Abstract

Although cocaine readily induces taste aversions, little is known about the mechanisms underlying this effect. Recent work has shown that cocaine’s actions on serotonin (5-HT) may be involved. To address this possibility, the present experiments examined a role of the specific 5-HT receptor, 5-HT3, in this effect given that it is implicated in a variety of behavioral effects of cocaine. This series of investigations first assessed the aversive effects of the 5-HT3 receptor antagonist tropisetron alone (Experiment 1). Specifically, in Experiment 1 male Sprague-Dawley rats were exposed to tropisetron (0, 0.056, 0.18 and 0.56 mg/kg) prior to the pairing of a novel saccharin solution. Following this, a non-aversion-inducing dose of tropisetron (0.18 mg/kg) was assessed for its ability to block aversions induced by a range of doses of cocaine (Experiment 2). Specifically, in Experiment 2 animals were given access to a novel saccharin solution and then injected with tropisetron (0 or 0.18 mg/kg) followed by an injection of various doses of cocaine (0, 10, 18, and 32 mg/kg). Cocaine induced dose-dependent taste aversions that were not blocked by tropisetron, suggesting that cocaine’s aversive effects are not mediated by 5-HT, at least at this specific receptor subtype. At the intermediate dose of cocaine, aversions appeared to be potentiated, suggesting 5-HT3 may play a limiting role in cocaine’s aversive effects. These data are discussed in the context of previous examinations of the role of serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine in cocaine-induced aversions.

Keywords: cocaine, tropisetron, conditioned taste aversions, antagonism, serotonin

1. INTRODUCTION

Drugs of abuse, including cocaine, have been shown to have both rewarding (Kosten et al., 1997, Nomikos and Spyraki, 1988, Wise et al., 1992) and aversive (Ettenberg, 2004, Ferrari et al., 1991, Goudie et al., 1978) effects, and the balance of these effects is thought to contribute to their overall abuse potential (Hunt and Amit, 1987, Kohut and Riley, 2010, Riley et al., 2009). Understanding the neurochemical basis for these affective properties may be important in understanding the differences in individual vulnerability to drug abuse (Cunningham et al., 2009, Freeman et al., 2008, for a review see Riley, 2011).

In relation to cocaine, its action as a dopamine transporter (DAT) inhibitor appears to be largely involved in its rewarding effects (Chen et al., 2006, Ritz et al., 1987; for a review and discussion of other monoamine involvement, see Uhl et al., 2002). However, the mechanism underlying its aversive effects is less understood. Although relatively fewer reports have investigated cocaine’s aversive effects, several have implicated its actions on DA (Freeman et al., 2005, Serafine et al., 2012a, Serafine et al., 2012b). For example, Freeman and colleagues demonstrated that cocaine and the selective DAT inhibitor GBR 12909 induce similar dose-dependent acquisition of conditioned taste aversions (CTA; see Freeman et al., 2005). Specifically, they reported that aversions induced by both compounds at the highest dose tested (50 mg/kg) were comparable in both the rate of acquisition and degree of the aversion. Recently, our laboratory has demonstrated an involvement of DA via the use of the cross-drug preexposure preparation (Serafine et al., 2012a). Specifically, animals exposed to GBR 12909 prior to aversion conditioning with cocaine displayed attenuated cocaine-induced aversions suggestive of adaptation or tolerance to some common stimulus properties, presumably DA related, during preexposure (De Beun et al., 1996, Gommans et al., 1998, Serafine and Riley, 2009). Further, Serafine and colleagues reported that the nonselective DA receptor antagonist haloperidol blocked the acquisition of cocaine-induced CTAs (Serafine et al., 2012a), directly implicating a role of DA in cocaine’s aversive effects (see also Hunt et al., 1985).

Although DA is highly implicated in the aversive effects of cocaine, recent work has also shown that cocaine’s actions on serotonin (5-HT) may also be involved. For example, Sora and colleagues (Sora et al., 1998, Sora et al. 2001) found that transgenic knock-out (KO) mice without the 5-HT transporter (SERT) displayed an increase in cocaine-induced conditioned place preferences. They interpreted this increase in SERT KO mice to be a function of the removal of the aversive effects of cocaine (presumably mediated via its action on 5-HT), allowing for a greater overall rewarding effect of cocaine (presumably mediated via its actions on DA; see also Uhl et al., 2002). According to this position, cocaine’s actions on SERT limit the rewarding effects of reward and the removal of the transporter in the KO mice eliminates this aversive effect. In support of this suggestion, our laboratory has recently reported that preexposure to cocaine significantly attenuated aversions induced by fluoxetine, a selective 5-HT reuptake inhibitor (see Serafine and Riley, 2010). Given that such an attenuation is typically interpreted as a function of adaptation to some aversive stimulus property shared between both drugs, this attenuation suggests a role for 5-HT in aversions induced by the two compounds (since 5-HT levels are enhanced by SERT inhibition by both cocaine and fluoxetine). Interestingly, preexposure to fluoxetine had no effect on cocaine-induced aversions, suggesting that although the two drugs share stimulus properties, they are not identical (see Serafine and Riley, 2010)

Although 5-HT may mediate in part the aversive effects of cocaine, it is not known what specific receptor system is involved in this effect. Of the range of 5-HT receptor subtypes, a few (specifically, 5-HT1A, 5-HT1B, 5-HT2A, 5-HT2C and 5-HT3) have been implicated in the behavioral effects of cocaine, including its affective (rewarding) properties (Harrison and Markou, 2001, Parsons et al., 1998, Kankaanpaa et al., 2002 respectively; see, Hayes and Greenshaw, 2011, Muller and Huston, 2006 for reviews). For example, the 5-HT3 receptor antagonist Y-25130 has been reported to attenuate cocaine’s ability to lower intracranial self stimulation thresholds in rats (Kelley and Hodge, 2001; for similar attenuating effects of the 5-HT3 receptor antagonist MDL722 on cocaine-induced place preferences, see Kankaanpa et al., 2002; Suzuki et al., 1992). Interestingly, the 5HT3 receptor antagonist tropisetron has been reported to block place aversions induced by 1-phenylbiguanide (PBG, a 5HT3 receptor agonist; Higgins et al., 1993), suggesting that this receptor subtype may mediate the aversive effects of drugs acting on 5-HT receptors. Accordingly, Experiment 2 examined the ability of tropisetron to affect cocaine-induced taste aversions. If cocaine induces aversions that are mediated in part by its ability to increase 5-HT activity at 5-HT3 receptor subtypes, tropisetron should attenuate such effects. Prior to this assessment, the ability of tropisetron to induce aversions on its own was first examined (Experiment 1).

2. GENERAL METHODS

2.1 Apparatus

All subjects were individually housed in stainless-steel, hanging wire-mesh cages on the front of which graduated Nalgene tubes could be placed for fluid presentation. Subjects were maintained on a 12:12 light-dark cycle (lights on at 0800h) and at an ambient temperature of 23 °C. Except where noted, food and water were available ad libitum

2.2 Subjects

The subjects were 96 experimentally naïve, male Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan Sprague Dawley, Indianapolis, Indiana) approximately 75 days old and between 250 and 350 g at the start of the experiment. Procedures recommended by the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (1996, 2003) and the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at American University were followed at all times. Animals were handled daily approximately 2 weeks prior to the initiation of the study to limit the effects of handling stress during conditioning and testing.

2.3 Drugs and Solutions

Tropisetron hydrochloride (synthesized at the Chemical Biology Research Branch of the National Institute on Drug Abuse) was prepared in saline at a concentration of 0.5 mg/ml and was subsequently filtered through a 0.2 μm filter to remove any contaminants and administered intraperitoneally (IP). Cocaine hydrochloride (generously provided by the National Institute on Drug Abuse) was dissolved in distilled water at a concentration of 10 mg/ml and was subsequently filtered through a 0.2 μm filter to remove any contaminants and administered subcutaneously (SC). Cocaine doses are expressed as the salt. Saccharin (sodium saccharin, Sigma) was prepared as a 1 g/l (0.1%) solution in tap water.

2.4 Procedure

2.4.1 Habituation

Following 24-h water deprivation, subjects were given 20-min access to tap water daily. This daily access was repeated until consumption stabilized, i.e., subjects approached and drank from the tube within 2 S of its presentation and water consumption was within 2 ml of the previous day for a minimum of 4 consecutive days with no consistent increase or decrease. Throughout the study, fluid was presented in graduated 50-ml Nalgene tubes and measured to the nearest 0.5 ml by subtracting the difference between the pre- and post-consumption volumes.

2.4.2 Conditioning

On Day 1 of conditioning, all subjects were given 20-min access to the novel saccharin solution. Immediately following this presentation, animals in each experiment were rank ordered based on saccharin consumption and assigned to treatment groups (n = 7 - 8 per group) such that overall consumption was comparable among groups. Immediately after rank ordering animals were injected with tropisetron or vehicle (Experiment 1) or tropisetron or vehicle followed by an injection of cocaine (0, 10, 18, 32 mg/kg) 30 min later (Experiment 2).

3. EXPERIMENT 1

Although administration of tropisetron and other 5-HT3 receptor antagonists alone typically does not result in any observable effects (Hendrie, 1990), when using pharmacological antagonists to assess mechanism in the CTA design, it is important to consider the possibility that administration of the antagonist prior to saccharin and cocaine could impact aversion learning independent of its effects of cocaine, e.g., by affecting taste sensitivity or drinking in general. One way to circumvent this issue is to administer the antagonist after saccharin consumption but prior to cocaine (Bienkowski et al., 1997, Freeman et al., 2008, Serafine et al., 2012b). Since many compounds when administered immediately after saccharin can (at least at some doses) induce CTAs on their own (for a discussion of this issue, see Freeman et al., 2008, Serafine et al., 2012b), it is important to determine a dose of the antagonist that does not induce a CTA alone prior to assessing its effect on cocaine-induced aversions. Accordingly, in Experiment 1 animals were given access to a novel saccharin solution and injected with one of a number of doses of tropisetron to assess its ability to induce aversions. Following conditioning, the effects of tropisetron on food consumption were monitored as a collateral assessment of any potential behavioral suppression induced by the antagonist.

4. Method

4.1 Conditioning

During conditioning, 31 subjects were given access to saccharin and injected immediately thereafter with 0, 0.056, 0.18 or 0.56 mg/kg tropisetron, yielding Groups 0, 0.056, 0.18 and 0.56; specifically, Group 0 (n = 7), Group 0.056 (n = 8), Group 0.18 (n = 8), and Group 0.56 (n = 8). The vehicle group (Group 0) was matched in volume to the group receiving the high dose of tropisetron (Group 0.56). The specific doses (0.056 mg/kg, 0.18 mg/kg, and 0.56 mg/kg) used in this initial assessment were based on the doses of tropisetron used by Higgins and colleagues in their assessment of the effects of tropisetron on PBG-induced place aversions (see above, Higgins et al., 1993). The 3 days following this initial conditioning trial were water-recovery days during which animals were given 20-min access to tap water (no injections followed this access). This alternating procedure of conditioning/water recovery was repeated for a total of four complete cycles. Following the last water-recovery session after the fourth conditioning trial, animals were given 20-min access to both saccharin and tap water in a final two-bottle aversion test. Specifically, both the saccharin- and water-filled Nalgene tubes were placed on the cages simultaneously with the placement of the tubes (left or right side) counterbalanced across subjects to prevent positioning effects. No injections were administered after this test.

4.2 Feeding Assessment

4.2.1 Free feeding access

Following the two-bottle test, subjects were returned to ad libitum water access for 11 days during which no saccharin or injection was given. Food access was also ad libitum and was measured over the last 3 days of this period. The absolute amount of food consumed was determined by subtracting the amount of food remaining in the cage or fallen through the cage floor from the total food initially made available.

4.2.3 Restricted access

On the next day, 50% of the average daily amount of food consumed during free access was made available for 23 h (the calculation and preparation of the food took approximately 1 h during which time subjects had no access to food or water). At the conclusion of this 23-h period, any food which had fallen through the cage floor was measured and subtracted from the total food initially made available (on 23-h 50% restricted access sessions animals always consumed the entirety of the food and as such only the fallen food was measured). Subjects were then given 23 h of ad libitum access to food. Consumption was measured after 2 h and then again at the end of the end of the 23-hr ad libitum access period. This alternating schedule of 23-h 50% restricted access followed by 23-h ad libitum access period (with consumption measured at 2 and 23-h after food presentation) was repeated a total of three times.

4.2.4 Tropisetron feeding assessment

Following the last cycle of the above phase, subjects again were given 23-h of restricted access followed by 23-h access to free feeding. Immediately prior to free-food access subjects were given a Baseline Session in which they were given an IP injection of vehicle (matched in volume to the highest dose of tropisetron, 0.56 mg/kg). They were given the 23-h ad libitum access period (with consumption measured at 2 and 23-h, as previously described). Following the 5th 50% restricted access day, subjects were given a Test Session where they were given an IP injection of either vehicle or tropisetron 30-min prior to the ad libitum access to food. The dose administered matched the dose given during conditioning (0, 0.056, 0.18, and 0.56 mg/kg) for individual subjects. Consumption was measured 2 h following food presentation.

4.3 Statistical Analysis

The differences in mean saccharin consumption during conditioning were analyzed using a 4 x 4 mixed model ANOVA with the between-subjects factor of Group (0, 0.056, 0.18 and 0.56 mg/kg) and the within-subjects factor of Trial (1–4). Trial differences were analyzed using a paired samples t-test with a Bonferroni correction setting the significance to p ≤0.0083. The differences in percent saccharin consumed and total fluid consumed during the two-bottle test were analyzed using a one-way ANOVA with the between-subjects variable of Group (0, 0.056, 0.18 and 0.56 mg/kg). A 4 x 2 mixed model ANOVA with a between-subjects factor of Group (0, 0.056, 0.18 and 0.56 mg/kg) and a within-subjects factor of Session (Baseline or Test) was used to analyze the 2-h access food consumption following the vehicle or drug injection. Where appropriate, Tukey post hoc analysis was used to determine specific group differences. All significance levels were set at p ≤0.05 unless otherwise noted.

5. Results

5.1 Dose Response Assessment

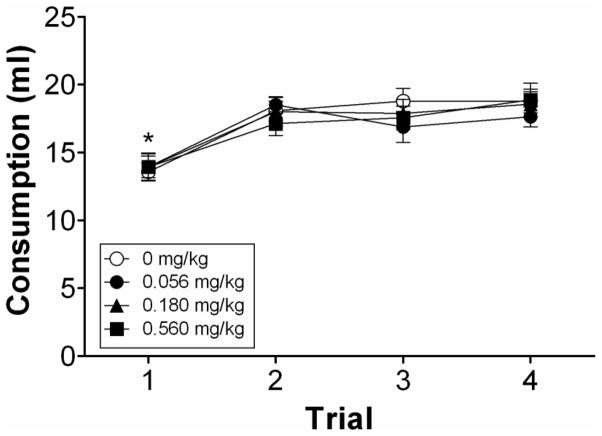

The 4 x 4 mixed model ANOVA on saccharin consumption during conditioning revealed a significant effect of Trial [F (3, 81) = 41.949, p < 0.001]. Regarding the Trial effect, paired samples t-tests revealed Trial 1 consumption was significantly less than all other trials (Trial 2, Trial 3, Trial 4, all ps < 0.001). There was no effect of Group and no significant Trial X Group interaction (see Figure 1). Specifically, all groups consumed saccharin at high levels and significantly increased consumption over repeated trials.

Figure 1.

Mean (± SEM) saccharin consumption (ml) for subjects conditioned with tropisetron (0.056, 0.18, or 0.56 mg/kg) or vehicle (0 mg/kg). There was a significant effect of Trial. *Significantly different from Trial 2, Trial 3, and Trial 4.

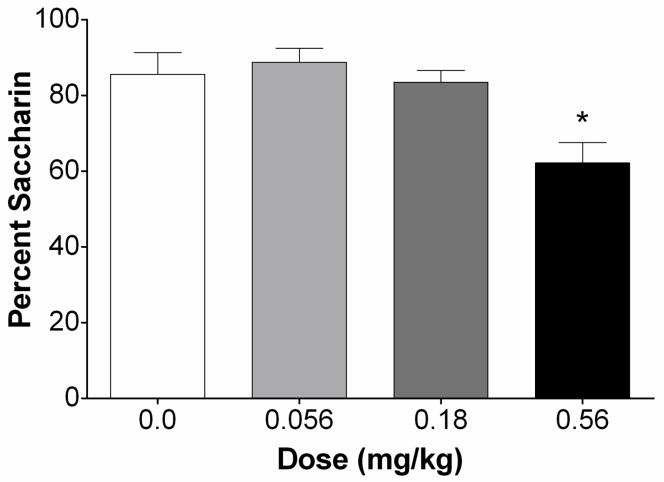

Analysis of the percent saccharin consumed on the final two-bottle aversion test revealed that subjects injected with the high dose of tropisetron (Group 0.56) consumed significantly less percent saccharin than all other subjects (Groups 0, 0.18, and 0.056; all ps < 0.05), indicating that the high dose (0.056 mg/kg) induced a significant CTA relative to vehicle and the two lower doses of tropisetron. There were no significant differences in total fluid consumed among groups (data not shown).

5.2 Feeding Assessment

The 4 x 2 mixed model ANOVA revealed a significant effect of Session [F (1, 27) = 7.719, p = 0.010]. In relation to the Session effect, overall food intake increased from Baseline to Test. Specifically, average food intake was approximately 6.8 and 7.6 g on the Baseline and Test, respectively. There was no effect of Group and no significant Session X Group interaction.

6. EXPERIMENT 2

In Experiment 1, various doses of tropisetron (0, 0.056, 0.18, and 0.56 mg/kg) were examined to establish a dose of the antagonist that could be administered following saccharin consumption (and prior to cocaine) without the likelihood of inducing an aversion on its own which might confound any interpretation of its antagonist effects on cocaine. As noted, only the highest dose (0.56 mg/kg) tested induced a CTA and even here this was evident only after repeated conditioning trials and in the relatively sensitive two-bottle test (for an overview of the relative sensitivy of the one- vs two-bottle aversion test, see Batsell and Best, 1993, Spector et al., 1981). This general lack of an effect of tropisetron is supported by its failure to affect food consumption at any dose and consistent findings that 5-HT3 receptor antagonists rarely produce effects on their own and that their activity appears inert except at toxic doses (Hendrie, 1990). Given that there was no difference among doses during the feeding assessment and that previous research has shown tropisetron’s ability (at 0.1 mg/kg) to block place aversions induced by the 5-HT3 receptor agonist PBG (Higgins et al., 1993), 0.18 mg/kg was used in the following assessment of the effects of tropisetron on cocaine-induced CTAs.

7. Method

7.1 Conditioning

Subjects in Experiment 2 were run in two replicates (n = 32: Replicate 1; n = 32: Replicate 2). During conditioning, subjects were given a novel saccharin solution to drink followed by an injection of 0.18 mg/kg tropisetron (based on the results from Experiment 1). Thirty min following this injection, different groups of subjects were given a SC injection of cocaine (10, 18 or 32 mg/kg) or vehicle (matched in volume to 32 mg/kg cocaine), yielding eight experimental groups, specifically, vehicle-vehicle (V0; n = 8), vehicle-10 mg/kg cocaine (V10; n = 8), vehicle-18 mg/kg cocaine (V18; n = 8), vehicle-32 mg/kg cocaine (V32; n = 8), tropisetron-vehicle (T0; n = 8), tropisetron-10 mg/kg cocaine (T10; n = 8), tropisetron-18 mg/kg cocaine (T18; n = 8) and tropisetron-32 mg/kg cocaine (T32; n = 8). The first letter in each group designation refers to the pretreatment drug (Tropisetron, T, or Vehicle, V); the number refers to the dose of cocaine given during conditioning. The specific doses of cocaine used in this assessment were based on previous work reporting the ability of these doses to produce graded aversions that ranged from little to intermediate to near complete suppression (see Ferrari et al., 1991, Freeman et al., 2005). Such a dose range provides behavioral effects that are subject to modulation and allow for attenuation or potentiation of aversions to be seen. The 3 days following this initial saccharin presentation were water-recovery days, during which animals were given 20-min access to tap water (no injections followed this access). This alternating procedure of conditioning and water recovery was repeated for a total of four complete cycles. Following the last water-recovery session after the fourth conditioning trial, animals were given 20-min access to saccharin and water in a final two-bottle aversion test (as described in Experiment 1).

7.2 Statistical Analysis

The differences in mean saccharin consumption during conditioning were analyzed using a 2 x 2 x 4 x 4 mixed model ANOVA with the between subjects factors of Pretreatment Drug (tropisetron or vehicle), Replicate (1 or 2) and Conditioning Dose (0, 10, 18 and 32 mg/kg cocaine) and the within subjects factor of Trial (1–4). The differences in percent saccharin consumed and total fluid consumed during the two-bottle test were analyzed using a 2 x 4 univariate ANOVA with the between-subjects variables of Pretreatment Drug (Vehicle or Tropisetron) and Conditioning Dose (0, 10, 18 and 32 mg/kg cocaine). Where appropriate, Tukey post hoc analysis was used to determine specific group differences. All significance levels were set at p ≤0.05 unless otherwise noted.

8. Results

8.1 Antagonism Assessment

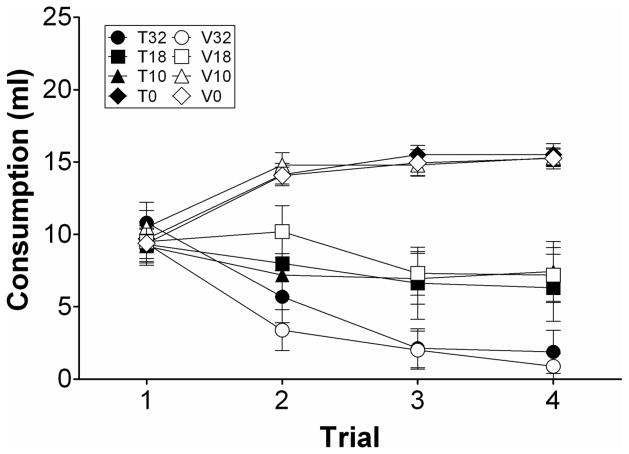

The 2 x 2 x 4 x 4 mixed model ANOVA revealed no significant effect of Replicate. Consequently, the data across the two replicates were pooled for presentation. The mixed model ANOVA did reveal a significant effect of Trial [F (3, 144) = 4.180, p = 0.007] and Conditioning Dose [F (3, 48) = 16.453, p < 0.001] but no significant effect of Pretreatment Drug [F (1, 48) = 1.097, p = 0.3]. There was a significant a significant Trial X Conditioning Dose interaction [F (9, 144) = 25.527, p < 0.001]. In relation to the significant Trial X Conditioning Dose interaction, Tukey post hoc tests, collapsed across Pretreatment Drug, revealed no significant differences between Conditioning Dose on Trial 1. On Trial 2, subjects, injected with 32 mg/kg cocaine differed from all other groups (all ps < 0.024). On Trials 3 and 4, subjects injected with 32 mg/kg cocaine again differed from all other groups (all ps < 0.01) and subjects injected with 18 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg differed from vehicle (both ps < 0.011) (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Mean (± SEM) saccharin consumption (ml) for subjects pretreated with tropisetron (0 or 0.18 mg/kg) and conditioned with cocaine (0, 10, 18, 32 mg/kg). There was a significant effect of Trial and Trial X Conditioning Dose.

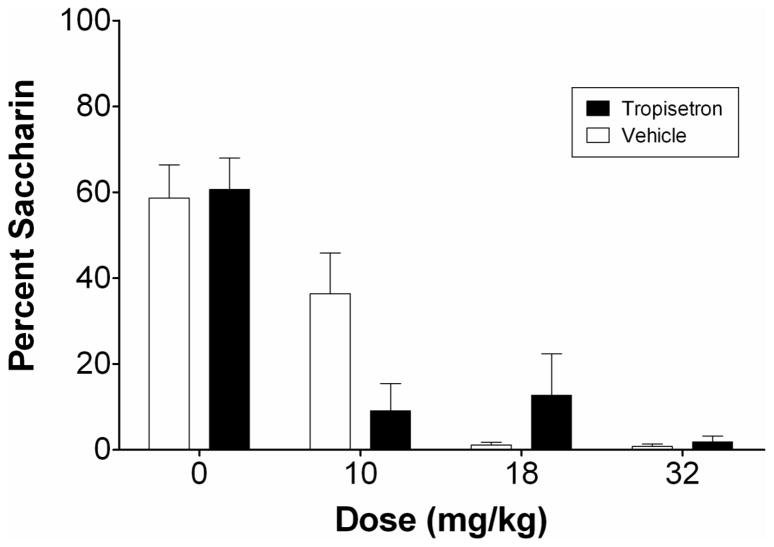

Analysis of the percent saccharin consumed on the final two-bottle aversion test revealed no significant effect of Pretreatment Drug [F (1, 56) = 0.198, p = 0.658] or Pretreatment Drug X Conditioning Dose [F (3, 56) = 2.505, p = 0.068] interaction. There was a significant effect of Conditioning Dose [F (3, 56) = 32.517, p < 0.001]. In relation to the significant effects of Conditioning Dose, Tukey post hoc tests, collapsed across Pretreatment Drug, revealed that all drug-injected subjects drank significantly less than subjects injected with vehicle (0 mg/kg) (all ps < 0.001). Subjects injected with 32 mg/kg drank significantly less than subjects injected with 10 mg/kg (p = 0.030) (see Figure 4). There were no significant differences in total fluid consumed among groups (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Mean (± SEM) percent saccharin consumption for subjects pretreated with tropisetron (0 or 0.18 mg/kg) and conditioned with cocaine (0, 10, 18, 32 mg/kg). There was a significant effect of Conditioning Dose.

9. DISCUSSION

In Experiment 2, the role of 5-HT3 receptor antagonism on cocaine’s aversive effects was examined. Specifically, animals were treated with the 5HT3 receptor antagonist tropisetron immediately prior to aversion conditioning with cocaine. As described, cocaine induced dose-dependent aversions that were not significantly affected by pretreatment with tropisetron. The failure of tropisetron to impact aversions induced by cocaine may be a function of a number of factors including the dose administered during pretreatment as well as the pretreatment interval. However, as noted above, Higgins and his colleagues have reported that tropisetron did attenuate place aversions induced by the 5HT3 agonist PBG at a dose (0.1 mg/kg) and a pretreatment time comparable (30 min) to those used in the present assessment (see Higgins et al., 1993). Its failure to affect cocaine in the CTA preparation is unlikely a function of these specific parametric conditions.

That tropisetron did not attenuate cocaine-induced aversions suggests instead that the 5HT3 receptor subtype does not mediate the aversive effects of cocaine. Although the 5-HT3 receptor subtype may play no role in cocaine-induced aversions, several other reports support a role for 5-HT in general in cocaine’s aversive effects. As previously described, Sora and colleagues reported KO mice with a SERT deletion displayed an increase in cocaine-induced conditioned place preferences (Sora et al., 1998), an effect interpreted as being a function of the reduction in cocaine’s aversive effects normally mediated by 5-HT (see Uhl et al., 2002 for a summary of the relative roles and interactions of DA, 5-HT and NE in the rewarding and aversive effects of cocaine). This interpretation is supported in part by the fact that KO mice with the SERT deletion display attenuated cocaine-induced CTAs relative to wild-type (Jones et al., 2010). Consistent with these findings, Serafine and Riley (2010) have recently reported that preexposure to cocaine significantly attenuated aversions induced by fluoxetine, suggesting some adaptation or tolerance to their common aversive effects. Interestingly, preexposure to fluoxetine had no effect on cocaine-induced aversions, suggesting that although the two drugs share aversive stimulus properties (enhanced 5-HT levels by SERT inhibition through both cocaine and fluoxetine administration), these effects are not identical (Serafine and Riley, 2010). The fact that 5-HT in general appears to be involved in cocaine’s aversive effects, whereas 5-HT3 receptor antagonism was without effect may simply argue that other 5-HT receptor subtypes may be involved.

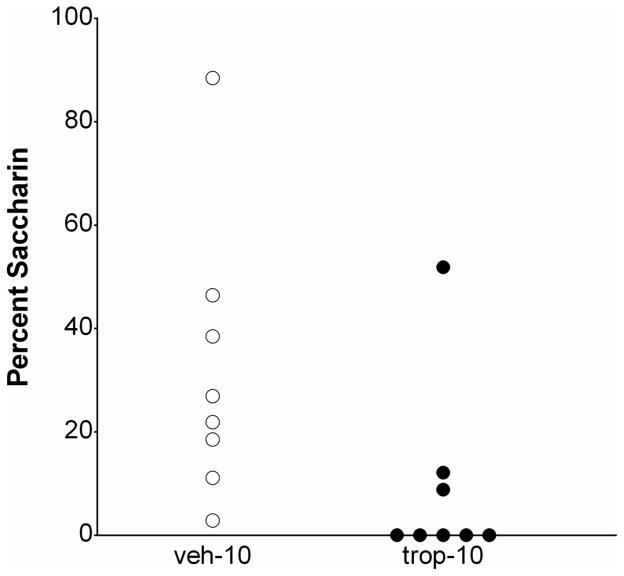

Although tropisetron had no antagonist effect on cocaine-induced aversions, aversions induced by the low dose of cocaine (10 mg/kg) appeared potentiated (both during the acquisition of the aversion as well as on the two-bottle test). For example, on the two-bottle test five of the eight subjects in the tropisetron-pretreated group drank 0 ml of saccharin, whereas none of the vehicle pretreated animals displayed this level of near complete suppression of consumption (see Figure 5). In fact, seven of the eight tropisetron pretreated subjects drank less than all but two of the animals pretreated with vehicle. The ability of tropisetron to impact aversions induced by cocaine is unlikely a function of the combined aversive effects of tropisetron and cocaine. While in Experiment 1, the high dose of tropisetron (0.56 mg/kg) was aversive as assessed in the two-bottle aversion test, the dose of tropisetron chosen for Experiment 2 (0.18 mg/kg) did not induce an aversion on its own after multiple conditioning trials or in the two-bottle assessment. These results suggest that activity at 5-HT3 receptors might actually limit cocaine’s overall aversive effects and antagonism at these receptors potentiate the aversive effects of cocaine. It is interesting in this context that Higgins and colleagues reported tropisetron attenuated morphine-induced place preference and argued that 5-HT3 antagonism limits morphine reward by potentiating its aversive effects (Higgins et al., 1993), an effect supported by Bienkowski and colleagues who reported that tropisetron (0.1 mg/kg, SC) potentiates morphine-induced taste aversions (Bienkowski et al., 1997).

Figure 5.

Individual consumption of percent saccharin consumption for subjects pretreated with tropisetron (0 or 0.18 mg/kg) and conditioned with cocaine (10 mg/kg).

The finding that 5-HT3 receptor antagonism may potentiate cocaine’s aversive effects parallels recent work with NE and its possible role in cocaine’s aversive effects. For example, while NET KO mice display attenuated aversions (Jones et al., 2010) and preexposure to desipramine weakens (Serafine and Riley, 2009) aversions induced by cocaine, the NE antagonists prazosin and propranolol potentiate cocaine-induced aversions (Freeman et al., 2008). Further, preexposure to cocaine potentiates the aversions induced by the NET inhibitor desipramine (Serafine and Riley, 2009). Both of these findings suggest that under specific conditions NE activity may limit cocaine’s aversive effects (for a review, see Serafine and Riley, In Press).

Although the current experiment provides no evidence that 5-HT3 receptor activation is involved in cocaine’s aversive effects, the role of 5-HT remains unknown. Prior work with cocaine indicates that its aversive effects are complex and multifaceted, mediated primarily by DA and modulated in part by NE and 5-HT activity. Further examination of the brain amines and their receptors will allow for a more comprehensive understanding of the mechanism underlying cocaine’s aversive effects. Given that drug use is thought to be a function of the balance of the rewarding and aversive effects of a drug, understanding these aversive effects and the factors that modulate them may lead to better prevention and treatment of cocaine abuse.

Figure 2.

Mean (± SEM) percent saccharin consumption for subjects conditioned with tropisetron (0.056, 0.18 or 0.56 mg/kg) or vehicle (0 mg/kg). There was a significant effect of Group. *Significantly different from Groups 0, 0.056, 0.18.

Highlights.

Low and intermediate doses of tropisetron failed to induce CTAs.

The high dose of tropisetron induced an aversion, but only on a two-bottle test.

Tropisetron at all doses did not affect food consumption.

Cocaine induced dose-dependent aversions that were unaffected by tropisetron.

The intermediate dose of tropisetron appeared to potentiate cocaine-aversions.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a grant from the Mellon Foundation to ALR and the Mathias Undergraduate Summer Research Award and American University’s Scholars and Artists Fellowship to MAB. A portion of this work was supported by the Intramural Research Programs of National Institute on Drug Abuse and National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Batsell WR, Best MR. One bottle too many - method of testing determines the detection of overshadowing and retention of taste-aversions. Anim Learn Behav. 1993;21:154–8. [Google Scholar]

- Bienkowski P, Kuca P, Piasecki J, Kostowski W. 5-ht3 receptor antagonist, tropisetron, does not influence ethanol-induced conditioned taste aversion and conditioned place aversion. Alcohol. 1997;14:63–9. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(96)00108-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R, Tilley MR, Wei H, Zhou F, Zhou FM, Ching S, et al. Abolished cocaine reward in mice with a cocaine-insensitive dopamine transporter. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103:9333–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600905103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham CL, Gremel CM, Groblewski PA. Genetic influences on conditioned taste aversion. New York, New York: Oxford University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- De Beun R, Lohmann A, Schneider R, De Vry J. Comparison of the stimulus properties of ethanol and the ca2+ channel antagonist nimodipine in rats. European journal of pharmacology. 1996;306:5–13. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(96)00198-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ettenberg A. Opponent process properties of self-administered cocaine. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews. 2004;27:721–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2003.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari CM, O’Connor DA, Riley AL. Cocaine-induced taste aversions: Effect of route of administration. Pharmacology, biochemistry, and behavior. 1991;38:267–71. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(91)90277-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman KB, Rice KC, Riley AL. Assessment of monoamine transporter inhibition in the mediation of cocaine-induced conditioned taste aversion. Pharmacology, biochemistry, and behavior. 2005;82:583–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2005.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman KB, Verendeev A, Riley AL. Noradrenergic antagonism enhances the conditioned aversive effects of cocaine. Pharmacology, biochemistry, and behavior. 2008;88:523–32. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2007.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gommans J, Bouwknecht JA, Hijzen TH, Berendsen HH, Broekkamp CL, Maes RA, et al. Stimulus properties of fluvoxamine in a conditioned taste aversion procedure. Psychopharmacology. 1998;140:496–502. doi: 10.1007/s002130050794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goudie AJ, Dickins DW, Thornton EW. Cocaine-induced conditioned taste aversions in rats. Pharmacology, biochemistry, and behavior. 1978;8:757–61. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(78)90279-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison AA, Markou A. Serotonergic manipulations both potentiate and reduce brain stimulation reward in rats: Involvement of serotonin-1a receptors. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics. 2001;297:316–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes DJ, Greenshaw AJ. 5-HT receptors and reward-related behaviour: A review. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews. 2011;35:1419–49. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrie CA. The 5ht3 antagonist gr38032f is highly toxic in dba/2 mice. Psychopharmacology. 1990;101:429–30. doi: 10.1007/BF02244065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins GA, Joharchi N, Sellers EM. Behavioral effects of the 5-hydroxytryptamine3 receptor agonists 1-phenylbiguanide and m-chlorophenylbiguanide in rats. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics. 1993;264:1440–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt T, Amit Z. Conditioned taste aversion induced by self-administered drugs: Paradox revisited. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews. 1987;11:107–30. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(87)80005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt T, Switzman L, Amit Z. Involvement of dopamine in the aversive stimulus properties of cocaine in rats. Pharmacology, biochemistry, and behavior. 1985;22:945–8. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(85)90300-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones JD, Hall FS, Uhl GR, Riley AL. Dopamine, norepinephrine and serotonin transporter gene deletions differentially alter cocaine-induced taste aversion. Pharmacology, biochemistry, and behavior. 2010;94:580–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2009.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kankaanpaa A, Meririnne E, Seppala T. 5-HT3 receptor antagonist mdl 72222 attenuates cocaine- and mazindol-, but not methylphenidate-induced neurochemical and behavioral effects in the rat. Psychopharmacology. 2002;159:341–50. doi: 10.1007/s00213-001-0939-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly SP, Hodge CW. The 5-HT3 antagonist Y-25130 blocks cocaine-induced lowering of ICSS reward thresholds in the rat. Pharmacology, biochemistry, and behavior. 2003;74:297–302. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(02)00985-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohut S, Riley AL. Conditioned taste aversions. In: Stolerman I, editor. Encyclopedia of psychopharmacology. Springer Verlag; 2010. pp. 336–40. [Google Scholar]

- Kosten TA, Miserendino MJ, Haile CN, DeCaprio JL, Jatlow PI, Nestler EJ. Acquisition and maintenance of intravenous cocaine self-administration in lewis and fischer inbred rat strains. Brain research. 1997;778:418–29. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)01205-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller CP, Huston JP. Determining the region-specific contributions of 5-HT receptors to the psychostimulant effects of cocaine. Trends in pharmacological sciences. 2006;27:105–12. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomikos GG, Spyraki C. Cocaine-induced place conditioning: Importance of route of administration and other procedural variables. Psychopharmacology. 1988;94:119–25. doi: 10.1007/BF00735892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons LH, Weiss F, Koob GF. Serotonin1b receptor stimulation enhances cocaine reinforcement. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 1998;18:10078–89. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-23-10078.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley AL. The paradox of drug taking: The role of the aversive effects of drugs. Physiology & behavior. 2011;103:69–78. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2010.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley AL, Davis C, Roma P. Strain differences in taste aversion learning: Implications for animal models of drug abuse. New York, New York: Oxford University Press; 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritz MC, Lamb RJ, Goldberg SR, Kuhar MJ. Cocaine receptors on dopamine transporters are related to self-administration of cocaine. Science. 1987;237:1219–23. doi: 10.1126/science.2820058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha BA, Fumagalli F, Gainetdinov RR, Jones SR, Ator R, Giros B, et al. Cocaine self-administration in dopamine-transporter knockout mice. Nature neuroscience. 1998;1:132–7. doi: 10.1038/381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serafine KM, Briscione MA, Rice KC, Riley AL. Dopamine mediates cocaine-induced conditioned taste aversions as demonstrated with cross-drug preexposure to gbr 12909. Pharmacology, biochemistry, and behavior. 2012a;102:269–74. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2012.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serafine KM, Briscione MA, Riley AL. The effects of haloperidol on cocaine-induced conditioned taste aversions. Physiology & behavior. 2012b;105:1161–7. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serafine KM, Riley AL. Possible role of norepinephrine in cocaine-induced conditioned taste aversions. Pharmacology, biochemistry, and behavior. 2009;92:111–6. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serafine KM, Riley AL. Preexposure to cocaine attenuates aversions induced by both cocaine and fluoxetine: Implications for the basis of cocaine-induced conditioned taste aversions. Pharmacology, biochemistry, and behavior. 2010;95:230–4. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2010.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serafine KM, Riley AL. In: Serotonin: Biosynthesis, regulation and health implications. Hall FS, editor. 400 Oser Ave Suite 1600 Hauppauge NY 11788–3619 United States of America: Nova Science Publishers, Inc; In Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sora I, Hall FS, Andrews AM, Itokawa M, Li XF, Wei HB, et al. Molecular mechanisms of cocaine reward: Combined dopamine and serotonin transporter knockouts eliminate cocaine place preference. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98:5300–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091039298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sora I, Wichems C, Takahashi N, Li XF, Zeng Z, Revay R, et al. Cocaine reward models: Conditioned place preference can be established in dopamine- and in serotonin-transporter knockout mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95:7699–704. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spector AC, Smith JC, Hollander GR. A comparison of dependent measures used to quantify radiation-induced taste aversion. Physiology & behavior. 1981;27:887–901. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(81)90059-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T, Shiozaki Y, Masukawa Y, Misawa M. 5-HT3 receptor antagonists block cocaine- and methamphetamine-induced place preference. Yaku- butsu Seishin Kodo. 1992;12:33–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhl GR, Hall FS, Sora I. Cocaine, reward, movement and monoamine transporters. Molecular Psychiatry. 2002;7:21–26. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise RA, Bauco P, Carlezon WA, Jr, Trojniar W. Self-stimulation and drug reward mechanisms. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1992;654:192–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb25967.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]