Summary

The syndecans are a family of heparan-sulfate-decorated cell surface proteoglycans, matrix receptors with roles in cell adhesion and growth factor signaling. Their heparan sulfate chains recognize “heparin-binding” motifs ubiquitously present in the extracellular matrix (ECM), providing the means for syndecans to constitutively bind and cluster to sites of cell-matrix adhesion. Emerging evidence suggests that specialized docking sites in the syndecan extracellular domains may serve to localize other receptors to these sites as well, including integrins and growth factor receptor tyrosine kinases. A prototypic example of this mechanism is the capture of the αvβ3 integrin and insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor (IGF1R) by syndecan-1 (Sdc1) – forming a ternary receptor complex in which signaling downstream of IGF1R activates the integrin. This Sdc1-coupled ternary receptor complex is especially prevalent on tumor cells and activated endothelial cells undergoing angiogenesis, reflecting the upregulated expression of αvβ3 integrin in such cells. As such, much effort has focused on developing therapeutics that target this integrin in various cancers. Along these lines, the site in the Sdc1 ectodomain responsible for capture and activation of the αvβ3 or αvβ5 integrins by IGF1R can be mimicked by a short peptide called “synstatin” (SSTN), which competitively displaces the integrin and IGF1R kinase from the syndecan and inactivates the complex. This review summarizes our current knowledge of the Sdc1-coupled ternary receptor complex and the efficacy of SSTN as an emerging therapeutic to target this signaling mechanism.

Keywords: extracellular matrix, cell adhesion, VE-cadherin, VEGF, VEGFR2, heparan sulfate, proteoglycan, metastasis, recombinant protein, therapeutic

Introduction

The αvβ3 integrin has a major role in angiogenesis and tumorigenesis [1-5]. Although poorly expressed in most adult tissues, the integrin is highly expressed and active on metastatic tumor cells (e.g., breast [6, 7], myeloma [8-10], melanoma [11], prostate [12], ovarian [13], glioma [14, 15] and others) and vascular endothelial cells undergoing angiogenesis [16-18]. Active integrin participates in adhesion signaling, activation of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), proliferation, protection against apoptosis, migration and invasion [15]. It is constitutively expressed on osteoclasts and plays an essential role in their differentiation and bone-eroding activity in the bone marrow, particularly when stimulated by bone-homing tumor cells [19-22]. The αvβ3 integrin and its closely related cousin, the αvβ5 integrin, also have roles in pathological angiogenesis, a process upon which all successful tumors depend [3]. Quiescent endothelial cells stimulated with VEGF break their adherens junctions, proliferate, migrate and are protected against apoptosis by upregulated αvβ3 integrin [23-25]. Indeed, VEGF signaling through VEGFR2 (flk-1, KDR) is functionally coupled to the αvβ3 integrin [25, 26]. Although the mechanism for this remains unclear, both receptors (VEGFR2 and αvβ3 integrin) enhance and sustain one another's activity. Thus, effective blockade of the integrin in endothelial cells conceivably inhibits not only its function, but also the VEGF-initiated signal for adherens junction breakdown and the onset of angiogenesis. Angiogenesis also has roles in other human diseases aside from cancer, among them diabetic retinopathy, heart disease, macular degeneration, arthritis and psoriasis [27].

The mechanisms controlling αvβ3 integrin activation, as well as that of other integrins, have been the subject of intense investigation. With the exception of the α6β4 integrin, which binds the extracellular matrix (ECM) constitutively and signals in response to its clustering with receptor tyrosine kinases, the ability of other integrins to engage the ECM and signal (e.g., activation) is tightly regulated. Such integrins are activated by an “inside-out” signaling mechanism emanating from other signaling receptors [28, 29], although few complete inside-out signaling pathways have been defined. Talin plays a pivotal role in integrin-mediated events [30, 31], promotes integrin clustering [32] and its switch from a low to high affinity ligand-binding state [33-35]. Evidence now suggests that, at least in some cells, αvβ3 integrin activation by talin is likely to be mediated by the GTPase Rap1 and its effector RIAM [36].

Discovery of the Sdc1-coupled mechanism

Prior evidence shows that syndecans are clustered to sites of cell-matrix adhesion along with integrins and other type of receptors (reviewed in [28, 29, 37]). The matrix receptor syndecan-1 (Sdc1), a cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycan, associates directly with the αvβ3 and αvβ5 integrins via its extracellular domain – an association that is required for integrin activation in a variety of carcinoma [38-41], fibroblastic [42], vascular endothelial [39], and even myeloma cells (Ell, Purushothaman, Sanderson and Rapraeger, unpublished data) and likely reflects a major and generic role for the syndecan family of proteoglycans as signaling “hubs” at ECM adhesion sites (Fig. 1). This mechanism was initially discovered in mammary carcinoma cells plated on Sdc1 antibodies in an attempt to mimic ECM engagement by the syndecan and provide the opportunity to study signaling pathways activated by Sdc1 engagement [38, 40]. Several human mammary carcinoma cell lines actively spread on Sdc1 antibody, and this extends as well to activated vascular endothelial cells [39, 41]. These initial findings showed that spreading was blocked by inhibiting αvβ3 integrin with activation-blocking antibodies despite the clear lack of integrin engagement with the substratum [40]. Active integrin could also be observed on such spread cells using fluorescent fibrinogen or WOW-1 ligand mimetic antibody as a probe, indicating that Sdc1 engagement had activated the integrin, presumably via an inside-out signaling pathway [38, 40].

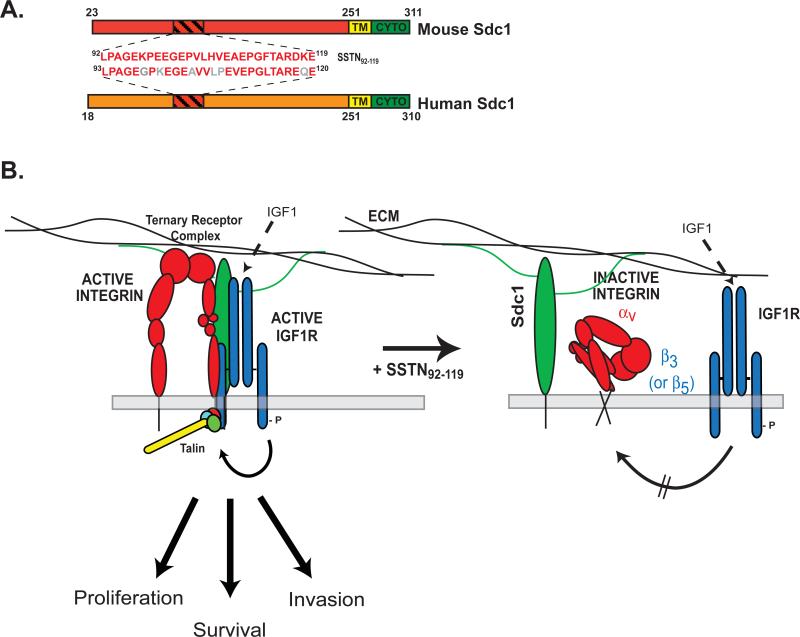

Figure 1. Model of Sdc1-coupled IGF1R activation of the αvβ3 or αvβ5 integrin.

A. Mature forms (lacking their signal peptides) of mouse and human Sdc1 are shown depicting their extracellular, transmembrane (TM) and cytoplasmic (CYTO) domains along with the numbering of their amino acid sequences. The site in the extracellular domain of mouse Sdc1 that captures αvβ3/αvβ5 integrin and IGF1R is amino acids 92-119 [39]. A highly homologous site (amino acids 93-120) exists in human. The amino acid sequence of SSTN derived from either human or mouse is shown, with nonconserved amino acids shown in gray (human sequence). B. Sdc1 ectodomain engages the αvβ3 or αvβ5 integrin, providing a docking site for the IGF1R. IGF1R becomes activated when Sdc1 is clustered by ECM engagement, or upon its binding of IGF-1 [41]. Active IGF1R initiates an inside-out signaling pathway culminating in the activation of talin [41]. Combined signaling from the integrin and IGF1R drives the proliferation, survival and migration of tumor cells and activated endothelial cells that depend on this ternary receptor complex. Capture of the integrin and IGF1R by Sdc1 is competitively blocked by SSTN92-119. Treatment of cells with this peptide displaces the receptors from the syndecan and prevents IGF1R and integrin activation. Even addition of IGF1, which causes IGF1R activation as measured by Y1131 in its cytoplasmic domain, fails to activate the integrin in the presence of SSTN [41]. Thus, assembly of the receptors into the ternary receptor complex is essential for integrin activation by IGF1R and the combined signaling from this receptor complex.

Perhaps as surprising as cell spreading in response to unliganded integrin was the finding that integrin activation does not require the Sdc1 cytoplasmic or transmembrane domain, as it can be initiated by the Sdc1 ectodomain alone anchored to the plasma membrane. That is, cells in which endogenous syndecan is replaced by GPI-linked extracellular domain, even lacking the attachment sites for heparan sulfate that endow the proteoglycan with several of its functional activities, are equally able to attach and spread on Sdc1 antibody [38].

Derivation of SSTN92-119

Recombinant mouse Sdc1 ectodomain was found to block the spreading of human MDA-MB-231 cells attached to human-specific Sdc1 antibody [40]. Since it was unlikely that the recombinant mouse protein was competing for adhesion to the human-specific antibody, this funding suggested that the protein was competing instead for some other interaction of the syndecan, such as its potential interaction with neighboring cell surface receptors. Truncation of the recombinant Sdc1 protein to the shortest sequence that retains full inhibitory activity resulted in derivation of a peptide known as synstatin (SSTN92-119) that competitively blocks this mechanism [39] (Fig. 1A) and demonstrates that the αvβ3(or αvβ5) integrin activation mechanism depends on an active site (amino acids 92-119) in the mouse syndecan sequence) that resides midway between the transmembrane domain and the more distal heparan sulfate chains (Fig. 1A). Sdc1 mutants lacking this site (e.g., Sdc1Δ67-121) fail to activate the integrin [38]. Human and mouse Sdc1 are highly homologous, with the active site in human Sdc1 (aa93-120) sharing nearly 80% homology to mouse (Fig. 1A). The human SSTN peptide also displays activity equal to that of the mouse peptide [39]. The SSTN sequence is unique to Sdc1 and is not found in other syndecans or in any other known protein.

Emerging evidence shows that syndecans may have one or more such “cell binding” regions in their ectodomains that cause them to associate with other receptors [38, 43-45]. The first such description was by McFall and Rapraeger [43, 44], who showed that cell surface receptor(s) on fibroblasts recognize amino acids 78-131 in the recombinant human Sdc4 ectodomain. Whiteford et al. have extended this work, showing that several short motifs within this region are highly conserved across species, and that one such site, NxIP, appears important for the regulation of integrin-mediated cell adhesion in mesenchymal cells, although the mechanism remains poorly understood [45, 46]. This group has also identified an active site in Sdc2 [47].

Activation of αvβ3 integrin requires IGF1R

How its coupling to Sdc1 serves to activate the integrin during initial cell spreading assays was not immediately clear. It seemed unlikely that the syndecan itself would initiate an inside-out signaling pathway, especially without the participation of its transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains. Thus, the molecular targets of SSTN were envisioned to be the αvβ3 or αvβ5 integrin itself plus an additional cell surface receptor – likely a kinase – necessary to activate the integrin. A screen of tyrosine kinase inhibitors applied to carcinoma or vascular endothelial cells spreading on Sdc1-specific antibody identified the activating receptor as the insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor (IGF1R) [41]. This kinase had previously been linked to αvβ3 integrin activity by Clemmons and co-workers, who demonstrated a cross-talk mechanism involving αvβ3 integrin and IGF1R in vascular smooth muscle cells [48, 49]. The model developed by this group suggests that the integrin, when active, associates with IGF1R, sequesters the phosphatase SHP2 and thus prevents SHP2-mediated dephosphorylation and inactivation of IGF1R [50]. Immunoprecipitation of Sdc1 from cells expressing αvβ3 integrin and IGF1R shows that these three receptors assemble into a ternary complex that is disrupted by competition with SSTN92-119 (Fig. 1B) [41]. The three also assemble into focal contacts in endothelial cells plated on vitronectin [41] – one of the few current demonstrations of Sdc1 in focal contacts, a site where Sdc4 is typically ubiquitous [37]. The nature of these focal contacts, containing αvβ3 or αvβ5 integrin and IGF-1R, are likely to be distinct from those containing Sdc4, where β1 integrins are typically found.

The formation of the Sdc1-coupled ternary receptor complex can be duplicated using recombinant and/or purified receptors in vitro. The integrin and IGF1R show only low affinity for one another when tested alone in bead pull-down assays. However, a preformed Sdc1:integrin complex effectively captures the IGF1R tyrosine kinase, suggesting that syndecan and integrin extracellular domains form a docking interface that is recognized by IGF1R. SSTN92-119 competitively blocks integrin capture by Sdc1, as well as formation of the Sdc1:integrin:IGF1R ternary complex. SSTN prelabeled with Sulfo-SBED, a UV photoactivatable biotin transfer reagent transfers biotin to αvβ3 or αvβ5 integrin and IGF1R on endothelial cells, but no other receptors are identified as SSTN targets on these cells [41].

Displacement of IGF1R by SSTN blocks integrin activation

Capture of IGF1R by Sdc1 and αvβ3 integrin does not activate its tyrosine kinase. However, clustering of the complex with antibodies, or by Sdc1 engaging matrix ligands, causes auto-activation of IGF1R and initiates a downstream signal that culminates in talin-mediated integrin activation [39, 41]. Thus, IGF1 is not required, although the growth factor can activate the mechanism via its activation of IGF1R [41]. The heparan sulfate chains on Sdc1 are not inherently required for the mechanism, but are required if activation requires Sdc1 engaging the ECM. A feature of the mechanism that remains poorly understood is that IGF1R needs to be physically present as a partner in the ternary complex in order to active the integrin. That is, IGF1R that has been displaced by SSTN does not cause integrin activation, even when stimulated with IGF1 [41]. Thus, stimulation of the inside-out signaling pathway necessitates IGF1R capture with Sdc1 and the integrin. How the ternary complex facilitates this signaling is not clear. It is possible that it has a structural role; that is, binding of Sdc1 and/or IGF1R to the integrin extracellular domain may be essential for the integrin to establish or maintain its activated conformation. A second and perhaps more likely possibility is that one or more of these receptors localizes elements of the signaling pathway to the integrin and therefore cannot be activated if Sdc1 or IGF1R is absent. Possibilities are Rap1 or RIAM, which are necessary for talin activation [36], or localization of talin itself. Note that Sdc1 appears to be fully functional even when expressed as a GPI-linked ectodomain [38], suggesting that its membrane and cytoplasmic domains perform no essential role in this activation mechanism.

Efficacy of SSTN as a cancer therapeutic

The specificity of SSTN92-119 for Sdc1-mediated integrin activation supports its use as a probe to detect this mechanism in cellular processes. SSTN is a potent inhibitor of angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo and blocks αvβ3-mediated tumor cell adhesion and migration and tumor formation in mouse models [39] (Fig. 2). The peptide displays an IC50 of 100-300 nM when used in vitro to inhibit αvβ3 dependent adhesion and cell migration on VN, or in aortic ring angiogenesis assays in which VEGF- and αvβ3-integrin dependent microvessel outgrowth is blocked by the peptide [39]. Mice implanted with Alzet pumps delivering systemic levels of ca. 2 μM SSTN92-119 inhibit the growth of breast carcinoma xenografts and FGF-induced angiogenesis in the corneal pocket angiogenesis assay by ca. 90% [39]. The mammary tumors also display over 10-fold reduction in neovessel formation, demonstrating efficacy of the peptide against tumor-induced angiogenesis. SSTN is also effective against angiogenesis stimulated by Sdc1 shed from myeloma cells, although the exact mechanism for this stimulation remains under investigation [51]. Although comprehensive toxicology studies remain to be performed, mice treated with these or 10-fold higher concentrations of SSTN show no overt toxic effects such a weight loss, reduced physical activity or changes in behavior (Rapraeger, Beauvais and Thomas, unpublished data). Thus, SSTN shows great promise as a new therapeutic for disease processes that involve the αvβ3 or αvβ5 integrin.

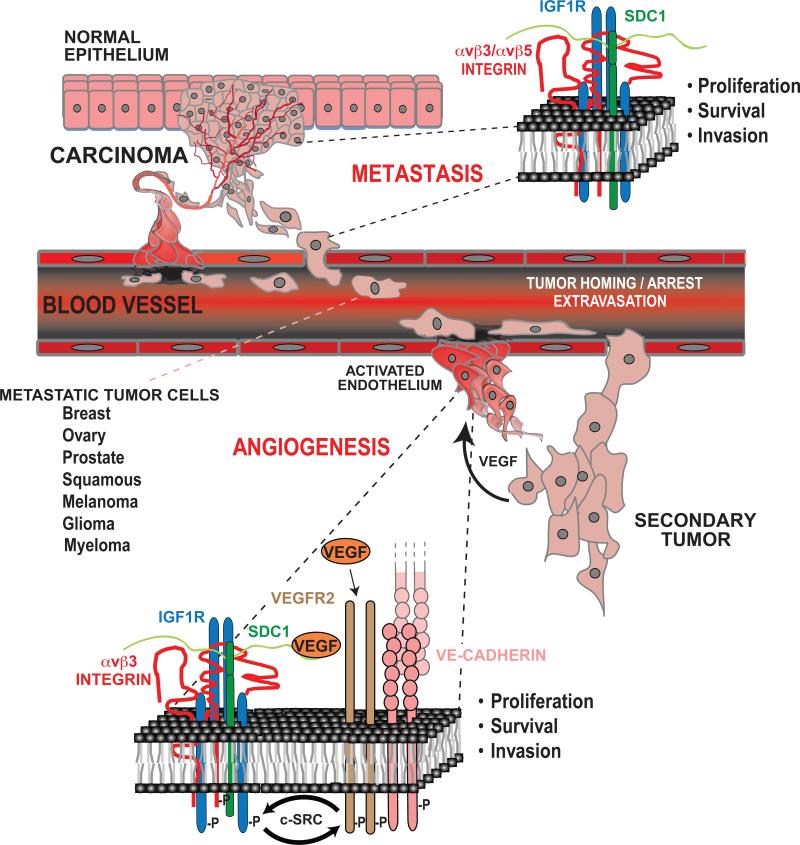

Figure 2. Role of the Sdc1-coupled ternary receptor complex in tumor metastasis and tumor-induced angiogenesis.

Normal epithelia lack expression of the ternary receptor complex because, although they express Sdc1 and IGF1R, they lack the αvβ3 or αvβ5 integrin. However, carcinoma cells invariable upregulate the expression of one or both of these integrins leading to assembly of the complex. Signaling from the ternary complex drives the proliferation, invasion and survival of the metastatic carcinoma cells as they invade the bloodstream and extravasate to distant sites to form secondary tumors. In a similar fashion, αvβ3 and αvβ5 integrin expression is upregulated on activated vascular endothelial cells responding to tumor-released VEGF to undergo angiogenesis. Activation of the ternary complex is critical for VEGF signaling. VEGF-mediated stimulation of VEGFR2 causes activation of the ternary complex via c-Src. Likewise, the activated ternary complex is necessary for VEGFR2 activation, again mediated by the Src-mediated link of these two receptor signaling mechanisms. This activation also depends on clustering of VE-cadherin that occurs upon homotypic adhesion between neighboring endothelial cells, as blockade of VE-cadherin with blocking antibodies, which is known to block angiogenesis, disrupts activation of the ternary complex and blocks VEGFR2 activation that by VEGF. Thus, SSTN92-119 is a potent inhibitor of tumor cell invasion and angiogenesis upon which the tumor depends. (See text for details).

Coupling of the Sdc1-coupled ternary complex to VEGFR2 and VE-cadherin during angiogenesis

Various reports describe the association of the αvβ3 integrin with other receptor tyrosine kinases, such as PDGFR-β and VEGFR2 [25, 26, 52, 53]. This raises the question of whether these kinases also interact with Sdc1 and replace IGF1R in the syndecan-coupled integrin complex, or whether IGF1R remains as the “core activator” in the complex and is the target through which other kinases activate the integrin. In one such example that has been examined recently, namely, αvβ3 activation by VEGFR2, it appears that the IGF1R remains the core activator (Fig. 2).

Expression of the αvβ3 integrin is upregulated on activated endothelial cells [54, 55]. Its signaling causes breakdown of adherens junctions, mediates endothelial cell migration into the stromal matrix, and promotes their proliferation and survival [17, 18, 25, 56-59]. Agents that block integrin activation inhibit angiogenesis in response to wound healing or tumorigenesis [17, 39, 56, 60-62]. Using the aortic ring explant model of angiogenesis, SSTN peptide is found to block VEGF-stimulated angiogenesis [39, 63] but only during the early phase of endothelial cell dissemination – a period of time that coincides with adherens junction breakdown in response to VEGF [63]. Endothelial cell dissemination beyond this early time point relies on β1 integrins (likely α2β1 or α5β1 depending on the substrate), which feed back when activated to downregulate the Sdc1-coupled complex.

The αvβ3 integrin and VEGFR2 form a complex wherein VEGFR2 activates the αvβ3 integrin and the activated integrin sustains VEGFR2 signaling [25, 26, 64]. This cross-regulation appears to rely not only on the phosphorylated state of the VEGFR2, but also on phosphorylation of the β3 subunit at Y747 and Y759 [34], as a Y747F/Y759F β3 integrin mutant neither forms a complex with VEGFR2 nor sustains VEGFR2 signaling. Work in this issue of FEBS J. [63] shows that VEGF stimulated migration of vascular endothelial cells depends on αvβ3 integrin and is blocked by SSTN, suggesting that VEGF activates the integrin via the Sdc1-coupled IGF1R. Indeed, VEGF stimulation of the cells is found to not only activate VEGFR2, but also IGF1R. Another interesting feature of this stimulation is that it is linked to VE-cadherin – the vascular endothelial cell-specific cell-cell adhesion receptor. Clustering of VE-cadherin in vascular endothelial cells, either via cell-cell contact or by using recombinant Fc/VE-cadherin chimeras, triggers VEGFR2-dependent activation of IGF1R and the αvβ3 integrin that is disrupted by SSTN92-119 (Fig. 2). The link between these receptors and the core activation complex appears to be mediated by c-Src. Although the exact function of c-Src is yet to be clarified, it is likely to phosphorylate several, if not all of these receptors, and provide the means for other cytoplasmic scaffolding and signaling molecules to sustain VEGF signaling, likely via displacing or inhibiting phosphatases [24, 65]. This fails to occur if the αvβ3 integrin is not activated and Sdc1-coupled IGF1R appears to be a key regulator of this activation.

Summary

The capture of IGF1R and αvβ3 (or αvβ5) integrin by the matrix receptor Sdc1 appears essential for activation of the integrin. This mechanism is not found in normal epithelial cells or resting endothelium, but is upregulated on activated endothelial cells, carcinoma cells and other types of tumor cells due to upregulated expression of the integrin. Capture of IGF1R, together with its clustering with Sdc1 to ECM adhesion sites, activates the kinase and thus the integrin, driving tumor and endothelial cell survival and invasion necessary for tumorigenesis that is known to depend on this integrin. Targeting the capture mechanism with SSTN, a peptide based on the interaction site in the syndecan necessary to assemble the ternary receptor complex, blocks integrin activation, tumor and endothelial cell migration, angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo, and tumor growth in animal models. Whether SSTN disrupts IGF1R signaling, in addition to integrin activation, remains unknown at present. The efficacy of SSTN in these animal models suggests that it is a promising candidate for further development as a syndecan-based therapeutic to target cancer and other diseases that depend on this mechanism.

This work suggests an important regulatory role for syndecans as “organizers” at sites of cell-matrix adhesion. Constitutively bound to the ECM via their heparan sulfate chains at these sites, syndecans may function as central organizers that capture other receptors (integrins, receptor tyrosine kinases, membrane phosphatases, cell-cell adhesion receptors?) to docking sites in their extracellular domains, effectively clustering and activating these receptors via their endogenous kinase domains or associated kinases. As such, targeting the function of a docking site in the “organizer” with competitive peptides, antibodies or chemical therapeutics may prove effective at blocking the myriad of signaling activities emanating from these receptor complexes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by funds to A.R. from the National Institutes of Health (R01-CA109010, R01-CA119939 and R01-CA139872) and the American Heart Association (09GRNT2250572).

ABBREVIATIONS

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- Fc/VE-cadherin

immunoglobulin Fc/VE-cadherin extracellular domain fusion protein

- IGF1R

insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor

- Sdc1

Syndecan-1

- SSTN

synstatin

- VE-cadherin

Vascular endothelial cadherin

- VEGF

vascular endothelial cell growth factor

- VEGFR2

VEGF tyrosine kinase receptor 2

REFERENCES CITED

- 1.Byzova TV, Plow EF. Activation of alphaVbeta3 on vascular cells controls recognition of prothrombin. The Journal of cell biology. 1998;143:2081–2092. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.7.2081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cai W, Chen X. Anti-angiogenic cancer therapy based on integrin alphavbeta3 antagonism. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2006;6:407–428. doi: 10.2174/187152006778226530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Folkman J. Role of angiogenesis in tumor growth and metastasis. Semin Oncol. 2002;29:15–18. doi: 10.1053/sonc.2002.37263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoelzemann G. Recent advances in alphavbeta3 integrin inhibitors. IDrugs. 2001;4:72–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kumar CC, Malkowski M, Yin Z, Tanghetti E, Yaremko B, Nechuta T, Varner J, Liu M, Smith EM, Neustadt B, et al. Inhibition of angiogenesis and tumor growth by SCH221153, a dual alpha(v)beta3 and alpha(v)beta5 integrin receptor antagonist. Cancer Res. 2001;61:2232–2238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pecheur I, Peyruchaud O, Serre CM, Guglielmi J, Voland C, Bourre F, Margue C, Cohen-Solal M, Buffet A, Kieffer N, et al. Integrin alpha(v)beta3 expression confers on tumor cells a greater propensity to metastasize to bone. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2002;16:1266–1268. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0911fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liapis H, Flath A, Kitazawa S. Integrin alpha V beta 3 expression by bone-residing breast cancer metastases. Diagn Mol Pathol. 1996;5:127–135. doi: 10.1097/00019606-199606000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ria R, Vacca A, Ribatti D, Di Raimondo F, Merchionne F, Dammacco F. Alpha(v)beta(3) integrin engagement enhances cell invasiveness in human multiple myeloma. Haematologica. 2002;87:836–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vacca A, Ria R, Presta M, Ribatti D, Iurlaro M, Merchionne F, Tanghetti E, Dammacco F. alpha(v)beta(3) integrin engagement modulates cell adhesion, proliferation, and protease secretion in human lymphoid tumor cells. Exp Hematol. 2001;29:993–1003. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(01)00674-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhan F, Tian E, Bumm K, Smith R, Barlogie B, Shaughnessy J., Jr. Gene expression profiling of human plasma cell differentiation and classification of multiple myeloma based on similarities to distinct stages of late-stage B-cell development. Blood. 2003;101:1128–1140. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-06-1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seftor RE. Role of the beta3 integrin subunit in human primary melanoma progression: multifunctional activities associated with alpha(v)beta3 integrin expression. The American journal of pathology. 1998;153:1347–1351. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)65719-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCabe NP, De S, Vasanji A, Brainard J, Byzova TV. Prostate cancer specific integrin alphavbeta3 modulates bone metastatic growth and tissue remodeling. Oncogene. 2007;26:6238–6243. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Landen CN, Kim TJ, Lin YG, Merritt WM, Kamat AA, Han LY, Spannuth WA, Nick AM, Jennnings NB, Kinch MS, et al. Tumor-selective response to antibody-mediated targeting of alphavbeta3 integrin in ovarian cancer. Neoplasia. 2008;10:1259–1267. doi: 10.1593/neo.08740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gladson CL, Hancock S, Arnold MM, Faye-Petersen OM, Castleberry RP, Kelly DR. Stage-specific expression of integrin alphaVbeta3 in neuroblastic tumors. The American journal of pathology. 1996;148:1423–1434. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uhm JH, Gladson CL, Rao JS. The role of integrins in the malignant phenotype of gliomas. Frontiers in bioscience : a journal and virtual library. 1999;4:D188–199. doi: 10.2741/uhm. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rusnati M, Tanghetti E, Dell'Era P, Gualandris A, Presta M. alphavbeta3 integrin mediates the cell-adhesive capacity and biological activity of basic fibroblast growth factor (FGF-2) in cultured endothelial cells. Mol Biol Cell. 1997;8:2449–2461. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.12.2449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brooks PC, Montgomery AM, Rosenfeld M, Reisfeld RA, Hu T, Klier G, Cheresh DA. Integrin alpha v beta 3 antagonists promote tumor regression by inducing apoptosis of angiogenic blood vessels. Cell. 1994;79:1157–1164. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Friedlander M, Brooks PC, Shaffer RW, Kincaid CM, Varner JA, Cheresh DA. Definition of two angiogenic pathways by distinct alpha v integrins. Science. 1995;270:1500–1502. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5241.1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bataille R, Chappard D, Marcelli C, Dessauw P, Sany J, Baldet P, Alexandre C. Mechanisms of bone destruction in multiple myeloma: the importance of an unbalanced process in determining the severity of lytic bone disease. J Clin Oncol. 1989;7:1909–1914. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1989.7.12.1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McHugh KP, Hodivala-Dilke K, Zheng MH, Namba N, Lam J, Novack D, Feng X, Ross FP, Hynes RO, Teitelbaum SL. Mice lacking beta3 integrins are osteosclerotic because of dysfunctional osteoclasts. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:433–440. doi: 10.1172/JCI8905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Teitelbaum SL. Bone resorption by osteoclasts. Science. 2000;289:1504–1508. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5484.1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adams RH, Wilkinson GA, Weiss C, Diella F, Gale NW, Deutsch U, Risau W, Klein R. Roles of ephrinB ligands and EphB receptors in cardiovascular development: demarcation of arterial/venous domains, vascular morphogenesis, and sprouting angiogenesis. Genes & Devel. 1999;13:295–306. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.3.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brakenhielm E. Substrate matters: reciprocally stimulatory integrin and VEGF signaling in endothelial cells. Circ Res. 2007;101:536–538. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.160937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dejana E, Orsenigo F, Lampugnani MG. The role of adherens junctions and VE-cadherin in the control of vascular permeability. Journal of cell science. 2008;121:2115–2122. doi: 10.1242/jcs.017897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mahabeleshwar GH, Feng W, Reddy K, Plow EF, Byzova TV. Mechanisms of integrin-vascular endothelial growth factor receptor cross-activation in angiogenesis. Circ Res. 2007;101:570–580. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.155655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Somanath PR, Malinin NL, Byzova TV. Cooperation between integrin alphavbeta3 and VEGFR2 in angiogenesis. Angiogenesis. 2009;12:177–185. doi: 10.1007/s10456-009-9141-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carmeliet P, Jain RK. Angiogenesis in cancer and other diseases. Nature. 2000;407:249–257. doi: 10.1038/35025220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Theocharis AD, Skandalis SS, Tzanakakis GN, Karamanos NK. Proteoglycans in health and disease: novel roles for proteoglycans in malignancy and their pharmacological targeting. The FEBS journal. 2010;277:3904–3923. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07800.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manon-Jensen T, Itoh Y, Couchman JR. Proteoglycans in health and disease: the multiple roles of syndecan shedding. The FEBS journal. 2010;277:3876–3889. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07798.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Critchley DR, Gingras AR. Talin at a glance. Journal of cell science. 2008;121:1345–1347. doi: 10.1242/jcs.018085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Critchley DR. Biochemical and structural properties of the integrin-associated cytoskeletal protein talin. Annu Rev Biophys. 2009;38:235–254. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.050708.133744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cluzel C, Saltel F, Lussi J, Paulhe F, Imhof BA, Wehrle-Haller B. The mechanisms and dynamics of (alpha)v(beta)3 integrin clustering in living cells. The Journal of cell biology. 2005;171:383–392. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200503017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Calderwood DA. Integrin activation. Journal of cell science. 2004;117:657–666. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harburger DS, Calderwood DA. Integrin signalling at a glance. Journal of cell science. 2009;122:159–163. doi: 10.1242/jcs.018093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tadokoro S, Shattil SJ, Eto K, Tai V, Liddington RC, de Pereda JM, Ginsberg MH, Calderwood DA. Talin binding to integrin beta tails: a final common step in integrin activation. Science. 2003;302:103–106. doi: 10.1126/science.1086652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee HS, Lim CJ, Puzon-McLaughlin W, Shattil SJ, Ginsberg MH. RIAM activates integrins by linking talin to ras GTPase membrane-targeting sequences. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2009;284:5119–5127. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807117200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Couchman JR, Chen L, Woods A. Syndecans and cell adhesion. Int Rev Cytol. 2001;207:113–150. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(01)07004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Beauvais DM, Burbach BJ, Rapraeger AC. The syndecan-1 ectodomain regulates alphavbeta3 integrin activity in human mammary carcinoma cells. J Cell Biol. 2004;167:171–181. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200404171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beauvais DM, Ell BJ, McWhorter AR, Rapraeger AC. Syndecan-1 regulates alphavbeta3 and alphavbeta5 integrin activation during angiogenesis and is blocked by synstatin, a novel peptide inhibitor. J Exp Med. 2009;206:691–705. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Beauvais DM, Rapraeger AC. Syndecan-1-mediated cell spreading requires signaling by alphavbeta3 integrins in human breast carcinoma cells. Exp Cell Res. 2003;286:219–232. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(03)00126-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Beauvais DM, Rapraeger AC. Syndecan-1 couples the insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor to inside-out integrin activation. Journal of cell science. 2010;123:3796–3807. doi: 10.1242/jcs.067645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McQuade KJ, Beauvais DM, Burbach BJ, Rapraeger AC. Syndecan-1 regulates alphavbeta5 integrin activity in B82L fibroblasts. Journal of cell science. 2006;119:2445–2456. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McFall AJ, Rapraeger AC. Identification of an adhesion site within the syndecan-4 extracellular protein domain. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:12901–12904. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.20.12901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McFall AJ, Rapraeger AC. Characterization of the high affinity cell-binding domain in the cell surface proteoglycan syndecan-4. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:28270–28276. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.43.28270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Whiteford JR, Couchman JR. A conserved NXIP motif is required for cell adhesion properties of the syndecan-4 ectodomain. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2006;281:32156–32163. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605553200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Whiteford JR, Ko S, Lee W, Couchman JR. Structural and cell adhesion properties of zebrafish syndecan-4 are shared with higher vertebrates. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2008;283:29322–29330. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803505200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Whiteford JR, Behrends V, Kirby H, Kusche-Gullberg M, Muramatsu T, Couchman JR. Syndecans promote integrin-mediated adhesion of mesenchymal cells in two distinct pathways. Exp Cell Res. 2007;313:3902–3913. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Clemmons DR, Maile LA. Interaction between insulin-like growth factor-I receptor and alphaVbeta3 integrin linked signaling pathways: cellular responses to changes in multiple signaling inputs. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:1–11. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Maile LA, Clemmons DR. Regulation of insulin-like growth factor I receptor dephosphorylation by SHPS-1 and the tyrosine phosphatase SHP-2. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2002;277:8955–8960. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109258200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ling Y, Maile LA, Badley-Clarke J, Clemmons DR. DOK1 mediates SHP-2 binding to the alphaVbeta3 integrin and thereby regulates insulin-like growth factor I signaling in cultured vascular smooth muscle cells. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2005;280:3151–3158. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411035200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Purushothaman A, Uyama T, Kobayashi F, Yamada S, Sugahara K, Rapraeger AC, Sanderson RD. Heparanase-enhanced shedding of syndecan-1 by myeloma cells promotes endothelial invasion and angiogenesis. Blood. 2010;115:2449–2457. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-234757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Borges E, Jan Y, Ruoslahti E. Platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 bind to the beta 3 integrin through its extracellular domain. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:39867–39873. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007040200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Soldi R, Mitola S, Strasly M, Defilippi P, Tarone G, Bussolino F. Role of alphavbeta3 integrin in the activation of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2. EMBO J. 1999;18:882–892. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.4.882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Max R, Gerritsen RR, Nooijen PT, Goodman SL, Sutter A, Keilholz U, Ruiter DJ, De Waal RM. Immunohistochemical analysis of integrin alpha vbeta3 expression on tumor-associated vessels of human carcinomas. Int J Cancer. 1997;71:320–324. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19970502)71:3<320::aid-ijc2>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sepp NT, Li LJ, Lee KH, Brown EJ, Caughman SW, Lawley TJ, Swerlick RA. Basic fibroblast growth factor increases expression of the alpha v beta 3 integrin complex on human microvascular endothelial cells. J Invest Dermatol. 1994;103:295–299. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12394617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brooks PC, Clark RA, Cheresh DA. Requirement of vascular integrin alpha v beta 3 for angiogenesis. Science. 1994;264:569–571. doi: 10.1126/science.7512751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stupack DG, Cheresh DA. Apoptotic cues from the extracellular matrix: regulators of angiogenesis. Oncogene. 2003;22:9022–9029. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stupack DG, Puente XS, Boutsaboualoy S, Storgard CM, Cheresh DA. Apoptosis of adherent cells by recruitment of caspase-8 to unligated integrins. J Cell Biol. 2001;155:459–470. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200106070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Avraamides CJ, Garmy-Susini B, Varner JA. Integrins in angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:604–617. doi: 10.1038/nrc2353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gutheil JC, Campbell TN, Pierce PR, Watkins JD, Huse WD, Bodkin DJ, Cheresh DA. Targeted antiangiogenic therapy for cancer using Vitaxin: a humanized monoclonal antibody to the integrin alphavbeta3. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:3056–3061. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Maeshima Y, Colorado PC, Torre A, Holthaus KA, Grunkemeyer JA, Ericksen MB, Hopfer H, Xiao Y, Stillman IE, Kalluri R. Distinct antitumor properties of a type IV collagen domain derived from basement membrane. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:21340–21348. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001956200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Buerkle MA, Pahernik SA, Sutter A, Jonczyk A, Messmer K, Dellian M. Inhibition of the alpha-V integrins with a cyclic RGD peptide impairs angiogenesis, growth and metastasis of solid tumours in vivo. Br J Cancer. 2002;86:788–795. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rapraeger AC, Ell BJ, Roy M, Li X, Morrison OR, Thomas GM, Beauvais DM. VE-cadherin stimulates syndecan-1-coupled IGF1R and cross-talk between alphaVbeta3 integrin and VEGFR2 at the onset of endothelial cell dissemination during angiogenesis. The FEBS journal. 2013 doi: 10.1111/febs.12134. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Robinson SD, Hodivala-Dilke KM. The role of beta3-integrins in tumor angiogenesis: context is everything. Current opinion in cell biology. 2011;23:630–637. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2011.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bazzoni G, Dejana E. Endothelial cell-to-cell junctions: molecular organization and role in vascular homeostasis. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:869–901. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00035.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]