Abstract

It is well-established that subcompartments of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) are in physical contact with the mitochondria. These lipid raft-like regions of ER are referred to as mitochondria-associated ER membranes (MAMs), and they play an important role in, for example, lipid synthesis, calcium homeostasis, and apoptotic signaling. Perturbation of MAM function has previously been suggested in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) as shown in fibroblasts from AD patients and a neuroblastoma cell line containing familial presenilin-2 AD mutation. The effect of AD pathogenesis on the ER–mitochondria interplay in the brain has so far remained unknown. Here, we studied ER–mitochondria contacts in human AD brain and related AD mouse and neuronal cell models. We found uniform distribution of MAM in neurons. Phosphofurin acidic cluster sorting protein-2 and σ1 receptor, two MAM-associated proteins, were shown to be essential for neuronal survival, because siRNA knockdown resulted in degeneration. Up-regulated MAM-associated proteins were found in the AD brain and amyloid precursor protein (APP)Swe/Lon mouse model, in which up-regulation was observed before the appearance of plaques. By studying an ER–mitochondria bridging complex, inositol-1,4,5-triphosphate receptor–voltage-dependent anion channel, we revealed that nanomolar concentrations of amyloid β-peptide increased inositol-1,4,5-triphosphate receptor and voltage-dependent anion channel protein expression and elevated the number of ER–mitochondria contact points and mitochondrial calcium concentrations. Our data suggest an important role of ER–mitochondria contacts and cross-talk in AD pathology.

Keywords: AD mouse models, hippocampal neurons, human cortical brain tissue

Evidence for impaired mitochondrial function has been shown in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) patients as well as animal and cell models of AD (1). In addition to their crucial role in energy production through oxidative phosphorylation, mitochondria have central roles in apoptotic signaling, lipid synthesis, and intracellular calcium (Ca2+) buffering. The outer mitochondrial membrane is in contact with a subregion of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) referred to as mitochondria-associated ER membranes (MAMs). MAMs are intracellular lipid rafts that regulate Ca2+ homeostasis, metabolism of glucose, phospholipids, and cholesterol (2–6). Strikingly, all of these processes are altered in AD (7). The interplay between these two organelles has been studied extensively, and several MAM-associated proteins have been characterized (6, 8). Such proteins include multiple lipid synthesizing enzymes [e.g., phosphatidylserine synthase-1 (PSS1), fatty acid CoA ligase 4 (FACL4) (4, 5, 9), and proteins involved in Ca2+ signaling]. Ca2+ is essential for the bioenergetics of the mitochondria and transferred from the ER at MAM (3) by inositol-1,4,5-triphosphate receptors (IP3Rs; ER side) and voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC1; mitochondria side) to form bridging complexes (e.g., IP3R1-VDAC1) (10, 11). Another protein suggested to be involved in Ca2+ regulation at MAM is the σ1 receptor (σ1R). σ1R is a molecular chaperone located in the ER–mitochondria interface on both the ER side, where it is involved in calcium homeostasis by stabilizing IP3R type 3 (IP3R3) (12), and the mitochondrial side (13), where its function is less established. Additionally, phosphofurin acidic cluster sorting protein-2 (PACS-2) and mitochondrial dynamin-related fusion protein (Mfn2) have been described to be located at the ER–mitochondria interface. PACS-2 is a multifunctional vesicular sorting protein that controls membrane traffic, apoptosis, and ER–mitochondria tethering (14). Mfn2 has also been described to be involved in tethering (15) and regulation of mitochondrial dynamics.

One neuropathological hallmark in AD is accumulation of amyloid β-peptide (Aβ) in the brain. Aβ has been detected in mitochondria (16, 17), and we have previously shown that Aβ is imported into the mitochondria through the Tom40 protein pore (18). Recently, an increased ER–mitochondria connectivity was detected in human fibroblasts from individuals with familial AD (FAD) mutations in presenilin 1 (PS1), presenilin 2 (PS2), or amyloid precursor protein (APP) as well as fibroblasts from individuals with sporadic AD (2). In agreement, similar results were obtained in neuroblastoma cells expressing PS2 FAD mutation (19). The increased connectivity was further manifested by up-regulated MAM function, which was shown by enhanced phospholipid and cholesterol metabolism (2) and calcium shuttling (19). If MAM in the brain responds in a similar way has not been investigated previously.

We identified MAM structures uniformly distributed in neurons as well as synapses. We observed a distinct increase in the expression of MAM-associated proteins in postmortem AD brain and APPSwe/Lon mice as well as elevated contact points between ER and mitochondria in primary hippocampal neurons after Aβ exposure. The increased contact points between the two organelles after Aβ exposure caused augmented ER-to-mitochondria Ca2+ transfer in neuroblastoma cells.

Results

ER–Mitochondria Contacts in Neuronal Tissue.

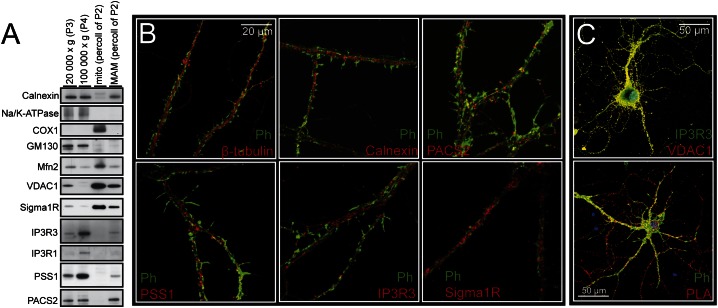

The contacts between ER and mitochondria are dynamic, and electron microscopic observations have revealed diverse MAM structures in cells originating from different organs (8). For example, ER tubules can form a single contact covering ∼10% of the mitochondrial surface (6). There are also structures covering approximately one-half (20) or even completely enveloping the mitochondrion (21). Despite the established importance of neuronal ER–mitochondria communication (22–24), there is limited research describing MAM structures in neurons. Here, EM analysis revealed close contact between ER and mitochondria in mouse hippocampal tissue (Fig. 1A), cultured mouse hippocampal neurons (Fig. 1B), and synaptosomal preparations (Fig. 1C). ER protrusions covering ∼10% of mitochondrial surface were the most frequent MAM structure observed. PSS1, PACS-2, IP3Rs, σ1R, Mfn2, and VDAC1 are all proteins previously shown to be localized to the ER–mitochondria interface in a variety of organs (8). Here, Western blot analysis also revealed expression of MAM-associated proteins in mouse brain. PSS1, PACS-2, and IP3Rs resided on the ER side, whereas σ1R, Mfn2, and VDAC1 proteins were mainly located in mitochondria (Fig. 2A). In the MAM fraction, we detected a higher expression of IP3R3 compared with IP3R1 (Fig. 2A). These results are consistent with findings showing that IP3R3 strongly colocalizes with mitochondria (25) and has the most profound effects on mitochondrial Ca2+ concentration. Ca2+ signaling through IP3R3 has been shown to be regulated by σ1R (12, 26). We detected σ1R in fractions of both MAM and mitochondria (Fig. 2A). This finding is in agreement with the work by Klouz et al. (13), which also found σ1R in the mitochondria. Immunocytochemical (ICC) staining and confocal microscopy showed that PSS1, PACS-2, IP3R3, σ1R, and VDAC1 are uniformly distributed in hippocampal neurons in both neurites (Fig. 2B) and soma (Fig. S1). IP3R3 showed substantial overlap with VDAC1, indicating that ER and mitochondrial membranes are in close proximity (Fig. 2C, Upper). In addition to ICC staining, the proximity ligation assay (PLA) was used. It verified that IP3R3 is indeed in close proximity (<40 nm) with VDAC1, which was previously shown for IP3R1 (10) (Fig. 2C, Lower). Thus, the previously described MAM-associated proteins PSS1, PACS-2, IP3R3, σ1R, Mfn2, and VDAC1 are also located in the ER–mitochondria interface in the brain, and IP3R3-VDAC1 is part of an ER–mitochondrial bridging complex.

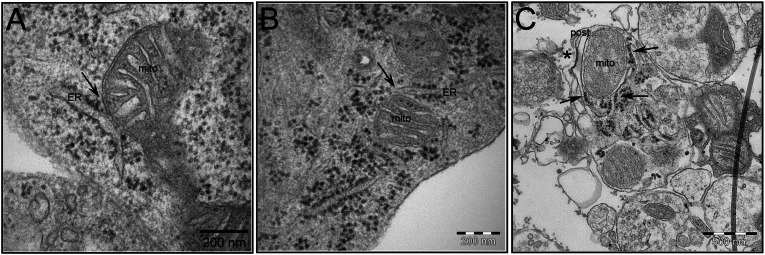

Fig. 1.

EM pictures of the ER–mitochondria contact point in mouse brain tissue and hippocampal neurons. MAM structures are indicated by arrows in (A) embryonic day 16 mouse hippocampal tissue, (B) primary mouse hippocampal neurons, and (C) synaptosomes prepared from adult mouse brain. The synaptic cleft and postsynapse are indicated by * and post, respectively. (Scale bars: A and B, 200 nm; C, 500 nm.)

Fig. 2.

Analysis of MAM-associated proteins. Western blot analysis of subcellularly fractionated mouse brain and ICC staining of hippocampal neurons. (A) Mouse brain homogenate was fractionated into 20,000 × g (P3) containing, for example, plasma membrane, 100,000 × g (P4) containing, for example, ER, mito (percoll of P2), and MAM (percoll of P2); 25 µg protein from each fraction were loaded onto the gel. Markers for subcellular fractions were calnexin (ER), Na/K-ATPase (plasma membrane), COX1 (inner mitochondrial membrane), and GM130 (Golgi). (B) Confocal microscopy of neurons stained with phalloidin (Ph; spines), β-tubulin (neuronal marker), calnexin (ER), and MAM-associated proteins (PACS-2, PSS1, IP3R3, and σ1R). 100× objective. (C, Upper) Distribution of IP3R3 (green; ER side) and VDAC1 (red; mitochondrial side). (C, Lower) PLA signals (reds dots) show close proximity between IP3R3 and VDAC1, indicating interactions between ER and mitochondrial membranes.

σ1R and PACS-2 Knockdown Causes Degeneration of Hippocampal Neurons.

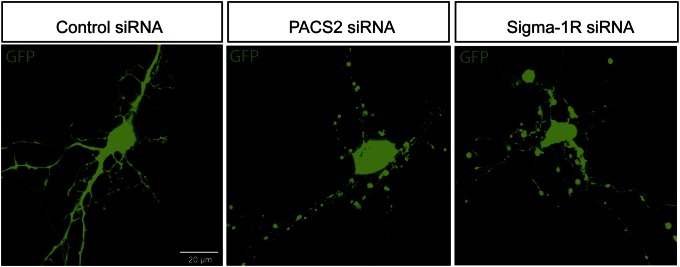

Previous research shows that knockdown of PACS-2 in A7 melanoma cells causes loss of MAM–mitochondria coupling and Ca2+ signaling (14). Knockdown of σ1R in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells causes decreased survival (12). Here, the importance of proper ER–mitochondria interaction in neurons and glia was investigated using siRNA knockdown of PACS-2 or σ1R in mouse primary hippocampal cultures containing neurons and astrocytes (Fig. 3 and Fig. S2C). Cells were transfected with control siRNA, σ1R siRNA, or PACS-2 siRNA together with GFP using a Magnetofector system. Transfected hippocampal neurons expressing GFP were analyzed using confocal microscopy. Hippocampal neurons transfected with control siRNA showed long robust projections, whereas neurons transfected with either σ1R or PACS-2 siRNA degenerated 16 h after treatment (Fig. 3). Caspase-3 activity was detected in neurons transfected with either σ1R or PACS-2 siRNA, indicating activation of apoptosis (Fig. S2A). The knockdown efficiency was confirmed by Western blot analysis in blastocyst-derived (BD8) cells treated with the same siRNAs (Fig. S2B). BD8 cells were used, because the transfection efficiency of the hippocampal neurons was too low to be suitable for Western blot analysis. Similarly, astrocytes, stained with GFAP (marker for astrocytes), were progressively degenerating after transfection (Fig. S2C). Thus, knockdown of PACS-2 and σ1R independently caused degeneration of hippocampal neurons and astrocytes, showing the importance of proper function of these MAM-associated proteins.

Fig. 3.

MAM-associated protein depletion causes degeneration of hippocampal neurons. Hippocampal neurons were transfected with AllStar negative control siRNA or siRNA to PACS-2 or σ1R (30 nM) together with pEGFP-N1 vector (0.4 ng/µL). Live cell images taken 16 h after transfection.

Altered Expression of PSS1, PACS-2, and σ1R in Human AD Brain and the APPSwe/Lon Mouse Model.

Next, we investigated the expression of PSS1, PACS-2, and σ1R proteins. Overview pictures taken of mouse brain sections revealed widespread distribution of MAM-associated proteins in WT mice, which is shown here by PSS1 staining (Fig. S3A). Higher magnification of the CA1 region of hippocampus clearly showed neuronal localization for PSS1, PACS-2, and σ1R in WT mice (Fig. S3B). Next, we investigated the expression levels of PSS1, PACS-2, and σ1R at different disease stages. For this purpose, we used APPSwe/Lon and APPArc mouse models as well as human postmortem cortical brain tissue. The APPSwe/Lon mouse model overexpresses the Swedish (K670N/M671L) and London (V717I) mutations and progressively accumulates a large quantity of amyloid plaques (27). Meanwhile, the APPArc mouse model containing an intra-Aβ mutation at E693G has a less aggressive pathology with mainly diffuse Aβ deposits (28). Disease progression was followed in the APPSwe/Lon mouse model, in which Western blot analysis was performed at different time points (i) before Aβ deposition (2 mo of age), (ii) at mild Aβ pathology (6 mo of age), and (iii) at severe Aβ pathology (10 mo of age). In the APPArc mouse model, the expression of PSS1, PACS-2, and σ1R proteins was analyzed only at a late disease stage (12 mo of age).

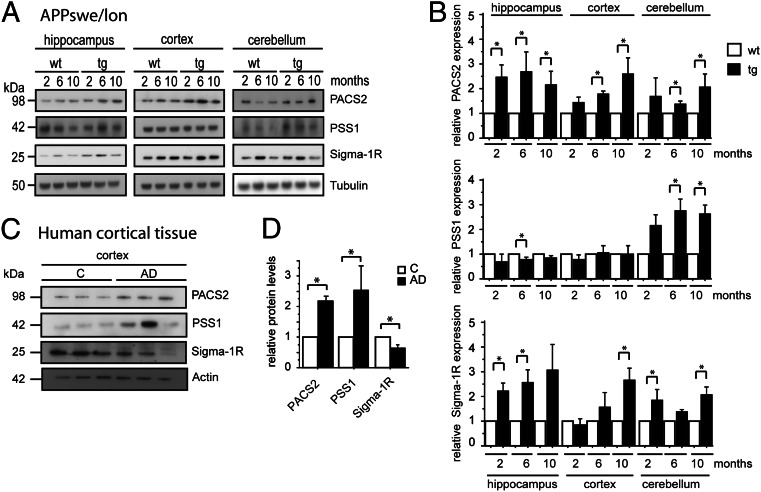

In the APPSwe/Lon mouse, the expression levels were analyzed in hippocampus, cortex, and cerebellum (Fig. 4A). Statistical analysis revealed that PACS-2 levels were higher in all brain regions from APPSwe/Lon mice compared with WT mice (Fig. 4B). The PACS-2 levels were increased in hippocampus already from 2 mo of age, whereas the increase started at 6 mo in cortex and cerebellum. A similar pattern was detected for σ1R, which also started to increase significantly in hippocampus at 2 mo of age. In contrast, PSS1 levels were only significantly increased in cerebellum (Fig. 4B). Importantly, for PACS-2 and σ1R, the alterations in protein expression occurred already before plaque formation.

Fig. 4.

MAM-associated protein expression is altered in AD and AD mouse model. Western blot quantification of expression of MAM-associated proteins in (A and B) the APPSwe/Lon mouse brain (2, 6, and 10 mo old) and (C and D) the human cortical postmortem brain tissue. Data were compared using Mann–Whitney u test (APPSwe/Lon: mean ± SD, n = 4; human cortical brain tissue: mean ± SEM, n = 3; *P < 0.05). Data were normalized to (B) tubulin or (D) actin.

Opposite of the APPSwe/Lon mice, no significant differences in MAM protein expression were detected in hippocampus, cortex, or cerebellum isolated from APPArc mice at the age of 12 mo (Fig. S3 C and D). The discrepancy between these two mouse models might be explained by the different properties of the Aβ peptides formed, Aβ (in APPSwe/Lon) and AβArc (in APPArc). The Arctic mutation is situated inside Aβ at position E693G and enhances protofibril formation (29) without affecting fibrillization rate. The APPArc mice display subtle cognitive decline, whereas the APPSwe/Lon mice show a more aggressive disease progression. Also, the localization of the neuropathological alterations is different between the two models: in the APPArc mice, the lesions are mainly detected in the subiculum, which is in contrast to APPSwe/Lon mice, where Aβ deposits are spread throughout the neocortex (30).

The analysis of MAM-associated proteins in human postmortem cortical tissue (three controls and three AD cases) revealed increased PSS1 and PACS-2 levels and decreased σ1R expression levels in the AD cases compared with control cases (Fig. 4 C and D).

PSS1, PACS-2, FACL4, and σ1R mRNA Levels Are Stable in the APPSwe/Lon Mouse Model.

For comprehensive analysis, we also included an in situ hybridization assay of mRNAs in the APPSwe/Lon mouse model. The quantification revealed similar levels and distribution patterns of PACS-2, PSS1, σ1R, and FACL4 mRNA (Fig. S4) in visual cortex, frontal cortex, and hippocampus at 2, 6, and 10 mo of age. A significant increase in PSS1 mRNA was detected in frontal cortex at 6 mo of age in the APPSwe/Lon mouse model compared with WT. However, the overall steady mRNA expression pattern observed comparing APPSwe/Lon with WT mice implicates that the augmented protein expression, detected by Western blot analysis, is most likely caused by protein stabilization, increased translation of already existing mRNA, and/or decreased protein degradation.

Phospholipid Metabolism Is Still Intact in Human AD Brain and the APPSwe/Lon Mouse Model.

MAM is central in lipid synthesis, especially phospholipid synthesis. Phosphatidylserine (PtdSer) is transported at MAM from ER into mitochondria, where it is converted by phosphatidylserine decarboxylase into phosphatidylethanolamine (PtdEtn), which in turn, is transported back to ER for conversion into phosphatidylcholine, a major component of biological membranes. Recently, a more rapid conversion of PtdSer to PtdEtn was found in PS1-KO, PS2-KO, and double KO mouse embryonic fibroblast cell lines and fibroblasts from FAD and sporadic AD patients (2). On the contrary, in AD brain, reduced levels of PtdEtn have been detected (31). Here, we studied lipid levels in the APPSwe/Lon mouse model and human AD cortical tissue. Lipids were extracted from human AD and control cortical brain mitochondria as well as APPSwe/Lon mice brain mitochondria of 2-, 6-, and 10-mo-old animals. The levels of phosphatidylcholine, PtdSer, and cardiolipin were analyzed by thin liquid chromatography, and the results revealed no differences in lipid composition in the human or mouse material (Fig. S5). With this method, no changes in lipid metabolism could be detected, which might suggest intact lipid metabolism in AD cortical brain tissue and the APPSwe/Lon mouse model.

Aβ Increases Contact Points Between ER and Mitochondria in Primary Hippocampal Neurons.

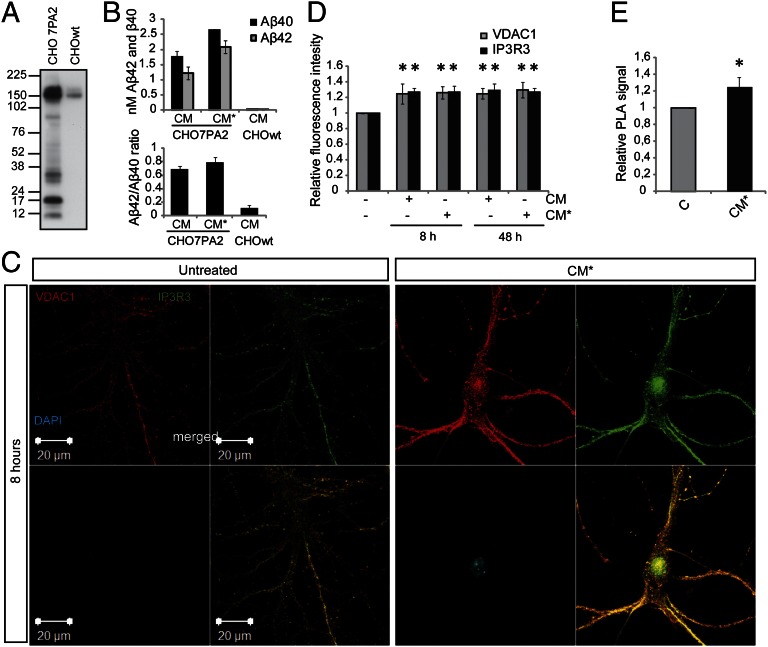

Cellular stress (e.g., ER stress) has been shown to modulate the interaction between ER and mitochondria. Bravo et al. (32) showed that ER stress induced by tunicamycin caused increased ER–mitochondrial coupling, Ca2+ transfer, and mitochondrial metabolism. To investigate the effect of Aβ exposure on ER–mitochondrial contact points, we exposed primary hippocampal neurons to conditioned medium (CM) from CHO7PA2 cells expressing the FAD mutation, APPV717F (Indiana mutation). CHO7PA2 CM (16 h) contains naturally occurring oligomeric Aβ species and no fibrils (33). CHO7PA2 cells express high levels of APPV717F (Fig. 5A), and the CM generated after incubation with 8 (CM) or 4 mL (CM*) neurobasal medium for 16 h contained ∼2.5 or 4.5 nM total Aβ (Aβ40 + Aβ42), respectively (Fig. 5B). These concentrations are thought to resemble physiological conditions (34). Hippocampal neuronal cultures were subsequently exposed to CM and CM* for 8 or 48 h. As a control, immunodepleted CHO7PA2 medium was used.

Fig. 5.

Aβ exposure elevates the expression of MAM-associated proteins and increases ER–mitochondrial contacts in hippocampal neurons. (A) Western blot of APP expression in CHO7PA2 cells and CHOwt cells. (B) Aβ levels in the CM at two concentrations: 2.5 (CM) and 4.5 nM (CM*) Aβ40 + Aβ42. (C) Confocal images acquired using the same experimental settings show VDAC1 (red) and IP3R3 (green) fluorescence intensity in untreated and CM*-treated (8 h) hippocampal neurons. (D) Quantification of fluorescence intensity of VDAC1 and IP3R3 after exposure to CM and CM* for 8 and 48 h. Data were compared using ANOVA followed by Games/Howell posthoc test (mean ± SD, n = 4; *P < 0.05). (E) For quantification of VDAC1 and IP3R3 interaction, we performed PLA on 8-h CM*-treated hippocampal neurons. The fluorescent spots (PLA signals) obtained using Duolink detection fluorophore Far-red ex644 were analyzed using Duolink Imaging Tool software. Data were compared using Mann–Whitney u test (mean ± SD, n = 3; *P < 0.05).

The effect of Aβ on ER–mitochondria contact points was analyzed in primary hippocampal neurons stained with IP3R3 (MAM) and VDAC1 (mitochondria) antibodies (Fig. 5C). To investigate fluorescence intensity, we used the same instrumental setting for acquiring all pictures. Aβ treatment induced an increase in both IP3R3 (green) and VDAC1 (red) immunofluorescence (Fig. 5 C and D) along with increased colocalization (yellow) (Fig. 5C). The increase in ER–mitochondria contact points was verified using PLA technology. Because the distance between ER and mitochondria is ∼20–40 nm (6) and PLA detects proteins located <40 nm away from each other, we used the IP3R3-VDAC1 pair to study the number of contact points after exposure to Aβ. A significant increase in PLA signal was observed after Aβ treatment (Fig. 5E). In conclusion, the data suggest that the expressions of VDAC1 and IP3R3 proteins increase after Aβ treatment and that the newly synthesized proteins take part in new contact points formed between ER and mitochondria. Thus, ER–mitochondria protein augmentation is not only observed at pathological conditions as detected in AD brain or in the APPSwe/Lon mouse model but also, after exposure to nanomolar concentrations of oligomeric Aβ.

Aβ and σ1R Agonist Treatment Increases Ca2+ Transfer from ER to Mitochondria.

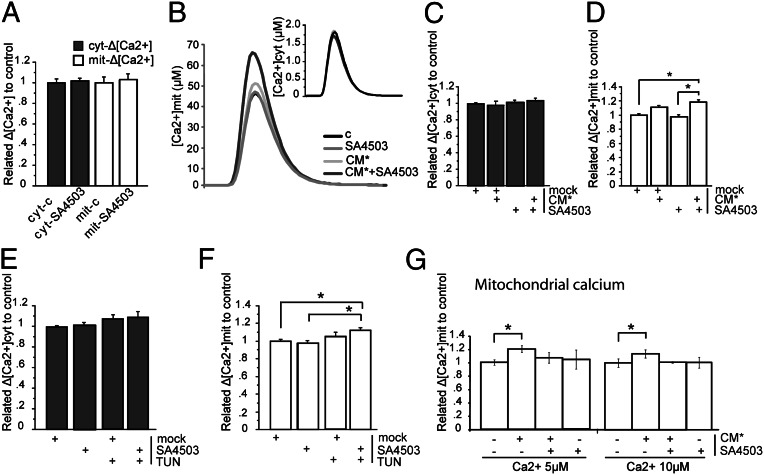

ER stress has previously been shown to influence the ER–mitochondria coupling and their Ca2+ cross-talk (32). To detect changes in Ca2+ shuttling after ER stress, the experiments were performed at an early time point (4 h), because prolonged stress abolished the effect (32). Ca2+ release from ER through IP3R3 has been previously shown to be regulated by σ1R (12). Therefore, experiments were conducted in the presence or absence of a σ1R agonist (SA4503 Cutamesine, 1 μM). To study the influence of Aβ on the Ca2+ machinery on both ER and mitochondrial sides, we used two experimental settings: one in which Ca2+ shuttling from ER to mitochondria after bradykinin stimulation (100 nM) was measured and one where the mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake machinery was separated from ER–Ca2+ release in plasma membrane-permeabilized cells. SH-SY5Y cells expressing cytosolic or mitochondrial aequorins were exposed to SA4503 alone for 24 h to study if this treatment per se influenced cytosolic or mitochondrial Ca2+ handling. The results revealed that neither cytosolic nor mitochondrial Ca2+ response to bradykinin stimulation was affected (Fig. 6A). Cell incubation for 4 h with CM* (Aβ, 4.5 nM) or tunicamycin (TUN; 1 µg/mL) in absence or presence of SA4503 showed no effect on cytosolic Ca2+ responses (Fig. 6 B and C). However, mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake was significantly increased after cotreatment with Aβ and SA4503 (Fig. 6 B and D). Similar results were obtained from TUN ± SA4503 cotreatment (Fig. 6 E and F). A possible explanation for such an effect would be that Aβ increases the intrinsic capacity of mitochondria to take up Ca2+. We explored this possibility by using the second experimental approach measuring mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake in digitonin-permeabilized cells bathed with an intracellular-like buffer set at different Ca2+ levels (micromolar). Under these conditions, the mitochondrial Ca2+ peaks were significantly increased at all Ca2+ concentrations tested by the Aβ treatment, suggesting a direct effect of the peptide on the molecular machinery responsible for mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake (Fig. 6G). Interestingly, when cells were treated with Aβ combined with the σ1R agonist, the increased mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake in permeabilized cells induced by Aβ alone was abolished (Fig. 6G). Thus, Aβ promotes Ca2+ uptake mechanisms on the mitochondrial side, whereas SA4503 combined with Aβ has dual effects both promoting ER Ca2+ release and inhibiting mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake.

Fig. 6.

Aβ exposure increases the Ca2+ shuttling from ER to mitochondria. Cytosolic and mitochondrial [Ca2+] measured in SH-SY5Y cells. (A) The σ1R agonist SA4503 does not affect cyt-Δ [Ca2+] or mit-Δ [Ca2+]. (B) Representative figure of Ca2+ peaks after treatment with SA4503 and CM* alone or combined. (C) Nanomolar concentrations of Aβ ± SA4503 do not increase cyt-Δ [Ca2+]. (D) Nanomolar concentrations of CM* + SA4503 increase ER to mitochondria Ca2+ transfer. (E) Treatment with TUN ± SA4503 does not increase cyt-Δ [Ca2+]. (F) Treatment of TUN combined with SA4503 increased ER to mitochondria Ca2+ transfer. (G) CM* increased mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake from cytosol (here exchanged with buffer containing fixed [Ca2+]). Data were compared using ANOVA and Games/Howell posthoc test (mean ± SEM, n > 4; *P < 0.05). Mock, DMSO.

Discussion

The close contact points between ER and mitochondria at specialized regions of ER (i.e., MAMs) are important for, for example, lipid synthesis and Ca2+ handling and have previously been described in several cell models (3). In neurons, the interaction between ER and mitochondria in synapses has been postulated to shape intracellular Ca2+ signals and modulate synaptic and integrative neuronal activities (22). Here, we report that the neuronal MAM structure is uniformly distributed throughout hippocampal neurons, and it also exists in synapses and appears as short ER stretches connected to the mitochondrial surface. MAM seems to harbor physiological functions with particular importance for neuronal integrity, because knockdown of PACS-2 or σ1R resulted in degeneration. The atrophy started distally and advanced to the cell body, which is a fashion resembling dying-back neuropathy (35). Also, astrocytes responded in a similar manner, which was not unexpected; the astrocytes most likely are heavily dependent on a functional MAM for, for example, cholesterol metabolism, because the astrocytes are the net producers of cholesterol in the brain (36).

Up-regulated function of MAM and increased ER–mitochondrial interaction have recently been observed in human fibroblasts from familial and sporadic AD patients (2). Here, data gathered from neuronal cells exposed to Aβ and human AD cortical tissue as well an AD mouse model robustly revealed that this region, indeed, is affected by AD pathogenesis. We could detect an up-regulation of MAM-associated proteins in the APPSwe/Lon mouse model at 2, 6, and 10 mo of age. Hence, alterations occur already at 2 mo of age before plaques are visible. Also, in the human AD cortical tissue, up-regulation was detected; however, one of the MAM-associated proteins, σ1R, was significantly decreased. In concordance, decreased levels of σ1R have been detected postmortem in the hippocampus (37) and in living patients already at an early AD disease stage using imaging techniques (38). The discrepancy in σ1R expression between the mouse model and the human tissue might be explained by pathology dissimilarities, because the mouse model lacks several human pathogenic hallmarks. In an early stage of AD, the increased expression of ER–mitochondria interface proteins may reflect a stress response, where neurons try to maintain proper functions in this crucial region.

The data from the AD mouse model APPArc raised yet another dimension to the complexity of the mechanism involved in MAM region regulation, because no alteration in MAM was detected. The divergence of impact on MAM observed in the APPSwe/Lon vs. APPArc mouse models might be explained by the milder pathology in the APPArc mouse model. APPArc has an intra-Aβ mutation causing predominately diffuse Aβ deposits in restricted areas (28, 29). It is interesting that an intra-Aβ mutation vs. mutations at β- and γ-cleavage sites generate such diverse MAM phenotypes. These findings suggest that certain Aβ properties are necessary for regulation of MAM and need additional investigation.

Aβ exposure of primary hippocampal neurons affected the MAM region by increasing both the MAM-associated protein expression and the number of contact points between ER and mitochondria, here revealed by studying the IP3R3-VDAC1 bridging complex. Moreover, we found Ca2+ regulatory mechanisms on the mitochondrial side to particularly be affected by Aβ. We investigated these mechanisms by using two different experimental settings: one studying the transfer of Ca2+ from ER to the mitochondria (intact cells) and one studying mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake independent of ER–Ca2+ release (plasma membrane-permeabilized cells). Accordingly, Aβ has been shown to bind and affect several proteins in the inner mitochondrial membrane of the mitochondria (e.g., cyclophilin D and COX) (39, 40). Calcium release from ER through IP3R3 has previously been shown to be regulated by σ1R (12). Our data suggest that the σ1R agonist (SA4503) could regulate the Ca2+ machinery on both sides during stress (induced by Aβ or TUN) in opposite ways. The dual effect of SA4503 treatment might be explained by the subcellular localization of σ1R to both mitochondria and MAM, implying different functions of σ1R when located on the mitochondrial vs. ER side. Our results indicate diverse functions of σ1R at the mitochondria–ER interface which need additional investigation. As a source for Aβ, we used the well-characterized CHO7PA2-CM containing nanomolar concentrations of naturally occurring oligomeric Aβ (33) that resembles the physiological concentrations to which neurons are exposed in the brain (34). It should be emphasized that, in our model system, we applied Aβ on the outside of the cells. Thus, Aβ could initiate signal transduction pathways and/or be internalized and trafficked inside the neurons. It may be speculated that Aβ is taken up by cells through endocytosis and reaches the ER–mitochondria region by transport in endosomes. Soluble Aβ in CHO7PA2-CM has previously been shown to inhibit long-term potentiation in hippocampal slices (41). Here, we show the direct or indirect influence on MAM, suggesting yet another physiological function of Aβ.

In conclusion, we show that nanomolar concentrations of oligomeric Aβ regulate ER–mitochondrial communication and mitochondrial Ca2+. The findings of augmentation of MAM-associated proteins in AD brain, APPSwe/Lon mice, and primary neurons exposed to Aβ indicate that this region is implicated in AD pathogenesis and might harbor potential targets for new treatment strategies.

Materials and Methods

Additional details are given in SI Materials and Methods.

Cell Culture and Transfection.

Primary hippocampal neurons (embryonic days 16–17) were cultured in Neurobasal medium + B27 supplement in the presence of a surrounding feeder layer of cortical neurons (42, 43). BD8 cells were grown according the work in ref. 44. Cells were transfected using magnetic-assisted transfection. GFP and siRNA were mixed in Opti-MEM and NeuroMag according to the manufacturer’s instructions (OZ Biosciences).

Brain Tissue.

APPSwe/Lon and APPArc mouse models were generated as described in refs. 45 and 28, respectively. Human brain tissue was provided by the Brain Bank at Karolinska Institutet.

Subcellular Fractionation and MAM Purification.

To isolate MAM, mouse brains from adult C57B6/J mice were rapidly taken and prepared as previously described (46). Synaptosomes were isolated according to ref. 47.

PLA.

The interaction between IP3R3 and VDAC1 was analyzed in hippocampal neurons by PLA technology performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Olink Bioscience).

Aequorin Ca2+ Measurements.

Aequorin measurements were carried out in SH-SY5Y cells as previously described (19, 48).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor D. J. Selkoe for CHO7PA2 cells, Professor D. M. Walsh for AW7 antibody, Dr. R. Urfer for σ1R agonist SA4503, and Professor M. Windisch for APPSwe/Lon mouse brain tissue. We also thank Dr. K. Hultenby for performing the EM, Professor Å. Wislander for discussions about thin liquid chromatography, and Dr. L. Tjernberg and Dr. S. Schedin Weiss for advice regarding PLA. This study was supported by The Swedish Research Council, the Gun and Bertil Stohnes Foundation, the Lundbecks Foundation, the Swedish Alzheimer Foundation, the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, The Swedish Brain Power Program, the Karolinska Institutet Strategic Neuroscience Program, and Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (Portugal).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1300677110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Ankarcrona M, Mangialasche F, Winblad B. Rethinking Alzheimer’s disease therapy: Are mitochondria the key? J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;20(Suppl 2):S579–S590. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-100327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Area-Gomez E, et al. Upregulated function of mitochondria-associated ER membranes in Alzheimer disease. EMBO J. 2012;31(21):4106–4123. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hayashi T, Rizzuto R, Hajnoczky G, Su TP. MAM: More than just a housekeeper. Trends Cell Biol. 2009;19(2):81–88. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rusiñol AE, Cui Z, Chen MH, Vance JE. A unique mitochondria-associated membrane fraction from rat liver has a high capacity for lipid synthesis and contains pre-Golgi secretory proteins including nascent lipoproteins. J Biol Chem. 1994;269(44):27494–27502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vance JE. Molecular and cell biology of phosphatidylserine and phosphatidylethanolamine metabolism. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 2003;75(2003):69–111. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(03)75003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Csordás G, et al. Structural and functional features and significance of the physical linkage between ER and mitochondria. J Cell Biol. 2006;174(7):915–921. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200604016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schon EA, Area-Gomez E. Is Alzheimer’s disease a disorder of mitochondria-associated membranes? J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;20(Suppl 2):S281–S292. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-100495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fujimoto M, Hayashi T. New insights into the role of mitochondria-associated endoplasmic reticulum membrane. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2011;292(2011):73–117. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-386033-0.00002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stone SJ, Vance JE. Phosphatidylserine synthase-1 and -2 are localized to mitochondria-associated membranes. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(44):34534–34540. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002865200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Szabadkai G, et al. Chaperone-mediated coupling of endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondrial Ca2+ channels. J Cell Biol. 2006;175(6):901–911. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200608073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rizzuto R, Duchen MR, Pozzan T. Flirting in little space: The ER/mitochondria Ca2+ liaison. Sci STKE. 2004;2004(215):re1. doi: 10.1126/stke.2152004re1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hayashi T, Su TP. Sigma-1 receptor chaperones at the ER-mitochondrion interface regulate Ca(2+) signaling and cell survival. Cell. 2007;131(3):596–610. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klouz A, et al. Evidence for sigma-1-like receptors in isolated rat liver mitochondrial membranes. Br J Pharmacol. 2002;135(7):1607–1615. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simmen T, et al. PACS-2 controls endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria communication and Bid-mediated apoptosis. EMBO J. 2005;24(4):717–729. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Brito OM, Scorrano L. Mitofusin 2 tethers endoplasmic reticulum to mitochondria. Nature. 2008;456(7222):605–610. doi: 10.1038/nature07534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Manczak M, et al. Mitochondria are a direct site of A beta accumulation in Alzheimer’s disease neurons: Implications for free radical generation and oxidative damage in disease progression. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15(9):1437–1449. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Caspersen C, et al. Mitochondrial Abeta: A potential focal point for neuronal metabolic dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease. FASEB J. 2005;19(14):2040–2041. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-3735fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hansson Petersen CA, et al. The amyloid beta-peptide is imported into mitochondria via the TOM import machinery and localized to mitochondrial cristae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(35):13145–13150. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806192105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zampese E, et al. Presenilin 2 modulates endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-mitochondria interactions and Ca2+ cross-talk. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(7):2777–2782. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100735108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Meis L, Ketzer LA, da Costa RM, de Andrade IR, Benchimol M. Fusion of the endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondrial outer membrane in rats brown adipose tissue: Activation of thermogenesis by Ca2+ PLoS One. 2010;5(3):e9439. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dai J, Kuo KH, Leo JM, van Breemen C, Lee CH. Rearrangement of the close contact between the mitochondria and the sarcoplasmic reticulum in airway smooth muscle. Cell Calcium. 2005;37(4):333–340. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mironov SL, Symonchuk N. ER vesicles and mitochondria move and communicate at synapses. J Cell Sci. 2006;119(Pt 23):4926–4934. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mironov SL, Ivannikov MV, Johansson M. [Ca2+]i signaling between mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum in neurons is regulated by microtubules. From mitochondrial permeability transition pore to Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(1):715–721. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409819200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pivovarova NB, Pozzo-Miller LD, Hongpaisan J, Andrews SB. Correlated calcium uptake and release by mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum of CA3 hippocampal dendrites after afferent synaptic stimulation. J Neurosci. 2002;22(24):10653–10661. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-24-10653.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mendes CC, et al. The type III inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor preferentially transmits apoptotic Ca2+ signals into mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(49):40892–40900. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506623200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu Z, Bowen WD. Role of sigma-1 receptor C-terminal segment in inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor activation: Constitutive enhancement of calcium signaling in MCF-7 tumor cells. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(42):28198–28215. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802099200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rockenstein E, Mallory M, Mante M, Sisk A, Masliaha E. Early formation of mature amyloid-beta protein deposits in a mutant APP transgenic model depends on levels of Abeta(1-42) J Neurosci Res. 2001;66(4):573–582. doi: 10.1002/jnr.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rönnbäck A, et al. Progressive neuropathology and cognitive decline in a single Arctic APP transgenic mouse model. Neurobiol Aging. 2011;32(2):280–292. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nilsberth C, et al. The ‘Arctic’ APP mutation (E693G) causes Alzheimer’s disease by enhanced Abeta protofibril formation. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4(9):887–893. doi: 10.1038/nn0901-887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ronnback A, et al. Amyloid neuropathology in the single Arctic APP transgenic model affects interconnected brain regions. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33(4):831.e811–831.e819. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pettegrew JW, Panchalingam K, Hamilton RL, McClure RJ. Brain membrane phospholipid alterations in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurochem Res. 2001;26(7):771–782. doi: 10.1023/a:1011603916962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bravo R, et al. Increased ER-mitochondrial coupling promotes mitochondrial respiration and bioenergetics during early phases of ER stress. J Cell Sci. 2011;124(Pt 13):2143–2152. doi: 10.1242/jcs.080762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walsh DM, et al. Naturally secreted oligomers of amyloid beta protein potently inhibit hippocampal long-term potentiation in vivo. Nature. 2002;416(6880):535–539. doi: 10.1038/416535a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cleary JP, et al. Natural oligomers of the amyloid-beta protein specifically disrupt cognitive function. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8(1):79–84. doi: 10.1038/nn1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dadon-Nachum M, Melamed E, Offen D. The “dying-back” phenomenon of motor neurons in ALS. J Mol Neurosci. 2011;43(3):470–477. doi: 10.1007/s12031-010-9467-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nieweg K, Schaller H, Pfrieger FW. Marked differences in cholesterol synthesis between neurons and glial cells from postnatal rats. J Neurochem. 2009;109(1):125–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.05917.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jansen KL, Faull RL, Storey P, Leslie RA. Loss of sigma binding sites in the CA1 area of the anterior hippocampus in Alzheimer’s disease correlates with CA1 pyramidal cell loss. Brain Res. 1993;623(2):299–302. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)91441-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mishina M, et al. Low density of sigma1 receptors in early Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Nucl Med. 2008;22(3):151–156. doi: 10.1007/s12149-007-0094-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Du H, et al. Cyclophilin D deficiency attenuates mitochondrial and neuronal perturbation and ameliorates learning and memory in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Med. 2008;14(10):1097–1105. doi: 10.1038/nm.1868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Crouch PJ, et al. Copper-dependent inhibition of human cytochrome c oxidase by a dimeric conformer of amyloid-beta1-42. J Neurosci. 2005;25(3):672–679. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4276-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li S, et al. Soluble Aβ oligomers inhibit long-term potentiation through a mechanism involving excessive activation of extrasynaptic NR2B-containing NMDA receptors. J Neurosci. 2011;31(18):6627–6638. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0203-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Choi DW, Maulucci-Gedde M, Kriegstein AR. Glutamate neurotoxicity in cortical cell culture. J Neurosci. 1987;7(2):357–368. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-02-00357.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fath T, Ke YD, Gunning P, Götz J, Ittner LM. Primary support cultures of hippocampal and substantia nigra neurons. Nat Protoc. 2009;4(1):78–85. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hedskog L, et al. β-Secretase complexes containing caspase-cleaved presenilin-1 increase intracellular Aβ(42)/Aβ(40) ratio. J Cell Mol Med. 2011;15(10):2150–2163. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01208.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hutter-Paier B, et al. The ACAT inhibitor CP-113,818 markedly reduces amyloid pathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron. 2004;44(2):227–238. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wieckowski MR, Giorgi C, Lebiedzinska M, Duszynski J, Pinton P. Isolation of mitochondria-associated membranes and mitochondria from animal tissues and cells. Nat Protoc. 2009;4(11):1582–1590. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dunkley PR, Jarvie PE, Robinson PJ. A rapid Percoll gradient procedure for preparation of synaptosomes. Nat Protoc. 2008;3(11):1718–1728. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brunello L, et al. Presenilin-2 dampens intracellular Ca2+ stores by increasing Ca2+ leakage and reducing Ca2+ uptake. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13(9B):3358–3369. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00755.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.