Abstract

We examined whether children's changes in salivary habituation to food vary based on weight status and/or allocating attention to a task. Children (31 non-overweight and 26 obese, ages 9–12 year) were presented with nine trials of a food stimulus and either listened to an audiobook (attention-demanding) or white noise (no-attention control). The salivary pattern differed significantly by weight status but not by condition or a condition by weight status interaction. This is the first study of salivary habituation in obese children; findings dovetail with an emerging set of evidence that obese individuals display distinctive biological responses to food.

Keywords: Obesity, Children, Salivation, Habituation, Food

Introduction

Cephalic phase response (CPR), which includes increases in saliva, heart rate, temperature, and gastric activity (Nederkoorn, Smulders, & Jansen, 2000), represents the first response from the body in preparation for eating (Powley & Berthoud, 1985). CPR is associated with the initiation and termination of an eating episode and is implicated in influencing the total amount of food that an individual consumes within a meal (Nederkoorn et al., 2000). Accordingly, understanding the role of CPR in food ingestion may help identify some of the central factors leading to overconsumption in children.

Salivary flow, a primary component of CPR, is considered a valid measure of physiological hunger (Wooley & Wooley, 1973), as it is directly proportional to the duration of food deprivation (Wooley & Wooley, 1976). In addition, data in non-human primates and humans show that repeated presentations of the same food (e.g., during a given meal) lead to a decrease in salivation (Epstein, Saad, Giacomelli, & Roemmich, 2005), resulting in satiation for that food (Swithers & Hall, 1994) and the termination of an eating episode (Wisniewski, Epstein, & Caggiula, 1992). This general process of decreasing responsiveness after repeated exposures to a stimulus is referred to as habituation and is a common biological process found across species. Through habituation, humans and animals learn to ignore stimuli that have lost novelty or meaning, allowing them to attend to stimuli that are more important (Stephenson & Siddle, 1983).

Research applying this habituation paradigm to specific eating- and weight-related disorders (e.g., bulimia nervosa [BN], binge eating disorder, obesity) suggests that disruptions in habituation lead to an extended eating episode and possibly overconsumption (Epstein, Temple, Roemmich, & Bouton, 2009). Specifically, habituation research evaluating salivary response in obese (Ob) adults (Bond & Raynor, 2009; Bond, Raynor, McCaffery, & Wing, 2010; Epstein, Paluch, & Coleman, 1996), and women with BN (Wisniewski, Epstein, Marcus, & Kaye, 1997) report abnormal extended patterns of habituation (slower habituation) in response to food cues as compared to individuals without eating disturbances. In addition, research using instrumental responding for food also showed slower habituation for Ob vs. non-overweight (N-OW) children (Temple, Giacomelli, Roemmich, & Epstein, 2007). Studies have also shown that competing attention-demanding activities interfere with the habituation process in N-OW children. For example, Epstein and colleagues (2005) conducted two experiments to determine whether children's salivary response to food stimuli is disrupted by allocating attention to non-food-related tasks during an eating episode. The competing task varied in attentional demand (e.g., listening to an audiobook or white noise), and results indicated that in both experiments, attentional competition between non-food and food stimuli influenced the pattern of habituation. In particular, tasks requiring a great deal of attention impeded habituation, whereas tasks involving moderate or no attention protracted the habituation process. This finding is particularly notable given that the most common attention-demanding activities for youth in our current technological-based environment are media-based (e.g., watching television and playing video games). While studies have demonstrated persuasive evidence for a relation between media use and obesity (Jordan & Robinson, 2008), the specific mechanisms underlying this relation are not well understood. One possibility is that Ob children's increased consumption of food while watching television is due to a disruption in the habituation process (Temple, Giacomelli, Kent, Roemmich, & Epstein, 2007).

Taken together, existing findings suggest that a slower rate of salivary habituation to repeated presentations of food stimuli may be involved as a causal or maintaining factor in obesity among children. To date, no studies have evaluated this theory, and the salivary habituation patterns of Ob vs. N-OW children are currently unknown. Thus, the purpose of the present study was twofold. The first goal was to compare salivary patterns in Ob and N-OW children in response to food. The second goal was to explore whether salivary habituation patterns in Ob children are disrupted by allocating attention to activities that require focus and recall. While this finding has been documented in N-OW children (Epstein et al., 2005), it is unknown whether it would extend to, or possibly be more pronounced in, Ob children.

Method

Participants

Participants were 57 children, ages 9–12 years: 31 within a N-OW range (Body Mass Index [BMI] less than the 85th percentile for age and sex), and 26 Ob children (BMI greater than 95th percentile for age and sex; Kuczmarski et al., 2000); they did significantly differ in BMI percentile [52.3 vs. 98.0, t(55) = –13.10, p < 0.0001]. The sample was 28.1% Non-Hispanic African American, 68.4% Non-Hispanic Caucasian, and 3.5% Non-Hispanic mixed race. The average child was 10.5 ± 1.2 years of age. The white noise (defined below) condition consisted of 26 children (11 Ob, 15 N-OW); 57.7% were female. The audiobook (defined below) condition consisted of 31 children (15 Ob, 16 N-OW); 45.2% were female.

Participants were recruited from the St. Louis metropolitan area using Washington University Volunteer for Health (a research participant registry), as well as posters and flyers placed throughout the community. Children were excluded based on responses within the phone screen if they: (1) were taking medications that could influence olfactory sensory responsiveness or appetite (e.g., methylphenidate); (2) had any conditions that could influence olfactory sensory responsiveness or appetite (e.g., upper respiratory illness, diabetes, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder [ADHD]); (3) were currently dieting, as this could alter responding to food cues (Tepper, 1992); (4) met criteria for a current psychological disorder or developmental disability; or (5) rated foods used in the experiment less than “moderately liked.”

Measures

Height and weight

Height (m) was assessed using a portable stadiometer (Seca, Hanover, MD). Weight (kg) was assessed using a lithium electronic scale (Homedics, Commerce Township, MI). Height and weight were converted to BMI (kg/m2) percentile (Kuczmarski et al., 2000).

Socioeconomic Status (SES)

The Hollingshead Socioeconomic Status Index (Hollingshead, 1975) self-report questionnaire was used to gather information regarding parental education level and occupational status, with questions added regarding child ethnicity and race.

Test Food Liking questionnaire (Epstein et al., 2005)

This was used to assess liking of the test food (i.e. French fries). It consists of a single, 5-point Likert-type question ranging from “do not like” to “like very much”.

Salivation

Whole mouth parotid salivary flow using the Strongin–Hinsie–Peck method (Peck, 1959) was utilized to measure habituation via salivation. Participants placed dental rolls (cylindrical, 7 mm diameter, 38 mm length; Richmond Dental, Charlotte, NC) under their tongue and on both the left and right sides of their mouth between the cheek and lower gum (three total rolls) for 1 min. Before the first trial, participants were instructed on behaviors that they should avoid while the dental rolls were in their mouth (e.g., swallowing saliva, chewing, moving the tongue). Salivation was calculated based on pre- and post-weights of dental rolls to 0.001 g on a Balance Adventurer™ Pro Scale AV213 (Ohaus, Pine Brook, NJ).

Olfactory functioning

The Olfactory Functions Test (Epstein et al., 2005) was used to determine if participants had adequate olfactory functioning. This task involved having participants close their eyes and report the distance from which they could smell an alcohol pad, starting at a distance of 29 cm.

Procedure

A brief phone screen with a parent was administered to determine if the child was eligible; if so, the family was scheduled for an experimental session and the child was randomized to either an audiobook (AB; attention task) or white noise (WN; a no-task control) condition. Participant instructions (given to parent) directed the child to refrain from eating the test food (i.e., French fries) on the day of testing and to fast for 3 h prior to the experimental session. On the day of testing, parents signed the consent form and completed the SES questionnaire. Children signed the assent form and were asked to recall foods consumed on the day of testing. We had 100% compliance for consented children and parents (i.e., they completed all child and parent measures). This list was used to confirm that the child had not eaten during the previous 3 h and that the test food had not been eaten on the day of the experiment. As with the Epstein et al. (2005) study, the attention tasks were three selections from a series of Bunnicula children's ABs (Howe & Garber, 1982, 1987, 1992). At the study site, children in the AB condition were given brief descriptions of each story and selected their most preferred story.

The experiment consisted of 11 habituation trials (i.e., 2 baseline practice trials followed by nine test trials). Total time for each participant was approximately 1.5 h. The food stimulus for each trial was 37 g of Burger King French fries served on a 9-inch paper plate and heated on high in the microwave oven for 25 s in a separate room. Each trial consisted of the participant smelling and looking at the test food for 1 min while it was held approximately 3 in. beneath the participant's nose. At the completion of the final experimental trials, salivation was measured using the Strongin-Hinsie Peck method (Peck, 1959) as described above. A high efficiency particle-arresting (HEPA) filter was used to reduce the likelihood that lingering odors from the test food would affect results between trials and between participants. Between each habituation trial, a 1-min intertrial interval occurred, during which children in both conditions listened to an auditory stimulus using a headphone. AB participants listened to a compact disc of their selected AB for sequential 1-min presentations and were asked to pay attention as they would be asked questions about it at the conclusion of the experiment. WN participants listened to a compact disc of WN and sat quietly for the same duration.

Post-experiment, participants in the AB condition completed a quiz consisting of multiple-choice questions about the AB story. Height and weight were measured, and the Olfactory Functions Test was conducted. All children were given a $25 gift card to Target® and debriefed about the purpose of the study. This study was reviewed and approved by the Human Studies Committee at Washington University School of Medicine.

Analytical plan

Data analyses were conducted using SPSS version 14.0 for Windows. Sample size was selected, using effect size estimates based on Epstein and colleagues’ (2005) study, to provide enough statistical power to detect a possible three-way interaction among weight, condition, and trials, in the ANCOVA described below. Differences in demographics and participant characteristics were compared by weight status (Ob vs. N-OW) and condition (AB vs. WN), and analyzed for relation to outcome (change in salivation pre-post). Group/condition differences were examined using independent sample t-tests for continuous variables, and chi-square tests for categorical variables; relation to outcome was examined by assessing the relation of each variable (using correlations, t-test or ANOVA) with the change in salivation (pre/post). Only baseline variables that were significantly related to the outcome variable were entered as covariates (Grouin, Day, & Lewis, 2004; Raab, Day, & Sales, 2000).

Blocked trials were computed by averaging values across blocks of trials (e.g., mean of trials 1 and 2 = block 1, etc.), in pairs except the final blocked trial, where three trials were combined, resulting in a total of one baseline block and four blocked trials. Blocked trials were analyzed using repeated measures ANCOVA where weight status and condition were entered as the between-subject factors and blocked trials as the within-subject repeated measures factor. Two covariates – baseline salivation and the Olfactory Functions Test – were included in the model, and salivation means adjusted for these covariates are presented below. Planned simple contrasts and paired sample t-tests were used to evaluate the pattern of responding and to determine if habituation had occurred at the end of the experiment. First, paired sample t-tests between the baseline and initial blocked trial were conducted to determine if there was a reliable increase in response to the food stimulus. Habituation was then determined by comparing baseline salivation with the salivation at the final blocked trial; means that did not significantly differ from one another indicated habituation.

Results

Average baseline salivation was 1.57 ± 1.15 g, and participants rated the test food as moderately to highly liked (4.5 ± 0.8, on a scale from 1 to 5). As mentioned above, participants assigned to the AB condition completed a quiz at the end of the study to verify that they had attended to their chosen story. Of the 31 participants, 27 (87%) answered all questions correctly. Participants that missed questions were retained in the analyses, as excluding them did not change the outcome. When comparing the sample by weight status, the N-OW group performed significantly better on the olfactory test [t(55) = 2.39, p = 0.02] (although all children met inclusion criteria on this measure – i.e., having adequate olfactory functioning) and were significantly more likely to be Caucasian [χ2(2, N = 56) = 13.98, p < 0.001]. There were no significant differences by condition, and no other significant differences on baseline or demographic variables were found.

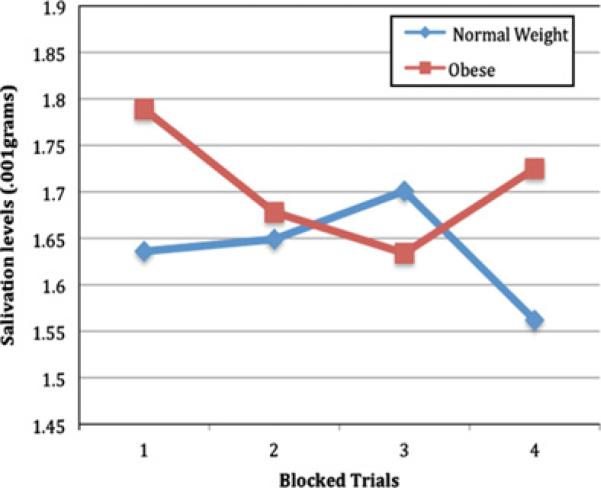

There was a significant main effect of blocked trials [F(4,46) = 7.24, p = 0.001], and paired t-tests confirmed that there was a significant increase in responding to the food stimulus from the baseline (no food stimulus presented) blocked trial to the first (food stimulus presented) block [t(55) = 2.40, p = 0.02]. There was a significant interaction between weight status and blocked trials (See Fig. 1) [F(4,46) = 3.61, p = 0.019, η2 = 0.19]. Specifically, after the increase from baseline (Block 1 M = 1.79 g, SD = 1.15), the Ob group showed a pattern of reduced salivation for the 2nd (M = 1.68 g, SD = 1.07) and 3rd blocks (M = 1.63 g, SD = 1.00), followed by a large increase in salivation (Block 4 M = 1.73 g, SD = 1.05), so that the change from baseline to the final block was not significant (p = 0.122; habituation occurred), whereas the N-OW group showed (after the increase [Block 1 M = 1.64 g, SD = 1.02] from baseline), a small increase in salivation through the 2nd (M = 1.65 g, SD = 0.93) and 3rd (M = 1.70 g, SD = 0.91) blocks, followed by a large reduction (Block 4 M = 1.56 g, SD = 1.02) in salivation so that the change in salivation from baseline to the final block was significant (p = 0.03; habituation did not occur). A two-way interaction between attention condition and blocked trials was non-significant [F(4,46) = 1.25, p = 0.31, η2 = 0.08]. A three-way interaction among condition, weight status, and blocked trials was also found to be non-significant [F(4,46) = 0.04, p = 0.77, η2 = 0.02]. To determine whether there was an attention effect in the Ob sample, salivation patterns were analyzed separately by condition within the Ob sample and within the N-OW sample, and these were also non-significant (p's > 0.1).

Fig. 1.

Two-way interaction between weight status and blocked trails.

Discussion

This is the first study to evaluate salivary habituation patterns among Ob and N-OW children. Results demonstrated that salivation patterns varied by weight status, as N-OW children habituated to food cues whereas Ob children did not. These findings suggest that N-OW and Ob children differ in their CPR to food.

The salivation pattern observed in the Ob group (no habituation) is similar to patterns previously found for Ob adults (Bond et al., 2010; Bond & Raynor, 2009; Epstein et al., 1996) and women with BN (Wisniewski et al., 1997). The lack of effect of the attention condition is surprising given that five previous studies have demonstrated it (Epstein, Mitchell, & Caggiula, 1993; Epstein, Myers, Raynor, & Saelens, 1997; Epstein, Rodefer, Wisniewski, & Caggiula, 1992; Epstein et al., 2005; Temple, Giacomelli, Roemmich, et al., 2007). Our study was the first conducted outside of a controlled feeding laboratory – a primary difference from the others. And, despite the care taken to have relatively controlled conditions (e.g., HEPA air purifying system, prompt removal of food stimulus after each trial, use of carefully-timed prerecorded instructions for participants to insert/remove cotton rolls at 1-min intervals), our testing environment may have simulated more of a naturalistic setting. Thus, the lack of findings may be due to some unidentified factors in the environment, or other unknown aspects of measurement. Other limitations include few self-report measures (e.g., we did not collect data on the frequency with which the participants typically consumed French fries and we did not assess whether the females in the study had reached puberty, both of which could impact salivary flow). A specific strength of the current study is the novel application of a habituation paradigm in a sample of Ob children.

In terms of future directions, a major gap in the literature is in understanding the causes of the habituation patterns observed in Ob children and eating disordered populations. From an environmental perspective, research on attentional bias and cue sensitivity may provide some clues. Habituation is a simple form of learning in which animals filter out unimportant information so that they can focus attention on the most central features of the environment. Research has shown that Ob adults (King, Polivy, & Herman, 1991), overweight children (Soetens & Braet, 2007) and individuals with eating disorders (Dobson & Dozois, 2002) have an attentional bias toward food-related information. These findings suggest that individuals with weight-related disorders are more focused on food-related cues and hence may not habituate because food-related information remains of high importance as compared to other aspects of the environment.

The classical conditioning model of overeating (i.e., cue reactivity) posited by Jansen (1998) states that after repeated pairings between food and a particular cue (e.g., sight, smell, or taste of food), the cue will elicit the same food effects (i.e., initiation of the CPR), which are interpreted by the individual as cravings. Interestingly, in a laboratory study, larger meals were associated with higher rates of salivation immediately following food exposure, particularly so among overweight children (Jansen et al., 2003), suggesting that salivary flow (a component of the CPR) may depend on meal size. If the positive energy balance that defines obesity results from repeated episodes of overeating, perhaps over time these pairings (between food cues, large meals and salivation) result in food cues (conditioned stimulus) eliciting an extended salivary response (conditioned response).

In summary, it is well documented that approximately half of Ob children become Ob adults (Whitaker, Wright, Pepe, Seidel, & Dietz, 1997). Given the poor long-term success of weight loss treatments for adults with obesity (Wilson, 1994), it is imperative that we intervene before their obesity tracks into adulthood. The present findings suggest that biological response to food may play an important role in explaining the positive energy balance that characterizes obesity, as salivation may be an internal signal of hunger. The increased salivary response in the presence of food may result in increased hunger for Ob children, further exacerbating their obesity. Ob children may not be able to rely on these cues to regulate their food intake, which, in turn, could help to explain the refractory nature of this condition. Prospective studies are needed to determine whether extended habituation responses are a risk factor for obesity or are a result of obesity. Recent data suggest that this abnormal salivation pattern may be an early marker of individuals who go onto develop obesity and/or other eating disturbances (Epstein, Robinson, Roemmich, & Marusewski, 2011). However, future research is needed to replicate these findings and to evaluate whether the lack of habitation among Ob children is in any way facilitating the maintenance of their obesity. If confirmed, these findings could provide a new understanding of how obesity develops and is maintained, and could potentially offer novel strategies to improve long-term success in the treatment of obesity.

Footnotes

This research was based on the first author's doctoral dissertation and was funded by a Washington University Dissertation Fellowship, a Longer Life Foundation Grant (2005-003) and Dr. Wilfley's Career Development Award (K24 MH070446). Dr. Stein was also supported by NIH Grants KL2RR024994 and UL1RR024992. We would like to thank Dr. Leonard Epstein for his comments on earlier drafts of this manuscript. We would also like to thank Dr. Jennifer Temple for her assistance in training and providing materials for this study.

References

- Bond DS, Raynor HA, McCaffery JM, Wing RR. Salivary habituation to food stimuli in successful weight loss maintainers, obese and normal weight adults. International Journal of Obesity. 2010;34:593–596. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2009.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond DS, Raynor HA. Differences in salivary habituation to a taste stimulus in bariatric surgery candidates and normal weight controls. Obesity Surgery. 2009;19:873–878. doi: 10.1007/s11695-009-9861-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobson KS, Dozois DJA. Attentional biases in eating disorders. A meta-analytic review of Stroop performance. Clinical Psychology Review. 2002;23:1001–1022. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein LH, Mitchell SL, Caggiula AR. The effect of subjective and physiological arousal on dishabituation of salivation. Physiology and Behavior. 1993;53(3):593–597. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(93)90158-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein LH, Myers MD, Raynor HA, Saelens BE. Treatment of pediatric obesity. Pediatrics. 1997;101:554–570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein LH, Paluch R, Coleman KJ. Differences in salivation to repeated food cues in obese and non obese women. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1996;58:160–164. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199603000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein LH, Robinson JL, Roemmich JN, Marusewski A. Slow rates of habituation predict greater weight and zBMI gains over 12 months in lean children. Eating Behaviour. 2011;12(3):214–218. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein LH, Rodefer JS, Wisniewski L, Caggiula AR. Habituation and dishabituation of human salivary response. Physiology and Behavior. 1992;51:945–950. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(92)90075-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein LH, Saad FG, Giacomelli AM, Roemmich JM. Effects of allocation on habituation to olfactory and visual food stimuli in children. Physiology & Behavior. 2005;84:313–319. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein LH, Temple JL, Roemmich JN, Bouton ME. Habituation as a determinant of human food intake. Psychological Review. 2009;116:384–407. doi: 10.1037/a0015074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grouin JM, Day S, Lewis J. Adjustment for baseline covariates. An introductory note. Statistics in Medicine. 2004;23:697–699. doi: 10.1002/sim.1646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB. Four factor index of social status. Yale University; New Haven, CT: 1975. Unpublished manuscript Available at: < http://www.yale.edu/sociology/faculty/docs/hollingshead_socStat4factor.pdf>. [Google Scholar]

- Howe J, Garber V. Nighty-nightmare. Random House Audio Publishing Group; New York (NY): 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Howe J, Garber V. Howliday inn. Random House; New York (NY): 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Howe J, Garber V. Return to Howliday Inn. Random House Audio Publishing Group; New York (NY): 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen A. A learning model of binge eating. Cue reactivity and cue exposure. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1998;36(3):257–272. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(98)00055-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen A, Theunissen N, Slechten K, Nederkoorn C, Boon B, Mulkens S, et al. Overweight children overeat after exposure to food cues. Eating Behaviors. 2003;4(2):197–209. doi: 10.1016/S1471-0153(03)00011-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan A, Robinson T. Children's television viewing, and weight status. Summary and recommendations from an expert panel meeting. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2008;615:119–132. [Google Scholar]

- King GA, Polivy J, Herman CP. Cognitive aspects of dietary restraint. Effects on person memory. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1991;10:313–321. [Google Scholar]

- Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Grummer-Strawn LM, Flegal KM, Guo SS, Wei R, et al. CDC growth charts. United States. Advanced Data. 2000;314:1–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nederkoorn C, Smulders FTY, Jansen A. Cephalic phase responses, craving and food intake in normal subjects. Appetite. 2000;35:45–55. doi: 10.1006/appe.2000.0328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peck RE. The SHP test-an aid in the detection and measurement of depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1959;1:35–40. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1959.03590010051006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powley TL, Berthoud H. Diet and cephalic phase insulin responses. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1985;42:991–1002. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/42.5.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raab GM, Day S, Sales J. How to select covariates to include in the analysis of a clinical trial. Controlled Clinical Trials. 2000;21:330–342. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(00)00061-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soetens B, Braet C. Information processing of food cues in overweight and normal weight adolescents. British Journal of Health Psychology. 2007;12:285–304. doi: 10.1348/135910706X107604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson D, Siddle DA. Theories of habituation. In: Siddle D, editor. Orienting and Habituation. Perspectives in Human Research. Wiley; New York: 1983. pp. 183–236. [Google Scholar]

- Swithers SE, Hall WG. Does oral experience terminate ingestion? Appetite. 1994;23:113–138. doi: 10.1006/appe.1994.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temple JL, Giacomelli AM, Kent KM, Roemmich JN, Epstein LH. Television watching increases motivated responding for food and energy intake in children. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2007;85(2):355–361. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.2.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temple JL, Giacomelli AM, Roemmich JN, Epstein LH. Overweight children habituate slower than non-overweight children to food. Physiology and Behavior. 2007;91:250–254. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tepper BJ. Dietary restraint and responsiveness to sensory-based food cues as measured by cephalic phase salivation and sensory specific satiety. Physiological Behavior. 1992;52:305–311. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(92)90276-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker RC, Wright JA, Pepe MS, Seidel KD, Dietz WH. Predicting obesity in young adulthood from childhood and parental obesity. New England Journal of Medicine. 1997;337:869–873. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709253371301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson GT. Behavioral treatment of childhood obesity. Theoretical and practical implications. Health Psychology. 1994;13:371–372. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.13.5.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisniewski L, Epstein LH, Caggiula AR. Effect of food change on consumption, hedonics, and salivation. Physiology and Behavior. 1992;52:21–26. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(92)90428-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisniewski L, Epstein LH, Marcus MD, Kaye W. Differences in salivary habituation to palatable foods in bulimia nervosa patients and controls. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1997;59:427–433. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199707000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wooley SC, Wooley OW. Salivation to the sight and smell of food. A new measure of appetite. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1973;35:136–142. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197303000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wooley OW, Wooley SC. Deprivation, expectation and threat. Effects on salivation in the obese and non obese. Physiology and Behavior. 1976;17:187–193. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(76)90062-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]