Abstract

Purpose

The objective of this study was to elucidate the role of collagen membranes (CMs) when used in conjunction with bovine hydroxyapatite particles incorporated with collagen matrix (BHC) for lateral onlay grafts in dogs.

Methods

The first, second, and third premolars in the right maxilla of mongrel dogs (n=5) were extracted. After 2 months of healing, two BHC blocks (4 mm×4 mm×5 mm) were placed on the buccal ridge, one with and one without the coverage by a CM. The animals were sacrificed after 8 weeks for histometric analysis.

Results

The collagen network of the membranes remained and served as a barrier. The quantity and quality of bone regeneration were all significantly greater in the membrane group than in the no-membrane group (P<0.05).

Conclusions

The use of barrier membranes in lateral onlay grafts leads to superior new bone formation and bone quality compared with bone graft alone.

Keywords: Alveolar ridge augmentation, Bone substitutes, Collagen, Guided tissue regeneration, Membranes

INTRODUCTION

The guided bone regeneration (GBR) technique stems from the concept referred to as 'guided tissue regeneration' (GTR), in which the desired cells (i.e., osteoblasts) from an adjacent native tissue source can be directed toward and encouraged to grow into a protected space with the aid of an occlusive barrier membrane [1]. However, some differences exist between GBR and GTR. When the GTR technique is used for periodontal regeneration, the ingrowth of the junctional epithelium should be prevented in the periodontal defect [2]. This occurs because the epithelium that occupies the exposed root surface acts as a hindrance to periodontal regeneration. In contrast, the main concern with GBR is the prevention of connective tissue rather than epithelial growth [3].

Furthermore, it has been demonstrated consistently that the grafted site for GBR may be completely separated and protected from the external environment by the periosteum [4]. It has been indicated that using periosteal flaps as the primary closure for graft materials can promote both wound healing and the creation of new bone [5]. The current data suggest that the periosteum contains an abundance of blood vessels and undifferentiated mesenchymal cells, which are essential for correct bone regeneration [6]. Moreover, a barrier membrane covering the graft material may obstruct the supply of blood and progenitor cells from the periosteum, and the undamaged periosteum may be helpful in wound healing [7-9].

The various bone-graft biomaterials that have been implemented for space maintenance can be categorized into two types: particle and block. In many clinical cases, particle-type biomaterials are advantageous because they readily adapt to the irregular dimensions of a defect and are appropriately porous. However, their lack of stability means that the particles can be displaced from the defect during the healing phase. Combining the bone graft with a membrane not only increases the stability of the particular graft material but also provides the appropriate space for bone regeneration [10]. The block-type biomaterial can maintain its shape without the aid of an additional barrier membrane, including grafted sites upon which there is an external pressure or load. However, when compared to the particle-type, block-type biomaterials are less flexible and need to be trimmed to fit the irregular defect surface [11].

To overcome the weaknesses of both types of biomaterials, a soft-type block in which bovine hydroxyapatite (BH) particles are incorporated into a collagen matrix (BHC; Bio-Oss collagen, Geistlich Pharma AG, Wolhusen, Switzerland), has been developed. It was hypothesized that the collagen-occupying spaces between the graft particles in BHC would provide the matrix for ingrowth of tissues and maintain the stability of grafted biomaterials by binding to the particles. When compared to the other hard-type blocks, the ease with which the BHC block can be condensed and adapted to fit various types of defects aids its manipulation in clinical situations. BHC has been used mainly for ridge preservation following tooth extraction, and its effectiveness in bone regeneration and ridge preservation without any immunological side effects has been well documented [12,13]. The aforementioned advantages of BHC potentially make it a good scaffold even for unfavorable defects such as vertically resorbed ridges, which have few healing sources. Therefore, when the intact periosteum is secured in the sites that received BHC, whether or not it is beneficial to use a membrane barrier remains to be established.

The objective of this study was thus to elucidate whether the collagen membrane (CM) plays a beneficial role when used in conjunction with BHC for lateral onlay grafts in dogs. The study was conducted on the basis of two hypotheses: 1) intact periosteum alone can exclude unwanted soft tissue into the grafted BHC, and 2) BHC covered with intact periosteum can maintain the space required for bone regeneration without dissipation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Five male mongrel dogs, 20 to 24 months old and weighing approximately 15 kg, were used. All of the experimental animals had a sound permanent dentition. Animal selection and management, surgical protocol, and preparation were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, Yonsei Medical Center, Seoul, Korea.

Study design

Commercially available BHC (Bio-Oss Collagen, Geistlich Pharma AG) and resorbable CM composed of bilayered, non-cross-linked porcine types I and III collagen (BioGide, Geistlich Pharma AG) were used. BHC (8 mm×4 mm×5 mm) was divided into two rectangular blocks 4 mm×4 mm×5 mm, and CM was prepared in square layers 12.5 mm×12.5 mm. Graft sites were allocated to one of two experimental groups, as follows:

Membrane-cover group (n=5); lateral onlay graft with BHC and CM.

No-membrane-cover group (n=5); lateral onlay graft with BHC alone.

Surgical protocol

All surgical procedures were performed under general and local anesthesia. The animals were injected intravascularly with atropine (0.05 mg/kg; Kwangmyung Pharmaceutical, Seoul, Korea) and intramuscularly with xylazine (2 mg/kg; Rompun, Bayer Korea, Seoul, Korea) and ketamine hydrochloride (10 mg/kg; Ketalar, Yuhan, Seoul, Korea). General anesthesia was maintained by inhalation of 2% enflurane (Gerolan, Choongwae Pharmaceutical, Seoul, Korea). Routine dental infiltration anesthesia with lidocaine was used at the surgical sites (2% lidocaine hydrochloride-epinephrine 1:100,000, Kwangmyung Pharmaceutical). The maxillary first, second, and third premolars on the right upper jaw were extracted, and graft surgery was performed after 8 weeks of healing. A midcrestal incision was made from the first molar to the canine, and two vertical incisions were made at the mesial side of the first molar and distal side of the canine via a vestibular divergent releasing incision. A full-thickness mucoperiosteal flap was raised and retracted to expose the lateral site. Two separate imaginary squares (4 mm×4 mm) were indicated for the prefabricated BHC on the exposed lateral wall of the alveolar bone; six holes perforating the cortical bone were made within the imaginary square using a carbide bur with continuous saline irrigation. A prepared BHC was placed at the anterior site and covered with CM, while a prepared BHC was placed at the posterior site without a CM. The CM was fixed with two pins (membrane pin, Dentium, Seoul, Korea). Representative clinical photographs of the surgical site are shown in Fig. 1. Primary wound closure without tension was achieved with 4-0 resorbable suture materials (Monosyn 4-0 Glyconate Monofilament, B. Braun, Tuttlingen, Germany). Antibiotics and a soft diet were given to the animals for 14 days following the surgery. The sutures were removed 7 to 10 days postoperatively. The animals were sacrificed at 8 weeks postsurgery using an overdose of sodium pentobarbital (90-120 mg/kg, intravenous). The retrieved experimental sites were fixed in 10% buffered formalin for 10 days.

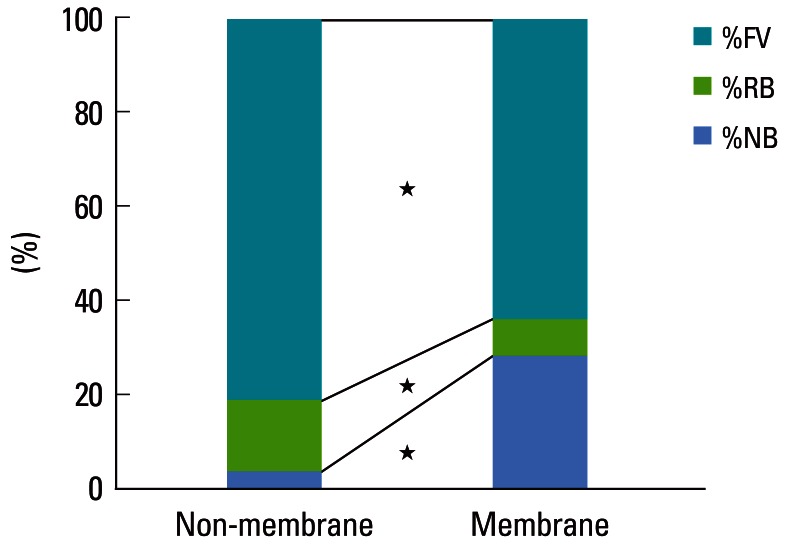

Figure 1.

Representative photograph of the surgical procedure (A), including the graft sites of the no-membrane-cover group (left; bovine hydroxyapatite [BH] particles incorporated with collagen matrix [BHC] alone) and the membrane-cover group (right; BHC covered with a collagen membrane). Descriptive photomicrograph (B: H&E, ×40) showing the different areas used for histometric analysis. The augmented area (AA, b) is bounded by an inferred baseline and augmentation line; the resorption area (RA, a) is bounded by an inferred baseline and resorption line; the total area includes both the AA (b) and RA (a). The inferred baseline is an imaginary line drawn as an extension of the external surface of the native alveolar bone. Black dotted line: inferred baseline, red dotted line: resorption line, blue dotted line: augmentation line, black asterisk: residual BH particle.

Histologic analysis

The specimens were decalcified in 5% formic acid for 10 days. The specimens were then trimmed and embedded in paraffin wax. Step-serial sections were cut at a thickness of 5 µm in a buccal-palatal vertical plane. The sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and with Masson's trichrome. The most-central section was included in the histologic and histometric analysis. Histologic observation was achieved using incandescent and polarized light microscopy (Olympus Research System Microscope BX51, Olympus Co., Tokyo, Japan). One calibrated, blinded examiner performed the histometric analysis using a PC-based image-analysis system (Image-Pro Plus, Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD, USA).

In order to discriminate the augmented from the resorbed area in the native alveolar bone, an imaginary line was drawn as an extension of the external surface of the native alveolar bone (inferred baseline). In addition, two more lines were drawn at the upper surface of the graft (augmentation line) and at the lower surface of the graft contacting the resorbed native alveolar bone (resorption line). The following areas and heights were defined and measured using the three lines (Fig. 1B):

Augmented area (AA) and augmented height (AH), respectively: area and height, respectively, between the augmentation line and the inferred baseline.

Resorption area (RA) and resorption height (RH), respectively: area and height, respectively, between the inferred baseline and the resorption line.

-

Total area (TA) and total height, respectively: area and height, respectively, including both the AA and AH, respectively, and RA and RH, respectively, between the augmentation and the resorption lines.

Furthermore, the area and height of newly formed bone from the inferred baseline were measured specifically in the AA.

New bone area (NBA) and new bone height (NBH), respectively.

Residual membrane (RM).

The proportions of the following parameters were calculated in TA (the component of RM in the TA was excluded in this calculation):

New bone (%NB).

Residual biomaterials (%RB).

Fibrovascular connective tissue (%FCT).

Statistical analysis

Summary statistics of all measured parameters were calculated using the central-most sections from each defect; the data are presented as mean±standard deviation values. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to evaluate the measured parameters between the two experimental groups using the PASW ver. 18 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA). The level of statistical significance was set at 5% (i.e., P<0.05).

RESULTS

Clinical observation

All of the experimental sites exhibited uneventful healing during the entire observation period. No signs of wound dehiscence or extensive inflammation were observed at any of the sites in either of the experimental groups.

Histologic observation

No inflammatory reaction was seen at any of the experimental sites. Both groups exhibited localized and clustered residual biomaterial particles at a grafted area of the alveolar ridge (Fig. 2). However, all sites showed a dome-shaped graft area rather than the box-type appearance of the original BHC. Specifically, the grafted site was flatter in the no-membrane-cover group than in the membrane-cover group.

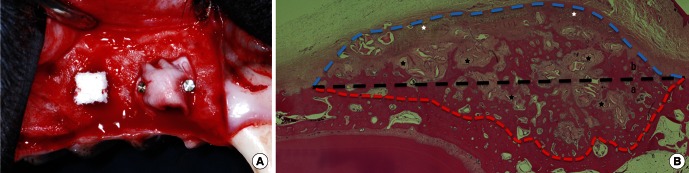

Figure 2.

Representative photomicrographs (Masson's trichrome stain, scale bars=1 mm) of the membrane-cover (A) and no-membrane-cover (B) groups. A periosteum-like dense connective tissue layer (white asterisks) was evident over the residual collagen membrane (black asterisks) in Fig. 2A, but beneath the grafted bovine hydroxyapatite (BH) particles in the site that received BH particles incorporated with collagen matrix only. At the graft sites of the membrane-cover group (A), extensive new bone formation was evident around and between the clusters of BH particles; however, the BH particles were encapsulated by collagen fibers at the no-membrane-cover site (B), and there was limited bone formation.

With the exception of one of the membrane-cover-group sites, resorption of the existing alveolar bone (RA) was observed under all of the grafted sites, and grafted particles were depressed to the lower level of the adjacent bony tissue. This resorbed native alveolar bone exhibited an irregular plane, unlike the adjacent native bone tissue (apart from the grafted area).

Membrane-cover group

In the group with a membrane cover, the specimens exhibited clustered BH particles and extensive bone formation within the space protected by the well-maintained CM. Multinucleated osteoclast-like cells were observed on the surface of the BH particles (Fig. 3A). Woven bone formation was seen all around the grafted area beneath the CM, where trabecular bone was seen in some specimens, bridging the existing alveolar bone base at the outer surface of the clustered BHC mass beneath the CM (Fig. 2). Most of the newly formed bone was present within the space between the particles or CM; however, some BH particles were intermittently in direct contact with the newly formed bone (Fig. 3A). Coupling of osteoblasts and multinucleated osteoclast-like cells was observed on individual BH particles.

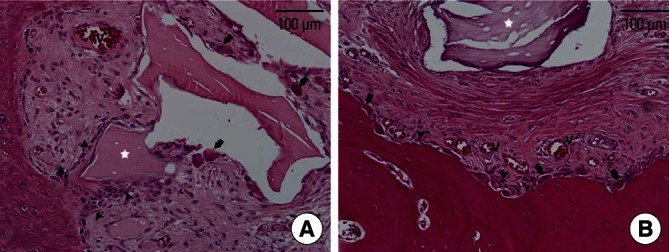

Figure 3.

High-magnification photomicrographs of a graft site from the membrane-cover group (A) and of the no-membrane-cover group (B). Residual bovine hydroxyapatite particles (white asterisk) within the space protected by the barrier membrane had many multinucleated osteoclast-like cells (arrows) on their surface, simultaneously with linearly arranged osteoblasts (arrowheads). In the no-membrane-cover group, multinucleated osteoclast-like cells and osteoblasts were evident on the resorbed surface of the existing bone rather than around the residual particles. V: newly formed vessels (H&E, scale bars=100 µm).

At 8 weeks of healing, the CM remained as a collagen network and still served as a barrier. Periosteum-like dense connective tissues were arranged in parallel with the residual CM in both the upper and lower areas of the CM. These were integrated with the fibrous network of the membrane, where many vessels were observed within or around the residual CM.

No-membrane-cover group

In the group without a membrane cover, limited bone formation occurred in the augmented area as well as the resorbed defect-like area. In three out of five specimens, periosteum-like dense connective tissue could be observed directly on the pre-existing cortical bone, where fibrous, encapsulated residual BHs were found in the loose connective tissue (Figs. 2 and 4). In the other two specimens, all residual BHs were embedded in the dense connective tissue layer. However, these sites also exhibited minimal bone formation around the BH particles. There were fewer multinucleated cells on the surface of the BH particles than in the membrane-cover group.

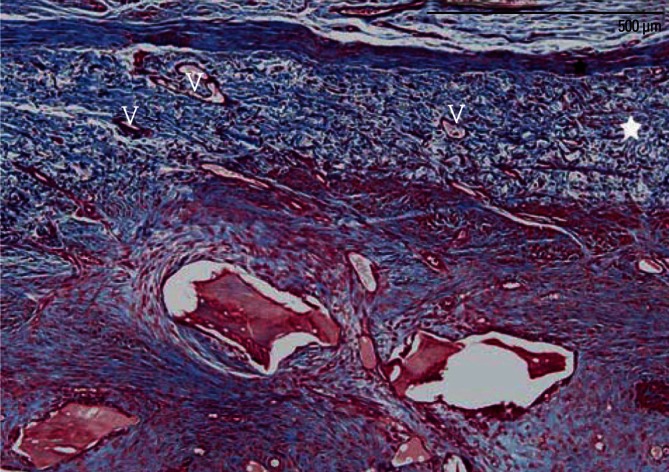

Figure 4.

Periosteum-like dense connective tissue layers (black asterisk) around the residual collagen membrane (CM) (white asterisk) in a graft site of the membrane-cover group (A) and between the grafted biomaterials and existing bone in the no-membrane-cover group (B). Most sites of the membrane-cover group exhibited a dense connective tissue layer beneath the residual CM (arrowheads), and newly formed vessels within it. In a graft site of the no-membrane-cover group, individual bovine hydroxyapatite particles were encapsulated by dense collagen fibers separately (without multinucleated osteoclast-like cells) over the newly formed periosteum (Masson's trichrome stain, scale bars=500 µm).

Histometric observation

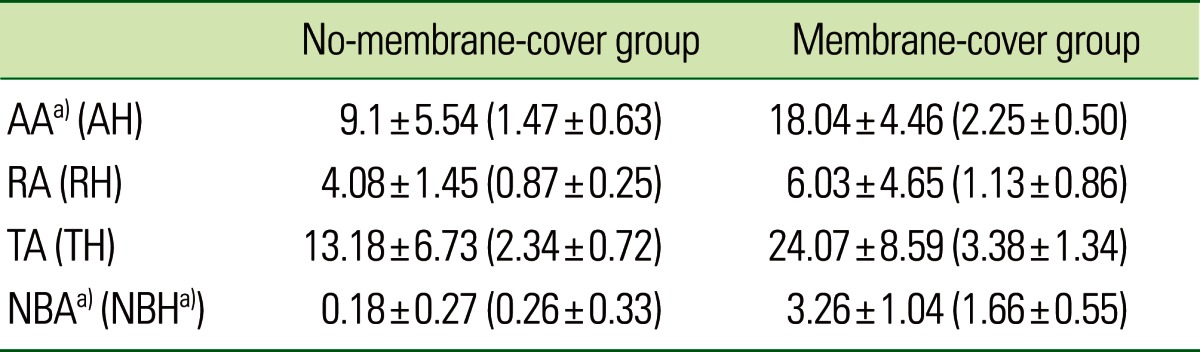

The results of the histometric analysis are given in Table 1 and shown in Fig. 5. The AA was significantly larger in the membrane-cover group (18.04±4.46 mm2) than in the no-membrane-cover group (9.1±5.54 mm2, P<0.05). There were also significant differences (P<0.05) between the membrane- and no-membrane-cover groups in NBA (3.26±1.04 mm2 vs. 0.18±0.27 mm2) and NBH (1.66±0.55 mm vs. 0.26±0.33 mm).

Table 1.

Results of the histometric analysis.

Values are presented as mean±standard deviation.

Values are presented as mean±standard deviation. AA: augmented area (mm2), AH: augmented height (mm), RA: resorption area (mm2), RH: resorption height (mm), TA: total area (mm2), TH: total height (mm), NBA: new bone area (mm2), NBH: new bone height (mm).

a)Significant difference between the no-membrane-cover and membrane-cover groups (P<0.05).

Figure 5.

Results of histometric analysis: proportions of newly formed bone (%NB), residual biomaterials (%RB), and fibrovascular connective tissue (%FV). All of the measured values differed significantly between the membrane-cover and no-membrane-cover groups (★P<0.05).

There was a significant increase in %NB, and significant decreases in %RB and %FCT between the two groups (P<0.05). The %NB averaged 28.13%±14.06% and 3.09%±5.98% in the membrane- and no-membrane-cover groups, respectively; the corresponding values for the %RB (%FCT) were 7.71%±3.39% (64.15%±14.83%) and 15.42%±4.09% (81.50%±3.13%), respectively.

DISCUSSION

Two hypotheses formed the basis of this study: 1) intact periosteum alone can exclude unwanted soft tissue from the grafted site, and 2) BHC covered with an intact periosteum can maintain its space provision for bone regeneration without dissipation. Both of these hypotheses were rejected on the grounds of the histometric results, which showed that the amount of new bone formation was significantly greater in the membrane-cover group than in the no-membrane-cover group. Moreover, the graft sites of the membrane-cover group exhibited more localized BH particles than the no-membrane-cover group, which collapsed and became encapsulated by the fibrous tissues. Thus, when an osteoconductive bone substitute was used, a dense periosteum alone was not sufficient to secure the grafted materials, and an additional barrier membrane may thus be essential for successful GBR. This finding is in line with previous research in which the use of a CM to cover the graft site appeared to improve the quality of the graft healing [14-16].

The results of the present study may be attributed to the defect model used (i.e., the onlay graft model) being unfavorable for bone regeneration given that it is a noncontained defect [17]. However, other studies have shown favorable bone regeneration without a protective barrier membrane in contained defect models, such as extraction sockets, class II furcation defects, and periodontal intrabony defects, as they have more healing sources from the defect walls [12,13,17].

Various bioresorbable materials have been used as barrier membranes, including collagen, polyurethane, polyglactin 910, polylactic acid, polyglycolic acid, polyorthoester, and poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) [18-20]. Among these, the CM has been the most widely used in the clinical and research fields, due to its biocompatibility and ease of clinical applicability. When the CM is used in the GBR procedure, it absorbs excess blood and easily covers and adheres to the grafted site [21]. In addition, the CM serves as a fibrillate scaffold for early vascular and tissue ingrowth [22] and acts as a barrier for migrating epithelial cells [23,24]. In the present study, the CM maintained its collagen network and still acted as a barrier after 8 weeks of healing. The newly formed bone lined the lower border of the CM, which communicated with the external connective tissue via small blood vessels (Fig. 6). This observation suggests that the CM permits angiogenesis within the structures and enhances wound healing. BH particles aggregated into clusters when BHC was applied to the defect, and new bone was generated around and between these clusters. In these areas, each BH particle was not surrounded by new bone, but rather maintained the entire space, and new bone was created within the space [25]. This can lead to the formation of woven bone between the grafted particles, which connects them together forming a cluster of mineralized tissue, whereby remodelling and replacement of these clusters by the more mature lamellar bone can follow [26].

Figure 6.

A high-magnification photomicrograph of a graft site of the membrane-cover group, showing many newly formed vessels (V) within the residual collagen membrane (white asterisk). Black asterisk: periosteum-like dense connective tissue layer (Masson's trichrome stain, scale bar=500 µm).

The findings of this study may also be affected by the relative positions of the periosteum and the grafted biomaterials. When the dense periosteum was laid above the grafted biomaterials, the grafted materials maintained their shape, thus allowing new bone to grow along the edge of the graft boundary. A dense periosteum was found over the remaining CM in the graft sites of the membrane-cover group, whereas most of the graft sites of the no-membrane-cover group exhibited periosteum-like dense connective tissue on the existing cortical bone and beneath the scattered grafted materials. When the grafted biomaterials were observed above the periosteum, the particles were separately encapsulated within loose connective tissue. These results seem to indicate the importance of the CM as a shield to prevent discontinuity of the periosteum and to hold the graft biomaterials in place. Another advantage of the CM is graft consolidation due to a reduction in osteoclastogenesis [27]. Although an increased number of multinucleated osteoclast-like cells were observed around the residual BH particles within the membrane-protected space, periosteum-like dense connective tissue layers with a minimal number of cells appeared around the residual CM. Grafted biomaterials may be separated from the outer connective tissue and epithelium by these layers.

In many of the graft sites, the existing cortical bone had resorbed beneath the grafted biomaterials where newly formed woven bone seemed to grow with finger-like projections from the resorbed surface of the alveolar bone. In this synchronized bone remodeling, multinucleated osteoclasts resorbed the bone substitute as the deposition of new bone occurred simultaneously on the same particle (Fig. 3A) [28]. It can be assumed that surface resorption of the cortical bone precedes bone formation during incorporation of the grafted material within the cortical bed. The TA was filled with newly formed trabecular bone in many graft sites of the membrane-cover group (four out of five sites), while it was filled only with fibrous tissue in the graft sites of the no-membrane-cover group (three out of five sites). As a consequence, three out of five sites in the no-membrane-cover group exhibited resorption of the existing bone rather than bone regeneration due to severe cortical resorption and fibrous encapsulation.

There is some controversy as to whether BH is a slowly resorbable or nonresorbable material. In the present study, numerous multinucleated osteoclast-like cells were observed around the residual biomaterials in both of the experimental groups, consistent with findings from previous studies [26,29-31].

In conclusion, within the limitations of this study, it can be concluded that the additional use of a barrier membrane may result in significantly higher new bone formation and better bone quality than a bone graft alone in lateral onlay grafts.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by a faculty research grant of Yonsei University College of Dentistry for 2010 (No. 6-2010-0098).

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Schenk RK, Buser D, Hardwick WR, Dahlin C. Healing pattern of bone regeneration in membrane-protected defects: a histologic study in the canine mandible. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 1994;9:13–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gottlow J, Nyman S, Karring T, Lindhe J. New attachment formation as the result of controlled tissue regeneration. J Clin Periodontol. 1984;11:494–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1984.tb00901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buser D, Dula K, Belser U, Hirt HP, Berthold H. Localized ridge augmentation using guided bone regeneration. 1. Surgical procedure in the maxilla. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 1993;13:29–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fugazzotto PA. Maintenance of soft tissue closure following guided bone regeneration: technical considerations and report of 723 cases. J Periodontol. 1999;70:1085–1097. doi: 10.1902/jop.1999.70.9.1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rintala AE, Ranta R. Periosteal flaps and grafts in primary cleft repair: a follow-up study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1989;83:17–24. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198901000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roberts SJ, Geris L, Kerckhofs G, Desmet E, Schrooten J, Luyten FP. The combined bone forming capacity of human periosteal derived cells and calcium phosphates. Biomaterials. 2011;32:4393–4405. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.02.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eyre-Brook AL. The periosteum: its function reassessed. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1984;189:300–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simion M, Nevins M, Rocchietta I, Fontana F, Maschera E, Schupbach P, et al. Vertical ridge augmentation using an equine block infused with recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor-BB: a histologic study in a canine model. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2009;29:245–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simion M, Rocchietta I, Dellavia C. Three-dimensional ridge augmentation with xenograft and recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor-BB in humans: report of two cases. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2007;27:109–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hammerle CH, Jung RE, Yaman D, Lang NP. Ridge augmentation by applying bioresorbable membranes and deproteinized bovine bone mineral: a report of twelve consecutive cases. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2008;19:19–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2007.01407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zecha PJ, Schortinghuis J, van der Wal JE, Nagursky H, van den Broek KC, Sauerbier S, et al. Applicability of equine hydroxyapatite collagen (eHAC) bone blocks for lateral augmentation of the alveolar crest. A histological and histomorphometric analysis in rats. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;40:533–542. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2011.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Araujo M, Linder E, Wennstrom J, Lindhe J. The influence of Bio-Oss Collagen on healing of an extraction socket: an experimental study in the dog. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2008;28:123–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heberer S, Al-Chawaf B, Hildebrand D, Nelson JJ, Nelson K. Histomorphometric analysis of extraction sockets augmented with Bio-Oss Collagen after a 6-week healing period: a prospective study. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2008;19:1219–1225. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2008.01617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tawil G, Mawla M. Sinus floor elevation using a bovine bone mineral (Bio-Oss) with or without the concomitant use of a bilayered collagen barrier (Bio-Gide): a clinical report of immediate and delayed implant placement. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2001;16:713–721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamada S, Shima N, Kitamura H, Sugito H. Effect of porous xenographic bone graft with collagen barrier membrane on periodontal regeneration. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2002;22:389–397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Donos N, Lang NP, Karoussis IK, Bosshardt D, Tonetti M, Kostopoulos L. Effect of GBR in combination with deproteinized bovine bone mineral and/or enamel matrix proteins on the healing of critical-size defects. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2004;15:101–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2004.00986.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim CS, Choi SH, Chai JK, Cho KS, Moon IS, Wikesjo UM, et al. Periodontal repair in surgically created intrabony defects in dogs: influence of the number of bone walls on healing response. J Periodontol. 2004;75:229–235. doi: 10.1902/jop.2004.75.2.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brunel G, Benque E, Elharar F, Sansac C, Duffort JF, Barthet P, et al. Guided bone regeneration for immediate non-submerged implant placement using bioabsorbable materials in Beagle dogs. Clin Oral Implants Res. 1998;9:303–312. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0501.1998.090503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sandberg E, Dahlin C, Linde A. Bone regeneration by the osteopromotion technique using bioabsorbable membranes: an experimental study in rats. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1993;51:1106–1114. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(10)80450-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zellin G, Gritli-Linde A, Linde A. Healing of mandibular defects with different biodegradable and non-biodegradable membranes: an experimental study in rats. Biomaterials. 1995;16:601–609. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(95)93857-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tawil G, El-Ghoule G, Mawla M. Clinical evaluation of a bilayered collagen membrane (Bio-Gide) supported by autografts in the treatment of bone defects around implants. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2001;16:857–863. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blumenthal NM. A clinical comparison of collagen membranes with e-PTFE membranes in the treatment of human mandibular buccal class II furcation defects. J Periodontol. 1993;64:925–933. doi: 10.1902/jop.1993.64.10.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pitaru S, Tal H, Soldinger M, Azar-Avidan O, Noff M. Collagen membranes prevent the apical migration of epithelium during periodontal wound healing. J Periodontal Res. 1987;22:331–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1987.tb01594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pitaru S, Tal H, Soldinger M, Noff M. Collagen membranes prevent apical migration of epithelium and support new connective tissue attachment during periodontal wound healing in dogs. J Periodontal Res. 1989;24:247–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1989.tb01789.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stavropoulos A, Wikesjo UM. Influence of defect dimensions on periodontal wound healing/regeneration in intrabony defects following implantation of a bovine bone biomaterial and provisions for guided tissue regeneration: an experimental study in the dog. J Clin Periodontol. 2010;37:534–543. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2010.01566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tadjoedin ES, de Lange GL, Bronckers AL, Lyaruu DM, Burger EH. Deproteinized cancellous bovine bone (Bio-Oss) as bone substitute for sinus floor elevation. A retrospective, histomorphometrical study of five cases. J Clin Periodontol. 2003;30:261–270. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2003.01099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Agis H, Magdalenko M, Stogerer K, Watzek G, Gruber R. Collagen barrier membranes decrease osteoclastogenesis in murine bone marrow cultures. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2010;21:656–661. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2009.01888.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bassil J, Senni K, Changotade S, Baroukh B, Kassis C, Naaman N, et al. Expression of MMP-2, 9 and 13 in newly formed bone after sinus augmentation using inorganic bovine bone in human. J Periodontal Res. 2011;46:756–762. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2011.01400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Araujo MG, Liljenberg B, Lindhe J. Dynamics of Bio-Oss Collagen incorporation in fresh extraction wounds: an experimental study in the dog. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2010;21:55–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2009.01854.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berglundh T, Lindhe J. Healing around implants placed in bone defects treated with Bio-Oss. An experimental study in the dog. Clin Oral Implants Res. 1997;8:117–124. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0501.1997.080206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jung UW, Lee JS, Park WY, Cha JK, Hwang JW, Park JC, et al. Periodontal regenerative effect of a bovine hydroxyapatite/collagen block in one-wall intrabony defects in dogs: a histometric analysis. J Periodontal Implant Sci. 2011;41:285–292. doi: 10.5051/jpis.2011.41.6.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]