Abstract

Objective

To map the state of the existing literature evaluating the use of social media in patient and caregiver populations.

Design

Scoping review.

Data sources

Medline, CENTRAL, ERIC, PubMed, CINAHL Plus Full Text, Academic Search Complete, Alt Health Watch, Health Source, Communication and Mass Media Complete, Web of Knowledge and ProQuest (2000–2012).

Study selection

Studies reporting primary research on the use of social media (collaborative projects, blogs/microblogs, content communities, social networking sites, virtual worlds) by patients or caregivers.

Data extraction

Two reviewers screened studies for eligibility; one reviewer extracted data from relevant studies and a second performed verification for accuracy and completeness on a 10% sample. Data were analysed to describe which social media tools are being used, by whom, for what purpose and how they are being evaluated.

Results

Two hundred eighty-four studies were included. Discussion forums were highly prevalent and constitute 66.6% of the sample. Social networking sites (14.8%) and blogs/microblogs (14.1%) were the next most commonly used tools. The intended purpose of the tool was to facilitate self-care in 77.1% of studies. While there were clusters of studies that focused on similar conditions (eg, lifestyle/weight loss (12.7%), cancer (11.3%)), there were no patterns in the objectives or tools used. A large proportion of the studies were descriptive (42.3%); however, there were also 48 (16.9%) randomised controlled trials (RCTs). Among the RCTs, 35.4% reported statistically significant results favouring the social media intervention being evaluated; however, 72.9% presented positive conclusions regarding the use of social media.

Conclusions

There is an extensive body of literature examining the use of social media in patient and caregiver populations. Much of this work is descriptive; however, with such widespread use, evaluations of effectiveness are required. In studies that have examined effectiveness, positive conclusions are often reported, despite non-significant findings.

Keywords: social media, scoping review

Article summary.

Article focus

The use of social media in healthcare has been widely advocated, but there is little evidence describing the current state of the science and whether or not these tools can be used to benefit patient populations.

We mapped the state of the existing literature evaluating the use of social media in patient and caregiver populations.

Key messages

There is an extensive and rapidly growing body of literature available investigating the use of social media in patient and caregiver populations.

Most studies have been descriptive; however, with such widespread use, evaluations of effectiveness are needed.

In studies that have examined effectiveness, positive conclusions are often reported, despite the non-significant findings.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Our search was comprehensive and we included an extensive body of literature, across conditions, populations and study designs.

Social media is constantly evolving, leading to challenges in keeping the search updated.

A more in-depth analysis is needed on specific topics, conditions and populations to guide the use and implementation of social media interventions.

Introduction

The use of social media in healthcare has been widely advocated1–8; however, there is little evidence describing the current state of the science and whether or not these tools can be used to benefit patient populations. It is clear, though, that in addition to seeking out traditional sources of healthcare information, patients are increasingly active online.9 In 2011, looking for healthcare information was the third most common online activity,10 and in September 2012, 72% of adult internet users sought support and medical information online.11 In 2012, 67% of internet users were using social media for any purpose12 and 26% were using it for health issues.11 As social media continues to evolve, its momentum shows no sign of diminishing, instead finding new niches with unique applications.

Social media can be defined as a group of online applications that allow for the creation and exchange of user-generated content, and can be categorised into five groups: (1) collaborative projects (eg, Wikipedia); (2) blogs or microblogs (eg, Blogger, Twitter); (3) content communities (eg, YouTube); (4) social networking sites (eg, Facebook) and (5) virtual gaming or social worlds (eg, HumanSim).13 The collaborative environment to which social media belongs represents a shift in technology and functionality from ‘Web 1.0’, in which static online content and applications were created and published by individuals, to ‘Web 2.0’, in which there is continuous modification and participation by all users.13 Table 1 provides an overview of the categories of social media tools.

Table 1.

Categorisation of social media tools

| Tool | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Collaborative projects | Enable the joint and simultaneous creation of content by many end-users | Wikis (eg, Wikipedia) Social bookmarking applications (eg, Mendeley) |

| Blogs or microblogs | Websites that display date-stamped entries. They are usually managed by one person but provide the opportunity to interact with others through the addition of comments | Wordpress Twitter (microblog) |

| Content communities | Allow for the sharing of media content between users, including text, photos, videos and presentations | BookCrossing Flickr YouTube Slideshare |

| Social networking sites | Enable users to connect by creating personal information profiles that can be accessed by friends and colleagues, and by sending emails and instant messages between each other | Facebook MySpace |

| Virtual worlds | Platforms that replicate a 3D environment in which users can appear in the form of personalised avatars and interact with each other as they would in real life | Second Life |

Advocates of the use of social media in healthcare suggest that these tools allow for personalisation, presentation and participation—three key elements that make them highly effective.14 The content can be tailored to the priorities of the users; the versatility of the different platforms creates numerous options for the presentation of information, and the collaborative nature of social media allows for a meaningful contribution from all user groups. The idea of a synergistic relationship between social media users is one of the main perceived advantages of using these platforms.15 However, criticisms of the use of social media in healthcare have also arisen. The availability of misinformation is a risk, as healthcare providers are unable to control the content that is posted or discussed.1 16 17 Inappropriate substitution of online information or advice for in-person visits to a healthcare provider can also potentially lead to harmful results, and this has been cited as a limitation of the use of social media and of the internet generally.1 18 Negative uses of social media have also been highlighted in the context of professionalism and confidentiality,19 use by children and youth due to a limited capacity for self-regulation and vulnerability to peer influence,20 and promotion of high-risk behaviours, such as suicide-related behaviours, drug use and eating disordered behaviours.21–24

The objectives of this study were to map the existing literature examining the use of social media in patient and caregiver populations, to determine the extent and type of evidence available to inform more focused knowledge syntheses and to identify gaps for future research. The specific questions guiding this scoping review were: (1) What social media tools are being used to improve health outcomes in patient populations? (2) For what purposes are social media tools being used in patient populations (eg, to improve health literacy, to improve self-care)? (3) For what patient populations and disease conditions are social media tools being used? (4) What types of evidence and research designs (ie, qualitative, quantitative) have been used to examine social media tools?

Methods

This scoping review on the use of social media in patient and caregiver populations was conducted in parallel with a review on the use of social media in healthcare professional and trainee populations25; therefore, the literature search and screening for study eligibility were conducted concurrently. The review followed a protocol that we developed a priori.

Search strategy

A research librarian searched 11 databases in January 2012: Medline, CENTRAL, ERIC, PubMed, CINAHL Plus Full Text, Academic Search Complete, Alt Health Watch, Health Source, Communication and Mass Media Complete, Web of Knowledge and ProQuest. Dates were restricted to 2000 or later, corresponding to the advent of Web 2.0. No language or study design restrictions were applied. The search strategy for Medline is provided in the online supplementary appendix.

Study selection

Two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts of studies for eligibility. The full text of studies assessed as ‘relevant’ or ‘unclear’ was then independently evaluated by two reviewers using a standard form. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus or adjudication by a third party.

Studies were included if they reported primary research (quantitative or qualitative), focused on healthcare issues related to patients or caregivers, and examined the use of a social media tool. Social media was defined according to Kaplan and Haenlein's classification scheme,13 including: collaborative projects, blogs or microblogs, content communities, social networking sites and virtual worlds. We excluded studies that examined mobile health (eg, tracking or medical reference apps), one-way transmission of content (eg, podcasts) and real-time exchanges mediated by technology (eg, Skype, chat rooms). Electronic discussion forums and bulletin boards were included as they incorporate user-generated content and were judged to fall within the spectrum of social media. Outcomes were not defined a priori as they were to be incorporated into our description of the field. The most likely categories for objectives and outcomes were adapted from those outlined in Coulter and Ellins’26 27 proposed framework for strategies to inform, educate and involve patients.

Data extraction

Data were extracted using standardised forms and entered into Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, Washington, USA) by one reviewer and a 10% sample was checked for accuracy and completeness by another.28 Reviewers resolved discrepancies through consensus. Extracted data included study and population characteristics, description of the social media tools used, objective of the tools, outcomes measured and authors’ conclusions.29 Studies that examined social media as one component of a complex intervention were noted as such. Additional data were collected for randomised controlled trials (RCTs), including the primary outcome and its statistical significance.

Data synthesis

Data were synthesised descriptively to map different aspects of the literature as outlined in our key questions. Studies were grouped according to tool, audience and study design, with data from RCTs being examined in more detail. As discussion forums were not included in our original classification scheme, findings are presented both for all included studies and for studies that investigated tools other than discussion forums. Descriptive statistics were calculated using StataIC 11 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

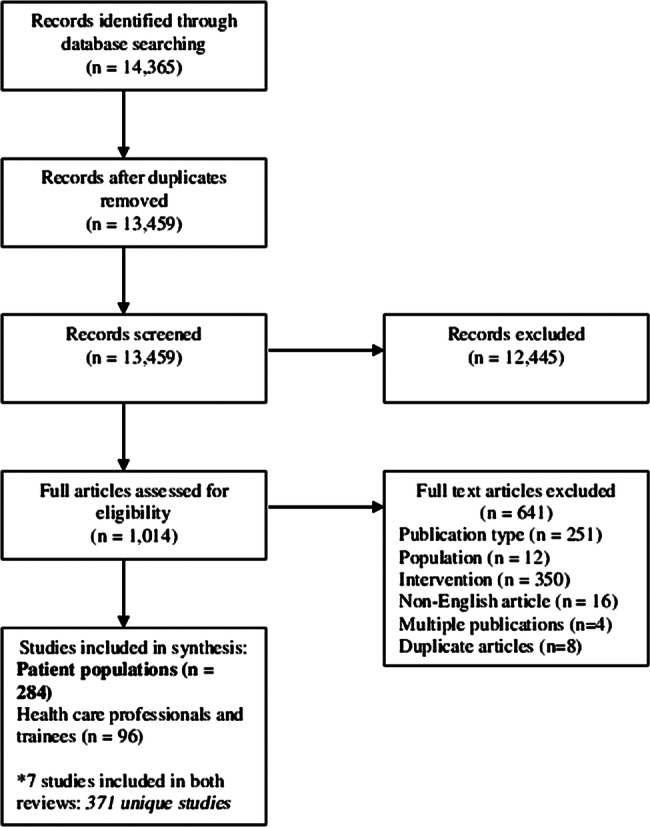

Two hundred eighty-four studies were included in the review. Figure 1 outlines the flow of studies through the inclusion process and table 2 provides a description of the included studies. Most studies (179/284; 63.0%) were conducted in North America, with more than half of the total sample (154/284; 54.2%) carried out in the USA and 8.8% (25/284) conducted in Canada. The median start date was in 2006 (range 1997–2011); when studies evaluating discussion forums were excluded, the start date was more recent (median 2008, range 2000–2011). Studies tended to be fairly short, with a median duration of 5 months (range 1–117 months). Nearly all included studies were published as journal articles (255/284; 89.8%); however, when studies of discussion forums were excluded, the proportion of dissertations written on the use of social media increased (14/284 to 12/95; 4.9–12.6%).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of included studies.

Table 2.

Description of included studies

| Variable | Total—n (%) | Excluding discussion forums—n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Total—N | 284 | 95 |

| Continent of corresponding author | ||

| Asia | 12 (4.2) | 5 (5.3) |

| Australia | 14 (4.9) | 3 (3.2) |

| Europe | 78 (27.5) | 19 (20.0) |

| North America | 179 (63.0) | 67 (70.5) |

| Not reported | 1 (0.4) | 1 (1.1) |

| Study start date—median (range) | 2006 (1997–2011) | 2008 (2000–2011) |

| Study duration—median (range) | 5 months (1–117) | 3 months (1–117) |

| Sample size—median (range) | 124 (1–16703)* | 130 (2–16703)* |

| Publication type | ||

| Journal article | 255 (89.8) | 75 (79.0) |

| Abstract | 15 (5.3) | 8 (8.4) |

| Dissertation | 14 (4.9) | 12 (12.6) |

| Study design | ||

| Quantitative | ||

| Randomised controlled trial | 48 (16.9) | 6 (6.3) |

| Non-randomised controlled trial | 6 (2.1) | 1 (1.1) |

| Controlled before-after | 1 (0.4) | – |

| Observational | 11 (3.9) | 3 (3.2) |

| Cross-sectional | 63 (22.2) | 33 (34.7) |

| Qualitative | ||

| Case study | 1 (0.4) | – |

| Case series | 3 (1.1) | 2 (2.1) |

| Ethnography | 3 (1.1) | 2 (2.1) |

| Grounded theory | 6 (2.1) | 2 (2.1) |

| Phenomenology | 6 (2.1) | 1 (1.1) |

| Qualitative (other/not specified) | 46 (16.2) | 16 (16.8) |

| Mixed methods | 33 (11.6) | 9 (9.5) |

| Other | ||

| Content analysis | 57 (20.1) | 20 (21.1) |

| Authors’ conclusions | ||

| Positive | 186 (65.5) | 56 (59.0) |

| Neutral | 65 (22.9) | 23 (24.2) |

| Negative | 15 (5.3) | 10 (10.5) |

| Indeterminate | 18 (6.3) | 6 (6.3) |

*Excluding one study that examined >3 000 000 tweets.

Social media tools used

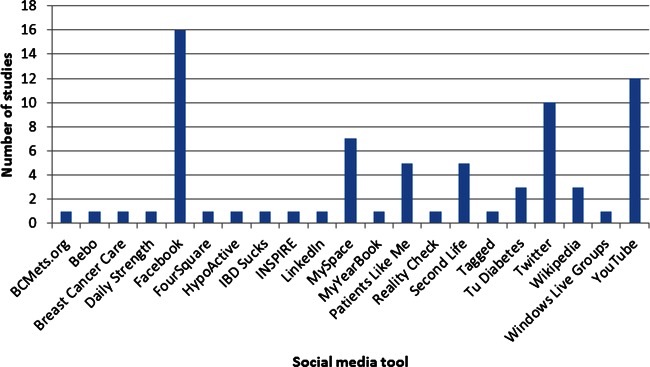

The social media tools studied are outlined in table 3. The use of discussion boards and online support groups (combined as discussion forums due to their common structure and intent) dominated the literature, encompassing 189 (66.6%) included studies. Social networking sites (42/284; 14.8%) and blogs or microblogs (40/284; 14.1%) were also commonly evaluated, followed by content communities (16/284; 5.6%), collaborative projects (6/284; 2.1%) and virtual worlds (6/284; 2.1%). In 116 (40.9%) included studies, the social media tool was included as part of a complex intervention. Where existing and publicly available social media applications were studied, Facebook (16/284; 5.6%), YouTube (12/284; 4.2%) and Twitter (10/284; 3.5%) were evaluated most frequently (figure 2).

Table 3.

Description and objectives of social media tools used (N=284)

| Objective—n (%) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tool | Total—n (%) | Health literacy | Clinical decision making | Self-care | Patient safety | Others |

| Total—n (%) | 47 (16.6) | 7 (2.5) | 219 (77.1) | 19 (6.7) | 39 (13.7) | |

| Collaborative project | 6 (2.1) | 5 (83.3) | – | – | – | 1 (16.7) |

| Blog or microblog | 40 (14.1) | 11 (27.5) | – | 24 (60.0) | 4 (10.0) | 9 (22.5) |

| Content community | 16 (5.6) | 8 (50.0) | – | 5 (31.3) | 2 (12.5) | 4 (25.0) |

| Social networking site | 42 (14.8) | 10 (23.8) | 1 (2.4) | 24 (57.1) | 8 (19.1) | 9 (21.4) |

| Virtual world | 6 (2.1) | 3 (50.0) | – | 3 (50.0) | 1 (16.7) | 1 (16.7) |

| Discussion forum | 189 (66.6) | 23 (12.2) | 6 (3.2) | 166 (87.8) | 3 (1.6) | 17 (9.0) |

| Component of a complex intervention | 116 (40.9) | 16 (13.8) | 3 (2.6) | 108 (93.1) | 4 (3.5) | 3 (2.6) |

Percentages do not add up to 100 due to the possibility of multiple tools and multiple objectives per study.

Figure 2.

Specific social media tools described in included studies.

Purposes of social media use

The most common intended use of social media was for self-care, which was described as an objective of the tool in 219 (77.1%) studies (table 3). This was particularly relevant to discussion forums, in which 166/189 (87.8%) studies were related to self-care. Other tools were often established with similar functions to discussion forums: they provided a platform on which users could post and share their experiences with peers. Collaborative projects were often used to address health literacy, and social networking sites were commonly used for patient safety purposes, largely for documentation of adverse events. While there were few studies that addressed clinical decision-making, these were almost exclusively conducted using discussion forums.

We categorised the outcomes measured in each of the studies under patients’ knowledge, patients’ experience, use of services and costs, health behaviour and status and others (table 4). Measures of patients’ experience, specifically peer-to-peer communication (135/284; 47.5%), were most common and were often outcomes related to social support among members of an online community. Measures of psychological well-being (eg, reports of anxiety levels) and changes in self-care activities (eg, increases in physical activity) in relation to use of the tool were also commonly evaluated (78/284 and 63/284; or 27.5% and 22.2%, respectively).

Table 4.

Outcomes measured by social media tool

| Outcomes | Total—n (%) | Excluding discussion forums—n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Total—N | 284 | 95 |

| Patients’ knowledge | ||

| Conditions and complications | 54 (19.0) | 22 (23.2) |

| Self-care | 60 (21.1) | 17 (17.9) |

| Treatment options | 22 (7.8) | 10 (10.5) |

| Comprehension | 2 (0.7) | 1 (1.1) |

| Patients’ experience | ||

| Satisfaction | 69 (24.3) | 21 (22.1) |

| Clinician–patient communication | 39 (13.7) | 16 (16.8) |

| Peer-to-peer communication | 135 (47.5) | 44 (46.3) |

| Quality of life | 20 (7.0) | 2 (2.1) |

| Psychological well-being | 78 (27.5) | 21 (22.1) |

| Self-efficacy | 32 (11.3) | 4 (4.2) |

| Involvement and empowerment | 22 (7.8) | 6 (6.3) |

| Use of services and costs | ||

| Hospital admission rates | 4 (1.4) | 2 (2.1) |

| Emergency admission rates | 2 (0.7) | – |

| Number of visits to general practitioners | 7 (2.5) | 2 (2.1) |

| Cost effectiveness | 4 (1.4) | 3 (3.2) |

| Health behaviour and status | ||

| Self-care activities | 63 (22.2) | 15 (15.8) |

| Treatment adherence | 13 (4.6) | 1 (1.1) |

| Severity of disease or symptoms | 17 (6.0) | 4 (4.2) |

| Physical functioning | 21 (7.4) | 6 (6.3) |

| Mental functioning | 25 (8.8) | 8 (8.4) |

| Clinical indicators | 23 (8.1) | 3 (3.2) |

| Others | ||

| Attitudes and preferences | 14 (4.9) | 7 (7.4) |

| Content and accuracy | 33 (11.6) | 21 (22.1) |

| Usability | 9 (3.2) | 2 (2.1) |

| Usage and demographics | 106 (37.3) | 34 (35.8) |

Percentages do not add up to 100 due to the possibility of multiple outcomes per study.

Social media user groups

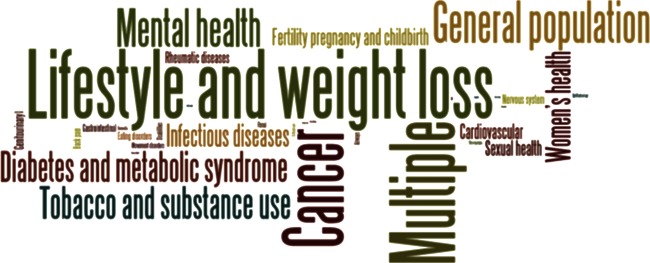

A wide range of conditions were covered in the included studies (figure 3). The largest proportion fell under the lifestyle and weight loss category (36/284; 12.7%), followed by cancer (32/284; 11.3%) and studies in the general population (22/284; 7.8%). The general population studies tended to be surveys focused on usage, demographics and user preferences relevant to social media use for health-related purposes. No strong trends emerged showing differences between user groups in the objective of the type of social media tool or the specific application used (data not shown). In nearly all conditions investigated, the social media tool studied was intended to facilitate self-care. One exception was seen in the case of infectious disease, where 7/12 (58.3%) relevant studies were focused on health literacy. This was mainly driven by large-scale strategies to provide updates on influenza or H1N1. For specific applications used, there were clusters of studies that examined condition-specific modalities. Social networking sites were common in studies of diabetes and metabolic syndrome due to the use of TuDiabetes, an online community targeted to those affected by diabetes. Similarly, Twitter was commonly used in the context of H1N1/influenza, and PatientsLikeMe was used for a group of chronic conditions including amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, fibromyalgia, HIV, mood disorders, multiple sclerosis and Parkinson's disease. Aside from these small clusters, most studies across all conditions were conducted using discussion forums.

Figure 3.

Word cloud representing the conditions included in the study populations. The size of each term is proportional to its representation in the review.

Evaluation of social media use

The majority of the included studies were descriptive: 63 (22.2%) were cross-sectional and 57 (20.1%) used content analysis to outline how social media is being applied (table 2). Qualitative studies comprised 22.9% (65/284) of the total sample; mixed methods studies 11.6% (33/284); observational studies 3.9% (11/284) and experimental studies 19.4% (55/284). Of the 33 mixed methods studies, 11 included a cross-sectional component and 20 included content analyses. Forty-eight RCTs were conducted, 45 of which were evaluating discussion forums as at least one component of the intervention. Of the remaining RCTs, one evaluated a blog, one evaluated Second Life and one made use of Facebook and Twitter.

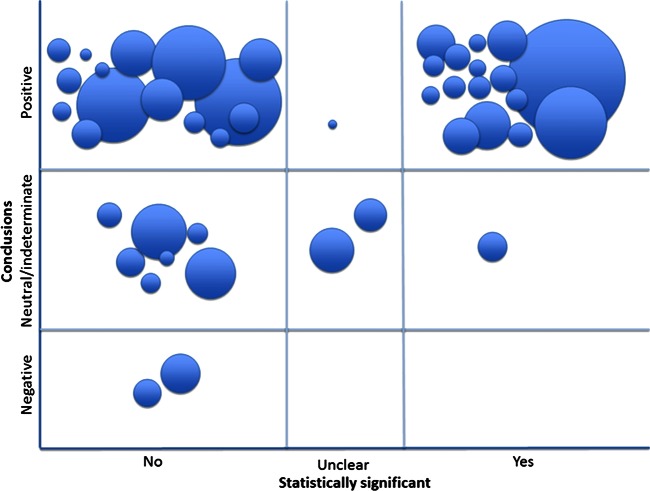

Overall, 186/284 (65.5%) studies concluded that there was evidence for the utility of social media, while only 15/284 (5.3%) concluded that there was not (table 5). The subset of RCTs was examined in more detail; while 35/48 (72.9%) studies presented positive conclusions, only 16/35 (45.7%) reported a statistically significant effect in relation to the primary outcome (figure 4). All but one study with significant findings evaluated the use of a discussion forum; the other study evaluated a blog. Clusters of conditions appeared in the RCTs: six studies were related to lifestyle and weight loss, three were related to tobacco and substance use, two were in mental health and six were in other conditions (diabetes, irritable bowel syndrome, multiple sclerosis, hearing loss and breast cancer). The primary outcome in each of these studies was related to health behaviour and status, except two that evaluated patients’ experience and one that measured website use. The social media tool was one component of a complex intervention in all studies, making it difficult to tease out any effect specific to its use. However, improvements were found in outcomes such as changes in body weight and activity levels, tobacco or substance use and quality of life.

Table 5.

Social media objectives by authors’ conclusions (N=284)

| Objective—n (%) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conclusions | Total—n (%) | Health literacy | Clinical decision making | Self-care | Patient safety | Others |

| Total—n (%) | 47 (16.6) | 7 (2.5) | 219 (77.1) | 19 (6.7) | 39 (13.7) | |

| Positive | 186 (65.5) | 28 (59.6) | 6 (85.7) | 149 (68.0) | 14 (73.7) | 21 (53.8) |

| Neutral | 65 (22.9) | 12 (25.5) | 1 (14.3) | 47 (21.5) | 1 (5.3) | 13 (33.3) |

| Negative | 15 (5.3) | 5 (10.6) | – | 7 (3.2) | 3 (15.8) | 3 (7.7) |

| Indeterminate | 18 (6.3) | 2 (4.3) | – | 16 (7.3) | 1 (5.3) | 2 (5.1) |

Figure 4.

Authors’ conclusions by statistical significance and sample size among randomised controlled trials. Each bubble represents one study and its size is proportional to the number of individuals evaluated.

Discussion

There is an extensive and rapidly growing body of literature available for investigating the use of social media in patient and caregiver populations. While diversity exists in terms of the tools used, their intended purposes and the conditions studied, the majority of studies evaluate discussion forums. This could point to the popularity of discussion forums among patients and caregivers in addressing their healthcare concerns; however, it may also be indicative of the behaviours or preferences of the site designers.

While general tools with broad applications (ie, discussion forums) are commonly used, the promise of social media lies in its adaptability. Unique applications such as PatientsLikeMe and TuDiabetes have evolved out of the need to address the specific concerns of particular online communities, demonstrating the success that can be realised through tailoring a tool to the requirements of a chosen target audience. Conversely, a general tool such as Twitter has shown that it can not only be applied to a variety of different purposes but also has found a specific niche in disseminating public health alerts. The ability of these platforms to be customised for different purposes is highly consistent with the principles underlying successful knowledge translation interventions.30

Most studies were descriptive, but our sample also included 48 RCTs. Nearly all of the trials evaluated the effectiveness of the discussion forums, leaving a research gap in the evaluation of the performance of other social media tools. Given the rapid proliferation of social media, a plethora of platforms are being used and an investigation of their benefits and harms is a logical progression of the research agenda. Similarly, the next steps in research could focus on isolating the effect of the social media tool, particularly as it relates to improved patient outcomes. All of the included RCTs evaluated a complex intervention, of which the social media tool was just one component. More focused efforts to determine whether social media has an impact on its own, or whether any observed effects are attributable to the intervention overall or to the non-social media components, would be a research priority. Similarly, a more in-depth examination of how the social media interventions are implemented, and specifically how and to what extent health or other professionals are involved, would contribute to a better understanding of their use. Further, additional research is needed to clarify whether the use of social media truly confers an advantage, or if the novelty of the medium is solely responsible for its use.31 The contrast between the statistical significance of the primary outcome in the RCTs and the positive conclusions reported suggests that issues such as selective outcome reporting (eg, choice of groups to compare), misrepresentation of conclusions (eg, focus on change over time within a group, rather than differences between groups) and a spin in reporting (eg, emphasis on a positive trend) may play a more substantial role in the promotion of social media use than actual effectiveness. The fact that most interventions were evaluated by their developers may have also influenced the positive conclusions reported.

Much of the research to this point has focused on measures of communication between peers or on social support, but our sample also included trials measuring the impact of social media on health behaviour and status. With applications that directly target health outcomes, social media could present a cost-effective and wide-reaching modality for administering certain types of interventions. This could be particularly advantageous when logistics make arranging in-person appointments difficult, for example, in hard to reach populations, or when geography is an issue. These studies also suggest that social media has the potential to move beyond providing supportive online communities and could have widespread utility within the healthcare setting. However, these applications are dependent on further evidence of effectiveness.

Limitations

Social media is a relatively new concept that is continually undergoing transformation. As such, there is no universal definition, adding complexity to the process of determining study eligibility. The constantly changing nature of social media also proved challenging in defining the literature search, and the novelty of the topic made it difficult to keep the search updated due to a steady influx of new reports. However, as the focus of this scoping review was to identify broad categories of social media uses, the addition of studies published after the literature search would be unlikely to change the results.

While this scoping review focused on the peer-reviewed literature to identify how social media is being used by patient and caregiver populations, it may not encompass all of the work that has been done in the area, or cover the extent of the impact that social media has had on healthcare. Much of the driving force behind the use of social media has come from outside the academic community; therefore, certain constructs such as the role that Facebook plays in advocacy and community, and patient empowerment resulting from the use of Twitter have not been captured. Additionally, certain movements that have shaped social media use in healthcare, such as the ePatient movement32 and Citizen Science,33 were not included within the scope of our review. While we endeavoured to be as comprehensive as possible in covering the published literature, our included patient population may not be representative of people who use social media for health generally.

As our inclusion criteria were intentionally broad, we included a number of different study designs, encompassing both quantitative and qualitative research. While this introduced challenges in addressing the nuances of each type of study, the end result is a comprehensive overview of the state of the literature. Further syntheses of the evidence in specific topics, clinical areas and populations will be able to provide more focus on some of these details.

Conclusions

This scoping review provides a map of the existing literature evaluating the use of social media in patient and caregiver populations. The available evidence is extensive, and most studies to date have been descriptive in nature. Given such widespread use of social media, evaluations of effectiveness are also needed. While positive conclusions are commonly reported, these may not be reflective of the actual findings.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Walie Aktary for his assistance in data extraction, and Terry Klassen, Sharon Straus, Donna Angus and Liz Whamond for their contributions to the design of this review.

Footnotes

Contributors: MPH, SDS, LMG and LH designed the study. MPH coordinated the project and is the guarantor. MPH, AC and JS screened articles and performed data extraction. AM contributed to the conception of the study and conducted the literature search. MPH, AC, JS and LH interpreted the data. MPH drafted and all authors critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Funding: This study was supported by a Knowledge Synthesis Grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, grant number 262961. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Hawn C. Take two aspirin and tweet me in the morning: how Twitter, Facebook, and other social media are reshaping health care. Health Affair 2009;28:361–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allison M. Can web 2.0 reboot clinical trials? Nat Biotechnol 2009;27:895–902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonilla-Warford N. Many social media options exist for optometrists. Optometry 2010;81:613–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brownstein CA, Brownstein JS, Williams DS, et al. The power of social networking in medicine. Nat Biotechnol 2009;27:888–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eytan T, Benabio J, Golla V, et al. Social media and the health system. Perm J 2011;15:71–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spallek H, O'Donnell J, Clayton M, et al. Paradigm shift of annoying distraction: emerging implications of web 2.0 for clinical practice. Appl Clin Inf 2010;1:96–115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morris K. Tweet, post, share—a new school of health communication. Lancet Infect Dis 2011;11:500–1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Villagran M. Methodological diversity to reach patients along the margins, in the shadows, and on the cutting edge. Patient Educ Counsel 2011;82:292–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Timimi FK. Medicine, morality and health care social media. BMC Medicine 2012;10:83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fox S. Health topics. American Life Project, 2011. http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2011/HealthTopics/Summary-of-Findings/Looking-for-health-information.aspx (accessed 29 Jan 2013)

- 11.Fox S, Duggan M. Health online 2013. Pew Research Center, 2013. http://www.pewinternet.org/~/media//Files/Reports/PIP_HealthOnline.pdf (accessed 4 Apr 2013)

- 12.Duggan M, Brenner J. The demographics of social media users—2012. Pew Research Center, 2013. http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2013/Social-media-users.aspx (accessed 8 Mar 2013)

- 13.Kaplan AM, Haenlein M. Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of social media. Bus Horiz 2010;53:59–68 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The health communicator's social media toolkit. http://www.cdc.gov/healthcommunication/ToolsTemplates/SocialMediaToolkit_BM.pdf (accessed 17 Sep 2012)

- 15.Sarasohn-Kahn J. The wisdom of patients: health care meets online social media. California Health care Foundation, 2008. http://www.chcf.org/publications/2008/04/the-wisdom-of-patients-health-care-meets-online-social-media (accessed 17 Sep 2012)

- 16.Crocco AG, Villasis-Keever M, Jadad AR. Two wrongs don't make a right: harm aggravated by inaccurate information on the Internet. Pediatrics 2002;109:522–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chou WS, Prestin A, Lyons C, et al. Web 2.0 for health promotion: reviewing the current evidence. Am J Public Health 2013;103:e9–e18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crocco AG, Villasis-Keever M, Jadad AR. Analysis of cases of harm associated with use of health information on the internet. JAMA 2002;287:2869–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greysen SR, Kind T, Chretien KC. Online professionalism and the mirror of social media. J Gen Intern Med 2010;25:1227–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McBride DL. Risks and benefits of social media for children and adolescents. J Pediatr Nurs 2011;26:498–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Collings SC, Fortune S, Currey N, et al. Media influences on suicidal behaviour: an interview study of young people in New Zealand. Auckland: The National Centre of Mental Health Research, Information and Workforce Development, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vickers H. Social networks and media coverage are blamed for series of teenage suicides in Russia. BMJ 2012;344:e3110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strasburger VC, Donnerstein E. Children, adolescents, and the media in the 21st century. Adolesc Med 2000;11:51–68 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Strasburger VC. Children, adolescents and the media: what we know, what we don't know and what we need to find out (quickly!). Arch Dis Child 2009;94:657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamm MP, Chisholm A, Shulhan J, et al. Use of social media by health care professionals and trainees: a scoping review. Acad Med 2013. In press [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coulter A, Ellins J. Patient-focused interventions: a review of the evidence. London: Health Foundation, 2006. http://www.pickereurope.org/Filestore/Publications/QEI_Review_AB.pdf (accessed 17 Sep 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coulter A, Ellins J. Effectiveness of strategies for informing, educating, and involving patients. BMJ 2007;335:24–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buscemi N, Hartling L, Vandermeer B, et al. Single data extraction generated more errors than double data extraction in systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol 2006;59:697–703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tricco A, Tetzlaff J, Pham B, et al. Non-Cochrane vs. Cochrane reviews were twice as likely to have positive conclusion statements: cross-sectional study. J Clin Epidemiol 2009;62:380–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Graham ID, Logan J, Harrison MB, et al. Lost in translation: time for a map? J Contin Health Educ 2006;26:13–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rogers EM. Diffusion of Innovations. 5th edn New York: The Free Press, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Debronkart D. How the e-patient community helped save my life: an essay by Dave deBronkart. BMJ 2013;346:f1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Swan M. Crowdsourced health research studies: an important emerging complement to clinical trials in the public health research ecosystem. J Med Internet Res 2012;14:e46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.