Abstract

Oncogenic alterations in MET or ALK have been identified in a variety of human cancers. Crizotinib (PF02341066) is a dual MET and ALK inhibitor and approved for the treatment of a subset of non-small-cell lung carcinoma; and in clinical development for other malignancies. Crizotinib can induce apoptosis in cancer cells while the underlying mechanisms are not well understood. In this study, we found that crizotinib induces apoptosis in colon cancer cells through the BH3-only protein PUMA. In cells with wild-type p53, crizotinib induces rapid induction of PUMA and Bim accompanied by p53 stabilization and DNA damage response. The induction of PUMA and Bim is mediated largely by p53, and deficiency in PUMA or p53, but not Bim, blocks crizotinib-induced apoptosis. Interestingly, MET knockdown led to selective induction of PUMA, but not Bim or p53. Crizotinib also induced PUMA-dependent apoptosis in p53-deficient colon cancer cells, and synergized with gefitinib or sorafenib to induce marked apoptosis via PUMA in colon cancer cells. Furthermore, PUMA deficiency suppressed apoptosis and therapeutic responses to crizotinib in xenograft models. These results establish a critical role of PUMA in mediating apoptotic responses of colon cancer cells to crizotinib, and suggest that mechanisms of oncogenic addiction to MET/ALK-mediated survival might be cell-type specific. These findings have important implications for future clinical development of crizotinib.

Keywords: crizotinib, PUMA, p53, apoptosis, colon cancer

Introduction

Receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) are cell surface receptors that act upon a variety of ligands including growth factors, cytokines, and hormones. RTKs are vital regulators of normal cell physiology and play critical roles in the development and progression of human cancer (1–2). MET is an extensively studied RTK and the receptor for hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) (3). The activation of MET by HGF ligation initiates various signaling cascades, such as the PI3K/AKT and RAS/RAF/MAPK pathways, to induce cell survival, proliferation, migration, and tissue regeneration (3). Aberrant activation of MET can result from gene amplification, transcriptional upregulation, missense mutations, or ligand autocrine loops, and is implicated in the pathogenesis of many human cancers (2–3). In colon cancer, MET over-expression and gene amplification are associated with advanced diseases and poor prognosis (4–5).

Recent efforts in cancer genomics continue to identify aberrantly activated oncogenic kinases and facilitate the development of targeted agents. This approach is expected to ultimately deliver safer and more effective cancer therapeutics (6). MET-targeting agents currently in clinical use include the monoclonal antibody MetAb (7) (Roche) and small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), such as ARQ197 (ArQule/Daiichi Sankyo) (8), INCB28060 (Incyte) (9), and crizotinib (PF02341066, Pfizer) (10). Crizotinib was initially designed as a selective ATP-competitive MET inhibitor and later found to inhibit several related kinases, including anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) (10), C-ros oncogene1, and receptor tyrosine kinase (ROS1) (11). Crizotinib has received the FDA’s approval for the treatment of ALK-rearranged non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), and is being evaluated in patients with other malignancies. Crizotinib has garnered much attention as it inhibits MET- and ALK-dependent tumor cell growth, migration, and invasion via both HGF-dependent and -independent mechanisms (12). Crizotinib also induces apoptosis in cancer cells; however the underlying mechanisms are not well understood. Currently, there is no reliable biomarker for crizotinib response other than ALK or ROS1 rearrangement (11, 13–14).

Apoptosis plays an important role in the anti-tumor activities of conventional chemotherapeutic agents and targeted therapies (1, 15–16). The Bcl-2 family proteins are the central regulators of mitochondria-mediated apoptosis. The BH3-only family members are first engaged in response to distinct as well as overlapping signals. Several of them, such as Bim and PUMA, are potent inducers of apoptosis by activating Bax/Bak following the neutralization of anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family members (15, 17). We and others have shown that PUMA functions as a critical initiator of apoptosis in both p53-dependent and -independent manners in a wide variety of cell types (18). PUMA transcription is directly activated by p53 in response to DNA damage (18), and lack of its induction renders p53-deficient cancer cells refractory to chemotherapeutic drugs and radiation. PUMA induction by non-genotoxic stimuli is generally p53-independent, and mediated by transcription factors such as p73 (19–20), forkhead box O3a (FoxO3a) (21–22), and nuclear factor (NF)-κB (23–24). Upon induction, PUMA potently induces apoptosis by antagonizing anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family members and/or directly activating the pro-apoptotic members Bax and Bak, leading to mitochondrial dysfunction and caspase activation cascade (18).

In this study, we investigated the underlying mechanisms of crizotinib-induced apoptosis in colon cancer cells, and found that both p53-dependent and -independent induction of PUMA contributes to crizotinib-induced apoptosis. These results provide novel mechanistic insight into the therapeutic responses of crizotinib, a rationale for manipulating PUMA and BH3-only proteins to improve the efficacy of targeted therapies, as well as therapy-induced changes in their expression as potential biomarkers.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and drug treatment

Human colorectal cancer cell lines, including HCT116, RKO, LoVo, DLD1, and HT29 were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). The isogenic cell lines, including PUMA-KO (25), p53-KO (26), and p53 binding site -KO (BSKO) (27) HCT116 cells, PUMA-KO DLD1 cells (27), and p53-KO RKO cells (28) have been described. More details are found in the supplemental materials for drug treatments. We examine loss of expression of targeted protein by western blotting and conduct Mycoplasma testing by PCR during culture routinely, no addition authentication was done by the authors.

Western blotting

Western blotting was carried out as previous described (29). More details on antibodies are found in the supplemental materials.

Real-time reverse transcription PCR

Total RNA was isolated from untreated or drug-treated cells using the Mini –RNA Isolation II Kit (cat#R1055, Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Total RNA (2µg) was used to generate complementary DNA using SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). The following primers were used for PUMA: Forward: 5’-CGACCTCAACGCACAGTACGA-3’, Reverse: 5’-AGGCACCTAATTGGGCTCCAT-3’, β-Actin: Forward: 5’-GACCTCACAGACTACCTCAT-3’, Reverse: 5’-AGACAGCACTGTGTTGGCTA-3’.

Transfection and small-interfering RNA

The gene-specific siRNA, including MET siRNA (30), PUMA siRNA (31) were synthesized by Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO, USA) and transfected into cells with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After 24 hours of transfection, cells were treated with PF02341066 for further analysis. More details are found in the supplemental materials.

Analysis of apoptosis, growth, and mitochondria-associated events

Apoptosis was analyzed by counting cells with condensed chromatin and micronucleation following nuclear staining with Hoechst 33258 (Invitrogen) (27). The methods of colony formation, changes in the mitochondrial membrane potential, and cytochrome c release have been previously described (25, 32) More details are found in the supplemental materials.

Reporter assays

PUMA reporters with or without p53-bindings sites have been described previously (20). Reporter assays were carried out in 12-well plates as described (33). Normalized relative luciferase units were plotted. All reporter experiments were carried out in triplicate and repeated three times.

Xenograft studies

All animal experiments were approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Female 5- to 6-week-old Nu/Nu mice (Charles River, Wilmington, MA, USA) were housed in a sterile environment with micro-isolator cages and allowed access to water and chow ad libitum. Mice were injected subcutaneously in both flanks with 4 million WT or PUMA-KO HCT116 cells. Following tumor growth for 7 days, mice were treated daily by oral gavage for 9 consecutive days with 35 mg/kg PF02341066in 10% ethanol or 10% ethanol without PF02341066 (control buffer), the total volume being approximately 100 µl/mouse. Detailed methods on tumor measurements, harvests and histological analysis are found in the supplemental materials as previously described (34–36).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed in Microsoft Excel. P-values were calculated by the student’s t-test, and were considered significant if P<0.05. The means±1 s.d. are displayed in the figures.

Results

PUMA is induced by crizotinib in colon cancer cells

We first investigated the effects of crizotinib (PF02341066, PF) on MET signaling and PUMA expression in HCT116 colon cancer cells. Crizotinib treatment led to rapid dephosphorylation of MET and AKT without affecting their total levels. However, the levels of phosphorylated ERK only decreased transiently, and recovered within 6 hours (Fig. 1A). PUMA protein and mRNA were induced within 6 hours of treatment, suggesting transcriptional regulation (Fig. 1A and 1B). Interestingly, the expression of Bcl-2 family members, such as Bim and Mcl-1, also increased, while that of Bad, Bid, Bcl-2, and Bcl-xL remained unchanged by 48 hours (Fig. S1A). PUMA induction was dose-dependent and stimulated by as little as 1 µM crizotinib (Fig. 1C). To determine whether MET regulates PUMA expression directly, we depleted MET by siRNA. MET knockdown led to increased PUMA mRNA and protein (Fig. 1D), but not that of Bim (Fig. S1B). Taken together, these data suggest that MET inhibition selectively induce PUMA, whereas crizotinib has a broader effect on the levels of PUMA and other BH3-only proteins.

Figure 1. PUMA was induced by crizotinib in colon cancer cells.

(A) Top, chemical structure of crizotinib (PF02342066). Bottom, HCT116 cells were treated with 12µM crizotinib, or PF02341066 (PF, and thereafter) for indicated time. The expression levels of PUMA, p-Met (T1234/1235), total Met, p-AKT (S473), total AKT, p-ERK (T202/Y204), and total ERK, were analyzed by western blotting. (B) HCT116 cells were treated with 12µM PF02341066 and total RNA was extracted at the indicated time points. PUMA mRNA expression was analyzed by semi-quantitive RT- PCR. β-Actin was used as a control. (C) PUMA protein levels were analyzed by western blotting in HCT116 cells treated with increasing doses of PF02341066 for 24 hours. (D) HCT116 cells were transfected with either a control scrambled siRNA or a Met siRNA for 24 hours. Met and PUMA expression was analyzed by western blotting (left) and Real-time PCR (right). *NS- non-specific band for Bim. *, P < 0.01, MET siRNA “+” vs. “−”. β-Actin was used as a loading control for western blots.

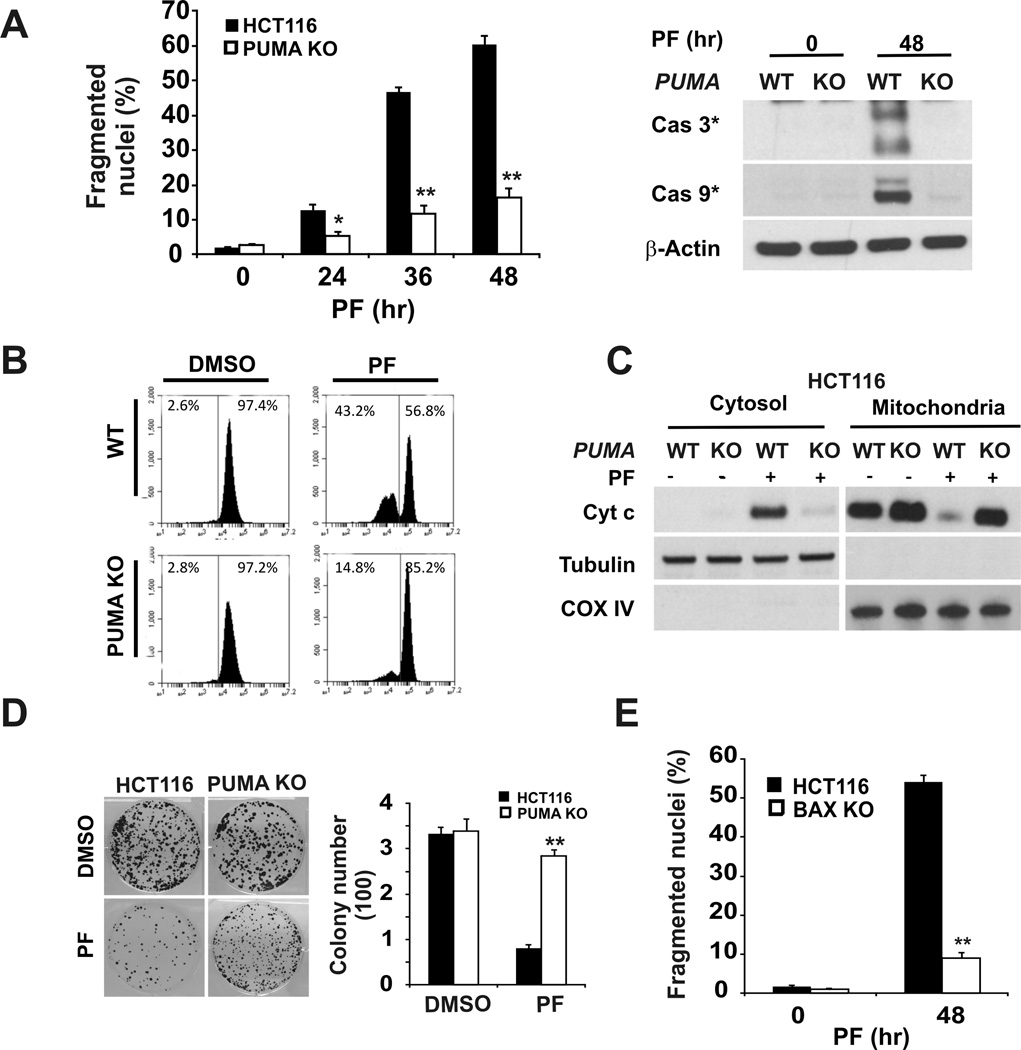

PUMA mediates crizotinib-induced apoptosis

Next we determined the role of PUMA in crizotinib-induced apoptosis using isogenic PUMA-KO HCT116 cells and siRNA. Crizotinib treatment induced ~15% to ~65% apoptosis from 24 to 48 hours in WT HCT116 cells, which was associated with the activation of caspase-3 and caspase-9, mitochondrial membrane depolarization, and cytochrome c release (Fig. 2A and 2B). In contrast, apoptosis in PUMA-KO cells was suppressed by over 70% with little or no activation of caspases, mitochondrial membrane depolarization, or cytochrome c release at 48 hours (Fig. 2A, 2B, and 2C). Annexin V/propidium iodide staining confirmed the apoptotic resistance of PUMA-KO cells (Fig. S2A). Consistent with blocked apoptosis, PUMA-KO cells showed much improved clonogenic survival (Fig. 2D). We have shown previously that PUMA induces Bax-dependent apoptosis (25, 29). As expected, BAX-KO HCT116 cells were also resistant to crizotinib-induced apoptosis (Fig. 2E and Fig. S2B). Transient PUMA knockdown with siRNA also led to reduced apoptosis in HCT116 and LoVo cells following crizotinib treatment (Fig. S2C and S2D). Despite Bim induction, Bim knockdown by siRNA did not render HCT116 cells resistant to crizotinib (Figs. S1B, S2E). Collectively, these results demonstrate an essential role of PUMA and the mitochondrial pathway in crizotinib-induced apoptosis in colon cancer cells.

Figure 2. PUMA is required for the apoptotic activity of crizotinib.

(A) Left, WT and PUMA-KO HCT116 cells were treated with 12µM PF02340166 and harvested at the indicated time points. Apoptosis was analyzed by a nuclear fragmentation assay.*, P < 0.01, **, P < 0.001, WT vs. PUMA-KO. Right, Activation of caspase-3and -9 was analyzed by western blotting in WT and PUMA-KO HCT116 cells treated with 12µM PF02341066 for 48 hours. β-Actin was used as a loading control. (B) WT and PUMA-KO HCT116 cells treated with 12µM PF02341066 for 24 hours were stained with MitoTracker Red CMXRos, and mitochondrial membrane potential was measured by flow cytometry. (C) The cytoplasm and mitochondria were fractionated from WT and PUMA-KO HCT116 cells treated with 12 µM PF02341066 for 36 hours. The distribution of cytochrome c (Cyt c) was analyzed by western blotting. Tubulin and Cytochrome oxidase subunit IV (COX IV) were probed as cytoplamic and mitochondrial fraction controls. (D) WT and PUMA-KO HCT116 cells treated with 12µM PF02340166 for 30 hours were subjected to colony formation assays as described in the materials and methods. Colony numbers were scored 14 days later after plating. Representative pictures of colonies (Left) and quantification of colony numbers (Right) are shown. (E) HCT116 cells and BAX-KO HCT116 cells were treated with 12µM PF02341066 for 48 hours. Apoptosis was determined by a nuclear fragmentation assay. **, P < 0.001, WT vs. PUMA-KO.

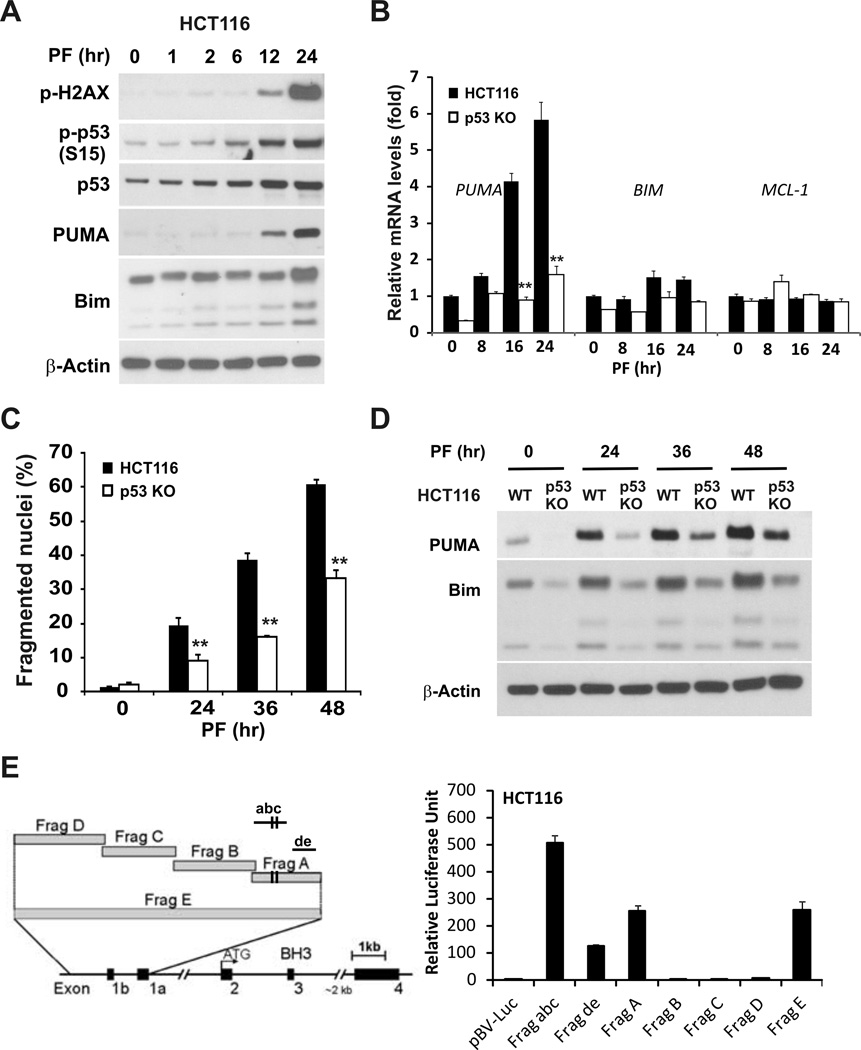

p53-dependent induction of PUMA by crizotinib

Both HCT116 and LoVo cells contain WT p53 gene, and p53 mediates PUMA induction following DNA damage (18). Earlier work suggested that other small molecule MET inhibitors can cause DNA double-strand breaks (37–38). We found that crizotinib treatment resulted in increased phosphorylation of p53 and H2AX, as well as p53 stabilization in HCT116, LoVo and RKO cells, all with WT p53 (Figs. 3A and S3A). Induction of PUMA, and BIM at lower levels, but not MCL-1, was observed in HCT 116 cells and reduced in p53-KO HCT116 cells (Figure 3B). Furthermore, p53 deficiency attenuated crizotinib-induced apoptosis and caspase activation in HCT116 cells (Figs. 3C, S3B), as well as in RKO cells (Fig. S3C and S3D). In time course experiments, PUMA and Bim were induced in HCT116 p53-KO or RKO p53-KO cells after 24 hours, though at much lower levels compared to WT cells (Figs. 3D and S3D). To further investigate p53-dependent activation of PUMA, we used a series of PUMA promoter luciferase reporters (with in ~2 kb) (20), and found that the reporters containing the two p53-binding sites, such as fragments “A”, “abc” and “E”, had high activities after crizotinib treatment (Fig. 3E). Notably, the most proximal fragment “de” (~200 bp), lacking two p53-binding sites, still had a moderate activity (Fig. 3E). The higher activity of the shorter fragment “abc” might be due to the removal of GC-rich sequences and binging sites for transcriptional repressors (18). Together, these data suggest that PUMA induction by crizotinib is mediated by both p53-dependent and -independent mechanisms, and p53 is the major transcriptional activator of PUMA in WT p53 colon cancer cells.

Figure 3. PUMA induction by crizotinib is largely dependent on p53.

(A) HCT116 cells were treated with 12µM PF02340166 for indicated time. The expression levels of p-H2AX (S139), p-p53 (S15), total p53, and PUMA were analyzed by western blotting. (B) PUMA mRNA levels in WT and p53-KO HCT116 cells treated with 12µM PF02341066 at indicated times were determined by real-time RT-PCR. β-Actin was used as the normalized control.**, P < 0.001, WT vs.p53-KO. (C) WT and p53-KO HCT116 cells were treated with 12µM PF02340166 and harvested at indicated time points. Apoptosis was analyzed by a nuclear fragmentation assay. **, P < 0.001, WT vs.p53-KO. (D) PUMA and Bim protein levels in WT and p53-KO HCT116 cells treated with 12µM PF02341066 at the indicated times were analyzed by western blotting. (E) HCT116 cells were transfected with the indicated reporters for 24 hours and subjected to 8 µM PF02341066 treatment for 24 hours. The ratios of normalized relative luciferase activities (to the empty vector pBV-Luc as 1) were plotted. β-Actin was used as a loading control for western blots.

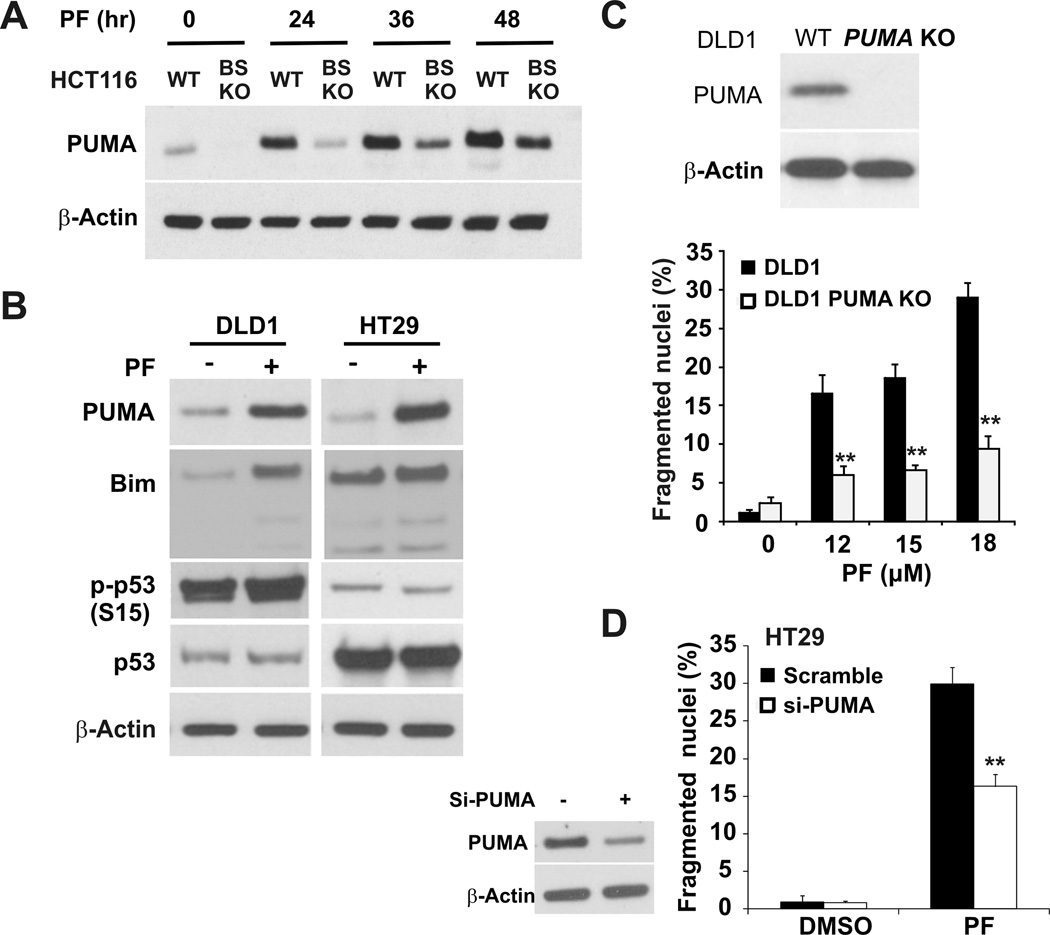

p53-independent induction of PUMA by crizotinib

To further probe p53-independent induction of PUMA, we treated HCT116 cells harboring a deletion of two p53-binding sites in the PUMA promoter (BS-KO) (27) with crizotinib, and found much reduced PUMA induction compared to WT HCT116 cells (Fig. 4A). Moreover, PUMA, but not Bim, was induced by crizotinib in two p53 mutant colon cancer cell lines DLD1 and HT29 in the absence of p53 phosphorylation or stabilization (Fig. 4B). Other transcription factors such as NF-κB subunit p65 and FoxO3a can bind to respective sites located promixal to p53 binding sites in the PUMA promoter. Despite phosphorylation changes associated with activation of p65 and FoxO3a, p65 or FoxO3a knockdown did not affect PUMA induction following crizotinib treatment (Fig. S4). Crizotinib also induced apoptosis in both DLD1 and HT29 cells, which was suppressed by PUMA gene ablation or siRNA (Fig. 4C and 4D). DLD1 cells showed lower PUMA induction and were more resistant to crizotinib- induced apoptosis, compared to HT29 cells (Fig. 4B, 4C and 4D). These results indicate that PUMA plays a critical role in the apoptotic responses to crizotinib in both p53 WT and mutant colon cancer cells.

Figure 4. Crizotinib induces PUMA- and p53-independent apoptosis in colon cancer cells.

(A) PUMA protein levels in WT and BS-KO HCT116 cells treated with 12 µM PF02341066 at the indicated times were analyzed by western blotting. BS-KO HCT116cells harbor the deletion of two p53-binding sites in the PUMA promoter. (B) p53 mutant colon cancer cell lines DLD1 and HT29 were treated with 12µM PF02341066 for 24 hours. The expression levels of PUMA, Bim, p-p53, and total p53 were analyzed by western blotting. (C) Top, PUMA expression was analyzed by western blotting in WT and PUMA -KO DLD1 cells. Bottom, apoptosis was analyzed by nuclear fragmentation in WT and PUMA-KO DLD1 cells treated with the indicated doses of PF02341066 for 48 hours. **, P < 0.001, WT vs.p53-KO. (D) HT29 cells were transfected with either a scrambled siRNA or PUMA siRNA for 24 hours and then treated with 12 µM PF02341066 for 48 hours. Left, western blotting confirmed PUMA depletion by siRNA in HT29 cells. Right, apoptosis was determined by a nuclear fragmentation assay. **, P < 0.001, si-PUMA vs. Scrambled. β-Actin was used as a loading control for western blots.

Crizotinib synergizes with gefitinib or sorafenib to induce apoptosis via PUMA

Cooperative signaling of MET and the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) can contribute to EGFR-TKI resistance (39). HCT116 cells are highly resistant to gefitinib-induced apoptosis or PUMA expression (Fig. 5A and 5B). We therefore hypothesized that the combination of gefitinib and crizotinib might enhance apoptosis. Indeed, this combination induced a much stronger induction of apoptosis, caspase activation, and PUMA and Bim in HCT116 cells, compared to either agent alone (Fig. 5A, 5B and 5C). PUMA-KO cells were highly resistant to apoptosis and long-term growth suppression induced by this combination (Fig. 5A, 5B and 5D). Similarly, crizotinib and erlotinib combination resulted in a strong PUMA-dependent synergy in cell killing (data not shown).

Figure 5. Crizotinib synergizes with gefitinib to induce PUMA-dependent apoptosis in colon cancer cells.

(A) WT and PUMA -KO HCT116 cells were treated with 6µM PF, 20µM gefitinib, or their combination for 48hours. Apoptosis was determined by a nuclear fragmentation assay.**, P< 0.001, “combination” vs. “single agent” in WT cells, and “KO” vs. “WT” in combination. Right, chemical structure of gefitinib. (B) Caspase -3 activation was analyzed by western blotting in WT and PUMA-KO HCT116 cells treated as in A. (C) HCT116 cells were treated with 6µM PF02341066, 20 µM gefitinib, or their combination for 24 hours. The expression levels of p-AKT, total AKT, p-ERK, total ERK, PUMA, and Bim were analyzed by western blotting. (D) WT and PUMA-KO HCT116 cells were treated with 6µM PF02341066, 20µM gefitinib, or their combination for 30 hours and were then subjected to a colony formation assay as described in the materials and methods. Colony numbers were scored 14 days after plating. Representative pictures of colonies (Top) and relative colonogenic survival (bottom) of WT and PUMA-KO HCT116 cells compared to untreated cells are shown.**, P< 0.001, “combination” vs. “single agent” in WT cells, and “KO” vs. “WT” in combination. β-Actin was used as a loading control for western blots.

Crizotinib treatment decreased phosphorylation of both AKT and ERK in HCT116 cells. However, ERK dephosphorylation was only transient and restored after 6 hours, long before apoptosis was detected (Fig. 1A). We reasoned that a more durable inhibition of ERK phosphorylation might potentiate crizotinib in cell killing. The combination of crizotinib and sorafenib, a Raf inhibitor, markedly induced apoptosis, expression of PUMA and Bim, and long-term growth suppression, compared to the single agent (Fig. S5). Apoptosis and long –term growth suppression were attenuated in PUMA-KO cells (Figs. S5A, 5B and 5D). Of note, AKT phosphorylation was completely inhibited by all three agents, but not ERK phosphorylation, and reduction of either p-AKT or p-ERK is not sufficient for the enhanced induction of PUMA and Bim, or apoptosis in the combination treatments (Figs. 5C and S5C). In addition, Mcl-1 levels did not change or decreased following crizotinib combination with gefitinib or sorafinib (Figs. 5C and S5C). These results suggest that the combinations of crizotinib with additional TKIs are required to effectively target non-overlapping survival pathways in cancer cells to induce apoptosis.

PUMA contributes to the anti-tumor activity of crizotinib in a mouse xenograft model

To determine whether PUMA-mediated apoptosis plays a critical role in the anti-tumor activity of crizotinib in vivo, we established WT and PUMA-KO HCT116 xenograft tumors in the flanks of BALB/c (nu/nu) nude mice. Tumors of different genotypes were established on the opposite flanks of the same mice to minimize inter-mouse variations in tumor uptake or drug delivery. Crizotinib was administered orally to tumor-bearing mice daily for 10 days, and tumor volumes were monitored every two days for 3 weeks. Compared to the buffer, crizotinib reduced growth of WT tumors by 81%, and PUMA -KO tumors by 41% (Fig. 6A and 6B). Increased phospho-p53, PUMA and Bim expression was evident in WT tumors at day 5 of treatment (Fig. 6C). TUNEL and active caspase-3 staining revealed marked apoptosis in WT tumor tissues from crizotinib-treated mice, which decreased by over 60% in the PUMA-KO tumors (Fig. 6D and 6E). These results demonstrate that the anti-tumor activity of crizotinib in vivo is also dependent on the p53/PUMA axis.

Figure 6. PUMA mediates the anti-tumor effects of crizotinib in a xenograft model.

(A) Nude mice with established WT or PUMA-KO HCT116 xenografts were treated with 35 mg/kg PF02341066 or buffer for ten consecutive days. Tumor volume at the indicated time points was calculated and plotted. Arrows indicate PF02341066 administration. Statistical significance is indicated for the comparison of PF02341066-treated WT and PUMA-KO tumors. (B) Representative tumors at the end of the experiment in A. (C) WT and PUMA-KO HCT116 xenograft tumors were harvested from two mice as in A after 5 treatments. p-p53, PUMA, and Bim expression in representative WT HCT116 tumors was analyzed by western blotting. β-Actin was used as a loading control. Representative data are shown. (D) TUNEL and active caspase -3 staining of tumor sections as harvested in C. (E) Quantitation of TUNEL or active caspase -3 positive cells in D. Results of D and E were expressed as means±s.d. N=3 tumors of each genotype.

Discussion

Aberrantly activated oncogenic kinases are promising drug targets for small molecules, however biomarkers and resistance mechanisms of most clinically useful kinase inhibitors remain largely unknown. Crizotinib has been approved in ALK-rearranged NSCLC (3, 13), and clinical interest is expanding to other solid tumors with genetic alterations in c-MET, ALK and ROS-1 (14, 40). The anti-tumor activities of crizotinib include the induction of cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, and inhibition of cell proliferation and invasion (3, 13). Our results indicated that activation of mitochondrial pathway and PUMA plays a key role in crizotinib-induced cancer cell death in vitro and in vivo. In addition, the combinations of crizotinib with EGFR or Raf inhibitors resulted in the potent induction of apoptosis in colon cancer cells via PUMA.

Crizotinib-induced apoptosis can be attributed to Bim in lung cancer cells with MET amplification but not with MET mutations (41–42). In colon cancer cells, Bim induction, though not required, likely potentiates PUMA-dependent apoptosis by antagonizing anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins including Mcl-1, whose levels remain high after treatment. It is likely that multiple BH3-only proteins are employed in the apoptotic response to crizotinib, while a distinct member might serve as cell or tissue-specific initiator. The co-regulation of Bim and PUMA by crizotinib is interesting and somewhat unexpected, and requires further investigation. Bim and PUMA are located on different chromosomes and their basal expression levels are quite different. It is possible that higher-order chromatin changes might be involved in addition to loading of stress-induced transcription factors such as p53 onto their promoters. The mechanisms of MET inhibitor-induced DNA damage response (37–38), and p53-independent induction of PUMA and Bim remain unclear.

Despite a plethora of oncogenic activities ascribed to MET and its related kinases (3, 13), our data suggest that crizotinib effectively inhibits MET signaling, and induces PUMA-dependent apoptosis in colon cancer cells. Surprisingly, MET siRNA did not induce obvious apoptosis or p53 stabilization in HCT116 cells but only a modest PUMA induction. One possible explanation is that crizotinib treatment is more effective in blocking MET signaling than MET siRNA. Another more likely explanation is that crizotinib inhibits other RTKs and activates p53-dependent DNA damage responses in some cells. In addition, PUMA induction might further engage cytoplasmic function of p53 to trigger apoptosis (43–44). These issues might be relevant as the clinically efficacious concentration of crizotinib used in vitro for cell killing (1–10 µM) are much higher than those required to selectively inhibit MET or ALK.

Crizotinib and other TKI combinations enhance apoptosis and the induction of PUMA and Bim. Interestingly, the inhibition of AKT phosphorylation is not sufficient for cell killing or strong PUMA induction. Our data are consistent with the emerging concept that crosstalk between RTKs is a major mechanism for cancer progression and therapeutic resistance, and successful therapy will likely require targeting multiple survival pathways (1, 6, 45). However, several challenges are facing the clinical applications of kinase inhibitors:1) Genetic alterations in EGFR, MET, or ALK, and possibly ROS1 are infrequent, 2) not all tumors with same alterations respond, 3) tumor heterogeneity plus preexisting or de novo mutations in targets can lead to rapid development of resistance. Therefore, it is important to identify effective combination therapies that target several survival mechanisms in cancer cells to prevent the development of resistance. Our data suggest the combination of crizotinib with other TKIs effectively block MET signaling and alternative survival pathways in colon cancer cells. The cell lines used in this study are not expected to contain ALK or ROS1 rearrangements, while the mechanisms described warrant further investigation in this context in relevant cancers.

In conclusion, our study provides a novel anti-tumor mechanism of crizotinib via PUMA-mediated apoptosis through both p53-dependent and -independent means. These findings are in line with other recent findings in which PUMA or Bim mediates the apoptotic response to various kinase inhibitors. Therefore, induction of PUMA and Bim may be a predictor for a favorable response to crizotinib, and possibly other targeted agents or their combinations. This concept is different from using genetic alterations or steady-state mRNA or protein levels in the tumors, and measures a dynamic response that might well be cell- type or patient-specific (36). Since induction of PUMA and apoptosis is significantly more robust in p53 WT cells, it would be useful to determine whether crizotinib shows selectivity against p53 WT cancers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Bert Vogelstein (Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Johns Hopkins University) for p53-KO HCT116 and p53-KO RKO cells, and other members of Yu and Zhang laboratories for helpful discussions. This work is supported by NIH grant CA129829, American Cancer Society grant RGS-10-124-01-CCE, FAMRI (J Yu), and by NIH grants CA106348, CA121105, and American Cancer Society grant RSG-07-156-01-CNE (L Zhang). This project used the UPCI shared facilities that were supported in part by award P30CA047904.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts to disclose. All author agreed on the submission.

Author contributions:

JY conceived the study.

XZ, KE, and JY designed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the paper.

XZ and KE performed experiments.

LZ designed experiments and contributed key reagents.

References

- 1.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gschwind A, Fischer OM, Ullrich A. The discovery of receptor tyrosine kinases: targets for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:361–370. doi: 10.1038/nrc1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Comoglio PM, Giordano S, Trusolino L. Drug development of MET inhibitors: targeting oncogene addiction and expedience. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:504–516. doi: 10.1038/nrd2530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Di Renzo MF, Olivero M, Giacomini A, Porte H, Chastre E, Mirossay L, et al. Overexpression and amplification of the met/HGF receptor gene during the progression of colorectal cancer. Clinical Cancer Research. 1995;1:147–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takeuchi H, Bilchik A, Saha S, Turner R, Wiese D, Tanaka M, et al. c-MET Expression Level in Primary Colon Cancer. Clinical Cancer Research. 2003;9:1480–1488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hait WN, Hambley TW. Targeted cancer therapeutics. Cancer Res. 2009;69:1263–1267. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3836. discussion 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jin H, Yang R, Zheng Z, Romero M, Ross J, Bou-Reslan H, et al. MetMAb, the One-Armed 5D5 Anti-c-Met Antibody, Inhibits Orthotopic Pancreatic Tumor Growth and Improves Survival. Cancer Research. 2008;68:4360–4368. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Munshi N, Jeay Sb, Li Y, Chen C-R, France DS, Ashwell MA, et al. ARQ 197, a Novel and Selective Inhibitor of the Human c-Met Receptor Tyrosine Kinase with Antitumor Activity. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 2010;9:1544–1553. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu X, Wang Q, Yang G, Marando C, Koblish HK, Hall LM, et al. A novel kinase inhibitor, INCB28060, blocks c-MET-dependent signaling, neoplastic activities, and cross-talk with EGFR and HER-3. Clinical Cancer Research. 2011;17:7127–7138. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zou HY, Li Q, Lee JH, Arango ME, McDonnell SR, Yamazaki S, et al. An Orally Available Small-Molecule Inhibitor of c-Met, PF-2341066, Exhibits Cytoreductive Antitumor Efficacy through Antiproliferative and Antiangiogenic Mechanisms. Cancer Research. 2007;67:4408–4417. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bergethon K, Shaw AT, Ignatius Ou S-H, Katayama R, Lovly CM, McDonald NT, et al. ROS1 Rearrangements Define a Unique Molecular Class of Lung Cancers. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30:863–870. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.6345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Christensen JG, Zou HY, Arango ME, Li Q, Lee JH, McDonnell SR, et al. Cytoreductive antitumor activity of PF-2341066, a novel inhibitor of anaplastic lymphoma kinase and c-Met, in experimental models of anaplastic large-cell lymphoma. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 2007;6:3314–3322. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ou SH. Crizotinib: a novel and first-in-class multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor for the treatment of anaplastic lymphoma kinase rearranged non-small cell lung cancer and beyond. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2011;5:471–485. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S19045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stumpfova M, Jänne PA. Zeroing in on ROS1 Rearrangements in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Clinical Cancer Research. 2012;18:4222–4224. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adams JM, Cory S. The Bcl-2 apoptotic switch in cancer development and therapy. Oncogene. 2007;26:1324–1337. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu J, Zhang L. Apoptosis in human cancer cells. Curr Opin Oncol. 2004;16:19–24. doi: 10.1097/00001622-200401000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leibowitz B, Yu J. Mitochondrial signaling in cell death via the Bcl-2 family. Cancer Biol Ther. 2010;9:417–422. doi: 10.4161/cbt.9.6.11392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu J, Zhang L. PUMA, a potent killer with or without p53. Oncogene. 2008;27:S71–S83. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Melino G, Bernassola F, Ranalli M, Yee K, Zong WX, Corazzari M, et al. p73 Induces Apoptosis via PUMA Transactivation and Bax Mitochondrial Translocation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279:8076–8083. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307469200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ming L, Sakaida T, Yue W, Jha A, Zhang L, Yu J. Sp1 and p73 activate PUMA following serum starvation. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:1878–1884. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.You H, Pellegrini M, Tsuchihara K, Yamamoto K, Hacker G, Erlacher M, et al. FOXO3a-dependent regulation of Puma in response to cytokine/growth factor withdrawal. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2006;203:1657–1663. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dudgeon C, Wang P, Sun X, Peng R, Sun Q, Yu J, et al. PUMA induction by FoxO3a mediates the anticancer activities of the broad-range kinase inhibitor UCN-01. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9:2893–2902. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang P, Qiu W, Dudgeon C, Liu H, Huang C, Zambetti GP, et al. PUMA is directly activated by NF-[kappa]B and contributes to TNF-[alpha]-induced apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2009;16:1192–1202. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dudgeon C, Peng R, Wang P, Sebastiani A, Yu J, Zhang L. Inhibiting oncogenic signaling by sorafenib activates PUMA via GSK3[beta] and NF-[kappa]B to suppress tumor cell growth. Oncogene. 2012 doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu J, Wang Z, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Zhang L. PUMA mediates the apoptotic response to p53 in colorectal cancer cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2003;100:1931–1936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2627984100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bunz F, Hwang PM, Torrance C, Waldman T, Zhang Y, Dillehay L, et al. Disruption of p53 in human cancer cells alters the responses to therapeutic agents. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:263–269. doi: 10.1172/JCI6863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang P, Yu J, Zhang L. The nuclear function of p53 is required for PUMA-mediated apoptosis induced by DNA damage. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2007;104:4054–4059. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700020104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bunz F. Human cell knockouts. Curr Opin Oncol. 2002;14:73–78. doi: 10.1097/00001622-200201000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ming L, Wang P, Bank A, Yu J, Zhang L. PUMA Dissociates Bax and Bcl-XL to Induce Apoptosis in Colon Cancer Cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281:16034–16042. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513587200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fornari F, Milazzo M, Chieco P, Negrini M, Calin GA, Grazi GL, et al. MiR-199a-3p Regulates mTOR and c-Met to Influence the Doxorubicin Sensitivity of Human Hepatocarcinoma Cells. Cancer Research. 2010;70:5184–5193. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Han J, Goldstein LA, Gastman BR, Rabinowich H. Interrelated Roles for Mcl-1 and BIM in Regulation of TRAIL-mediated Mitochondrial Apoptosis. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281:10153–10163. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510349200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yu J, Wang P, Ming L, Wood MA, Zhang L. SMAC//Diablo mediates the proapoptotic function of PUMA by regulating PUMA-induced mitochondrial events. Oncogene. 2007;26:4189–4198. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yu J, Zhang L, Hwang PM, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. PUMA Induces the Rapid Apoptosis of Colorectal Cancer Cells. Molecular Cell. 2001;7:673–682. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00213-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qiu W, Carson-Walter EB, Liu H, Epperly M, Greenberger JS, Zambetti GP, et al. PUMA Regulates Intestinal Progenitor Cell Radiosensitivity and Gastrointestinal Syndrome. Cell stem cell. 2008;2:576–583. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leibowitz BJ, Qiu W, Liu H, Cheng T, Zhang L, Yu J. Uncoupling p53 Functions in Radiation-Induced Intestinal Damage via PUMA and p21. Mol Cancer Res. 2011;9:616–625. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-11-0052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sun J, Sun Q, Brown MF, Dudgeon C, Chandler J, Xu X, et al. The Multi-Targeted Kinase Inhibitor Sunitinib Induces Apoptosis in Colon Cancer Cells via PUMA. PLoS One. 2012;7:e43158. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Medova M, Aebersold DM, Blank-Liss W, Streit B, Medo M, Aebi S, et al. MET Inhibition Results in DNA Breaks and Synergistically Sensitizes Tumor Cells to DNA-Damaging Agents Potentially by Breaching a Damage-Induced Checkpoint Arrest. Genes Cancer. 2010;1:1053–1062. doi: 10.1177/1947601910388030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ganapathipillai SS, Medova M, Aebersold DM, Manley PW, Berthou S, Streit B, et al. Coupling of mutated Met variants to DNA repair via Abl and Rad51. Cancer Res. 2008;68:5769–5777. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Engelman JA, Zejnullahu K, Mitsudomi T, Song Y, Hyland C, Park JO, et al. MET Amplification Leads to Gefitinib Resistance in Lung Cancer by Activating ERBB3 Signaling. Science. 2007;316:1039–1043. doi: 10.1126/science.1141478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yauch RL, Settleman J. Recent advances in pathway-targeted cancer drug therapies emerging from cancer genome analysis. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2012;22:45–49. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2012.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Okamoto W, Okamoto I, Arao T, Kuwata K, Hatashita E, Yamaguchi H, et al. Antitumor Action of the MET Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Crizotinib (PF-02341066) in Gastric Cancer Positive for MET Amplification. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 2012;11:1557–1564. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tanizaki J, Okamoto I, Okamoto K, Takezawa K, Kuwata K, Yamaguchi H, et al. MET Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Crizotinib (PF-02341066) Shows Differential Antitumor Effects in Non-small Cell Lung Cancer According to MET Alterations. Journal of Thoracic Oncology. 2011;6:1624–31. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31822591e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chipuk JE, Bouchier-Hayes L, Kuwana T, Newmeyer DD, Green DR. PUMA couples the nuclear and cytoplasmic proapoptotic function of p53. Science. 2005;309:1732–1735. doi: 10.1126/science.1114297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chipuk JE, Green DR. How do BCL-2 proteins induce mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization? Trends Cell Biol. 2008;18:157–164. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dent P, Curiel DT, Fisher PB, Grant S. Synergistic combinations of signaling pathway inhibitors: mechanisms for improved cancer therapy. Drug Resist Updat. 2009;12:65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.