Abstract

Objectives

Focal treatment is a curative option for localized prostate cancer (PCA), but appropriate selection of patients hasn’t been established. We analyzed patients who had undergone radical prostatectomy (RP), with preoperative disease features considered favorable for focal treatment, to test the hypothesis that they would be accurately characterized with transrectal biopsy and prostate MRI.

Methods

202 patients with PCA who had preoperative MRI and low-risk biopsy criteria (no Gleason grade 4/5, one involved core, < 2 mm, PSA density ≤ 0.10, clinical stage ≤ T2a). Indolent RP pathology was defined as no Gleason 4/5, organ confined, tumor volume < 0.5cc, negative surgical margins. MRI ability to locate and determine the tumor extent was assessed.

Results

After RP, 101 men (50%) had non-indolent cancer. Multifocal and bilateral tumors were present in 81% and 68% of patients, respectively. MRI indicated extensive disease in 16 (8%). MRI sensitivity to locate PCA ranged from 2–20%, and specificity from 91–95%. On univariate analysis, MRI evidence of extracapsular extension (ECE) (P = 0.027) and extensive disease (P = 0.001) were associated with non-indolent cancer. On multivariate analysis, only the later remained as significant predictor (P = 0.0018).

Conclusions

Transrectal biopsy identified men with indolent tumors favorable for focal treatment in 50% of cases. MRI findings of ECE and extensive tumor involving more than half of the gland are associated with unfavorable features, and may be useful excluding patients from focal treatment. According to these data, endorectal MRI isn’t sufficient to localize small tumors for focal treatment.

Keywords: Focal therapy, Prostate biopsy, Prostate cancer, Prostate MRI

INTRODUCTION

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer in men and a leading health care issue in the United States [1]. Prostate cancer screening based on prostate-specific antigen (PSA) measurement is widely used and has led to a substantial increase in the detection of prostate cancer throughout the last decade [2,3]. Early detection has led to a well-recognized shift toward low-stage disease and the identification of a considerable number of men diagnosed with small tumors discovered at an earlier age, effectively adjusting the chronology of the disease [4].

Current curative treatment options for localized prostate cancer include surgery and radiation, both of which carry associated risks of treatment-related morbidity, including urinary, sexual, and bowel dysfunction[5]. For small, indolent prostate tumors, these approaches may be more aggressive than necessary. Efforts have been made to develop new modalities of curative treatment for prostate cancer that can minimize morbidity. More recently, interest has turned to the use of active surveillance and focal therapy strategies as effective alternative options for management. Active surveillance entails closely monitoring tumor development, without therapy, with the option to initiate treatment at a later time [6]. Focal therapy modalities encompass organ-sparing treatments using new technologies ideally intended to ablate subtotal portions of the prostate that contain tumor while minimizing related side effects. In the development of trials to study these treatments, patient selection plays a crucial role to assure that these organ-sparing approaches are not tumor sparing.

Selection criteria for active surveillance or focal therapy are strongly based on biopsy techniques designed to diagnose prostate cancer but not optimized to quantify the extent or grade of the disease. The design of most focal or hemi-ablation trials involve transrectal prostate biopsy, with or without prostate magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) criteria for assessing patients and determining eligibility. The value of MRI in evaluating men with low-stage disease has been shown to add incrementally to prognostic models, yet its role in localizing small tumors is less well defined [7].

We performed a retrospective analysis to test the hypothesis that candidates for organ-sparing management of prostate cancer would be accurately evaluated using diagnostic transrectal ultrasound (TRUS) biopsy techniques and prostate imaging with T2-weighted MRI. To this end, we analyzed a highly selected cohort of low-risk surgically treated patients with presurgical disease features favorable for active surveillance or focal therapy. We explored the utility of clinical features, including prostate biopsy and T2-weighted endorectal-coil MRI, to characterize this group of patients with regard to potential for organ-sparing management.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient Methods

After institutional review board approval was obtained, data were collected from a prospectively updated prostate cancer database. Search criteria included surgically treated men with low-risk biopsy criteria who had been studied with presurgical prostate MRI and had available whole-mount prostate pathology tissue maps after radical prostatectomy (RP) prepared in 4 mm sections as previously described [8]. This search identified 202 of 2985 men who underwent RP at our institution between April 2000 and March 2007. Biopsy selection criteria followed that of Goto [9]. One positive core with < 2 mm of cancer, no Gleason grade 4 or 5, PSA density ≤ 0.10, and clinical stage T2a or less. Patients treated preoperatively with androgen deprivation or radiation therapy were excluded. Patients were divided into indolent (Group 1) or non-indolent (Group 2) cancer based on the whole-mount RP specimen pathology [10]. Group 1 was defined as: no Gleason grade 4 or 5, organ confined, tumor volume < 0.5 cc, and negative surgical margins.

To determine the sampling accuracy of transrectal ultrasound biopsy by sextant, whole-mount maps were assessed for tumor involvement by sextant location: right/left, base/mid/apex. To determine possible sampling errors in the anterior portion of the gland, the base and mid were further subdivided into anterior and posterior, yielding 10 sectors altogether. Additional data recorded from each RP specimen was Gleason score, surgical margins, extracapsular extension (ECE), positive surgical margin, seminal vesicle invasion, and lymph node involvement. Location of tumor on prostate biopsy was compared with prostate maps.

Preoperative T2-weighted, endorectal-coil MRI studies were obtained no sooner than 6 weeks following prostate biopsy as per institutional practice. Radiographic interpretation was provided by experienced radiologists with a report that indicated localization and level of suspicion for tumor in the prostate, as described above. Extracapsular extension, seminal vesicles, and lymph nodes involved were also assessed. MR imaging was performed with a 1.5-T whole-body MR imager (GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI). Patients were examined in the supine position; the body coil was used for excitation, and the pelvic phased-array coil (GE Medical Systems) was used in combination with an expandable endorectal coil (Medrad, Pittsburgh, PA) for signal reception. Thin-section, high-spatial-resolution transverse, coronal, and sagittal T2-weighted fast spin-echo images of the prostate and seminal vesicles were obtained, and four signals acquired. T2-weighted images were post-processed to correct for the reception profile of the endorectal coil.

Statistical Methods

To allow for anatomical variation in the diagnostic properties of MRI, the prostate was categorized by quadrant: right/left, anterior/posterior. MRI interpretation for cancer suspicion by quadrant was scored as definitely no cancer (I), probably no cancer (II), indeterminate (III), probably cancer (IV), or definitely cancer (V). For sensitivity and specificity analyses, MRI scores were classified as 1/2/3 vs 4/5. The same 5-grade score was applied for the presence of extracapsular extension. Sensitivity and specificity of MRI at detecting cancer in each of 4 quadrants of the prostate was assessed using whole-mount maps as the gold standard.

To determine whether information obtained from an MRI could improve upon a standard prediction model to determine who has clinically significant cancer, we created a multivariable standard logistic regression model to predict group (non-indolent or indolent) using PSA and the extent of the biopsy (≤ 8 cores versus > 8 cores) as predictors. PSA was modeled with splines to account for the nonlinear relationship between PSA and outcome. Clinical stage and biopsy Gleason score were not included due to homogeneity of the cohort in regard to stage and grade. Predictive accuracy was assessed by area-under the curve (AUC), with bootstrap correction for overfit, to determine whether the addition of MRI information, including tumor extent and ECE involvement, could improve upon the predictive accuracy of the standard model. Tumor extent was defined as follows: MRI examinations that received a score of I or II in all 4 quadrants were defined as minimal involvement; a score of IV or V in 2 or more quadrants was defined as extensive involvement; all other studies were classified as moderate involvement. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata 10.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX) with P < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Preoperative and RP pathology data are shown in Table 1. Of the 202 patients included in our analyses, 101 patients (50%) met postoperative criteria for indolent disease on final RP pathology. There were no important differences between groups with regard to age, PSA serum levels, and clinical stage. Median prostate volume from MRI in Group 2 patients was smaller than in Group 1 patients (33 cc versus 41 cc, P = 0.02). The median number of prostate biopsy cores per patient was 11 (range 6–22); 136 men (67%) and 92 men (47%) had more than 8 and 12 or more cores, respectively. Thirty-five men (17%) had undergone a prior biopsy procedure, with 7 (3.5%) having undergone 2 or more. Gleason score in RP specimen was upgraded in 32% (n=64) of patients. Prostate cancers of pathologic stage pT3 or pT4 were found in 10% (n=21) of all patients. Preoperative biopsy correctly identified the location of the index tumor in 98 patients (49%). Overall, multifocal and bilateral tumors were present in 81% and 68% of patients, respectively. The posterior mid gland was the most common tumor location (n = 126). The prostate apex was involved in 33% (n=33) and 59% (n=60) of the Group 1 and Group 2 patients, respectively, and was the only site of tumor in 8% (3 of 37) of patients with tumor at only one location.

Table 1.

Preoperative patient characteristics and pathology data following radical prostatectomy

| Characteristic | All patients N = 202 |

Group 1 (indolent) n = 101 |

Group 2 (non-indolent) n = 101 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age, yr | 59 (54–63) | 57 (53–63) | 59 (55–64) |

| Median PSA, ng/mL | 5.2 (3.8–6.7) | 5.1 (3.8–7.0) | 5.3 (3.9–6.7) |

| Median prostate volume from MRI, cc | 38.3 (26–52) | 41 (29–59) | 33 (25–47) |

| Median 5-year preoperative nomogram recurrence probability, % | 8.6 (8.1–10.6) | 8.5 (8.0–10.5) | 8.7 (8.1–10.6) |

| Median number of cores | 11 (8–13) | 12 (8–13) | 10 (7–13) |

| Extended biopsy (>8 cores), n (%) | 136 (67%) | 70 (69%) | 66 (66%) |

| Clinical stage, n (%) | |||

| T1c | 174 (86) | 88(87) | 86 (85) |

| T2a | 28 (14) | 13 (13) | 15 (15) |

| Tumor extent from MRI, n (%) | |||

| Minimal involvement | 19 (9) | 16 (16) | 3 (3) |

| Moderate involvement | 167 (83) | 84 (83) | 83 (82) |

| Extensive involvement | 16 (8) | 1 (1) | 15 (15) |

| ECE involvement from MRI, n (%) | 27 (13) | 8 (8) | 19 (19) |

| Gleason score | |||

| ≤ 6 | 138 (68) | 101 (100) | 37 (37) |

| 7 | 63 (31) | 0 (0) | 63 (62) |

| ≥ 8 | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Positive surgical margins | 15 (7) | 0 (0) | 15 (15) |

| Extraprostatic extension | 19 (9) | 0 (0) | 19 (19) |

| Seminal vesicle invasion | 3 (1) | 0 (0) | 3 (3) |

| Pathologic stage | |||

| pT0 | 13 (6) | 13 (13) | 0 |

| pT2a | 45 (22) | 36 (36) | 9 (9) |

| pT2b | 104 (51) | 43 (43) | 61 (60) |

| pT2c | 19 (9) | 9 (9) | 10 (10) |

| ≥ pT3a | 21 (10) | 0 (0) | 21 (21) |

| Median tumor volume, cc (IQR) | 0.26 (0.04–0.82) | 0 (0.01–0.22) | 0.82 (0.42–1.38) |

ECE – extracapsular extension; MRI – magnetic resonance imaging; PSA – prostate-specific antigen.

Values in parentheses are ranges, unless specified otherwise.

Table 3 shows the sensitivity and specificity of MRI for each of 4 prostate locations: right/left, anterior/posterior. When MRI level of suspicion scores were assessed into grade I/II/III versus grades IV/V, the sensitivity ranged from 2% to 20%, and specificity ranged from 91% to 95%. The sensitivity and specificity of extracapsular extension was 58% and 100%, respectively. Negative predictive value of MRI for overall extent of tumor was 58%.

Table 3.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis for prediction of non-indolent cancer

| Predictor | Odds ratio | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| PSA | * | * | 0.3 |

| Extent of biopsy | 0.7 | ||

| Limited | Ref | Ref | |

| Extended | 0.87 | 0.46 – 1.66 | |

| ECE from MRI | 0.4 | ||

| No | Ref | Ref | |

| Yes | 1.51 | 0.57 – 4.01 | |

| Tumor extent from MRI | 0.0018 | ||

| Minimal | Ref | Ref | |

| Moderate | 5.39 | 1.49 – 19.5 | |

| Extensive | 70.5 | 6.20 – 802 |

CI – confidence interval; ECE – extracapsular extension; MRI – magnetic resonance imaging; PSA – prostate-specific antigen; Ref – reference.

Odds ratio for PSA not presented because PSA was modeled with splines to account for the nonlinear relationship between PSA and outcome.

Regarding the MRI-detected extent of tumor, 19 patients (9%) were classified as having minimal involvement, 167 (83%) moderate involvement, and 16 (8%) extensive disease. Although the majority of patients in both Groups were found to have moderate tumor according to the MRI tumor extent, more patients were classified as tumor free in Group1 (16% [n=16]) than Group 2 (3% [n=3]). Similarly, more patients in Group 2 as compared to Group 1 were classified as having extensive tumor on MRI (15% [n=15] and 1% [n=1], respectively). Overall, 27 (13%) patients were classified as having extracapsular extension; 8 (8%) in Group 1 and 19 (19%) in Group 2.

On univariate analysis, patients with ECE detected (odds ratio 2.7, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.2–6.5, P = 0.027) and tumor extent (moderate: odds ratio 5.3, 95% CI 1.5–18.8; extensive: odds ratio 80.0, 95% CI 7.5–856, P = 0.001) on MRI were more likely to have pathologic evidence of non-indolent cancer. On multivariable analysis (Table 4), only tumor extent from MRI remained a strong significant predictor (moderate: odds ratio 5.39, 95% CI 1.49–19.5; extensive: odds ratio 70.5, 95% CI 6.20–802, global P = 0.0018).

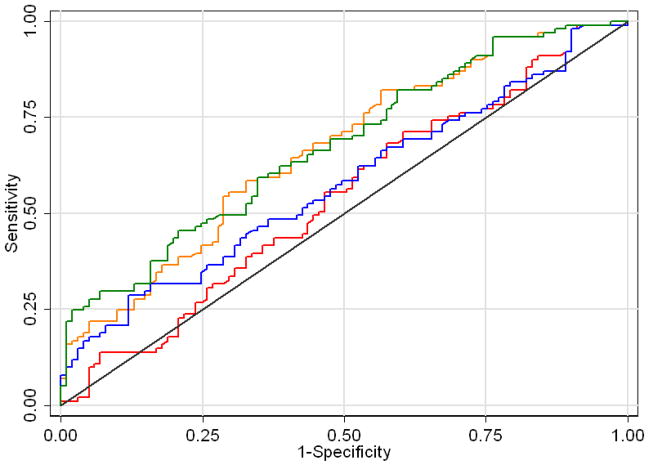

When additional information obtained from the MRI was included in the multivariable logistic regression model, a small improvement in predictive accuracy was observed. The multivariable base model that included PSA and extent of biopsy had an AUC of 0.489, which increased to 0.616 when including MRI-detected ECE and to 0.525 when including MRI-detected tumor extent. Adding both MRI-detected ECE and tumor extent increased the AUC to 0.624 (Fig. 1). We conducted a sensitivity analysis to check whether small, but high grade tumors were impacting our results as these tumors are difficult for MRI to detect. When clinically significant tumors were restricted to those with tumor volume greater than 0.5cm, extracapsular extension, seminal vesicle invasion, lymph node involvement or positive surgical margins, 19 additional patients were classified as having indolent disease, for a total of 82 patients with clinically significant cancer. We repeated our analysis considering these patients as having indolent cancer, and there was no important difference in results. The predictive accuracy of the model using this definition of clinically significant cancer was 0.581, increasing to 0.664 and 0.619 with the addition of MRI-detected tumor extent and MRI-detected ECE, respectively, and to 0.675 with both additional predictors.

Figure 1.

Area-under-the-curve of 4 models. Base model (red line) includes prostate-specific antigen (with cubic splines), number of cores taken from biopsy. Other models include MRI-detected extracapsular extension (ECE, blue line), tumor extent from MRI (orange line), or both (green line).

COMMENTS

Widespread early detection of prostate cancer by the use of PSA and digital rectal examination has helped to detect prostate cancer at an earlier stage. A proportion of these tumors are of limited biological risk to patients, prompting the development of active surveillance protocols as an option for management. Yet a number of patients on active surveillance will demonstrate progression of disease, arguably missing the opportunity for curative treatment [11,12]. Underestimation of tumor characteristics with biopsy and clinical features is not uncommon [13,14]. Although oncologically efficient, current treatment options can affect sexual, urinary, and bowel function, which may be avoidable in a subset of patients. The issue remains how to appropriately characterize and stratify patients with prostate cancer at the time of initial diagnosis and provide effective treatment options for those who would benefit. Increasingly, options for treatment have become less invasive.

Focal therapy modalities for prostate cancer encompass prostate-sparing techniques using new technologies such as cryotherapy, immunocryotherapy, high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU), photodynamic therapy (PDT), and radiofrequency ablation. Purported benefits of these techniques allow for ablation of the tumor area only and not the entire prostate, potentially minimizing treatment-related side effects. To be effective, accurate tumor targeting and patient selection are needed in the development of clinical trials.

Focal therapy is treatment to a sub-volume of the prostate; therefore ideal patients would include those with limited unilateral disease. However, multifocal prostate cancer is common, present in 67% to 87% of all pathology specimens after RP, even among men with small cancer volume (< 0.5 cc) [15]. Although related to a more aggressive disease, multifocal prostate cancer does not necessarily represent a contraindication for focal therapy. An index tumor (defined as the largest) is frequently identified and represents the most important determinant of prognosis. Even when the cancer is multifocal, most non-index tumors appear to be biologically indolent based on their small size and low grade. Ohori et al. found that among patients with multifocal disease, 80% of the total tumor volume was present in the index tumor. ECE arose from the largest cancer in 92% of patients [16]. It is generally accepted that the tumor progression is mediated by index tumors of larger volume (> 0.5 cc) and higher grade (Gleason score 7). To prove effective, accurate localization and characterization of the index tumor for candidate focal therapy patients is needed.

Several features have been proposed as important determinants for success with focal treatment 4. Unilateral tumors allow for limited treatment to be applied with risk to one neurovascular bundle. Using the SEARCH database, Scales et al. showed that only 35% of the unilateral tumors on prostate biopsy had unilateral disease in the RP pathology [17]. In the present study focal and unilateral cancer was seen in 39 patients (18.7%) and 67 patients (32%), respectively. Tumor volume represents another important feature. High-volume tumor in needle biopsy correlates with the extent of tumor on the RP specimen; however, the converse is not always true [18]. In this series, 35% of tumors had a volume > 0.5 cc, which excluded them from the indolent prostate cancer group. Tumor grade performs well as a predictor of biochemical failure, systemic recurrence, and overall survival in prostate cancer. Upgrading of tumors from biopsy to final pathology is well documented and in our study, 68 patients (33%) had an upgrade in RP Gleason score similar to that seen in other series of similar, though less selected, patients [19,20]. Inaccuracy of standard diagnostic TRUS biopsy for identifying higher-risk features of prostate tumors supports the need for development of improved evaluative techniques when considering surveillance or focal therapy.

Transperineal stereotactic mapping biopsies using a brachytherapy template guide have been used to provide more detailed spatial and histologic information but are more invasive. Obtaining accurate data with this strategy requires 5-mm spacing of samples under general anesthesia and carries a greater risk of urinary retention and voiding dysfunction [21–23].

Image-based localization and treatment techniques represent an optimal approach to management. Among the current imaging modalities MRI is perhaps the most well studied and most promising. MRI sensitivity for disease detection ranges from 40% to 90% and reports for detection of tumors > 1 cm are as high as 85% [24–26]. The accuracy of MRI for smaller tumors is less established. MRI information assessed using 4 prostate quadrant localization demonstrated modest sensitivity ranging from 2% to 20% but strong specificity from 91% to 95% yielding an overall negative predictive value of 58%. MRI improved the prediction for minimal disease that included clinical and pathologic preoperative data. This is particularly of interest in this group of patients with homogenous clinical parameters that lack discriminatory features other than serum PSA. Our data does not support the use of T2 weighted endorectal MRI to localize small tumors for focal therapy but suggest that MRI is useful for excluding patients from focal therapy trials based on radiographic evidence of more extensive disease.

Limitations in this analysis include those of retrospective studies. Only surgical patients with preoperative MRI were included, indicating clinical selection of patients by the treating surgeon. As a surgical series these patients may not accurately reflect the biology found among patients managed with active surveillance. TRUS biopsy procedures were non-standardized, including samples obtained from referring physicians. Sampling adequacy was assessed using number of cores, and univariate analysis—which stratified patients by the extent of their biopsy—did not identify biopsy number as significant. MRI was limited to T2-weighted imaging, which may differ from results that are possible with higher magnetic field strengths or multiparametric imaging capabilities that include diffusion weighted, dynamic contrast, or spectroscopy capabilities [27]. Localization data was analyzed using a quadrant system instead of sextant due to the difficulties in co-localizing segments of base, mid, and apex between MRI and pathology specimens, whereas planes of laterality and AP dimensions are well defined and readily translatable. For many studies involving correlation of imaging studies with prostate pathology, the issue of accurate co-localization is problematic because processing of pathologic specimens may involve anatomic sectioning in planes dissimilar to the imaging planes of MRI.

CONCLUSION

Current clinical criteria for identifying men with prostate cancer eligible for organ-sparing management strategies correctly indicate indolent cancer in 50% of cases when using initial diagnostic TRUS biopsy criteria. T2-weighted MRI is helpful in further evaluating these patients to indicate those with greater likelihood of having more extensive disease than suspected, yet is not sufficient to localize these small tumors for focal therapy trials.

Table 2.

Sensitivity and specificity of MRI by prostate location

| Prostate Location | MRI Score | Cancer Present on Whole Mount Maps | Sensitivity / Specificity (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Yes | No | I/II/III vs IV/V | ||

| Left anterior | Unlikely cancer (I/II) | 42 | 69 | 16% / 91% |

| Indeterminate (III) | 45 | 20 | ||

| Likely cancer (IV/V) | 17 | 9 | ||

| Right anterior | Unlikely cancer (I/II) | 35 | 78 | 2% / 95% |

| Indeterminate (III) | 55 | 27 | ||

| Likely cancer (IV/V) | 2 | 5 | ||

| Left posterior | Unlikely cancer (I/II) | 47 | 36 | 7% / 95% |

| Indeterminate (III) | 87 | 19 | ||

| Likely cancer (IV/V) | 10 | 3 | ||

| Right posterior | Unlikely cancer (I/II) | 55 | 38 | 20% / 93% |

| Indeterminate (III) | 60 | 17 | ||

| Likely cancer (IV/V) | 28 | 4 | ||

Acknowledgments

Supported by The Sidney Kimmel Center for Prostate and Urologic Cancers

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. Cancer Statistics, 2008. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58:71–96. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cooperberg MR, Lubeck DP, Meng MV, et al. The changing face of low-risk prostate cancer: trends in clinical presentation and primary management. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2141–2149. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.10.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carroll PR. Early stage prostate cancer--do we have a problem with over-detection, overtreatment or both? J Urol. 2005;173:1061–1062. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000156838.67623.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooperberg MR, Moul JW, Carroll PR. The changing face of prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8146–8151. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.9751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eggener SE, Scardino PT, Carroll PR, et al. Focal therapy for localized prostate cancer: a critical appraisal of rationale and modalities. J Urol. 2007;178:2260–2267. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.08.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klotz LH, Nam RK. Active surveillance with selective delayed intervention for favorable risk prostate cancer: clinical experience and a ‘number needed to treat’ analysis. Can J Urol. 2006;13 (Suppl 1):48–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shukla-Dave A, Hricak H, Kattan MW, et al. The utility of magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy for predicting insignificant prostate cancer: an initial analysis. BJU Int. 2007;99:786–793. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.06689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yossepowitch O, Sircar K, Scardino PT, et al. Bladder neck involvement in pathological stage pT4 radical prostatectomy specimens is not an independent prognostic factor. J Urol. 2002;168:2011–2015. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64284-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goto Y, Ohori M, Arakawa A, et al. Distinguishing clinically important from unimportant prostate cancers before treatment: value of systematic biopsies. J Urol. 1996;156:1059–1063. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ohori M, Wheeler TM, Dunn JK, et al. The pathological features and prognosis of prostate cancer detectable with current diagnostic tests. J Urol. 1994;152:1714–1720. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)32369-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Epstein JI, Walsh PC, Carter HB. Dedifferentiation of prostate cancer grade with time in men followed expectantly for stage T1c disease. J Urol. 2001;166:1688–1691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stattin P, Holmberg E, Bratt O, et al. Surveillance and deferred treatment for localized prostate cancer. Population based study in the National Prostate Cancer Register of Sweden. J Urol. 2008;180:2423–9. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.08.044. discussion 2429–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hardie C, Parker C, Norman A, et al. Early outcomes of active surveillance for localized prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2005;95:956–960. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller DC, Gruber SB, Hollenbeck BK, et al. Incidence of initial local therapy among men with lower-risk prostate cancer in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1134–1141. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meiers I, Waters DJ, Bostwick DG. Preoperative prediction of multifocal prostate cancer and application of focal therapy: review 2007. Urology. 2007;70:3–8. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.06.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ohori M, Eastham JA, Koh H, et al. Is focal therapy reasonable in patients with early stage prostate cancer (CaP)—an analysis of radical prostatectomy (RP) specimens. J Urol. 2006;175:507, abstract 1574. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scales CD, Jr, Presti JC, Jr, Kane CJ, et al. Predicting unilateral prostate cancer based on biopsy features: implications for focal ablative therapy--results from the SEARCH database. J Urol. 2007;178:1249–1252. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.05.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bostwick DG, Myers RP, Oesterling JE. Staging of prostate cancer. Semin Surg Oncol. 1994;10:60–72. doi: 10.1002/ssu.2980100110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pinthus JH, Witkos M, Fleshner NE, et al. Prostate cancers scored as Gleason 6 on prostate biopsy are frequently Gleason 7 tumors at radical prostatectomy: implication on outcome. J Urol. 2006;176:979–84. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.04.102. discussion 984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chun FK, Briganti A, Graefen M, et al. Development and external validation of an extended repeat biopsy nomogram. J Urol. 2007;177:510–515. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crawford ED, Wilson SS, Torkko KC, et al. Clinical staging of prostate cancer: a computer-simulated study of transperineal prostate biopsy. BJU Int. 2005;96:999–1004. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05801.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Merrick GS, Taubenslag W, Andreini H, et al. The morbidity of transperineal template-guided prostate mapping biopsy. BJU Int. 2008;101:1524–1529. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moran BJ, Braccioforte MH, Conterato DJ. Re-biopsy of the prostate using a stereotactic transperineal technique. J Urol. 2006;176:1376–81. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.06.030. discussion 1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hricak H. MR imaging and MR spectroscopic imaging in the pre-treatment evaluation of prostate cancer. Br J Radiol. 2005;78(Spec No 2):S103–11. doi: 10.1259/bjr/11253478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kozlowski P, Chang SD, Jones EC, et al. Combined diffusion-weighted and dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI for prostate cancer diagnosis--correlation with biopsy and histopathology. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2006;24:108–113. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kirkham AP, Emberton M, Allen C. How good is MRI at detecting and characterising cancer within the prostate? Eur Urol. 2006;50:1163–74. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.06.025. discussion 1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang L, Hricak H, Kattan MW, et al. Prediction of organ-confined prostate cancer: incremental value of MR imaging and MR spectroscopic imaging to staging nomograms. Radiology. 2006;238:597–603. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2382041905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]