Abstract

We investigated the influence of the child’s behavior on the quality of the mutual parent-child attachment relationships across three generations. We did so using a prospective longitudinal study which spanned 20 years from adolescence through adulthood. Study participants completed in-class questionnaires as students in the East Harlem area of New York City at the first wave and provided follow-up data at 4 additional points in time. 390 participants were included in these analyses; 59% female, 45% African American, and 55% Puerto Rican. Using structural equation modeling, we determined that externalizing behavior in the child was negatively related to the mutual parent-child attachment relationship for two generations of children. We also found continuity in externalizing behavior for the participant over time and from the participant to his/her child. Additionally, we found continuity in the quality of the mutual attachment relationship from the participant’s relationship with his/her parents to the participant’s relationship with his/her child. Finally, the mutual attachment relationship of the participant with his/her parents had a negative association with the participant’s externalizing behavior in adulthood. Based on these results, we propose that family interventions should focus on the role of the child’s externalizing behavior in the context of the parent-child attachment relationship. Furthermore, we suggest that prevention programs should address externalizing behavior as early as possible, as the effects of externalizing behavior in adolescence can persist into adulthood and extend to the next generation.

Keywords: child behavior, adult behavior, parent-child relations, multi-generation, transmission

Introduction

A central theme of research on psychopathology is the influence of the parent-child relationship on the child’s behavioral development (e.g., Conger, Neppl, Kim, & Scaramella, 2003). Though studies of the impact of parents on children are essential, it is also important to examine the influence of the child’s behavior on the mutual parent-child attachment relationship. The term “mutual parent-child attachment relationship” has been used to refer to both the parent’s affection for and attention given to the child and the child’s regard for and identification with his/her parent. This concept has been used extensively in our own work (e.g., Brook et al., 1998), and a similar concept has been used in the work of other research teams (Sieving, McNeely, & Blum, 2000).

The association of the child’s externalizing behavior with the mutual parent-child attachment relationship is of particular interest because externalizing behavior has previously been correlated with a number of negative outcomes outside of the parent-child relationship. Externalizing behavior was first described by Achenbach (1966), who described it as a super-construct comprised of delinquent and aggressive behavior syndromes (Achenbach, 1991). Externalizing behavior in childhood has been shown to be associated with increased likelihood of heavy drinking (Englund, Egeland, Oliva, & Collins, 2008), less academic competence (Masten et al., 2005), long term unemployment (Wiesner, Vondracek, Capaldi, & Porfeli, 2003), and even early mortality (Jokela, Ferrie, & Kivimäki, 2009) in adolescence and adulthood. Furthermore, externalizing behavior has significant stability, in that those who exhibit externalizing behavior in childhood and adolescence are more likely to exhibit externalizing behavior in adulthood as well (Masten et al., 2005; Neppl, Conger, Scaramella, & Ontai, 2009). Moffitt terms externalizing behavior that continues into adulthood Life-Course-Persistent Antisocial Behavior (Moffitt, 1993).

Some studies have supported the influence of child problem behavior on the child’s relationships with his/her parents (e.g., Dogan, Conger, Kim, & Masyn, 2007; Kerr & Stattin, 2003). For example, Fite, Colder, Lochman, and Wells (2006) reported that externalizing behavior in the child predicted poor parental monitoring and inconsistent discipline.

Given support for the influence of the second generation (G2) child’s externalizing behavior on the relationship with his/her G1 parent, it is pertinent to consider whether the repercussions of the G2 child’s externalizing behavior may extend beyond the G1/G2 mutual parent-child attachment relationship by adversely affecting the G2 child’s own relationship with his/her G3 children (Neppl et al., 2009). Thornberry, Freeman-Gallant, Lizotte, Krohn, and Smith (2003), who found a direct relationship from more externalizing behavior in adolescence to less effective parenting in adulthood, suggest that antisocial behavior in adolescence may limit the personal and social resources available to the individual in adulthood when he/she becomes a parent.

One possible mechanism for the influence of the G2 externalizing behavior on the G2/G3 mutual attachment relationship is a path by which G2 externalizing behavior in adulthood predicts externalizing behavior in the G3 child. Conger et al. (2003) did not find a relationship between G2 and G3 antisocial behavior. Support for the intergenerational transmission of externalizing behavior, however, has recently developed. In a study of fathers, a team of investigators (Kerr, Capaldi, Pears, & Owen, 2009) found that behavioral problems were transmitted across three generations. Antisocial behavior in G1 was related to antisocial behavior in G2, which was related to G3 difficult temperament in early childhood on a path to G3 externalizing problems in middle childhood. Hicks, South, DiRago, Iacono, and McGue (2009) supported this finding with evidence of a genetic component to externalizing disorders which, through interaction with environmental risk factors, might account for the intergenerational transmission of externalizing behavior.

Another possible mechanism for the relationship of G2 externalizing behavior to the G2/G3 mutual attachment relationship is a path through the G1/G2 mutual attachment relationship. A number of studies have shown that an element of the parent-child relationship, positive parenting, in one generation is related to positive parenting in the next (Belsky, Jaffee, Sligo, Woodward, & Silva, 2005; Kerr et al., 2009; Kovan, Chung, & Sroufe, 2009). This intergenerational transmission of parenting practices has been explained in part by socialization processes such as modeling and bonding (Chen & Kaplan, 2001; Kerr et al., 2009).

A final factor to consider in the relationship of G2 externalizing behavior to the G2/G3 mutual attachment relationship is the influence of the G1/G2 mutual attachment relationship on G2 externalizing behavior in adulthood. Neppl et al. (2009), for example, found that harsh parenting in one generation predicted externalizing behavior in the next generation, which in turn was related to the latter’s harsh parenting toward their own children. However, other researchers (Kerr et al., 2009) did not find that G2 antisocial behavior was a significant mediator of the transmission from G1 to G2 of constructive parenting.

This study builds upon prior research by examining each of the aforementioned pathways from externalizing behavior in the child to the parent-child relationship in a comprehensive multi-generational model. Whereas other studies have examined individual components of this model (e.g., Kovan et al., 2009), only a limited number of research teams (e.g., Neppl et al., 2009) have investigated stability and transmission processes within a three-generational model. Furthermore, among those select studies, we are only aware of two that gave attention to positive parent-child relationships (Thornberry et al., 2003; Kerr et al., 2009). The present study is also noteworthy in that our focus is on the influence of the child on the mutual parent-child attachment relationship.

We examine this relationship in a sample that is itself distinctive in a number of aspects. The G2 sample includes both mothers and fathers, and these participants were followed over a 20 year period, during which time they progressed through a number of important developmental stages from adolescence to adulthood. Luthar and Latendresse (2005) recently emphasized a need for research on risk and protective processes for child well-being to be more “context specific” with regard to family socioeconomic status (SES). Indeed, current theory on developmental processes highlights the importance of parent well-being and parent-child relationships for child well-being among low SES-samples (Conger, Conger, & Martin, 2010). As our participants were originally sampled from East Harlem in New York City, the group is well-suited for further research on the parent, the child, and parent-child relationships within a low-SES context.

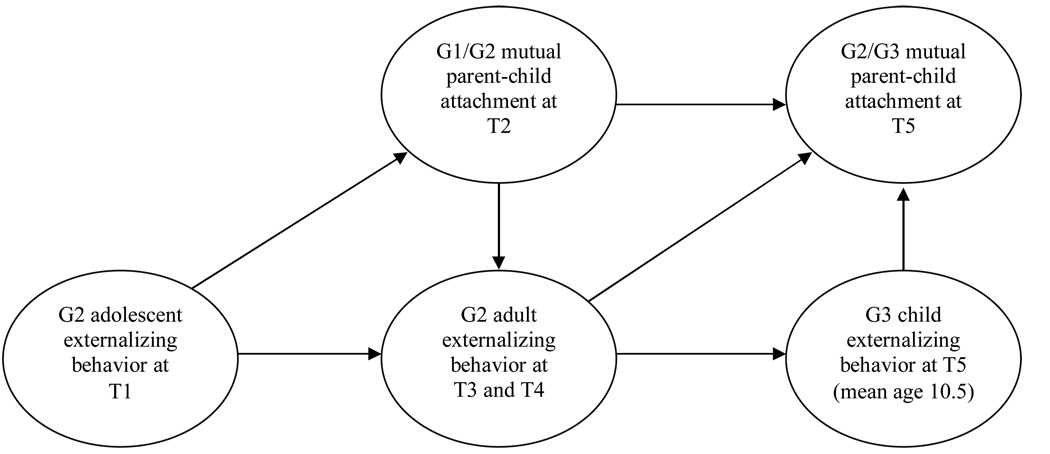

We propose the following hypotheses which are represented in the model depicted in Figure 1: (1) Externalizing in G2 adolescence is negatively related to close mutual parent-child attachment relationships between G1 and G2. Similarly, externalizing in G3 childhood is negatively related to close mutual parent-child attachment relationships between G2 and G3. (2) There is intragenerational continuity of externalizing behavior from G2 adolescence to adulthood and intergenerational continuity of externalizing behavior from the G2 parent to the G3 child. (3) There is also intergenerational continuity of close mutual parent-child attachment relationships from G1/G2 to G2/G3. (4) A close mutual parent-child attachment relationship between G1 and G2 is negatively related to G2 externalizing behavior in adulthood. (5) Externalizing behavior in the G2 adult is negatively related to a close mutual parent-child attachment relationship between G2 and G3.

Figure 1.

Hypothesized model: Pathways between the relations across the generations and externalizing behavior at different time points. G1= Generation 1, G2= Generation 2, G3= Generation 3. T1=Time 1, T2=Time 2, T3=Time 3, T4=Time 4, T5=Time 5. Mean age of respondents at T1=14.1, at T2=19.2, at T3=24.4, at T4=26.1, at T5=32.3. Mean age of G3 children at T5=10.5.

Methods

Participants

There were 390 participants (59% mothers, 41% fathers; 45% African Americans, 55% Puerto Ricans) who completed the T5 questionnaire and had at least one child between the ages of 4 and 18 at time 5 (T5). The mean age of the 390 participants at T5 was 32.3 (S.D. 1.2). The mean age of the oldest child at T5 was 10.5 years (S.D. 3.9 years).

Data on the participants were initially collected in 1990 (time 1; T1) when the students were attending schools in the East Harlem area of New York City. The questionnaires were completed in the classrooms with teachers not present. The mean age at this wave was 14.1 years (S.D. 1.3 years). At time 2 (T2; 1994 – 1996), the National Opinion Research Center located and interviewed the participants in person. The mean age of the participants at this wave was 19.2 years (S.D. 1.5 years). At time 3 (T3; 2000 – 2001) and at subsequent waves, the Survey Research Center of the University of Michigan collected the data. The mean age of the participants at T3 was 24.4 years (S.D. 1.3 years). At time 4 (T4; 2001 – 2003), we altered our sampling procedures to ensure that the attrition of respondents with more antisocial tendencies did not alter the composition of our sample. Because our focus was on smoking behavior, we selected a sub-sample of the T3 participants that represented smokers, quitters, and non-smokers, with smokers being oversampled. At this wave, respondents had an average age of 26.1 years (S.D. 1.4 years). At T5 (2007 – 2010), the average age of the participants was 32.3 years (S.D. of 1.3 years).

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Mount Sinai School of Medicine approved the study’s procedures for data collection in the earlier waves, and the New York University School of Medicine’s IRB approved the study for T5. A Certificate of Confidentiality was obtained from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Written informed assent was obtained from all minors after the procedures were fully explained. Passive consent procedures were followed for parents of minors. For participants older than age 18, informed consent was obtained. Additional information regarding the study methodology is available from previous reports (Brook, Brook, & Zhang, 2008).

We compared the demographic variables for the participants that were not seen at T5 but, due to their parental status at T4, would have been eligible for inclusion in this study if they had been seen at T5 (N=60), and those who participated at T5 and were eligible for inclusion in this study (i.e., had a child that was ≥ 4 years old, ≤ 18 years old at T5; N=390). Using a chi-squared test, we found that there were no significant differences in gender (χ2 =0.81, p=0.37, df=1) or socioeconomic status (SES)( χ2 =9.89, p=0.36, df=9). However, African American parents were less likely to be seen at T5 (χ2 =9.90, p<0.01, df=1). Of parents not seen at T5, 67% were African American, whereas of parents seen at T5, 45% were African American.

Psychosocial Measures

The psychosocial scales used in this study are presented in Table 1. As shown in Table 1, the measures were grouped into the following domains: G2 adolescent externalizing behavior at T1, mutual parent-child attachment between G1 and G2 measured at T2, G2 adult externalizing behavior at T3 and T4, G3 child externalizing behavior from the G2 parent’s report at T5, and mutual parent-child attachment between G2 and G3 from the G2 parent’s report at T5. Regarding predictive validity, these measures have been found to predict substance use and dependence as well as maladaptive personality attributes and psychiatric disorders (Brook, Whiteman, Finch, & Cohen, 2000; Brook et al., 2001; Brook et al., 2008; Petty et al., 2008). Each measure in the domain of G2 adult externalizing behavior was summed from two different time points (T3 and T4). All measures were based on the G2 participant’s responses. For the domains concerning the G3 child, the G2 participant was asked to report on his/her oldest child.

Table 1.

Measures: Sources and Cronbach’s Alphas

| Domain/Scale (no. of items) |

α | Source | Sample item |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | |||

| Gender | NA | - | Are you male or female? |

| Ethnicity | NA | - | Are you Hispanic (Puerto Rican)? |

| Socioeconomic status (5) | NA | Kogan, Smith, & Jenkins, 1977 | Combination of education level and job status of parents (G1) |

| G2 Adolescent externalizing behavior at T1 | |||

| Theft and vandalism (7) | .71 | Huizinga, Menard, & Elliott, 1989 (adapted) | How often have you taken something not belonging to you worth less than $5? |

| Aggression (2) | NA | Gold, 1966 (adapted); Huizinga et al., 1989 (adapted) | How often have you gotten into a serious fight? |

| Tobacco use (1) | NA | Brook, Pahl, & Ning, 2006 | How many cigarettes do you smoke a day? |

| Marijuana use (1) | NA | Siqueira & Brook, 2003 | How many times did you use marijuana in the past year? |

| G1/G2 Mutual parent-child attachment at T2 | |||

| Identification with parent (6) | .82 | Brook, Brook, Gordon, Whiteman, & Cohen, 1990 | How much do you admire or look up to your parents? |

| Parental Warmth (17) | .86 | Avgar, Bronfenbrenner, & Henderson, 1977 | Do your parents believe in showing their love for you? |

| Time spent with mother (3) | .71 | Brook et al., 1998 | How much time do you spend doing recreational things with your mother? |

| Time spent with father (2) | NA | Brook et al., 1998 | How much time do you spend with your father on an average Saturday or Sunday? |

| G2 Adult externalizing behavior at T3 and T4 | |||

| Theft and vandalism (22) | .84 | Huizinga et al., 1989 (adapted) | How often have you taken something not belonging to you worth less than $5? |

| Aggression (10) | .80 | Gold, 1966 (adapted); Huizinga et al., 1989 (adapted) | How often have you gotten into a serious fight? |

| Tobacco use (2) | NA | Brook et al., 2006 | How many cigarettes do you smoke a day? |

| Marijuana use (2) | NA | Siqueira & Brook, 2003 | How many times did you use marijuana in the past year? |

| G3 Child externalizing behavior at T5 (Parent report) | |||

| Child’s delinquency (6) | .64 | Achenbach, 1991 | How true is it that your child lies or cheats? |

| Child’s aggression (10) | .81 | Achenbach, 1991 | How true is it that your child gets in many fights? |

| G2/G3 Mutual parent-child attachment at T5 (Parent report) | |||

| Child identification with parent (3) | .75 | Brook et al., 1990 | How much does your child admire or look up to you? |

| Child centeredness (5) | .80 | Schaefer, 1965 | Do you give your child a lot of care and attention? |

Note. G1= Generation 1, G2= Generation 2, G3= Generation 3; T1=Time 1, T2=Time 2, T3=Time 3, T4=Time 4, T5=Time 5. All measures were obtained from the G2 participant’s report.

Analytic plan

We used Mplus to perform structural equation modeling (SEM) (Muthén, 1998–2004). Following Newcomb and Bentler (1988), we partialed out the effects of gender, ethnicity, and SES. We used SAS to compute the partial covariance matrix presented in Appendix A.

Appendix.

A. Partial covariance matrices between variables controlling for gender, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status.

| Aggression T1 |

Theft & vandalism T1 |

Tobacco use T1 |

Marijuana use T1 |

Identification with parents |

Time spent with mother |

Time spent with father |

Parental Warmth |

Aggression T3–T4 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aggression T1 | 5.15 | ||||||||

| Theft & vandalism T1 | 5.05 | 16.96 | |||||||

| Tobacco use T1 | 0.56 | 1.35 | 0.55 | ||||||

| Marijuana use T1 | 0.49 | 1.00 | 0.22 | 0.43 | |||||

| Identification with parents | −0.49 | −1.59 | −0.42 | −0.13 | 29.86 | ||||

| Time spent with mother | −0.28 | −0.84 | −0.02 | −0.04 | 5.95 | 10.45 | |||

| Time spent with father | −0.35 | −1.01 | −0.10 | −0.02 | 5.15 | 0.78 | 6.20 | ||

| Parental Warmth | −1.70 | −5.65 | −0.85 | −0.31 | 41.86 | 12.92 | 9.94 | 124.52 | |

| Aggression T3–T4 | 1.46 | 2.96 | 0.30 | 0.53 | −4.07 | −1.26 | −1.46 | −5.26 | 20.39 |

| Theft & vandalism T3–T4 | 0.12 | 5.52 | 0.73 | 0.71 | −10.13 | −4.65 | −1.18 | −16.78 | 22.45 |

| Marijuana use T3–T4 | 0.54 | 1.39 | 0.15 | 0.18 | −1.55 | −0.53 | −0.65 | −2.14 | 4.70 |

| Tobacco use T3–T4 | 0.28 | 0.99 | 0.20 | 0.25 | 0.13 | −0.21 | −0.13 | −1.19 | 3.04 |

| Child’s delinquency | 0.45 | 0.45 | 0.14 | 0.07 | −0.47 | −0.12 | 0.11 | −1.68 | 1.25 |

| Child’s aggression | 0.53 | 0.59 | 0.28 | −0.00 | −0.49 | 0.14 | −0.04 | −2.34 | 2.01 |

| Child identification with parents | 0.23 | −0.77 | −0.09 | −0.04 | 2.68 | 1.28 | 0.24 | 4.78 | −0.69 |

| Child centeredness | 0.19 | −0.37 | −0.29 | −0.12 | 2.50 | 1.79 | −0.47 | 4.57 | −0.64 |

| Theft & vandalism T3–T4 |

Marijuana use T3–T4 |

Tobacco use T3– T4 |

Child’s delinquency |

Child’s aggression |

Child identification with parents |

Child centeredness |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theft & vandalism T3–T4 | 67.82 | ||||||

| Marijuana use T3–T4 | 11.72 | 5.99 | |||||

| Tobacco use T3–T4 | 8.29 | 2.62 | 5.60 | ||||

| Child’s delinquency | 2.63 | 0.60 | 0.37 | 1.58 | |||

| Child’s aggression | 4.97 | 1.02 | 0.32 | 2.35 | 8.76 | ||

| Child identification with parents | −3.18 | −0.61 | −0.30 | −0.67 | −1.39 | 4.62 | |

| Child centeredness | −3.86 | −0.42 | −0.38 | −1.06 | −1.52 | 3.14 | 9.00 |

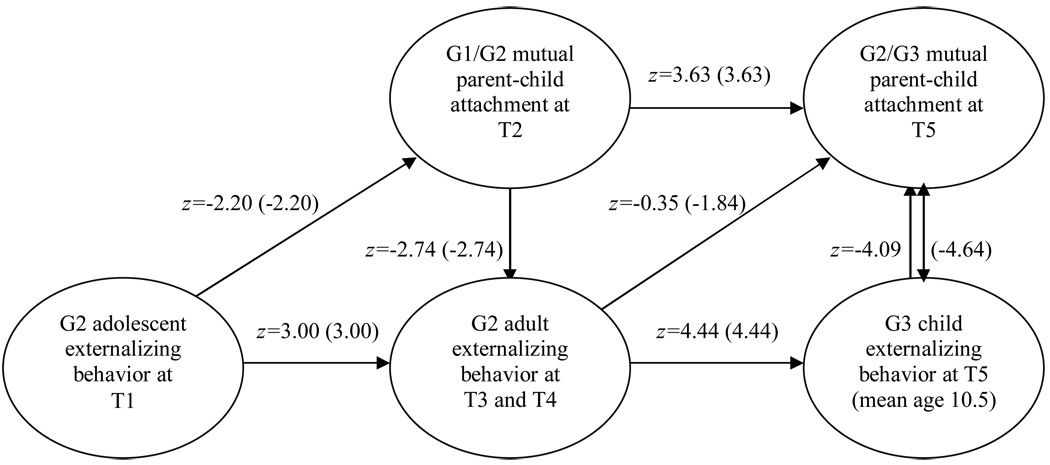

We used the Mplus Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) to assess the fit of the principal model and one alternative model. For the CFI, values between 0.90 and 1.0 indicate a good fit (Muthén, 1998–2004). A total effect analysis was performed on each latent construct related to the G2/G3 mutual parent-child attachment at T5. The total effect of a latent construct consists of the sum of the direct and indirect effects on the dependent variable. The z-statistics of the standardized total effects analyses are reported in Table 2. The alternative model had a bi-directional association between G3 child externalizing behavior and G2/G3 mutual parent-child attachment at T5. The z statistics for the alternative model are presented in parentheses in Figure 2.

Table 2.

Standardized Total Effect (z-statistic) on G2/G3 Mutual Parent-child Attachment at T5 (Parent Report)

| Latent variables | G2/G3 Mutual parent-child attachment at T5 (Parent report) |

|---|---|

| G2 Adolescent externalizing behavior at T1 | −2.52** |

| G1/G2 Mutual parent-child attachment at T2 | 4.16*** |

| G2 Adult externalizing behavior at T3 and T4 | −1.84* |

| G3 Child externalizing behavior at T5 (Parent report) | −4.09*** |

Note. G1= Generation 1, G2= Generation 2, G3= Generation 3; T1=Time 1, T2=Time 2, T3=Time 3, T4=Time 4, T5=Time 5. Gender, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status were statistically controlled.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Figure 2.

Estimated model: Standardized pathways (z-statistic). CFI=0.97; RMSEA=0.04. Gender, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status were statistically controlled. G1= Generation 1, G2= Generation 2, G3= Generation 3. T1=Time 1, T2=Time 2, T3=Time 3, T4=Time 4, T5=Time 5. Mean age of respondents at T1=14.1, at T2=19.2, at T3=24.4, at T4=26.1, at T5=32.3; Mean age of G3 children at T5=10.5.

Missing data

Eighty two percent of the participants provided complete data on all 15 of the variables in the present study. Half of the 15 variables had data for 93% or more of the respondents. Mplus automatically adjusts for missing data.

Results

We tested the measurement model, as well as the structural model, controlling for the participants’ gender, ethnicity, and SES. For both the principal model and the alternative model, all factor loadings were significant (p<0.01) with CFI=0.97 and RMSEA=0.04. For the structural model, the associated z-statistics for the sample are presented in Figure 2.

Our findings indicate that the externalizing behavior of the participants’ early adolescence was negatively related to the mutual attachment with participants’ parents (z = − 2.20), which in turn, was negatively associated with the externalizing behavior of the participants in adulthood (z = − 2.74). Externalizing behavior during the participant’s early adolescence was also directly associated with externalizing behavior during the participant’s adulthood (z =3.00), which in turn, was associated with the externalizing behavior of the participant’s child (z =4.44). In addition, we also found that: 1) the G1/G2 mutual parent-child attachment relationship was related to the G2/G3 mutual parent-child attachment relationship (z = 3.63); 2) the G3 externalizing behavior was negatively associated with G2/G3 mutual parent-child attachment (z = −4.09); and 3) there was no significant direct association between externalizing behavior in adulthood and G2/G3mutual parent-child attachment after G3 externalizing behavior is controlled (z =-0.35).

In the alternative model, the z statistic of the path from G2 adult externalizing behavior at T3 and T4 changed from the non-significant value of −0.35 to −1.84, which approached significance. The z statistic for the bidirectional association between G3 child externalizing behavior at T5 and G2/G3 parent child mutual attachment at T5 was –4.64. Other z statistics were not different.

Table 2 presents the standardized total effects of the proposed latent variables on the G2/G3 mutual parent-child attachment relationship. The z -values of the total effects of G2 externalizing behavior in early adolescence, the G1/G2 mutual parent-child attachment, and the G3 externalizing behavior on G2/G3 mutual parent-child attachment were all statistically significant (p<0.01). The z-value of the total effects of the externalizing behavior in adulthood was not statistically significant at the of 0.05 level of significance.

Discussion

Overall, the findings support our hypotheses. (1) Specifically, G2 externalizing behavior in adolescence had a direct negative association with the G1/G2 attachment relationship. Correspondingly, the G3 child’s externalizing behavior had a direct negative association with the G2/G3 attachment relationship. (2) There was also continuity in the reporting of externalizing behavior both within (G2) and across generations (G2 to G3). (3) Furthermore, there was intergenerational transmission of the mutual parent-child attachment relationship from G1/G2 to G2/G3. (4) Additionally, the G1/G2 mutual attachment relationship was negatively related to G2 externalizing in adulthood. (5) We found that G2 externalizing behavior had a mediated association with the G2/G3 mutual attachment relationship through the G3 child’s externalizing behavior.

The finding that the G3 child’s externalizing behavior has a negative influence on the G2/G3 mutual attachment relationship is consistent with Belsky’s process model of parenting (Belsky, 1984) in which the characteristics of the child contribute to individual differences in parental functioning. Our results suggest that children who are delinquent, aggressive, and use substances have difficulties in developing or maintaining a close bond with their parents and that, conversely, children who display positive behavior are more likely to have a closer parent-child bond. These results support the findings of Kerr and colleagues (Kerr et al., 2009).

Previous research has indicated that there is continuity in externalizing behavior from G2 adolescence to adulthood (Masten et al., 2005; Neppl et al., 2009). Our findings are consistent with these results. We also found continuity in externalizing behavior across generations, from G2 parents to G3 children. These findings are consistent with Kerr et al. (2009) and Thornberry et al. (2003) in their studies of fathers and their children. As noted in the introduction, the transmission of externalizing behavior from G2 parents in adulthood to G3 children may be due to modeling and/or processes of identification, or to genetic transmission.

Our findings indicate that the G1 attachment relationship with the G2 is mirrored in the G2 relationship with the G3 child. The results regarding the continuity of the mutual parent-child attachment relationship are consistent with several researchers (Belsky et al., 2005; Kerr et al., 2009; Kovan et al., 2009). One interpretation of these findings is that children learn specific parenting practices, which they then use with their own children. A second possibility is that the emotional attachment or, conversely, distance between parent and child is replicated in the G2 relationship with their own children. The findings are maintained with control on age and ethnicity. Regarding the family’s socioeconomic status, researchers have found that SES influences the quality of the parent-child relationship, and that socioeconomic status is transmitted from parents to their offspring (Conger & Donnellan, 2007). Nevertheless, our findings indicated that there was continuity in the mutual parent-child attachment relationship across generations even with control on socioeconomic status. While we have identified a direct path from the G1/G2 parent-child attachment relationship in one generation to the G2/G3 parent-child attachment relationship in the next, there is also an indirect path in which the association between these variables is partially mediated by G2 externalizing behavior in adulthood and G3 externalizing behavior in childhood. Although the findings point to intergenerational continuity in the mutual parent-child attachment relationship, there is some evidence for intergenerational discontinuity as well (Conger, Belsky, & Capaldi, 2009).

A close mutual attachment relationship between the G1 parent and the G2 child is related to lower levels of subsequent adult externalizing behavior. These results are in accord with earlier findings of Chen and Kaplan (2001) and Brook, Whiteman, and Zheng (2002). Consequently, prevention programs aimed at increasing the parent-child bond may result in a decrease in externalizing behavior. Furthermore, it may be that strengthening the mutual attachment relationship in one generation would result in perpetuation of positive results in future generations.

As noted earlier, we also assessed an alternative model in which there was a bidirectional relationship between the G3 child’s externalizing behavior and the G2/G3 mutual parent-child attachment relationship (Kerr et al., 2009). The goodness of fit in the principal model did not differ appreciably from the alternative model.

Limitations

Despite its strengths, this study has some limitations. Though we have identified a number of longitudinal pathways between constructs, we are unable to draw causal conclusions regarding these relationships because of the observational nature of the study. Additionally, our data are based on self-reports rather than third-party measures. However, for each latent construct we combined several measures, which enhanced the reliability and validity of the latent construct. Our data also come from a single source, the G2 respondent. These results should be replicated using independent sources from each of the generations. Although the mutual attachment relationship and externalizing measures varied slightly at each wave, we were still able to identify intra- and inter-generational continuities in these variables. It is likely that future research with more consistent latent constructs over time would find even stronger paths than those found here. It is important to note that the relationship between the G3 child’s externalizing behavior and the G2/G3 mutual parent-child attachment relationship may be reciprocal (Kerr et al., 2009). We chose to discuss in detail the principal model, as opposed to the alternative model, as we wished to examine the relationship of externalizing behavior in one generation as it affects the mutual parent-child attachment relationship in the next. Additionally, we did not take into consideration possible genetic effects. Future work should focus on the interplay between genes and environments that may underlie the intergenerational transmission of the behaviors, and the mutual parent-child attachment relationships which result from problem behaviors in both the parent and the child.

Despite these limitations, the study supports and extends the literature in a number of ways. First, unlike most research that focuses on development at one point in time, we assess several developmental stages covering a span of up to 20 years. The prospective nature of the data allowed us to go beyond a cross-sectional analysis and to consider the temporal sequencing of variables. Second, a major contribution of the paper is a set of findings relating earlier manifestations of the externalizing behaviors in G2 to the mutual attachment relationship between G1 and G2, and ultimately, to the mutual attachment relationship between G2 and G3. Third, in contrast to the limited research that has looked at the effect of the child’s behavior on the parent-child relationship, our study examined these pathways in a low SES sample.

This study also has implications for intervention. Kumpfer and Alvarado (2003) suggested in their Principles of Effective Family-Focused Interventions that intervention programs for dysfunctional families should focus on family processes rather than addressing parental and child problems individually. Our finding that the G3 child’s externalizing behavior was related to the G2–G3 attachment relationship, and that it mediated the path from G2 externalizing behavior to the G2–G3 attachment relationship, emphasizes the contribution of the child to relationship problems in a low-SES urban sample and suggests that interventions with similar populations may benefit from working with the child on pre-existing externalizing problems in addition to improving family processes. Furthermore, when addressing the child’s externalizing behavior, our findings suggest that is important to do so as early as possible, as externalizing behaviors in adolescence which are negatively related to parent-child attachment relationships for one generation can persist into adulthood and negatively impact relationships with the next generation.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a research scientist award [DA00244] and a research grant [DA005702] from the National Institutes of Drug Abuse, and by a research grant from the National Cancer Institute [CA084063]. The authors thank Dr. Martin Whiteman and David Brook, M.D. for critical review of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Judith S. Brook, Email: judith.brook@nyumc.org, Department of Psychiatry, New York University School of Medicine, New York, NY 10016.

Jung Yeon Lee, Department of Psychiatry, New York University School of Medicine, New York, NY 10016.

Stephen J. Finch, Department of Applied Mathematics & Statistics, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, NY

Elaine N. Brown, Department of Psychiatry, New York University School of Medicine, New York, NY 10016

References

- Achenbach TM. The classification of children’s psychiatric symptoms: A factor-analytic study. Psychological Monographs. 1966;80 doi: 10.1037/h0093906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist 4–18 and 1991 profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Avgar A, Bronfenbrenner U, Henderson CR., Jr Socialization practices of parents, teachers and peers in Israel: Kibbutz, Moshav, and City. Child Development. 1977;48:1219–1227. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J. The determinants of parenting: A process model. Child Development. 1984;55:83–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1984.tb00275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Jaffee SR, Sligo J, Woodward L, Silva PA. Intergenerational transmission of warm-sensitive-stimulating parenting: A prospective study of mothers and fathers of 3-year-olds. Child Development. 2005;76:384–396. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00852.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Brook DW, De La Rosa M, Duque LF, Rodriguez E, Montoya ID, et al. Pathways to marijuana use among adolescents: Cultural/ecological, family, peer, and personality influences. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1998;37:759–766. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Brook DW, De La Rosa M, Whiteman M, Johnson E, Montoya I. Adolescent illegal drug use: The impact of personality, family, and environmental factors. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2001;24:183–203. doi: 10.1023/a:1010714715534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Brook DW, Gordon AS, Whiteman M, Cohen P. The psychosocial etiology of adolescent drug use: A family interactional approach. Genetic, Social, and General Psychology Monographs. 1990;116:111–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Brook DW, Zhang C. Psychosocial predictors of nicotine dependence in Black and Puerto Rican young adults. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2008;10:959–967. doi: 10.1080/14622200802092515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Pahl K, Ning Y. Peer and parent influences on longitudinal trajectories of smoking among African-Americans and Puerto Ricans. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2006;8:639–651. doi: 10.1080/14622200600789627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Whiteman M, Finch S, Cohen P. Longitudinally foretelling drug use in the late twenties: Adolescent personality and social- environmental antecedents. Journal of Genetic Psychology. 2000;161:37–51. doi: 10.1080/00221320009596693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Whiteman M, Zheng L. Intergenerational transmission of risks for problem behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2002;30:65–76. doi: 10.1023/a:1014283116104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z-Y, Kaplan HB. Intergenerational transmission of constructive parenting. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;63:17–31. [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Belsky J, Capaldi DM. The intergenerational transmission of parenting: Closing comments for the special section. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45:1276–1283. doi: 10.1037/a0016911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Conger KJ, Martin MJ. Socioeconomic status, family processes, and individual development. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010;72:685–704. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00725.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Donnellan MB. An interactionist perspective on the socioeconomic context of human development. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:175–199. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Neppl T, Kim KJ, Scaramella L. Angry and aggressive behavior across three generations: A prospective, longitudinal study of parents and children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2003;31:143–160. doi: 10.1023/a:1022570107457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dogan SJ, Conger RD, Kim KJ, Masyn KE. Cognitive and parenting pathways in the transmission of antisocial behavior from parents to adolescents. Child Development. 2007;78:335–349. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Englund MM, Egeland B, Oliva EM, Collins WA. Childhood and adolescent predictors of heavy drinking and alcohol use disorders in early adulthood: A longitudinal development analysis. Addiction. 2008;103:23–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02174.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fite PJ, Colder CR, Lochman JE, Wells KC. The mutual influence of parenting and boys’ externalizing behavior problems. Applied Developmental Psychology. 2006;27:151–164. [Google Scholar]

- Gold M. Undetected delinquent behavior. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 1966;3:27–46. [Google Scholar]

- Hicks BM, South SC, DiRago AC, Iacono WG, McGue M. Environmental adversity and increasing genetic risk for externalizing disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2009;66:640–648. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huizinga DH, Menard S, Elliott DS. Delinquency and drug use: Temporal and developmental patterns. Justice Quarterly. 1989;6:419–455. [Google Scholar]

- Jokela M, Ferrie J, Kivimäki M. Childhood problem behaviors and death by midlife: The British National Child Development Study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;48:19–24. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31818b1c76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr DCR, Capaldi DM, Pears KC, Owen LD. A prospective three generational study of fathers’ constructive parenting: Influences from family of origin, adolescent adjustment, and offspring temperament. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45:1257–1275. doi: 10.1037/a0015863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr M, Stattin H. Parenting of adolescents: Action or reaction? In: Crouter AC, Booth A, editors. Children’s influence on family dynamics: The neglected side of family relationships. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2003. pp. 121–152. [Google Scholar]

- Kogan LS, Smith J, Jenkins S. Ecological validity of indicator data as predictors of survey findings. Journal of Social Service Research. 1977;1:117–132. [Google Scholar]

- Kovan NM, Chung AL, Sroufe LA. The intergenerational continuity of observed early parenting: A prospective, longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45:1205–1213. doi: 10.1037/a0016542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumpfer KL, Alvarado R. Family-strengthening approaches for the prevention of youth problem behaviors. American Psychologist. 2003;58:457–465. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.58.6-7.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS, Latendresse SJ. Comparable “risks” at the socioeconomic status extremes: Preadolescents’ perceptions of parenting. Development and Psychopathology. 2005;17:207–230. doi: 10.1017/s095457940505011x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Roisman GI, Long JD, Burt KB, Obradović J, Riley JR, et al. Developmental cascades: Linking academic achievement and externalizing and internalizing symptoms over 20 years. Developmental Psychology. 2005;41:733–746. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.41.5.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE. Adolescence-limited and life-course-persistent antisocial behavior: A developmental taxonomy. Psychological Review. 1993;100:674–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén BO. Mplus technical appendices. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2004. [Google Scholar]

- Neppl TK, Conger RD, Scaramella LV, Ontai LL. Intergenerational continuity in parenting behavior: Mediating pathways and child effects. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45:1241–1256. doi: 10.1037/a0014850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb MD, Bentler PM. Impact of adolescent drug use and social support on problems of young adults: A longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1988;97:64–75. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.97.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petty CR, Rosenbaum JF, Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Henin A, Hubley S, LaCasse S, et al. The child behavior checklist broad-band scales predict subsequent psychopathology: A 5-year follow-up. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2008;22:532–539. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer ES. Children’s report of parental behavior: An inventory. Child Development. 1965;36:413–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieving RE, McNeely CS, Blum RWm. Maternal expectations, mother-child connectedness, and adolescent sexual debut. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 2000;154:809–816. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.154.8.809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siqueira LM, Brook JS. Tobacco use as a predictor of illicit drug use and drug-related problems in Colombian youth. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2003;32:50–57. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00534-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornberry TP, Freeman-Gallant A, Lizotte AJ, Krohn MD, Smith CA. Linked lives: The intergenerational transmission of antisocial behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2003;31:171–184. doi: 10.1023/a:1022574208366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiesner M, Vondracek FW, Capaldi DM, Porfeli E. Childhood and adolescent predictors of early adult career pathways. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2003;63:305–328. [Google Scholar]