Abstract

Mycobacterium chelonae lung disease is very rare. We report a case of lung disease caused by M. chelonae in a previously healthy woman. A 69-year-old woman was referred to our hospital because of hemoptysis. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest revealed bronchiolitis associated with bronchiectasis in the lingular division of the left upper lobe. Nontuberculous mycobacteria were isolated three times from sputum specimens. All isolates were identified as M. chelonae by various molecular methods that characterized rpoB and hsp65 gene sequences. Although some new lesions including bronchiolitis in the superior segment of the left lower lobe developed on the chest CT scan 35 months after diagnosis, she has been followed up without antibiotic therapy because of her mild symptoms. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case of M. chelonae lung disease in Korea in which the etiologic organisms were confirmed using molecular techniques.

Keywords: Nontuberculous Mycobacteria, Bronchiectasis, Mycobacterium chelonae

Introduction

Nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) are generally classified as either slow or rapid growers. Rapidly growing mycobacteria (RGM), which are characterized by visible growth on solid media within 7 days, include three clinically relevant species, Mycobacterium fortuitum, M. abscessus, and M. chelonae1-3. All are environmental microorganisms found in soil, bioaerosols, and natural and chlorinated water1-3. RGM lung disease is predominantly due to M. abscessus (80% of cases) and M. fortuitum (15% of cases)4,5. M. chelonae usually causes skin, bone, and soft tissue infections and is a very rare respiratory pathogen6,7. Here, we report a case of M. chelonae lung disease associated with bronchiectasis in a previously healthy woman.

Case Report

In April 2008, a 69-year-old woman was referred to our hospital because of hemoptysis. She had been healthy until one month prior, when intermittent hemoptysis developed. The patient had no smoking history or other medical history. On examination, the patient appeared well. Her weight was 45 kg, height 156.2 cm, temperature 36.2℃, blood pressure 133/75 mm Hg, pulse 73 beats per minute, and oxygen saturation 100% while breathing ambient air. Laboratory results were normal. A human immunodeficiency virus antibody test was negative.

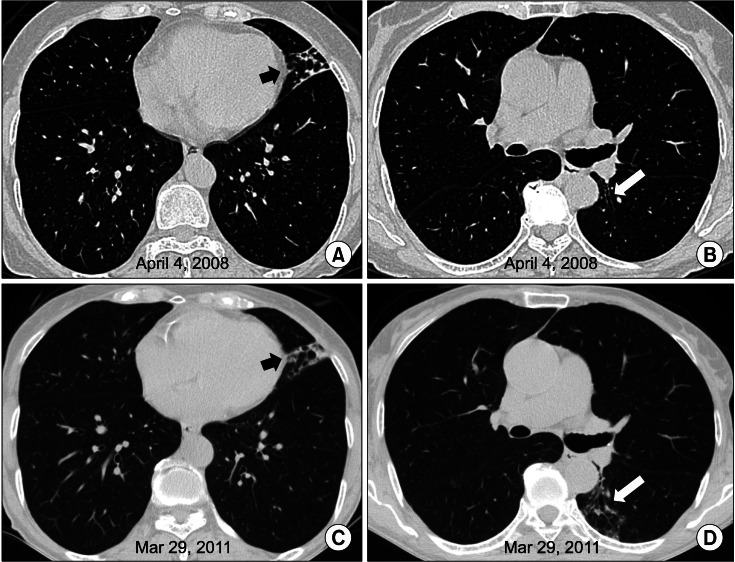

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest revealed bronchiectasis and bronchiolitis in the lingular division of the left upper lobe (Figure 1A, B). There was no evidence of cystic fibrosis or other common causes of bronchiectasis. NTM were isolated three times from sputum specimens.

Figure 1.

A 69-year-old woman with bronchiectasis and nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease caused by Mycobacterium chelonae. (A) A transverse computed tomography (CT) scan (2.5-mm-section thickness) at the time of presentation reveals bronchiectasis and bronchiolitis in the lingular division of the left upper lobe. (B) Mild bronchiectasis was noted in the superior segment of the left lower lobe at the time of presentation. (C) A CT scan of the same patient at 3 years after diagnosis reveals mild progression of peribronchial infiltration on the lingular division of the left upper lobe. (D) There was newly appearing bronchiolitis in the superior segment of the left lower lobe.

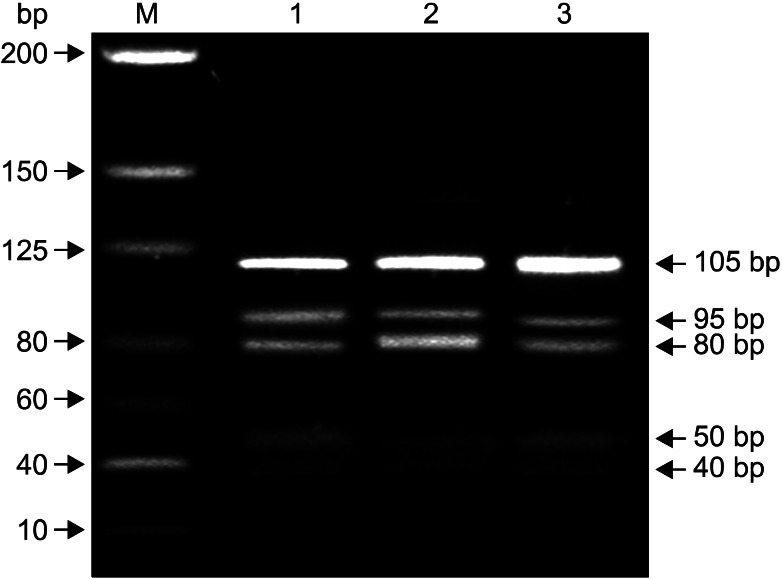

NTM species were identified using a polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis (PRA) based on the partial region of the rpoB gene8. Colonies were scraped, and genomic DNA of the isolate was extracted using a commercial kit (QIAamp DNA Mini kit; Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Amplification of the partial rpoB gene (360 bp) was performed using primers Rpo5' (5'-TCAAGGAGAAGCGCTACGA-3') and Rpo3' (5'-GGATGTTGATCAGGGTCTGC-3')8 with subsequent digestion with 5 units of Msp I (New England BioLabs, Beverly, MA, USA) for 3 hours at 37℃. The digestion mixtures were analyzed by 3% (w/v) agarose gel electrophoresis. DNA size markers, pBR322-MspI-digested DNA (New England BioLabs) were used to enable estimation of DNA fragment size. The PRA results were determined by comparing their restriction patterns with those available in the National Center for Biotechnology Information GenBank database9 and referred to as described by Lee et al.8 for the rpoB-PRA. The rpoB amplicon restricted by MspI resulted in fragment sizes of 105, 95, 80, 50, and 40 bp in two serial cultures (Figure 2). The rpoB-PRA patterns of those cultures exactly matched the known restriction fragment pattern of the reference strain of M. chelonae subsp. chelonae ATCC35749.

Figure 2.

Electrophoresis of the polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis (PRA) of the rpoB gene involving digestion with Msp I. Mycobacteria isolated from two serial specimens generated the fragments of 105, 95, 80, 50, and 40 bp, which were identical to those of Mycobacterium chelonae subsp. chelonae ATCC35749. M, size marker; Lanes 1 and 2, patterns of rpoB-PRA from two serial samples isolated; Lane 3, the matched pattern of the reference strain M. chelonae subsp. chelonae ATCC35749.

The identification of these NTM isolates was further confirmed by DNA sequence analysis of the partial rpoB gene (723 bp) using primers MycoF (5'-GGCAAGGTCACCCCGAAGGG-3') and MycoR (5'-AGCGGCTGCTGGGTGATCATC-3')10 and the partial hsp65 gene (439 bp) using primers Tb11 (5'-ACCAACGATGGTGTGTCCAT-3') and Tb12 (5'-CTTGTCGAACCGCATACCCT-3'). The results revealed sequence similarity (above 99.9%) with M. chelonae for the rpoB gene (GenBank accession no. EU109300.1) and hsp65 gene (GenBank accession no. U55832).

Finally, the patient was diagnosed with M. chelonae lung disease. Antibiotic therapy was not initiated because of her mild symptoms. Three years after diagnosis of M. chelonae lung disease, follow-up chest CT was performed. Although there was mild progression of peribronchial infiltration on the lingular division of the left upper lobe and newly appeared bronchiolitis in the superior segment of the left lower lobe (Figure 1C, D), she did not complain of aggravation of her symptoms.

Discussion

The nomenclature of RGM has changed frequently and has been a source of confusion for clinicians. For instance, within the past approximately 20 years, M. abscessus, the most common RGM respiratory pathogen, was labeled as M. cheloneii subsp. abscessus, M. chelonae subsp. abscessus, and finally, in 1992, M. abscessus11. Unfortunately, some mycobacterial laboratories still report M. abscessus isolates as M. chelonae complex or M. chelonae/abscessus group without further species identification12,13. The species identification is important because therapy differs significantly depending on the RGM species obtained. Because M. chelonae is an extremely rare cause of pulmonary disease, most respiratory isolates that are identified as M. chelonae/abscessus complex can be reasonably assumed to be M. abscessus isolates2.

Identifying RGM to the species level is very important1-3. Biochemical tests that assess phenotype characteristics have commonly been used by clinical laboratories to characterize RGM. However, these are time-consuming and do not always lead to identification of the organism to the species level2,3. High-performance liquid chromatography, which is a useful method for identifying slowly growing NTM, may not enable separation of M. chelonae and M. abscessus2,3. Molecular methods can provide reliable and rapid identification of RGM1. In this study, the M. chelonae isolates were identified using rpoB gene based-PRA and sequence analysis of the rpoB and hsp65 genes.

Skin, bone, and soft tissue disease are the most important clinical manifestations of M. chelonae infection. Disseminated M. chelonae infection can also occur in immunocompromised patients1. M. chelonae is an increasingly recognized cause of keratitis, especially after injury with a foreign body or following office ophthalmologic procedures1. However, M. chelonae is a much less frequent cause of lung disease than M. abscessus1-3.

Reported cases of M. chelonae lung disease are usually middle-aged or elderly women with no other co-existing parenchymal lung disease. The symptoms and radiographic presentation of M. chelonae lung disease are similar to those of other RGM lung diseases5. Bronchiectasis, nodules, and consolidation are the most common CT features14.

It is important to distinguish M. chelonae from M. abscessus because therapy for M. chelonae is potentially easier than for M. abscessus infection1. M. chelonae is resistant to anti-tuberculosis agents but is susceptible to a number of traditional anti-bacterial agents such as tobramycin (100%), clarithromycin (100%), linezolid (90%), imipenem (60%), amikacin (50%), clofazimine, doxycycline (25%), and ciprofloxacin (20%)1. In addition, inducible resistance to clarithromycin which is conferred by an erm (41) gene is found in M. abscessus but is absent from M. chelonae15.

In conclusion, M. chelonae should be considered a possible etiologic pathogen of the nodular bronchiectatic form of NTM lung disease, despite the rarity of pulmonary M. chelonae infection. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first documented case of M. chelonae lung disease in an immunocompetent adult in Korea in which the etiologic organism was confirmed using molecular methods that characterized rpoB and hsp65 gene sequences.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Mid-career Researcher Program through a National Research Foundation grant funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (2011-0015546).

References

- 1.Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, Catanzaro A, Daley C, Gordin F, et al. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:367–416. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200604-571ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Daley CL, Griffith DE. Pulmonary disease caused by rapidly growing mycobacteria. Clin Chest Med. 2002;23:623–632. doi: 10.1016/s0272-5231(02)00021-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Colombo RE, Olivier KN. Diagnosis and treatment of infections caused by rapidly growing mycobacteria. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;29:577–588. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1085709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wallace RJ, Jr, Swenson JM, Silcox VA, Good RC, Tschen JA, Stone MS. Spectrum of disease due to rapidly growing mycobacteria. Rev Infect Dis. 1983;5:657–679. doi: 10.1093/clinids/5.4.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Griffith DE, Girard WM, Wallace RJ., Jr Clinical features of pulmonary disease caused by rapidly growing mycobacteria: an analysis of 154 patients. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;147:1271–1278. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/147.5.1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh N, Yu VL. Successful treatment of pulmonary infection due to Mycobacterium chelonae: case report and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;14:156–161. doi: 10.1093/clinids/14.1.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goto T, Hamaguchi R, Maeshima A, Oyamada Y, Kato R. Pulmonary resection for Mycobacterium chelonae infection. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;18:128–131. doi: 10.5761/atcs.cr.11.01689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee H, Park HJ, Cho SN, Bai GH, Kim SJ. Species identification of mycobacteria by PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism of the rpoB gene. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:2966–2971. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.8.2966-2971.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benson DA, Karsch-Mizrachi I, Lipman DJ, Ostell J, Wheeler DL. GenBank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D21–D25. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adekambi T, Drancourt M. Dissection of phylogenetic relationships among 19 rapidly growing Mycobacterium species by 16S rRNA, hsp65, sodA, recA and rpoB gene sequencing. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2004;54(Pt 6):2095–2105. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.63094-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kusunoki S, Ezaki T. Proposal of Mycobacterium peregrinum sp. nov., nom. rev., and elevation of Mycobacterium chelonae subsp. abscessus (Kubica et al.) to species status: Mycobacterium abscessus comb. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1992;42:240–245. doi: 10.1099/00207713-42-2-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee MR, Keng LT, Shu CC, Lee SW, Lee CH, Wang JY, et al. Risk factors for Mycobacterium chelonae-abscessus pulmonary disease persistence and deterioration. J Infect. 2012;64:228–230. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2011.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scarparo C, Piccoli P, Rigon A, Ruggiero G, Nista D, Piersimoni C. Direct identification of mycobacteria from MB/BacT alert 3D bottles: comparative evaluation of two commercial probe assays. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:3222–3227. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.9.3222-3227.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hazelton TR, Newell JD, Jr, Cook JL, Huitt GA, Lynch DA. CT findings in 14 patients with Mycobacterium chelonae pulmonary infection. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;175:413–416. doi: 10.2214/ajr.175.2.1750413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nash KA, Brown-Elliott BA, Wallace RJ., Jr A novel gene, erm(41), confers inducible macrolide resistance to clinical isolates of Mycobacterium abscessus but is absent from Mycobacterium chelonae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:1367–1376. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01275-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]