Abstract

Chromatin has been successfully used as a tool for the study of genome function in cancers. Vincristine as a vinca alkaloid anticancer drug exerts its action by binding to tubulins. In this study the effect of vincristine on DNA and chromatin was investigated employing various spectroscopy techniques as well as thermal denaturation, equilibrium dialysis and DNA–cellulose affinity. The results showed that the binding of vincristine to DNA and chromatin reduced absorbance at both 260 and 210 nm with different extent. Chromopheres of chromatin quenched with the drug and fluorescence emission intensity decreased in a dose-dependent manner. Chromatin exhibited higher emission intensity changes compared to DNA. Upon addition of vincristine, Tm of DNA and chromatin exhibited hypochromicity without any shift in Tm. The binding of the drug induced structural changes in both positive and negative extremes of circular dichroism spectra and exhibited a cooperative binding pattern as illustrated by a positive slope observed in low r values of the binding isotherm. Vincristine showed higher binding affinity to double stranded DNA compared to single stranded one. The results suggest that vincristine binds with higher affinity to chromatin compared to DNA. The interaction is through intercalation along with binding to phosphate sugar backbone and histone proteins play fundamental role in this process. The binding of the drug to chromatin opens a new insight into vincristine action in the cell nucleus.

Vincristine binds chromatin with higher avidity than DNA by intercalation along the phosphate-sugar backbone. Histones play a fundamental role in this process.

Introduction

Vincristine is a vinca alkaloid found in the Madagascar periwinkle or catharantus roseus, widely used as an anticancer drug to treat various cancers (Gidding et al., 1999; Gascoigne and Taylor, 2009). It is composed of two multi rings: vindoline and catherantine (Fig. 1) and interacts with β-tubulin at a region adjacent to the GTP-binding site known as vinca domain. It prevents the formation of spindle microtubules disabling the cell's mechanism for aligning and moving the chromosomes (Rai and Wolff, 1996; Jordan and Wilson, 2004; Thomadaki et al., 2009; Sertel et al., 2011). Vincristine not only can induce high frequency of micronuclei (Rosefort et al., 2004; Morales-Ramirez et al., 2004), chromosome aberration, sister chromatid exchange (Arni and Hertner, 1997; Yamada et al., 2000), damage DNA leading to single stranded DNA (Kopjar and Garaj-Vrhovac, 2000) and interferes with DNA, RNA and protein synthesis (Tachihara, 1997; Skladanowski et al., 2005). It also causes increased nerve excitability resulting in axonal degeneration (Kassem et al., 2011).

FIG. 1.

Chemical structure of vincristine.

Most of anticancer drugs exert their biological action through binding to nucleic acids and proteins. It is known that vincristine is a potent inhibitor of topoisomerase II (Skladanowski et al., 2005) and its direct interaction with DNA has been investigated by atomic force microscopy (Zhu et al., 2004) FTIR (Tyagi et al., 2010) and computational NMR and X-ray (Pandya et al., 2012; Kumar et al., 2012). In the cell nucleus DNA is raped around histone octamer producing a compact structure called nucleosomes. There are five main histones: the linker histone, H1 and four core histones (H2A, H2B, H3 and H4) which are arranged in an octamer form (Bradbury and Van Holde, 2004; Grigoryev and Woodcock, 2012).

Although vincristine exerts its antitumor activity by preventing the polymerization of tubulins, to date there is no report on the effect of this drug on chromatin components of cell nucleus. Therefore this is the first paper describing and introducing chromatin as a site of vincristine binding. The results suggest higher binding affinity of vincristine to chromatin compared to DNA implying that histone proteins may play a fundamental role in vincristine action in the cell nucleus. This result represents information which will help in drug design.

Material and Methods

Chemicals

Vincristine sulfate (1 mg/mL freeze-dried) was purchased from Helale Ahmar, Tehran, Iran (manufactured by Chemical Works of Gedeon Richter LTD. Hungary–Budapest). It was dissolved in 10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.4) aliquated and stored at –20°C. DNA and ssDNA–cellulose were from Sigma Chemical Company (USA). DNA was dissolved in 10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.4), dialyzed overnight against the same buffer and its concentration determined using an extinction coefficient of 20 cm−1 mg−1 at 260 nm. Single strand DNA–cellulose (ssDNA–cellulose) resin was suspended in about 10 volumes of 10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.4). After 2–3 washes to remove free DNA, the ss DNA–cellulose resin was stored at a frozen state in Tris–HCl (pH 7.4) plus 0.15 M NaCl.

Double strand DNA–cellulose (dsDNA–cellulose) matrix was prepared according to the method of Alberts et al. (1968). Briefly, a solution of DNA at 1–2 mg/mL in 0.01 M Tris–HCl, pH 7.4 containing 1 mM EDTA, was mixed with clean dry cellulose to give a thick paste. After air-drying overnight at room temperature, the remaining water was removed. The powder was then suspended in about 20 volume of Tris–EDTA and left at 4°C for a day. After two quick washes the dsDNA–cellulose resin was stored at a frozen state at –20°C in Tris–EDTA plus 0.15 M NaCl.

Animals

Albino rats weighing 150–200 g of either sex were used throughout the experiments was obtained from Laboratory Animal Center of IBB (Tehran, Iran). They were maintained in conventional pathogen free conditions in a temperature (22°C–23°C), humidity (50%–70%), and photoperiod (12 h dark/light cycle) controlled room.

Preparation of soluble chromatin

Soluble chromatin was prepared from rat liver nuclei according to the procedure reported before (Rabbani et al., 1999) with some modifications. Briefly, the purified nuclei were suspended in digestion buffer composed of 0.25 M sucrose, 25 mM NaCl, 1 mM CaCl2 and 10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.4) and DNA content determined assuming that the absorbance of 1 mg/mL at 260 nm is 20. The nuclear suspension was digested with micrococcal nuclease (3 units/mg of DNA) for 10 min at 37°C and centrifugation at 8000 g for 5 min. The nuclei were then lysed and the soluble chromatin was recovered in the supernatant.

Spectroscopy

Ultraviolet

DNA and chromatin were incubated with appropriate concentrations of vincristine for 45 min at room temperature in the dark. Control samples containing equal volumes of DNA and chromatin in the same buffer were incubated along with the drug treated samples under the same experimental condition. Drug treated and the controls were then subjected to spectroscopic analysis using Shimadzo UV-260 spectrophotometer, equipped with quartz cuvettes.

Fluorescence

The measurements were carried out using a Carry Eclipse fluorescence spectrophotometer equipped with a thermostatically controlled cell holder at ambient temperature. The monochromatic slits were set at 5 and 10 nm for excitation and emission to reduce the intensity of the signal depending on the experiment. All samples were made in 10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.4) and quartz fluorescence cell of 1 cm path length was used. For DNA and chromatin samples, a wavelength range of 200–700 nm was used after excitation at 258 nm. Ksv, a linear Stern–Volmer quenching constant was also calculated according to Io/I=1+Ksv [Q or vincristine] where Io and I are fluorescence intensities in the absence and presence of the quencher respectively (Gentili et al., 2008).

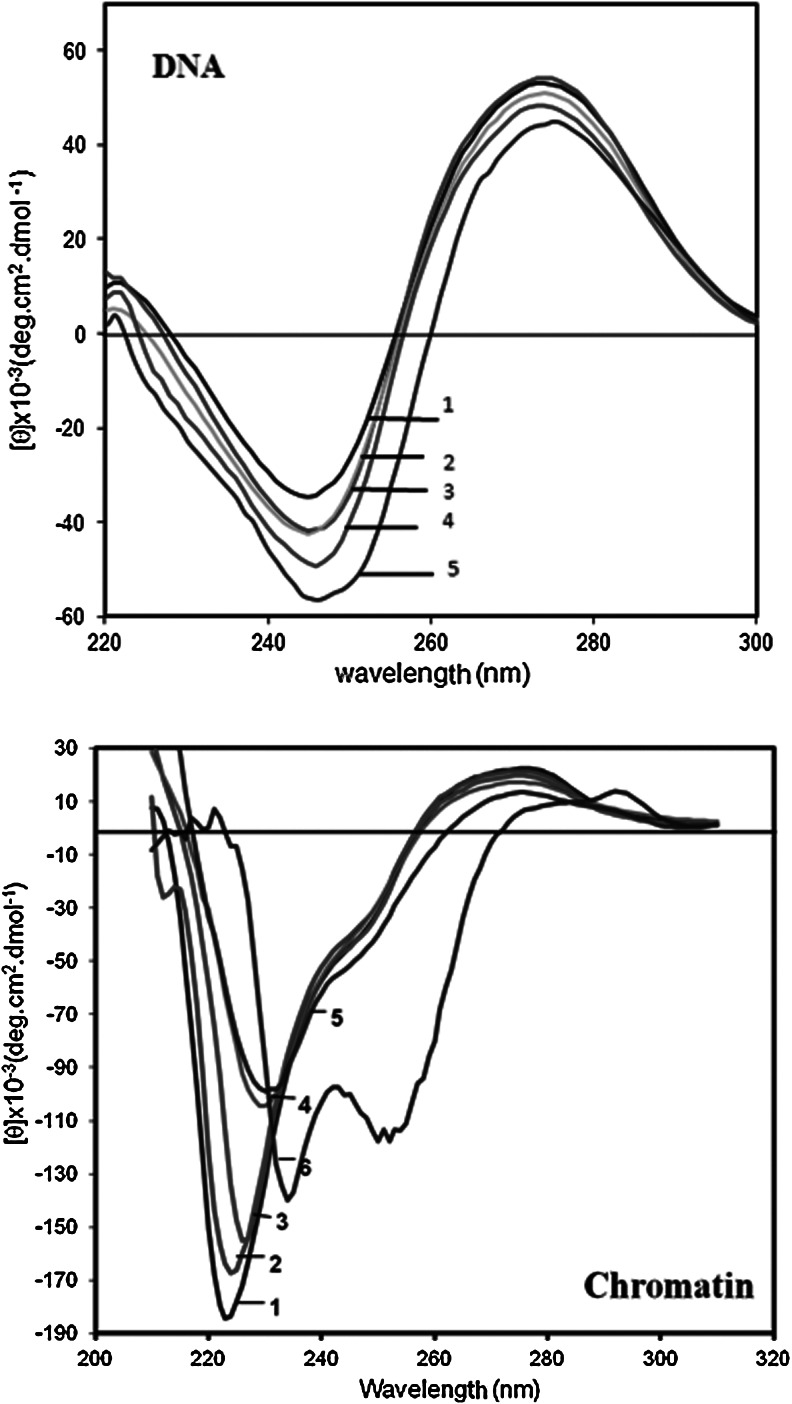

Circular dichroism

The near-ultraviolet (UV) circular dichroism (CD) spectra of DNA and chromatin in 10 mM Tris–HCl (pH7.4) and in the absence and presence of various concentrations of vincristine was recorded in the range of 220–320 nm with a spectral resolution of 1 nm by CD spectrometer model 215 (AVIV instruments, Inc.). The scan speed was 20 nm/min and the response time was 0.3330 s with a bands width of 1 nm. Quartz cell with a path length of 1 cm was used and all measurements were carried out at 23°C–25°C. Results were expressed as molar ellipticity expressed as [θ], in deg×cm2×dmol−1.

Equilibrium dialysis

DNA and chromatin were prepared in 10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.4) and dialyzed against the same buffer containing serial concentrations of vincristine using Spectrum laboratories dialysis tubing at 23°C. The equilibrium was achieved within 72 h. The total drug concentration (Ct) and the concentration of the free drug (Cf) in the dialysate were measured directly before and after dialysis using extinction coefficient of 6600 M−1 cm−1 for the DNA and 15×103 M−1 cm−1 for the drug. The amount of bound drug (Cb) was obtained from Cb=Ct–Cf and binding parameters were determined from the plot of r/Cf versus r according to Scatchard (1949), where r is the ratio of bound drug to total DNA concentration. In this presentation, n (the apparent number of binding sites), is the intercept of the linear region of the binding curve with the horizontal axis. Also K (apparent binding constant) corresponds to the negative value of the slope of the curve and the Hill coefficient value (nH) was determined from the slope of the Ln (r/nr) versus Ln Cf.

Thermal denaturation profiles

Thermal denaturation measurements were carried out by Stoppard quartz cuvettes on a Carry 100 Bio UV-Visible spectrophotometer. The samples in 10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.4) were continuously heated at 1°C/min and absorbance at 260 nm was monitored using the same drug concentration in the reference samples to minimize absorbance of drug at this wavelength. The slope of the melting profiles at temperature T was obtained using dh (T)/dT=h (T+1)−h (T−1)/2 equation (Freifelder, 1982).

DNA-cellulose affinity

The single strand DNA–cellulose (ssDNA) and double strand DNA–cellulose (dsDNA) resins were aliquoted, washed to remove free DNA and the solution was incubated with 1 mL 10 mM Tris–HCl, 5 mM NaCl and different concentration of vincristine for 1 h at room temperature in the dark. Control samples containing equal amounts of DNA in the same buffer were incubated along with the drug treated samples under the same condition. After incubation the samples were centrifuged at 1000 g for 3 min at 4°C and the supernatants were then subjected to spectroscopic analysis.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with Student's t-test (two tailed). p<0.05 was considered as statistically significant. Results are expressed as means±S.D. with n denoting the number of experiments.

Results

Quenching of DNA and chromatin chromophores with vincristine

Various amounts of vincristine were added to a constant amount of DNA and the fluorescence emission intensity recorded e. Excitation at 258 nm produces two emission intensities located 263 nm and 520 nm. Both extremes are affected by vincristine binding and with the same extent, therefore in this experiment fluoresce emission intensity at 263 nm is shown. The results thus obtained, are summarized in Figure 2. As is seen, addition of increasing concentrations of vincristine reduces the fluorescence emission intensity of the DNA without any red shift in the emission maxima (Imax). The emission intensity changes at low concentrations of vincristine (<15 μg/mL) are negligible but at higher concentrations, a considerable decrease in the emission intensity is occurred.

FIG. 2.

Effect of vincristine on fluorescence emission spectra of DNA and chromatin Excitation was at 258 nm and spectra were recorded between 250 and 270 nm. All samples were prepared in 10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.4) and the incubation time after the drug addiction was 45 min. 1–6 are: 0, 5, 10, 15, 25, 50 μg/mL of vincristine, respectively, and DNA concentration was 50 μg/mL. The abbreviation (a.u) is for arbitrary units. Io and I denote fluorescence emission intensity of DNA (▲) and chromatin (■), respectively, in the absence and presence of vincristine. Stern–Volmer plots of fluorescence quenching of DNA and chromatin is also shown. Results are means±SD (n-3).

Fluorescence emission intensity of soluble chromatin in the absence and presence of vincristine is also shown in Figure 2. Chromatin exhibits nearly the same emission spectra pattern to DNA but the extent of the intensity reduction, in the presence of the drug is higher for vincristine–chromatin complex compared to DNA–vincristine one. When the fluorescence emission intensities were normalized to sample concentration and Io−I/Io calculated (Fig. 2) it is shown that at low concentration of vincristine (<15 μg/mL) affinity is the same for DNA and chromatin but at higher concentrations, chromatin exhibits higher affinity to the drug compared to DNA. According to Stern-Volmer equation, Ksv, a linear Stern–Volmer quenching constant, is 0.03 and 0.09 M−1 for DNA and chromatin respectively.

Vincristine alters the secondary structures of DNA and chromatin

To determine whether the binding of vincristine to DNA and chromatin has any effect on their secondary structures, CD spectra was drown in the same experimental condition. As is seen in Figure 3, CD spectrum of DNA in the absence of vincristine exhibits a negative extreme at 245 nm and a positive one at 275 nm. Upon addition of vincristine the ellipticity at 275 nm is decreased whereas, the ellipticity of DNA at 245 nm for 0 and 10 μg/mL of the drug is the same but at higher concentration it is decreased as drug concentration is increased and accompanied with red shift.

FIG. 3.

Near ultraviolet (UV) circular dichroism (CD) spectra of DNA and chromatin in 10 mM Tris–HCl at pH 7.4 in the absence and presence of vincristine. All spectra were recorded between 200 to 320 nm at a scan speed of 2 nm/min at 23°C. 1–5 are 0, 10, 25, 50, 100 and 200 μg/mL of vincristine. The results are means of three individual experiments.

Chromatin in the absence of vincristine also provides two extremes, positive extreme at 275 nm which corresponds to DNA and negative extremes at 208 and 220 nm related to the protein part of the chromatin (Fig. 3 marked by chromatin). No extreme at 245 nm is observed for chromatin possibly due to the binding of histone proteins to DNA molecule. Upon addition of vincristine, the ellipticity at positive extreme is decreased whereas at negative extreme the ellipticity tends to be more positive.

Cooperative binding of vincristine to DNA and chromatin

The binding isotherms obtained from the equilibrium dialysis experiment are shown in Figure 4. The Scatchard plots for DNA and chromatin exhibit a cooperative binding pattern, as illustrated by the positive slope observed in low r regions of the binding isotherm. For DNA the curve reaches a maximum at r=0.5 and decreases in the slope is observed at higher r-values. Drawing r versus Cf, as shown in the insert of Figure 4, clearly demonstrates a sigmoid curve, that is, as Cf increases, r rises rapidly and then levels off, indicating that the system approaches to equilibrium or saturation. The binding constant for the interaction of vincristine estimated from Scatchard plot and fluorescence for DNA and chromatin is k=1.7×104 M−1 and k=5.5×104 M−1 respectively. Drawing Ln r/n-r against Ln Cf gives a straight line with a nH (Hill coefficient) of 1.79 for DNA and 2.17 for chromatin, confirming the positive cooperative binding of the drug.

FIG. 4.

Scatchard plots of the binding of vincristine to DNA and chromatin carried out in 10 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.4 for 72 h at room temperature. Inset is r values against free drug (Cf). Results are means of three individual experiments.

Vincristine-induced hypochromicity in the Tm profile of DNA and chromatin

Thermal denaturation provides strong evidence on the structural stability of macromolecules such as DNA and chromatin. Figure 5 shows derivative thermal denaturation profile of DNA with respect to vincristine concentration and the original absorbance profiles are given in the inset of the Figures. In the absence of the drug, DNA exhibits a typical Tm profile with Tm value at 69°C. Upon addition of vincristine the profile exhibits hypochromicity without any changes in Tm. Comparison of the Tm profile of chromatin (Fig. 5) with that of DNA shows that chromatin in the absence of the drug represents Tm value of 85°C, and a shoulder at 78°C but addition of vincristine to chromatin solution produces hypochromicity without any changes in the Tm values.

FIG. 5.

Absorbance and derivative thermal denaturation profiles of DNA and chromatin in the absence (spectrum 1) and presence of 10, 25, 50, 100 and 200 μg/mL of vincristine (spectra 2–6 respectively). Insets show the absorbance changes of Tm profiles. The samples in 10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.4) were continuously heated at 1°C/min. Number of experiments was 3. UV absorbance changes of DNA (■) and chromatin (▲) in the absence and presence of vincristine monitored at 260 nm. The results are presented as means±SD (n=4).

The UV absorbance changes at 260 are also shown in Figure 5. The absorbance changes were calculated by subtracting the absorbance of the free drug at 260 nm from the absorbance of DNA and chromatin. As is seen, in the case of DNA, at low concentrations of the drug (≤20 μg/mL) absorbance at 260 nm is slightly increased whereas at higher concentrations, a considerable decrease in the absorbance is occurred. Whereas in chromatin, upon addition of vincristine the absorbance at 260 nm is significantly increased and only at high concentrations (>100 μg/mL) of vincristine absorbance is decreased.

Higher affinity of vincristine to dsDNA compared to ssDNA

In the cell nucleous apart from double stranded DNA, we are contrasted with regions containing single stranded DNA such as usually seen in the upstream of active genes, during transcription and replication processes. Therefore it was interesting to elucidate the affinity of vincristine to dsDNA and ssDNA. DNA–cellulose affinity chromatography represents new insights into the binding affinity of ligands to double and single stranded DNA. To this end, the resins were mixed with various concentrations of the drug and incubated for 1 h at 23°C. The samples were then centrifuged to remove the resin and the clear supernatants were subjected to absorbance measurements using multi λ system. The result monitored at 295 nm (absorbance peak for the drug) is shown in Figure 6. Upon addition of vincristine to dsDNA–cellulose, most of the drug is bound to DNA therefore its concentration in the supernatant is decreased. Whereas in ssDNA the drug is mostly remained in the supernatants indicating lower affinity of vincristine to ssDNA compared to dsDNA.

FIG. 6.

Binding affinity of vincristine to single and double strand DNA–cellulose. The resins were equilibrated in 10 mM Tris-HCl pH=7.4 containing 50 mM sodium chloride. Various concentrations of vincristine was added to the resins and incubated for an hour. After centrifugation, the absorbance of the supernatants was monitored at 295 nm. *p=0.05, **p=0.05 and n=3.

Discussion

The cytotoxic effect of anticancer drugs, usually involve recognition by several sites in the cell, between them nuclei is introduced as a major site of drugs interaction. Vinca alkaloid anticancer drugs such as vincristine are known as a microtubule binding which exert their biological action through destroying mitotic spindles (Sertel et al., 2011). Considering the biological implication of vincristine, its interaction with chromatin is an important aspect to be investigated in regard to the suppression of tumor growth.

Although recently the binding of vincristine to DNA has been the subject of several reports (Zhu et al., 2004; Tyagi et al., 2010; Pandya et al., 2012) but in the cell nucleus we are contrasted with nucleosomes which are DNA–histone complexes known as chromatin structural units, the nucleosomes (Bradbury and Van Holde, 2004; Grigoryev and Woodcock, 2012). Also chromatin has been successfully used as a tool for the study of genome function in cancers (Urnov, 2003). Therefore this is the first paper describing the effect of vincristine in the chromatin context.

According to the results obtained it is suggested that vincristine binds to DNA and chromatin cooperatively but with different extents. Reduction of fluorescence emission intensity and estimation of binding affinity by both Io−I/Io values and Stern Volmer constant imply quenching of the drug chromophores with DNA and that vincristine exhibits higher affinity to chromatin compared to DNA. The behavior is in contrast to the binding of anthracycline antibiotics to DNA and chromatin (chaires et al., 1983; Cera and Dalumbo, 1990) but is similar to the effect of mitoxantrone in which prefers chromatin structure rather than free DNA (Hajihassan and Rabbani-Chadegani, 2009). Binding of vincristine to DNA and chromatin changes the absorbencies at 260 and 210 nm in a dose dependent manner indicating participation of both phosphate groups and bases of DNA in the interaction with the drug. Vincristine, at low concentrations, announces perturbation/unfolding of DNA and chromatin structure whereas at higher concentration precedes DNA and chromatin into compaction. This is almost similar to the interaction of anthracycline antibiotics with chromatin and DNA (Rabbani et al., 1999). The increase in the absorbance of chromatin in the presence of vincristine can be attributed to the removal of histone proteins from the DNA in which exposes DNA chromopheres to render the absorbance to higher values.

The ellipticity of chromatin at 275 nm is essentially diminished to one half of DNA ellipticity by wrapping DNA around histone core to make nucleosomes. Alteration of CD spectra of DNA in the presence of vincristine, demonstrates that both base pairing and superhelicity of DNA is altered upon drug binding. This together with the results obtained above suggest that the binding of vincristine to DNA is not only via intercalation but also sugar–phosphate backbone participates in this process. The ellipticity of chromatin at 222 nm is increased and shifted into higher wavelengths (red shift). This alteration can be attributed not only to reduction of α-helix structure of histone proteins but also removal of histone proteins from DNA and appearance of a peak around 245 nm which corresponds partly to naked DNA. As the complex between chromatin and the drug is soluble detection of histone proteins release is difficult. Also we could not observe any protein release from the chromatin in Hep2 cell cultures incubated in the presence of vincristine except for HMGB protein (data not shown), the work which need further investigation.

As vincristine acts at the protein level (microtubules) to exert its antitumor action, it is possible that vincristine also binds to histone proteins to increase its cytotoxic effect. This is shown not alteration of chromatin CD specta at 222 nm but also we performed fluorescence emission intensity for chromatin using excitation at 278 nm to elucidate the possible interaction (quenching) of vincristine with tyrosine or phenylalanine amino acid residues of histone proteins. The result indicated that the fluorescence emission intensity between at 306) nm is considerably reduced upon increasing drug concentration implying that histone proteins also participate in this binding process (data not shown).

Thermal stability of the DNA remains essentially unchanged by increasing drug concentration, indicating that binding of vincristine to DNA covers the surface of DNA or produces some kind of compaction resulting in absorbance reduction at 260 nm as illustrated as a hypochromicity. The behavior of thermal stability of chromatin in the presence of vincristine is similar to DNA except that chromatin itself shows higher Tm values corresponding to DNA-histone complex or compact structure of nucleosomes. Moreover vincristine recognizes dsDNA with higher affinity than ssDNA.

Binding of vincristine to DNA and chromatin exhibits a cooperative binding pattern as illustrated by the positive slope and Hill coefficients higher than 1 which confirm cooperative binding patterns. The binding constants obtained for DNA (k=1.7×104 M−1) and chromatin (k=5.5×104 M−1) demonstrate higher binding affinity of vincristine to chromatin compared to DNA. The binding constant of DNA is similar to the value reported by Pandya et al. (2012) and to the binding constant reported for strong DNA intercalator like daunomycin (Rabbani et al., 1999), however it is higher than the value obtained from FTIR (Tyagi et al., 2010). It should be mentioned that cooperative binding constant estimated for the binding of vincristine to DNA and chromatin using Hill equation represents higher binding constant in the range of 197–109. Calculation of free energy changes represents exergonic and spontaneous reaction as ΔG was −5.7 and −6.4 kcal mol−1 for DNA and chromatin respectively.

Taking all together it is concluded that vincristine apart from microtubules, shows high affinity to DNA and chromatin and in this context, its effect on chromatin is more potent than on DNA. The binding of vincristine alters chromatin structure somehow that perturbs histone-DNA interaction and possibly removal/displacement of the histones from DNA is occurred. The drug preferentially affects the whole genome without any preference to single stranded DNA. Vincristines possess several sites of interaction with DNA and chromatin. Apart from its planar ring systems, it contains donor/acceptor sites O-H and N-H in the catherantine half and –CHO group at the indoline ring nitrogen in the vindoline half for H-bond. It is suggested that vincristine binds to DNA molecule through intercalation between DNA bases and H-bond with sugar-phosphate backbone and also bases. Moreover vincristine with its vindoline and catherantine domains can penetrate into histones globular head domain via hydrophobic interaction. Between the histone proteins, histone H1 can be considered as a preferred site of drug binding as it is located in the linker regions which is more exposed into environment, however an extensive work is needed to elucidate the binding sites and define which histone is particularly contribute.

Acknowledgment

The work was financially supported by a grant (#6401017/6/17) of the University of Tehran to A.R.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Alberts B. Amodio F. Jenkins M. Gutman E. Ferris F. Studies with DNA-cellulose chromatography. I. DNA-binding proteins from escherichia coli. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1968;33:289–305. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1968.033.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arni P. Hertner T. Chromosomal aberrations in vitro induced by aneugens. Mutat Res. 1997;379:83–93. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(97)00111-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury E.M. Van Holde K.E. Chromatin structure and dynamics: A historical perspective. In: Zlatanova J., editor; Leuba S.H., editor. Chromatin Structure and Dynamics: State of the Art. Elsevier, Amesterdam; The Netherlands Elsevier: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cera C. Dalumbo M. Anticancer activity of anthracycline antibiotics and DNA condensation. Anticancer Drugs. 1990;5:265–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaires J.B. Dattagupta N. Crothes D.M. Binding of daunomycin to calf thymus nucleosomes. Biochemistry. 1983;22:284–292. doi: 10.1021/bi00271a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freifelder D.M. Physical Biochemistry, Application to Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. Second. Freeman press; New York: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Gascoigne K.E. Taylor S. How do anti-mitotic drugs kill cancer cells? J Cell Sci. 2009;122:2579–2585. doi: 10.1242/jcs.039719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentili P.L. Ortica F. Favaro G. Static and dynamic interaction of a naturally occurring photochromic molecule with bovine serum albumin studied by UV-visible absorption and fluorescence spectroscopy. J Phys Chem B. 2008;112:16793–16801. doi: 10.1021/jp805922g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gidding C.E.M. Kellie S.J. Kamps W.A. Graaf S.S.N. Vincristine revisited. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 1999;29:267–287. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(98)00023-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigoryev S.A. Woodcock C.L. Chromatin organization-the 30 m fiber. Exp Cell Res. 2012;318:1448–1455. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2012.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajihassan Z. Rabbani-Chadegani A. Studies on the binding affinity of anticancer drug mitoxantrone to chromatin and histone proteins. J Biomed Sci. 2009;16:31–36. doi: 10.1186/1423-0127-16-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan M.A. Wilson L. Microtubules as a target for anticancer drugs. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:253–265. doi: 10.1038/nrc1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassem L.A. Gamal El-Din M.M. Yassin N.A. Mechanisms of vincristine-induced neurotoxicity: Possible reversal by erythropoietin. Drug Discov Ther. 2011;5:136–146. doi: 10.5582/ddt.2011.v5.3.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopjar N. Garaj-Vrhovac V. Application of cytogenetic endpoints and comet assay on human lymphocytes treated with vincristine in vitro. Neoplasma. 2000;47:162–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S. Pandya P. Pandav K. Gupta S.P. Chopra A. Structural studies on ligand-DNA systems: A robust approach in drug design. J Biosci. 2012;37:553–561. doi: 10.1007/s12038-012-9212-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales-Ramirez P. Vallarino-Kelly T. Cruz-Vallejo V. Kinetics of micronucleated polychromatic erythrocyte (MN-PCE) induction in vivo by aneuploidogens. Mutat Res. 2004;565:79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandya P. Gupta S.P. Pandav K. Barthwal R. Jayaram B. Kumar S. DNA binding studies of vinca alkaloids:experimental and computational evidence. Nat Prod Commun. 2012;7:305–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rai S.S. Wolff J. Localization of the vinblastine- binding site on beta-tubulin. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:14707–14711. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.25.14707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabbani A. Iskander M. Ausio J. Daunomycin-induced unfolding and aggregation of chromatin. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:18401–18406. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.26.18401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosefort C. Fauth E. Zankl H. Micronuclei induced by aneugens and clastogens in mononucleate and binucleate cells using the cytokinesis block assay. Mutagenesis. 2004;19:277–284. doi: 10.1093/mutage/geh028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scatchard G. The attraction of proteins for small molecules and ions. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1949;51:660–672. [Google Scholar]

- Sertel S. Fu Y. Zu Y. Rebacz B. Konkimalla B. Plinkert P.K. Kramer A. Gertsch J. Efferth T. Molecular docking and pharmacogenomics of vinca alkaloids and their monomeric precursors, vindoline and catharanthine. Biochem Pharmacol. 2011;81:73–735. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skladanowski A. Come M.G. Sabisz M. Escargueil A.E. Larsen A.K. down-regulation of DNA topoisomerase II_ leads to prolonged cell cycle transit in G2 and early m phases and increased survival to microtubule-interacting agents. Mol pharmacol. 2005;68:625–634. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.013995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tachihara R. The effect of dacarbazine and vincristine sulfate on human melanoma cell lines. In vitro analysis of intraction on DNA synthesis, RNA synthesis and protein synthesis. Nihon Ika Daiqaka zasshi. 1997;64:238–248. doi: 10.1272/jnms1923.64.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomadaki H. Floros K.V. Scorilas A. Molecular response of HL60 cells to mitotic inhibitors vincristine and taxol visualized with apoptosis-related gene expressions including the new member BCL2L12. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1171:276–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyagi G. Jangir D.K. Singh P. Mehrotra R. DNA interaction studies of an anticancer plant alkaloid, vincristine, using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. DNA Cell Biol. 2010;29:693–699. doi: 10.1089/dna.2010.1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urnov F.D. Chromatin as a tool for study of genome functions in cancer. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2003;983:5–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb05958.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada T. Odawara K. Kaneko H. Concurrent detection of gene mutations and chromosome aberrations induced by five chemicals in a CHL/IU cell line incorporating a gpt shuttle vector. Mutat Res. 2000;471:29–36. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5718(00)00115-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y. Zeng H. Xie J. Ba L. Gao X. Lu Z. Atomic Forece Microscopy studies on DNA structural changes induced by vincristine sulfate and aspirin. Microscopy Microanal. 2004;10:286–290. doi: 10.1017/S1431927604040127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]