Abstract

Glucocorticoid receptor (GR) antagonism may be of considerable therapeutic value in stress-related psychopathology such as depression. However, blockade of all GR-dependent processes in the brain will lead to unnecessary and even counteractive effects, such as elevated endogenous cortisol levels. Selective GR modulators are ligands that can act both as agonist and as antagonist and may be used to separate beneficial from harmful treatment effects. We have discovered that the high-affinity GR ligand C108297 is a selective modulator in the rat brain. We first demonstrate that C108297 induces a unique interaction profile between GR and its downstream effector molecules, the nuclear receptor coregulators, compared with the full agonist dexamethasone and the antagonist RU486 (mifepristone). C108297 displays partial agonistic activity for the suppression of hypothalamic corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) gene expression and potently enhances GR-dependent memory consolidation of training on an inhibitory avoidance task. In contrast, it lacks agonistic effects on the expression of CRH in the central amygdala and antagonizes GR-mediated reduction in hippocampal neurogenesis after chronic corticosterone exposure. Importantly, the compound does not lead to disinhibition of the hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal axis. Thus, C108297 represents a class of ligands that has the potential to more selectively abrogate pathogenic GR-dependent processes in the brain, while retaining beneficial aspects of GR signaling.

Keywords: HPA axis, neuroendocrinology, steroid pharmacology, transcription regulation, NCoA1

Adrenal glucocorticoid hormones are essential for adaptation to stressors, but prolonged or excessive exposure to glucocorticoids has been consistently implicated in the development of stress-related psychopathologies, such as depression (1). Antagonism of their most abundant receptor type, the glucocorticoid receptor (GR), can be beneficial in stress-related psychiatric disease [e.g., to abrogate psychotic and depressive features in patients with Cushing’s syndrome (2) and in patients suffering from psychotic major depression (3)]. The GR is widely distributed in the brain (4), where it affects many different processes including learning and memory (5, 6), adult neurogenesis (7), and neuroendocrine negative feedback regulation (8). Although GR antagonism of particular processes may be of therapeutic benefit, blocking other GR-mediated effects may actually counteract the potential therapeutic efficacy. For example, GR antagonists interfere with glucocorticoid negative feedback and lead to increased cortisol levels (9, 10), which inadvertently activate mineralocorticoid receptors (MRs) to which corticosteroids bind in the brain and diminish the efficacy of antagonism at relevant sites.

The GR is a nuclear receptor (NR) that affects gene transcription through a number of transcriptional mechanisms. For several NRs, “selective receptor modulators” exist. These can act as an agonist, as well as an antagonist depending on the tissue or gene targets, with the estrogen-receptor ligand tamoxifen as a well-known example (11). Selective GR modulators (SGRMs) may be used to separate beneficial from unwanted glucocorticoid effects. Anti-inflammatory SGRMs with diminished side effects have been pursued, based on the distinction between GR effects that depend on direct DNA binding and those that take place via protein–protein interactions between the GR and other transcription factors (12). Selective receptor modulation may also be based on specificity of ligand-induced interactions between the GR and its major downstream effector molecules, the NR coregulators (13).

Many receptor–coregulator interactions depend on the GR’s ligand-binding domain (GR-LBD) and on specific coregulator amino acid motifs that contain an LXXLL sequence, known as “nuclear receptor-boxes” (NR-boxes). These interactions are governed by the conformation that is induced by a particular ligand and may be screened for in vitro (14). The importance of individual coregulators for brain GR function is largely unknown, but an exception is steroid coactivator (SRC)-1 [or nuclear receptor coactivator 1 (NCoA1)]. SRC-1 is necessary for GR-mediated negative gene regulation in the hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis (15, 16) and for the induction of corticotropin releasing hormone (CRH) gene expression in the central nucleus of the amygdala (CeA) (16). Its two splice variants SRC-1A and -1E seem to exert opposite effects on CRH expression (17). Selective activation of GR interactions with SRC-1A, brought about via an SRC-1A–specific NR-box, would be expected to separate GR-mediated effects on CRH expression in the hypothalamus and amygdala.

Here, we show proof of principle for selective GR modulation in the brain with relevance for stress regulation, cognition, and psychopathology. We show that a previously described selective high-affinity GR ligand induces a unique coregulator interaction profile that distinguishes between the two splice variants of SRC-1. C108297 [or compound 47 from ref. 18] has a Ki of 0.9 nM for GR and >10 µM for progesterone receptor (PR), MR, and androgen receptor (18). It shows GR antagonism in relation to GR-dependent CRH mRNA regulation in the amygdala and corticosterone-induced reduction in hippocampal neurogenesis. The agonistic effects of C108297 include enhanced memory consolidation of emotionally arousing training and a suppression of hypothalamic CRH expression. The compound does not lead to net inhibition of glucocorticoid negative feedback, as indicated by unaltered circulating corticosterone levels.

Results

C108297 Displays Selective Modulator Activity in Vitro.

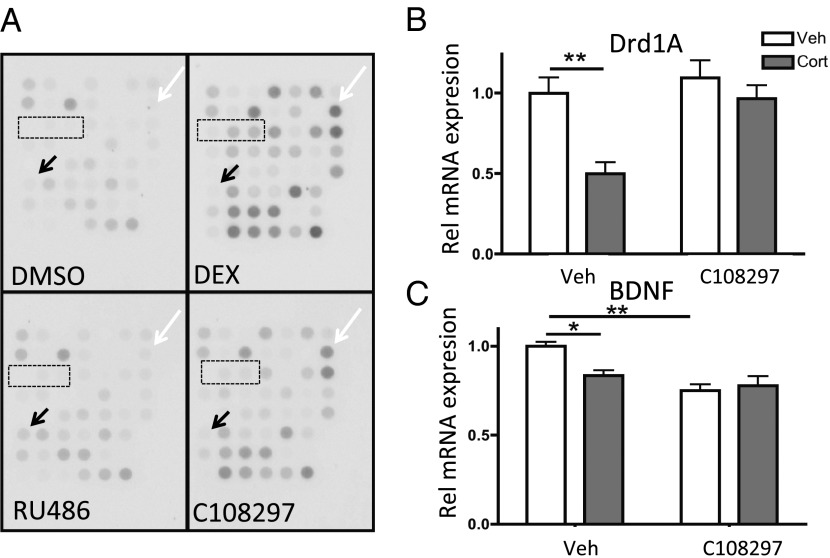

To explore possible selective modulator activity of C108297 based on the GR–coregulator interactions, we used a MARCoNI peptide array (14) to determine interactions between (recombinant) GR-LBD and coregulator NR boxes (Fig. 1A). Reference drugs were the full agonist dexamethasone (DEX) and the prototypical antagonist RU486 at saturating doses. Without ligand, GR displayed only weak interactions with coregulator motifs. DEX induced significant interactions between GR-LBD and 28 motifs from coactivator proteins. RU486 induced modest interactions with motifs from two corepressor proteins, nuclear receptor corepressors (NCORs) 1 and 2 (19). C108297 induced interactions with a subset of the motifs that were recruited after DEX treatment, suggesting selective modulator activity. C108297 did not induce interactions with NCoR motifs. For quantitative analysis, see Fig. 2. The partial recruitment of coregulator motifs of C108297-bound GR suggests that the compound combines agonistic and antagonistic effects (dependent on the gene-specific coregulator use by GR).

Fig. 1.

C108297 behaves like a selective modulator in vitro and in vivo. (A) Ligand-induced interactions between the GR-LBD and coregulator motifs. DEX induced many interactions compared with DMSO. RU486 induced modest interactions with corepressor motifs (black arrow: NCoR1). C108297 showed an intermediate profile. GR-LBD interactions with the central motifs from SRC-1 were much weaker or absent (boxed), but others were retained (white arrow indicates SRC-1 motif IV). (B) Hippocampal Drd1a mRNA was regulated by corticosterone after vehicle but not C108298 treatment. (C) BDNF mRNA was down-regulated by both corticosterone and C108297. Asterisks indicate significant differences from the control group (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01).

Fig. 2.

SCR-1 splice variant 1E is selectively recruited by GR-C108297. (A) Protein structure of SRC-1 harboring three NR central boxes (roman numerals). SRC-1A harbors a repressor function (RF) and the additional NR-box IV. Protein fragments marked by dotted lines refer to C. (B) MARCoNI quantification showed that unlike DEX, C108297 induced interactions only between GR and NR-box IV. (C) In a two-hybrid assay only DEX induced interaction with the SRC-1 fragment common to both splice variants. The SRC-1A–specific protein fragment was also recruited by GR-C108297. A fragment of corepressor NCoR1 only interacted after incubation with RU486. Asterisks indicate significant difference from the control condition (P < 0.001).

C108297 Reaches the Brain.

We tested whether C108297 can reach the brain to affect GR-dependent processes. Three hours after oral treatment of rats, C108297 (20 mg/kg) led to 35 ± 15% occupancy of brain GR binding determined ex vivo in one hemisphere, compared with the negative control. This level of occupancy did not differ from that observed for the positive control of 3 mg/kg corticosterone [well above the ED50 of 0.6 mg/kg (20)], which resulted in 44 ± 15% GR occupancy. This degree of occupancy is considered effective for many corticosterone effects via GR (e.g., ref. 21), and the dose of 20 mg/kg C108297 was used in all other in vivo experiments described below, with the exception of the work on neurogenesis that was initiated earlier.

C108297 Displays Gene-Specific Agonism and Antagonism on GR Target Genes in Vivo.

To confirm gene-specific antagonism of C108297, we tested mRNA regulation of two previously characterized hippocampal GR target genes (22). Rats were treated with 3 mg/kg corticosterone with of without pretreatment with C1082987 (20 mg/kg) or with C108297 alone. For Drd1a mRNA (coding for the dopamine 1A receptor), two-way ANOVA showed main effects of corticosterone (P < 0.01) and C108297 (P < 0.05) but no interaction (but endogenous corticosterone was present). Drd1a mRNA was significantly lower after corticosterone (3 mg/kg) treatment but not after (pre)treatment with C108297 (20 mg/kg) (Fig. 1B). For BDNF regulation, two-way ANOVA showed main effects of corticosterone, C108297 (both P < 0.05) and an interaction (P < 0.001). C108297 by itself down-regulated BDNF mRNA levels and did not prevent the corticosterone effect (Fig. 1C).

C108297 Distinguishes Between SRC-1 Splice Variants.

Out of many potential coregulators of GR, SRC-1 is among the few that have been linked to regulation of specific GR target genes (15, 16). Its splice variants SRC-1A and -1E may mediate different effects in relation to stress adaptation (17). Because C108297 seemed to differentiate between the SRC-1 splice variants, we focused on these for further analysis. Quantitative analysis of the MARCoNI data showed that C108297 differentiates between the three NR-boxes that are common to the two SRC-1 splice variants and NR-box IV, which that is unique to SRC-1A (23) (Fig. 2A). Two-way ANOVA indicated highly significant differences between ligands and motifs and a strong interaction between the two (P < 0.001 for main effects and the interaction). DEX was able to induce strong GR interactions with all four SRC-1 motifs, but C108297 induced substantial agonist-like binding only for the SRC-1A specific NR-box (Fig. 2B), confirming potentially selective recruitment of this splice variant by the GR-C108297 complex.

We validated the ligand-directed differential recruitment of SRC-1 splice variants using larger protein fragments in a two-hybrid system in mammalian COS-1 cells (Fig. 2C). Two-way ANOVA showed significant effects of drug and protein fragment and an interaction (P < 0.001 for all effects). Both DEX and C108297 induced a strong GR-LBD interaction with a 420-aa fragment containing the SRC-1A specific NR-box IV. DEX, but not C108297, induced interactions with the SRC-1 domain containing the three central NR-boxes. A fragment from the corepressor NCoR1 was recruited by GR-LBD only after incubation with the antagonist RU486. Thus, the ligand selective interactions of GR also occurred with large protein fragments in cell line context.

C108297 Has Selective Partial Agonist Activity in the Brain of Adrenalectomized Rats.

The selective modulator type interactions of GR with SRC-1 variants led to the hypothesis that C108297 in vivo acts as an agonist for GR-mediated regulation of the Crh gene in the core of the HPA axis but not in the CeA (17, 24). To test agonism, we used adrenalectomized rats in a 5-d treatment paradigm in which half of the animals underwent a single restraint stress on day 5, 30 min before they were euthanized. This paradigm allows measurement of a number of both basal and stress-induced HPA axis variables (25). It is well established that CRH expression in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus (PVN) and CeA both respond to treatment with our control agonist DEX, but in an opposite direction (26).

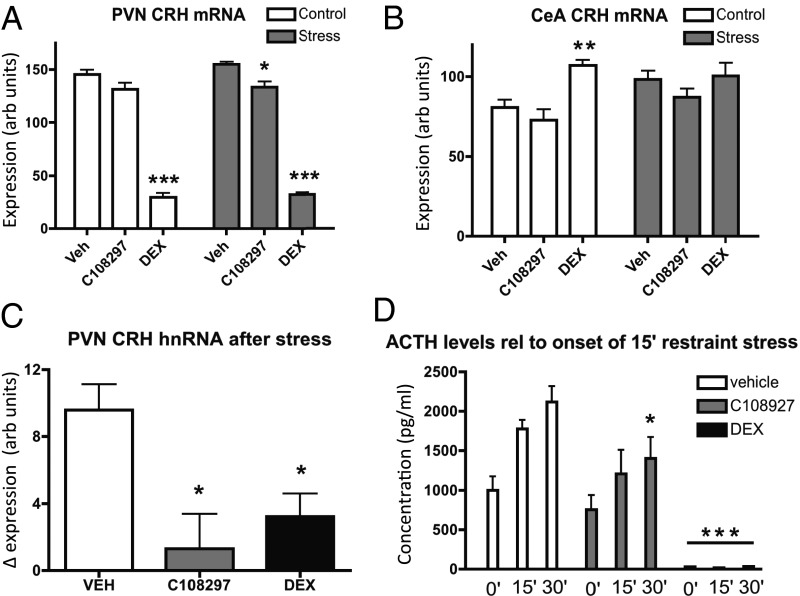

CRH mRNA in both brain regions responded to drug but not to acute stress (two-way ANOVA: drug effect of PVN, P < 0.001; CeA, P = 0.011; stress effect not significant). In the PVN (Fig. 3A), CRH mRNA was strongly suppressed by DEX. C108297 also showed modest agonism that reached significance in the stressed animals. CRH mRNA in the CeA (Fig. 3B) was increased after DEX treatment in nonstressed animals but unaffected by C108297. In the stressed rats, the differences between the treatment groups failed to reach significance. A more substantial agonist effect of C108297 was observed for stress-induced CRH heteronuclear (hn) RNA in the PVN. This response was equally strongly suppressed by DEX and C108297 (Fig. 3C; one-way ANOVA: P < 0.001). In the CeA, the levels of CRH hnRNA were below detection, even after prolonged exposure of the films. Thus, C108297 showed (partial) agonism in the PVN but not in CeA.

Fig. 3.

Selective GR modulation in the stress system: C108297-agonism in ADX rats after subchronic treatment compared with the prototypic agonist DEX. (A) In the PVN, where SRC-1A is expressed at high levels, DEX led to strong down-regulation of CRH mRNA (P < 0.001). C108297 had a modest agonist effect that reached significance in the stressed group (P < 0.05). (B) In the CeA, DEX up-regulated CRH mRNA in nonstressed rats (P < 0.05), but C108297 was without effect. (C) The acute response of the Crh gene in response to restraint stress was strongly attenuated both by pretreatment with DEX and C108297. (D) DEX led to a complete blockade of the HPA axis (P < 0.001), whereas C108297 leads to a very weak attenuation of the adrenocortical stress response (P < 0.05).

To assess other (ant)agonist-like effects of C108297 on HPA axis activity, we determined basal and acute restraint stress-induced adrenocorticotropin (ACTH) secretion after 5 d of treatment [Fig. 3D; two-way ANOVA effects of time after onset of stress: drug-pretreatment (P < 0.001) and an interaction (P < 0.01)]. DEX led to a complete suppression of basal and stress-induced ACTH release. Subchronic C108297 treatment did not affect basal ACTH levels in these adrenalectomized (ADX) animals but led to a modest suppression of stress-induced ACTH release, possibly indicating a weak agonistic effect.

C108297 Has Selective Antagonist Activity in Adrenally Intact Rats.

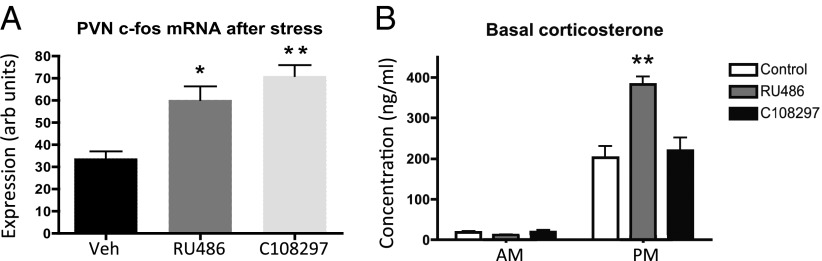

To determine neuroendocrine antagonistic effects against endogenous corticosterone we compared 5-d treatment of C108297 (20 mg/kg) with RU486 (40 mg/kg) in adrenally intact rats, followed by restraint stress on day 5 in half of the animals. The stressor strongly induced expression of both CRH hnRNA in the PVN (two-way ANOVA: P < 0.001) and led to a modest increase in CRH mRNA (two-way ANOVA: P < 0.05), but these parameters were not affected by drug treatment (not shown), consistent with a lack of GR involvement in the immediate curtailing of the transcriptional CRH response in acute stress situations (27). There was no effect of subchronic drug treatment or the stressor on amygdala CRH mRNA. The only central measure that responded to subchronic drug treatment in intact rats was the c-fos response to restraint stress in the PVN (one-way ANOVA: P < 0.001). Both RU486 and C108927 treatment led to elevated c-fos mRNA expression 30 min after the onset of stress (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

Selective GR modulation in the stress system: antagonism in adrenally intact rats after subchronic treatment compared with the prototypic antagonist RU486. (A) The acute c-fos response to stress in the PVN was enhanced both by pretreatment with RU486 and C108297. (B) RU486 treatment led to increased circadian peak levels of plasma corticosterone. C108297 does not have this effect. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

With regard to stress-induced activation of the HPA axis, the two compounds also led to similar changes, indicative of antagonism by C108297. At 15 min after the onset of the restraint stress, corticosterone levels were about 25% lower in both the RU486 (301 ± 69 ng/mL) (28) and C108297 (273 ± 52 ng/mL) treatment groups compared with controls (409 ± 36 ng/mL). In contrast, RU486 increased the amplitude of the basal diurnal corticosterone rhythm by increasing evening corticosterone levels without affecting morning levels, as described (9), but C108297 did not have this antagonistic effect (Fig. 4B; P < 0.001 for drug, time, and interaction effects).

We also tested the acute effect of RU486 and C108297 on stress-induced corticosterone in “naïve” rats. Treatment with C108297 and RU486 30 min before a stressor led to suppression of the amplitude of the corticosterone response at 30 min after stress (Fig. S1).

Agonism and Antagonism on Neurogenesis and Behavior.

To further evaluate the efficacy of C108297 in animal models with relevance for psychopathology, we evaluated the effect of C108297 in two paradigms: corticosterone-induced suppression of neurogenesis and memory consolidation of inhibitory avoidance training.

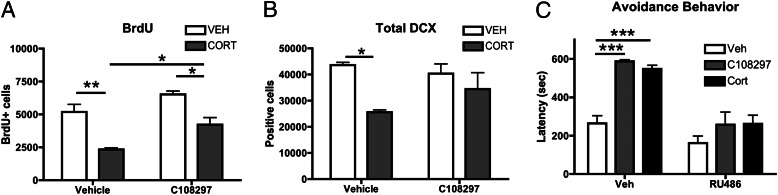

C108297 was tested for reversal of GR-dependent reduction in adult neurogenesis after 3 wk of treatment with a high dose of corticosterone (40 mg⋅kg−1⋅d−1). RU486 was shown previously to fully normalize the reduction in neurogenesis induced by corticosterone or chronic stress (29). In a comparable design, C108297 (50 mg/kg) was administered during the last 4 d of corticosterone treatment. Two-way ANOVA indicated that the number of cells that stained for BrdU (a marker for newborn cell survival) was affected by chronic corticosterone treatment (P = 0.008) and by C108297 treatment (P < 0.001), but there was no significant interaction. Post hoc analysis revealed that the difference between C108297 and vehicle groups only reached significance in animals treated chronically with corticosterone (Fig. 5A). The number of double-cortin (DCX)-positive cells in the dentate gyrus, indicative of neuronal differentiation of newborn cells, was affected by chronic corticosterone treatment (P = 0.002) but not by C108297 (P > 0.4), although there was a trend toward an interaction (P = 0.089). Post hoc analysis indicated a significantly lower number of DCX positive cells after chronic corticosterone treatment only in the group treated with the vehicle for C108297 (Fig. 5B). Thus, C108297 partially counteracted the effects of chronic corticosterone treatment.

Fig. 5.

C108297 acts as GR antagonist in neurogenesis and as agonist in memory retention. (A) Chronic corticosterone suppressed the number of BrdU-positive cell, and 4 d of C108297 treatment increased this number. BrdU scores were significantly higher in animals that received C108297 in combination with chronic corticosterone, compared with corticosterone-treated animals that did not receive C108297. (B) Total DCX-positive cells were significantly fewer after 3 wk of corticosterone treatment but not in animals that also received C108297. (C) Acute posttraining C108297 (20 mg/kg) or corticosterone (1 mg/kg) led to long 48-h retention test latencies in the inhibitory avoidance task, and these effects were blocked by pretreatment with RU486. Significant differences: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

To determine whether C108297 affected memory consolidation, rats were trained on an aversively motivated single-trial inhibitory avoidance task, which is known to be potentiated by GR activation (30). A corticosterone (1 mg/kg) treatment was included as a positive control. Retention test latencies, as assessed 48 h after training, indicated a significant drug treatment effect (Kruskal–Wallis test: P < 0.001; Fig. 5C). Rats treated with either corticosterone or C108297 had significantly longer retention latencies than vehicle-treated rats (P < 0.001). This effect could be blocked by RU486 pretreatment. These findings indicate that C108297 has substantial GR agonism in this paradigm.

Discussion

High levels of circulating glucocorticoids as a consequence of acute or chronic stress are known risk factors in the development of psychopathologies, either as predisposing factors or during precipitation of disease. GR antagonists have therapeutic potential (28, 31) but given the ubiquitous expression of the GR, they have many undesired side effects (32). Disinhibition of the HPA axis is a side effect that actually counteracts the goal of any such treatment (i.e., blockade of GR signaling). SGRM compounds that combine antagonistic and agonistic GR properties may lead to a better-targeted interference with stress-related brain processes.

Based on the C108297-induced interactions between GR and its coregulators, we hypothesized and confirmed that this compound is a selective GR modulator, with relevance for the brain. Interestingly, clear antagonist effects on the brain were accompanied by lack of negative-feedback inhibition of the HPA axis, which in itself suggests the possibility of antagonizing a number of GR effects without affecting systemic basal glucocorticoid levels and the associated change in activity of, for example, MR-dependent processes (33). C108297 is expected to have selective modulator effects also in peripheral tissues that we did not examine here (34). We did not determine binding to MRs and PRs or specific MR/PR readouts here, but previous studies showed 0% displacement from MR and 26% from PR at 10 µM C108297, i.e., over a 1000-fold selectivity for GR (18). In peripheral tissues, we cannot exclude some binding to PR with the 20 mg/kg dose C108297, but under nonsaturating conditions for brain GR, activation of other steroid receptors is unlikely. Selective targeting to the brain may constitute a particularly efficacious way to interfere with a number of central GR-dependent processes, with very few side effects.

In the MARCoNI assay the overall strength of the GR bound to C108297 interactions with coregulator motifs is somewhat lower than for GR bound to DEX, suggesting that C108297 is a partial agonist. Some of the antagonist effects that we observed after a single dose in vivo may indeed reflect partial agonism relative to circulating corticosterone. However, because some of the coregulator interactions become zero, whereas others still reach substantial levels, the molecular profile is that of a selective modulator. It is unclear at this point whether the GR follows a two-state agonist conformation, with C108297 leading to a similar, but less stable, conformation to DEX (35), or whether C108297 leads to a unique conformation of the GR-LBD. C108297 clearly differs from the well-known (but nonselective) antagonist RU486, because it lacks the capacity to induce interactions with domains from corepressors NCoR1 and -2, and the associated intrinsic (repressive) activity that may come from those interactions (19).

Reversal of glucocorticoid-induced effects was observed for expression of the Drd1a gene in the hippocampus. This effect may be of relevance for reversal of negative effects of glucocorticoids on cognition (36). Given chronically, C108297 also antagonized the effects of corticosterone on adult neurogenesis. Here, C108297 seemed to be less potent than RU486 (32), perhaps because of a lack of interactions between GR and the classical corepressors. Notwithstanding, reversal of decreased neurogenesis may be relevant for antidepressive effects (37). In relation to regulation of brain CRH, the compound seems to have beneficial effects in the context of stress-related psychopathology, as was predicted by its interactions with the coregulator SRC-1 splice variants (16, 17). The compound lacked efficacy for the potentially anxiogenic induction of CRH via GR (38) even in ADX rats. It showed a mild degree of agonism on basal CRH expression in the PVN, and pretreatment had a substantial suppressive (agonistic) effect on stress-induced CRH transcription (39). Moreover, there was a clear lack of antagonism by C108297 on basal regulation of the HPA axis, which is an important advantage over complete antagonists such as RU486 when trying to interfere with central consequences of hypercorticism (9).

C108297 does not cause an overall dampening of brain stress responses. Like RU486, it enhanced stress-induced neuronal activity in the PVN, indicating either changed responsiveness of the parvocellular neurons or changed activity of neuronal afferents to the PVN. The apparent agonism on BDNF expression (21) also shows that some consequences of stress may be mimicked by the compound. The GR-dependent increased consolidation of inhibitory avoidance memory also is in line with well-known stress effects and can be either adaptive or maladaptive (6, 40).

Our data emphasize the multiple levels of GR-mediated control over the HPA axis. For example, RU486, as well as C108297, led to an increased c-fos response to stress in the PVN but to an attenuated stress-induced ACTH release. This dissociation has been observed by others after direct and acute manipulation of the PVN (41). The extent to which CRH and c-fos respond to stressors in naïve rats is in general highly dependent on multiple factors, including the type of stressor and time after stress (42, 43).

A small part of the selective GR modulation in vivo may be explained by differential recruitment of SRC-1A and -1E, and the role of numerous GR–coregulator interactions in mediating the many effects of GR activation on brain will be subjected to further research. SGRMs such as C108297 and their molecular interaction profiles, combined with knowledge of the regional distribution of coregulators in the brain, can, in the future, assist in dissecting the molecular signaling pathways underlying stress-related disorders. In fact, although our analysis was necessarily not comprehensive [e.g., in relation to nongenomic GR signaling (44)], C108297 itself may have a beneficial profile compared with a situation of hypercortisolism.

Materials and Methods

For full details, see SI Material and Methods.

Peptide Interaction Profiling.

Interactions between the GR-LBD and coregulator NR-boxes were determined using a MARCoNI assay with 55 immobilized peptides, each representing a coregulator-derived NR-box (PamChip no. 88011; Pamgene International) (14). Each array was incubated with a reaction mixture of 1 nM GST-tagged GR-LBD, ALEXA488-conjugated GST-antibody, and buffer F (PV4689, A-11131, and PV4547; Invitrogen) and 1 µM DEX, RU486, C108297, or solvent (2% DMSO in water). Incubation was performed at 20 °C in a PamStation96 (Pamgene International). GR binding to each peptide on the array, reflected by fluorescent signal, was quantified by analysis of .tiff images using BioNavigator software (Pamgene International).

Two-Hybrid Studies.

To generate fusions to the DNA-binding protein Gal4, partial coregulator cDNAs were cloned into the pCMV-BD vector (Stratagene): SRC-1 residues 621–1020, SRC-1A residues 1021–1441, and NCoR1 residues 1962–2440 (45). COS-1 cells were transfected using Lipofectamine2000 (Invitrogen) with a combination of a Gal4–coregulator fusion plasmid, the pGR-VP16 transactivator plasmid, and the pFR-Luc reporter gene (Stratagene). Twenty-four hours after transfection, the medium was replaced with medium containing 0.1% DMSO, DEX, RU486, or C108297 (all 1 µM). The next day, the medium was replaced with 0.1 mL Hank’s balanced salt solution plus 0.1 mL of Steadylight (Perkin-Elmer), and luminescence was counted on a Topcount instrument (Perkin Elmer).

Animal Experiments.

Animal experiments were carried out in accordance with the European Community Council Directive of November 24, 1986 (86/609/EEC), certificates and licenses were granted under the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986 by the United Kingdom Home Office, or experiments were approved by the Local Committees for Animal Health, Ethics, and Research of the Dutch universities involved. Male rats were used, housed in temperature-controlled facilities on a 12-h day–night schedule with food and water available ad libitum. Modes of administration and duration of drug treatment differed in accordance with the standards used in the different in vivo paradigms.

Binding to Brain GR.

Group-housed Sprague–Dawley rats were orally dosed with corticosterone (3 mg/kg) or C108297 (20 mg/kg and 100 mg/kg) dissolved in 10% DMSO/90% methylcellulose (0.5% wt/vol). After 3 h, the rats were killed and half-brains were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Tissue was homogenized in buffer using a Bead Ruptor at 4 °C for 15 min. Free GR ligands were cleared by incubation of homogenates with dextran-coated charcoal (Sigma; C-6197). Receptor binding was determined by incubating homogenate with 2.5 nM [3H]DEX (Amersham; TRK645) at 4 °C for 18 h. Nonspecific binding was determined by addition of 20 µM unlabeled DEX. Unbound ligand was removed using dextran-coated charcoal. [3H]DEX activity was quantified as counts per minute on a Perkin-Elmer Topcount, using a Packard Optiplate and MicroScint40.

Hippocampal Gene Expression.

From the other halves of the brains 200 µm thick coronal sections were mounted on glass slides (Gerhard Menzel). Hippocampal CA1 tissue punches were taken with a Harris Uni-Core hollow needle (Electron Microscopy Sciences; 1.2 mm internal diameter), starting around 2.56 mm posterior to Bregma (46). RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis, and quantitative PCR have been described elsewhere (47). Validated hippocampal GR target genes were selected from microarray analysis (Rat Genome 230 2.0 Arrays; Affymetrix) (22). Tubulin β2a was used to normalize expression (48).

Subchronic Treatment: Agonism in Relation to CRH and the HPA Axis.

Group-housed Wistar rats (200–220 g; Harlan) underwent ADX in the morning as described (49). One week later, animals were treated twice daily (s.c., 1 mL/kg) with vehicle (polyethylene glycol-300), C108297 (20 mg/kg), or DEX (0.5 mg/kg) (25). On day 5, 3 h after the morning injection, half of the animals underwent 30 min of restraint stress. A tail-cut sample was collected 15 min after the onset of restraint. Animals were killed by decapitation either under basal conditions or at 30 min after onset of the restraint. CRH and c-fos mRNA and CRH hnRNA were quantified by in situ hybridization on whole PVN and CeA as described previously (25). Corticosterone and ACTH were measured by radioimmunoassay (MP Biomedicals).

Subchronic Treatment: Antagonism in Relation to CRH and the HPA Axis.

Procedures were as described above but in intact rats, this time using RU486 (40 mg/kg) as a reference drug. Tail cuts that were performed at 0800 hours and 2000 hours on day 4 for basal plasma corticosterone levels. To determine acute stress responses in naïve rats, we subjected rats to an acute 0.4-mA foot shock in an inhibitory avoidance shock box (50), with or without a single pretreatment with the doses of RU486 and C108297 that were used in the subchronic setting.

Neurogenesis.

Group-housed Wistar rats (200 g) were habituated to the animal facility for 10 d. Corticosterone (Sigma; C-2505; 40 mg/kg) or vehicle (arachis oil) was injected (s.c.) daily at 0900 hours on 21 d. Animals received C108297 (50 mg/kg) or vehicle [0.1% ethanol in coffee cream; Campina] by gavage on the final 4 d of corticosterone treatment at 0900 h and 1600 h. Animals were killed 1 d after the last treatment. All animals received 5-bromo-2-deoxyuridine (BrdU) (200 mg/kg, i.p) on day 1, 3 h after the first corticosterone injection. Tissue processing for immunostainings was performed as described (29). Data on vehicle-treated groups were also reported elsewhere (29).

Inhibitory Avoidance Behavior.

One-trial inhibitory avoidance training and retention was performed as described (30), using single-housed Wistar rats (300–350 g; Charles River) and a foot-shock intensity of 0.5 mA for 1 s. RU486 (40 mg/kg) or vehicle (polyethylene glycol) was administered (s.c.) 1 h before the training session. C108297 (20 mg/kg) or corticosterone (1 mg/kg) was dissolved in DMSO and administered (100 µL, s.c.) immediately after the training trial, so that treatment did not interfere with memory acquisition. Retention was tested 48 h later. A longer latency to enter the former shock compartment with all four paws (maximum latency of 600 s) was interpreted as better memory.

Statistical Analysis.

Data were analyzed using Graphpad Prism using (as appropriate) one- or two-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s/Bonferroni post hoc test, respectively, and Kruskal–Wallis for data that deviated from a normal distribution.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dirk Pijnenburg, Peter Steenbergen, Angela Sarabdjitsingh, Menno Hoekstra, Ronald van der Sluis, and Lisa van Weert for technical assistance. This work was supported by Center of Medical Systems Biology Grant 2 3.3.6 (to E.R.d.K. and O.C.M.), Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research MEERVOUD Grant 836.06.010 (to N.A.D.), and the Royal Dutch Academy of Arts and Sciences (E.R.d.K.).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: J.K.B. and H.H. are employees of Corcept Therapeutics, which develops glucocorticoid receptor ligands for clinical use. Corcept Therapeutics has provided compounds and financed part of the experiments. R.H. is an employee of Pamgene International, which provided the peptide arrays used in this study.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1219411110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.de Kloet ER, Joëls M, Holsboer F. Stress and the brain: From adaptation to disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6(6):463–475. doi: 10.1038/nrn1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nieman LK, et al. Successful treatment of Cushing’s syndrome with the glucocorticoid antagonist RU 486. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1985;61(3):536–540. doi: 10.1210/jcem-61-3-536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DeBattista C, et al. Mifepristone versus placebo in the treatment of psychosis in patients with psychotic major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60(12):1343–1349. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosenfeld P, Van Eekelen JA, Levine S, De Kloet ER. Ontogeny of the type 2 glucocorticoid receptor in discrete rat brain regions: An immunocytochemical study. Brain Res. 1988;470(1):119–127. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(88)90207-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roozendaal B, McGaugh JL. Memory modulation. Behav Neurosci. 2011;125(6):797–824. doi: 10.1037/a0026187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joëls M, Pu Z, Wiegert O, Oitzl MS, Krugers HJ. Learning under stress: How does it work? Trends Cogn Sci. 2006;10(4):152–158. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fitzsimons CP, et al. Knockdown of the glucocorticoid receptor alters functional integration of newborn neurons in the adult hippocampus and impairs fear-motivated behavior. Mol Psychiatry. 2012 doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Watts AG. Glucocorticoid regulation of peptide genes in neuroendocrine CRH neurons: A complexity beyond negative feedback. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2005;26(3-4):109–130. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spiga F, et al. Effect of the glucocorticoid receptor antagonist Org 34850 on basal and stress-induced corticosterone secretion. J Neuroendocrinol. 2007;19(11):891–900. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2007.01605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ratka A, Sutanto W, Bloemers M, de Kloet ER. On the role of brain mineralocorticoid (type I) and glucocorticoid (type II) receptors in neuroendocrine regulation. Neuroendocrinology. 1989;50(2):117–123. doi: 10.1159/000125210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson AB, O’Malley BW. Steroid receptor coactivators 1, 2, and 3: Critical regulators of nuclear receptor activity and steroid receptor modulator (SRM)-based cancer therapy. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2012;348(2):430–439. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2011.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Bosscher K, Vanden Berghe W, Haegeman G. The interplay between the glucocorticoid receptor and nuclear factor-kappaB or activator protein-1: Molecular mechanisms for gene repression. Endocr Rev. 2003;24(4):488–522. doi: 10.1210/er.2002-0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coghlan MJ, et al. A novel antiinflammatory maintains glucocorticoid efficacy with reduced side effects. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17(5):860–869. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koppen A, et al. Nuclear receptor-coregulator interaction profiling identifies TRIP3 as a novel peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma cofactor. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2009;8(10):2212–2226. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M900209-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Winnay JN, Xu J, O’Malley BW, Hammer GD. Steroid receptor coactivator-1-deficient mice exhibit altered hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function. Endocrinology. 2006;147(3):1322–1332. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lachize S, et al. Steroid receptor coactivator-1 is necessary for regulation of corticotropin-releasing hormone by chronic stress and glucocorticoids. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(19):8038–8042. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812062106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van der Laan S, Lachize SB, Vreugdenhil E, de Kloet ER, Meijer OC. Nuclear receptor coregulators differentially modulate induction and glucocorticoid receptor-mediated repression of the corticotropin-releasing hormone gene. Endocrinology. 2008;149(2):725–732. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clark RD, et al. 1H-Pyrazolo[3,4-g]hexahydro-isoquinolines as selective glucocorticoid receptor antagonists with high functional activity. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008;18(4):1312–1317. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schulz M, et al. RU486-induced glucocorticoid receptor agonism is controlled by the receptor N terminus and by corepressor binding. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(29):26238–26243. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203268200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reul JM, de Kloet ER. Two receptor systems for corticosterone in rat brain: Microdistribution and differential occupation. Endocrinology. 1985;117(6):2505–2511. doi: 10.1210/endo-117-6-2505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schaaf MJM, de Jong J, de Kloet ER, Vreugdenhil E. Downregulation of BDNF mRNA and protein in the rat hippocampus by corticosterone. Brain Res. 1998;813(1):112–120. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)01010-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Datson NA, et al. Specific regulatory motifs predict glucocorticoid responsiveness of hippocampal gene expression. Endocrinology. 2011;152(10):3749–3757. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-0287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kalkhoven E, Valentine JE, Heery DM, Parker MG. Isoforms of steroid receptor co-activator 1 differ in their ability to potentiate transcription by the oestrogen receptor. EMBO J. 1998;17(1):232–243. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.1.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meijer OC, Steenbergen PJ, De Kloet ER. Differential expression and regional distribution of steroid receptor coactivators SRC-1 and SRC-2 in brain and pituitary. Endocrinology. 2000;141(6):2192–2199. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.6.7489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karssen AM, Meijer OC, Berry A, Sanjuan Piñol R, de Kloet ER. Low doses of dexamethasone can produce a hypocorticosteroid state in the brain. Endocrinology. 2005;146(12):5587–5595. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Makino S, et al. Regulation of corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor messenger ribonucleic acid in the rat brain and pituitary by glucocorticoids and stress. Endocrinology. 1995;136(10):4517–4525. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.10.7664672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aguilera G, Kiss A, Liu Y, Kamitakahara A. Negative regulation of corticotropin releasing factor expression and limitation of stress response. Stress. 2007;10(2):153–161. doi: 10.1080/10253890701391192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wulsin AC, Herman JP, Solomon MB. Mifepristone decreases depression-like behavior and modulates neuroendocrine and central hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis responsiveness to stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2010;35(7):1100–1112. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2010.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hu P, et al. A single-day treatment with mifepristone is sufficient to normalize chronic glucocorticoid induced suppression of hippocampal cell proliferation. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(9):e46224. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fornari RV, et al. Involvement of the insular cortex in regulating glucocorticoid effects on memory consolidation of inhibitory avoidance training. Front Behav Neurosci. 2012;6:10. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2012.00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bachmann CG, Linthorst ACE, Holsboer F, Reul JMHM. Effect of chronic administration of selective glucocorticoid receptor antagonists on the rat hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28(6):1056–1067. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sapolsky RM, Romero LM, Munck AU. How do glucocorticoids influence stress responses? Integrating permissive, suppressive, stimulatory, and preparative actions. Endocr Rev. 2000;21(1):55–89. doi: 10.1210/edrv.21.1.0389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Joëls M, Karst H, DeRijk RH, de Kloet ER. The coming out of the brain mineralocorticoid receptor. Trends Neurosci. 2008;31(1):1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Asagami T, et al. Selective glucocorticoid receptor (GR-II) antagonist reduces body weight gain in mice. J Nutr Metab. 2011;2011:235389. doi: 10.1155/2011/235389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raaijmakers HCA, Versteegh JE, Uitdehaag JCM. The X-ray structure of RU486 bound to the progesterone receptor in a destabilized agonistic conformation. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(29):19572–19579. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.007872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ortiz O, et al. Associative learning and CA3-CA1 synaptic plasticity are impaired in D1R null, Drd1a-/- mice and in hippocampal siRNA silenced Drd1a mice. J Neurosci. 2010;30(37):12288–12300. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2655-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sahay A, Hen R. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis in depression. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10(9):1110–1115. doi: 10.1038/nn1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kolber BJ, et al. Central amygdala glucocorticoid receptor action promotes fear-associated CRH activation and conditioning. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(33):12004–12009. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803216105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van der Laan S, de Kloet ER, Meijer OC. Timing is critical for effective glucocorticoid receptor mediated repression of the cAMP-induced CRH gene. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(1):e4327. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kaouane N, et al. Glucocorticoids can induce PTSD-like memory impairments in mice. Science. 2012;335(6075):1510–1513. doi: 10.1126/science.1207615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Evanson NK, Tasker JG, Hill MN, Hillard CJ, Herman JP. Fast feedback inhibition of the HPA axis by glucocorticoids is mediated by endocannabinoid signaling. Endocrinology. 2010;151(10):4811–4819. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Helfferich F, Palkovits M. Acute audiogenic stress-induced activation of CRH neurons in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus and catecholaminergic neurons in the medulla oblongata. Brain Res. 2003;975(1-2):1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)02509-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Figueiredo HF, Bodie BL, Tauchi M, Dolgas CM, Herman JP. Stress integration after acute and chronic predator stress: Differential activation of central stress circuitry and sensitization of the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenocortical axis. Endocrinology. 2003;144(12):5249–5258. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Karst H, Berger S, Erdmann G, Schütz G, Joëls M. Metaplasticity of amygdalar responses to the stress hormone corticosterone. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(32):14449–14454. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914381107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Perissi V, Jepsen K, Glass CK, Rosenfeld MG. Deconstructing repression: Evolving models of co-repressor action. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11(2):109–123. doi: 10.1038/nrg2736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotactic Coordinates. Orlando, FL: Academic; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Datson NA, et al. A molecular blueprint of gene expression in hippocampal subregions CA1, CA3, and DG is conserved in the brain of the common marmoset. Hippocampus. 2009;19(8):739–752. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29(9):e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sarabdjitsingh RA, Meijer OC, Schaaf MJM, de Kloet ER. Subregion-specific differences in translocation patterns of mineralocorticoid and glucocorticoid receptors in rat hippocampus. Brain Res. 2009;1249:43–53. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Claessens SEF, Daskalakis NP, Oitzl MS, de Kloet ER. Early handling modulates outcome of neonatal dexamethasone exposure. Horm Behav. 2012;62(4):433–441. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2012.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.