjects. A future assessment of the effect of EE on acquisition of cocaine self-administration in adult rats should be undertaken without the use of the taste cue.

Regarding the possible impact of environmental enrichment on the brain, it is important to note that all of the above mentioned studies were conducted in rats that had been reared in an enriched environment throughout adolescence. The results of the current study suggest that environmental enrichment experienced only during adulthood has the ability to mediate some of these same effects in the adult brain, a presumably less dynamic milieu with a lesser capacity for changes in plasticity. Not only does environmental enrichment appear to be a stimulus powerful enough to prevent the acquisition of drug-taking and drug-seeking behaviors, it also is tends to reduce intake of a palatable natural reward, such as saccharin. Given the data, it is possible that environmental enrichment may alter the perceived hedonic value of rewarding stimuli by acting in the same regions of the brain (namely the mesocorticolimbic dopamine system) as natural rewards and drugs of abuse. It is also important to note that the Non-EE rats in the current study were not exposed to any sort of deprivation state or deficient circumstances; they were simply housed in standard conditions, with food and water freely available. Because the “non-enriched” environment is consistent with standard housing conditions, these data have implications for much of the self-administration data obtained in adult rats. Of course, we must consider the likelihood that “standard” housing conditions are, in fact, impoverished for rats. These results also must bring into question the settings most commonly used for human rehabilitation from drug abuse (e.g., correctional facilities and rehabilitation clinics). In some cases, the make-up of such environments may be acting counterproductively to the goals of treatment. This is a critical point, given data suggesting that nearly 70% of those in prison are incarcerated due to drug-related crimes (National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2006). With such an alarming percentage, a little enrichment may go a long way and would be relatively inexpensive compared to the costs of years of incarceration. Support for such an idea is provided by data showing improved abstinence in non-incarcerated humans “working” (i.e., maintaining abstinence) to earn tokens for natural rewards (Garcia-Rodriguez et al., 2009; Higgins et al., 1993).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the National Institute on Drug Abuse for generously supplying the cocaine HCl used in this study. This work was supported by grants DA009815 and DA023315 from the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Anthony JC, Helzer JE. Syndromes of drug abuse and dependence. In: L. N. Robins, Regier DA., editors. Psychiatric Disorders in America. Free Press; New York: 1991. pp. 116–154. [Google Scholar]

- Bardo MT, Klebaur JE, Valone JM, Deaton C. Environmental enrichment decreases intravenous self-administration of amphetamine in female and male rats. Psychopharmacology. 2001;155(3):278–284. doi: 10.1007/s002130100720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belz EE, Kennell JS, Czambel RK, Rubin RT, Rhodes ME. Environmental enrichment lowers stress-responsive hormones in singly housed male and female rats. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, & Behavior. 2003;76(3-4):481–486. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett EL, Rosenzweig MR, Diamond MC. Rat brain: Effects of environmental enrichment of wet and dry weights. Science. 1969;163(3869):825–826. doi: 10.1126/science.163.3869.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezard E, Dovero S, Belin D, Duconger S, Jackson-Lewis V, Przedborski S, Piazza PV, Gross CE, Jaber M. Enriched environment confers resistance to 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine and cocaine: Involvement of dopamine transporter and trophic factors. Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;23(35):10999–11007. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-35-10999.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenes JC, Fornaguera J. Effects of environmental enrichment and social isolation on sucrose consumption and preference: Associations with depressive-like behavior and ventral striatum dopamine. Neuroscience Letters. 2008;436(2):278–282. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briones TL, Klintsova AY, Greenough WT. Stability of synaptic plasticity in the adult rat visual cortex induced by complex environmental exposure. Brain Research. 2004;1018(1):130–135. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cain ME, Green TA, Bardo MT. Environmental enrichment decreases responding for visual novelty. Behavioural Processes. 2006;73(3):360–366. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2006.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappell H, LeBlanc AE. Conditioned aversion to saccharin by single administrations of mescaline and d-amphetamine. Psychopharmacologia. 1971;22(4):352–356. doi: 10.1007/BF00406873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappell H, LeBlanc AE. Parametric investigations of the effects of prior exposure to amphetamine and morphine on conditioned gustatory aversion. Psychopharmacology. 1977;51(3):265–271. doi: 10.1007/BF00431634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll ME, Lac ST. Autoshaping i.v. cocaine self-administration in rats: Effects of nondrug alternative reinforcers on acquisition. Psychopharmacology. 1993;110(1-2):5–12. doi: 10.1007/BF02246944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauvet C, Lardeux V, Goldberg SR, Jaber M, Solinas M. Environmental enrichment reduces cocaine seeking and reinstatement induced by cues and stress but not by cocaine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34(13):2767–2778. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond MC, Rosenzweig MR, Bennett EL, Lindner B, Lyon L. Effects of environmental enrichment and impoverishment on rat cerebral cortex. Journal of Neurobiology. 1972;3(1):47–64. doi: 10.1002/neu.480030105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Rawas R, Thiriet N, Lardeux V, Jaber M, Solinas M. Environmental enrichment decreases the rewarding but not the activating effects of heroin. Psychopharmacology. 2008;203(3):561–570. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1402-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Rodriguez O, Secades-Villa R, Higgins ST, Fernandez-Hermida JR, Carballo JL, Errasti Perez JM, Al-halabi Diaz S. Effects of voucher-based intervention on abstinence and retention in an outpatient treatment for cocaine addiction: a randomized controlled trial. Experimental & Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2009;17(3):131–138. doi: 10.1037/a0015963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goeders N. Stress and cocaine addiction. Journal of Pharmacology & Experimental Therapeutics. 2002;301(3):785–789. doi: 10.1124/jpet.301.3.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein RZ, Tomasi D, Alia-Klein M, Cottone LA, Zhang L, Telang F, Volkow ND. Subjective sensitivity to monetary gradients is associated with frontolimbic activation to reward in cocaine abusers. Drug & Alcohol Dependence. 2007;87(2-3):233–240. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green TA, Gehrke BJ, Bardo MT. Environmental enrichment decreases intravenous amphetamine self-administration in rats: Dose-response functions for fixed-and progressive-ratio schedules. Psychopharmacology. 2002;162(4):373–378. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1134-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green TA, Cain ME, Thompson M, Bardo MT. Environmental enrichment decreases nicotine-induced hyperactivity in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2003;170(3):235–241. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1538-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigson PS. Conditioned taste aversions and drugs of abuse: a reinterpretation. Behavioral Neuroscience. 1997;111(1):129–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigson PS. Reward comparison: The Achilles’ heel and hope for addiction. Drug Discovery Today: Disease Models. 2008;5(4):227–233. doi: 10.1016/j.ddmod.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigson PS, Hajnal A. Once is too much: Conditioned changes in accumbens dopamine following a single saccharin-morphine pairing. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2007;121(6):1234–1242. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.121.6.1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigson PS, Twining RC. Cocaine-induced suppression of saccharin intake: A model of drug-induced devaluation of natural rewards. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2002;116(2):321–333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigson PS, Twining RC, Carelli RM. Heroin-induced suppression of saccharin intake in water-deprived and free-feeding rats. Pharmacology Biochemistry & Behavior. 2000;66(3):603–608. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(00)00253-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm JW, Osincup D, Wells B, Manaois M, Fyall A, Buse C, Harkness JH. Environmental enrichment attenuates cue-induced reinstatement of sucrose seeking in rats. Behavioral Pharmacology. 2008;19(8):777–785. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e32831c3b18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellemans KGC, Nobrega JN, Olmstead MC. Early environmental experience alters baseline and ethanol-induced cognitive impulsivity: Relationship to forebrain 5-HT1A receptor binding. Behavioural Brain Research. 2005;159(2):207–220. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2004.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ST, Budney AJ, Bickel WK, Hughes JR, Foerg F, Badger G. Achieving cocaine abstinence with a behavioral approach. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1993;150(5):763–769. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.5.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones S, Casswell S, Zhang JF. The economic costs of alcohol-related absenteeism and reduced productivity among the working population of New Zealand. Addiction. 1995;90(11):1455–1461. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1995.901114553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley AE, Berridge KC. The neuroscience of natural rewards: Relevance to addictive drugs. Journal of Neuroscience. 2002;22(9):3306–3311. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-09-03306.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Magnen J. Peripheral and systemic actions of food in caloric regulation of intake. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1969;157(2):1126–1157. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1969.tb12940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenoir M, Ahmed SH. Supply of a nondrug substitute reduces escalated heroin consumption. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;33(9):2272–2282. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenoir M, Serre F, Cantin L, Ahmed SH. Intense sweetness surpasses cocaine reward. PLoS One. 2007;2(1):e698. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leri F, Flores J, Rodaros D, Stewart J. Blockade of stress-induced but not cocaine-induced reinstatement by infusion of noradrenergic antagonists into the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis or the central nucleus of the amygdala. Journal of Neuroscience. 2002;22(13):5713–5718. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-13-05713.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Grigson PS. Brief access to sweets protect against relapse to cocaine-seeking. Brain Research. 2005;1049(1):128–131. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L, Shepard JD, Hall FS, Shaham Y. Effect of environmental stressors on opiate and psychostimulant reinforcement, reinstatement and discrimination in rats: A review. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2003;27(5):457–491. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(03)00073-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinelli M, Piazza PV. Interaction between glucocorticoid hormones, stress and psychostimulant drugs. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2002;16(3):387–394. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair P, Black MM, Schuler M, Keane V, Snow L, Rigney BA, Magder L. Risk factors for disruption in primary caregiving among infants of substance abusing women. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1997;21(11):1039–1051. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(97)00064-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Mental Health http://www.nimh.nih.gov.

- National Institute on Drug Abuse http://www.nida.nih.gov.

- O'Brien CP. A range of research-based pharmacotherapies for addiction. Science. 1997;278(5335):66–70. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5335.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadimitriou A, Priftis KN. Regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2009;16(5):265–271. doi: 10.1159/000216184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza PV, Deminière J, Le Moal M, Simon H. Factors that predict individual vulnerability to amphetamine self-administration. Science. 1989;245(4925):1511–1513. doi: 10.1126/science.2781295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza PV, Deroche-Gamonet V, Rouge-Pont F, Le Moal M. Vertical shifts in self-administration dose-response functions predict a drug-vulnerability phenotype predisposed to addiction. Journal of Neuroscience. 2000;20(11):4226–4232. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-11-04226.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puhl MD, Fang J, Grigson PS. Acute sleep deprivation increases the rate and efficiency of cocaine self-administration, but not the perceived value of cocaine in rats. Pharmacology, Biochemisty, & Behavior. 2009;94(2):262–270. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichel CM, Bevins RA. Competition between novelty and cocaine conditioned reward is sensitive to drug dose and retention interval. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2010;124(1):141–151. doi: 10.1037/a0018226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santolaria-Fernández FJ, Gómez-Sirvent JL, González-Reimers CE, Batista-López JN, Jorge-Hernández JA, Rodríguez-Moreno F, Martínez-Riera A, Hernández-García MT. Nutritional assessment of drug addicts. Drug & Alcohol Dependence. 1995;38(1):11–18. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(94)01088-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaham Y, Erb S, Stewart J. Stress-induced relapse to heroin and cocaine seeking in rats: A review. Brain Research: Brain Research Reviews. 2000;33(1):13–33. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(00)00024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalev U, Marinelli M, Baumann MH, Piazza P, Shaham Y. The role of corticosterone in food deprivation-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking in the rat. Psychopharmacology. 2003;168(1-2):170–176. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1200-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solinas M, Chauvet C, Thiriet N, El Rawas R, Jaber M. Reversal of cocaine addiction by environmental enrichment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008a;105(44):17145–17150. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806889105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solinas M, Thiriet N, El Rawas R, Lardeux V, Jaber M. Environmental enrichment during early stages of life reduces the behavioral, neurochemical, and molecular effects of cocaine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008b;34(5):1102–1111. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stairs DJ, Klein ED, Bardo MT. Effects of environmental enrichment on extinction and reinstatement of amphetamine self-administration and sucrose-maintained responding. Behavioural Pharmacology. 2006;17(7):597–604. doi: 10.1097/01.fbp.0000236271.72300.0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart J. Pathways to relapse: The neurobiology of drug- and stress-induced relapse to drug-taking. Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience. 2000;25(2):125–136. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiriet N, Amar L, Toussay X, Lardeux V, Ladenheim B, Becker KG, Cadet JL, Solinas M, Jaber M. Environmental enrichment during adolescence regulates gene expression in the striatum of mice. Brain Research. 2008;1222:31–41. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner AM, Greenough WT. Differential rearing effects on rat visual cortex synapses. I. Synaptic and neuronal density and synapse per neuron. Brain Research. 1985;329(1-2):195–203. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)90525-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twining RC, Bolan M, Grigson PS. Yoked delivery of cocaine is aversive and protects against the motivation for drug in rats. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2009;123(4):913–925. doi: 10.1037/a0016498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkmar FR, Greenough WT. Rearing complexity affects branching of dendrites in the visual cortex of the rat. Science. 1972;176(42):1445–1447. doi: 10.1126/science.176.4042.1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace CS, Kilman VL, Withers GS, Greenough WT. Increases in dendritic length in occipital cortex after four days of differential housing in weanling rats. Behavioral & Neural Biology. 1992;58(1):64–68. doi: 10.1016/0163-1047(92)90937-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler RA, Twining RC, Jones JL, Slater JM, Grigson PS, Carelli RM. Behavioral and electrophysiological indices of negative affect predict cocaine self-administration. Neuron. 2008;57(5):774–785. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson SJ, Sayette MA, Delgado MR, Fiez JA. Effect of smoking opportunity on responses to monetary gain and loss in the caudate nucleus. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117(2):428–434. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.2.428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J, Apparsundaram S, Bardo MT, Dwoskin LP. Environmental enrichment decreases cell surface expression of the dopamine transporter in rat medial prefrontal cortex. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2005;93(6):1434–1443. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]