Abstract

Purpose

To determine the safety of fluconazole in neonates and other paediatric age groups by identifying adverse events (AEs) and drug interactions associated with treatment.

Methods

A search of EMBASE (1950–January 2012), MEDLINE (1946–January 2012), the Cochrane database for systematic reviews and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (1982–2012) for any clinical study about fluconazole use that involved at least one paediatric patient (≤17 years) was performed. Only articles with sufficient quality of safety reporting after patients’ exposure to fluconazole were included.

Results

We identified 90 articles, reporting on 4,209 patients, which met our inclusion criteria. In total, 794 AEs from 35 studies were recorded, with hepatotoxicity accounting for 378 (47.6 %) of all AEs. When fluconazole was compared with placebo and other antifungals, the relative risk (RR) of hepatotoxicity was not statistically different [RR 1.36, 95 % confidence interval (CI) 0.87–2.14, P = 0.175 and RR 1.43, 95 % CI 0.67–3.03, P = 0.352, respectively]. Complete resolution of hepatoxicity was achieved by 84 % of patients with follow-up available. There was no statistical difference in the risk of gastrointestinal events of fluconazole compared with placebo and other antifungals (RR 0.81, 95 % CI 0.12–5.60, P = 0.831 and RR 1.23, 95 %CI 0.87–1.71, P = 0.235, respectively). There were 41 drug withdrawals, 17 (42 %) of which were due to elevated liver enzymes. Five reports of drug interactions occurred in children.

Conclusion

Fluconazole is relatively safe for paediatric patients. Hepatotoxicity and gastrointestinal toxicity are the most common adverse events. It is important to be aware that drug interactions with fluconazole can result in significant toxicity.

Keywords: Fluconazole, Safety, Neonates, Paediatrics, Hepatotoxicity

Background

Invasive candidiasis is associated with high morbidity and mortality in neonates and children, with the highest incidence in premature neonates. Studies in neonates have shown an incidence rate of 2–28 % depending on birth weight [1]. Amphotericin B is the drug of choice for the treatment of invasive candidiasis; however, nephrotoxicity has been associated with this drug [2]. Fluconazole remains a suitable alternative and has also been used routinely as prophylaxis for very low birth weight neonates and children with other risk factors. Risk factors in neonates include prematurity, broad spectrum antibiotics, central venous catheter, mechanical ventilation, use of H2 receptor antagonists and parenteral nutrition. Immunosuppression from endogenous or exogenous causes, such as cystic fibrosis, malignancy, drug therapy (cytotoxics, corticosteroids, immunosuppressives), haematological diseases, organ or bone marrow transplantation and prolonged intensive care, are factors in paediatric patients beyond the neonatal period [3, 4].

Fluconazole, a bis-triazole broad spectrum antifungal agent discovered by Richardson et al. during a programme initiated by Pfizer Central Research in 1978 [5], is a suitable alternative to amphotericin B. It is available as an oral tablet, oral suspension and intravenous formulation. Its antifungal activity is achieved by preventing fungal membrane sterol synthesis through the inhibition of cytochrome P450 (CYP)-dependent lanosterol C-14α-demethylase conversion of lanosterol to ergosterol, resulting in an impairment of fungal cell replication. Although CYP is also present in mammalian cells, fluconazole is highly selective for fungal CYP [6, 7].

Fluconazole is well absorbed orally with extensive bioavailability, and most of the drug is excreted unchanged in the urine; only 11 % is excreted as metabolites, while a small percentage is excreted in the faeces. The elimination half-life of the drug is about 30 h (range 20–50 h), with a faster rate of elimination in older children than adults. In neonates, however, the mean plasma elimination half-life is longer (55–90 h) [8–10].

Fluconazole is licensed in children for mucosal candidiasis, invasive candidiasis and prophylaxis against candidal infections in immunocompromised patients. Common adverse reactions ascribed to the drug from clinical trials include deranged liver enzymes, cholestasis, headache, skin rash and gastrointestinal symptoms [11].

Due to the increasing use of the drug as prophylaxis and for the treatment of fungal infections in paediatric and neonatal patients, as well the need to identify toxicity associated with treatment, we decided to undertake a systematic review of safety data published on fluconazole in these populations.

Method

Search strategy

We searched MEDLINE (1946–January 2012), EMBASE (1950–January 2012), the Cochrane database for systematic reviews, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL1982–January 2012) and the Cochrane library (Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Cochrane database of systematic reviews, and Database of abstracts of reviews of effects) for any clinical study about fluconazole use that involved at least one paediatric patient (≤17 years). Any study with involvement of a paediatric age group participant taking at least a single dose of fluconazole was eligible. Only studies with a report of safety after exposure to fluconazole in the paediatric patients were included. There was no restriction on the language of publication of the articles as translations to extract relevant data were done; where translations were not possible, abstracts containing relevant data were used. Also included in this review were any clinical study, whether comparative or non-comparative, randomised controlled trials (RCTs) or case reports and also letters to the editors that documented exposure of a paediatric patient to fluconazole and reported on safety. Included articles and extracted data were validated by two reviewers. Search terms comprised free text words and subject headings. These included terms relating to azole or imidazole or fluconazole, adverse effects or adverse drug reactions or side effects, pharmacokinetics and drug interactions.

Data extraction

Data extracted from each study included the year of publication, type of study, number of paediatric patients exposed, age of paediatric patients exposed, doses of fluconazole used, route of administration and safety data. The safety data extracted were occurrence of any adverse event (AE), any drug interactions, any withdrawal due to AEs and any drug-related death.

Data quality assessment

To minimise the risk of bias, we assessed the quality of included RCTs using the CONSORT checklist for reporting of harm [12]. All RCTs with scores of ≥6 out of nine criteria were considered to provide good quality safety reporting. Cohort studies were scored using the STROBE checklist [13], where a score of >70 % is considered to be good. Case series were evaluated using the health technology assessment checklist [14], and all studies fulfilling the good or satisfactory criteria were included.

Data collection

The relevant data were extracted onto the data extraction form. Participants in the study were grouped into paediatric age groups of preterm neonates (<36 weeks gestation, 0–27 days), full-term neonates (0–27 days, >37 weeks gestation), infants and toddlers (28 days–23 months), children (2–11 years) and adolescents (12–17 years). All reported AEs were pooled together from the various studies. The duration of treatment was grouped into <21, 21–42 and >42 days; the treatment dose was grouped into <3, 3–6 and >6 mg/kg; the route of administration was recorded as intravenous (IV), oral or IV and oral.

Statistical analysis

Meta-analysis was performed using the Stata/IC v.11 statistical package (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). Only those studies rated as good were included in the meta-analysis. Studies with zero frequency were included in the meta-analysis by entering 0.5 to zero cells so that all of the information could be used.

The relative risk (RR) was calculated for these binary outcomes (RR >1 indicates a positive effect of fluconazole). We calculated the pooled relative risks with fixed effect models using the Mantel and Haenszel method. The heterogeneity of the model was examined by calculating the DerSimonian and Laird’s Q statistic [15] and the I2-statistic [16]. Both were compared with a chi-square distribution with degrees of freedom (df) equal to the number of trials minus one. We used the Q statistic for testing the presence of heterogeneity and the I2-statistic for estimating the degree of heterogeneity. When heterogeneity was observed, we used the with random effect models as suggested by DerSimonian and Laird [15].

The forest plots have been created for presenting the pooled effects of fluconazole. The effects of indication, age groups, dose range, route of administration and duration of treatment on risk of AEs in the fluconazole groups against the active comparator were assessed using random effect models.

Poisson regression analysis was used to test the effect of indication, age groups, dose groups, route of administration and duration of treatment on incidence of AEs and hepatotoxicity in the fluconazole group. The incidence–rate ratios (IRR) are reported from the Poisson regression analysis. All results are reported with 95 % confidence intervals (CIs), and all P values are two-tailed.

Results

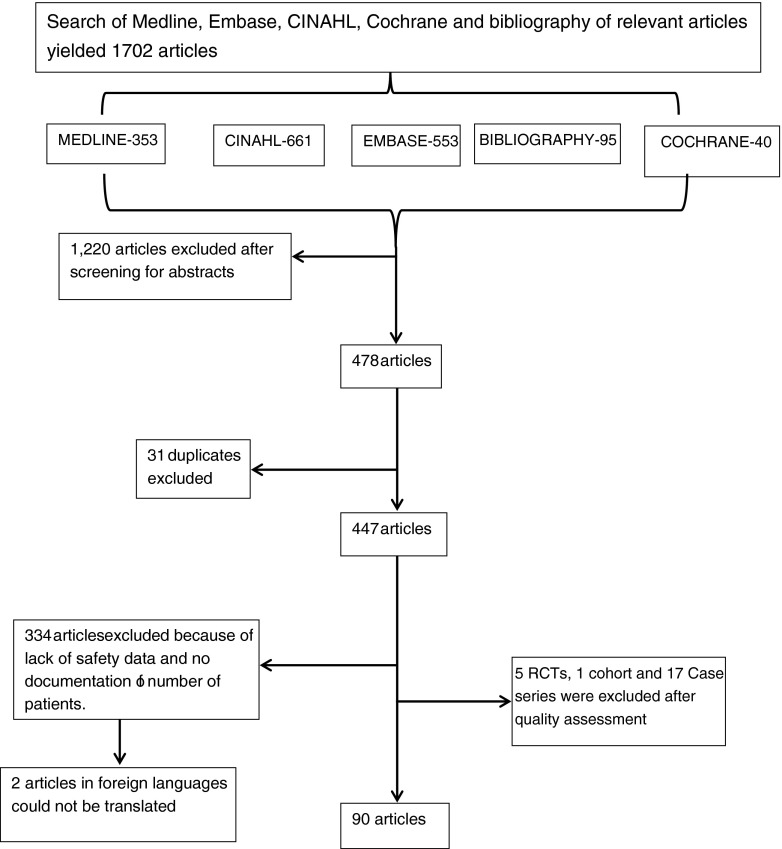

Our search revealed 1,702 articles, of which 117 met our inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). These were reduced to 90 following assessment of data quality. Two articles in foreign languages (Chinese and Hebrew) were excluded because the articles could not be translated. All 90 articles were published between 1986 and 2011, and the most frequent type of studies was the case report, followed by the case series and the RCT (Table 1). Thirty-one (34 %) of the studies involved neonates only.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart for articles included in the systematic review. CINAIL Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, RCTs randomised controlled trials

Table 1.

Summary of the 90 studies that reported on the safety of fluconazole in paediatric populations included in this review

| Characteristics of studies | Number of studies | Number of patients |

|---|---|---|

| Type of study | n = 90 | n = 4,209 |

| Case series | 23 | 795 |

| Case reports | 38 | 65 |

| RCT | 14 | 1,793 |

| Cohort studies | 7 | 1,564 |

| Pharmacokinetics studies | 8 | 77 |

| Route of Administration | n = 90 | n = 4,209 |

| Oral | 27 | 1,465 |

| Intravenous and oral | 26 | 1,602 |

| Intravenous | 21 | 971 |

| Not reported | 13 | 170 |

| Intraperitoneal/rectal | 3 | 15 |

| Age groups | n = 90 | n = 4,209 |

| Preterm neonates | 20 | 2,354 |

| Term neonates | 7 | 43 |

| Term and preterm neonates | 4 | 37 |

| Other paediatric age groupsa | 59 | 1,775 |

RCT, Randomised controlled trial

aIncluding studies involving infants up to adolescence (some of which included some neonates) and paediatric studies for which the age group was not stated

The largest group of patients who received fluconazole were taking part in RCTs (1,793 patients). These studies compared fluconazole with griseofulvin, placebo, nystatin, amphotericin B and other azole antifungals. One study compared different routes of administration [17]. Seven of the 14 RCTs were exclusively conducted in neonates (term and preterm) [17–23], while the remainder involved children across the paediatric age spectrum (birth–17 years) [24–31]. Fluconazole was used as prophylaxis in six of the eight neonatal RCTs.

The second largest group of patients on fluconazole (1,564) were enrolled in cohort studies [32–38]. All cohort study patients were preterm neonates, with fluconazole administered either prophylactically orally or intravenously. The other large group of patients (795) were in case series [39–59]. Fifteen of these studies were conducted in term and preterm neonates, while the others cut across the paediatric age group. Seventy-seven patients were involved in eight pharmacokinetic studies [60–67], three of which were performed exclusively in preterm and term neonates.

Dosage and administration

Fluconazole was either administered as prophylaxis or therapeutically. The median prophylactic dose was 3 mg/kg/day [interquartile range (IQR) 3–6 mg/kg/day] over a median period of 42 days (IQR 1.57–42 days). The median administered therapeutic dose was 6 mg/kg/day (IQR 5–6 mg/kg/day) over a median duration of 42 days (IQR 14–67 days). Therapeutic indications were invasive candidiasis, taenia capitis, fungal meningitis, urinary tract infection and other mycotic infections. The duration of treatment ranged between 1 day [40–42] and 9 years [68]. The most common routes of administration were oral (30 %), IV (23 %) or both (28 %) (Table 1).

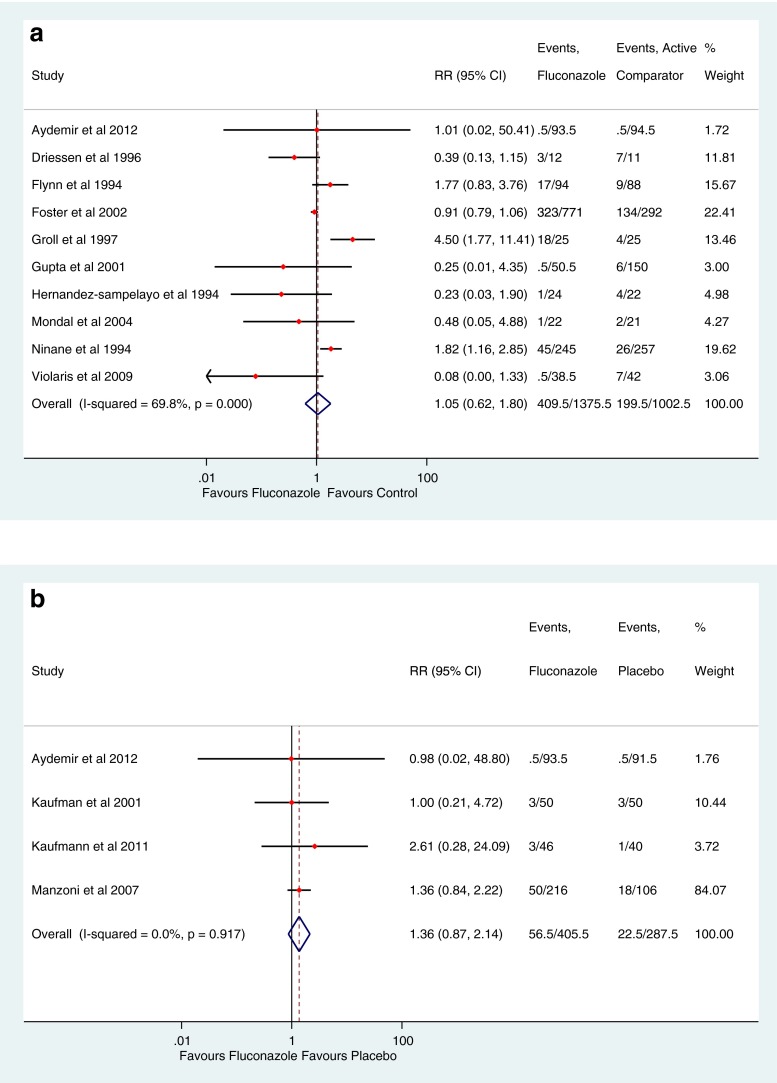

Toxicity

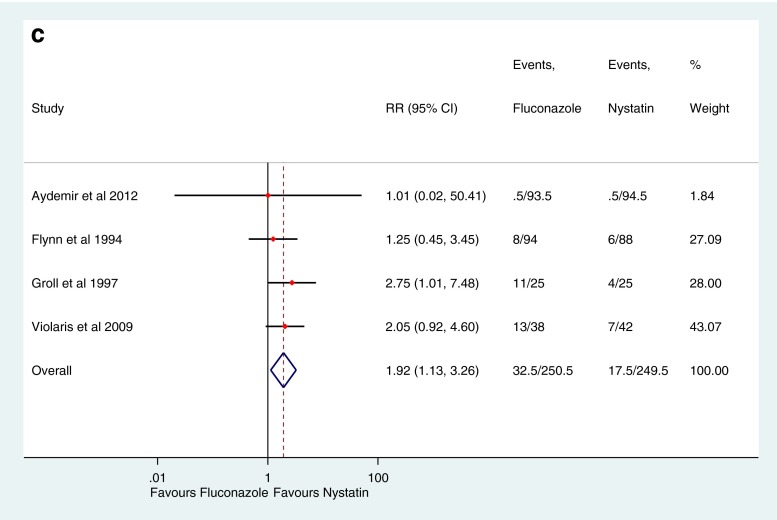

A total of 4,209 patients from 90 studies were exposed to fluconazole, with 794 AEs recorded in 35 studies. Hepatotoxicity was the most common AE across all age groups. About one-third of the reviewed articles exclusively involved preterm and term neonates, accounting for 2,434 fluconazole exposed neonates. A total of 307 AEs (38.6 %) were recorded in neonates, of which 295 (96.1 %) were hepatotoxic effects. Gastrointestinal events were the second most common AE documented. One hundred cases of respiratory symptoms were recorded in one study, none of which was found to be drug-related. Other adverse events identified were renal dysfunction, haematological abnormalities and rash (Table 2). The relative risk of all AEs in the fluconazole group was not statistically different from those treated with placebo (RR 1.30, 95 % CI 0.84–2.03, P = 0.238). Compared to all other antifungal drugs there was again no significant increase in the risk (RR 1.05, 95 % CI 0.62–1.80, P = 0.85) (Fig. 2a). The overall relative risk of adverse events in the fluconazole group was not significantly different within the treatment group (RR 0.82, 95 % CI 0.49–1.36, P = 0.437) or the prophylaxis group (RR 1.68, 95 % CI 0.55–5.11, P = 0.364) compared to other antifungal drugs. There were 378 recorded cases of hepatotoxicity, accounting for just under half of all the AEs across all age groups. The majority of cases (295) occurred in neonates. The relative risk of hepatotoxicity with fluconazole was 1.36 (95 % CI 0.87–2.14) and 1.43 (95 % CI 0.67–3.03) when compared with placebo and other antifungals, respectively (Fig. 2a and 2b); these relationships were not statistically significant (P = 0.175 and 0.352, respectively). However, when compared against nystatin, the only comparator to have sufficient numbers of patients for analysis, there was a significant increase in risk of hepatotoxicity with fluconazole (RR 1.92, 95 % CI 1.13–3.26, P = 0.016) (Fig. 2c).

Table 2.

Reported adverse events from 35 studies

| Adverse events | Preterm neonates only | Term and preterm neonates | Infancy–adolescence | Othersa | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conjugated bilirubin | 231 | 4 | 1 | – | 236 |

| ↑Liver enzymes | 55 | 13 | 47 | 16 | 131 |

| Respiratory infectionb | – | – | 100 | – | 100 |

| GIT symptomsc | – | – | 55 | – | 55 |

| Headache | – | – | 24 | – | 24 |

| Vomiting | – | 1 | 20 | 1 | 22 |

| Abdominal pain | – | – | 18 | – | 18 |

| Other skin conditions | – | – | 21 | – | 21 |

| Rash/urticarial | – | – | 19 | – | 19 |

| Diarrhoea | – | – | 16 | 1 | 17 |

| Nausea | – | – | 10 | – | 10 |

| Eosinophilia | – | 6 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Altered renal function | – | 3 | 4 | – | 7 |

| Electrolyte derangement | 2 | – | – | – | 2 |

| Pruritus | – | – | 6 | – | 6 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 5 | – | – | – | 5 |

| Anaemia | – | 2 | – | – | 2 |

| Others | – | – | 109 | 2 | 111 |

| Total | 293 | 29 | 451 | 21 | 794 |

GIT, Gastrointestinal tract

aNumber of adverse events (AEs) cut across age categories

bObtained from a single study

cPatients with anorexia, gastritis, dyspepsia, GI upset or a combination of any of nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea and abdominal pain

Fig. 2.

a Fluconazole adverse effects (AEs) compared to those of other antifungals. b Fluconazole hepatotoxicity compared with that of placebo. c Fluconazole hepatotoxicity compared with that of nystatin

Poisson regression analysis of the effect of treatment, age group, dose, route of administration, indication and duration of treatment on the incidence of hepatotoxicity of fluconazole was performed. This showed that the incidence of hepatotoxicity with therapeutic fluconazole was significantly greater than that with prophylaxis (IRR 5.34 95 % CI 1.99–14.37, P = 0.001), while the duration of treatment had no effect. Although the incidence of hepatotoxicity in neonates on fluconazole was greater than that in children (IRR 1.33, 95 % CI 0.63–2.80), this effect was not statistically significant (P = 0.451). The incidence of hepatotoxicity appears to decrease with increasing dose (IRR 0.52, 95 % CI 0.37–0.74, P = 0.001). Patients on oral fluconazole were less likely to have hepatotoxicity than those on IV fluconazole (IRR 0.21, 95 % CI 0.92–0.47, P = 0.001).

Only three of the cohort studies reported any AE; one of which was a prophylactic study which recorded 127 cases of cholestasis in 409 fluconazole-exposed extremely low birth weight neonates. However, this study did not report the number of non-exposed neonates. Of these patients, 69 % recovered, while the others were discharged or transferred to other facilities [36]. Another prophylactic cohort study recorded 60 cases of cholestasis in 140 fluconazole-exposed extremely low birth weight neonates as against 12 in 137 non-exposed neonates (P < 0.001) [34].

Of all the 378 hepatotoxicity cases, resolution of symptoms was not determined in 113 (30 %) cases, while in 42 (11 %) cases, all involving neonates, there was no improvement at discharge or upon referral to another hospital (188 neonates and 35 children had completely recovered during treatment or shortly after). Therefore, 84 % of patients, for whom follow-up was complete, had resolution of symptoms. Hepatotoxicity was the most frequent reason for withdrawal of the drug. Of the 41 drug-related withdrawals,17 (42 %) were due to elevated liver enzymes [26, 27, 30, 36, 42, 66, 69].

Gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms including nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhoea, dyspepsia, anorexia and gastritis accounted for 15.4 % of AEs (122 cases) (Table 2). There was only one recorded case of GI event in neonates. There was no statistical difference in the risk of GI events of fluconazole compared with placebo (RR 0.81, 95 %CI 0.12–5.60, P = 0.831). The risk of GI events increased, but not significantly, when fluconazole was compared with other comparator antifungal drugs (RR 1.23, 95 % CI 0.88–1.71, P = 0.235) and nystatin (RR 2.02, 95 % CI 0.66–6.23, P = 0.219). Poisson regression analysis showed that the incidence of GI AEs were lower in neonates than children (IRR 0.15, 95 % CI 0.03–0.66, p = 0.012), while dose (IRR 1.07, 95 % CI 0.85–1.39, P = 0.585) and duration of treatment (IRR 1.01, 95 % CI 0.99–1.03, P = 0.07) were unlikely to significantly affect the incidence of GI events. Although oral administration increased the incidence of GI AEs, this increase was not significant (IRR 3.22, 95 % CI 0.72–14.33, P = 0.125).

There was a decrease in mortality when fluconazole was compared with placebo, but this was not significant (RR 0.62, 95 % CI, 0.38–1.03, P = 0.067). The mortality rate between the fluconazole group and antifungal drugs was not different (RR 1.01, 95 % CI 0.72–1.41, P = 0.960) (Table 3). No cases of drug-related death were documented. There were ten reported cases of serious AEs, five of which were not treatment-related [30]. The other serious AEs were five drug interactions [70–74]. Two interactions in children were with all-trans retinoic acid (ALTRA) and resulted in acute renal failure and pseudotumour cerebri [70, 71]. Another case of acute renal failure in a 9-year-old child was recorded following interaction with tacrolimus [73]. A 12-year-old child had syncope following co-administration with amitriptyline [72]. Co-administration of fluconazole with vincristine also caused severe constipation [74].

Table 3.

Effect of fluconazole compared with placebo, nystatin and active comparator

| Relative risk | 95 % confidence interval | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo | |||

| Hepatotoxicity | 1.37 | 0.87–2.14 | 0.175 |

| GI events | 0.81 | 0.12–5.59 | 0.831 |

| Mortality | 0.62 | 0.37–1.03 | 0.067 |

| Withdrawal due to AE | 0.78 | 0.08–7.24 | 0.828 |

| Other antifungals | |||

| Hepatotoxicity | 1.43 | 0.67–3.03 | 0.352 |

| GI events | 1.23 | 0.88–1.71 | 0.235 |

| Mortality | 1.01 | 0.72–1.41 | 0.960 |

| Withdrawal due to AE | 1.25 | 0.62–2.53 | 0.534 |

| Nystatin | |||

| Hepatotoxicity | 1.92 | 1.13–3.26 | 0.016* |

| GI events | 2.02 | 0.66–6.23 | 0.219 |

| Mortality | 1.01 | 0.02–50.41 | 0.825 |

| Withdrawal due to AE | 1.01 | 1.11–9.59 | 0.992 |

* (<0.05) statistically significant

Discussion

Hepatotoxicity was the most frequent AE described in this systematic review of the safety of fluconazole. It usually manifested as conjugated hyperbilirubinaemia or deranged liver enzymes and was also the most frequent reason for withdrawal of fluconazole in both neonates and paediatric patients. Our review demonstrated that over 80 % of the cases with known outcomes had complete resolution during treatment or after completion of therapy. Hepatotoxicity risk was significantly greater in patients on fluconazole compared with nystatin (p = 0.016). The better safety of nystatin compared with fluconazole has also been described by previous authors [75]. There was an increased risk of hepatotoxicity with fluconazole than placebo, but this increase was not significant (p = 0.175). Prematurity, total parenteral nutrition, infection and congenital abnormalities are known risk factors for hepatotoxicity in neonates [76]. More neonates than children developed hepatotoxicity, even though this incidence was not significantly different. Although animal studies have demonstrated a dose-dependent histological evidence of hepatotoxicity [77], this review did not show any significant effect of increasing dose on liver toxicity, probably because most of the reviewed articles administered fluconazole within the therapeutic dose limit of ≤12 mg/kg.

Our review also showed that GI events were the second most common AE after hepatotoxicity; however, the relative risk of this event is not statistically different between patients on fluconazole and placebo or other antifungals. There was just one recorded case of a GI AE in neonates. This may be related to the fact that neonates are unable to self- report these events, and GI events are less likely to be identified by clinicians and parents. Nausea and abdominal pain, for example, are extremely difficult, if not impossible to detect in this age group.

Drug interactions with fluconazole have been documented. Fluconazole is a potent inhibitor of CYP enzymes and is known to inhibit both CYP3A and CYP1A2 enzymes [78]. Therefore, drug interactions with medicines such as tacrolimus, vincristine, ALTRA, midazolam, caffeine and amitriptyline are likely. Clinicians need to be aware of these interactions and monitor for AEs.

The relatively small number of patients in several of the groups for meta-analysis requires that these results be interpreted with caution. There were very few placebo controlled RCTs—a pool of which involved fewer than 500 patients. Such a small number may be insufficient to detect rare events. Additionally, the majority of the RCTs are primarily efficacy studies with poor and inconsistent reporting of safety outcomes. We excluded about 25 % of the identified RCTs because of their poor quality of safety reporting. Some of these limitations were also identified in several studies evaluating the quality of safety reporting in RCTs [79, 80]. Authors often fail to indicate the severity of the AEs and, in several cases, the relationship with medication was not determined. In addition, the duration of observation and outcome of AEs were often not established, with about 30 % of cases of hepatotoxicity not followed up to identify whether resolution had occurred. Comparison of fluconazole with other antifungal agents, except nystatin, was also impossible because of the paucity of good quality studies. Further research should include studies with extended follow-up to capture data regarding the resolution of hepatotoxicity, especially in the neonatal population.

In conclusion, fluconazole is relatively safe for paediatric patients. Hepatotoxicity and GI events are the most common AEs. It is important to be aware that drug interactions with fluconazole can result in significant toxicity [81–111].

Acknowledgements

This work is part of the TINN network (Collaborative Project) supported by the European Commission under the Health Cooperation Work Programme of the 7th Framework Programme (grant agreement no. 223614).

Funding

This research was conducted within the framework of a TINN project, a FP7 project sponsored by the European Commission.

References

- 1.Benjamin DK, Jr, Stoll BJ, Gantz MG, Walsh MC, Sanchez PJ, Das A, et al. Neonatal candidiasis: epidemiology, risk factors, and clinical judgment. Pediatrics. 2010;126:e865–e873. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes D, Benjamin DK, Calandra TF, Edwards JE, Jr, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of candidiasis: update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:503–535. doi: 10.1086/596757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roilides E. Invasive candidiasis in neonates and children. Early Hum Dev. 2011;87(Suppl 1):S75–S76. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2011.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Festekjian A, Neely M. Incidence and predictors of invasive candidiasis associated with candidaemia in children. Mycoses. 2011;54:146–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2009.01785.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Richardson K, Cooper K, Marriot MS, Tarbit MH, Troke PF, Whittle PJ. Discovery of fluconazole:a novel antifungal agent. Rev Infect Dis. 1990;12:S267–S271. doi: 10.1093/clinids/12.Supplement_3.S267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grant SM, Clissold SP. Fluconazole: a review of its pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic potential in superficial and systemic mycoses. Drugs. 1990;39:877–916. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199039060-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kelly SL, Lamb DC, Kelle DE. Y132H substitution in Candida albicans sterol 14α-demethylase confers fluconazole resistance by preventing binding to haem. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;180:171–175. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb08792.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pfizer Inc (2011) DIFLUCAN®. Available from http://labeling.pfizer.com. Accessed: 7 April 2012

- 9.Brammer KW, Coates PE. Pharmacokinetics of fluconazole in paediatric patients. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1994;13:325–329. doi: 10.1007/BF01974613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saxen H, Hoppu K, Pohjavuori M. Pharmacokinetics of fluconazole in very low birth weight infants during the first two weeks of life. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1993;54:269–277. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1993.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) 2005. Fluconazole 2 mg/ml solution for infusion. Available at: http://www.mhra.gov.uk/home/groups/par/documents/websiteresources/con079044.pdf. Accessed: 7 Dec 2011

- 12.de Vries TW, van Roon EN. Low quality of reporting adverse drug reactions in paediatric randomised controlled trials. Arch Dis Child. 2010;95:1023–1026. doi: 10.1136/adc.2009.175562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Potts JA, Rothman AL. Clinical and laboratory features that distinguish dengue from other febrile illnesses in endemic populations. Trop Med Int Health. 2008;13(11):328–1340. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02151.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maund E, Craig D, Suekarran S, Neilson AR, Wright K, Brealey S, Dennis L, Goodchild L, Hanchard N, Rangan A, Richardson G, Robertson J, McDaid C. Management of frozen shoulder: a systematic review and cost-effectiveness analysis. Health Technol Assess. 2012;16(11):419. doi: 10.3310/hta16110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. Br Med J. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kicklighter SD, Springer SC, Cox T, Hulsey TC, Turner RB. Fluconazole for prophylaxis against candidal rectal colonization in the very low birth weight infant. Pediatrics. 2001;107:293–298. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.2.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Violaris K, Carbone T, Bateman D, Olawepo O, Doraiswamy B, Lacorte M. Comparison of fluconazole and nystatin oral suspensions for prophylaxis of systemic fungal infection in very low birthweight infants. Am J Perinatol. 2010;27:73–78. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1224871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Driessen M, Ellis JB, Cooper PA, Wainer S, Muwazi F, Hahn D, et al. Fluconazole vs. amphotericin B for the treatment of neonatal fungal septicemia: A prospective randomized trial. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1996;15:1107–1112. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199612000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaufman D, Boyle R, Hazen KC, Patrie JT, Robinson M, Donowitz LG. Fluconazole prophylaxis against fungal colonization and infection in preterm infants. N Engl J Med. 2001;2345:1660–1666. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manzoni P, Stolfi I, Pugni L, Decembrino L, Magnani C, Vetrano G, et al. A multicenter, randomized trial of prophylactic fluconazole in preterm neonates. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2483–2495. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aydemir C, Oguz SS, Dizdar EA, Akar M, Sarikabadayi YU, Sibel S, et al. Randomised controlled trial of prophylactic fluconazole versus nystatin for the prevention of fungal colonisation and invasive fungal infection in very low birth weight infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2011;96:F164–F168. doi: 10.1136/adc.2009.178996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaufman DA, Cuff AL, Wamstad JB, Boyle R, Gurka MJ, Grossman LB, et al. Fluconazole prophylaxis in extremely low birth weight infants and neurodevelopmental outcomes and quality of life at 8 to 10 years of age. J Pediatr. 2011;158:759–65.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Groll AH, Just-Nuebling G, Kurz M, Mueller C, Nowak-Goettl U, Schwabe D, et al. Fluconazole versus nystatin in the prevention of Candida infections in children and adolescents undergoing remission induction or consolidation chemotherapy for cancer. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;40:855–862. doi: 10.1093/jac/40.6.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gupta AK, Adam P, Dlova N, Lynde CW, Hofstader S, Morar N, et al. Therapeutic options for the treatment of tinea capitis caused by Trichophyton species: griseofulvin versus the new oral antifungal agents, terbinafine, itraconazole, and fluconazole. Pediatr Dermatol. 2001;18:433–438. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1470.2001.01978.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Flynn PM, Cunningham CK, Kerkering T, San Jorge AR, Peters VB, Pitel PA, et al. Oropharyngeal candidiasis in immunocompromised children: a randomized, multicenter study of orally administered fluconazole suspension versus nystatin. J Pediatr. 1995;127:322–328. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(95)70321-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ninane J, Gluckman E, Gibson BS, Stevens RF, Darbyshire PJ, Ball LM, et al. A multicentre study of fluconazole versus oral polyenes in the prevention of fungal infection in children with hematological or oncological malignancies. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1994;13:330–337. doi: 10.1007/BF01974614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schaison GS, Decroly FC. Propylaxis, cost and effectiveness of therapy of infections caused by Gram-positive organisms in neutropenic children. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1991;27(Suppl B):61–67. doi: 10.1093/jac/27.suppl_B.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hernandez-Sampelayo T, Roberts A, Tricoire J, Gibb DM, Holzel H, Novelli VM, et al. Fluconazole versus ketoconazole in the treatment of oropharyngeal candidiasis in HIV-infected children. EJCMID. 1994;13:340–344. doi: 10.1007/BF01974616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Foster KW, Friedlander SF, Panzer H, Ghannoum MA, Elewski BE. A randomized controlled trial assessing the efficacy of fluconazole in the treatment of pediatric tinea capitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:798–809. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mondal RK, Singhi SC, Chakrabarti A, Jayashree M. Randomized comparison between fluconazole and itraconazole for the treatment of candidemia in a pediatric intensive care unit: a preliminary study. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2004;5:561–565. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000144712.29127.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bertini G, Perugi S, Dani C, Filippi L, Pratesi S, Rubaltelli FF. Fluconazole prophylaxis prevents invasive fungal infection in high-risk, very low birth weight infants. J Pediatr. 2005;147:162–165. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Manzoni P, Arisio R, Mostert M, Leonessa M, Farina D, Latino MA, et al. Prophylactic fluconazole is effective in preventing fungal colonization and fungal systemic infections in preterm neonates: a single-center, 6-year, retrospective cohort study. Pediatrics. 2006;117(1):e22–e32. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aghai ZH, Mudduluru M, Nakhla TA, Amendolia B, Longo D, Kemble N, et al. Fluconazole prophylaxis in extremely low birth weight infants: association with cholestasis. J Perinatol. 2006;26:550–555. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weitkamp JH, Ozdas A, LaFleur B, Potts AL. Fluconazole prophylaxis for prevention of invasive fungal infections in targeted highest risk preterm infants limits drug exposure. J Perinatol. 2008;28:405–411. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Healy CM, Campbell JR, Zaccaria E, Baker CJ. Fluconazole prophylaxis in extremely low birth weight neonates reduces invasive candidiasis mortality rates without emergence of fluconazole-resistant Candida species. Pediatrics. 2008;121:703–710. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Uko S, Soghier LM, Vega M, Marsh J, Reinersman GT, Herring L, et al. Targeted short-term fluconazole prophylaxis among very low birth weight and extremely low birth weight infants. Pediatrics. 2006;117:1243–1252. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Manzoni P, Leonessa M, Galletto P, Latino MA, Arisio R, Maule M, et al. Routine use of fluconazole prophylaxis in a neonatal intensive care unit does not select natively fluconazole-resistant Candida subspecies. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27:731–737. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318170bb0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gupta AK, Dlova N, Taborda P, Morar N, Taborda V, Lynde CW, et al. Once weekly fluconazole is effective in children in the treatment of tinea capitis: a prospective, multicentre study. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:965–968. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huttova M, Hartmanova I, Kralinsky K, Filka J, Uher J, Kurak J, et al. Candida fungemia in neonates treated with fluconazole: report of forty cases, including eight with meningitis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1998;17:1012–1015. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199811000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sesmero JMM, Sedano FJF, García TM, Brussi MM, Ferrández JSR, Fernández RD, et al. Fungal chemoprophylaxis with fluconazole in preterm infants. Pharm World Sci. 2005;27:475–477. doi: 10.1007/s11096-005-7909-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fasano C, O’Keeffe J, Gibbs D. Fluconazole treatment of children with severe fungal. Eur J Clin Infect Dis. 1994;13:344–347. doi: 10.1007/BF01974617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wainer S, Cooper PA, Gouws H, Akierman A. Prospective study of fluconazole therapy in systemic neonatal fungal infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1997;16:763–767. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199708000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Viscoli C, Castagnola E, Fioredda F, Ciravegna B, Barigione G, Terragna A. Fluconazole in the treatment of candidiasis in immunocompromised children. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:365–367. doi: 10.1128/AAC.35.2.365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cap J, Mojzesova A, Kayserova E, Bubanska E, Hatiar K, Trupl J, et al. Fluconazole in children: first experience with prophylaxis in chemotherapy-induced neutropenia in pediatric patients with cancer. Chemotherapy. 1993;39:438–442. doi: 10.1159/000238990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ehninger G, Schuler HK, Sarnow E. Fluconazole in the prophylaxis of fungal infection after bone marrow transplantation. Mycoses. 1996;39(7–8):259–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.1996.tb00135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ahmed I, Wahid Z, Nasreen S, Ansarif M. Fluconazole pulse therapy: effect on inflammatory tinea capitis (kerion and agminate folliculitis) J Pak Assoc Dermatol. 2004;14:70–74. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gürpinar AN, Balkan E, Kiliç N, Kiriştioǧlu I, Avşar I, Doǧruyol H. Fluconazole treatment of neonates and infants with severe fungal infections. J Int Med Res. 1997;25:214–218. doi: 10.1177/030006059702500408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Marchiso P, Principi N. Treatment of oropharyngeal candidiasis in HIV-infected children with oral fluconazole. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1994;13:694. doi: 10.1007/BF01974007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Presterl E, Graninger W, Brammer KW, Dopfer R, Schmitt HJ, Gadner H, et al. Efficacy and safety of fluconazole in the treatment of systemic fungal infections in pediatric patients. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1994;13:347–351. doi: 10.1007/BF01974618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fasano C, O’Keeffe J, Gibbs D. Fluconazole treatment of neonates and infants with severe fungal infections not treatable with conventional agents. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1994;13:351–354. doi: 10.1007/BF01974619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Driessen M, Ellis JB, Muwazi F, De Villiers FPR. The treatment of systemic candidiasis in neonates with oral fluconazole. Ann Trop Paediatr. 1997;17:263–271. doi: 10.1080/02724936.1997.11747897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bilgen H, Ozek E, Korten V, Ener B, Molbay D. Treatment of systemic neonatal candidiasis with fluconazole [1] Infection. 1995;23:394. doi: 10.1007/BF01713579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kamiya H, Ihara T, Yasuda N, Sakurai M, Ito M, Azuma E, et al. Experience of fluconazole granules and injection in pediatric patients. Jpn J Antibiot. 1994;47:280–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sugita K, Miyake M, Takitani K, Murata T, Nishimura T, Aoki S. Pharmacokinetic and clinical evaluations of fluconazole in pediatric patients. Jpn J Antibiot. 1994;47:296–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Groll A, Nowak-Gottl U, Wildfeuer A, Weise M, Schwabe D, Gerein V, et al. Fluconazole treatment of oropharyngeal candidosis in spediatric cancer patients with severe mucositis following antineoplastic chemotherapy. Mycoses. 1992;35(Suppl):35–40. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Godula-Stuglik U. Endotracheal colonisation with Candida albicans in prolonged ventilated neonates—clinical manifestations and treatment with oral fluconazole. Pediatr Relat Top. 1997;35:459–465. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Caballero S, Jaraba Caballero MP, Fernández Gutiérrez F, Muriel Zafra I, Huertas Muñoz MD, Alvarez Marcos R et al (1998) Prospective study of Candidal sepsis in the neonate. Estudio prospectivo de sepsis por Candida en el recien nacido 48:639–643 [PubMed]

- 59.Saporito N, Tina LG, Betta P, Sciacca A. Fluconazole in the treatment of Candida albicans infection in premature infants. Clin Pediatr Chir. 1994;16:263–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Byers M, Chapman S, Feldman S, Parent A. Fluconazole pharmacokinetics in the cerebrospinal fluid of a child with Candida tropicalis meningitis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1992;111:895–896. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Krzeska L, Yeates RA, Pfaff G. Single dose intravenous pharmacokinetics of fluconazole infants. Drugs Exp Clin Res. 1993;19:267–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lee JW, Seibel NL, Amantea M, Whitcomb P, Pizzo PA, Walsh TJ. Safety and pharmacokinetics of fluconazole in children with neoplastic diseases. J Pediatr. 1992;120:987–993. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(05)81975-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Piper L, Smith PB, et al. Fluconazole loading dose pharmacokinetics and safety in infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30:375–378. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318202cbb3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Reuman PD, Kondor PRRND. Intraperitoneal and intravenous fluconazole pharmacokinetics in a pediatric patient with end stage renal disease. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1992;11:132–133. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199202000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Saxen H, Virtanen M, Carlson P, Hoppu K, Pohjavuori M, Vaara M, et al. Neonatal Candida parapsilosis outbreak with a high case fatality rate. Pediatr Infect Dis. 1995;14:776–781. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199509000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wenzl TG, Schefels J, Hornchen H, Skopnik H. Pharmacokinetics of oral fluconazole in premature infants. Eur J Pediatr. 1998;157:661–662. doi: 10.1007/s004310050906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Seay RE, Larson TA, Toscano JP, Bostrom BC, O’Leary MC, Uden DL. Pharmacokinetics of fluconazole in immune-compromised children with leukemia or other hematologic disease. Pharmacotherapy. 1995;15:52–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Saitoh A, Homans J, Kovacs A. Fluconazole treatment of coccidioidal meningitis in children: two case reports and a review of the literature. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2000;19:1204–1208. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200012000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schwarze R, Penk A, Pittrow L. Treatment of candidal infections with fluconazole in neonates and infants. Eur J Med Res. 2000;5(5):203–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yarali N, Tavil B, Kara A, Özkasap S, Tunç B. Acute renal failure during ALTRA treatment. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2008;25:115–118. doi: 10.1080/08880010801888287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vanier KL, Mattiussi AJ, Johnston DL. Interaction of all-trans-retinoic acid with fluconazole in acute promyelocytic leukemia. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2003;25:403–404. doi: 10.1097/00043426-200305000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Robinson RF, Nahata MC, Olshefski RS. Syncope associated with concurrent amitriptyline and fluconazole therapy. Ann Pharmacother. 2000;34:1406–1409. doi: 10.1345/aph.19401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dhawan A, Tredger JM, North-Lewis PJ, Gonde CE, Mowat AP, Heaton NJ. Tacrolimus (FK506) malabsorption: management with fluconazole coadministration. Transpl Int. 1997;10:331–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.1997.tb00713.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.van Schie RM, Bruggemann RJM, Hoogerbrugge PM, te Loo DMWM. Effect of azole antifungal therapy on vincristine toxicity in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66(8):1853–1856. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dhondt F, Ninane J, De Beule K, Dhondt A, Cauwenbergh G. Oral candidosis: treatment with absorbable and non-absorbable antifungal agents in children. Mycoses. 1992;35(1–2):1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.1992.tb00812.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Klein CJ, Revenis M, Kusenda C, Scavo L. Parenteral nutrition-associated conjugated hyperbilirubinemia in hospitalized infants. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110:1684–1695. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2010.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Somchit N, Norshahida AR, Hasiah AH, Zuraini A, Sulaiman MR, Noordin MM. Hepatotoxicity induced by antifungal drugs itraconazole and fluconazole in rats: a comparative in vivo study. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2004;23:519–525. doi: 10.1191/0960327104ht479oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yamazaki H, Nakamoto M, Shimizu M, Murayama N, Niwa T. Potential impact of cytochrome P450 3A5 in human liver on drug interactions with triazoles. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;69:593–597. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2010.03656.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Anderson M, Choonara I. A systematic review of safety monitoring and drug toxicity in published randomized controlled trials of antiepileptic drugs in children over a 10-year period. Arch Dis Child. 2011;95:731–738. doi: 10.1136/adc.2009.165902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.de Vries TW, van Roon EN. Low quality of reporting adverse drug reactions in paediatric randomised controlled trials. Arch Dis Child. 2010;95(12):1023–1026. doi: 10.1136/adc.2009.175562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Supplementary references

- 81.Aihara Y, Mori M, Yokota S. Successful treatment of onychomycosis with fluconazole in two patients with hyperimmunoglobulin E syndrome. Pediatr Dermatol. 1996;13:493–495. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.1996.tb00732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Assaf RR, Elewski BE. Intermittent fluconazole dosing in patients with onychomycosis: results of a pilot study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35(2 Part I):216–219. doi: 10.1016/S0190-9622(96)90327-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bode S, Pedersen-Bjergaard L, Hjelt K. Candida albicans septicemia in a premature infant successfully treated with oral fluconazole. Scand J Infect Dis. 1992;24:673–675. doi: 10.3109/00365549209054656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bergman KA, Meis JF, Horrevorts AM, Monnens L. Acute renal failure in a neonate due to pelviureteric candidal bezoars successfully treated with long-term systemic fluconazole. Acta Paediatr Int J Paediatr. 1992;81(9):709–711. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1992.tb12342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bunin N. Oral fluconazole for treatment of disseminated fungal infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1989;8(1):62. doi: 10.1097/00006454-198901000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bonnet E, Massip P, Bauriad LA, Auvergant J. Fluconazole monotherapy for Candida meningitis in premature infant. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;23:645–646. doi: 10.1093/clinids/23.3.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cap J, Sejnova V, Soltes L, Krcmery V., Jr Fluconazole in the treatment of mycotic infection in children. Int J Exp Clin Chemother. 1991;4(4):219–223. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Cruciani M, Di Perri G, Molesini M, Vento S, Concia E, Bassetti D. Use of fluconazole in the treatment of Candida albicans hydrocephalus shunt infection. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1992;11(10):957. doi: 10.1007/BF01962387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Guillén Fiel G, Gonzalez-Granado LI, Mosqueda R, Negreira S, Giangaspro E. Arthritis caused by Candida in an immunocompetent infant with a history of systemic candidiasis in the neonatal period. Ann Pediatr (Barc) 2009;70(4):383–385. doi: 10.1016/j.anpedi.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Filipowicz J, Kozłowski M, Irga N, Szalewska M, Zurowska A, Slusarczyk M. Acute renal insufficiency during Candida albicans candidiasis in a 2-month old infant (in Polish) Przegl Lek. 1997;54(1):73–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hsieh WB, Leung C. Candidal arthritis after complete treatment of systemic candidiasis. J Chin Med Assoc. 2005;68:191–194. doi: 10.1016/S1726-4901(09)70248-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kamitsuka MD, Nugent NA, Conrad PD, Swanson TN. Candida albicans brain abscesses in a premature infant treated with amphotericin B, flucytosine and fluconazole. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1995;14(4):329–331. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199504000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kawamori J, Tsuruta S, Yoshida T. Effect of fluconazole on Aspergillus infection associated with chronic granulomatous disease (in Japanese) Kansenshogaku zasshi (J Jpn Assoc Infect Dis) 1991;65(9):1200–1204. doi: 10.11150/kansenshogakuzasshi1970.65.1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Maruta A, Matsuzaki M, Fukawa H, Kodama F. Clinical evaluation of fluconazole in the case of deep mycosis associated with leukemia. Jpn J Antibiot. 1989;42(1):117–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zia-ul-Miraj M, Mirza I. Fluconazole for treatment of fungal infections of the urinary tract in children. Pediatr Surg Int. 1997;12(5–6):414–416. doi: 10.1007/BF01076953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Mercurio MG, Silverman RA, Elewski BE. Tinea capitis: fluconazole in Trichophyton tonsurans infection. Pediatr Dermatol. 1998;15(3):229–232. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1470.1998.1998015229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Morris SA, Bailey CJ, Cartledge JM. Neonatal renal candidiasis. J Paediatr Child Health. 1994;30(2):186–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.1994.tb00608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Oka S, Tokitsu M, Mori H, Nakata H, Goto M, Shimida K. Clinical evaluation of fluconazole. Jpn J Antibiot. 1989;42(1):31–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Oleinik EM, Della-Latta P, Rinaldi MG, Saiman L. Candida lusitaniae osteomyelitis in a premature infant. Am J Perinatol. 1993;10(4):313–315. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-994749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Neal DE, Jr, Rodriguez G, Hanson JA, Harmon E. Fluconazole treatment of fungal UTIs in pediatric patients. Infect Med. 1996;13(3):169–70+77. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Aguilera Olmos R, Mezquita Edo C, Escorihuela Centelles A, Moreno Palanques MA, Rosales Marza A, Alos Alminana M, et al (1995) Systemic neonatal candidiasis. Treatment with fluconazole (in Spanish). Rev Esp Pediatr 51(306):572–574

- 102.Pernica JM, Dayneka N, Hui CPS. Rectal fluconazole for tinea capitis. Paediatr Child Health. 2009;14:573–574. doi: 10.1093/pch/14.9.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ratajczak B, Wierzba J, Irga N, Czarniak P, Kosiak W, Samet A, et al (1996) The clinical course of fungal urinary tract infection in neonates (in Polish). Ped Pol 71:331–337 [PubMed]

- 104.Ramdas K, Minamoto GY. Candidal sepsis and meningitis in a very-low-birth weight infant successfully treated with fluconazole and flucytosine. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;19:795–796. doi: 10.1093/clinids/19.4.793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Stocker M, Caduff JH, Spalinger J, Berger TM. Successful treatment of bilateral renal fungal balls with liposomal amphotericin B and fluconazole in an extremely low birth weight infant. Eur J Pediatr. 2000;159(9):676–678. doi: 10.1007/PL00008405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Tucker RM, Galgiani JN, Denning DW, Hanson LH, Graybill JR, Sharkey K, et al. Treatment of coccidioidal meningitis with fluconazole. Rev Infect Dis. 1990;12(Suppl 3):S380–S389. doi: 10.1093/clinids/12.Supplement_3.S380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Van’t Wout JW, De Graeff-Meeder ER, Paul LC, Kuis W, Van Furth R. Treatment of two cases of cryptococcal meningitis with fluconazole. Scand J Infect Dis. 1988;20(2):193–198. doi: 10.3109/00365548809032437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Viscoli C, Castagnola E, Corsini M, Gastaldi R, Soliani M, Terragna A. Fluconazole therapy in an underweight infant. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1989;8(10):925–926. doi: 10.1007/BF01963785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wakiguchi H, Hisakawa H, Sinohara M, Watanabe S, Okada T, Misaki Y, et al. Fluconazole therapy for pediatric patients with severe candidal infections. Jpn J Antibiot. 1994;47(3):304–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Weintrub PS, Chapman A, Piecuch R. Renal fungus ball in a premature infant successfully treated with fluconazole. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1994;13(12):1152–1154. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199412000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Yagi S, Watanabe M, Nakajima M, Tsukiyama K, Moriya O, Hino J, et al. A clinical evaluation of fluconazole in the treatment of deep mycosis. Jpn J Antibiot. 1989;42(1):144–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]