Abstract

Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) is a pleiotropic cytokine that becomes elevated in chronic inflammatory states such as hypertension and diabetes and has been found to mediate both increases and decreases in blood pressure. High levels of TNF-α decrease blood pressure, whereas moderate increases in TNF-α have been associated with increased NaCl retention and hypertension. The explanation for these disparate effects is not clear but could simply be due to different concentrations of TNF-α within the kidney, the physiological status of the subject, or the type of stimulus initiating the inflammatory response. TNF-α alters renal hemodynamics and nephron transport, affecting both activity and expression of transporters. It also mediates organ damage by stimulating immune cell infiltration and cell death. Here we will summarize the available findings and attempt to provide plausible explanations for such discrepancies.

Keywords: TNF-α, hypertension, natriuresis, TNF receptor, septic shock, transport, renal hemodynamics, blood pressure

Tumor Necrosis Factor-α in the Kidney: Synthesis and Secretion

tnf-α is a proinflammatory cytokine that was originally described as antitumorigenic (19, 60) and produced by immune cells like macrophages and lymphocytes (15, 105, 142); however, further studies revealed it is also produced by endothelial and epithelial cells (14, 43, 61, 66, 71, 98, 99, 101, 141, 160). TNF-α is expressed as a 26-kDa plasma membrane protein that is secreted into the extracellular space by the metalloproteinase TNF-α-converting enzyme (TACE, also called a disintegrin and metalloproteinase 17 or ADAM 17; Refs. 16, 76, 89). In solution, this 17-kDa protein forms homotrimers and activates two distinct receptors (151). Transmembrane TNF-α also forms trimers (136) and can activate TNF receptors. Moreover, the intracellular domain of transmembrane TNF is palmitoylated (148) and can be phosphorylated (111), providing an additional step for regulation of TNF-α release.

Infiltrating inflammatory cells (142), podocytes (119), mesangial cells (6, 13, 14, 74), and epithelial cells from proximal tubules (101, 113, 163, 164), thick ascending limbs (3, 35, 90, 156) and collecting ducts (140) are sources of TNF-α in the kidney. TNF-α increases in response to endotoxemia (26), lipopolysaccharide (LPS; Refs. 34, 40, 74, 90), angiotensin II (ANG II; Ref. 35), calcium-sensing receptor (CaSR) activation (3, 156), hypertension (32, 79), renal failure (115), glomerulonephritis (153), diabetic nephropathy (42, 100), and interstitial tubular nephritis (50, 94).

TNF-α production is augmented in proximal tubule cells in response to IL-1α but not IL-2 or IFNγ (161). This increase is inhibited by cycloheximide, suggesting that it is not due to increased TNF shedding from the membrane but rather enhanced protein synthesis.

In the thick ascending limb, CaSR activation stimulates Gi and Gq protein (3); this activates phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C, which in turn produces inositol triphosphate and diacylglycerol. Inositol triphosphate increases intracellular Ca, which forms a complex with calmodulin whereas diacylglycerol activates protein kinase C (PKC). These two convergent cascades lead to activation of calcineurin. Activated calcineurin dephosphorylates nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT), allowing translocation of this transcription factor to the nucleus and transcription of TNF-α (1, 3, 156). In particular, NFAT5 (also called Ton/EBP for tonicity element binding protein) has been shown to partially mediate the CaSR-induced increase in TNF-α expression (53) and is itself activated by changes in osmolality in renal cells (95); however, it is not known whether changes in osmolality induce TNF-α release by thick ascending limbs nor whether this TNF-α release is mediated via NFAT5.

TNF-α levels have been shown to increase in response to ANG II in thick ascending limbs (35) and podocytes (119). In podocytes, activation of both AT1 and AT2 receptors was responsible for this effect, with AT1 mediating the earlier phase and AT2 the later phase. ANG II activates PKC in the thick ascending limb (57, 128) and thus may increase NFAT translocation to the nucleus along with TNF-α gene transcription; however, it is still unclear whether PKC and NFAT mediate ANG II-induced increases in TNF-α expression in the thick ascending limb. In addition, TNF-α production is known to increase in response to LPS in thick ascending limbs and podocytes, particularly during endotoxemia.

Finally, TNF-α production in the kidney can be increased by infiltrating immune cells, especially macrophages (105, 142, 169). Increased innate immune activation, neutrophil and macrophage infiltration, and enhanced TNF-α production are observed in infections (83), cisplatin nephropathy (73, 114), diabetic nephropaty (38), antiglomerular basement membrane nephropathy (142), obstructive nephropathy (134), etc. In such situations stimuli for TNF-α production include activation of Toll-like receptor 4 in response to LPS (85), oxidative stress (30), antibody deposition, and complement activation (142, 159). In addition, dendritic cell, macrophage, and lymphocyte recruitment to the kidney is observed in lupus erythematosus and hypertension (27, 51, 96). The stimuli for their migration to the kidney and TNF-α production are likely increased reactive oxygen species and enhanced expression of endothelial adhesion molecules and chemokines by the kidney in response to elevations in renal-derived TNF-α. Inhibition of AT1 receptors (7, 121) as well as reactive oxygen scavenging (30) reduces renal-derived TNF-α, proinflammatory cytokine production, and immune cell infiltration and activation. Similarly, ANG II infusion increases leukocyte infiltration and production of inflammatory cytokines, all of which are prevented by blockade of TNF-α with etanercept (33, 96). These data indicate that endotoxins, ANG II, and reactive oxygen species stimulate TNF-α expression by the kidney; this in turn induces inflammatory cell recruitment and activation, which further increase TNF-α levels.

TNF-α Receptors

The actions of TNF-α are mediated by two distinct receptors: type 1 (TNFR1 or p55) and type 2 (TNFR2 or p75). Kinetically, TNF-α binding to TNFR1 shows slow dissociation, whereas it is 20–30 times faster with TNFR2 (48). Therefore, some have proposed that TNFR2 serves as a “local reservoir” of TNF-α, both providing readily available TNF-α for TNFR1 activation and operating as a “ligand passing” receptor in which TNFR2 captures TNF-α and passes it on to TNFR1. In addition, it has been shown that TNFR1 activation requires expression of TNFR2, which can form heterocomplexes with TNFR1 (28, 87, 107). Although the effects of soluble TNF-α may be mediated by either receptor, most of the actions of membrane-bound TNF-α are mediated by TNFR2 (47). TNFRs form homotrimers in the plasma membrane via their preligand assembly domain (22). TNFRs do not have an intrinsic catalytic property; rather, ligand binding causes a conformational change in the preassembled receptor that leads to recruitment of signaling proteins.

In healthy animals, TNFR1 and 2 have been found in the cortex in proximal tubules and collecting ducts as well as endothelial cells of the glomeruli and renal vasculature (8, 20). TNFR1 has also been found in vascular smooth muscle cells of the renal vasculature (20). However, TNFR expression varies in different diseases. In glomerulonephritic kidneys, TNFR2 expression was high in glomeruli and postcapillary venules of the cortex, whereas in obstructive nephropathy (which primarily affects tubules) TNFR2 staining was restricted to tubular epithelial cells (153). ANG II also increases TNFR1 and 2 expression in podocytes (119). Thus one would expect that if ANG II is elevated (under conditions like low-salt diet, renal vascular hypertension, etc.), then receptor expression would be elevated as well. Such data suggest that the cellular pattern of TNFR expression in the kidney could affect its response to TNF-α depending on its initial physiological/pathophysiological state.

TNF-α and Blood Pressure

The role of TNF-α in blood pressure regulation has been studied in several different models, with sometimes conflicting results. There are a number of reports showing that TNF-α either mediates or supports increases in blood pressure. In ANG II-infused hypertensive rats fed high-salt diet, etanercept delayed progression of hypertension. Protection appeared to be due to reduced renal damage, since proteinuria and monocyte/macrophage infiltration were diminished (33). In addition, infusion of ANG II for 2 wk failed to increase blood pressure in TNF-α knockout (KO) mice, but this was restored by replacement therapy with recombinant TNF-α (0.3 μg·kg−1·day−1; Ref. 131). In addition, Guzik et al. (51) showed that TNF-α production by T lymphocytes from ANG II-hypertensive mice was higher than in control mice and that etanercept infusion blunted ANG II-induced increases in blood pressure. These data seem to indicate that TNF-α mediates ANG II-dependent increases in blood pressure. Similarly, in a mouse model of lupus erythematosus etanercept infusion for 4 wk reduced blood pressure, albuminuria, glomerulosclerosis, and NF-κB activity, suggesting that TNF-α causes inflammation and mediates the increase in blood pressure (152).

Metabolic syndrome is characterized by the simultaneous presence of obesity, dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, and hypertension. It has been shown that elevated TNF-α levels are associated with the development of hypertension (63, 170). Etanercept treatment for 6 wk prevented the increase in blood pressure observed in insulin-resistant fructose-fed rats without affecting insulin sensitivity (147). TNF-α neutralization also restored maximum acetylcholine-induced relaxation in mesenteric arteries and restored nitric oxide synthase 3 (NOS3) expression (147).

TNF-α also appears to play a role in blood pressure regulation during pregnancy. In preeclampsia, plasma TNF-α is doubled (10, 25, 122), and infusing TNF-α for 5 days (<0.5 μg·kg−1·day−1) increases blood pressure in pregnant rats but not in virgin rats (80, 81). Blockade of TNF-α with etanercept reduced blood pressure. In addition, healthy endothelial cells incubated with serum from preeclamptic rats exhibited increased endothelin-1 release and this was prevented by etanercept (79). Similarly, infusion of a neutralizing anti-TNF antibody reduced blood pressure, albuminuria, and renal damage in a model of preeclampsia achieved by adoptive transfer of serum from preeclamptic women to pregnant mice (62).

Finally, TNF-α is increased is chronic kidney disease, which is characterized by progressive loss of renal function, renal injury, and hypertension (130, 139, 162). This disease can be mimicked by 5/6 nephrectomy, which also increases TNF-α release. In rats with renal failure, neutralizing TNF-α with soluble TNFR1 prevented the increase in blood pressure, reduced fibrosis, decreased macrophage infiltration and albuminuria, and restored the ratio of l-arginine to asymmetric dimethylarginine (139). It also restored expression of NOS3, endothelin-1, transforming growth factor-β macrophage chemoattractant protein, intercellular adhesion molecules, and vascular cell adhesion molecules (139).

However, there are also a number of reports indicating that TNF-α either plays no role or tends to reduce blood pressure. For example, in DOCA-salt hypertensive rats etanercept did not reduce blood pressure (32). Although it remains unclear why TNF-α blockade failed to afford protection in these rats, it could be due to the high systolic blood pressure, or it could simply be that TNF-α does not participate in this model of hypertension. Supporting this notion is the fact that the DOCA-salt model of hypertension is based on elevated mineralocorticoid levels, and the increase in blood pressure can be prevented with mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (44, 149). In addition, Muller et al. (96) showed that in a double-transgenic rat model of ANG II-dependent hypertension, in which human angiotensinogen and renin are expressed, etanercept did not alter blood pressure even though it reduced albuminuria and infiltration by inflammatory cells. The disparity with the previous report by Elmarakby et al. (33) in which TNF-α blockade delayed the increase in blood pressure in ANG II-induced hypertension could be explained by the following facts: 1) Muller et al. started anti-TNF treatment after rats were hypertensive whereas Elmarakby et al. started ANG II and etanercept at the same time; 2) the blood pressure in the double-transgenic rats was much higher than in those infused with ANG II; 3) Muller et al. only measured blood pressure at day 20 whereas Elmarakby et al. found that the blood pressure-lowering effect of etanercept took place from days 6 to 12 after the start of the anti-TNF treatment; and 4) Muller et al. used regular salt diet while Elmarakby et al. fed the rats high-salt diet.

Using a different anti-TNF treatment, Ferreri et al. (36) showed that in ANG II-induced hypertension a neutralizing anti-TNF antibody induced an acute increase in blood pressure after 30 min of infusion. The explanation for this discrepancy is unclear but is likely the duration of the study. In reports where TNF-α was found to mediate increases in blood pressure, animals were studied for weeks rather than hours or days. These investigators later showed that infusion of 1.6 μg·kg−1·min−1 ANG II raised blood pressure higher in TNFR1 KO mice than in wild-type (WT) at 2, 4, and 5 days of ANG II infusion. Proteinuria, water intake, glomerular filtration rate (GFR), and urinary output were also increased whereas Na excretion was reduced, suggesting increased renal Na reabsorption. These results are in stark contrast to those shown in TNF-α KO mice (131) where the increase in blood pressure induced by infusion of 1 μg·kg−1·min−1 ANG II was blunted compared with WT mice and to those shown by Guzik et al. (51) where etanercept reduced the increase in blood pressure induced by infusion of ANG II at a rate of 490 ng·kg−1·min−. While the explanation is not clear, it could be due to the different doses of ANG II used (and hence possibly different mechanisms leading to hypertension), due to the background of the mice (C57Bc/6J vs. B6129SF2/J), or because infusion of ANG II in TNFR1 KO mice increases both TNF-α and TNFR2 (24). This later point raises the possibility that the observed phenotype is the result of hyperactive TNFR2 as opposed to a lack of TNFR1 and TNFR2 has been shown to mediate renal macrophage infiltration, glomerulosclerosis, and interstitial fibrosis in ANG II-induced hypertension (129).

In contrast to the link between TNF-α and hypertension, TNF-α also appears to play a role in the hypotension associated with septic shock (145). This is a complex pathological condition that results from an exaggerated and deregulated host response to infection with extreme increases in TNF-α levels. Activation of the innate immune response with increased neutrophil and macrophage tissue infiltration is observed. However, attempts to reduce the immune response by blocking the action of TNF or inhibiting downstream mediators have provided conflicting results. Indeed, in animals pretreatment with TNF-α blockers like neutralizing antibodies (37, 146) or soluble receptor fusion constructs (150) before the onset of sepsis has shown a positive outcome with a lower mortality rate; however, in humans numerous trials have failed to demonstrate a beneficial effect of anti-TNF therapy in septic patients (4, 41, 112). Failure of this approach is partly attributed to the need of a competent immune system to withstand the systemic infection and partly to the fact that in humans treatment is started after sepsis has been initiated. TNF-α decreases blood pressure in septic shock by numerous mechanisms, including reductions in cardiac contractility (77, 165), increased endothelial permeability (5, 97), exaggerated NO production (72), resistance to catecholamines (17, 158), increased sodium excretion (126), and decreases in vasopressin receptors and aquaporin 2 (58).

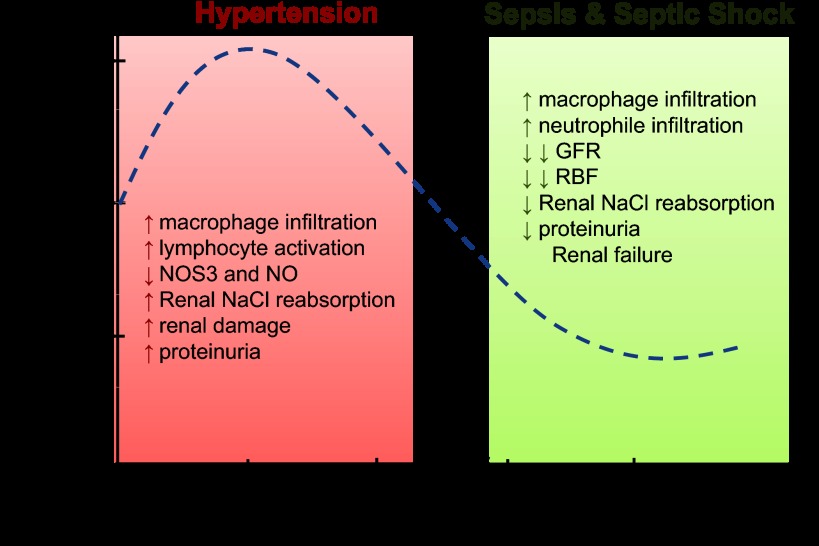

Why TNF-α is implicated as a causative agent of both increases and decreases in blood pressure is not clear. When considered in toto, most evidence seems to support a role for chronic moderately elevated concentrations of TNF-α in hypertension, as the opposing reports have alternative explanations. This view is also supported by the fact that nearly all studies show that neutralizing TNF-α protects against renal damage, which in itself is a cause of hypertension. In contrast, higher concentrations of TNF-α are associated with decreases in blood pressure and more severe inflammation. In these cases the decrease in blood pressure is likely dependent on both renal and nonrenal systemic actions of TNF-α (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Diagram representing the effects of increasing levels of TNF-α in renal function and the hypothetical effect on blood pressure. Increases of 1- to 2-fold in TNF-α are present in hypertension whereas increases of TNF-α >5 times are observed in septic shock. Dashed line represents a theoretical relationship between TNF-α levels and blood pressure. NO, nitric oxide; NOS3, nitric oxide synthase type 3; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; RBF, renal blood flow.

Renal Hemodynamics

At high doses (≥0.6 mg/kg), infusion of TNF-α in healthy rats lowers blood pressure. This is accompanied by lower GFR and renal blood flow (RBF); however, renal vascular resistance (RVR) increases (20, 127). The decreases in GFR and RBF can be explained by the drop in blood pressure, which was shown to be due to an increase in nitric oxide synthase type 2 (NOS2; Refs. 72, 91, 117), but this cannot be the entire explanation as RVR increases. Elevated RVR has been related to increases in superoxide production (127), and it may be due to TNF-α acting differently on renal vessels than those of the general circulation or on nephron segments that alter RVR such as the macula densa or connecting tubule. Increased RVR and reduced RBF and GFR were observed in both WT and TNFR2 KO mice but absent in TNFR1 KO, suggesting that the response was due to activation of TNFR1. Activation of TNFR2 (TNF-α treatment in TNFR1 KO mice) dilated blood vessels. Thus the effect of TNF-α on renal hemodynamics in healthy animals is mediated primarily by TNFR1 (20).

Renin-Angiotensin System

TNF-α decreases renin promoter activity and expression in primary cultures of juxtaglomerular (JG) cells and in As4.1 cells (a cell line that constitutively releases renin). In As4.1 cells, TNF-α (0.1 to 100 ng/ml) reduces renin release after 30 h of treatment. Moreover, TNF-α KO mice show a threefold increase in renal renin mRNA content but not changes in plasma renin activity. These data suggest that TNF-α negatively regulates renin expression via a reduction in mRNA levels due to declining transcription (144).

Todorov et al. (144) showed that TNF-α actions on renin expression were dependent on NF-κB binding to a cAMP-responsive element (CRE) located on the renin promoter. Binding of the proteins NF-κB-p50, p-65, p-52, and c-Rel to CRE lowered transcription. The transcriptional coactivator CBP, the protein that binds the transcription factor CRE binding protein (CREB), interacts with NF-κB and CREB/ATF transcription factors to initiate transcription; however, silencing CBP did not affect TNF-induced decreases in renin mRNA or promoter activity. Therefore, the authors concluded the effect most likely is not due to NF-κB competing with CREB/ATF for CBP but rather that NF-κB represses transcription after binding to CRE. This conclusion is supported by the ability of c-Rel to act as a transcriptional repressor (92). Although TNF-α decreases renin content, it does not reduce renin release by primary cultures of JG cells, and plasma renin activity is not significantly increased in TNF-α KO mice. Thus the acute effects of TNF-α on blood pressure are not likely due to changes in plasma renin activity (144).

Similar to its effect on renin levels, TNF-α was shown to reduce angiotensinogen levels in human kidney 2 (HK-2) cells, a renal proximal tubular cell line (123). Since intrarenal angiotensinogen levels correlate with blood pressure and are independent of plasma levels (45), in theory TNF-α could lower blood pressure by reducing angiotensinogen expression. However, to the best of our knowledge neither intrarenal nor intratubular levels of angiotensinogen have been measured in TNF-α KO mice nor has the receptor involved been identified.

Na, Water, Urea, and Glucose Transport

In spite of reductions in GFR and RBF in models of sepsis and during acute TNF-α infusion, urinary Na excretion increases. This indicates that TNF-α directly affects Na absorption along the nephron transport pathway independently of changes in renal hemodynamics. The effects of TNF-α have been studied in proximal tubular cells, thick ascending limbs, distal tubular cells, and collecting ducts.

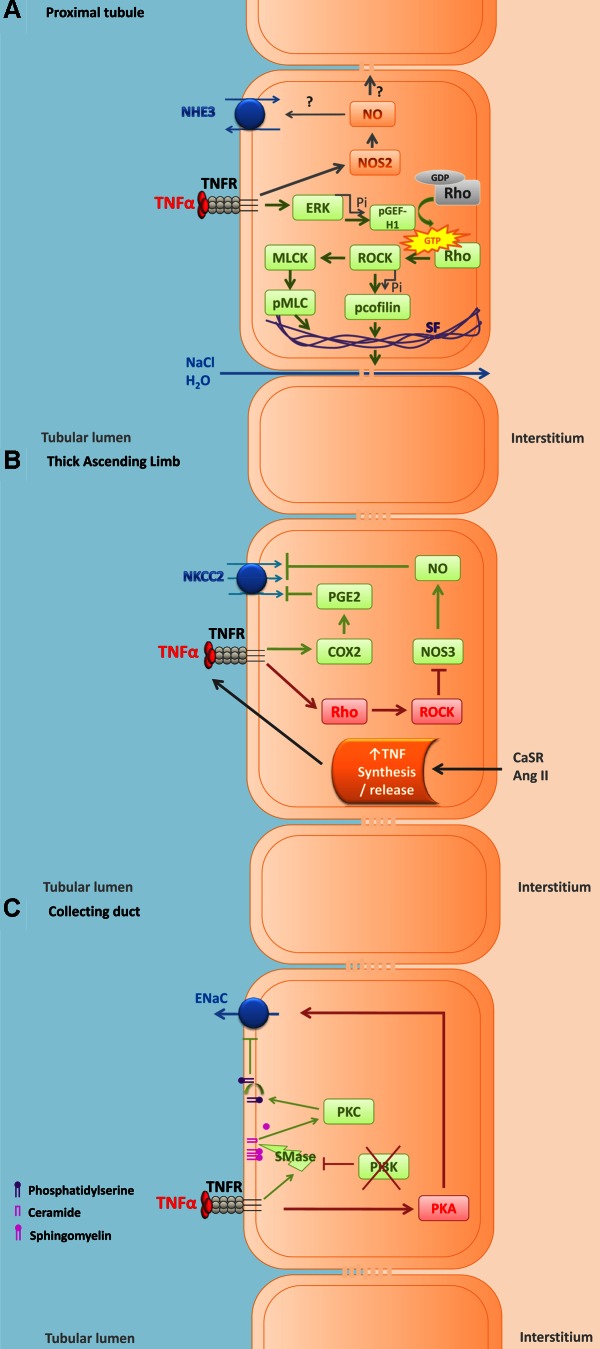

In LLCPk1 cells, a model of proximal tubule cells, TNF-α increases paracellular permeability, thereby activating extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK), which results in phosphorylation of the guanidine exchange factor GEF-H1. Phosphorylated GEF-H1 enhances RhoA GTPase, which binds and activates Rho kinase and increases myosin light chain phosphorylation, due in part to Rho kinase-induced inhibition of myosin light chain phosphatase and in part to direct activation of myosin light chain kinase. The increase in paracellular permeability is preceded by increased cofilin phosphorylation and formation of actin stress fibers (69, 70). Whether the increase in paracellular permeability increases or decreases net Na and fluid absorption is unclear from these reports, as they were not measured directly and arguments can be made either way. However, given that TNF-α reduces expression of renal Na-K-ATPase (126), which ultimately drives all Na absorption in the proximal nephron, it is likely that the combined actions of TNF-α on proximal nephron transport are inhibitory (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Cartoon showing the effects of TNF-α on ion transport in vitro in epithelial cells of the kidney. Effects of TNF-α in proximal tubular cells (A), in thick ascending limb cells (B), and in collecting duct cells (C). Red boxes and arrows represent pathways activated by TNF-α that are likely to increase Na reabsorption. Green boxes and arrows represent pathways activated by TNF-α that are likely to inhibit Na reabsorption. TNFR, TNF-α receptor; NHE3, Na/H exchanger type 3; NOS2, nitric oxide synthase type 2; ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinases; Pi, phosphate; pGEF-H1, phosphorylated guanine nucleotide exchange factor-H1; ROCK, Rho-dependent kinase; MLCK, myosin light chain kinase; pMLC, phosphorylated myosin light chain; SF, actin stress fibers; NKCC2, Na-K-2Cl cotransporter; COX2, cyclooxygenase type 2; PGE2, prostaglandin type 2; CaSR, calcium-sensitive receptor; ANG II, angiotensin II; ENaC, epithelial Na channel; PKA, cAMP-dependent protein kinase; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase; SMase, sphingomyelinase; PKC, protein kinase C.

TNF-α also enhances NO formation in proximal tubular cells due to increased inducible NO synthase (iNOS or NOS2; Refs. 68, 91). Although one report indicated that NO stimulated proximal tubule transport (157), most have shown that it inhibits Na and fluid absorption in this segment (31, 118). Thus NO-induced inhibition of proximal reabsorption could account for at least part of the increase in urinary Na excretion seen when TNF-α is infused. Whether the TNF-α-induced increase in paracellular permeability in proximal tubules depends on NO remains unclear.

In the thick ascending limb, ANG II and CaSR increase TNF-α release (3, 35, 156). In this nephron segment, both endogenous and exogenous TNF-α reduce NaCl transport via activation of cyclooxygenase (COX2)-induced increases in prostaglandin E (PGE) and inhibition of the Na-K-2Cl cotransporter (NKCC2; Refs. 2, 3, 12, 34). Increased TNF-α suppresses Rb uptake, a measure of thick ascending limb ion transport. In addition, activation of CaSR, which increases TNF-α release, has also been shown to increase COX2 expression and reduce ouabain-sensitive oxygen consumption in the thick ascending limb (2, 155), which may explain how CaSR activation leads to natriuresis.

About 80% of transcellular Na reabsorption in the thick ascending limb occurs through NKCC2. There are three isoforms of this transporter: A, B, and F. A is found throughout the thick ascending limb, B mainly in the cortex, and F primarily in the medulla. The level of expression in the kidney is 10B:20A:70F, and the order of ion affinity is NKCC2B > NKCC2A > NKCC2F (21). In TNF-α KO mice, expression of the A isoform was upregulated and this was reversed by infusion of TNF-α (0.01 mg·kg−1·day−1), whereas the other isoforms did not change; in addition, bumetanide-sensitive O2 consumption (an indicator of NKCC2 activity) was increased in TNF-α KO mice and was also restored by TNF-α infusion (12). In addition to reducing NKCC2, TNF-α reduces expression of thick ascending limb K channels (126), which would also be expected to reduce Na absorption. Finally, TNF-α reduces NOS3 expression and NO production in this nephron segment (116). NO produced in response to arginine (103, 110) endothelin-1 (109, 56) and clonidine (108) reduces NaCl reabsorption mainly by decreasing NKCC2 activity by the thick ascending limb. These data suggest that TNF-α affects Na transport regulation by the thick ascending limb by reducing basal Na reabsorption while blunting the ability of other natriuretic autacoids and hormones to further decrease transport. Given that thick ascending limbs absorb 30% of the filtered Na load, it is likely that direct actions of TNF-α in this segment contribute to elevated Na excretion (Fig. 2B).

In Madin-Darby canine kidney cells, a canine model of distal tubular cells, TNF-α increases paracellular permeability by activating RhoA GTPase, Rho kinase, and myosin light chain kinase, similar to LLCPk1 cells (69, 70). The net effect of this activity on transport is unknown.

In mpkCCDcL4 cells, a murine collecting duct cell line, 10 ng/ml TNF-α increased protein kinase A (PKA) activity independently of cAMP. LPS and TNF-α both increased transepithelial Na transport, measured as an increase in amiloride-sensitive short-circuit current, and this effect depended on PKA activation (154). In contrast, in Xenopus distal nephron cells (A6), 100 ng/ml TNF-α inhibited endothelial Na channel (ENaC) activity by reducing the channel open probability; however, this effect was only seen when phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) was inhibited. TNF-α inhibited ENaC via a mechanism that involved activation of sphingomyelinase and increased ceramide and activation of PKC, which in turn induced externalization of phosphatidylserine. The presence of phosphatidylserine in the cytosolic leaflet of the apical membrane is sufficient to maintain ENaC activity; thus disappearance of this phospholipid from the inner leaflet was likely the cause of reduced ENaC activity (11). The role of PI3K in preventing this effect was attributed to its ability to inhibit sphingomyelinase activity (18). These disparate findings could be explained by differences in the concentration of TNF-α tested, the experimental conditions, or the origin of the respective cells. For example, the A6 cells were grown with 1 μg aldosterone whereas the mpkCCD cells were not, and aldosterone activates PI3K (55). Whether or not other pertinent hormones are also present in the collecting duct and ultimately determine whether TNF-α increases or decreases ENaC activity could be the key to understanding its opposing effects on tubular transport and blood pressure. When infused in vivo, TNF-α reduces expression of all three subunits of ENaC (126); thus its actions on the cortical collecting duct likely also contribute to the natriuresis caused by systemic infusion (Fig. 2C). Finally, TNF-α increases nitrate/nitrite formation in inner medullary collecting ducts, suggesting elevated NO production that was supported by increased iNOS (68, 91) and NO has been reported to inhibit Na reabsorption by this segment (132).

TNF-α KO mice showed increased ambient urinary osmolality compared with WT, but water deprivation for 24 h increased urine osmolality to the same extent in both strains (12). LPS, which potently induces TNF-α release, decreases arginine-vasopressin type 2 receptor levels and aquaporin 2 expression in the renal inner medulla (49). In support of this, in a model of sepsis plasma arginine vasopressin did not change but V2 receptor and aquaporin 2 expression were decreased, whereas a siRNA against the TNFR p50 subunit attenuated the decrease in these proteins (58). Thus TNF-α may reduce vasopressin-dependent water retention due to both inhibition of water transport and reductions in the osmotic gradient developed by the thick ascending limb, which drives water absorption.

Maintenance of urinary osmolality depends not only on water and Na but also in large measure on urea. Blous infusion of TNF-α at a dose of 1 mg/kg decreased fractional urea excretion, inner medulla urea concentration and osmolality, tubular urea reabsorption, and urinary urea, whereas it increased plasma osmolality and urea. Such findings were attributed to reduced urea transporters UTA1, UTA2, UT-A3, UT-A4, and UT-B (124).

In addition to affecting Na and fluid absorption, TNF-α may diminish glucose absorption in the proximal nephron. Injection of TNF-α (1 mg/kg, bolus) decreases expression of sodium glucose transporters SGLT2 and SGLT3 and Na-K-ATPase within 12 h; however, it also increases Glut1 and SGLT1 in the kidney. The increase in Glut1 and SGLT1 may occur as a compensatory response to the reduced intracellular glucose levels resulting from 1) decreased glucose entry due to reductions in SGLT2 and 3, and 2) the lower Na gradient due to reduced Na-K-ATPase (125).

Renal Injury

Even though inhibition of transport could be interpreted as protecting the kidney from injury, the majority of the literature indicates that TNF-α induces renal damage. In part, this is undoubtedly due to diminished renal perfusion such as seen in sepsis (84, 127). It is also due in part to recruitment of immune cells into the kidney, releasing cytokines that cause inflammation and cell death (169). Finally, it is also likely due to direct actions of TNF-α on renal cells (65, 102).

TNFR1 contains a death domain, and thus the proapoptotic actions of TNF-α have been mainly attributed to this receptor (138, 64). TNFR1 interacts with the adaptor protein TNF receptor-associated death domain (TRADD) through TNFR1-DD (59), leading to recruitment of TNF receptor-associated factor 2 (TRAF2; Ref. 133). TRAF2 then interacts with the E3 ubiquitin ligases “cellular inhibitor of apoptosis” (c-IAP) 1 and 2 to form the membrane-bound complex I (93). c-IAP polyubiquitinates chains of RIP1, which is essential for recruitment of transforming growth factor-activated kinase 1 (TAK1) and activation of inhibitor of kappa B (IκB) kinase (IκK; Ref. 29). IκK phosphorylates IκB, which is then degraded via the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, allowing NF-κB to translocate to the nucleus where it initiates gene transcription targeting anti-apoptotic genes like c-FLIP, c-IAP-1 and 2, and TRAF1 and 2. Additionally, association of RIP1 and TRAF-2 with TNFR1 can lead to activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 1 (MEKKK-1) and c-Jun NH2-terminal kinases (JNK), which phosphorylate and activate c-Jun, a member of the transcription factor complex activator protein 1. Prolonged JNK activation mediates proteasomal degradation of c-FLIP and activation of caspase-8, leading to apoptosis (23, 135). TNF-α also activates apoptosis signaling kinase-1 (ASK1) via TNFR1 by inducing ASK1-interacting protein-1, which promotes ASK1 dissociation from the adaptor protein 14–3-3, phosphorylation at the stimulatory site threonine 845 (ASK1pThr845), and dephosphorylation of ASK1 at the inhibitory site serine 967 (86, 143, 166, 167).

In the normal kidney, strong staining for phospho-serine 967 ASK1 (ASK1pser967, the inhibitory site) colocalized with TNFR1 in glomerular and endothelial cells from peritubular capillaries, whereas coexpression of TNFR1 and ASK1pThr845 (the stimulatory site) was not found. In contrast, in renal allografts with acute cellular rejection, active ASK1pThr845 was strong in endothelial cells from glomerular and peritubular capillaries and in some tubular epithelial cells, whereas ASK1pSer967 was not detected. Similarly, in renal allografts with acute tubular necrosis, ASK1pSer967 was diminished but some tubular epithelial cells expressed a strong signal for ASK1pThre845. This pattern of expression was also found in normal kidney tissue treated with a TNFR1-specific activator; however, when a TNFR2-specific activator was used, both TNFR1 and ASK1pSer967 were elevated (9).

In contrast to TNFR1, activation of TNFR2 is associated with both apoptosis and cell survival. TNFR2 interacts with TRAF1 and 2, leading to RIP/c-IAP-induced activation of NF-κB (78, 120). Therefore, TNFR2 has been mainly associated with cell proliferation and survival (137). However, studies have shown a proapoptotic or cytotoxic function of TNFR2 activation (54, 67), and various models including TNFR2-mediated activation of TNFR1 (107), cytosolic depletion of c-IAP (39), and TNFR2-induced downregulation of NF-κB (46) have been proposed. A proapoptotic function for TNFR2 has been posited based on the fact that both TNFR2 and the complement molecule C3 were upregulated in glomerulonephritic kidneys and this was significantly reduced in TNFR2 KO mice, suggesting that TNFR2 can activate complement (153). TNFR2 also activates endothelial/epithelial tyrosine kinase (Etk), which has been linked to regulation of epithelial cell junctions (52), whereas in endothelial cells it is involved in TNF-induced angiogenic events (104) and mediates activation of PI3K and Akt (168). TNFR2-induced activation of Etk is TRAF2 independent. Binding of TNF-α to TNFR2 induces Etk unfolding, phosphorylation, and activation (104). In normal kidneys, TNFR2 was confined to cells in the glomeruli and interstitium, with a strong signal for Etk in glomerular endothelial cells. In renal allografts with acute cellular rejection or acute tubular necrosis, a strong signal for TNFR2 and Etkp was seen in most tubular epithelial cells. Similar observations were made when kidney tissue cultures were treated with a TNFR2-specific activator. Incubating kidney tissue with this activator also increased proliferation of tubular epithelial cells expressing Etkp, and this effect was more pronounced than when a TNFR1-specific activator was used (9).

Finally, circulating levels of TNFR play an important role in determining the severity of certain conditions, and therefore, TNFR levels should be reported. In this regard, both Gohda et al. (42) and Niewczas et al. (100) reported a strong positive correlation between circulating TNFR1 and TNFR2 with progression to chronic kidney disease in type 1 diabetes and end-stage renal disease in type 2 diabetes. This correlation was independent of other markers, including circulating TNF-α, blood pressure, albuminuria, and GFR. These authors reported that plasma concentrations of TNFR1 and 2 were clinical predictors of end-stage renal disease and chronic kidney disease; however, they did not assess whether elevated circulating TNFRs were the cause or the consequence of a dire outcome.

Concluding Remarks

The discrepancy between blood pressure-lowering effects and prohypertensive actions of TNF-α is still a matter for debate but is likely the result of many variables. For example, the TNF-α levels in plasma, the type of immune response (innate vs. adaptive), and the extent of the response (moderate vs. exaggerated) can determine whether blood pressure is increased or a shock response takes place. In general, plasma TNF-α levels in endotoxemic shock increase rapidly by 10-fold or more, whereas in hypertension or heart failure TNF-α levels are increased 1- to 2-fold. Similarly, animal models mimicking sepsis are infused with a bolus of 0.01 to 1 mg/kg TNF-α, whereas the doses used to induce hypertension in pregnant rats or TNF-α KO mice treated with ANG II are 0.5 μg/kg or lower and are maintained for days. This may mean that at high doses TNF-α has nonspecific effects or activates signaling cascades leading to hypotension that surpasses its hypertensive actions. Alternatively, the nonreceptor-mediated actions of TNF-α, which are due to the presence of a lectin-like domain in human TNF-α, could be activated at high doses. This domain, although far removed from the receptor binding site, nevertheless recognizes oligosaccharides and mediates some TNF-α actions like trypanolytic activity (88). In addition, sudden and exaggerated activation of the innate immune response, with massive increases in macrophage and neutrophil infiltration, seems to result in a shock state and leads to hypotension. In contrast, more moderate and chronic activation of the adaptive immune response with participation of macrophages and lymphocytes contributes to slowly developing renal damage, increased NaCl retention, and hypertension.

One of the problems in dissecting the prohypertensive vs. prohypotensive actions of TNF-α is that the approaches utilized to block TNF-α differ in their side effects. The use of chimeric proteins as opposed to antibodies to block the actions of TNF or the use of a KO mouse model could explain why TNF-α seems to be protective in some studies but detrimental in others. Depending on which portion of the TNFR is conserved during anti-TNF treatment, it may or may not induce complement deposition and a cytotoxic reaction. In addition, while KO models provide a promising tool to study the role of certain genes in disease, they may also generate misleading results. Impaired development of germinal centers and follicular dendritic cell networks in secondary lymphoid organs has been observed in TNF-α and TNFR1 KO mice (75, 82, 106). Moreover, overexpression of TNFR1 in TNFR2 KO mice and elevated TNFR2 in TNFR1 KO has been shown: thus a seemingly protective role of TNFR1 that is absent in TNFR1 KO might be simply due to overexpression of TNFR2. Similarly, a detrimental response in TNF-α or TNFR1 KO could be attributable to their inability to handle infections, not the absence of the direct effects of TNF on ion transport or blood pressure. Finally, membrane-bound TNF effects, which have been very poorly explored, could also confuse results.

Overall, blockade of TNF-α during hypertension seems to provide a beneficial outcome, while handling the development of autoimmune diseases in patients treated with TNF-neutralizing agents is not a trivial undertaking (75). On the other hand, the battle between lowering TNF-α levels in septic shock and stimulating the immune system to fight the infection still represents a clinical challenge. Therefore, the discovery of specific mediators of TNF-induced increases and decreases in blood pressure would represent a great advance in the generation of effective alternate treatments for hypertension and shock-induced hypotension.

GRANTS

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (HL-028982, HL-070985, and HL-090550; to J. L. Garvin) and from the American Heart Association (11PRE7510005; to V.D. Ramseyer).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: V.R. prepared figures; V.R. drafted manuscript; V.R. and J.L.G. edited and revised manuscript; V.R. and J.L.G. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. Abdullah HI, Pedraza PL, Hao S, Rodland KD, McGiff JC, Ferreri NR. NFAT regulates calcium-sensing receptor-mediated TNF production. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 290: F1110–F1117, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Abdullah HI, Pedraza PL, McGiff JC, Ferreri NR. Calcium-sensing receptor signaling pathways in medullary thick ascending limb cells mediate COX-2-derived PGE2 production: functional significance. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 295: F1082–F1089, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Abdullah HI, Pedraza PL, McGiff JC, Ferreri NR. CaR activation increases TNF production by mTAL cells via a Gi-dependent mechanism. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 294: F345–F354, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Abraham E. Why immunomodulatory therapies have not worked in sepsis. Intensive Care Med 25: 556–566, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Adembri C, Sgambati E, Vitali L, Selmi V, Margheri M, Tani A, Bonaccini L, Nosi D, Caldini AL, Formigli L, De Gaudio AR. Sepsis induces albuminuria and alterations in the glomerular filtration barrier: a morphofunctional study in the rat. Crit Care 15: R277, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Affres H, Perez J, Hagege J, Fouqueray B, Kornprobst M, Ardaillou R, Baud L. Desferrioxamine regulates tumor necrosis factor release in mesangial cells. Kidney Int 39: 822–830, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Aki K, Shimizu A, Masuda Y, Kuwahara N, Arai T, Ishikawa A, Fujita E, Mii A, Natori Y, Fukunaga Y, Fukuda Y. ANG II receptor blockade enhances anti-inflammatory macrophages in anti-glomerular basement membrane glomerulonephritis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 298: F870–F882, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Al-Lamki RS, Wang J, Skepper JN, Thiru S, Pober JS, Bradley JR. Expression of tumor necrosis factor receptors in normal kidney and rejecting renal transplants. Lab Invest 81: 1503–1515, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Al-Lamki RS, Wang J, Vandenabeele P, Bradley JA, Thiru S, Luo D, Min W, Pober JS, Bradley JR. TNFR1- and TNFR2-mediated signaling pathways in human kidney are cell type-specific and differentially contribute to renal injury. FASEB J 19: 1637–1645, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Alexander BT, Cockrell KL, Massey MB, Bennett WA, Granger JP. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced hypertension in pregnant rats results in decreased renal neuronal nitric oxide synthase expression. Am J Hypertens 15: 170–175, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bao HF, Zhang ZR, Liang YY, Ma JJ, Eaton DC, Ma HP. Ceramide mediates inhibition of the renal epithelial sodium channel by tumor necrosis factor-alpha through protein kinase C. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293: F1178–F1186, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Battula S, Hao S, Pedraza PL, Stier CT, Ferreri NR. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha is an endogenous inhibitor of Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter (NKCC2) isoform A in the thick ascending limb. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 301: F94–F100, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Baud L, Fouqueray B, Philippe C, Amrani A. Tumor necrosis factor alpha and mesangial cells. Kidney Int 41: 600–603, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Baud L, Oudinet JP, Bens M, Noe L, Peraldi MN, Rondeau E, Etienne J, Ardaillou R. Production of tumor necrosis factor by rat mesangial cells in response to bacterial lipopolysaccharide. Kidney Int 35: 1111–1118, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Beutler B, Greenwald D, Hulmes JD, Chang M, Pan YC, Mathison J, Ulevitch R, Cerami A. Identity of tumour necrosis factor and the macrophage-secreted factor cachectin. Nature 316: 552–554, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Black RA, Rauch CT, Kozlosky CJ, Peschon JJ, Slack JL, Wolfson MF, Castner BJ, Stocking KL, Reddy P, Srinivasan S, Nelson N, Boiani N, Schooley KA, Gerhart M, Davis R, Fitzner JN, Johnson RS, Paxton RJ, March CJ, Cerretti DP. A metalloproteinase disintegrin that releases tumour-necrosis factor-alpha from cells. Nature 385: 729–733, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bucher M, Kees F, Taeger K, Kurtz A. Cytokines down-regulate alpha1-adrenergic receptor expression during endotoxemia. Crit Care Med 31: 566–571, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Burow ME, Weldon CB, Collins-Burow BM, Ramsey N, McKee A, Klippel A, McLachlan JA, Clejan S, Beckman BS. Cross-talk between phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and sphingomyelinase pathways as a mechanism for cell survival/death decisions. J Biol Chem 275: 9628–9635, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Carswell EA, Old LJ, Kassel RL, Green S, Fiore N, Williamson B. An endotoxin-induced serum factor that causes necrosis of tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 72: 3666–3670, 1975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Castillo A, Islam MT, Prieto MC, Majid DS. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha receptor type 1, not type 2, mediates its acute responses in the kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 302: F1650–F1657, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Castrop H, Schnermann J. Isoforms of renal Na-K-2Cl cotransporter NKCC2: expression and functional significance. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 295: F859–F866, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chan FK, Chun HJ, Zheng L, Siegel RM, Bui KL, Lenardo MJ. A domain in TNF receptors that mediates ligand-independent receptor assembly and signaling. Science 288: 2351–2354, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chang L, Kamata H, Solinas G, Luo JL, Maeda S, Venuprasad K, Liu YC, Karin M. The E3 ubiquitin ligase itch couples JNK activation to TNFalpha-induced cell death by inducing c-FLIP(L) turnover. Cell 124: 601–613, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chen CC, Pedraza PL, Hao S, Stier CT, Ferreri NR. TNFR1-deficient mice display altered blood pressure and renal responses to ANG II infusion. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 299: F1141–F1150, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Conrad KP, Miles TM, Benyo DF. Circulating levels of immunoreactive cytokines in women with preeclampsia. Am J Reprod Immunol 40: 102–111, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cunningham PN, Dyanov HM, Park P, Wang J, Newell KA, Quigg RJ. Acute renal failure in endotoxemia is caused by TNF acting directly on TNF receptor-1 in kidney. J Immunol 168: 5817–5823, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. De PG, Castellano G, Del PA, Sozzani S, Fiore N, Loverre A, Parmentier M, Gesualdo L, Grandaliano G, Schena FP. The possible role of ChemR23/Chemerin axis in the recruitment of dendritic cells in lupus nephritis. Kidney Int 79: 1228–1235, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Declercq W, Denecker G, Fiers W, Vandenabeele P. Cooperation of both TNF receptors in inducing apoptosis: involvement of the TNF receptor-associated factor binding domain of the TNF receptor 75. J Immunol 161: 390–399, 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ea CK, Deng L, Xia ZP, Pineda G, Chen ZJ. Activation of IKK by TNFalpha requires site-specific ubiquitination of RIP1 and polyubiquitin binding by NEMO. Mol Cell 22: 245–257, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ebenezer PJ, Mariappan N, Elks CM, Haque M, Francis J. Diet-induced renal changes in Zucker rats are ameliorated by the superoxide dismutase mimetic TEMPOL. Obesity (Silver Spring) 17: 1994–2002, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Eitle E, Hiranyachattada S, Wang H, Harris PJ. Inhibition of proximal tubular fluid absorption by nitric oxide and atrial natriuretic peptide in rat kidney. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 274: C1075–C1080, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Elmarakby AA, Quigley JE, Imig JD, Pollock JS, Pollock DM. TNF-alpha inhibition reduces renal injury in DOCA-salt hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 294: R76–R83, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Elmarakby AA, Quigley JE, Pollock DM, Imig JD. Tumor necrosis factor alpha blockade increases renal Cyp2c23 expression and slows the progression of renal damage in salt-sensitive hypertension. Hypertension 47: 557–562, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Escalante BA, Ferreri NR, Dunn CE, McGiff JC. Cytokines affect ion transport in primary cultured thick ascending limb of Henle's loop cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 266: C1568–C1576, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ferreri NR, Escalante BA, Zhao Y, An SJ, McGiff JC. Angiotensin II induces TNF production by the thick ascending limb: functional implications. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 274: F148–F155, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ferreri NR, Zhao Y, Takizawa H, McGiff JC. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha-angiotensin interactions and regulation of blood pressure. J Hypertens 15: 1481–1484, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fong Y, Tracey KJ, Moldawer LL, Hesse DG, Manogue KB, Kenney JS, Lee AT, Kuo GC, Allison AC, Lowry SF. Antibodies to cachectin/tumor necrosis factor reduce interleukin 1 beta and interleukin 6 appearance during lethal bacteremia. J Exp Med 170: 1627–1633, 1989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fornoni A, Ijaz A, Tejada T, Lenz O. Role of inflammation in diabetic nephropathy. Curr Diabetes Rev 4: 10–17, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fotin-Mleczek M, Henkler F, Samel D, Reichwein M, Hausser A, Parmryd I, Scheurich P, Schmid JA, Wajant H. Apoptotic crosstalk of TNF receptors: TNF-R2-induces depletion of TRAF2 and IAP proteins and accelerates TNF-R1-dependent activation of caspase-8. J Cell Sci 115: 2757–2770, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Fouqueray B, Philippe C, Herbelin A, Perez J, Ardaillou R, Baud L. Cytokine formation within rat glomeruli during experimental endotoxemia. J Am Soc Nephrol 3: 1783–1791, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ. Immunomodulatory therapies for sepsis: unexpected effects with macrolides. Int J Antimicrob Agents 32, Suppl 1: S39–S43, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Gohda T, Niewczas MA, Ficociello LH, Walker WH, Skupien J, Rosetti F, Cullere X, Johnson AC, Crabtree G, Smiles AM, Mayadas TN, Warram JH, Krolewski AS. Circulating TNF receptors 1 and 2 predict stage 3 CKD in type 1 diabetes. J Am Soc Nephrol 23: 516–524, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gomez-Guerrero C, Lopez-Armada MJ, Gonzalez E, Egido J. Soluble IgA and IgG aggregates are catabolized by cultured rat mesangial cells and induce production of TNF-alpha and IL-6, and proliferation. J Immunol 153: 5247–5255, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gomez-Sanchez EP, Zhou M, Gomez-Sanchez CE. Mineralocorticoids, salt and high blood pressure. Steroids 61: 184–188, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gonzalez-Villalobos RA, Seth DM, Satou R, Horton H, Ohashi N, Miyata K, Katsurada A, Tran DV, Kobori H, Navar LG. Intrarenal angiotensin II and angiotensinogen augmentation in chronic angiotensin II-infused mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 295: F772–F779, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Grech AP, Gardam S, Chan T, Quinn R, Gonzales R, Basten A, Brink R. Tumor necrosis factor receptor 2 (TNFR2) signaling is negatively regulated by a novel, carboxyl-terminal TNFR-associated factor 2 (TRAF2)-binding site. J Biol Chem 280: 31572–31581, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Grell M, Douni E, Wajant H, Lohden M, Clauss M, Maxeiner B, Georgopoulos S, Lesslauer W, Kollias G, Pfizenmaier K, Scheurich P. The transmembrane form of tumor necrosis factor is the prime activating ligand of the 80 kDa tumor necrosis factor receptor. Cell 83: 793–802, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Grell M, Wajant H, Zimmermann G, Scheurich P. The type 1 receptor (CD120a) is the high-affinity receptor for soluble tumor necrosis factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 570–575, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Grinevich V, Knepper MA, Verbalis J, Reyes I, Aguilera G. Acute endotoxemia in rats induces down-regulation of V2 vasopressin receptors and aquaporin-2 content in the kidney medulla. Kidney Int 65: 54–62, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Guo G, Morrissey J, McCracken R, Tolley T, Klahr S. Role of TNFR1 and TNFR2 receptors in tubulointerstitial fibrosis of obstructive nephropathy. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 277: F766–F772, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Guzik TJ, Hoch NE, Brown KA, McCann LA, Rahman A, Dikalov S, Goronzy J, Weyand C, Harrison DG. Role of the T cell in the genesis of angiotensin II induced hypertension and vascular dysfunction. J Exp Med 204: 2449–2460, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hamm-Alvarez SF, Chang A, Wang Y, Jerdeva G, Lin HH, Kim KJ, Ann DK. Etk/Bmx activation modulates barrier function in epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 280: C1657–C1668, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hao S, Zhao H, Darzynkiewicz Z, Battula S, Ferreri NR. Expression and function of NFAT5 in medullary thick ascending limb (mTAL) cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 296: F1494–F1503, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Heller RA, Song K, Fan N, Chang DJ. The p70 tumor necrosis factor receptor mediates cytotoxicity. Cell 70: 47–56, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Helms MN, Liu L, Liang YY, Al-Khalili O, Vandewalle A, Saxena S, Eaton DC, Ma HP. Phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate mediates aldosterone stimulation of epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) and interacts with gamma-ENaC. J Biol Chem 280: 40885–40891, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Herrera M, Hong NJ, Ortiz PA, Garvin JL. Endothelin-1 inhibits thick ascending limb transport via Akt-stimulated nitric oxide production. J Biol Chem 284: 1454–1460, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Herrera M, Silva GB, Garvin JL. Angiotensin II stimulates thick ascending limb superoxide production via protein kinase C(alpha)-dependent NADPH oxidase activation. J Biol Chem 285: 21323–21328, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hocherl K, Schmidt C, Kurt B, Bucher M. Inhibition of NF-κB ameliorates sepsis-induced downregulation of aquaporin-2/V2 receptor expression and acute renal failure in vivo. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 298: F196–F204, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Hsu H, Xiong J, Goeddel DV. The TNF receptor 1-associated protein TRADD signals cell death and NF-kappa B activation. Cell 81: 495–504, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Ichinose Y, Tsao JY, Fidler IJ. Destruction of tumor cells by monokines released from activated human blood monocytes: evidence for parallel and additive effects of IL-1 and TNF. Cancer Immunol Immunother 27: 7–12, 1988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Imaizumi T, Itaya H, Fujita K, Kudoh D, Kudoh S, Mori K, Fujimoto K, Matsumiya T, Yoshida H, Satoh K. Expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in cultured human endothelial cells stimulated with lipopolysaccharide or interleukin-1alpha. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 20: 410–415, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Irani RA, Zhang Y, Zhou CC, Blackwell SC, Hicks MJ, Ramin SM, Kellems RE, Xia Y. Autoantibody-mediated angiotensin receptor activation contributes to preeclampsia through tumor necrosis factor-alpha signaling. Hypertension 55: 1246–1253, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Ito H, Ohshima A, Tsuzuki M, Ohto N, Takao K, Hijii C, Yanagawa M, Ogasawara M, Nishioka K. Association of serum tumour necrosis factor-alpha with serum low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol and blood pressure in apparently healthy Japanese women. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 28: 188–192, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Itoh N, Nagata S. A novel protein domain required for apoptosis. Mutational analysis of human Fas antigen. J Biol Chem 268: 10932–10937, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Izawa-Ishizawa Y, Ishizawa K, Sakurada T, Imanishi M, Miyamoto L, Fujii S, Taira H, Kihira Y, Ikeda Y, Hamano S, Tomita S, Tsuchiya K, Tamaki T. Angiotensin II receptor blocker improves tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced cytotoxicity via antioxidative effect in human glomerular endothelial cells. Pharmacology 90: 324–331, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Jevnikar AM, Brennan DC, Singer GG, Heng JE, Maslinski W, Wuthrich RP, Glimcher LH, Kelley VE. Stimulated kidney tubular epithelial cells express membrane associated and secreted TNF alpha. Kidney Int 40: 203–211, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Ji W, Li Y, Wan T, Wang J, Zhang H, Chen H, Min W. Both internalization and aip1 association are required for tumor necrosis factor receptor 2-mediated JNK signaling. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 32: 2271–2279, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Kabore AF, Denis M, Bergeron MG. Association of nitric oxide production by kidney proximal tubular cells in response to lipopolysaccharide and cytokines with cellular damage. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 41: 557–562, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Kakiashvili E, Dan Q, Vandermeer M, Zhang Y, Waheed F, Pham M, Szaszi K. The epidermal growth factor receptor mediates tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced activation of the ERK/GEF-H1/RhoA pathway in tubular epithelium. J Biol Chem 286: 9268–9279, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Kakiashvili E, Speight P, Waheed F, Seth R, Lodyga M, Tanimura S, Kohno M, Rotstein OD, Kapus A, Szaszi K. GEF-H1 mediates tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced Rho activation and myosin phosphorylation: role in the regulation of tubular paracellular permeability. J Biol Chem 284: 11454–11466, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Karkar AM, Koshino Y, Cashman SJ, Dash AC, Bonnefoy J, Meager A, Rees AJ. Passive immunization against tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) and IL-1 beta protects from LPS enhancing glomerular injury in nephrotoxic nephritis in rats. Clin Exp Immunol 90: 312–318, 1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Kilbourn RG, Gross SS, Jubran A, Adams J, Griffith OW, Levi R, Lodato RF. NG-methyl-L-arginine inhibits tumor necrosis factor-induced hypotension: implications for the involvement of nitric oxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 87: 3629–3632, 1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Kim YK, Choi TR, Kwon CH, Kim JH, Woo JS, Jung JS. Beneficial effect of pentoxifylline on cisplatin-induced acute renal failure in rabbits. Ren Fail 25: 909–922, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Kita T, Tanaka N, Nagano T. The immunocytochemical localization of tumour necrosis factor and leukotriene in the rat kidney after treatment with lipopolysaccharide. Int J Exp Pathol 74: 471–479, 1993 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Kollias G, Kontoyiannis D. Role of TNF/TNFR in autoimmunity: specific TNF receptor blockade may be advantageous to anti-TNF treatments. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 13: 315–321, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Kriegler M, Perez C, DeFay K, Albert I, Lu SD. A novel form of TNF/cachectin is a cell surface cytotoxic transmembrane protein: ramifications for the complex physiology of TNF. Cell 53: 45–53, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Kumar A, Paladugu B, Mensing J, Kumar A, Parrillo JE. Nitric oxide-dependent and -independent mechanisms are involved in TNF-α-induced depression of cardiac myocyte contractility. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 292: R1900–R1906, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Laegreid A, Medvedev A, Nonstad U, Bombara MP, Ranges G, Sundan A, Espevik T. Tumor necrosis factor receptor p75 mediates cell-specific activation of nuclear factor kappa B and induction of human cytomegalovirus enhancer. J Biol Chem 269: 7785–7791, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. LaMarca B, Speed J, Fournier L, Babcock SA, Berry H, Cockrell K, Granger JP. Hypertension in response to chronic reductions in uterine perfusion in pregnant rats: effect of tumor necrosis factor-alpha blockade. Hypertension 52: 1161–1167, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. LaMarca BB, Bennett WA, Alexander BT, Cockrell K, Granger JP. Hypertension produced by reductions in uterine perfusion in the pregnant rat: role of tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Hypertension 46: 1022–1025, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. LaMarca BB, Cockrell K, Sullivan E, Bennett W, Granger JP. Role of endothelin in mediating tumor necrosis factor-induced hypertension in pregnant rats. Hypertension 46: 82–86, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Le Hir M, Bluethmann H, Kosco-Vilbois MH, Müller M, di Padova F, Moore M, Ryffel B, Eugster HP. Differentiation of follicular dendritic cells and full antibody responses require tumor necrosis factor receptor-1 signaling. J Exp Med 183: 2367–2372, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Lee S, Kim W, Kang KP, Moon SO, Sung MJ, Kim DH, Kim HJ, Park SK. Agonist of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma, rosiglitazone, reduces renal injury and dysfunction in a murine sepsis model. Nephrol Dial Transplant 20: 1057–1065, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Legrand M, Bezemer R, Kandil A, Demirci C, Payen D, Ince C. The role of renal hypoperfusion in development of renal microcirculatory dysfunction in endotoxemic rats. Intensive Care Med 37: 1534–1542, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Leon CG, Tory R, Jia J, Sivak O, Wasan KM. Discovery and development of toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) antagonists: a new paradigm for treating sepsis and other diseases. Pharm Res 25: 1751–1761, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Liu Y, Yin G, Surapisitchat J, Berk BC, Min W. Laminar flow inhibits TNF-induced ASK1 activation by preventing dissociation of ASK1 from its inhibitor 14–3-3. J Clin Invest 107: 917–923, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Lucas R, Garcia I, Donati YR, Hribar M, Mandriota SJ, Giroud C, Buurman WA, Fransen L, Suter PM, Nunez G, Pepper MS, Grau GE. Both TNF receptors are required for direct TNF-mediated cytotoxicity in microvascular endothelial cells. Eur J Immunol 28: 3577–3586, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Lucas R, Magez S, De LR, Fransen L, Scheerlinck JP, Rampelberg M, Sablon E, De BP. Mapping the lectin-like activity of tumor necrosis factor. Science 263: 814–817, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Luettig B, Decker T, Lohmann-Matthes ML. Evidence for the existence of two forms of membrane tumor necrosis factor: an integral protein and a molecule attached to its receptor. J Immunol 143: 4034–4038, 1989 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Macica CM, Escalante BA, Conners MS, Ferreri NR. TNF production by the medullary thick ascending limb of Henle's loop. Kidney Int 46: 113–121, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Markewitz BA, Michael JR, Kohan DE. Cytokine-induced expression of a nitric oxide synthase in rat renal tubule cells. J Clin Invest 91: 2138–2143, 1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. McDonnell PC, Kumar S, Rabson AB, Gelinas C. Transcriptional activity of rel family proteins. Oncogene 7: 163–170, 1992 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Micheau O, Tschopp J. Induction of TNF receptor I-mediated apoptosis via two sequential signaling complexes. Cell 114: 181–190, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Misseri R, Meldrum DR, Dagher P, Hile K, Rink RC, Meldrum KK. Unilateral ureteral obstruction induces renal tubular cell production of tumor necrosis factor-alpha independent of inflammatory cell infiltration. J Urol 172: 1595–1599, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Miyakawa H, Woo SK, Dahl SC, Handler JS, Kwon HM. Tonicity-responsive enhancer binding protein, a rel-like protein that stimulates transcription in response to hypertonicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 2538–2542, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Muller DN, Shagdarsuren E, Park JK, Dechend R, Mervaala E, Hampich F, Fiebeler A, Ju X, Finckenberg P, Theuer J, Viedt C, Kreuzer J, Heidecke H, Haller H, Zenke M, Luft FC. Immunosuppressive treatment protects against angiotensin II-induced renal damage. Am J Pathol 161: 1679–1693, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Naikawadi RP, Cheng N, Vogel SM, Qian F, Wu D, Malik AB, Ye RD. A critical role for phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate-dependent Rac exchanger 1 in endothelial junction disruption and vascular hyperpermeability. Circ Res 111: 1517–1527, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Nakamura A, Johns EJ, Imaizumi A, Niimi R, Yanagawa Y, Kohsaka T. Role of angiotensin II-induced cAMP in mesangial TNF-alpha production. Cytokine 19: 47–51, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Neale TJ, Ruger BM, Macaulay H, Dunbar PR, Hasan Q, Bourke A, Murray-McIntosh RP, Kitching AR. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha is expressed by glomerular visceral epithelial cells in human membranous nephropathy. Am J Pathol 146: 1444–1454, 1995 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Niewczas MA, Gohda T, Skupien J, Smiles AM, Walker WH, Rosetti F, Cullere X, Eckfeldt JH, Doria A, Mayadas TN, Warram JH, Krolewski AS. Circulating TNF receptors 1 and 2 predict ESRD in type 2 diabetes. J Am Soc Nephrol 23: 507–515, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Noiri E, Kuwata S, Nosaka K, Tokunaga K, Juji T, Shibata Y, Kurokawa K. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha mRNA expression in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated rat kidney. Chronological analysis of localization. Am J Pathol 144: 1159–1166, 1994 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Ortiz A, Lorz C, Justo P, Catalan MP, Egido J. Contribution of apoptotic cell death to renal injury. J Cell Mol Med 5: 18–32, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Ortiz PA, Hong NJ, Wang D, Garvin JL. Gene transfer of eNOS to the thick ascending limb of eNOS-KO mice restores the effects of l-arginine on NaCl absorption. Hypertension 42: 674–679, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Pan S, An P, Zhang R, He X, Yin G, Min W. Etk/Bmx as a tumor necrosis factor receptor type 2-specific kinase: role in endothelial cell migration and angiogenesis. Mol Cell Biol 22: 7512–7523, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Parameswaran N, Patial S. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha signaling in macrophages. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr 20: 87–103, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Pfeffer K. Biological functions of tumor necrosis factor cytokines and their receptors. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 14: 185–191, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Pinckard JK, Sheehan KC, Schreiber RD. Ligand-induced formation of p55 and p75 tumor necrosis factor receptor heterocomplexes on intact cells. J Biol Chem 272: 10784–10789, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Plato CF, Garvin JL. α2-Adrenergic-mediated tubular NO production inhibits thick ascending limb chloride absorption. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 281: F679–F686, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Plato CF, Pollock DM, Garvin JL. Endothelin inhibits thick ascending limb chloride flux via ETB receptor-mediated NO release. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 279: F326–F333, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Plato CF, Shesely EG, Garvin JL. eNOS mediates l-arginine-induced inhibition of thick ascending limb chloride flux. Hypertension 35: 319–323, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Pocsik E, Duda E, Wallach D. Phosphorylation of the 26 kDa TNF precursor in monocytic cells and in transfected HeLa cells. J Inflamm 45: 152–160, 1995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Qiu P, Cui X, Barochia A, Li Y, Natanson C, Eichacker PQ. The evolving experience with therapeutic TNF inhibition in sepsis: considering the potential influence of risk of death. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 20: 1555–1564, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Ramesh G, Brian RW. Cisplatin increases TNF-alpha mRNA stability in kidney proximal tubule cells. Ren Fail 28: 583–592, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Ramesh G, Reeves WB. TNF-alpha mediates chemokine and cytokine expression and renal injury in cisplatin nephrotoxicity. J Clin Invest 110: 835–842, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Ramesh G, Reeves WB. Inflammatory cytokines in acute renal failure. Kidney Int Suppl S56–S61, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Ramseyer VD, Hong NJ, Garvin JL. Tumor necrosis factor alpha decreases nitric oxide synthase type 3 expression primarily via Rho/Rho kinase in the thick ascending limb. Hypertension 59: 1145–1150, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Rees DD, Monkhouse JE, Cambridge D, Moncada S. Nitric oxide and the haemodynamic profile of endotoxin shock in the conscious mouse. Br J Pharmacol 124: 540–546, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Roczniak A, Burns KD. Nitric oxide stimulates guanylate cyclase and regulates sodium transport in rabbit proximal tubule. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 270: F106–F115, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Rosa AC, Rattazzi L, Miglio G, Collino M, Fantozzi R. Angiotensin II induces tumor necrosis factor-alpha expression and release from cultured human podocytes. Inflamm Res 61: 311–317, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Rothe M, Wong SC, Henzel WJ, Goeddel DV. A novel family of putative signal transducers associated with the cytoplasmic domain of the 75 kDa tumor necrosis factor receptor. Cell 78: 681–692, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Ruiz-Ortega M, Ruperez M, Lorenzo O, Esteban V, Blanco J, Mezzano S, Egido J. Angiotensin II regulates the synthesis of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines in the kidney. Kidney Int Suppl S12–S22, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Saftlas AF, Olson DR, Franks AL, Atrash HK, Pokras R. Epidemiology of preeclampsia and eclampsia in the United States, 1979–1986. Am J Obstet Gynecol 163: 460–465, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Satou R, Miyata K, Katsurada A, Navar LG, Kobori H. Tumor necrosis factor-α suppresses angiotensinogen expression through formation of a p50/p50 homodimer in human renal proximal tubular cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 299: C750–C759, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Schmidt C, Hocherl K, Bucher M. Cytokine-mediated regulation of urea transporters during experimental endotoxemia. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 292: F1479–F1489, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Schmidt C, Hocherl K, Bucher M. Regulation of renal glucose transporters during severe inflammation. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 292: F804–F811, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Schmidt C, Hocherl K, Schweda F, Kurtz A, Bucher M. Regulation of renal sodium transporters during severe inflammation. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 1072–1083, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Shahid M, Francis J, Majid DS. Tumor necrosis factor-α induces renal vasoconstriction as well as natriuresis in mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 295: F1836–F1844, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Silva GB, Garvin JL. Angiotensin II-dependent hypertension increases Na transport-related oxygen consumption by the thick ascending limb. Hypertension 52: 1091–1098, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Singh P, Bahrami L, Castillo A, Majid DS. TNF-α type 2 receptor mediates renal inflammatory response to chronic angiotensin II administration with high salt intake in mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 304: F991–F999, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Sonkar GK, Singh RG. Evaluation of serum tumor necrosis factor alpha and its correlation with histology in chronic kidney disease, stable renal transplant and rejection cases. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl 20: 1000–1004, 2009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Sriramula S, Haque M, Majid DS, Francis J. Involvement of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in angiotensin II-mediated effects on salt appetite, hypertension, and cardiac hypertrophy. Hypertension 51: 1345–1351, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Stoos BA, Garcia NH, Garvin JL. Nitric oxide inhibits sodium reabsorption in the isolated perfused cortical collecting duct. J Am Soc Nephrol 6: 89–94, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Takeuchi M, Rothe M, Goeddel DV, Anatomy of TRAF2 Distinct domains for nuclear factor-kappaB activation and association with tumor necrosis factor signaling proteins. J Biol Chem 271: 19935–19942, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Tan X, He W, Liu Y. Combination therapy with paricalcitol and trandolapril reduces renal fibrosis in obstructive nephropathy. Kidney Int 76: 1248–1257, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Tang G, Minemoto Y, Dibling B, Purcell NH, Li Z, Karin M, Lin A. Inhibition of JNK activation through NF-kappaB target genes. Nature 414: 313–317, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Tang P, Hung MC, Klostergaard J. Human pro-tumor necrosis factor is a homotrimer. Biochemistry 35: 8216–8225, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Tartaglia LA, Goeddel DV, Reynolds C, Figari IS, Weber RF, Fendly BM, Palladino MA., Jr Stimulation of human T-cell proliferation by specific activation of the 75-kDa tumor necrosis factor receptor. J Immunol 151: 4637–4641, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Tartaglia LA, Weber RF, Figari IS, Reynolds C, Palladino MA, Jr, Goeddel DV. The two different receptors for tumor necrosis factor mediate distinct cellular responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 88: 9292–9296, 1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139. Therrien FJ, Agharazii M, Lebel M, Lariviere R. Neutralization of tumor necrosis factor-alpha reduces renal fibrosis and hypertension in rats with renal failure. Am J Nephrol 36: 151–161, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140. Tikkanen I, Uhlenius N, Tikkanen T, Miettinen A, Tornroth T, Fyhrquist F, Holthofer H. Increased renal expression of cytokines and growth factors induced by DOCA-NaCl treatment in Heymann nephritis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 10: 2192–2198, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141. Timoshanko JR, Sedgwick JD, Holdsworth SR, Tipping PG. Intrinsic renal cells are the major source of tumor necrosis factor contributing to renal injury in murine crescentic glomerulonephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 1785–1793, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142. Tipping PG, Leong TW, Holdsworth SR. Tumor necrosis factor production by glomerular macrophages in anti-glomerular basement membrane glomerulonephritis in rabbits. Lab Invest 65: 272–279, 1991 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143. Tobiume K, Saitoh M, Ichijo H. Activation of apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 by the stress-induced activating phosphorylation of pre-formed oligomer. J Cell Physiol 191: 95–104, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144. Todorov V, Muller M, Schweda F, Kurtz A. Tumor necrosis factor-α inhibits renin gene expression. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 283: R1046–R1051, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145. Tracey KJ, Beutler B, Lowry SF, Merryweather J, Wolpe S, Milsark IW, Hariri RJ, Fahey TJ, III, Zentella A, Albert JD. Shock and tissue injury induced by recombinant human cachectin. Science 234: 470–474, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146. Tracey KJ, Fong Y, Hesse DG, Manogue KR, Lee AT, Kuo GC, Lowry SF, Cerami A. Anti-cachectin/TNF monoclonal antibodies prevent septic shock during lethal bacteraemia. Nature 330: 662–664, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147. Tran LT, MacLeod KM, McNeill JH. Chronic etanercept treatment prevents the development of hypertension in fructose-fed rats. Mol Cell Biochem 330: 219–228, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148. Utsumi T, Takeshige T, Tanaka K, Takami K, Kira Y, Klostergaard J, Ishisaka R. Transmembrane TNF (pro-TNF) is palmitoylated. FEBS Lett 500: 1–6, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149. Van den Berg DT, de Kloet ER, de JW. Central effects of mineralocorticoid antagonist RU-28318 on blood pressure of DOCA-salt hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 267: E927–E933, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150. Van Zee KJ, Moldawer LL, Oldenburg HS, Thompson WA, Stackpole SA, Montegut WJ, Rogy MA, Meschter C, Gallati H, Schiller CD, Richter WF, Loetscher H, Ashkenazi A, Chamow SM, Wurm F, Calvano SE, Lowry SF, Lesslauer W. Protection against lethal Escherichia coli bacteremia in baboons (Papio anubis) by pretreatment with a 55-kDa TNF receptor (CD120a)-Ig fusion protein, Ro 45–2081. J Immunol 156: 2221–2230, 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151. Vandenabeele P, Declercq W, Beyaert R, Fiers W. Two tumour necrosis factor receptors: structure and function. Trends Cell Biol 5: 392–399, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152. Venegas-Pont M, Manigrasso MB, Grifoni SC, LaMarca BB, Maric C, Racusen LC, Glover PH, Jones AV, Drummond HA, Ryan MJ. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha antagonist etanercept decreases blood pressure and protects the kidney in a mouse model of systemic lupus erythematosus. Hypertension 56: 643–649, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153. Vielhauer V, Stavrakis G, Mayadas TN. Renal cell-expressed TNF receptor 2, not receptor 1, is essential for the development of glomerulonephritis. J Clin Invest 115: 1199–1209, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154. Vinciguerra M, Hasler U, Mordasini D, Roussel M, Capovilla M, Ogier-Denis E, Vandewalle A, Martin PY, Feraille E. Cytokines and sodium induce protein kinase A-dependent cell-surface Na,K-ATPase recruitment via dissociation of NF-kappaB/IkappaB/protein kinase A catalytic subunit complex in collecting duct principal cells. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 2576–2585, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155. Wang D, An SJ, Wang WH, McGiff JC, Ferreri NR. CaR-mediated COX-2 expression in primary cultured mTAL cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 281: F658–F664, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156. Wang D, Pedraza PL, Abdullah HI, McGiff JC, Ferreri NR. Calcium-sensing receptor-mediated TNF production in medullary thick ascending limb cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 283: F963–F970, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]