Abstract

4-oxalocrotonate tautomerase (4-OT), a member of tautomerase superfamily, is an essential enzyme in the degradative metabolism pathway occurring in the Krebs cycle. The proton transfer process catalyzed by 4-OT has been explored previously using both experimental and theoretical methods, however, the elaborate catalytic mechanism of 4-OT still remains unsettled. By combining classical molecular mechanics with quantum mechanics, our results demonstrate that the native hexametric 4-OT enzyme, including six protein monomers, must be employed to simulate the proton transfer process in 4-OT due to protein-protein steric and electrostatic interactions. As a consequence, only three out of the six active sites in the 4-OT hexamer are observed to be occupied by three 2-oxo-4-hexenedioates (2o4hex), i.e., half-of-the-sites occupation. This agrees with experimental observations on negative cooperative effect between two adjacent substrates. Two sequential proton transfers occur: one proton from the C3 position of 2o4hex is initially transferred to the nitrogen atom of the general base, Pro1. Subsequently, the same proton is shuttled back to the position C5 of 2o4hex to complete the proton transfer process in 4-OT. During the catalytic reaction, conformational changes (i.e., 1-carboxyl group rotation) of 2o4hex may occur in the 4-OT dimer model but cannot proceed in the hexametric structure. We further explained that the docking process of 2o4hex can influence the specific reactant conformations and an alternative substrate (2-hydroxymuconate) may serve as reactant under a different reaction mechanism than 2o4hex.

Keywords: QM/MM, QM/MM-MFEP, enzyme catalysis, half-of-the-sites, 4-oxalocrotonate tautomerase, 4-OT, proton transfer

Introduction

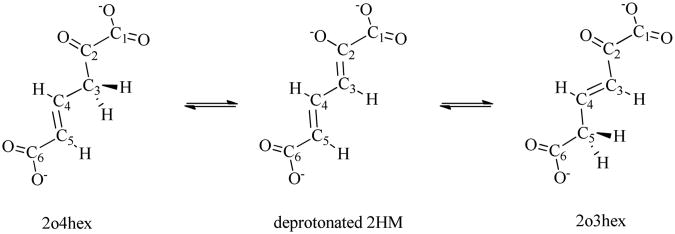

4-oxalocrotonate tautomerase (4-OT), with an amino-terminal proline and a beta-alpha-beta fold, is an important enzyme in tautomerase superfamily1. 4-OT catalyzes the ketonization process of 2-oxo-4-hexenedioate (2o4hex), to its conjugated isomer, 2-oxo-3-hexadienedioate (2o3hex), through the dienol intermediate 2-hydroxymuconate (2HM)2 as shown in Figure 1. This proton transfer process is an essential part of degradative metabolism pathway to convert various aromatic hydrocarbons into their corresponding intermediates in the Krebs cycle3. 4-OT is a unique enzyme in terms of its biological and chemical significances: i) it is one of the smallest subunit enzymes (each subunit has only 62 amino acids4) with the catalytical efficiency around seven orders (the ketonization process has the rate of 3×103 s-1 in 4OT, while its rate is about 1.7×10-4 s-1 in aqueous solution with the reaction barrier around 23 kcal/mol); ii) the proton transfer catalyzed by 4-OT does not involve any co-factors or transition metals; iii) the catalytic residue is an N-terminal proline.

Figure 1.

Three structure formula of the substrate in 4-OT during proton transfer process.

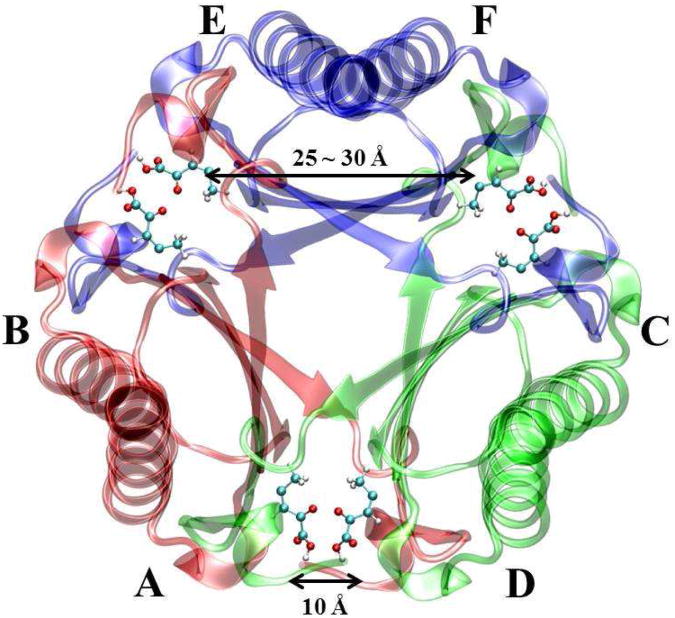

Experimental2,4-14 and theoretical15-21 studies on 4-OT have been carried out since 1990's. The crystal structure of apo-4-OT is composed of six identical subunits arranged into three dimers (i.e., a hexamer)12. The spatial positions of the six subunits labeled by A to F are shown in Figure 2 with six inhibitors (2-oxo-3-pentynoate). Each subunit contains one active site (i.e. the hydrophobic region surrounding the amino-terminal proline: Pro1). Mutation experiments and theoretical studies have clearly showed that no general acid is required during catalysis. Instead, the amino-terminal proline (Pro1) acts as a general base during proton transfer. Several residues in the active site, such as Arg11′, Arg39″, and Leu8′, play important roles to stabilize the reactant as well as promote the reaction via electrostatic interactions20,22. (Note that the residues with single prime reside in the neighboring subunit of the same dimer while the residues with double primes belong to the nearby subunit of the adjacent dimer.)

Figure 2.

Crystal structure of 4-OT (PDB ID: 1BJP) with six inhibitors (2-oxo-3-pentynoate). Six monomer, A, B, C, D, E, and F form three dimers, respectively. The A-B dimer is shown in red, C-D dimer is shown in green, and E-F dimer is shown in blue. Six inhibitors are the stick-ball model. Carbon: cyan, oxygen: red, and hydrogen: white.

Although previous studies6,12,14-16,18-22 of 4-OT have been helpful to understand the proton transfer process in the tautomerase superfamily, some key issues of this reaction are still obscure. First, are protein-protein interactions between monomers important to the reaction? As shown in Figure 2, six active sites (in A to F) of 4-OT are arranged in a symmetric way. Adjacent active sites within two dimers such as A and D are approximately 10 Å away. The distance between two non-adjacent active sites of the same dimer such as E and F, is between 25 ∼ 30 Å. Previous theoretical studies have applied both hexamer model (i.e., six protein monomers)16,21 and dimer model (i.e., two protein monomers)15 to study the reaction mechanism. However, 4-OT can only catalyze the reaction as a hexamer under physiological condition23. In addition, since each substrate has two negative charges on two carboxyl groups, the electrostatic interactions between two substrates (for instance, in A and D) are not negligible to the catalytic process of 4-OT. Although all six active sites could be occupied by the singly charged inhibitors12 as shown in Figure 2, equilibrium mixture titration and NMR experiments14 suggest a half-of-the-sites binding mechanism due to negative cooperative effect between two adjacent substrates (such as substrates in monomers A and D): Only three out of six active sites should be occupied to achieve the maximum reaction efficiency. Hence, different enzymatic structure models should be scrutinized to simulate the reaction.

Second, in the 4-OT catalytic process with Pro1 as a general base, two proton transfer pathways have been proposed previously: one proton at the C3 site of the substrate is abstracted by Pro1 and the same proton is shuttled back to the C5 site of 2o4hex (i.e., one-proton transfer mechanism) 16-21; or one proton at C3 is first abstracted by Pro1 but the other proton of Pro1-N is transferred back to the substrate (i.e., two-proton transfer mechanism)15. Unfortunately, these two distinct proton transfer mechanisms have not been emphasized by the previous theoretical works, which cannot be easily clarified by experiments.

Third, other issues related to the substrate conformation and even the proper reactant forms have been debated in previous experimental and theoretical studies. For instance, Ruiz-Pernia et. al15 recently proposed that significant conformational changes of 2o4hex are coupled with proton transfer based on their dimer structure model. However, some studies based on the hexamer structure model16 support that the substrate orientation does not influence the reaction process significantly although the 2o4hex substrate is very flexible in solvent. Whether the substrate undergoes conformational changes during proton transfer or not is still an open question. In addition, a recent experimental study19 suggests that 2HM in Figure S10 may be the appropriate reactant form instead of 2o4hex. Since 2HM is the dienol form of 2o4hex and it inter-converts fast with 2o4hex in aqueous solution, either 2HM or 2o4hex, or even both, can be the reactant forms in the catalytic process.

In this work, we built three 4-OT models: 3 dimers 3 substrates (3D3S), 3dimers 6 substrates (3D6S), and 1 dimer 1 substrate (1D1S) as listed in Table 1 to characterize the significances of protein-protein interactions on the reaction process. Our results show that the reaction process should be characterized by the hexamer model. The half-of-the-sites occupation mechanism is supported by comparing the reaction barrier differences between 3D3S and 3D6S. During the reaction, the same proton of C3 is transferred from C3 to C5 of 2o4hex via Pro1 as a general base. Large conformation changes on substrate (i.e., 1-carboxyl group rotations) do not occur based on the hexamer model. 2HM, which was used in previous experiments as an alternative reactant, may adopt another different reaction mechanism through water in the first proton transfer process comparing with the 2o4hex reactant.

Table I.

Three structural models of 4-OT.

| Model | Number of Dimers | Number of Substrates | Total Charge |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3D6S | 3 | 6 | -18 |

| 3D3S | 3 | 3 | -12 |

| 1D1S | 1 | 1 | -4 |

Computational Methods for QM/MM Simulations

The QM/MM minimum free-energy path method (QM/MM-MFEP)24,25 was applied to optimize the geometries of reactant and product. The reaction barriers were computed by combining QM/MM-MFEP with path optimization methods of Nudged Elastic Bond (NEB)26. The key feature of QM/MM-MFEP is that all of calculations are performed on a potential of mean force (PMF) surface of the fixed QM subsystem conformation, which is defined by

where E(rQM, rMM) is the total energy of the entire system expressed as a function of the Cartesian coordinates of the QM and MM subsystems. The QM/MM interaction energy in E(rQM, rMM) includes the electrostatic interactions from classical point charges and Van der Waals interactions between QM and MM subsystems. The QM point charges are fitted from the QM electrostatic potential with the QM geometry at each optimization cycle. The boundary atoms between QM and MM subsystems are simulated by the pseudobond approach27 with the recently refitted parameters28.

The QM/MM MFEP with sequential sampling is an efficient and accurate approach to perform reaction path optimization using the NEB or Quadratic String Method (QSM)29. The detailed procedure was discussed in Refs.24,25,30. This sequential sampling method has been successfully applied to study several enzymatic reaction mechanisms31-34 and solution reactions35. This approach was further extended to compute accurate redox free energies for different solutes in aqueous solution36.

Computational Details

Three Structural Models

The crystal structure of 4-OT with six inhibitors was taken from Ref. 21. Considering the proton transfer stereochemistry6 and the protonation states of histidine residues16, three enzyme models were built as listed in Table 1. In the 3D3S model, three substrates occupy three active sites since the negative cooperative effect was observed in experiments. As such, the shortest distance between two substrates in 3D3S is ∼25 Å compared to 10 Å in 3D6S when all six active sites are occupied. Since each monomer has one negative charge and each substrate has two negative charges, the total charges for 3D6S, 3D3S, and 1D1S systems are -18, -12, and -4, respectively. 3D6S and 3D3S are solvated in a rectangular water box of 90×90×90 Å3, which contains 5,869 protein atoms and 21,404 water molecules. 1D1S is solvated in a 64× 64× 92 Å3 water box with 1,971 protein atoms and 11,417 water molecules. Protein and water molecules are described by CHARMM22 force fields 37,38 and TIP3P model 39, respectively.

MD Simulations of Enzyme Complex

Using force field parameters on substrates from our previous study21, three model systems were warmed gradually from 10 K up to 300 K with a series of restrained 120 ps MD simulations. Harmonic restraints were applied on all heavy atoms with a force constant of 40 kcal/mol/Å2, then reduced to 20 kcal/mol/Å2. Finally, only Cα atoms were restrained with a force constant of 10 kcal/mol/Å2. During the warming procedure, all the substrate structures were fixed. 2 ns MD simulations for three models were performed without any restraints to reach the equilibrium states. Subsequently, three independent 2.4 ns MD simulations were carried out for three models to characterize the dynamic behaviors of three protein models. The leapfrog algorithm (a modified version of the Verlet algorithm40) was employed with different integration step sizes: 1 fs for short range force, 4 fs for medium range force, and 8 fs for long range electrostatic force. The PME method was applied to take long range electrostatic interactions41 into account with the uniform grids (i.e., one grid point per Å in this work). Bonds in water molecules were constrained by the SHAKE algorithm42. A 9-15 Å dual cut off method was employed to generate the nonbonded pair list, which was updated every 16 fs. The NVT ensemble was used in all molecular dynamic simulations with T=300K, which was maintained by the Berendsen thermostat 43 with 0.05 ps relaxation time.

QM/MM-MFEP Simulations of Proton Transfer Reaction

Since the reaction catalyzed by 4-OT is the proton transfer process with Pro1 as a general base, the active site described by QM contains the deprotonated 2o4hex, protonated Pro1, and the boundary atom Ile2 Cα between Pro1 and Ile2. Only one substrate is computed by QM during the QM/MM simulations while the other substrates are depicted by the fitted MM force fields21. Therefore, the total number of QM atoms is 33 including the boundary atom, which were calculated by B3LYP/6-31+G(d)44,45. All the geometries for reactants, intermediates, and product states were optimized by the QM/MM-MFEP approach. The bond length difference between Pro1-N-H and C3 of the substrate is used as the driving coordinate to generate the initial path from reactant to intermediate state while the bond length difference between Pro1-N-H and C5 of the substrate is chosen as another coordinate to obtain the initial path from intermediate to product states. The MM MD sampling time for single point geometry optimizations with the QM/MM-MFEP approach in the coordinate driving procedure is 40 ps. Based on the foregoing initial reaction paths, NEB was employed to optimize the reaction path in association with QM/MM-MFEP. During the NEB path optimizations, the MD sampling time was initially taken as 40 ps at each optimization cycle, and was increased to 80 ps later. The 160 ps MD sampling was also performed to verify the convergence of the path optimizations. The computational details for MM MD samplings in the QM/MM-MFEP calculations are same as the classical MD simulations discussed before.

Results and Discussion

Ketonization mechanism in 4-OT depends on enzymatic models

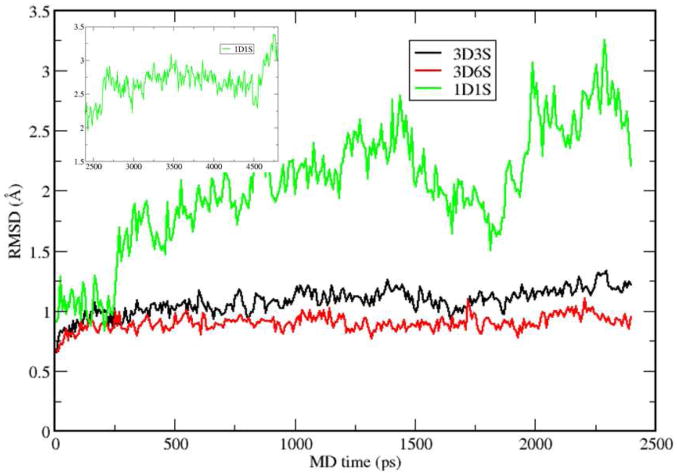

The root mean square deviations (RMSDs) of the alpha carbon atoms on the protein backbone computed from 4.8 and 2.4 ns MD simulations are shown in Figure 3 for 1D1S, 3D3S, and 3D6S using their initial structures as the references, respectively. The substrate form is chosen as the deprotonated 2HM, which is a stable intermediate state during proton transfer process. Pro1-N is protonated as well. The overall RMSD values for both 3D6S and 3D3S hexamer models are less than 1.5 Å, which suggests that the global structures of 3D6S and 3D3S are very stable. However, the 1D1S model exhibits large structural fluctuations, in which the RMSD value can be larger than 3 Å.

Figure 3.

RMSDs of 3D3S, 3D6S, and 1D1S from 2.4 ns MD simulations using the intermediate state of substrate.

The analysis of the MD trajectory in 1D1S (protein structure in shown in Figure S1) suggests that the substrate cannot bind tightly to the surrounding protein residues from one dimer of 4-OT. To further support this understanding, we monitored key substrate-protein hydrogen bond distances. Particularly, two hydrogen bond distances between Arg39 and the substrate and another two distances between Arg61′ and the substrate, as shown in Figures S2 and S3, fluctuate dramatically. The hydrogen bonds between Arg61′ and the deprotonated 2HM undergo large fluctuations and can be broken during the MD simulations while Arg39 rotate its side-chain to stabilize the substrate by breaking the initial hydrogen bonds (see Figure S2 for details) and plays a similar role as Arg39″ in other two hexamer models, the active site is highly exposed to the solvent and exhibits large fluctuations during the MD simulations. In contrast, the geometries of active sites in both 3D3S and 3D6S models are maintained as well as the entire protein structures. Based on the entire hexamer structure in Figure 2, the occupied active site in one dimer such as AB is encompassed with the beta sheet and alpha helix from subunits C and D. These protein-protein interactions between dimers can stabilize the beta-hairpin and beta-strand at the end of subunit A. As such, the hydrophobic environment surrounding the active site of subunit A is produced and is maintained during MD simulations. More importantly, the essential Arg39″ in the two hexamer models (note that the critical Arg39″ is completely missing in 1D1S) interacts with the 1-carboxyl group of the substrate through two hydrogen bonds, which can stabilize the substrate in 4-OT and promote the proton transfer reaction.

In the previous study by Ruiz-Pernia et al15 using the one dimer model with both active site occupied, they observed the proton transfer process is coupled with 1-carboxyl group rotation of the substrate. Since two active sites in one dimer are more than 20 Å away, our 1D1S model with one active site occupied is similar to Ruiz-Pernia's one dimer model. As such, we performed QM/MM MFEP reaction path optimization for the second proton transfer step with our 1D1S model (i.e., proton transfer from the protonated Pro1 to C5 of the deprotonated 2HM). The optimized reaction path for this second proton transfer step is shown in Figure S4 with the activation barrier around 7.0 kcal/mol, which agrees with the previous study in Ref. 15, which has the barrier around 5.0 kcal/mol. We found that after the second proton transfer is accomplished, the substrate undergoes the 1-carboxyl group rotations to further relax itself to a more stable conformation state with the barrier around 8.0 kcal/mol (see Figure S4). Although our calculations on the 1D1S model focus on the second proton transfer process, our results suggest that the proton transfer processes in 1D1S of 4-OT may involve the substrate conformation changes as shown in Ref. 15. Note that the dimer form of 4-OT can only exist when the pH value is less than 4.8 and the enzymatic activity is then completely lost23. Therefore, to reveal the subtle reaction mechanism of 4-OT in physiological conditions, we use the hexamer model (i.e., 3D3S and 3D6S) in the following sections.”

One-proton transfer mechanism is supported in 3D3S and 3D6S

The reaction process catalyzed by 4-OT includes two proton transfer steps through Pro1 as a general base and requires one definite intermediate (i.e., deprotonated 2HM) between the two steps (see Figure 1). Experiments alone cannot determine whether or not the same proton is involved for two sequential proton transfer steps. Herein, two mechanisms have been investigated in previous theoretical studies15,21: one-proton transfer mechanism, in which the same proton is transferred twice; and two-proton transfer mechanism, in which two different protons participate in two separate transfer steps.

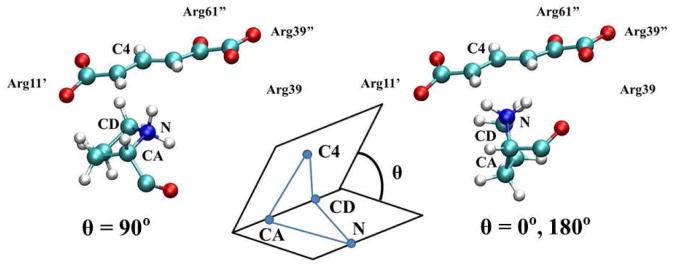

To determine the preference of either one- or two- proton transfer mechanism in 3D3S and 3D6S, we found that the Pro1 orientation with respect to the substrate conjugate plane is a structural metric. As shown in Figure 4, the relative positions between Pro1 and 2o4hex can be characterized by the dihedral angle formed by Pro1:N, Pro1:CA, Pro1:CD, and 2o4hex:C4 shown in the inset of Figure 4. When the five-ring plane of Pro1 is perpendicular to the conjugate plane of 2o4hex (i.e., θ=0° or 180°), the two-proton transfer mechanism is favorable: one proton is abstracted by Pro1 and the other one on Pro1-N is transferred to the substrate. When the dihedral angle between two planes is close to zero (i.e., θ=90°), the proton on Pro1 resides in the opposite side of the Pro1 plane that suggests one-proton transfer mechanism. Based on the 2.4 ns MD simulations with the deprotonated 2HM, the average dihedral angles were 62 and 60 degree in 3D3S and 3D6S, respectively (see Table S1). Therefore, the Pro1 plane is always parallel with respect to the substrate plane, which indicates that one-proton transfer mechanism is preferred in the hexamer models.

Figure 4.

The dihedral angle metric which distinguished two possible proton transfer pathways is defined by Pro1-N, Pro1-CA, Pro1-CD, and substrate-C4, i.e., N, CA, CD, and C4.

Since the substrates were described by the MM force fields in our MM MD simulations, we prepared one new system directly generated from the 4-OT crystal structure with the inhibitor (PDB ID: 1BJP)12. Note that the initial dihedral angle is close to 180°. Five independent direct QM/MM MD simulations (see details in SI-IV) with three 2o4hex substrates were performed up to 32 ps. (Note that only one substrate is characterized by QM and the other two are still computed by the MM force fields.) The average dihedral angles for five MD simulations were 92, 104, 98, 72, and 76 degree in Table S2. This result is consistent with the classical MM MD simulations. Overall, both MM and QM/MM simulations support that the Pro1 plane is parallel with respect to the substrate plane during the reaction. (Note that we have also carried out QM/MM-MFEP simulations to study the two-proton transfer mechanism in both 3D3S and 3D6S. We found that the active site is completely distorted due to the orientation of Pro1 plane and the reaction path cannot be obtained.) One-proton transfer mechanism is preferred because of this active site structural feature.

Half-of-the-sites occupation number is supported

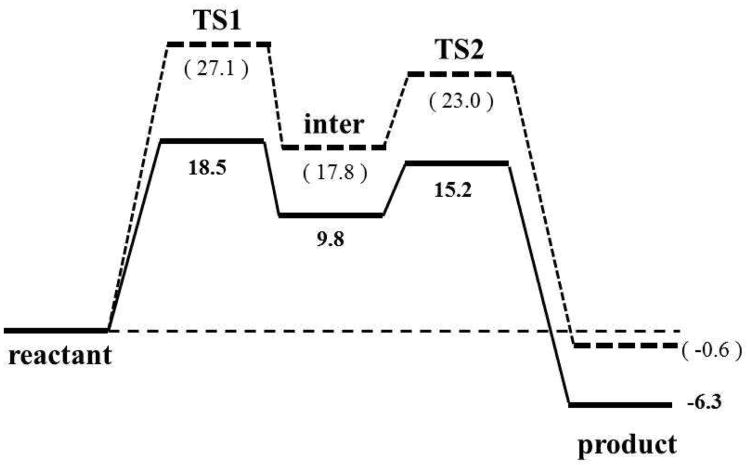

The free energy profiles of the optimized reaction paths for 3D3S and 3D6S using one-proton transfer mechanism is illustrated in Figure S5 and a simple free energy diagram about the reaction is shown in Figure 5. For both structural models, the reaction involves two sequential proton transfer steps as discussed in the next section. The rate-limiting step for the 3D3S and 3D6S models is the first proton transfer step with the reaction barriers of 18.5 and 27.1 kcal/mol, respectively. The barriers for the second proton transfer step are 15.2 and 23.0 kcal/mol, respectively in 3D3S and 3D6S. Since the only structural difference between 3D3S and 3D6S is the number of substrates in the 4-OT hexamer, the corresponding barrier difference indicates that the occupation of all active sites by six substrates in 3D6S impair the catalytic activity of 4-OT, which agrees with the experimental observations of negative cooperative effect14. Therefore, our theoretical calculations on 3D3S and 3D6S support the experimentally observed half-of-the-sites occupation mechanism in 4-OT.

Figure 5.

Reaction free energy diagrams of 3D3S (solid line) and 3D6S (dashed line). The reaction includes five states: reactant, the first transition state (TS1), the intermediate state (inter), the second transition state (TS2), and product. The bolded numbers are calculated from 3D3S model, and the unbolded numbers in parentheses are from 3D6S model.

In Figure 5, the free energy difference between intermediate and reactant states is only 9.8 kcal/mol in 3D3S compared to 17.8 kcal/mol in 3D6S. To explain why the deprotonated 2HM needs higher energy to reach in 3D6S than in 3D3S, the geometric differences between 3D3S and 3D6S around the active site were scrutinized using classical MD simulations with the intermediate state (i.e., deprotonated 2HM). We found that several distance patterns play important roles to stabilize the intermediate state, including key hydrogen bonds between the substrate (S) and nearby residues (i.e., Arg39″, Arg61′, Arg11′, and Leu8′) and one distance between Arg39 CZ atom and substrate C1 atom (Arg39-S). The measured average distances from MM MD simulations are listed in Table II. For 3D3S and 3D6S, Arg39″-S and Arg61′-S are nearly identical, which suggests that Arg61′ and Arg39″ bind tightly the head part (i.e., 1-carboxyl and 2-keto group) of the deprotonated 2HM through hydrogen bonds regardless of the occupation number in the six active sites. However, the bond distances of Arg11′-S, Leu8′-S, and Arg39-S in 3D3S are much shorter than in 3D6S. In fact, these shorter hydrogen bond distances between Leu8′/Arg11′ and the tail part of substrate in 3D3S help stabilize the intermediate state. In addition, Arg39-S in 3D6S becomes 1.4 Å longer than in 3D3S because Arg39 in 3D6S must bind another substrate in the adjacent active site. We further carried out Non-Covalent Interaction (NCI) analysis46,47 for a typical snapshot from 3D3S and 3D6S MD simulations to visualize and qualitatively compare non-covalent interactions strength48 between the substrate and the surrounding protein amino acids. As shown in Figure S6 (see details in SI-III), Arg39 forms a hydrogen bond to the deprotonated 2HM in 3D3S but not in 3D6S. In addition, the densities at the NCI critical point of interaction for the hydrogen bonds between Arg39″ and the deprotonated 2HM (list in Table II) are larger in 3D3S (0.052 and 0.057) than in 3D6S (0.031 and 0.045). This indicates that the hydrogen bond between Arg39″ and the deprotonated 2HM is stronger in 3D3S than in 3D6S. Overall, the NCI analysis qualitatively agrees with our previous structural analysis. As such, 3D3S can form more compact hydrophobic environments due to the half-of-the-sites occupation to stabilize the intermediate state and lower the activation barrier for the first proton transfer step.

Table II.

Average distances and NCI density between the substrate (“S”) and key residues from classical MM MD simulations using the intermediate state of substrate.

| Arg39″-S | Arg61′-S | Arg11′-S | Leu8′-S | Arg39-S | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3D3S | Distance(Å) | 1.78, 1.68 | 1.76, 1.72 | 1.73, 1.64 | 1.81 | 4.88 |

| Density | 0.052, 0.057 | 0.026, 0.034 | 0.064, 0.051 | 0.038 | 0.038 | |

|

| ||||||

| 3D6S | Distance(Å) | 1.76, 1.66 | 1.67, 1.76 | 2.18, 1.78 | 2.65 | 6.24 |

| Density | 0.031, 0.045 | 0.050, 0.045 | 0.022, 0.060 | 0.035 | ----- | |

Detailed reaction mechanism is revealed by the 3D3S model

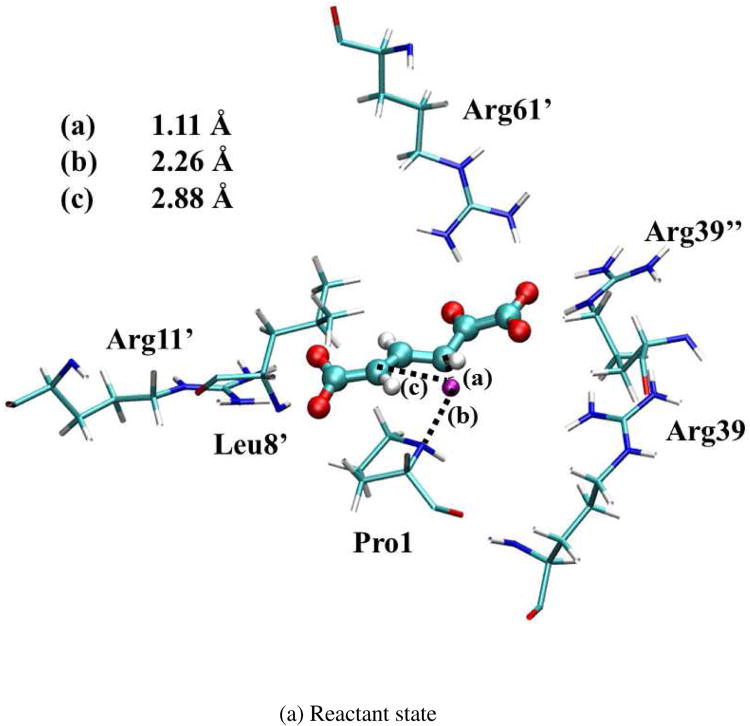

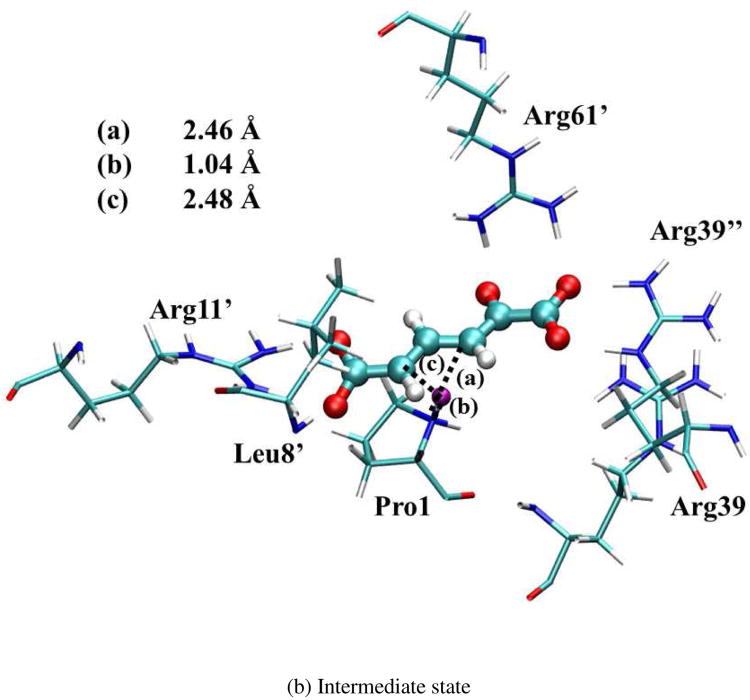

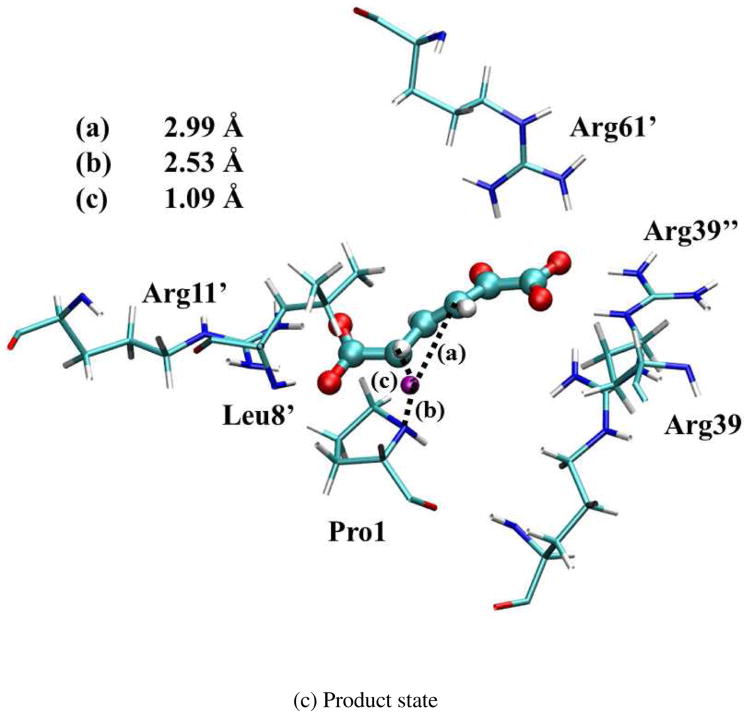

Based on the QM/MM-MFEP simulations of 3D3S, the proton transfer process catalyzed by 4OT includes two sequential proton transfer steps: the proton on the substrate C3 atom is abstracted by the nitrogen (Pro-N) atom on neutral Pro1 to reach the intermediate state; after the substrate slides slightly to pose the C5 atom of the substrate above Pro1-N, and then this proton is shuttled back to C5 on the Si face. The rate-limiting step is the first proton transfer step with the activation barrier 18.5 kcal/mol, which agrees with the previous theoretical studies15-17,21 and the estimated experimental value (13.8 kcal/mol)2.

The optimized geometries of the reactant (index 5 in Figure S5), intermediate (index 23), and product states (index 43) are shown in Figure 6. (Note that the intermediate state has some iso-energy conformations caused by the substrate sliding during the reaction. All these structures are chosen based on the lowest free energy points along the optimized reaction path.) Since the surrounding residues are crucial to stabilize these geometries, the ensemble averaged values of distances between the QM active site and surrounding residues in MM subsystems were calculated in QM/MM-MFEP simulations. All the key distances are listed in Table III for the reactant, first transition state (TS1), intermediate, second transition state (TS2), and product. The values of Arg39″-S, Arg11′-S, and Leu8′-S indicate that the Arg39″, Arg11′, and Leu8′ residues bind the substrate strongly in all five states during the reaction through the stable hydrogen bonds. The distance of Arg61′-S becomes shorter to stabilize TS1, intermediate, and TS2. Furthermore, the shorter distance of Arg39-S in the intermediate state suggests that Arg39 binds the intermediate state tightly to form a compact active site structure and stabilize the intermediate state. In contrast, Arg39 in 1D1S serves a similar role as Arg39″ in 3D3S, which stabilizes the 1-carobxyl group of 2o4hex and facilitates the proton transfer reaction. These structural observations are consistent with previous theoretical studies17,18,21. In contrast to the recent study15 based on one dimer model for 4-OT, no large conformation changes of the substrate occur during the reaction in 3D3S. Instead, the alternative reactant geometry of 2o4hex may exist during the reaction as discussed below.

Figure 6.

Optimized geometries for reactant, intermediate, and product states in 3D3S. The transferred proton is in purple. The key distances between the proton and C3/C5/Pro-N are shown in angstrom. (Structure coordinates are listed in Supporting Information)

Table III.

Average distances between the substrate (“S”) and key residues for five states of the reaction from QM/MM-MFEP simulations in the 3D3S model.

| Distance (Å) | Arg39″-S | Arg61′-S | Arg11′-S | Leu8′-S | Arg39-S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reactant | 1.73, 1.69 | 1.71, 1.91 | 1.64, 1.71 | 1.72 | 5.24 |

| TS1 | 1.69, 1.66 | 1.68, 1.78 | 1.66, 1.74 | 1.75 | 5.24 |

| Intermediate | 1.65, 1.67 | 1.67, 1.73 | 1.65, 1.72 | 1.72 | 4.37 |

| TS2 | 1.75, 1.60 | 1.63, 1.71 | 1.66, 1.76 | 1.74 | 5.18 |

| Product | 1.80, 1.58 | 1.75, 1.97 | 1.69, 1.79 | 1.76 | 4.98 |

2o4hex can have the alternative reactant geometry with different 1-carboxyl group orientation

As shown in Figure 6, the head 1-carboxyl group is stabilized by Arg61′, Arg39″, and Arg39 while the tail carboxyl group is anchored by hydrogen bonds with Arg11′ and Leu8′. However, 2o4hex itself is a flexible substrate in aqueous solution. In fact, we observed two possible reactant geometries with two different orientations of the 1-carboxyl group as shown in the insets of Figure S7 “straight” and “bent”. The free energy difference between the straight orientation and the bent one in 4-OT was computed by the QM/MM MFEP approach using the dihedral angle defined by atoms C1, C2, C3, and C4 of the substrate as the initial driving coordinate. Figure S7 indicates that the free energy difference between “straight” and “bent” conformations is less than 1 kcal/mol. (Note that the activation barrier between “straight” and “bent” conformations only demonstrates that such conformation changes are not possible after 2o4hex docks to the protein binding pocket.) Energetically, both “straight” and “bent” conformations are possible as the reactant. The specific reactant conformation in 4-OT depends on the docking process between the substrate and 4-OT. Furthermore, the first proton transfer step with the “bent” reactant in the 3D3S model was simulated by QM/MM-MFEP and the reaction profile was shown in Figure S8. The reaction barrier of the first proton transfer step is about 16.0 kcal/mol, which is comparable with the result from the “straight” reactant. This suggests that both “straight” and “bent” conformations of 2o4hex can be the reactant geometry.

The recent theoretical study by Ruiz-Pernia et al15 observed that the substrate conformation (i.e., the orientations of 1-carboxyl group) undergoes large changes during the reaction using their dimer model of 4-OT. In their works, the reactant 2o4hex with the “bent” conformation is first changed to the “straight” one in the intermediate state and the 1-carboxyl group rotates itself back to generate the “bent” product 2o3hex. In our 1D1S model, we also observe the substrate orientation change in the second proton transfer process, which supports that substrate conformational change might be necessary in a dimer model. However, in 3D3S and 3D6S models, we do not observe these large conformation changes. The substrate always remains either “straight” or “bent” during the reaction in the hexamer models.

Based on our simulation results of 1D1S, 3D3S, and 3D6S models, we found that the substrate conformation change depends on the enzymatic model used. In the dimer model (i.e., 1D1S and Ruiz-Pernia's models), Arg39 and Arg61′ cannot bind the substrate tightly. As such, the active site structure is flexible during the reaction. The rotation of the 1-carboxyl group of 2o4hex is required to promote the proton transfer process. In the hexamer model (i.e., 3D3S and 3D6S), the substrate is confined by surrounding amino acids including Arg39″, Arg61′ and Arg11′. The 1-carboxyl group of 2o4hex cannot be rotated easily and its rotation is not necessary to transfer the proton due to the docked structure (see Figure 6-(a)). In addition, the one-proton or two-proton transfer mechanism also depends on the enzymatic model. In the dimer model, since the active site is exposed to the solvent and endures large structural fluctuations, the Pro1 orientation might be perpendicular with respect to the substrate plane. Hence, the two-proton transfer mechanism is plausible in the dimer model, but not in the hexamer model.

The alternative reactant 2HM may adopt a water-mediated proton transfer mechanism

Based on the original experimental study2, 2o4hex has been used as the reactant form in most of theoretical studies. However, some recent experimental studies19,49 proposed that 2HM may serve as the reactant. (Note that more details about the reaction channels among 2o4hex, 2HM, and 2o3hex are discussed in SI-V.)

2HM has two different states: protonated or deprotonated. The deprotonated state in Figure 1 is the intermediate state of the 4-OT reaction. Since 2o4hex and protonated 2HM can interconvert quickly in aqueous solution, it is very challenging for experimental approaches to identify the correct reactant form. Herein, we performed 32 ps direct QM/MM MD simulations with 2o4hex and 2HM substrates using the “bent” conformation. The key reaction coordinates, i.e., the distance between Pro-R proton (stereo-chemically different from Pro-S proton) in 2o4hex (or 2-hydroxyl proton in 2HM) and Pro-N, were monitored during MD simulations. As listed in Tables S3 and S4, the average distances in 2o4hex are 3.40, 4.87, 3.74, 3.52, and 3.26 Å for five independent simulations. In contrast, the average distances in 2HM are 5.24, 5.28, 4.69, 5.07 and 4.74. The longer distance for the first step proton transfer in 2HM indicates that 2HM needs extra free energies to promote the first proton transfer. Further QM/MM-MFEP reaction path simulations on the first step, as shown in Figure S9, demonstrate that the reaction barrier for the first step using 2HM as reactant is increased 27.6 kcal/mol. Compared to the computed barrier 18.5 kcal/mol using 2o4hex in 3D3S, 2HM is not likely to be a suitable reactant when the direct proton transfer mechanism is applied for the first proton transfer process.

However, previous experiments19 demonstrated that 2HM (reaction barrier: 12.92 kcal/mol) can be catalyzed by 4-OT more efficiently than 2o4hex (reaction barrier: 13.77 kcal/mol). The discrepancy between our computed reaction profile and experiments indicates that 2HM may adopt a different reaction mechanism rather than direct proton transfer for the first step. We carried out three independent 640 ps classical MD simulations for 2HM, using both straight and bent conformations as the initial structures, respectively (substrate force field is generated using MATCH program50 and more simulation details are provided in SI-VI). The monitored distance between 2HM 2-hydroxyl proton and Pro-N is 4.17, 4.14 and 4.10 Å for three simulations with the bent conformation, and 5.60, 5.17 and 5.15 Å for three simulations with the straight conformation. The structural information suggests that the direct proton transfer from 2HM 2-hydroxyl proton to Pro-N is not favored. However, in all three simulations with the bent conformation, one water molecule forms a persistent hydrogen bond with the 2HM 2-hydroxyl proton. Hence, we proposed that the water molecule could participate in the first proton transfer process. The optimized reactant structure including this water molecule, surrounding with Arg 11′, Arg 61′, Arg39″ side chains, the bent 2HM, and Pro1 by our QM/MM-MFEP simulations is shown in Figure S11. Using this optimized structure, we conducted two-dimension potential energy surface (2D-PES) scan using two bond distances (r1, represents distance between 2-hydroxyl proton and water oxygen; r2 represents distance between water hydrogen and Pro nitrogen, see calculation details in section SI-VI) with Gaussian09 program51. The 2D-PES results in gas phase and implicit solvent model as shown in Figure S12 indicate that the water-mediated proton transfer process has a low activation barrier less than 10 kcal/mol. Therefore, 2HM may adopt a new reaction mechanism involving a water molecule to facilitate the first proton transfer. Further studies using QM/MM simulations on this new mechanism will be investigated.

Conclusions

Although the mechanism of proton transfer reaction catalyzed by 4-OT has been studied in the last ten years, several reaction details are not clear. In this work, we applied classical MD and ab initio QM/MM-MFEP simulations to explore the subtle reaction mechanism of the ketonization process. We found that 4-OT, as a hexamer, contains the strong protein-protein interactions needed to maintain the stable structures of six active sites. As a consequence, a real hexamer model is appropriate to study this enzyme. The proton transfer pathway only involves one single proton for the two sequential steps: the Pro-R proton on the substrate C3 atom is first abstracted by Pro-N to reach the intermediate state; and then this proton is shuttled back to C5 of the substrate on the Si surface to fulfill the ketonization process. By comparing the barrier difference between 3D3S and 3D6S, we demonstrate that this reaction achieves the optimal efficiency when three out of six active sites are occupied by three substrates. This is consistent with the negative cooperative effect observed in experiments. The substrate conformation changes of 2o4hex are not observed in our hexamer models. Two possible conformations of 2o4hex may exist as the reactant, which may be determined by the docking process between 2o4hex and 4-OT. We further showed that protonated 2HM may serve as reactant using a water-mediated reaction mechanism for the first proton transfer process. Overall, our work clarifies several important issues about the reaction mechanism of 4-OT and reveals the concrete proton transfer pathway in the ketonization process.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Support from the National Institute of Health (NIH R01-GM061870 to W.Y.) and Wayne State University (to G.A.C.) is greatly appreciated.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. Figures S1-S3 illustrates the structure of 1D1S model and monitored key hydrogen bonds between the substrate and 4-OT. Figure S4 shows the second proton transfer reaction profile in 1D1S. Non-covalent interaction visualization of 3D3S and 3D6S intermediate states is shown in Figure S6. Two 2o4hex conformations inter-conversion inside active site profile is shown in Figure S7. The optimized reaction path profiles of 3D3S, 3D6S, with 2o4hex substrate, and 3D3S with 2o4hex alternative conformation, 3D3S with 2HM substrate are given in Figures S5, S8 and S9. Three possible reaction channels for substrates are shown in Figure S10. The supporting tables S1-S4 list the average dihedral angles between Pro1 and substrate, and monitored first step proton transfer distance. The ab initio QM/MM MD simulation details, NCI analysis details are summarized in section III and IV, respectively. Further explanation of reactant form is discussed in section V. The simulation details with 2HM as reactant is summarized in SI-VI. All the Cartesian coordinates for Figure 6 are listed in section VII. Complete reference for Ref. 51 is also listed. This information is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org

Contributor Information

Xiangqian Hu, Email: xqhu@duke.edu.

Weitao Yang, Email: weitao.yang@duke.edu.

References

- 1.Whitman CP. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2002;402:1–13. doi: 10.1016/S0003-9861(02)00052-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whitman CP, Aird BA, Gillespie WR, Stolowich NJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:3154–3162. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harayama S, Rekik M, Ngai KL, Ornston LN. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:6251–6258. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.11.6251-6258.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen LH, Kenyon GL, Curtin F, Harayama S, Bembenek ME, Hajipour G, Whitman CP. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:17716–17721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whitman CP, Hajipour G, Watson RJ, Johnson WH, Bembenek ME, Stolowich NJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:10104–10110. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lian HL, Whitman CP. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:7978–7984. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson WH, Hajipour G, Whitman CP. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:8719–8726. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fitzgerald MC, Chernushevich I, Standing KG, Kent SBH, Whitman CP. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:11075–11080. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stivers JT, Abeygunawardana C, Mildvan AS, Hajipour G, Whitman CP, Chen LH. Biochemistry. 1996;35:803–813. doi: 10.1021/bi951077g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson WH, Czerwinski RM, Fitzgerald MC, Whitman CP. Biochemistry. 1997;36:15724–15732. doi: 10.1021/bi971608w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lian H, Czerwinski RM, Stanley TM, Johnson WH, Watson RJ, Whitman CP. Bioorganic Chem. 1998;26:141–156. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Czerwinski RM, Johnson WH, Whitman CP, Hackert ML. Biochemistry. 1998;37:14692–14700. doi: 10.1021/bi981607j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harris TK, Czerwinski RM, Johnson WH, Legler PM, Abeygunawardana C, Massiah MA, Stivers JT, Whitman CP, Mildvan AS. Biochemistry. 1999;38:12343–12357. doi: 10.1021/bi991116e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Azurmendi HF, Miller SG, Whitman CP, Mildvan AS. Biochemistry. 2005;44:7725–7737. doi: 10.1021/bi0502590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ruiz-Pernia JJ, Garcia-Viloca M, Bhattacharyya S, Gao JL, Truhlar DG, Tunon I. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:2687–2698. doi: 10.1021/ja8087423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tuttle T, Thiel W. J Phys Chem B. 2007;111:7665–7674. doi: 10.1021/jp0685986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sevastik R, Himo F. Bioorganic Chem. 2007;35:444–457. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tuttle T, Keinan E, Thiel W. J Phys Chem B. 2006;110:19685–19695. doi: 10.1021/jp0634858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cisneros GA, Wang M, Silinski P, Fitzgerald MC, Yang WT. J Phys Chem A. 2006;110:700–708. doi: 10.1021/jp0543328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cisneros GA, Wang M, Silinski P, Fitzgerald MC, Yang WT. Biochemistry. 2004;43:6885–6892. doi: 10.1021/bi049943p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cisneros GA, Liu HY, Zhang YK, Yang WT. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:10384–10393. doi: 10.1021/ja029672a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Metanis N, Brik A, Dawson PE, Keinan E. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:12726–12727. doi: 10.1021/ja0463841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Silinski P, Fitzgerald MC. Biochemistry. 2002;41:4480–4491. doi: 10.1021/bi011872w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hu H, Lu Z, Parks JM, Burger SK, Yang WT. J Chem Phys. 2008;128:034105–034123. doi: 10.1063/1.2816557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hu H, Lu Z, Yang WT. J Chem Theory Comput. 2007;3:390–406. doi: 10.1021/ct600240y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jonsson, H. M., G.; Jacobsen, K. W.; World Scientific: Singapore, 1998.

- 27.Zhang Y, Lee TS, Yang WT. J Chem Phys. 1999;110:46–54. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parks JM, Hu H, Cohen AJ, Yang WT. J Chem Phys. 2008;129:154106–154112. doi: 10.1063/1.2994288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burger SK, Yang WT. J Chem Phys. 2006;124:054109–054122. doi: 10.1063/1.2163875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hu H, Yang WT. Annu Rev Phys Chem. 2008;59:573–601. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physchem.59.032607.093618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parks JM, Hu H, Rudolph J, Yang WT. J Phys Chem B. 2009;113:5217–5224. doi: 10.1021/jp805137x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hu H, Boone A, Yang WT. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:14493–14503. doi: 10.1021/ja801202j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hu X, Hu H, Melvin JA, Clancy KW, McCafferty DG, Yang WT. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;113:478–485. doi: 10.1021/ja107513t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen Z, Concepcion JJ, Hu X, Yang WT, Hoertz PG, Meyer TJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2010;107:7225–7229. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001132107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hu H, Yang WT. J Phys Chem B. 2010;114:2755–2759. doi: 10.1021/jp905886q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zeng X, Hu H, Hu X, Yang WT. J Chem Phys. 2009;130:164111–164119. doi: 10.1063/1.3120605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mackerell AD, Feig M, Brooks CL. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:1400–1415. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bashford D, Bellott, Dunbrack RL, Evanseck JD, Field MJ, Fischer S, Gao J, Guo H, Ha S, Joseph-McCarthy D. J Phys Chem B. 1998;102:3586–3616. doi: 10.1021/jp973084f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jorgensen WL, Chandrasekhar J, Madura JD, Impey RW, Klein ML. J Chem Phys. 1983;79:926–935. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Verlet L. Phys Rev. 1967;159:98–103. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Darden T, York D, Pedersen L. J Chem Phys. 1993;98:10089–10092. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ryckaert JP, Ciccotti G, Berendsen HJC. J Comput Phys. 1977;23:327–341. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Berendsen HJC, Postma JPM, Gunsteren WFv, Dinola A, Haak JR. J Chem Phys. 1984;81:3684–3690. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee C, Yang WT, Parr RG. Phys Rev B. 1988;37:785–789. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.37.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Becke AD. Phys Rev A. 1988;38:3098–3100. doi: 10.1103/physreva.38.3098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Johnson ER, Keinan S, Mori-Sánchez P, Contreras-García J, Cohen AJ, Yang WT. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:6498–6506. doi: 10.1021/ja100936w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Contreras-García J, Johnson ER, Keinan S, Chaudret R, Piquemal JP, Beratan DN, Yang WT. J Chem Theory Comput. 2011;7:625–632. doi: 10.1021/ct100641a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Contreras-García J, Yang WT, Johnson ER. J Phys Chem A. 2011;115:12983–12990. doi: 10.1021/jp204278k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Johnson WH, Czerwinski RM, Stamps SL, Whitman CP. Biochemistry. 2007;46:11919–11929. doi: 10.1021/bi701231a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yesselman JD, Price DJ, Knight JL, Brooks CL. J Comput Chem. 2012;33:189–202. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Scalmani G, Barone V, Mennucci B, Petersson GA. Gaussian, Inc. (Revision A.1) 2009 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.