Abstract

The stromal-specific proteoglycan decorin has emerged in recent years as a critical regulator of tumor initiation and progression. Decorin regulates the biology of various types of cancer by modulating the activity of several tyrosine-kinase receptors coordinating growth, survival, migration, and angiogenesis. Decorin binds to surface receptors for the epidermal and hepatocyte growth factors (EGF and HGF) with high affinity and negatively regulates their activity and signaling via robust internalization and eventual degradation. The insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) system plays a critical role in the regulation of cell growth both in vivo and in vitro. The IGF-I receptor (IGF-IR) is also essential for cellular transformation due to its ability to enhance cell proliferation and protect cancer cells from apoptosis. Recent data have pointed out a role of decorin in regulating the IGF-I system in both non-transformed and transformed cells. Significantly, there is a surprising dichotomy in the mechanisms of decorin action on IGF-IR signaling, which considerably differs between physiological and pathological cellular models. In this review, we summarize the current knowledge on decorin regulation of the IGF-I system in normal and transformed cells, and discuss possible decorin-based therapeutic approaches to target IGF-IR-driven tumors.

Keywords: decorin, IGF-IR, signaling, bladder cancer, cancer growth

Introduction

Decorin, the prototypical member of the small leucine-rich proteoglycans (SLRP) gene superfamily [1,2], is a chondroitin/dermatan sulfate proteoglycan synthesized by stromal fibroblasts, stressed vascular endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells [3]. The decorin protein core is encoded by a relatively large and complex gene [4,5], and has been found to regulate many diverse physiological processes since the original characterization as a regulator of collagen fibrillogenesis [6-10]. These processes include regulation of bone and tendon pathophysiology, innate immunity, hypersensitivity reactions, diabetic nephropathy, angiogenesis and hepatic fibrosis [11-24]. For the most part, soluble decorin acts as a monomer in solution [25] and most of its biological functions are mediated by the leucine-rich protein core, although the single glycosaminoglycan chain, either dermatan or chondroitin sulfate, may also play physiological roles [26-28]. Soluble decorin modulates the biology of various types of cancer by down-regulating the activity of several tyrosine-kinase receptors (RTKs) critical for malignant cell growth and survival [29-32]. Decorin binds EGFR [33,34] and the Met receptor [30] with high affinity at an empirically determined Kd of 80 nM and 2 nM, respectively. This interaction leads to physical down-regulation of both RTK activity exclusively within caveolin-1-positive endosomes and followed by subsequent degradation via lysosomes [35,36]. This mode of internalization is in stark contrast to agonist binding to cognate receptors, which directly promotes receptor recycling to the plasma membrane, as mediated by clathrin, for additional rounds of signaling. However, even agonist binding can lead to partial internalization and lysosomal degradation. Therefore, the first linkage of decorin to tumorigenesis came from the finding of increased deposits of decorin within the stroma of human colon carcinomas [37]. Definitive evidence of decorin in cancer progression was obtained from the analyses of decorin-null mice where ~30% of these mice develop spontaneous intestinal tumors [38,39]. Remarkably, mice lacking both decorin and p53 show a faster rate of tumor development and succumb to a very aggressive form of thymic lymphomas, indicating that lack of decorin is permissive for lymphomagenesis [40]. Therefore, strong biochemical and genetic evidence reveal a tumor repressive role for decorin to act as a soluble pan-RTK inhibitor to stunt tumorigenic growth and inhibit cancer cell invasion and metastasis [41-45]. Indeed, the anti-oncogenic role for decorin has been well documented in various experimental models [2,46], including colon [47,48], breast [49] and ovarian [50] carcinoma cells, syngeneic rat gliomas [51], and squamous and colon carcinoma xenografts [43,52,53].

The possible mechanism of action has been described previously and occurs, paradoxically, via a transient activation of the EGFR and the Met receptor [36,42,54-56] to achieve suppression of tumorigenic growth [35,57]. Decorin, via binding to EGFR and Met, suppresses GSK3β inactivation and induces a non-canonical, GSK3β-independent pathway of β-catenin suppression coincident with increased phosphorylation of Myc at Thr58, a known phospho-acceptor residue that controls Myc stability [58]. This ultimately leads to 26S proteasome-mediated degradation of both oncoproteins, as well as elaborating a mechanism for p21 induction via Myc degradation leading to a repression of this particular locus. Moreover, decorin is able to suppress HIF-1α and VEGFA expression under normoxic conditions to subvert tumor angiogenesis, presumably before the angiogenic switch occurs [59]. Further proof-of-principle for decorin as a tumor repressor came from studies utilizing adenovirus-mediated or systemic delivery of decorin to prevent metastases in an orthotopic breast carcinoma xenograft model [43,45]. Finally, systemic delivery of decorin retards the growth of prostate cancer in a mouse model of prostate carcinogenesis [60] and inhibits metastasis formation in various breast tumor models [44,61,62].

The role of systemically administered decorin to suppress tumorigenesis was given a completely novel perspective following a pre-clinical high-resolution global gene expression analysis of a triple-negative orthotopic breast carcinoma xenograft model. This view was supported by the exclusive differential modulation found in the tumor microenvironment transcriptome without any significant changes in gene expression occurring within the tumor proper. Decorin protein core profoundly inhibited a subset of genes necessary to orchestrate an immunomodulatory response (such as Irg1, ligp, Mrgpra2, Il1b) while simultaneously inducing expression of tumor suppressor genes and cell adhesion molecules (Peg3, Cadm1) [63]. Crosstalk between decorin and the IGF-IR system in modulating and forming part of this gene signature gives plausibility that a subset of the profiled genes in the ontological categories of cytoskeletal and cell cycle regulation are a function of decorin bioactivity via IGF-IR. The importance of this possibility is underscored by the confirmed identification of activated IGF-IR in the progression of many diverse neoplastic states such as in breast, lung, liver, colon, prostate, and pancreas [64]. Therefore, the ability of decorin to repress downstream IGF-IR signaling may be of paramount importance in the progression of these tumor types.

Collectively, this plethora of in vitro and in vivo data detail a function for decorin as a soluble tumor repressor capable of attenuating, in a protracted fashion, receptor tyrosine kinases localized on the cell surface of tumor cells through concurrent induction of several cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors and repression of potent oncogenes. Further, the intricacies of decorin-evoked suppression of tumor growth appears to be much more complex than previously predicted due to the profound cadence of gene expression changes occurring within the tumor microenvironment following systemic treatment.

The IGF-I system

The insulin-like growth factor (IGF-I) system includes six binding proteins, three ligands, IGF-I, IGF-II and insulin, and three major receptors, the insulin-like growth factor receptor I (IGF-IR), the insulin receptor (IR) and the insulin-like growth factor receptor 2 (IGF-IIR) [65]. Extensive homology exists between IR and IGF-IR, varying from 45-65% with highly conserved regions within the tyrosine-kinase cassette and substrate binding domain, where homology is upwards of 60-80% [66]. Expression of IR and IGF components is widespread throughout the body and is driven by a variety of stimuli under normal physiological conditions including proper nutrition and exercise [65,66]. Further complexity arises from promiscuous hybrid receptor formation with up to six different species of receptor homo- or hetero-hybrids that inherently display varying affinities for ligands, as well as condition-specific splicing events: IR-A and IR-B differ by excluding or including exon 11 [65,67].

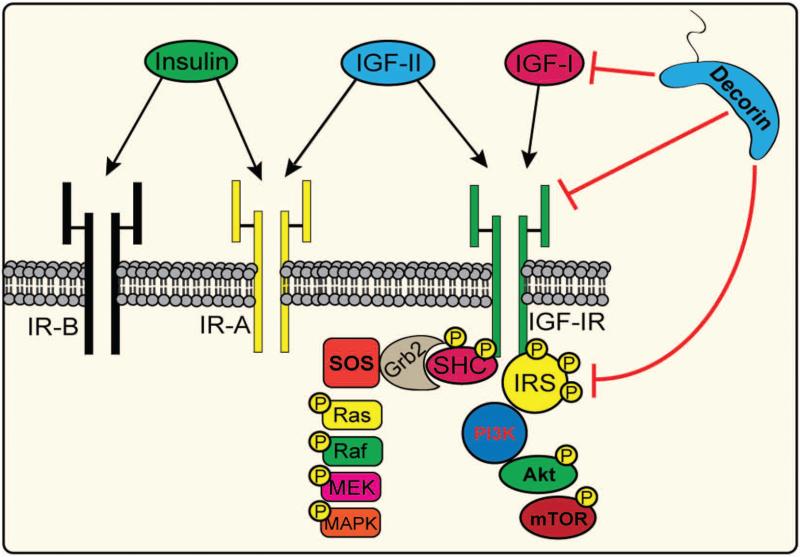

The IGF-IR is a hetero-tetrameric (α2β2) transmembrane glycoprotein with tyrosine kinase activity, that shares high similarity with other IR family members, except for IGF-IIR [66] Structural features of IGF-IR ectodomain include two extra-cellular α subunits harboring the ligand-binding site, and two β subunits which have a short extra-cellular portion, a trans-membrane and a cytoplasmic region (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the IGF-I system. The IGF-I system includes 6 binding proteins, three ligands and three major receptors. The IGF-IIR has no kinase activity and functions as a cellular “sink” to titrate IGF-II levels in the plasma. The alternatively-spliced IR genes, which gives rise to IR-B and IR-A, is critical for tissue glucose homeostasis while the IGF-IR is essential for cell proliferation. In neoplastic conditions, decorin binds IGF-I and IGF-IR to indirectly or directly, respectively, inhibit downstream signaling to IRS-1 and therefore stifle MAPK and PI3K coordinated pathways.

The IGF-IR plays an essential role in cell growth in vitro and in vivo Mice homozygous for a targeted disruption of the insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (IGF-IR) gene exhibit severe growth retardation, being only 45 % the size of wild-type littermates, and die shortly after birth due to respiratory failure [68,69]. Significantly, fibroblasts derived from IGF-IR knock-out mice cells (R-cells) [70] are refractory to transformation induced by a variety of cellular oncogenes, including c-Src, the bovine papilloma virus, the EGFR and the PDGFR and several tumorigenic agents but fully transformed when the IGF-IR is re-expressed [71,72]. It is important to note that activating mutations leading to ligand-independent IGF-IR receptor signaling are relatively rare [65]. Indeed, the transformative properties of IGF-IR derives from aberrant expression [66,67] as confirmed by reintroduction of IGF-IR into IGF-IR null mouse fibroblast cells (known as R-cells) leading to oncogenic transformation [73] in response to a variety of classical oncogenes. However, anomalous expression of the receptors themselves is not the only culprit in transformative events as the various biological ligands, including insulin and IGF-I, have also been implicated in tumorigenesis [71]

In vitro experiments on tumor cells and epidemiological studies have confirmed that activation of the IGF-IR is involved in the development of many neoplastic diseases, including carcinomas of the lungs, prostate, pancreas, liver, colon and breast [65,67,73,74]. The transforming capability of the IGF-IR most likely depends on its ability to sustain cell proliferation, protect cancer cells from apoptosis and enhance migration and invasion [71].

The insulin receptor (IR) is expressed in two isoforms: the IR isoform A (IR-A) and isoform B (IR-B). The IR-A is predominantly expressed in fetal tissues and cancer cells whereas the IR-B is preferentially expressed in differentiated insulin-responsive tissues and cells [66]. While the IR-B binds insulin with high affinity, the IR-A has high affinity for insulin but also binds IGF-II, although the affinity is 3 to 10-fold lower than that for insulin. Instead, IGF-II binds to IGF-IR and to IR-A with similar affinities and shares with the homolog ligand IGF-I mitogenic and anti-apoptotic effects [66]. While the role of the IR-B in the regulation of metabolic effects has been known for several years, there is more recent evidence suggesting that the IR, and in particular the IR-A, may also be involved in the pathogenesis of cancer [72]. Several studies have now established that IGF-II elicits biological effects via activation of the IR-A [72,75,76]. Predominant expression of the IR-A over the IR-B has been detected in several cancer models and an autocrine proliferative loop between IGF-II and the IR-A has been demonstrated in malignant thyroid and breast cancer cells [67].

It has been recently shown that insulin and IGF-II have inherently different mechanisms for the internalization of the IR-A receptor following ligand binding [77]. These mechanisms determine differences in the signaling capacity of the receptor, based on the relative binding affinities of the ligands. For example, IGF-II promotes slower kinetics of Akt-mediated phosphorylation of IRS-1 at Ser307, which is necessary for IRS-1 degradation when compared to insulin [77].

Decorin regulation of the IGF-I system in normal cells

The first evidence for a physiological role of decorin in the regulation of IGF-IR signaling was provided by Schönherr et al. [78] who demonstrated through co-immunoprecipitation experiments that decorin binds the IGF-IR on an immortalized endothelial cell line with an affinity in the nanomolar range (Kd = 18 nM) comparable to IGF-I. In addition, decorin binds IGF-I itself (Fig. 1), although the affinity is lower (Kd= 190 nM) than canonical IGF-I-binding proteins [78]. Decorin binding to the IGF-IR in endothelial cells promotes receptor phosphorylation at levels comparable to IGF-I and subsequent activation of downstream signaling proteins, as measured by IGF-IR-dependent Akt phosphorylation [78]. Notably, decorin does not interfere with IGF-I, as simultaneous incubation of endothelial cells with decorin and IGF-I does not alter IGF-IR phosphorylation and Akt activation when compared to the addition of a single ligand [78]. Significantly, adenoviral-mediated decorin expression induces sustained IGF-IR downregulation, thereby suggesting that decorin may be critical in the regulation of IGF-IR stability in endothelial cells [78]. It was further established that decorin protein core is sufficient for IGF-IR signaling in endothelial cells and the N-terminus of the protein is the IGF-IR binding region [78].

The physiological relevance of the decorin/IGF-IR interaction was confirmed in two animal models, such as inflammatory angiogenesis in the cornea and unilateral ureteral obstruction, where the IGF-IR was upregulated in decorin-deficient mice compared to controls. However, this mechanism could not compensate for decorin-deficiency in both animal models suggesting that decorin and IGF-IR may work in concert to regulate signaling in endothelial cells [78]. Subsequent studies have corroborated the role of decorin in modulating IGF-IR signaling in several physiological cell models, including fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and various malignant cell types such as the urothelial carcinoma lines 5637 and T24, triple negative breast carcinoma cells, MDA-MB-231, and squamous carcinoma cells, HeLa [64].

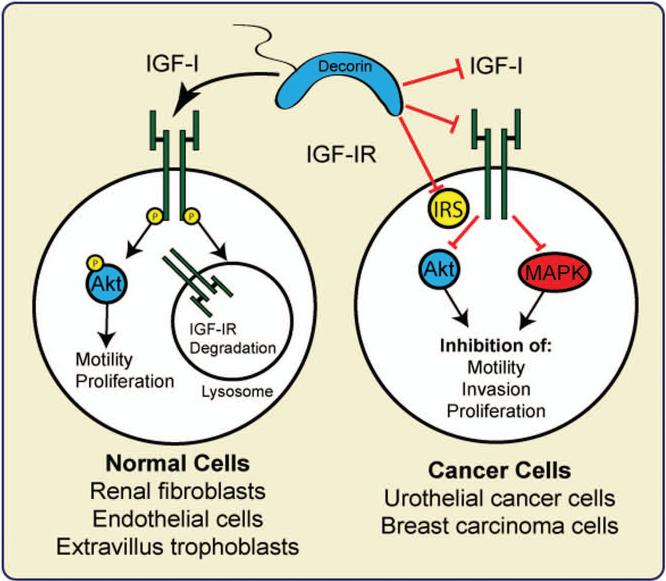

Decorin promotes endothelial cell adhesion and migration on fibrillar collagen by triggering Rac activation in an IGF-IR-dependent fashion [79]. Additionally, decorin modulates α2β1 integrin biological responses in a transformed endothelial cell line likely through the IGF-IR [79]. The acute regulation of decorin via IGF-IR on endothelial cells might be due, in part, to the finding that these particular cells express several fold higher levels of IGF-IR (at both the mRNA and protein levels) and that most of the IR-A was found to be sequestered within hybrid receptors [80]. This phenomenon is not confined only to endothelial cells, as decorin is also critical in regulating IGF-IR activation and biological output in renal fibroblasts, specialized extravillous trophoblastic cells, and renal tubular epithelial cells. In renal fibroblasts decorin promotes IGF-IR activation and regulates the synthesis of the elastic fiber component fibrillin-1 through activation of the IGF-IR/mTOR/p70S6K signaling cascade [81]. The IGF-IR is overexpressed in diabetic kidneys from Dcn−/− compared to Dcn+/+ mice but IGF-IR upregulation could not compensate for decorin deficiency resulting in reduced fibrillin-1 levels [81]. This illustrates a cooperative function for both decorin and IGF-IR, via genetic models, to initiate and maintain physiological levels of fibrillin-1. In contrast, in the placenta extravillus trophoblasts, soluble decorin inhibits migration by promoting IGF-IR phosphorylation and activation in a dose-dependent manner but the anti-proliferative action of decorin is IGF-IR-independent and likely mediated either through the EGFR [82] or VEGFR2, as decorin is able to bind VEGFR2 with affinity and suppress ERK1/2 mediated signaling downstream of this receptor [83]. Collectively, these results suggest that in normal cells, decorin mimics the action of the IGF-I ligand and therefore functions as an IGF-IR agonist. The decorin/IGF-IR interaction positively regulates receptor phosphorylation and downstream signaling to achieve specific biological functions in non-transformed cells (Fig. 2). Seemingly diametric to the situation seen in the above two examples, loss of decorin in diabetic mice promotes an increase in IGF-IR levels and apoptosis with aberrant deposition of extracellular matrix [14]. Intriguingly, restoration of decorin abrogates, via IGF-IR, high glucose induced apoptosis and evokes a protective response against diabetic nephropathy [14].

Fig. 2.

The dichotomy of decorin action on the IGF-I system. In normal cells decorin promotes IGF-IR phosphorylation and activation of downstream signaling, which is followed by receptor degradation. In cancer cells instead decorin inhibits ligand-induced IGF-IR activation and negatively regulates IGFIR-downstream signaling but do not affect receptor stability.

Decorin action on the IGF-IR in neoplasia

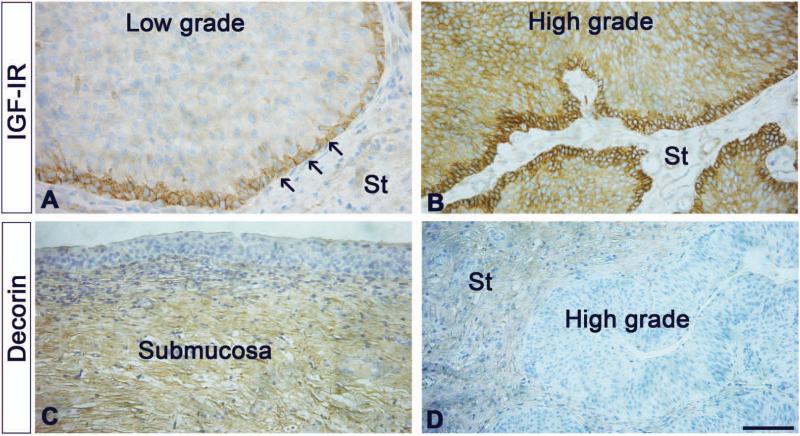

All of the aforementioned studies were performed with “normal, non-malignant” cells. Thus, until recently, there were no published data on a possible role of decorin in modulating cancer growth via the IGF-IR in transformed cells or in tumor models. To establish whether decorin may regulate IGF-IR function in bladder cancer, we analyzed decorin expression in different publicly-available bladder cancer microarray studies using the Oncomine database. Notably, in two independent data sets [84,85], there was a marked (3.5 to 13 fold) decrease of decorin mRNA levels in primary bladder cancers as compared to normal counterparts [64]. The IGF-IR and decorin show a differential expression in bladder cancer. The IGF-IR is specifically expressed by the basal urothelium in low-grade bladder cancer (arrows, Fig. 3A) and is markedly increased and extended to the full-thickness of the tumors in high-grade bladder cancers (Fig. 3B), without any appreciable stromal expression. In contrast, decorin is expressed primarily in the submucosal stroma of the urinary bladder (Fig. 3C) and its expression is clearly attenuated in the stroma of high-grade bladder cancers (Fig. 3D). It would be conceivable that increased IGF-IR activity and or expression might be causative for decreased decorin expression, i.e. via hypermethylation of the decorin promoter as found in colon carcinoma [31], within urothelial neoplasia. Moreover, the IGF-IR acts as a “scatter factor” in urothelial cancer cells markedly enhancing cell motility and invasion without affecting cell proliferation [86]. These effects require the activation of the Akt and MAPK pathways as IGF-I induces Akt- and MAPK-dependent phosphorylation of paxillin [86]. Interestingly, proline-rich tyrosine-kinase 2 (Pyk2), is potently activated by IGF-I and is required for the invasive phenotype of urothelial carcinoma cells [87]. Whether decorin attenuates Pyk2 activity in these cells and in vivo is not known, but it could be an additional mechanism for the cross-talk between soluble matrix constituents such SLRPs and RTK signaling. Collectively, these results support the hypothesis that the IGF-IR may play a critical role in the establishment of the invasive phenotype in urothelial neoplasia, a process affected by stroma-derived decorin.

Fig. 3.

IGF-IR and decorin show a differential expression in bladder cancer. (A-D) Gallery of immunohistochemical images of low- and high-grade bladder cancer samples stained with antibodies specific for IGF-IR (A,B) or decorin (C,D). Notice that the IGF-IR is specifically expressed by the basal urothelium (arrows, A), but is markedly increased and extended to the full-thickness of the tumor in high-grade bladder cancer (B), with no stromal (St) expression. In contrast decorin is expressed primarily in the submucosal stroma of the urinary bladder (C) and its expression is markedly reduced in the stroma of high-grade bladder cancers. Bar = 200 μm.

We further found that decorin protein core can bind with high affinity to both the IGF-IR and its natural ligand IGF-I, and we also established that decorin binds the IGF-IR in a region that does not overlap with the canonical binding site for IGF-I [64]. It is important to convey that we found no discernable changes between decorin proteoglycan or protein core in binding to either IGF-I or IGF-IR. The binding affinities obtained were comparable between these two protein species [64]. However, distinct differences possibly solicited by the glycanated form versus protein core on downstream IGF-IR signaling events have not yet been established. Significantly, decorin stimulation of urothelial cancer cells has no effect on IGF-IR phosphorylation but instead severely decreases ligand-dependent IGF-IR activation levels in a dose-dependent manner [64]. In addition, prolonged exposure to decorin does not affect the stability of the IGF-IR in urothelial cancer cells either alone or in the presence of IGF-I. In the context of potential decorin based therapeutics to temper IGF-IR signaling in neoplasia, this effect will be of considerable importance as downregulation of IGF-IR promotes increased IR-A homodimer formation and thus cancer cells with enhanced IGF-II/IR-A signaling capacities. This has been verified in several in vitro models and confirmed with an IGF-IR knockout osteoblast cell line [66]. As decorin does not affect stability of the IGF-IR, for reasons discussed below, the increase in IR-A homodimers should be prevented and thus IGF-IR treatments based on decorin will circumvent this unwanted resistance of IGF-IR [66]. Hybrid receptor composition analysis will need to be performed to substantiate this claim following decorin treatment.

These experiments interestingly suggest that decorin affects IGF-IR function in bladder cancer in a manner that is substantially different from its known activity on the IGF-IR in endothelial cells (or other non-malignant cells) where decorin promotes IGF-IR activation followed by receptor degradation [88]. In addition, decorin action substantially differs from its known activity on EGFR and Met where decorin leads to a physical downregulation of these two RTKs via caveolin-mediated endocytosis [3]. In urothelial cancer cells, decorin alone does not induce colocalization between the IGF-IR and caveolin-1, in contrast to the colocalization that is readily detectable following IGF-I stimulation [64]. Significantly, decorin stimulation considerably reduces IGF-I-induced IGF-IR and caveolin-1 colocalization, suggesting that decorin may affect either IGF-IR internalization or divert the receptor into a different endocytic compartment. Previous experiments in human skin fibroblasts have indicated that pharmacological inhibition of the IGF-IR does not affect decorin uptake suggesting that decorin endocytosis may not use the IGF-IR as cargo to internalize from the cell surface [89]. Thus it seems that decorin bioactivity focuses on suppressing ligand-induced IGF-IR phosphorylation but not receptor levels and may suggest a function for decorin at the cell membrane in our bladder cancer cell system [64]. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that decorin may play a role in regulating the early stage of IGF-IR internalization from the cell surface but not in modulating IGF-IR sorting into the lysosomal degradative compartment.

It is important to mention that the inability of decorin to affect IGF-IR levels is not limited to urothelial cancer cells (more specifically 5637 and T24 cell lines), as in fact the same results were reproducible in the triple-negative basal breast carcinoma cell line, MDA-MB-231 as well as in cervical squamous carcinoma HeLa cells insofar as total IGF-IR was unchanged but activation by IGF-I was significantly attenuated by decorin [64]. While decorin affect IGF-IR levels in normal cells [41], it has not been previously established whether decorin could affect the IGF-IR axis by additionally regulating the stability/activation of downstream signaling effectors.

The docking protein insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS-1) is one of the major downstream effectors of the IGF-IR signaling pathway: IRS-1 upon ligand stimulation is recruited to the IGF-IR and regulates the activation of the PI3K and Akt pathways [66]. Thus, IRS-1 function is critical for IGF-IR-dependent biological effects, including cell proliferation and transformation. Accordingly, we determined IRS-1 protein levels after prolonged exposure to IGF-I and/or decorin, and demonstrated that chronic IGF-I stimulation promotes IRS-1 degradation in urothelial cancer cells [64]. Significantly, while decorin enhances IRS-1 degradation, it has no effect in regulating the stability of either IRS-2 or Shc proteins, two other critical components of the IGF-IR signaling pathway. Collectively, these results provide the first evidence for a role of decorin in regulating ligand-dependent stability of IRS-1 and put forward a novel hypothesis that decorin may regulate IGF-IR-dependent biological responses not only by directly affecting receptor activation but also by modulating the stability of downstream signaling proteins.

However, the mechanism through which decorin affects IRS-1 stability is currently unknown. Because decorin alone has no effect on IRS-1 stability, we can exclude that IRS-1 stability may be affected indirectly by decorin acting on other RTKs. One possible mechanism suggests that decorin might suppress total IRS-1 levels insofar as that IGF-I and insulin-induced IRS-1 downregulation is modulated by serine-phosphorylation of IRS-1 residues. We can therefore reasonably make the hypothesis that decorin, by reducing IGF-IR activation, similar to small molecule inhibitors targeted against IGF-IR such as picropodophyllin [66], may negatively regulate IRS-1 tyrosine-phosphorylation, thus increasing the fraction of serine-phosphorylated IRS-1 and enhancing IGF-I-mediated IRS-1 degradation. Importantly decorin functions similarly to insulin insofar as that upon binding to IGF-IR, IRS-1 stability is adversely affected, but not IRS-2. Furthermore, decorin also shares functional similarity to IGF-II by not inducing a physical internalization of the receptor, in contrast to insulin. Endocytosis seems to be crucial in regulating downstream signaling events upon ligand binding [77]. Therefore, it is possible that decorin is able to delay IGF-IR kinetics in a similar fashion to IGF-II but still trigger IRS-1 degradation. This might be a function of differences in the topology of the ubiquitin attachments by Grb10/Nedd4 [90] and/or differential phosphorylation patterns. Tandem mass spectrometry analyzing post-translational modifications of the IGF-IR should aid in this determination and could be correlated with ubiquitin attachment and the determined ligand affinity constants.

Once established that decorin negatively regulates ligand-induced IGF-IR activation concurrent with enhanced IRS-1 degradation, we then demonstrated that decorin severely inhibits IGF-I-stimulated activation of Akt and MAPK [64], the two major pathways critical for IGF-IR-dependent motility and invasion in urothelial cancer cells [86]. Notably, decorin alone has no effect on the activation of these signaling proteins. Finally, we showed that by negatively regulating IGF-IR signaling, decorin severely decreases the ability of urothelial carcinoma-derived cells to migrate and invade in response to IGF-I stimulation.

Collectively, these results suggest that decorin action on IGF-IR activation strongly affects downstream signaling, thereby negatively regulating IGF-I-dependent biological events in bladder cancer cells and potentially other types of cancer cell types. Furthermore, emerging evidence indicates that over-activation of the IGF-IR is able to directly regulate resistance to inhibitors of EGFR signaling as well [67]. Therefore, utilization of decorin to quell IGF-IR activation should preclude gained EGFR resistance, further strengthening the role of decorin as a true pan-RTK inhibitor to stunt cancer growth.

Concluding remarks

Altogether, the data available in the literature point out a unique dichotomy in the mechanisms of decorin action on the IGF-IR system. In normal cells, decorin likely works as an IGF-IR agonist, thereby positively regulating IGF-IR activation and IGF-IR-dependent signaling [88]. On the contrary, in IGF-IR-addicted tumors, decorin functions as a natural IGF-IR antagonist attenuating IGF-IR action. Decorin loss may therefore contribute to IGF-IR-dependent tumor progression. Although there is no literature on the role of other SLRPs in modulating the IGF-I system, the possibility of functional redundancy does exists, especially within class I SLRPs.

The IGF-IR has become an attractive target for cancer therapy and results from early phase clinical trials using anti-IGF-IR antibodies reported encouraging results, although initial results from Phase III clinical trials with anti-IGF-IR antibodies have been so far disappointing [65]. The gap between the promising in vitro results and the unsatisfactory clinical results might be explained by several factors including tumor heterogeneity, resistance mechanisms and ligand/receptor switches. For example, in Ewing’s sarcomas a key resistance mechanism to inhibitors of the IGF-IR is mediated by enhanced homodimerization of the IR-A and concurrent with increased IGF-II production. Resistant cells can convert from IGF-I/IGF-IR to IGF-II/IR-A dependency thereby maintaining sustained activation of Akt and ERK1/2 signaling [71].

The concept that decorin is able to inactivate IGF-IR signaling and destabilize downstream effectors without compromising the stability of the receptor itself should prevent some of the resistance gained (as discussed above) from previous treatment regimens and clinical trials. Furthermore, strong autocrine loops exist between ligand production and receptor activation. Therefore, decorin binding to and potentially sequestering IGF-I (in a manner reminiscent of indirectly attenuating TGF-β signaling via sequestration) may pitch decorin into the therapeutic arena as a viable option to combat bladder cancers overexpressing IGF-IR/IGF-I. In the context of IGF-I sequestration, several articles [91,92] have demonstrated that the composition of the glycosaminoglycan chain, particularly that of dermatan sulfate, is instrumental in the dissociation of IGF-I from IGFBPs, such as the IGF-I-IGFBP-5 complex. As decorin harbors a dermatan sulfate GAG chain, it currently remains unknown whether decorin proteoglycan can influence IGFBPs binding IGF-I. In a more general fashion, this is underscored by the lack of any known cytotoxicity or systemic toxicity of decorin on normal cells would thus strongly support the use of decorin-derived peptides as therapeutic approach to target malignant cell in tumors where the IGF-IR may play a critical role. Interestingly, a recent report has linked heparanase activity to augment IGF-IR via ERK1/2 signaling [93]. As decorin is able to attenuate downstream effectors, the possibility does exist that decorin might be able to impair the function and/or expression of heparanase, a potential target for various forms of tumors [94]. This implication would extend far beyond the mitigation of IGF-IR in neoplasia, but also serves as a much broader inhibitory activity insofar as to prevent liberation of heparan sulfate-bound growth factors.

This becomes increasingly more pertinent for the treatment of the IGF-IR signaling axis as this pathway gains resistance by enhanced IR-A signaling. A study has emerged [95] that has dissected and identified specific genetic signatures associated with treatment-sensitive and treatment-resistant in IGF-IR/IGF-I dominant Ewing’s sarcomas. This will potentially aid in further stratification of patients receiving therapies and / or for future decorin-based modalities.

In preliminary experiments, we have found that IGF-IR levels decrease in metastatic bladder cancer cells, which instead overexpress the IR-A isoform. As urothelial carcinoma cells produce IGF-II [96], which also binds to and activates IR-A, it is possible that this growth factor may also activate the IR-A in an autocrine fashion thereby driving tumor progression and metastasis. Whether decorin binds IGF-II and/or the IR-A has not yet been established. Experiments are currently under way to determine decorin activity on IGF-II and IR-A and test the hypothesis that decorin loss in high-grade bladder cancer could contribute to increased IR-A activity especially in the metastatic cells.

In conclusion, decorin regulation of a wide network of RTK signaling plays a critical role in the regulation of many aspects of mammalian biology, in both physiology and disease states. Further understanding the mechanisms of decorin action in cancer cells may open novel therapeutic approaches in malignancies where RTKs activation plays an essential role.

Acknowledgements

This work has been supported in part by the Benjamin Perkins Bladder Cancer (A.M.) Fund and National Institutes of Health Grants RO1 CA164462 (A.M., R.V.I.), and RO1 CA39481, RO1 CA47282 and RO1 CA120975 (R.V.I.).

Abbreviations

- SLRP

small leucine-rich proteoglycan

- IGF-I

insulin-like growth factor I

- IGF-IR

IGF receptor I

- IR

insulin receptor

- RTK

receptor tyrosine kinase

- IRS-1

insulin receptor substrate 1

- MAPK

mitogen activated protein kinase

- EGFR

epidermal growth factor receptor

References

- [1].Iozzo RV, Goldoni S, Berendsen A, Young MF. Small leucine-rich proteoglycans. In: Mecham RP, editor. Extracellular Matrix: An overview. Springer; 2011. pp. 197–231. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Merline R, Nastase MV, Iozzo RV, Schaefer L. Small Leucine-rich proteoglycans: multifunctional signaling effectors. In: Karamanos N, editor. Extracellular Matrix: Pathobiology and signaling. Walter de Gruytier Gmbh and Co.; Berlin: 2012. pp. 185–196. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Neill T, Schaefer L, Iozzo RV. Decorin, a guardian from the matrix. Am J Pathol. 2012;181:380–387. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Danielson KG, Fazzio A, Cohen I, Cannizzaro LA, Eichstetter I, Iozzo RV. The human decorin gene: intron-exon organization, discovery of two alternatively spliced exons in the 5′ untranslated region, and mapping of the gene to chromosome 12q23. Genomics. 1993;15:146–160. doi: 10.1006/geno.1993.1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Santra M, Danielson KG, Iozzo RV. Structural and functional characterization of the human decorin gene promoter. A homopurine-homopyrimidine S1 nuclease-sensitive region is involved in transcriptional control. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:579–587. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Danielson KG, Baribault H, Holmes DF, Graham H, Kadler KE, Iozzo RV. Targeted disruption of decorin leads to abnormal collagen fibril morphology and skin fragility. J Cell Biol. 1997;136:729–743. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.3.729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Kalamajski S, Oldberd Å . The role of small leucine-rich proteoglycans in collagen fibrillogenesis. Matrix Biol. 2010;29:248–253. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Reed CC, Iozzo RV. The role of decorin in collagen fibrillogenesis and skin homeostasis. Glycoconj J. 2002;19:249–255. doi: 10.1023/A:1025383913444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Keene DR, San Antonio JD, Mayne R, McQuillan DJ, Sarris G, Santoro SA, Iozzo RV. Decorin binds near the C terminus of type I collagen. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:21801–21804. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000278200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Zhang G, Ezura Y, Chervoneva I, Robinson PS, Beason DP, Carine ET, Soslowsky LJ, Iozzo RV, Birk DE. Decorin regulates assembly of collagen fibrils and acquisition of biomechanical properties during tendon development. J Cell Biochem. 2006;98:1436–1449. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Robinson PS, Lin TW, Jawad AF, Iozzo RV, Soslowsky LJ. Investigating tendon fascicle structure-function relationship in a transgenic age mouse model using multiple regression models. Ann Biomed Eng. 2004;32:924–931. doi: 10.1023/b:abme.0000032455.78459.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Robinson PS, Huang TF, Kazam E, Iozzo RV, Birk DE, Soslowsky LJ. Influence of decorin and biglycan on mechanical properties of multiple tendons in knockout mice. J Biomechanical Eng. 2005;127:181–185. doi: 10.1115/1.1835363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Merline R, Moreth K, Beckmann J, Nastase MV, Zeng-Brouwers J, Tralhão JG, Lemarchand P, Pfeilschifter J, Schaefer RM, Iozzo RV, Schaefer L. Signaling by the matrix proteoglycan decorin controls inflammation and cancer through PDCD4 and microRNA-21. Sci Signal. 2011;4:ra75. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Merline R, Lazaroski S, Babelova A, Tsalastra-Greul W, Pfeilschifter J, Schluter KD, Gunther A, Iozzo RV, Schaefer RM, Schaefer L. Decorin deficiency in diabetic mice: aggravation of nephropathy due to overexpression of profibrotic factors, enhanced apoptosis and mononuclear cell infiltration. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2009;60(suppl 4):5–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Liang FT, Wang T, Brown EL, Iozzo RV, Fikrig E. Protective niche for Borrelia burgdorferi to evade humoral immunity. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:977–985. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63359-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Moreth K, Iozzo RV, Schaefer L. Small leucine-rich proteoglycans orchestrate receptor crosstalk during inflammation. Cell Cycle. 2012;11:2084–2091. doi: 10.4161/cc.20316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Nikitovic D, Aggelidakis J, Young MF, Iozzo RV, Karamanos NK, Tzanakakis GN. The biology of small leucine-rich proteoglycans in bone pathophysiology. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:33926–33933. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R112.379602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Seidler DG, Mohamed NA, Bocian C, Stadtmann A, Hermann S, Schäfers K, Schäfers M, Iozzo RV, Zarbock A, Götte M. The role for decorin in delayed-type hypersensitivity. J Immunol. 2011;187:6108–6199. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Seidler DG. The galactosaminoglycan-containing decorin and its impact on diseases. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2012;22:578–582. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2012.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Häkkinen L, Strassburger S, Kahari VM, Scott PG, Eichstetter I, Iozzo RV, Larjava H. A role for decorin in the structural organization of periodontal ligament. Lab Invest. 2000;80:1869–1880. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Järveläinen H, Puolakkainen P, Pakkanen S, Brown EL, Höök M, Iozzo RV, Sage H, Wight TN. A role for decorin in cutaneous wound healing and angiogenesis. Wound Rep Reg. 2006;14:443–452. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2006.00150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Schönherr E, Sunderkotter C, Schaefer L, Thanos S, Grässel S, Oldberg Å , Iozzo RV, Young MF, Kresse H. Decorin deficiency leads to impaired angiogenesis in injured mouse cornea. J Vasc Res. 2004;41:499–508. doi: 10.1159/000081806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Williams KJ, Qiu G, Usui HK, Dunn SR, McCue P, Bottinger E, Iozzo RV, Sharma K. Decorin deficiency enhances progressive nephropathy in diabetic mice. Am J Pathol. 2007;171:1441–1450. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Baghy K, Dezsó K, László V, Fullár A, Péterfia B, Paku S, Nagy P, Schaff Z, Iozzo RV, Kovalszky I. Ablation of the decorin gene enhances experimental hepatic fibrosis and impairs hepatic healing in mice. Lab Invest. 2011;91:439–451. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2010.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Goldoni S, Owens RT, McQuillan DJ, Shriver Z, Sasisekharan R, Birk DE, Campbell S, Iozzo RV. Biologically active decorin is a monomer in solution. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:6606–6612. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310342200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Rühland C, Schönherr E, Robenek H, Hansen U, Iozzo RV, Bruckner P, Seidler DG. The glycosaminoglycan chain of decorin plays an important role in collagen fibril formation at the early stages of fibrillogenesis. FEBS J. 2007;274:4246–4255. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05951.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Jungmann O, Nikolovska K, Stock C, Schulz J-N, Eckes B, Riethmüller C, Owens RT, Iozzo RV, Seidler DG. The dermatan sulfate proteoglycan decorin modulates α2β1 integrin and vimentin intermediate filament system during collagen synthesis. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e50809. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Theocharis AD, Tzanakakis G, Karamanos NK. Proteoglycans in health and disease: Novel proteoglycan roles in malignancy and their pharmacological targeting. FEBS J. 2010;277:3904–3923. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07800.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Iozzo RV, Cohen I. Altered proteoglycan gene expression and the tumor stroma. Cell Mol Life Sci. 1993;49:447–455. doi: 10.1007/BF01923588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Goldoni S, Iozzo RV. Tumor microenvironment: Modulation by decorin and related molecules harboring leucine-rich tandem motifs. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:2473–2479. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Iozzo RV, Sanderson RD. Proteoglycans in cancer biology, tumour microenvironment and angiogenesis. J Cell Mol Med. 2011;15:1013–1031. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01236.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Feugaing DDS, Götte M, Viola M. More than matrix: The multifaceted role of decorin in cancer. Eur J Cell Biol. 2013;92:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2012.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Iozzo RV, Moscatello D, McQuillan DJ, Eichstetter I. Decorin is a biological ligand for the epidermal growth factor receptor. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:4489–4492. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.8.4489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Santra M, Reed CC, Iozzo RV. Decorin binds to a narrow region of the epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor, partially overlapping with but distinct from the EGF-binding epitope. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:35671–35681. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205317200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Zhu J-X, Goldoni S, Bix G, Owens RA, McQuillan D, Reed CC, Iozzo RV. Decorin evokes protracted internalization and degradation of the EGF receptor via caveolar endocytosis. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:32468–32479. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503833200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Buraschi S, Pal N, Tyler-Rubinstein N, Owens RT, Neill T, Iozzo RV. Decorin antagonizes Met receptor activity and downregulates β-catenin and Myc levels. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:42075–42085. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.172841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Adany R, Heimer R, Caterson B, Sorrell JM, Iozzo RV. Altered expression of chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan in the stroma of human colon carcinoma. Hypomethylation of PG-40 gene correlates with increased PG-40 content and mRNA levels. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:11389–11396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Bi X, Tong C, Dokendorff A, Banroft L, Gallagher L, Guzman-Hartman G, Iozzo RV, Augenlicht LH, Yang W. Genetic deficiency of decorin causes intestinal tumor formation through disruption of intestinal cell maturation. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:1435–1440. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Bi X, Pohl NM, Yang GR, Gou Y, Guzman G, Kajdacsy-Balla A, Iozzo RV, Yang W. Decorin-mediated inhibition of colorectal cancer growth and migration is associted with E-cadherin in vitro and in mice. Carcinogenesis. 2012;33:326–330. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Iozzo RV, Chakrani F, Perrotti D, McQuillan DJ, Skorski T, Calabretta B, Eichstetter I. Cooperative action of germline mutations in decorin and p53 accelerates lymphoma tumorigenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:3092–3097. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.3092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Schaefer L, Iozzo RV. Small leucine-rich proteoglycans, at the crossroad of cancer growth and inflammation. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2012;22:56–57. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2011.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Goldoni S, Humphries A, Nyström A, Sattar S, Owens RT, McQuillan DJ, Ireton K, Iozzo RV. Decorin is a novel antagonistic ligand of the Met receptor. J Cell Biol. 2009;185:743–754. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200901129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Reed CC, Gauldie J, Iozzo RV. Suppression of tumorigenicity by adenovirus-mediated gene transfer of decorin. Oncogene. 2002;21:3688–3695. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Goldoni S, Seidler DG, Heath J, Fassan M, Baffa R, Thakur ML, Owens RA, McQuillan DJ, Iozzo RV. An anti-metastatic role for decorin in breast cancer. Am J Pathol. 2008;173:844–855. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.080275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Reed CC, Waterhouse A, Kirby S, Kay P, Owens RA, McQuillan DJ, Iozzo RV. Decorin prevents metastatic spreading of breast cancer. Oncogene. 2005;24:1104–1110. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Iozzo RV. Proteoglycans and neoplasia. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1988;7:39–50. doi: 10.1007/BF00048277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Santra M, Skorski T, Calabretta B, Lattime EC, Iozzo RV. De novo decorin gene expression suppresses the malignant phenotype in human colon cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7016–7020. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.15.7016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Santra M, Mann DM, Mercer EW, Skorski T, Calabretta B, Iozzo RV. Ectopic expression of decorin protein core causes a generalized growth suppression in neoplastic cells of various histogenetic origin and requires endogenous p21, an inhibitor of cyclin-dependent kinases. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:149–157. doi: 10.1172/JCI119507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Santra M, Eichstetter I, Iozzo RV. An anti-oncogenic role for decorin: downregulation of ErbB2 leads to growth suppression and cytodifferentiation of mammary carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:35153–35161. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006821200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Nash MA, Loercher AE, Freedman RS. In vitro growth inhibition of ovarian cancer cells by decorin: synergism of action between decorin and carboplatin. Cancer Res. 1999;59:6192–6196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Biglari A, Bataille D, Naumann U, Weller M, Zirger J, Castro MG, Lowenstein PR. Effects of ectopic decorin in modulating intracranial glioma progression in vivo, in a rat syngeneic model. Cancer Gene Therapy. 2004;11:721–732. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Tralhão JG, Schaefer L, Micegova M, Evaristo C, Schönherr E, Kayal S, Veiga-Fernandes H, Danel C, Iozzo RV, Kresse H, Lemarchand P. In vivo selective and distant killing of cancer cells using adenovirus-mediated decorin gene transfer. FASEB J. 2003;17:464–466. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0534fje. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Seidler DG, Goldoni S, Agnew C, Cardi C, Thakur ML, Owens RA, McQuillan DJ, Iozzo RV. Decorin protein core inhibits in vivo cancer growth and metabolism by hindering epidermal growth factor receptor function and triggering apoptosis via caspase-3 activation. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:26408–26418. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602853200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Moscatello DK, Santra M, Mann DM, McQuillan DJ, Wong AJ, Iozzo RV. Decorin suppresses tumor cell growth by activating the epidermal growth factor receptor. J Clin Investig. 1998;101:406–412. doi: 10.1172/JCI846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Iozzo RV. The family of the small leucine-rich proteoglycans: key regulators of matrix assembly and cellular growth. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 1997;32:141–174. doi: 10.3109/10409239709108551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Patel S, Santra M, McQuillan DJ, Iozzo RV, Thomas AP. Decorin activates the epidermal growth factor receptor and elevates cytosolic Ca2+ in A431 cells. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:3121–3124. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.6.3121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Csordás G, Santra M, Reed CC, Eichstetter I, McQuillan DJ, Gross D, Nugent MA, Hajnóczky G, Iozzo RV. Sustained down-regulation of the epidermal growth factor receptor by decorin. A mechanism for controlling tumor growth in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:32879–32887. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005609200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Albihn A, Johnsen JI, Henriksson MA. MYC in oncogenesis and as a target for cancer therapies. Adv Cancer Res. 2010;107:163–224. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(10)07006-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Neill T, Painter H, Buraschi S, Owens RT, Lisanti MP, Schaefer L, Iozzo RV. Decorin antagonizes the angiogenic network. Concurrent inhibition of Met, hipoxia inducible factor-1α and vascular endothelial growth factor A and induction of thrombospondin-1 and TIMP3. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:5492–5506. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.283499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Hu Y, Sun H, Owens RT, Wu J, Chen YQ, Berquin IM, Perry D, O’Flaherty JT, Edwards IJ. Decorin suppresses prostate tumor growth through inhibition of epidermal growth factor and androgen receptor pathways. Neoplasia. 2009;11:1042–1053. doi: 10.1593/neo.09760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Araki K, Wakabayashi H, Shintani K, Morikawa J, Matsumine A, Kusuzaki K, Sudo A, Uchida A. Decorin suppresses bone metastasis in a breast cancer cell line. Oncology. 2009;77:92–99. doi: 10.1159/000228253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Shintani K, Matsumine A, Kusuzaki K, Morikawa J, Matsubara T, Wakabayashi T, Araki K, Satonaka H, Wakabayashi H, Lino T, Uchida A. Decorin suppresses lung metastases of murine osteosarcoma. Oncology Reports. 2008;19:1533–1539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Buraschi S, Neill T, Owens RT, Iniguez LA, Purkins G, Vadigepalli R, Evans B, Schaefer L, Peiper SC, Wang Z, Iozzo RV. Decorin protein core affects the global gene expression profile of the tumor microenvironment in a triple-negative orthotopic breast carcinoma xenograft model. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e45559. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Iozzo RV, Buraschi S, Genua M, Xu S-Q, Solomides CC, Peiper SC, Gomella LG, Owens RT, Morrione A. Decorin antagonizes IGF receptor I (IGF-IR) function by interfering with IGF-IR activity and attenuating downstream signaling. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:34712–34721. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.262766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Pollak M. The insulin and insulin-like growth factor receptor family in neoplasia: an update. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:159–169. doi: 10.1038/nrc3215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Belfiore A, Frasca F, Pandini G, Sciacca L, Vigneri R. Insulin receptor isoforms and insulin receptor/insulin-like growth factor receptor hybrids in physiology and disease. Endocrine Rev. 2009;30:586–623. doi: 10.1210/er.2008-0047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Belfiore A, Malaguarnera R. Insulin receptor and cancer. Endocrine-Related Cancer. 2011;18:R125–R147. doi: 10.1530/ERC-11-0074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Baker J, Liu J-P, Robertson EJ, Efstratiadis A. Role of insulin-growth factor in embryonic and postnatal growth. Cell. 1993;75:73–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Liu J-P, Baker J, Perkins AS, Robertson EJ, Efstratiadis A. Mice carrying null mutations of the genes encoding insulin-like growth factor I (lgf-1) and type 1 IGF receptor (lgf1r) Cell. 1993;75:59–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Sell C, Dumenil G, Deveaud C, Miura M, Coppola D, DeAngelis T, Rubin R, Efstratiadis A, Baserga R. Effect of a null mutation of the insulin-like growth factor I receptor gene on growth and transformation of mouse embryo fibroblasts. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:3604–3612. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.6.3604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Garofalo G, Manara MC, Nicoletti G, Marino MT, Lollini P-L, Astolfi A, Pandini G, López-Guerrero JA, Schaefer K-L, Belfiore A, Picci P, Scotlandi K. Efficacy of and resistance to anti-IGF-1R therapies in Ewing’s sarcoma is dependent on insulin receptor signaling. Oncogene. 2011;30:2730–2740. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Malaguarnera R, Morcavallo A, Belfiore A. The insulin and IGF-I pathway in endocrine glands carcinogenesis. J Oncology. 20122012 doi: 10.1155/2012/635614. Article ID 635614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Baserga R. The contradictions of the insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor. Oncogene. 2000;19:5574–5581. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Lyons TR, O’Brien J, Borges VF, Conklin MW, Keely PJ, Eliceiri KW, Marusyk A, Tan A-C, Schedin P. Postpartum mammary gland involution drives progression of ductal carcinoma in situ through collagen and COX-2. Nat Med. 2011;17:1109–1115. doi: 10.1038/nm.2416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Morrione A, Valentinis B, Xu S-Q, Yumet G, Louvi A, Louvi A, Efstratiadis A, Baserga R. Insulin-like growth factor II stimulates cell proliferation through the insulin receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3777–3782. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.3777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Frasca F, Pandini G, Scalia P, Sciacca L, Mineo R, Costantino A, Goldfine ID, Belfiore A, Vigneri R. Insulin receptor isoform A, a newly recognized, high-affinity insulin-like growth factor II receptor in fetal and cancer cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:3278–3288. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.5.3278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Morcavallo A, Genua M, Palummo A, Kletvikova E, Jiracek J, Brzozowski AM, Iozzo RV, Belfiore A, Morrione A. Indulin and insulin-like growth factor II differentially regulate endocytic sorting and stability of insulin receptor isoform A. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:11422–11436. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.252478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Schönherr E, Sunderkötter C, Iozzo RV, Schaefer L. Decorin, a novel player in the insulin-like growth factor system. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:15767–15772. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500451200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Fiedler LR, Schönherr E, Waddington R, Niland S, Seidler DG, Aeschlimann D, Eble JA. Decorin regulates endothelial cell motility on collagen I through activation of Insulin-like growth factor I receptor and modulation of α2β1 integrin activity. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:17406–17415. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710025200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Johansson GS, Chisalita SI, Arnqvist HJ. Human microvascular endothelial cells are sensitive to IGF-I but resistant to insulin at the receptor level. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2008;296:58–63. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2008.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Schaefer L, Tsalastra W, Babelova A, Baliova M, Minnerup J, Sorokin L, Gröne H-J, Reinhardt DP, Pfeilschifter J, Iozzo RV, Schaefer RM. Decorin-mediated regulation of fibrillin-1 in the kidney involves the insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor and mammalian target of rapamycin. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:301–315. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Iacob D, Cai J, Tsonis M, Babwah A, Chakraborty RN, Lala PK. Decorin-mediated inhibition of proliferation and migration of the human trophoblast via different tyrosine kinase receptors. Endocrinology. 2008;149:6187–6197. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Khan GA, Girish GV, Lala N, DiGuglielmo GM, Lala PK. Decorin is a novel VEGFR-2-binding antagonist for the human extravillous trophoblast. Mol Endocrinol. 2011;25:1431–1443. doi: 10.1210/me.2010-0426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Dyrskjøt L, Kruhøffer M, Thykjaer T, Marcussen N, Jensen JL, Møller K, Ørntoft TF. Gene expression in the urinary bladder: A common carcinoma in situ gene expression signature exists disregarding histopathological classification. Cancer Res. 2004;64:4040–4048. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Sanchez-Carbayo M, Socci ND, Lozano J, Saint F, Cordon-Cardo C. Defining molecular profiles of poor outcome in patients with invasive bladder cancer using oligonucleotide microarrays. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:778–789. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.2375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Metalli D, Lovat F, Tripodi F, Genua M, Xu S-Q, Spinelli M, Alberghina L, Vanoni M, Baffa R, Gomella LG, Iozzo RV, Morrione A. The insulin-like growth factor receptor I promotes motility and invasion of bladder cancer cells through Akt- and mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent activation of paxillin. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:2997–3006. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Genua M, Xu S-Q, Buraschi S, Peiper SC, Gomella LG, Belfiore A, Iozzo RV, Morrione A. Prolyne-rich tyrosine kinase 2 (Pyk2) regulates IGF-I-induced cell motility and invasion of urothelial carcinoma cells. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e40148. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- [88].Iozzo RV, Schaefer L. Proteoglycans in health and disease: Novel regulatory signaling mechanisms evoked by the small leucine-rich proteoglycans. FEBS J. 2010;277:3864–3875. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07797.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Feugaing DDS, Tammi R, Echtermeyer FG, Stenmark H, Kresse H, Smollich M, Schönherr E, Kiesel L, Götte M. Endocytosis of the dermatan sulfate proteoglycan decorin utilizes multiple pathways and is modulated by epidermal growth factor receptor signaling. Biochimie. 2007;89:637–657. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2006.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Monami G, Emiliozzi V, Morrione A. Grb10/Nedd4-mediated multiubiquitination of the insulin-like growth factor receptor regulates receptor internalization. J Cell Physiol. 2008;216:426–437. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Moller AV, Jorgensen SP, Chen J-W, Larnkjaer A, Ledet T, Flyvbjerg A, Frystyk J. Glycosaminoglycans increase levels of free and bioactive IGF-I in vitro. Eur J Endocrin. 2006;155:297–305. doi: 10.1530/eje.1.02203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Arai T, Parker A, Busby WJr, Clemmons DR. Heparin, heparan sulfate, and dermatan sulfate regulate formation of the insulin-like growth factor-I and insulin-like growth factor-binding protein complexes. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:20388–20393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Purushothaman A, Babitz A, Sanderson RD. Heparanase enhances the insulin receptor signaling pathway to activate extracellular signal-regulated kinase in multiple myeloma. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:41288–41296. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.391417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Sanderson RD, Iozzo RV. Targeting heparanase for cancer therapy at the tumor-matrix interface. Matrix Biol. 2012;31:283–284. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Garofalo C, Mancarella C, Grilli A, Manara MC, Astolfi A, Marino MT, Conte A, Sigismund S, Carè A, Belfiore A, Picci P, Scotlandi K. Identification of common and distinctive mehanisms of resistance to different anti-IGF-IR agents in Ewing’s Sarcoma. Mol Endocrinol. 2012;26:1603–1616. doi: 10.1210/me.2012-1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Watson JA, Burling K, Fitzpatrick P, Kay E, Kelly J, Fitzpatrick JM, Dervan PA, McCann A. Urinary insulin-like growth factor 2 identifies the presence of urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. Brit J Urol Int. 2008;103:694–697. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.08213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]